|

Thanks to everyone who participated in this week's Food History Happy Hour! In this episode we made the Saratoga Cooler from the 1917 Recipes for Mixed Drinks. We also talked about Saratoga Springs, Ann Northup, Saratoga chips and George Crum, Hand melons, watermelon and melons in general, ginger ale, root beer, birch beer, spruce beer, and other lightly fermented soft drinks, by request, my food and cooking memories, celebrating my grandpa's 101st birthday, lemon shakeups and lemonade, tomato sandwiches, Miracle Whip, tomatoes and food storage, the Soviet version of Spam, whether or not to refrigerate eggs, a brief foray into next week's topics of camping, drink pairings, and ice cream. I also asked for input on putting together new talks!

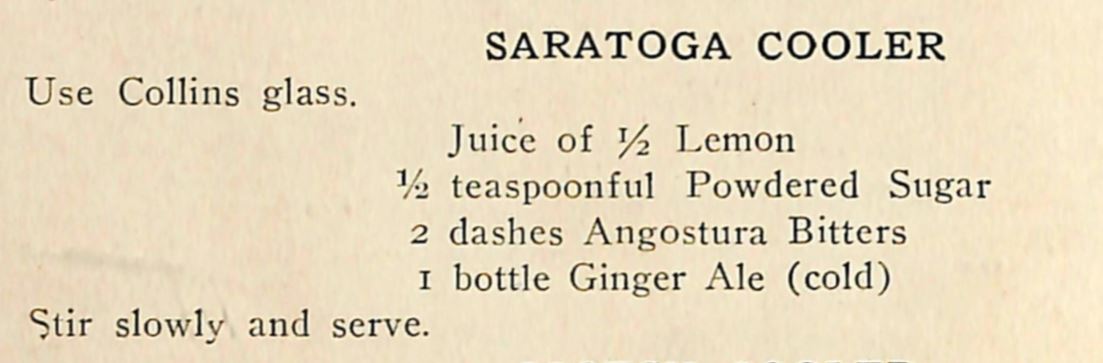

Saratoga Cooler (1917)

The "Saratoga Cooler" cocktail comes from the "Cooler" section of Recipes for Mixed Drinks by Hugo Ensslin (1917).

Here's the original recipe: Use Collins glass. Juice of 1/2 lemon 1/2 teasponful powdered sugar 2 dashes Angostura bitters 1 bottle ginger ale (cold) Stir slowly and serve. I used 1 tablespoon of lemon and just filled the glass with ginger ale. I also added ice to keep things nice and cold and guestimated the powered sugar. It really was quite refreshing though!

And this handsome fella is my grandfather, who just turned 101 years old. He was born on July 3, 1919. Happy Birthday, Grandpa Les!

If you liked this post and would like to support more Food History Happy Hour livestreams, please consider becoming a member or joining us on Patreon. Members and patrons get special perks like access to members-only content.

0 Comments

As part of my new annual jolabokaflod, I ordered Mastering the Art of Soviet Cooking: A Memoir of Food & Longing by cookbook author and Soviet/Russian ex-pat Anya von Bremzen. Ever since I took a semester of Russian on a whim my senior year in college (which helped me properly pronounce the Russian words liberally sprinkled throughout the text), I've been intensely interested in Russian culture and especially food. This book is first and foremost a memoir, not a cookbook, despite the cookbooky title. Von Bremzen and her mother Larisa chronicle their love-hate relationship with the Soviet Union and ultimate escape when Anya was ten years old. Rich in real family histories, idiosyncrasies, and stories, Von Bremzen uses her sometimes fraught family life as a lens to examine the Soviet Union more closely than she had as a child. At its heart, this book is a paradoxical confession - while Anya and Larisa both hate the violence and conformity of the USSR (or CCCP, in Russian), they also long for the nostalgic tastes of their homeland, like black sourdough bread, Kazakh apples, crispy kotleta, highly processed kolbasa, and other difficult-to-procure tastes of Rodina ("Homeland" with a capital H). The book is organized by decade, beginning with the Russian Revolution in the 1910s and the memories of Anya's grandparents. Each chapter is liberally larded with much-needed historical context on the political and social movements and upheavals at the time, illustrated by the lives of von Bremzen's immediate family, relatives, and friends. With each decade, not only does von Bremzen give the social and historical background to the food discussed, she also chronicles the dinner parties she and her mother recreated for each decade, using historically accurate recipes. The last chapter ends in the twenty-first century with Putin's rise to power and the burgeoning obsession in petro-fueled Russia with all things expensive. The book itself ends with a single recipe illustrating each chapter. My Ex Libris edition also comes with a reader's guide featuring a zakushki party menu with recipes at the back. I found this book incredibly compelling, but here and there the historian in me missed some more in-depth narrative. For example, von Bremzen chronicles Stalin's food industry narkom ("people's commissar") Anastas Mikoyan as he journeys to the United States in 1936 at Stalin's behest to study the American food industry. Von Bremzen lists all of the revelations he found abroad, including his amazement at the American hamburger - a cheap and filling snack food - which von Bremzen was horrified to find out was the inspiration for the ubiquitous Soviet kotleta - a thin beef (or chicken or pork) patty with a crispy breading crust deep fried. But while she discusses the consumer end of things and the people who directed the food itself, she does not even mention the manufacturing process nor the workers who produced it. Von Bremzen does discuss briefly the plight of rural agricultural peasants throughout the decades, but her personal history as a city-bred Muscovite doesn't lend itself well to interpreting that agricultural history. Her tantalizing mentions of the Kazakh apple industry, Ukranian pork and wheat industry, and the rich culinary histories of Central Asian nations leave me wanting more information and context. Alas, there is only so much you can fit into a memoir before it comes a history book. This memoir was not only a fascinating read, I learned a lot about the fraught, deprived, and often violent history of the Soviet Union as well as more about the part-industrialized, part-homemade foods that former Soviets speak of with such fondness. I strongly recommend this book for anyone interested in Soviet history or Russian culture. If you'd like to purchase Mastering the Art of Soviet Cooking through this link, I will receive a small commission. |

AuthorSarah Wassberg Johnson has an MA in Public History from the University at Albany and studies early 20th century food history. Archives

July 2024

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed