|

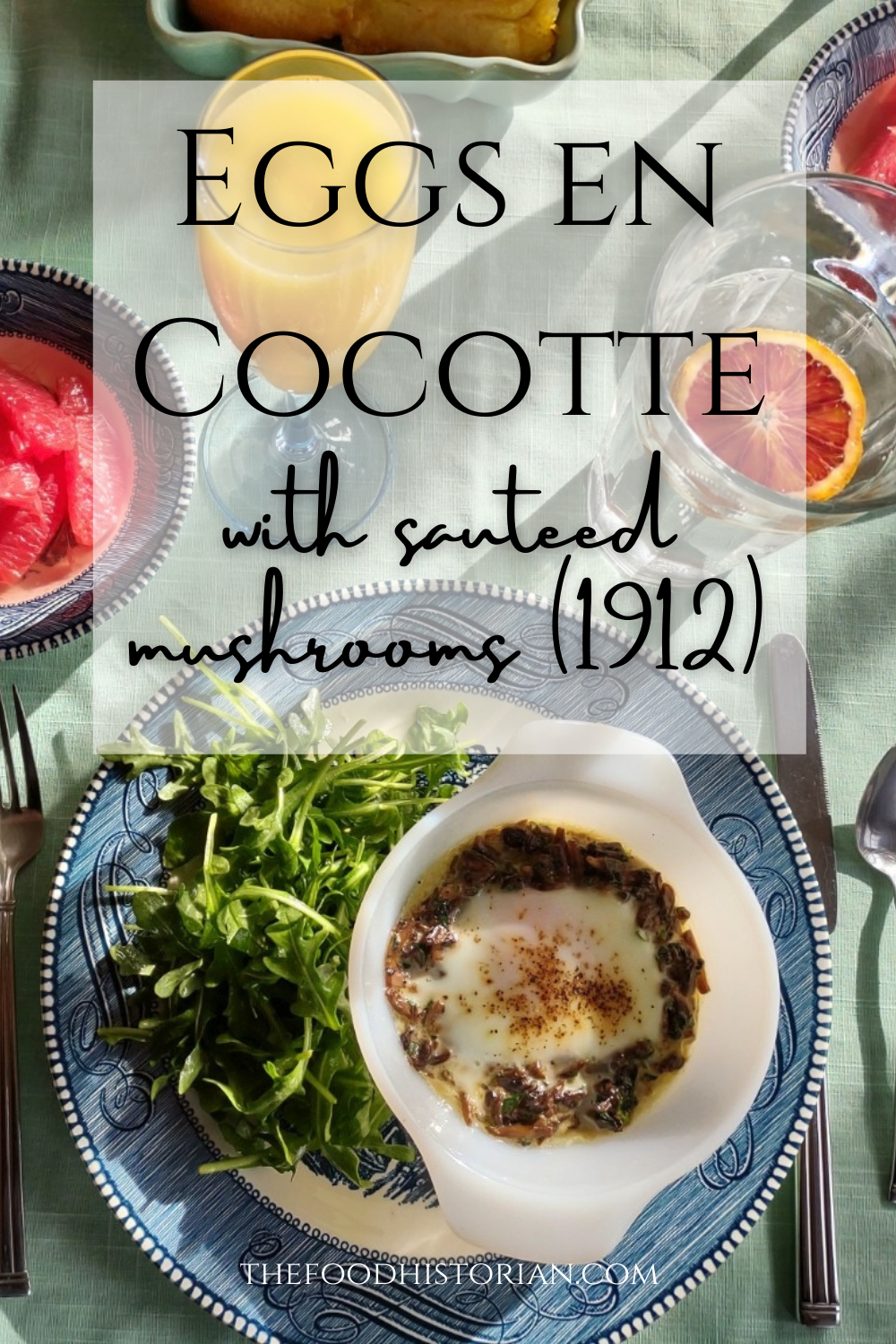

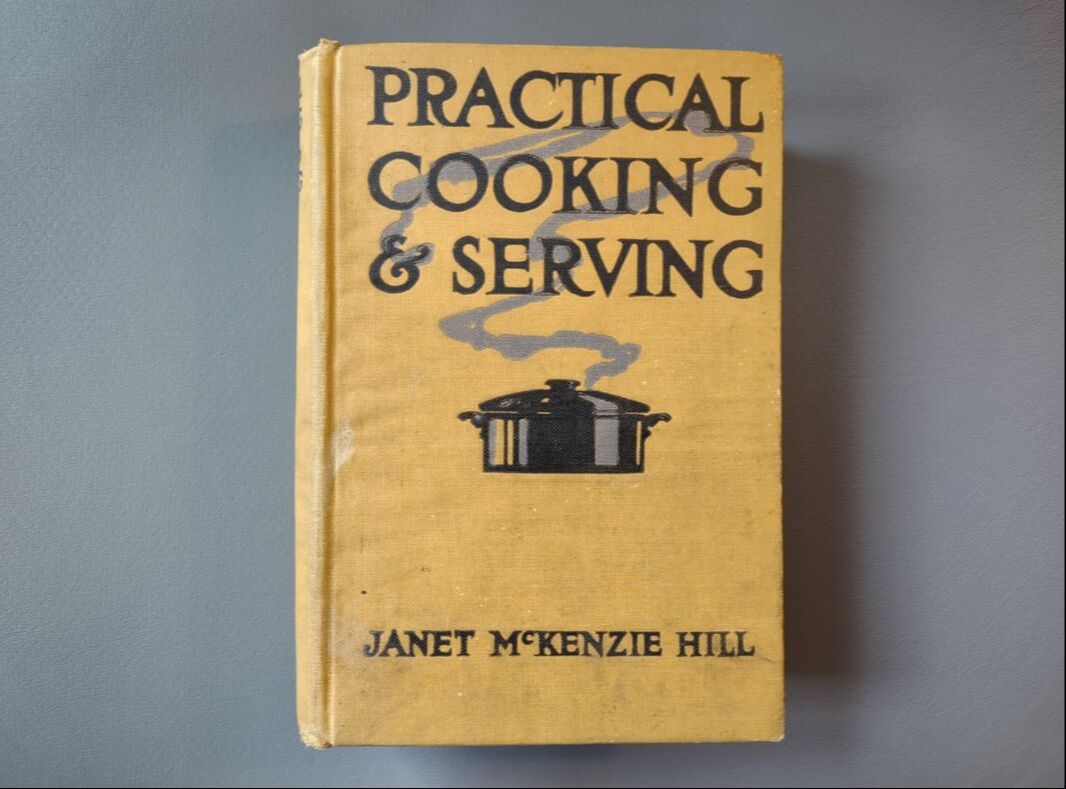

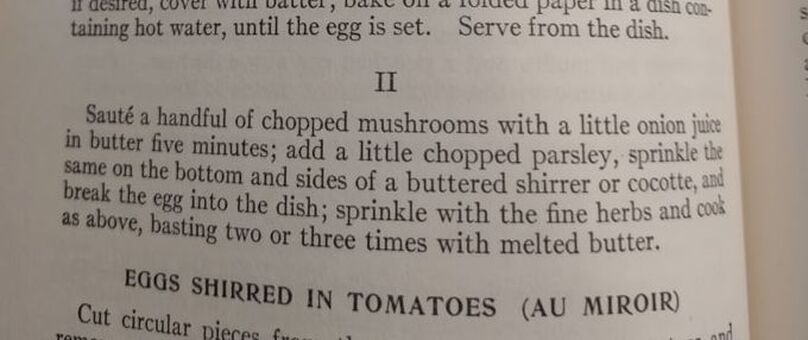

I love brunch. Not the kind you wait in line for, crowded and busy and loud. I love brunch made at home. It's as quiet or loud as you want it to be, the service is usually pretty good, and while there's the effort of making food, if you play your cards right, it's always hot when it gets to the table, and hopefully someone else will do the washing up. Eggs have long been a breakfast staple. If you've a hot skillet, they cook up in a flash. And if you keep chickens, you have a fresh supply every day, at least during the warmer months. But getting a bunch of eggs hot and cooked to order to the table can be a precarious thing when you're hosting. So I took to my historic cookbooks and found a viable solution - eggs en cocotte. Technically, it's oeufs en cocotte, which is French for eggs baked in a type of dish called a cocotte, which may or may not have been round, or with a round bottom and/or with legs. Sometimes also called shirred eggs, which are usually just baked with cream until just set, these days en cocotte generally means the dish spends some time in a bain marie - a water bath. The cookbook recipe I used was from Practical Cooking & Serving by prolific cookbook author Janet McKenzie Hill. Originally published in 1902, my edition is from 1912. You can find the 1919 edition online for free here. A weighty tome of a book, Practical Cooking and Serving is nothing if not practical, and McKenzie Hill is uncommonly good at explaining things. Her section on eggs explains: "Eggs poached in a dish are said to be shirred; when the eggs are basted with melted butter during the cooking, to give them a glossy, shiny appearance, the dish is called au mirroir. Often the eggs are served in the dish in which they are cooked; at other times, especially where several are cooked in the same dish, they are cut with a round paste-cutter and served on croutons, or on a garnish. Eggs are shirred in flat dishes, in cases of china, or paper, or in cocottes. A cocotte is a small earthen saucepan with a handle, standing on three feet." Since my baking dishes were neither the flat oval shirring dishes, nor the handled kind, I guess perhaps they are neither shirred nor en cocotte, according to Hill, but we can afford to be less picky about our dishware. Hill offered two recipes: one more classic version with breadcrumbs (optional addition of chopped chicken or ham) mixed with cream "to make a batter." The buttered cocotte was lined with the creamy breadcrumbs, the egg cracked on top, with the option to cover with more breadcrumb batter. The whole thing was then baked in a hot water bath "until the egg is set." My brunch guest adores mushrooms, and I wanted something a little fancier and more substantial, so I went with Hill's version No. II. Eggs en Cocotte with Sauteed Mushrooms (1912)Hill's original recipe reads: Sauté a handful of chopped mushrooms with a little onion juice in butter five minutes; add a little chopped parsley, sprinkle the same on the bottom and sides of a buttered shirrer or cocotte, and break the egg into the dish. Sprinkle with the fine herbs and cook as above, basting two or three times with melted butter. I will admit I didn't follow the directions as closely as I should have - I didn't use hot water in my bain marie (oops), and I didn't baste with butter. So the eggs were cooked a little more solid than I would have like, but still turned out deliciously. Here's my adapted recipe: 1 pint white button mushrooms, minced 2 tablespoons butter 1 clove minced garlic salt and pepper 2 tablespoons heavy cream 2 tablespoons fresh flat leaf parsley, chopped 4 eggs Preheat the oven to 350 F. Butter three or four small glass baking dishes. Sauté the mushrooms and garlic in butter, adding salt and pepper to taste. When most of the mushroom liquid has cooked off, add the heavy cream and parsley and stir well. Divide evenly among the baking dishes, make a little well, and then crack eggs into dishes. One or two per dish. Salt and pepper the egg, then place in a 9x13" baking pan with two inches of water (use hot or boiling water). Bake 5-10 minutes, or until the egg white is set and the yolk still runny. For firmer eggs, bake 10-15 mins. I did not use boiling water, so the whole thing took more like 20-30 mins for the water to heat up properly, and the yolks got firmer than I would have liked. Tasted delicious, though! This is a very rich dish, so best served with something green and piquant - I chose baby arugula with a sharp homemade vinaigrette (2 tablespoons olive oil, 2 tablespoons lemon juice, 1 tablespoon dijon mustard was enough for 3 or 4 servings of salad), which was just about perfect. You don't have to be a fan of mushrooms to like this dish - white button mushrooms aren't particularly strong-flavored - they just tasted rich and meaty. And despite the fact that eggs en cocotte look and taste incredibly fancy, they were very easy and relatively fast to make. If you were cooking brunch for a crowd, you could certainly prep the mushroom mixture in advance, have the bain marie water on the boil, and make the eggs your last task for a beautiful brunch. With the simple arugula vinaigrette on the side, something sweet and bready (that recipe is coming soon, too) and some fresh fruit and mimosas, you've got yourself a winner. Do you have a favorite egg recipe? The Food Historian blog is supported by patrons on Patreon! Patrons help keep blog posts like this one free and available to the public. Join us for awesome members-only content like free digitized cookbooks from my personal collection, e-newsletter, and even snail mail from time to time! Don't like Patreon? You can leave a tip!

0 Comments

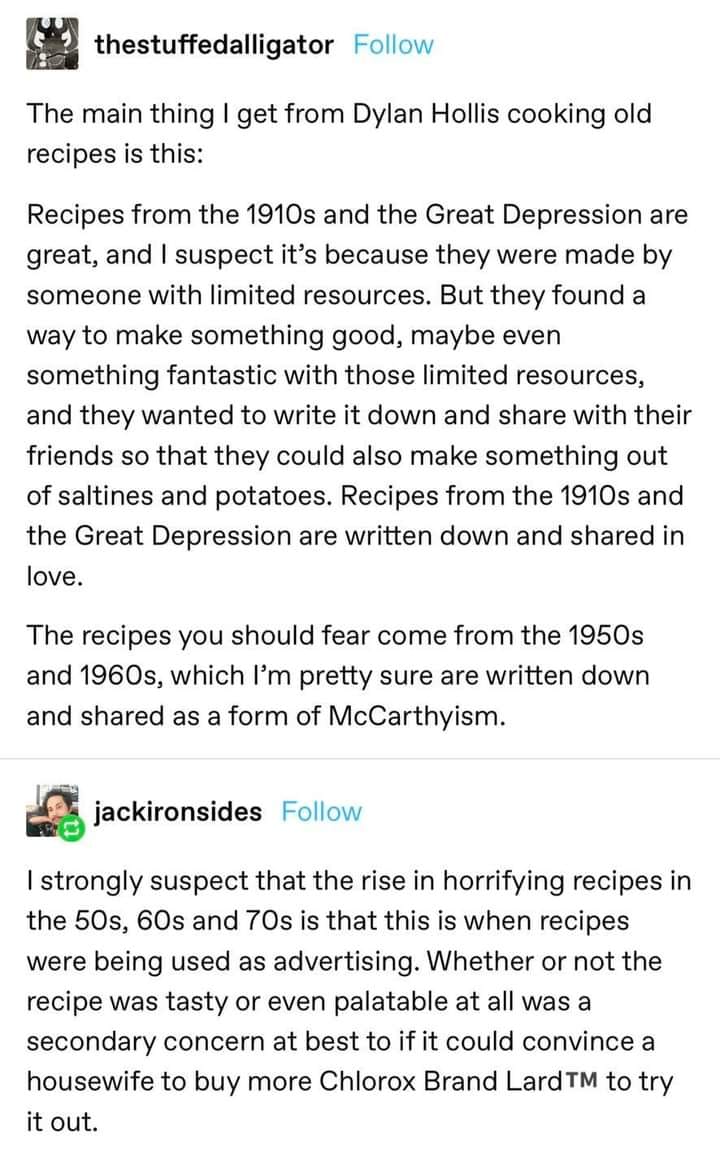

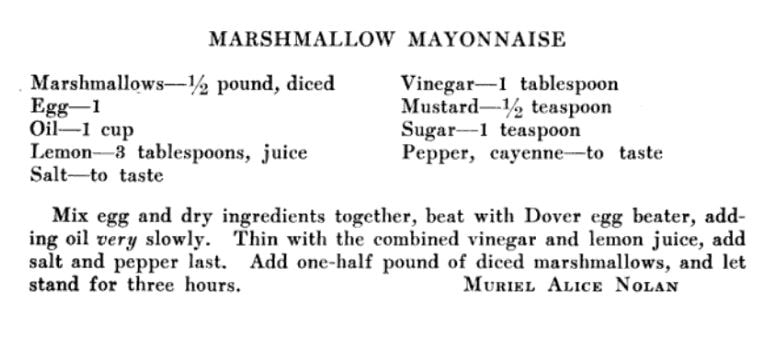

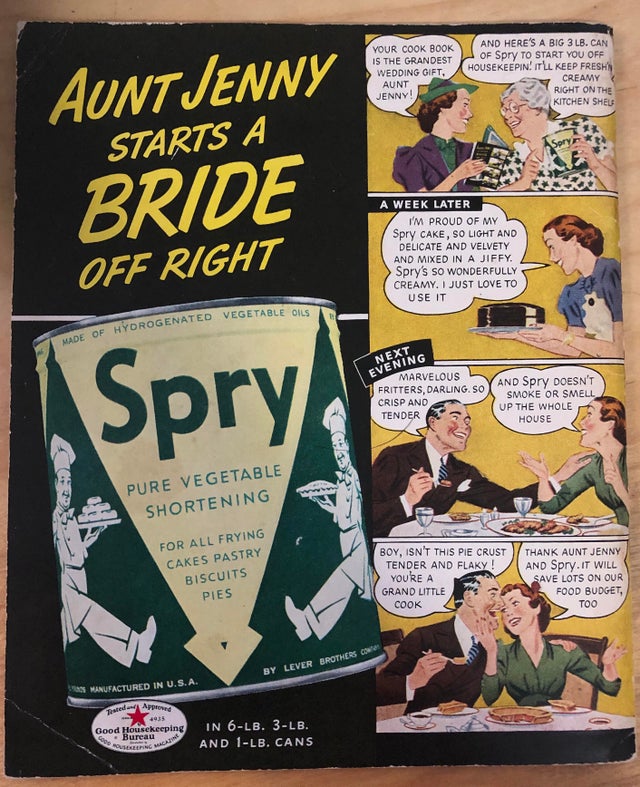

Well friends, I said I was contemplating a part two to last week's examination of 1950s food, and this meme kept popping up on my socials, so here we are again! This one isn't quite as inflammatory, and no fun illustration to catch your eye, but it makes a similar claim nonetheless. Here's the original text: The main thing I get from Dylan Hollis cooking old recipes is this: If you haven't seen any of Dylan Hollis' TikTok videos, I recommend them! He's hilarious. Not a food historian, but he cooks historic recipes and taste tests them. Some are horrific, but most are delicious - and while Dylan's reactions are 99% of the fun, his shock when things are actually tasty, while hilarious, does grate a little sometimes. Yes, people in the past really did know what they were doing! The meme claims that the food of the 1910s and the Great Depression were better than the 1950s, and were made with love, working with limited ingredients, whereas 1950s recipes were made to sell products during the McCarthy era. And while those ideas aren't necessarily wrong, they're definitely not the whole story. The time period of 1900 to 1950 is my favorite time period for cookbooks. They usually have decent instructions with things like measurements and oven temperatures, but are still from scratch. USUALLY being the key word there. Because starting in the 1870s, corporate food brands started publishing cookbooklets to sell their products. One of the earliest adopters of this sales tactic? Cottolene brand shortening. Not exactly lard, but pretty darn close! A lot of the corporate cookbooks and cookbooklets of the late 19th and early 20th century were primarily for ingredients. Different brands of flavorings and spices, baking powder, flour, shortening or lard, etc. were the main branded food products at the time. A lot of major food companies today started out as flour companies, including General Mills. So the cookbooks were largely normal scratch recipes that just recommended the cook or baker use the branded ingredients, but it was easy to substitute whatever you had on hand. And then, we started to get corporate food products like Campbell's canned soups, and Libby's canned corned beef, and powdered Knox gelatine and Jell-O, and other foods that were closer to finished foods already. You can only eat so much soup in a week. So how was Campbell's to get people to eat more of it? In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, we had more and more women graduating from food and nutrition schools and college programs. Domestic scientists and expert cooks and home economists happily filled the role of cookbook authors and test kitchen managers for food corporations. Which is how we got things like tomato soup spice cake (Dylan Hollis does a recipe from the 1950s, but it was actually invented in the 1920s!), cream of whatever soup casseroles, and marshmallow mayonnaise. While tomato soup spice cake is probably delicious (at least, Dylan Hollis thinks it is!), and cream of whatever soup is a lot easier than white sauce, I'm not sure about the marshmallow mayonnaise, but the cookbook says to serve it with fruit salad, so maybe it is? Who am I to judge? The point being, by the 1910s, there were plenty of marketing cookbooks and advertisements with recipes for processed foods for housewives to choose from. And while home economists were cranking out recipes that were sometimes smash hits and sometimes abject failures, there was a bit of a storm brewing in households around the country. Mainly, the "servant problem." For most of the 19th century, middle and upper-middle class families had at least one household servant (or enslaved person, prior to the Civil War) who did the bulk of the heaviest household labor. Middle class women and their daughters did household work too, but were generally spared things like scouring pots and scrubbing floors and hauling water and coal. But at the turn of the 20th century, we started to get pink collar jobs - being a shop girl or secretary or teacher or nurse was preferable for many women to the 24/6.5 schedules of being in service. Rural families usually had lots of children to help with agricultural labor, but in a family of 6 or 10, the older girls always helped care for the younger children and everyone did household chores. As families shrunk and household servants became harder to find and more expensive, more and more women had to do with less and less help at home. At the same time, education levels for women were rising. Girls stayed in school beyond the elementary level and attended high school and college in larger and larger numbers. Many parents also wanted better lives for their children than they had, and wanted to spare girls the drudgery of household labor. Upper and upper-middle class girls, in particular, had been raised in households with servants and mothers who spared them all but the basics of running a household. So when they married, all of a sudden girls with college educations had to figure out household budgets and weekly grocery shopping and cooking on their own, without many skills or resources to help them. Enter the ad man and the home economist. Swearing to save the clueless young bride from a lifetime of drudgery, while still pleasing her husband, all sorts of companies targeted young, inexperienced women just starting their households, but none perhaps as diligently as Spry, which manufactured first lard and later shortening (there's that lard reference again!). Aunt Jenny was the fictional grandmotherly character who knew just everything and would teach it all to her clueless niece. And of course, the secret was always a giant can of Spry. While Spry cookbooklets joined the legion of competitors, it was their cartoon-style print ads and extensive radio shows and advertisements that helped sway millions of American women to the Spry way of life. Is it any wonder that women who married in the 1930s and '40s raised children in the 1950s on corporate foods? Untrained, without the household help of their mothers and grandmothers, and with high expectations for home cleanliness and cooking three meals a day, 364 days a year would be enough to drive anyone into the arms of kindly home economists and fictional characters like Aunt Jenny, Mary Lee Taylor, Betty Crocker, and others. Recipes as advertisements for corporate foods did NOT start in the 1950s by any means. But the meme is somewhat correct in that scratch cooking was more prevalent in the Great Depression in particular, largely because at the time industrial foods were still more expensive than cooking from scratch, and because women who were adults in the 1930s were more likely to have been born into households that still taught them something about cooking and household management. And although the balance of population in the United States tipped from rural to urban in the 1920s, we still had a huge population of people primarily involved in agriculture, meaning families were larger (my mom's parents, born to farmers in the 1930s, came from families of 9 and 10 children, respectively), so women had more household help. Rural areas were also slower to adopt new fashions, including fashionable food, and often had less access to industrial goods of all sorts, including processed foods. Rural families were also much more likely to grow and preserve the bulk of their own food, well into the 1970s, than the rest of America. If you had land and free labor, it was certainly cheaper than buying commercially canned goods. If your grandmother grew up in a rural area during the Great Depression, like mine did, she probably learned how to cook from scratch. But by the 1950s, she was raising kids on her own, and maybe had a career of her own, or was supporting her husband's career, which meant less time to cook from scratch as she cared for her own children and a house with higher standards of cleanliness and fashion than her mother's with a lot less help. At the same time, in the 1950s, the general consensus was that industrial foods were the wave of the future - they were boons to help a busy housewife, not things to be scorned and rejected. And as incomes rose, it was much easier to purchase foods than doing your own home preserving. And while the Great Depression did result in a lot of creative cooks (banana bread, for instance), I find the mention in the original meme of Saltines ironic. Although Saltines and cracker companies like Ritz didn't invent cracker-based mock apple pie (that dates back to the 1850s, believe it or not), they sure hopped right on that bandwagon and used it as a selling point. Necessity is the mother of invention. But rising incomes are the mother of convenience. And while McCarthyism probably did prevent the spread of some delicious and interesting foodways through its xenophobia and rigid conformity, the road to corporate convenience foods was a long one. They didn't appear overnight once the calendar ticked over from 1949 to 1950. Indeed, scratch cooking and baking continued well into the 1950s, and many of the foods we associate with the 1950s (Cool Whip, anyone?) weren't actually invented until the 1960s. For instance, the Pillsbury Bake-Off baking contest didn't start until 1949, and while modern incarnations of the contest are usually dominated by mutated versions of whatever convenience food Pillsbury has cooked up (usually crescent rolls or cinnamon rolls or canned biscuits), the original contest was meant to promote Pillsbury flour, so the recipes are all from scratch. And looking at my food historian library shelves, the 1950s section has plenty of community cookbooks filled with can-of-this, box-of-that recipes, and advertising cookbooklets galore, but there are also cookbooks like The Magic in Herbs (first printed in 1941 but on its seventh printing by my 1950 copy) and The Peasant Cookbook (1955, and my copy was from the library of the Ladies' Home Journal!), and Whole Grain Cookery (1951) and those community cookbooks always had scratch recipes in them, too. And my 1930s section? I have more corporate cookbooklets from the 1930s than any other era! Like most of history, individual decades might be changed and marked by big events, but history is complicated. In the Progressive Era we had brutal strikes and food riots, but we also had Gibson Girls and Vanderbilts and Rockefellers. During the Great Depression we had the Dust Bowl and migrant workers, but we also had the glamour of Hollywood. And yes, in the 1950s we had McCarthyism (and sexism and racism) and processed food, but we also had folks like James Beard and Julia Child and plenty of scratch cooking. So let's stop stereotyping decades and accept them for what they are - complicated, messy, and fascinating time periods with both good food and bad. And the next time you see a corporate food cookbook from the 1950s - give it a gander. You might be surprised by what you find inside. There are good recipes in just about every cookbook, if you take the time to look. The Food Historian blog is supported by patrons on Patreon! Patrons help keep blog posts like this one free and available to the public. Join us for awesome members-only content like free digitized cookbooks from my personal collection, e-newsletter, and even snail mail from time to time! Don't like Patreon? Leave a tip! |

AuthorSarah Wassberg Johnson has an MA in Public History from the University at Albany and studies early 20th century food history. Archives

July 2024

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed