|

Thanks to everyone who joined me on Friday for Food History Happy Hour live on Facebook. This week we discussed the role of riots and boycotts in history and food history, touching primarily on the food boycotts and riots and high cost of living protests of 1916/1917 which occurred around the globe. We also talked about women's suffrage and farmerettes, midnight suppers, Frank Meier, inventor of the bees' knees cocktail and his role in WWII, poison candy and the Pure Food and Drug Act of 1906, food and riots or protests, including the role of food and cooking in the Civil Rights movement, Laura Ingalls Wilder and the Little House Cookbook, L. M. Montgomery, requests for next week, and a brief introduction to the history of gelatin, beaten biscuits, and other formerly upper-crust foods which became inexpensive convenience foods. If you want to watch back episodes you can check them out on right here on the blog or I am hoping to upload full episodes to YouTube now that my channel is officially verified! Bees' Knees Cocktail (1936)In 1936 Frank Meier published "The Artistry of Mixing Drinks," a beautifully designed little bartender's guide based on his time as the head bartender at the Hotel Ritz Carlton's Cafe Parisian, which opened in 1921. Frank had purportedly trained at the Hoffman House in New York City before taking on his new role at the Ritz. He served as head bartender and host for over twenty years and even played a role in the French Resistance during WWII, when the Ritz became German headquarters. Meier was a well-known originator of cocktails, including the famous "Bees' Knees," which he invented sometime in the 1920s. It became popular in the United States during Prohibition, likely because the honey and lemon masked the taste of bathtub gin. Frank's original recipe reads: "In shaker: the juice of one-quarter Lemon, a teaspoon of Honey, one-half glass of Gin, shake well and serve." A more modern recipe might be: Juice of 1/4 lemon (or half a tablespoon) 1 or 2 teaspoons of honey 1 or 1 1/2 ounce gin Shake over ice and serve in a cocktail glass. One teaspoon of honey definitely wasn't enough for me - I couldn't taste the honey at all! Perhaps "a dollop" might be a better descriptor. Here are some resources on some of the topics we discussed tonight:

Next week we'll be discussing Easy Bake Ovens, Jello and aspic, foods of the 1950s and '60s, and all sorts of other fun stuff. See you then! If you liked this post and would like to support more Food History Happy Hour livestreams, please consider becoming a member or joining us on Patreon. Members and patrons get special perks like access to members-only content.

0 Comments

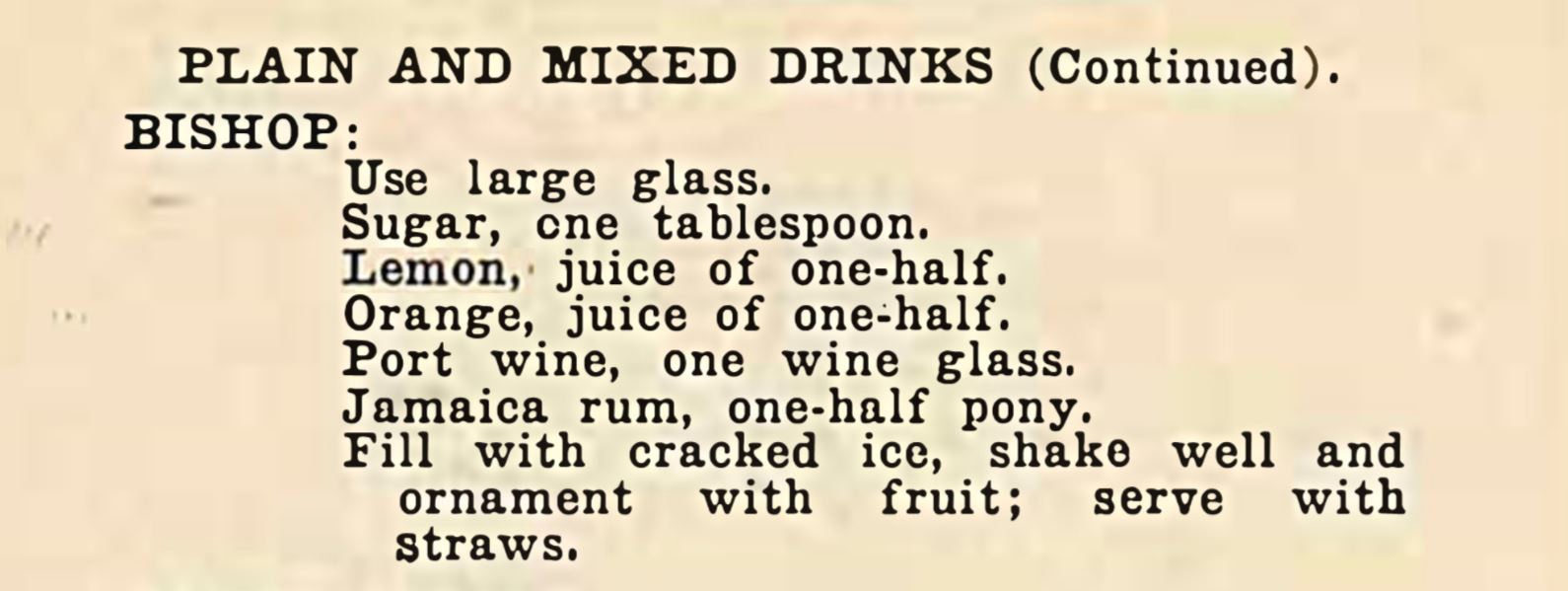

Thanks to everyone who joined me on Friday for Food History Happy Hour live on Facebook. This week, in commemoration of Memorial Day, we talked about its Civil War origins, the history of grave decoration as Decoration Day, cemetery picnics (and picnics in general), history of refrigeration, how food was preserved before refrigeration, including canning, with mention of my book review of Canned, a discussion of fireless cookers/hay boxes, including Sabbath cooking, historical spring (spoiler alert: June used to be spring), book update, including WWI New York City soldiers' canteens, agricultural labor shortages, comparisons between WWI and the coronavirus pandemic, and what I've been reading recently. Bishop Cocktail (1906)I've been looking for a port wine cocktail for a while so that I could crack open my new bottle of Brotherhood Winery's Ruby Port, which is delightful. And, as Anna Katherine pointed out, Friday was Drink Local Wine Night! And Brotherhood Winery - the oldest winery in the country - is located just a few miles from my house. As I mentioned in the video, the Bishop cocktail (notice that the Black Stripe is the very next recipe!) ended up tasting very similar to sangria, which is not a bad thing. But I would definitely cut down on the sugar next time. And having looked it up since the show, Jamaican rum is a dark rum - not at all close to the white Puerto Rican rum I was using. But in a global pandemic, you use what you've got! This cocktail comes from the 1906 How to Mix Drinks: Compiled, Selected, and Concocted by George Spaulding. Here's the original version, with my notes: Use large glass. Sugar, one tablespoons [try one teaspoon instead] Lemon, juice of one-half [or 1 tablespoon bottled] Orange, juice of one-half [or 2 tablespoons bottled] Port wine, one wine glass [ooops! I did a half, you can too] Jamaica rum, one-half pony [1/2 oz.] Fill with cracked ice, shake well and ornament with fruit [I used blood orange]; serve with straws. If you liked this post and would like to support more Food History Happy Hour livestreams, please consider becoming a member or joining us on Patreon. Members and patrons get special perks like access to members-only content.

Once again the wheels of publishing grind slowly, but I'm pleased as punch to see one of my book reviews in print again, this time in the Spring 2020 edition of the Agricultural History Journal. Canned: The Rise and Fall of Consumer Confidence in the American Food Industry. By Anna Zeide. Oakland: University of California Press, 2018. 269 pp., $34.95, hardcover, ISBN 9780520290686. Few people these days haven’t tasted canned food, but have you ever considered its origins? Tin cans versus glass jars? The science of safe canning? Anna Zeide did in her new book Canned: The Rise and Fall of Consumer Confidence in the American Food Industry. Tracking the rise of commercially canned foods in America from the condensed milk of the Civil War to modern concerns about bisphenol-A (BPA), Zeide puts canned goods firmly in historical context – connecting them to changes in technology, agricultural science, medicine, politics, and social changes. On the surface, the book is about the safety of canned goods; Zeide studies the roles of lead poisoning, spoilage, botulism, mercury in canned fish, and the 21st century issue of bisphenol-A (BPA) contamination in shaping consumer use of and confidence in canned goods. The chapters are arranged as case studies and are outlined in chronological order. The introduction outlines the history of canning technology (and safety) before moving on to condensed milk in the post-Civil War era and the rise of chemical additives and improvements in canning technology. The chapter on canned peas in the 1910s discusses the relationship between canners, agricultural research, and vertical integration of farming with vegetable varieties bred to be canned, embracing agricultural grading. The chapter on canned ripe olives addresses the threat of botulism in the 1920s, and how the canning industry resisted regulation and attempted to place the blame on careless home canners. The chapter on canned tomatoes in the 1930s outlines how canners resisted grading of canned goods, even as they embraced it for their own suppliers, and attempted to read the mind of “Mrs. Consumer,” now an economic force to be reckoned with. The chapter canned tuna and mercury contamination in the 1970s chronicles the rise of processed food more broadly, the expansion of canners beyond canned food, and the backlash against artificial ingredients, pesticides, and other contaminants in canned goods and industrial food. Finally, Zeide ends with a discussion of consumer fears about BPA in Campbell’s canned soups in the 2010s, and Campbell’s attempts to cover up health concerns even as it tried to appeal to a new, food-savvy generation of consumers. As you can probably tell, beneath the study of the relationship between consumers and food processors is the real meat of the book – on regulation of the industry. At first, early canners were happy to work with government regulators to prove themselves worthy in a crowded and competitive market. And access to agricultural colleges for crop research and federal food safety research were benefits they were only too happy to embrace. But as food processors consolidated and the 20th century wore on, canners became increasingly resistant to government regulation, oversight, and transparency. So much so that by the 2010s when Campbell’s Soup was confronted with consumer concerns about the endocrine disrupting BPA, they closed ranks and denied any safety concerns. But, despite promises to end the use of BPA in can liners and even as it hopped on other bandwagons such as the labeling of genetically modified foods, as of 2016 Campbell’s had yet to replace BPA in their cans. Zeide concludes the book by outlining why government regulation and collective action is more effective in maintaining food safety than the industry’s beloved individual action. Throughout the book, food processors claim that “Mrs. Consumer” can choose for herself which brands are the safest and highest quality, but that ignores circumstances beyond consumer control, such as the case study Zeide cites in which consumers fed on a diet devoid of canned goods and full of locally produced whole foods actually saw their BPA levels increase, likely due to the use of BPA in plastics used as part of the even minimal food processing, such as in the milking industry or in the production of spices in other countries (p. 183). Ultimately, Zeide tries to place canned goods briefly in context in the conclusion – that access to canned fruits and vegetables gave a whole subset of Americans access to nutrients they might not have had access to before, and that emotional responses to the foods of our childhoods will give canned goods longevity. Although at various places throughout the book Zeide makes mention of potential class issues surrounding canned goods, and the assumptions of canners that “Mrs. Consumer” was white and middle class, a more thorough examination of class and race in the context of canned goods would have made this book even stronger, especially considering the emphasis on consumer marketing. However, despite this omission, Canned is ultimately a strong addition to food historiography and I applaud Zeide for her detailed work and her ability to place events and people in context, drawing connections and conclusions that are well supported by her research. If you enjoyed this book review, please consider becoming a member or joining us on Patreon. Members and patrons get special perks like access to members-only content and discounts on programs and classes.

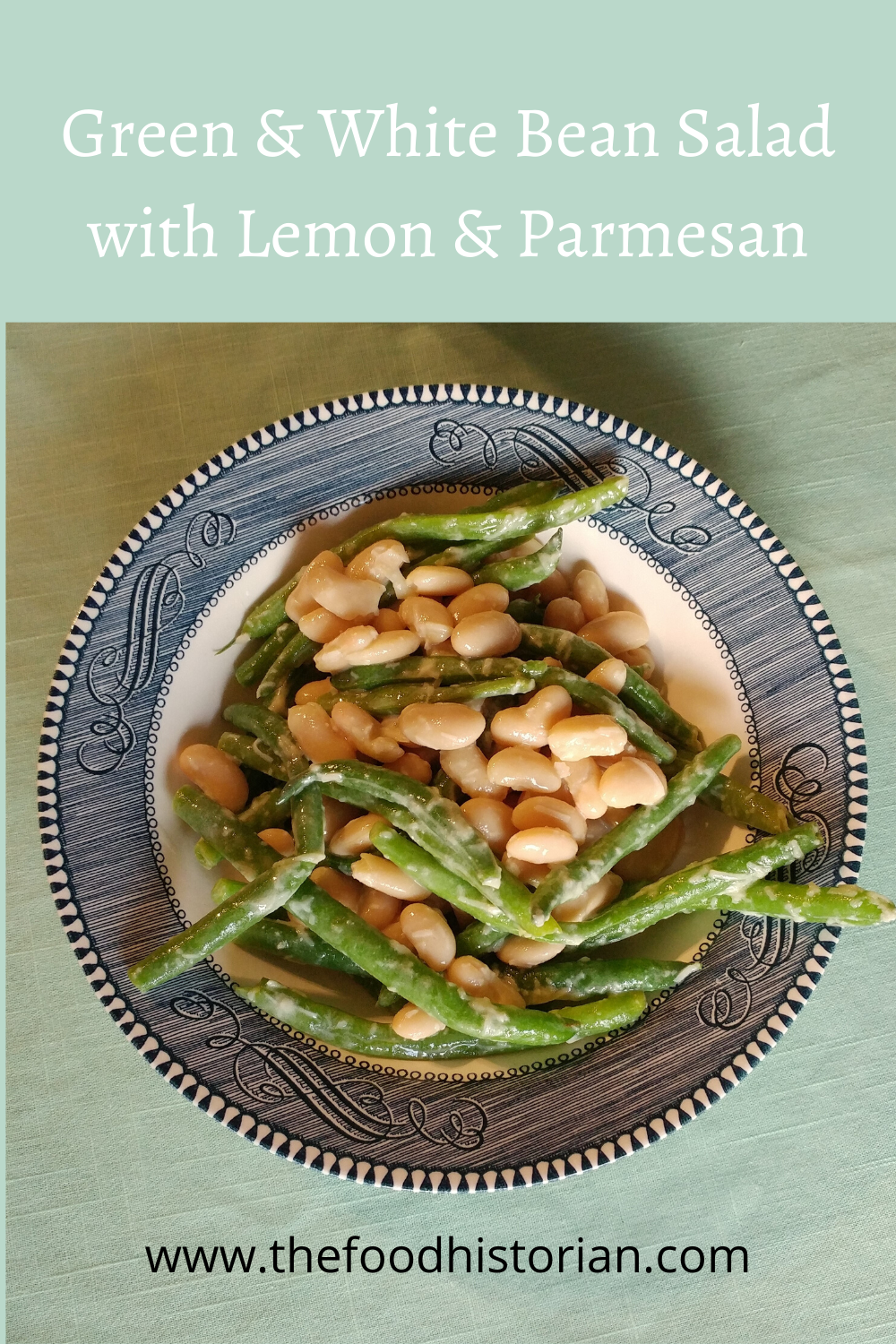

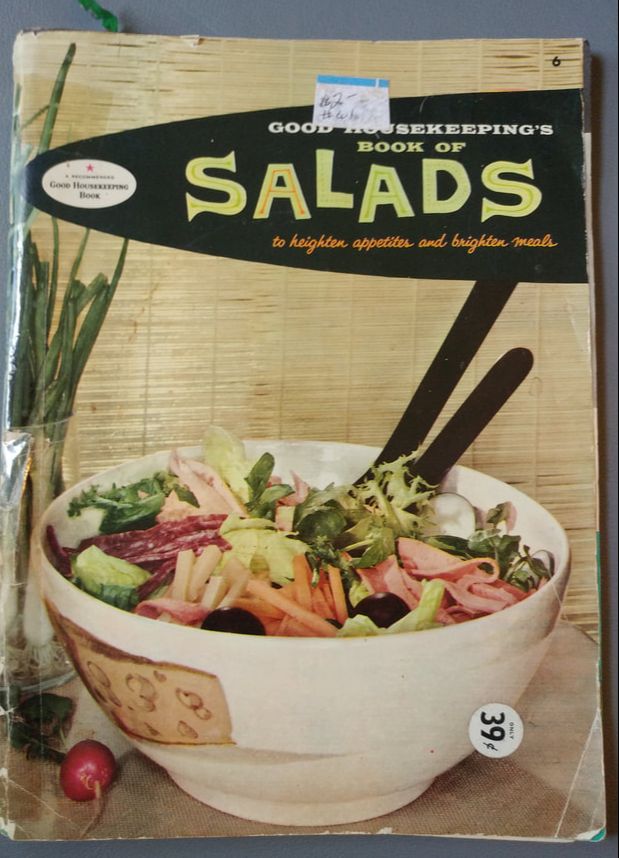

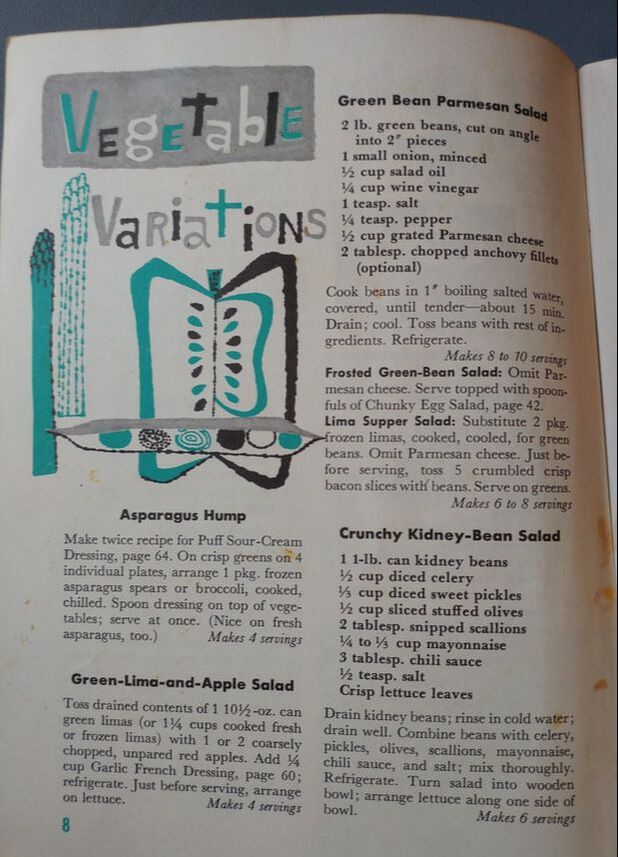

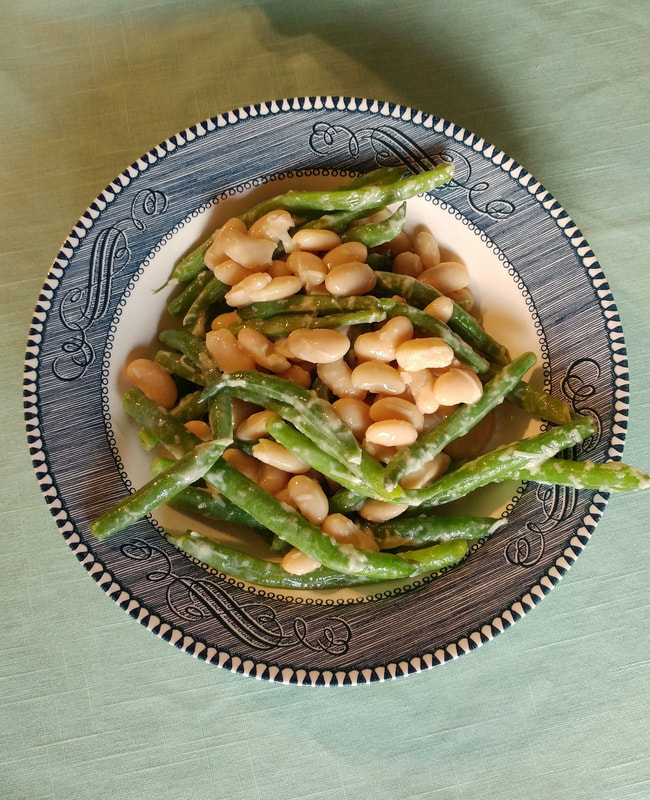

Many of my fans and patrons have been interested in and asking for more of what I call "sturdy salads" - lovely things made of vegetables and legumes and occasionally meats that can be stowed away in the fridge and eaten warm or cold or room temperature. One of our favorites is the Herbed Red Bean Salad I've made many times before. But it was very hot the other day, I was feeling green bean-ish, and was inspired by this little cookbooklet: Good Housekeeping's Book of Salads to heighten appetites and brighten meals (1958). When I made this salad I couldn't find the recipe that I KNEW had inspired it, but I finally tracked it down in this lovely little cookbooklet. Now, there are definitely a million recipes in here for gelatin-and-whipped-cream-based "salads," but there are a surprising number of sturdy vegetable salads - just the kind I like. Green Bean Parmesan Salad (1958)Here's the original recipe, in case the print is too small to read! 2 lb. green beans, cut on angle into 2" pieces 1 small onion, minced 1/2 cup salad oil 1/4 cup wine vinegar 1 teasp. salt 1/4 teasp. pepper 1/2 cup grated Parmesan cheese 2 tablesp. chopped anchovy fillets (optional) Cook beans in 1" boiling salted water, covered, until tender - about 15 min. Drain; cool. Toss beans with rest of ingredients. Refrigerate. Green & White Bean Salad with Lemon & ParmesanMy recipe was a riff on that original. I wanted something a little more substantial for a supper dish, and I thought lemon would be a nice addition to the vinaigrette with the Parmesan. I will say, if I were to make it again, I would actually remember this time to include either minced white onion soaked in lemon juice, or thinly sliced scallions (which I had! But forgot to put in). Diced celery would also not be remiss in this salad - it needs a little extra crunch. 2 cans white cannelini beans, drained and rinsed 1 pound green beans 3 tablespoons olive oil 3 tablespoons lemon juice 2 tablespoons cream (optional) 1 tablespoon dijon mustard 1/4 to 1/2 cup finely shredded Parmesan Bring a few inches of water to boil in a large stock pot. Snap the stem ends and any bad ends off the green beans. Add to the boiling water and cook, covered, for 3-5 minutes (15 is too long!) until bright green and tender. Meanwhile, mix the olive oil, lemon juice, cream, and mustard in a serving bowl and fold in the white beans. Add the hot green beans and mix thoroughly to coat with the dressing. Add the Parmesan and toss to mix well. Serve room temperature with toast. I will say - this would probably be better if you mixed the dressing and the white beans the day before to let the beans fully marinate before adding the green beans. Don't have cannellini beans? Substitute boiled cubed potatoes, steamed cauliflower florets, small white navy beans, or even pasta. Don't have green beans? Substitute asparagus, snow peas, frozen garden peas, or even broccoli. And if you're trying to stay away from carbs altogether, try a combination of just the green vegetables in the sauce. If you liked this recipe, please consider becoming a member or joining us on Patreon. Members and patrons get special perks like access to members-only content, and discounts on programs and classes.

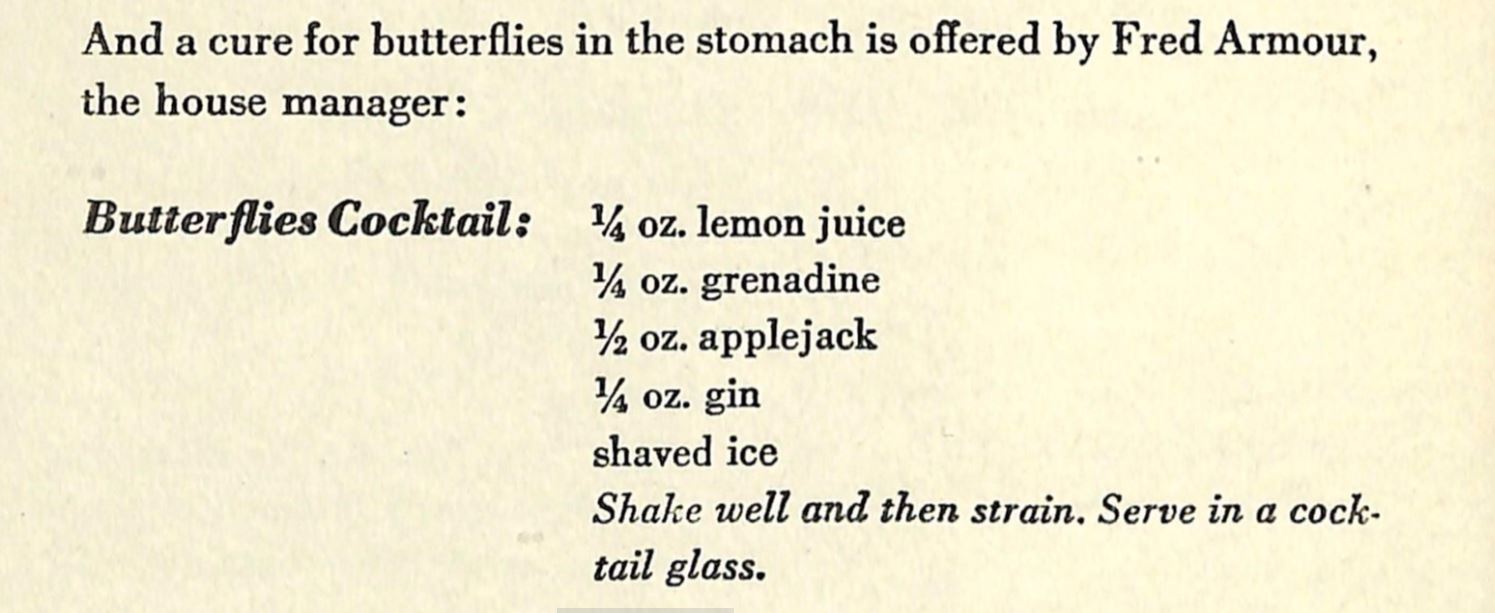

Thanks to everyone who joined me last night for Food History Happy Hour live on Facebook. This week, inspired by spring, all the flowers in my lawn, and supporting the pollinators, we made the Butterflies Cocktail from the Stork Club Bar Book (1946) and talked about edible flowers! We also discussed back of the box recipes, my latest published book review, farmerettes, Elizabeth's excellent question - 5 Recipes New Cooks Should Master During Quarantine, which I outline, and a discussion of lard, modern pork production, and how to render your own animal fats. Butterflies Cocktail (1946)So when I took note of this cocktail many weeks ago, I completely missed that it was designed as a "cure for butterflies in the stomach!" It still tastes like Kool-aid. And Glenn, you and Carla were right! It IS from the Stork Club, but the digitizing website has a typo in the title and referred to it as the "Stock Club." Hence the confusion. 1/4 ounce lemon juice 1/4 ounce grenadine 1/2 ounce applejack 1/4 ounce gin shaved ice Shake well and then strain. Serve in a cocktail glass. Water PieAnd! As a bonus for those who watched the whole video, here's where I first found out about the Great Depression's ingenious "water pie." If I find more, I will update! If you liked this post and would like to support more Food History Happy Hour livestreams, please consider becoming a member or joining us on Patreon. Members and patrons get special perks like access to members-only content.

Thanks to everyone who joined me last night for Food History Happy Hour live on Facebook. This week we made the Black Stripe cocktail - really a hot toddy - from the Roving Bartender (1946). We discussed unusual historic and heirloom vegetables, terrapin and mock turtle soup, the Victorian obsession with game meats, veal, the origins of Caesar salad, springtime greens and foraging, vegetable species diversity and gardening, heirloom grains, the centralization of American food production, tanneries and slaughterhouses, Laura Ingalls Wilder, and updates on my book! Black Stripe Cocktail (1946)I have to admit, this was not my favorite cocktail, but I think it might be that I am simply not a fan of hot toddies. As friend and bartender Mardy and I agreed, "That's a toddy! Hot watery alcohol." Lol. Fill a hot water glass (or an Uffda mug) 3/4 full with boiling water Add 1 spoon of molasses 1 ounce high proof rum (OR 1 1/2 ounces apple pie moonshine) Stir and drink while hot. If you liked this post and would like to support more Food History Happy Hour livestreams, please consider becoming a member or joining us on Patreon. Members and patrons get special perks like access to members-only content.

Thanks to everyone who joined me last night for Food History Happy Hour live on Facebook. This week we used the celery gin I made last week in a choose-your-own-adventure cocktail! Although I could not find any historic references to celery gin, I did find celery bitters, and several other gins that were made by steeping botanicals in gin, including tansy, wormwood, and pine log slivers (yes, really). We discussed historic sauces, peanuts and soybeans, tomatoes, the reasons why flavor extracts and bitters are only available in grocery stores, not liquor stores, ramps, victory gardens, I showed off some of my new cookbook acquisitions, and we discussed comparisons between now and historic pandemics. Celery Gin RecipeWashed celery leaves and tops gin to cover Place celery leaves and tops in a mason jar small enough to hold them so that they mostly fill the jar. Cover with dry gin, screw on lid, and store in a cool dark place for 24-48 hours. Remove celery and discard. Gin will keep indefinitely. Blood Orange Celery Gin CocktailJuice of one blood orange 1/2 to 1 teaspoon sugar 1 ounce gin Shake over ice and serve in a cocktail glass. And here we have a few of the inspirations for this week's choose-your-own-adventure cocktail, from "The Complete Buffet Guide, or, How to Mix All Kinds of Drinks" by V. B. Lewis (1903). If you liked this post and would like to support more Food History Happy Hour livestreams, please consider becoming a member or joining us on Patreon. Members and patrons get special perks like access to members-only content.

|

AuthorSarah Wassberg Johnson has an MA in Public History from the University at Albany and studies early 20th century food history. Archives

July 2024

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed