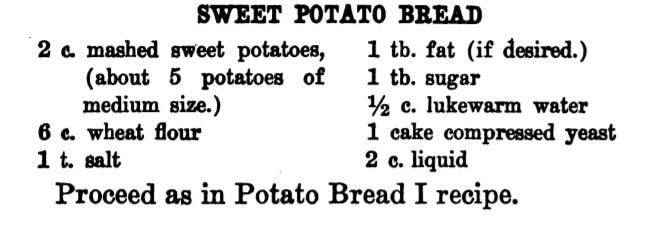

"Wheat Substitutes" as illustrated in "Liberty Recipes" (1918). Caption: "Some of the cereals, meals and flours used as substitutes as shown above (in order) are: soy bean meal, kaferita flour, ground oats, oatmeal, potato flour, buckwheat, barley, cornstarch, corn flour, corn meal, grits, hominy, and rice." Last time for World War Wednesday, we discussed how important it was during the First World War to save wheat and reduce bread consumption. During the war a number of cookbooks were published to help Americans reduce their consumption of wheat, meat, butter, and sugar and how to go without or reduce the use of scarce or expensive ingredients like eggs. When it came to bread, there were very few recipes that used no wheat flour at all, but instead most recipes used alternative grains like barley, rye, corn, and oatmeal or other ingredients like mashed potatoes or cooked rice to reduce the overall ratio of wheat flour used. Liberty Recipes was written by Amelia Doddridge, who the title page lists as "Formerly, Instructor of Cooking, Manual Training High School, Indianapolis, Indiana; and Emergency City Home Demonstration Agent, Wilmington, Delaware. Now, Head of Home Economics Department, Wooster College, Wooster, Ohio." The book was published by Stewart & Kidd Company in Cincinnati, Ohio in 1918. I wasn't able to find much more on Amelia herself. I found a dissertation that notes that several classes in food and household management at Wooster College were taught by Amelia, who was then Acting Dean of Women. But those classes were apparently only offered temporarily during the war, "These particular classes were offered only between 1918-1919 during the "confused period of war, fuel shortages, S.A.T.C., Spanish flu, and demobilization." Which seems to indicate that Amelia herself may not have survived as an instructor after the war. A reference from 1922 places an Amelia Dodderidge in Montevallo, Alabama as head of the home economics department "at Montevallo," which possibly meant the college located there. I found a reference to an Amelia Doddridge teaching high school home economics in Ohio in 1924. And another to an Amelia Dodderidge working at a Farm Bureau in Pennsylvania and/or as a county home economics representative, and/or as the Home Economics Extension representative from the state college, all in Pennsylvania, all in 1926. In 1929 there's a Miss Amelia Dodderidge in Modesto, California, acting as an "assistant home department agent." By the 1950s she appears to be living, retired, in Franklin, Indiana and throughout the late 1950s and 1960s there are numerous articles in the Franklin Star authored by Amelia Dodderidge. A 1962 article indicates she was working for the Methodist Home (likely a home for the elderly) in Franklin, IN and, indeed, most of the articles she published in the Franklin Star were called "The Home Window," apparently reporting on the activities and events of the Methodist Home. The trail runs cold at the very end of 1963. The last reference to Amelia is published on December, 31. It's unclear whether the newspaper simply did not run her column again or if the newspaper itself ceased publication or if it simply wasn't digitized past 1963. Although it's tough to prover all these Amelia Dodderidges were the same person, it is very likely. Amelia apparently continued her home economics work throughout her life, even after "retirement." But back to Liberty Recipes. The cookbook is a fascinating one, and I particularly love some of the slogans listed in the frontspiece; my two favorites are "Place meat and buns behind the guns" and "Husband your stuff; don't stuff your husband." Also interesting are the references in the foreword to the cookbook itself being much more convenient for reference by housewives rather than taking "too much trouble to hunt in a pile of leaflets for the recipes she wishes at the particular time she needs it" - a reference to the numerous bulletins and cookbooklets being published by the USDA and other government agencies. In addition, the foreword claims that although the recipes listed are designed for the "present emergency," "they should be usable and still practical even after the war clouds pass and Freedom is ours." There are numerous bread recipes in the cookbook - both yeast and quick breads. In addition, the cookbook focuses on meatless and meat-saving recipes, a few salads, and numerous sugarless, low-sugar, and wheat- and fat-saving dessert recipes. This recipe for Sweet Potato Bread seemed quite modern, and a fun recipe to share in the lead-up to Thanksgiving. Although I have not had time in a while to bake yeast bread, I thought I would share it anyway. Maybe I can take a stab over the holiday. World War I Sweet Potato Bread (1918)The original recipe makes references to other recipes, so I've combined the instructions for your convenience. A cake of yeast is about the same as dried yeast packets that are sold today. Although you can try it with RediRise or similar fast-acting yeast, I recommend plain ol' active dry yeast. 2 cups mashed sweet potatoes (about 5 potatoes of medium size.) 6 cups wheat flour 1 teaspoon salt 1 tablespoon fat (if desired.) 1 tablespoon sugar 1/2 cup lukewarm water 1 cake compressed yeast (or 1 envelope active dry yeast) 2 cups liquid Use the potato water for the liquid. Pour it gradually over the hot mashed potatoes. When lukewarm add the softened yeast, salt, sugar, and fat. Stir in the rest of the flour gradually. When the dough becomes too stiff to stir, work in the remainder of the flour by kneading with the hands. It may take a little more flour or a little less depending upon the kind of flour used. The dough should be of such a consistency that it will not stick to the hands or to the bowl. Knead 10 or 15 minutes until the dough is smooth and elastic. Place in a bowl, cover, and keep it in q warm temperature (75 to 85 F). When risen twice its bulk, cut down and knead again. Then shape into loaves, place in greased pans, and set in a warm place. When light and doubled in bulk it is ready to bake. To prevent a crust from forming over the top of the loaf while rising, rub the surface with a little melted fat. Watch the rising and put into the oven at the proper time. If risen too long, it will make a loaf full of holes; if not risen enough, it will make a heavy bread. Bake 45 minutes to 1 hour in a moderately hot oven (375 to 400 F). If oven is too hot, the crust will brown before the heat has reached the center of the loaf and will prevent further rising. The loaf should raise well during the first 15 minutes of baking; then it should begin to brown, and continue browning for the next 15 or 20 minutes. The last 15 to 30 minutes, it should finish baking and the heat may be reduced. When done, the bread will not cling to the sides of the pan. If a tender crust is desired, brush the bread over with a little melted fat as soon as it is taken from the oven. If you end up making this recipe, let us know in the comments how it turned out! There are lots of other interesting recipes to be had in Liberty Recipes, including a potato biscuit pie crust recipe, buckwheat spice cake, and cornmeal gingerbread, to name a few! Are there any recipes in there that you want to try? The Food Historian blog is supported by patrons on Patreon! Patrons help keep blog posts like this one free and available to the public. Join us for awesome members-only content like free digitized cookbooks from my personal collection, e-newsletter, and even snail mail from time to time! Don't like Patreon? Join with an annual membership below, or just leave a tip!

0 Comments

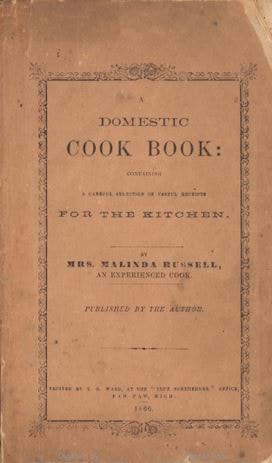

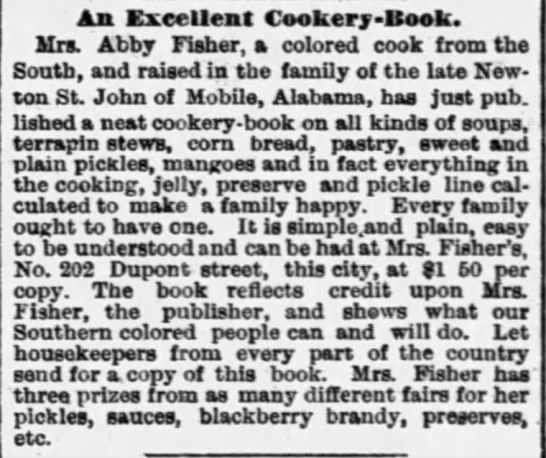

Throughout the 19th century, white women used their domestic assets to pick up the slack left by disabled or deceased husbands - homes became boarding houses and tea rooms and domestic skills were translated into magazine articles and cookbooks. But free Black women in the 19th century did not have as many assets. And even when they did, these assets were often taken from them, and a racist and sexist judicial system gave them little recourse to recover property. Enslaved women freed by the Emancipation Proclamation had their freedom, but little else. The promised 40 acres and a mule never materialized. Despite these often difficult starts, many free and formerly enslaved women of color used their wits and skills to make their own way in the world. Often relegated to service jobs in households, many women created their own small businesses to avoid working for wages - tea rooms, boarding houses, laundries, seamstress and millinery shops, catering, etc. Most of these jobs had low startup costs and could be done from home, allowing for the care of children and family members. Many women also worked as professional cooks for taverns and hotels, a job that held more promise of profit and respect than working in a private household. The vast majority of women working in these fields remain hidden from history - unnamed and un-written-about. But some women of color have managed to make their mark on food history. Here are a few of their stories. Anne Northup - Twelve Years AloneAnne Northup was my first real encounter with the stories of adversity and perseverance many Black women faced throughout the 19th century. I attended a special program at the Morris-Jumel Mansion in New York City with a historic dinner recreated by The Food Griot - Tonya Hopkins. Anne Hampton was born in 1808 in upstate New York. A free woman of color, she married Solomon Northup in the 1820s and in 1834 they sold their farm and moved to Saratoga. Solomon often worked as a fiddler and Anne worked as a cook and kitchen manager at hotels in the spa resort town. She was working at the Pavilion Hotel in Saratoga when she met wealthy white New Yorker Eliza Jumel in 1841. Divorcee/widow of Aaron Burr, Madame Jumel convinced Anne to come south and serve as a cook in her household. Anne sent her eldest daughter Elizabeth to Manhattan with Jumel, but waited until later in the year to come south herself, likely finishing out the busy tourist season. Earlier that summer of 1841, Anne's husband Solomon had answered an advertisement looking for musicians for a job in Virginia. An accomplished violinist, Solomon had answered the advertisement and traveled south. He was captured and sold into slavery, spending the next twelve years enduring brutal conditions on a Louisiana sugar plantation. Anne was left to fend on her own. After a year in Eliza Jumel's household, Anne and some (but not all) of her children returned to Saratoga, where they stayed until 1850, when they moved to Glens Falls and Anne continued her hotel work. They were not reunited with Solomon until 1853. He wrote a book about his experiences - Twelve Years a Slave. We lose track of Solomon Northup in the 1860s and his death date is unknown, although Anne and her children continue to live in New York. To learn more about the Northup family, read this excellent account by historian David Fiske. Anne Northup died on August 8, 1876 in Moreau, New York. Although she leaves behind no documentation of the food she cooked, given her positions in fashionable resort town hotels and wealthy households, she was likely very skilled in a variety of foodways. To me, she represents how many free women of color made their way in the world on the strength of their cooking skills, even in the face of extraordinary adversity. Malinda Russell & Her Union PrinciplesIn 2000, Jan Longone ran across a slim, crumbling cookbook wrapped in brown paper at the William L. Clements Library at the University of Michigan in Ann Arbor, where she is curator of American culinary history. That cookbook, A Domestic Cookbook, published in 1866 by a woman named Malinda Russell, turned out to be the earliest known cookbook published by an African American woman. The cookbook has since been digitized, and when I read it for the first time the other day, I was struck by the incredible hardship Russell had to overcome in her life. In the autobiographical account that explains why she wrote the cookbook, Russell recounted the many setbacks in her life. Born free in Tennessee, at age 19 she set out to emigrate to Liberia, a promise of life free from the racism and oppression that continued to plague free Black communities in the North. But along the way, she was robbed by someone from her party, and was forced to stay in Virginia, where she made a living as a cook and a nurse. There, she married Anderson Vaughn, and they had a son together, but Vaughn died just four years later, leaving Russell a widow with a handicapped son. She moved back to Tennessee and opened a boarding house in a town that featured springs as a tourist attraction. She later opened a pastry shop in that same down and had saved up a sum of money to support herself and her son. But in early 1864, she was attacked and robbed by a "guerrilla party," likely Confederate soldiers. She and her son fled Tennessee during the height of the Civil War. Although Tennessee was a Union state, its proximity to the border meant it was not safe for Russell. She made her way to Michigan, enduring several attacks along the way, and went on to start over, again, in a new state. In May, 1866, she published A Domestic Cookbook. She closed her introduction stating that she hoped the sale of the cookbook would help her raise funds to return to Tennessee and reclaim some of her lost property when peace was restored. We do not know if she ever made it home to Tennessee, or really much else about her at all, although Jan Longone has worked to find more about her. According to Russell herself, "I have learned my trade of Fanny Steward, a colored cook, of Virginia, and have since learned many new things in cooking." She also indicated her cookbook was organized along the lines of Mary Randolph's The Virginia Housewife (1824). Malinda Russell reset much of the conventional wisdom about Black cooking heritage at the time it was rediscovered. But her cookbook is not much different from any other cookbook of the period - reflecting her experience as a boarding house owner and cook, cooking for the public and likely for audiences diverse in race and socioeconomic status. It also knows its audience, consisting largely of dessert and preserves recipes. These were commonly featured in published cookbooks because they were more complex than the everyday cooking of meat and vegetables and less likely to be familiar to ordinary cooks. Her cookbook contains everything from the humble "Baked Indian Meal Pudding" and 'Sliced Sweet Potato Pie," to the exquisite "Floating Islands" and "Charlotte Russe." For me, the most striking thing about Russell is not the content of her cookbook, but rather the fact that it exists at all - a testament to her difficult life and the grit she used to persevere. What Abby Fisher Knew "Pickles and Fruit. The purest home-made Pickles and Preserves of all kinds, put up in the good old Southern style. A liberal discount to the trade. Address, Mrs. Abbey Fisher and Husband, 569 Howard St. San Francisco." Advertisement from the December 13, 1879 issue of "The Placer Herald," published in Rocklin, CA. Unlike Anne Northup and Malinda Russell, Abby Clifton was born into slavery in 1831 in South Carolina to a white father and an enslaved mother. It is unclear when gained her freedom, but by 1860 she had moved to Alabama and married Albert Fisher. In 1877, they emigrated to California and by 1880, Abby and Albert were in San Francisco, where the 1880 Census listed Abby as a "cook" and Albert as a pickle and preserve manufacturer. But this attribution was likely due to sexism common among census takers. In reality, it was Abby who was manufacturing pickles and preserves - as listed in an 1882 San Francisco directory. Albert was listed as a porter. Abby leveraged her expertise in pickles and preserves to reach the highest echelons of San Francisco society. She was awarded a diploma at 1879 Sacramento State Fair. At the 1880 San Francisco Mechanics Institute Fair, she won a bronze medal for her pickles and preserves. Although she and Albert could not read or write, in 1881 she published the cookbook, What Mrs. Fisher Knows About Old Southern Cooking, Soups, Pickles, Preserves, Etc. with assistance from white friends who helped her translate and transcribe her memorized recipes into cookbook format. The book does not contain just pickles and preserves, although they and her famous blackberry cordial certainly make a showing. The title inclusion of "Old Southern Cooking" is certainly apt, given recipes for "Maryland Beat Biscuit," "Plantation Corn Bread," "Ochra Gumbo," "Creole Chow Chow," "Sweet Potato Pie," and "Peach Cobbler." But it also includes typical British-American foods popular in the Northeast and throughout the United States, including "Sally Lund" bread, "Jumble" cookies, "Sauce for Suet Pudding," "Rhubarb Pie," (rhubarb grows poorly in the South, needing below freezing temperatures), three different kinds of "Sherbet," "Yorkshire Pudding," and "Terrapin Soup." In short, her cooking is more representative of broad American style cooking of the period, with some Southern flavor, rather than stereotypically "Southern" (i.e. Black) cooking. The interest in Southern cooking, as evidenced by the marketing of her book, was likely part of a reaction to the Civil War and Reconstruction. Historian Megan Elias has written about "Lost Cause cookbooks" in which white Americans romanticized the "good old days" of slavery and subservient Black folks with "magic" cooking skills. It is possible that Abby Fisher's cookbook was swept up in the wave of racist nostalgia. But it is also possible that Abby's cookbook was simply a reflection of the interest in California residents in the cuisines of many newly arrived emigrants of all cultures and backgrounds. This seems to be the case in one announcement, published in the San Francisco Examiner on July 11, 1881. It reads: "An Excellent Cookery-Book. "Mrs. Abby Fisher, a colored cook from the south, and raised in the family of the late Newton St. John of Mobile, Alabamaa, has just published a neat cookery-book on all kinds of soups, terrapin stews, corn bread, pastry, sweet and plain pickles, mangoes and in fact everything in the cooking, jelly, preserve and pickle line calculated to make a family happy. Every family ought to have one. It is simple and plain, easy to be understood and can be had at Mrs. Fisher's, No. 202 Dupont street, this city, at $1.50 per copy. The book reflects credit upon Mrs. Fisher, the publisher, and shows what our Southern colored people can and will do. Let housekeepers from every part of the country send for a copy of this book. Mrs. Fisher has three prizes from as many different fairs for her pickles, sauces, blackberry brandy, preserves, etc." Although we may never know how many copies Abby sold, the cookbook seemed to garner positive reviews. For several weeks in 1881, she (or the publisher) advertised it in the Oakland Tribune (see below).  "Mrs. Abby Fisher's, Southern Cookery book on soups, terrapin stews, sweet and plain pickles, mangoes, preserves, corn bread; price $1.50; 202 Dupont st., San Francisco. jy11-1m." Advertisement for Mrs. Fisher's cookbook in the "Oakland Tribune," published July 11, 1881, but running for several weeks prior and after. In the 1890 San Francisco directory, "Mrs. Abbie Fisher" was still listed as "mnfr. pickles and preserves," but it is unclear what happened after that. Her exact death date is also unknown. No known obituary was published. After the Great San Francisco Fire of 1907, reference to Abby and her cookbook all but disappeared until a copy surfaced in 1984 at a Sotheby's auction in New York City. The Schlesinger Library purchased it and at the time it was thought to be the first cookbook published in the United States by a Black woman, until Malinda Russell toppled Abby from her throne in 2000. Like Malinda and Anne, Abby used her cooking skills to make her own way in the world - supporting her family and showcasing her talents. Ghosts in the KitchenOf course, we know about these women because they left a written record. We know about Anne through her husband Solomon and his memoir, Twelve Years a Slave and the records of Eliza Jumel. We know about Malinda because of her cookbook and the autobiography she includes in it. And we know about Abby because of her cookbook and her existence in newspapers and city directories. But there were tens of thousands of women of color making their own way on the strength of their culinary skills, just like these women, throughout the 19th and 20th centuries. Ashbell McElveen called James Hemings the "ghost in America's kitchen," but he wasn't the only one. Enslaved women and men shaped American food profoundly. And women of color - enslaved, freed, and born free - left their mark as well. Because I know how history works, I am hopeful that more records and cookbooks of cooks of color - published or not - will continue to show up in the coming decades. And when they do, I know they'll help us better understand how our food got to be the way it is, and where it can go in the future. Further ReadingAnne Northup:

Malinda Russell:

Abby Fisher:

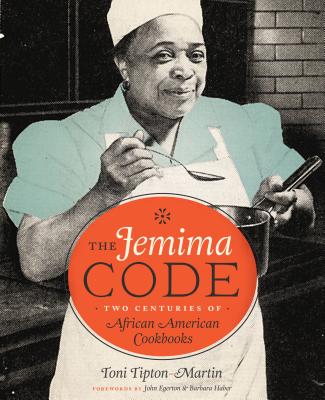

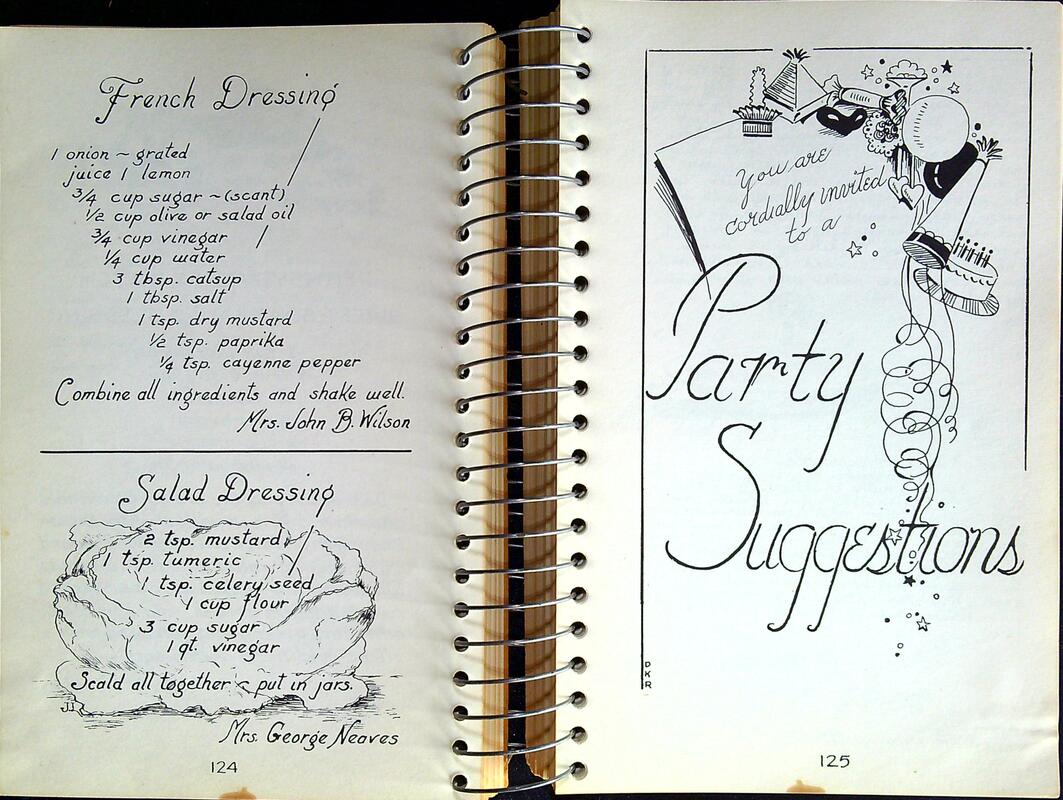

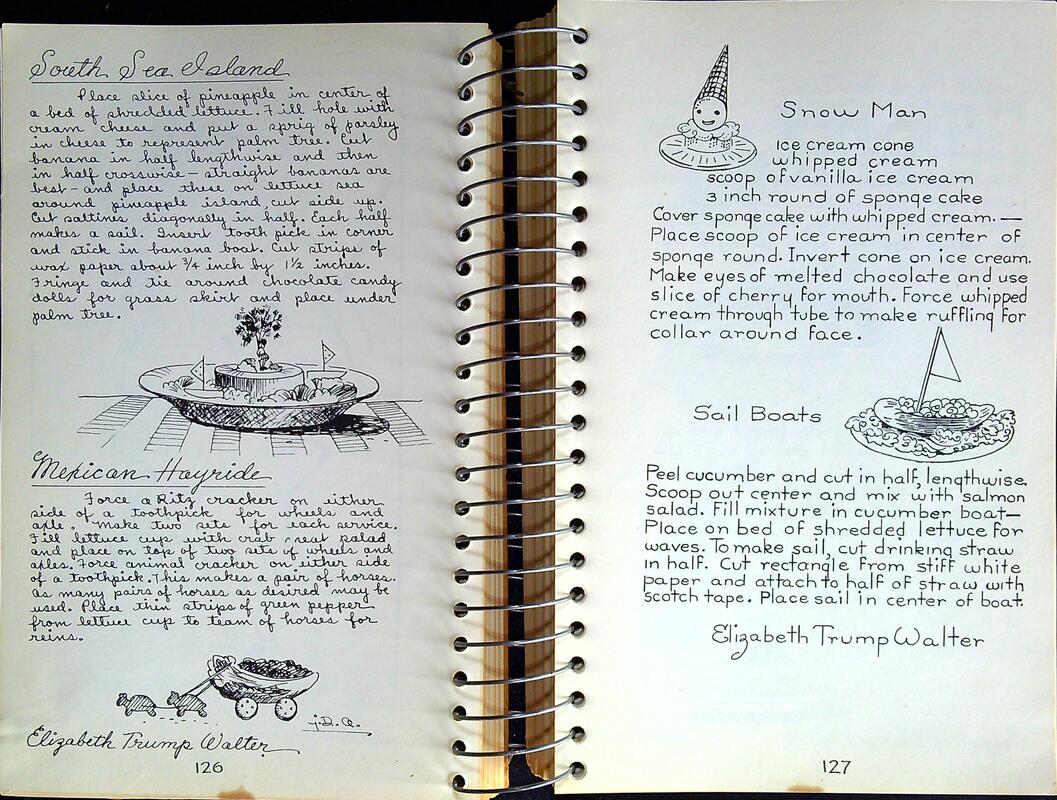

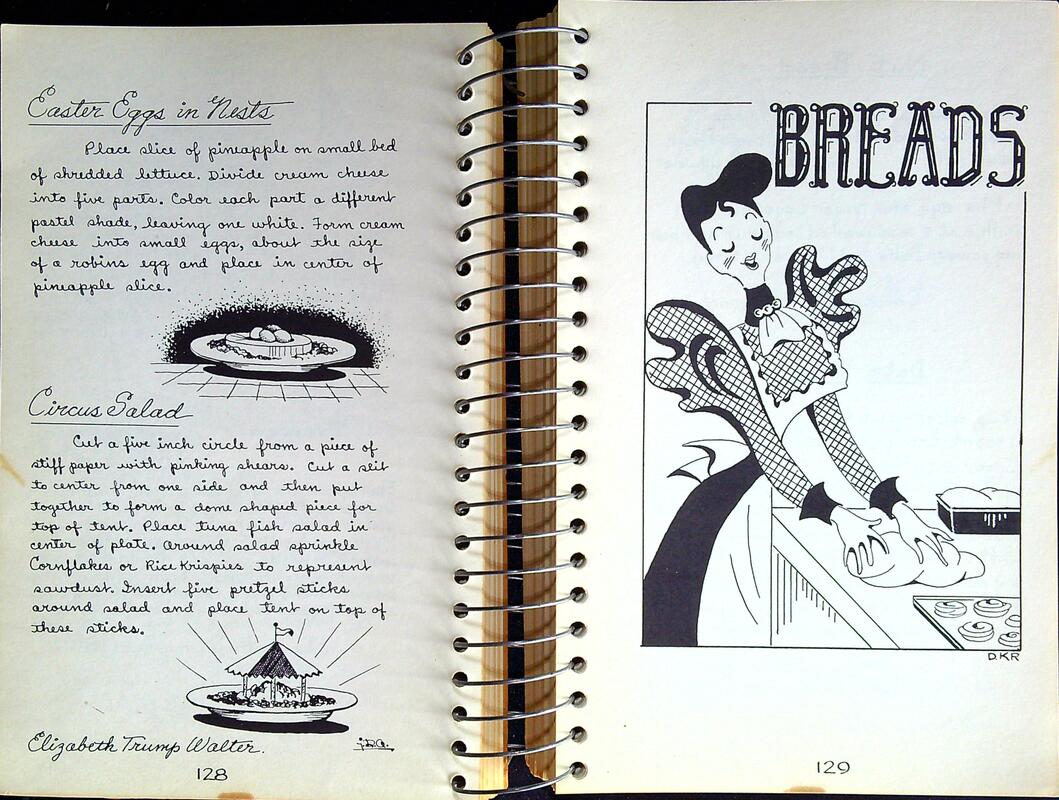

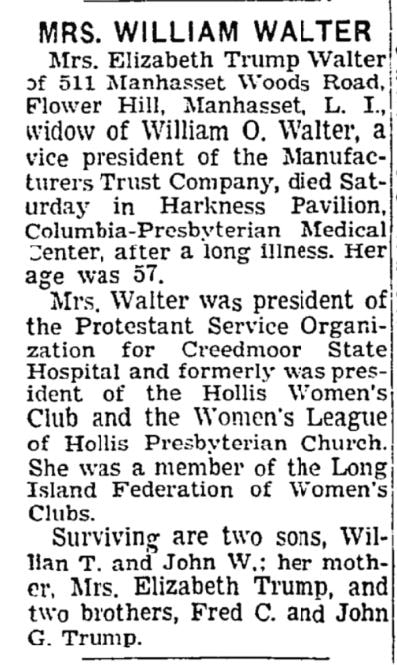

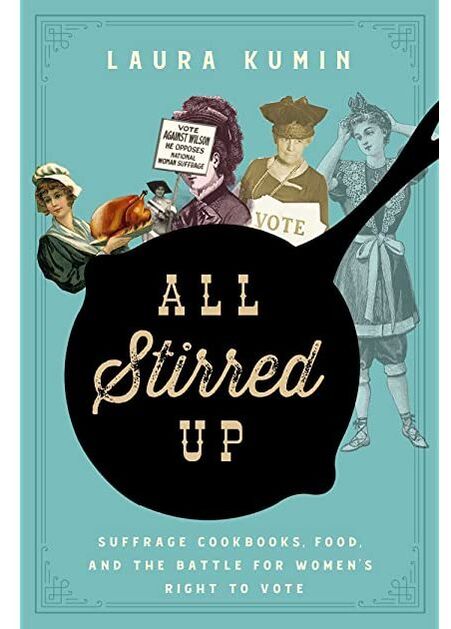

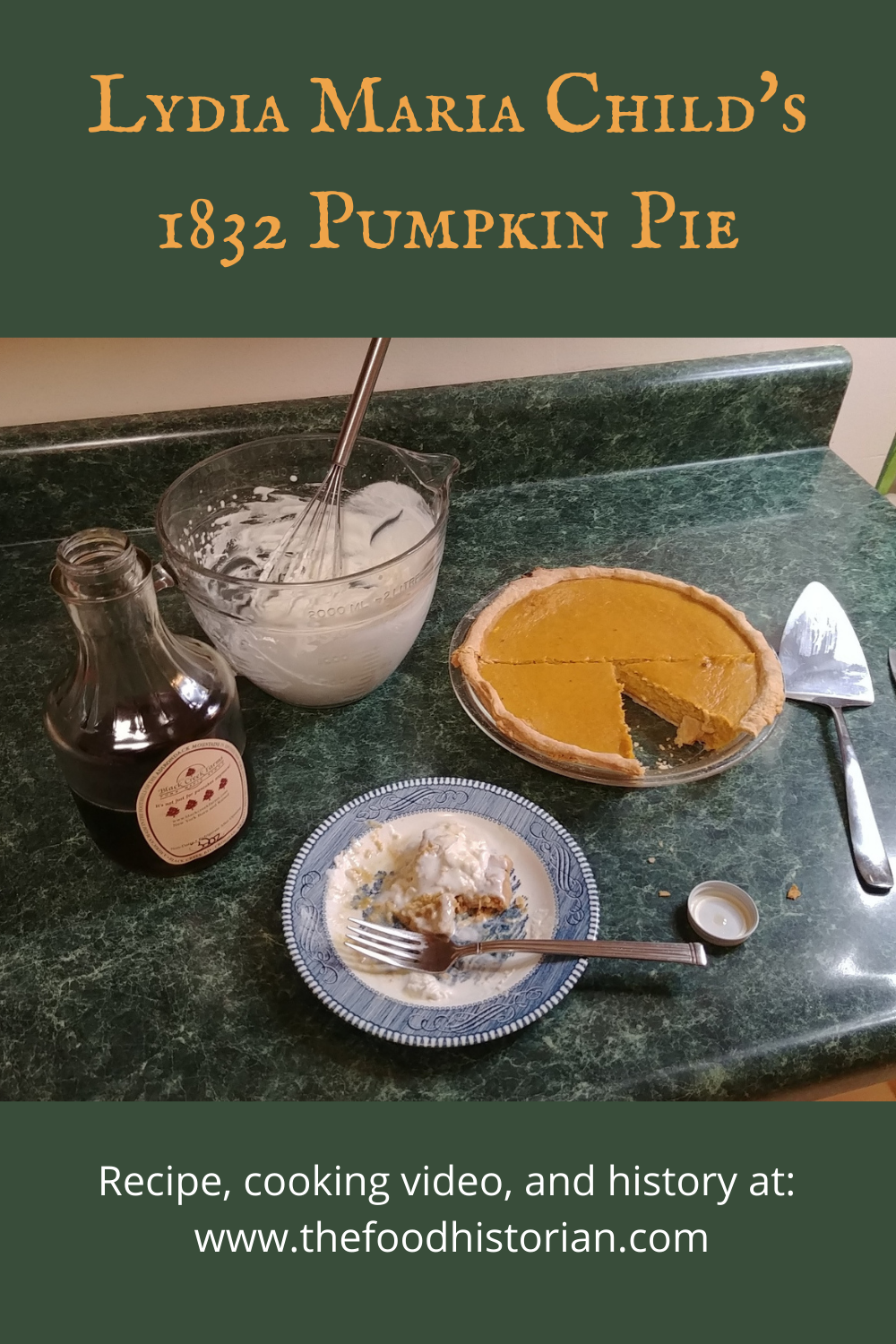

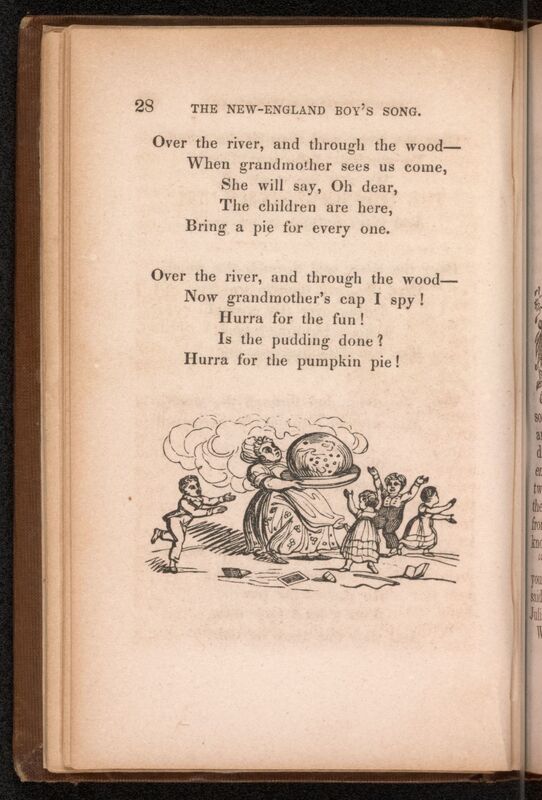

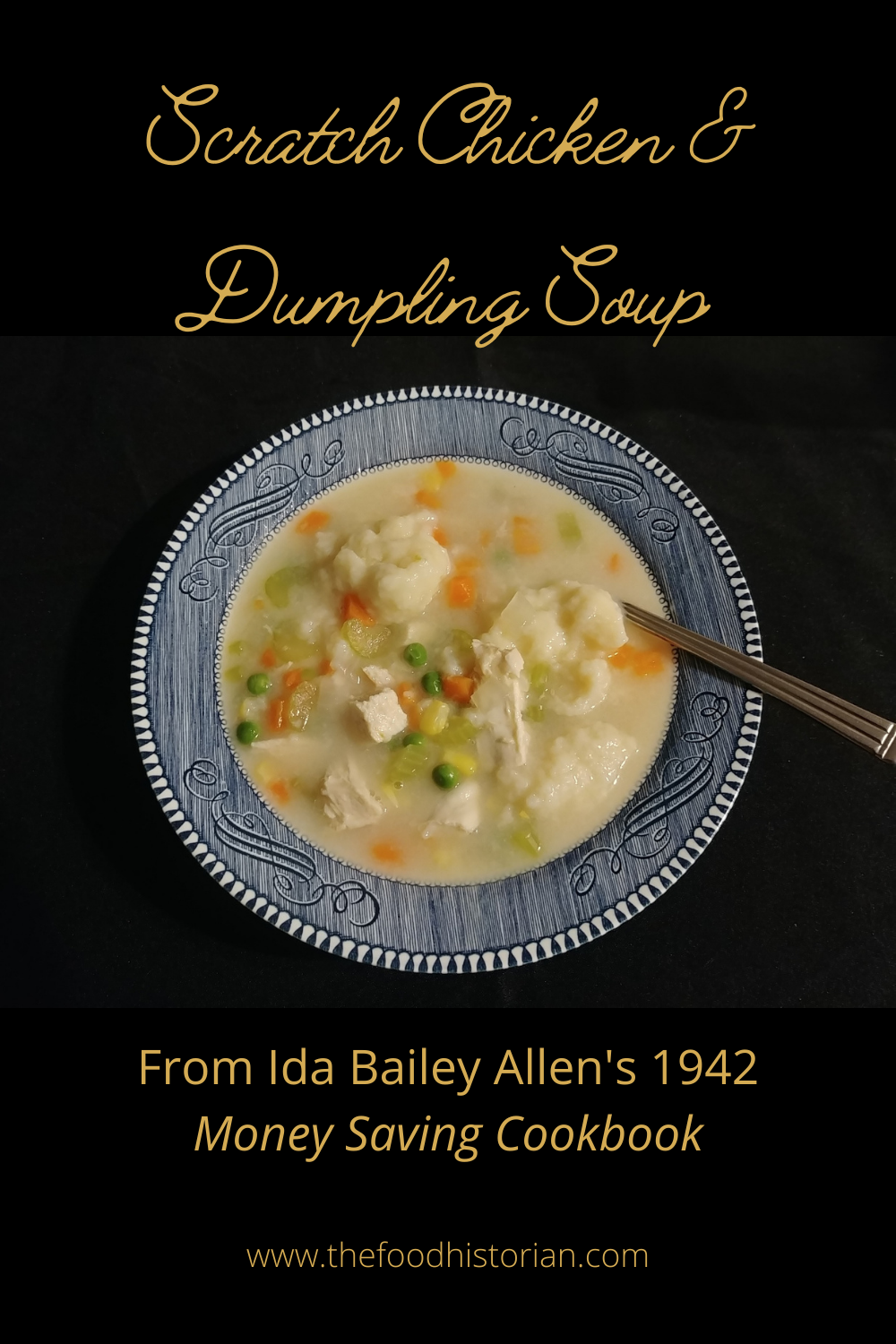

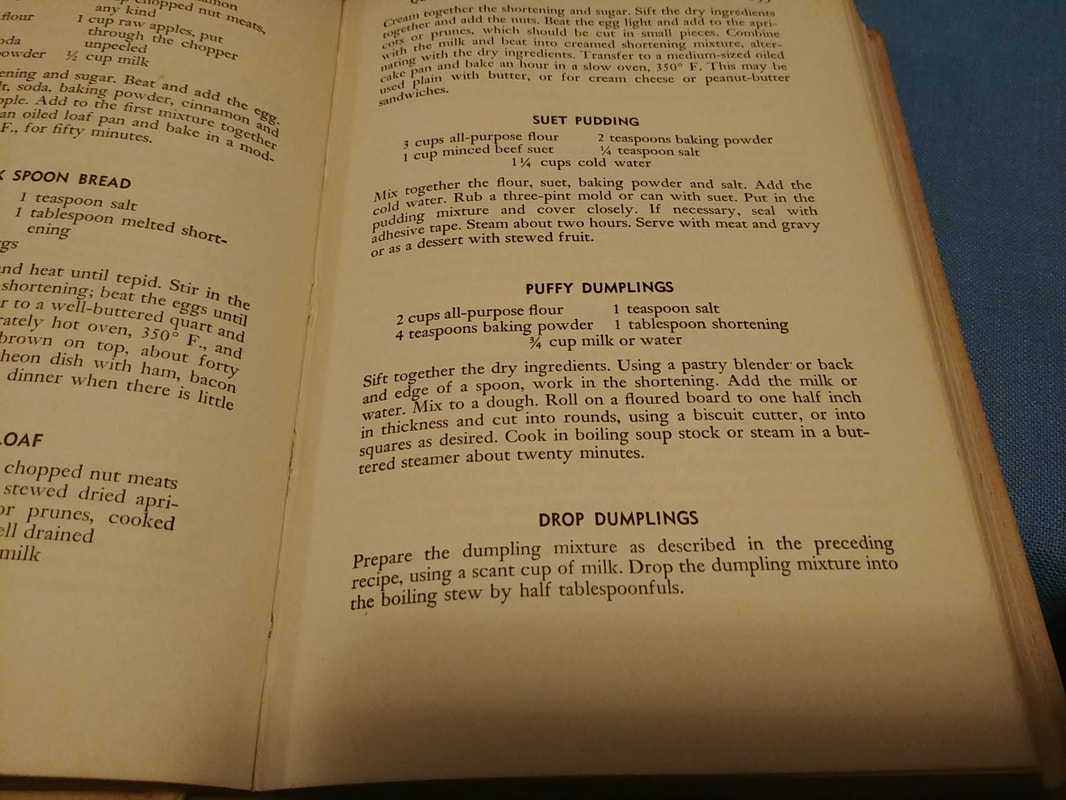

The Jemima CodeThe Jemima Code: Two Centuries of African American Cookbooks, Toni Tipton Martin. University of Texas Press, 2015. ISBN 0292745486. This article contains Amazon.com and Bookshop.org affiliate links. If you purchase anything from these links, The Food Historian will receive a small commission. If you want to know more about African American cookbooks, I recommend Toni Tipton Martin's The Jemima Code: Two Centuries of African American Cookbooks. Although the information for each entry is sadly quite brief, it is nonetheless an important, enlightening, and beautifully produced catalog of all the known cookbooks authored by African Americans (real and fictional) in the United States. The Food Historian blog is supported by patrons on Patreon! Join us for awesome members-only content like free digitized cookbooks from my personal collection, e-newsletter, and even snail mail from time to time! In 1946 the Women's League of the Hollis Presbyterian Church in Hollis, NY published this community cookbook, Hollis Pantry Secrets. Hollis is a neighborhood in Queens County, NY and in the 1940s was a relatively new development of single-family homes that had only been part of New York City since 1898, when it was developed from rural farmland. I was in the process of digitizing the cookbook when I ran across a somewhat familiar name. "Elizabeth Trump Walter." Could it be? Was she related to President Donald Trump? I started digging, but sadly, there wasn't much to find. Elizabeth was born in 1904 to Elizabeth Christ and Frederick Trump (Sr.), German emigrants to the United States. Frederick (sometimes spelled Friedrich) had made his fortune during the Gold Rush with a hotel specializing in alcohol and suites for prostitutes. He returned to Germany in sometime before 1902, only to run into trouble with the authorities, who deemed his emigration illegal because he had not completed his military service. He met and married Elizabeth Christ in 1902 and they moved to New York City. In 1904, homesick Elizabeth convinced him to return to Germany, but due to Frederick's trouble with the authorities over his lack of military service, they could not stay, and returned to New York City in 1905. It is unclear if Elizabeth the younger was born in Germany or not. Her younger brother Frederick Jr. was born in 1905 and John in 1907. Frederick Trump Sr. died of Spanish Influenza in 1918, and the family was soon in trouble financially. Elizabeth Christ Trump decided to continue her husband's work in real estate development, and that her children would be her primary employees. Elizabeth the younger was also the eldest child - she left high school to attend secretarial school so that she could be the accountant for the newly formed E. Trump and Son company. Her youngest brother John was to be the company architect. Fred Jr. the builder. John left the company early on and Fred Jr., with his mother, built E. Trump and Son into a real estate empire. Derailed by the stock market crash of 1929, when E. Trump and Son officially went out of business, by 1934 Fred Jr. managed to finagle his way into a mortgage-servicing contract, and the Trumps were back in the real estate business. The rest is fairly well-known history, including Trump's housing discrimination. But what about Elizabeth? Her history is almost non-existent. She has no Wikipedia page. She isn't even mentioned on her mother's Wikipedia page, despite the fact that Fred Jr. is noted as the "second child" and John the "third." She is mentioned on the Trump family page. We know she married William Walter, who was training to work in a bank, in June of 1929. According to William's 1959 obituary, he was a veteran of World War I who had worked in banks starting as a page boy in 1910. The year he and Elizabeth were married, he was made assistant secretary of the newly formed Manufacturer's Trust. Elizabeth apparently continued in her accounting role after marrying William, but it is unclear whether she left in late 1929 when E. Trump and Son went under, and whether she continued to work under Fred Jr. Elizabeth and William Walter had two children - William Trump Walter, born in 1931, and John Whitney Walter, born in 1934. Both Elizabeth and William Sr. were highly involved in the Hollis Presbyterian Church. He was an elder, she, a member of the Women's League. So it makes sense that Elizabeth would submit recipes for the 1946 cookbook. Here are her recipes: The "Party Suggestions" that start on page 125 is a small section that only contains recipes from Elizabeth Trump Walter! All variations on starter salads (with one exception), probably for ladies' luncheons, but possibly also for themed dinner parties, or even children's parties. South Sea Island Place slice of pineapple in center of a bed of shredded lettuce. Fill hole with cream cheese and put a spring of parsley in cheese to represent palm tree. Cut banana in half lengthwise and then in half crosswise – straight bananas are best – and place these on lettuce sea around pineapple island, cut side up. Cut saltines diagonally in half. Each half makes a sail. Insert tooth pick in corner and stick in banan boat. Cut strips of wax paper about ¾ inch by 1 ½ inches. Fringe and tie around chocolate candy dolls for grass skirt and place under palm tree. Mexican Hayride Force a Ritz cracker on either side of a toothpick for wheels and axle. Make two sets for each service. Fill lettuce cups with crab meat salad and place on top of two sets of wheels and axles. Force animal crackers on either side of a toothpick. This kames a pair of horses. As many pairs of horses as desired may be used. Place thin strips of green pepper from lettuce cups to team of horses for reins. Snow Man Ice cream cone Whipped cream Scoop of vanilla ice cream 3 inch round of sponge cake Cover sponge cake with whipped cream. – Place scoop of ice cream in center of sponge round. Invert cone on ice cream. Make eyes of melted chocolate and use slice of cherry for mouth. Force whipping cream through tube to make ruffling for collar around face. Sail Boats Peel cucumber and cut in half, lengthwise. Scoop out center and mix with salmon salad. Fill mixture in cucumber boat – Place on bed of shredded lettuce for waves. To make sail, cut drinking straw in half. Cut rectangle from stiff white paper and attach to half of straw with scotch tape. Place sail in center of boat. Easter Eggs in Nests Place slice of pineapple on small bed of shredded lettuce. Divide cream cheese into five parts. Color each part a different pastel shade, leaving one white. Form cream cheese into small eggs, the size of a robins egg and place in center of pineapple slice. Circus Salad Cut a five inch circle from a piece of stiff paper with pinking shears. Cut a slit to center from one side and then put together to form a dome shaped piece for top of tent. Place tuna fish salad in center of plate. Around salad sprinkle Cornflakes or Rice Krispies to represent sawdust. Insert five pretzel sticks around salad and place tent on top of these sticks. Her six party suggestions make up the entire "Party Suggestions" chapter. I, personally, would have a hard time cutting saltines in half or forcing toothpicks into crackers, so clearly this sort of thing took a great deal of finesse. Elizabeth Trump Walter died on December 4, 1961, at the age of 57, "after a long illness," just two years after her husband William. Her obituary is on page 37 of that day's New York Times, towards the bottom. She pre-deceased her mother Elizabeth Christ Trump by five years. Ironically, Elizabeth Christ Trump does not have an obituary in the New York Times, she is only listed among the deaths recorded on June 9, 1966 - her notice submitted by the Federation of Jewish Philanthropics. According to Elizabeth's son John Walter's 2018 obituary, the Walters moved to Manhasset, NY toward the end of their lives. They lived in a retirement home built by the Walters and likely Fred Trump, Jr., but died just a few years later. John begun attending the Congregational Church of Manhasset at his mother's behest. Elizabeth Trump Walter was memorialized with a restored organ at the Congregational Church of Manhassett, NY sometime in recent years. Elizabeth Trump Walter rarely shows up in Trump family histories, probably because of her early death compared with the Trump family fortunes. But it was a fascinating project to track down what I could about her. The Hollis Pantry Cook Book has more secrets and famous recipe authors to share, so stay tuned for future blog posts. Have you ever found a famous person's name in a community cookbook? Tell us in the comments! The Food Historian blog is supported by patrons on Patreon! Join us for awesome members-only content like free digitized cookbooks from my personal collection, e-newsletter, and even snail mail from time to time! This article contains Amazon.com and Bookshop.org affiliate links. If you purchase anything from these links, The Food Historian will receive a small commission. All Stirred Up: Suffrage Cookbooks, Food, and the Battle for Women’s Right to Vote, Laura Kumin. New York: Pegasus Books, 2020. 357 pp., $28.95, hardcover, ISBN 978-1-64313-452-9. ,I first learned about cookbooks associated with women’s suffrage thanks to this Atlas Obscura article and I was instantly fascinated. Feminism in the 20th century was often more interested in throwing off the chains of household drudgery than with enticing converts through snacks. But that is precisely the premise of All Stirred Up: Suffrage Cookbooks, Food, and the Battle for Women's Right to Vote, which is why I was so excited that I put it on my Christmas wish list. I was expecting a thorough examination of the suffrage cookbooks, the women who created them, and their place in the movement. Sadly, as a book, All Stirred Up is like an underdone cake – it looks perfect on the outside, but the inside is doughy and disappointing and could have used another 30 minutes in the oven. Laura Kumin is a former lawyer turned cooking educator and food writer. She does not have a historical background, and, as is the case with many non-historians who write food history, it shows. All Stirred Up begins, even before the introduction, with a lengthy timeline. While I find timelines to be incredibly useful, especially when dealing with complex chronology, starting the book with one was not a choice I would have made. It is confusing to the reader, who is presented lengthy and disparate facts without context or introduction. A lack of context is a theme for the book. Kumin’s introduction is part explanation of her interest in suffrage cookbooks and part layout of her main argument. She makes a compelling case that modern takes on suffrage history have largely ignored the role of cookbooks in converting skeptics to the cause. Unfortunately, this argument is not often revisited in the subsequent chapters. Most of the chapters are quite brief, some as few as eight pages, and while historical overviews abound, actual analysis is lacking. Taking up the most space are the recipe sections that follow each chapter, organized by type. Although these recipes are directly taken from the suffrage cookbooks, with modern adaptations designed by Kumin, there is no context for any of the recipes and no dates listed. Most recipe sections draw from multiple suffrage cookbooks without differentiating between them, beyond noting where the originals came from. We do not know why Kumin chose these particular recipes, how they reflected the cookbooks and times from whence they came, or even what, if any, relevance they had to the suffrage movement. For many chapters, the number of pages devoted to recipes outweigh the pages devoted to history. As for the history itself, most of it is shallow summaries meant to orient the reader to the basics of suffrage history, home economics and food science, and basic culture of the period. While this context is useful for non-historians, it seems to come at the expense of historical analysis. In addition, the chronology of the book is all over the place. The book begins in 1848, with an exercise in “time travel” in which Kumin writes in the present tense. Then zooms ahead to the Progressive Era and back again several times. At the end of Chapter 3, we’re already at the 19th Amendment in 1920, an achievement which is not really revisited for the rest of the book. Throughout the book, the suffrage movement in one decade is conflated with the same movement decades later. Little attention is paid to the context of national culture on the way in which the women's suffrage movement was operated, despite the fact that it was under operation, in one way or another, for over 70 years. Missed opportunities to make connections to other major movements, including abolitionism, Temperance (which is dismissed as detrimental to the cause, p. 78-79), Progressive reform, government regulation, etc., abound. Chapters 3, 4, and 6 are the strongest, content- and argument-wise. In Chapter 3, “From Seneca Falls to the Ballot Box,” Kumin examines the suffragists themselves and the post-Civil War resurgence of the movement. To her credit, she makes a point of mentioning African American suffragists and their shameful treatment by mainstream white suffragists, as well as male allies and the “antis” – anti-suffragists. However, points that needed more analysis were often presented as literal sidebars in the text. For instance, noted suffrage ally Frederick Douglass, instead of being included in the main text, receives a short summary in a gray box. The Beecher family get similar treatment in a sidebar about how the movement split families. Catharine Beecher, a fervent anti-suffragist, was a cookbook author and young women’s educator of some renown and who, despite conflicting ideas about suffrage, nonetheless co-wrote The American Woman’s Home with her suffragist sister. Cookbook author, fervent abolitionist, and Native American rights activist Lydia Maria Child is mentioned in a quotation, but otherwise ignored. These are just a few of many missed opportunities to engage with the subject matter more deeply – discussing how both suffragists and “antis” used women’s work and the home in their arguments for and against suffrage. Chapter 4, “We Can Peel Potatoes and Fight for the Vote, Too! Suffrage Strategies and Battle Tactics” is the strongest chapter in the book, and one of the few that cites primary sources in the endnotes. Discussing the divergent tactics between “mainstream” and “militant” suffragists, Kumin compares the mainstream work of the cookbooks, cafeterias, the “doughnut campaign,” a “Pure Food” storefront, and cooperating with agricultural extension, to the militant tactics of parades, protests, arrests, and hunger strikes. Unfortunately, she does not define who exactly is “mainstream” and who is “militant,” except to note differing tactics. Kumin argues that the more mainstream feminists were more successful in changing hearts and minds, but presents little evidence to back up this claim. In addition, despite covering the bulk of the Progressive Era, the chapter mentions, but gives little context to agricultural extension, the Temperance movement, home economics, World War I, and women’s clubs. An overview of home economics and food science comes in the following chapter, “Revolution in the Kitchen.” Chapter 6 finally addresses the cookbooks themselves, with an overview of how they were financed, celebrity contributors, and how the recipes included were reflective of the periods in which they were published. The cookbooks are still dealt with in generalizations, however, and their individuality is lost in the mix. The section on celebrities, although interesting contains another missed opportunity, as Kumin mentions one recipe contribution from noted feminist Charlotte Perkins Gilman, but not her dislike of cooking. In the section on funding, Kumin clearly notes that the cookbooks were usually designed as fundraisers for the organizations, a fact that belies her argument that cookbooks were meant to convert, though she does note they were sometimes also used as enticing premiums for subscriptions. Chapter 7 is a brief discussion of how suffragists used dinners and entertaining to support the cause. All Stirred Up ends without a clear conclusion, instead relying on Chapter 8, “What Suffrage Means for Us,” an eight-page summary of women in American politics since 1920. This final chapter makes no clear reference to the influence of the cookbooks that purportedly drove the suffrage movement and does not sum up the arguments outlined in the introduction. It is followed by 28 pages of dessert recipes. There is no explanatory postscript, only Kumin’s acknowledgements. In all, All Stirred Up does make a good point about the role of suffrage cookbooks in the movement, but it fails to back up its few arguments convincingly, particularly in light of the use of community cookbooks as fundraising tools, rather than modes of conversion to the cause. Instead of concentrating the bulk of her argument into Chapter 4, Kumin would have had a much more compelling book had she spread that argument throughout all the chapters, addressing the role of domesticity from the perspectives of both the suffragists and the antis. More primary source analysis would have enriched the narrative. Looking at the writing of major suffrage leaders to determine their personal opinions on cooking and domesticity would have added depth to her arguments. Examining the cookbooks themselves, their recipes, and the organizations and women that produced them as a chronological accounting of the movement, would have added greatly to the coherence and context of the book. Had the recipe sections been introduced by era, with headnotes and historical context for each recipe, their inclusion would have made the book both stronger and appealing to the general public. Ultimately, the book feels as though it was rushed to print, possibly to coincide with the centennial anniversary of the 19th Amendment in 2020. If you are unfamiliar with basic suffrage and food history, this may provide some good historical summaries and Kumin’s research on the 1909 Washington Women’s Cook Book is particularly strong. But, if you were hoping for a well-written, well-organized examination of the role of food in the suffrage movement and the influence of suffrage cookbooks, as I was, you’ll be sorely disappointed. I can only hope that future historians can expand on Kumin’s work. If you'd like more food history book reviews, check out the Book Review category of this blog. The Food Historian blog is supported by patrons on Patreon! Join us for awesome members-only content like free digitized cookbooks from my personal collection, e-newsletter, and even snail mail from time to time! Last week I did the first of a series of several talks with cooking demonstrations for the Poughkeepsie Library. The first was all about pumpkin pie and I made Lydia Maria Child's original pumpkin pie recipe from her 1832 cookbook The American Frugal Housewife, and then followed it with a discussion of the history of pumpkin, pumpkin pie, and pumpkin pie spice. The library recorded the talk, so you can check it out below! Lydia Maria ChildLydia Maria Child was born in Medford, Massachusetts in 1802. When she moved to Maine as a young woman to study to be a teacher, her older brother Convers, who had attended Harvard Seminary, assisted with her literary education. Upon reading and article about the rich resources New England history could provide novelists, she launched an unplanned writing career with her first novel, Hobomok, published in 1824. The book was set in 17th century New England and concerned the lives of a Native man, Hobomok, and the White woman he married and had a child with. Initially rejected by critics for its theme of miscegenation, it was later lauded by Boston literary circles. While teaching, Lydia Maria turned her attention to writing again, founding Juvenile Miscellany in 1826 - the first American monthly periodical designed specifically for children. Under Child's editorship, it became a popular and groundbreaking publication, emphasizing Protestant morality without the boring proselytizing common in children's literature at the time. In 1828 she married David Lee Child, a Boston lawyer and journalist (her maiden name was Francis) and stopped teaching, but not writing. In 1829 she published The Frugal Housewife: Dedicated to those who are not ashamed of economy, a cookbook directed at assisting the lower classes. It was published in several editions until 1832, when she changed the name to The American Frugal Housewife, to differentiate it from another cookbook of the same title published in Britain. Child published several other books on motherhood and household management, but her abolition work and radical politics largely derailed her literary career. She and her husband David Child began to identify as abolitionists in 1831. In 1833, she published An Appeal in Favor of that Class of Americans Called Africans, which called, among other things, for total abolition of slavery without compensation to enslavers. It was the first anti-slavery book (not pamphlet) published in the United States. Throughout the 1830s and '40s she became very active in the abolition and anti-slavery movements, publishing anti-slavery fiction, anti-slavery political tracts, and organizing fundraisers and events. Her anti-slavery stance and other radical politics enraged many readers in the American South, and subscriptions to Juvenile Miscellany declined so much that in 1834 she stepped down as editor. Sarah Josepha Hale edited the magazine until its closure in 1836. Child went on to publish tracts supporting Native American rights as well, including An Appeal for the Indians in 1868. Lydia Maria Child died in 1880 at the age of 78. Because of her political beliefs, she did not see the financial success of many of her author peers. But The American Frugal Housewife remains one of her most enduring legacies, along with her most famous poem, "A New England Boy's Song About Thanksgiving Day," which she published as part of her book Flowers for Children, Vol. 2 in 1844. You might know it better as "Over the River and Through the Woods." "A New England Boy's Song About Thanksgiving"Over the river, and through the wood, To grandfather's house we go; The horse knows the way, To carry the sleigh, Through the white and drifted snow. Over the river, and through the wood, To grandfather's house away! We would not stop For doll or top, For 't is Thanksgiving day. Over the river, and through the wood, Oh, how the wind does blow! It stings the toes, And bites the nose, As over the ground we go. Over the river, and through the wood, With a clear blue winter sky, The dogs do bark, And children hark, As we go jingling by. Over the river, and through the wood, To have a first-rate play -- Hear the bells ring Ting a ling ding, Hurra for Thanksgiving day! Over the river, and through the wood -- No matter for winds that blow; Or if we get The sleigh upset, Into a bank of snow. Over the river, and through the wood, To see little John and Ann; We will kiss them all, And play snow-ball, And stay as long as we can. Over the river, and through the wood, Trot fast, my dapple grey! Spring over the ground, Like a hunting hound, For 't is Thanksgiving day! Over the river, and through the wood, And straight through the barn-yard gate; We seem to go Extremely slow, It is so hard to wait. Over the river, and through the wood, Old Jowler hears our bells; He shakes his pow, With a loud bow wow, And thus the news he tells. Over the river, and through the wood -- When grandmother sees us come, She will say, Oh dear, The children are here, Bring a pie for every one. Over the river, and through the wood -- Now grandmother's cap I spy! Hurra for the fun! Is the pudding done? Hurra for the pumpkin pie! "Pumpkin And Squash Pie" (the filling)Here is Lydia Maria Child's original text: "For common family pumpkin pies, three eggs do very well to a quart of milk. Stew your pumpkin, and strain it through a sieve, or colander. Take out the seeds, and pare the pumpkin, or squash, before you stew it; but do not scrape the inside; the part nearest the seed is the sweetest part of the squash. Stir in the stewed pumpkin, till it is as thick as you can stir it round rapidly and easily. If you want to make your pie richer, make it thinner, and add another egg. One egg to a quart of milk makes very decent pies. Sweeten it to your taste, with molasses or sugar; some pumpkins require more sweetening than others. Two tea-spoonfuls of salt; two great spoonfuls of sifted cinnamon; one great spoonful of ginger. Ginger will answer very well alone for spice, if you use enough of it. The outside of a lemon grated is nice. The more eggs, the better the pie; some put an egg to a gill of milk. They should bake from forty to fifty minutes, and even ten minutes longer, if very deep." And here's my translation: 1 sugar pie pumpkin 2 cups whole milk 4 eggs 2 tablespoons cinnamon 1 tablespoon ground ginger 1/2 teaspoon salt 1/4-1/2 cup maple syrup Cut pumpkin in half, scoop out seeds, and roast, cut-side down, for 45 minutes at 350 F. When soft and easily pierced with a knife, remove from oven and scoop out flesh from rind. Mash thoroughly with a fork to remove stringiness. Let cool, then add spices and salt and mix thoroughly, then add all liquid ingredients. Pour into chilled pie shells (recipe below) and bake at 450 F for 15 minutes, then reduce heat to 350 F and bake for an additional 30 minutes. When the center is solid (a slight wobble is allowed), the pie is set and baked. Serve warm or cold with additional maple syrup (if desired) and whipped cream (recipe below). If you have extra filling, add to ungreased glass baking dishes or custard cups for equally good "crustless pumpkin pie." "Pie Crust"The original: "To make pie crust for common use, a quarter of a pound of butter is enough for half a pound of flour. Take out about a quarter part of the flour you intend to use, and lay it aside. Into the remainder of the flour rub butter thoroughly with your hands, until it is so short that a handful of it, clasped tight, will remain in a ball, without any tendency to fall to pieces. Then wet it with cold water, roll it out on a board, rob over the surface with flour, stick little lumps of butter all over it, sprinkle some flour over the butter, and roll the dough all up; flour the paste, and flour the rolling-pin; roll it lightly and quickly; flour it again; stick in bits of butter; do it up; flour the rolling-pin, and roll it quickly and lightly; and so on, till you have used up your butter. Always roll from you. Pie crust should be made as cold as possible, and set it in a cool place; but be careful that it does not freeze. Do not use more flour than you can help in sprinkling and rolling. The paste should not be rolled out more than three times; if rolled too much, it will not be flaky." Well that was a bit of a doozy of a recipe! Essentially, she's making an all-butter pie crust by combining shortbread and puff pastry techniques. And it turns out pretty well! If you're looking for a good all-butter pie crust recipe, this is a fairly reliable one, if you handle it gently. Here's my translation: 1 stick (1/4 pound) very cold unsalted butter 1 1/4 cup all-purpose flour 1/4-1/2 cup reserved flour for rolling ice water With cold hands, cut the stick of butter lengthwise in thirds, then rotate one quart of the way and cut in thirds again. Then cut crosswise until you have nice little cubes. Use at least half of the butter to rub into the 1 1/4 cup flour in a large bowl. Add more butter if you need to. From a bowl of ice water, using a tablespoon, add the water, 1-2 tablespoons at a time, and toss mixture with a fork. You'll need 6-8 tablespoons, depending on your flour and butter ratios. When you can make a ball with your hands and it sticks together nicely, but not too wet, you're good. Form the mass into a ball and roll out on a well floured surface, taking care to roll gently so as not to break the dough or roll unevenly. Once you have rolled out a round, spread whole cubes of butter across half the circle, fold in half, and roll that flat. Then repeat 2 more times (making sure to reserve enough butter for each rolling). When complete, roll out for crust. You'll have at least one single crust, with some left over for smaller pies. Place in pans, trim and crimp edges, and chill until ready to fill. Bake with pumpkin filling as directed above, or add your favorite fruit filling. My crust turned out delightfully crisp, but a little flat in flavor. A pinch of sugar and/or salt would probably be a nice addition. Hand Whipped CreamThis one isn't in The American Frugal Housewife, but it goes deliciously with pumpkin pie! The higher quality/fat content your cream, the easier it is to whip by hand. 1/2 cup heavy cream 1 tablespoon sugar or maple syrup 1 teaspoon homemade vanilla (recipe below) In a very deep bowl (preferably glass, which stays nice and cold), add the chilled cream, sugar, and vanilla. Tilt bowl and beat cream with a wire balloon whisk in a circular motion until you add enough air to the cream that it holds its shape. Do not overbeat, or you'll end up with sweet vanilla butter. Chill until ready to serve. Homemade VanillaHomemade vanilla lasts nearly forever, so it's a worthy investment, but vanilla beans are quite expensive these days, so make at your own expense. Still probably cheaper than buying the tiny bottles of the real stuff. You can make it with vodka, but I find the gold rum is much nicer and mellower. Also makes a great Christmas present. A dozen or so whole vanilla beans Gold rum (get the not-quite-the-cheapest brand) Cut the vanilla beans in half and add them to a quart jar. Fill jar with gold rum. Let sit in a dark place for a week or so before using. Keep adding rum as you deplete the vanilla. You want to keep the beans submerged at all times. Add beans every few years to keep the flavor up. Happy Thanksgiving!And that, my dears, is that. If you made it this far through the blog post, congratulations! I hope you enjoyed the video, some history about Lydia Maria Child, her famous poem, and the recipes. Keep your eyes peeled for more cooking-demonstration-and-talk programs coming up in December, January, and February. I hope you have a wonderful Thanksgiving! As always, The Food Historian blog is supported by patrons on Patreon! Join us for awesome members-only content like free digitized cookbooks from my personal collection, e-newsletter, and even snail mail from time to time! Today was a chilly VERY blustery day - my styrofoam Halloween headstone actually blew away this morning! Luckily it only blew into the side yard and wasn't too damaged. Long story short, it seemed like the perfect weather for chicken and dumpling soup. Only problem? I'd yet to find a good dumpling recipe. Until I consulted the glorious Ida Bailey Allen and her 1942 Money-Saving Cook Book. Ida Bailey Allen is one of my favorite relatively unknown celebrity cookbook authors. She was PROLIFIC and published over 50 cookbooks in her lifetime, from 1917 to the 1973 Best Loved Recipes of the American People, published the same year she died. A food writer, magazine editor, and essentially the founder of homemaker radio (she was the president of the Radio Homemakers Association), she was also the first female food TV host with her show "Mrs. Allen and the Chef" (you can listen to clip here!). One of the only moving images of Mrs. Allen that seems to survive on the internet is this little clip from the 1940s - a retrospective of the 1920s. Candy in tea! Who knew? Her Money-Saving Cook Book, first published in 1940 was republished in 1942 as a Victory edition, which is the version I have. It's just a delightful cookbook - chock full of basic, easy, and inexpensive recipes, as well as a bunch of 1940s-style vegetable recipes that I can't wait to try out. So when I was on the hunt for a dumpling recipe to go with my chicken soup, this one of the first cookbooks I consulted, and it did not disappoint. First, let's start with the chicken soup. Scratch Chicken Soup1 pound chicken 5 quarts water (or 4 quarts water and 1 quart chicken stock) 1 onion 2-3 ribs celery 1 cup diced carrots 1 cup frozen peas 1 cup frozen corn (or 1 bag mixed frozen corn, peas, and carrots) salt & pepper to taste Soup is always way easier than people think. It's just a matter of adding ingredients at the right time depending on how long they have to cook. Start with the chicken. You can use boneless or bone-in, skin-on. If using boneless, substitute 1 quart of water with chicken stock for extra flavor. In a large stock pot (I used my favorite cast iron dutch oven), add the chicken, water (and/or stock), onion, celery, and carrots (if using fresh). If not using chicken broth (which is salted), add a teaspoon of salt. Bring to a boil and reduce heat to a simmer, cooking until the chicken is cooked-through and the carrots are tender. About 20 minutes. Remove the chicken from the broth, dice, and return to the pot. Add the frozen vegetables and return to a simmer. Once the vegetables are tender, voila - chicken soup. You can now proceed to the dumpling recipe. Ida Bailey Allen's Puffy Drop DumplingsI didn't want to roll out the dumplings, so I used the Drop Dumpling version of the recipe. Here's the original, which turned out pretty well! I did substitute butter for the shortening. If you use salted butter, reduce the salt in the recipe to 1/2 or 3/4 teaspoon. 2 cups all-purpose flour 1 teaspoon salt 1 teaspoons baking powder 1 tablespoon unsalted butter 1 cup whole milk Use a balloon whisk to blend the flour, salt, and baking powder together. Cut the butter into small pieces and squish in the flour with your fingers (or cut in with a pastry blender) - there should be small chunks or streaks of butter left in the floury mixture. Then add 1 cup milk. Mrs. Allen called for a scant cup, but that wasn't quite enough - my mix was dry instead of being soft. Using a regular table or soup spoon, drop bits of dough about the size of a walnut (or a little larger) into the simmering soup. There will be a lot - submerge any exposed parts under the broth to make sure they steam properly. They'll start puffing up/breaking up almost immediately. Cover the pot and simmer for about 5 minutes. The flour from the dumplings will thicken the broth nicely. The dumplings exceeded my expectations - being a cross between that doughy chew you expect from a nice soup dumpling and light and spongy on the inside of the larger ones. All in all - a perfect one pot supper on a blustery, chilly day. The Food Historian blog is supported by patrons on Patreon! Join us for awesome members-only content like free digitized cookbooks from my personal collection, e-newsletter, and even snail mail from time to time!

|

AuthorSarah Wassberg Johnson has an MA in Public History from the University at Albany and studies early 20th century food history. Archives

July 2024

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed