|

As I delve deeper into research on the farm labor shortage for my book, I'm starting to realize that the main theme of the home front in the First World War is that there were a whole bunch of people doing largely the same thing at the same time, and it wasn't until really the end of 1917 into 1918 that government agencies figured things out enough to actually get everyone properly organized. This poster is just one example of that. "We Eat Because We Work," a poster featuring cherubic White children digging and watering what are presumably radishes (judging by the contents of the basket) on a sunny hillside overlooking a flag flying not the American flag, but one of the United States School Garden Army, reads a little more ominously in the context of say, Nazi Germany, or Orwell's 1984. But when the U.S. School Garden Army was founded, and likely when this poster was produced, terms like "dictator" and "propaganda" had far more innocent meanings. Still, this poster does seem to imply, consciously or not, that children who do NOT work, will NOT get to eat. I doubt it was meant that way. Instead, like many propaganda posters of the First World War, it was meant to inspire people to participate. This poster sent me down the rabbit hole a bit, in part because the online history of The United States School Garden Army was so vague, and I'm a stickler for exact dates. Rose Hayden-Smith has written about the United States School Garden Army, but even she isn't super clear on when exactly the "army" was founded. The Farm Cadet program, which literally "enlisted" high school-aged boys into farm work on military-style camps, was founded in New York State in April of 1917, just days after the United States entered the war. A May 5, 1917 article in the New York Times mentions the "National School Children's Garden League," but only to mention a fundraiser for the league. It's the only reference I've been able to find of that organization. By June, 1917, Port Jervis, NY is discussing school gardens in conjunction with the Farm Cadet program, but school gardens as pedagogy had been popular throughout the Progressive Era. It seems that despite claims online that the United States School Garden Army was founded in 1917, it wasn't until March of 1918 that the USSGA was official. The Newburgh, NY Daily News published "Millions of Children to Enlist in Nation's School Garden Army" on March 20, 1918. The article suggests that this is a brand new endeavor, mentioning several times that this "new army" and "plans" "will begin soon." The "draft" age for the United States School Garden Army was 9-16 years old, both boys and girls. The cut-off age of 16 was so that boys aged 16 and older could participate in the Farm Cadet program. This poster features children who look younger than nine years old, but perhaps young cherubs were more attractive models than gangly pre-teens. As Hayden-Smith argues, the United States School Garden Army was designed to turn children from consumers into producers, at least temporarily. Critiques of the use of child labor were assuaged by assurances that the work would be for no more than a few hours a day, and always supervised by teachers or other staff. The work of the USSGA continued for several years after the war, still going strong in 1919 and 1920, likely because the High Cost of Living was keeping food prices up, and school gardens raised produce to be consumed by students on site, thus lowering school cafeteria costs. In fact, most of the articles from late 1919 and early 1920 talk about the financial benefits of the school gardens, in addition to the social and emotional benefits. In today's context, the discussion of the financial benefits of child labor seems mercenary, at best, but the school garden movement did have social and emotional benefits as well - being out-of-doors, the "stick-with-it-ness" of tending living things, and the rewards of getting to eat the results of your hard work. School garden programs that help provide for school cafeterias have been revived in recent years as a way to engage students with "real" food and create affordable access to fresh, local fruits and vegetables, especially in areas of food deserts. But growing school gardens isn't cheap, nor is it easy. In much of the nation, the best garden growing months are when school is not in session. In World War I, teachers and students gave up part or all of their summers for the war effort. In today's world, the garden manager usually does the bulk of the work over the summer. Regardless, the work of school gardens during the First World War does seem to have been a relative success. As I research more, I'll delve deeper into school gardens, so stay tuned! The Food Historian blog is supported by patrons on Patreon! Patrons help keep blog posts like this one free and available to the public. Join us for awesome members-only content like free digitized cookbooks from my personal collection, e-newsletter, and even snail mail from time to time! Don't like Patreon? Leave a tip!

0 Comments

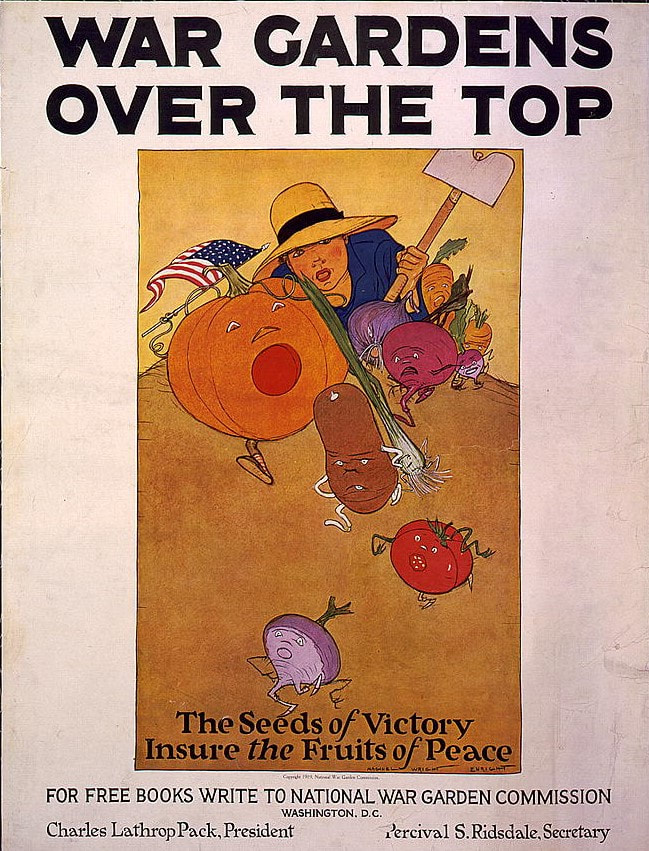

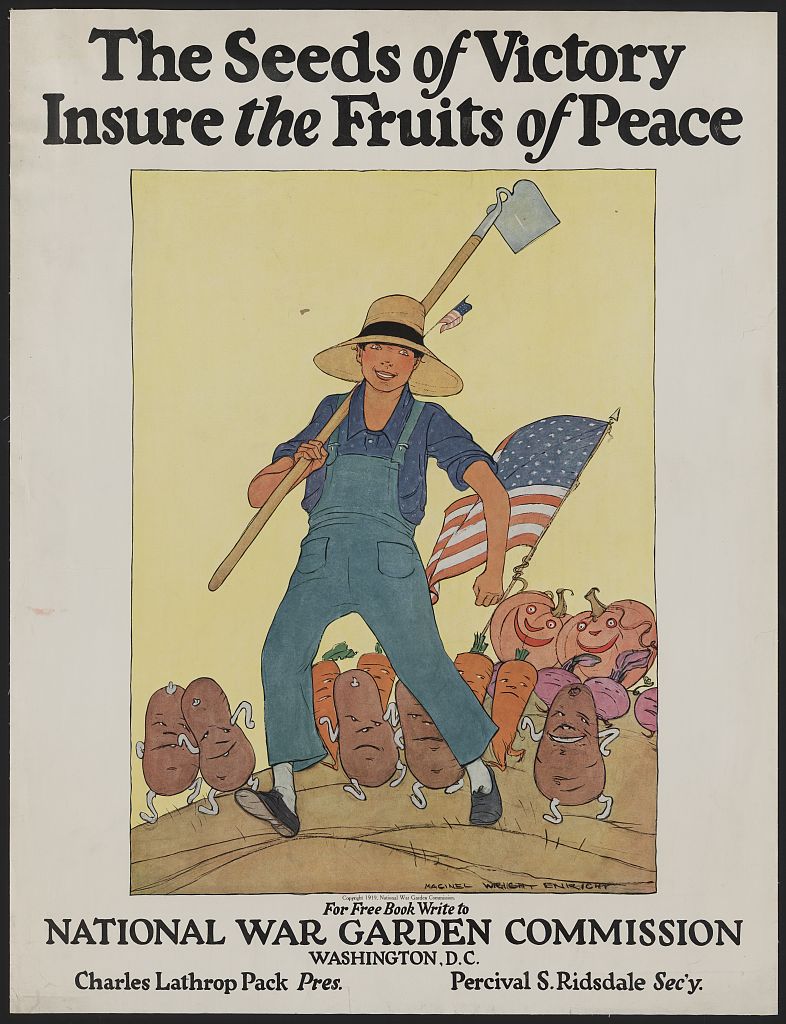

The National War Garden Commission, a private organization funded by timber magnate Charles Lathrop Pack, was one of the most prolific sources of wartime propaganda posters outside the federal government. One of the major proponents of civilian garden programs, even before the U.S. entered the First World War, the National War Garden Commission gave away free booklets on gardening, canning, and food preservation. The above poster features a boy with a spade and straw hat climbing over a mound of dirt. In the lead are series of anthropomorphic vegetables, including a pumpkin carrying the American flag, and all appear to be yelling or screaming as they run down the hill. Reading "War Gardens Over the Top," and "The Seeds of Victory Insure the Fruits of Peace," the poster brings to mind the "boys" going "over the top" of the trenches in battle. This use of military language in propaganda posters was not uncommon, but this particular phrase likely did not have the full impact in the period that it does now. Today, we realize how horrific the charges of men "over the top" and across no-man's land between the trenches on the front really were. But in the period, it's likely people had only sanitized newspaper articles and perhaps a propagandized newsreel or two to give them a frame of reference for the term. In this second poster, which also reads "The Seeds of Victory Insure the Fruits of Peace," our military allusions are a little more innocent. Here our same overall-ed and straw-hatted boy marches in a parade, hoe over his shoulder, accompanied by more anthropomorphized vegetables. These vegetables look less than thrilled to be marching, but the sentiment is the same. Both posters were published in 1919, technically AFTER the war was over. But as with most wars, the end of conflict does not mean that everything goes back to normal. There were numerous attempts by a number of organizations, including the federal government, to get Americans to continue to conform to wartime measures, including voluntary rationing and war gardens, which were termed victory gardens after the cessation of hostilities, well in to 1919 and even 1920. Here, the National War Garden Commission makes the argument that the "seeds of victory insure the fruits of peace," meaning that by continuing to plant vegetable gardens and free up domestic food supply for shipment overseas, Americans could help stabilize and rebuild Europe in the wake of the war. Illustrated by Maginel Wright Enright, primarily known as a children's book illustrator, the posters have a luminous clarity, even if Enright was not particularly good at giving vegetables convincing facial expressions. Lots of folks are starting year two of pandemic gardens - are you one of them? I am! Raised beds are going in this year and I already have my seeds and a plan. The Food Historian blog is supported by patrons on Patreon! Patrons help keep blog posts like this one free and available to the public. Join us for awesome members-only content like free digitized cookbooks from my personal collection, e-newsletter, and even snail mail from time to time!

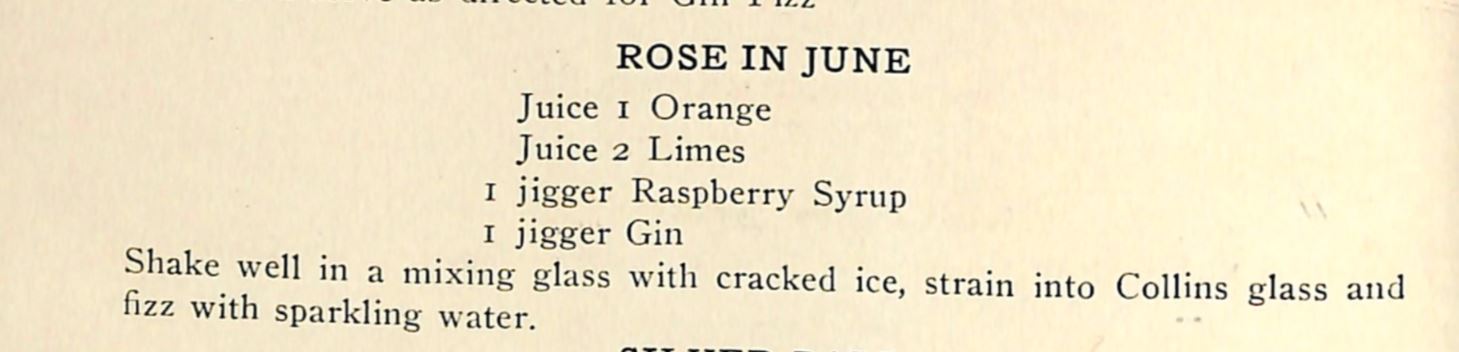

It's Juneteenth! Thanks to everyone who joined us for Food History Happy Hour. This week we make the Rose in June cocktail from the 1917 "Recipes for Mixed Drinks." We discussed Juneteenth, red velvet cake, victory gardens including propaganda and the exclusion of Black farmers and imprisoned Japanese Americans, the role of visuals in influencing taste, Black Food Historians You Should Know, disparities in book contracts, hot weather foods, salads, summer kitchens, how historical peoples coped without air conditioning, how historical peoples kept foods cold before refrigeration, ice and ice cream in the ancient world, rural electrification and electric refrigerators, the Frigidaire Cookbook, icebox pie, racial stereotypes in food advertising, including the history of the "Aunt" and "Uncle" terms, including Uncle Ben and Aunt Jemima, the history of the mammy trope, the tragedy of child caring roles, What Mrs. Fisher Knows About Old Southern Cooking, Black children in advertising, Franchise: the Golden Arches in Black America, the forthcoming book scanner I ordered, monuments and statues, and we ended with a signal boost for the James Hemings Society.

Rose in June Fizz (1917)

The "Rose in June" cocktail comes from the "Fizz" section of Recipes for Mixed Drinks by Hugo Ensslin (1917).

The original recipe calls for: Juice of 1 orange Juice of 2 limes 1 jigger raspberry syrup 1 jigger gin Shake well in a mixing glass (or cocktail shaker) with cracked ice, strain into Collins glass and fizz with sparkling water OR - if you don't have fresh citrus fruits OR raspberry syrup - you can substitute 1/3 cup orange juice, 1/4 cup lime juice, a heaping tablespoon of raspberry (or in my case, strawberry) jam, and the gin. Very nice, very refreshing, but sadly NOT pink.

Here's a roundup of links related to everything we talked about (in addition to all the links above!):

If you liked this post and would like to support more Food History Happy Hour livestreams, please consider becoming a member or joining us on Patreon. Members and patrons get special perks like access to members-only content.

Many thanks to the Southeastern New York Library Resources Council for hosting my talk and for recording it! Much (but certainly not all!) of the research I've done for my book is presented in condensed form here. I think it turned out very nicely indeed and I am now contemplating recording more of my talks for sharing online. What do you think? Should I?

Here is some further reading based on some of the topics I discussed in the talk:

Capozzola, Christopher. Uncle Sam Wants You: World War I and the Making of the Modern Eighmey, Rae Katherine. Food Will Win the War: Minnesota Crops, Cooks, and Conservation during World War I. St. Paul, MN: Minnesota Historical Society Press, 2010. Gowdy-Wygant, Cecilia. Cultivating Victory: The Women's Land Army and the Victory Garden Movement. Pittsburgh, PA: University of Pittsburgh Press, 2013. Hall, Tom G. “Wilson and the Food Crisis: Agricultural Price Control during World War I.” Agricultural History 47, no. 1 (1973): 25-46. Hayden-Smith, Rose. Sowing the Seeds of Victory: American Gardening Programs of World War I. Jefferson, NC: McFarlan and Company, Inc., 2014. Veit, Helen Zoe. Modern Food, Moral Food: Self-Control, Science, and the Rise of Modern American Eating in the Early Twentieth Century. Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina Press, 2013. Weiss, Elaine F. Fruits of Victory: The Woman’s Land Army of America in the Great War. Washington, D.C: Potomac Books, 2008.

If you or your organization would like to host a talk - virtual or otherwise - please make a request!

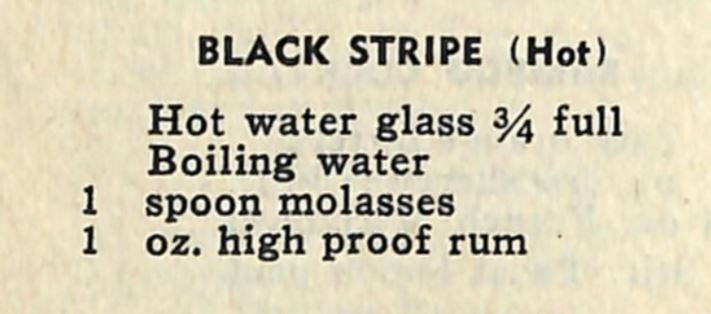

This post was supported in part by Food Historian members and patrons! If you liked this post, please consider becoming a member or joining us on Patreon. Members and patrons get special perks like access to members-only content. Thanks to everyone who joined me last night for Food History Happy Hour live on Facebook. This week we made the Black Stripe cocktail - really a hot toddy - from the Roving Bartender (1946). We discussed unusual historic and heirloom vegetables, terrapin and mock turtle soup, the Victorian obsession with game meats, veal, the origins of Caesar salad, springtime greens and foraging, vegetable species diversity and gardening, heirloom grains, the centralization of American food production, tanneries and slaughterhouses, Laura Ingalls Wilder, and updates on my book! Black Stripe Cocktail (1946)I have to admit, this was not my favorite cocktail, but I think it might be that I am simply not a fan of hot toddies. As friend and bartender Mardy and I agreed, "That's a toddy! Hot watery alcohol." Lol. Fill a hot water glass (or an Uffda mug) 3/4 full with boiling water Add 1 spoon of molasses 1 ounce high proof rum (OR 1 1/2 ounces apple pie moonshine) Stir and drink while hot. If you liked this post and would like to support more Food History Happy Hour livestreams, please consider becoming a member or joining us on Patreon. Members and patrons get special perks like access to members-only content.

Thanks to everyone who joined me last night for Food History Happy Hour live on Facebook. I had a blast and everyone asked such great questions!

In this week's episode, we covered a LOT of ground and discussed how applejack is made, shrub, eugenics, Americanization of immigrants, comparisons between modern issues with dairy farming, dumping milk, and plowing under fields of vegetables and what happened during WWI and the Great Depression, types of dairy cows and how dairy farming works (including a discussion of veal), Victory gardens, agricultural policy history, historic baking, and flips (including Tom & Jerry). WHEW! The hour flew by and I had so much fun. You can watch the whole thing below.

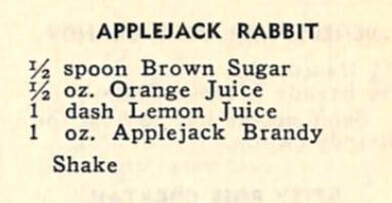

And of course, I made a vintage cocktail! This week's cocktail is the Applejack Rabbit and it comes from the 1946 cocktail book, The Roving Bartender by Bill Kelly.

We talked a little bit about cocktail glasses and serving sizes because of course this week I did NOT use a Collin's glass, but rather a small martini glass. In his introduction to The Rover Bartender, Kelly writes, "As the drinks are shorter now, the glasses for mixed drinks should be shorter and the drink recipes in this book are especially for cocktail glasses of not over 2 1/2 ozs. If a larger glass is used, the proportions will have to rise. You may serve a pony of cognac in a 20 oz. snifter glass, but if a cocktail glass is not near full it is unsatisfactory to the customer." I can certainly agree! But as someone who prefers a cocktail to be only a few ounces, I can't say I enjoy the generally much larger glasses of modern bars and restaurants. They may be easier to handle and clean, but they're too big! Applejack Rabbit Cocktail (1946)

The original recipe is as follows:

1/2 spoon brown sugar (I used about half a tablespoon) 1/2 oz. orange juice 1 dash lemon juice 1 oz. applejack brandy Pour over ice in a cocktail shaker and shake for longer than you think you should to make sure the brown sugar is dissolved. Strain into a small cocktail glass, such as martini glass or old-fashioned champagne glass. Sip cold. Virginia Apple Cake Recipe

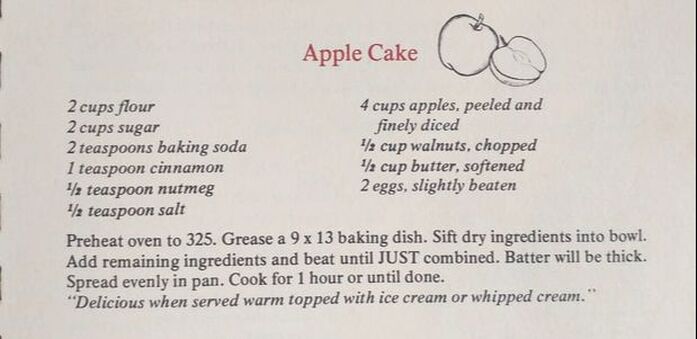

And, since we talked about historic baking, I thought I would share the recipe for apple cake I found recently in my copy of Virginia Hospitality (1976, my copy is the 1984 reprint). This particular Junior League cookbook is quite good with many of the recipes arranged by region and with decent head notes for many. Alas, this "Apple Cake" has neither headnotes nor region assigned. But it looked intriguingly easy and used up quite a bit of apples.

However, as I discussed in the episode, it really is a strange cake. As such, while I've included a photo of the original recipe, I've written my own version to help walk you through how the recipe should work.

2 cups flour

2 cups sugar 2 teaspoons baking soda 1 teaspoon cinnamon 1/2 teaspoon nutmeg 1/2 teaspoon salt (note - I would add 1 teaspoon next time, the cake tasted a bit "flat") 4 cups apples, peeled and finely diced (about 3 medium apples) 1/2 cup walnuts, chopped 1/2 cup (1 stick) butter, softened 2 eggs slightly beaten Preheat oven to 325 F. Grease a 9"x13" baking dish (I used metal). Whisk dry ingredients in a bowl, then add apples and walnuts and stir to coat. If butter is refrigerated, microwave in 10-15 second intervals until very soft but not totally melted. Add butter and eggs to the dry ingredients and mix/fold with a wooden spoon until no loose flour remains. It will seem like not enough moisture - just keep folding, it will come together. The batter will be very thick. Do not overbeat. Spread evenly in the pan. Bake for 1 hour or until done. (I baked mine for 1 hour and 5 minutes, as the middle still seemed a bit soft). In all, my husband LOVED this recipe, but it was not my favorite. Next time I would definitely add some extra salt as the cake tasted a bit "flat" without it. In retrospect, I also MIGHT have accidentally added 2 teaspoons of cinnamon instead of one? Oops. It was too much cinnamon for me, but as I said, my husband loved it as it reminded him of carrot cake. Baking it for an hour at 325 seemed like way too long, but it did result in nicely caramelized edges (all that sugar). However, all the apples melted into the cake! So next time I would probably cut them a bit bigger. I did almost mince them in some cases.

So what did you guys think of this week's episode? Are you going to join me next Friday on Facebook? I hope to see you there! Thanks again to everyone who watched live and remember, if you have any burning food history questions, you can send them to me in advance, message The Food Historian on Facebook, or ask live during the broadcast. See you soon!

If you liked this post and would like to support more Food History Happy Hour livestreams, please consider becoming a member or joining us on Patreon. Members and patrons get special perks like access to members-only content.

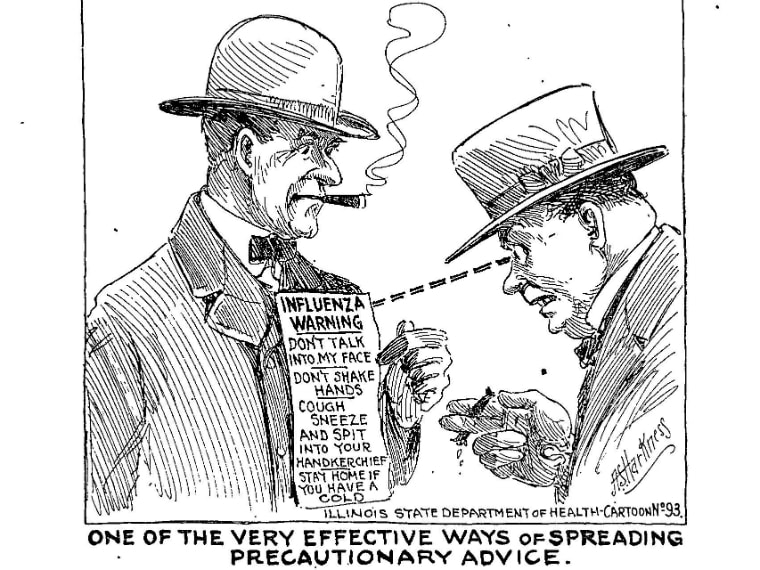

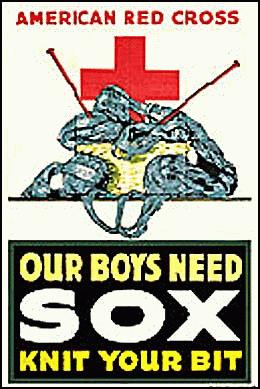

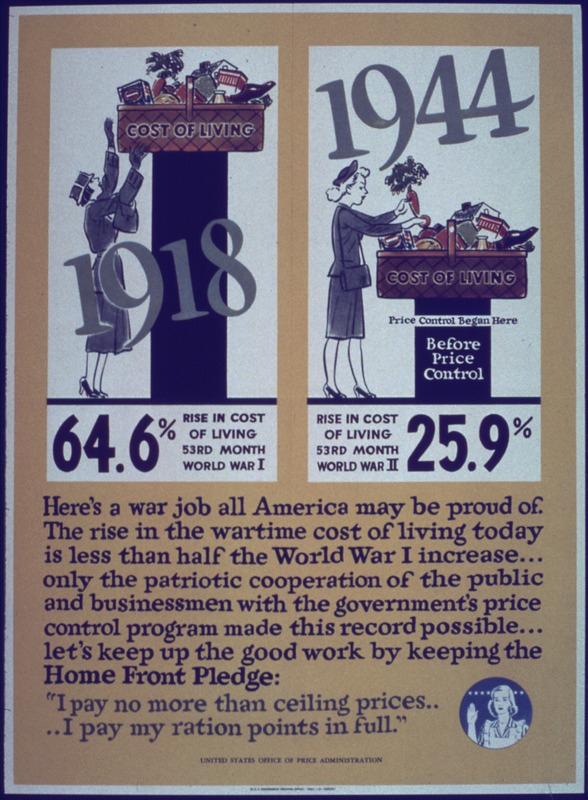

Y'know that old saw, "Those who ignore history are doomed to repeat it?" Well, like a lot of old adages, this one has a big grain of truth in it. Historians often can see parallels to the modern world as they study history. Indeed, my area of specialty - the Progressive Era and World War I home front - has led to LOTS of comparisons to modern life. But with the addition of the coronavirus lockdown, the comparisons grew more numerous. To that end, I thought I would catalog some of the striking similarities. Failure of Bureaucracy: Military SupplyOne thing that has becomes especially striking at this time is the failure of the federal government to manage national supplies during an emergency. In this instance, it's the management of medical supplies for COVID-19, particularly personal protective equipment (a.k.a. PPE). States are competing on an open market and with each other, driving up prices and leading to shortages. To make up the shortfall, ordinary citizens are creating homemade versions of masks, face shields, and other equipment. During the first months of the U.S. entrance into World War I, the exact same thing was happening. Historian Robert Ziegler in his book America's Great War: World War I and the American Experience, outlines the deplorable state of military supply following the Spanish American War. Individual battalions were competing with each other on the open market to purchase supplies, thus driving prices up. In addition, the United States had never fielded such an enormous army and the production of other military supplies, such as uniforms and rifles had yet to keep up with the demand of a suddenly-enormous army. According to historian David M. Kennedy, in his book Over Here: The First World War and American Society, soldiers were sent to Europe with hardly any training. Men and boys who had been recruited in July, 1918 were on the front lines by September. Some men arrived never having used a rifle, and had to take an intensive 10 day course before being sent into battle. The logistics of shipping war materiel, both within the borders of the United States and overseas was also a mess, causing railroad and port backups. Some credit the poor supply of soldiers in training camps (inadequate clothing, bedding, housing) with exacerbating the effects of the Spanish Flu pandemic. Combined with this was the efforts of the American Red Cross. Famed for providing bandages and nursing aid during the American Civil War, thousands of chapters sprang up across the nation and throughout 1917, women were encouraged to "knit their bit" by knitting sweaters, socks, wristers, and watch caps for "our boys" being sent overseas. Why? Likely because military supply chains were, as stated, in shambles and because it was easier (and cheaper) to task the nation's women with keeping soldiers warm than to mobilize factories. Wool socks in particular were in high demand because of the poor conditions in the trenches. But by 1918, according to historian Christopher Cappazola in his book, Uncle Sam Wants You: World War I and the Making of the Modern American Citizen, the federal government was frantically telling women to STOP knitting, likely because military supply was completely reorganized. Although there are plenty of resources about knitting in WWI and the American Red Cross (including this lovely one), few people seem to have made the connection between "knitting your bit" and the failure of military supply. It was only part-way through American participation in the war that the federal government reorganized military supply under a centralized Quartermaster General. It wasn't until the Korean War that the United States passed the Defense Production Act (1950), which empowered the federal government to compel private business to prioritize the production of war materiel and prevent hoarding and price gouging. If the United States were to learn the lesson of WWI supply today - the federal government would coordinate with individual states to purchase - and allocate - medical supplies where most needed, instead of bidding against states on the open market. Xenophobia, Immigration, RaceIn the years leading up to the First World War, the United States was inundated with immigrants from all over the world, but particularly Eastern and Southern Europe. The United States was also recovering from the abandonment of Reconstruction and Black Americans were becoming more and more prosperous, with a growing middle class. Combined with a brain and labor drain on rural areas, this led to people like President Theodore Roosevelt warning of "race suicide" for White Anglo Americans unable to keep pace with the more fertile immigrants. Roosevelt also worried about rural life and started the Country Life Commission to study and combat the drain of population from rural America to urban areas. Tempted by "cosmopolitan" life, reformers worried, young people would be corrupted and the bedrock foundation of democracy - the landowning yeoman farmer - would diminish. Unfortunately for reformers, the majority of people in rural areas lived difficult lives and particularly in the South, most did not own the land they farmed. But the idea that rural America, and farmers in particular, are the "salt of the earth" is an idea that has persisted even today. With "flyover country" being courted by politicians, especially conservative ones, with every election. Immigration and race remain hallmark dogwhistles in modern politics. The Trump campaign used the slogan "America First" on the campaign trail - echoing the campaign slogan of Woodrow Wilson leading up to his first term as a neutral isolationist. It was a policy he would abandon in his second term, as the U.S. entered World War I in the spring of 1917. Americans were notoriously isolationist in the early 20th century (except for their colonialist ambitions in Central America, Hawaii, and the Phillipines) and America's first propaganda machine had to be created to convince them that joining the war was a good idea. To convince them, Woodrow Wilson invented the idea of defending and spreading democracy (and American exceptionalism) abroad - a policy that has continued to be used in every American war since then. Attempts to Americanize immigrants remained in effect throughout the war. Progressive reformers from settlement houses and canning kitchens on up to proponents for the war which thought a draft would help Americanize immigrants tried to force people into the mold of White Anglo American (usually Northeastern) culture. Black Americans faced similar pressures, and segregated versions of just about every middle-class voluntary organization - including the Red Cross - was implemented during the war. Following the war, newly economically mobile Black Americans, buoyed by industrial jobs for war production, faced even more hostility than before. Resentment by racists clashed with confident (and armed) veterans returning from war. The Tulsa Race Massacre of 1921 is just one example of Black WWI veterans attempting to defend themselves and their communities. Race riots, lynchings, and a dramatic expansion of the Ku Klux Klan were the hallmarks of 1919, 1920, and beyond. Today, Black American communities still deal with over-policing, incarceration, and violence. Latinx-Americans have dealt with a dramatic ramp-up of incarceration, family separation, and deportation (even of children), as well as more casual racism. And Asian-Americans in particular have borne the brunt of some horrific incidents of racism directly related to the coronavirus - as the ignorant believe that they (regardless of whether or not they had been to China recently, or were even of Chinese descent) were "carriers" of the disease - another old saw of racism most famously used by Nazis against the Jews (among others). The High Cost of LivingIn the two decades leading up to WWI, the United States underwent a series of depressions and recessions. Starting with the Depression of 1893 (which the US did not recover from until 1897-98), and with smaller recessions in 1907 and 1913-14, the "high cost of living" (commonly abbreviated as "HCL" or "H.C.L.") saw a dramatic rise in cost of living, including food and housing, while wages stagnated. Called "stagflation" by economists, this situation led to labor unrest, and strikes, food boycotts, and food riots were all common during this time period. Socialists were also in political ascendancy due to income and labor inequalities. Labor strikes were often broken by deadly force. Food boycotts and riots remained the purview of the desperate - often women with starving children which tugged at the heartstrings of wealthy and middle-class White Progressives, even as some were organized by socialist activists (read about the 1917 food riots in New York City). Many of the strikes and riots of the 1900s and 1910s led to serious labor reform, including the ending of child labor, worker safety reforms, reduced hours, and more. New York City during WWI tried to pass a minimum wage law, but it was vetoed by the Mayor. Today's parallels include a different sort of high cost of living - most "luxury" items are cheaper than they've ever been, but housing, education, healthcare, and food costs have risen by as much as 200% in the last 20 years. In addition, democratic socialists and real, "bread and roses" socialists have seen their numbers spike in the last few years. Activists are fighting for a minimum wage increase, universal healthcare, and other reforms, although union membership has taken a steep dive in the last few decades. Coronavirus has only highlighted the "essential" role many low-wage workers play in American life, and some retail workers, cleaners/janitors, and restaurant workers are now being hailed as heroes alongside medical professionals and scientists. War Gardens & RationingOne particularly fascinating trend that appears to be occurring right now is the skyrocketing sale of vegetable seeds and plants. Tied in part to the fact that so many Americans are sheltering in place and have time to garden, the resurgent interest in "Victory Gardens" is also a reaction to temporary shortages in grocery stores (due to logistics, rather than supply) and fears that the food supply might be endangered by coronavirus. The First World War was also one of the first times in American history that a concerted effort to get ordinary people to plant kitchen gardens. Of course, part of that was because of the changing demographics of population. People in rural areas had almost always had kitchen gardens. But as more and more people moved into urban and suburban environments, and fresh food supplies became easier and cheaper to acquire, kitchen gardens became less necessary, and most people who could afford to focused on flower gardens instead. But the U.S. entrance into the war, with its commitment to feeding the Allies, came with very real fears that food would be in short supply. This was reinforced by rhetoric from Wilson and Herbert Hoover, the new U.S. Food Administrator, who knew that in the spring of 1917, existing crops would be inadequate to feed both Americans, their growing army, and the Allies without serious changes. Enter war gardens and voluntary rationing. Hoover was the brains behind the idea of voluntary rationing - he wanted Americans to show the world their personal fortitude and strength through voluntary efforts, including rationing. He also believed that the bureaucracy necessary to enforce mandatory rationing would not only be hugely expensive, it would also be ineffective. To lead by example, Hoover and the entire Food Administration were all volunteers. Rationing included refraining from eating wheat, meat, butter, and sugar whenever possible, and by the fall of 1917, "wheatless, meatless, and sweetless" days were implemented. Grain and flour substitutions, sugar substitutions, and vegetarian meals became more normalized during the war. The National War Garden Commission was also a voluntary organization, albeit a private, not public, one. Started by forestry magnate Charles Lathrop Pack, it encouraged Americans, especially school children, to plant "war gardens" (later renamed "victory gardens," a name that would resurface during WWII) which would provide fresh vegetables for ordinary people. Not only would this free up conventional food supplies, the production of local food would also free up transportation resources, which by the end of 1917 were becoming so congested that the United States temporarily nationalized its railroads. Spanish Influenza "One of the very effective ways of spreading precautionary advice." The man in the illustration wears a sign on his chest reading, "Influenza Warning: Don't talk into my face; don't shake hands; cough, sneeze, and spit into your handkerchief; stay home if you have a cold." Illustration from the Illinois Health News, 1918. "One of the very effective ways of spreading precautionary advice." The man in the illustration wears a sign on his chest reading, "Influenza Warning: Don't talk into my face; don't shake hands; cough, sneeze, and spit into your handkerchief; stay home if you have a cold." Illustration from the Illinois Health News, 1918. And, of course, the obvious one. I've already written a bit about the Spanish Flu, but it bears noting that during the course of the 1918 pandemic, the government was reluctant to report real numbers or spread information about the severity of the pandemic because they were worried that it would endanger the war effort or reduce morale. Some cities, like Philadelphia, held enormous and patriotic Liberty Loan parades, allowing the virus to spread like wildfire. In fact, despite evidence that the influenza strain likely started in the United States, it wasn't until neutral Spain was infected, and its newspapers reported the real death toll, that the general public learned of the pandemic. Hence the name, "Spanish Influenza." Similar things are happening now, with the Trump Administration's initial reluctance to admit coronavirus was a serious problem because they feared the effect on the economy. Conflicting information in the media (and from the President) about the severity of the virus and the need for social distancing and stay at home orders have exacerbated the problem here in the U.S. More recently, a dearth of testing has led to some experts to conclude that the death toll is severely underreported. We are now also learning that China has likely suppressed or underreported the true infection rate and death toll from coronavirus. Thankfully, unlike 1918, when newspapers largely cooperated with government propaganda efforts (under threat of having their licenses revoked, effectively putting them out of business), modern information is more accessible and immediate than ever through the internet. Although sifting fact from fiction is a bit more difficult these days. ConclusionThere are a number of other Progressive Era similarities to modern life - women's rights, environmental conservation, voting rights, and income inequality, to name a few - that I chose not to include in this list largely because they were less immediately relevant to the coronavirus pandemic. To learn more about food in World War I, check out my Bibliography page, which was links to lots of great books. I hope you enjoyed this read. It certainly helped me organize my thoughts around these similarities and I hope that we can learn from the successes and failures of the past. That's all any historian can hope. Thanks for reading. Stay safe, stay home. If you liked this post, please consider becoming a member or joining us on Patreon. Members and patrons get special perks like access to members-only content.

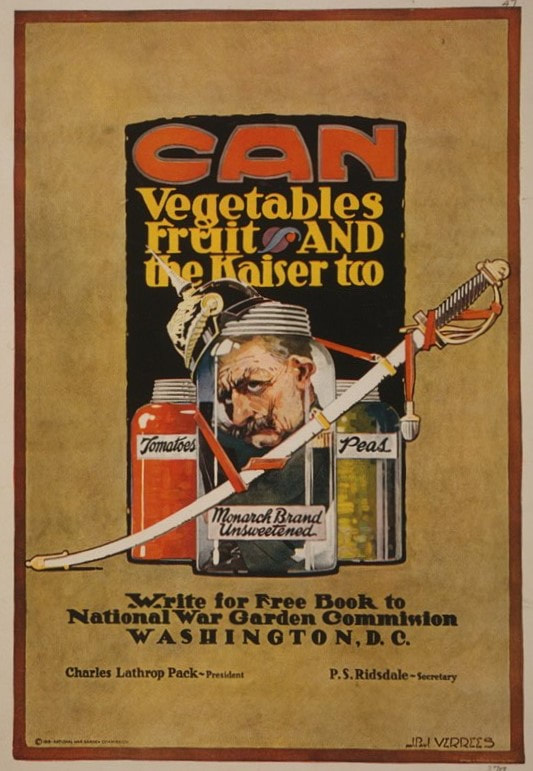

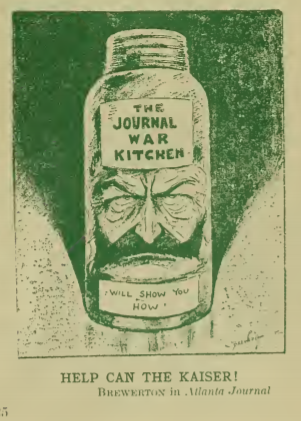

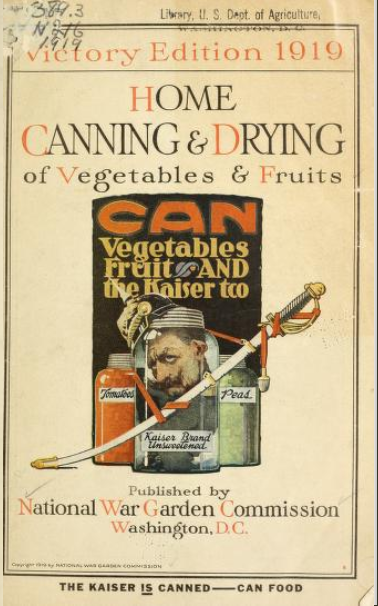

"Can Vegetables, Fruit, and the Kaiser, Too. Write for Free Book to National War Garden Commission, Washington, D.C." September is still preserving time, so I thought the next few World War Wednesdays would be about canning. This is another of my favorite World War I propaganda posters. Developed by the National War Garden Commission, the poster shows glass jars with zinc tops. Tomatoes at left, peas at right, and front and center, the profile of Kaiser Wilhelm II, German Emperor and King of Prussia. His spiky German helmet and saber hang on the jar, which is labeled "Monarch Brand, Unsweetened." Eminently clever, the poster implies that home preserving has the power to defeat the might of the German Empire and the Kaiser himself. The First World War was one of the first times that ordinary Americans were called upon to preserve food in their homes. Many Americans, especially those in rural areas, were already canning and preserving the bounties of their home gardens. But as commercial canning became increasingly widespread, inexpensive, and safer, people with easy access to food retailers found it much easier to simply purchase canned goods, instead of going through the bother of putting up their own. Many people were still using the tried-and-true, but not necessarily safe, methods of their forebears. And while water bath canning was increasingly outpacing the traditional food preservation methods of fermentation, drying, and sealing jam with paraffin wax, water bath canning low acid vegetables still was not 100% safe. But as the government encouraged food conservation and food preservation, the National War Garden Commission stepped up to the plate. Founded (and funded) by timber magnate Charles Lathrop Pack, the National War Garden Commission published a series of food preservation pamphlets that were used all over the country by home economists and women's groups to encourage home canning. The National War Garden Commission was also behind the school garden movement, but that's another post. The Commission would go on to produce a number of pamphlets on war gardening (renamed "Victory Gardening" post-war, a term that would be revived during the Second World War), including one pamphlet entitled "The War Garden Guyed," published in 1918. A clever play on words ("to guy" someone was to make fun of them, or ridicule), the "Guyed" contained cartoons, poems, and slogans both promoting and making fun of the gardening and food conservation movements. Submitted by newspaper editors, soldiers in the trenches, magazines, and ordinary people, the collection is quite a fun read, and not the only version the National War Garden created. "Raking the Gardener and Canning the Canner" predated "The War Garden Guyed" by one year - published in 1917, a quick turnaround indeed and indicates how quickly ordinary people adjusted to the idea of home gardening and canning. You can view almost all of the National War Garden Commission pamphlets on archive.org. In 1919, the National War Garden Commission used the "Can the Kaiser" poster image again, this time on their revamped "Home Canning & Drying of Vegetables and Fruits," rebranded "Victory Edition" post-war. At the bottom of the cover, it reads, "The Kaiser IS Canned." Although the fervor for home canning, thrift, and self-sufficiency continued into 1919 and 1920, by the time economic prosperity had returned full-force to give us the Roaring Twenties, most ordinary people who took up canning for the war effort abandoned it in victory. But I like to think that many of the food preservation lessons learned during the First World War would be revived and put to good use by the time the Second World War rolled around. If you enjoyed this installment of #WorldWarWednesdays, consider becoming a Food Historian patron on Patreon! Members get access to patrons-only content, to vote for new blog post and podcast topics, get access to my food library, research advice, and more!  Sowing the Seeds of Victory: American Gardening Programs of World War I by Rose Hayden-Smith is one of the few books on the topic of wartime gardening that scarcely mentions World War Two. The focus on gardening and horticultural movements prior to and during the First World War is a welcome addition to the small but growing pantheon of food history books from that era. Hayden-Smith, although a historian, is also a sustainable gardening advocate and it shows in this book - a little too much for my taste. Hayden-Smith uses the history of World War I war gardens as justification and inspiration for modern gardening movements, using period primary source material as evidence. If you are new to the ideas surrounding the modern sustainable agriculture and community gardening movement, you might find this interesting, but as someone who has followed said movement since high school, I found the constant references and asides to the modern era annoying and unnecessary. I would have vastly preferred if Hayden-Smith had made her connections between past and present at the end of each chapter, rather than interrupting the flow of the historical with the modern. Modern gardening aside, Hayden-Smith covers the World War I gardening movement by taking in-depth looks at Charles Lathrop Pack and the National War Garden Commission, the United States School Garden Army, the Pennsylvania School of Horticulture for Women, and the Woman's Land Army of America. Although the Woman's Land Army of America has been admirably covered in-depth by Elaine Weiss's Fruits of Victory, the other three topics have been little-studied and Hayden-Smith has done an admirable job of digging through obscure archives and has brought to light new resources from California (where she lives). Another chapter outlines the propaganda work of the war garden and food conservation movements and a final chapter takes a quick look at gardening in the Interwar to Post-War years in the United States. The book concludes with a summation of the war garden movement throughout the decades following and a call to action and advocacy for modern community gardening efforts. The best chapter is on the Pennsylvania School of Horticulture for Women - it is well-researched, interesting, and provides new insights into the origins of both the Woman's Land Army of America and Cornell University's cooperative extension home economics program, headed by Martha Van Renssalaer - a graduate of the horticulture school. Although the information is fascinating in the other chapters, they are somewhat poorly organized. For instance, in the chapter on the National War Garden Commission, Hayden-Smith references Charles Lathrop Pack numerous times, but doesn't introduce his background or any biographical information until halfway through the chapter (the chapter begins on page 32; Pack is finally "introduced" on page 48). In addition, perhaps at the behest of the publisher, there are constant parenthetical asides that in other books would have been asterisked footnotes, or simply incorporated into the text. Parenthetical asides pointing out obvious connections between the source material and modern food and gardening movements were especially annoying. It was a frustrating read - I could see and feel the potential for a truly excellent book, but was stymied every time a statement was followed by another saying the exact same thing, information was unnecessarily put in a parenthetical aside, or information was written in an order that made little sense. Frankly, the book was in serious need of a good editor (not a copy editor, although I did also find a few typos) - someone to give advice on how to organize the arguments and the best order for the book. Because although each topic/chapter was interesting in and of itself, there was also little to tie all four topics to each other. I would be interested to know if the book had been peer-reviewed before publication. In all, I would recommend it to anyone interested in the food and/or gardening history of World War I, but don't expect an easy read. If you would like to purchase Sowing the Seeds of Victory through this link, I will receive a small commission. |

AuthorSarah Wassberg Johnson has an MA in Public History from the University at Albany and studies early 20th century food history. Archives

July 2024

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed