|

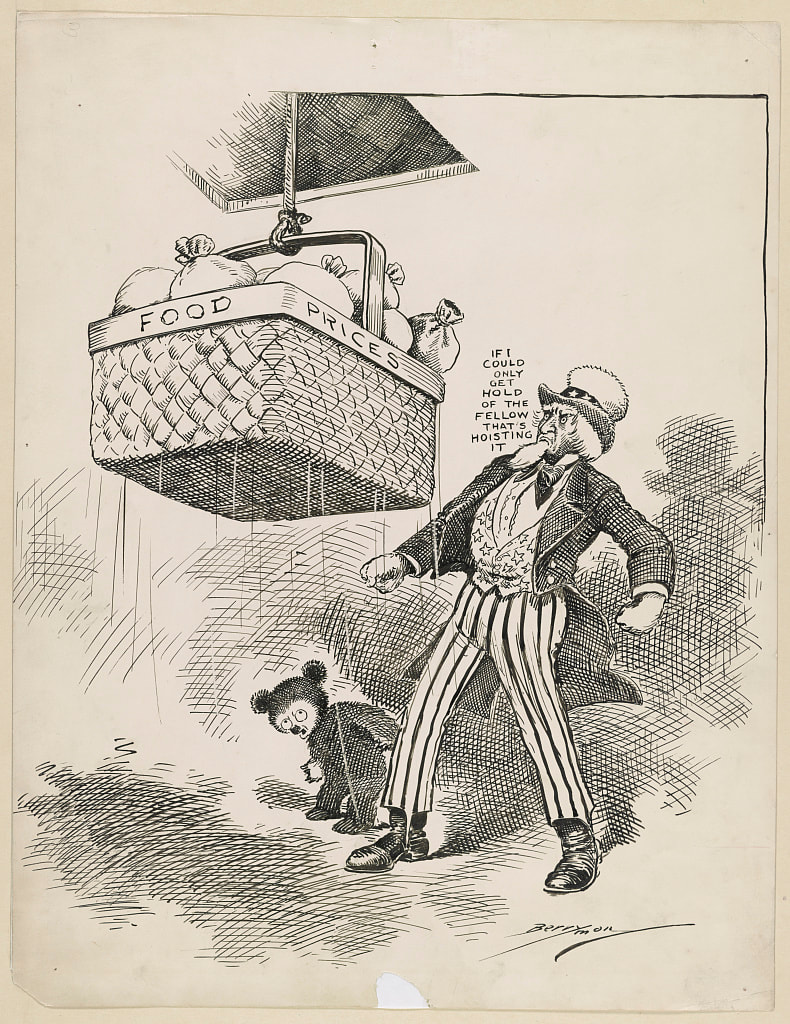

Even though the United States didn't officially join the war until April 7, 1917, the U.S. had long supported the Allies and neutral nations through the sale of agricultural products. But the 1910s was a time of little government regulation and increasingly global commerce. The Allied European nations all leaned heavily on their colonial holdings to produce food and war materiel, what goods they could get through German U-boat blockades. Part of the reason for German expansionism in Europe was a lack of colonial holdings (also the reason for the Second World War, as ably argued by Lizzie Collingham in The Taste of War), and therefore a lack of agricultural capacity. As an independent nation rich in natural resources (through their own brutal colonization of the continent), the United States was able to meet the increasing European demand. Midwestern wheat farmers in particular were very happy, as the increased demand increased prices. But while farmers were happy to have good return on their crops, the increased demand from abroad was increasing food prices at home. The High Cost of Living or "H.C.L." as it was often referred to in the press, was the topic of much discussion throughout the Progressive Era. Kosher meat riots in 1902 and again in 1910 in New York City were only the beginning. Exacerbated by the war, by 1917 rising food prices led women around the world to riot against food prices that increased sometimes 200% in a matter of weeks. You can read more about the food riots of New York City in a previous blog post. In this image (hard to tell if it was used as a political cartoon or a poster), Uncle Sam looks at a picnic basket labeled "Food Prices" being hauled up through the ceiling. He mutters to himself, "If only I could get hold of the fellow that's hoisting it." His fists are at his side, impotently, while a small teddy bear (whose significance is unclear, but may have been a reference to Teddy Roosevelt --- see the update below!) looks on in dismay. The image reinforced the idea that the federal government had little or no control over food prices. Ultimately, the food price question was never really settled. Boycotts temporarily created surpluses, which lowered prices. But only the increased wartime production when the U.S. entered the war in 1917 seemed to raise wages and increase agricultural supply enough to address rising food prices. And when the war ended in late 1918, food prices increased again as regulating government agencies like the United States Food Administration were dismantled, but relief efforts abroad continued, along with the supply of the American Expeditionary Forces, many of whom did not return until the end of 1919 or even later. Increased production encouraged during the war years resulted in an agricultural depression in the 1920s, as European nations recovered their own agricultural production and demand for American exports fell. The agricultural depression was an early harbinger of the Great Depression. Stay tuned next week for propaganda about the High Cost of Living during the Second World War. UPDATE: Many thanks to Food Historian reader Peter K. for giving us some more context about the teddy bear! Apparently artist Clifford Berryman was the originator of the Teddy Bear, which was indeed inspired by Theodore Roosevelt. Adding the teddy bear to various political cartoons was one of Berryman's signatures, although the bear was often the star of the show. Once Teddy Roosevelt left office, Berryman also used the bear to represent his own opinions in political cartoons. The Food Historian blog is supported by patrons on Patreon! Patrons help keep blog posts like this one free and available to the public. Join us for awesome members-only content like free digitized cookbooks from my personal collection, e-newsletter, and even snail mail from time to time!

0 Comments

Thanks to everyone who joined me on Friday for Food History Happy Hour live on Facebook. This week we discussed the role of riots and boycotts in history and food history, touching primarily on the food boycotts and riots and high cost of living protests of 1916/1917 which occurred around the globe. We also talked about women's suffrage and farmerettes, midnight suppers, Frank Meier, inventor of the bees' knees cocktail and his role in WWII, poison candy and the Pure Food and Drug Act of 1906, food and riots or protests, including the role of food and cooking in the Civil Rights movement, Laura Ingalls Wilder and the Little House Cookbook, L. M. Montgomery, requests for next week, and a brief introduction to the history of gelatin, beaten biscuits, and other formerly upper-crust foods which became inexpensive convenience foods. If you want to watch back episodes you can check them out on right here on the blog or I am hoping to upload full episodes to YouTube now that my channel is officially verified! Bees' Knees Cocktail (1936)In 1936 Frank Meier published "The Artistry of Mixing Drinks," a beautifully designed little bartender's guide based on his time as the head bartender at the Hotel Ritz Carlton's Cafe Parisian, which opened in 1921. Frank had purportedly trained at the Hoffman House in New York City before taking on his new role at the Ritz. He served as head bartender and host for over twenty years and even played a role in the French Resistance during WWII, when the Ritz became German headquarters. Meier was a well-known originator of cocktails, including the famous "Bees' Knees," which he invented sometime in the 1920s. It became popular in the United States during Prohibition, likely because the honey and lemon masked the taste of bathtub gin. Frank's original recipe reads: "In shaker: the juice of one-quarter Lemon, a teaspoon of Honey, one-half glass of Gin, shake well and serve." A more modern recipe might be: Juice of 1/4 lemon (or half a tablespoon) 1 or 2 teaspoons of honey 1 or 1 1/2 ounce gin Shake over ice and serve in a cocktail glass. One teaspoon of honey definitely wasn't enough for me - I couldn't taste the honey at all! Perhaps "a dollop" might be a better descriptor. Here are some resources on some of the topics we discussed tonight:

Next week we'll be discussing Easy Bake Ovens, Jello and aspic, foods of the 1950s and '60s, and all sorts of other fun stuff. See you then! If you liked this post and would like to support more Food History Happy Hour livestreams, please consider becoming a member or joining us on Patreon. Members and patrons get special perks like access to members-only content.

|

AuthorSarah Wassberg Johnson has an MA in Public History from the University at Albany and studies early 20th century food history. Archives

July 2024

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed