|

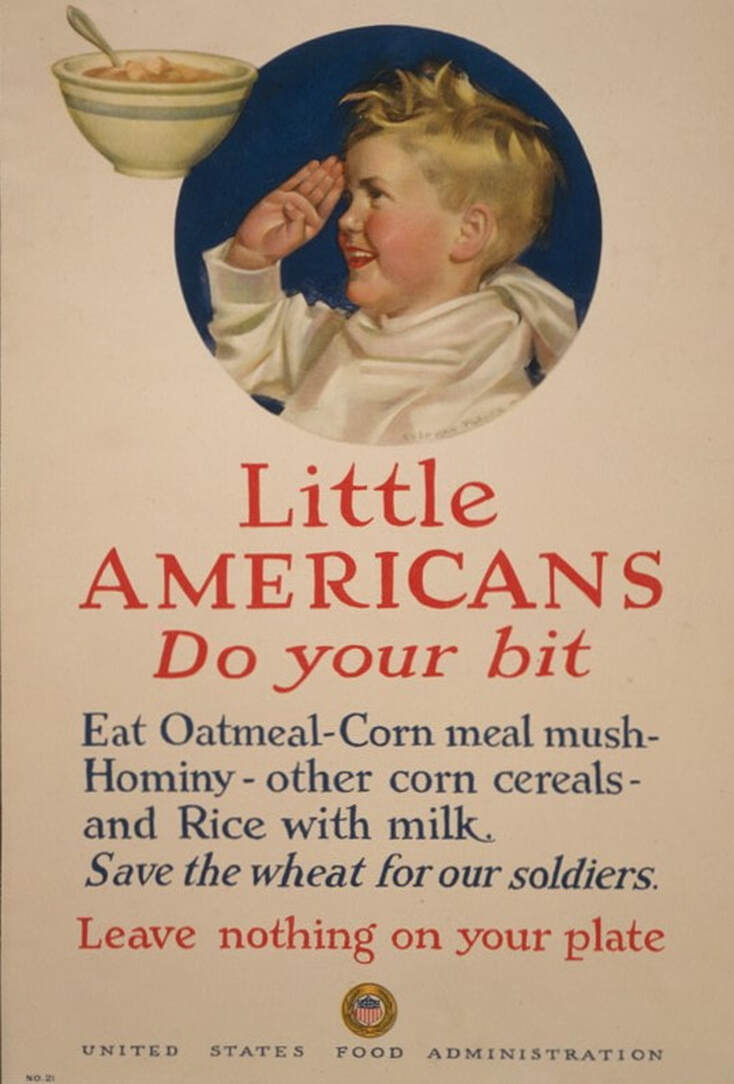

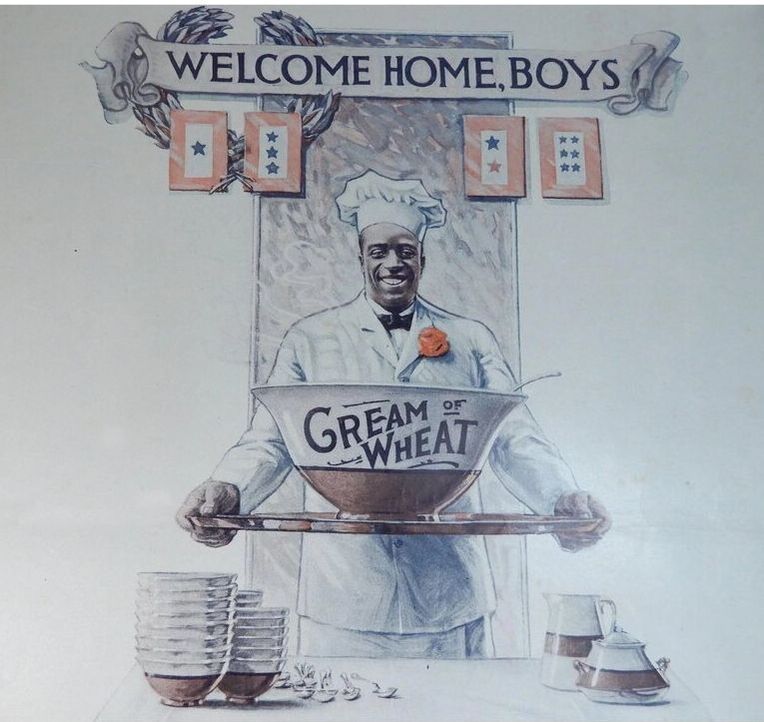

I was interviewed recently about breakfast cereals, especially corn flakes and the Kellogg brothers, so I thought for this week's World War Wednesday we'd take a look at this sweet propaganda poster from the First World War. "Little Americans - Do Your Bit! Eat Oatmeal - Corn meal mush - Hominy - other corn cereals - and Rice with milk. Save the wheat for our soldiers. Leave nothing on your plate" was designed by commercial artist Cushman Parker, who also designed covers featuring cherubic children for the Saturday Evening Post. This poster is interesting because the message is targeted specifically at children. Aside from the school garden movement, there weren't many food-related wartime posters directed to kids - this is one of the only ones. In this poster, a rosy-cheeked blond young man - who looks to be about five or six years old, salutes a floating bowl of hot cereal, a large white napkin tied around his neck as a bib. Although cold breakfast cereals were around at the time of the First World War, they were still considered less nourishing than hot cereals, especially for children. Oatmeal, Cream of Wheat (a.k.a. farina or semolina), and cornmeal or hominy mush were still popular at the breakfast table. Wheat was in short supply during the First World War, so ordinary Americans were encouraged to voluntarily restrict use to free up supplies for American soldiers and the Allies. That meant no more farina! As was true of much of the wartime propaganda, this poster calls for Americans to support the soldiers, doing without so "the boys over there" could have enough. Although Americans only entered the war in the spring of 1917, and it was over by the fall of 1918, wheat supplies continued to tighten throughout the war. By shifting eating habits to focus on other hot cereals, especially oatmeal and corn products like grits, Americans could help "do their bit" for the war effort. Rationing was voluntary for Americans, but Meatless Mondays and Wheatless Wednesdays still came to dominate American daily life. And children were no exception! Although advertising usually targeted the person who did the food shopping (usually the mother), this poster stands out as one targeting children directly, likely to help educate them about the needs of American troops and cut down on potential complaining, which might encourage parents to give into whining and purchase wheat products. The return of wheat, sugar, meat, and fats like butter and lard were a welcome herald to the end of the war. In this 1919 magazine advertisement, Rastus, the racist depiction of an African American cook used by Cream of Wheat packaging and advertisements for over 100 years before finally being removed in the fall of 2020, welcomes home American troops with an enormous bowl of Cream of Wheat - a sign of the end of rationing and likely an attempt to return Cream of Wheat to the tables of Americans who might have gotten used to eating other alternatives. The Food Historian blog is supported by patrons on Patreon! Patrons help keep blog posts like this one free and available to the public. Join us for awesome members-only content like free digitized cookbooks from my personal collection, e-newsletter, and even snail mail from time to time! Don't like Patreon? Leave a tip!

2 Comments

Thanks to everyone who joined in this weeks' Food History Happy Hour! In this episode we made the Guadalcanal Cocktail and discussed rhubarb, abolitionist boycott of sugar and the slave trade, rhubarb recipes and all the animals who are eating my rhubarb, breakfast cereals, in particular GrapeNuts and the real story GrapeNuts ice cream (and its predecessor GrapeNuts pudding), graham flour and graham pudding, Kellogg v. Post cereals (as seen on The Food That Built America), including the history of Granula, the accident of corn flakes, C.W. Post and the California Fig Nut Company, sugary breakfast cereals in the 1950s and on, shredded wheat, the Victorian interest in grain-based products with milk on top, Wheatina, frog eye salad, Cool Whip, rural v. urban breakfast trends, food deserts, housing policy and suburbs, TV and dinners, the addictiveness of sugar, the food pyramid, the history of lunch, including nuncheon, and the introduction of fellow food historian Niel De Marino, who specializes in 18th century foodways and runs The Georgian Kitchen, Russian/Georgian food and cookbooks, Black Panthers, and the reaction to the film "Birth of a Nation."

With a cameo by Sweetie Pie, of course! And I believe this was our longest and most lively Food History Happy Hour yet! Guadalcanal Cocktail

1 jigger bourbon (Old Crow is most accurate)

2-3 ice cubes unsweetened grapefruit juice In an old fashioned glass, pour jigger of bourbon over ice. Fill with grapefruit juice and stir. The REAL Story of Grape Nuts Ice Cream

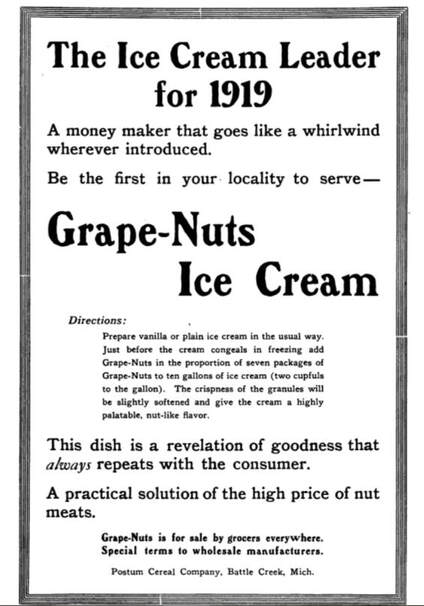

Well as you may know I get a lot of media requests, so one on the origin of Grape Nuts ice cream was fun to research, even if the request was VERY last-minute. Sadly, my commentary on the history did not make the cut of the rather frivolous radio spot (annoying, considering how much work I put into it, all free of charge), but it DID result in some fun research on Grape Nuts ice cream, which was, sadly, NOT invented by Hannah Young in Wolfville, Nova Scotia in 1919, as many people, including her grandson Paul, have claimed. Or at least, Hannah may have come up with the combination independently (although I doubt that could ever be verified), and likely had a hand in popularizing it in Nova Scotia, but I've found references that predate Young by at least 10 years.

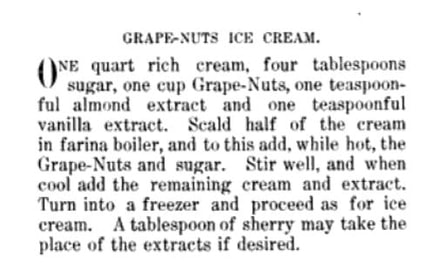

This reference, from the American Housekeeper Advertiser dates to 1909 and is the earliest published reference I could find.

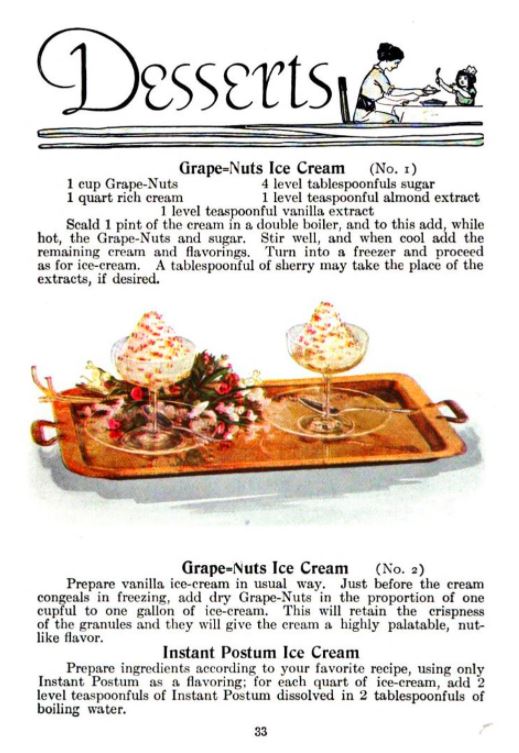

Of course, in 1916, the Post company published, "Good Things to Eat From Wellville."

The first recipe listed in "Good Things to Eat" is very similar to the one from the American Housekeeper Advertiser, but the second is simply vanilla ice cream with Grape Nuts folded in. Also notice with "coffee" flavored Postum ice cream! The cookbook also includes Post Toasties ice cream and several other confection recipes using the cereals. And of course, all these recipes predate the 1919 Hannah Young story.

At any rate - it was a fun research project and I'm glad I was able to add to the historiography of Grape Nuts Ice Cream.

Here's a flurry of other links related to tonight's talk!

If you liked this post and would like to support more Food History Happy Hour livestreams, please consider becoming a member or joining us on Patreon. Members and patrons get special perks like access to members-only content.

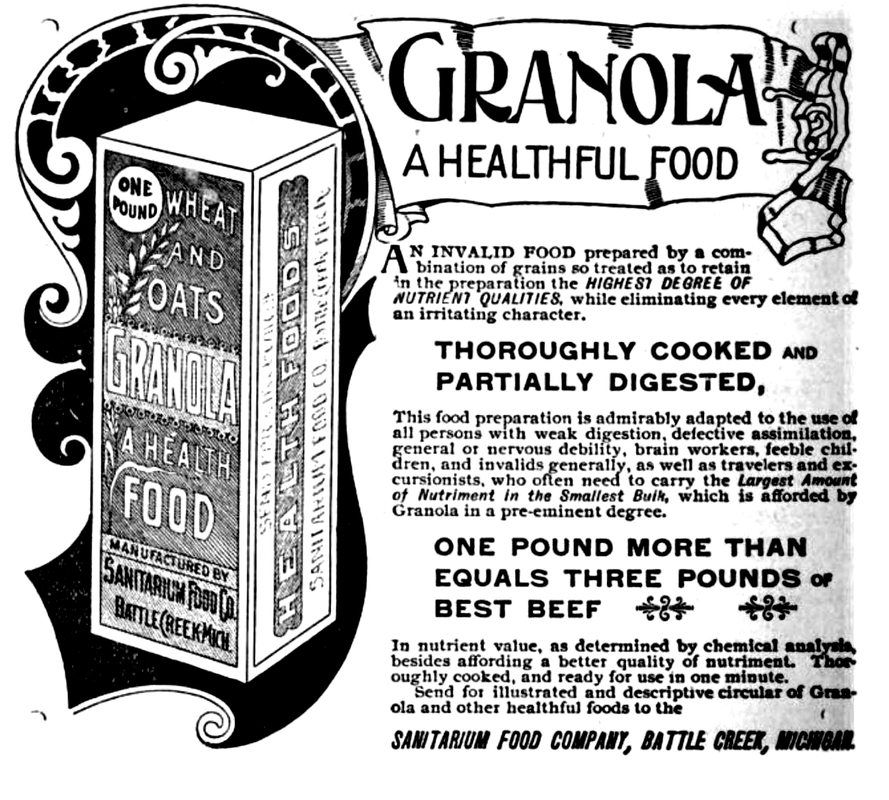

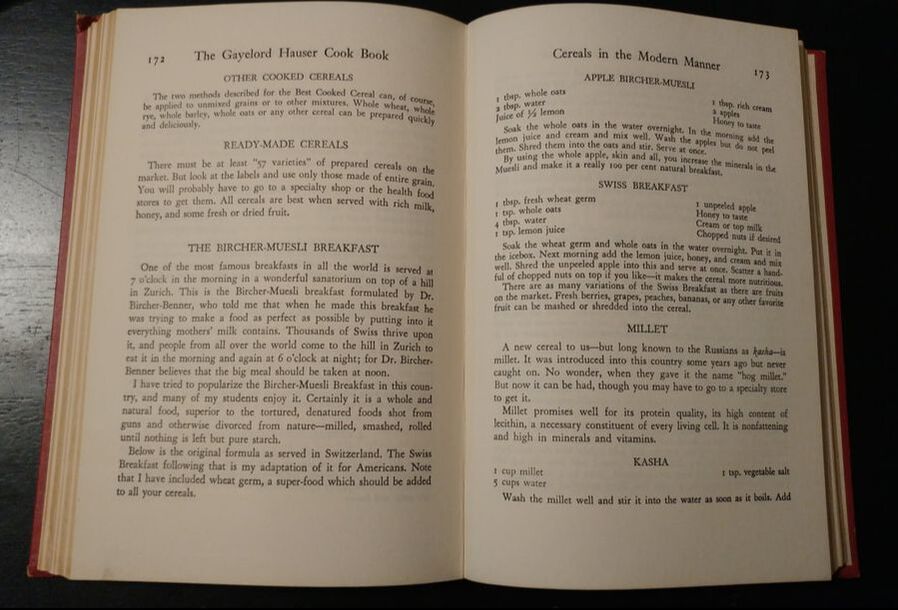

"The Food That Built America" just finished up last night, and I also reached over 200 likes on Facebook! So as a reward to my new friends and faithful followers, I thought I'd take a look at the Kellogg Brothers, who show up in all three episodes. Granola was the cereal that started it all. In the late 1870s, Dr. John Harvey Kellogg used it as part of his health regimen for his sanitarium patients. Based on a twice-baked unleavened bread made of wheat and oat flour, the cereal was then hammered into chunks and soaked in milk before serving. He initially called it "Granula." There was just one problem - there already was a "Granula." This was not covered in the History Channel series, but Kellogg was actually threatened with a lawsuit in 1881 by James Caleb Jackson, of upstate New York. Like Kellogg, Jackson was influenced by Seventh Day Adventist Ellen G. White, who advocated for vegetarianism and other health reforms. But at his hygenic water cure spa in upstate New York, Jackson developed "Granula," based on a twice-baked plain graham flour biscuit (graham flour is un-separated ground whole wheat). He rolled the flour-and-water mixture into sheets, which were baked, then broken into pieces and baked again, and then broken into smaller pieces, similar to the Grape-Nuts that C.W. Post would eventually develop. He invented "Granula" in 1863 - fifteen years before Kellogg. In response to the threat of lawsuit, Kellogg simply changed the name to "Granola." Both Jackson and Kellogg were likely inspired by simple rusks or zwieback or even hardtack. Dating back to ancient times, twice-baked breads were shelf-stable, durable, and long lasting. Hardtack (sometimes called a "cracker" or "ship's biscuit") was a common sight on merchant vessels and naval ships alike and was common soldier fare from the Revolutionary War to the Civil War. Made of just flour, water, and salt, hardtack was, well, hard. It was meant to be softened in coffee, stew, or water before it could be eaten. But its hardness made it the ideal, stable staple for long voyages without refrigeration. Rusks, on the other hand, were more likely to be made with sugar, butter, and eggs and were much closer to our most familiar modern incarnation - biscotti. Some rusks, like zwieback, were even yeast-leavened sweet breads that were twice baked. It stands to reason then, that Kellogg's original "Granola" was a mixture of whole grain wheat flour (graham) and oat flour, mixed with water (no salt or sugar), and twice-baked before crumbling into what would become "cereal." Having made hardtack myself, I can inform you that the trick is in the kneading - as you develop the gluten in the flour it smooths out and becomes easier to work and shape (and roll!). While no known recipe for Kellogg's original "Granola" exists, I did dig up a recipe for "Granula" from the 1906 Inglenook Cookbook, published by the Church of the Brethren, a non-demoninational Christian sect. Apparently hard-baked plain cereals continued their trend of association with religious organizations. You can find more about the Inglenook Cookbook in all its incarnations here. In true, early 20th century style (and like many community-based cookbooks from this time period), the instructions are written in paragraph form. Granula Get good graham flour, take pure spring or soft water, nothing else, and knead to a stiff dough. Roll and mould as for biscuit (not as thick). Bake thoroughly in a hot oven. When well done, or over done, remove and cool, then cut each piece in halves and put back in a warm baker and dry to a crisp, not brown or burnt. A yellow brown will not hurt. Now crush or break in small bits and grind them as you would coffee. You now have one of the best health foods known. It can be served in various ways. Soaked in good, rich milk is the best way to eat it. Some like to add a little sugar, some a little salt (but don't add salt when you bake it, it spoils the flavor). Some eat it with fruit. It makes a nice cold Sunday dish and is always ready. It can be used in puddings and mixed with bread for dressings. We have made and used this hygienic food for 23 years, and know its merits. The biscuits, or graham crackers, warm from the oven, well baked, with crispy crust, make a delightful bread. We have a small hand mill to grind them. If you cannot get good graham flour, if it is too rough with bran, add a little white flour, or sift the coarsest bran out. Graham made of white wheat is best. - Sister Amanda Witmore, McPherson, Kans. While granula and similar incarnations continued to be eaten into the twentieth century, what we know as Granola today is not really a direct descendant of Kellogg's granola (or Jackson's granula). In 1900 a Swiss physician named Dr. Maximillian Bircher-Benner developed another type of grain cereal called Bircher-muesli (later shortened to muesli). Adhering to Bircher-Benner's beliefs that raw foods were the most healthful, muesli primarily contains uncooked rolled oats, with nuts, seeds, and fruits added in. Served plain or with milk, it was originally intended as an accompaniment to meals or a light supper, not breakfast. In 1946, Hollywood health guru Gaylord Hauser published several recipes for "The Bircher-Muesli Breakfast" in his Gaylord Hauser Cookbook. Hauser had studied in Switzerland and was likely heavily influenced by Bircher-Brunner in his own health style, as he often emphasized fresh fruits and vegetables and even juicing. Muesli started to become known among health food enthusiasts after the Second World War, in part thanks to Hauser and others like him who visited Switzerland. Health guru Adelle Davis, however, is credited with introducing what we know today as "granola" to the masses in the 1960s. Although the Adelle Davis Foundation credits her 1947 book Let's Cook It Right with first mentioning granola, I can't find any reference in my copy. In fact, her short chapter on cereals makes no mention of cold, crunchy cereals like granola and contains just one recipe - for how to cook hot cereals (p. 427-439). Adelle is purported to have introduced granola as a snack, but her section on snacks in her introduction to Let's Cook It Right makes no mention of granola - instead suggesting fruit, milk, cheese and crackers, or nuts as good "midmeal" options (p. 17-22). Regardless of how she introduced it, Adelle is likely one of several people to discover that by combining rolled oats with nuts, dried fruit, oil and honey, you get a delicious crunchy baked snack. Her "grandaddy" recipe is below: Adelle Davis’ Grandaddy of Granolas 5 cups rolled oats 1 cup each of chopped almonds, sesame seeds, sunflower seeds, shredded coconut, soy flour, powdered milk (preferably non-instant), and wheat germ. 1 cup warmed honey 1 cup oil, any kind Preheat the oven to 300 degrees. Combine dry ingredients. Combine honey and oil and drizzle over the dry ingredients tossing and coating. Spread the mixture on 2 cookie sheets and bake for 30 to 45 minutes until golden. Makes up to 12 cups, depending what you add or leave out. Eventually, people stopped eating granola out of hand and started pouring milk on top and eating in the morning. Of course, these days, modern granola is far more like Adelle's than Kellogg's (or Jackson's) in that it is heavily sweetened and usually quite fattening. But because of its health guru and sanitarium past and its association with hiking and other outdoor pursuits in the 1960s and '70s, we tend to associate it with healthy food, even though it is anything but. If you'd like to learn more about Gaylord Hauser and Adelle Davis, take a listen to my podcast, History Bites: Full of Pep, the Controversial Quest for a Vitamin-Enriched America, Part 2. So that's the end of my reward post for making it to 200+ likes on Facebook. MaryAnn - are you satisfied? :) I hope you enjoyed this post. If you did, please consider becoming a patron on Patreon to support this and other food history blog posts, podcasts, videos, and more. |

AuthorSarah Wassberg Johnson has an MA in Public History from the University at Albany and studies early 20th century food history. Archives

July 2024

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed