|

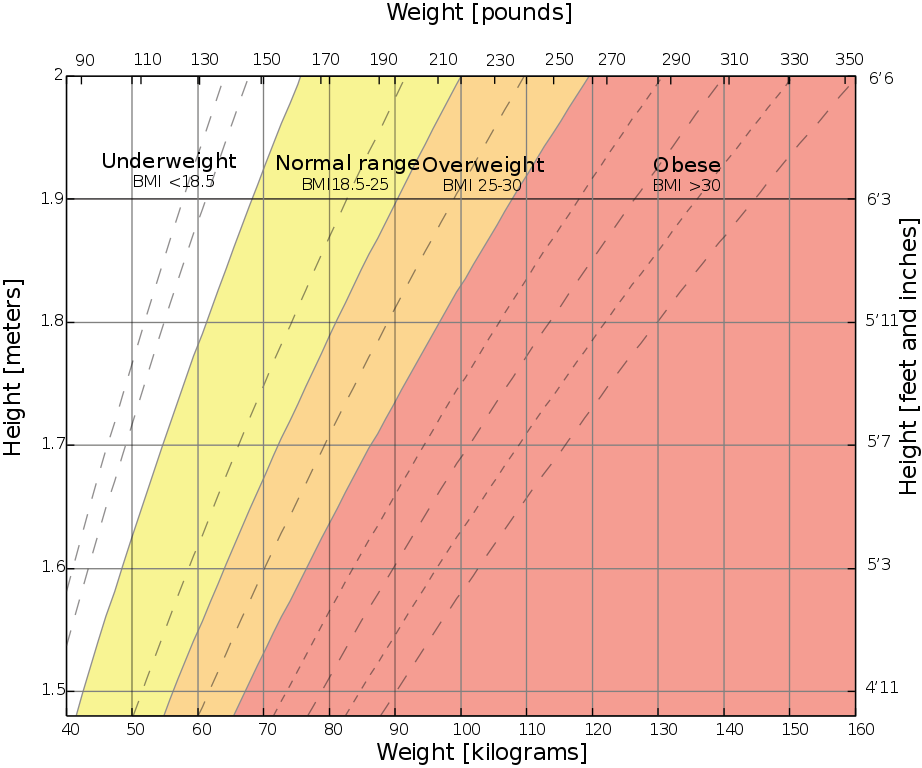

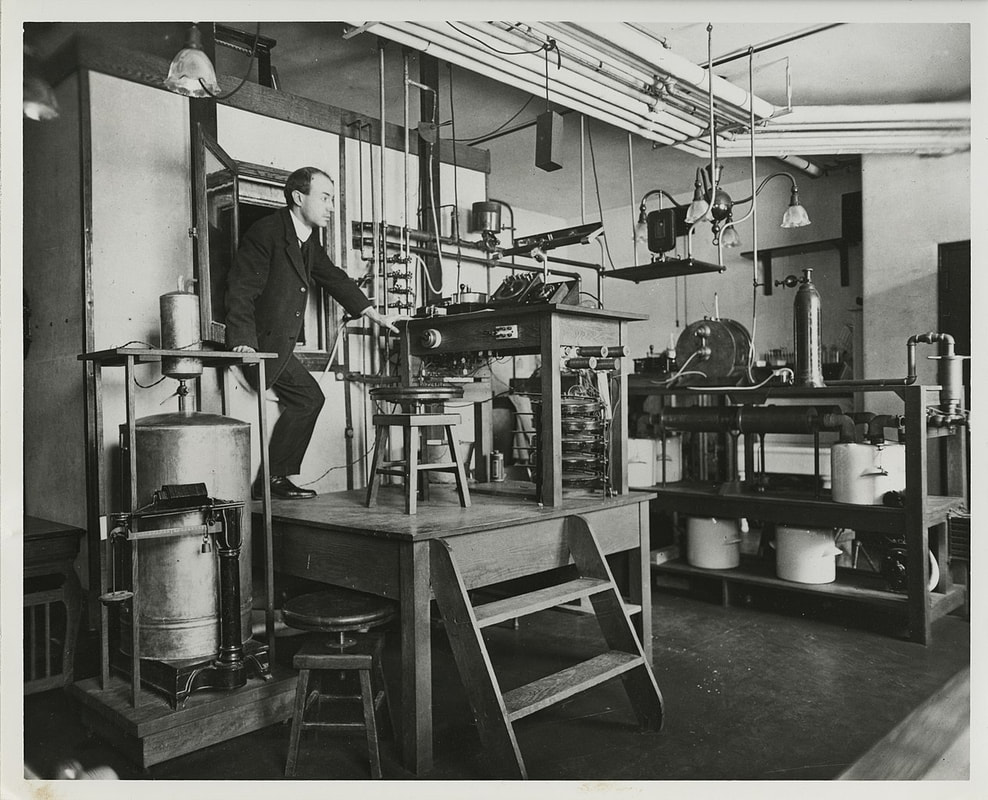

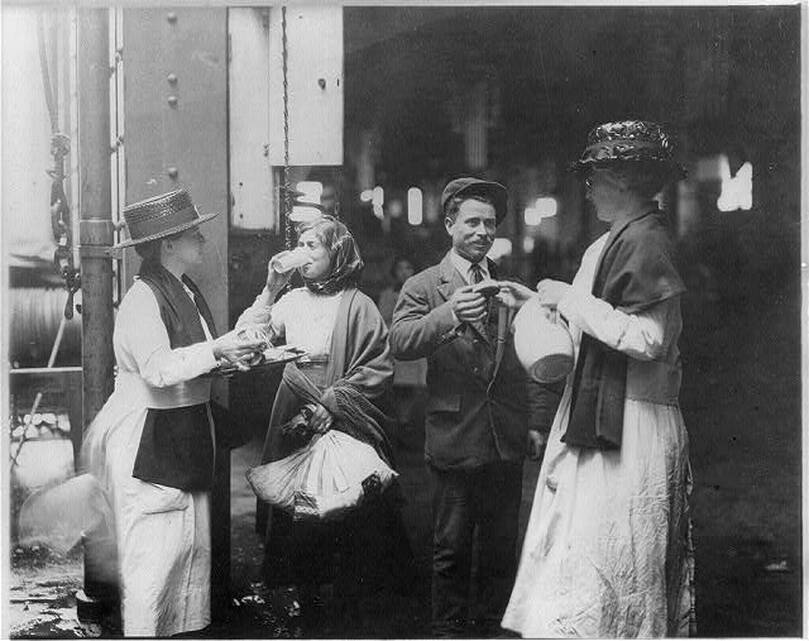

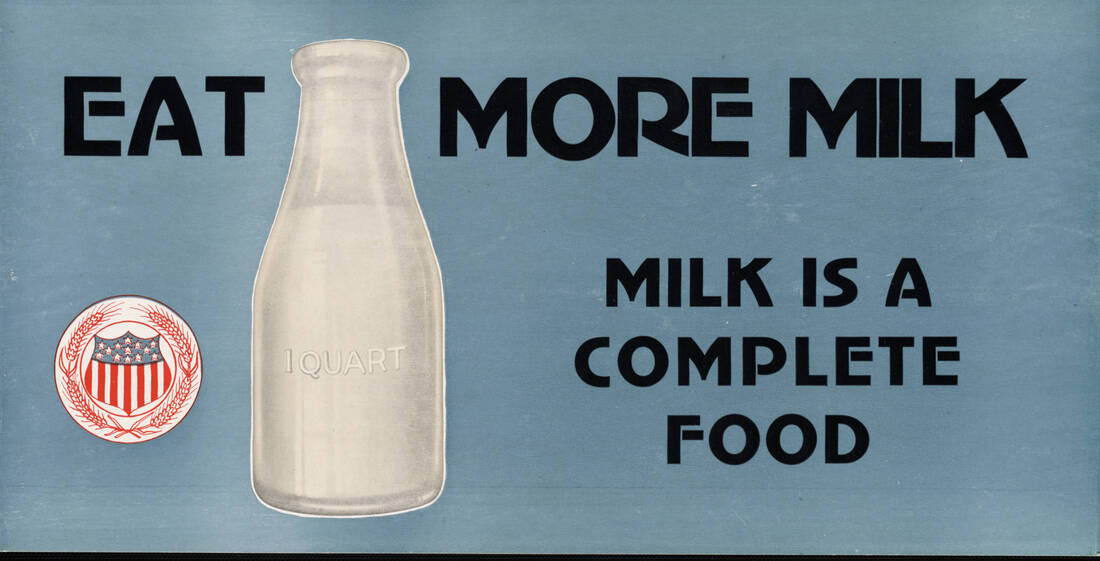

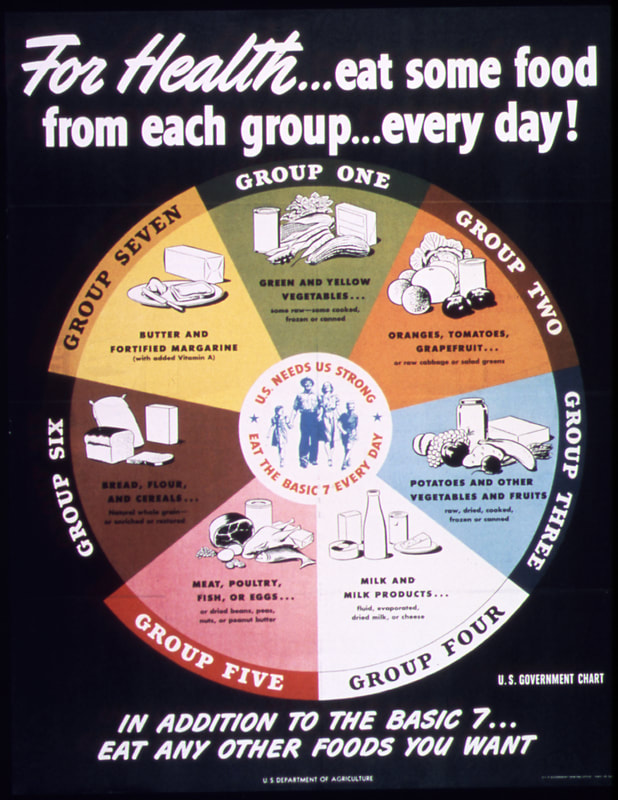

The short answer? At least in the United States? Yes. Let's look at the history and the reasons why. I post a lot of propaganda posters for World War Wednesday, and although it is implied, I don't point out often enough that they are just that - propaganda. They are designed to alter peoples' behavioral patterns using a combination of persuasion, authority, peer pressure, and unrealistic portrayals of culture and society. In the last several months of sharing propaganda posters on social media for World War Wednesday, I've gotten a couple of comments on how much they reflect an exclusively White perspective. Although White Anglo-Saxon Protestant culture was the dominant culture in the United States at the time, it was certainly not the only culture. And its dominance was the result of White supremacy and racism. This is reflected in the nutritional guidelines and nutrition science research of the time. The First World War takes place during the Progressive Era under a president who re-segregated federal workplaces that had been integrated since Reconstruction. It was also a time when eugenics was in full swing, and the burgeoning field of nutrition science was using racism as justifications for everything from encouraging assimilation among immigrant groups by decrying their foodways and promoting White Anglo-Saxon Protestant foodways like "traditional" New England and British foods to encouraging "better babies" to save the "White race" from destruction. Nutrition science research with human subjects used almost exclusively adult White men of middle- and upper-middle class backgrounds - usually in college. Certain foods, like cow's milk, were promoted heavily as health food. Notions of purity and cleanliness also influenced negative attitudes about immigrants, African Americans, and rural Americans. During World War II, Progressive-Era-trained nutritionists and nutrition scientists helped usher in a stereotypically New England idea of what "American" food looked like, helping "kill" already declining regional foodways. Nutrition research, bolstered by War Department funds, helped discover and isolate multiple vitamins during this time period. It's also when the first government nutrition guidelines came out - the Basic 7. Throughout both wars, the propaganda was focused almost exclusively on White, middle- and upper-middle-class Americans. Immigrants and African Americans were the target of some campaigns for changing household habits, usually under the guise of assimilation. African Americans were also the target of agricultural propaganda during WWII. Although there was plenty of overt racism during this time period, including lynching, race massacres, segregation, Jim Crow laws, and more, most of the racism in nutrition, nutrition science, and home economics came in two distinct types - White supremacy (that is, the belief that White Anglo-Saxon Protestant values were superior to every other ethnicity, race, and culture) and unconscious bias. So let's look at some of the foundations of modern nutrition science through these lenses. Early Nutrition ScienceNutrition Science as a field is quite young, especially when compared to other sciences. The first nutrients to be isolated were fats, carbohydrates, and proteins. Fats were the easiest to determine, since fat is visible in animal products and separates easily in liquids like dairy products and plant extracts. The term "protein" was coined in the 1830s. Carbohydrates began to be individually named in the early 19th century, although that term was not coined until the 1860s. Almost immediately, as part of nearly any early nutrition research, was the question of what foods could be substituted "economically" for other foods to feed the poor. This period of nutrition science research coordinated with the Enlightenment and other pushes to discover, through experimentation, the mechanics of the universe. As such, it was largely limited to highly educated, White European men (although even Wikipedia notes criticism of such a Euro-centric approach). As American colleges and universities, especially those driven by the Hatch Act of 1877, expanded into more practical subjects like agriculture, food and nutrition research improved. American scientists were concerned more with practical applications, rather than searching for knowledge for knowledge's sake. They wanted to study plant and animal genetics and nutrition to apply that information on farms. And the study of human nutrition was not only to understand how humans metabolized foods, but also to apply those findings to human health and the economy. But their research was influenced by their own personal biases, conscious and unconscious. The History of Body Mass Index (BMI)Body Mass Index, or BMI, is a result of that same early 19th century time period. It was invented by Belgian mathematician Lambert Adolphe Jacques Quetelet in the 1830s and '40s specifically as a "hack" for determining obesity levels across wide swaths of population, not for individuals. Quetelet was a trained astronomist - the one field where statistical analysis was prevalent. Quetelet used statistics as a research tool, publishing in 1835 a book called Sur l'homme et le développement de ses facultés, ou Essai de physique sociale, the English translation of which is usually called A Treatise on Man and the Development of His Faculties. In it, he discusses the use of statistics to determine averages for humanity (mainly, White European men). BMI became part of that statistical analysis. Quetelet named the index after himself - it wasn't until 1972 that researcher Ancel Keys coined the term "Body Mass Index," and as he did so he complained that it was no better or worse than any other relative weight index. Quetelet's work went on to influence several famous people, including Francis Galton, a proponent of social Darwinism and scientific racism who coined the term "eugenics," and Florence Nightingale, who met him in person. As a tool for measuring populations, BMI isn't bad. It can look at statistical height and weight data and give a general idea of the overall health of population. But when it is used as a tool to measure the health of individuals, it becomes extremely flawed and even dangerous. Quetelet had to fudge the math to make the index work, even with broad populations. And his work was based on White European males who he considered "average" and "ideal." Quetelet was not a nutrition scientist or a doctor - this "ideal" was purely subjective, not scientific. Despite numerous calls to abandon its use, the medical community continues to use BMI as a measure of individual health. Because it is a statistical tool not based on actual measures of health, BMI places people with different body types in overweight and obese categories, even if they have relatively low body fat. It can also tell thin people they are healthy, even when other measurements (activity level, nutrition, eating disorders, etc.) are signaling an unhealthy lifestyle. In addition, fatphobia in the medical community (which is also based on outdated ideas, which we'll get to) has vilified subcutaneous fat, which has less impact on overall health and can even improve lifespans. Visceral fat, or the abdominal fat that surrounds your organs, can be more damaging in excess, which is why some scientists and physicians advocate for switching to waist ratio measurements. So how is this racist? Because it was based on White European male averages, it often punishes women and people of color whose genetics do not conform to Quetelet's ideal. For instance, people with higher muscle mass can often be placed in the "overweight" or even "obese" category, simply because BMI uses an overall weight measure and assumes a percentage of it is fat. Tall people and people with broader than "ideal" builds are also not accurately measured. The History of the CalorieAlthough more and more people are moving away from measuring calories as a health indicator, for over 100 years they have reigned as the primary measure of food intake efficiency by nutritionists, doctors, and dieters alike. The calorie is a unit of heat measurement that was originally used to describe the efficiency of steam engines. When Wilbur Olin Atwater began his research into how the human body metabolizes food and produces energy, he used the calorie to measure his findings. His research subjects were the White male students at Wesleyan University, where he was professor. Atwater's research helped popularize the idea of the calorie in broader society, and it became essential learning for nutrition scientists and home economists in the burgeoning field - one of the few scientific avenues of study open to women. Atwater's research helped spur more human trials, usually "Diet Squads" of young middle- and upper-middle-class White men. At the time, many papers and even cookbooks were written about how the working poor could maximize their food budgets for effective nutrition. Socialists and working class unionists alike feared that by calculating the exact number of calories a working man needed to survive, home economists were helping keep working class wages down, by showing that people could live on little or inexpensive food. Calculating the calories of mixed-food dishes like casseroles, stews, pilafs, etc. was deemed too difficult, so "meat and three" meals were emphasized by home economists. Making "American" FoodEfforts to Americanize and assimilate immigrants went into full swing in the late 19th and early 20th centuries as increasing numbers of "undesirable" immigrants from Ireland, southern Italy, Greece, the Middle East, China, Eastern Europe (especially Jews), Russia, etc. poured into American cities. Settlement workers and home economists alike tried to Americanize with varying degrees of sensitivity. Some were outright racist, adopting a eugenics mindset, believing and perpetuating racist ideas about criminology, intelligence, sanitation, and health. Others took a more tempered approach, trying to convince immigrants to give up the few things that reminded them of home - especially food. These often engaged in the not-so-subtle art of substitution. For instance, suggesting that because Italian olive oil and butter were expensive, they should be substituted with margarine. Pasta was also expensive and considered to be of dubious nutritional value - oatmeal and bread were "better." A select few realized that immigrant foodways were often nutritionally equivalent or even superior to the typical American diet. But even they often engaged in the types of advice that suggested substituting familiar ingredients with unfamiliar ones. Old ideas about digestion also influenced food advice. Pickled vegetables, spicy foods, and garlic were all incredibly suspect and scorned - all hallmarks of immigrant foodways and pushcart operators in major American cities. The "American" diet advocated by home economists was highly influenced by Anglo-Saxon and New England ideals - beef, butter, white bread, potatoes, whole cow's milk, and refined white sugar were the nutritional superstars of this cuisine. Cooking foods separately with few sauces (except white sauce) was also a hallmark - the "meat and three" that came to dominate most of the 20th century's food advice. Rooted in English foodways, it was easy for other Northern European immigrants to adopt. Although French haute cuisine was increasingly fashionable from the Gilded Age on, it was considered far out of reach of most Americans. French-style sauces used by middle- and lower-class cooks were often deemed suspect - supposedly disguising spoiled meat. Post-Civil War, Yankee New England foodways were promoted as "American" in an attempt to both define American foodways (which reflected the incredibly diverse ecosystems of the United States and its diverse populations) and to unite the country after the Civil War. Sarah Josepha Hale's promotion of Thanksgiving into a national holiday was a big part of the push to define "American" as White and Anglo-Saxon. This push to "Americanize" foodways also neatly ignores or vilifies Indigenous, Asian-American, and African American foodways. "Soul food," "Chinese," and "Mexican" are derided as unhealthy junk food. In fact, both were built on foundations of fresh, seasonal fruits, vegetables, and whole grains. But as people were removed from land and access to land, the they adapted foodways to reflect what was available and what White society valued - meat, dairy, refined flour, etc. Asian food in particular was adapted to suit White palates. We won't even get into the term "ethnic food" and how it implies that anything branded as such isn't "American" (e.g. White). Divorcing foodways from their originators is also hugely problematic. American food has a big cultural appropriation problem, especially when it comes to "Mexican" and "Asian" foods. As late as the mid-2000s, the USDA website had a recipe for "Oriental salad," although it has since disappeared. Instead, we get "Asian Mango Chicken Wraps," and the ingredients of mango, Napa cabbage, and peanut butter are apparently what make this dish "Asian," rather than any reflection of actual foodways from countries in Asia. Milk - The Perfect FoodCombining both nutrition research of the 19th century and also ideas about purity and sanitation, whole cow's milk was deemed by nutrition scientists and home economists to be "the perfect food" - as it contained proteins, fats, and carbohydrates, all in one package. Despite issues with sanitation throughout the 19th century (milk wasn't regularly pasteurized until the 1920s), milk became a hallmark of nutrition advice throughout the Progressive Era - advice which continues to this day. Throughout the history of nutritional guidelines in the U.S., milk and dairy products have remained a mainstay. But the preponderance of advice about dairy completely ignores that wide swaths of the population are lactose intolerant, and/or did not historically consume dairy the way Europeans did. Indigenous Americans, and many people of African and Asian descent historically did not consume cow's milk and their bodies often do not process it well. This fact has been capitalized upon by both historic and modern racists, as milk as become a symbol of the alt-right. Even today, the USDA nutrition guidelines continue to recommend at least three servings of dairy per day, an amount that can cause long term health problems in communities that do not historically consume large amounts of dairy. Nutrition Guidelines HistoryBecause Anglo-centric foodways were considered uniquely "American" and also the most wholesome, this style of food persisted in government nutritional guidelines. Government-issued food recommendations and recipes began to be released during the First World War and continued during the Great Depression and World War II. These guidelines and advice generally reinforced the dominant White culture as the most desirable. Vitamins were first discovered as part of research into the causes of what would come to be understood as vitamin deficiencies. Scurvy (Vitamin C deficiency), rickets (Vitamin D deficiency), beriberi (Vitamin B1 or thiamine deficiency), and pellagra (Vitamin B2 or niacin deficiency) plagued people around the world in the 19th and early 20th centuries. Vitamin C was the first to be isolated in 1914. The rest followed in the 1930s and '40s. Vitamin fortification took off during World War II. The Basic 7 guidelines were first released during the war and were based on the recent vitamin research. But they also, consciously or not, reinforced white supremacy through food. Confident that they had solved the mystery of the invisible nutrients necessary for human health, American nutrition scientists turned toward reconfiguring them every which way possible. This is the history that gives us Wonder Bread and fortified breakfast cereals and milk. By divorcing vitamins from the foods in which they naturally occur (foods that were often expensive or scarce), nutrition scientists thought they could use equivalents to maintain a healthy diet. As long as people had access to vitamins, carbohydrates, proteins, and fats, it didn't matter how they were delivered. Or so they thought. This policy of reducing foods to their nutrients and divorcing food from tradition, culture, and emotion dates back to the Progressive Era and continues to today, sometimes with disastrous consequences. Commodities & NutritionDivorcing food from culture is one government policy Indigenous people understand well. U.S. treaty violations and land grabs led to the reservation system, which forcibly removed Native people from their traditional homelands, divorcing them from their traditional foodways as well. Post-WWII, the government helped stabilize crop prices by purchasing commodity foods for use in a variety of programs operated by the United States Department of Agriculture (USDA), including the National School Lunch Program, Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children (WIC), and the Food Distribution Program on Indian Reservations (FDPIR) program. For most of these programs, the government purchases surplus agricultural commodities to help stabilize the market and keep prices from falling. It then distributes the foods to low-income groups as a form of food assistance. Commodity foods distributed through the FDPIR program were generally canned and highly processed - high in fat, salt, and sugar and low in nutrients. This forced reliance on commodity foods combined with generational trauma and poverty led to widespread health disparities among Indigenous groups, including diabetes and obesity. Which is why I was appalled to find this cookbook the other day. Commodity Cooking for Good Health, published by the USDA in 1995 (1995!) is a joke, but it illustrates how pervasive and long-lasting the false equivalency of vitamins and calories can be. The cookbook starts with an outline of the 1992 Food Pyramid, whose base rests on bread, pasta, cereal, and rice. It then goes to outline how many servings of each group Indigenous people should be eating, listing 2-3 servings a day for the dairy category, but then listing only nonfat dry milk, evaporated milk, and processed cheese as the dairy options. In the fruit group, it lists five different fruit juices as servings of fruit. It has a whole chapter on diabetes and weight loss as well as encouraging people to count calories. With the exception of a recipe for fry bread, one for chili, and one for Tohono O'odham corn bread, the remainder of the recipes are extremely European. Even the "Mesa Grande Baked Potatoes" are not, as one would assume from the title, a fun take on baked whole potatoes, but rather a mixture of dehydrated mashed potato flakes, dried onion soup mix, evaporated milk, and cheese. You can read the whole cookbook for yourself, but the fact of the matter is that the USDA is largely responsible for poor health on reservations, not only because it provides the unhealthy commodity foods, but also because it was founded in 1862, the height of the Indian Wars, during attempts by the federal government at genocide and successful land grabs. Although the Bureau of Indian Affairs (BIA) under the Department of the Interior was largely responsible for the reservation system, the land grant agricultural college system started by the Hatch Act was literally built on the sale of stolen land. In addition, the USDA has a long history of dispossessing Black farmers, an issue that continues to this day through the denial of farm loans. Thanks to redlining, people of color, especially Black people, often live in segregated school districts whose property taxes are inadequate to cover expenses. Many children who attend these schools are low-income, and rely on free or reduced lunch delivered through the National School Lunch Program, which has been used for decades to prop up commodity agriculture. Although school lunch nutrition efforts have improved in recent years, many hot lunches still rely on surplus commodities and provide inadequate nutrition. Issues That PersistEven today, the federal nutrition guidelines, administered by the USDA, emphasize "meat and three" style meals accompanied by dairy. And while the recipe section is diversifying, it is still all-too-often full of Americanized versions of "ethnic" dishes. Many of the dishes are still very meat- and dairy-centric, and short on fresh fruits and vegetables. Some recipes, like this one, seem straight out of 1956. The idea that traditional ingredients should be replaced with "healthy" variations, for instance always replacing white rice with brown rice or, more recently cauliflower rice, continues. Many nutritionists also push the Mediterranean Diet as the healthiest in the world, when in fact it is very similar to other traditional diets around the world where people have access to plenty of unsaturated fats, fruits and vegetables, whole grains, lean meats, etc. Even the name - the "Mediterranean Diet," implies the diets of everyone living along the Mediterranean. So why does "Mediterranean" always mean Italian and Greek food, and never Persian, Egyptian, or Tunisian food? (Hint: the answer is racism). Old ideas about nutrition, including emphasis on low-fat foods, "meat and three" style recipes, replacement ingredients (usually poor cauliflower), and artificial sweeteners for diabetics, seem hard to shake for many people. Doctors receive very little training in nutrition and hospital food is horrific, as I saw when my father-in-law was hospitalized for several weeks in 2019. As a diabetic with problems swallowing, pancakes with sugar-free syrup, sugar-free gelatin and pudding, and not much else were their solution to his needs. The modern field of nutritionists is also overwhelmingly White, and racism persists, even towards trained nutritionists of color, much less communities of color struggling with health issues caused by generational trauma, food deserts, poverty, and overwork. Our modern food system has huge structural issues that continue to today. Why is the USDA, which is in charge of promoting agriculture at home and abroad, in charge of federal nutrition programs? Commodity food programs turn vulnerable people into handy props for industrial agriculture and the economy, rather than actually helping vulnerable people. Federal crop subsidies, insurance, and rules assigns way more value to commodity crops than fruits and vegetables. This government support also makes it easy and cheap for food processors to create ultra-processed, shelf-stable, calorie-dense foods for very little money - often for less than the crops cost to produce. This makes it far cheaper for people to eat ultra-processed foods than fresh fruits and vegetables. The federal government also gives money to agriculture promotion organizations that use federal funds to influence American consumers through advertising (remember the "Got Milk?" or "The Incredible, Edible Egg" marketing? That was your taxpayer dollars at work), regardless of whether or not the foods are actually good for Americans. Nutrition science as a field has a serious study replication problem, and an even more serious communications problem. Although scientists themselves usually do not make outrageous claims about their findings, the fact that food is such an essential part of everyday life, and the fact that so many Americans are unsure of what is "healthy" and what isn't, means that the media often capitalizes on new studies to make over-simplified announcements to drive viewership. Key TakeawaysNutrition science IS a science, and new discoveries are being made everyday. But the field as a whole needs to recognize and address the flawed scientific studies and methods of the past, including their racism - conscious or unconscious. Nutrition scientists are expanding their research into the many variables that challenge the research of the Progressive Era, including gut health, environmental factors, and even genetics. But human research is expensive, and test subjects rarely diverse. Nutrition science has a particularly bad study replication problem. If the government wants to get serious about nutrition, it needs to invest in new research with diverse subjects beyond the flawed one-size-fits-all rhetoric. The field of nutrition - including scientists, medical professionals, public health officials, and dieticians - need to get serious about addressing racism in the field. Both their own personal biases, as well as broader institutional and cultural ones. Anyone who is promoting "healthy" foods needs to think long and hard about who their audience is, how they're communicating, and what foods they're branding as "unhealthy" and why. We also need to address the systemic issues in our food system, including agriculture, food processing, subsidies, and more. In particular, the government agencies in charge of nutrition advice and food assistance need to think long and hard about the role of the federal government in promoting human health and what the priorities REALLY are - human health? or the economy? There is no "one size fits all" recommendation for human health. Ever. Especially not when it comes to food. Because nutrition guidelines have problems not just with racism, but also with ableism and economics. Not everyone can digest "healthy" foods, either due to medical issues or medication. Not everyone can get adequate exercise, due to physical, mental, or even economic issues. And I would argue that most Americans are not able to afford the quality and quantity of food they need to be "healthy" by government standards. And that's wrong. Like with human health, there are no easy solutions to these problems. But recognizing that there is a problem is the first step on the path to fixing them. Further ReadingMany of these were cited in the text of the article above, but they are organized here for clarity. I have organized them based on the topics listed above. (note: any books listed below are linked as part of the Amazon Affiliate program - any purchases made from those links will help support The Food Historian's free public articles like this one). EARLY NUTRITION SCIENCE

A HISTORY OF BODY MASS INDEX (BMI)

THE HISTORY OF THE CALORIE

MAKING "AMERICAN" FOOD

MILK - THE PERFECT FOOD

NUTRITION GUIDELINES HISTORY

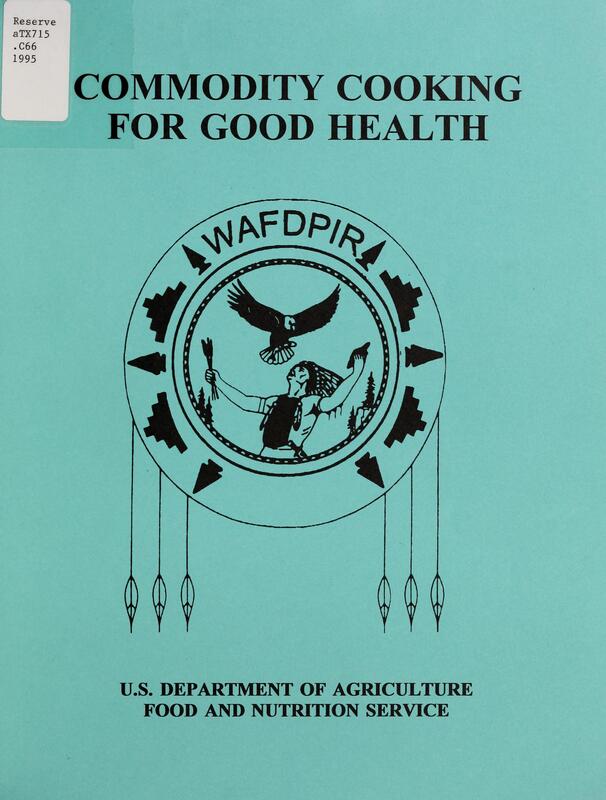

COMMODITIES AND NUTRITION

ISSUES THAT PERSIST

The Food Historian blog is supported by patrons on Patreon! Patrons help keep blog posts like this one free and available to the public. Join us for awesome members-only content like free digitized cookbooks from my personal collection, e-newsletter, and even snail mail from time to time! Don't like Patreon? Leave a tip!

1 Comment

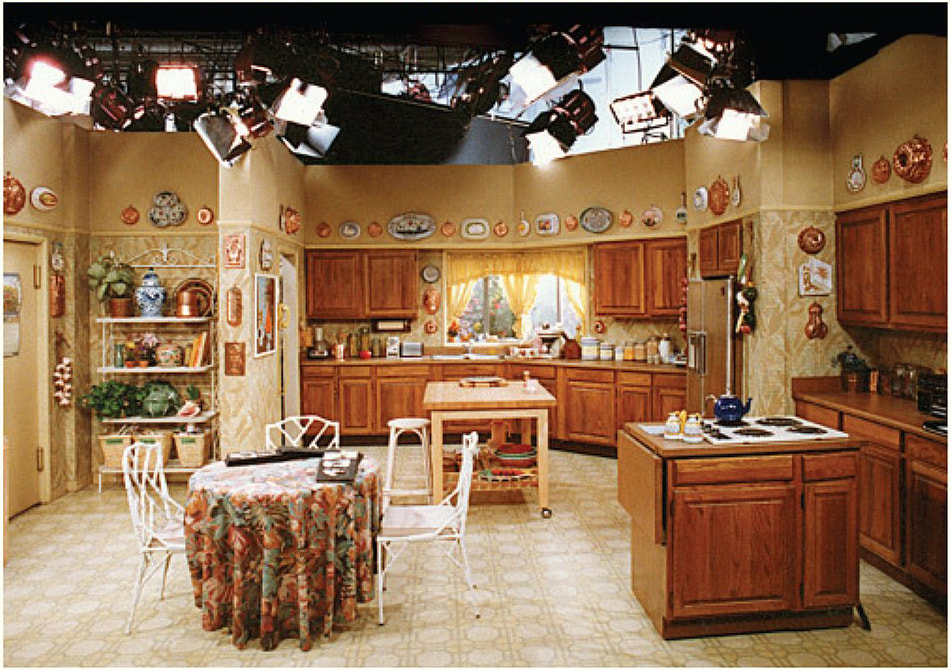

Somehow, I missed the Golden Girls growing up. The show first aired in 1985, the year I was born, and went off the air in 1992, when I was seven. But despite the fact that it was apparently syndicated on broadcast television all through my elementary and high school years, I missed it. I did not watch a single episode. Oh, I knew that it existed, and by college, thanks to the virality of the internet, I got the references. I watched Betty White on Hot in Cleveland and watched with glee as she roasted William Shatner and essentially became a saint of the internet age. Thanks to the internet, I knew that Bea Arthur was a patron saint of LGBTQ+ youth, too. But I never saw the show, even when I finally did get access to cable. When Betty White passed away on December 31, 2021, just a little over two weeks shy of her 100th birthday (coming up on January 17th), I decided to see what all the fuss was about. Just one episode in, I was totally hooked. Rose reminds me of Minnesota (I almost went to St. Olaf!), I love Blanche's Southern charm and unapologetic sexuality, and while I'm not a huge fan of how often the show made fun of Bea Arthur's appearance, I appreciate Dorothy's whip smarts and New Yorker bluntness and sarcasm. And who could say no to firecracker Sophia? I've been binging episodes ever since. Thank goodness there are so many of them. But one thing that really struck me was the division of household labor, which features fairly prominently in the first few episodes, as well as subsequent flashbacks (once the gay male cook in the pilot episode disappears, that is). The ladies grocery shop together, and argue over what to buy. There's discussion of household budgets. When people come to visit, the ladies help each other clean. And someone or another is always in the kitchen washing dishes, cooking, or having a late-night snack. And although Sophia, with her small-village-in-Sicily background is queen of the Sunday gravy, other characters cook, too. The four ladies on the show are mature adults - they've all run their own households, raised children, managed husbands, etc. It can't have been easy for them to come to an agreement on how to run the house, but they did. And it reminded me very strongly of a passage I read in a book I now can't remember and can't find (the perils of a historian's mind. If anyone knows this reference, please let me know!) - it described a home economics college program where in their senior year, the girls lived together in a house and put into practice all the skills they had learned in class. But, as the author pointed out, the girls shared the workload together, which may have given them unrealistic ideas about the labor of managing their own households. In our last evaluation of memes, we talked about how convenience foods in the 1950s and '60s were in part adopted quickly in reaction to a reduction in available household labor. With no servants/hired help and fewer children, alongside changing expectations of childhood, more and more women were shouldering the burden of household labor alone. Which is why Golden Girls is so refreshing: four adults pulling together relatively equally to maintain a household and keep everyone fed. There are occasional hints at people's economic statuses. For one, if any of them were independently wealthy, I doubt they'd need roommates. But while Blanche having a nanny for her children becomes a plot point, as does Rose keeping a secret that her husband was terrible with money, Dorothy and Sophia seem chronically on a budget, unable to afford some of the things the others can. Although that may just reflect Sophia's addiction to the races. But still, everyone is able to afford a rather shocking amount of eveningwear and certainly there's always enough money to keep the fridge stocked with cheesecake. The women are all in their 50s and 60s in the show (Sophia purportedly in her 80s, although Estelle Getty was a year younger than Bea Arthur), which means that they were in high school in the 1940s or earlier. In particular, Rose mentions her dismay at being rejected for joining the WACs during WWII. That means they all likely had at least some home economics training in school. And while the show is quintessentially '80s, there are hints of the 1940s and '50s everywhere, from the décor to the clothing (especially the robes). That home economics training likely served them in good stead when living with other women. They probably all had similar experiences, maybe learned how to wash dishes or make beds or do laundry a certain way. Because despite the fact that the characters come from very different backgrounds, they celebrate their differences, instead of letting them divide them (for the most, part, anyway). Today, more and more Millennials, cash-strapped by an economy that underpays them and bogged down with student loan debt they were promised would get them good jobs, are joining forces to purchase or rent homes with fellow adults they aren't married to. And as my generation contemplates retirement, many of us have thought about purchasing homes or property in concert with friends (Boomers and Gen-Xers are, too). The family/friend "compound" is becoming more and more of a thing. Communal living certainly has a lot of historical precedence. The nuclear family is a lot newer (and less effective) than most "traditional family values" folks like to admit. Which features prominently in several Golden Girls plots as the ladies struggle with deadbeat exes, estranged children and siblings, and the sting of sexism and ageism. And while home ownership is still the American Dream for many people, it makes a lot of economic sense to share household resources and labor. In this housing market? Sometimes it's the only way people can afford a place of their own. Even in the 1980s, Miami was expensive, so roommates made as much sense then as it does in most cities now. But what makes the Golden Girls TV show work is the relationships the ladies build with each other, how they support each other, and how they work together. In our modern era, it's a lot harder to find community than it once was. So if you want something similar in your life or your future, tell any naysayers, "Hey! It worked for the Golden Girls!" Just don't forget to hash out your differences with honesty and lots of late-night snacks. The Food Historian blog is supported by patrons on Patreon! Patrons help keep blog posts like this one free and available to the public. Join us for awesome members-only content like free digitized cookbooks from my personal collection, e-newsletter, and even snail mail from time to time! Don't like Patreon? Leave a tip!

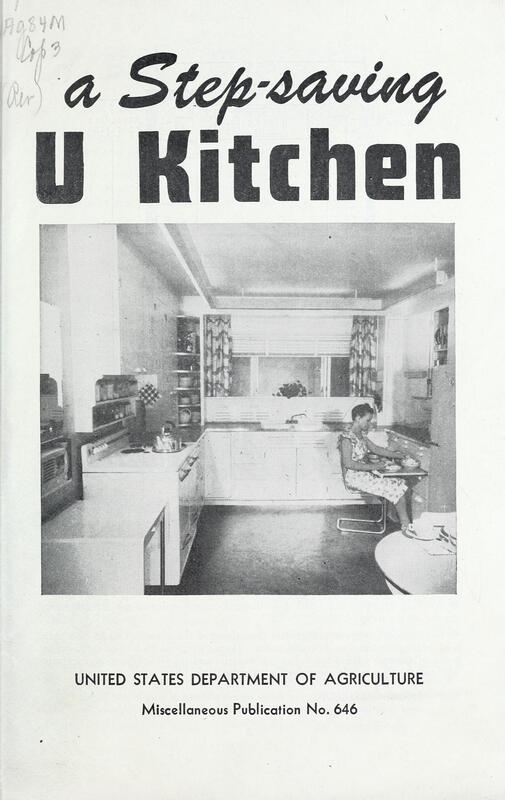

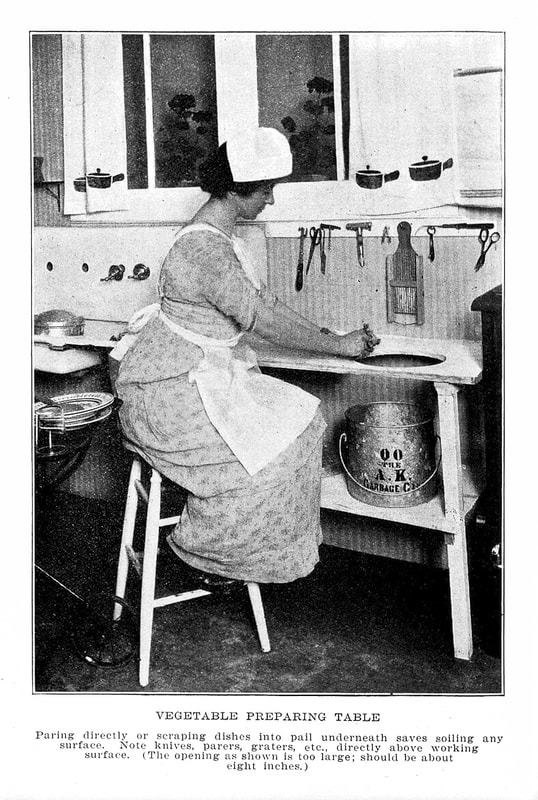

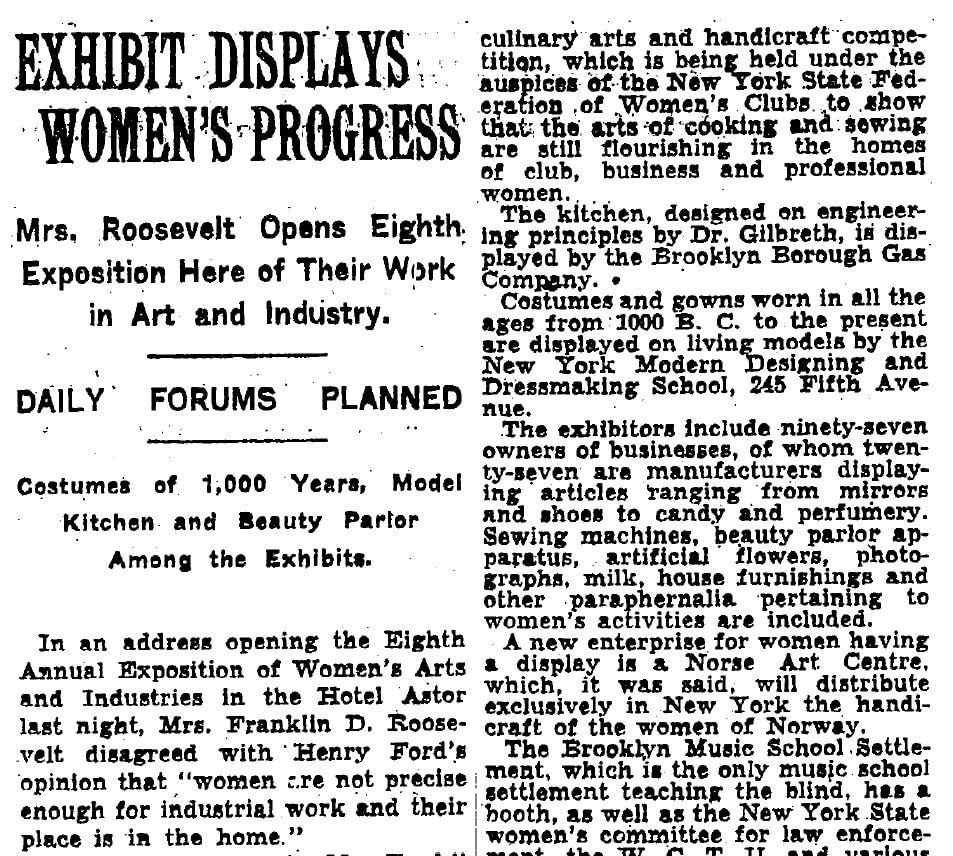

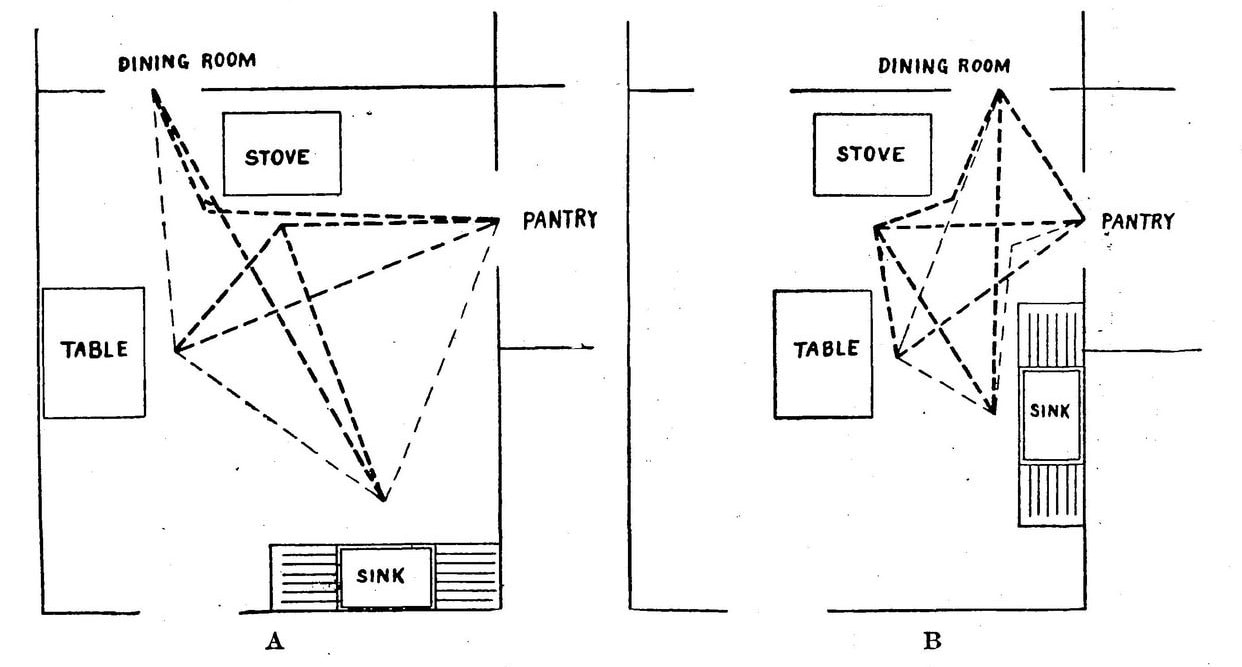

The other night I introduced a friend to one of my favorite YouTube videos ever. It’s a 1949 film put out by the United States Department of Agriculture’s Home Economics. You can watch the whole thing below: I love this film for a variety of reasons, but the primary one is how incredibly FUNCTIONAL this kitchen is. Not everything is perfect. The “messaging center” is too close to the stove for me – too able to collect splatters and grease from cooking. And the table, while nice, I think would have been better served by a more efficient built-in breakfast nook. But everything else? I LOVE IT. The storage is incredible. Everything is built with thought to use and efficiency. From the cooking and cleaning activities to the storage. And while the cabinets aren’t the prettiest, keep in mind that the design is meant to be built by farmers and handy homeowners – not professional contractors. Learn more about the film and the pamphlet for the Step-Saving Kitchen. This kitchen design is the culmination of several decades of work studies. During the Progressive Era, American interest in science began to increase, and scientific theories were applied to everything from factories to households. The Efficiency Movement was part of this application of scientific principles to everyday life. Led by mechanical engineer Frederick Winslow Taylor, the movement posited that everyday life, from industry to government to households, were plagued by inefficiencies, which wasted time, energy, and money. It also influenced the ecological conservation movement, a reaction to overuse of natural resources, and President Teddy Roosevelt was a known proponent. The movement, which became known as “Taylorism,” was hugely influential and spurred Progressive Era trust in experts and authorities that continued until the 1960s. Nowhere was Taylorism probably more influential than in the home economics movement, which advocated for efficiency in everything from nutrition to childrearing to household design. And that was thanks in part to the work of Christine Frederick, who in 1912 took Taylor’s principles and applied them to the household with a series of articles on “New Housekeeping” she wrote for the Ladies’ Home Journal. She started a Taylor-style efficiency laboratory in her own home kitchen and went on to publish several more books on the subject, including the 1919 Household Engineering: Scientific Management in the Home. Another influential advocate of household efficiency was psychologist Lillian Gilbreth. With her husband Frank Gilbreth, the two created a partnership to take Taylor’s ideas and apply them to industrial spaces, developing time-and-motion studies. Today, you might know them best as the parents who starred in the book (and subsequent films) Cheaper by the Dozen. After Frank’s untimely death in 1924, Lillian encountered discrimination in the engineering field, and began to turn her talents toward the domestic sphere. Partnering with Mary E. Dillon, president of the Brooklyn Borough Gas Company (and the first female utility president in America), Gilbreth and Dillon developed the kitchen work triangle, which advocated for a step-saving triangle between sink, stove, and refrigerator. Part of Gilbreth’s Practical Kitchen, the new design was revealed at the Eighth Annual Exposition of Women’s Arts and Industries on October 1, 1929. Eleanor Roosevelt was one of the speakers. Many of these principles were adopted by government organizations like the USDA. As early as the 1909, with the federal government’s Country Life studies, the plight of farm women and their poorly designed, technology-lacking kitchens came to light. The USDA’s Farmer’s Bulletin No. 607, “The Farm Kitchen as Workshop,” published in 1921 by Anna Barrows, outlined some of the concerns about kitchen efficiency and how to correct them. Page 10 of the bulletin illustrated the difference in closing the distances between workspaces – a star shape similar to the kitchen work triangle resulted. Several Congressional Acts brought federal funding to these studies. The Smith-Lever Act of 1914 mandated home economics instruction at land grant colleges. The Purnell Act of 1925 allocated federal funding into vitamin research and research of rural home management. These types of studies flourished under the federal funding and in my opinion placed overdue emphasis on the safety, sanitation, comfort, and efficiency of the home. All of these efficiency studies contributed to the result of the 1949 kitchen I love so much. But what happened? Why do modern kitchens seem to ignore the best research of the past? Today, there is far less government investment in domestic study – either from the USDA or public universities. The USDA’s Bureau of Home Economics was shuttered in 1962. Some of its personnel were shifted to the Nutrition and Consumer-Use Research department under the auspices of the USDA’s Agricultural Research Service. Some consumer-based research regarding food was absorbed by the FDA. But the kitchen research seems to have largely been abandoned. Some universities, like at Cornell, have continued to offer household design programs as subsets of architectural programs. But the federal funding is gone. Which is a shame, because our household lives seem to have suffered for it. One rule that has been adopted most widely is the kitchen work triangle. But not always. For instance, my kitchen doesn’t have one – the refrigerator, stove, and sink are all in a line. The only triangle is that my primary work surface is on the other side of my galley kitchen. And don’t even get me started on the ergonomics of storage. Those seem to have been discarded wholesale. One ray of light has been the resurgence of roll-out shelves. But even these are few and far between, likely because they are more expensive than traditional fixed shelving. And yes, dear reader, here, I think, is the rub – efficient kitchens must be custom designed. And in our cookie-cutter, prefab world, both design and customization are expensive. In addition, many of today’s kitchens are designed more for show, or occasional entertaining, rather than daily life. Which is an unfortunate reflection of how many Americans cook (or don’t). Case in point: the disappearance of the pantry – the one final thing that 1949 kitchen doesn’t have (it’s presumably in the cellar in the film) that I’d want. At any rate, if I ever win the lottery, you know what kind of kitchen I’ll be building. What aspects of the 1949 Step-Saving Kitchen did you like best? What would your dream kitchen look like? Sources & Further Reading

The Food Historian blog is supported by patrons on Patreon! Join us for awesome members-only content like free digitized cookbooks from my personal collection, e-newsletter, and even snail mail from time to time!

Many thanks to the Southeastern New York Library Resources Council for hosting my talk and for recording it! Much (but certainly not all!) of the research I've done for my book is presented in condensed form here. I think it turned out very nicely indeed and I am now contemplating recording more of my talks for sharing online. What do you think? Should I?

Here is some further reading based on some of the topics I discussed in the talk:

Capozzola, Christopher. Uncle Sam Wants You: World War I and the Making of the Modern Eighmey, Rae Katherine. Food Will Win the War: Minnesota Crops, Cooks, and Conservation during World War I. St. Paul, MN: Minnesota Historical Society Press, 2010. Gowdy-Wygant, Cecilia. Cultivating Victory: The Women's Land Army and the Victory Garden Movement. Pittsburgh, PA: University of Pittsburgh Press, 2013. Hall, Tom G. “Wilson and the Food Crisis: Agricultural Price Control during World War I.” Agricultural History 47, no. 1 (1973): 25-46. Hayden-Smith, Rose. Sowing the Seeds of Victory: American Gardening Programs of World War I. Jefferson, NC: McFarlan and Company, Inc., 2014. Veit, Helen Zoe. Modern Food, Moral Food: Self-Control, Science, and the Rise of Modern American Eating in the Early Twentieth Century. Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina Press, 2013. Weiss, Elaine F. Fruits of Victory: The Woman’s Land Army of America in the Great War. Washington, D.C: Potomac Books, 2008.

If you or your organization would like to host a talk - virtual or otherwise - please make a request!

This post was supported in part by Food Historian members and patrons! If you liked this post, please consider becoming a member or joining us on Patreon. Members and patrons get special perks like access to members-only content. In these days of stay at home orders, lots of folks are cooking at home more. And because we're supposed to grocery shop as infrequently as possible, lots of folks are also stocking up on food. So I thought this United States Department of Agriculture pamphlet (or possibly series of posters) from World War II on how to prevent food waste in storage and use would be fun and might include some bright ideas we can use again today. Published by the Home Economics Department of the USDA, these images are courtesy of the National Archives and Records Administration. Join the ranks - Fight Food Waste in the home

Like during the First World War, preventing food waste in WWII was a way to help keep food supplies freed up for soldiers and the Allies. In addition, canned foods could be scarce from time to time, and so Americans were growing and home canning their own more than ever. In particular, meat and dairy products were precious and sometimes difficult to get, even with ration points. Preventing food waste not only helped secure the food supply, it also saved money. By the 1940s, the majority of Americans had access to electricity and therefore electric refrigeration. But while refrigerator companies wasted no time touting not only the benefits of electric refrigeration, but also how to use fridges, sometimes old habits died hard. Storing dairy products at room temperature, for example. Other old-fashioned wisdom like on how to store fresh vegetables, was sometimes lost. So home economists like those at the USDA took it upon themselves to make sure all Americans had access to correct food safety information. Milk and Eggs - Nature's Food clean, covered, cold... will stay good!

If you're wondering why "clean milk" will only keep a few days in the fridge, it's likely that the milk being referred to in the pamphlet was raw and unpasteurized. You'll notice in the photograph that the woman is placing a glass bottle of milk in the fridge, and quite near the freezer compartment. The rest of the refrigerator is full of glass refrigerator dishes - designed to keep food "clean, covered, and cold." The baby is present to remind parents of the importance of keeping even dessert dishes cold and unspoiled. Meat, Poultry, Fish are full of flavor, a cold dry place is what they favor. The meat dish in refrigerator is an ideal place.

Here again the same woman is putting raw meat in the "meat drawer" of the refrigerator - located directly below the freezer compartment. It appears to be a metal drawer that slides out completely, presumably for ease of cleaning. Most delightful for me are the photographs of the root cellar (center) and spring house (right). Of course, the earth keeps things at a constant 54 degrees F, and spring houses often were full of constantly running water, which not only kept the building cool, but some foods could also be placed in the water to keep them even colder. This was a common way to keep foods cool before electric refrigeration. Hung in the well or sunk in a running stream, the water would leach heat away from the foods and keep them cool. Cooked Meat, Poultry, and Fish

Cooling hot foods quickly before refrigeration is still recommended by health department professionals. Most botulism cases come not from poorly canned foods, but from foods left over overnight or for several days and being reheated and consumed. Save Every Drop of Oil or Fat

Of course during the war, waste fats were saved for munitions manufacturing. But here was have answered the age-old question as to whether or not you should store your bacon grease in a coffee can at room temperature like grandma used to - don't! I recommend a glass container (canning jars are nice) in the fridge or freezer. It lasts forever there, the glass container won't rust, and is easy to clean. Wilt Not, Waste Not.... Fresh Vegetables

I am extremely tempted now to store my celery not in the crisper drawer, but in a jar of water! Of course, finding a place for it to stand upright is difficult... However, you can store cut celery in water - it will become extremely crisp. Fresh corn, garden peas, and young fresh lima beans all convert sugars to starches quite quickly after being picked. Keeping them in their pods helps prevent them from drying out. Fresh Fruits Are Best In Season with care... they'll keep within reason.

If you've ever taken a container of raspberries from the fridge with dismay to see them growing mold, perhaps it would be best to follow this advice. Certainly don't wash berries until just before use. But my goodness - I wish I had the sort of fruit rack pictured above - pears are the hardest by far to keep from spoiling or ripening too quickly. A Cool Airy Place to Suit Hardy Vegetables and Fruit.

I like this wooden storage rack as well, apparently made from wooden fruit crates. Apples and citrus up top, a large cabbage and perhaps onions (with covering) on the second rack, and potatoes, covered to keep from sprouting and turning green, on the bottom. One lament of mine is that modern kitchens almost NEVER have good storage for vegetables like this. To Keep bread, Cake, and Cookies Nice, protect from insects, mold, and mice.

Do you have a bread box? My mother-in-law does, and my parents' house has a built-in bread drawer in the kitchen - made of metal. I do not have a bread box, largely because we keep things in plastic these days and thus don't need the close quarters of the wooden or metal box to keep bread wrapped in paper from drying out. But definitely in July and August I keep my favorite cracked wheat sliced bread in the fridge, otherwise it does mold quite quickly. Sugar - Flour - Cereal - Spice

I am proudest, perhaps, of my baking cupboard, in which almost everything is stored in lovely, air tight glass jars. The brown sugar is never hard, the flour stays fresh, and the dried fruit don't get TOO dry. Storing things in air-tight containers also prevents an infestation of Indian meal moths, which I had the misfortune of dealing with precisely once before I started storing everything in glass. I think they came in with a batch of bulk peanuts in the shell. Of course, they get their name from "Indian meal" - a.k.a cornmeal. They also keep out mice and other insects, although thankfully I have never experienced weevils. The few home-canned foods I have on hand (and homemade booze), I keep in cupboards so they stay in the dark. I have heard of the mysterious and delightful-sounding kitchen accoutrement called a "fruit room" - a cool, dry, dark place perfect for storing not only fresh fruit but canned goods. My dream home has one, along with a butler's pantry. How do you store foods in your home? Do you have a fancy pantry? Or do you make do with kitchen cupboards and a metal rack, like I do? If you liked this post, please consider becoming a member or joining us on Patreon. Members and patrons get special perks like access to members-only content.

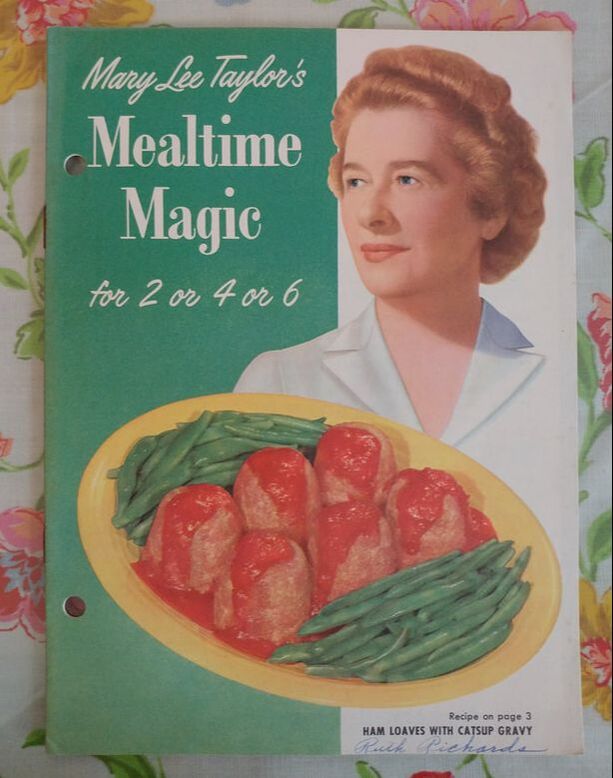

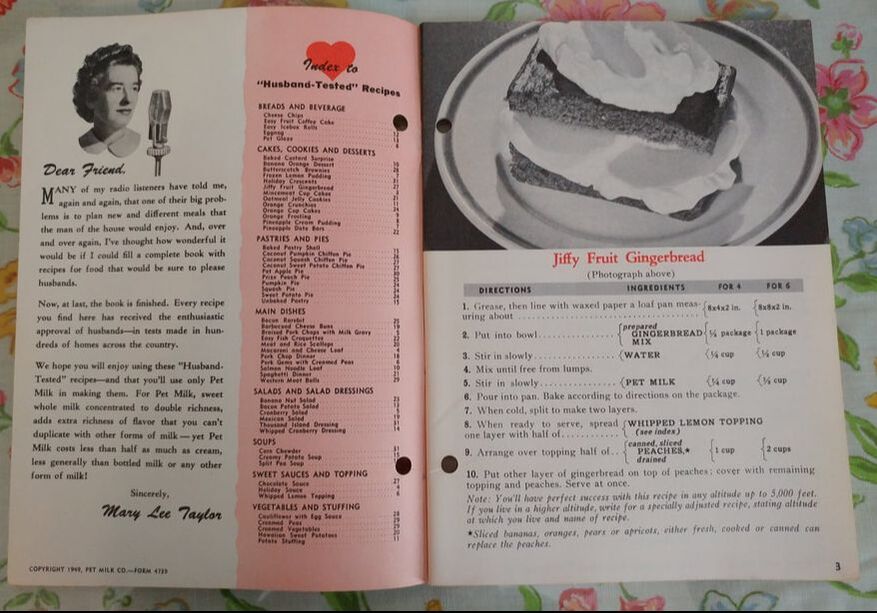

One of the wonderful things about being a food historian is not only tracking down and finding wonderful historic and vintage cookbooks for my personal collection, but people also give me vintage cookbooks! This was part of one such gift: a rather large selection of Mary Lee Taylor PET cookbooklets. For those of you not familiar with it, PET is a brand of evaporated milk. First produced in Illinois in the 1880s, PET milk made a name for itself supplying soldiers during the Spanish American War and again in World War I. But following the war, production ratcheted down, and PET was known to be in trouble.

The 1920s and '30s were a time of advertising innovation and one woman stood out amongst the crowd. Erma Perham Proetz was born in Denver, Coloradio in 1891. After graduating from Washington University and marrying Dr. Arthur Proetz, the couple settled in Saint Louis, MO, where Erma started working in the advertising business, as a copy editor for the Gardner Advertising Company. In 1923 she was assigned to the PET Milk Company account. The company had been foundering after World War I. In 1924 she won the Harvard Advertising Award for distinguished individual advertisements, with its accompanying $1,000 award. In 1925 she took the award again, this time for the best use of both text AND illustration for the PET milk campaign. In 1927 she received the $2,000 Edward W. Bok prize by the Harvard Award Jury for the best planned and executed national advertising campaign for a single product - PET milk. She was the first person to ever win the Harvard Advertising Award three times. In 1930, she was made a director of the Gardner Advertising Company - just seven years after starting as a lowly copy editor.

Erma's true brilliance, however, was the idea of Mary Lee Taylor.

Mary Lee Taylor was a pseudonym for Erma (although whether or not they were one and the same is debated). Although Erma remained at the Gardner Advertising Company and eventually became an executive, she wrote for/as Mary Lee Taylor for the rest of her career. Taylor embodied the kind, chatty, experienced home economists that housewives had come to trust by the late 1920s. Combining all of the best advertising opportunities at the time, Erma put Mary Lee Taylor to work in print, including newspapers, magazines, and cookbooklets. Dozens of Mary Lee Taylor cookbooklets were published over the years, and I am lucky enough to have a good chunk of them.

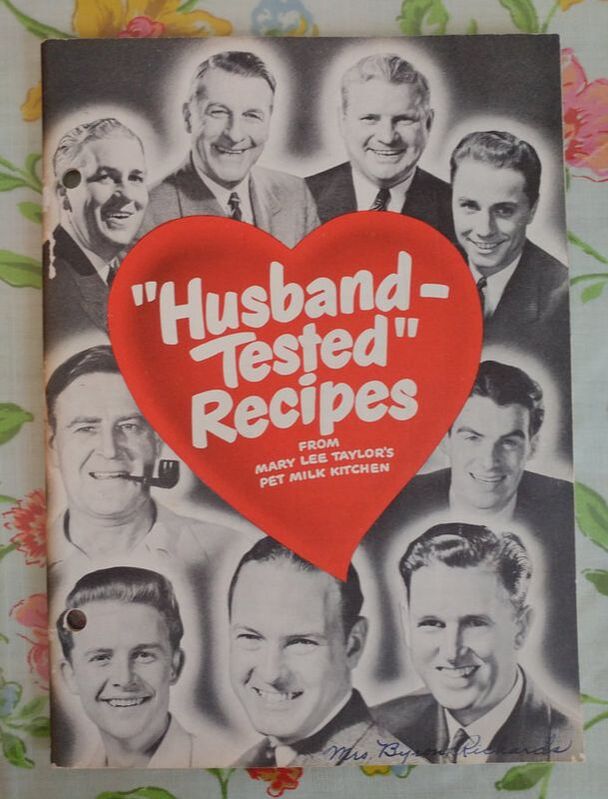

Unfortunately, particularly with the summer themed ones, there is a fair amount of recipe repetition. And, of course, every single recipe uses PET evaporated milk! But there are some particularly fun favorites, including "'Husband-Tested' Recipes."

But as you can see from her little "Dear Friend" letter above, Mary Lee Taylor was probably best known for her radio show.

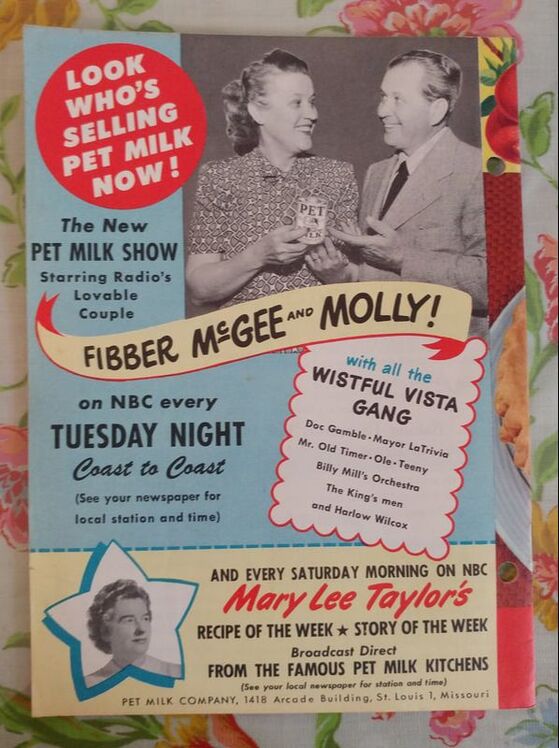

In the 1920s radio was still a fairly new medium, but mass production made radio sets more accessible to a wide range of Americans. It was a popular way for companies to advertise and product placement and corporate-sponsored shows soon became commonplace. Begun in 1933, the Mary Lee Taylor Show first aired on CBS and was one of the longest running cooking shows ever, ending in 1954. On CBS the show was just 15 minutes long, and featured a weekly recipe from Proetz as well as household tips, all using PET milk.

Erma was a member and leader of many women's and advertising groups, including the Women's Advertising Club of St. Louis, the St. Louis Branch of the Fashion Group, and the Council of Women's Clubs of the Advertising Federation of America. In 1935, Fortune Magazine named her one of 16 Outstanding Women in Business. In 1938, she attended the 34th annual convention of the Advertising Federation of America in Detroit, MI. An Associated Press article quoted her in a discussion about women in advertising. They wrote, "Ms. Erma Perham Proetz of St. Louis, a member of the Federation board, advised women hoping to enter advertising to take a home economics course, and to obtain some training in writing. 'The field is limitless,' she said."

And for Erma, it was limitless. She died on August 7, 1944 "after a long illness," and although her obituary is quite short, she had been executive vice president of the Gardner Advertising Company at the time of her death. That same year, the St. Louis Fashion Group, of which she had been regional director, announced the establishment of an Erma Proetz Memorial Scholarship at her alma mater - the Washington University School of Fine Arts "in recognition of her great interest in students and the wide help and encouragement she gave many young girls starting out on their careers."

In 1945, the Women’s Advertising Club of St. Louis established an annual Erma Proetz Award for the most outstanding creative work done by women in advertising. This award was dedicated Erma's memory as she "stood for the highest standards of advertising and whose faith in the ability of women in advertising was well known throughout the country."

In 1948 the Mary Lee Taylor Show moved to NBC, known as "Mary Lee on NBC" and was expanded to 30 minutes, with a serial drama between "Sally and Jim," a young couple. The show ended with the long-running recipe of the week and the creative addition of "Today's Recipe for Happiness," which included warm wisdom about family and life from Mary Lee herself.

Although Mary Lee Taylor did survive Erma by several years, but she couldn't quite make the transition from radio to the new medium of television. In 1954, Mary Lee Taylor went off the air. Despite that fact, Mary Lee Taylor and Erma Perham Proetz both left a lasting legacy. In 1952, Erma was posthumously inducted into the Advertising Hall of Fame - one of only a very few women to ever receive that honor. And Mary Lee Taylor lives on in the remaining radio shows and cookbooklets that people like me love to collect.

If you'd like to listen to more of the surviving Mary Lee Taylor radio shows, you can do so, thanks to the kind people of the Old Time Radio Researcher's Group on the Internet Archive. Listen to the Mary Lee Taylor Show now.

Bibliography

Erma's Advertising Hall of Fame listing.

Washington University Archives and an online exhibit 6 Copywriting Takeaways From a Real Life Mad Woman "Advertising Prize Won By D.C. Man," Evening Star, February 23, 1926. "Advertising Men Open Convention," Evening Star, June 13, 1938. "Mrs. Erma P. Proetz Dies; Advertising Executive," Evening Star, August 8, 1944.

And, as always, if you liked this post, consider becoming a member or joining us on Patreon. Members and patrons get special perks like access to members-only content.

|

AuthorSarah Wassberg Johnson has an MA in Public History from the University at Albany and studies early 20th century food history. Archives

July 2024

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed