|

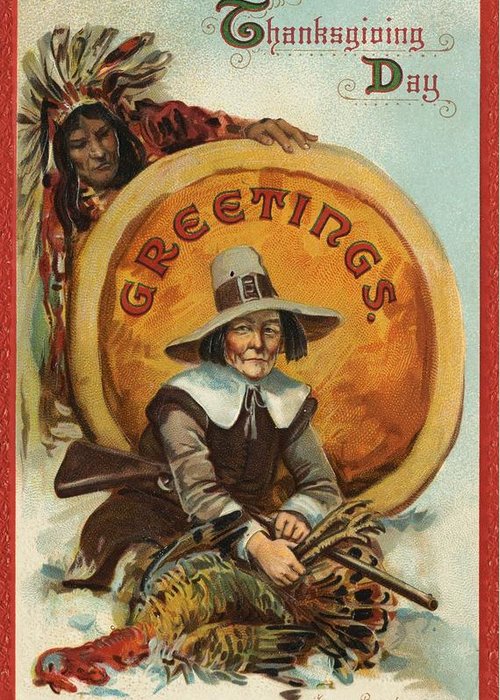

This month has been all about pumpkins and Thanksgiving, chez Food Historian. I have done my "As American as Pumpkin Pie" talk several times in the last few weeks. If you missed it, you can catch a recording, and the recipe for Lydia Maria Child's 1832 Pumpkin Pie here. I've also been doing a lot of media interviews about Thanksgiving, including for National Geographic and USA Today. And of course, my goal is always to try to debunk the mythology of the 19th century concept of Thanksgiving, which is rooted, wittingly or not, in white supremacy, Christian supremacy, and the supremacy of New England culture. Food historian Andrew F. Smith in the Association for the Study of Food and Culture Facebook page posted earlier this week about Thanksgiving. He writes: Sorry to report that the "Pilgrims" had nothing to do with Thanksgiving; it's all a made up story. Days of thanksgiving were frequently celebrated in colonial America– particularly in New England. These thanksgivings were usually declared in response to local events, such as surviving a long trip, military victories, good harvests, or providential rainfalls. These were solemn religious occasions spent in prayer, and little evidence has surfaced suggesting that a formal meal was part of the thanksgiving observance: only two records mention food, and they’re unusual. Thanksgiving dinners were well established by the American War for Independence (1776-1783). To celebrate the victory at Saratoga in 1777, the Continental Congress declared a day of thanksgiving. Joseph Plumb Martin, a soldier, noted in his journal that for this celebration, “Each man was given half a gill of rice and a tablespoonful of vinegar.” More sumptuous fare appeared in 1779 descriptions of thanksgiving meals. In one, a goose was served; in the other, venison, goose and pigeons were served along with a plethora of side dishes and deserts. In New England, the thanksgiving dinner became particularly significant event by the late eighteenth century. A participant in a 1784 thanksgiving meal in Norwich, Connecticut, proclaimed: “What a sight of pigs and geese and turkeys and fowls and sheep must be slaughtered to gratify the voraciousness of a single day.” William Bentley, the pastor of the East Church in Salem, Massachusetts, reported in 1806, that, “A Thanksgiving is not complete without a turkey. It is rare to find any other dishes but such as turkies & fowls afford before the pastry on such days & puddings are much less used than formerly.” Bentley’s description suggests that a two-course meal —the first consisting of turkey and perhaps other meat dishes, and the second, of dessert. This pattern was common during the early nineteenth century and these traditions were long maintained. The first association between the Pilgrims and thanksgiving appeared in 1841, when Alexander Young published a copy of a letter written by Edward Winslow, dated December 11, 1621, to a friend in England. It described a three-day fall event, the dates of which were not cited. In this letter, Winslow writes: Our harvest being gotten in, our Governor sent four men on fowling, that so we might after a more special manner re[j]oice together, after we had gathered the fruit of our labours. They four in one day k[i]lled as much fowl as, with a little help besides, served the Company almost a week. At which time, amongst other recreations, we exercised our arms, many of the Indians coming amongst us, and amongst the rest their greatest king, Massasoit with some 90 men, whom for three days we entertained and feasted. And they went out and killed five deer which they brought to the plantation and bestowed on our Governor and upon the Captain and others. You will note that there is NO statement that this was a “thanksgiving.” In a footnote to the 1841 reprint of the letter, Alexander Young claimed that the event described by Winslow “was the first thanksgiving, the harvest festival of New England. On this occasion they no doubt feasted on the wild turkey as well as venison.” However, Winslow did not use the word thanksgiving to describe this or any other event in the fall of 1621. The Puritans made no subsequent mention of this event and it was not remembered or observed in later years by the Pilgrims or Puritans. The feast described by Winslow makes no mention of prayer and it does include many secular elements: the Puritans would not have considered this a thanksgiving. However, the idea that the 1621 event at Plimoth Plantation was the “First Thanksgiving” was picked up by others, and by the mid-nineteenth century it was generally believed in New England that the Pilgrims had invented thanksgiving in America. Of course, Jamestown, settled in 1607, observed many days of thanksgiving years before the Pilgrims landed at Plimoth Plantation, and a plaque in Jamestown marks the purported site of the real “First Thanksgiving,” but factual knowledge was unable to stop the fakelore of the Pilgrim connection with thanksgiving from spreading. The driving force behind making thanksgiving a national holiday in the United States was Sarah Josepha Hale, the editor of Godey’s Lady’s Book. Hale commenced her campaign to create a national thanksgiving holiday in 1846. For the next seventeen years, she wrote annually to members of Congress, prominent individuals, and the governors of every state and territory, requesting each to proclaim a common thanksgiving day. In an age before word processors, typewriters, or mass media, this was a difficult campaign to wage. Hale believed that a thanksgiving holiday would help bind the United States together. She came close to success in 1859 when thirty states and three territories observed thanksgiving on the third Thursday of November. During the Civil War, she was unable to communicate with many Southern states, so rather then request each state, she approach President Lincoln, asking for thanksgiving to be designated a national holiday. A few months after the North’s military victories at Gettysburg and Vicksburg in 1863, Hale achieved success: Lincoln declared the last Thursday in November a national day of thanksgiving, and the holiday has been celebrate ever since in the United States. Smith outlines a good argument. Days of thanksgiving were common throughout early American history, could be declared at any time of year, and were usually not associated with feasting. When they were, it was often after the fall harvest, as the "original" 1621 version. Harvest feasts are very English, so it makes sense that the Separatists (what the Pilgrims were actually called) would celebrate a successful harvest after so devastating a winter with a feast. Harvest Home, or Ingathering, is an ancient tradition in the British Isles. It also makes sense that traditionally British foodways, such as eating sour fruits with wild game birds (turkey and cranberry sauce, anyone?), pies, gravy, and mashed root vegetables, would make their way onto New England harvest dinner tables. But days of thanksgiving were also declared for far darker reasons, including the "victory" in May, 1637 known today as the Pequot Massacre. The idea that our modern Thanksgiving stems from the celebration of that massacre is making the rounds of the internet lately, and while the connection is not direct, it's not as indirect as Snopes makes it out to be. Although, as Smith notes, Sarah Josepha Hale was the driving force behind our modern celebrations, whatever her intentions, the subtext of a distinctly British, New England tradition being sanctified by national authority to be celebrated throughout the land definitely fit with the driving cultural force of the 19th century - that White, Protestant, Yankee/English culture was superior to all others. It's no surprise that Thanksgiving finally became a national holiday in 1863 - the midst of the American Civil War. It's also no surprise that the mythology of the peaceful, helpful Indians was becoming part of our national conversation just as millions of Indigenous people were being forcibly removed from their lands and treaties violated right and left by the federal government notably during the "Plains Wars" of the mid and late 19th century. The Great Plains were some of the last areas of the United States to be colonized by Europeans, and so their Indigenous peoples were some of the last to be forcibly removed. It's also why most portrayals of Indians in Thanksgiving imagery depict them in the garb of Northern Plains Indians, which is substantially different from how Native peoples in the Northeast dressed historically.  This c. 1920 postcard is a classic example of how Thanksgiving mythology is perpetuated. A "Pilgrim" (They didn't dress like that either) sits with his gun over a freshly killed turkey. In the background, a giant pumpkin pie halos him. Behind the pumpkin, lurks a Native man dressed in Plains Indian clothing, his intentions unknown. By framing Indigenous people as complicit in their own destruction, Europeans could justify land theft (they weren't "using" it anyway!), genocide ("Kill the Indian, save the man"), and breaking countless treaties that legally have the same standing as the Constitution (you can't stop progress!). This is also why, for many Indigenous people, Thanksgiving is a day of mourning. A lot of people still celebrate Thanksgiving, and since the holiday in the modern era is much more focused on food and family, I think that's a good thing. However, it's important to understand what Thanksgiving myths are out there and why and to not perpetuated them. And it's equally important to support Indigenous people - emotionally, politically, and financially - as we celebrate. If you want to decolonize your Thanksgiving by educating yourself further, check out last year's post with a list of resources. The amazing film Gather is now available on Netflix and is fantastic. It would make a wonderful post-Thanksgiving-dinner watch with friends and family. Taking tangible actions is also important. You can support Indigenous food producers as you plan meals all year round, not just at Thanksgiving. You can support Indigenous people in their efforts to prevent oil and natural gas pipelines from violating treaties and polluting or utterly destroying the last vestiges of important ecological landscapes (which, newsflash, helps the whole planet). You can support the land back movement, which focuses on returning public lands acquired through treaty violations back to Indigenous ownership and/or stewardship. Especially since Indigenous people are generally much better at managing public lands than state and federal organizations. You can donate to legal aid organizations that help Indigenous people and tribes protect their individual and collective rights. And finally, you can push back against stereotypes of Indigenous people and Thanksgiving alike. Like my friend whose kindergartener came home with a Thanksgiving worksheet featuring stereotypical depictions of Pilgrims and Indians, who sent her teacher this amazing resource put together by the Native American Services department of Oklahoma City Public Schools on how to interpret Thanksgiving for children in a way that does not erase Indigenous people or perpetuate harmful myths. American history is messy. And that scares a lot of people. But history is complicated, and by better understanding it, we can better understand how we got to where we are today, and whether or not we should do anything to change or fix it. So this Thanksgiving, don't buy the same old stories you grew up with. They're myths for a reason, and we can challenge those reasons, because they suck. And if you don't want to make a Thanksgiving meal that puts New England foodways on a pedestal, feel free to skip the turkey, cranberry sauce, mashed root vegetables, pumpkin pie, and anything else you don't like but always feel obligated to eat. Make your own traditions, and celebrate your own, local harvest season with foods that reflect your family and your geography, without the guilt. Throw off the tyranny of "tradition." Life's too short for bad meals and bad history. The Food Historian blog is supported by patrons on Patreon! Patrons help keep blog posts like this one free and available to the public. Join us for awesome members-only content like free digitized cookbooks from my personal collection, e-newsletter, and even snail mail from time to time! Don't like Patreon? Join with an annual membership below, or just leave a tip!

0 Comments

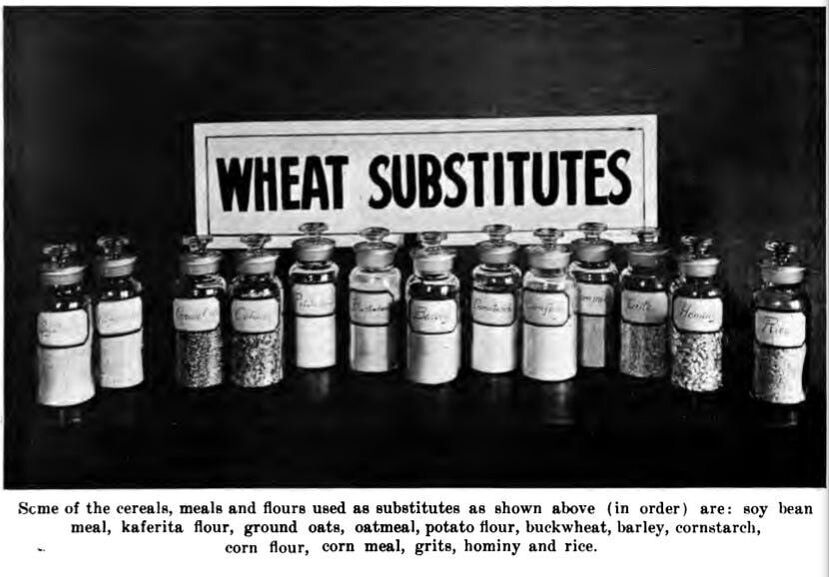

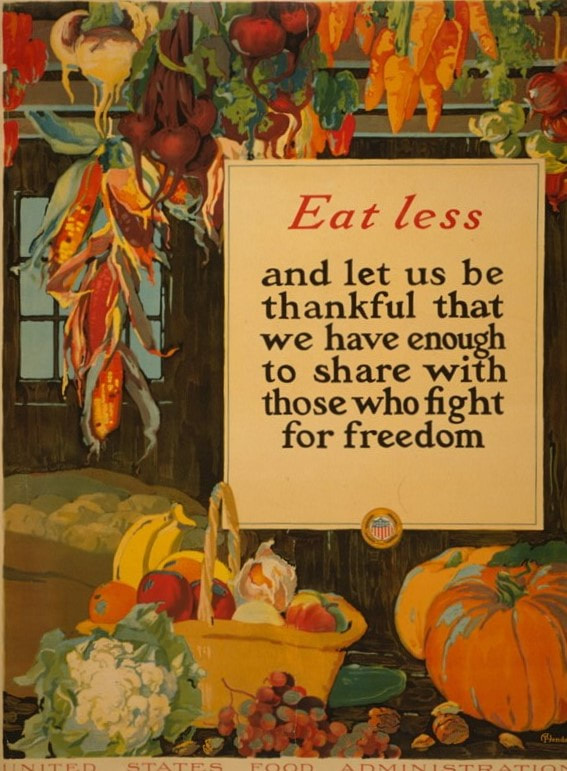

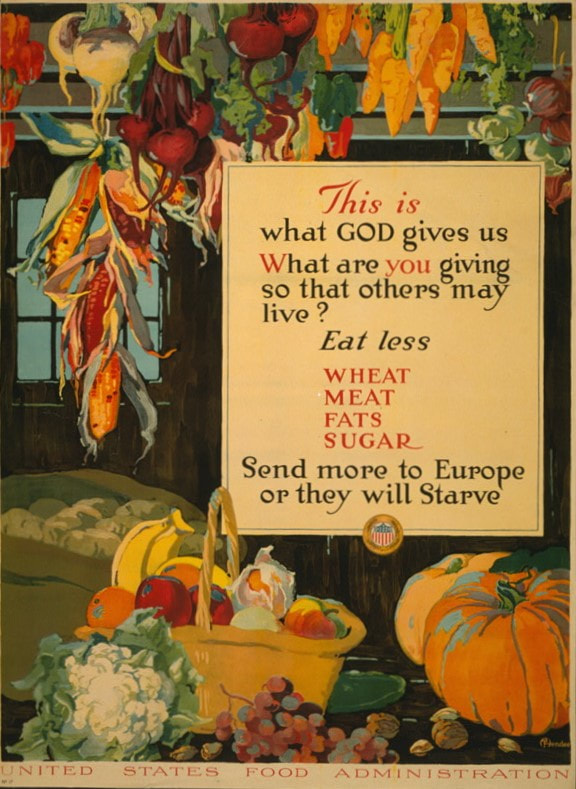

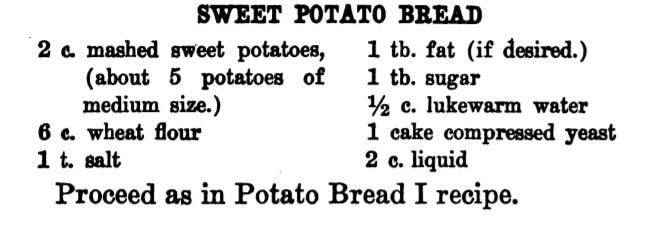

Tomorrow is Thanksgiving in the United States, so I thought it would be apt to visit the matching pair of posters. It's not clear if they were meant to be displayed together or not, but the artist, A. Hendee, clearly recycled one beautiful image for another version. In both images, produce is stored in an attic. Red peppers, turnips, corn, beets, carrots, and what looks like red onions hang from the rafters. A sack of potatoes, a basket of fruit (including bananas!), cauliflower, grapes, a lone cucumber, a few nuts, and two fat pumpkins sit on the wooden floor. In the first image, a white placard with the United States Food Administration seal on the bottom admonishes "Eat less, and let us be thankful that we have enough to share with those who fight for freedom." Much of the propaganda around food and the First World War admonished self-restraint when it came to food. Although the phrase "eat less" has had some controversy in the modern era, in the 1910s it was far less about ideal bodyweight (although that played a role) and far more about reducing waste. As the poor wheat harvests in 1916 and 1917 did not allow for normal consumption levels AND exporting to the Allies, most of the rhetoric in 1917 and 1918 was focused on reducing waste, refocusing American eating habits on other types of food, and reducing consumption in general. For instance, while messages of "eat less" were common, so was the Gospel of the Clean Plate, which exhorted Americans not to waste food. In the second poster, the message reads, "This is what God gives us - what are you giving so that others may live? Eat less wheat, meat, fats, sugar - send more to Europe or they will starve." The Library of Congress tentatively dates this poster as 1917, but that could be simply because it is WWI-related. However, this message is far more explicit than the first, so it may very well have been the first printed. We have specific foods to avoid, and the spectre of starvation in Europe is raised. But we also have a more explicit reference to the image itself, "This is what God gives us" is referencing the abundant produce. Which, you'll notice, does not include hams or bushels of wheat or other foods you might find in a 19th century attic. The focus is entirely on produce, which is on purpose, as eating more fruits and vegetables instead of more calorie-dense and shelf stable foods like wheat, meat, fats, and sugar. Potatoes in particular were touted as an alternative to bread. Although the Library of Congress has no other posters attributed to "A. Hendee," I've managed to track her - yes her! - down, thanks to a clue post from a UK museum that found her full maiden name. Alice Julia Hendee, later Alice Hendee Price, was born in 1889, possibly in Kansas as she attended the Kansas City Art Institute before moving to New York to attend the National Academy of Design and the New York School of Fine and Applied Arts. In 1917 she was listed in a city directory as living on the Upper West Side, and in 1923 she moved to Bronxville, NY in Westchester County. At some point she married architect and illustrator Chester A. Price. Alice made the local news quite frequently for her art, and by 1950 was teaching classes to area women. She died in Westchester county in 1969 and outlived her husband, but in typical mid-century fashion, not his name. Like many of the illustrators and artists who created iconic propaganda posters for the First World War, Alice Hendee Price's recorded history makes no mention of her wartime work. But the stunning images remain. And this Thanksgiving, although we no longer need to curtail our eating habits for wartime, the message of being thankful for what we have and sharing with others is a timeless one. Have a lovely Thanksgiving, everyone, whether you're celebrating with family or friends, and I hope you can enjoy all the bounty of the season. The Food Historian blog is supported by patrons on Patreon! Patrons help keep blog posts like this one free and available to the public. Join us for awesome members-only content like free digitized cookbooks from my personal collection, e-newsletter, and even snail mail from time to time! Don't like Patreon? Join with an annual membership below, or just leave a tip!  "Wheat Substitutes" as illustrated in "Liberty Recipes" (1918). Caption: "Some of the cereals, meals and flours used as substitutes as shown above (in order) are: soy bean meal, kaferita flour, ground oats, oatmeal, potato flour, buckwheat, barley, cornstarch, corn flour, corn meal, grits, hominy, and rice." Last time for World War Wednesday, we discussed how important it was during the First World War to save wheat and reduce bread consumption. During the war a number of cookbooks were published to help Americans reduce their consumption of wheat, meat, butter, and sugar and how to go without or reduce the use of scarce or expensive ingredients like eggs. When it came to bread, there were very few recipes that used no wheat flour at all, but instead most recipes used alternative grains like barley, rye, corn, and oatmeal or other ingredients like mashed potatoes or cooked rice to reduce the overall ratio of wheat flour used. Liberty Recipes was written by Amelia Doddridge, who the title page lists as "Formerly, Instructor of Cooking, Manual Training High School, Indianapolis, Indiana; and Emergency City Home Demonstration Agent, Wilmington, Delaware. Now, Head of Home Economics Department, Wooster College, Wooster, Ohio." The book was published by Stewart & Kidd Company in Cincinnati, Ohio in 1918. I wasn't able to find much more on Amelia herself. I found a dissertation that notes that several classes in food and household management at Wooster College were taught by Amelia, who was then Acting Dean of Women. But those classes were apparently only offered temporarily during the war, "These particular classes were offered only between 1918-1919 during the "confused period of war, fuel shortages, S.A.T.C., Spanish flu, and demobilization." Which seems to indicate that Amelia herself may not have survived as an instructor after the war. A reference from 1922 places an Amelia Dodderidge in Montevallo, Alabama as head of the home economics department "at Montevallo," which possibly meant the college located there. I found a reference to an Amelia Doddridge teaching high school home economics in Ohio in 1924. And another to an Amelia Dodderidge working at a Farm Bureau in Pennsylvania and/or as a county home economics representative, and/or as the Home Economics Extension representative from the state college, all in Pennsylvania, all in 1926. In 1929 there's a Miss Amelia Dodderidge in Modesto, California, acting as an "assistant home department agent." By the 1950s she appears to be living, retired, in Franklin, Indiana and throughout the late 1950s and 1960s there are numerous articles in the Franklin Star authored by Amelia Dodderidge. A 1962 article indicates she was working for the Methodist Home (likely a home for the elderly) in Franklin, IN and, indeed, most of the articles she published in the Franklin Star were called "The Home Window," apparently reporting on the activities and events of the Methodist Home. The trail runs cold at the very end of 1963. The last reference to Amelia is published on December, 31. It's unclear whether the newspaper simply did not run her column again or if the newspaper itself ceased publication or if it simply wasn't digitized past 1963. Although it's tough to prover all these Amelia Dodderidges were the same person, it is very likely. Amelia apparently continued her home economics work throughout her life, even after "retirement." But back to Liberty Recipes. The cookbook is a fascinating one, and I particularly love some of the slogans listed in the frontspiece; my two favorites are "Place meat and buns behind the guns" and "Husband your stuff; don't stuff your husband." Also interesting are the references in the foreword to the cookbook itself being much more convenient for reference by housewives rather than taking "too much trouble to hunt in a pile of leaflets for the recipes she wishes at the particular time she needs it" - a reference to the numerous bulletins and cookbooklets being published by the USDA and other government agencies. In addition, the foreword claims that although the recipes listed are designed for the "present emergency," "they should be usable and still practical even after the war clouds pass and Freedom is ours." There are numerous bread recipes in the cookbook - both yeast and quick breads. In addition, the cookbook focuses on meatless and meat-saving recipes, a few salads, and numerous sugarless, low-sugar, and wheat- and fat-saving dessert recipes. This recipe for Sweet Potato Bread seemed quite modern, and a fun recipe to share in the lead-up to Thanksgiving. Although I have not had time in a while to bake yeast bread, I thought I would share it anyway. Maybe I can take a stab over the holiday. World War I Sweet Potato Bread (1918)The original recipe makes references to other recipes, so I've combined the instructions for your convenience. A cake of yeast is about the same as dried yeast packets that are sold today. Although you can try it with RediRise or similar fast-acting yeast, I recommend plain ol' active dry yeast. 2 cups mashed sweet potatoes (about 5 potatoes of medium size.) 6 cups wheat flour 1 teaspoon salt 1 tablespoon fat (if desired.) 1 tablespoon sugar 1/2 cup lukewarm water 1 cake compressed yeast (or 1 envelope active dry yeast) 2 cups liquid Use the potato water for the liquid. Pour it gradually over the hot mashed potatoes. When lukewarm add the softened yeast, salt, sugar, and fat. Stir in the rest of the flour gradually. When the dough becomes too stiff to stir, work in the remainder of the flour by kneading with the hands. It may take a little more flour or a little less depending upon the kind of flour used. The dough should be of such a consistency that it will not stick to the hands or to the bowl. Knead 10 or 15 minutes until the dough is smooth and elastic. Place in a bowl, cover, and keep it in q warm temperature (75 to 85 F). When risen twice its bulk, cut down and knead again. Then shape into loaves, place in greased pans, and set in a warm place. When light and doubled in bulk it is ready to bake. To prevent a crust from forming over the top of the loaf while rising, rub the surface with a little melted fat. Watch the rising and put into the oven at the proper time. If risen too long, it will make a loaf full of holes; if not risen enough, it will make a heavy bread. Bake 45 minutes to 1 hour in a moderately hot oven (375 to 400 F). If oven is too hot, the crust will brown before the heat has reached the center of the loaf and will prevent further rising. The loaf should raise well during the first 15 minutes of baking; then it should begin to brown, and continue browning for the next 15 or 20 minutes. The last 15 to 30 minutes, it should finish baking and the heat may be reduced. When done, the bread will not cling to the sides of the pan. If a tender crust is desired, brush the bread over with a little melted fat as soon as it is taken from the oven. If you end up making this recipe, let us know in the comments how it turned out! There are lots of other interesting recipes to be had in Liberty Recipes, including a potato biscuit pie crust recipe, buckwheat spice cake, and cornmeal gingerbread, to name a few! Are there any recipes in there that you want to try? The Food Historian blog is supported by patrons on Patreon! Patrons help keep blog posts like this one free and available to the public. Join us for awesome members-only content like free digitized cookbooks from my personal collection, e-newsletter, and even snail mail from time to time! Don't like Patreon? Join with an annual membership below, or just leave a tip! |

AuthorSarah Wassberg Johnson has an MA in Public History from the University at Albany and studies early 20th century food history. Archives

July 2024

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed