|

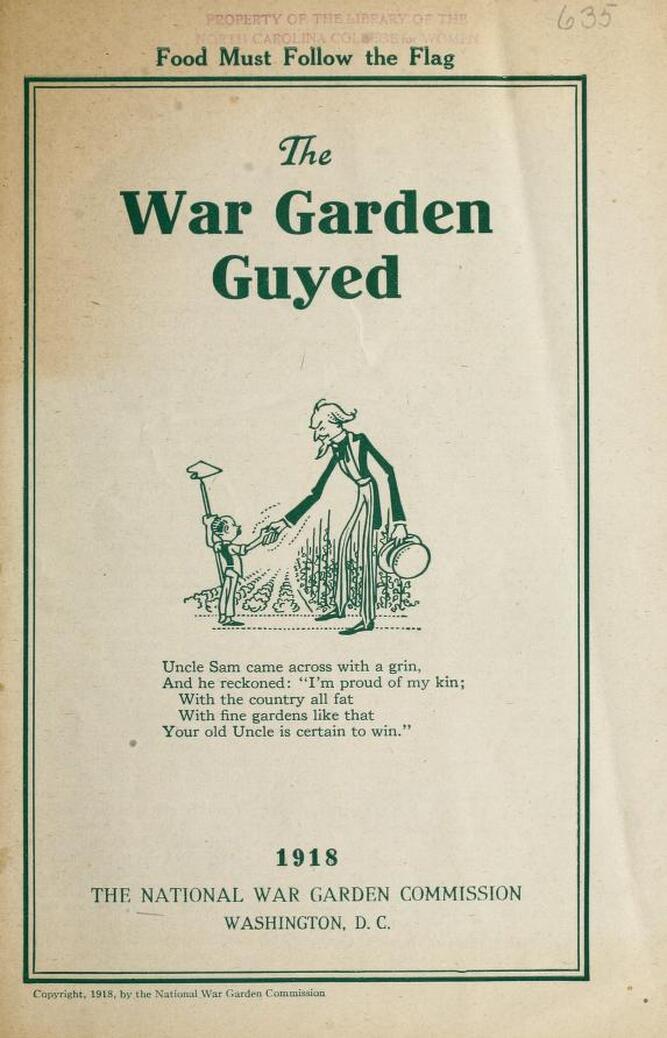

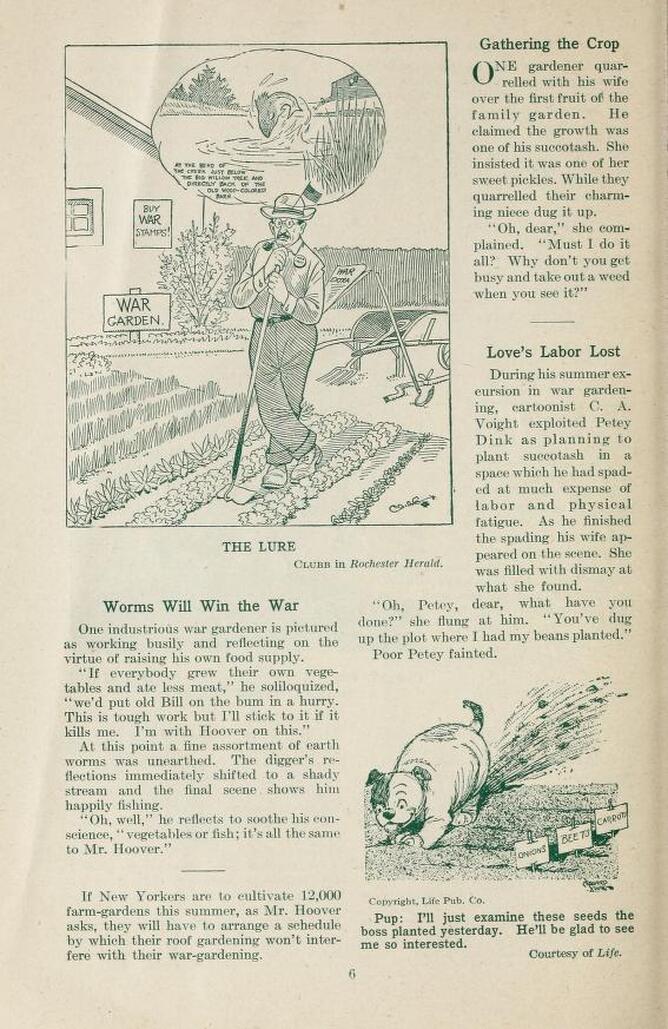

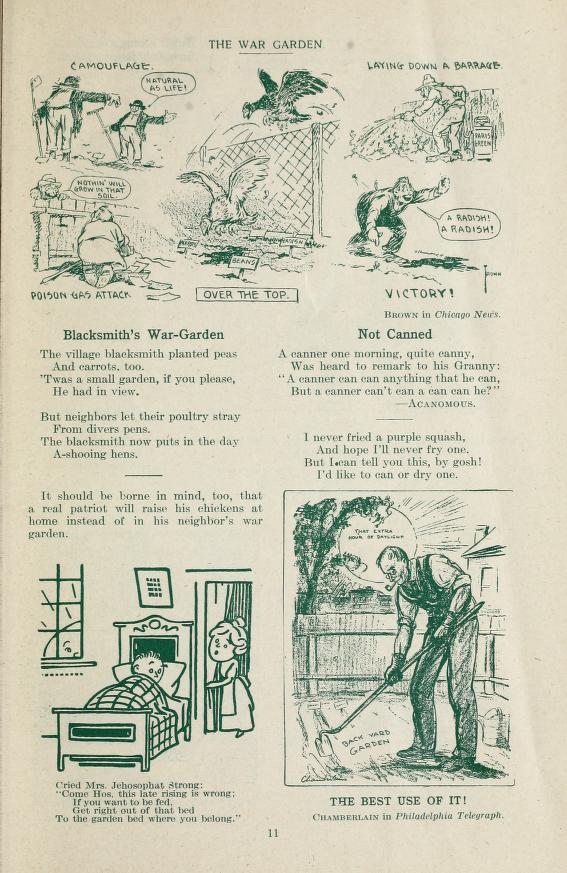

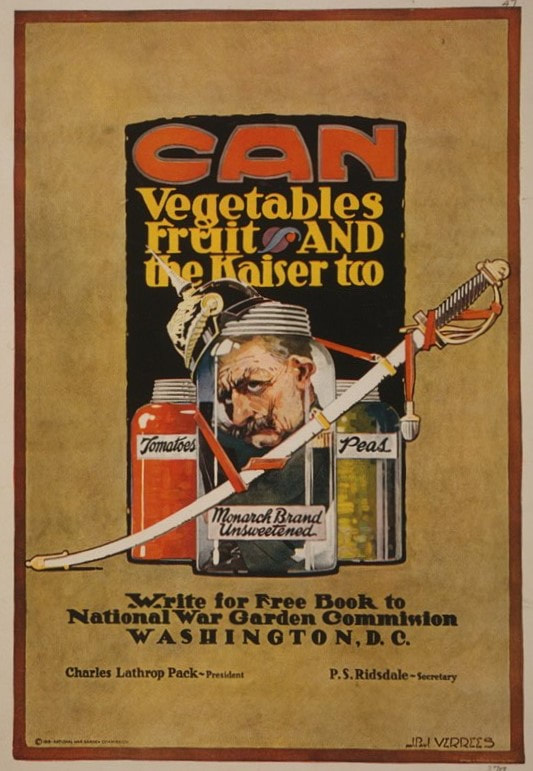

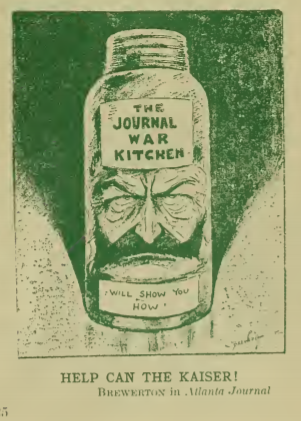

Although literal tons of snow have fallen across the United States in the past week or so, it's still beginning to feel like spring, which for many of us means our thoughts turn to gardening. If you know anything about World War II, you've probably heard of Victory Gardens. But did you know they got their start in the First World War? And the popularity of "war gardens" as they were initially called, is largely thanks to a man named Charles Lathrop Pack. Pack was the heir to a forestry and lumber fortune, and pumped lots of his own money into creating the National War Garden Commission, which promoted war gardening across the country, along with food preservation. They published a number of propaganda posters and instructional pamphlets. Today's World War Wednesday feature is another pamphlet, but its primary audience was not the general public, but rather newspaper and magazine publishers! Full of snippets of poetry, jokes, cartoons, and articles published by newspapers and magazines around the country, even the title was a bit of a joke. "The War Garden Guyed" is a play on the words "guide" and the verb "guy" which means to make fun of, or ridicule. So "The War Garden Guyed" is both a manual to war gardens and also a way to make fun of them. In the introduction, the National War Garden Commission (likely Charles Lathrop Pack himself), writes: "This publication treats of the lighter side of the war garden movement and the canning and drying campaign. Fortunately a national sense of humor makes it possible for the cartoonist and the humorist to weave their gentle laughter into the fabric of food emergency. That they have winged their shafts at the war gardener and the home canner serves only to emphasize the vital value of these activities." Each page of the "guyed" has at least one image and a few bits of either prose or poetry. The below page is one of my favorites. In the upper cartoon, an older man leans on his hoe in a very orderly war garden. His house in the background features a large "War Garden" sign and a poster saying "Buy War Stamps!" In his pocket is a folded newspaper with the headline "War Extra." But he is dreaming of a lake with jumping fish and the caption - indicating the location of the best fishing spot. The cartoon is called "The Lure" and demonstrates how people ordinarily would have been spending their summers. In the lower right hand corner, a roly poly little dog digs frantically in fresh soil. Little signs read "Onions, Beets, Carrots." The caption says "Pup: I'll just examine these seeds the boss planted yesterday. He'll be glad to see me so interested." Another article on the page is titled "Love's Labor Lost." It reads: "During his summer excursion in war gardening, cartoonist C. A. Voight exploited Petey Dink as planning to plant succotash in a space which had had spaded at much expense of labor and physical fatigue. As he finished the spading his wife appeared on the scene. She was filled with dismay at what she found. 'Oh Petey, dear, what have you done?' she flung at him. 'You've dug up the plot where I had my beans planted.' Poor Petey fainted." Many of the bits of doggerel and cartoons poked fun at inexperienced gardeners like Petey Dink. Pests, animals, digging up backyards and hauling water, the difficulty in telling weeds from seedlings, and finally the joy at the first crop. This page has a comic at the top that illustrates these trials and tribulations perfectly, through the lens of war. In the upper left hand corner, a sketch entitled "Camouflage" depicts a man who has just finished putting up a scarecrow who crows, "Natural as life!" as he poses exactly the same as his creation. Below, another called "Poison Gas Attack" depicts a neighbor leaning over the fence to comment "Nothin will grow in that soil" at a man kneeling in the dirt, a bowl of seed packets and a hoe on either side of him. The title implies that the neighbor is full of hot air and poison. The center scene, titled "Over the Top," shows a pair of chickens gleefully flying over a fence to attack a plot marked "Carrots," "Beans," and "Radishes." In the top right-hand corner, in a sketch titled "Laying Down a Barrage," a man with a pump cannister labeled "Paris Green" is spraying his plants. Paris Green was an arsenical pesticide. And finally, in one labeled "Victory!" a man gleefully points to a small seedling in an otherwise empty row and cries, "A radish! A radish!" In a bit of verse called "Not Canned" reads: A canner one morning, quite canny, Was heard to remark to his Granny: "A canner can can anything that he can, But a canner can't can a can can he?" And finally, apt for this past weekend's Daylight Savings Time "spring forward" is an evocative sketch depicts a man hoeing up his back yard garden while a large sun shines brightly and reads "That extra hour of daylight." The sketch is captioned, "The best use of it!" "The War Garden Guyed" has 32 pages of verse, doggerel, short articles, and cartoons. Charles Lathrop Pack was correct when he said the newspapers evoked "gentle laughter" as none of the satirical sheets actually discourage gardening. Indeed, most of the text is directly in line with the propaganda of the day promoting the development of household war gardens and the movement to "put up" produce through home canning and drying. Many of the cartoons directly connect to the war itself, comparing fighting pests to fighting Huns, pesticides to ammunition and "trench gas," and equating canning and food preservation efforts with vanquishing generals. What the booklet does do is poke fun at all of the hardships and difficulties first-time or inexperience gardeners would face. Stray chickens, cabbage worms and potato beetles, dogs and children, competing spouses, naysaying neighbors, post-vacation forests of weeds, and trying desperately to impress coworkers and neighbors with first efforts. War gardens were no easy task, and there were plenty of people who felt that they were a waste of good seed. But Pack and the National War Garden Commission persisted. They believed that inspiring ordinary people to participate in gardening would not only increase the food supply, but also free up railroads for transporting war materiel instead of extra food, get white collar workers some exercise and sunshine, and provide fresh foods in a time of war emergency. How successful the gardens of first-year gardeners were is certainly debatable. But in many ways, war gardens were more about participating than food. After the war, Pack rebranded his "war gardens" as "victory gardens," asking people to continue planting them even in 1919. The idea struck such a chord that when the Second World War rolled around two decades after the first had ended, "victory gardens" and home canning again became a clarion call for ordinary people to participate in the war on the home front. The full "War Garden Guyed" has been digitized and is available online at archive.org. The Food Historian blog is supported by patrons on Patreon! Patrons help keep blog posts like this one free and available to the public. Join us for awesome members-only content like free digitized cookbooks from my personal collection, e-newsletter, and even snail mail from time to time! Don't like Patreon? Leave a tip!

0 Comments

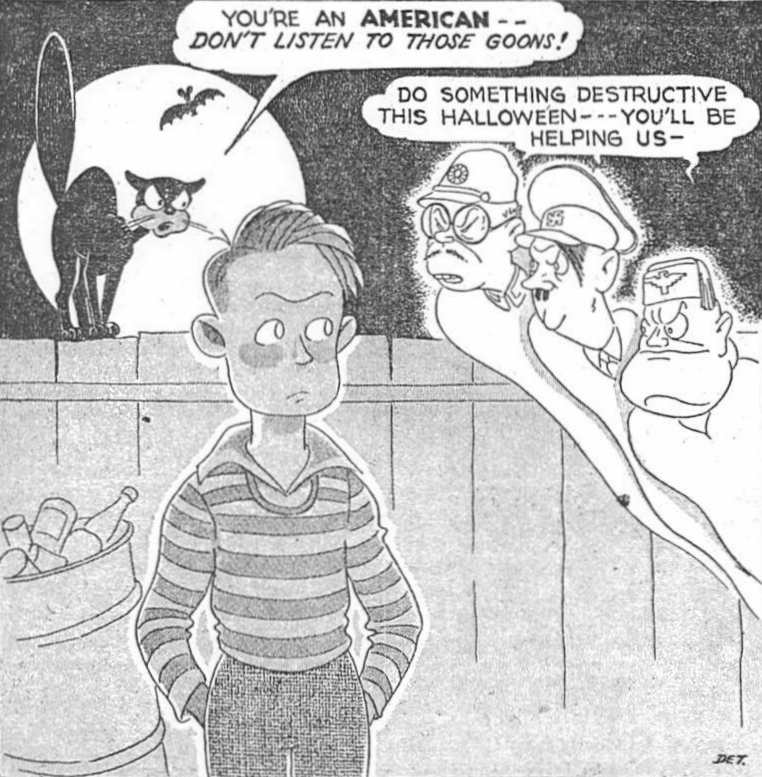

Welcome to The Food Historian's 31 Days of Halloween extravaganza. Between social media (Facebook, Instagram, Twitter) and this blog, I'll be sharing vintage Halloween content nearly every day this month!  Cartoon published in the "San Diego Union," October 25, 1942. Ghosts of Emperor Hirohito of Japan, Adolph Hitler of Germany, and Benito Mussolini say in unison, "Do something destructive this Halloween - you'll be helping us -" to a teenaged boy in an alley. A black cat on the fence behind him says, "You're an AMERICAN - don't listen to those goons!" Trick or treating today is usually about young children, costumes, and lots of candy. In many communities, it's over by 8 or 9 pm. But historically, trick or treating was more about the tricks than the treats. Going door to door threatening tricks if treats were not offered instead is very old, but has deeper roots in association with Christmas than with Halloween. Despite the tradition's age, going door to door for treats on Halloween was not widely practiced in the United States until the 20th century. The pranks, however, were popular among teenaged boys. From the relatively harmless pranks like soaping car windows and placing furniture on porch roofs to the destructive ones like slashing tires, breaking windows, egging houses, and starting fires in the streets, pranks were common in communities across the country. The war changed all that. Halloween, 1942 was the first since the United States entered the war in December, 1941. Across the nation, newspapers published warnings to would-be prankers that destructive acts of the past would no longer be tolerated. This one, published on October 30, 1942 in The Corning Daily Observer in Corning, California, was typical of other messages other newspapers: "Hallowe'en Pranks Are Out For the Duration" "The destructive Hallowe'en pranks of breaking fences, stealing gates, deflating auto tires, ringing door bells to disturb sleepers, soaping windows, and all other forms of the removal or destruction of buildings or property are definitely out and forbidden on Hallowe'en night, according to word from Corning city officials. "Supplies are needed for national defense and are too scarce to permit misuse. "Word comes from Washington that individuals committing such offense shall be prosecuted as saboteurs and be treated accordingly. "Corning officials state that there will be no fooling about this matter this year and anyone contemplating 'having fun' will be treated with severely." The newspaper cartoon above, published in the San Francisco Union on October 25, 1942, illustrates just this sentiment. In it, the ghosts of Japanese Emperor Hirohito, German Chancellor Adolph Hitler, and Italian fascist Prime Minister Benito Mussolini egg on a young boy hanging out in a dark back alleyway. "Do something destructive this Halloween - - - You'll be helping us - " they tell him. On the high fence behind the boy stands a black cat, back arched in anger, silhouetted by a full moon. He says to the boy, "You're an American - - Don't listen to those goons!" Conflating Halloween pranks with sabotage and aiding the Axis powers was no joke. The November, 1942 newspapers feature stories of pranksters waking sleeping war workers, scaring their neighbors by setting off air raid bells, and causing car accidents by leaving debris in the roads. Several ended up in court, and some got buckshot wounds from angry homeowners for their efforts. Wartime propaganda like this was common - caricatures of the Axis leaders showed up frequently in newspapers, cartoons, and propaganda posters. For Halloween, they made convenient bogeymen. World War II was the beginning of the end of Halloween tricks. Although more innocuous pranks like egging houses and cars and toilet-papering trees and porches continued to be hallmarks of Halloween mischief, the days of fires in the streets, broken windows, and other real crimes were largely in the past. Communities that had previously celebrated Halloween with private parties at home, shifted to more public events like parades, community dances, and trick-or-treating geared toward small children getting treats rather than teenagers engaging in tricks. Further Reading If you'd like to learn more about Halloween during World War II, check out these additional resources:

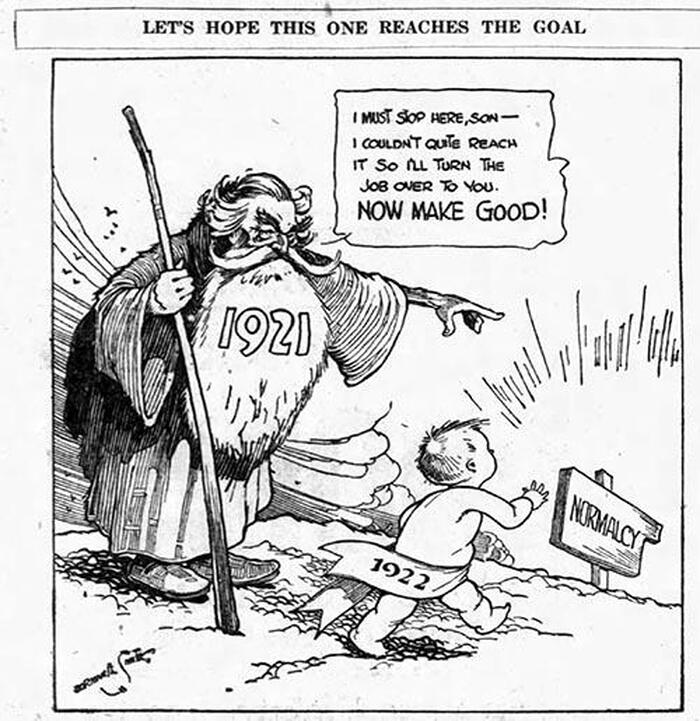

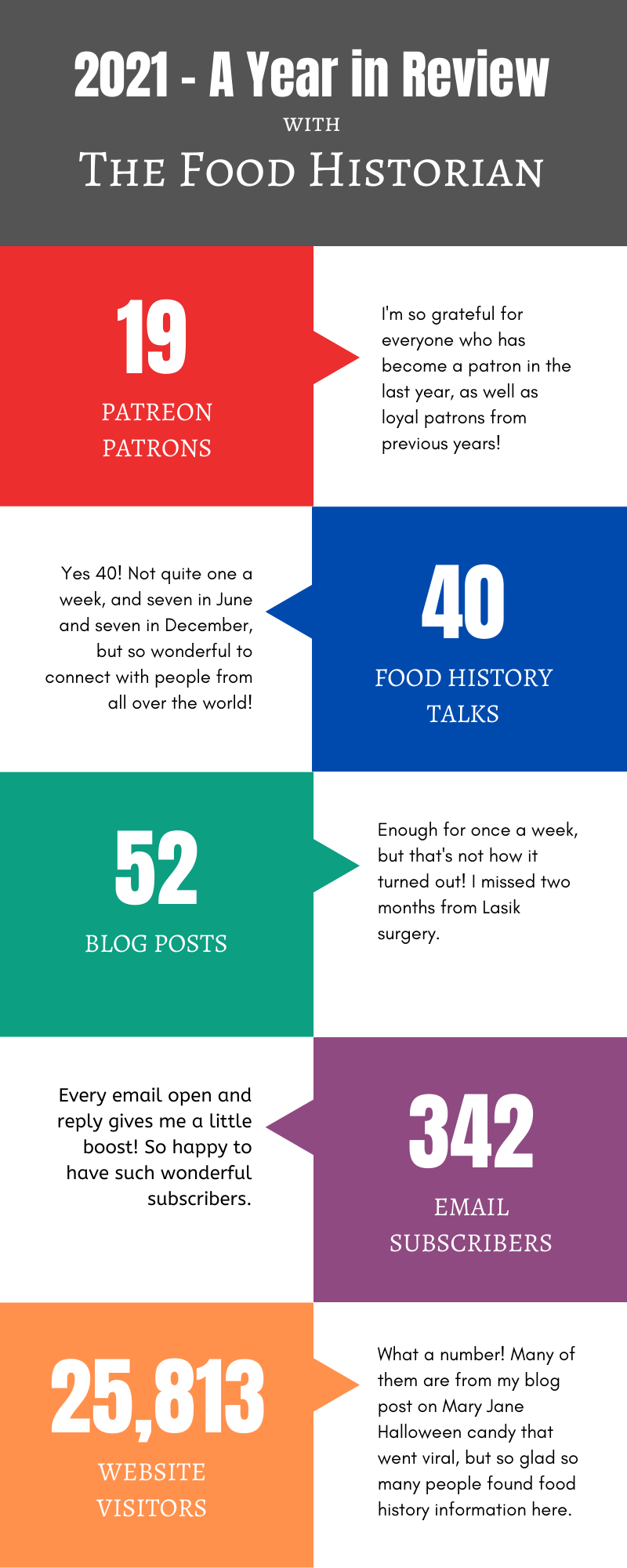

The Food Historian blog is supported by patrons on Patreon! Patrons help keep blog posts like this one free and available to the public. Join us for awesome members-only content like free digitized cookbooks from my personal collection, e-newsletter, and even snail mail from time to time! Don't like Patreon? Leave a tip! It's hard to believe it's already 2022. Another year has come and gone, and we're still in a global pandemic. A few days ago this political cartoon from 1921 was posted on Reddit and a whole host of other social media pages. It ended up in my newsfeed and seemed particularly apt. I've written before on the comparisons between a century ago and today (here and here), but the longer the pandemic drags on, the more the comparisons seem spot on. "A return to normalcy" was the slogan of Warren G. Harding's 1920 political campaign. It promised that Americans could ignore all of the scary things that had happened since 1917, when the U.S. entered the First World War. Although his rhetoric about a return to the mythic, bucolic past (sound familiar?) he won the election by a landslide. Unfortunately for Americans, his strategy of conservative (in the original definition) rhetoric and laissez-faire deregulation after the federal control of World War I ultimately failed. The United States didn't return to pre-WWI normalcy, and while the deregulated economic boom lifted some boats very high, it left other Americans in the lurch and completely on their own. Harding's successors largely followed his economic plans, including World War I Food Administrator Herbert Hoover, who ended up overseeing the crash of 1929 and the onset of the Great Depression. While I don't think we're headed for another Great Depression (for one, our social safety net is far better than the non-existent one of the 1920s), there has been a strong social reaction to the pandemic that is similar - a craving for a return to normalcy of our own, of wanting the pandemic to be over before it is, and of ignoring many of the traumas it has inflicted on us individually and collectively. I've felt that a lot this past year. After the frenetic pace of working on reduced hours through the 2020 lockdown, desperately trying to squeeze everything into fewer hours and pushing myself to be more and more efficient, 2021 has taught me the importance of rest. I'm not always very good at taking it, but these last few weeks I've tried my best to not feel guilty about sleeping in and doing nothing, even as I can't stop myself from commenting on food history memes! 2021 was less frenetic than 2020, but it was a lot. Here's the year by the numbers: Welcome to our new Patreon members, Susan, Elizabeth, Becky, Phyllis, Steve, and Deborah! It's been lovely having your support! I did FORTY separate food history talks in 2021. All but one was virtual, thank goodness, but it meant that being The Food Historian essentially amounted to a second job on top of my museum day job. And although they weren't quite once a week (there was a blank spot in July and August after I got Lasik surgery), I did actually post exactly 52 blog posts in 2021. Those of you on my email list have hopefully enjoyed regular blog posts in your inbox and look at those website visit numbers! A few things didn't make it to the end of 2021 - Food History Happy Hour had to be sacrificed to the lecture gods, sadly. We made it to June, but Lasik surgery derailed things. Although I'm very happy with my new eyes and giving up glasses after 25 years, recovery took longer than expected. Guess it was 2021 telling me to rest again. Despite the two month break, I'm very happy with how many posts I completed! Here's the top ten of the year. Top 10 Blog Posts of 20211. The Real Story Behind the "Gross" Black and Orange Halloween Taffy I posted this one in the fall of 2020 just before Halloween, but it was by far the most popular, racking up over 9,000 unique pageviews. A number of older blog posts were also popular, but this is a review of 2021, so I'm not including the others! 2. Before Nestle: A History of White Chocolate I posted this one on Valentine's Day. And while it was a bit of a slow burn, it was the most popular of my 2021 blog posts. Inspired by a comment about who "invented" white chocolate, it sent me down the research rabbit hole. 3. Visiting Home & a Brief History of North Dakota Caramel Rolls, a.k.a. Dakota Rolls This was my first blog post after Lasik surgery and after a trip home. I hadn't been home in several years, and seeing (and eating!) giant North Dakota-style caramel rolls made me wonder what the history was, but there wasn't much on the internet, so I wrote one! 4. What's the Difference Between Hot Chocolate and Hot Cocoa? With Recipes! One of the first posts of 2021! Posted in conjunction with a talk I do on hot chocolate, this was a fun one to put together, and answered a burning question! 5. When Kitchens Worked: The Rise and Fall of Functional Kitchens This post was inspired by a wonderful 1940s film on YouTube outlining the ideal kitchen layout. I fell in love, and clearly other folks did, too! 6. Meatless Monday: Easy Rice Pudding 2021 was a year for comfort foods, and this simple recipe was one of my favorites. Clearly it resonated with other people, too. 7. World War Wednesday: The Mystery of Carter Housh I originally wrote this post in 2020, but the mystery kept bugging me. In 2021, I decided to revisit Carter Housh's biography, tracking down little snippets and finding as much information as I could! It inspired me to do research on subsequent poster artists for WWI and WWII. 8. Food History, Slavery, and Juneteenth This one was a look into some of the quintessentially American foods created by enslaved people and made accessible by the global slave economy. 9. World War Wednesday: Eat More Milk It's always interesting to see which post make the list, and I think this one is in the top ten solely because of the stunning WWI poster. 10. Making Their Own Way: Black Women Cooks in the 19th Century This was one of my favorite posts of the year, and I'm so glad it made the top 10! It was inspired by the compelling story of the first known published Black woman cookbook author - Malinda Russell. I did also make some progress on last year's goals! Once again the uncertainty of the pandemic and the nation's attempted return to normalcy meant I didn't have a ton of mental space to work on the book, although I have gotten several tasks done and I'm getting ever closer to completion. I did, however, get my bookshelves up and my library organized!  My filled library bookshelves! My filled library bookshelves! Getting my library catalog updated is going to take a little longer (anyone want an internship? Lol.). But having spent the last year working from home two days a week my little garret office is as cozy as can be, with lovely lamps and my matching bookcases, and a little green velvet chair and footstool, and a vintage-looking bluetooth speaker for lovely music. And for Christmas I got an ergonomic cushion for my chair and my husband got me a very fancy second monitor, which will make transcribing newspaper articles and editing videos so much easier! And although getting published in the popular press was NOT one of my goals for 2021, it happened anyway! I was invited to select historic cookies and write about them for TheKitchn.com, and an editor friend asked me to write for a local arts weekly back home. The pieces were published in December and you can find them below:

My goals for 2022 are more modest. Make progress on the book (hopefully finally finish!), keep up the blog, and try to get some more work published. I've got lots of post-book plans, so go to hurry up and turn it in to the editor! A friend of mine chooses a word every year to aspire to. This year I decided to follow suit! My word of the year is "cultivate." Appropriate for a food historian and someone who is hoping to start a garden this spring. But it also represents the slow, steady pace of growing The Food Historian, planting seeds for the future, and, in terms of the book manuscript, weeding! If you pick a word of the year, tell me in the comments! 2021 wasn't a dumpster fire for me, but the last two years have been pretty destabilizing, globally. I hope you'll all be a little kinder to yourselves and the people around you. Try to get some more rest, sleep in, drink lots of water, get outside, stretch every now and again, and do the things you love. Here's to a year of finishing what we start, and making a new beginning, rather than trying to go backwards. Normalcy is overrated. The Food Historian blog is supported by patrons on Patreon! Patrons help keep blog posts like this one free and available to the public. Join us for awesome members-only content like free digitized cookbooks from my personal collection, e-newsletter, and even snail mail from time to time! Don't like Patreon? Leave a tip!

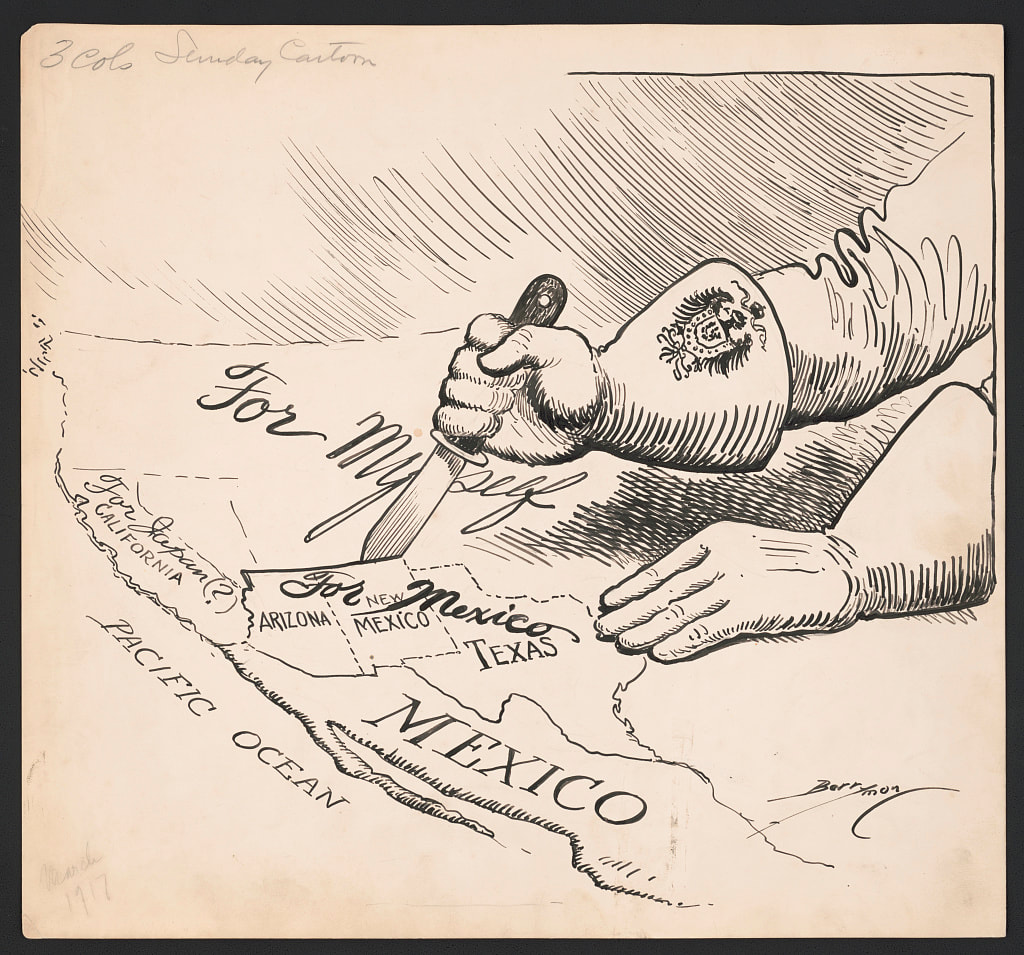

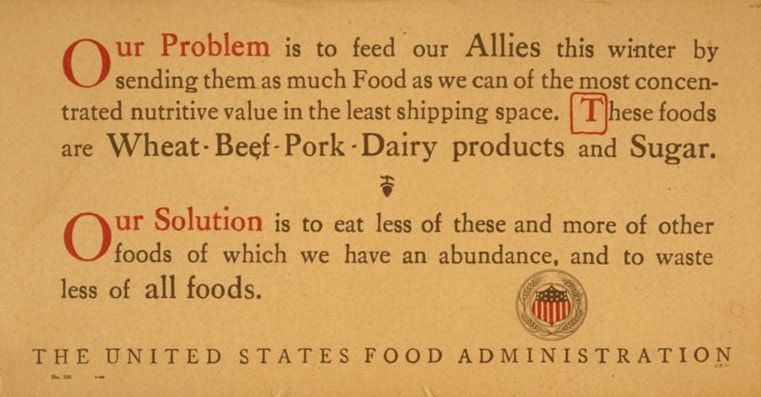

This World War I cartoon shows a hand in a gauntlet (decorated with the imperial German eagle) carving up a map of the Southwestern United States. Arizona, New Mexico, and Texas are labeled "For Mexico." California is labeled "For Japan(?)" The rest of the country is labeled "For Myself." In the spring of 1917, the British government intercepted and turned over to the United States a message from German Foreign Secretary Arthur Zimmerman to the Government of Mexico, urging Mexico to join with Japan and declare war on the United States. Zimmerman suggested that this would be a way for Mexico to reclaim the Southwestern states lost during the Mexican War. American outrage following the publication of the Zimmerman Telegram was one of the factors causing the U.S. to declare war on Germany. Berryman follows the popular notion that the German Kaiser was the force behind German aggression. Illustration by Clifford Kennedy Berryman, March 4, 1917. Library of Congress. On April 2, 1917, President Woodrow Wilson, the man who had won his 1916 presidential reelection by running on the phrase, "He Kept Us Out of War," went before Congress and gave a speech. It was a speech a long time coming. Since Europe had devolved into war in August of 1914, the United States had officially remained neutral. On May 7, 1915, the Lusitania was sunk, the victim of German U-Boats, taking 123 American citizens with it. Despite this attack on innocent civilians, the U.S. remained staunchly neutral. In February, 1917, the Zimmerman Telegram was revealed - an appeal by Germany to Mexico to form an alliance against the United States, should the U.S. enter the war. Sent in January and decrypted by British Intelligence, it was sent just before Germany resumed unrestricted submarine warfare, a tactic they feared would result in the end of American neutrality. And indeed, it did. Unrestricted submarine warfare resumed on February 1, 1917. Wilson gave a speech before Congress on February 3rd, and then again on February 26th regarding U-boats and merchant shipping. On April 2nd, Wilson asked Congress to declare war on Germany. I have called the Congress into extraordinary session because there are serious, very serious, choices of policy to be made, and made immediately, which it was neither right nor constitutionally permissible that I should assume the responsibility of making. On the 3rd of February last, I officially laid before you the extraordinary announcement of the Imperial German government that on and after the 1st day of February it was its purpose to put aside all restraints of law or of humanity and use its submarines to sink every vessel that sought to approach either the ports of Great Britain and Ireland or the western coasts of Europe or any of the ports controlled by the enemies of Germany within the Mediterranean. That had seemed to be the object of the German submarine warfare earlier in the war, but since April of last year the Imperial government had somewhat restrained the commanders of its undersea craft in conformity with its promise then given to us that passenger boats should not be sunk and that due warning would be given to all other vessels which its submarines might seek to destroy, when no resistance was offered or escape attempted, and care taken that their crews were given at least a fair chance to save their lives in their open boats. The precautions taken were meager and haphazard enough, as was proved in distressing instance after instance in the progress of the cruel and unmanly business, but a certain degree of restraint was observed. The new policy has swept every restriction aside. Vessels of every kind, whatever their flag, their character, their cargo, their destination, their errand, have been ruthlessly sent to the bottom without warning and without thought of help or mercy for those on board, the vessels of friendly neutrals along with those of belligerents. Even hospital ships and ships carrying relief to the sorely bereaved and stricken people of Belgium, though the latter were provided with safe conduct through the proscribed areas by the German government itself and were distinguished by unmistakable marks of identity, have been sunk with the same reckless lack of compassion or of principle. (read the whole speech) On April 4, 1917, the Senate voted to declare war. On April 6, the House of Representatives followed suit. The U.S. was now officially at war with Germany.  "Our Problem is to feed our Allies this winter by sending them as much Food as we can of the most concentrated nutritive value in the least shipping space. These foods are Wheat - Beef - Pork - Dairy products and Sugar. Our Solution is to eat less of these and more of other foods which we have in abundance, and to waste less of all foods. The United States Food Administration." c. 1917, Library of Congress. On April 17, 1917, Wilson addressed the nation: I take the liberty, therefore, of addressing this word to the farmers of the country and to all who work on the farms: The supreme need of our own nation and of the nations with which we are coordinating is an abundance of supplies, and especially of food-stuffs. The importance of an adequate food supply, especially for the present year, is superlative. Without abundant food, alike for the armies and the peoples now at war, the whole great enterprise upon which we have embarked will break down and fail. The world's food reserves are low. Not only during the present emergency but for some time after peace shall have come both our own people and a large proportion of the people of Europe must rely upon the harvests in America. Upon the farmers of this country, therefore, in large measure, rests the fate of the war and the fate of the nations. May the nation not count upon them to omit no step that will increase the production of their land or that will bring about the most effectual coordination in the sale and distribution of their products? The time is short. It is of the most imperative importance that everything possible be done and done immediately to make sure of large harvests. I call upon young men and old alike and upon the able-bodied boys of the land to accept and act upon this duty to turn in hosts to the farms and make certain that no pains and no labor is lacking in this great matter. I particularly appeal to the farmers of the South to plant abundant food-stuffs as well as cotton. They can show their patriotism in no better or more convincing way than by resisting the great temptation of the present price of cotton and helping, helping upon a great scale, to feed the nation and the peoples everywhere who are fighting for their liberties and for our own. The variety of their crops will be the visible measure of their comprehension of their national duty. The Government of the United States and the governments of the several States stand ready to coordinate. They will do everything possible to assist farmers in securing an adequate supply of seed, an adequate force of laborers when they are most needed, at harvest time, and the means of expediting shipments of fertilizers and farm machinery, as well as of the crops themselves when harvested. The course of trade shall be as unhampered as it is possible to make it and there shall be no unwarranted manipulation of the nation's food supply by those who handle it on its way to the consumer. This is our opportunity to demonstrate the efficiency of a great Democracy and we shall not fall short of it! This let me say to the middlemen of every sort, whether they are handling our food-stuffs or our raw materials of manufacture or the products of our mills and factories: The eyes of the country will be especially upon you. This is your opportunity for signal service, efficient and disinterested. The country expects you, as it expects all others, to forego unusual profits, to organize and expedite shipments of supplies of every kind, but especially of food, with an eye to the service you are rendering and in the spirit of those who enlist in the ranks, for their people, not for themselves. I shall confidently expect you to deserve and win the confidence of people of every sort and station. (read the entire speech) Wilson's emphasis on food was not without warrant. The U.S. and Argentina, the two major wheat-exporting countries in the Western hemisphere (excepting Canada), had both experienced poor harvests in 1916, after bumper crops in 1914 and 1915. In short, when the U.S. entered the war in April of 1917, it had only enough wheat for domestic consumption. Although the initial rollout of food regulation was uneven, in large part due to the fact that Congress blocked funding of the United States Food Administration until August of 1917, calls for voluntary reduction in consumption of certain foods, like those listed in the poster above, were almost immediate, as were calls to reduce food waste and increase food production. Wilson knew that defeating German aggression meant putting the United States' abundant resources to work - agricultural land, people, and industry. As with all wars, he who controls the food supply, controls the outcome of the war, something that proved true with the First World War as much as any war, and one in which the United States made a huge difference. The Food Historian blog is supported by patrons on Patreon! Patrons help keep blog posts like this one free and available to the public. Join us for awesome members-only content like free digitized cookbooks from my personal collection, e-newsletter, and even snail mail from time to time!

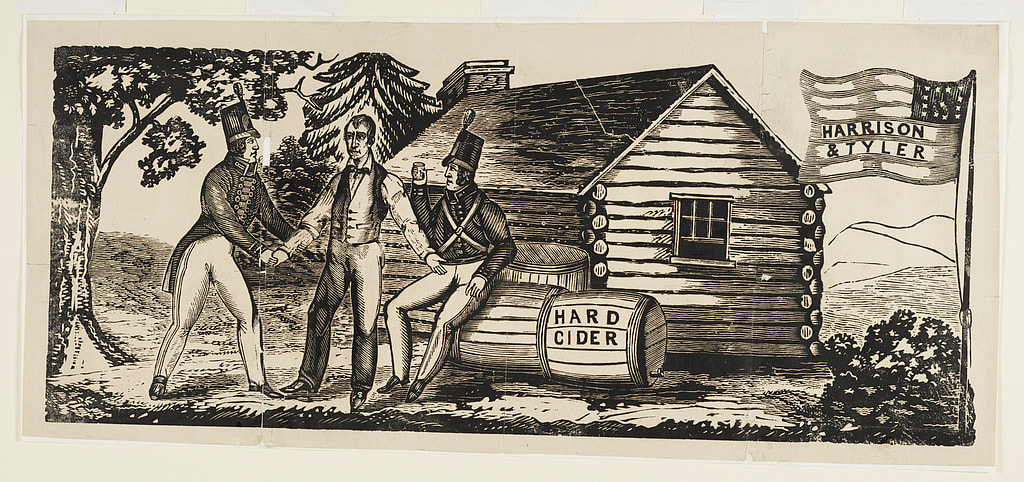

An untitled woodcut, bold in design, apparently created for use on broadsides or banners during the Whigs' "log cabin" campaign of 1840. In front of a log cabin, a shirtsleeved William Henry Harrison welcomes a soldier, inviting him to rest and partake of a barrel of "Hard Cider." Nearby another soldier, already seated, drinks a glass of cider. On a staff at right is an American flag emblazoned with "Harrison & Tyler." Library of Congress.

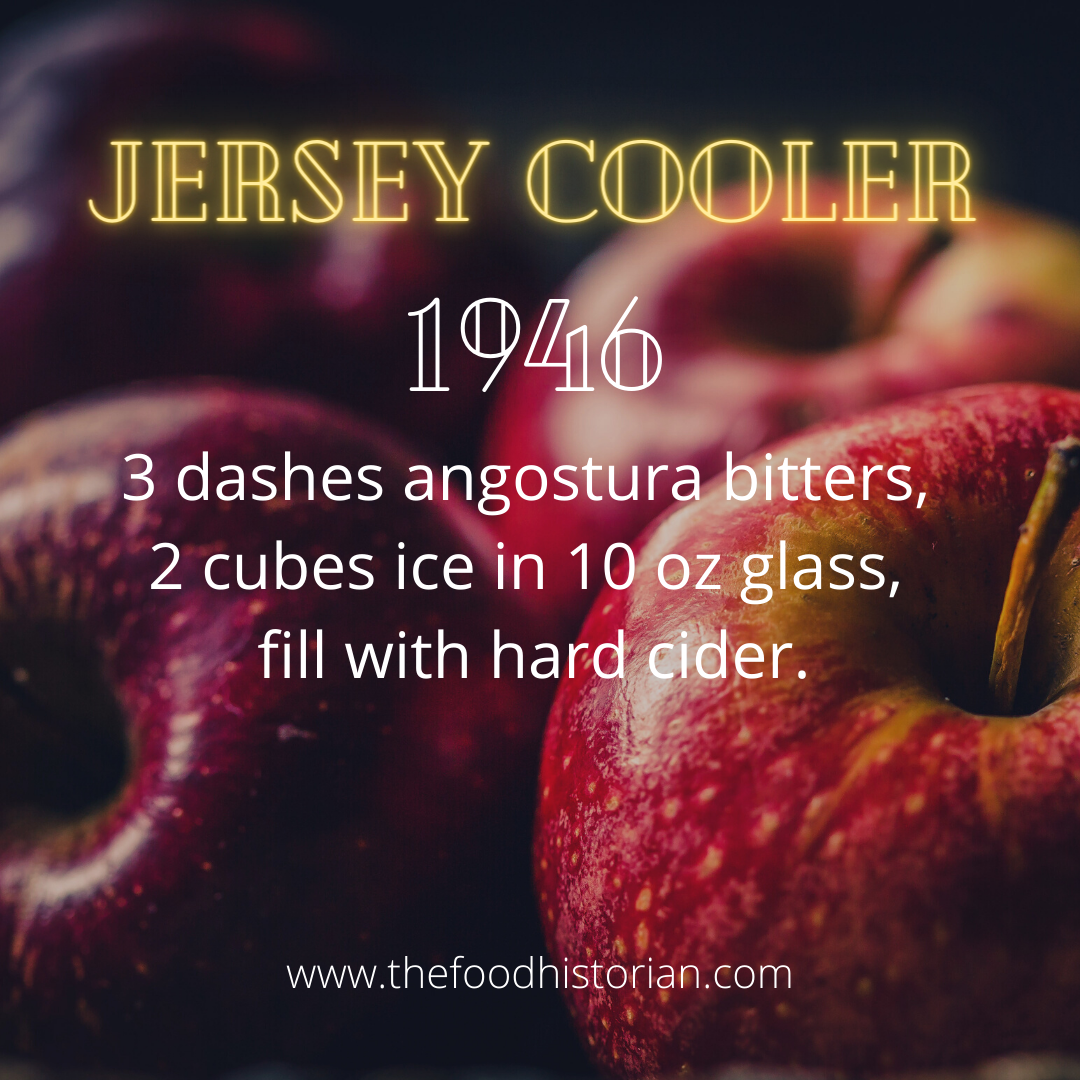

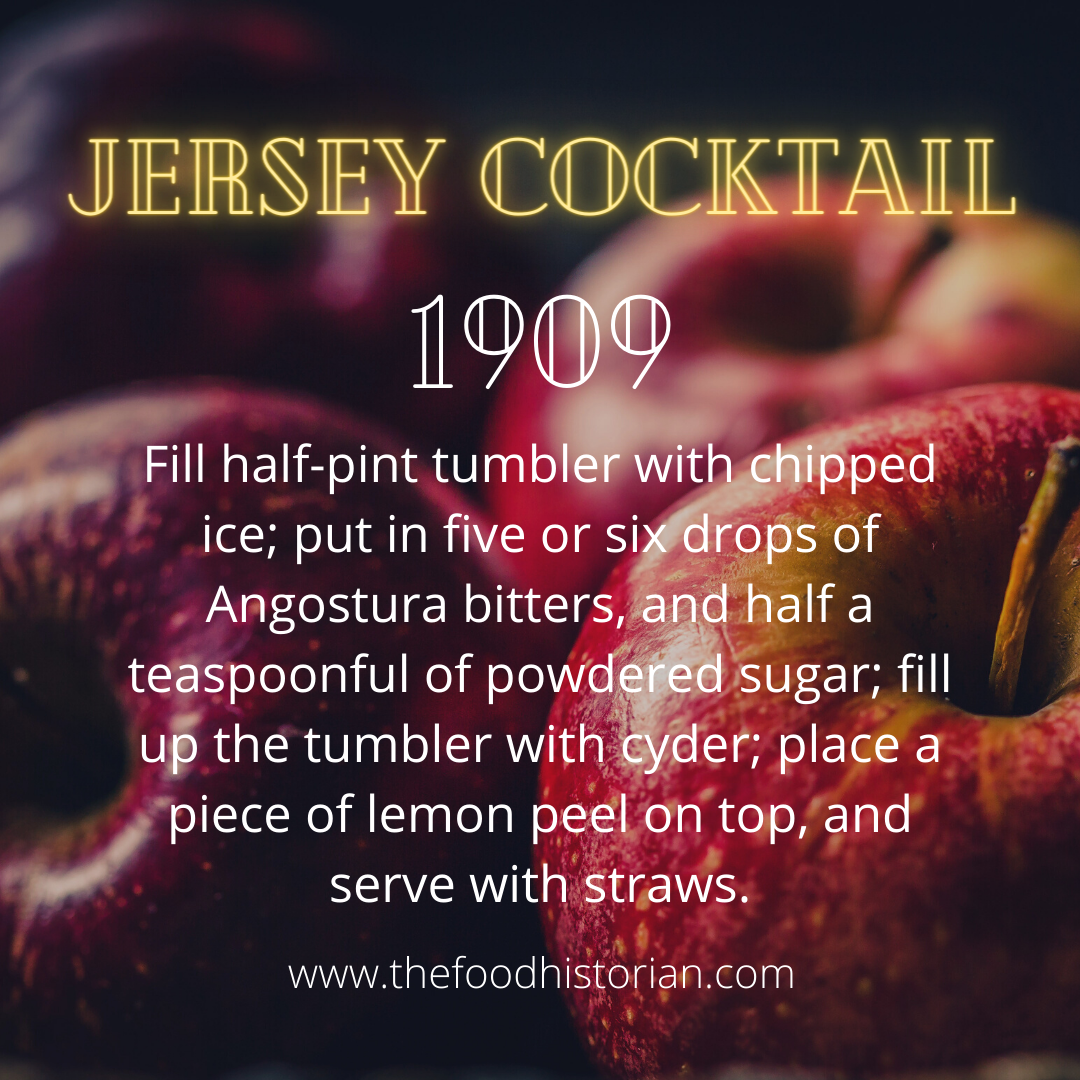

Thanks to everyone who participated in this week's Food History Happy Hour! In this episode we made the Jersey Cooler from the Roving Bartenter (1946), but the cocktail itself appears to have been invented by the famous Jerry Thomas as it appears in his 1862 How to Mix Drinks.

With the primary ingredient hard cider, I thought it a particularly apt cocktail for our discussion of apples in America! I chose apples as the topic for tonight's Food History Happy Hour because mid-September is when apple harvest in the Northeast usually really starts to get underway. Coincidentally (on my part, anyway), tonight is also the start Rosh Hashanah, or the Jewish New Year, which runs until Sunday. One of the components of Rosh Hashanah is the use of apples and honey, particularly in Ashkenazi Jewish households, who originate in Eastern Europe. Apples and honey are eaten to symbolize sweetness and prosperity for the coming year. On a more somber note, I learned that Supreme Court Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg passed away just minutes before the start of the show. In fact, I almost didn't do tonight's episode because I was so upset. But I figured that the notorious RBG would power through if it was her, and it was fitting to be talking about apples and hoping for peace and prosperity in the coming New Year. So we poured one out for Ruth and gave her a toast. We talked about the origins of hard cider, with an aside about the 1840 presidential campaign of William Henry Harrison, why hard cider fell out of favor, the origins of apples in the mountains of Kazakhstan, Johnny Appleseed, the story of Red Delicious, heirloom apple varieties, and the not-so-American origins of apple pie. Jersey Cooler (1946)

From the 1946 Roving Bartender by Bill Kelly:

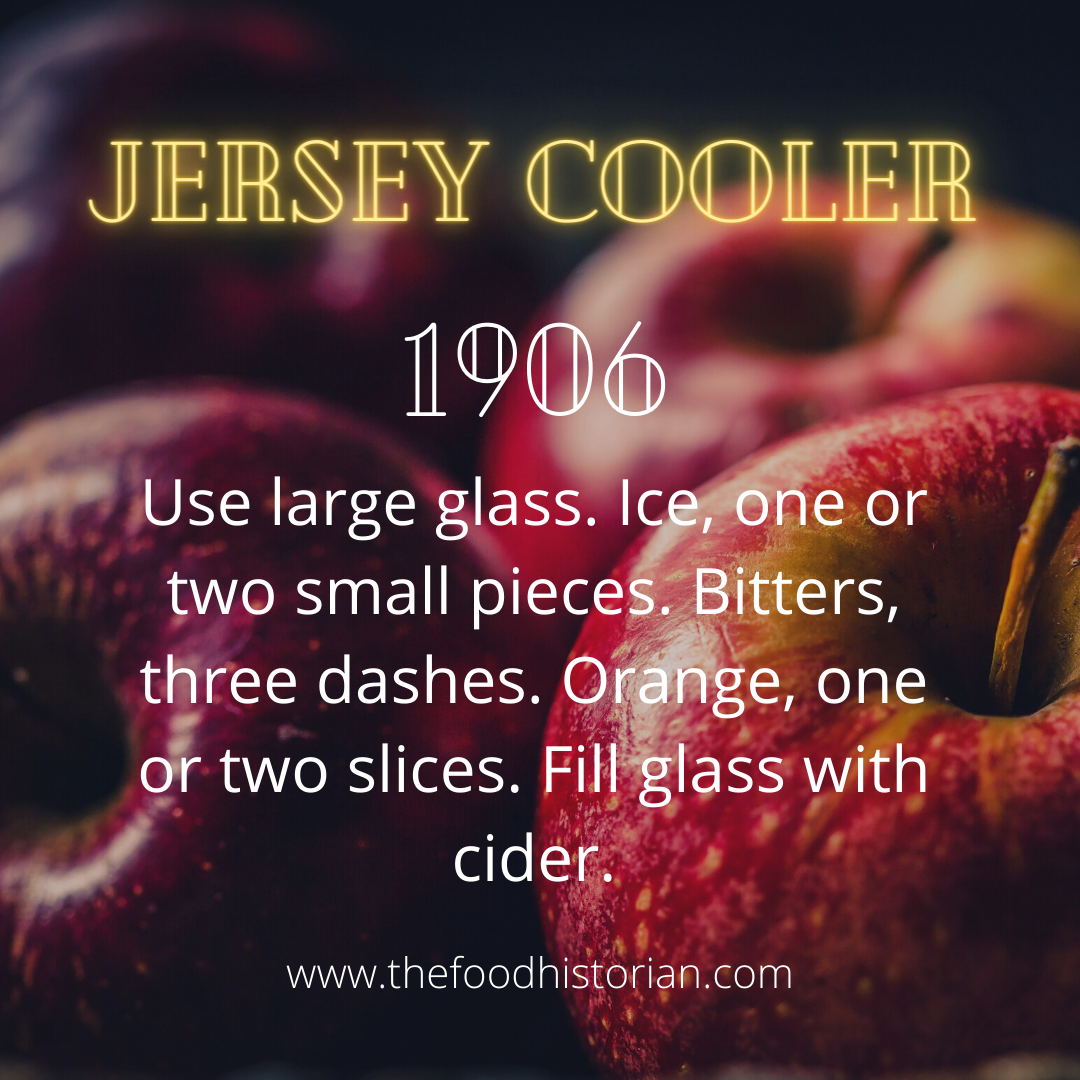

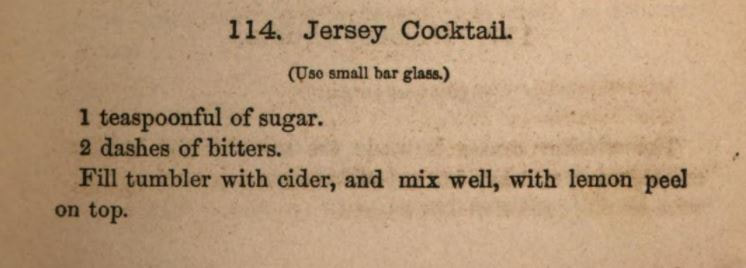

You can see other, slightly more complicated versions below: Jersey Cocktail (1862)

As far as I can tell, this is the oldest version of the Jersey Cooler (called cocktail here), invented by the famous Jerry Thomas from his How to Mix Drinks from 1862. Because the earliest reference is from Mr. Thomas, who was a born and raised New Yorker, I think that the "Jersey" in this instance refers to New Jersey, not Jersey, England.

Here's his recipe: (Use small bar glass.) 1 teaspoonful of sugar. 2 dashes of bitters. Fill tumbler with cider, and mix well, with lemon peel on top. Episode Links

Our next episode will be on Friday, October 2, 2020 and since it will officially be October, we'll be talking about pumpkins and the origins of the much-maligned pumpkin spice!

If you enjoyed this episode of Food History Happy Hour and would like to support more livestreams, please consider joining us on Patreon. Patrons get special perks like access to members-only content.

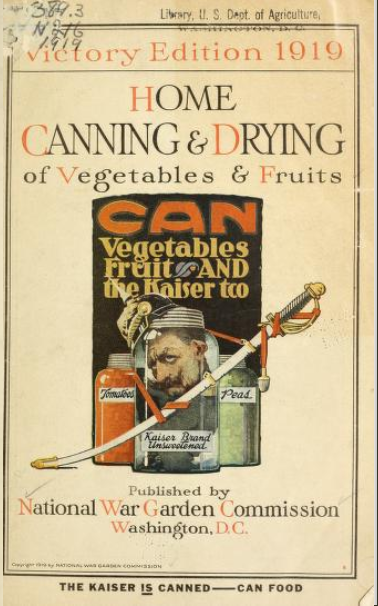

"Can Vegetables, Fruit, and the Kaiser, Too. Write for Free Book to National War Garden Commission, Washington, D.C." September is still preserving time, so I thought the next few World War Wednesdays would be about canning. This is another of my favorite World War I propaganda posters. Developed by the National War Garden Commission, the poster shows glass jars with zinc tops. Tomatoes at left, peas at right, and front and center, the profile of Kaiser Wilhelm II, German Emperor and King of Prussia. His spiky German helmet and saber hang on the jar, which is labeled "Monarch Brand, Unsweetened." Eminently clever, the poster implies that home preserving has the power to defeat the might of the German Empire and the Kaiser himself. The First World War was one of the first times that ordinary Americans were called upon to preserve food in their homes. Many Americans, especially those in rural areas, were already canning and preserving the bounties of their home gardens. But as commercial canning became increasingly widespread, inexpensive, and safer, people with easy access to food retailers found it much easier to simply purchase canned goods, instead of going through the bother of putting up their own. Many people were still using the tried-and-true, but not necessarily safe, methods of their forebears. And while water bath canning was increasingly outpacing the traditional food preservation methods of fermentation, drying, and sealing jam with paraffin wax, water bath canning low acid vegetables still was not 100% safe. But as the government encouraged food conservation and food preservation, the National War Garden Commission stepped up to the plate. Founded (and funded) by timber magnate Charles Lathrop Pack, the National War Garden Commission published a series of food preservation pamphlets that were used all over the country by home economists and women's groups to encourage home canning. The National War Garden Commission was also behind the school garden movement, but that's another post. The Commission would go on to produce a number of pamphlets on war gardening (renamed "Victory Gardening" post-war, a term that would be revived during the Second World War), including one pamphlet entitled "The War Garden Guyed," published in 1918. A clever play on words ("to guy" someone was to make fun of them, or ridicule), the "Guyed" contained cartoons, poems, and slogans both promoting and making fun of the gardening and food conservation movements. Submitted by newspaper editors, soldiers in the trenches, magazines, and ordinary people, the collection is quite a fun read, and not the only version the National War Garden created. "Raking the Gardener and Canning the Canner" predated "The War Garden Guyed" by one year - published in 1917, a quick turnaround indeed and indicates how quickly ordinary people adjusted to the idea of home gardening and canning. You can view almost all of the National War Garden Commission pamphlets on archive.org. In 1919, the National War Garden Commission used the "Can the Kaiser" poster image again, this time on their revamped "Home Canning & Drying of Vegetables and Fruits," rebranded "Victory Edition" post-war. At the bottom of the cover, it reads, "The Kaiser IS Canned." Although the fervor for home canning, thrift, and self-sufficiency continued into 1919 and 1920, by the time economic prosperity had returned full-force to give us the Roaring Twenties, most ordinary people who took up canning for the war effort abandoned it in victory. But I like to think that many of the food preservation lessons learned during the First World War would be revived and put to good use by the time the Second World War rolled around. If you enjoyed this installment of #WorldWarWednesdays, consider becoming a Food Historian patron on Patreon! Members get access to patrons-only content, to vote for new blog post and podcast topics, get access to my food library, research advice, and more! I ran across this little political cartoon when researching for my book Preserve or Perish, which is about food in New York during the First World War. I also study wedding food traditions, so of course when I saw this, I cracked up.

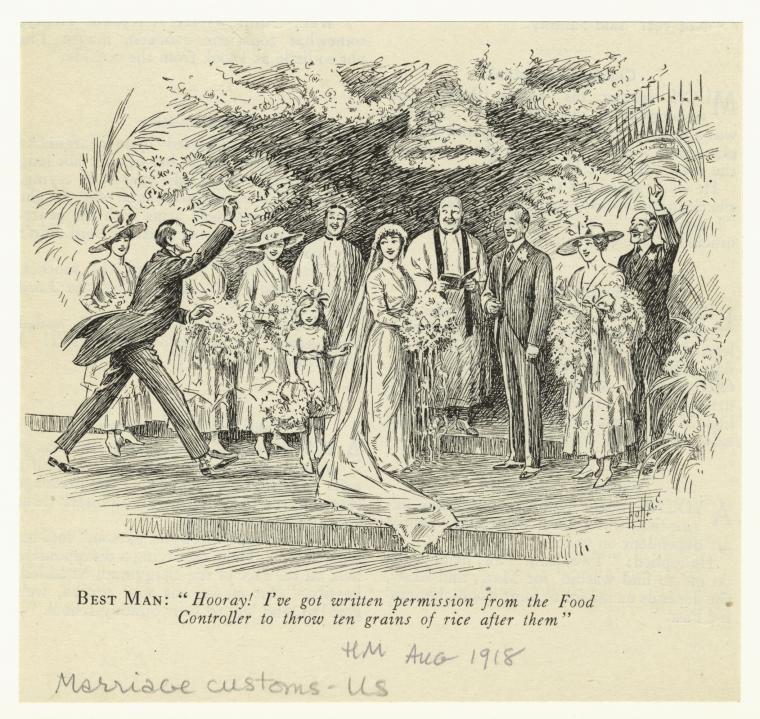

A wedding party is gathered at the altar, and everyone is turning to look at the best man, who is rushing up to the altar waving a piece of paper. The caption reads, "BEST MAN: 'Hooray! I've got written permission from the Food Controller to throw ten grains of rice after them.'" Although the New York Public Library doesn't list what newspaper or magazine it is from, it is dated as August, 1918. The cartoon is hilarious for a number of reasons, but the primary one is that it is a gross exaggeration of the level of food control in the United States during the First World War. With the exception of sugar toward the end of the war, mandatory rationing was never put into place for ordinary Americans. Only food producers and retailers had restrictions placed on them. On potential exemption from that (besides sugar) was the requirement that all customers had to buy two units of non-wheat grains or flours for every one unit of wheat they purchased. For example, by purchasing one pound white wheat flour, a shopper would be required to purchase an additional two pounds of some other grain (they could mix and match) such as cornmeal, rye flour, barley flour, rice, or oatmeal. Rice, however, was never rationed. In fact, although it was not as widely available as cornmeal, it was touted as a wheat substitute. But political cartoons are all about taking things to extremes, so the joke is that food is so heavily "controlled" that even a few grains of rice must have permission to be thrown away. Which also fits into the propaganda around wasting food that was prevalent at the time. The other interesting, although not particularly hilarious, commentary of this cartoon is that this is clearly a fairly wealthy family. Then men are wearing morning coats with tails and spats on their shoes. The bridesmaids are in matching outfits. The bride has a very long veil and there are flowers and greenery galore. It indicates that even the wealthiest Americans could not escape the reach of the "Food Controller" - a.k.a. Herbert Hoover, Federal Food Administrator (a term he vastly preferred to "controller" or even the popular-in-the-press "dictator," which did not have quite the same meaning then as it does now). The early 20th century was when marriage traditions were starting to solidify as weddings became more formal, public affairs. Throwing rice at the couple at the end of the wedding was one of those "traditions" at this point. Along with a white dress, flower bouquet, white bride's cake to eat at the breakfast (yeah, they were still breakfasts at this point, although luncheons and teas were becoming more common) and spice/fruitcake groom's cake to take some as a favor. In all, it's a cute-but-biting commentary on food control during the First World War. And it made me laugh, so I had to share. If you enjoyed this installment of #WorldWarWednesdays, consider becoming a Food Historian patron on Patreon! Members get to vote for new blog post and podcast topics, get access to my food library, research advice, and more! |

AuthorSarah Wassberg Johnson has an MA in Public History from the University at Albany and studies early 20th century food history. Archives

July 2024

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed