|

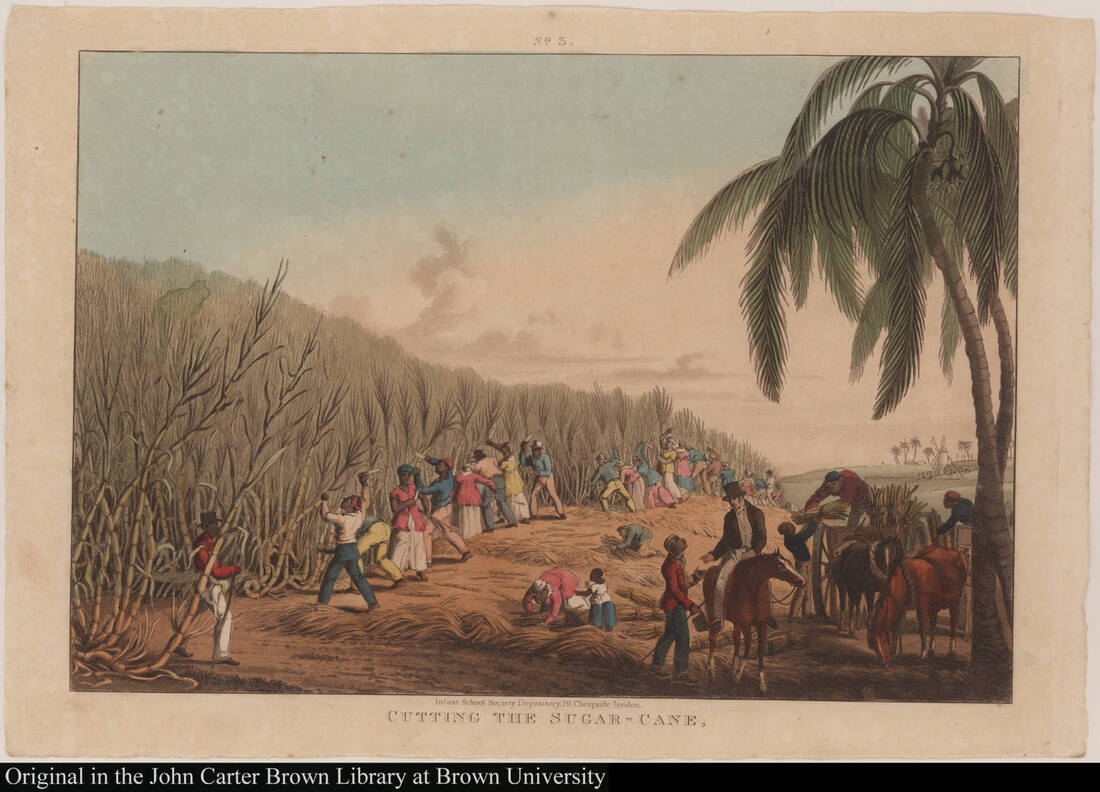

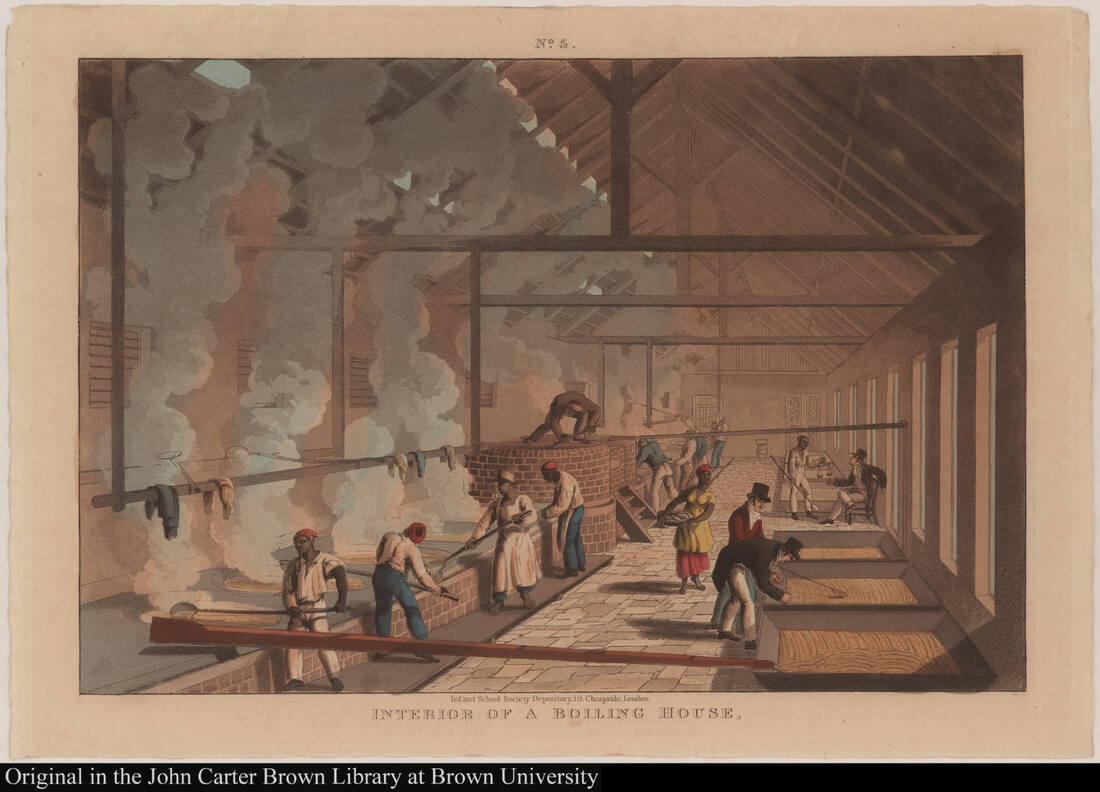

The United States owes enslaved people and their descendants a lot. White Americans don't like to admit that often, but we really do. And to me, nowhere is that more evident than in our modern food system. Today is Juneteenth - a celebration of the end of slavery in the United States. Not on the anniversary of the Emancipation Proclamation, which was issued on January 1, 1863 and which LEGALLY freed all enslaved people in the country. No, it took until June 19, 1865 - fully two and a half years later, for the message (and the enforcement) to finally arrive in Texas with a group of Union soldiers. For although all enslaved people in the United States were deemed free in 1863, the Confederacy did not recognize that authority, and continued to enslave and exploit Black people until forced to do otherwise by armed Federal troops. So to celebrate Juneteenth, you can certainly look up recipes and plan a party. But I think it's equally important to recognize incredible contributions enslaved people made to our food system, and for Americans of all backgrounds to reckon with the truth that much of our modern foods are the direct result of violence and exploitation. At last night's Food History Happy Hour, viewer Cathy brought up that we learn a lot in school about the contributions of White immigrants, but not so much about the contributions of enslaved people. And that struck me as both very true and very sad. Because so much of what is considered American food is intimately connected to both West Africa and the enslaved people brought here against their wills. People who experienced incredible hardship still had the perseverance and fortitude not only to hold on to their foodways on the horrific voyage across the Atlantic, but to persist in keeping those foodways in the United States. Not all of the foods listed below came from West Africa, but all are a direct result of the enslavement of West Africans. Editor's note: The Food Historian is an Amazon affiliate. Any purchases you make through the book links below will help support blog posts like this! SugarWe can start with the biggest one. Before the enslavement of Africans in the Caribbean and American South, sugar was produced in India at great expense. By kidnapping people and forcing them into bondage, enormous sugar plantations were established by Europeans throughout the Caribbean, and later in American states like Louisiana. Sugar plantations were some of the most brutal of the plantation economy. The life expectancy of an enslaved person was very low, and some islands imported double or triple their populations per year in slaves, as many died faster than they could be replaced. Today, sugar is almost completely mechanized, but most of our modern foodways - sugary desserts in particular - are possible only through the massive effort to enslave millions of people for profit. Throughout the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, sugar became increasingly affordable, as sugar production mechanized. The cultivation of sugarcane remained incredibly labor-intensive. Sugarcane harvesting, for example, was not really mechanized in the American South until World War II. As an aside, I recently learned that the United States was active in the slave trade for decades after it was made illegal, and that the primary point of destination for American slave traders after kidnapping mostly children from West Africa was the sugar plantations of Cuba. This illegal trade continued until the 1860s. Further Reading:

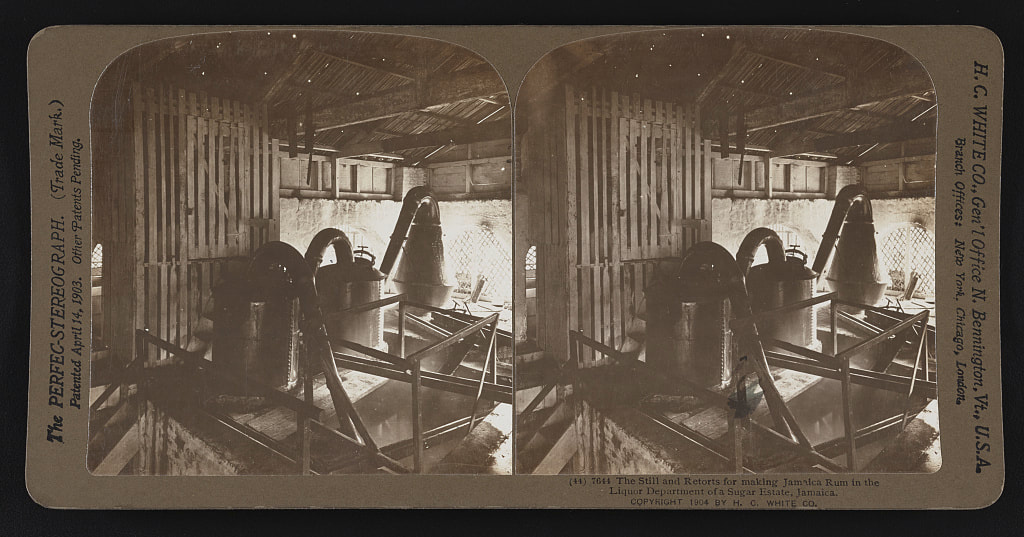

MolassesMolasses may make you think of baked beans, or gingerbread, or soft molasses cookies. But molasses is a byproduct of the sugar industry, and therefore slavery. Molasses, the cheapest sweetener, also was used in slave rations and was a major foodstuff among poor Whites throughout the United States until the mid-20th century. But although Molasses becomes intimately connected with New England and pioneer foodways, it has another important use... RumRum may make you think of pirates, but it was actually developed as a way to transform relatively worthless molasses into a high-value commodity. And while vicious pirates guzzled it by the gallon, it was also a huge economic engine not only in the Caribbean, but also in New England, where it was produced and used to purchase people and goods in West Africa as part of the slave trade. The irony being that a product largely produced by slaves (first in producing the molasses, and then often again in producing rum) was being used to purchase more slaves should not be lost on anyone. Further Reading:

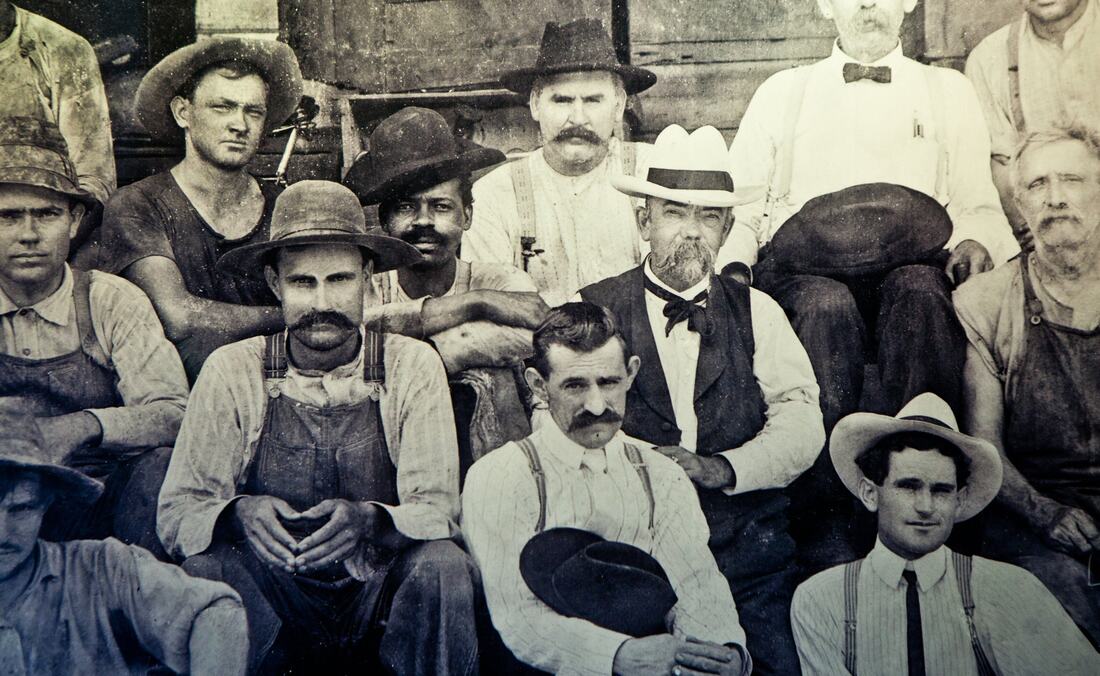

Jack Daniels WhiskyWhile we're on the topic of alcohol and slavery, let's just take a moment to recognize that Jack Daniels was taught how to make whisky by Nathan "Nearest" Green, an enslaved man who used a charcoal filtering technique he learned to clean water in West Africa to filter the distilled alcohol. He was Jack Daniel's first master distiller, but only got credit more recently. Read the full story. RiceI know what you're thinking - Sarah, how are you going to relate RICE to slavery? Well, although today we consume a lot of rice developed in India and Japan, throughout the 19th century, Carolina Gold rice was king. Rice production in South Carolina dates back to the 18th century and plantation owners specifically sought out and captured West Africans skilled in rice agriculture and enslaved them to operate their rice plantations. The White plantation owners got obscenely rich on this scheme. Although Carolina Gold rice is no longer as prevalent in American food culture, it still made a huge impact on the economy of the South. Further Reading:

OkraNative to Ethiopia and cultivated in Africa as early as 12,000 years ago, okra was brought to North America by enslaved West Africans, the seeds braided in their hair. It went on to spread throughout the American South, influencing such dishes as regional varieties of gumbo and often served stewed with tomatoes or breaded and fried. Although not as widespread as some of the other foods on this list, okra still maintains a huge impact on American foodways. Further Reading:

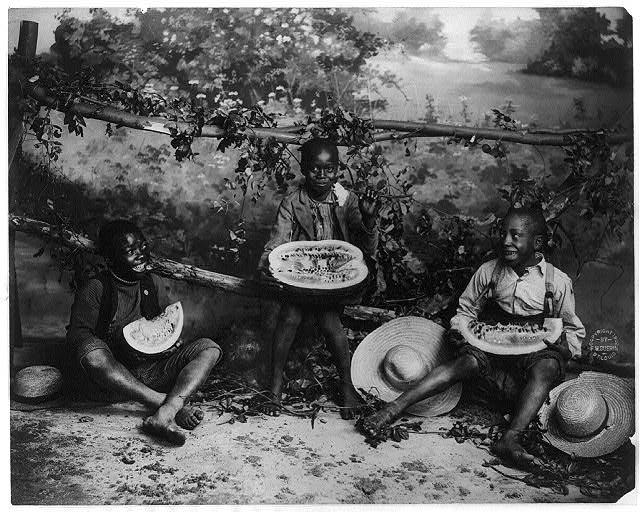

WatermelonDeveloped in the Kalahari desert of Africa, the watermelon was carefully bred by Indigenous Africans to go from a thick-rinded, rather tasteless melon to the sweet, juicy treat we know today. Although it did spread to Egypt and the Middle East, it was likely introduced to North America via the slave trade - either purchased by slave traders and kidnappers, or brought over by enslaved people themselves. The American stereotype of associating Black folks with watermelon as an insult is still around today. Further Reading:

Black Eyed PeasNative to West Africa, black eyed peas, sometimes called cowpeas, were brought to the Americas by enslaved Africans. In the U.S. they are most commonly known as the main ingredient in "Hoppin' John," a popular dish consumed on New Year's Day for good luck. Two stories about black eyed peas and luck have emerged over the years. The first is that when General Sherman made his way through Georgia, one of the only foods the Union Army did not take was black eyed peas, as they were considered cattle fodder in the North. The Confederate Army subsisted on this "slave food," an irony they clearly did not understand. The other story, and one I think far more likely, is that black eyed peas were one of the celebratory dishes consumed on January 1, 1863 - the day the Emancipation Proclamation became law. Further Reading:

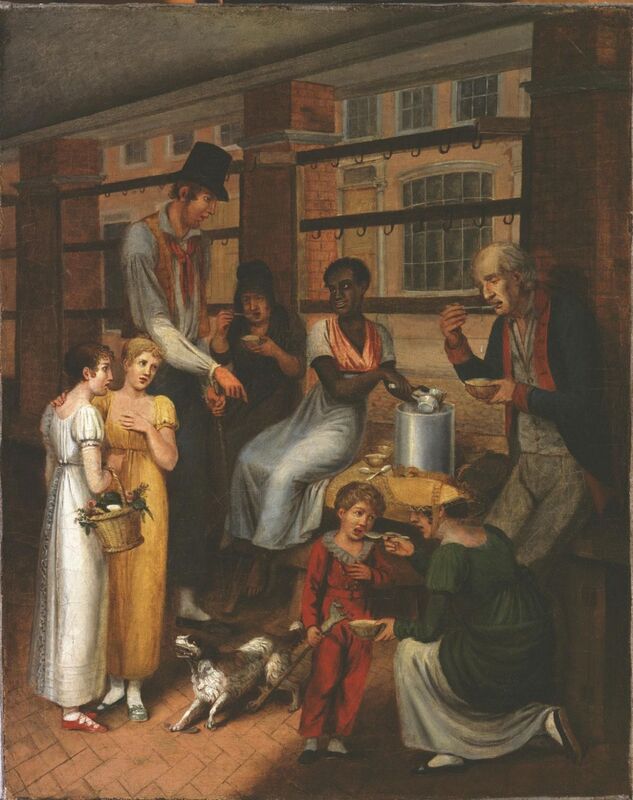

Philadelphia Pepper Pot SoupAccording to Tonya Hopkins, The Food Griot, Philadelphia Pepper Pot Soup, a favorite dish of George Washington, is quintessentially West African in style, including the addition of a whole hot pepper to flavor the soup. It was popularized as a street food in Philadelphia by Black women like the one pictured here. In the 20th century it was commercialized for a brief time by Campbell's, but its popularity waned by the late 20th century. Today, some chefs are reviving the food tradition. Further Listening:

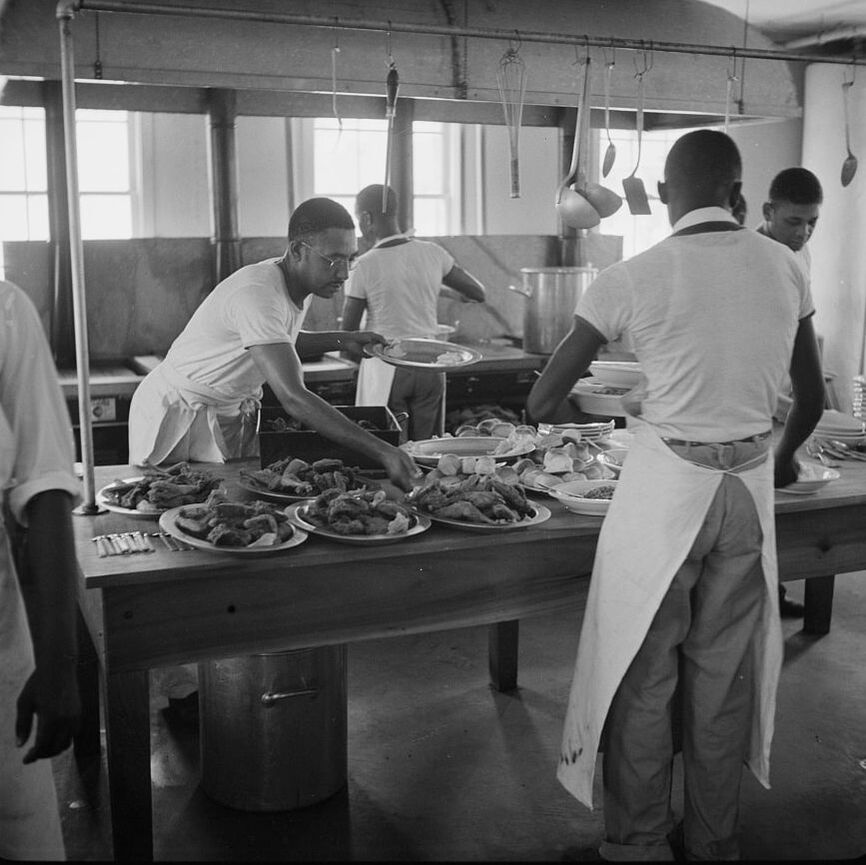

Fried ChickenAlthough who really brought fried chicken to the Americas is disputed (did it come from Africa, Scotland, or some confluence of the two?), by the late 18th century fried chicken is indisputably tied to the South and enslaved cooks. A special-occasion dish that, following the American Civil War, became a real source of income for freed people and their descendants, fried chicken became emblematic of soul food in the 20th century. Further Reading:

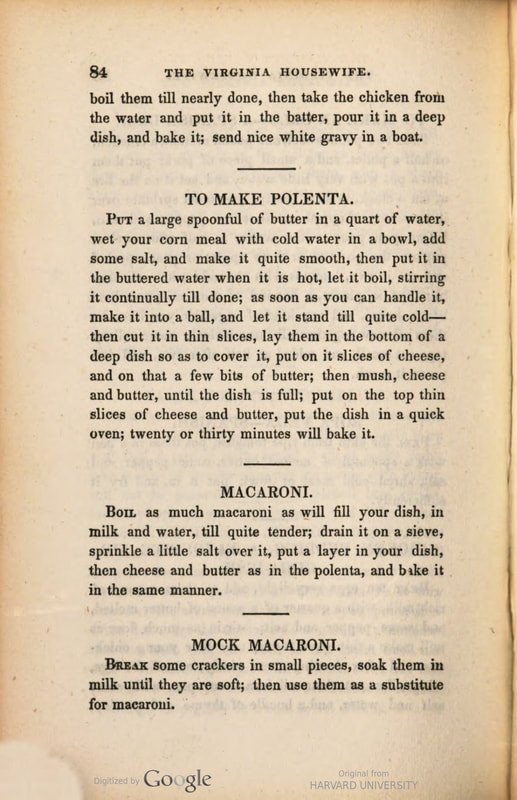

Macaroni and CheeseIs there a more quintessentially American food than macaroni and cheese? It has surprising origins, but was popularized early in American history thanks largely to an enslaved man - James Hemings, Thomas Jefferson's enslaved chef de cuisine. Its popularity among Black Americans is almost certainly due to the long history of macaroni and cheese in Southern (and mostly black-staffed) kitchens. Its use in railroad dining cars staffed by Black cooks also helps popularize it with Americans of all backgrounds. Further Reading:

Obviously, this is not a complete list, but I hope you learned a little something new with this post. As we all celebrate Juneteenth, let's not forget to keep recognizing the contributions of enslaved people and their descendants in contributing significantly to American food and culture throughout our nation's history. Want to learn more? Check out last year's "Black Food Historians You Should Know" for even more further reading. The Food Historian blog is supported by patrons on Patreon! Patrons help keep blog posts like this one free and available to the public. Join us for awesome members-only content like free digitized cookbooks from my personal collection, e-newsletter, and even snail mail from time to time! Don't like Patreon? Join with an annual membership below, or just leave a tip! Join on Patreon or with an annual membership by June 30, 2020 and get a picnic history packet mailed to your door!

1 Comment

This post contains affiliate links. If you purchase any of the listed books, you'll help support The Food Historian!

A friend of mine is a retired librarian from New York University. A few weeks ago he told me a fascinating story - in the 1970s, in order to make room in the library for new works, the powers that be at NYU decided to get rid of all the master's theses in the library collection. Master's graduates who were still alive and with addresses on file were contacted and asked if they would like their originals. Some departments saved works they thought were important. But most were destined for the dumpster.

A young librarian had been hired specifically to dispose of the collection. One day, someone walked in off the street, pulled a typed thesis off the shelf, handed it to the that librarian, and said, "This is an extremely important work, please don't throw it out," and walked away. That librarian kept that thesis, and when she quit at the end of the depressing project, she passed it onto my friend, who tucked it way in his desk drawer. Almost a decade later, in the 1980s, he happened to be walking by the circulation desk when a "rookie librarian" was dealing with a request to see a Master's thesis for the first time. "Isn't that right? All the MA theses were thrown away?" she asked him. My librarian friend started to say, "Yes that's right," and the he looked at the index card the researcher had handed over, and added, "except for the one you are looking for, which is in my desk." Rumors of this particular thesis had been swirling among scholars for years, which was how the researcher knew exactly what to request, despite the fact that it was not listed in the library catalog. That work was "The Chinese Restaurants in New York" by master's student Louis H. Chu, which he completed in 1939, along with his Master's degree in Sociology. It WAS an extremely important work - it cataloged Chinese restaurants in New York City at a time when people didn't seem to care much about food history, or about Chinese America. Chu's thesis was largely forgotten. He is better known for going on to write the groundbreaking novel, Eat a Bowl of Tea (1961), which was set among the lives of unmarried Chinese immigrant men in New York City's Chinatown. Although it was not a critical success at the time, it found greater acclaim in the 1970s. In 1989 it was made into a film. It is still cited as one of the most influential works of Asian-American literature.

In addition to his book, Chu also hosted a long-running radio program of Chinese music, and in 1961, he appeared as the mystery guest on the popular television show, "What's My Line?" as part of a promotion for Eat a Bowl of Tea.

"The Chinese Restaurants of New York," however long it languished in that fateful desk drawer, did go on to influence of a generation of researchers of the Chinese-American experience. The thesis is cited in at least twelve subsequent works, including influential recent books like Chop Suey, USA: The Story of Chinese Food in America by Yong Chen (2016), Eating Asian American: A Food Studies Reader (2013), and Sweet and Sour: Life in Chinese Family Restaurants by John Jung (2010).

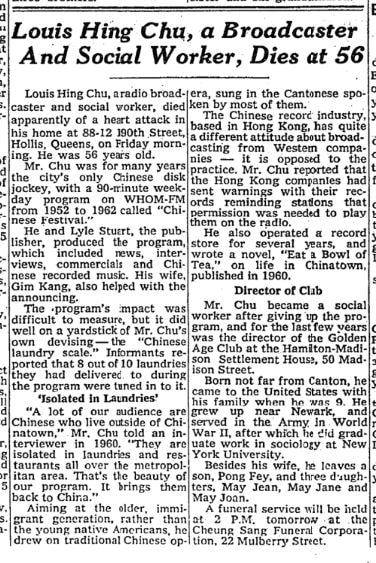

Louis Hing Chu died at home in Hollis, Queens of an apparent heart attack on Friday, February 27, 1970. He was just 56 years old. His obituary focuses on his work as a disc jockey for WHOM-FM, where he played Chinese music for a 90 minute show called "Chinese Festival," which aired on weekdays between 1952 and 1962. Here's the full text of the obituary, "Louis Hing Chu, a Broadcaster and Social Worker, Dies at Age 56," published in the New York Times on March 2, 1970:

Louis Hing Chu, a radio broad caster and social worker, died apparently of a heart attack in his home at 88‐12 190th Street, Hollis, Queens, on Friday morning. He was 56 years old. Mr. Chu was for many years the city's only Chinese disk jockey, with a 90‐minute week day program on WHOM‐FM from 1952 to 1962 called “Chinese Festival.” He and Lyle Stuart, the publisher, produced the program, which included news, inter views, commercials and Chinese recorded music. His wife, Gim Kang, also helped with the announcing. The program's impact was difficult to measure, but it did well on a yardstick of Mr. Chu's own devising— the “Chinese laundry scale.” Informants reported that 8 out of 10 laundries they had delivered to during the program were tuned in to it. ‘Isolated in Laundries’ “A lot of our audience are Chinese who live outside of Chinatown,” Mr. Chu told an interviewer in 1960. “They are isolated in laundries and restaurants all over the metropolitan area. That's the beauty of our program. It brings them back to China.” Aiming at the older, immigrant generation, rather than the young native Americans, he drew on traditional Chinese opera, sung in the Cantonese spoken by most of them. The Chinese record industry, based in Hong Kong, has quite a different attitude about broad casting from Western companies — it is opposed to the practice. Mr. Chu reported that the Hong Kong companies had sent warnings with their records reminding stations that permission was needed to play them on the radio. He also operated a record store for several years, and wrote a novel, “Eat a Bowl of Tea,” on life in Chinatown, published in 1960. Director of Club Mr. Chu became a social worker after giving up the pro gram, and for the last few years was the director of the Golden Age Club at the Hamilton‐Madison Settlement House, 50 Madison Street. Born not far from Canton, he came to the United States with his family when he was 9. He grew up near Newark, and served in the; Army, in World War II, after which he did graduate work in sociology at New York University. Besides his wife, he leaves son, Pong Fey, and three daughters, May Jean, May Jane and May Joan. A funeral service will be held at 2 P.M. tomorrow at the Cheung Sang Funeral Corporation, 22 Mulberry Street. Sadly, Chu died before his novel became more widely respected. And neither NYU nor UCLA, which holds the only other copy of his thesis, have ever seen fit to digitize "The Chinese Restaurants of New York," which seems a shame, given how influential it has gone on to become. I, for one, am just grateful to that unidentified person who knew the work well enough to try to save it, and for the librarians who did. My librarian friend updated me that he tried to request the original thesis, which is now cataloged, but was told it was "processing," which hopefully means it is being digitized, so it won't ever be at risk of destruction again.

The Food Historian blog is supported by patrons on Patreon! Patrons help keep blog posts like this one free and available to the public. Join us for awesome members-only content like free digitized cookbooks from my personal collection, e-newsletter, and even snail mail from time to time!

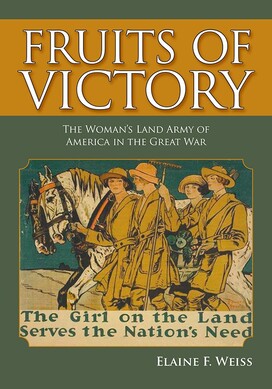

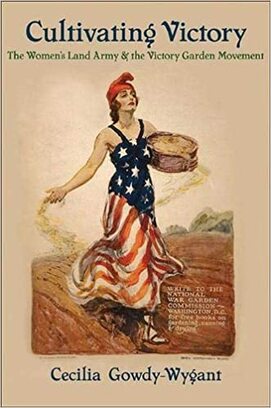

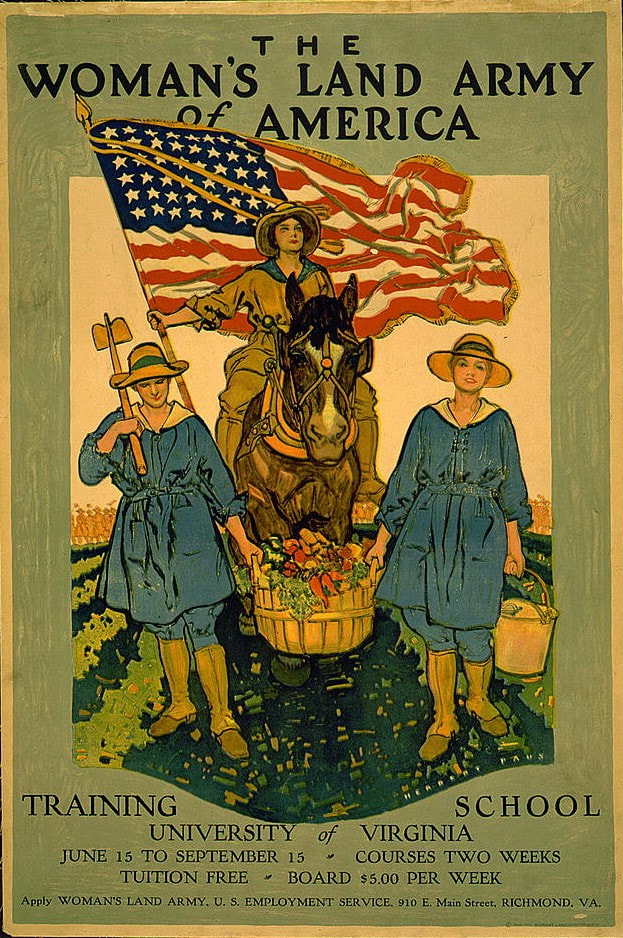

This post contains affiliate links. If you purchase something from a link, you'll be supporting The Food Historian! The Woman's Land Army of America came out of the women's suffrage movement as a way for young, largely college-educated women to prove their worth during wartime by providing agricultural labor to make up labor shortages thanks to the draft, better wages in industrial work, and the need to increase agricultural production. The movement started in New York State, and has been ably chronicled by Elaine Weiss' book The Fruits of Victory. This beautiful propaganda poster from the University of Virginia Training School for the Woman's Land Army of America is just delightful. The imagery is evocative. A young woman holding an American flag, which billows out behind her, is dressed in a khaki uniform and riding a plow horse through a green agricultural field, simultaneously calling to mind a mounted standard bearer, Teddy Roosevelt's Rough Riders, and Army cavalry. In the foreground, two young women in matching blue uniforms share the load of a bushel basket laden with vegetables. The woman at left has a hoe over her shoulder, reminiscent of how a soldier might carry a rifle. The woman at right carries what appears to be a milk pail. Far in the background, what appears at first glance to be a field of ripe wheat is in fact a golden line of uniformed women with agricultural implements on their shoulders, marching behind the leading three. The costumes were among the official Woman's Land Army costume - in khaki and blue chambray. A loose tunic with full sleeves (rolled up) and a cinched waist falls to the knee, covering military-style jodhpurs and puttees over sensible shoes. A broad-brimmed hat and a kerchief around the neck complete the sensible outfit, which somehow still scandalized some members of the public at a time when women's skirts rarely rose above the ankle. The poster is advertising the Woman's Land Army's Training School at the University of Virginia. Designed to give young women basic agricultural skills, and sometimes specialized skills like the use of tractors, the schools were generally free, but required payment for room and board, as this one does at $5.00 per week for a two week course. Sometimes called "farmerettes," likely a combination of the terms "farmer" and "suffragette," and one which not every member of the Woman's Land Army enjoyed. But then, not every farmerette was a member of the Woman's Land Army, and the term actually predated the U.S. entrance into the war. The women saw some success in the adoption of their labor in agriculture, but it created no sea change of labor distribution post-war. Most farmers outside orchards and truck farmers mechanized in the face of labor shortages, rather than using farmerettes or farm cadets (teenaged boys released from school to work on farms). And increasing specialization of crops and livestock meant that mechanization was easier and more profitable than hiring young women at good wages for just 8 hour days (pre-war farm laborers had no such protections). The Land Army would be revived during World War II, this time divorced from its suffragist origins and encouraging young people of both sexes to assist with farm labor. But that's a post for another day. Woman's Land Army Books Fruits of Victory: The Woman's Land Army of America in the Great War by Elaine F. Weiss Weiss tracks the evolution of the Woman's Land Army in America, focused primarily on New York State, which was where the WLA officially began in the U.S. In intimate detail, she introduces us to a whole host of historic characters, including leading lights of the women's suffrage movement, and how they tried to prove women's agricultural labor was the future.  Cultivating Victory: The Women's Land Army and the Victory Garden Movement by Cecilia Gowdy-Wygant Cultivating Victory examines the interrelationships between the British and American Woman's Land Armies, as well as their connections to the war garden and victory garden movements. Covering both the First and Second World Wars, Gowdy-Wygant compares and contrasts the efforts in both nations and the differences and similarities between both wars. The Food Historian blog is supported by patrons on Patreon! Patrons help keep blog posts like this one free and available to the public. Join us for awesome members-only content like free digitized cookbooks from my personal collection, e-newsletter, and even snail mail from time to time! Join by June 30, 2020 and get a picnic history packet mailed to your door! Rice is one of the world's oldest cultivated crops. Domesticated in China as many as 15,000 years ago, trade routes helped spread this grain across the ancient world. Rice has many different uses, but porridge-y things, from congee to rice pudding, seem common in cultures around the world. Although Americans may be most familiar with Asian "white rice" and "brown rice," there are actually hundreds of different varieties. In fact, the first rice to be cultivated in the United States was actually an African variety. The development of rice plantations in the American South is a direct result of skilled labor and knowledge by enslaved Africans exploited by the people who enslaved them. South Carolina and Georgia in particular were some of the few places in North America where rice was grown commercially until the later 19th century, when rice spread to Louisiana and Texas. In the early 20th century, Arkansas and California followed suit. Today, Southern states still grow Carolina varieties of African rice, while California focuses more on japonica varieties of Asian rice, likely influenced by Chinese immigration during the Gold Rush of the 1840s and after. Early recipes for rice pudding included cooking it in a pie crust, baking it with just butter and milk, or in a custard. In the U.K., a short-grained "pudding rice" is most often used to make rice pudding. In the U.S., Americans tend to use long grain white rice varieties. You don't find rice pudding too often these days. Usually relegated to nursing homes and hospitals, you'll occasionally find it on restaurant (or especially New York deli) menus. But I think rice pudding deserves a revival. When life has you down, nothing tastes more comforting and nourishing than homemade rice pudding. But rice pudding can be finicky stuff to make. I don't know when I discovered the idea for this genius recipe, but I'm sure it was somewhere on the internet about ten years ago. This recipe couldn't be easier, and it's the only one I ever use. No eggs, no custard, no baking, one pot and done. So simple. As a Scandinavian, rice pudding is in my blood. This one is a cross between the traditional Norwegian kind, served hot and cinnamon-y at Christmas, with a lucky almond in someone's bowl resulting in a marzipan pig, and the Swedish kind I grew up eating at midsommar - cold, creamy, and with raspberries on top. It's good hot or cold, with or without milk or cream or whipped cream. It's one of my favorite comfort recipes, and I hope you enjoy it, too. Easy Rice PuddingThe genius of this recipe comes from the substitution of arborio or risotto rice for regular white rice. The arborio rice thickens the milk as it cooks, creating a creamy, sweet deliciousness that's in the rice to the core. I can't take credit for discovering it, and the American who came up with it was probably inspired by the "pudding rice" of the U.K., but it's too easy and delicious not to share. This recipe does bear a little watching, as milk is quick to boil over, but make it while you're doing dishes, baking something, or otherwise puttering around in the kitchen. 1 cup arborio rice 5-6 cups whole milk (or milk of your choice) 1/2 cup sugar 1 cinnamon stick about 1 cup raisins (I used half Thompson and half golden) Place all ingredients in a 4 or 5 quart stock pot and cook over medium to medium-high heat until the milk comes to a boil (watch it so it doesn't boil over!). Then reduce the heat to medium low and cook, stirring frequently, until most of the milk is absorbed. When it's still a bit soupy, turn the heat off and let the rice rest. It will absorb more milk as it sits. Serve hot for breakfast or warm or cold for dessert. It keeps well in the fridge, but the rice will absorb milk, so if it gets too thick, add a little milk to thin. If you don't have a cinnamon stick, a sprinkling of ground cinnamon is fine. If you'd rather leave out the raisins, feel free! Add dried cranberries, blueberries, or serve with fresh or frozen strawberries or raspberries. You could also flavor with orange or lemon zest, nutmeg, almond or vanilla extract, or any other flavorings you enjoy. Do you have a favorite creamy dessert? A favorite way to eat rice pudding? I must admit that while this recipe is very good, it's not quite as good as the Swedish rice pudding I grew up eating, which was VERY creamy, sweet, and served cold with thawed frozen sweetened raspberries with their juice. I would stir it to turn the rice pudding purple and make sure I got raspberries in every bite. Alas, the only recipe I have for that makes gallons, so I've never tried it.

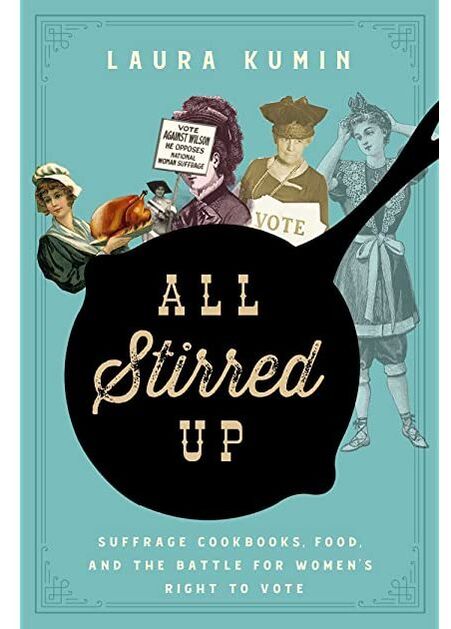

The Food Historian blog is supported by patrons on Patreon! Patrons help keep blog posts like this one free and available to the public. Join us for awesome members-only content like free digitized cookbooks from my personal collection, e-newsletter, and even snail mail from time to time! This article contains Amazon.com and Bookshop.org affiliate links. If you purchase anything from these links, The Food Historian will receive a small commission. All Stirred Up: Suffrage Cookbooks, Food, and the Battle for Women’s Right to Vote, Laura Kumin. New York: Pegasus Books, 2020. 357 pp., $28.95, hardcover, ISBN 978-1-64313-452-9. ,I first learned about cookbooks associated with women’s suffrage thanks to this Atlas Obscura article and I was instantly fascinated. Feminism in the 20th century was often more interested in throwing off the chains of household drudgery than with enticing converts through snacks. But that is precisely the premise of All Stirred Up: Suffrage Cookbooks, Food, and the Battle for Women's Right to Vote, which is why I was so excited that I put it on my Christmas wish list. I was expecting a thorough examination of the suffrage cookbooks, the women who created them, and their place in the movement. Sadly, as a book, All Stirred Up is like an underdone cake – it looks perfect on the outside, but the inside is doughy and disappointing and could have used another 30 minutes in the oven. Laura Kumin is a former lawyer turned cooking educator and food writer. She does not have a historical background, and, as is the case with many non-historians who write food history, it shows. All Stirred Up begins, even before the introduction, with a lengthy timeline. While I find timelines to be incredibly useful, especially when dealing with complex chronology, starting the book with one was not a choice I would have made. It is confusing to the reader, who is presented lengthy and disparate facts without context or introduction. A lack of context is a theme for the book. Kumin’s introduction is part explanation of her interest in suffrage cookbooks and part layout of her main argument. She makes a compelling case that modern takes on suffrage history have largely ignored the role of cookbooks in converting skeptics to the cause. Unfortunately, this argument is not often revisited in the subsequent chapters. Most of the chapters are quite brief, some as few as eight pages, and while historical overviews abound, actual analysis is lacking. Taking up the most space are the recipe sections that follow each chapter, organized by type. Although these recipes are directly taken from the suffrage cookbooks, with modern adaptations designed by Kumin, there is no context for any of the recipes and no dates listed. Most recipe sections draw from multiple suffrage cookbooks without differentiating between them, beyond noting where the originals came from. We do not know why Kumin chose these particular recipes, how they reflected the cookbooks and times from whence they came, or even what, if any, relevance they had to the suffrage movement. For many chapters, the number of pages devoted to recipes outweigh the pages devoted to history. As for the history itself, most of it is shallow summaries meant to orient the reader to the basics of suffrage history, home economics and food science, and basic culture of the period. While this context is useful for non-historians, it seems to come at the expense of historical analysis. In addition, the chronology of the book is all over the place. The book begins in 1848, with an exercise in “time travel” in which Kumin writes in the present tense. Then zooms ahead to the Progressive Era and back again several times. At the end of Chapter 3, we’re already at the 19th Amendment in 1920, an achievement which is not really revisited for the rest of the book. Throughout the book, the suffrage movement in one decade is conflated with the same movement decades later. Little attention is paid to the context of national culture on the way in which the women's suffrage movement was operated, despite the fact that it was under operation, in one way or another, for over 70 years. Missed opportunities to make connections to other major movements, including abolitionism, Temperance (which is dismissed as detrimental to the cause, p. 78-79), Progressive reform, government regulation, etc., abound. Chapters 3, 4, and 6 are the strongest, content- and argument-wise. In Chapter 3, “From Seneca Falls to the Ballot Box,” Kumin examines the suffragists themselves and the post-Civil War resurgence of the movement. To her credit, she makes a point of mentioning African American suffragists and their shameful treatment by mainstream white suffragists, as well as male allies and the “antis” – anti-suffragists. However, points that needed more analysis were often presented as literal sidebars in the text. For instance, noted suffrage ally Frederick Douglass, instead of being included in the main text, receives a short summary in a gray box. The Beecher family get similar treatment in a sidebar about how the movement split families. Catharine Beecher, a fervent anti-suffragist, was a cookbook author and young women’s educator of some renown and who, despite conflicting ideas about suffrage, nonetheless co-wrote The American Woman’s Home with her suffragist sister. Cookbook author, fervent abolitionist, and Native American rights activist Lydia Maria Child is mentioned in a quotation, but otherwise ignored. These are just a few of many missed opportunities to engage with the subject matter more deeply – discussing how both suffragists and “antis” used women’s work and the home in their arguments for and against suffrage. Chapter 4, “We Can Peel Potatoes and Fight for the Vote, Too! Suffrage Strategies and Battle Tactics” is the strongest chapter in the book, and one of the few that cites primary sources in the endnotes. Discussing the divergent tactics between “mainstream” and “militant” suffragists, Kumin compares the mainstream work of the cookbooks, cafeterias, the “doughnut campaign,” a “Pure Food” storefront, and cooperating with agricultural extension, to the militant tactics of parades, protests, arrests, and hunger strikes. Unfortunately, she does not define who exactly is “mainstream” and who is “militant,” except to note differing tactics. Kumin argues that the more mainstream feminists were more successful in changing hearts and minds, but presents little evidence to back up this claim. In addition, despite covering the bulk of the Progressive Era, the chapter mentions, but gives little context to agricultural extension, the Temperance movement, home economics, World War I, and women’s clubs. An overview of home economics and food science comes in the following chapter, “Revolution in the Kitchen.” Chapter 6 finally addresses the cookbooks themselves, with an overview of how they were financed, celebrity contributors, and how the recipes included were reflective of the periods in which they were published. The cookbooks are still dealt with in generalizations, however, and their individuality is lost in the mix. The section on celebrities, although interesting contains another missed opportunity, as Kumin mentions one recipe contribution from noted feminist Charlotte Perkins Gilman, but not her dislike of cooking. In the section on funding, Kumin clearly notes that the cookbooks were usually designed as fundraisers for the organizations, a fact that belies her argument that cookbooks were meant to convert, though she does note they were sometimes also used as enticing premiums for subscriptions. Chapter 7 is a brief discussion of how suffragists used dinners and entertaining to support the cause. All Stirred Up ends without a clear conclusion, instead relying on Chapter 8, “What Suffrage Means for Us,” an eight-page summary of women in American politics since 1920. This final chapter makes no clear reference to the influence of the cookbooks that purportedly drove the suffrage movement and does not sum up the arguments outlined in the introduction. It is followed by 28 pages of dessert recipes. There is no explanatory postscript, only Kumin’s acknowledgements. In all, All Stirred Up does make a good point about the role of suffrage cookbooks in the movement, but it fails to back up its few arguments convincingly, particularly in light of the use of community cookbooks as fundraising tools, rather than modes of conversion to the cause. Instead of concentrating the bulk of her argument into Chapter 4, Kumin would have had a much more compelling book had she spread that argument throughout all the chapters, addressing the role of domesticity from the perspectives of both the suffragists and the antis. More primary source analysis would have enriched the narrative. Looking at the writing of major suffrage leaders to determine their personal opinions on cooking and domesticity would have added depth to her arguments. Examining the cookbooks themselves, their recipes, and the organizations and women that produced them as a chronological accounting of the movement, would have added greatly to the coherence and context of the book. Had the recipe sections been introduced by era, with headnotes and historical context for each recipe, their inclusion would have made the book both stronger and appealing to the general public. Ultimately, the book feels as though it was rushed to print, possibly to coincide with the centennial anniversary of the 19th Amendment in 2020. If you are unfamiliar with basic suffrage and food history, this may provide some good historical summaries and Kumin’s research on the 1909 Washington Women’s Cook Book is particularly strong. But, if you were hoping for a well-written, well-organized examination of the role of food in the suffrage movement and the influence of suffrage cookbooks, as I was, you’ll be sorely disappointed. I can only hope that future historians can expand on Kumin’s work. If you'd like more food history book reviews, check out the Book Review category of this blog. The Food Historian blog is supported by patrons on Patreon! Join us for awesome members-only content like free digitized cookbooks from my personal collection, e-newsletter, and even snail mail from time to time!

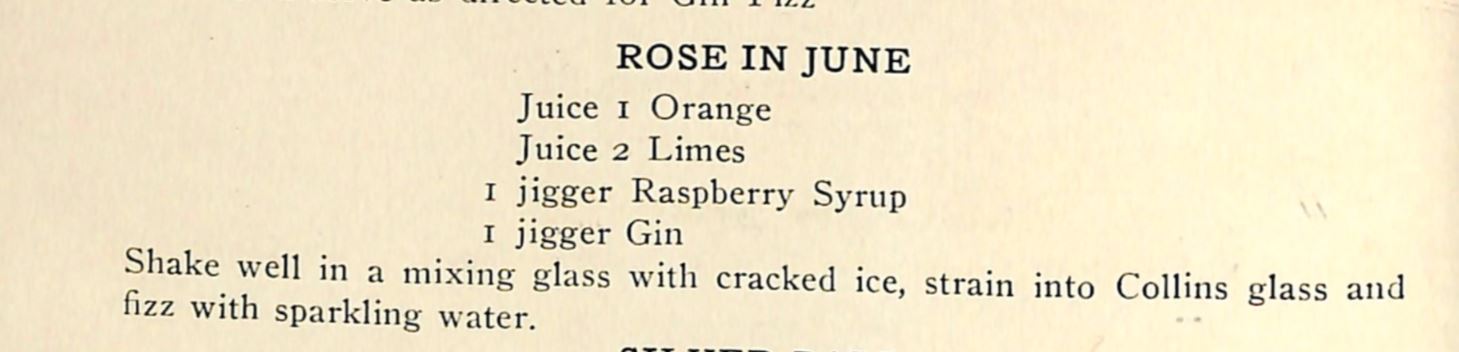

It's Juneteenth! Thanks to everyone who joined us for Food History Happy Hour. This week we make the Rose in June cocktail from the 1917 "Recipes for Mixed Drinks." We discussed Juneteenth, red velvet cake, victory gardens including propaganda and the exclusion of Black farmers and imprisoned Japanese Americans, the role of visuals in influencing taste, Black Food Historians You Should Know, disparities in book contracts, hot weather foods, salads, summer kitchens, how historical peoples coped without air conditioning, how historical peoples kept foods cold before refrigeration, ice and ice cream in the ancient world, rural electrification and electric refrigerators, the Frigidaire Cookbook, icebox pie, racial stereotypes in food advertising, including the history of the "Aunt" and "Uncle" terms, including Uncle Ben and Aunt Jemima, the history of the mammy trope, the tragedy of child caring roles, What Mrs. Fisher Knows About Old Southern Cooking, Black children in advertising, Franchise: the Golden Arches in Black America, the forthcoming book scanner I ordered, monuments and statues, and we ended with a signal boost for the James Hemings Society.

Rose in June Fizz (1917)

The "Rose in June" cocktail comes from the "Fizz" section of Recipes for Mixed Drinks by Hugo Ensslin (1917).

The original recipe calls for: Juice of 1 orange Juice of 2 limes 1 jigger raspberry syrup 1 jigger gin Shake well in a mixing glass (or cocktail shaker) with cracked ice, strain into Collins glass and fizz with sparkling water OR - if you don't have fresh citrus fruits OR raspberry syrup - you can substitute 1/3 cup orange juice, 1/4 cup lime juice, a heaping tablespoon of raspberry (or in my case, strawberry) jam, and the gin. Very nice, very refreshing, but sadly NOT pink.

Here's a roundup of links related to everything we talked about (in addition to all the links above!):

If you liked this post and would like to support more Food History Happy Hour livestreams, please consider becoming a member or joining us on Patreon. Members and patrons get special perks like access to members-only content.

Many thanks to the Southeastern New York Library Resources Council for hosting my talk and for recording it! Much (but certainly not all!) of the research I've done for my book is presented in condensed form here. I think it turned out very nicely indeed and I am now contemplating recording more of my talks for sharing online. What do you think? Should I?

Here is some further reading based on some of the topics I discussed in the talk:

Capozzola, Christopher. Uncle Sam Wants You: World War I and the Making of the Modern Eighmey, Rae Katherine. Food Will Win the War: Minnesota Crops, Cooks, and Conservation during World War I. St. Paul, MN: Minnesota Historical Society Press, 2010. Gowdy-Wygant, Cecilia. Cultivating Victory: The Women's Land Army and the Victory Garden Movement. Pittsburgh, PA: University of Pittsburgh Press, 2013. Hall, Tom G. “Wilson and the Food Crisis: Agricultural Price Control during World War I.” Agricultural History 47, no. 1 (1973): 25-46. Hayden-Smith, Rose. Sowing the Seeds of Victory: American Gardening Programs of World War I. Jefferson, NC: McFarlan and Company, Inc., 2014. Veit, Helen Zoe. Modern Food, Moral Food: Self-Control, Science, and the Rise of Modern American Eating in the Early Twentieth Century. Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina Press, 2013. Weiss, Elaine F. Fruits of Victory: The Woman’s Land Army of America in the Great War. Washington, D.C: Potomac Books, 2008.

If you or your organization would like to host a talk - virtual or otherwise - please make a request!

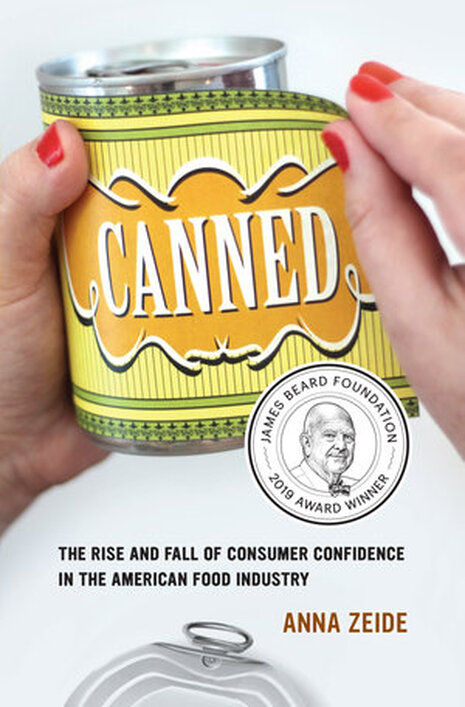

This post was supported in part by Food Historian members and patrons! If you liked this post, please consider becoming a member or joining us on Patreon. Members and patrons get special perks like access to members-only content. Once again the wheels of publishing grind slowly, but I'm pleased as punch to see one of my book reviews in print again, this time in the Spring 2020 edition of the Agricultural History Journal. Canned: The Rise and Fall of Consumer Confidence in the American Food Industry. By Anna Zeide. Oakland: University of California Press, 2018. 269 pp., $34.95, hardcover, ISBN 9780520290686. Few people these days haven’t tasted canned food, but have you ever considered its origins? Tin cans versus glass jars? The science of safe canning? Anna Zeide did in her new book Canned: The Rise and Fall of Consumer Confidence in the American Food Industry. Tracking the rise of commercially canned foods in America from the condensed milk of the Civil War to modern concerns about bisphenol-A (BPA), Zeide puts canned goods firmly in historical context – connecting them to changes in technology, agricultural science, medicine, politics, and social changes. On the surface, the book is about the safety of canned goods; Zeide studies the roles of lead poisoning, spoilage, botulism, mercury in canned fish, and the 21st century issue of bisphenol-A (BPA) contamination in shaping consumer use of and confidence in canned goods. The chapters are arranged as case studies and are outlined in chronological order. The introduction outlines the history of canning technology (and safety) before moving on to condensed milk in the post-Civil War era and the rise of chemical additives and improvements in canning technology. The chapter on canned peas in the 1910s discusses the relationship between canners, agricultural research, and vertical integration of farming with vegetable varieties bred to be canned, embracing agricultural grading. The chapter on canned ripe olives addresses the threat of botulism in the 1920s, and how the canning industry resisted regulation and attempted to place the blame on careless home canners. The chapter on canned tomatoes in the 1930s outlines how canners resisted grading of canned goods, even as they embraced it for their own suppliers, and attempted to read the mind of “Mrs. Consumer,” now an economic force to be reckoned with. The chapter canned tuna and mercury contamination in the 1970s chronicles the rise of processed food more broadly, the expansion of canners beyond canned food, and the backlash against artificial ingredients, pesticides, and other contaminants in canned goods and industrial food. Finally, Zeide ends with a discussion of consumer fears about BPA in Campbell’s canned soups in the 2010s, and Campbell’s attempts to cover up health concerns even as it tried to appeal to a new, food-savvy generation of consumers. As you can probably tell, beneath the study of the relationship between consumers and food processors is the real meat of the book – on regulation of the industry. At first, early canners were happy to work with government regulators to prove themselves worthy in a crowded and competitive market. And access to agricultural colleges for crop research and federal food safety research were benefits they were only too happy to embrace. But as food processors consolidated and the 20th century wore on, canners became increasingly resistant to government regulation, oversight, and transparency. So much so that by the 2010s when Campbell’s Soup was confronted with consumer concerns about the endocrine disrupting BPA, they closed ranks and denied any safety concerns. But, despite promises to end the use of BPA in can liners and even as it hopped on other bandwagons such as the labeling of genetically modified foods, as of 2016 Campbell’s had yet to replace BPA in their cans. Zeide concludes the book by outlining why government regulation and collective action is more effective in maintaining food safety than the industry’s beloved individual action. Throughout the book, food processors claim that “Mrs. Consumer” can choose for herself which brands are the safest and highest quality, but that ignores circumstances beyond consumer control, such as the case study Zeide cites in which consumers fed on a diet devoid of canned goods and full of locally produced whole foods actually saw their BPA levels increase, likely due to the use of BPA in plastics used as part of the even minimal food processing, such as in the milking industry or in the production of spices in other countries (p. 183). Ultimately, Zeide tries to place canned goods briefly in context in the conclusion – that access to canned fruits and vegetables gave a whole subset of Americans access to nutrients they might not have had access to before, and that emotional responses to the foods of our childhoods will give canned goods longevity. Although at various places throughout the book Zeide makes mention of potential class issues surrounding canned goods, and the assumptions of canners that “Mrs. Consumer” was white and middle class, a more thorough examination of class and race in the context of canned goods would have made this book even stronger, especially considering the emphasis on consumer marketing. However, despite this omission, Canned is ultimately a strong addition to food historiography and I applaud Zeide for her detailed work and her ability to place events and people in context, drawing connections and conclusions that are well supported by her research. If you enjoyed this book review, please consider becoming a member or joining us on Patreon. Members and patrons get special perks like access to members-only content and discounts on programs and classes.

It's Black History Month here in the United States, and while I firmly believe that Black history should be studied and celebrated year-round, I thought this would be a good time to highlight some of the good articles and important contributions by Black food historians and cookbook authors.

I'll be sharing articles on Facebook all month, but wanted to make some lists for reference, plus links to lots of great books! The following historians are in no particular order, but you should read about them all! And if you want to support them (and, by extension, The Food Historian), you can purchase one or more of their books! Jessica B. Harris

Dr. Jessica B. Harris is considered one of the foremost experts on African diaspora food and has written a number of books and cookbooks on the subject. In 2019, she was inducted into the James Beard Foundation Cookbook Hall of Fame. She was also featured on "The Food that Built America," along with numerous other television appearances.

She is probably best known for her 2012 history, "High on the Hog: A Culinary Journey from Africa to America," which links Southern (read: African) food traditions back to Africa and their connections to slavery. You can learn more about Dr. Harris on her website, or check out one of her numerous books! Adrian Miller

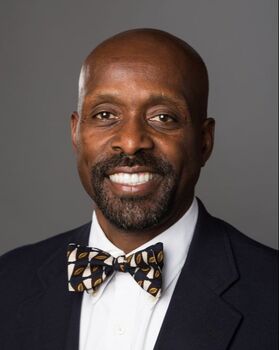

Adrian Miller is the Soul Food Scholar. He is a certified barbecue judge and culinary historian whose two books, "Soul Food: The Surprising Story of an American Cuisine, One Plate at a Time," and "The President’s Kitchen Cabinet: The Story of the African Americans Who Have Fed Our First Families, from the Washingtons to the Obamas," have both won numerous awards. He's currently working on a new book, "Black Smoke," a history of African American barbecue culture.

Tonya Hopkins

I first met Tonya as she was recreating a 19th century African-influenced dinner that Black cook Anne Northup (wife of Solomon Northup - of 12 Years a Slave fame) might have cooked while she was working at the Morris-Jumel Mansion in New York City. I had a wonderful time and Tonya lives up to her "griot" name as a fantastic storyteller. Although Tonya has not yet written her own book, she has contributed to numerous scholarly publications. She is also co-founder of the James Hemings Foundation, named after Thomas Jefferson's enslaved, French-trained chef de cuisine, and consultant on the upcoming exhibit at MOFAD, "African/American: Making the Nation's Table."

Michael Twitty

Michael Twitty is a bit unique in this group - not only is he a researcher, cook, and writer, he is also a historical interpreter. Twitty first rose to prominence with his 2013 Open Letter to Paula Deen, calling out her racism and appropriation of African American foodways under the guise of "Southern" food. In 2017, he published "The Cooking Gene," which Twitty calls, "a genealogical detective story, a culinary treasure map, a blueprint for finding your roots, a series of history lessons, a revealing memoir and a spiritual confessional sprinkled with recipes." In 2018, it won the James Beard Foundation's Book of the Year Award. You can read more of his work on his blog, Afroculinaria.

Toni Tipton-Martin

I first heard of Toni Tipton-Martin with the buzz around the publication of "Jemima Code: Two Centuries of African American Cookbooks," which was the 2016 James Beard Foundation Book Award winner. I purchased a copy at an OAH conference and loved it. Toni also had a longstanding career as a food journalist and is a cookbook writer as well. You can learn more about her on her website.

Frederick Douglass Opie

Fred Opie (PhD) is a Professor of History and Foodways at Babson College. He has written a number of engaging food histories, including one of Zora Neale Hurston's WPA-era writing on Florida Food. Fred also hosts a podcast and writes extensively about foodways on his blog, in addition to other projects.

Psyche Williams-Forson

Psyche Williams-Forson is Associate Professor and Chair of the Department of American Studies at University of Maryland College Park. Psyche is probably best known for her work, "Building Houses Out of Chicken Legs: Black Women, Food, and Power." She has also curated two online exhibits: "Fire and Freedom: Food and Enslavement in Early America,” for the National Library of Medicine and “Still Cookin’ by the Fireside,” an online text and photo exhibition on the history of African American cookery for the Smithsonian Institution’s Anacostia Museum.

Marcia Chatelain

Marcia Chatelain is a Provost’s Distinguished Associate Professor of history and African American studies at Georgetown University. She was a Eric & Wendy Schmidt Fellow at New America from 2016-2018. She spent her fellowship year on a book that explores visions of economic and racial justice after 1968 and the fast food industry. That book is "Franchise: The Golden Arches in Black America," about building Black wealth and the role of fast food franchising in post-Civil Rights America, and it was JUST published in January, 2020!

Leni Sorensen

Leni Sorensen is a culinary historian and historical interpreter extraordinaire. Consulting with places like Colonial Williamsburg and Thomas Jefferson's Monticello, she is an expert on African-American foodways and Virginia cookery, particularly the work of Mary Randolph, who published The Virginia Housewife in 1824. Leni is now retired from museum interpretation, but continues to work as an independent scholar. You can learn more about her via her website. Or, read this great 2010 interview with Virginia Living.

I'm sure I've forgotten a few! If I have, please contact me and I'll update the list. If you enjoyed this list and you want to support The Food Historian (and all these wonderful historians!) you can just click on the cookbook images and purchase their books from Amazon! The authors will get their royalties and The Food Historian will get a small commission.

Or, if you're so inclined, you can join us as a member of The Food Historian. You can join online here, or you can join us on Patreon. Members get access to members-only sections of this website, special updates, plus discounts on future events and classes. And you'll help support free content like this for everyone. Join today! |

AuthorSarah Wassberg Johnson has an MA in Public History from the University at Albany and studies early 20th century food history. Archives

July 2024

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed