|

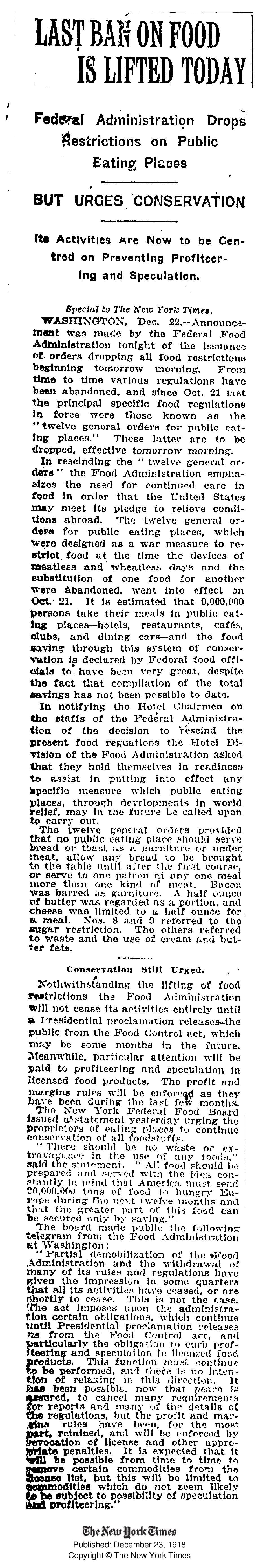

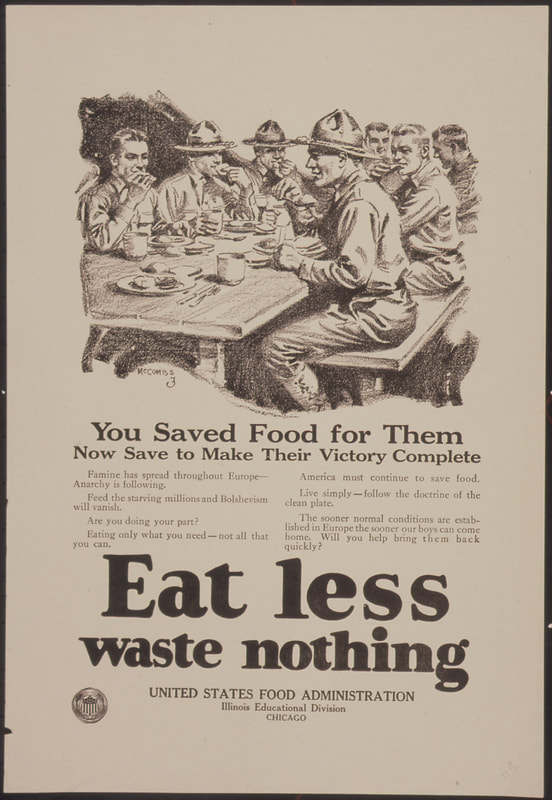

Most people know that the First World War official ended on Armistice Day - November 11, 1918 (the eleventh hour, of the eleventh day, of the eleventh month, to be exact). The war that was supposed to be over by Christmas had finally ceased, just four years after it began. But although the guns had stopped firing, the Treaty of Versailles was not signed until June 29, 1919. Armistice came on the heels of winter, after several devastating years of war in Europe. Agricultural fields were destroyed and so many men had been killed it was uncertain if labor would be available to cultivate fields again in the spring. Herbert Hoover and the United States Food Administration, along with President Woodrow Wilson, knew that the food supply for both American troops staying on in Europe for the next few months, the Allies, and even the defeated Germans would continue to need food aid. Hoover was left with the difficult task of convincing Americans that not only did they have to keep saving food, despite the official end of hostilities, they would also have to feed their former Hun enemies. But the American harvest, geared up for another potential year of war, had been a good one. And the USFA began to lift restrictions on commercial food production, retailing, and food service industries. By December 22, 1918, the last of these restrictions had been lifted, just in time for Christmas. The New York Times article above, published December 23, 1918, reads: "LAST BAN ON FOOD IS LIFTED TODAY Federal Administration Drops Restrictions on Public Eating Places BUT URGES CONSERVATION Its Activities Are Now to be Centered on Preventing Profiteering and Speculation. Special to the New York Times. WASHINGTON, Dec. 22. - Announcement was made by the Federal Food Administration tonight of the issuance of orders dropping all food restrictions beginning tomorrow morning. From time to time various regulations have been abandoned, and since Oct. 21 last the principal specific food regulations in force were those known as the "twelve general orders for public eating places." These latter are to be dropped, effective tomorrow morning. In rescinding the "twelve general orders" the Food Administration emphasizes the need for continued care in food in order that the United States may meet its pledge to relieve conditions abroad. The twelve general orders for public eating places, which were designed as a war measure to restrict food at the time the devices of meatless and wheatless days and the substitution of one food for another were abandoned, went into effect on Oct. 21. It is estimated that 9,000,000 persons take their meals in public eating places - hotels, restaurants, cafes, clubs, and dining cars - and the food saving through this system of conservation is declared by the Federal food officials to have been very great, despite the fact that compilation of the total savings has not been possible to date. In notifying the Hotel Chairmen on the staffs of the Federal Administration of the decision to rescind the present food regulations the Hotel Division of the Food Administration asked that they hold themselves in readiness to assist in putting into effect any specific measure which public eating places, through developments in world relief, may in the future be called upon to carry out. The twelve general orders provided that no public eating place should serve bread or toast as a garniture or under meat, allow any bread to be brought to the table until after the first course, or serve to one patron at anyone meal more than one kind of meat. Bacon was barred as a garniture. A half ounce of butter was regarded as a portion, and cheese was limited to a half ounce for a meal. Nos. 8 and 9 referred to the sugar restriction. The others referred to waste and the use of cream and butter fats. Conservation Still Urged. Notwithstanding the lifting of restrictions the Food Administration will not cease its activities entirely until a Presidential proclamation releases the public from the Food Control act, which may be some months in the future. Meanwhile, particular attention will be paid to profiteering and speculation in licensed food products. The profit and margin rules will be enforced as they have during the last few months. The New York Federal Food Board issued a statement yesterday urging the proprietors of eating places to continue conservation of foodstuffs. "There should be no waste or extravagance in the use of any foods," said the statement. "All food should be prepared and served with the idea constantly in mind that America must send 20,000,000 tons of food to hungry Europe during the next twelve months and that the greater part of this food can be secured only by saving." The board made public the following telegram from the Food Administration at Washington: "Partial demobilization of the Food Administration and the withdrawal of many of its rules and regulations have given the impression in some quarters that all activities have ceased, or are shortly to cease. This is not the case. The act imposes upon the administration certain obligations, which continue until Presidential proclamation releases us from the Food Control act, and particularly the obligation to curb profiteering and speculation in licensed food products. This function must continue to be performed, and there is not intention of relaxing in this direction. It has been possible, now that peace is assured, to cancel many requirements for reports and many of the details of the regulations, but the profit and margin rules have been, for the most part, retained, and will be enforced by revocation of license and other appropriate penalties. It is expected that it will be possible from time to time to remove certain commodities from the license list, but this will be limited to commodities which do not seem likely to be subject to possibility of speculation and profiteering." The above propaganda poster from the Chicago division of the US Food Administration, features doughtboys at a mess table and reads "You Saved Food for Them, Now Save to Make Their Victory Complete. Famine has spread throughout Europe - Anarchy is following. Feed the starving millions and Bolshevism will vanish. Are you doing your part? Eating only what you need - not all that you can. America must continue to save food. Live simply - follow the doctrine of the clean plate. The sooner normal conditions are established in Europe the sooner our boys can come home. Will you help bring them back quickly? Eat less, waste nothing." Playing on fears of the 1917 Russian Revolution and the spread of socialism in Europe, the United States Food Administration used the admiration for "our boys" to convince Americans to keep up their thrifty wartime ways, even as food restrictions were being relaxed. Christmas, 1918, was likely a very happy one for most Americans - the war was over, the danger of German invasion a thing of the past, and the United States and her Allies victorious. Being able to have a basket of bread and butter before a restaurant dinner of steak probably didn't hurt, either. But many American soldiers remained in Europe, helping rebuild villages and roads, burying the dead, and otherwise securing the countryside. And 1919 would hold domestic unrest for the United States. It was the war to end all wars, and it changed the global balance of power, and Western society, forever. If you enjoyed this World War Wednesday post, consider becoming a member of The Food Historian! You can join online here, or you can join us on Patreon. Members get access to members-only sections of this website, special updates, plus discounts on future events and classes. And you'll help support free content like this for everyone. Join today!

0 Comments

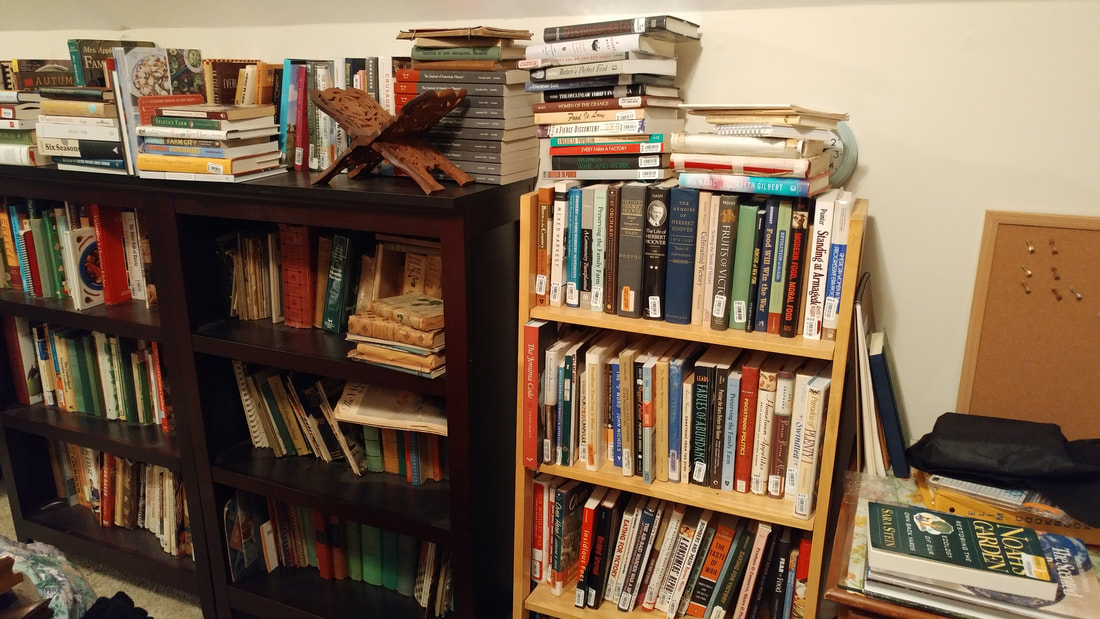

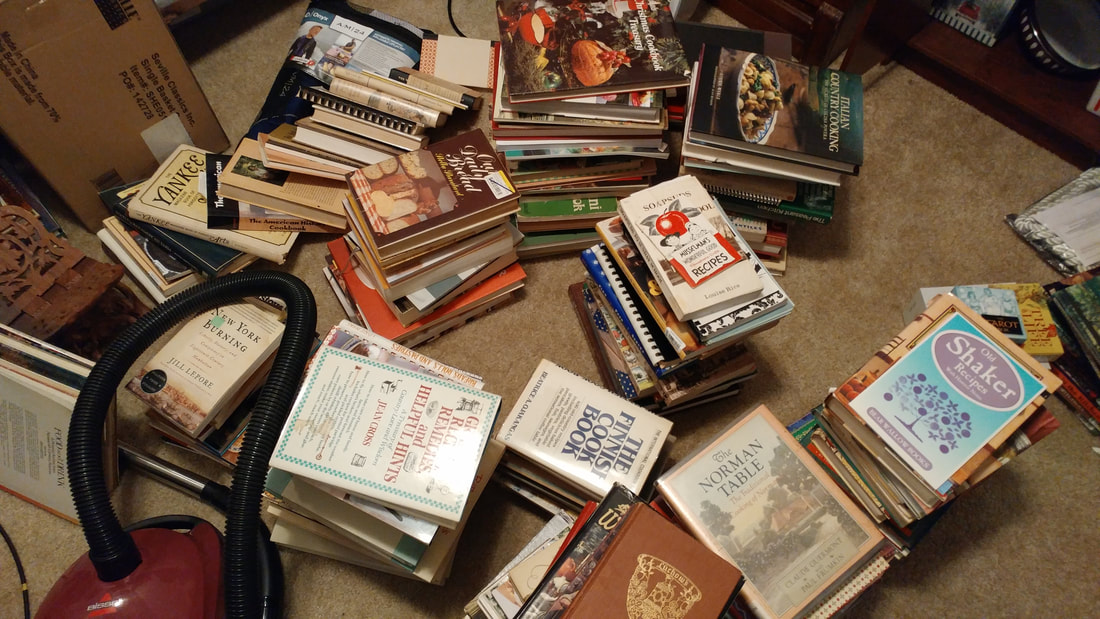

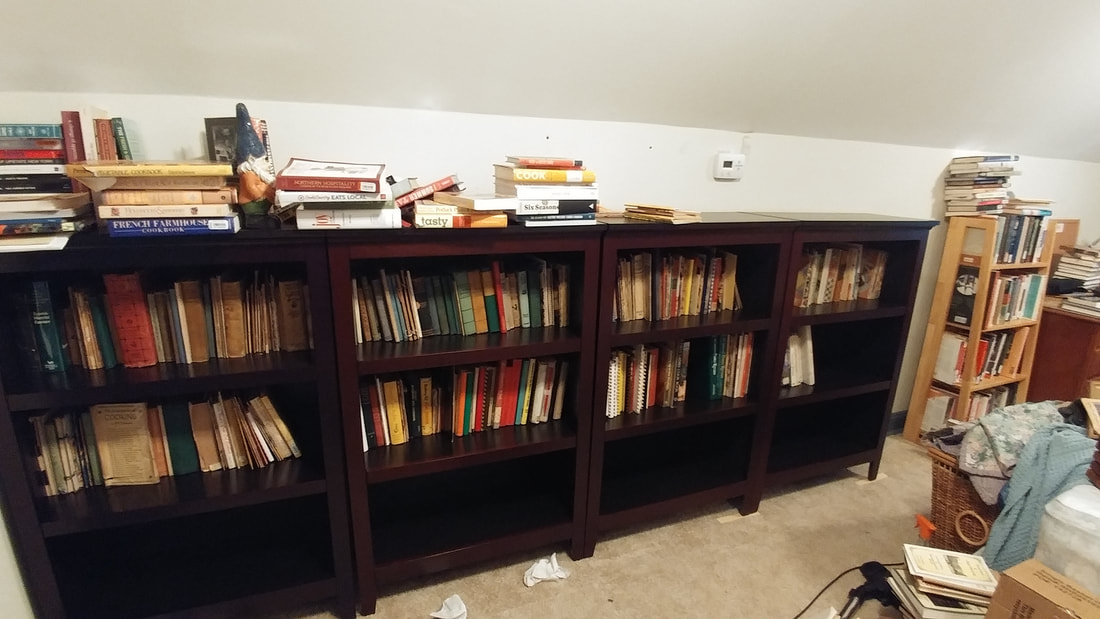

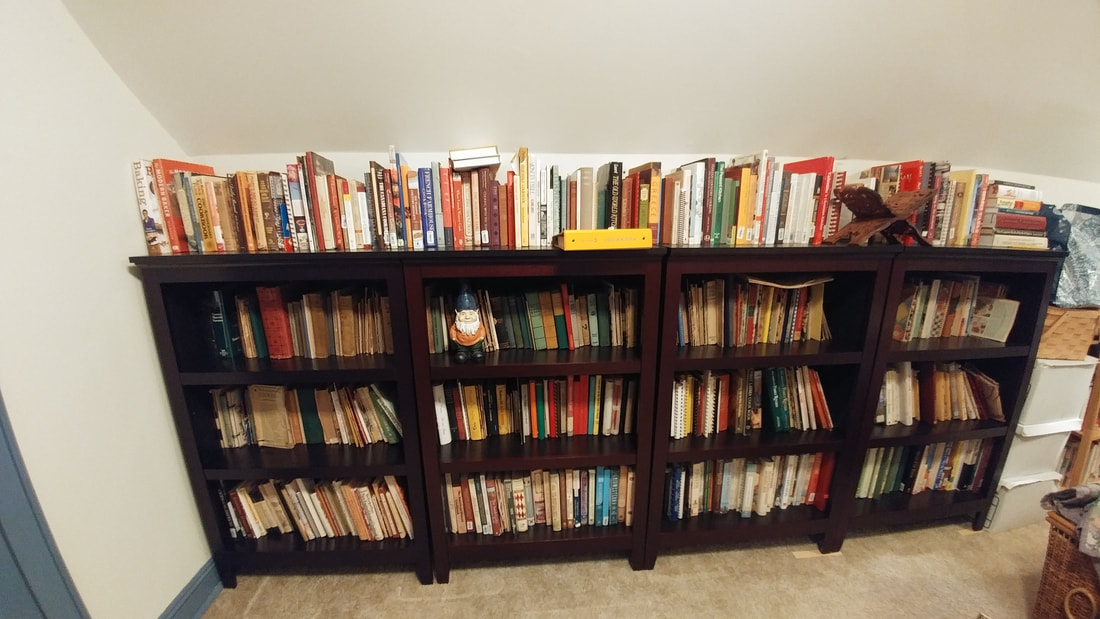

The holidays are coming soon, and with it comes house guests! Which means that my office-cum-guest-room needed a serious cleaning and reorganizing. Y'know when you have an unused space in your house? And it just collects STUFF? That was our guest room. It's still not at 100%, but we're at like, 95%, which is good. A few more trips to the thrift store and we'll be back in business. As part of this cleanup, I installed a new bookshelf (that I got... a year ago... for my birthday, lol.), pulled ALL of my books out of ALL of their hiding places, dusted down all the surfaces, and reinstalled them. Which means I put hands on every book on food, cooking, and food history I own. And there are a lot of them! A number were gifts that I hadn't even looked at yet. But it was so nice to review everything and not only realize all the treasures I have, but to get excited again for delving into food history of all kinds. I have my books organized a bit differently perhaps than some. All of my "American" cookbooks I have organized largely chronologically. All of my "foreign" cookbooks I have organized by country/region. And then I have all of my more modern books categorized by type of cookbook - baking, dessert, Christmas (!), food preservation, old-fashioned/country, and vegetarian. I haven't counted them all, but I'm already planning to get more matching bookshelves (don't they look so nice?) so I can stop squirreling books away in, say, the drawers of what is supposed to be bedroom furniture. As you can see, I have a bit of a problem, but also a huge opportunity. :D At some point this winter I hope to update the Wassberg Food Library and do some digitizing of some of the cookbooklets in my collection to share with the world, so stay tuned! If you enjoyed this blog post (and you love vintage cookbooks as much as I do), consider becoming a member of The Food Historian! You can join online here, or you can join us on Patreon. Members get access to members-only sections of this website (which will feature some of those digitized cookbooks!), special updates, plus discounts on future events and classes. Plus, you'll help support free content like this for everyone. Join today!

This article, from the December, 1942 issue of Good Housekeeping magazine, illustrates the first Christmas under rationing for Americans. Although the Japanese had attacked Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941, rationing did not go into effect until 1942. Good Housekeeping set the standard for women's magazines in the period, and had the still-famous "Good Housekeeping Seal of Approval" to its name. But in this instance, the magazine, as many other publications in the period, served as an arm of the government's propaganda machine. Here, the article outlines the Basic 7 nutrition recommendations and gives advice for how to shop around shortages and rationing. The article has no author, which is another clue that it probably came straight from Uncle Sam's on-staff nutritionists and home economists. "PLAN YOUR HOLIDAY MEALS THIS WAY AND YOU'LL MEET Uncle Sam's recommendations FOR NUTRITIOUS MEALS""Planning Is Important. It's imperative this year to cut down on deliveries and trips to market, to shop early in the week, so there will be less crowding in the stores, to stock up on staples, and to plan for the purchase of perishables, so the refrigerator is never overcrowded. And we should not go back on Uncle Sam by failing to measure up to his recommendations for truly nutritious meals. All this means planning ahead. So before you go to market, plan your meals, if possible, for the entire holiday weekend, Thursday to Monday. Plan each day as a unit, with an eye on the government food chart. Then make out your market listsone for staples, another for perishables. And off you go with your Victory marketbag or basket! "Your Grocer's Shelves. In checking your market list at the grocer's, you may find that some items are missing. Neither the grocer nor the food manufacturers can help this. Before products get to the grocer's shelves this year, Uncle Sam has appropriated what he needs for the armed forces and for our allies. This means that little, if any, of some foods is left for civilians. However, you still will find such a wide variety in foods on the grocer's shelves that you easily can choose substitutes. Here is where Uncle Sam's nutrition chart will come to your aid, so take it to market with you. Don't be surprised, either, if you find old favorites in new containerssome in glass instead of tin, some in various types of paper package. Whatever the kind of package, the quality of your favorite brands will not fail you. "Your Pantry Shelf. While you are giving your order, don't forget to include a reserve supply of those staple groceries you depend on regularly or in an emergency. This practice is real conservation. It will save trips to market, deliveries, and phone calls. Tin Cans Are Precious. You all know that tin and steel are scarce and that the tin cans you have been depending on are made of steel plated with tin. Because of this scarcity, used cans are being salvaged. The tin plating is removed, and this, with the steel, is used for new cans. We are told that 250 used cans will produce 200 new ones. Need we urge you then to save every can? Remove labels, wash cans thoroughly, remove top and bottom, and then flatten each can with the foot until the sides nearly meet. Be sure to leave a small space, as this is necessary for the detinning process. Remember, too, that unless the cans are really clean, they cannot be salvaged. If collections are tardy, take the cans in your market basket to a collection center. Saving cans is your patriotic privilege. "Uncle Sam's Food Rules. Use these rules in planning each day's menus: Milk and Milk Products - at least a pint for everyone - more for children - or cheese or evaporated or dried milk. Oranges, Tomatoes (and Tomato Juice), Grapefruit - or raw cabbage or salad greens - at least one of these. Green or Yellow Vegetables (market, canned, or quick-frozen) - one big helping or more, some raw, some cooked. Other Vegetables, Fruits (fresh, dried, canned, or quick-frozen) - potatoes, other vegetables or fruits in season. Bread and Cereal (including cereal restored to whole-grain nutritive value) whole-grain products or enriched white bread and flour. Meat, Poultry, or Fish - dried beans, peas, or nuts occasionally. Eggs - at least 3 or 4 a week, cooked as you choose - or in "made" dishes. Butter and Other Spreads (including margarines fortified with vitamin A) vitamin-rich fats, peanut butter, and similar spreads. Then eat other foods you also like. "Our Planned Holiday Menus. We followed the above rules in planning the menus given below. To illustrate: granting that breakfast provided a citrus fruit or tomato juice, a cereal, but no egg, we have eggs in the Cheese Bread Pudding, and we have meat for luncheon and cheese for dinner, to meet the protein quota for the day. Minerals and vitamins are taken care of with the carrot cole slaw, molasses cookies, fruit gelatin (gelatin is an excellent carrier of fruit, etc.), vegetable-juice cocktail, broccoli, salad, apples, etc. Enriched flour is used in shortcake, pie, cookies, and cheese pudding, and butter or margarine is used both as a spread and as an ingredient in some of the dishes. Milk is served at both meals and is used in the cheese pudding. Broccoli is the green vegetable. Isn't it simple to check your meals for their food value? And isn't it a great reward to know that your family is well fed? So why not make this part of your meal planning? "Now for our holiday menus, with recipes. DAY BEFORE CHRISTMAS Luncheon *Hamburger Shortcakes Carrot Cole Slaw Fruit or * Coffee Almond Jelly Molasses Cookies Milk Dinner Hot Vegetable-Juice Cocktail *Cheese Bread Pudding Broccoli Tossed Lima-Bean and Beet Salad Bread Sticks * Deep-Dish Quince-Apple Pie Milk CHRISTMAS DAY Dinner * Cranberry-Juice Cocktail * Carrot-Cheese Hors d'Oeuvres Roast Turkey *Sweet-Potato Stuffing Giblet or Mushroom Gravy * Brussels Sprouts with Onions String-Bean Succotash Celery Pickles Pickled Fruits Enriched Bread * Steamed Christmas Puddings with * Strawberry Sauce Roasted Walnuts Coffee Evening Snack (For Those Who Wish It) Oyster Stew Toasted Crackers Fruit Bowl Coffee DAY AFTER CHRISTMAS Luncheon * Luncheon Rarebit Sandwiches Celery Chocolate-Flavored Milk Drink Dinner Sauteed Lamb's Liver * Mashed Potato-Turnips Canned or Quick-Frozen Peas Whole-Wheat Bread *Jellied Grape Salad Milk Coffee SUNDAY AFTER CHRISTMAS Dinner * Turkey Fricassee on Crumb Noodles * Vinaigrette Spinach Baked Acorn Squash Enriched Bread Canned Cranberry Sauce * Marble Ice Cream Coffee Supper Hot Canned Consomme Madrilene Canned-Tongue and Lettuce Sandwiches Cookies Milk Coffee *Recipe given in article" I won't transcribe all of the recipes here (there are so many of them!), but most are typical of the 1940s and designed to use up leftovers (Turkey Fricassee on Crumb Noodles) or organ meats like liver or canned tongue. The meals themselves, except for dinner Christmas Day, are also very simple, emphasizing starches and vegetables livened up with cheese and a few interesting desserts. The "Dinner" served on Christmas Day was likely intended to be a noon or afternoon meal. Hence the "Evening Snack" of oyster stew ("for those who wish it" - in case they're too full still from dinner) - an American Christmas tradition (usually using canned oysters) dating back to the Victorian era. Conspicuously absent from this menu is the plethora of Christmas cookies we are now so used to. But perhaps that's a good thing. Perhaps if we adopted the 1942 stick-to-your-ribs steamed Christmas pudding, it might leave us too full for cookies anyway. How do your holiday dinner traditions line up to 1942? Do you have any traditional ways of dealing with leftovers? I'm trying to convince my family to do "snack Christmas" this year and avoid the big meal. There are only a few of us, so it doesn't make sense to cook so many dishes. Everyone prefers my mother-in-law's dill dip with rye bread, my brother-in-law's hot and cheesy jalapeno dip with Ritz crackers, and other snacks like Christmas cookies, port wine cheese-stuffed celery, and salted nuts, anyway. We'll see how successful I am! Many thanks to Cornell University for digitizing ALL of Good Housekeeping, plus a bunch of other amazing food- and home-economics-related titles at the Home Economics Archive. If you enjoyed this World War Wednesday post, consider becoming a member of The Food Historian! You can join online here, or you can join us on Patreon. Members get access to members-only sections of this website, special updates, plus discounts on future events and classes. And you'll help support free content like this for everyone. Join today!

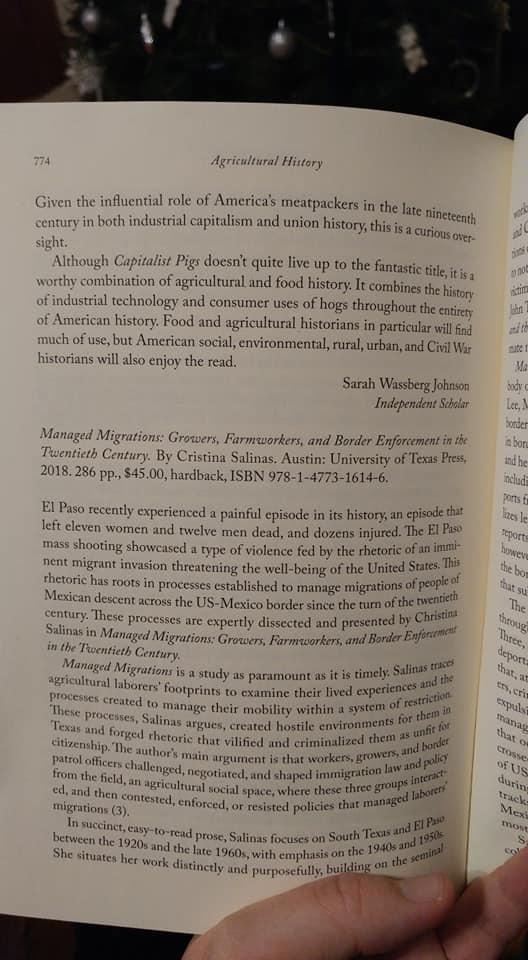

Okay folks, just 6 months after submitting and 9 months after receiving the invitation and book, my review of Capitalist Pigs is finally in print in the latest issue of Agricultural History - the journal of the Agricultural History Society. It's a pretty great issue, so I recommend you check out the few articles they have put up online. Alas, my review is not one of them, BUT! Being the rebel that I am, and seeing that I wrote this review for free (albeit in exchange for an advanced copy of the book, which was pretty cool), I'm going to do you a solid and post it here for you to read for yourself. For photographic proof, click through the images above! Capitalist Pigs: Pigs, Pork, and Power in America. By J.L. Anderson. Morgantown: West Virginia University Press, 2018. 300 pp., $34.99, paperback, ISBN 978-1-946684-73-8. “Capitalist pigs” is a term most frequently attributed to stereotypical Soviet protagonists describing Americans, or perhaps fat hogs in suits and top hats representing greedy businessmen in political cartoons. But in Capitalist Pigs: Pigs, Pork, and Power in America, J.L. Anderson puts a clever turn on the phrase as he explores the role of pigs and pork in America from the early Colonial period to the present. In Capitalist Pigs, Anderson argues that hogs have played a unique role in the development of the United States, and that the United States played a unique role in the development of the hog. “Americans maximized opportunities for the proliferation of the hog, even amid changing values and ideals about empire, agriculture, cities, and health.” (5). In particular, Anderson emphasizes that the story of the hog in America is one of excess, as farmers and marketers alike attempted to “transcend limits” on production. Capitalist Pigs covers the Colonial period to the present in the United States and is organized thematically rather than chronologically. Anderson covers such topics as free-range hogs and their influence on early settlements, pork consumption and its shifting role from frontier and working class food to re-branded “other white meat,” early industrialization of pork production and husbandry, including a discussion of hog cholera and enclosure, the role of the hog as garbage disposal, from our earliest urban areas to the industrialized present, and finally with a discussion of the modern industrialization of the hog, including changing its very physique to match modern consumer tastes and the controversial rise of confined animal feeding operations (CAFOs). Capitalist Pigs is well-researched and the broad chronology of the book provides a sweeping view of the influence of the hog on American culture and development throughout the centuries, giving needed context to historians of all stripes. Anderson is at his most compelling when he includes the voices of marginalized people and his sections on indigenous populations, enslaved people, and the Civil Rights movement are among his best. For urban and environmental historians, the discussion of the role of hogs in reshaping the landscape and the transition of urban spaces to exclude them, even as they continued to operate as waste disposal systems, will be of particular interest. Twentieth century historians, particularly agriculture historians, will be impressed by his discussion of the industrialization of hog production and marketing from the 1940s on. Anderson’s background as a public historian means his writing is clear, straightforward, and free of jargon and unnecessarily convoluted sentences. His writing style is engaging and would appeal to not only professional historians, but likely students and laypeople as well. Although Anderson’s writing style is clear, his main arguments are not. It seems as though Anderson could not quite decide whether to write Capitalist Pigs as a more technical agricultural history, or as a social history, and decided to split the difference. Anderson notes the influence of pigs in the institution of slavery, subsistence farms, and as a “mortgage lifter.” But the primary argument outlined in the introduction is focused instead on how Americans changed the pig. An interesting, if somewhat divergent take from the usual social history bent of most food histories, the argument is ultimately a weak one. Although Anderson discusses extensively in the latter half of the book how farmers industrialized and economized pork production and even changed the body shape of pigs to accommodate changing consumer tastes, he spends little time discussing the effects on the pigs themselves. Although breeding is mentioned frequently, the only mention of any particular breed in the entire book is about how heritage breeds have become more fashionable in modern nose-to-tail cuisine and sustainable agriculture (172-73), despite the fact that discussing the various breeds of pig throughout the book would have lent weight to later industrial changes and changing consumer tastes. He also skirts around the effects of industrialization on the hogs themselves - only in a photo caption does he mention accusations of cruelty in hog confinement operations (201). In addition, although the title and discussions in several chapters imply that hogs played a significant role in building America’s capitalist system, Anderson does not quite make those connections clear throughout the chapters, and discussion of meat-packing beyond the 1850s is conspicuously absent. Given the influential role of America’s meat-packers in the late nineteenth century in both industrial capitalism and union history, this is a curious oversight. Although Capitalist Pigs doesn’t quite live up to the premise of its fantastic title, it is a worthy combination of agriculture and food history - combining the history of industrial technology and consumer uses of hogs throughout the entirety of American history. Food and agriculture historians in particular will find much of use, but American social, environmental, rural, urban, and Civil War historians will also enjoy the read. If you enjoyed this book review, consider becoming a member of The Food Historian! You can join online here, or you can join us on Patreon. Members get access to members-only sections of this website, special updates, plus discounts on future events and classes. And you'll help support free content like this for everyone. Join today!

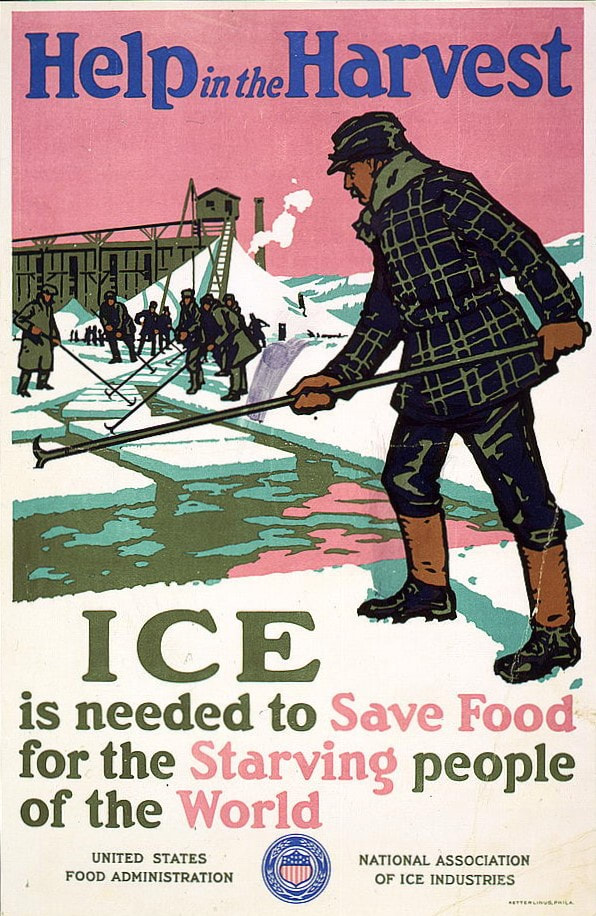

"Help in the Harvest - ICE is needed to Save Food for the Starving people of the World." Produced by the United States Food Administration in conjunction with the National Association of Ice Industries. This propaganda poster is a bit unusual for several reasons. For one, it does not actually feature a particular foodstuff. For another, the reason for this poster is the result of a very unique time period in American history. For most of the 19th century and into the early 20th, if you wanted to keep food cold, you had to harvest natural ice on a pond, lake, or river, store it in an ice house packed with straw or sawdust, and hope that enough of it survived the spring, summer, and fall for you to keep your ice box well-chilled with enormous blocks of ice. If you lived in an urban area, the ice man would deliver weekly a giant block of natural ice to help keep meats, milk, and leftovers adequately chilled to prevent short-term spoilage. By the time of the U.S. entrance into the First World War, artificial refrigeration was on the rise, and frozen food storage and refrigerated rail cars were new and effective technologies. However, artificial ice production, advertised as more pure than natural ice, which often came from polluted rivers and lakes, required ammonia to produce ice. But ammonia was also used to produce munitions, and during the war a shortage ensued. The harvest of natural ice was encouraged to assist with the shortage and ice was promoted to prevent food waste from spoilage. Following the war, the spread of electricity led to the increasing popularity of electric refrigerators. Present before the war but enormously expensive, by the 1920s they were approaching ubiquity in the nation's urban areas. If you enjoyed this World War Wednesday post, consider becoming a member of The Food Historian! You can join online here, or you can join us on Patreon. Members get access to members-only sections of this website, special updates, plus discounts on future events and classes. And you'll help support free content like this for everyone. Join today!

|

AuthorSarah Wassberg Johnson has an MA in Public History from the University at Albany and studies early 20th century food history. Archives

July 2024

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed