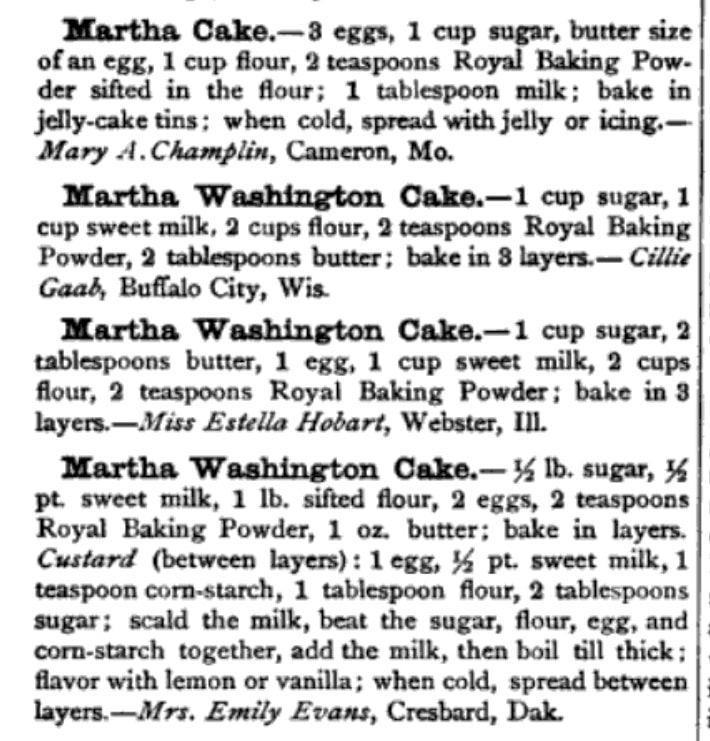

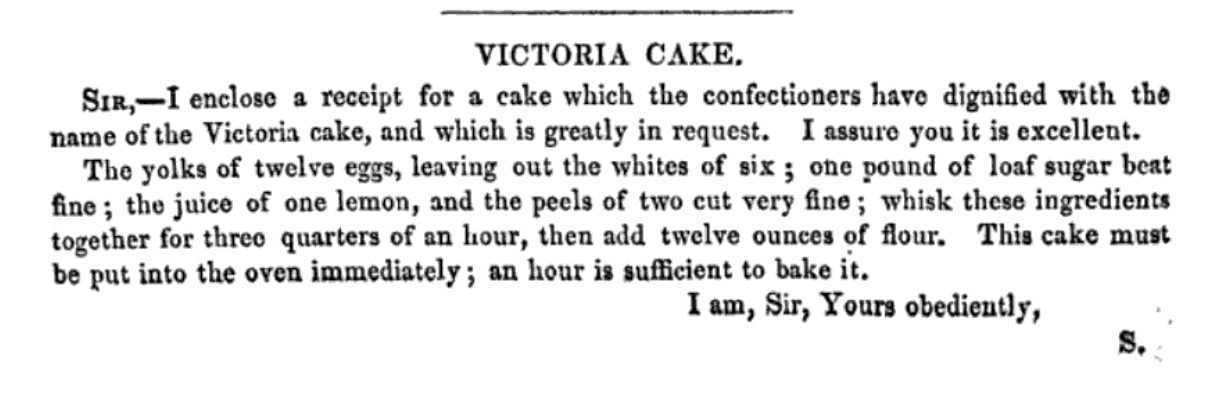

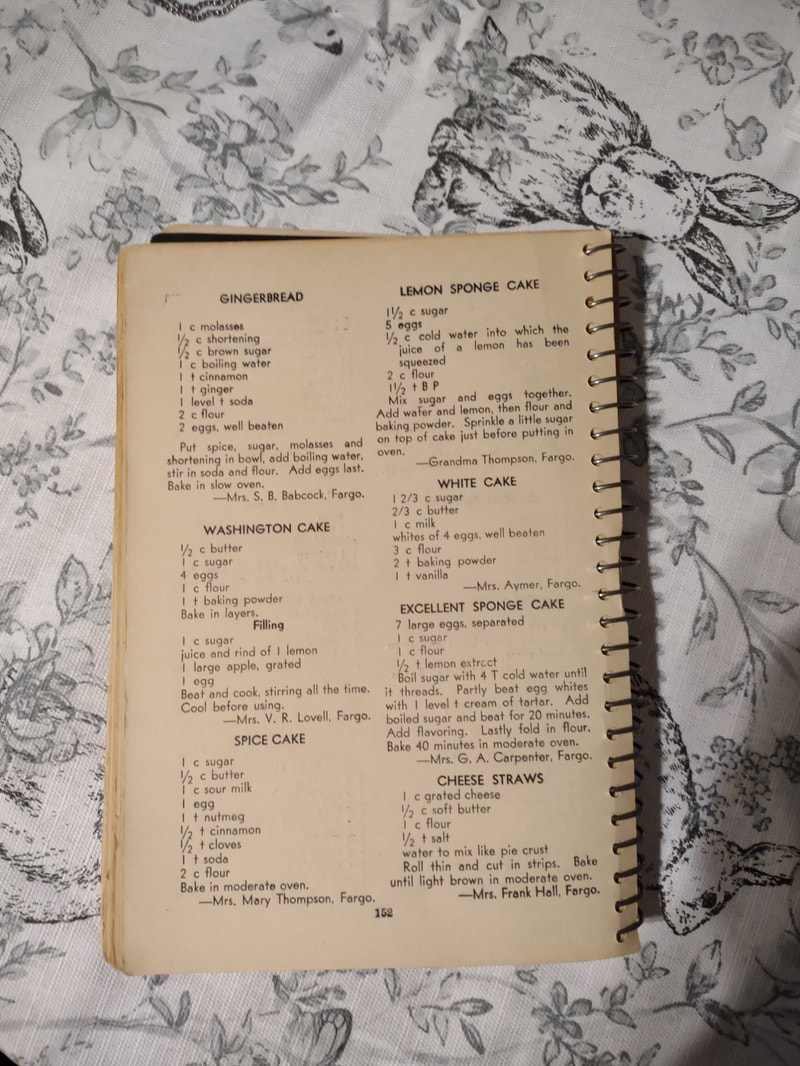

Washington Pie HistoryWashington pie is everywhere in 19th century cookbooks. Confusingly, it is not a pie. Gastro Obscura traced the history of Washington pie, but spoiler alert - it was called a pie because it was baked in tin pie pans, which back then had straight sides similar to modern cake pans. WHY it was named after George Washington isn't clear - and the earliest references we can find date to 1850. Gastro Obscura and Patricia Reber trace it back to Mrs. Putnam's Receipt Book and Young Housekeeper, by Elizabeth H. Putnam and published in 1850. But I found another reference from 1850, the Practical Cook Book by Mrs. Bliss (of Boston), also published in 1850, for "No. 1 Washington Cake," which included the note "This cake is sometimes called WASHINGTON PIE, LAFAYETTE PIE, JELLY CAKE, &c." Mrs. Bliss' recipe is preceded by the lovely-sounding "Virginia Cake," which calls for sieved sweet potato and molasses, and "Victoria's Cake," which is a lemon-flavored sponge cake with no mention of the jam and cream commonly found in Victoria Sponge. I did find several earlier references to "Washington Cake," many of which were more a type of white fruit cake with currants (Mrs. Bliss' "No. 2 Washington Cake" is of this type), not a layer cake with jelly, with one exception. "Washington Cake" in Mrs. T. J. Crowen's 1845 Every Lady's Cook Book calls for a similar style cake flavored with lemon and brandy. However it does not say to bake it in layers, nor fill it with jam or jelly. But let's take a harder look at that "Layfayette Pie" reference from Mrs. Bliss. Lafayette Pie, Martha Washington Pie or Cake HistoryAlthough Washington Pie is traditionally made with only jam or jelly, there was another variation that shows up later: the Lafayette or Martha Washington Pie/Cake. Similar to Washington Pie, both "pies" are a simple cake baked in thin layers, but instead of filled with jelly or jam, are filled with custard (or more rarely, whipped cream). Confusingly, though the majority of references to Lafayette Pie and Martha Washington Pie call for custard, I have seen occasional references to jelly options, too. The above recipes, from My Favorite Receipt, published by the Royal Baking Powder Company in 1886 is one of the earliest references I can find to Martha Washington Cake/Pie. The first one, called just "Martha Cake" calls for it to be baked in "jelly-cake tins" and spread with "jelly or icing." The next two recipes are identical, and call for the cake to be baked in three layers, but no reference to fillings. The final version (from a North Dakotan!), is the one which also lists the cooked custard filling, to be flavored with vanilla or lemon. The earliest reference I could find for "Lafayette Pie" is Mrs. E. Putnam's 1867 version of her Mrs. Putnam's Receipt Book, which follows the Washington Cake recipe with "Lafayette Pie," a rather less precise recipe than Washington's, which is "enough for two pies" and is followed with "Filling for the Above Pies," seeming to mean both Washington and Lafayette. It reads "Two ounces of butter, quarter of a pound of sugar, two eggs, and one lemon; beat all together without boiling." At first, I read this to mean uncooked, but instead it must mean heated but not boiled - essentially a rich, lemon-flavored custard. The Methodist Cook Book, published in 1899, contains a recipe for "Lafayette Pie," which calls for being baked in a "Deep pie plate," and then cut in half lengthwise (confusingly, it says to "cut out the center to make room for the filling") and filled with a cornstarch-egg custard. Just like Martha's. Boston Cream Pie History As far as I can tell, Lafayette Pie and Martha Washington Pie/Cake are essentially the same: a simple layer cake baked in pie tins and filled with cooked custard. Sound familiar? Recipes called "Boston Cream Pie" were for decades exactly the same - a thin plain layer cake filled with a cooked custard. Contrary to what Gastro Obscura claims, when Americans made Boston Cream Pie at home in the 19th century, it was WITHOUT a chocolate topping. None of the 19th century recipes I could find titled "Boston Cream Pie" (and there were many) contain chocolate at all - only one Maria Parloa recipe calls for chocolate, and that is named "Chocolate Cream Pie." Chocolate-free Boston Cream Pie recipes continue to be published into the 1940s. As far as cookbooks go, Boston Cream Pie doesn't morph into the chocolate-topped version until the 20th century. The Home Dissertations cookbook, published in 1886, includes a recipe for "Boston Cream Pie" among its pastry recipes, even though it is clearly a cake. It calls for the cake to be baked in "round tins so that the cake will be one inch and a half thick" and filled with a cooked custard made with eggs and cornstarch, flavored with vanilla or lemon. No chocolate in sight. How or why all of these "pies" which are really cakes got their names remains lost to history. Likely, the cake was baked in honor of Washington's birthday, or other patriotic occasions. Washington's Birthday became a federal holiday in 1879, which may explain the popularity of the cake at the end of the 19th century. Lafayette and Martha likely followed as other patriotic homages. Other political figures also got their due, like this "Mrs. Madison's Cake" from 1855, which lists just above a white fruitcake-style "Washington's Cake," "Madison Cake" from 1856, and "Mrs. Madison's Whim," a similar-style cake "good for three months" stays in print as late as 1860. Even Jefferson got his own cake, although only in one 1865 edition of Godey's Magazine, and it reads more like a sweet biscuit than a true cake. Political cakes may have been a thing in the 19th century, because the 1874 The Home Cook Book of Chicago has an Adams Cake, a Clay Cake, two Harrison Cakes, and a Lincoln Cake, and the Adams and Clay cakes (named for President John Adams and Senator Henry Clay, one presumes) read very much like Washington Pie. There are also TWO recipes for "Washington Pie," one of which has a filling that includes apples. I could only find one other "Lincoln Cake" in the 19th century, published in 1863. And Boston? It could be that the patriotic cakes were simply popular in Beantown, which leant its name as the "pies" spread elsewhere (a la Boston Brown Bread, Boston Baked Beans, etc.). Certainly the Parker House Hotel in Boston claims to have invented Boston Cream Pie, although I've yet to see any hard evidence (like a recipe or period description) that indicates it had a chocolate topping in the 1860s. Victoria Sponge Cake HistoryWashington Pie really is quite similar to Victoria Sponge, which if you're a fan of the Great British Bakeoff, you know is one of Britain's (and Queen Victoria's) favorite desserts. And, ironically, not actually a sponge cake, as it calls for butter (true sponge cakes have no fat). Likely developed in the late 1840s, coinciding with the development of baking powder in 1843, and adopted by the Queen in mourning in the 1860s. Like Washington Cake, some of the first references to "Victoria Cake" are much closer to a white fruitcake or pound cake than a sponge, like this recipe from 1842, or this recipe from 1846 by Francatelli. The first recipe to a sponge-style Victoria Cake comes in 1838, the year after she became queen (recipe pictured above) from The Magazine of Domestic Economy. Although it does not call for filling of either jam nor whipped cream. The oft-cited recipe published in The Practical Cook (1845), is identical to the 1838 recipe, down to the letter. Of course, Mrs. Bliss' "Victoria's Cake," published in 1850, while not identical to the letter, is certainly just a slightly re-worded copy. Despite the popularity of the sponge, "Victoria's Cake" continues to be the yeasted fruitcake that Francatelli and later Soyer keep pushing well into the 1860s. "Victoria Sandwiches" come into play in the 1850s, whereby pieces of sponge cake are sandwiched with jam and topped with pink icing, a la The Practical Housewife, published in 1855 by Robert Kemp Philp. Ridiculously, Francatelli's version of "Victoria Sandwiches" are a literal sandwich, made with hard boiled egg and anchovies. Not quite as flattering to the queen. Mrs. Beeton wisely hops on the sponge cake "Victoria Sandwiches" bandwagon in the 1860s. Although curiously none of these early recipes call for whipped cream to accompany the jam. Perhaps because Mrs. Beeton's recipe for Victoria Sandwiches is immediately followed by one for Whipped Cream, maybe someone put two and two together. Which cake was inspired by whose we'll perhaps never know. Unless some manuscript cookbook has in it somewhere "Washington Pie, from Victoria's Cake" or "Victoria Sandwiches, in the style of Washington Pie." Regardless, it was the exact right kind of cake to associate with heads of state, apparently, once everyone got over heavy white fruit cakes laden with lemon and currants and alcohol. In making a birthday brunch for a friend, I wanted to focus on vintage recipes and had Washington Pie already in mind. But unwilling to use the internet (cheating!), I instead consulted my historic cookbooks. I had been on the lookout for another recipe, when I found a recipe for "Washington Cake" in one of my North Dakota community cookbooks, this one dating to the 1940s: The North Dakota Baptist Women's Cook Book. The cookbook does not have a publication date, but there is a reference to 1947 in the frontspiece, and from that and judging by the style of font and print, we can safely date it to the late 1940s, possibly 1950, but not much later. Interestingly, the recipe for Washington Cake was in a section in the back called "1905 Recipes" and dedicated to the women of the First Baptist Church of Fargo, ND, which was built in 1905. The recipes that follow were all written by women of the church for that first construction - likely from an older cookbook. The dedication reads, "In loving memory of those who have made a very definite contribution to the Christian cause through their labors in the First Baptist Church of Fargo, N. D., and who have left behind them fruits that are being utilized in this book, this page is gratefully dedicated." It then lists two biblical references to death and a list of women's names. The recipes read as much older than 1905, with emphasis on things like brown bread, suet pudding, doughnuts, gingerbread, and mincemeat. Likely they were submitted as "colonial" or similar "old-fashioned" recipes that were part of the popular colonial revival that began at the turn of the 20th century. The recipe for "Washington Cake" was contributed by Mrs. V. R. Lovell of Fargo, ND. It reads: 1/2 c butter 1 c sugar 4 eggs 1 c flour 1 t baking powder Bake in layers. Filling 1 c sugar juice and rind of 1 lemon 1 large apple, grated 1 egg Beat and cook, stirring all the time. Cool before using. Not exactly the most descriptive recipe I've ever read, but better than many! I decided not to use the interesting-sounding filling, although I may revisit it at a future date. Instead, I wanted to go the jam-and-cream route. 1905 Washington Cake (or Pie), AdaptedUnlike a traditional sponge cake, which can be quite finicky with separating egg whites, I found this recipe to be just as delicious, but much simpler. As an added bonus, you don't have to split a taller cake evenly lengthwise - the layers are already thin enough to stack as-is. You can use any kind of jam, but I chose my favorite brand of strawberry. 1/2 cup butter 1 cup sugar 4 eggs 1 cup flour 1 teaspoon baking powder 1 teaspoon vanilla (or lemon or extract) Strawberry jam Whipped cream Preheat the oven to 350 F. Butter well two round cake pans. Cream but the butter and sugar together, then add the eggs one at a time, beating after each addition. Add the vanilla (or lemon), then the flour and baking powder, then mix well until everything is well combined. Pour equal amounts into the two cake pans, then bake on the center rack for approximately 30 minutes (check after 20 - when the cake is golden at the edges and the center springs back to the touch, it is done). Tip the cakes out of their pans onto a cooling rack and let cool completely. Then spread strawberry jam on one layer, and top with whipped cream (I stabilized mine with cornstarch - which you could taste, so I would not recommend doing that again), then add the second layer, more strawberry jam, and more whipped cream. If you want this cake to keep better, I would recommend going the traditional Washington Pie route and just filling thickly with strawberry jam, and serving it with whipped cream on top to taste. This cake is very easy, bakes relatively quickly, and tasted delicious. It was VERY sweet, so I might cut back on the sugar slightly if I make it again. But while I'm sure Great British Bakeoff experts would criticize the fact that I didn't weigh my ingredients or make sure my eggs were room temperature, I thought the cake turned out very lovely indeed. And the combination of cake, whipped cream, and sweetened fruit can never be wrong. As for all the other political cakes? I may have to do some more investigative baking for Presidents' Day 2023. The Food Historian blog is supported by patrons on Patreon! Patrons help keep blog posts like this one free and available to the public. Join us for awesome members-only content like free digitized cookbooks from my personal collection, e-newsletter, and even snail mail from time to time! Don't like Patreon? You can leave a tip!

0 Comments

A while ago I made cherry bounce. It's a very old-fashioned drink that was apparently much-beloved by George Washington. I speculated about George and cherries even longer ago, in a post that remains today one of my top-viewed posts. You see, cherries are not even remotely in season in February, and George was a lover of walnuts. Although he preferred English walnuts, black walnuts were easier and cheaper to get. I live nearby where George was stationed during the end of the Revolutionary War. And there are black walnut trees a-plenty in my area. I've thought about harvesting them, but they're so fussy and difficult, and my days so busy, that I've never bothered. I leave them to the squirrels, who seem to cleverly leave them in our driveway so our cars will crack them for them. They then carry them to a shallow stone in our lawn to finish cracking them open. This President's Day weekend I worked on the Saturday, went to a friend's birthday party (she got her own quart of bounce and a pair of tiny brandy glasses for a present), had errands to run on Sunday, and worked on the holiday Monday. So it was just the other day that I got to enjoy a small (and very 18th century looking) glass of the cherry bounce. I even lit a candle for George, Abe, and all my other favorite presidents (including Teddy Roosevelt, of course). My husband thinks it tastes like cherry cough medicine, and I'll admit the brandy is a bit strong. Gives you a lovely warm feeling if you're cold, that's for sure. But you do get just a slight sweetness (I used much less sugar than the historic recipe) and a nice bright sour cherry taste. The color is also absolutely beautiful and comes just from the fruit - no artificial colors here! Next time, I think I'll pack the jar right full of sour cherries for a stronger cherry taste. And maybe spend just a smidge more money on the brandy. :D Cheers, all. If you liked this recipe and want to see more, consider becoming a member of The Food Historian or supporting us on Patreon. Remember my post about George Washington and cherries in February? It's been one of my most popular. And while yes, you can totally still make walnut pie or have pickled walnuts with cheese and Madeira in February, you can also take the time right now to make yourself some Cherry Bounce.

What is cherry bounce, you ask? It's basically brandy, cherries, and sugar, and it was a favored 18th century drink. My in-laws have a now quite grown up sour cherry tree (Montmorency, I think) that was just LOADED with sour cherries when we were up the other weekend. Sour cherries, also known as sour pie cherries, are not as sour as, say, rhubarb, but definitely need a little sugar as they are nowhere near as sweet as the sweet black or Queen Anne cherries you often find in grocery stores this time of year. They're also far more delicate, so if you're going to pick them, please pick them with the stem on, unless you plan to process them right away. Martha Washington's recipe is available thanks to the Mount Vernon estate, but I didn't have 10 pounds of cherries, and while mine probably weren't Morellos, Montmorencies are a sub-genus of Morellos. I also thought 3 cups of sugar to 4 cups of brandy was pretty high. That's borderline syrup territory, for my taste. Considering I wanted to use this cherry bounce as a sipping liquor or in cocktails, I reduced the sugar. I also wanted to taste some of that summer flavor, so I left out the spices. Here's what I used: 1 colander sour cherries (a little more than 1 quart, pitted and stemmed - feel free to use more) a little more than 1 cup sugar 1 liter smooth brandy (not the expensive kind, but not the cheapest either) Place 1/2 cup sugar in each of two quart jars. Pit the cherries and divide equally between the jars (you'll get about a pint for each). The easiest way to do this, since sour cherries are so soft, is just to squeeze the pits out over the jars, to make sure you catch all the juice. Discard the pits. This is also easier if you use a canning funnel for each jar, which helps with the splatters. Because Montmorency cherries have yellow flesh, if you wear dark clothing, the spattering won't stain. Once the cherries are done, add 2 cups of brandy to each jar. You'll have a little left over, so just divide the remainder between the two jars. I added another couple of tablespoons of sugar to each, because I had room. Screw the mason jar lids on and shake every hour or so until the sugar is dissolved. Then let rest in a cool dark place, shaking occasionally, until February. I left the cherries in, and intend to either serve one with each glass, or strain them out and cook them in more sugar and serve over vanilla ice cream (Thomas Jefferson's favorite). Funnily enough, although the mixture was brown last night, by morning it was bright red and the cherries were already starting to lose their color. We'll see how it turns out. I might regret not adding more sugar or cherries, as sugar tends to mellow out alcohol, but then again, I might not! I'll give an update for President's Day 2020, when I'll invite some friends over for cherry bounce, walnuts, and ice cream!  Happy Presidents' Day, everyone! Originally celebrated on February 22nd, which is George Washington's birthday, President's Day was consolidated with Abe Lincoln's in 1971 and every year food blogs are inundated by everything cherry in George's honor (poor Abe gets little mention at all, and you can just forget about all the other Presidents). The story goes that little George "barked" a cherry tree as a child and couldn't "tell a lie" to his father, admitting the deed. Cherries have been a symbol of George ever since. But did the poor barked cherry tree actually exist? Most historians say no, given that the story first appeared in a later edition (but not the first) of a biography published some years after Washington's death. Although some historians argue that it is, in fact, likely to be true, given that none of George's (i.e. Martha's) children ever disputed it. But did George ACTUALLY like cherries? The story goes that cherry pie was his favorite, and thus cherry pies are served in his honor all over the country. But was it? A search of Washington's papers for "pie" brings up only a couple of mentions, all referring to "Christmas pie." Searching for "cherry" brings up hundreds of hits - all about Washington planting cherry trees of all difference varieties at Mount Vernon. So he certainly liked cherries. But cherry pie? Pie was a common way to turn fruit into dessert in the 18th century and was much easier to make in the days of open-hearth cooking than the more complicated cakes. Cakes were also much more expensive, being leavened with numerous, long-beaten eggs and calling for large amounts of butter, sugar, and spices. Pies, on the other hand, were made with lard and a little flour, with a cooked fruit filling, which may or may not have been sweetened. Pies could also be sweetened with the much cheaper honey, molasses, or maple syrup. They were also a lot faster to make and less likely to scorch in a dutch oven over coals or inside a beehive oven. So it is possible that Washington ate a fair number of cherry pies in his day. But the thing about cherries is that they aren't even remotely in season in February. Martha Washington did record a recipe for preserved cherries. And cherry bounce, a sort of homemade cherry brandy, was popular in the 18th century. But cherry pie for George's birthday? Not likely, unless it was made with those preserved cherries. If you ask the folks at Washington's Headquarters State Historic Site in Newburgh, NY (not too far from where I live), they'll tell you that Washington's favorite food was walnuts. Which crops up (no pun intended) in the tree planting sections of Washington's papers just as often, if not more so, as cherry trees. Another Washington legend says he could crack walnuts with his bare hands. Which with English walnuts (his favorite) is quite easy. Native American black walnuts, however (those most readily available to George), are a different story. Most people crack those by running their cars over them. With their British heritage, George and Martha may have made pickled walnuts, which are made in June when black walnuts are still green and the nut hulls haven't fully formed yet. The pickled green nuts (recipe here) are eaten whole (hull and all!) with cheese. In the 18th century cheese and nuts with fruit was a common "dessert course." They'd probably go great with some preserved cherries and cherry bounce. If you'd rather celebrate George with a dessert, try the slightly more accurate Martha Stewart's walnut pie (though what you'd substitute for corn syrup I'll never know). Or bake Martha Washington's "Great Cake," which would have been eaten at Christmastime (maybe a few slices were left by February?). But keep in mind that, according to Martha's grandson Custis, George may not have even liked dessert all that much. Custis wrote, "He ate heartily, but was not particular in his diet, with the exception of fish, of which he was excessively fond. He partook sparingly of dessert, drank a home-made beverage, and from four to five glasses of Madeira wine." Maybe fish in Madeira would be a better dish to celebrate Washington? Certainly cherry bounce counts as "a home-made beverage." Really, whole walnuts, cheese, and preserved cherries with a glass of cherry bounce or Madeira would be the most accurate "dessert" to reflect George's predilections. If you'd rather, go ahead and celebrate Abe Lincoln instead. Apples, corn cakes, bacon, and gingerbread men were among his favorites. If you'd like to know more about Abe and his penchant for helping Mary in the kitchen, check out Rae Katherine Eighmey's Abraham Lincoln in the Kitchen or listen to this interview from NPR. However you celebrate our past Presidents, just remember that when it comes to the past, culinary or otherwise, our American mythology isn't always accurate. Happy eating. Happy Presidents' Day. The Food Historian blog is supported by patrons on Patreon! Join us for awesome members-only content like free digitized cookbooks from my personal collection, e-newsletter, and even snail mail from time to time! |

AuthorSarah Wassberg Johnson has an MA in Public History from the University at Albany and studies early 20th century food history. Archives

July 2024

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed