|

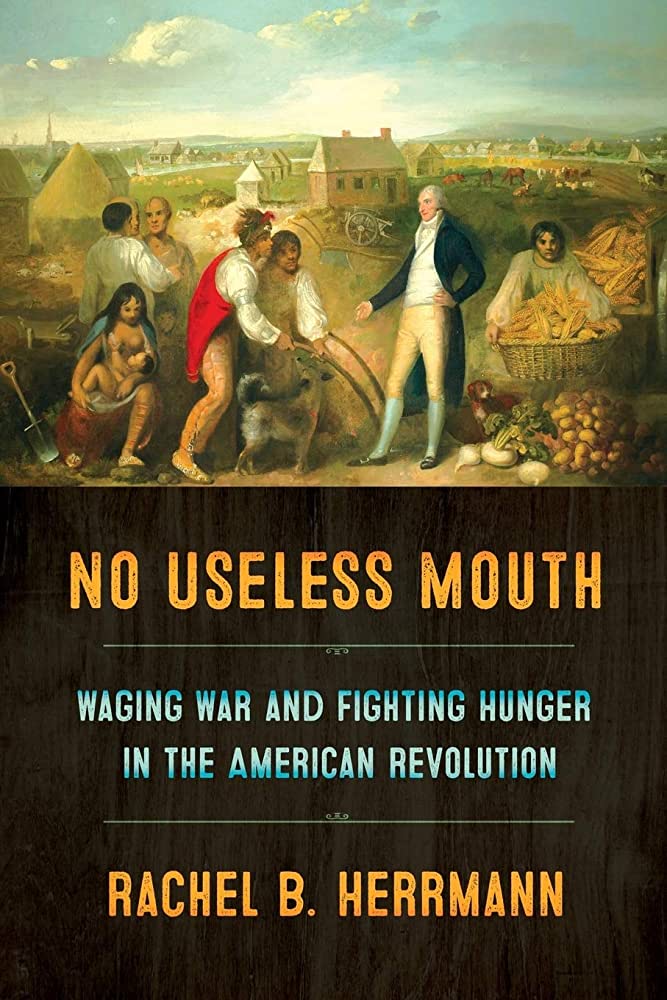

This article contains Amazon.com and Bookshop.org affiliate links. If you purchase anything from these links, The Food Historian will receive a small commission. No Useless Mouth: Waging War and Fighting Hunger in the American Revolution, Rachel B. Herrmann. Cornell University Press, 2019. 308 pp., $27.95, paperback, ISBN 978-1501716119. This may be the longest I have ever taken to write a book review. I first received this book and the invitation to review it for the Hudson Valley Review in the fall of 2021. As many of you know, 2022 was a rough year for me, for many reasons, but I finally turned in the review in February of 2023. A few days ago, I received my copy of the Review and now that my book review is in print, I feel I can share it here! This edition of the Review is great, with several excellent articles and other book reviews, so if you manage to find a copy, please check it out! Back issues are often posted digitally. Without further ado, the review: In the historiography of the American Revolution, one can be forgiven for thinking every possible topic has been covered. But Rachel B. Herrmann’s new book No Useless Mouth: Waging War and Fighting Hunger in the American Revolution brings new nuance to the period. In it, Herrmann argues that food played a decisive role in the shifting power dynamics between White Europeans, Indigenous Americans, and enslaved and free Africans and people of African descent. She looks at the American Revolution through an international lens, covering from 1775 in the various colonies through to the dawning of the 19th century in Sierra Leone. The book is divided into eight chapters and three parts. Part I, “Power Rising,” introduces us to the ideas of “food diplomacy,” “victual warfare,” and “victual imperialism” within the context of the American Revolution. Contrasting the roles of the Iroquois Confederacy in the north and the Creeks and Cherokees in the South, Herrmann brings additional support to the idea that U.S. treaties with Indigenous groups should join the pantheon of diplomacy history, while centering food and food diplomacy within the context of those treaties. She also addresses how Indian Affairs agents communicated with various Indigenous groups – with varying success. Part II, “Power in Flux,” addresses the roles of people of African descent in the American Revolution, focusing primarily on Black Loyalists as they gained freedom through Dunmore’s Proclamation and the Philipsburg Proclamation. Black Loyalists fought on behalf of the British as soldiers, spies, and foraging groups, and escaped post-war to Nova Scotia with White Loyalists. Part III, “Power Waning,” summarizes what happened to Indigenous and Black groups post-war, focusing on the nascent U.S. imperialism of Indian policy and assimilation and the role food and agriculture played in attempts to control Native populations. It also argues that Black Loyalists adopted the imperialism of their British compatriots in attempts to control food in Sierra Leone, ultimately losing their power to White colonists. Part III also includes Herrmann’s conclusion chapter. No Useless Mouth is most useful to scholars of the American Revolution, providing good references to food diplomacy while also highlighting under-studied groups like Native Americans and Black Loyalists. However, lay readers may find the text difficult to process. Herrmann often makes references to groups and events with little to no context, assuming her readers are as knowledgeable as she. In addition, the author appears to conflate Indigenous groups with one another, making generalizations about food consumption patterns and agricultural practices without the context of cultural differences. In focusing on the Iroquois Confederacy and the Creeks/Cherokee, Herrmann also ignores other Native groups, despite sometimes using evidence from other Indigenous nations to support her arguments. For instance, when discussing postwar assimilation practices with the Iroquois in the north and the Creeks and Cherokee in the south (often jumping from one to another in quick succession), she cites Hendrick Aupaumut’s advice to Europeans for dealing successfully with Indigenous groups. But she fails to note that Aupaumut was neither Iroquois, Creek, nor Cherokee, but was in fact Stockbridge Mohican. The Stockbridge Mohicans were a group from Stockbridge, Massachusetts that was already Christianized prior to the outbreak of the American Revolution. They fought on the Patriot side of the war, with disastrous consequences to the Stockbridge Munsee population, and ultimately lost their lands to the people they fought to defend. Without knowledge of this nuance, readers would accept the author’s evidence at face-value. Herrmann’s strongest chapters are on the Black Loyalists, and her research into the role of food control in both Nova Scotia and Sierra Leone is groundbreaking, but even those chapters have a few curious omissions. In discussing Lord Dunmore’s Proclamation, which was issued in 1775 in Virginia and targeted enslaved people held in bondage by rebels, freeing those who were willing to join the British Army. The chapter then focuses primarily on the roles of enslaved people from the American South. But Herrmann also mentions briefly the Philipsburg Proclamation, issued in 1779 in Westchester County, NY, which freed all people held in bondage by rebel enslavers who could make it to British lines. That proclamation arguably had a much larger impact on the Black Loyalist population, as it also included women, children, and those above military age, thousands of whom streamed into New York City, the primary point of evacuation to Nova Scotia. And yet, Herrmann does not mention at all enslaved people in New York and New Jersey, where slavery was still very active throughout the American Revolution and well into the 19th century. In the chapter on Nova Scotia, Herrmann also mentions that White Loyalists brought enslaved people with them, still held in bondage. Neither Dunmore’s nor the Philipsburg proclamations freed people held in bondage by Loyalists, and yet they get only a brief mention. Her chapters on Indigenous-European relations are extremely useful for other historians researching the period, but would have been improved with additional context on land use in relation to food. Herrmann often references famine, food diplomacy, and victual warfare in these chapters, without addressing the impact of land grabs and disease on the ability of Indigenous groups to feed themselves. She references, but does not fully address the need of European settlers to expand settlement into Indian Country as a motivating factor in war and postwar diplomacy. Finally, while the focus of the book is specifically on the roles of Indigenous and Black groups in the context of food and warfare, the omission of victual warfare by British and American troops and militias, especially in “foraging” and destroying foodstuffs of White civilian populations throughout the colonies seems like a missed opportunity to compare and contrast with policies and long-term impacts of victual warfare toward Indigenous groups. In all, this book is a worthy addition to the bookshelves of serious scholars of the American Revolution, especially those interested in Indigenous and Black history of this time period, but it also leaves room for future scholars to examine more closely the issues Herrmann raises. No Useless Mouth: Waging War and Fighting Hunger in the American Revolution, Rachel B. Herrmann. Cornell University Press, 2019. 308 pp., $27.95, paperback, ISBN 978-1501716119. The Food Historian blog is supported by patrons on Patreon! Patrons help keep blog posts like this one free and available to the public. Join us for awesome members-only content like free digitized cookbooks from my personal collection, e-newsletter, and even snail mail from time to time! Don't like Patreon? Leave a tip!

0 Comments

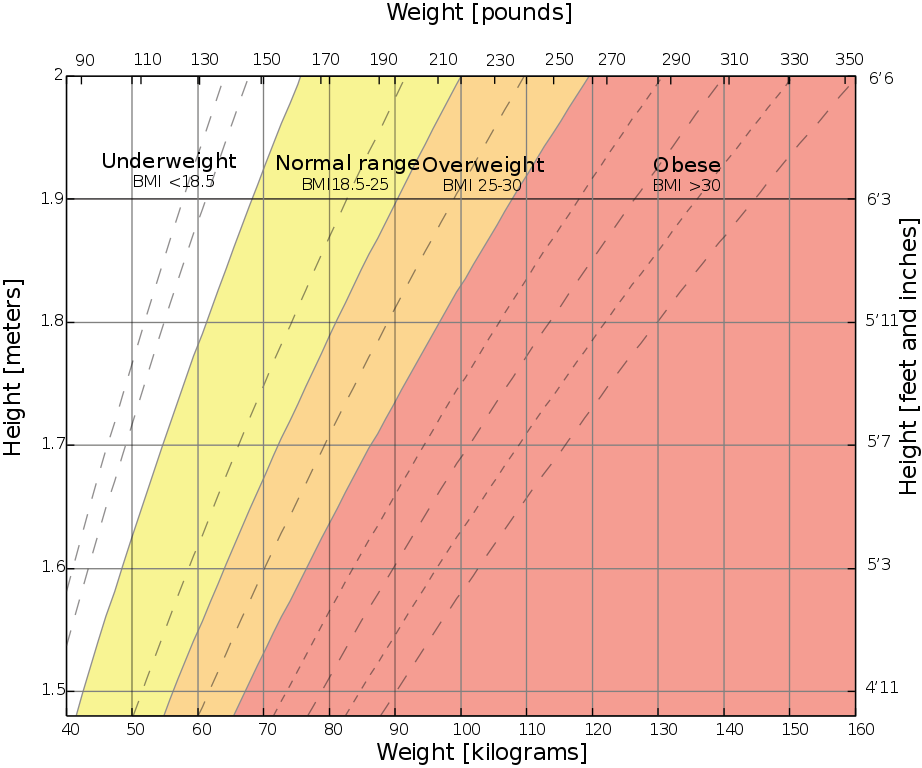

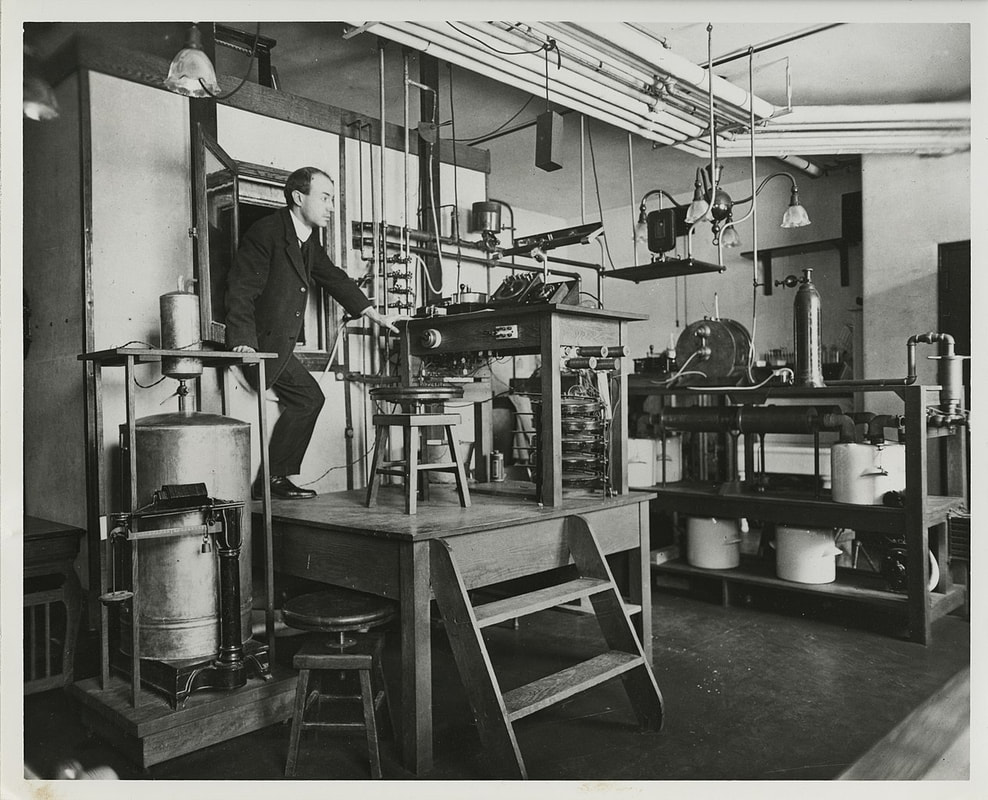

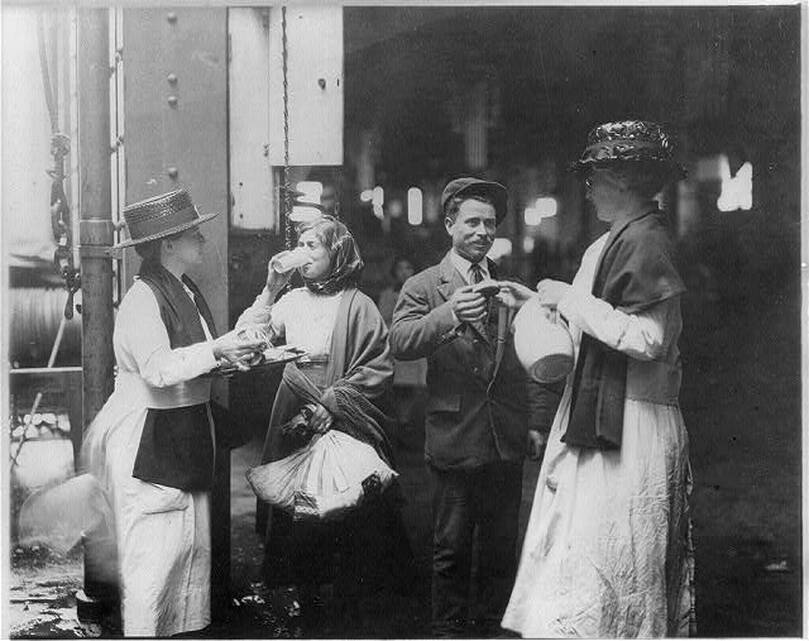

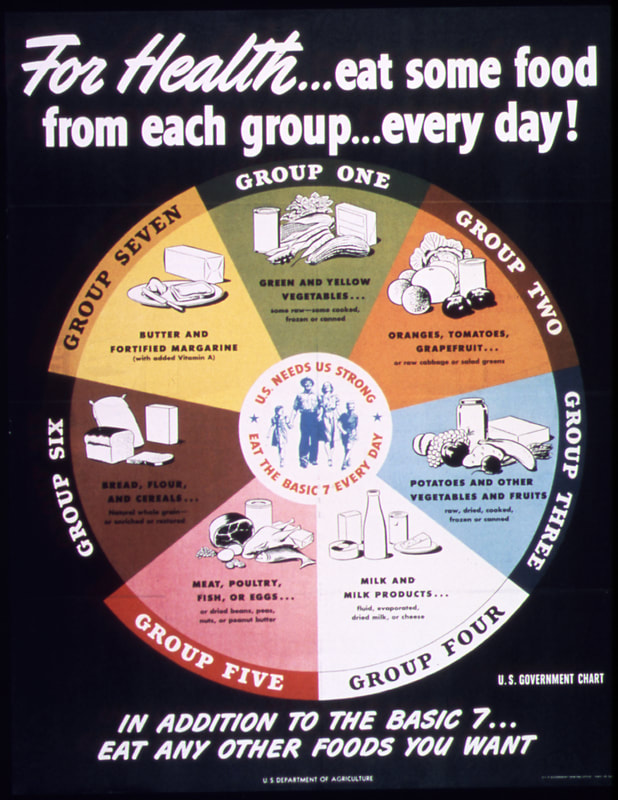

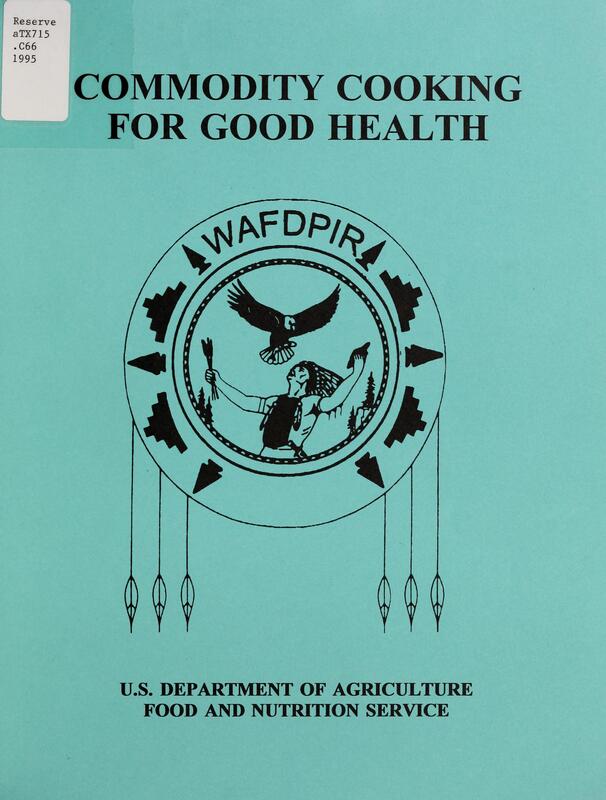

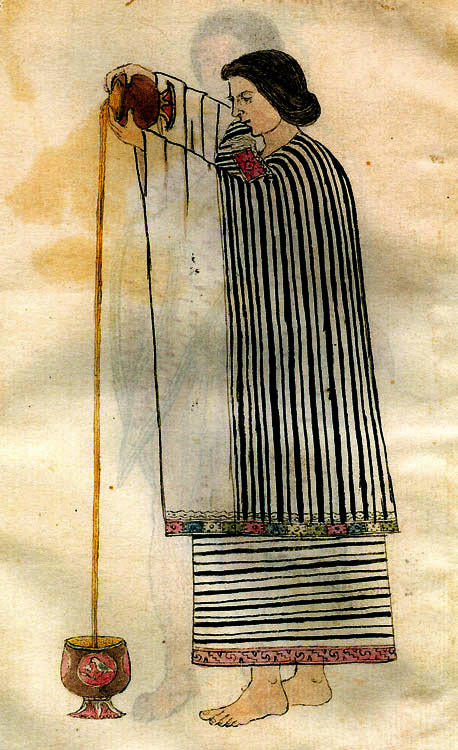

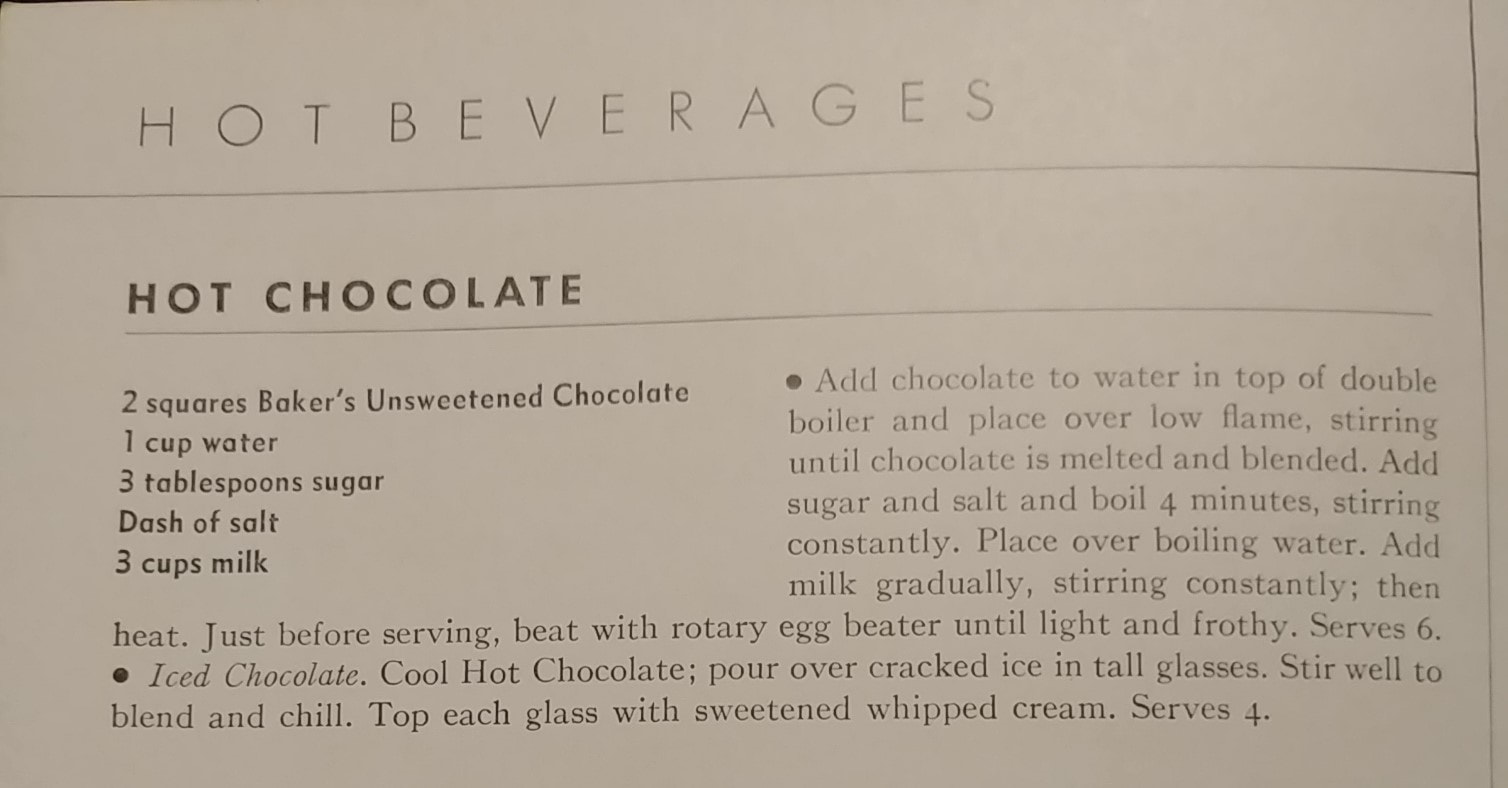

The short answer? At least in the United States? Yes. Let's look at the history and the reasons why. I post a lot of propaganda posters for World War Wednesday, and although it is implied, I don't point out often enough that they are just that - propaganda. They are designed to alter peoples' behavioral patterns using a combination of persuasion, authority, peer pressure, and unrealistic portrayals of culture and society. In the last several months of sharing propaganda posters on social media for World War Wednesday, I've gotten a couple of comments on how much they reflect an exclusively White perspective. Although White Anglo-Saxon Protestant culture was the dominant culture in the United States at the time, it was certainly not the only culture. And its dominance was the result of White supremacy and racism. This is reflected in the nutritional guidelines and nutrition science research of the time. The First World War takes place during the Progressive Era under a president who re-segregated federal workplaces that had been integrated since Reconstruction. It was also a time when eugenics was in full swing, and the burgeoning field of nutrition science was using racism as justifications for everything from encouraging assimilation among immigrant groups by decrying their foodways and promoting White Anglo-Saxon Protestant foodways like "traditional" New England and British foods to encouraging "better babies" to save the "White race" from destruction. Nutrition science research with human subjects used almost exclusively adult White men of middle- and upper-middle class backgrounds - usually in college. Certain foods, like cow's milk, were promoted heavily as health food. Notions of purity and cleanliness also influenced negative attitudes about immigrants, African Americans, and rural Americans. During World War II, Progressive-Era-trained nutritionists and nutrition scientists helped usher in a stereotypically New England idea of what "American" food looked like, helping "kill" already declining regional foodways. Nutrition research, bolstered by War Department funds, helped discover and isolate multiple vitamins during this time period. It's also when the first government nutrition guidelines came out - the Basic 7. Throughout both wars, the propaganda was focused almost exclusively on White, middle- and upper-middle-class Americans. Immigrants and African Americans were the target of some campaigns for changing household habits, usually under the guise of assimilation. African Americans were also the target of agricultural propaganda during WWII. Although there was plenty of overt racism during this time period, including lynching, race massacres, segregation, Jim Crow laws, and more, most of the racism in nutrition, nutrition science, and home economics came in two distinct types - White supremacy (that is, the belief that White Anglo-Saxon Protestant values were superior to every other ethnicity, race, and culture) and unconscious bias. So let's look at some of the foundations of modern nutrition science through these lenses. Early Nutrition ScienceNutrition Science as a field is quite young, especially when compared to other sciences. The first nutrients to be isolated were fats, carbohydrates, and proteins. Fats were the easiest to determine, since fat is visible in animal products and separates easily in liquids like dairy products and plant extracts. The term "protein" was coined in the 1830s. Carbohydrates began to be individually named in the early 19th century, although that term was not coined until the 1860s. Almost immediately, as part of nearly any early nutrition research, was the question of what foods could be substituted "economically" for other foods to feed the poor. This period of nutrition science research coordinated with the Enlightenment and other pushes to discover, through experimentation, the mechanics of the universe. As such, it was largely limited to highly educated, White European men (although even Wikipedia notes criticism of such a Euro-centric approach). As American colleges and universities, especially those driven by the Hatch Act of 1877, expanded into more practical subjects like agriculture, food and nutrition research improved. American scientists were concerned more with practical applications, rather than searching for knowledge for knowledge's sake. They wanted to study plant and animal genetics and nutrition to apply that information on farms. And the study of human nutrition was not only to understand how humans metabolized foods, but also to apply those findings to human health and the economy. But their research was influenced by their own personal biases, conscious and unconscious. The History of Body Mass Index (BMI)Body Mass Index, or BMI, is a result of that same early 19th century time period. It was invented by Belgian mathematician Lambert Adolphe Jacques Quetelet in the 1830s and '40s specifically as a "hack" for determining obesity levels across wide swaths of population, not for individuals. Quetelet was a trained astronomist - the one field where statistical analysis was prevalent. Quetelet used statistics as a research tool, publishing in 1835 a book called Sur l'homme et le développement de ses facultés, ou Essai de physique sociale, the English translation of which is usually called A Treatise on Man and the Development of His Faculties. In it, he discusses the use of statistics to determine averages for humanity (mainly, White European men). BMI became part of that statistical analysis. Quetelet named the index after himself - it wasn't until 1972 that researcher Ancel Keys coined the term "Body Mass Index," and as he did so he complained that it was no better or worse than any other relative weight index. Quetelet's work went on to influence several famous people, including Francis Galton, a proponent of social Darwinism and scientific racism who coined the term "eugenics," and Florence Nightingale, who met him in person. As a tool for measuring populations, BMI isn't bad. It can look at statistical height and weight data and give a general idea of the overall health of population. But when it is used as a tool to measure the health of individuals, it becomes extremely flawed and even dangerous. Quetelet had to fudge the math to make the index work, even with broad populations. And his work was based on White European males who he considered "average" and "ideal." Quetelet was not a nutrition scientist or a doctor - this "ideal" was purely subjective, not scientific. Despite numerous calls to abandon its use, the medical community continues to use BMI as a measure of individual health. Because it is a statistical tool not based on actual measures of health, BMI places people with different body types in overweight and obese categories, even if they have relatively low body fat. It can also tell thin people they are healthy, even when other measurements (activity level, nutrition, eating disorders, etc.) are signaling an unhealthy lifestyle. In addition, fatphobia in the medical community (which is also based on outdated ideas, which we'll get to) has vilified subcutaneous fat, which has less impact on overall health and can even improve lifespans. Visceral fat, or the abdominal fat that surrounds your organs, can be more damaging in excess, which is why some scientists and physicians advocate for switching to waist ratio measurements. So how is this racist? Because it was based on White European male averages, it often punishes women and people of color whose genetics do not conform to Quetelet's ideal. For instance, people with higher muscle mass can often be placed in the "overweight" or even "obese" category, simply because BMI uses an overall weight measure and assumes a percentage of it is fat. Tall people and people with broader than "ideal" builds are also not accurately measured. The History of the CalorieAlthough more and more people are moving away from measuring calories as a health indicator, for over 100 years they have reigned as the primary measure of food intake efficiency by nutritionists, doctors, and dieters alike. The calorie is a unit of heat measurement that was originally used to describe the efficiency of steam engines. When Wilbur Olin Atwater began his research into how the human body metabolizes food and produces energy, he used the calorie to measure his findings. His research subjects were the White male students at Wesleyan University, where he was professor. Atwater's research helped popularize the idea of the calorie in broader society, and it became essential learning for nutrition scientists and home economists in the burgeoning field - one of the few scientific avenues of study open to women. Atwater's research helped spur more human trials, usually "Diet Squads" of young middle- and upper-middle-class White men. At the time, many papers and even cookbooks were written about how the working poor could maximize their food budgets for effective nutrition. Socialists and working class unionists alike feared that by calculating the exact number of calories a working man needed to survive, home economists were helping keep working class wages down, by showing that people could live on little or inexpensive food. Calculating the calories of mixed-food dishes like casseroles, stews, pilafs, etc. was deemed too difficult, so "meat and three" meals were emphasized by home economists. Making "American" FoodEfforts to Americanize and assimilate immigrants went into full swing in the late 19th and early 20th centuries as increasing numbers of "undesirable" immigrants from Ireland, southern Italy, Greece, the Middle East, China, Eastern Europe (especially Jews), Russia, etc. poured into American cities. Settlement workers and home economists alike tried to Americanize with varying degrees of sensitivity. Some were outright racist, adopting a eugenics mindset, believing and perpetuating racist ideas about criminology, intelligence, sanitation, and health. Others took a more tempered approach, trying to convince immigrants to give up the few things that reminded them of home - especially food. These often engaged in the not-so-subtle art of substitution. For instance, suggesting that because Italian olive oil and butter were expensive, they should be substituted with margarine. Pasta was also expensive and considered to be of dubious nutritional value - oatmeal and bread were "better." A select few realized that immigrant foodways were often nutritionally equivalent or even superior to the typical American diet. But even they often engaged in the types of advice that suggested substituting familiar ingredients with unfamiliar ones. Old ideas about digestion also influenced food advice. Pickled vegetables, spicy foods, and garlic were all incredibly suspect and scorned - all hallmarks of immigrant foodways and pushcart operators in major American cities. The "American" diet advocated by home economists was highly influenced by Anglo-Saxon and New England ideals - beef, butter, white bread, potatoes, whole cow's milk, and refined white sugar were the nutritional superstars of this cuisine. Cooking foods separately with few sauces (except white sauce) was also a hallmark - the "meat and three" that came to dominate most of the 20th century's food advice. Rooted in English foodways, it was easy for other Northern European immigrants to adopt. Although French haute cuisine was increasingly fashionable from the Gilded Age on, it was considered far out of reach of most Americans. French-style sauces used by middle- and lower-class cooks were often deemed suspect - supposedly disguising spoiled meat. Post-Civil War, Yankee New England foodways were promoted as "American" in an attempt to both define American foodways (which reflected the incredibly diverse ecosystems of the United States and its diverse populations) and to unite the country after the Civil War. Sarah Josepha Hale's promotion of Thanksgiving into a national holiday was a big part of the push to define "American" as White and Anglo-Saxon. This push to "Americanize" foodways also neatly ignores or vilifies Indigenous, Asian-American, and African American foodways. "Soul food," "Chinese," and "Mexican" are derided as unhealthy junk food. In fact, both were built on foundations of fresh, seasonal fruits, vegetables, and whole grains. But as people were removed from land and access to land, the they adapted foodways to reflect what was available and what White society valued - meat, dairy, refined flour, etc. Asian food in particular was adapted to suit White palates. We won't even get into the term "ethnic food" and how it implies that anything branded as such isn't "American" (e.g. White). Divorcing foodways from their originators is also hugely problematic. American food has a big cultural appropriation problem, especially when it comes to "Mexican" and "Asian" foods. As late as the mid-2000s, the USDA website had a recipe for "Oriental salad," although it has since disappeared. Instead, we get "Asian Mango Chicken Wraps," and the ingredients of mango, Napa cabbage, and peanut butter are apparently what make this dish "Asian," rather than any reflection of actual foodways from countries in Asia. Milk - The Perfect FoodCombining both nutrition research of the 19th century and also ideas about purity and sanitation, whole cow's milk was deemed by nutrition scientists and home economists to be "the perfect food" - as it contained proteins, fats, and carbohydrates, all in one package. Despite issues with sanitation throughout the 19th century (milk wasn't regularly pasteurized until the 1920s), milk became a hallmark of nutrition advice throughout the Progressive Era - advice which continues to this day. Throughout the history of nutritional guidelines in the U.S., milk and dairy products have remained a mainstay. But the preponderance of advice about dairy completely ignores that wide swaths of the population are lactose intolerant, and/or did not historically consume dairy the way Europeans did. Indigenous Americans, and many people of African and Asian descent historically did not consume cow's milk and their bodies often do not process it well. This fact has been capitalized upon by both historic and modern racists, as milk as become a symbol of the alt-right. Even today, the USDA nutrition guidelines continue to recommend at least three servings of dairy per day, an amount that can cause long term health problems in communities that do not historically consume large amounts of dairy. Nutrition Guidelines HistoryBecause Anglo-centric foodways were considered uniquely "American" and also the most wholesome, this style of food persisted in government nutritional guidelines. Government-issued food recommendations and recipes began to be released during the First World War and continued during the Great Depression and World War II. These guidelines and advice generally reinforced the dominant White culture as the most desirable. Vitamins were first discovered as part of research into the causes of what would come to be understood as vitamin deficiencies. Scurvy (Vitamin C deficiency), rickets (Vitamin D deficiency), beriberi (Vitamin B1 or thiamine deficiency), and pellagra (Vitamin B2 or niacin deficiency) plagued people around the world in the 19th and early 20th centuries. Vitamin C was the first to be isolated in 1914. The rest followed in the 1930s and '40s. Vitamin fortification took off during World War II. The Basic 7 guidelines were first released during the war and were based on the recent vitamin research. But they also, consciously or not, reinforced white supremacy through food. Confident that they had solved the mystery of the invisible nutrients necessary for human health, American nutrition scientists turned toward reconfiguring them every which way possible. This is the history that gives us Wonder Bread and fortified breakfast cereals and milk. By divorcing vitamins from the foods in which they naturally occur (foods that were often expensive or scarce), nutrition scientists thought they could use equivalents to maintain a healthy diet. As long as people had access to vitamins, carbohydrates, proteins, and fats, it didn't matter how they were delivered. Or so they thought. This policy of reducing foods to their nutrients and divorcing food from tradition, culture, and emotion dates back to the Progressive Era and continues to today, sometimes with disastrous consequences. Commodities & NutritionDivorcing food from culture is one government policy Indigenous people understand well. U.S. treaty violations and land grabs led to the reservation system, which forcibly removed Native people from their traditional homelands, divorcing them from their traditional foodways as well. Post-WWII, the government helped stabilize crop prices by purchasing commodity foods for use in a variety of programs operated by the United States Department of Agriculture (USDA), including the National School Lunch Program, Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children (WIC), and the Food Distribution Program on Indian Reservations (FDPIR) program. For most of these programs, the government purchases surplus agricultural commodities to help stabilize the market and keep prices from falling. It then distributes the foods to low-income groups as a form of food assistance. Commodity foods distributed through the FDPIR program were generally canned and highly processed - high in fat, salt, and sugar and low in nutrients. This forced reliance on commodity foods combined with generational trauma and poverty led to widespread health disparities among Indigenous groups, including diabetes and obesity. Which is why I was appalled to find this cookbook the other day. Commodity Cooking for Good Health, published by the USDA in 1995 (1995!) is a joke, but it illustrates how pervasive and long-lasting the false equivalency of vitamins and calories can be. The cookbook starts with an outline of the 1992 Food Pyramid, whose base rests on bread, pasta, cereal, and rice. It then goes to outline how many servings of each group Indigenous people should be eating, listing 2-3 servings a day for the dairy category, but then listing only nonfat dry milk, evaporated milk, and processed cheese as the dairy options. In the fruit group, it lists five different fruit juices as servings of fruit. It has a whole chapter on diabetes and weight loss as well as encouraging people to count calories. With the exception of a recipe for fry bread, one for chili, and one for Tohono O'odham corn bread, the remainder of the recipes are extremely European. Even the "Mesa Grande Baked Potatoes" are not, as one would assume from the title, a fun take on baked whole potatoes, but rather a mixture of dehydrated mashed potato flakes, dried onion soup mix, evaporated milk, and cheese. You can read the whole cookbook for yourself, but the fact of the matter is that the USDA is largely responsible for poor health on reservations, not only because it provides the unhealthy commodity foods, but also because it was founded in 1862, the height of the Indian Wars, during attempts by the federal government at genocide and successful land grabs. Although the Bureau of Indian Affairs (BIA) under the Department of the Interior was largely responsible for the reservation system, the land grant agricultural college system started by the Hatch Act was literally built on the sale of stolen land. In addition, the USDA has a long history of dispossessing Black farmers, an issue that continues to this day through the denial of farm loans. Thanks to redlining, people of color, especially Black people, often live in segregated school districts whose property taxes are inadequate to cover expenses. Many children who attend these schools are low-income, and rely on free or reduced lunch delivered through the National School Lunch Program, which has been used for decades to prop up commodity agriculture. Although school lunch nutrition efforts have improved in recent years, many hot lunches still rely on surplus commodities and provide inadequate nutrition. Issues That PersistEven today, the federal nutrition guidelines, administered by the USDA, emphasize "meat and three" style meals accompanied by dairy. And while the recipe section is diversifying, it is still all-too-often full of Americanized versions of "ethnic" dishes. Many of the dishes are still very meat- and dairy-centric, and short on fresh fruits and vegetables. Some recipes, like this one, seem straight out of 1956. The idea that traditional ingredients should be replaced with "healthy" variations, for instance always replacing white rice with brown rice or, more recently cauliflower rice, continues. Many nutritionists also push the Mediterranean Diet as the healthiest in the world, when in fact it is very similar to other traditional diets around the world where people have access to plenty of unsaturated fats, fruits and vegetables, whole grains, lean meats, etc. Even the name - the "Mediterranean Diet," implies the diets of everyone living along the Mediterranean. So why does "Mediterranean" always mean Italian and Greek food, and never Persian, Egyptian, or Tunisian food? (Hint: the answer is racism). Old ideas about nutrition, including emphasis on low-fat foods, "meat and three" style recipes, replacement ingredients (usually poor cauliflower), and artificial sweeteners for diabetics, seem hard to shake for many people. Doctors receive very little training in nutrition and hospital food is horrific, as I saw when my father-in-law was hospitalized for several weeks in 2019. As a diabetic with problems swallowing, pancakes with sugar-free syrup, sugar-free gelatin and pudding, and not much else were their solution to his needs. The modern field of nutritionists is also overwhelmingly White, and racism persists, even towards trained nutritionists of color, much less communities of color struggling with health issues caused by generational trauma, food deserts, poverty, and overwork. Our modern food system has huge structural issues that continue to today. Why is the USDA, which is in charge of promoting agriculture at home and abroad, in charge of federal nutrition programs? Commodity food programs turn vulnerable people into handy props for industrial agriculture and the economy, rather than actually helping vulnerable people. Federal crop subsidies, insurance, and rules assigns way more value to commodity crops than fruits and vegetables. This government support also makes it easy and cheap for food processors to create ultra-processed, shelf-stable, calorie-dense foods for very little money - often for less than the crops cost to produce. This makes it far cheaper for people to eat ultra-processed foods than fresh fruits and vegetables. The federal government also gives money to agriculture promotion organizations that use federal funds to influence American consumers through advertising (remember the "Got Milk?" or "The Incredible, Edible Egg" marketing? That was your taxpayer dollars at work), regardless of whether or not the foods are actually good for Americans. Nutrition science as a field has a serious study replication problem, and an even more serious communications problem. Although scientists themselves usually do not make outrageous claims about their findings, the fact that food is such an essential part of everyday life, and the fact that so many Americans are unsure of what is "healthy" and what isn't, means that the media often capitalizes on new studies to make over-simplified announcements to drive viewership. Key TakeawaysNutrition science IS a science, and new discoveries are being made everyday. But the field as a whole needs to recognize and address the flawed scientific studies and methods of the past, including their racism - conscious or unconscious. Nutrition scientists are expanding their research into the many variables that challenge the research of the Progressive Era, including gut health, environmental factors, and even genetics. But human research is expensive, and test subjects rarely diverse. Nutrition science has a particularly bad study replication problem. If the government wants to get serious about nutrition, it needs to invest in new research with diverse subjects beyond the flawed one-size-fits-all rhetoric. The field of nutrition - including scientists, medical professionals, public health officials, and dieticians - need to get serious about addressing racism in the field. Both their own personal biases, as well as broader institutional and cultural ones. Anyone who is promoting "healthy" foods needs to think long and hard about who their audience is, how they're communicating, and what foods they're branding as "unhealthy" and why. We also need to address the systemic issues in our food system, including agriculture, food processing, subsidies, and more. In particular, the government agencies in charge of nutrition advice and food assistance need to think long and hard about the role of the federal government in promoting human health and what the priorities REALLY are - human health? or the economy? There is no "one size fits all" recommendation for human health. Ever. Especially not when it comes to food. Because nutrition guidelines have problems not just with racism, but also with ableism and economics. Not everyone can digest "healthy" foods, either due to medical issues or medication. Not everyone can get adequate exercise, due to physical, mental, or even economic issues. And I would argue that most Americans are not able to afford the quality and quantity of food they need to be "healthy" by government standards. And that's wrong. Like with human health, there are no easy solutions to these problems. But recognizing that there is a problem is the first step on the path to fixing them. Further ReadingMany of these were cited in the text of the article above, but they are organized here for clarity. I have organized them based on the topics listed above. (note: any books listed below are linked as part of the Amazon Affiliate program - any purchases made from those links will help support The Food Historian's free public articles like this one). EARLY NUTRITION SCIENCE

A HISTORY OF BODY MASS INDEX (BMI)

THE HISTORY OF THE CALORIE

MAKING "AMERICAN" FOOD

MILK - THE PERFECT FOOD

NUTRITION GUIDELINES HISTORY

COMMODITIES AND NUTRITION

ISSUES THAT PERSIST

The Food Historian blog is supported by patrons on Patreon! Patrons help keep blog posts like this one free and available to the public. Join us for awesome members-only content like free digitized cookbooks from my personal collection, e-newsletter, and even snail mail from time to time! Don't like Patreon? Leave a tip!

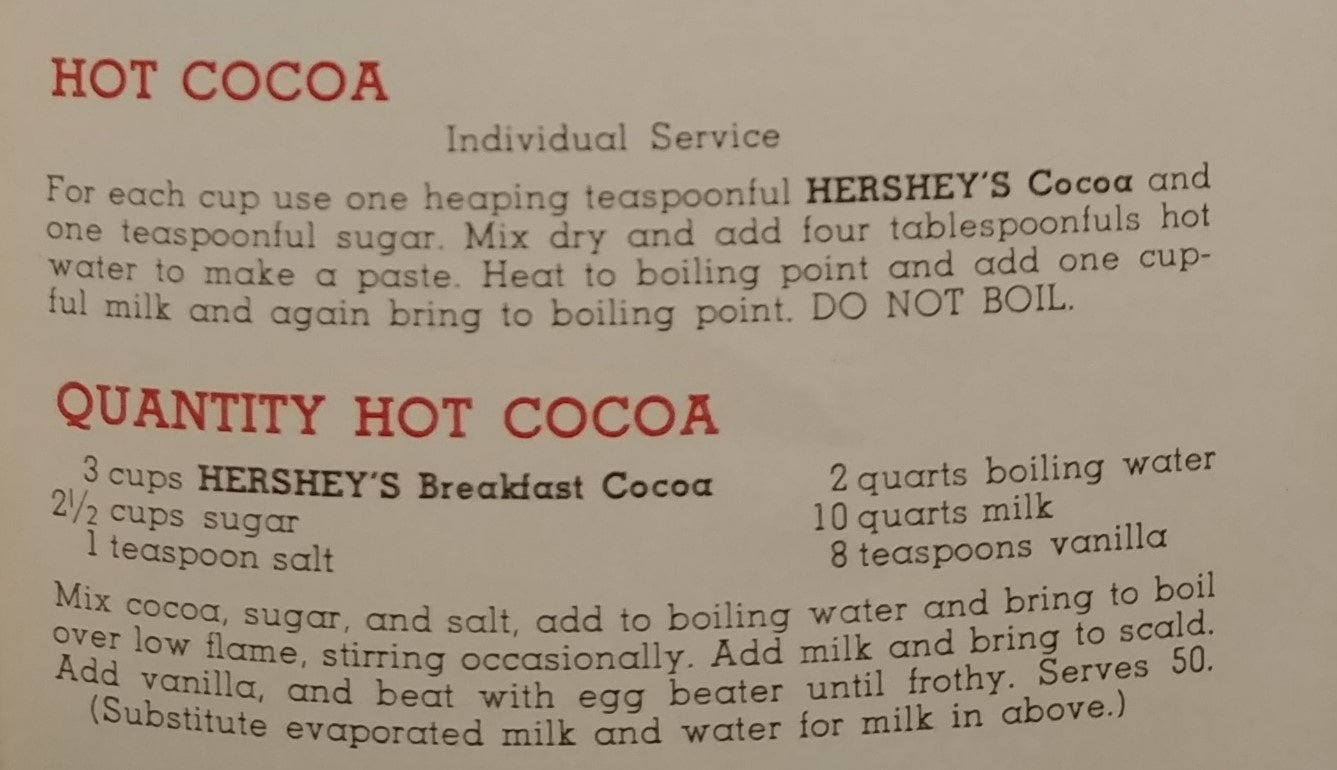

This month has been all about pumpkins and Thanksgiving, chez Food Historian. I have done my "As American as Pumpkin Pie" talk several times in the last few weeks. If you missed it, you can catch a recording, and the recipe for Lydia Maria Child's 1832 Pumpkin Pie here. I've also been doing a lot of media interviews about Thanksgiving, including for National Geographic and USA Today. And of course, my goal is always to try to debunk the mythology of the 19th century concept of Thanksgiving, which is rooted, wittingly or not, in white supremacy, Christian supremacy, and the supremacy of New England culture. Food historian Andrew F. Smith in the Association for the Study of Food and Culture Facebook page posted earlier this week about Thanksgiving. He writes: Sorry to report that the "Pilgrims" had nothing to do with Thanksgiving; it's all a made up story. Days of thanksgiving were frequently celebrated in colonial America– particularly in New England. These thanksgivings were usually declared in response to local events, such as surviving a long trip, military victories, good harvests, or providential rainfalls. These were solemn religious occasions spent in prayer, and little evidence has surfaced suggesting that a formal meal was part of the thanksgiving observance: only two records mention food, and they’re unusual. Thanksgiving dinners were well established by the American War for Independence (1776-1783). To celebrate the victory at Saratoga in 1777, the Continental Congress declared a day of thanksgiving. Joseph Plumb Martin, a soldier, noted in his journal that for this celebration, “Each man was given half a gill of rice and a tablespoonful of vinegar.” More sumptuous fare appeared in 1779 descriptions of thanksgiving meals. In one, a goose was served; in the other, venison, goose and pigeons were served along with a plethora of side dishes and deserts. In New England, the thanksgiving dinner became particularly significant event by the late eighteenth century. A participant in a 1784 thanksgiving meal in Norwich, Connecticut, proclaimed: “What a sight of pigs and geese and turkeys and fowls and sheep must be slaughtered to gratify the voraciousness of a single day.” William Bentley, the pastor of the East Church in Salem, Massachusetts, reported in 1806, that, “A Thanksgiving is not complete without a turkey. It is rare to find any other dishes but such as turkies & fowls afford before the pastry on such days & puddings are much less used than formerly.” Bentley’s description suggests that a two-course meal —the first consisting of turkey and perhaps other meat dishes, and the second, of dessert. This pattern was common during the early nineteenth century and these traditions were long maintained. The first association between the Pilgrims and thanksgiving appeared in 1841, when Alexander Young published a copy of a letter written by Edward Winslow, dated December 11, 1621, to a friend in England. It described a three-day fall event, the dates of which were not cited. In this letter, Winslow writes: Our harvest being gotten in, our Governor sent four men on fowling, that so we might after a more special manner re[j]oice together, after we had gathered the fruit of our labours. They four in one day k[i]lled as much fowl as, with a little help besides, served the Company almost a week. At which time, amongst other recreations, we exercised our arms, many of the Indians coming amongst us, and amongst the rest their greatest king, Massasoit with some 90 men, whom for three days we entertained and feasted. And they went out and killed five deer which they brought to the plantation and bestowed on our Governor and upon the Captain and others. You will note that there is NO statement that this was a “thanksgiving.” In a footnote to the 1841 reprint of the letter, Alexander Young claimed that the event described by Winslow “was the first thanksgiving, the harvest festival of New England. On this occasion they no doubt feasted on the wild turkey as well as venison.” However, Winslow did not use the word thanksgiving to describe this or any other event in the fall of 1621. The Puritans made no subsequent mention of this event and it was not remembered or observed in later years by the Pilgrims or Puritans. The feast described by Winslow makes no mention of prayer and it does include many secular elements: the Puritans would not have considered this a thanksgiving. However, the idea that the 1621 event at Plimoth Plantation was the “First Thanksgiving” was picked up by others, and by the mid-nineteenth century it was generally believed in New England that the Pilgrims had invented thanksgiving in America. Of course, Jamestown, settled in 1607, observed many days of thanksgiving years before the Pilgrims landed at Plimoth Plantation, and a plaque in Jamestown marks the purported site of the real “First Thanksgiving,” but factual knowledge was unable to stop the fakelore of the Pilgrim connection with thanksgiving from spreading. The driving force behind making thanksgiving a national holiday in the United States was Sarah Josepha Hale, the editor of Godey’s Lady’s Book. Hale commenced her campaign to create a national thanksgiving holiday in 1846. For the next seventeen years, she wrote annually to members of Congress, prominent individuals, and the governors of every state and territory, requesting each to proclaim a common thanksgiving day. In an age before word processors, typewriters, or mass media, this was a difficult campaign to wage. Hale believed that a thanksgiving holiday would help bind the United States together. She came close to success in 1859 when thirty states and three territories observed thanksgiving on the third Thursday of November. During the Civil War, she was unable to communicate with many Southern states, so rather then request each state, she approach President Lincoln, asking for thanksgiving to be designated a national holiday. A few months after the North’s military victories at Gettysburg and Vicksburg in 1863, Hale achieved success: Lincoln declared the last Thursday in November a national day of thanksgiving, and the holiday has been celebrate ever since in the United States. Smith outlines a good argument. Days of thanksgiving were common throughout early American history, could be declared at any time of year, and were usually not associated with feasting. When they were, it was often after the fall harvest, as the "original" 1621 version. Harvest feasts are very English, so it makes sense that the Separatists (what the Pilgrims were actually called) would celebrate a successful harvest after so devastating a winter with a feast. Harvest Home, or Ingathering, is an ancient tradition in the British Isles. It also makes sense that traditionally British foodways, such as eating sour fruits with wild game birds (turkey and cranberry sauce, anyone?), pies, gravy, and mashed root vegetables, would make their way onto New England harvest dinner tables. But days of thanksgiving were also declared for far darker reasons, including the "victory" in May, 1637 known today as the Pequot Massacre. The idea that our modern Thanksgiving stems from the celebration of that massacre is making the rounds of the internet lately, and while the connection is not direct, it's not as indirect as Snopes makes it out to be. Although, as Smith notes, Sarah Josepha Hale was the driving force behind our modern celebrations, whatever her intentions, the subtext of a distinctly British, New England tradition being sanctified by national authority to be celebrated throughout the land definitely fit with the driving cultural force of the 19th century - that White, Protestant, Yankee/English culture was superior to all others. It's no surprise that Thanksgiving finally became a national holiday in 1863 - the midst of the American Civil War. It's also no surprise that the mythology of the peaceful, helpful Indians was becoming part of our national conversation just as millions of Indigenous people were being forcibly removed from their lands and treaties violated right and left by the federal government notably during the "Plains Wars" of the mid and late 19th century. The Great Plains were some of the last areas of the United States to be colonized by Europeans, and so their Indigenous peoples were some of the last to be forcibly removed. It's also why most portrayals of Indians in Thanksgiving imagery depict them in the garb of Northern Plains Indians, which is substantially different from how Native peoples in the Northeast dressed historically.  This c. 1920 postcard is a classic example of how Thanksgiving mythology is perpetuated. A "Pilgrim" (They didn't dress like that either) sits with his gun over a freshly killed turkey. In the background, a giant pumpkin pie halos him. Behind the pumpkin, lurks a Native man dressed in Plains Indian clothing, his intentions unknown. By framing Indigenous people as complicit in their own destruction, Europeans could justify land theft (they weren't "using" it anyway!), genocide ("Kill the Indian, save the man"), and breaking countless treaties that legally have the same standing as the Constitution (you can't stop progress!). This is also why, for many Indigenous people, Thanksgiving is a day of mourning. A lot of people still celebrate Thanksgiving, and since the holiday in the modern era is much more focused on food and family, I think that's a good thing. However, it's important to understand what Thanksgiving myths are out there and why and to not perpetuated them. And it's equally important to support Indigenous people - emotionally, politically, and financially - as we celebrate. If you want to decolonize your Thanksgiving by educating yourself further, check out last year's post with a list of resources. The amazing film Gather is now available on Netflix and is fantastic. It would make a wonderful post-Thanksgiving-dinner watch with friends and family. Taking tangible actions is also important. You can support Indigenous food producers as you plan meals all year round, not just at Thanksgiving. You can support Indigenous people in their efforts to prevent oil and natural gas pipelines from violating treaties and polluting or utterly destroying the last vestiges of important ecological landscapes (which, newsflash, helps the whole planet). You can support the land back movement, which focuses on returning public lands acquired through treaty violations back to Indigenous ownership and/or stewardship. Especially since Indigenous people are generally much better at managing public lands than state and federal organizations. You can donate to legal aid organizations that help Indigenous people and tribes protect their individual and collective rights. And finally, you can push back against stereotypes of Indigenous people and Thanksgiving alike. Like my friend whose kindergartener came home with a Thanksgiving worksheet featuring stereotypical depictions of Pilgrims and Indians, who sent her teacher this amazing resource put together by the Native American Services department of Oklahoma City Public Schools on how to interpret Thanksgiving for children in a way that does not erase Indigenous people or perpetuate harmful myths. American history is messy. And that scares a lot of people. But history is complicated, and by better understanding it, we can better understand how we got to where we are today, and whether or not we should do anything to change or fix it. So this Thanksgiving, don't buy the same old stories you grew up with. They're myths for a reason, and we can challenge those reasons, because they suck. And if you don't want to make a Thanksgiving meal that puts New England foodways on a pedestal, feel free to skip the turkey, cranberry sauce, mashed root vegetables, pumpkin pie, and anything else you don't like but always feel obligated to eat. Make your own traditions, and celebrate your own, local harvest season with foods that reflect your family and your geography, without the guilt. Throw off the tyranny of "tradition." Life's too short for bad meals and bad history. The Food Historian blog is supported by patrons on Patreon! Patrons help keep blog posts like this one free and available to the public. Join us for awesome members-only content like free digitized cookbooks from my personal collection, e-newsletter, and even snail mail from time to time! Don't like Patreon? Join with an annual membership below, or just leave a tip! In the United States, the terms "hot chocolate" and "hot cocoa" are used pretty interchangeably, but they aren't quite the same thing! Hot ChocolateHot chocolate is a truly ancient drink, dating back as many as 3000 years. Developed by ancient Indigenous people in Mesoamerica, the cacao bean was used by the Olmecs and drinking chocolate perfected by the Maya and Aztecs. A mixture of ground roasted cacao beans, spices, including chili peppers and vanilla, sometimes sweetened with honey, and often containing other ingredients, including ground maize and cochineal to color it red, early drinking chocolate was frothed into a foam and consumed as part of religious ceremonies. In the late 16th century, Spanish invaders had brought cocoa beans - and drinking chocolate - back to Spain, where it quickly spread throughout aristocratic Europe. It came to colonial America via Europe in the late 17th century, where cocoa processors started importing direct from Central America and the Caribbean. Hot chocolate became a fashionable breakfast beverage. But how was it made? Processed cocoa beans were fermented in the pulp, then dried, then roasted. Chopped into nibs, they were then stone ground to create a chocolate paste. Mixed with sugar, hot water, and spices, the bitter drink was served with cream and sugar, much like coffee or tea. By the 18th century, cakes of processed chocolate were being produced for transformation into drinking chocolate. In the mid-19th century, cocoa butter and sugar were added to the cacao and through conching and tempering, eating chocolate developed. By the Victorian period, hot chocolate had transformed from a popular adult beverage on par with coffee and tea, to the purview of children. Hot CocoaPart of the shift from breakfast beverage of aristocrats to children's treat had to do with the fact that both cacao and sugar were increasing in production and therefore dropping in price throughout the 19th century. Cocoa production expanded to other equatorial areas besides Mesoamerica and sugar, fueled by slavery and technological advances, also increased in production. The development of cocoa powder in the 1820s helped expand access to chocolate. Cocoa powder is created by melting or pressing the cocoa butter out of the nibs, then drying and grinding the defatted cocoa beans. Lighter weight, more shelf stable, and easier to blend into beverages than drinking chocolate, cocoa powder became the main ingredient in hot cocoa recipes. Most cocoa powder was natural process, like Hershey's, meaning that it was dried and ground after the Broma process of defatting. But some cocoa powders (like Fry's) were Dutched, or created using the Dutch process, which meant that the defatted cocoa nibs were immersed in an alkaline solution to help neutralize some of their natural acidity before being dried and ground. Natural cocoa is reddish brown in color - Dutch process color is a dark grayish brown. So there you have it! The difference between hot chocolate and hot cocoa is that one is made from melted cocoa, usually 100% cacao unsweetened chocolate, and hot cocoa is made from a mixture of cocoa powder and sugar, often cooked into a syrup. But how do you know which one you prefer? Hot chocolate or hot cocoa? Try these historic recipes and find out! Baker's Hot Chocolate Recipe (1936)I made this recipe as part of a talk on hot chocolate history, and while not very sweet, it is very rich and chocolatey. If you are a chocoholic, this is the recipe for you. Please note that you'll need Baker's Unsweetened 100% Cacao Chocolate, and that these days 2 squares is really 2 ounces, or 8 quarter ounce rectangles. 2 squares Baker's Unsweetened Chocolate 1 cup water 3 tablespoons sugar dash of salt 3 cups milk Add chocolate to water in top of double boiler and place over low flame, stirring until chocolate is melted and blended. Add sugar and salt and boil [over direct heat] 4 minutes, stirring constantly [this will boil off most of the water and make a thick syrupy chocolate]. Place over boiling water, add milk gradually, stirring constantly; then heat. Just before serving, beat with rotary egg beater until light and frothy. Serves 6. Hershey's Single Serve Hot Cocoa Recipe (1937)For each cup, use one heaping teaspoonful HERSHEY'S COCOA and one teaspoonful sugar [I used a heaping spoonful, which it needed]. Mix dry and add four tablespoons hot water to make a paste. Heat to boiling point and add one cupful milk and again bring to boiling point. DO NOT BOIL. You can use either natural process or Dutch process cocoa for this one. It is not as thick and rich as the Baker's hot chocolate, but it does have that familiar cocoa taste from childhood and is still quite good. You can always change these recipes to suit your tastes with more sugar or with half and half or part cream, instead of all milk. Top with whipped cream, marshmallows, or try your hand at Indigenous-inspired spices like chili powder, cinnamon, vanilla, etc. You can also substitute almond milk (the most historical substitution, since almond milk was known in 16th century Europe), or any other non-dairy milk. Which do you prefer, hot chocolate or hot cocoa? And how do you like yours prepared? I like mine extra-creamy with whipped cream. Maybe a little peppermint or salted caramel syrup if I'm feeling extra-indulgent. Share your perfect cup in the comments! These recipes are part of a talk with cooking demonstration on the history of hot chocolate I do for public events. For upcoming programs, visit my Event page. The Food Historian blog is supported by patrons on Patreon! Join us for awesome members-only content like free digitized cookbooks from my personal collection, e-newsletter, and even snail mail from time to time! Think about the story of Thanksgiving you grew up with - Pilgrims in black clothes and funny hats and white aprons and shoes with big buckles sitting down to a Thanksgiving dinner with "the Indians," celebrating peace and harmony and the harvest. Maybe you made a construction paper turkey by tracing your hand. Maybe your teacher made Pilgrim hats and bonnets and "Indian headdresses." The focus was on the food and American exceptionalism. The real story is much, much different. "The First Thanksgiving," in 1621 was preceded and followed by violence. Indigenous voices and the role of the Wampanoag people in literally saving the lives of the English separatists (they didn't call themselves "Pilgrims") have been purposefully erased. The legacy of Indigenous foods - cultivated and created by Indigenous people - has also been largely erased from our cultural lexicon. So what can we do about it? This year, you can decolonize your Thanksgiving by learning the real history behind it and familiarizing yourself with the various Indigenous nations in your own backyard and who played an important role in American history. Today's blog post is essentially going to be a giant collection of articles to read and films to watch. I hope you take the time this weekend to read or watch a few with your family or friends and discuss (especially with your kids) the real story behind the myth. Mythbusting the First Thanksgiving What Really Happened at the 1st Thanksgiving from Voice of America What you learned about the ‘first Thanksgiving’ isn’t true. Here’s the real story - from USA Today via the Cape Cod Times The Real History Of The First Thanksgiving That You Didn’t Learn In School from All That Interesting Everything You Learned About Thanksgiving Is Wrong from the New York Times The Real History Of Thanksgiving Isn't The One You Learned In School—Here's How To Celebrate Smarter from Delish The Myths of the Thanksgiving Story and the Lasting Damage They Imbue from Smithsonian Magazine The true story behind Thanksgiving is a bloody one, and some people say it's time to cancel the holiday from Insider The Thanksgiving Myth Gets a Deeper Look This Year from the New York Times Meet the WampanoagMashpee Wampanoag Tribe The Mashpee Wampanoag Tribe, also known as the People of the First Light, has inhabited present day Massachusetts and Eastern Rhode Island for more than 12,000 years. After an arduous process lasting more than three decades, the Mashpee Wampanoag were re-acknowledged as a federally recognized tribe in 2007. In 2015, the federal government declared 150 acres of land in Mashpee and 170 acres of land in Taunton as the Tribe’s initial reservation, on which the Tribe can exercise its full tribal sovereignty rights. The Mashpee tribe currently has approximately 2,600 enrolled citizens. Learn more >>> Wampanoag History from the Wampanoag Nation 400 Years After the ‘First Thanksgiving,’ the Tribe That Fed the Pilgrims Continues to Fight for Its Land Amid Another Epidemic from Time Magazine In 1621, the Wampanoag Tribe Had Its Own Agenda from The Atlantic “OUR” STORY: 400 Years of Wampanoag History an online exhibit with short documentary films from Plymouth 400. U.S. Appeals Ruling In Mashpee Wampanoag Land Case from WBUR and the Cape Cod Times. Although the Mashpee Wampanoag won their case against the Department of the Interior, which had revoked their federal recognition, the US government is currently appealing that ruling. Hopefully that appeal process will cease in 2021. National Day of MourningThe National Day of Mourning was organized in 1970 in response to a specific event of the suppression of history. This is the 50th anniversary of that event. Here's some background on what led to the creation of the National Day of Mourning from the United American Indians of New England: "In 1970, United American Indians of New England declared US Thanksgiving Day a National Day of Mourning. This came about as a result of the suppression of the truth. Wamsutta, an Aquinnah Wampanoag man, had been asked to speak at a fancy Commonwealth of Massachusetts banquet celebrating the 350th anniversary of the landing of the Pilgrims. He agreed. The organizers of the dinner, using as a pretext the need to prepare a press release, asked for a copy of the speech he planned to deliver. He agreed. Within days Wamsutta was told by a representative of the Department of Commerce and Development that he would not be allowed to give the speech. The reason given was due to the fact that, "...the theme of the anniversary celebration is brotherhood and anything inflammatory would have been out of place." What they were really saying was that in this society, the truth is out of place. "What was it about the speech that got those officials so upset? Wamsutta used as a basis for his remarks one of their own history books - a Pilgrim's account of their first year on Indian land. The book tells of the opening of my ancestor's graves, taking our wheat and bean supplies, and of the selling of my ancestors as slaves for 220 shillings each. Wamsutta was going to tell the truth, but the truth was out of place. "Here is the truth: "The reason they talk about the pilgrims and not an earlier English-speaking colony, Jamestown, is that in Jamestown the circumstances were way too ugly to hold up as an effective national myth. For example, the white settlers in Jamestown turned to cannibalism to survive. Not a very nice story to tell the kids in school. The pilgrims did not find an empty land any more than Columbus "discovered" anything. Every inch of this land is Indian land. The pilgrims (who did not even call themselves pilgrims) did not come here seeking religious freedom; they already had that in Holland. They came here as part of a commercial venture. They introduced sexism, racism, anti-lesbian and gay bigotry, jails, and the class system to these shores. One of the very first things they did when they arrived on Cape Cod -- before they even made it to Plymouth -- was to rob Wampanoag graves at Corn Hill and steal as much of the Indians' winter provisions as they were able to carry. They were no better than any other group of Europeans when it came to their treatment of the Indigenous peoples here. And no, they did not even land at that sacred shrine down the hill called Plymouth Rock, a monument to racism and oppression which we are proud to say we buried in 1995. "The first official "Day of Thanksgiving" was proclaimed in 1637 by Governor Winthrop. He did so to celebrate the safe return of men from Massachusetts who had gone to Mystic, Connecticut to participate in the massacre of over 700 Pequot women, children, and men. "About the only true thing in the whole mythology is that these pitiful European strangers would not have survived their first several years in "New England" were it not for the aid of Wampanoag people. What Native people got in return for this help was genocide, theft of our lands, and never-ending repression. "But back in 1970, the organizers of the fancy state dinner told Wamsutta he could not speak that truth. They would let him speak only if he agreed to deliver a speech that they would provide. Wamsutta refused to have words put into his mouth. Instead of speaking at the dinner, he and many hundreds of other Native people and our supporters from throughout the Americas gathered in Plymouth and observed the first National Day of Mourning. United American Indians of New England have returned to Plymouth every year since to demonstrate against the Pilgrim mythology. "On that first Day of Mourning back in 1970, Plymouth Rock was buried not once, but twice. The Mayflower was boarded and the Union Jack was torn from the mast and replaced with the flag that had flown over liberated Alcatraz Island. The roots of National Day of Mourning have always been firmly embedded in the soil of militant protest." You can learn more about the United American Indians of New England and their mission and watch a livestream of their National Day of Mourning program live from Plymouth here: http://www.uaine.org/ Not all Native Americans celebrate Thanksgiving. Find out why. from the Cape Cod Times. For Native Peoples, Thanksgiving Isn't A Celebration. It's A National Day Of Mourning from WBUR 400 Years After First Thanksgiving, Native Americans Honor 'Day of Mourning' Instead from Newsweek Indigenous Foods & Thanksgiving DinnerYou may recall my catalog of Indigenous foods a few weeks ago. The global impact of Indigenous agriculturalists is a staggering and often overlooked or ignored part of our history. Here are some books, films, and articles you can read to learn more about the impact of Indigenous food on our diet and the struggles of Indigenous chefs and historians to reclaim their food sovereignty. Indigenous Chefs On Traditional Cooking And Their Complicated Relationship With Thanksgiving from Delish Native Americans want to decolonize Thanksgiving with native foods and a proper history lesson KIRO radio Sean Sherman, The Sioux Chef: ‘This Is The Year To Rethink Thanksgiving’ from the Huffington Post This Thanksgiving, Make These Native Recipes From Indigenous Chefs from the Huffington Post 3 Indigenous Chefs Talk About What Thanksgiving Means to Them from Bon Appetit This Thanksgiving, try these recipes for local Native American foods from Kansas City Magazine How to Decolonize Your Thanksgiving Dinner by Vice “We are still alive”: How Native communities grapple with Thanksgiving’s colonial legacy from The Counter Films to Watch this ThanksgivingI cannot recommend the film Gather enough. You can rent it on Vimeo, Amazon Prime, or check their website for free screenings. It's stunningly filmed, it portrays a huge variety of Indigenous voices and stories, and it tells an amazing story of the effort of Indigenous people to reclaim their food sovereignty. Sean Sherman, also known as the Sioux Chef, has done a lot to bring national attention to Indigenous foodways. He's written a book and you can learn more about him on his website. Andi Murphy is the host of the Toasted Sister Podcast: Radio about Native American Food. Well folks if I want to get this done before midnight on Thanksgiving I have to stop, but stay tuned for another post on Indigenous Food Historians You Should Know, which I hope to get up soon. Featuring all kinds of amazing people, stories, books, and even more documentary films. I hope this collection of resources has helped you re-learn your American history and decolonize your Thanksgiving this and every year. As always, The Food Historian blog is supported by patrons on Patreon! Join us for awesome members-only content like free digitized cookbooks from my personal collection, e-newsletter, and even snail mail from time to time!

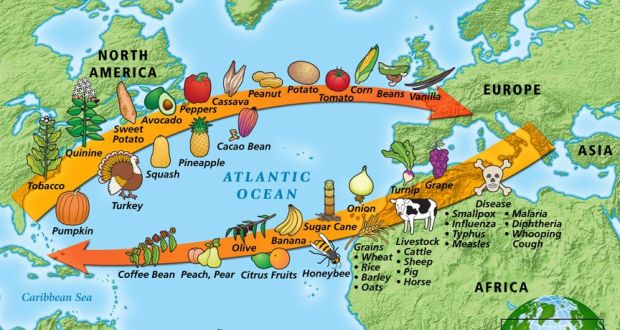

Thanks to everyone who joined us for Episode 23 of the Food History Happy Hour! In this episode, we discussed all things Thanksgiving, including the history of the First Thanksgiving, what foods likely were and were not present at that event, the importance of Indigenous foods in the development of the United States, how to honor Indigenous contributions at Thanksgiving and support Indigenous producers, how Thanksgiving came to be a national holiday, and the origins of many of Thanksgiving's most popular side dishes and desserts.

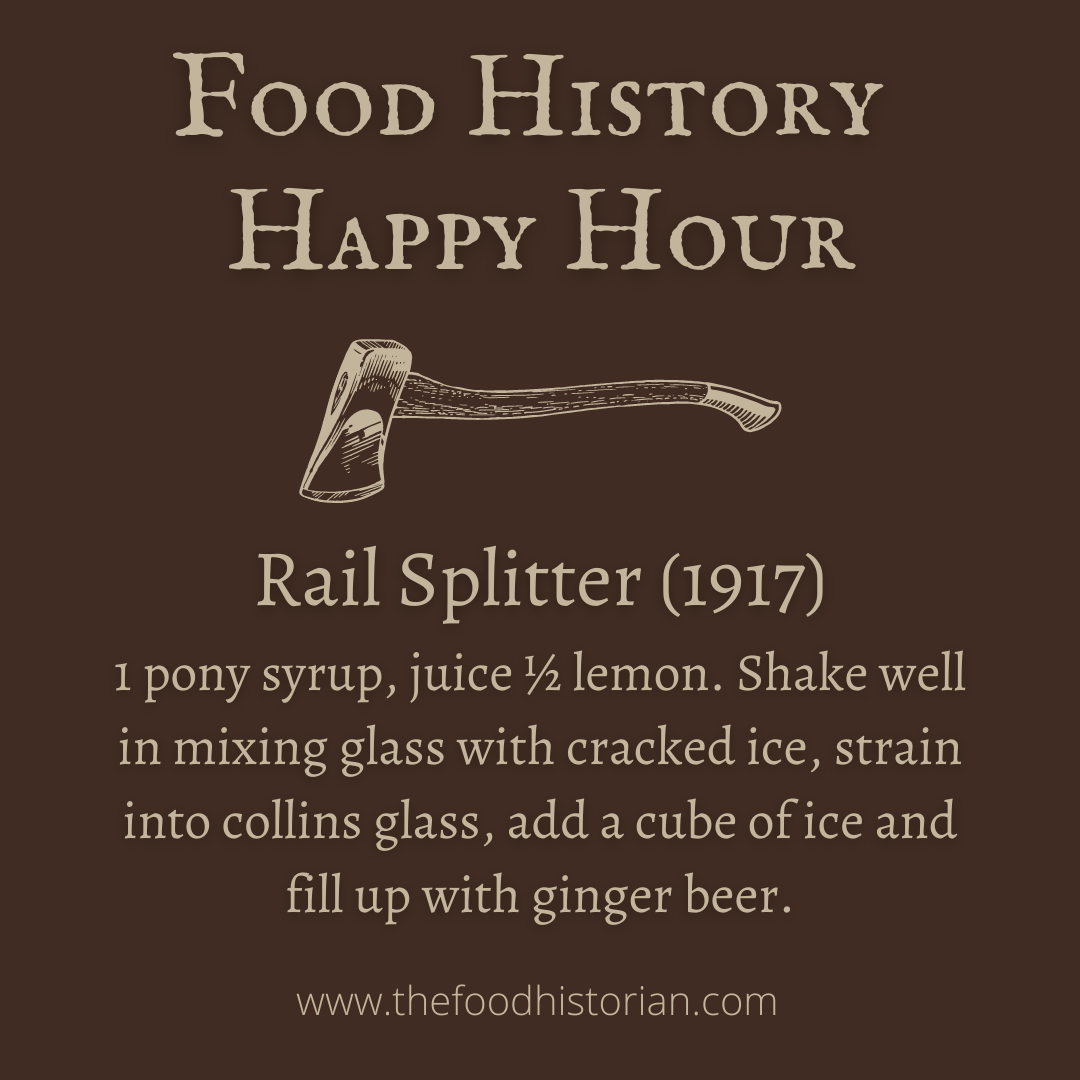

Rail Splitter (1917)

This recipe comes from the 1917 Recipes for Mixed Drinks by Hugo R. Ensslin. The original reads:

1 pony syrup, juice ½ lemon. Shake well in mixing glass with cracked ice, strain into collins glass, add a cube of ice and fill up with ginger beer. I substituted maple syrup for the simple syrup, but boy was that way too much syrup to use with modern ginger ale (I couldn't find ginger beer)! Ginger beer is likely stronger in flavor and less sweet, so go whole hog if you use that, but if you're not a fan of sweet drinks, go easy on the syrup. Episode Links

There are a ton of really great resources out there about Thanksgiving history and Indigenous foodways, but here are a few to whet your appetite:

Decolonizing Thanksgiving

In the episode we talked a little bit about the myths behind Thanksgiving and what it means to modern Indigenous people, but there's a lot more to be done. Here are some ways you can decolonize your own Thanksgiving, regardless of your cultural background.

Food History Happy Hour is supported by patrons on Patreon! Join us for awesome members-only content like free digitized cookbooks from my personal collection, e-newsletter, and even snail mail from time to time!