|

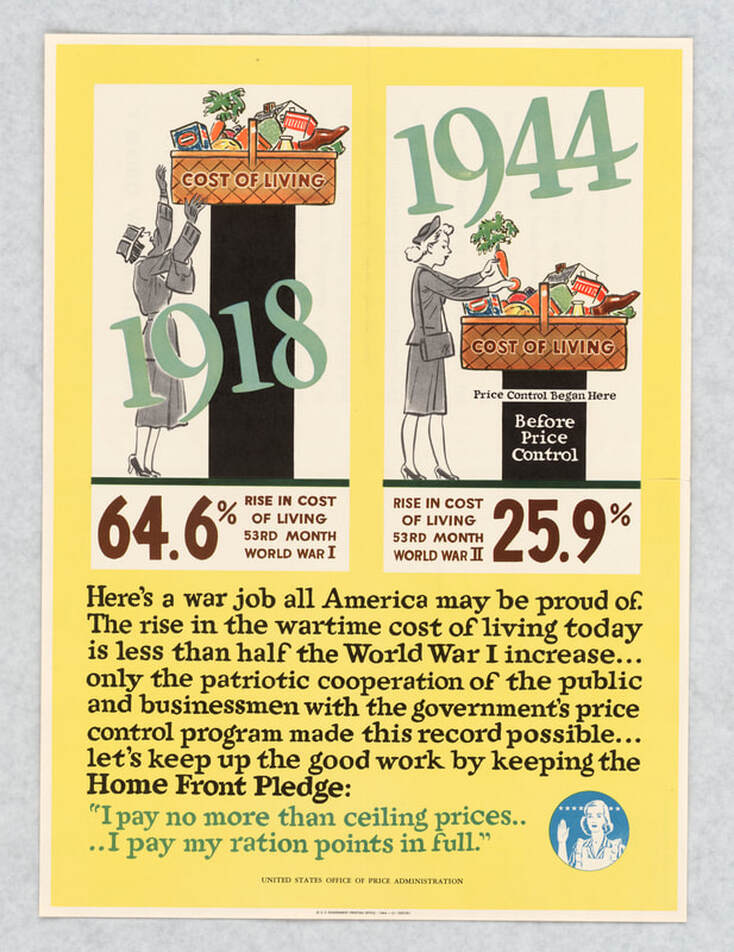

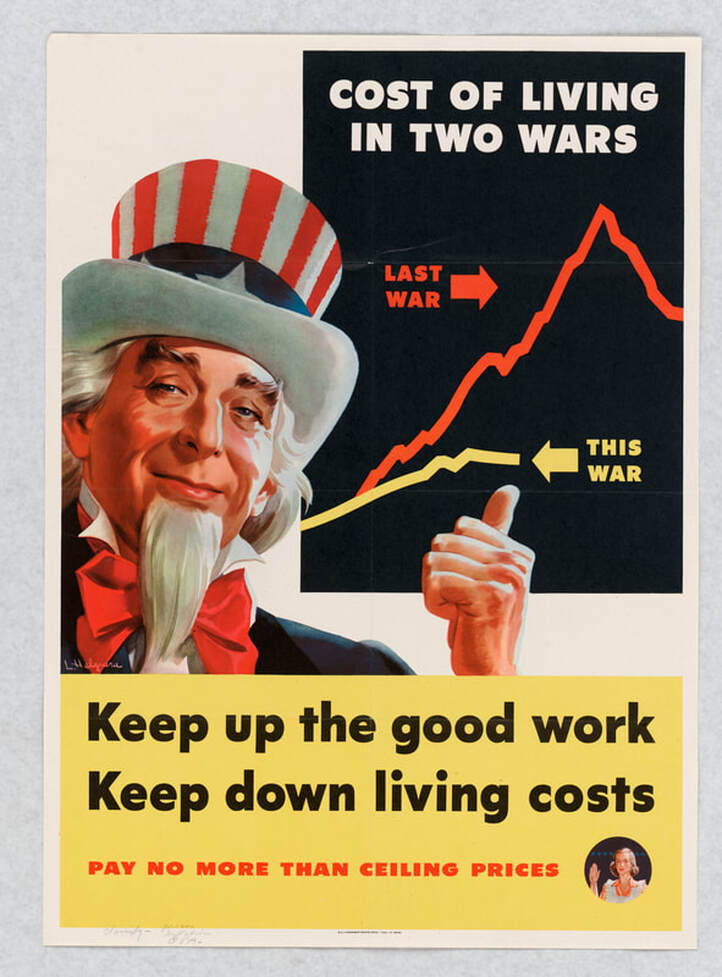

Last week we talked about the High Cost of Living in the First World War. Those memories were close at hand during the Second World War. During World War I, the federal government did little to control prices at the consumer level, and rationing was voluntary. The U.S. Food Administration did control whether or not retail establishments and manufacturers complied with rationing and other rules through a complicated system of licensing and oversight, but individual consumers were technically allowed to make their own food choices. During World War II, things were different. Rationing was mandatory, even if the stamps were often confusing, and black markets definitely existed. But the creation of the Office of Price Administration froze the official prices of a whole host of goods, including food, to try to offset wartime inflation. Once again retailers were being regulated by the government, but this time the OPA relied on consumers to help report violators. By enlisting housewives to help enforce "ceiling prices" by refusing to purchase goods at that exceeded the published price lists, the OPA got a free labor source, and the housewives ensured that their retailers were not cheating them. Black women, in particular, benefitted from this practice, as discrimination meant they were subject to being cheated.  "Here's a war job all America may be proud of. The rise in wartime cost of living today is less than half the World War I increase... only the patriotic cooperation of the public and businessmen with the government's price control program made this record possible... let's keep up the good work by keeping the Home Front Pledge: "I pay no more than ceiling prices... I pay my ration points in full."" Office of Price Administration, National Archives. This pair of posters, comparing the inflation of food from WWI to WWII, was designed to prove the effectiveness of the Office of Price Administration and its price control efforts. In the first one, Uncle Sam points to a chart that compares the rise of inflation over the course of both World Wars. In the second, two bar charts on inflation are compared. In the first, labeled 1918, a (suspiciously-1930s-attired) housewife tries and fails to reach a basket of food labeled "Cost of Living" as it rises on a bar chart of 64.6% inflation. Whereas the 1944 housewife can easily reach her basket at 25.9% inflation. Interestingly, her bar chart has a white line 3/4 of the way up which reads "Price control began here." The black bar below reads "Before Price Control," implying that inflation could have been much worse without the intervention of the OPA. Both statistics are attributed to the 53rd month of the war, which seems to indicate that the inflation statistics for World War I start in 1914, not 1917, when the U.S. officially joined the war, which tracks with the cost of living increases that began long before April 7, 1917. These two posters indicate just one of the ways in which the lessons of the First World War were applied to the Second. Some lessons, however, remained hard to swallow. During WWI, the United States Food Administration, although formed by executive order in May of 1917, received no funding from Congress until August, 1917, because a number of congressmen objected to the sweeping powers and controls it gave the executive branch. In an effort to avoid a bloated post-war bureaucracy, it was quickly dismantled in early 1919, despite the fact that the cost of living rose precipitously after the war. Similar sentiments about the power of the Office of Price Administration were debated during WWII, and numerous attempts by organized retail and manufacturing organizations to weaken it started as early as 1944. The OPA was allowed to temporarily expire in 1945, and prices jumped almost instantly. It was hastily reinstated, but in a weaker form, and was fully abolished in 1947. Some price control functions for sugar, rice, and a few other products were shifted to other agencies. In her article, "'How About Some Meat?': The Office of Price Administration, Consumption Politics, and State Building from the Bottom Up, 1941-1946," historian Meg Jacobs talks about how the Office of Price Administration helped Americans determine that high standards and low cost of living was their reward, nay birthright, for surviving two World Wars and a Great Depression. Caught between empowered consumers and producers and retailers anxious to throw off the yoke of government regulation, the OPA was at the center of post-war discussions about the future of the American economy. Given today's cost of living problems, I find it fascinating to study the economics of the first half of the 20th century, and how societal reactions and government policies continue to shape today's discussions about the future of our economy - whether people realize it or not. Today, economists are studying the impact of the Great Recession and COVID-19 on our economic future, just like historians and economists in the 1920s and 1940s did when they were looking back at the two World Wars. Further Reading

If you enjoyed this blog post, consider supporting The Food Historian on Patreon! Patrons get special perks, including members-only content, access to digitized cookbooks, and occasional snail mail. Patrons also help keep this blog free for everyone. Join today!

1 Comment

|

AuthorSarah Wassberg Johnson has an MA in Public History from the University at Albany and studies early 20th century food history. Archives

July 2024

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed