|

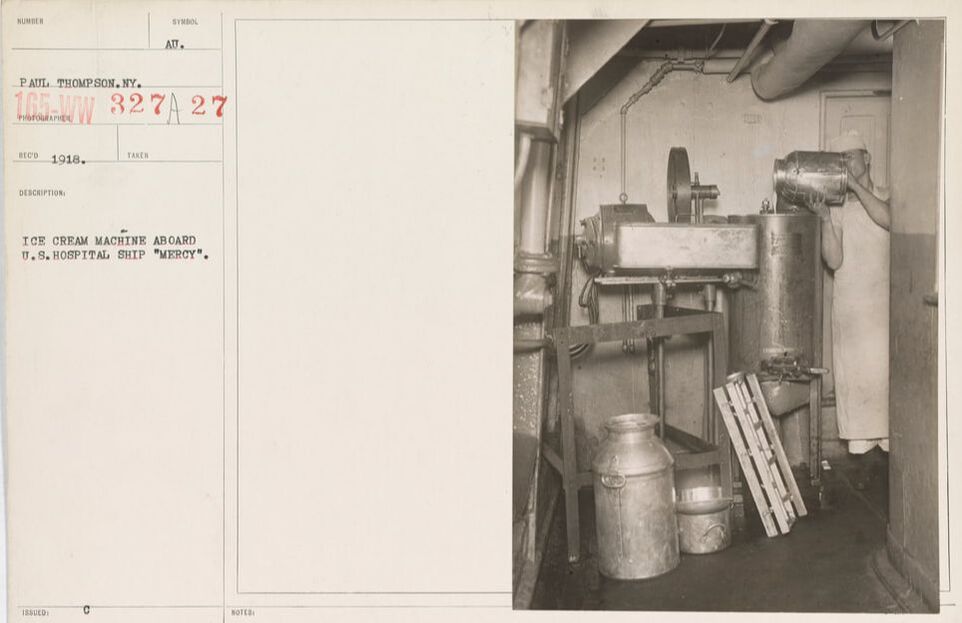

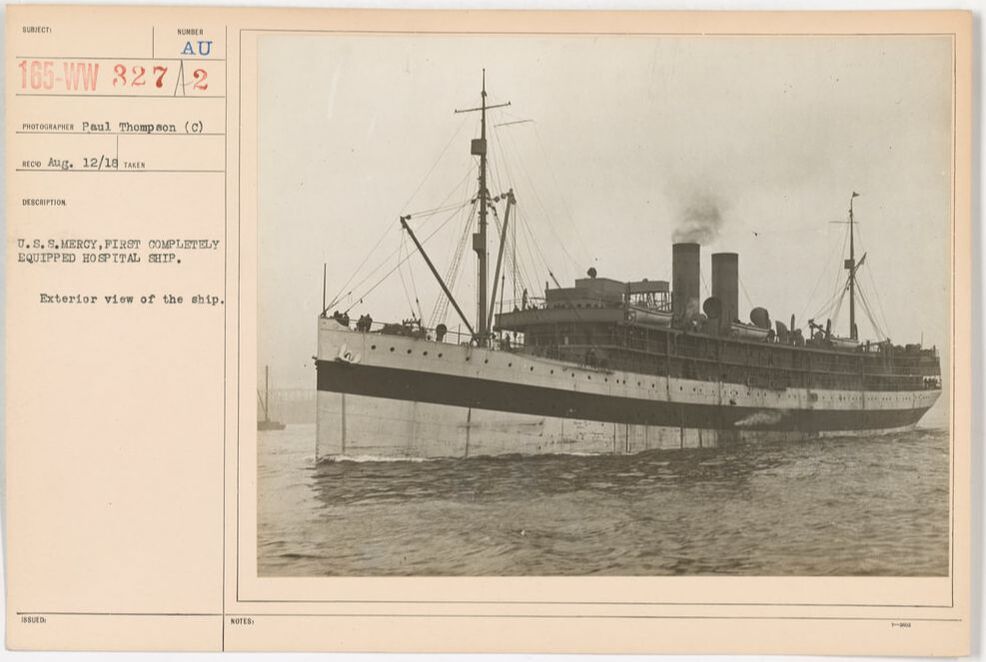

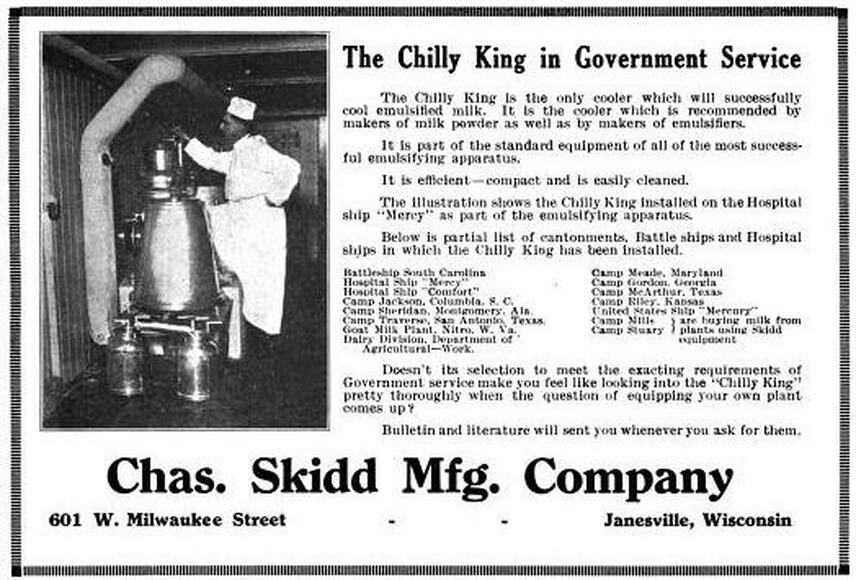

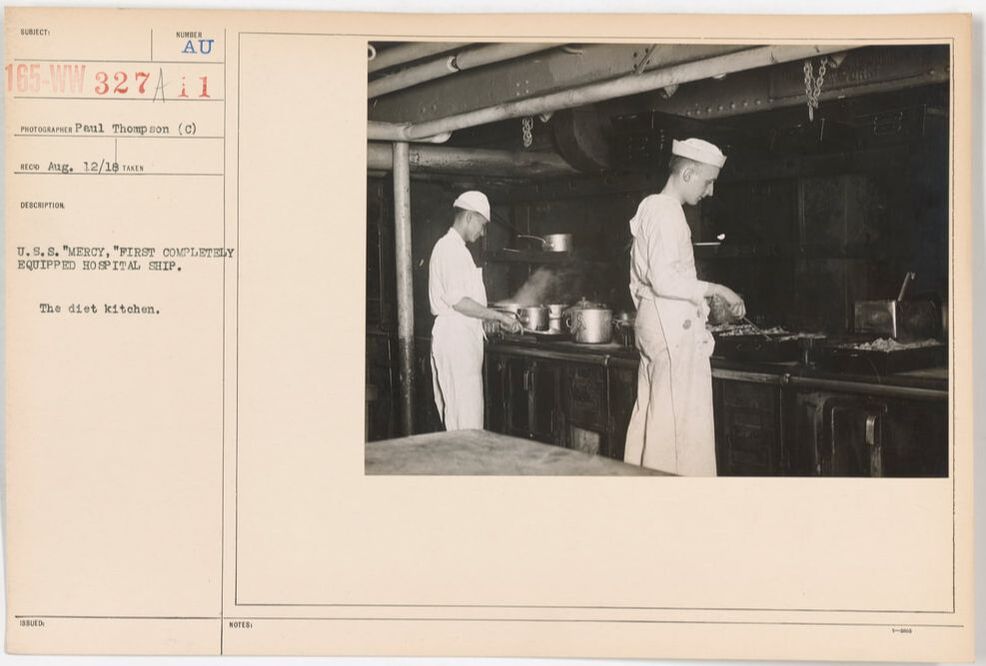

I've been getting a lot of calls for information about ice cream lately, and that has sent me down a rabbit hole. I did a whole talk on the history of ice cream last year (you can watch the filmed version here), but while I knew ice cream was a big tradition in naval history, I didn't know the connection to the First World War. I don't usually cover the history of military consumption of food during the World Wars, but this topic was just too much fun to resist. Ice cream wasn't always the Navy's treat of choice. For over a hundred years rum was the preferred ration by many sailors. But in the late 19th century the Temperance movement began to have increasing power over society. By 1919 we had a Constitutional Amendment (the 19th - often known just as "Prohibition"). But the armed forces went dry much earlier. In particular, on July 1, 1914, the U.S. Navy went alcohol-free. At the same time, naval vessels were being stocked with ice cream. In the May, 1913 issue of The Ice Cream Trade Journal, an article entitled "Sailors Like Ice Cream" explained that the Navy had recently ordered 350,000 pounds of evaporated milk - ostensibly for all sorts of cooking and baking, but ice cream was high on the list. You may wonder why hospital ships in the First World War were manufacturing ice cream on board? Well, it involves multiple factors. First is that ice cream was a product of milk; during the Progressive Era, milk was considered the "perfect food" as it contained fats, proteins, and carbohydrates all in one (supposedly) easily digestible package. Although many people are lactose intolerant, the White Anglo-Saxon dominance of American culture at the time prized milk. Ice cream rode into nutritional value on the coattails of milk. During this time period, dairy-based products like puddings, custards, milk and cream on cooked cereals or with toast, and ice cream were all considered nutritious foods for people who had been injured or ill. Along with foods like beef tea, eggs, and stewed fruits, these made up the bulk of recommended hospital foods from the late 19th century to World War I. Ice cream shows up quite frequently in early reports of the Surgeon General to the U.S. Navy. In his 1918 report to the Secretary of the Navy, ice cream appears to cause more problems than it solves. Notably, the use of ice cream produced commercially results in several instances of crew sickness, including simple illnesses like strep throat, alongside more serious ones like a diphtheria outbreak in Newport in 1917, which was traced to ice cream produced off-station. Fears of the spread of typhoid from places like restaurants, soda fountains, and ice cream shops led to "antityphoid inoculations" at naval shipyards. In Chicago, "All soft-drink and ice-cream stands have promised to give sailors individual service in the form of paper cups and dishes. To make this more effective, it is believed that an order should be issued prohibiting men from accepting any other kind of service." The Surgeon General also recommended inspection of offsite dairies and bottling works for milk, ice cream, and soft drinks to ensure proper sterilization of equipment and pasteurization of dairy products, as well as inoculation of employees against typhoid and smallpox. But ice cream was also noted as essential not only on the existing hospital ship USS Solace, but also on two new hospital ships fitted out since the declaration of war in 1917 - the USS Mercy and the USS Comfort. These ships included a cold storage plant and a refrigerating machine that could "produce, under favorable circumstances, a ton of ice or more a day." The ships also had distilling plants, able to convert seawater to fresh water, up to 20,000 gallons per day. In addition to describing the medical wards, crew facilities, laundry, and kitchen, the report noted: The most valuable adjunct in the treatment and feeding of the sick is the milk emulsifier, popularly known as the "mechanical cow." The milk produced from this machine is made from a combination of unsalted butter and skimmed milk powder and can be made with any proportion of butter fat and proteins desired. This machine will produce 15 gallons of cold, pasteurized milk in 45 minutes. The electric ice cream machine, controlled by one man, makes 10 gallons at a time and is supplemented by small freezers for preparing individual diets for the sick. According to the October, 1918 issue of The Milk Dealer, the "mechanical cow" had been displayed as part of the exhibits at the National Dairy Show in Columbus, Ohio in the fall of 1917. They noted: The "Mechanical Cow" Becoming Famous. Few people who saw the combination exhibit of Merrell-Soule Co. and the DeLaval Separator Co., last October, in Columbus, would have believed that within a year from that beginning the use of the Emulsor in combining Skimmed Milk Powder, unsalted butter and water would be taken up by Army, Navy, City Administrations, etc. throughout the United States. Such is the fact, however. The Mechanical Cow is now producing milk and cream on the U.S.S. Comfort and U.S.S. Mercy, the two splendid hospital ships of the Navy. An installation on board the U.S.S. South Carolina is kept working continuously to supply the demands of her crew. Mechanical Cows are filling the needs of milk at the base hospitals and several camps and one large machine is being operated by one of the city departments of New York. Health officers, physicians, milk experts and authorities on infant feeding all unanimously agree that milk and cream made by means of the "Mechanical Cow" is superior in every way to the average milk supply. This advertisement for "The Chilly King," a cooling machine that was part of the "Mechanical Cow" system on ships like the U.S.S. Mercy (a photograph of the machinery on board featured in the ad) also names a number of naval ships and military camps which use it, including:

By enabling ships and camps to use shelf-stable skimmed milk powder and unsalted butter, which keeps a very long time in cold storage, "mechanical cows" allowed for an ample supply of milk made in sanitary conditions. For naval ships, this was especially important when crews were away from shore for long periods of time. Ice cream also helped patients recover from illness (or so medical professionals at the time believed) but it also helped a great deal with morale. The professionalization of ship operations via the installation of state-of-the-art equipment was a hallmark of the First World War, but the U.S.'s late involvement in the war hamstrung most shipbuilding operations. Indeed, the construction of a new hospital ship in 1916 was actually shelved in favor of retrofitting existing ships like those that were transformed into the U.S.S. Comfort and U.S.S. Mercy, which had initially served as the sister passenger steamboats S.S. Havana and S.S. Saratoga, respectively. Part of the Ward Line, these very fast steamships ran the New York City to Havana, Cuba route but were requisitioned in 1917 first as troop transports, and later as hospital ships. The U.S.S. Mercy spent time as a home for the homeless during the Great Depression before she was scrapped in the 1930s, and the U.S.S. Comfort went back to civilian passenger transport for the Ward line under her old name, the S.S. Havana, before being pressed into service again in World War II, this time as a troop transport once again. The names USS Comfort and USS Mercy would be revived in World War II and a third pair of hospital ships bearing those names are still in operation today. Although ice cream is no longer considered central to the recuperation of the sick and wounded, it is still served on American naval vessels around the world. Ice cream would play an even more important role in the Navy during the Second World War. But that's a tale for another World War Wednesday! The Food Historian blog is supported by patrons on Patreon! Patrons help keep blog posts like this one free and available to the public. Join us for awesome members-only content like free digitized cookbooks from my personal collection, e-newsletter, and even snail mail from time to time! Don't like Patreon? Leave a tip!

0 Comments

|

AuthorSarah Wassberg Johnson has an MA in Public History from the University at Albany and studies early 20th century food history. Archives

July 2024

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed