|

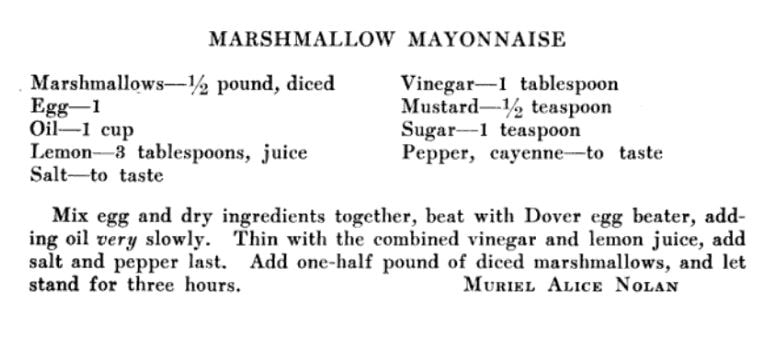

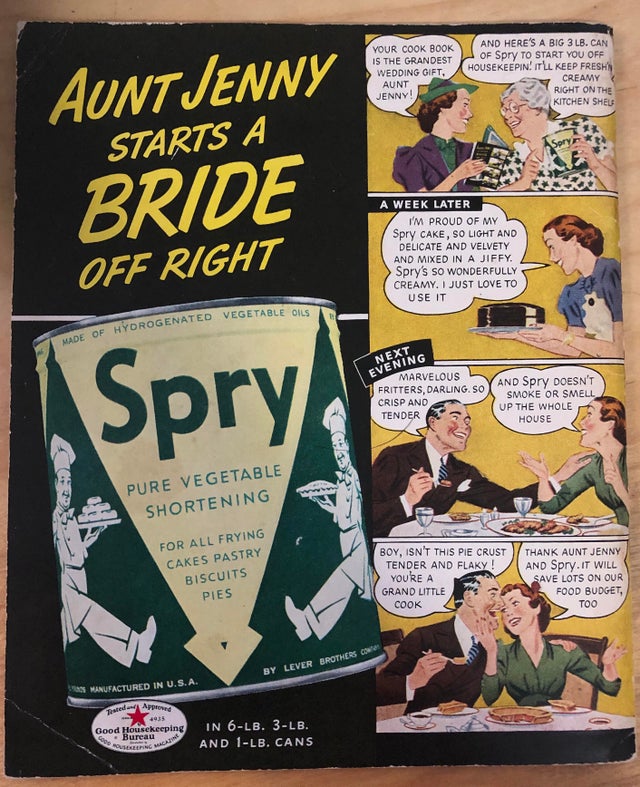

Well friends, I said I was contemplating a part two to last week's examination of 1950s food, and this meme kept popping up on my socials, so here we are again! This one isn't quite as inflammatory, and no fun illustration to catch your eye, but it makes a similar claim nonetheless. Here's the original text: The main thing I get from Dylan Hollis cooking old recipes is this: If you haven't seen any of Dylan Hollis' TikTok videos, I recommend them! He's hilarious. Not a food historian, but he cooks historic recipes and taste tests them. Some are horrific, but most are delicious - and while Dylan's reactions are 99% of the fun, his shock when things are actually tasty, while hilarious, does grate a little sometimes. Yes, people in the past really did know what they were doing! The meme claims that the food of the 1910s and the Great Depression were better than the 1950s, and were made with love, working with limited ingredients, whereas 1950s recipes were made to sell products during the McCarthy era. And while those ideas aren't necessarily wrong, they're definitely not the whole story. The time period of 1900 to 1950 is my favorite time period for cookbooks. They usually have decent instructions with things like measurements and oven temperatures, but are still from scratch. USUALLY being the key word there. Because starting in the 1870s, corporate food brands started publishing cookbooklets to sell their products. One of the earliest adopters of this sales tactic? Cottolene brand shortening. Not exactly lard, but pretty darn close! A lot of the corporate cookbooks and cookbooklets of the late 19th and early 20th century were primarily for ingredients. Different brands of flavorings and spices, baking powder, flour, shortening or lard, etc. were the main branded food products at the time. A lot of major food companies today started out as flour companies, including General Mills. So the cookbooks were largely normal scratch recipes that just recommended the cook or baker use the branded ingredients, but it was easy to substitute whatever you had on hand. And then, we started to get corporate food products like Campbell's canned soups, and Libby's canned corned beef, and powdered Knox gelatine and Jell-O, and other foods that were closer to finished foods already. You can only eat so much soup in a week. So how was Campbell's to get people to eat more of it? In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, we had more and more women graduating from food and nutrition schools and college programs. Domestic scientists and expert cooks and home economists happily filled the role of cookbook authors and test kitchen managers for food corporations. Which is how we got things like tomato soup spice cake (Dylan Hollis does a recipe from the 1950s, but it was actually invented in the 1920s!), cream of whatever soup casseroles, and marshmallow mayonnaise. While tomato soup spice cake is probably delicious (at least, Dylan Hollis thinks it is!), and cream of whatever soup is a lot easier than white sauce, I'm not sure about the marshmallow mayonnaise, but the cookbook says to serve it with fruit salad, so maybe it is? Who am I to judge? The point being, by the 1910s, there were plenty of marketing cookbooks and advertisements with recipes for processed foods for housewives to choose from. And while home economists were cranking out recipes that were sometimes smash hits and sometimes abject failures, there was a bit of a storm brewing in households around the country. Mainly, the "servant problem." For most of the 19th century, middle and upper-middle class families had at least one household servant (or enslaved person, prior to the Civil War) who did the bulk of the heaviest household labor. Middle class women and their daughters did household work too, but were generally spared things like scouring pots and scrubbing floors and hauling water and coal. But at the turn of the 20th century, we started to get pink collar jobs - being a shop girl or secretary or teacher or nurse was preferable for many women to the 24/6.5 schedules of being in service. Rural families usually had lots of children to help with agricultural labor, but in a family of 6 or 10, the older girls always helped care for the younger children and everyone did household chores. As families shrunk and household servants became harder to find and more expensive, more and more women had to do with less and less help at home. At the same time, education levels for women were rising. Girls stayed in school beyond the elementary level and attended high school and college in larger and larger numbers. Many parents also wanted better lives for their children than they had, and wanted to spare girls the drudgery of household labor. Upper and upper-middle class girls, in particular, had been raised in households with servants and mothers who spared them all but the basics of running a household. So when they married, all of a sudden girls with college educations had to figure out household budgets and weekly grocery shopping and cooking on their own, without many skills or resources to help them. Enter the ad man and the home economist. Swearing to save the clueless young bride from a lifetime of drudgery, while still pleasing her husband, all sorts of companies targeted young, inexperienced women just starting their households, but none perhaps as diligently as Spry, which manufactured first lard and later shortening (there's that lard reference again!). Aunt Jenny was the fictional grandmotherly character who knew just everything and would teach it all to her clueless niece. And of course, the secret was always a giant can of Spry. While Spry cookbooklets joined the legion of competitors, it was their cartoon-style print ads and extensive radio shows and advertisements that helped sway millions of American women to the Spry way of life. Is it any wonder that women who married in the 1930s and '40s raised children in the 1950s on corporate foods? Untrained, without the household help of their mothers and grandmothers, and with high expectations for home cleanliness and cooking three meals a day, 364 days a year would be enough to drive anyone into the arms of kindly home economists and fictional characters like Aunt Jenny, Mary Lee Taylor, Betty Crocker, and others. Recipes as advertisements for corporate foods did NOT start in the 1950s by any means. But the meme is somewhat correct in that scratch cooking was more prevalent in the Great Depression in particular, largely because at the time industrial foods were still more expensive than cooking from scratch, and because women who were adults in the 1930s were more likely to have been born into households that still taught them something about cooking and household management. And although the balance of population in the United States tipped from rural to urban in the 1920s, we still had a huge population of people primarily involved in agriculture, meaning families were larger (my mom's parents, born to farmers in the 1930s, came from families of 9 and 10 children, respectively), so women had more household help. Rural areas were also slower to adopt new fashions, including fashionable food, and often had less access to industrial goods of all sorts, including processed foods. Rural families were also much more likely to grow and preserve the bulk of their own food, well into the 1970s, than the rest of America. If you had land and free labor, it was certainly cheaper than buying commercially canned goods. If your grandmother grew up in a rural area during the Great Depression, like mine did, she probably learned how to cook from scratch. But by the 1950s, she was raising kids on her own, and maybe had a career of her own, or was supporting her husband's career, which meant less time to cook from scratch as she cared for her own children and a house with higher standards of cleanliness and fashion than her mother's with a lot less help. At the same time, in the 1950s, the general consensus was that industrial foods were the wave of the future - they were boons to help a busy housewife, not things to be scorned and rejected. And as incomes rose, it was much easier to purchase foods than doing your own home preserving. And while the Great Depression did result in a lot of creative cooks (banana bread, for instance), I find the mention in the original meme of Saltines ironic. Although Saltines and cracker companies like Ritz didn't invent cracker-based mock apple pie (that dates back to the 1850s, believe it or not), they sure hopped right on that bandwagon and used it as a selling point. Necessity is the mother of invention. But rising incomes are the mother of convenience. And while McCarthyism probably did prevent the spread of some delicious and interesting foodways through its xenophobia and rigid conformity, the road to corporate convenience foods was a long one. They didn't appear overnight once the calendar ticked over from 1949 to 1950. Indeed, scratch cooking and baking continued well into the 1950s, and many of the foods we associate with the 1950s (Cool Whip, anyone?) weren't actually invented until the 1960s. For instance, the Pillsbury Bake-Off baking contest didn't start until 1949, and while modern incarnations of the contest are usually dominated by mutated versions of whatever convenience food Pillsbury has cooked up (usually crescent rolls or cinnamon rolls or canned biscuits), the original contest was meant to promote Pillsbury flour, so the recipes are all from scratch. And looking at my food historian library shelves, the 1950s section has plenty of community cookbooks filled with can-of-this, box-of-that recipes, and advertising cookbooklets galore, but there are also cookbooks like The Magic in Herbs (first printed in 1941 but on its seventh printing by my 1950 copy) and The Peasant Cookbook (1955, and my copy was from the library of the Ladies' Home Journal!), and Whole Grain Cookery (1951) and those community cookbooks always had scratch recipes in them, too. And my 1930s section? I have more corporate cookbooklets from the 1930s than any other era! Like most of history, individual decades might be changed and marked by big events, but history is complicated. In the Progressive Era we had brutal strikes and food riots, but we also had Gibson Girls and Vanderbilts and Rockefellers. During the Great Depression we had the Dust Bowl and migrant workers, but we also had the glamour of Hollywood. And yes, in the 1950s we had McCarthyism (and sexism and racism) and processed food, but we also had folks like James Beard and Julia Child and plenty of scratch cooking. So let's stop stereotyping decades and accept them for what they are - complicated, messy, and fascinating time periods with both good food and bad. And the next time you see a corporate food cookbook from the 1950s - give it a gander. You might be surprised by what you find inside. There are good recipes in just about every cookbook, if you take the time to look. The Food Historian blog is supported by patrons on Patreon! Patrons help keep blog posts like this one free and available to the public. Join us for awesome members-only content like free digitized cookbooks from my personal collection, e-newsletter, and even snail mail from time to time! Don't like Patreon? Leave a tip!

0 Comments

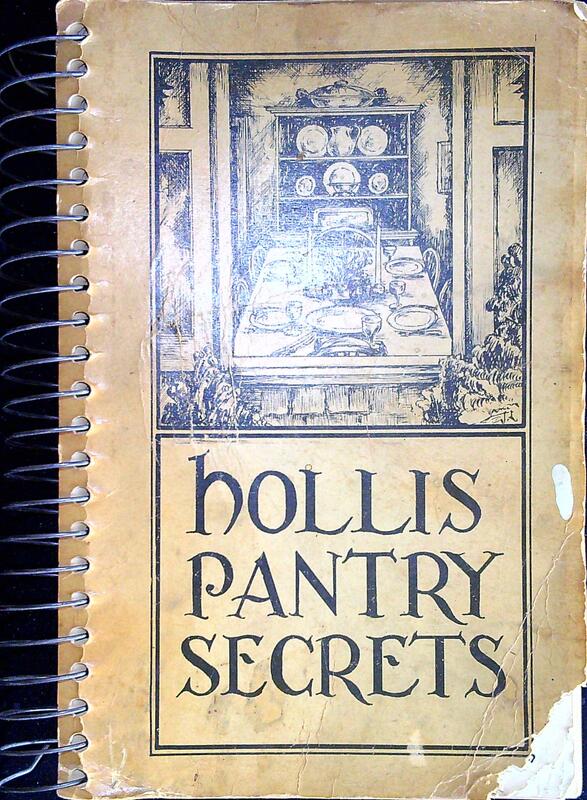

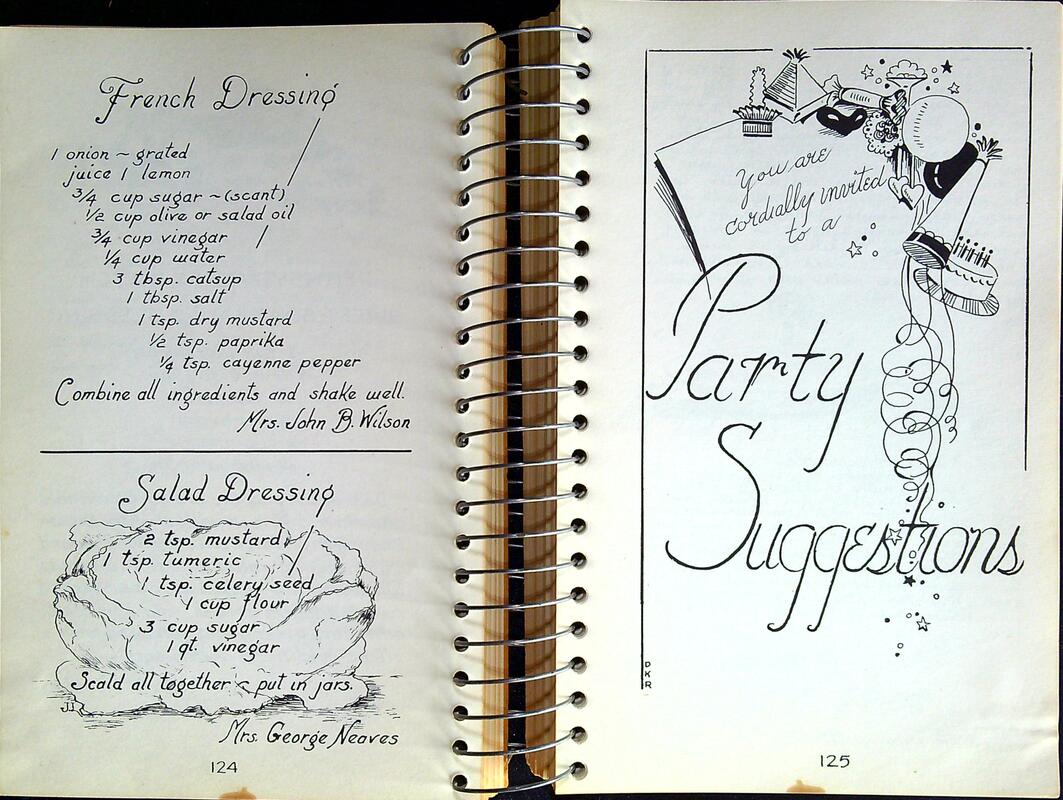

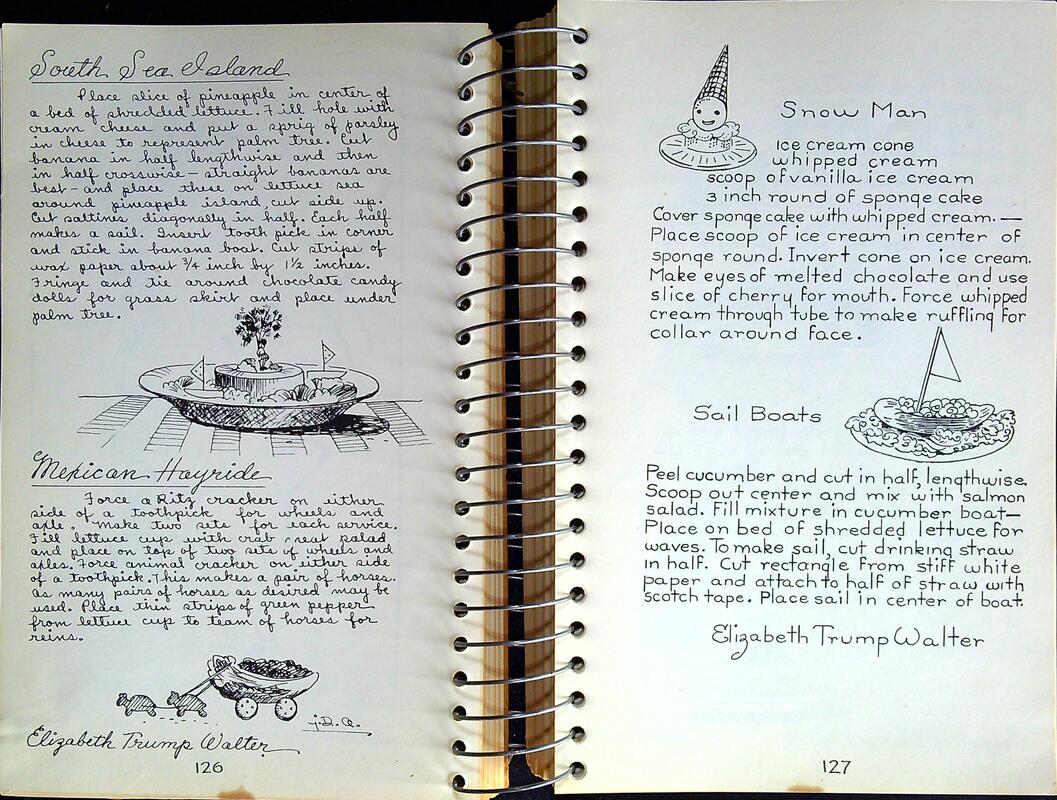

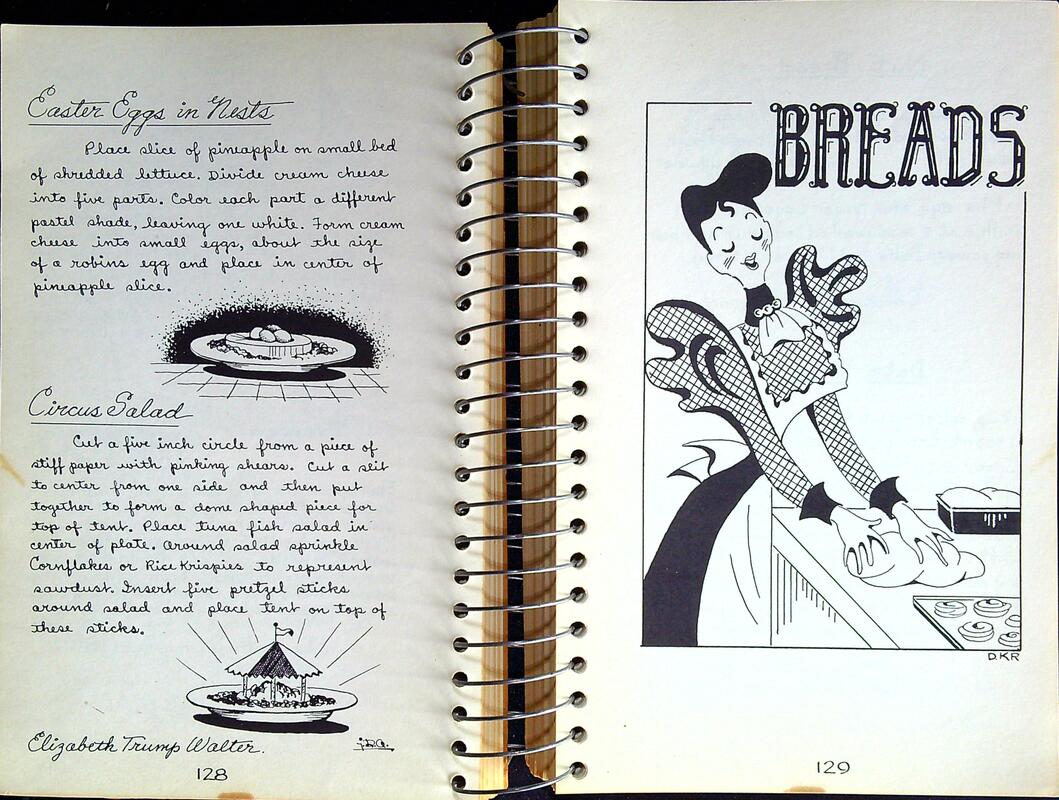

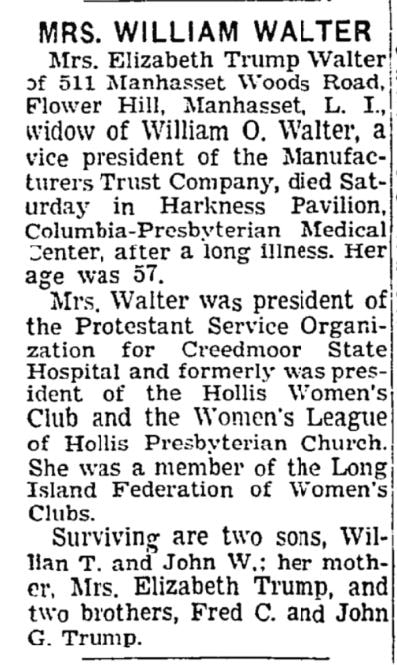

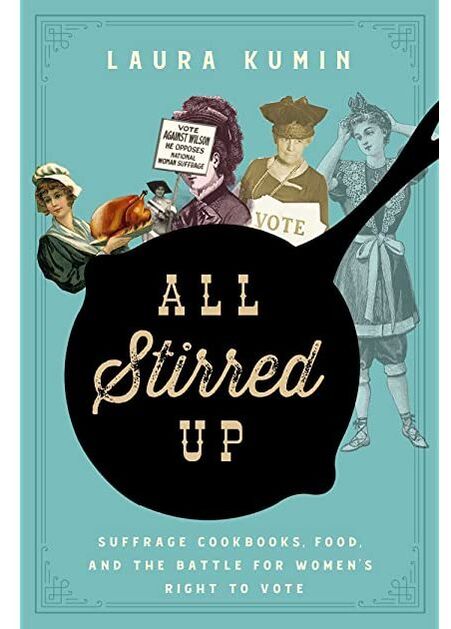

In 1946 the Women's League of the Hollis Presbyterian Church in Hollis, NY published this community cookbook, Hollis Pantry Secrets. Hollis is a neighborhood in Queens County, NY and in the 1940s was a relatively new development of single-family homes that had only been part of New York City since 1898, when it was developed from rural farmland. I was in the process of digitizing the cookbook when I ran across a somewhat familiar name. "Elizabeth Trump Walter." Could it be? Was she related to President Donald Trump? I started digging, but sadly, there wasn't much to find. Elizabeth was born in 1904 to Elizabeth Christ and Frederick Trump (Sr.), German emigrants to the United States. Frederick (sometimes spelled Friedrich) had made his fortune during the Gold Rush with a hotel specializing in alcohol and suites for prostitutes. He returned to Germany in sometime before 1902, only to run into trouble with the authorities, who deemed his emigration illegal because he had not completed his military service. He met and married Elizabeth Christ in 1902 and they moved to New York City. In 1904, homesick Elizabeth convinced him to return to Germany, but due to Frederick's trouble with the authorities over his lack of military service, they could not stay, and returned to New York City in 1905. It is unclear if Elizabeth the younger was born in Germany or not. Her younger brother Frederick Jr. was born in 1905 and John in 1907. Frederick Trump Sr. died of Spanish Influenza in 1918, and the family was soon in trouble financially. Elizabeth Christ Trump decided to continue her husband's work in real estate development, and that her children would be her primary employees. Elizabeth the younger was also the eldest child - she left high school to attend secretarial school so that she could be the accountant for the newly formed E. Trump and Son company. Her youngest brother John was to be the company architect. Fred Jr. the builder. John left the company early on and Fred Jr., with his mother, built E. Trump and Son into a real estate empire. Derailed by the stock market crash of 1929, when E. Trump and Son officially went out of business, by 1934 Fred Jr. managed to finagle his way into a mortgage-servicing contract, and the Trumps were back in the real estate business. The rest is fairly well-known history, including Trump's housing discrimination. But what about Elizabeth? Her history is almost non-existent. She has no Wikipedia page. She isn't even mentioned on her mother's Wikipedia page, despite the fact that Fred Jr. is noted as the "second child" and John the "third." She is mentioned on the Trump family page. We know she married William Walter, who was training to work in a bank, in June of 1929. According to William's 1959 obituary, he was a veteran of World War I who had worked in banks starting as a page boy in 1910. The year he and Elizabeth were married, he was made assistant secretary of the newly formed Manufacturer's Trust. Elizabeth apparently continued in her accounting role after marrying William, but it is unclear whether she left in late 1929 when E. Trump and Son went under, and whether she continued to work under Fred Jr. Elizabeth and William Walter had two children - William Trump Walter, born in 1931, and John Whitney Walter, born in 1934. Both Elizabeth and William Sr. were highly involved in the Hollis Presbyterian Church. He was an elder, she, a member of the Women's League. So it makes sense that Elizabeth would submit recipes for the 1946 cookbook. Here are her recipes: The "Party Suggestions" that start on page 125 is a small section that only contains recipes from Elizabeth Trump Walter! All variations on starter salads (with one exception), probably for ladies' luncheons, but possibly also for themed dinner parties, or even children's parties. South Sea Island Place slice of pineapple in center of a bed of shredded lettuce. Fill hole with cream cheese and put a spring of parsley in cheese to represent palm tree. Cut banana in half lengthwise and then in half crosswise – straight bananas are best – and place these on lettuce sea around pineapple island, cut side up. Cut saltines diagonally in half. Each half makes a sail. Insert tooth pick in corner and stick in banan boat. Cut strips of wax paper about ¾ inch by 1 ½ inches. Fringe and tie around chocolate candy dolls for grass skirt and place under palm tree. Mexican Hayride Force a Ritz cracker on either side of a toothpick for wheels and axle. Make two sets for each service. Fill lettuce cups with crab meat salad and place on top of two sets of wheels and axles. Force animal crackers on either side of a toothpick. This kames a pair of horses. As many pairs of horses as desired may be used. Place thin strips of green pepper from lettuce cups to team of horses for reins. Snow Man Ice cream cone Whipped cream Scoop of vanilla ice cream 3 inch round of sponge cake Cover sponge cake with whipped cream. – Place scoop of ice cream in center of sponge round. Invert cone on ice cream. Make eyes of melted chocolate and use slice of cherry for mouth. Force whipping cream through tube to make ruffling for collar around face. Sail Boats Peel cucumber and cut in half, lengthwise. Scoop out center and mix with salmon salad. Fill mixture in cucumber boat – Place on bed of shredded lettuce for waves. To make sail, cut drinking straw in half. Cut rectangle from stiff white paper and attach to half of straw with scotch tape. Place sail in center of boat. Easter Eggs in Nests Place slice of pineapple on small bed of shredded lettuce. Divide cream cheese into five parts. Color each part a different pastel shade, leaving one white. Form cream cheese into small eggs, the size of a robins egg and place in center of pineapple slice. Circus Salad Cut a five inch circle from a piece of stiff paper with pinking shears. Cut a slit to center from one side and then put together to form a dome shaped piece for top of tent. Place tuna fish salad in center of plate. Around salad sprinkle Cornflakes or Rice Krispies to represent sawdust. Insert five pretzel sticks around salad and place tent on top of these sticks. Her six party suggestions make up the entire "Party Suggestions" chapter. I, personally, would have a hard time cutting saltines in half or forcing toothpicks into crackers, so clearly this sort of thing took a great deal of finesse. Elizabeth Trump Walter died on December 4, 1961, at the age of 57, "after a long illness," just two years after her husband William. Her obituary is on page 37 of that day's New York Times, towards the bottom. She pre-deceased her mother Elizabeth Christ Trump by five years. Ironically, Elizabeth Christ Trump does not have an obituary in the New York Times, she is only listed among the deaths recorded on June 9, 1966 - her notice submitted by the Federation of Jewish Philanthropics. According to Elizabeth's son John Walter's 2018 obituary, the Walters moved to Manhasset, NY toward the end of their lives. They lived in a retirement home built by the Walters and likely Fred Trump, Jr., but died just a few years later. John begun attending the Congregational Church of Manhasset at his mother's behest. Elizabeth Trump Walter was memorialized with a restored organ at the Congregational Church of Manhassett, NY sometime in recent years. Elizabeth Trump Walter rarely shows up in Trump family histories, probably because of her early death compared with the Trump family fortunes. But it was a fascinating project to track down what I could about her. The Hollis Pantry Cook Book has more secrets and famous recipe authors to share, so stay tuned for future blog posts. Have you ever found a famous person's name in a community cookbook? Tell us in the comments! The Food Historian blog is supported by patrons on Patreon! Join us for awesome members-only content like free digitized cookbooks from my personal collection, e-newsletter, and even snail mail from time to time! This article contains Amazon.com and Bookshop.org affiliate links. If you purchase anything from these links, The Food Historian will receive a small commission. All Stirred Up: Suffrage Cookbooks, Food, and the Battle for Women’s Right to Vote, Laura Kumin. New York: Pegasus Books, 2020. 357 pp., $28.95, hardcover, ISBN 978-1-64313-452-9. ,I first learned about cookbooks associated with women’s suffrage thanks to this Atlas Obscura article and I was instantly fascinated. Feminism in the 20th century was often more interested in throwing off the chains of household drudgery than with enticing converts through snacks. But that is precisely the premise of All Stirred Up: Suffrage Cookbooks, Food, and the Battle for Women's Right to Vote, which is why I was so excited that I put it on my Christmas wish list. I was expecting a thorough examination of the suffrage cookbooks, the women who created them, and their place in the movement. Sadly, as a book, All Stirred Up is like an underdone cake – it looks perfect on the outside, but the inside is doughy and disappointing and could have used another 30 minutes in the oven. Laura Kumin is a former lawyer turned cooking educator and food writer. She does not have a historical background, and, as is the case with many non-historians who write food history, it shows. All Stirred Up begins, even before the introduction, with a lengthy timeline. While I find timelines to be incredibly useful, especially when dealing with complex chronology, starting the book with one was not a choice I would have made. It is confusing to the reader, who is presented lengthy and disparate facts without context or introduction. A lack of context is a theme for the book. Kumin’s introduction is part explanation of her interest in suffrage cookbooks and part layout of her main argument. She makes a compelling case that modern takes on suffrage history have largely ignored the role of cookbooks in converting skeptics to the cause. Unfortunately, this argument is not often revisited in the subsequent chapters. Most of the chapters are quite brief, some as few as eight pages, and while historical overviews abound, actual analysis is lacking. Taking up the most space are the recipe sections that follow each chapter, organized by type. Although these recipes are directly taken from the suffrage cookbooks, with modern adaptations designed by Kumin, there is no context for any of the recipes and no dates listed. Most recipe sections draw from multiple suffrage cookbooks without differentiating between them, beyond noting where the originals came from. We do not know why Kumin chose these particular recipes, how they reflected the cookbooks and times from whence they came, or even what, if any, relevance they had to the suffrage movement. For many chapters, the number of pages devoted to recipes outweigh the pages devoted to history. As for the history itself, most of it is shallow summaries meant to orient the reader to the basics of suffrage history, home economics and food science, and basic culture of the period. While this context is useful for non-historians, it seems to come at the expense of historical analysis. In addition, the chronology of the book is all over the place. The book begins in 1848, with an exercise in “time travel” in which Kumin writes in the present tense. Then zooms ahead to the Progressive Era and back again several times. At the end of Chapter 3, we’re already at the 19th Amendment in 1920, an achievement which is not really revisited for the rest of the book. Throughout the book, the suffrage movement in one decade is conflated with the same movement decades later. Little attention is paid to the context of national culture on the way in which the women's suffrage movement was operated, despite the fact that it was under operation, in one way or another, for over 70 years. Missed opportunities to make connections to other major movements, including abolitionism, Temperance (which is dismissed as detrimental to the cause, p. 78-79), Progressive reform, government regulation, etc., abound. Chapters 3, 4, and 6 are the strongest, content- and argument-wise. In Chapter 3, “From Seneca Falls to the Ballot Box,” Kumin examines the suffragists themselves and the post-Civil War resurgence of the movement. To her credit, she makes a point of mentioning African American suffragists and their shameful treatment by mainstream white suffragists, as well as male allies and the “antis” – anti-suffragists. However, points that needed more analysis were often presented as literal sidebars in the text. For instance, noted suffrage ally Frederick Douglass, instead of being included in the main text, receives a short summary in a gray box. The Beecher family get similar treatment in a sidebar about how the movement split families. Catharine Beecher, a fervent anti-suffragist, was a cookbook author and young women’s educator of some renown and who, despite conflicting ideas about suffrage, nonetheless co-wrote The American Woman’s Home with her suffragist sister. Cookbook author, fervent abolitionist, and Native American rights activist Lydia Maria Child is mentioned in a quotation, but otherwise ignored. These are just a few of many missed opportunities to engage with the subject matter more deeply – discussing how both suffragists and “antis” used women’s work and the home in their arguments for and against suffrage. Chapter 4, “We Can Peel Potatoes and Fight for the Vote, Too! Suffrage Strategies and Battle Tactics” is the strongest chapter in the book, and one of the few that cites primary sources in the endnotes. Discussing the divergent tactics between “mainstream” and “militant” suffragists, Kumin compares the mainstream work of the cookbooks, cafeterias, the “doughnut campaign,” a “Pure Food” storefront, and cooperating with agricultural extension, to the militant tactics of parades, protests, arrests, and hunger strikes. Unfortunately, she does not define who exactly is “mainstream” and who is “militant,” except to note differing tactics. Kumin argues that the more mainstream feminists were more successful in changing hearts and minds, but presents little evidence to back up this claim. In addition, despite covering the bulk of the Progressive Era, the chapter mentions, but gives little context to agricultural extension, the Temperance movement, home economics, World War I, and women’s clubs. An overview of home economics and food science comes in the following chapter, “Revolution in the Kitchen.” Chapter 6 finally addresses the cookbooks themselves, with an overview of how they were financed, celebrity contributors, and how the recipes included were reflective of the periods in which they were published. The cookbooks are still dealt with in generalizations, however, and their individuality is lost in the mix. The section on celebrities, although interesting contains another missed opportunity, as Kumin mentions one recipe contribution from noted feminist Charlotte Perkins Gilman, but not her dislike of cooking. In the section on funding, Kumin clearly notes that the cookbooks were usually designed as fundraisers for the organizations, a fact that belies her argument that cookbooks were meant to convert, though she does note they were sometimes also used as enticing premiums for subscriptions. Chapter 7 is a brief discussion of how suffragists used dinners and entertaining to support the cause. All Stirred Up ends without a clear conclusion, instead relying on Chapter 8, “What Suffrage Means for Us,” an eight-page summary of women in American politics since 1920. This final chapter makes no clear reference to the influence of the cookbooks that purportedly drove the suffrage movement and does not sum up the arguments outlined in the introduction. It is followed by 28 pages of dessert recipes. There is no explanatory postscript, only Kumin’s acknowledgements. In all, All Stirred Up does make a good point about the role of suffrage cookbooks in the movement, but it fails to back up its few arguments convincingly, particularly in light of the use of community cookbooks as fundraising tools, rather than modes of conversion to the cause. Instead of concentrating the bulk of her argument into Chapter 4, Kumin would have had a much more compelling book had she spread that argument throughout all the chapters, addressing the role of domesticity from the perspectives of both the suffragists and the antis. More primary source analysis would have enriched the narrative. Looking at the writing of major suffrage leaders to determine their personal opinions on cooking and domesticity would have added depth to her arguments. Examining the cookbooks themselves, their recipes, and the organizations and women that produced them as a chronological accounting of the movement, would have added greatly to the coherence and context of the book. Had the recipe sections been introduced by era, with headnotes and historical context for each recipe, their inclusion would have made the book both stronger and appealing to the general public. Ultimately, the book feels as though it was rushed to print, possibly to coincide with the centennial anniversary of the 19th Amendment in 2020. If you are unfamiliar with basic suffrage and food history, this may provide some good historical summaries and Kumin’s research on the 1909 Washington Women’s Cook Book is particularly strong. But, if you were hoping for a well-written, well-organized examination of the role of food in the suffrage movement and the influence of suffrage cookbooks, as I was, you’ll be sorely disappointed. I can only hope that future historians can expand on Kumin’s work. If you'd like more food history book reviews, check out the Book Review category of this blog. The Food Historian blog is supported by patrons on Patreon! Join us for awesome members-only content like free digitized cookbooks from my personal collection, e-newsletter, and even snail mail from time to time! |

AuthorSarah Wassberg Johnson has an MA in Public History from the University at Albany and studies early 20th century food history. Archives

July 2024

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed