|

This post contains Amazon affiliate links. Happy Valentine's Day, dear readers! I'm not typically one for Valentine's Day (although I've written about it here and here), but this year we decided to celebrate a friend's birthday with a Valentine's Day-themed tea party! I will admit the idea started with cute pink tea cups, spoons, and tea bag rests I saw at Target, and it kind of snowballed from there. But if you've been a longtime reader you'll know how much I enjoy designing and putting on tea parties (see: here, here, and here). I have an addiction to vintage dishes and linens, so it only seems fair that I drag them out every now and again. This tea party does not have any particular historical recipes attached to it, although every time I throw one I feel I am following firmly in the footsteps of my home economics predecessors, many of whom enjoyed a themed party even more than I do. Designing Your Tea PartyHalf the fun of throwing parties is dreaming them up and bringing together all the various accoutrements that make it nice. I've mentioned the pink teacups and saucers, golden flower spoons, and heart-shaped tea bag rests already. Those were the catalyst. But I also pulled from my collection of vintage pretties, all of it thrifted: a cherry blossom tablecloth, my favorite lace-edged milk glass platter and coordinating dessert plates, a gold-edged glass platter and coordinating luncheon plates, gold-rimmed etched highball glasses, vintage martini glasses, a beautiful cut glass footed compote I picked up recently, and one of my many milk glass vases for two bunches of fresh tulips. I did splurge on a few more things - I got some cute Valentine's Day decorations; a garland of felt hearts for the living room and a table runner for the coffee table. A set of heart-shaped cookie cutters in a variety of very useful sizes. My favorite purchase was a set of beautiful pink glass nesting bowls rimmed in gold. We only used one bowl for the tea party, but I love them so much. And the one that got the most comments was this rose-shaped ice cube tray, which turned grapefruit juice into gorgeous icy roses. I probably could have used more, but much of my milk glass got put away last Christmas and is now up under the eaves. One of my spring cleaning projects is to organize all my totes of spare dishes and decorations and put them all in the more easily-accessible basement, clearly labeled, so I can find things and use them more often. If you are in search of your own tea party collection, my best advice is to buy what you love, and damn the naysayers. My second-best advice is to buy things that coordinate with a variety of themes. Which is why I love milk glass so much, because it knows no season, and white dishes can always be spruced up with special touches of color. What every tea party needs:

Of course the most important ingredient for a tea party is at least one guest! Tea parties are always better with conversation. Menu planning is also a great deal of fun for me, and I love the challenge of coming up with something new each time I throw a party, alongside tried-and-true recipes. For this party, the tried-and-true recipe was for my Russian-style pie crust, which was used for both the savory pie and the letter cookies. The new was the vegetarian "chorizo," which was a riff on my lentilwurst recipe, and which turned out VERY well! The vegetable flower pie I knew would work in theory, but the execution was more difficult than I expected. If I did it again, I would definitely want a Y-style vegetable peeler like this one for the sweet potatoes. Valentine's Day Tea Party MenuFIRST COURSE: Savory Vegetable Flower Pie Heart Shaped "Chorizo" Sandwiches Hot Pink Salad SECOND COURSE: Strawberry Rhubarb Pie a la Mode Love Letter Cookies Red Fruit Salad BEVERAGES: Ice water Grapefruit Mocktail Cherry Blossom or Valentine's Day Tea Sadly my time these days is far more limited than it used to be, so my dreams of an almond cake with rose petal jam filling, lavender shortbreads, rose meringues, and other tasty treats fell victim to my schedule. Still, although some of these were a struggle, I was delighted in how they turned out. Normally I would make these separate posts, but for you, I'll lump all the recipes into one. The only thing that was store bought was the pie, which was purchased from a local farm who makes the best pies. And since our birthday girl loves pie more than cake, that was her birthday treat, in addition to the homemade ones. Savory Vegetable Flower Pie RecipeThis flavor combination sounds unusual, but it's delicious. Crust: 1 stick butter 1/4 pound fresh ricotta or farmer cheese 1 cup flour Filling: 1 cup ricotta 1/2 cup feta garlic salt dried thyme Topping: sweet potato small shallots roasted red pepper Preheat oven to 350 F. Cream softened butter and ricotta, then stir in 1 cup flour. Knead well and let rest. Whirl the ricotta and feta to blend and then add seasonings. Peel the sweet potato and cut into paper-thin slices. Peel the shallots cut off the tops, and then cut through them lengthwise but not through the root end. Cut multiple times to make "petals." Then trim the root end without cutting all the way through. Roll the dough out thinly and drape in a pie plate. Fill with ricotta filling, then arrange sweet potato slices into roses, add the shallots and spread the "petals," and then fill any extra spaces with slices of roasted red pepper rolled into rosebuds. Trim pie crust and crimp. Use remaining crust to cut out "leaves" and bake separately. Bake pie 30-40 mins or until sweet potatoes and shallots are cooked through and crust is golden brown. Vegetarian Lentil "Chorizo" RecipeThis recipe is a riff off my lentilwurst revelation. It turned out splendidly. 1 cup red lentils 1 1/2 cups water 1/4 cup butter (or olive or coconut oil) 1 small onion 1 red bell pepper 2 teaspoons smoked paprika 1 teaspoon chili powder 1 teaspoon garlic powder 1/2-1 teaspoon garlic salt 1/2 teaspoon oregano 1/4 teaspoon cumin 1/4 teaspoon black pepper Combine the lentils and water in a small stockpot. Bring water to a boil, then reduce heat and simmer 20ish minutes, or until the water is absorbed and the lentils are very soft. Peel the onion and seed the pepper, then mince very finely or whirl in a food processor until finely cut. In a stock pot, melt the butter over medium heat and add the onion and pepper. Cook until the butter is mostly absorbed and the vegetables very tender. Add the spices and lentils and cook to combine. When fully blended, taste and add more salt if needed. To make sandwiches, thinly slice white bread and cut into heart shapes, then spread with the lentil filling. Pink Salad RecipeI like to have something a little lighter for tea parties, usually a salad. But of course for Valentine's Day I didn't want any-old green salad! Plus, one of the challenges I set for myself was to keep this at least partially seasonally-appropriate. So this was my answer. 1/4 head red cabbage 8 red radishes 1/4 cup pickled red onion salt olive oil lemon juice Finely shred the cabbage and slice the radishes paper-thin. Toss with salt and let rest, then add a little olive oil and lemon juice. You can make this in advance if you want it to be extra-pink and slightly less crunchy, but be forewarned that the purple juices will stain just about everything, so eat carefully! Love Letters Cookie RecipeI'll admit - I saw this on Pinterest and thought it was too cute. I used my fool-proof ricotta pie crust instead of traditional butter crust, and while delicious, the letters did puff up a bit in the oven. Plus those little hearts are a pain to cut out by hand! 1 stick (1/4 cup) butter 1/4 pound ricotta or farmer cheese 1 cup flour cherry jam (I like Bonne Maman) Cream butter and ricotta and stir in flour. Knead well until combined. Roll out very thin and cut into squares. Place a teaspoon of jam in the center, then fold up one side and the other two to make an envelope. Add a heart cut out of crust to keep the edges from popping up. Bake at 350 F on parchment paper for 15-18 minutes, or until golden brown. Grapefruit Mocktail RecipeThis is one of my favorite mocktail recipes and it is dead easy, you ready? 1 part grapefruit juice 1 part gingerale And that's it! I like to use Simply Grapefruit, as I think it has a nice balance of sweetness and bitterness, but you could use any kind. The combination tastes so much more sophisticated than it is - not too sweet, not too bitter, not too bubbly, and curiously addictive for the adult palate. For folks who don't drink alcohol, it's a great alternative to a mixed drink that isn't sugary-sweet. Selecting TeasTea parties traditionally feature just black tea, but as a non-traditional person and someone who doesn't enjoy a lot of caffeine, I don't usually drink black tea. However, since this was a special event, I decided to bring out some special teas just for Valentine's Day. Harney & Sons is a New York-based tea producer (and therefore local for me) who makes delicious blends. I did a big order last year around this time and got their "Valentine's Day" blend for free. I was skeptical at first, but it's a delicious blend of black tea, chocolate, rose, and other fruity flavors. Curiously addictive. The birthday girl is a big fan of green tea, so when I saw the Cherry Blossom variety, which is a mix of green tea with cherry and vanilla flavors, I decided to get that as well. Both were excellent and did not need any sweetener or milk to accompany the rest of the menu. All in all it was a delightful afternoon. The birthday girl was happy, the husband was happy, and I was happy! We went for a post-party walk in delightful weather and did a little shopping at a nearby town, got caught in a rainstorm, then headed for home. Later that night we ran some more errands and I treated myself to some adorable jigsaw puzzles, because they remind me of my mom and I need some non-screen time activities! They've been fun, but man my back is not up for too much hovering over a table searching for pieces!

It always gives me joy to built a beautiful table for family and friends. My best Valentine's Day present to myself! How are you celebrating?

1 Comment

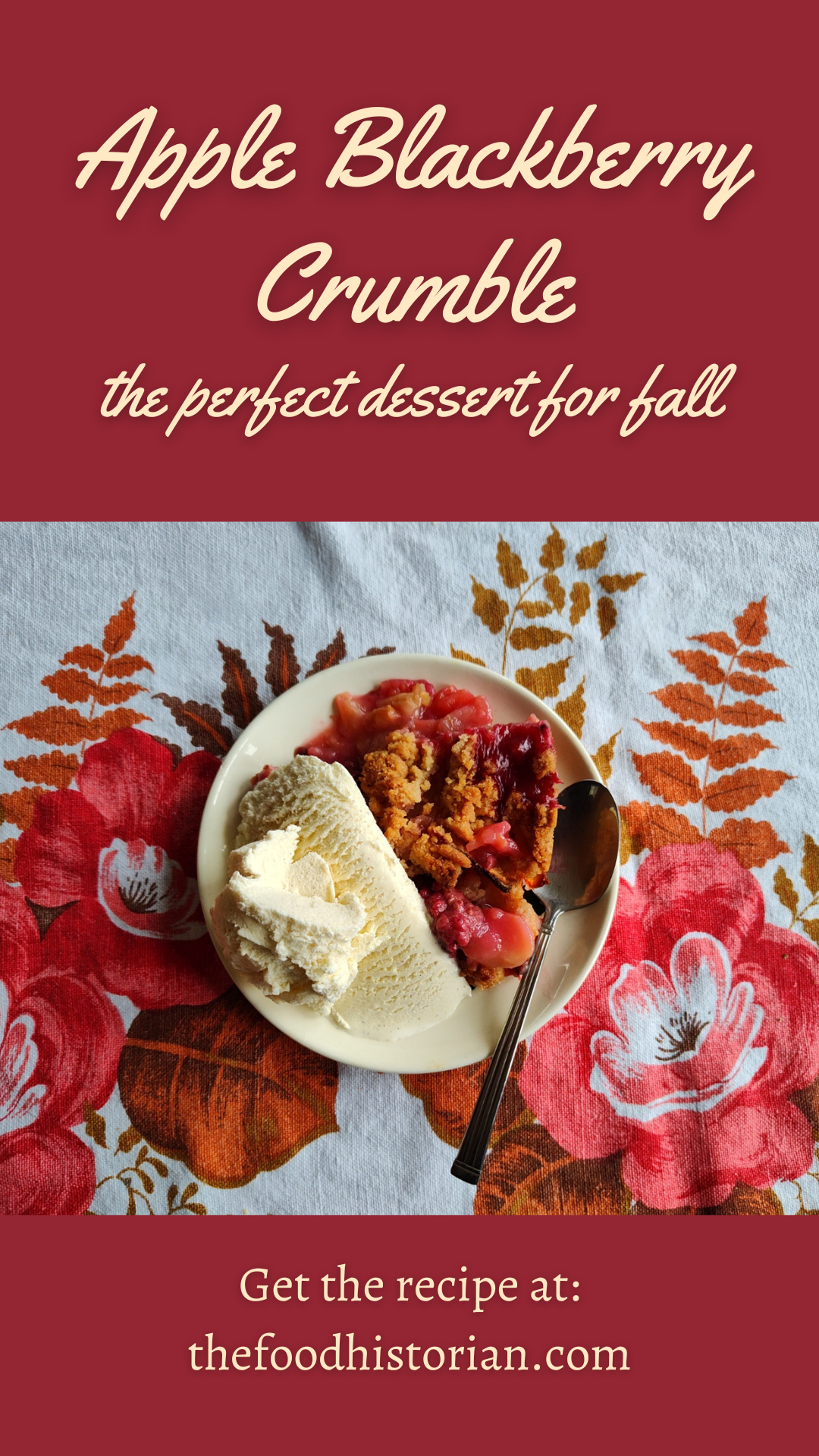

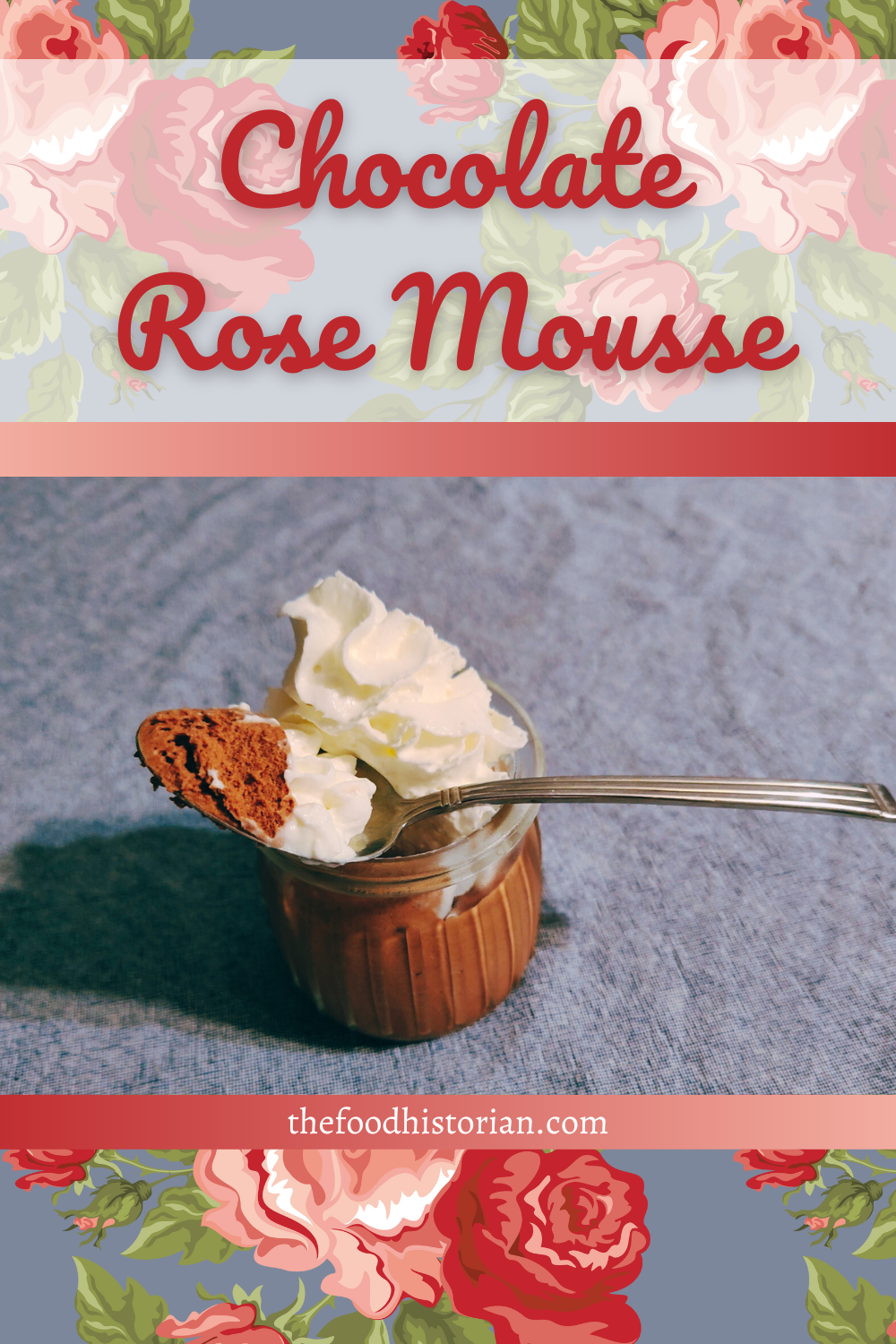

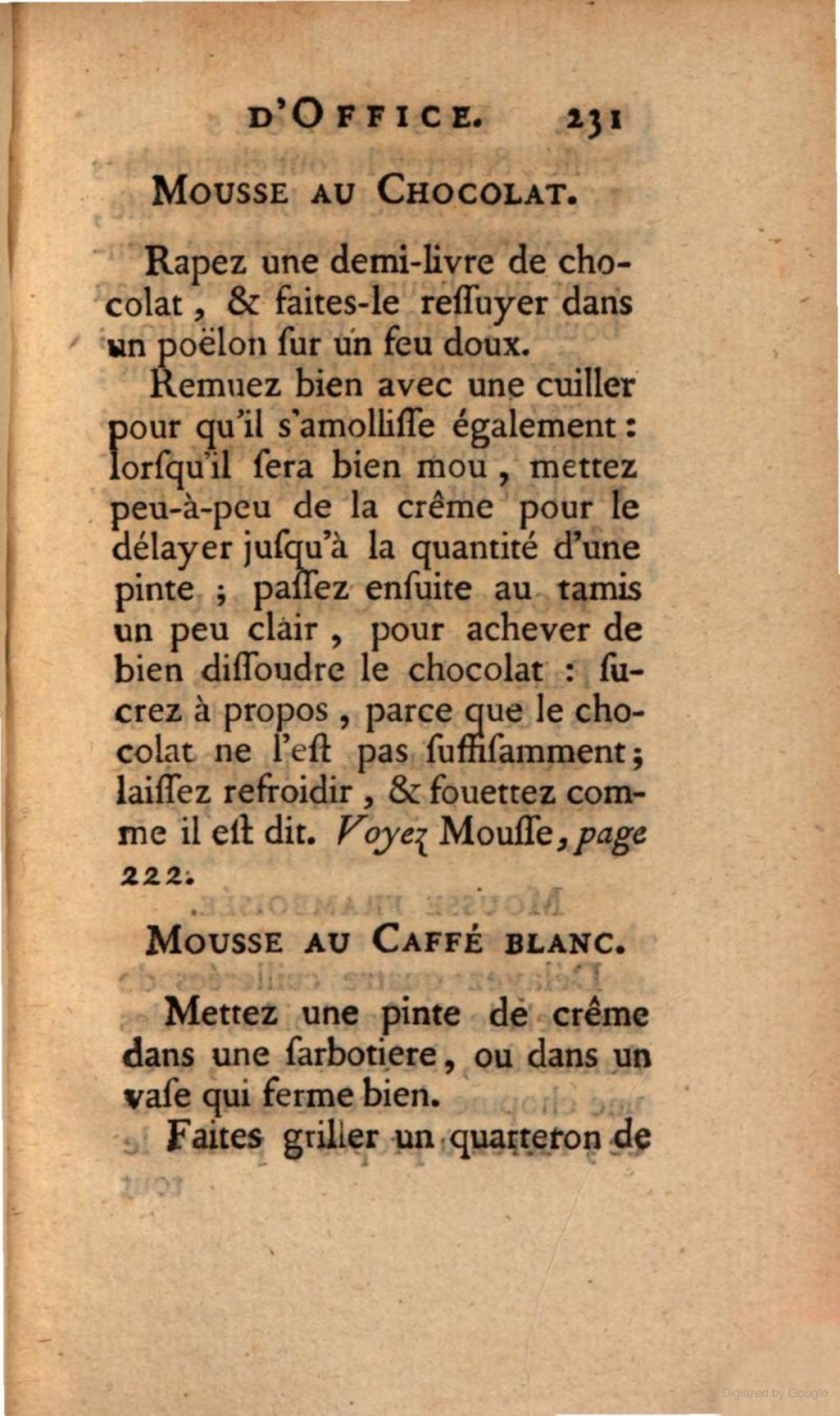

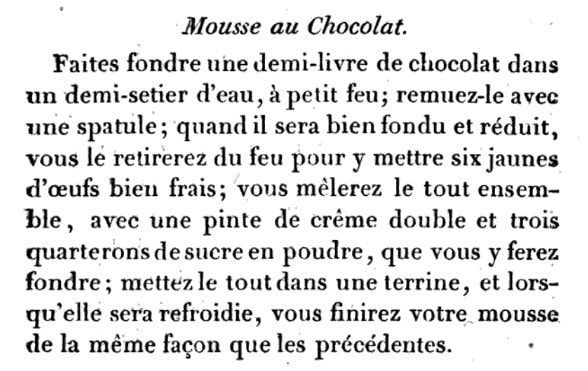

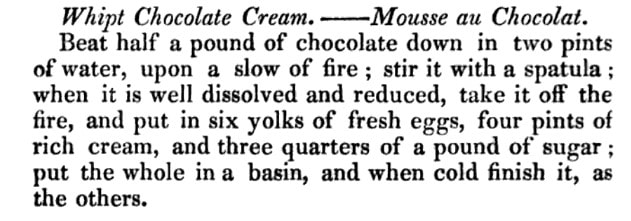

In throwing an Autumnal Tea Party (see yesterday's post!), I wanted a simple but impactful dessert. Apples are plentiful in New York in September, but plain apple crisp, while delicious, didn't feel quite special enough for a tea party. The British have a long tradition of gleaning from hedgerows in the fall. Hedgerows often have apple trees, sloes, blackcurrants, and blackberries in fall. Sloes and blackcurrants are hard to find here in the US, but blackberries seemed like the perfect accent to the American classic. This recipe is endlessly adaptable as the crumble topping is great with any kind of fruit. You do need quite a lot of fruit for a crumble, which makes it nice in that it feels a little lighter on the stomach than cake or pie. These sorts of desserts were common in areas where fruit was plentiful and sugar and butter weren't. Apple Blackberry Crumble RecipeI never sweeten the fruit for a crumble (similar to a crisp, but without rolled oats) unless it is a very sour fruit like rhubarb or fresh cranberries. This topping has quite a lot of sugar, which is what helps make it so crunchy and delicious, but you definitely do not need additional sugar in the fruit, especially when pairing with ice cream. You can substitute whole grain flour for part or all of this to good effect as well. If you prefer a crisp, use 1/2 cup of flour and 1 heaping cup of rolled oats. 8+ small apples (I used a mix of gingergold and gala) 1 pint (2 small packages) fresh blackberries 1 1/2 cups all-purpose flour (plus more for the fruit) 1 scant cup white sugar 1/2 cup coldish butter 1/2 teaspoon salt 1/2 teaspoon pumpkin spice Preheat the oven to 400 degrees F. Peel the apples, cut into quarters, cut out the core, and slice. Wash the blackberries and drain. Toss the apples and blackberries with flour to coat (this will thicken the juices). Add to the baking dish. Then make the crumble. Mix the flour, sugar, salt, and pumpkin spice. Then cut the butter into small cubes, toss in the flour mix, and using your hands squeeze and rub it into the flour mix until it holds together when squeezed. Crumble gently over the fruit in an even mix, then bake for 40-50 minutes, or until the fruit is bubbly and thick and the crumble is golden brown. Serve warm with vanilla ice cream. There's nothing like a warm crisp with cold vanilla ice cream, and I think this is my new favorite kind. Blackberries and apples seem like a match made in heaven. What's your favorite autumnal dessert? The Food Historian blog is supported by patrons on Patreon! Patrons help keep blog posts like this one free and available to the public. Join us for awesome members-only content like free digitized cookbooks from my personal collection, e-newsletter, and even snail mail from time to time! Don't like Patreon? Leave a tip! The weather has finally turned, dear readers, and so I felt it was time for another tea party! I've had a long couple of weeks, and I wasn't really looking forward to spending one of my days off cleaning the house and cooking, but it was very much worth the effort and I'm glad we did it. Tea parties can be incredibly complicated, or very simple. My process is to think about the theme, and the flavors, and then come up with way too many ideas and then pare it down to what's possible. I wanted to honor the flavors of early fall, with something pumpkin or squash, apples, blackberries, and a savory bread. My original list also had gingerbread and shortbread cookies with jam, and scotch eggs, but that was too much! I wanted to keep the menu fairly simple, because I was quite sleep deprived after a big event over the weekend at work. So I maximized flavor and minimized effort, to great acclaim! The party (just three of us) ended up delicious, with a chilly, drizzly day with beautiful overcast light on our front porch. Ironically, we ended up having mulled cider, instead of tea, but I'm enjoying a cup of tea as I write this a few hours later, so I suppose it still counts! Autumnal Tea Party DecorIt can be tempting to go out and buy a lot of supplies for parties. I'm definitely as susceptible to that impulse as the next person! But I find what makes parties special is not how much everything matches, but the quality of your decor. I decorated my mantel with some of my favorite fall decorations - a coppery leaf garland, my favorite vintage china pheasant, a pretty vase with some fake flowers, a little green ceramic pumpkin. But when it comes to decking the table, nothing is better than nice tablecloth and real dishes. I grew up shopping thrift stores and garage sales and flea markets with my mom, so I've amassed quite a collection of vintage dishes and tablecloths over the years. Because I actually use my collection, I don't spend a lot of money on it. It pains me enough when a vintage piece gets chipped or broken. My frugal soul would be even more deeply wounded if it was a piece I had spent a lot of money on. This ended up being a very grandmother-focused display. The Metlox California ivy plates and a single surviving teacup I inherited from my grandmother Eunice, along with the green glass bowl I used for butter and the green glass saucers. My grandma Ruby found me the beautiful etched water glasses. The glass teacups embossed with leaves I picked up at a garage sale for a dollar for the pair. The milk glass is from my thrifted collection, and the beautiful tablecloth is a vintage one I forget where I found but it's probably one of my absolute favorites. I did not intend for the food to match the tablecloth, but that's kind of how it happened! When it comes to collecting, it's important to buy things you love, instead of focusing on what things are worth. Who cares how expensive it was if you think it's ugly? It's also important to choose things that are relatively easy to care for. I do not recommend putting vintage dishes in the dishwasher, but a lot of vintage tablecloths are meant to be washed. I find vintage textiles with a stain or two are often much less expensive than the pristine stuff, and then if you get a stain on them you don't feel quite so bad! Autumnal Tea Party MenuButternut Squash Soup with buttered pecans Sage Cream Biscuit Sandwiches with pickled apple, pickled onions, and sharp cheddar Dilly Beans Mulled Cider Blackberry Raspberry Hibiscus Water Apple Blackberry Crumble with vanilla ice cream Although I love to cook from scratch, the butternut squash soup was store-bought from one of my favorite soup brands: Pacific Foods Butternut Squash Soup, and I got the low-sodium version (affiliate link). I don't usually like butternut squash soup, but I know lots of people love it, so I thought I would give it a go. This one was so delicious, I was surprised how much I enjoyed it. I felt it needed a little something extra, so I toasted some chopped pecans in a little butter and salt, and the butter got a little browned. It was the perfect garnish. The blackberry raspberry hibiscus water was also store-bought, a simple cold water infusion from Bigelow tea which I found at the store the other day (affiliate link). It turned out lovely - not as strong as tea, just a hint of flavor to cold water. Very refreshing. Sadly, the color, which was a beautiful purple as it steeped, got diluted to a kind of washed purple-gray, which was less beautiful. But still delicious! Sage Cream BiscuitsI had thought about making scones for this tea party, but I don't have a reliable savory scones recipe, and since I was doing sandwiches, I thought biscuits would be better. This is an adaptation of my tried-and-true Dorie Greenspan cream biscuit recipe. It's almost fool-proof. This one is doubled. 4 cups of all-purpose flour 2 tablespoons baking powder 2 teaspoon sugar 1 1/2 teaspoons salt 1 heaping teaspoon dried sage (not ground) 2 1/2 cups heavy cream Preheat the oven to 425 F. Whisk all the dry ingredients together, and then add the heavy cream, tossing with a fork until most of the flour is absorbed. Knead gently with your hands (don't overwork!), then pour out onto a clean, floured work surface and knead, folding often, until it comes together. Pat into a large rectangle and cut into squares. Place on a parchment-lined baking sheet and bake 15-20 minutes or until golden brown. Serve warm, and to make the sandwiches, split the biscuits, butter them, and add sliced sharp cheddar cheese, a slice of pickled apple, and a few strands of pickled red onion. Top with more cheddar and the other half of the biscuit and devour. Serve with butternut squash and a side of dilly beans and mulled cider. I'll be following up with the recipe the apple blackberry crumble tomorrow, and the recipes for refrigerator dilly beans, pickled apples, and pickled onions will be available to patrons on my Patreon tomorrow as well. Do you like to have tea parties? What's your favorite autumnal food? The Food Historian blog is supported by patrons on Patreon! Patrons help keep blog posts like this one free and available to the public. Join us for awesome members-only content like free digitized cookbooks from my personal collection, e-newsletter, and even snail mail from time to time! Don't like Patreon? Leave a tip! Dear Reader, I finally did it, and not in a good way. A few weeks ago I hosted a beautiful (albeit hot and humid) French Garden Party, a belated celebration of Bastille Day, for approximately 30 people. The decorations were gorgeous and the food was fabulous and I did not take a single. solitary. photograph. My consternation was extreme. My beautiful screen porch was set with tables dressed in blue and white striped linens. It was BYOB - bring your own baguette, and folks brought fancy cheeses to go with the goat cheese and paper-thin ham I provided. I made homemade mushroom walnut pate and TWO compound butters - fresh herb and garlic, and lemon caper. I made beautiful French salads: potato and green bean vinaigrette, lentils vinaigrette with shallot and parsley and a hint of fresh rosemary, cucumber with tarragon and sour cream, celery with black olives and anchovies, peach basil. We had honeydew melon and both sweet dark AND Queen Anne cherries. We had wine and spritzers a-plenty. A friend brought chocolate cream puffs. I made lemon pots de crème and earl grey madeleines. But the absolute star of the show was this chocolate mousse, which I flavored with rose water. And since I had one little glass pot left over from the party, I snapped a few photographs a few days later to give you the incredibly easy recipe so that you, too, may feature this glorious star, and have your guests talking about it for days afterwards (no really - they did). But course, I wouldn't be a food historian if I didn't give you a little context, and I was curious about the history of chocolate mousse, so here you go: A Brief History of Chocolate MousseGoodness there is a lot of nonsense out on the internet about chocolate mousse! Way, WAY, too many sources say it was invented by Toulouse Lautrec, and that it was called "mayonnaise de chocolat." People. Chocolate mousse dates back to at least the 18th century, if not earlier, so it was around long before Monsieur Lautrec. I did, to my surprise, find a couple of recipe references to "mayonnaise au chocolat." It sounds so ridiculous as to be fake, but this was apparently a real recipe, albeit a name I can only date to the 20th century. One recipe is from a 1909 French cookbook, which calls for melting chocolate with egg yolks and adding beaten egg whites, and offers a clue to the name: it says at the end to mix the egg whites and the chocolate mixture "like ordinary mayonnaise." A few references in the 1920s and '30s, and then where it was probably popularized in America - a reference from a 1940 issue of Gourmet magazine (not readable online, alas - if anyone tracks down a hard copy of the original, let me know!). Another recipe is from a 1951 French cookbook, with not very detailed directions. According to my translation, "mayonnaise au chocolat" mixes melted chocolate with egg yolks and a few tablespoons of cream which is then cooked and then mixed with egg whites (unclear whether or not they are beaten stiff or not, but likely yes) and chilled. Another is from the 1961 edition of Mastering the Art of French Cooking by Julia Child and Simone Beck, which has a recipe for "Moussline au Chocolat, Mayonnaise au Chocolat, Fondant au Chocolat" (yes, three names for the same recipe!) the subheading of which reads "Chocolate Mousse - a cold dessert." Mousseline is actually a sauce mixed with whipped cream (for instance, you can turn hollandaise sauce into a mousseline by adding whipped cream), whereas mousse is a thickened chilled dessert made with whipped cream. The Julia Child recipe conflates the two, and her recipe calls for an egg yolk cooked custard mixed with melted chocolate, with whipped egg whites folded in. It is then served with crème anglaise or whipped cream. So, none of these recipes are truly chocolate mousse, because the mixtures contain no whipped cream whatsoever. But Toulouse Lautrec and a crazy-to-Americans name like "chocolate mayonnaise" is so much more dramatic than doing actual historical research and looking at primary sources. SIGH. People. We can do better. The earliest references to "chocolate mousse" I could find date to 1687 and refer to the habit of Indigenous peoples in Central America of frothing their chocolate beverages with either a mollinio or by pouring them between cups. A habit which Europeans apparently adopted. A 1701 French dictionary continues the reference to frothy chocolate beverages in its definition of "mousser" or "to foam." The earliest reference I could find to the dessert mousse we know and love today comes from the 1768 French cookbook, "L'art de bien faire les glaces d'office ou les vrais principes pour congeier tous les rafraichissemens" or The Art of Making Ice Cream Well, or the True Principles for Freezing All Refreshments. And lest you think it is just about ice cream, the extremely long title adds, "Ave Un Traite Sur Les Mousses," or "With A Treatise On Mousses." Chocolate mousse (as pictured above) is simply one of dozens of mousse recipes listed, but the early versions are quite similar to the modern. Grate the chocolate and melt it in a saucepan over low heat, then add cream, little by little, to thin it down. Pass it through a sieve, sweeten it, and then let cool and whisk to a foam. By the 19th century, we're adding egg yolks to make a smoother, more custard-y base, as you can see from this pair of recipes by early French restauranteur Antoine Beauvilliers, who published his 1814 "The Art of Cooking" as a French cookbook that became foundational to generations of French chefs and home cooks. English cooks, however, had access before that, judging by this 1812 recipe, which also called for egg yolks. We're still adding large amounts of whipped cream, though, keeping in classic mousse style. It took a bit longer for Americans to adapt to chocolate mousse, although they were prodigious chocolate drinkers, and certainly by the mid-19th century were consuming chocolate custards and ice creams. It wasn't really until (as far as I and the Food Timeline can tell) celebrity cookbook author and cooking school teacher Maria Parloa intervened that it got popular. The Food Timeline cites a 1892 article with Miss Maria Parloa lecturing on chocolate mousse, among other things, but I found a reference dating back to 1885 where she's lecturing on chocolate mousse in Buffalo, NY. However, it doesn't seem to be QUITE the same as we consider chocolate mousse today. Her 1887 recipe for it calls for freezing it like ice cream, albeit without stirring. Regardless of whether the recipe calls for egg yolks or not, or whether it's frozen or not, chocolate mousse in the modern style is easier to make than you'd think. Chocolate Rose Mousse RecipeA French Garden Party called for something easy to prepare and delicious for dessert. Because it was a garden party, I decided on chocolate pots de crème or mousse flavored with rose fairly early on. I used to dislike floral flavors, but after making an Egyptian rosewater dessert last year, and trying Harney & Sons seriously divine Valentine's Day tea, which was chocolate black tea with rosebuds (affiliate link), I was smitten. After realizing how many eggs I'd go through making a triple batch of both lemon AND chocolate pots de crème, I decided to do just the lemon (15 pots) and do the rest as chocolate mousse (15 pots). I found these adorable little glass pots with covers on Amazon, should you care to purchase them yourself from this affiliate link. I adapted several recipes online, and since I didn't want to mess with steeping the cream with rosebuds or rose petals or any other options, I decided to go the less expensive and way easier rose water direction. Rose water is used frequently in Middle Eastern cooking, and is often less expensive in the "ethnic" section than in the spice aisle. In preparing for the party, in which I was attempting a brand new recipe, I didn't want to try to mess with egg yolks any more than I already had to with the lemon pots de crème (which turned out only okay). So the simple mixture of heavy cream, dark chocolate, and a little icing sugar seemed best. I then added rose water to taste, which turned out about perfect. Here's the reasonable-serving recipe, which I tripled to get 15 generous servings for the party. This makes more like 6 servings, 4 if you're being greedy. 1 1/2 cups heavy cream (I used a local dairy brand, which is richer than national brands) 1 cup high-quality dark chocolate chips (like Guittard) 1/4 cup powdered sugar 1 teaspoon rose water Heat a saucepan of water over medium heat, bringing it to a simmer. Place a heat-proof bowl (glass or metal) over the simmering water and add 3/4 cup heavy cream and the chocolate chips. Stir gently until the chocolate chips are completely melted. Remove from heat. In a large bowl, beat the remaining 3/4 cup heavy cream until you get soft peaks, then add the 1/4 cup powered sugar and beat until you get stiff peaks. Add the rose water and beat to combine. 1 teaspoon should be enough to stand up to the chocolate, but taste the whipped cream. The rose water should be present, but not overpowering. If faint, add another 1/2 teaspoon and beat again. Then, using a ladle, add approximately 1/3 cup of the cooled chocolate-cream mixture to your whipped cream, one ladle at a time, and gently fold to combine using a rubber spatula. To fold, use the spatula to cut down the center of the whipped cream mixture and scrape up from the bottom. Rotate the bowl slightly, and repeat the action, until the chocolate is incorporated. Add another ladle of chocolate and continue until you have folded in all of the chocolate without totally deflating the whipped cream. Spoon into small glass jars or custard cups and refrigerate until ready to serve. It was so gorgeous. Light but rich, with a subtle hint of rosewater, which added fascinating depths to the chocolate. Folks gobbled it all up, and it was by far the best dessert of the party. The one lonely little pot left allowed me to take the above photo the following day, so you're welcome! I didn't serve it with whipped cream during the party, and it's admittedly a little overkill, but it does look pretty. So now you have the recipe AND some history, plus some food history mythbusting! So do yourself a favor and go splurge on some high-quality ingredients and treat yourself and your loved ones to this easy and stunningly delicious dessert. To quote Julia, quoting the French, Bon Appetit! The Food Historian blog is supported by patrons on Patreon! Patrons help keep blog posts like this one free and available to the public. Join us for awesome members-only content like free digitized cookbooks from my personal collection, e-newsletter, and even snail mail from time to time! Don't like Patreon? Leave a tip!

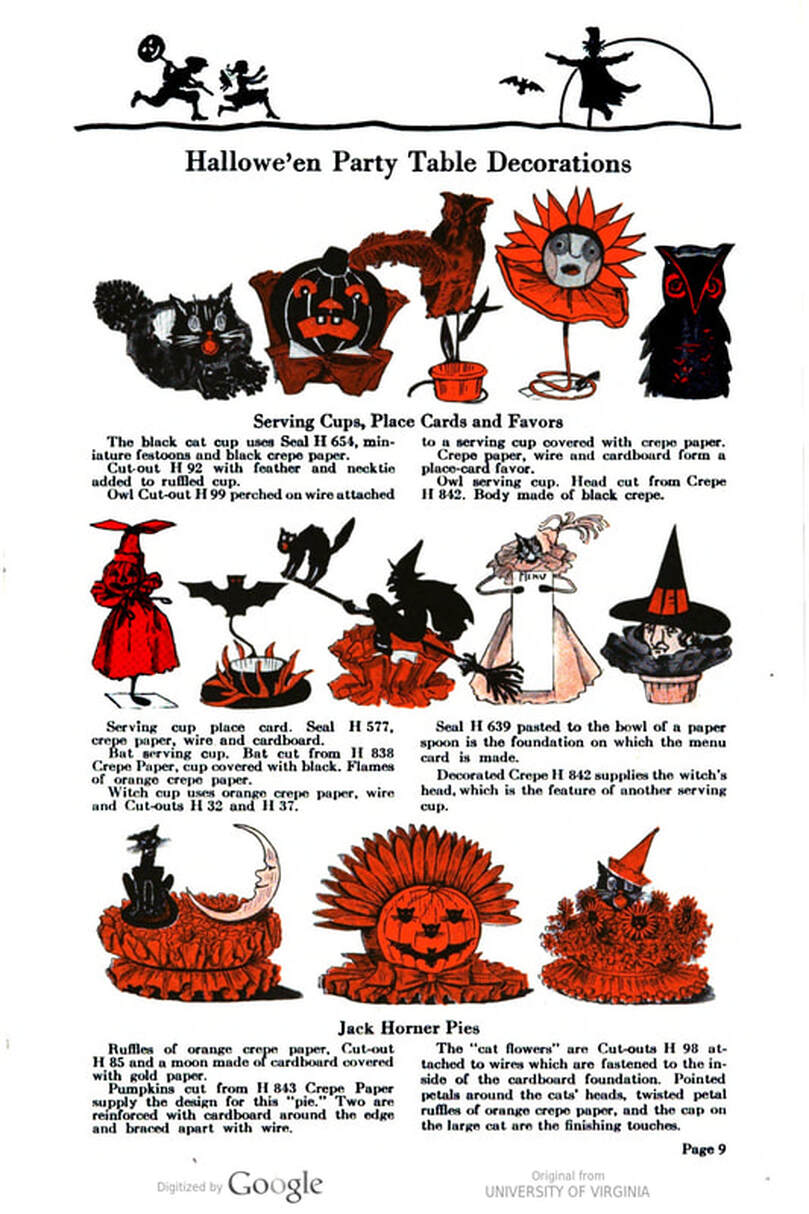

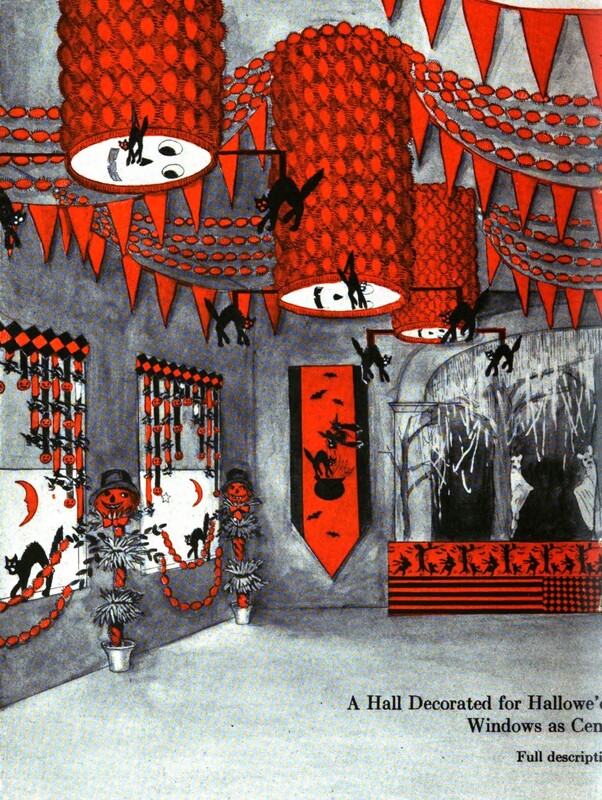

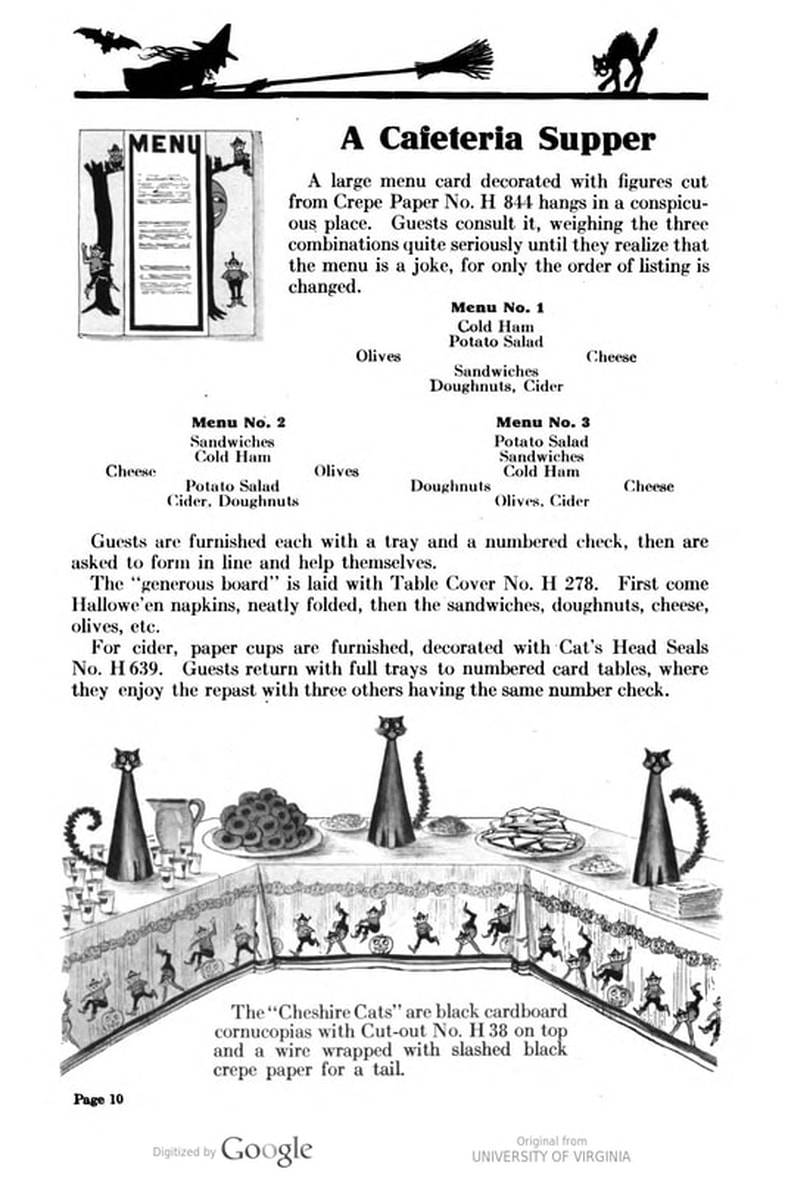

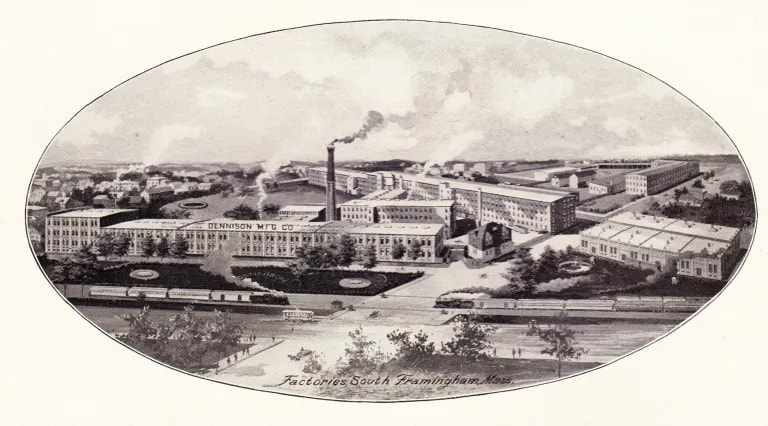

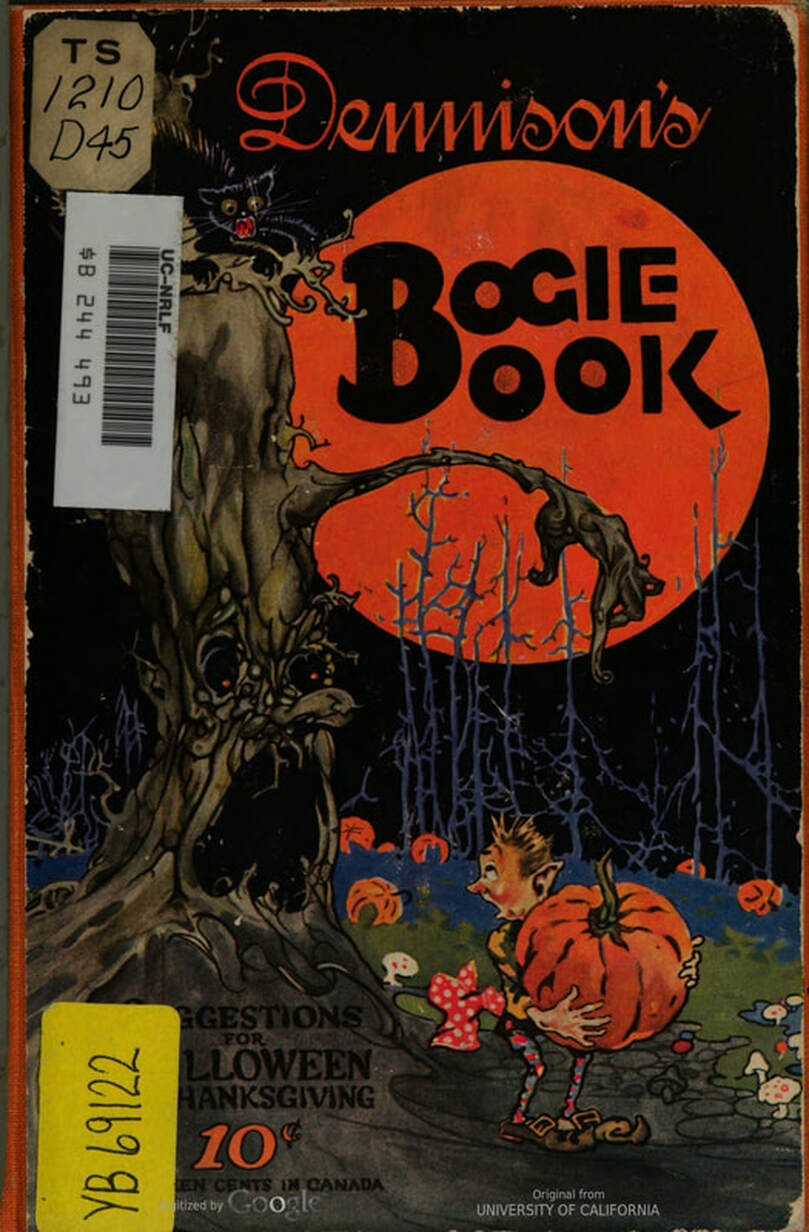

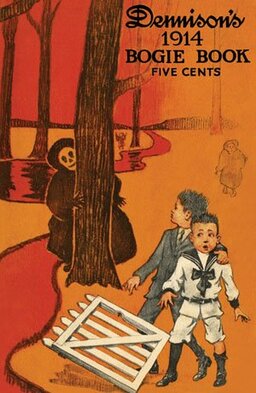

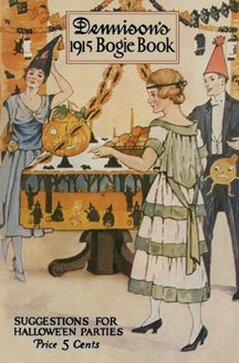

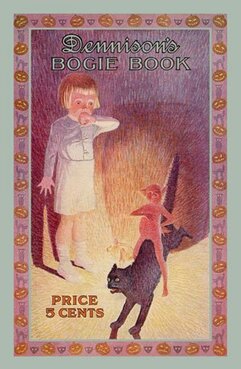

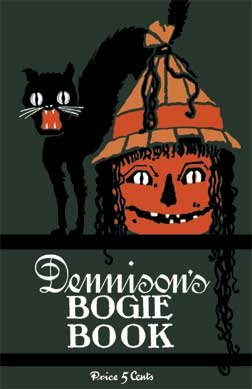

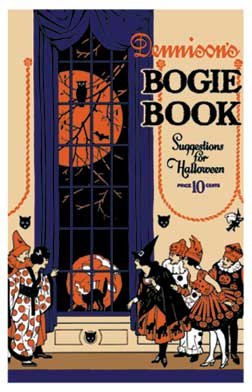

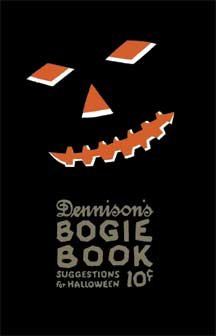

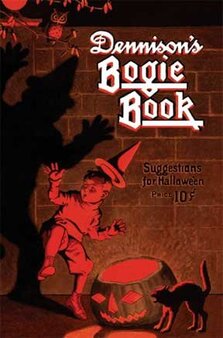

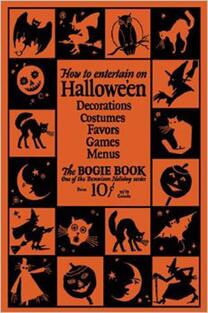

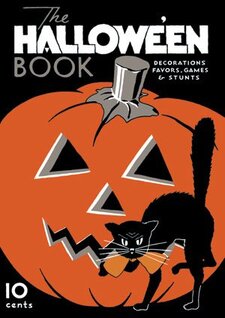

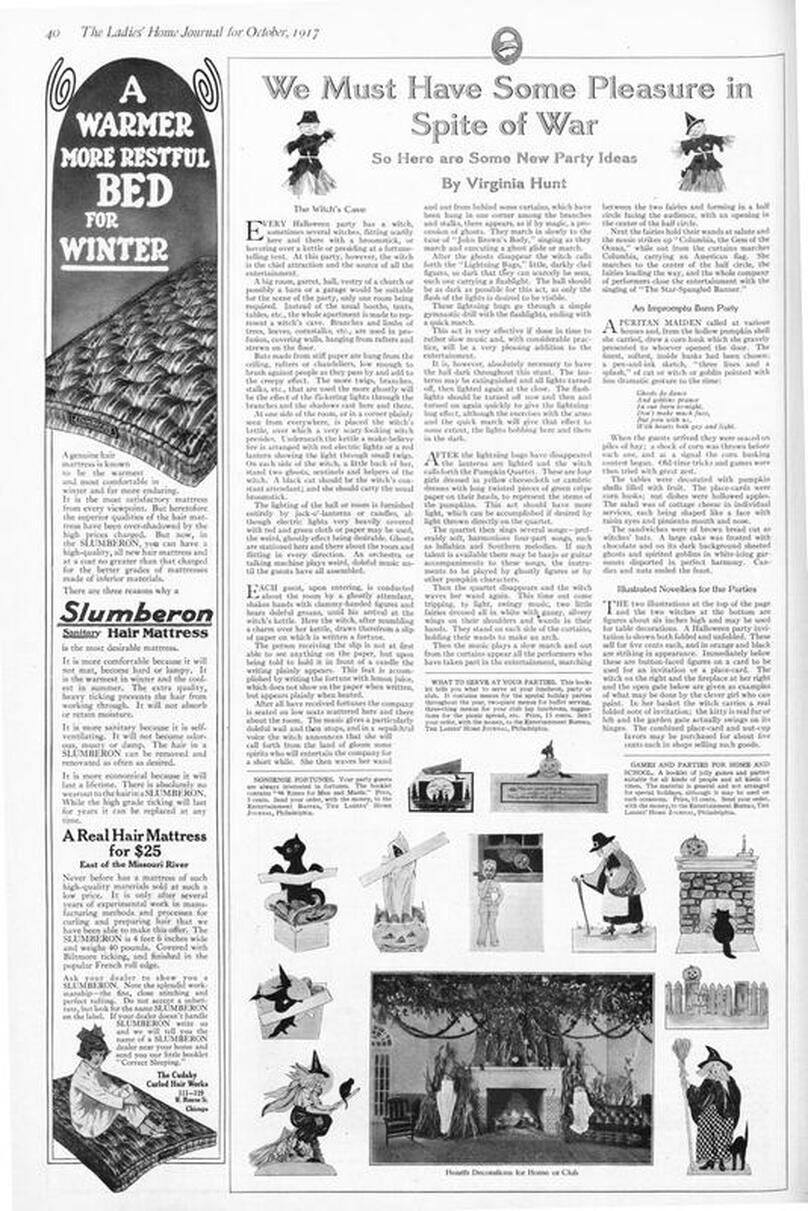

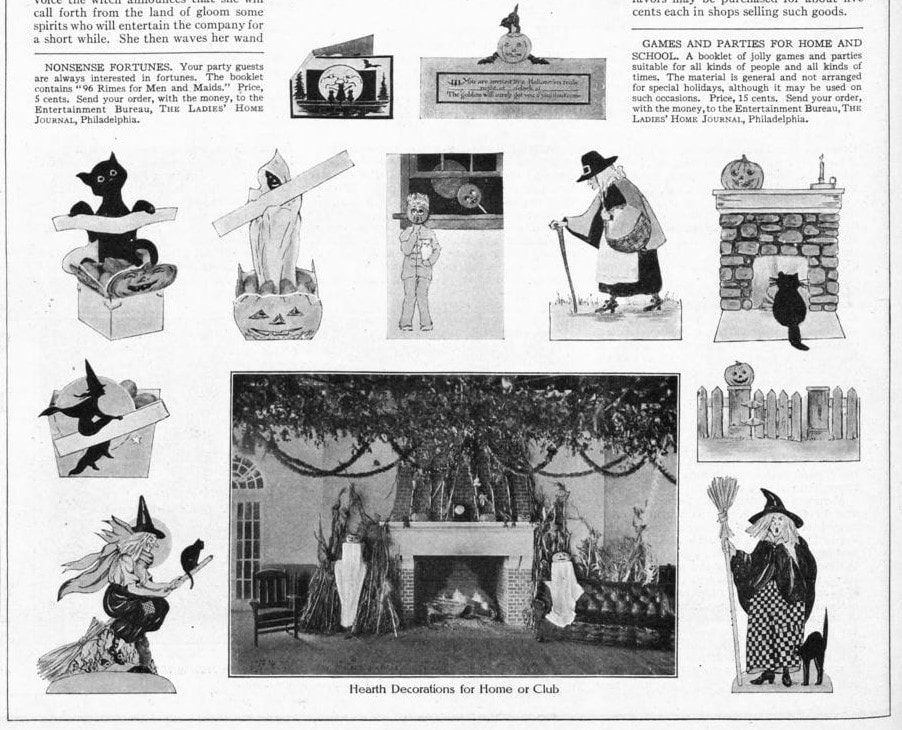

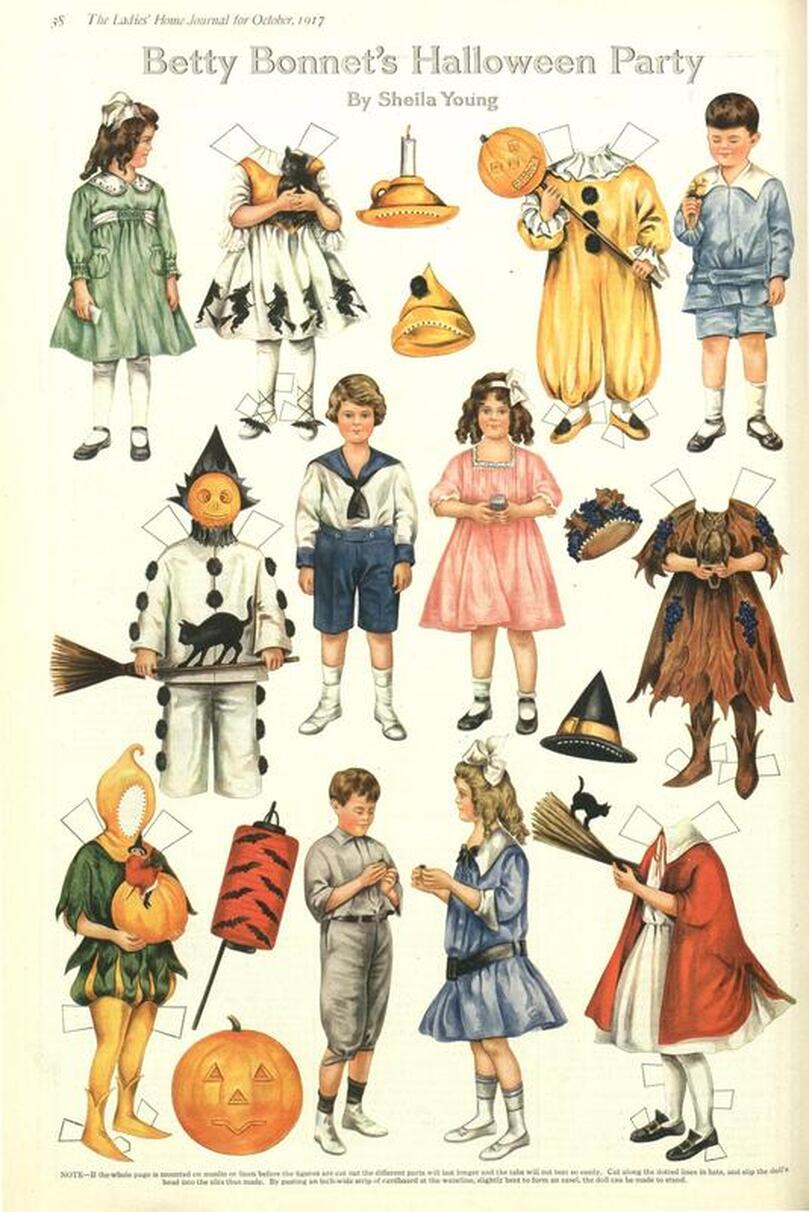

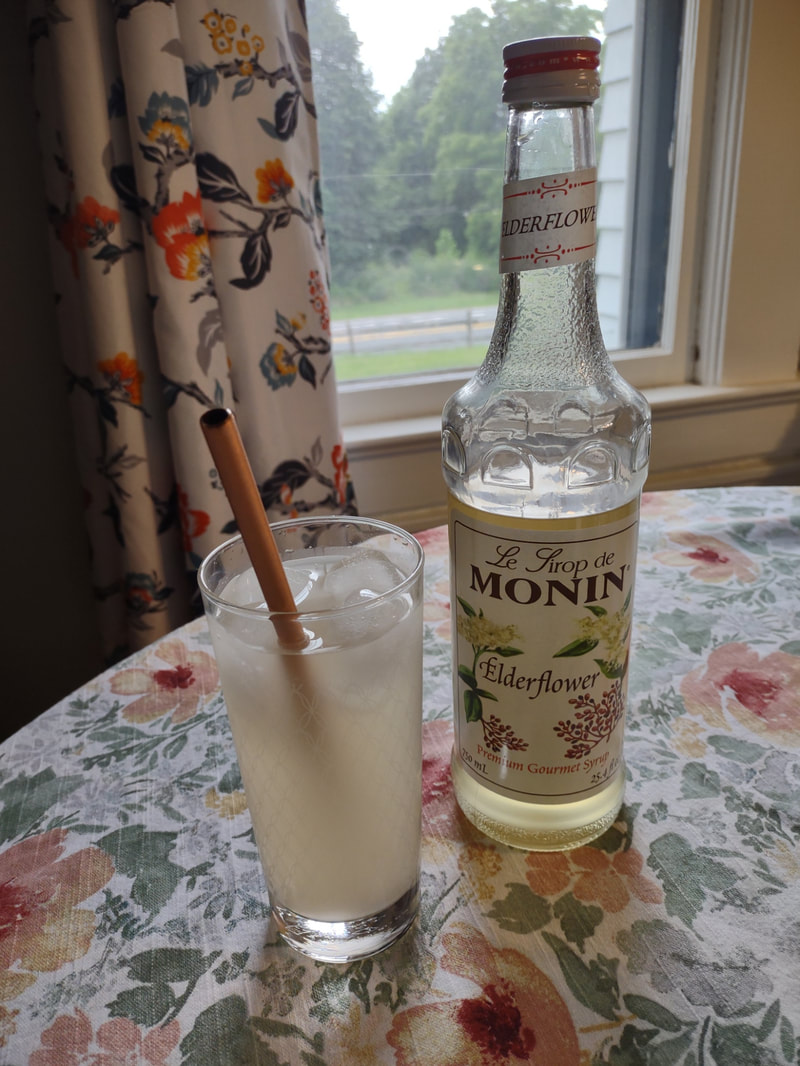

Welcome to The Food Historian's 31 Days of Halloween extravaganza. Between social media (Facebook, Instagram, Twitter) and this blog, I'll be sharing vintage Halloween content nearly every day this month! Home Halloween parties were extremely popular during the first decades of the 20th century, and although the First World War did slow some of the celebrations, it didn't entirely stop them. On October 28, 1917, the Poughkeepsie Eagle published a full-page spread celebrating Halloween. In it, "Hints for the Hallowe'en Lunch" outlined just how locals could celebrate even with voluntary restrictions on meat, butter, white flour, and sugar. The "Jack-o'-Lantern Salad" features inexpensive salt herring and potatoes, the loaf cake features just one cup of wheat flour with brown sugar and raisins for sweetener, and the "Priscilla Pop Corn" sounds very much like caramel corn! This lunch was likely intended for adult women rather than children, though young women may also have been the intended audience. A composed vegetable salad with sandwiches was typical fare for club women and other ladies who lunched. I've transcribed the whole article below for your reading pleasure. Hints for the Hallowe'en Lunch"Table decorations for a Jack'o'Lantern Jubilee must necessarily include pumpkins big and pumpkins little. Both kinds are introduced into the attractive witches cauldron of the illustration. Its value is increased when an assortment of prophecies is put into the kettle to be distributed to the guests when the strong black coffee is served. "Hallowe'en menus usually include the homely cider and doughnuts, chestnuts and apples which belong to other harvest home celebrations. "The following menu is plain and substantial and just a little different. "Jack-o'-Lantern Menu Jack-o'-Lantern Salad Brown Bread Sandwiches Fruit Loaf Cake Priscilla Pop Corn Cider or Coffee "Jack-o'-Lantern Salad "Soak salt herring in lukewarm water and drain. Cook in boiling water for fifteen minutes. When cool, separate into flakes and add an equal quantity of cold boiled potato, and one-fourth quantity of chopped, hard-boiled eggs. Mix with French dressing [ed. note: vinaigrette] and chill in refrigerator until serving time. Beat one-fourth cupful of cream until stiff and mix with it two tablespoons chopped pimentos. Mix with equal portion of mayonnaise dressing and combine with the salad. Serve on lettuce leaves, slightly flattening the heap on top to receive the "Jack-o'-Lantern," which is a small full moon face cut from a very thin slice of American cheese, the eyes marked with bits of clove, and the nose and mouth by thing strips of pimento. Brown bread sandwiches, with a filling of chopped peanuts is served with this salad. "Raised Fruit Loaf. "One cupful of butter, two cupsful brown sugar, two eggs, two cupsful of bread sponge, two teaspoonsful cinnamon, one teaspoonful clove, two teaspoonsful soda, one teasponful salt, two cupsful raisins, one cupful flour. "Cream butter and add slowly, while beating constantly sugar, then add well-beaten eggs, bread sponge, spice, soda and salt, and flour mixed and sifted, and raisins, cut in half and dredged with flour. Turn into buttered and floured oblong pans and let rise two and one-half hours and then bake for an hour. "Priscilla Popped Corn. "Two quarts of popped corn, two tablespoonsful butter, two cupsful browned sugar, one-half cupful water, one-half teaspoonful salt. Put butter in saucepan, and when melted add sugar, salt and water. Boil sixteen minutes and pour over popped corn, coating each grain thoroughly." What do you think? Would you like to attend such a lunch? I know I would! Even the herring potato salad sounds good and distinctly Scandinavian, although not particularly Halloween-ish. Priscilla popcorn, however, is definitely going on the to-make list! The Food Historian blog is supported by patrons on Patreon! Patrons help keep blog posts like this one free and available to the public. Join us for awesome members-only content like free digitized cookbooks from my personal collection, e-newsletter, and even snail mail from time to time! Don't like Patreon? Leave a tip! Welcome to The Food Historian's 31 Days of Halloween extravaganza. Between social media (Facebook, Instagram, Twitter) and this blog, I'll be sharing vintage Halloween content nearly every day this month! If you're a fan of Halloween and all things vintage, you've probably heard of Dennison's Bogie Books. Launched in 1909 by the Dennison paper products company, which specialized in crepe paper, the Bogie Books became hugely popular for their ideas for parties, costumes, and yes, menus. The idea of direct-to-consumer advertising was starting to take off in the 1900s, and certainly food companies were capitalizing on corporate cookbooklets at this time. But Dennison's was one of the first companies to issue what they called "instruction books," but which were more like idea books. Chock full of ideas for table crafts, games, costumes, decorating, party organizing, and menus, they were a one-stop shop for all things Halloween. Nearly all the ideas incorporated Dennison's products, which branched out from just black and orange crepe paper to more elaborate decorations, like printed paper tablecloths and napkins, paper plates, printed crepe paper "borders," die cut figures, and more. The popularity of Halloween parties exploded in the 1920s. Long popular among young adults looking for romance, postwar they shifted to include children and adults, too. Dennison's had been printing Art and Decoration in Crepe and Tissue Paper since 1894 (here's the 1917 edition, complete with colorful samples of crepe and tissue paper). But the 1909 Bogie Book was one of its first forays into a single holiday booklet, although others for Christmas, galas, and other holidays would follow in the 1920s. The Bogie Book, however, was the only one to be printed annually, and illustrates just how popular Halloween had become in the United States. Halloween DecorationsDennison's bread and butter was paper decorations and colored crepe paper. More than any other holiday except perhaps Christmas, decorations were an integral part of Halloween celebrations. Popularized in the late Victorian era, home Halloween parties were increasingly common in the 1910s and 1920s. Dressing up your living room (like below) and other more mundane parts of the house was crucial, and Dennison's promised loads of ideas for themes and instructions for making your own decorations, in addition to purchasing their ready-made stock. Halloween PartiesIn addition to parties at home, increasingly people were throwing more public parties. Halloween was traditionally a time for young love, and it was the perfect opportunity to get young people together. Public parties could be held in church basements, public halls, fraternal organizations, and schools. Bogie Books included hints not only in decorating these larger spaces, but also advice for spooky entrances, harmless tricks, and group games. Halloween CostumesOf course, what was a party without a costume? But Halloween costumes in the 1910s and 1920s were not much like today's. Although classic Halloween archetypes like witches, bats, pirates, pierrot and harlequin figures, and fortune tellers were popular for more obvious costumes, simply dressing in black and orange with spooky figures or motifs was enough for most people. The silhouettes of the day were largely maintained. Sometimes more abstract themes, like "Night" or "The Moon" or "A Star" might allow the fashionable young lady to put in a little more effort while still feeling pretty. In the above image, three young women feature variations on the same 1920s party dress silhouette - one is festooned with orange stripes and ribbons of crepe paper hang from her waist and festoon a hat, with jack-o'-lantern images bobbing at the ends of the streamers. Another is dressed as "The Moon" - with a large silver crescent moon on her head and a black dress and gray cape spangled with more crescent moons and stars - orange streamers hang from her waist. Another goes with a pumpkin theme - wearing an orange bodice with a dagged peplum, a black dress featuring orange jack-o'-lanterns, and long black sleeves with dagged cuffs and black ribbed cape with capelet and a huge stiff collar. Her ensemble is topped with a black cap featuring a festoon of orange leaves. A little girl is also pictured, wearing a black and orange dress featuring a black cat's face on the bodice and a black and orange cap with long ears or leaves protruding from the top. Alas, the men's costumes are less flattering - large, formless tunics and hats worn over their regular button-up shirts and ties. One is dressed as the moon - with the tunic featuring an enigmatic-looking full man-in-the-moon and a tall cone of a cap with another moon and stars. The other is dressed in a black-trimmed orange tunic featuring a large fringed black-and-orange collar and a smiling jack-o'-lantern as a pocket. He wears a witch's hat covered in small jack-'o-lanterns. Each Dennison's Bogie Book included instructions for making each of the pictured costumes from Dennison's crepe paper, printed paper figures, and more. Halloween MenusOf course, The Food Historian is going to be interested in the menus! Along with all their other suggestions, some issues of Dennison's included sample menus. Although not every Bogie Book contains menus, many do reference food and refreshments. Generally, the suggestions are simple and standard party fare - sandwiches, potato chips, potato salad, simple cakes, donuts, fruit, olives, cheese, nuts, etc. - and rarely are recipes included. The emphasis of the books is on decorating the food, tableware, and tables than the food itself. It took a while for the books to gain traction, and the 1909 one didn't get a sequel until 1912. But by then home parties for Halloween were becoming increasingly popular. And Dennison published Bogie Books annually from 1912-1935. Only war (1918) and the Great Depression (1932) stopped their publication. History of the Dennison Manufacturing CompanyThe Dennison Manufacturing Company has a long and interesting history, as it was largely controlled by one family for nearly 100 years. The Dennison company is still around today as Avery-Dennison. From the Hollis Archives, Harvard University, which holds the Dennison corporate collection: "The Dennison Manufacturing Company was a manufacturer of consumer paper products such as tags, labels, wrapping paper, crepe paper and greeting cards. The company was founded by Aaron L. Dennison and his father Andrew Dennison in Brunswick, Maine in 1844. Aaron Dennison, who was working in the Boston in the jewelry business, believed he could produce a better paper box than the imported boxes then on the market. The Dennison's first produced boxes made to house jewelry and watches. Aaron Dennison sold the boxes at his store in Boston, beginning in 1850 and in New York starting in 1854. After early business success, Aaron Dennison retired and yielded control of the company to his brother E.W. Dennison. "The mid to late 19th century saw numerous products introduced by E. W. Dennison, who improved the product so that it became the best and most sought after on the market and under the Dennison name. In order to grow the business, Dennison needed to mechanize the box making process. Dennison introduced the box machine to meet the growing demand of jewelers and watch makers, who began ordering large numbers of boxes. Until the introduction of the box machine, the boxes were still being made one at a time, by hand. The machine mechanized and sped up the box-making process. The company continued to expand, and a larger, centrally located factory was needed. Dennison chose Boston, Mass., as the site of the new factory in order to be close to the city's retail store. "In 1854, Dennison introduced card stock to hold jewelry and jewelry tags. Dennison's tags became wildly popular and the business began to expand rapidly, from the jewelry industry to textile manufacturers and retail merchants. E.W. Dennison noticed a deficiency in the quality of shipping tags and patented a paper washer that reinforced the hole in the tag. Sales of tags hit ten million in the first year. Stationery gummed labels were introduced just after the end of the Civil War. These labels had an adhesive on the back side and were manufactured to stick on boxes, crates or bags. The tag business alone required E.W. Dennison to move his factory in order to fulfill demand. The boxes, shipping tags, merchandise tags, labels and jeweler's cards were moved to the new factory in Roxbury in 1878. That same year the company was officially incorporated as the Dennison Manufacturing Company. "In just over thirty years, the company grew from a small jewelry box maker to a large manufacturer of paper products under the direction of E.W. Dennison and his partner and treasurer Albert Metcalf. Dennison died in 1886 and his son, Henry B. Dennison succeeded him as president of the company. Henry B. Dennison had worked for the company for many years, having opened the Chicago store in 1868 and served as superintendent of the factories since 1869. Henry B. Dennison served as president of the company for only six years and resigned due to poor health in 1892. Henry K. Dyer was then elected president, and under his direction the company consolidated its many factories and operations. In 1897, the Dennison Manufacturing Company purchased the Para Rubber Company plant located on the railroad line in Framingham, Mass. The box division was transferred from Brunswick, Maine; the wax and crepe paper operations from the Brooklyn, NY factory; and the labels and tags from the Roxbury plant. The move was complete in 1898 and the factory was up and running. The factory was divided into five manufacturing divisions: first, the jewelry line, which included boxes, cases, display trays; second, the consumers' line of shipping tags, gummed labels, baggage check and specialty paper items; third, the dealers' line which included all stock products sold to dealers and some consumers; fourth, the crepe paper line; and fifth, the holiday line. Also located at the Framingham plant were financial offices, advertising and marketing departments, sales division and director's offices. Although the company was divided into divisions, all aspects of the company worked together in unison to plan and execute the production, marketing, and sale of a product. The Dennison Mfg. Co. planned well in advance of any sale by conducting market research, reviewing past statistics and gauging future interest in products. "Henry Sturgis Dennison, grandson of the founder, began working for the family business after graduating from Harvard in 1899. He held various jobs at the company including foreman of the wax department and in the factory office. He was promoted to works-manager in 1906, director in 1909 and treasurer in 1912. In 1917, H.S. Dennison was elected president of the company. While serving as president of the company, H.S. Dennison oversaw the international expansion of the firm, consolidation and streamlining of certain processes and procedures, reduction in working hours, implementation of employee profit sharing plans, an unemployment fund and the creation of company wellness facilities. H.S. Dennison was heavily focused on getting the highest quality work out of each of his employees and eagerly sought their advice and suggestions for improving working conditions and manufacturing processes. He employed market analysis and research when venturing into a new sales territory or rolling out a new product. His focus on industrial management led him to be a prolific writer, speaker, and expert advisor on the topic. Outside of his management of the company, he served as an advisor to the administrations of Woodrow Wilson and Franklin Roosevelt and lectured at Harvard Business School. Henry Sturgis Dennison served as president of the Dennison Manufacturing Company until his death in 1952. "Dennison's long time director of research and vice president, John S. Keir, was elected to succeed him in 1952. Keir only served for a short time, and continued running the company the way Dennison would have. After World War II, an emphasis was placed on manufacturing products that appealed to women, especially housewives. New products included photo corners, picture hangers, stationery, scotch tape, diaper liners and school supply materials for children. During the 1960s and 1970s, the Dennison Manufacturing Company began actively researching new products and proposed acquiring small, competing office product companies with new technologies. This effort was undertaken by president Nelson S. Gifford in order to diversify Dennison's product line, maximize profits for shareholders, and keep the company fresh. In 1975, Dennison acquired the Carter's Ink Company, a Boston, Mass. based manufacturer of ink and writing utensils. This acquisition and others broadened Dennison's product line as the company moved away from paper manufacture to a manufacturer of all office products. "Dennison Manufacturing Company merged with Avery Products in 1990 to become, Avery-Dennison, a global manufacturer of pressure sensitive adhesive labels and packaging materials solutions." If you'd like to learn more about Dennison, check out the Harvard collection. For more about the history of the family and its products, check out this historical overview from the Framingham, Massachusetts History Center, which holds the Dennison family papers and other collections related to the company. Finding Dennison's Bogie BooksThe Bogie Books can be hard to find these days. They are collector's items and sadly often disappear from library and archival collections. However, several issues from the 1920s have been digitized and are available for free on disparate locations around the internet. I've collected them here for your viewing and reading pleasure. If you'd like to see the covers for 1912-1925, check out the list at Vintage Halloween Collector. Dennison's Bogie Book - 1919 edition Dennison's Bogie Book - 1920 edition Dennison's Bogie Book - 1922 edition Dennison's Bogie Book - 1923 edition Dennison's Bogie Book - 1924 edition Dennison's Bogie Book - 1925 edition Dennison's Bogie Book - 1926 edition Dennison's has also reproduced many of its historic Bogie Books and they are available for sale as print copies. You can find them on Amazon by clicking the links below. If you purchase anything from the links, you'll help support The Food Historian! What do you think? Are you inspired to try some vintage decorations for your Halloween party this year? In 2019 I threw my own version of A Very Vintage Halloween party - check it out! The Food Historian blog is supported by patrons on Patreon! Patrons help keep blog posts like this one free and available to the public. Join us for awesome members-only content like free digitized cookbooks from my personal collection, e-newsletter, and even snail mail from time to time! Don't like Patreon? Leave a tip! Welcome to The Food Historian's 31 Days of Halloween extravaganza. Between social media (Facebook, Instagram, Twitter) and this blog, I'll be sharing vintage Halloween content nearly every day this month! References to Halloween during the First World War were few and far between but this little article caught my eye. Featured in the October, 1917 edition of the Ladies Home Journal, "We Must Have Some Pleasure in Spite of the War" by Virginia Hunt doesn't have much in the way of menu suggestions and recipes, but it does illustrate the typical ideas around Halloween parties at the time. A mixture of an excuse for teenaged romance, a little spookiness, and of course, the home economist's dream of a color-coordinated, crafty, event, sometimes with coordinated gymnastics. For fun, I've transcribed the original article verbatim below. Would you host a Halloween party with any of this advice?  Orange postcard featuring two witches adding ingredients to a cauldron - two smiling jack-o'-lanterns look on. Below reads, "Halloween Greetings - When the witches in their kettles Stir their magic brew tonight,-- May they bring forth things you long for -- May they cast your future bright!" Postcard c. 1920, Enoch Pratt Collection, Maryland Digital Collections. The Witch's Cave Every Halloween party has a witch, sometimes several witches, flitting scarily here and there with abroomstick, or hovering over a kettle or presiding at a fortune-telling tent. At this part, however, the witch is the chief attraction and the source of all the entertainment. A big room, garret, hall, vestry of a church or possibly a barn or a garage would be suitable for the scene of the party, only one room being required. Instead of the usual booths, tents, tables, etc., the whole apartment is made to represent a witch's cave. Branches and limbs of trees, leaves, cornstalks, etc., are used in profusion, covering walls, hanging from rafters and strewn on the floor. Bats made from stiff paper are hung from the ceiling, rafters or chandeliers, low enough to brush against people as they pass by and add to the creepy effect. The more twigs, branches, stalks, etc., that are used the more ghostly will be the effect of the flickering lights through the branches and the shadows cast here and there. At one side of the room, or in a corner plainly seen from everywhere, is placed the witch's kettle, over which a very scary-looking witch presides. Underneath the kettle a make-believe fire is arranged with red electric lights or a red lantern showing the light through small twigs. On each side of the witch, a little back of her, stand two ghosts, sentinels and helpers of the witch. A black cat should be the witch's constant attendant; and she should carry the usual broomstick. The lighting of the hall or room is furnished entirely by jack-o'-lanterns or candles, although electric lights very heavily covered with red and green cloth or paper may be used, the weird ghostly effect being desirable. Ghosts are stationed here and there about the room and flitting in every direction. An orchestra or talking machine plays weird, doleful music until the guests have all assembled. Each guest, upon entering, is conducted about the room by a ghostly attendant, shakes hands with clammy-handed figures and hears doleful groans, until his arrival at the witch's kettle. Here the witch, after mumbling a charm over her kettle, draws therefrom a slip of paper on which is written a fortune. The person receiving the slip is not at first able to see anything on the paper, but upon being told to hold it in front of a candle the writing plainly appears. This feat is accomplished by writing the fortune with lemon juice, which does not show on the paper when written, but appears plainly when heated. After all have received fortunes the company is seated on low seats scattered here and there about the room. The music gives a particularly doleful wail and then stops, and in a sepulchral voice the witch announces that she will call forth from the land of gloom some spirits who will entertain the company for a short while. She then waves her wand and out from behind some curtains, which have been hung in one corner among the branches and stalks, there appears, as ifby magic, a procession of ghosts. They march in slowly to the tune of "John Brown's Body," singing as they march and executing a ghost slide or march. After the ghosts disappear the witch calls forth the "Lightning Bugs," little, darkly clad figures, so dark that they can scarcely be seen, each one carrying a flashlight. The hall should be as dark as possible for this act, as only the flash of the lights is desired to be visible. These lightning bugs go through a simple gymnastic drill with the flashlights, ending with a quick march. This act is very effective if done in time to rather slow music and, with considerable practice, will be a very pleasing addition to the entertainment. It is, however, absolutely necessary to have the hall dark throughout this stunt. The lanterns may be extinguished and all lights turned off, then lighted again at the close. The flashlights should be turned off now and then and turned on again quickly to give the lightning-but effect, although the exercises with the arms and the quick march will give that effect to some extent, the lights bobbing here and there in the dark. After the lightning buts have disappeared the lanterns are lighted and the witch calls forth the Pumpkin Quartet. These are four girls dressed in yellow cheesecloth or cambric dresses with long twisted pieces of green crepe paper on their heads, to represent the stems of the pumpkins. This act should have more light, which can be accomplished if desired by light thrown directly on the quartet. The quartet then sings several songs - preferably soft, harmonious four-part songs, such as lullabies and Southern melodies. If such talent is available there may be banjo or guitar accompaniments to these songs, the instruments to be played by ghostly figures or by other pumpkin characters. Then the quartet disappears and the witch waves her wand again. This time out come tripping, to light, swingy music, two little fairies dressed all in white with gauzy, silvery wings on their shoulders and wands in their hands. They stand on each side of the curtains, holding their wands to make an arch. Then the music plays a slow march and out from the curtains appear all the performers who have taken part in the entertainment, marching between the two fairies and forming in a half circle facing the audience, with an opening in the center of the half circle. Next the fairies hold their wands at salute and the music strikes up "Columbia, the Gem of the Ocean," while out from the curtains marches Columbia, carrying an American flag. She marches to the center of the half circle, the fairies leading the way, and the whole company of performers close the entertainment with the singing of "The Star-Spangled Banner." An Impromptu Barn Party A Puritan maiden called at various houses and, from a hollow pumpkin shell she carried, drew a corn husk which she gravely presented to whoever opened the door. The finest, softest, inside husks had been chosen; a pen-and-ink sketch, "three lines and a splash," of cat or witch or goblin pointed with fine dramatic gesture to the rime: Ghosts do dance And goblins prance In our barn to-night. Don't make much fuss, But join with us, With hearts both gay and light. When the guests arrived they were seated on piles of hay; a shock of corn was thrown before each one, and at a signal the corn husking contest began. Old-time tricks and games were then tried with great zest. The tables were decorated with pumpkin shells filled with fruit. The place-cards were corn husks; nut dishes were hollowed apples. The salad was of cottage cheese in individual services, each being shaped like a face with raisin eyes and pimiento mouth and nose. The sandwiches were of brown bread cut as witches' hats. A large cake was frosted with chocolate and on its dark background sheeted ghosts and spirited goblins in white-icing garments disported in perfect harmony. Candies and nuts ended the feast. Illustrated Novelties for the Parties The two illustrations at the top of the page and the two witches at the bottom are figures about six inches high and may be used for table decorations. A Halloween part invitation is shown both folded and unfolded. These sell for five cents each, and in orange and black are striking in appearance. Immediately below these are button-faced figures on a card to be used for an invitation or a place-card. The witch on the right and the fireplace at her right and the open gate below are given as examples of what may be done by the clever girl who can paint. In her basket the witch carries a real folded note of invitation; the kitty is real fur or felt and the garden gate actually swings on its hinges. The combined place-card and nut-cup favors may be purchased for about five cents each in shops selling such goods. Well! The Witch's Party certainly seems like it would be a LOT of work to organize and put on, requiring quite a few actors. The patriotic ending featuring Columbia, while seemingly out of place among a Halloween production, was typical of the period and boosterism for the war effort. That being said, the adorable barn party seems much more doable, provided one can find corn for husking! What do you think? Would you add any of these ideas to YOUR Halloween party? And here's a little bonus - a fun page of paper dolls from that same issue of the Ladies' Home Journal! Which costume would you wear? The Food Historian blog is supported by patrons on Patreon! Patrons help keep blog posts like this one free and available to the public. Join us for awesome members-only content like free digitized cookbooks from my personal collection, e-newsletter, and even snail mail from time to time! Don't like Patreon? Leave a tip! I used to hate gin and tonics. "Bitter, bitter pine trees" I called it (incidentally, somebody please make that their band name). But while plain dry gin and regular tonic are still not my thing, I've become a much bigger fan of gin than I originally thought. In particular, flavored gins, which are so easy to make at home! Rhubarb is a favorite in Northern Europe and Scandinavia is no exception. But ultimately rhubarb reminds me of growing up in North Dakota! Also known as "pie plant," the only safe part of the rhubarb plant for humans to eat is the stalk. It gets its sourness from oxalic acid, which is concentrated in the leaves, making them inedible and toxic. But its tartness is part of its charm, as rhubarb is often one of the earliest "fruits" available after winter. Although rhubarb is done for the season in much of the United States by July, I was able to rescue some stalks from my mother-in-law's house before they got too dry. June was a busy month for me, so I didn't have much time to turn them into desserts. Gin it was! Rhubarb Gin & TonicThis recipe is pretty straightforward, and makes the most delicious, rhubarb-y gin! 10-16 rhubarb stalks sugar to coat dry gin tonic water Cut the rhubarb lengthwise into long strips, then cut crosswise into small pieces. Essentially, you want it minced. Add it to a quart jar (about 3 cups) and add sugar to coat, a 1/4 to a half cup. Seal and shake vigorously and let rest at room temperature, shaking occasionally, until the rhubarb gives up its juice. After 12-24 hours, cover with dry gin (I used the tail end of a bottle of Beefeater). Shake well and let rest at room temperature, shaking occasionally, for a day or two before using. The pinker your rhubarb, the pinker the gin. Eventually, the minced rhubarb will lose its color, but it will still taste delicious. To make the beautiful pink gin into a tonic, pour a finger or two over ice, fill with tonic water, and stir to chill and combine. You don't have to use particularly high-quality gin - the sugar smooths out a lot of the alcoholic burn. But try to use a higher quality tonic than the garden variety. I like Fever Tree. Use the plain tonic for full rhubarb flavor. But if you're feeling extra fancy and adventurous, try it with their Elderflower tonic! The flavor of the rhubarb and the elderflower merge to give almost a grapefruit-y taste. I like both ways! Purchases from affiliate links will give The Food Historian a small commission. Infusing alcohol is one of my favorite ways to "preserve" fruit, and gin is one of the most forgiving. You can make blackberry gin, raspberry gin, and even celery gin! Just add fruit, a little sugar if you want, and let it rest until the gin takes on the color and flavor of whatever you're putting in it. This is the last post in my Scandinavian Midsummer Porch Party series. I hope you enjoyed it! Follow the link to see the whole menu. The Food Historian blog is supported by patrons on Patreon! Patrons help keep blog posts like this one free and available to the public. Join us for awesome members-only content like free digitized cookbooks from my personal collection, e-newsletter, and even snail mail from time to time! Don't like Patreon? Leave a tip! Every good party has at least two beverage options for guests. I like to have one alcoholic, and one non-alcoholic. When I was planning my Scandinavian Midsummer Porch Party, I knew I wanted something light and refreshing for the non-alcoholic option. Scandinavians aren't really known for this, but saft is a non-alcoholic fruit juice concentrate that often finds its way onto Scandinavian tables. Saft means "juice" and is a sugar-sweetened concentrate meant to be mixed with water. In a lot of households, water and the concentrate are placed on the table separately, and guests mix their own beverages to taste. Saft isn't quite a syrup. Legally, it must contain at least 9% fruit juice. But it's certainly not unsweetened. Historically, the sugar likely acted as a preservative, allowing people to have fruity drinks year-round and preserve some of the summer abundance for the lean times in winter. Access to vitamin C may have also played a role in the creation of saft. Analogs in the United States might be shrub (although that is often made with vinegar) and British cordial (although that is sometimes fortified by alcohol). If you've even been to IKEA and had the lingonberry "juice" at the café, you've had saft. Common flavors include strawberry, blackberry, blackcurrant, lingonberry, and elderflower. ElderFLOWER? Yep! Elderflower! Elder plants are common in Europe and have been revered in many ancient cultures for their magical and protective powers. You may have heard that elderberry syrup can be use as an immune booster. But elderflowers were also eaten in early summer. Fried as fritters, made into saft and cordials, steeped in alcohol, and eaten with fish, their strong floral scent has an affinity for honey, lemon, and gooseberries. Although elders grow with abundance in Europe, they're a bit more scarce here in the United States. So I did not make my own elderflower syrup, but if you've got access and care to take a stab, here's a recipe to try. If you also live in an area that's short on elder bushes and trees, you can purchase syrups online or from your local IKEA or Scandinavian shop. I got Monin brand syrup, which was good (I like all their syrups), but not as good as the "real" Swedish saft, which is hard to find online. Hafi brand elderflower drink concentrate is what to Google, and Hafi is a Swedish preserves brand that has been around since the 1930s. You can find it in some specialty foods stores, too. Elderflower PunchThis elderflower punch is delicious, but it has a unique flavor. Some of my party-goers thought it tasted like Pez! I think it's a nice combination and refreshing, but see for yourself. elderflower syrup plain seltzer or club soda ginger ale In each glass, add about an inch of syrup, then fill halfway with plain seltzer, top off with ginger ale, and give it a good stir to combine the syrup. You can also do it with all plain seltzer, but then it's elderflower soda! If you're making it for a crowd, the ratio is about a quarter cup of syrup to one cup each seltzer and ginger ale. The Food Historian blog is supported by patrons on Patreon! Patrons help keep blog posts like this one free and available to the public. Join us for awesome members-only content like free digitized cookbooks from my personal collection, e-newsletter, and even snail mail from time to time! Don't like Patreon? Leave a tip! I can take zero credit for coming up with this genius recipe. That 100% goes to Nevada and her North Wild Kitchen, which is where I first found her recipe for rømmegrøt ice cream. You may be asking yourself, what on earth is rømmegrøt? Rømmegrøt is a traditional Norwegian porridge made from flour and heavy cream, usually served with cinnamon and sugar at Christmastime. The term rømmegrøt means "sour cream porridge," and in Norway the traditional recipe often calls for a mixture of sour cream and milk. But for whatever reason, here in the States, it is almost exclusively made with plain heavy cream. Interestingly, as far as I can tell, the taste is not particularly different, because this ice cream is made with sour cream and it tastes exactly like the rømmegrøt I grew up eating. (If you're interested in the original rømmegrøt, check out my patrons-only post on Patreon, complete with a recipe!) The "real" rømmegrøt is incredibly rich. The flour makes for a smooth, creamy pudding-like texture and as it cooks with the heavy cream it "splits" and "makes" its own melted butter sauce as the flour binds to the dairy proteins in the heavy cream. Historically its richness made it the perfect food for winter holidays, which is why it is so often associated with Christmas. This is also perhaps why soured cream was used, instead of fresh. Cows generally stop producing milk once their offspring are weaned, so winter is the time a lot of cows would "dry up" until they got pregnant again. If a family only had one cow, it would be impossible to get fresh dairy year-round. Rømmegrøt is also a traditional dish for new mothers - the rich but easily digested food helped them recover from the trauma of childbirth, and ensured they got enough calories to keep their babies well-fed. But while this food is, indeed, delicious, eating a rich, stick-to-your-ribs dish in the summer heat is not exactly appealing. Enter the genius rømmegrøt ice cream. Any purchases from links below will result in a small commission for The Food Historian. Rømmegrøt Ice CreamI'm giving you this recipe because although Nevada's North Wild Kitchen recipe is marvelous, I tweaked hers just a little. Fair warning that you will need an ice cream maker for this one. (We got this one as a wedding present and love it.) 12 ounces full fat dairy sour cream (1/2 of a 24 ounce carton) 1 1/2 cups heavy cream 3/4 cup granulated sugar 1/2 teaspoon ground cinnamon In a pourable container, mix all ingredients and whisk well to combine (you could stop at this point and just eat the pourable mix with a spoon, and I always lick the bowl). Pour into the ice cream maker and start. When the ice cream is no longer turning over in the maker, it's pretty much done. You can pack it into a freezer container (these are nice) or serve immediately. Rømmegrøt ice cream has a tangy sweet flavor and including the cinnamon in the ice cream makes all the difference, for me. You can eat it on its own, but it also pairs well with apple pie or crisp, blueberry, blackberry, rhubarb, or strawberry desserts, and gingerbread. I had originally intended to make a big strawberry rhubarb crisp for the party to go with this ice cream, but ran out of time. And since I made two batches of rømmegrøt ice cream in advance, it almost got forgotten altogether! I pulled it out last minute for anyone who had room for a little more dessert. While everyone enjoyed it, I think I was the only one who had ever tasted rømmegrøt before, so perhaps it's slightly less of a delight without the taste memories to work with. I guess this just means I'll have to throw a Scandinavian Christmas party to introduce everyone to the joys of original rømmegrøt! The Food Historian blog is supported by patrons on Patreon! Patrons help keep blog posts like this one free and available to the public. Join us for awesome members-only content like free digitized cookbooks from my personal collection, e-newsletter, and even snail mail from time to time! Don't like Patreon? Leave a tip! |

AuthorSarah Wassberg Johnson has an MA in Public History from the University at Albany and studies early 20th century food history. Archives

July 2024

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed