|

Thanks to everyone who joined me for Food History Happy Hour tonight! We talked about the history of diets, dieting, and diet culture, with forays into 19th century religious diets (including Sylvester Graham, Ellen H. White, and John Harvey Kellogg), raw food diets, veganism, changes in fashion influencing ideas about body types, the role of the Gilded Age and Progressive Era and WWI in informing modern ideas about dieting, willpower, and health, the invention of the calorie, the development of dieting and diet fads in the 1930s and '40s, including juicing and the Hollywood diet, we talked about Dr. Norman W. Walker, Gaylord Hauser, Dr. Weston Price, Adele Davis, the role of animal fats in heart disease research, the history of artificial sweeteners, environmental factors in fatness and obesity, and that diet culture is super toxic! I probably could have talked for another hour on this subject, so we can revisit it, if you want to! Let me know in the comments.

We also made a (red) wine spritzer (I thought it was a bottle of white wine, it wasn't) and the history of wine spritzers. Wine Spritzer (19th century)

White wine spritzers are the classically low-calorie bar favorite in the late 20th century United States, but they date back to the early 19th century and are likely associated with the health and spa culture surrounding sparkling mineral waters, but may have also been simply an attempt to make an artificially sparkling wine!

Take your favorite wine - red or white - chilled, and cold club soda or seltzer or sparkling mineral water, also chilled. You can combine them in any ratio, but I think half and half is probably best. Further Reading:

Obviously, I had a blast doing this episode and I think I need to now do some biography blog posts about fad diets and nutritionism and their proponents. Did you know Gaylord Hauser had a TV show? You can alsowatch an interview with Adelle Davis!

The Food Historian blog is supported by patrons on Patreon! Patrons help keep blog posts like this one free and available to the public. Join us for awesome members-only content like free digitized cookbooks from my personal collection, e-newsletter, and even snail mail from time to time!

0 Comments

Some of you may have looked askance at the last episode of Food History Happy Hour where I made (or rather, botched) the 1902 Irish Cocktail. In my defense, it has been a long and rather sleep-deprived spring, and so I let my determination to do the cocktail outweigh my lack of alcohol knowledge, to rather disastrous results. The lesson? You can probably substitute one ingredient in a cocktail, but two or three is a bridge too far. However, Food Historian friend (and Patreon patron!) Anna Katherine is actually an oenologist (that is, a wine scientist) and knows a great deal more about alcohol than I do. She clearly also has a much better stocked liquor cabinet. So she revisited the original recipe much more faithfully, and found the results much better. Here's what she has to say: [A]s a general rule I don't criticize another scholar's work, but after that...er... creation you produced Friday I had Questions. (And a healthy dose of Professional Curiosity.) So- substituting only Pernod for Absinthe, I made the Irish Cocktail. I agree with your estimation of 2oz for a small wine glass, and a dash is a scant 1/4th tsp. I also shook instead of pouring over shaved ice, because I didn't have any- but I compensated by shaking a bit longer than usual to get some melt into the drink, as would happen as you sipped something over shaved ice. The result was perfectly pleasant- a bit boozy, yes, but the dashes of Pernod, curaçao and maraschino added a touch of sweetness that brought out the vanilla notes in the curacao and whiskey, and added some subtle, complex spice around the edges of an otherwise straightforward drink. The lemon peel brought pulled the balance back in so it was focused instead of fat and sweet. Whiskey (made from malt and aged in old barrels) is more subtle and less oaky than bourbon (made from corn and aged in new barrels), so I suspect I had a softer, more integrated, and more balanced tipple than your alcoholic anise Shirley Temple. (I forgot the olive. Dammit.) I never shirk from constructive criticism! Although it must be noted that Anna Katherine did technically substitute Cointreau for curaçao, even though some argue that Cointreau is just a version of curaçao, it is not generally labeled as such in liquor stores, so poor novices like me can't be blamed for buying the blue stuff, okay? ;) Thankfully, we both agreed that the addition of an olive (the original recipe does not indicate ripe, Spanish, or pimento-stuffed) was a strange addition, anyway. You can check the original post for the historic recipe, but Anna Katherine followed it pretty faithfully, except for the substitution of Pernod for the absinthe, which is much-maligned in history, as this excellent article outlines, but which is now "legal" again in the United States, although difficult to find on liquor store shelves. Absinthe, of course, is chartreuse in color, but the recipe contains so little of it one wonders if it would have affected the color of the cocktail at all. Certainly the curaçao would not have been blue at that time, as the best guesses are it was tinted blue starting in the 1920s. Many thanks again to Anna Katherine for taking on the task of trying a more accurate version of the recipe and reporting back the results! Is your liquor cabinet well-stocked enough to try the Irish Cocktail? Do you think the olive would add anything? Let us know in the comments! The Food Historian blog is supported by patrons on Patreon! Patrons help keep blog posts like this one free and available to the public. Join us for awesome members-only content like free digitized cookbooks from my personal collection, e-newsletter, and even snail mail from time to time!

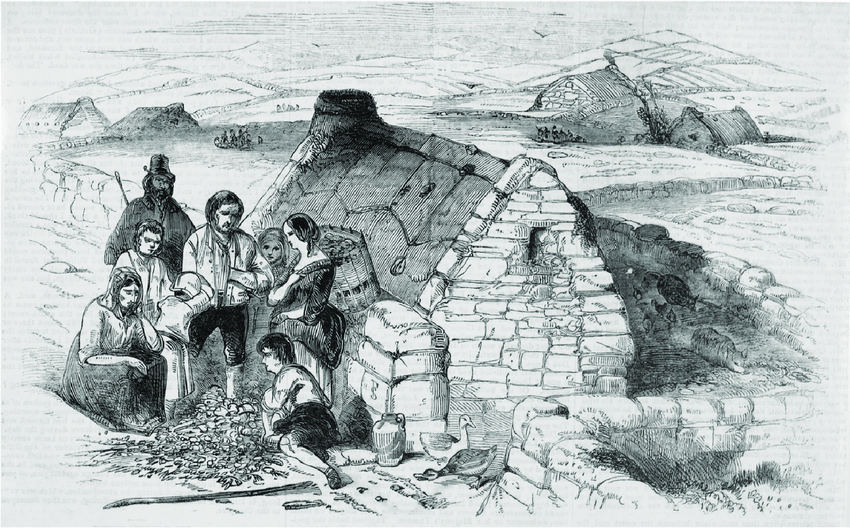

Thanks to everyone who joined me for Food History Happy Hour this month. We talked about all things Irish and food, including the origins of corned beef, Irish soda bread, the Irish Potato Famine, Irish slavery and prejudice, cabbage, brussels sprouts, and the role of brassicas in European and Asian cuisine, and we touched on carageenan or Irish moss pudding, scones and bannocks, Irish coffee, and Irish desserts.

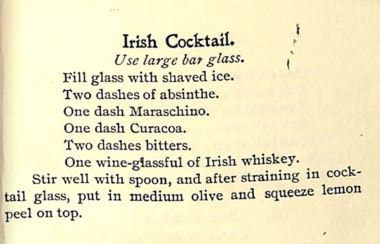

Irish Cocktail (1902)

Tonight's cocktail came from Fox's Bartender's Guide by Richard K. Fox (1902). The 1902 edition was preceded by The Police Gazette Bartender's Guide, first published in 1888, and with a much more interesting cover. Richard K. Fox was the Irish immigrant publisher of The Police Gazette, widely considered the one of the first men's magazines, and which covered tabloid-style sensationalist news, manly (and illegal) sports such as boxing and cockfighting, coverage of vaudeville shows, and "girlie" images of burlesque dancers and other ladies of ill repute.

The cocktail itself is called "Irish" because of the use of Irish whiskey, which also features in several other cocktail recipes. Fox (or whomever was authoring the recipes) seemed rather fond of both absinthe and especially curacao, which feature prominently in most of the cocktail recipes. I won't replicate my version of this recipe as I made a number of substitutes (some knowingly, some out of ignorance) and the end result was not to my taste. Perhaps your version will be better!

Irish Cocktail.

Use large bar glass. Fill glass with shaved ice. Two dashes of absinthe. (or anisette) One dash Maraschino. (the liqueur, not the cherries) One dash Curacoa. (he means Curacao) Two dashes bitters. One wine-glassful of Irish whiskey. (probably 2 ounces) Stir well with spoon, and after straining in cocktail glass, put in medium olive and squeeze lemon peel on top. (a.k.a. a twist of lemon) This cocktail took on a rather unappealing hue, in large part because modern Curacao, an orange-flavored liqueur, is colored bright blue (something that apparently dates to the 1920s). But even historically absinthe was green. Thankfully, Maraschino liqueur is clear. But blue, green, and brown (the whiskey) a muddy-looking cocktail make, so keep that in mind. Episode Sources & Further Reading

The Food Historian blog is supported by patrons on Patreon! Patrons help keep blog posts like this one free and available to the public. Join us for awesome members-only content like free digitized cookbooks from my personal collection, e-newsletter, and even snail mail from time to time!

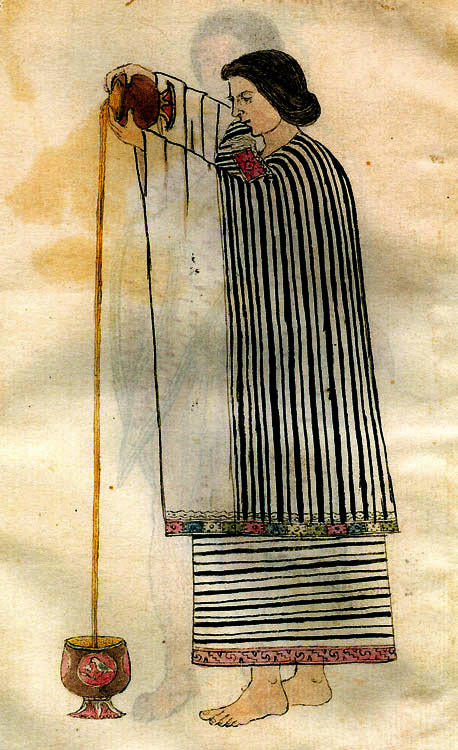

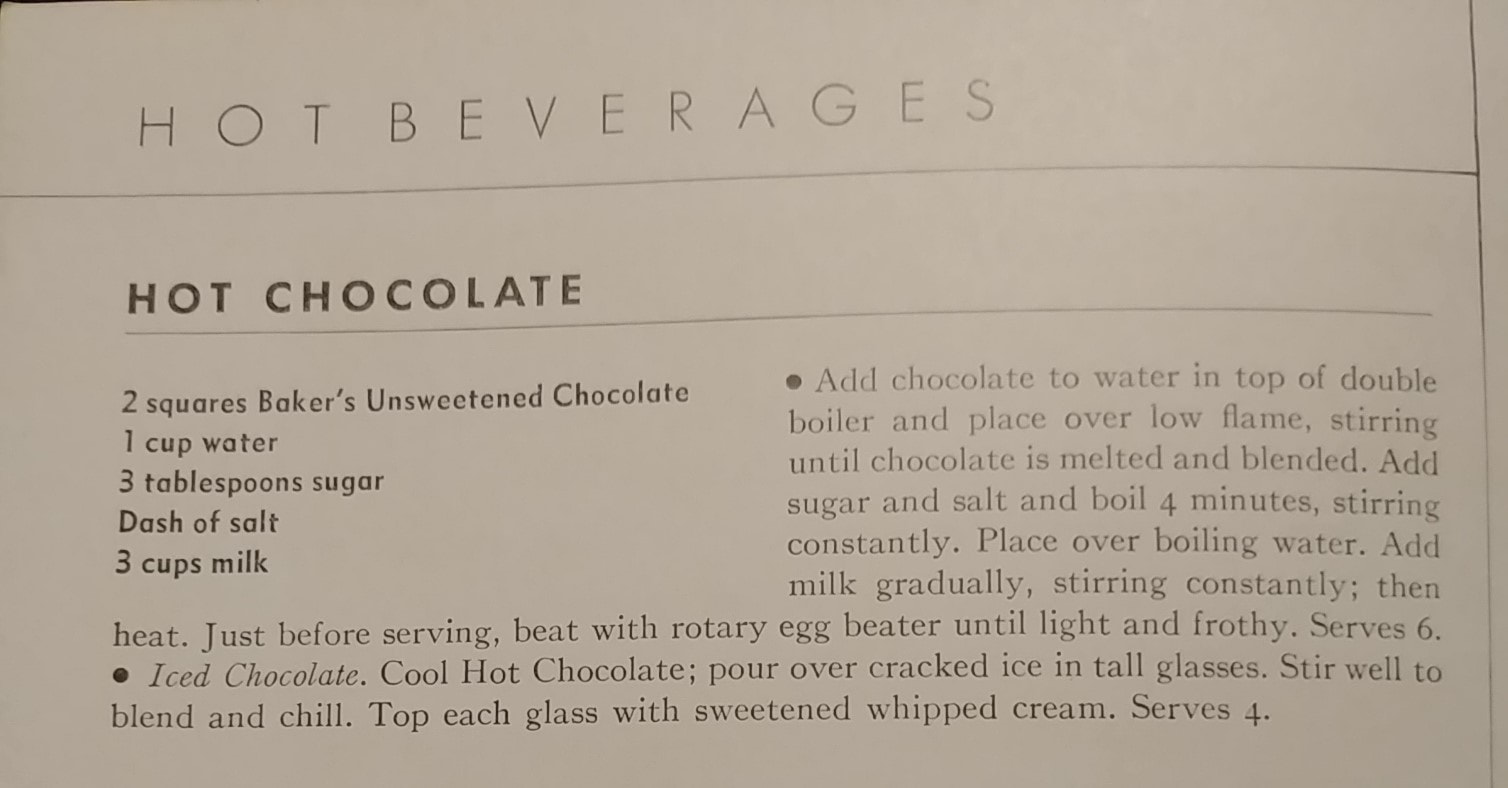

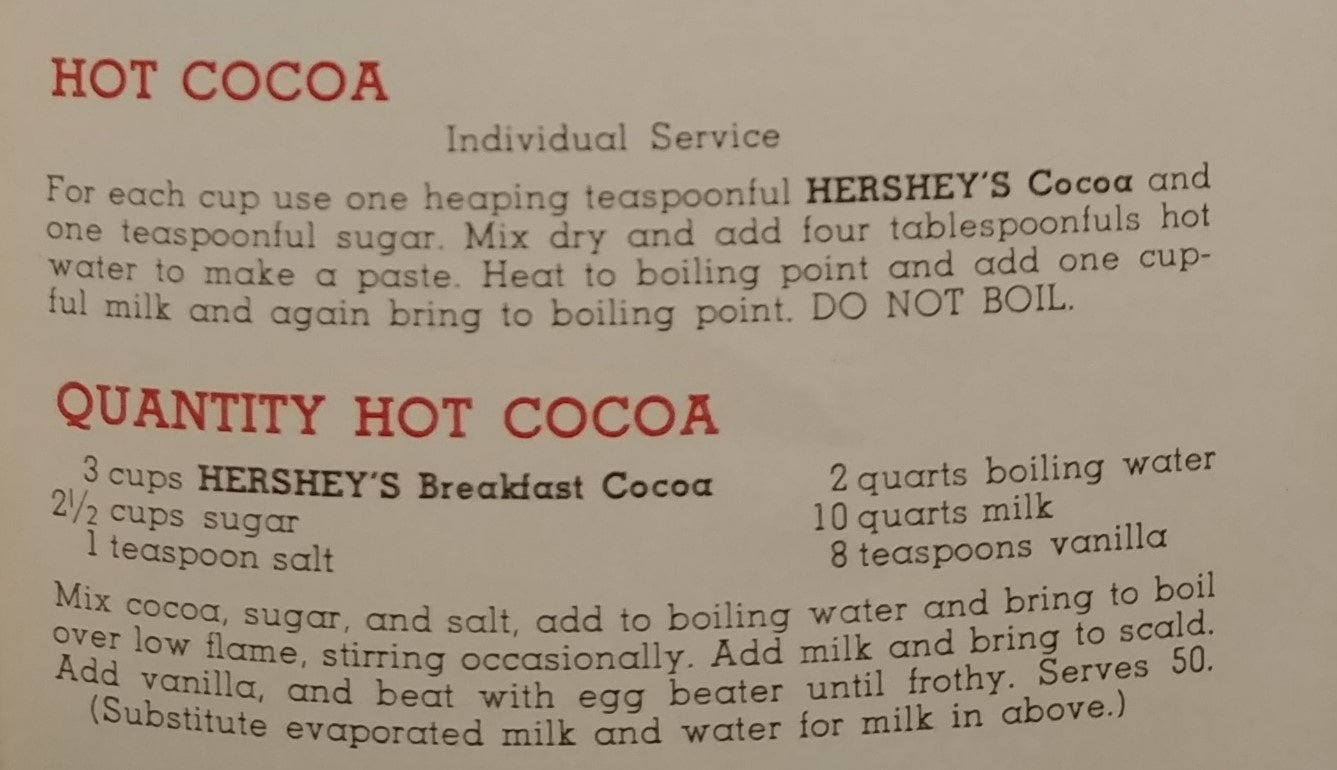

In the United States, the terms "hot chocolate" and "hot cocoa" are used pretty interchangeably, but they aren't quite the same thing! Hot ChocolateHot chocolate is a truly ancient drink, dating back as many as 3000 years. Developed by ancient Indigenous people in Mesoamerica, the cacao bean was used by the Olmecs and drinking chocolate perfected by the Maya and Aztecs. A mixture of ground roasted cacao beans, spices, including chili peppers and vanilla, sometimes sweetened with honey, and often containing other ingredients, including ground maize and cochineal to color it red, early drinking chocolate was frothed into a foam and consumed as part of religious ceremonies. In the late 16th century, Spanish invaders had brought cocoa beans - and drinking chocolate - back to Spain, where it quickly spread throughout aristocratic Europe. It came to colonial America via Europe in the late 17th century, where cocoa processors started importing direct from Central America and the Caribbean. Hot chocolate became a fashionable breakfast beverage. But how was it made? Processed cocoa beans were fermented in the pulp, then dried, then roasted. Chopped into nibs, they were then stone ground to create a chocolate paste. Mixed with sugar, hot water, and spices, the bitter drink was served with cream and sugar, much like coffee or tea. By the 18th century, cakes of processed chocolate were being produced for transformation into drinking chocolate. In the mid-19th century, cocoa butter and sugar were added to the cacao and through conching and tempering, eating chocolate developed. By the Victorian period, hot chocolate had transformed from a popular adult beverage on par with coffee and tea, to the purview of children. Hot CocoaPart of the shift from breakfast beverage of aristocrats to children's treat had to do with the fact that both cacao and sugar were increasing in production and therefore dropping in price throughout the 19th century. Cocoa production expanded to other equatorial areas besides Mesoamerica and sugar, fueled by slavery and technological advances, also increased in production. The development of cocoa powder in the 1820s helped expand access to chocolate. Cocoa powder is created by melting or pressing the cocoa butter out of the nibs, then drying and grinding the defatted cocoa beans. Lighter weight, more shelf stable, and easier to blend into beverages than drinking chocolate, cocoa powder became the main ingredient in hot cocoa recipes. Most cocoa powder was natural process, like Hershey's, meaning that it was dried and ground after the Broma process of defatting. But some cocoa powders (like Fry's) were Dutched, or created using the Dutch process, which meant that the defatted cocoa nibs were immersed in an alkaline solution to help neutralize some of their natural acidity before being dried and ground. Natural cocoa is reddish brown in color - Dutch process color is a dark grayish brown. So there you have it! The difference between hot chocolate and hot cocoa is that one is made from melted cocoa, usually 100% cacao unsweetened chocolate, and hot cocoa is made from a mixture of cocoa powder and sugar, often cooked into a syrup. But how do you know which one you prefer? Hot chocolate or hot cocoa? Try these historic recipes and find out! Baker's Hot Chocolate Recipe (1936)I made this recipe as part of a talk on hot chocolate history, and while not very sweet, it is very rich and chocolatey. If you are a chocoholic, this is the recipe for you. Please note that you'll need Baker's Unsweetened 100% Cacao Chocolate, and that these days 2 squares is really 2 ounces, or 8 quarter ounce rectangles. 2 squares Baker's Unsweetened Chocolate 1 cup water 3 tablespoons sugar dash of salt 3 cups milk Add chocolate to water in top of double boiler and place over low flame, stirring until chocolate is melted and blended. Add sugar and salt and boil [over direct heat] 4 minutes, stirring constantly [this will boil off most of the water and make a thick syrupy chocolate]. Place over boiling water, add milk gradually, stirring constantly; then heat. Just before serving, beat with rotary egg beater until light and frothy. Serves 6. Hershey's Single Serve Hot Cocoa Recipe (1937)For each cup, use one heaping teaspoonful HERSHEY'S COCOA and one teaspoonful sugar [I used a heaping spoonful, which it needed]. Mix dry and add four tablespoons hot water to make a paste. Heat to boiling point and add one cupful milk and again bring to boiling point. DO NOT BOIL. You can use either natural process or Dutch process cocoa for this one. It is not as thick and rich as the Baker's hot chocolate, but it does have that familiar cocoa taste from childhood and is still quite good. You can always change these recipes to suit your tastes with more sugar or with half and half or part cream, instead of all milk. Top with whipped cream, marshmallows, or try your hand at Indigenous-inspired spices like chili powder, cinnamon, vanilla, etc. You can also substitute almond milk (the most historical substitution, since almond milk was known in 16th century Europe), or any other non-dairy milk. Which do you prefer, hot chocolate or hot cocoa? And how do you like yours prepared? I like mine extra-creamy with whipped cream. Maybe a little peppermint or salted caramel syrup if I'm feeling extra-indulgent. Share your perfect cup in the comments! These recipes are part of a talk with cooking demonstration on the history of hot chocolate I do for public events. For upcoming programs, visit my Event page. The Food Historian blog is supported by patrons on Patreon! Join us for awesome members-only content like free digitized cookbooks from my personal collection, e-newsletter, and even snail mail from time to time! For those of you who have been following along, this is part of my "Dinner and a Movie: White Christmas" series! A "malted" makes an appearance in my favorite club car scene as Bob, Phil, Betty, and Judy make their way from Florida to Vermont. As they order some late-night snacks, Judy orders a "malted" from the bartender (who, coincidentally, I believe is the only Black person in the entire movie). What she means of course, is a malted milkshake - vanilla, not chocolate. And while I love malted everything, from chocolate-covered malted milk balls to malted milkshakes, this special ingredient has its roots in the brewing industry. Malt is made from barley and was originally a primary ingredient in beer (malt-based beers are some of the only ones I'll drink - I prefer them to hops-fermented ones), and later whiskey. Barley is partially sprouted and then dried and ground to create malt. In the 19th century it also became an industrial baking product, helping to give sweetness and a nice crust to breads. But in the 1870s, British pharmacist James Horlicks was trying to come up with an alternative food to raw milk for infants and a nutritional supplement for invalids. Milk at the time was rarely pasteurized and could often infect children with diseases. Lacking funds, he emigrated to Racine, Wisconsin, where his younger brother already lived. By the 1880s the brothers had patented a fortified gruel that they dried and ground, containing malted barley, ground grains, and dried milk. Developed as a water-soluble food for infants, it was quickly adopted in both tropical climates and polar expeditions for its shelf stability, palatability, and nutritional content. Horlick's brand malted milk became the industry standard and was adopted by the Temperance movement as well, showing up in soda fountains and in ice creams. In 1927, Carnation launched its own brand of malted milk and soon chocolate options were available on the market as well. Ovaltine, a malted milk powder that originally also contained eggs, was developed in Switzerland in the 1900s (originally with the name "Ovomaltine"). By the time we get to White Christmas in 1954, malted milkshakes, including chocolate malts, were a fixture of diners and soda fountains (and, apparently, trains) everywhere. Today, Carnation is one of the few malted milk powders widely available, and that's what I used. They also had a recipe for malted milkshakes right on the back of the container. Vanilla Malted MilkshakesThis recipe is per serving. 2 scoops vanilla ice cream 3/4 cup whole milk teaspoon vanilla extract 3 tablespoons malted milk powder Place all ingredients in a blender and blend until smooth. This did make a very good milkshake - the ratio of ice cream to milk was just about perfect. Although it was maybe a little more liquidy than I like, it didn't get ice crystals, as you sometimes do with homemade milkshakes. That being said, three tablespoons of malted milk powder is a LOT, and resulted in a very strong malted milk flavor. If you're unsure of how fond you are of malted milk, I would cut it down to two tablespoons. This makes about 12-16 ounces, so make sure to pour it into a tall glass and top it with whipped cream. Be sure to follow the White Christmas tag or visit the original menu post for the rest of the White Christmas Dinner and a Movie menu. Are you going to make this, or another beverage from the list? Want to see more Dinner and a Movie posts? Make a request or drop your suggestions in the comments! The Food Historian blog is supported by patrons on Patreon! Join us for awesome members-only content like free digitized cookbooks from my personal collection, e-newsletter, and even snail mail from time to time!

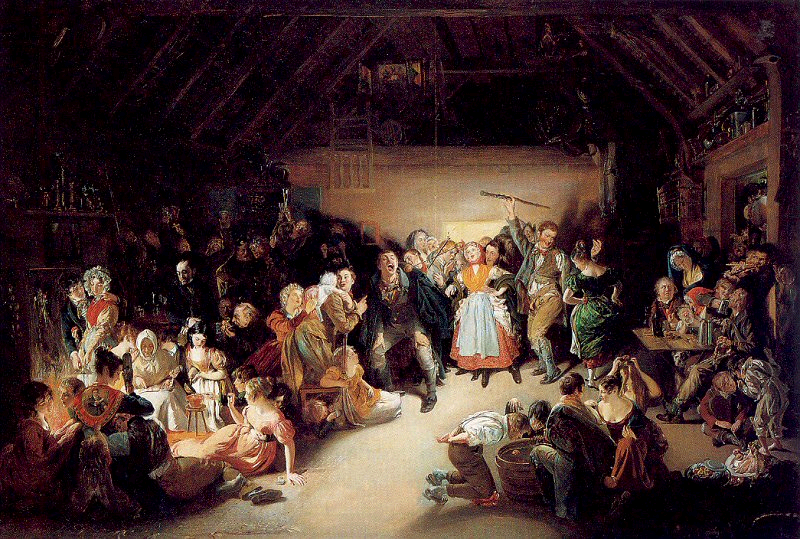

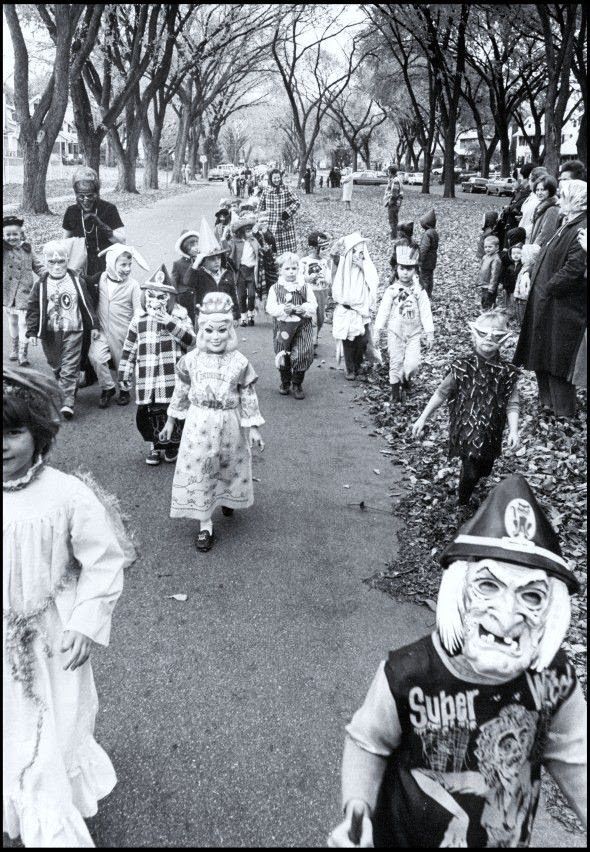

Thanks to everyone who joined us for Episode 22 of the Food History Happy Hour! This was a very special Halloween themed episode! We made the early 19th century Stone Fence cocktail, and talked about all sorts of historic Halloween traditions and foods, including the Celtic and Catholic origins of Halloween, Halloween games and divination, including Snap Apple (as illustrated above), donuts, party foods including gingerbread, grapes and grape juice, apples, pumpkins, color themed parties, decorations, including Dennison's Bogie Books, the history of trick-or-treating, and more!

Stone Fence Cocktail (19th Century - 1946)

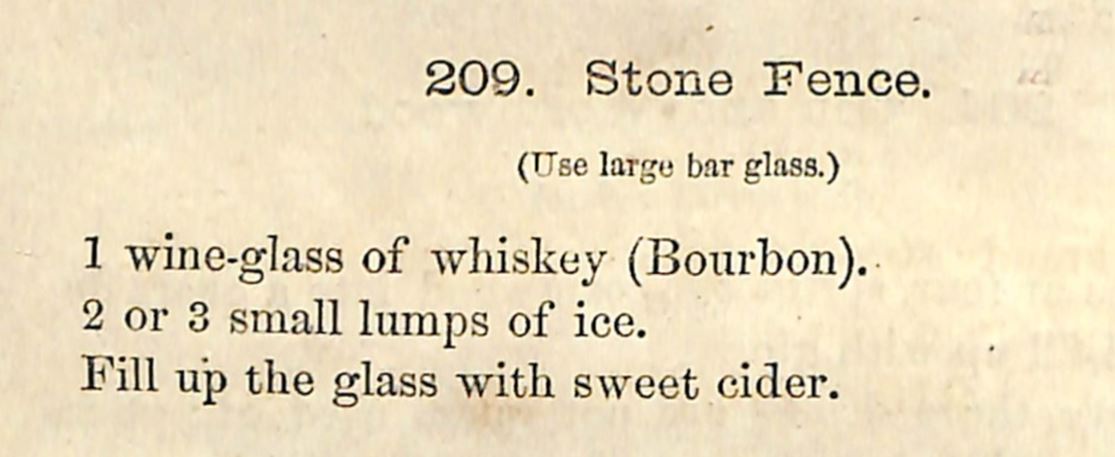

There's all kinds of versions of this - I was first introduced to the Stone Fence in the Roving Bartender (1946), and of course it's in Jerry Thomas' "How to Make Mixed Drinks" (1862) also has a version, which is largely how it gets popularized in bars across the country. But mixing hard cider with brown liquor dates to much earlier, and the type of brown liquor depends on the region. Both of these recipes call for Whiskey/Bourbon, but I decided to go with spiced rum. Other versions also call for Angostura bitters or cinnamon, which is unnecessary if you use spiced rum, like I did.

You'll note that the Jerry Thomas recipe actually calls for the use of sweet cider, which is unusual. Here's the original recipe:

(209) Stone Fence. (use a large bar glass) 1 wine glass of whickey (bourbon). 2 or 3 small lumps of ice. Fill up the glass with sweet cider.

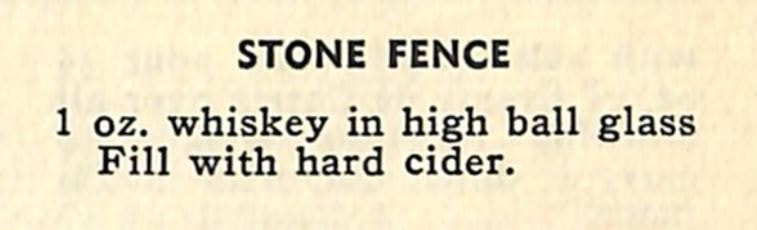

I like the Bill Kelly recipe from the Roving Bartender a bit better. Here's the original:

Stone Fence. 1 oz. whiskey in a high ball glass Fill with hard cider. And of course, there's my own version! 1 oz. spiced rum Fill with hard cider (I used Strongbow Artisanal Blend) I did not use ice, because I was lazy, but if you don't make sure your hard cider is chilled for the best version. You could also turn this into a sort of flip by heating the hard cider (don't boil unless you want to lose the fizz and the alcohol content) and adding the spiced rum at the last minute. Episode Links

I love Halloween and had a bunch of fun putting this together.

That's all for tonight! I hope everyone has a very Happy Halloween tomorrow and we'll see you in November for the next episode of Food History Happy Hour!

Food History Happy Hour is supported by patrons on Patreon! Join us for awesome members-only content like free digitized cookbooks from my personal collection, e-newsletter, and even snail mail (like the Halloween packet) from time to time!

Thanks to everyone who joined us for Episode 21 of the Food History Happy Hour! We discussed pumpkins and their indigenous origins, as well as the history of pumpkin pie spice, including a discussion of the European spice trade, where various spices come from, and how they went from the purview of the fabulously wealthy to hopelessly old-fashioned, to ragingly popular again. Plus we talk about how pumpkin spice got its name and what's REALLY in those cans of pumpkin puree.

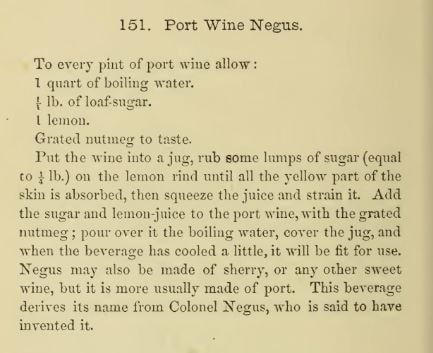

Port Wine Negus (1862)

This particular recipe comes from the famous Jerry Thomas, in his 1862 book, The Bar-Tender's Guide but the drink is actually much older, dating back to the 18th century, and features in the novels of Jane Austen and Charles Dickens. By the Victorian period, it was commonly used for children's parties (shocking I know), and it seems that Jerry Thomas may have lifted his recipe directly from Isabella Beeton.

I followed this recipe pretty closely, and it makes a LOT - I filled my teapot full - so be aware that either you need to save any leftovers for a soda negus (also in Jerry Thomas), share with friends, or cut the recipe down. Here's the original: 151. Port Wine Negus

Here's the version I made:

4 cups water, brought to a boil 2 cups Ruby port 1/2 cup sugar 4 tablespoons bottled lemon juice 4 cloves about 1/4 teaspoon fresh grated nutmeg This makes one and a half quarts of hot Negus, which is delicious but was too sweet for my taste. I'm guessing the original recipe called for Tawny port, which is not as sweet as Ruby port. I also cheated and used bottled lemon juice instead and added cloves because another recipe for soda negus I saw called for them. It really is imperative to use fresh nutmeg for this recipe, as the ground kind doesn't hold a candle in flavor. One or two nutmegs will last you a long time, so you don't have to buy a ton. It is fairly addictive, so just be forewarned. I may or may not have had four cups in the course of Food History Happy Hour and writing this blog... Episode Links:

I had fun researching this topic and even learned a few things! One of my primary sources for the European spice trade as the book Nathaniel's Nutmeg, by Giles Milton. It's a highly engaging read and designed for a more popular audience, so if anyone wants to read about bloodthirsty Europeans obsessed with spice and their various maritime misfortunes, check it out.

other fun links include:

The next Food History Happy Hour won't be until Friday, October 30, 2020, but we'll be discussing Halloween! And making the Stone Fence cocktail. I hope you'll join us then. AND! I have a special treat for Patreon members old and new - join or renew at the $5 level and above, and you'll get a special Halloween packet mailed to you! Chock full of all kinds of fun history, images, party ideas, recipes, and more.

If you enjoyed this episode of Food History Happy Hour and would like to support more livestreams, please consider joining us on Patreon. Patrons get special perks like access to members-only content.

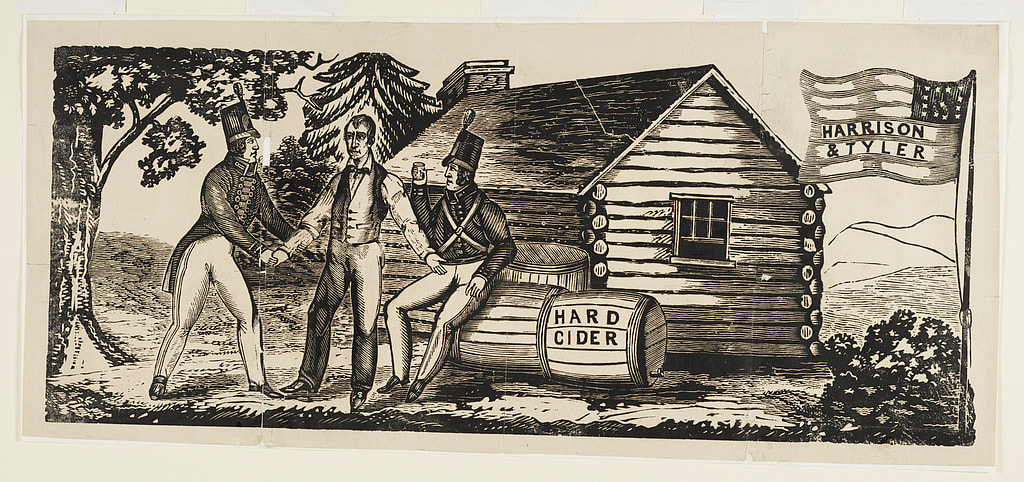

An untitled woodcut, bold in design, apparently created for use on broadsides or banners during the Whigs' "log cabin" campaign of 1840. In front of a log cabin, a shirtsleeved William Henry Harrison welcomes a soldier, inviting him to rest and partake of a barrel of "Hard Cider." Nearby another soldier, already seated, drinks a glass of cider. On a staff at right is an American flag emblazoned with "Harrison & Tyler." Library of Congress.

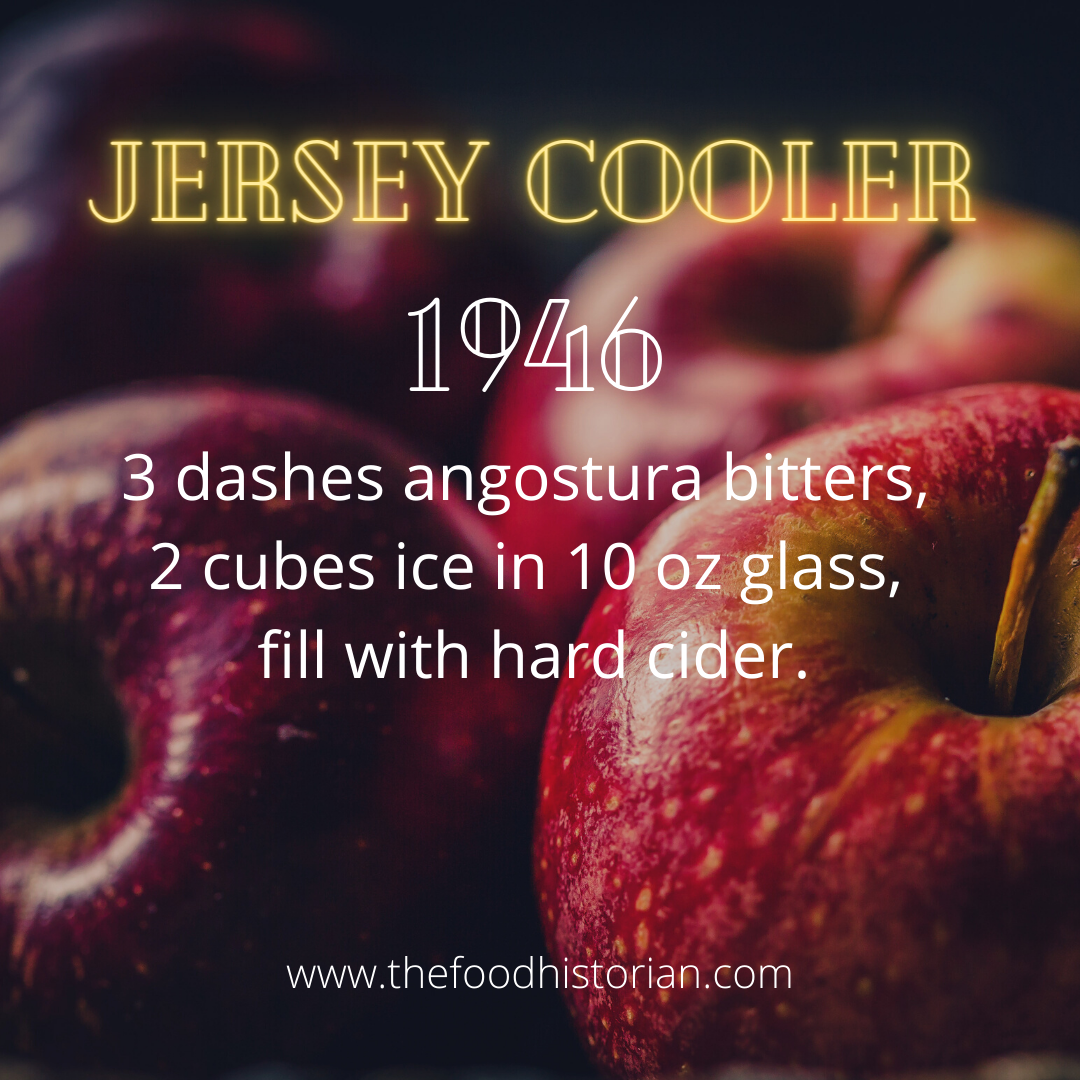

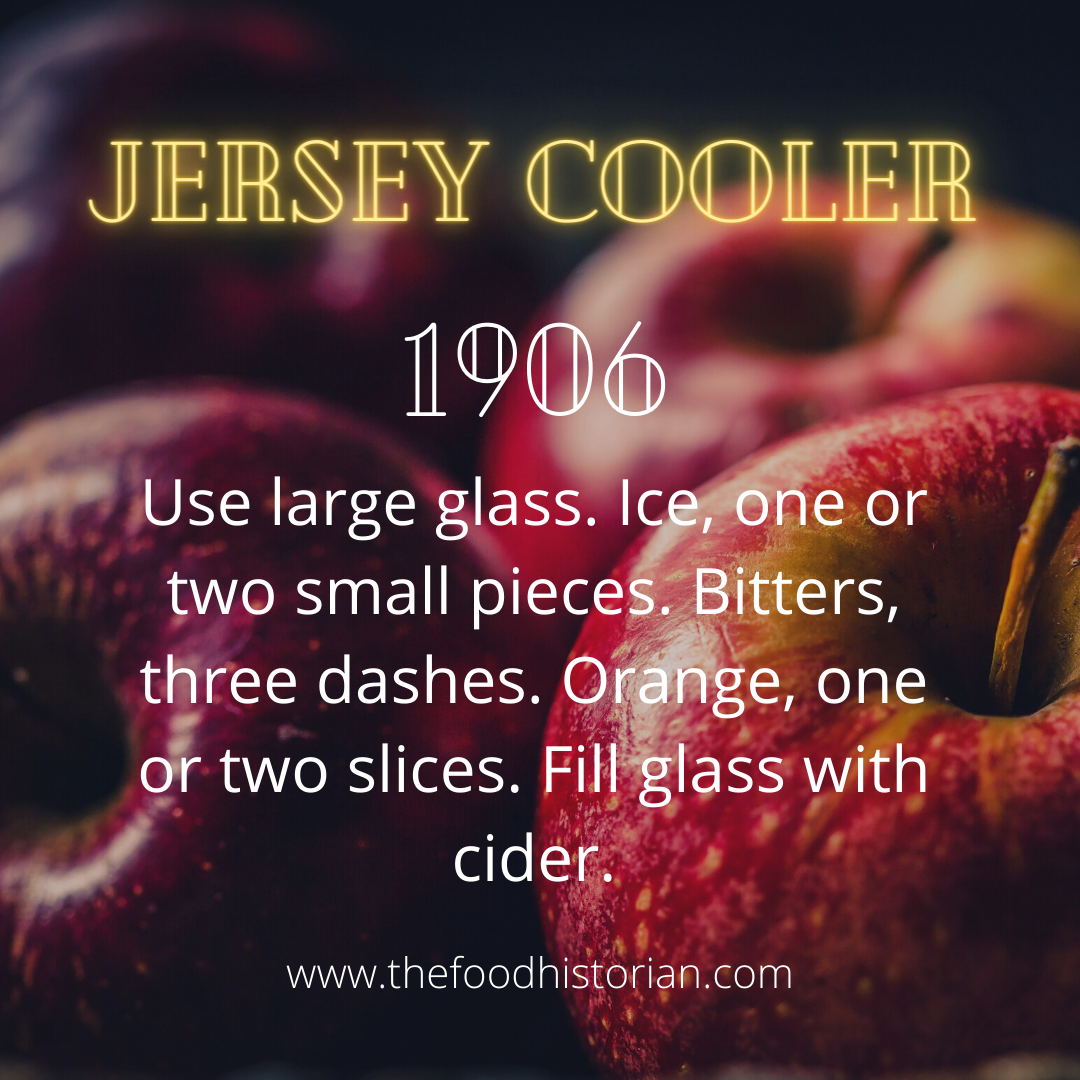

Thanks to everyone who participated in this week's Food History Happy Hour! In this episode we made the Jersey Cooler from the Roving Bartenter (1946), but the cocktail itself appears to have been invented by the famous Jerry Thomas as it appears in his 1862 How to Mix Drinks.

With the primary ingredient hard cider, I thought it a particularly apt cocktail for our discussion of apples in America! I chose apples as the topic for tonight's Food History Happy Hour because mid-September is when apple harvest in the Northeast usually really starts to get underway. Coincidentally (on my part, anyway), tonight is also the start Rosh Hashanah, or the Jewish New Year, which runs until Sunday. One of the components of Rosh Hashanah is the use of apples and honey, particularly in Ashkenazi Jewish households, who originate in Eastern Europe. Apples and honey are eaten to symbolize sweetness and prosperity for the coming year. On a more somber note, I learned that Supreme Court Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg passed away just minutes before the start of the show. In fact, I almost didn't do tonight's episode because I was so upset. But I figured that the notorious RBG would power through if it was her, and it was fitting to be talking about apples and hoping for peace and prosperity in the coming New Year. So we poured one out for Ruth and gave her a toast. We talked about the origins of hard cider, with an aside about the 1840 presidential campaign of William Henry Harrison, why hard cider fell out of favor, the origins of apples in the mountains of Kazakhstan, Johnny Appleseed, the story of Red Delicious, heirloom apple varieties, and the not-so-American origins of apple pie. Jersey Cooler (1946)

From the 1946 Roving Bartender by Bill Kelly:

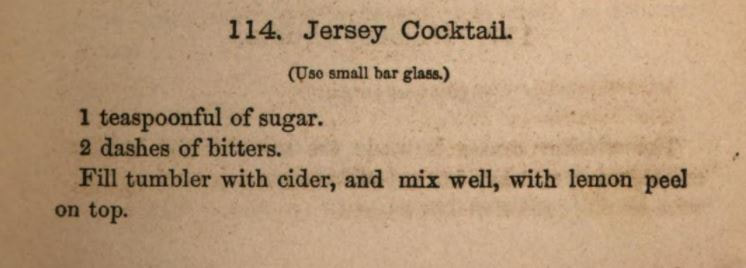

You can see other, slightly more complicated versions below: Jersey Cocktail (1862)

As far as I can tell, this is the oldest version of the Jersey Cooler (called cocktail here), invented by the famous Jerry Thomas from his How to Mix Drinks from 1862. Because the earliest reference is from Mr. Thomas, who was a born and raised New Yorker, I think that the "Jersey" in this instance refers to New Jersey, not Jersey, England.

Here's his recipe: (Use small bar glass.) 1 teaspoonful of sugar. 2 dashes of bitters. Fill tumbler with cider, and mix well, with lemon peel on top. Episode Links

Our next episode will be on Friday, October 2, 2020 and since it will officially be October, we'll be talking about pumpkins and the origins of the much-maligned pumpkin spice!

If you enjoyed this episode of Food History Happy Hour and would like to support more livestreams, please consider joining us on Patreon. Patrons get special perks like access to members-only content.

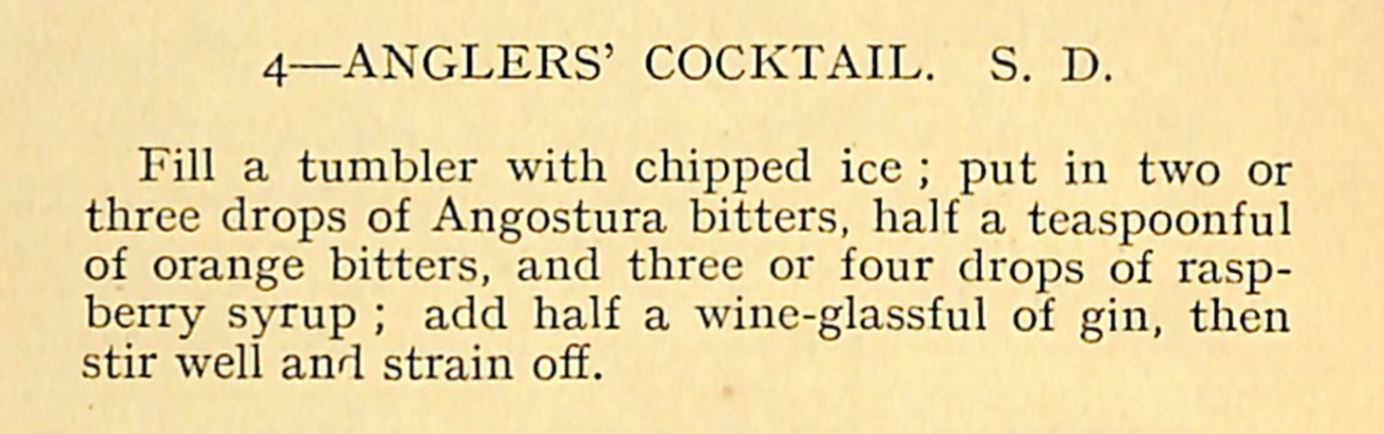

Thanks to everyone who participated in this week's Food History Happy Hour! In this episode we made the Angler's Cocktail from Recipes of American and Other Iced Drinks, London (1909).

Because it's Labor Day Weekend and traditionally one of the biggest travel dates of the year, I thought we could talk about road food! We discussed the development of early federal highways, including Route 66, the Eisenhower Interstate Highway System, the Green Book and Driving While Black, rest areas versus service areas, Howard Johnson's and the development of other fast food chains, Gourmet and Ford Motor Company travel books on regional restaurants, the work of Jane and Michael Stern to catalog regional foodways, and the foods people took with them while traveling, roadside stands, and more. Angler Cocktail (1909)

Here's the original recipe, from Recipes for American and Other Iced Drinks by Charlie Paul (1909):

Fill a tumbler with chipped ice; put in two or three drops of Angostura bitters, half a teaspoon of orange bitters, and three or four drops of raspberry syrup; add half a wine-glassful of gin, then stir well and strain off. Here's my version: 3 drops Angostura bitters 6 drops orange bitters a dash of raspberry syrup 2 ounces American gin Add to a cocktail shaker of crushed ice - swirl until cold, then strain into a cocktail glass. It's quite lovely - very floral and a pretty shade of peachy gold. I would add more raspberry syrup next time as I couldn't taste it at all and the drink was not sweet at all. Episode Links:

We're switching to a twice-a-month schedule, so join us on Friday, September 18, 2020 at 8:00 PM EST for the next episode of Food History Happy Hour!

If you enjoyed this episode of Food History Happy Hour and would like to support more livestreams, please consider joining us on Patreon. Patrons get special perks like access to members-only content.

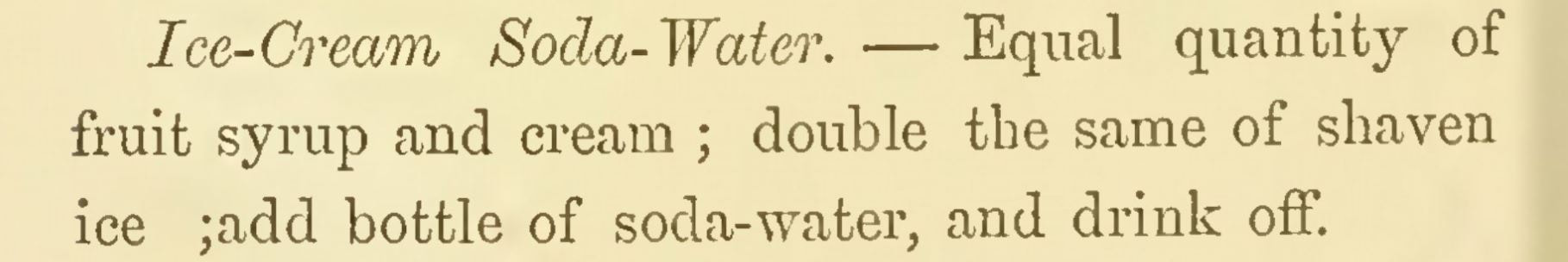

Thanks to everyone who participated in this week's Food History Happy Hour! In this episode we made the Ice-Cream Soda-Water from Cooling Cups and Dainty Drinks (1869). As I went through the laborious process of hand-shaving ice from a block, we briefly discussed the history of ice harvesting and the first uses of soda fountains.

We also discussed all things hot dog! Including the history of hot dogs, how they are made, their prevalence at beaches, ball parks, and fairs, regional variations in hot dog toppings, the origin of the corn dog, and the use of hot dogs in American diplomacy, including famously by Franklin D. and Eleanor Roosevelt in Hyde Park when they entertained King George VI and Queen Elizabeth of Great Britain in 1939. We also discussed sweet v. savory cocktails in history, uses for leftover hot dog buns, and more. Check it out! Ice-Cream Soda-Water (1869)

In my research for last week's episode into the origins of the root beer float, I found reference in the 1860s to soda fountains and the invention of the ice cream soda that was simply ice and cream and soda water. So it was fun to discover this recipe in the cocktail guide Cooling Cups and Dainty Drinks (1869).

The original recipe doesn't have much direction, but here it is:

Ice-Cream Soda-Water - Equal quantity of fruit syrup and cream; double the same of shaven ice; add bottle of soda water and drink off. Here's my recipe: 1 cup hand-shaven ice (the more the better) 1 ounce raspberry syrup (a 19th century favorite!) 1 ounce heavy cream 6-8 ounces seltzer or club soda Place the ice in a large tumbler and pour syrup and cream over, top with seltzer, stir gently, and drink quickly. "Dog Factory" by Thomas Edison (1904)

A Food Historian friend asked if I was going to "ruin" hot dogs for Food History Happy Hour by discussing how they are made. I didn't make any promises, but thought this Thomas Edison film was fun to watch. In it, dogs are turned into hot dogs, and hot dogs are turned back into dogs. In the background of the "factory" - which closely resembles a hot dog push cart - ropes of sausages hang on the wall labeled by type of dog.

It's a bit gross, but meant to be all in good fun - making a joke (as always) about the origins of the meat used to make hot dogs, something that still occurs today. In the end, more sausages get magically turned into dogs than vice versa. Episode Links

This was a fun episode to research, and here are a few of the articles I referenced:

Thanks for watching!

If you liked this post and would like to support more Food History Happy Hour livestreams, please consider joining us on Patreon. Patrons get special perks like access to members-only content.

|

AuthorSarah Wassberg Johnson has an MA in Public History from the University at Albany and studies early 20th century food history. Archives

July 2024

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed