|

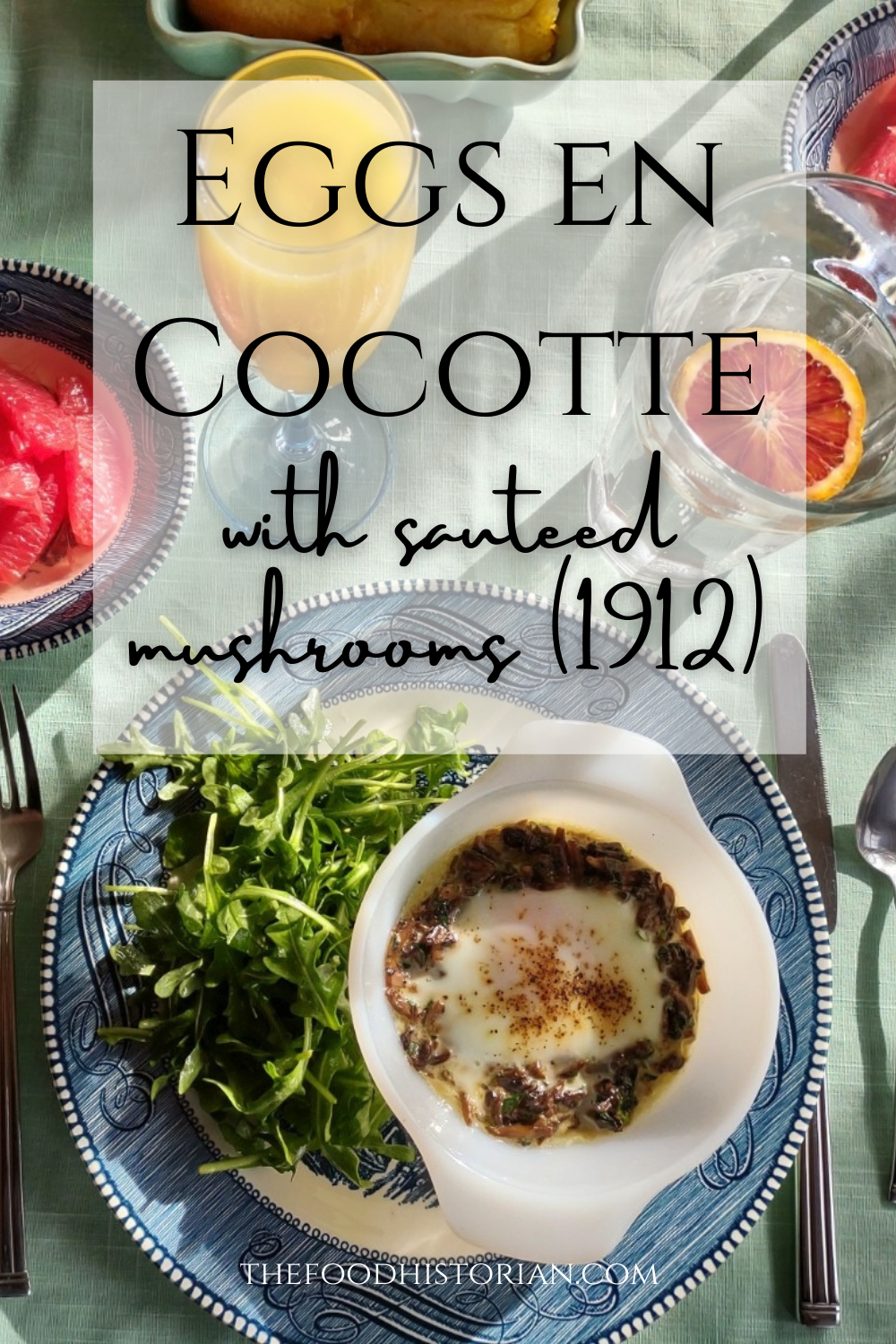

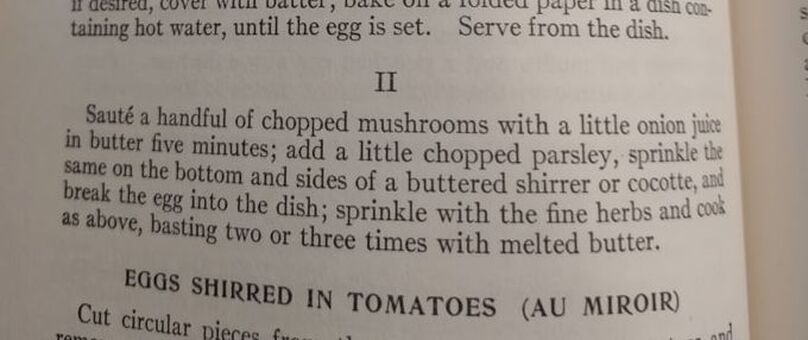

I love brunch. Not the kind you wait in line for, crowded and busy and loud. I love brunch made at home. It's as quiet or loud as you want it to be, the service is usually pretty good, and while there's the effort of making food, if you play your cards right, it's always hot when it gets to the table, and hopefully someone else will do the washing up. Eggs have long been a breakfast staple. If you've a hot skillet, they cook up in a flash. And if you keep chickens, you have a fresh supply every day, at least during the warmer months. But getting a bunch of eggs hot and cooked to order to the table can be a precarious thing when you're hosting. So I took to my historic cookbooks and found a viable solution - eggs en cocotte. Technically, it's oeufs en cocotte, which is French for eggs baked in a type of dish called a cocotte, which may or may not have been round, or with a round bottom and/or with legs. Sometimes also called shirred eggs, which are usually just baked with cream until just set, these days en cocotte generally means the dish spends some time in a bain marie - a water bath. The cookbook recipe I used was from Practical Cooking & Serving by prolific cookbook author Janet McKenzie Hill. Originally published in 1902, my edition is from 1912. You can find the 1919 edition online for free here. A weighty tome of a book, Practical Cooking and Serving is nothing if not practical, and McKenzie Hill is uncommonly good at explaining things. Her section on eggs explains: "Eggs poached in a dish are said to be shirred; when the eggs are basted with melted butter during the cooking, to give them a glossy, shiny appearance, the dish is called au mirroir. Often the eggs are served in the dish in which they are cooked; at other times, especially where several are cooked in the same dish, they are cut with a round paste-cutter and served on croutons, or on a garnish. Eggs are shirred in flat dishes, in cases of china, or paper, or in cocottes. A cocotte is a small earthen saucepan with a handle, standing on three feet." Since my baking dishes were neither the flat oval shirring dishes, nor the handled kind, I guess perhaps they are neither shirred nor en cocotte, according to Hill, but we can afford to be less picky about our dishware. Hill offered two recipes: one more classic version with breadcrumbs (optional addition of chopped chicken or ham) mixed with cream "to make a batter." The buttered cocotte was lined with the creamy breadcrumbs, the egg cracked on top, with the option to cover with more breadcrumb batter. The whole thing was then baked in a hot water bath "until the egg is set." My brunch guest adores mushrooms, and I wanted something a little fancier and more substantial, so I went with Hill's version No. II. Eggs en Cocotte with Sauteed Mushrooms (1912)Hill's original recipe reads: Sauté a handful of chopped mushrooms with a little onion juice in butter five minutes; add a little chopped parsley, sprinkle the same on the bottom and sides of a buttered shirrer or cocotte, and break the egg into the dish. Sprinkle with the fine herbs and cook as above, basting two or three times with melted butter. I will admit I didn't follow the directions as closely as I should have - I didn't use hot water in my bain marie (oops), and I didn't baste with butter. So the eggs were cooked a little more solid than I would have like, but still turned out deliciously. Here's my adapted recipe: 1 pint white button mushrooms, minced 2 tablespoons butter 1 clove minced garlic salt and pepper 2 tablespoons heavy cream 2 tablespoons fresh flat leaf parsley, chopped 4 eggs Preheat the oven to 350 F. Butter three or four small glass baking dishes. Sauté the mushrooms and garlic in butter, adding salt and pepper to taste. When most of the mushroom liquid has cooked off, add the heavy cream and parsley and stir well. Divide evenly among the baking dishes, make a little well, and then crack eggs into dishes. One or two per dish. Salt and pepper the egg, then place in a 9x13" baking pan with two inches of water (use hot or boiling water). Bake 5-10 minutes, or until the egg white is set and the yolk still runny. For firmer eggs, bake 10-15 mins. I did not use boiling water, so the whole thing took more like 20-30 mins for the water to heat up properly, and the yolks got firmer than I would have liked. Tasted delicious, though! This is a very rich dish, so best served with something green and piquant - I chose baby arugula with a sharp homemade vinaigrette (2 tablespoons olive oil, 2 tablespoons lemon juice, 1 tablespoon dijon mustard was enough for 3 or 4 servings of salad), which was just about perfect. You don't have to be a fan of mushrooms to like this dish - white button mushrooms aren't particularly strong-flavored - they just tasted rich and meaty. And despite the fact that eggs en cocotte look and taste incredibly fancy, they were very easy and relatively fast to make. If you were cooking brunch for a crowd, you could certainly prep the mushroom mixture in advance, have the bain marie water on the boil, and make the eggs your last task for a beautiful brunch. With the simple arugula vinaigrette on the side, something sweet and bready (that recipe is coming soon, too) and some fresh fruit and mimosas, you've got yourself a winner. Do you have a favorite egg recipe? The Food Historian blog is supported by patrons on Patreon! Patrons help keep blog posts like this one free and available to the public. Join us for awesome members-only content like free digitized cookbooks from my personal collection, e-newsletter, and even snail mail from time to time! Don't like Patreon? You can leave a tip!

0 Comments

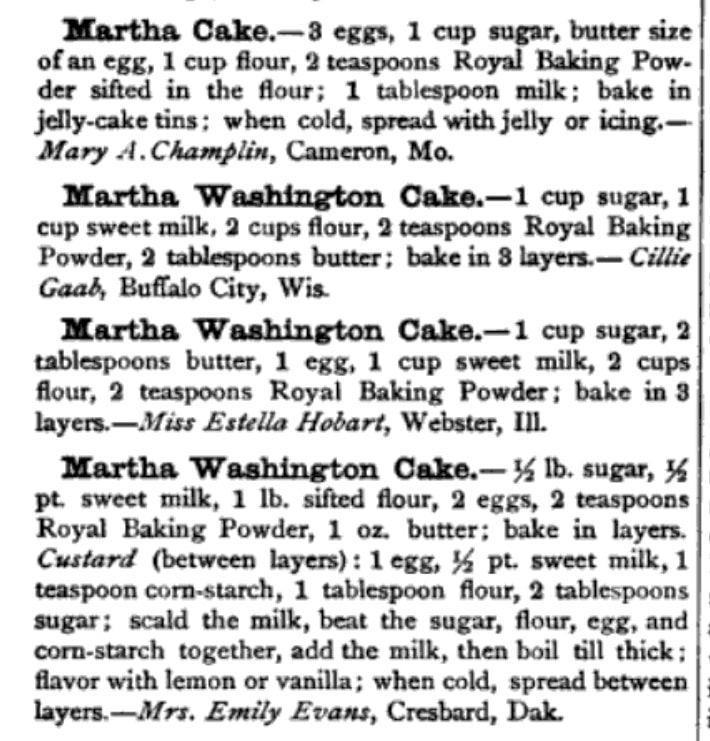

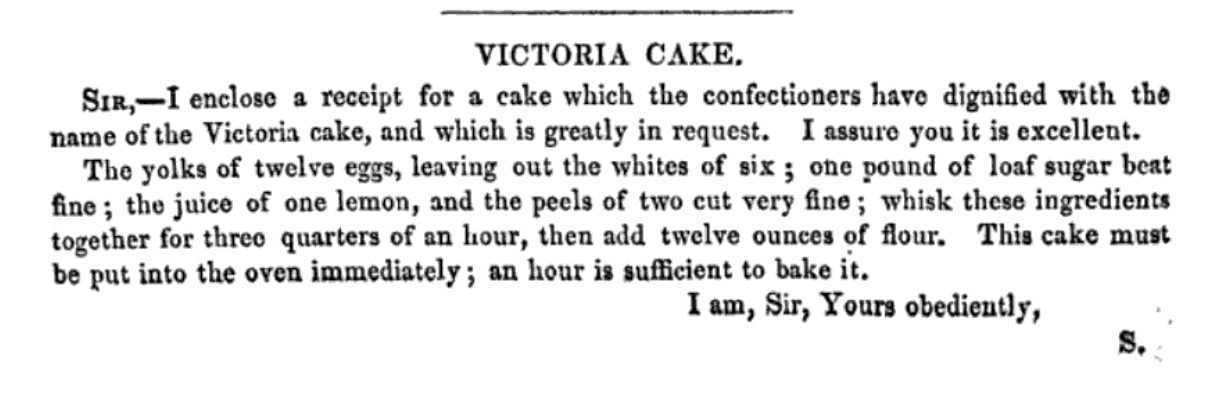

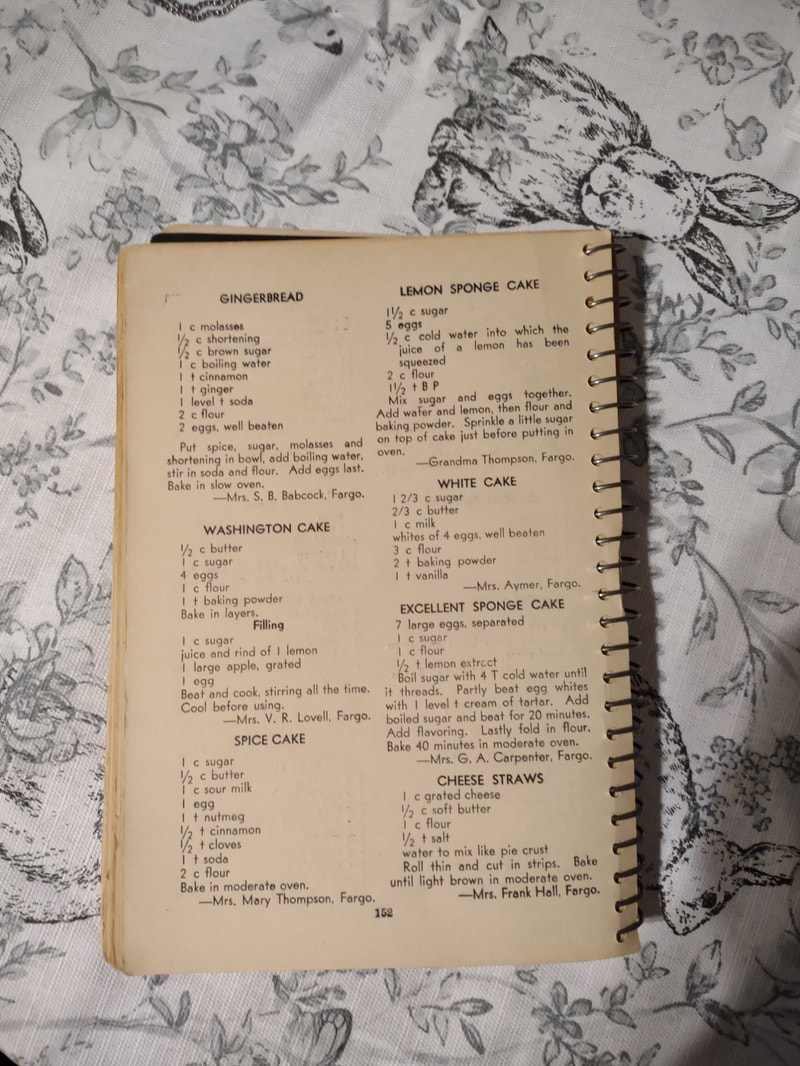

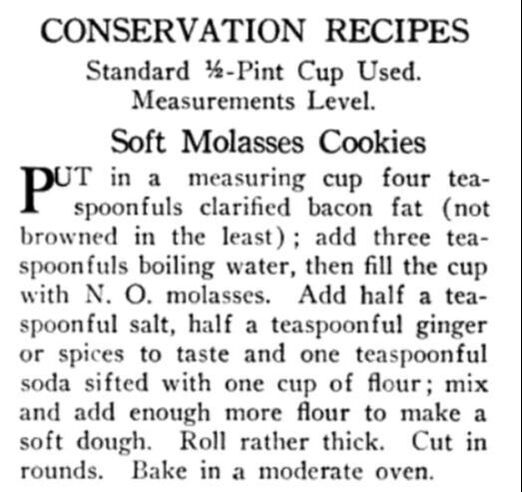

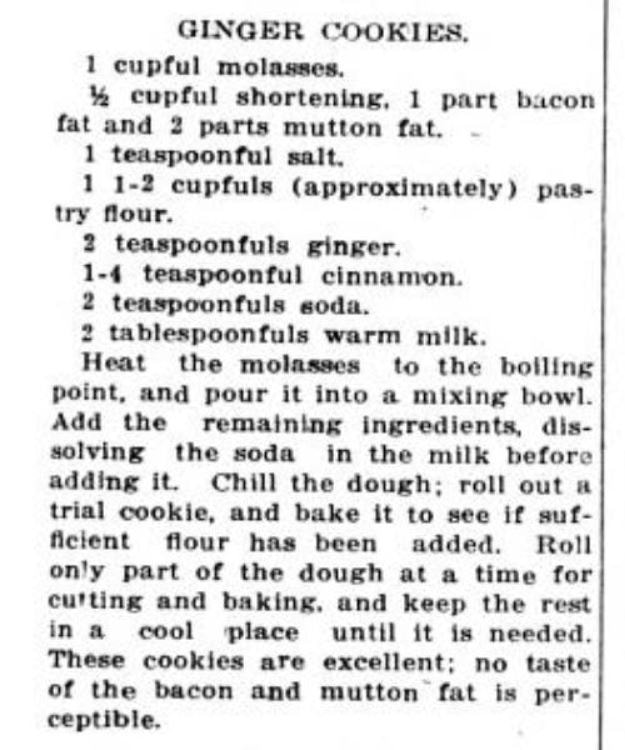

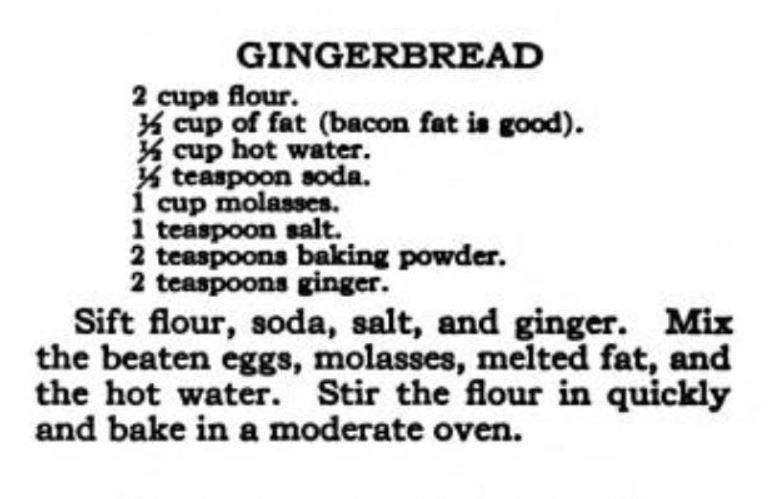

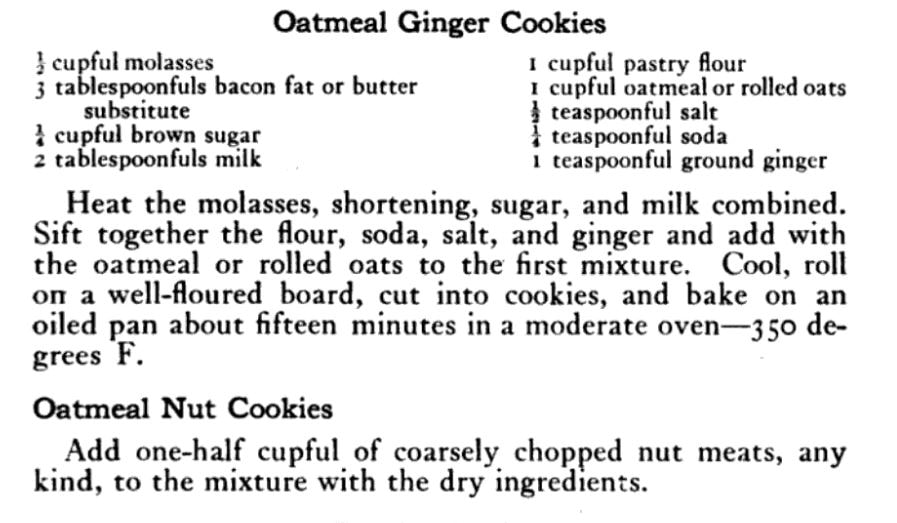

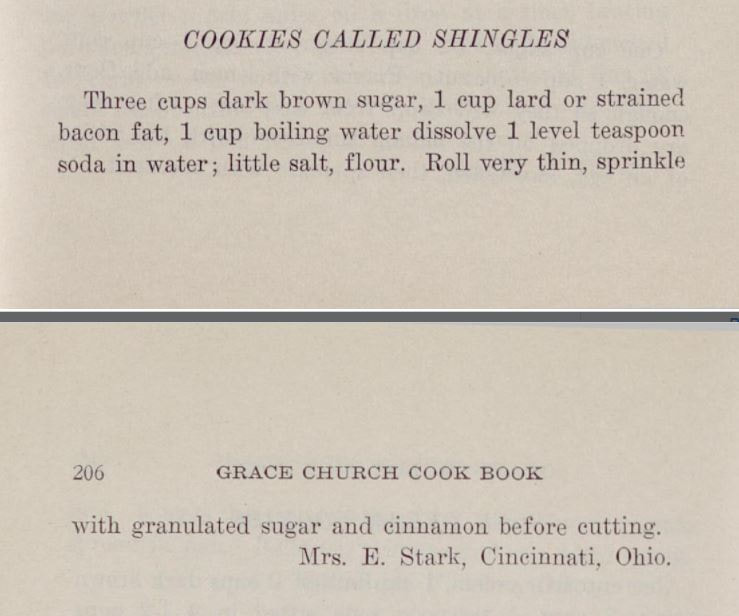

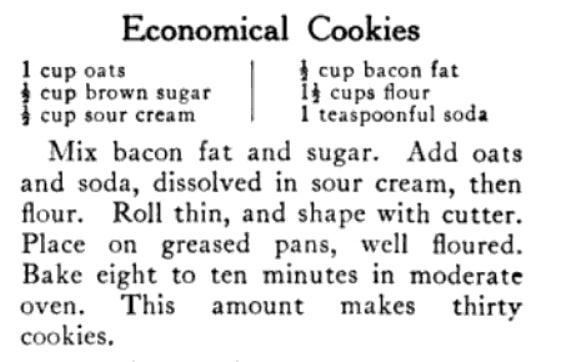

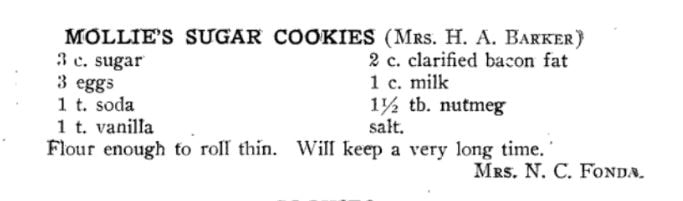

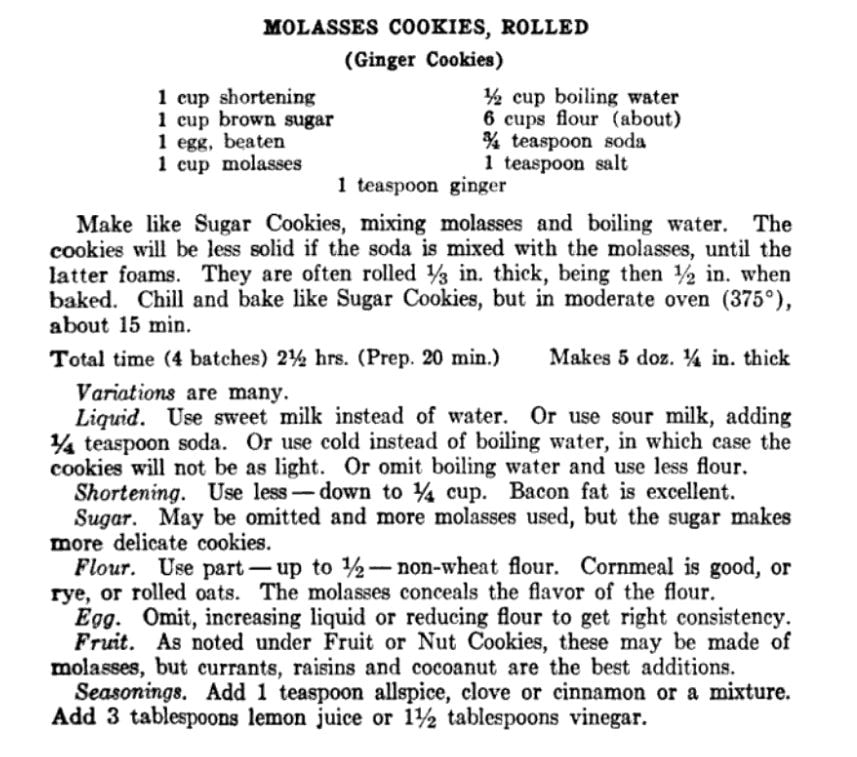

Hello, friends! Just a little note to let everyone know that at the behest of some friends, I have officially joined Substack and my newsletter is called Historical Supper Club! This blog will not go away in the least, and I'm not leaving Patreon. For now, Substack is going to be a place for occasional posts about food history in the context of current events. I'll still be posting food history deep dives, mythbusting, World War Wednesdays, recipes, book reviews, and more here on The Food Historian blog. And Patreon members can still count on fun personal updates and free vintage cookbooks. The Substack newsletter is called "Historical Supper Club," because I wanted to reflect the spirit of a really good dinner party, where good food was accompanied by vigorous discussion of the news of the day. I will likely also include "further reading" and food history news roundups on Substack as well. Last night I posted about the situation in Ukraine on social media. And I seem to have struck a chord with a big group of people. My piece on disgust and 1950s food, and another on COVID and comparisons to the First World War did, too. I've already been interested in the intersections between food history and the present for a long time, so I've decided to lean into that vein a little with this newsletter. If you already subscribe to my regular mailing list, you're now on the Substack list as well. If you're not interested in what you read, feel free to unsubscribe. You won't be unsubscribed from my regular email list and you'll still get the regular blog updates. If you're not already an email subscriber, but Historical Supper Club sounds super interesting, you can subscribe here. As with most of my Food Historian endeavors, I don't want to have to paywall good food history content, so my Substack newsletter is (and probably always will be) free for everyone. But, if you want to support it, you certainly can! You can also support my work on Patreon. For me, what convinced me to join (besides the urging of Jolene at Time Travel Kitchen!) was that Substack offers much better opportunities for community discussion than this blog or my current email setup. This is, after all, a Historical Supper CLUB - that means I want you to come to the table and join the discussion. You can also request commentary on a whole range of issues and provided it's related to food and history in some way, I'm happy to give you my thoughts. I hope you can join me! Washington Pie HistoryWashington pie is everywhere in 19th century cookbooks. Confusingly, it is not a pie. Gastro Obscura traced the history of Washington pie, but spoiler alert - it was called a pie because it was baked in tin pie pans, which back then had straight sides similar to modern cake pans. WHY it was named after George Washington isn't clear - and the earliest references we can find date to 1850. Gastro Obscura and Patricia Reber trace it back to Mrs. Putnam's Receipt Book and Young Housekeeper, by Elizabeth H. Putnam and published in 1850. But I found another reference from 1850, the Practical Cook Book by Mrs. Bliss (of Boston), also published in 1850, for "No. 1 Washington Cake," which included the note "This cake is sometimes called WASHINGTON PIE, LAFAYETTE PIE, JELLY CAKE, &c." Mrs. Bliss' recipe is preceded by the lovely-sounding "Virginia Cake," which calls for sieved sweet potato and molasses, and "Victoria's Cake," which is a lemon-flavored sponge cake with no mention of the jam and cream commonly found in Victoria Sponge. I did find several earlier references to "Washington Cake," many of which were more a type of white fruit cake with currants (Mrs. Bliss' "No. 2 Washington Cake" is of this type), not a layer cake with jelly, with one exception. "Washington Cake" in Mrs. T. J. Crowen's 1845 Every Lady's Cook Book calls for a similar style cake flavored with lemon and brandy. However it does not say to bake it in layers, nor fill it with jam or jelly. But let's take a harder look at that "Layfayette Pie" reference from Mrs. Bliss. Lafayette Pie, Martha Washington Pie or Cake HistoryAlthough Washington Pie is traditionally made with only jam or jelly, there was another variation that shows up later: the Lafayette or Martha Washington Pie/Cake. Similar to Washington Pie, both "pies" are a simple cake baked in thin layers, but instead of filled with jelly or jam, are filled with custard (or more rarely, whipped cream). Confusingly, though the majority of references to Lafayette Pie and Martha Washington Pie call for custard, I have seen occasional references to jelly options, too. The above recipes, from My Favorite Receipt, published by the Royal Baking Powder Company in 1886 is one of the earliest references I can find to Martha Washington Cake/Pie. The first one, called just "Martha Cake" calls for it to be baked in "jelly-cake tins" and spread with "jelly or icing." The next two recipes are identical, and call for the cake to be baked in three layers, but no reference to fillings. The final version (from a North Dakotan!), is the one which also lists the cooked custard filling, to be flavored with vanilla or lemon. The earliest reference I could find for "Lafayette Pie" is Mrs. E. Putnam's 1867 version of her Mrs. Putnam's Receipt Book, which follows the Washington Cake recipe with "Lafayette Pie," a rather less precise recipe than Washington's, which is "enough for two pies" and is followed with "Filling for the Above Pies," seeming to mean both Washington and Lafayette. It reads "Two ounces of butter, quarter of a pound of sugar, two eggs, and one lemon; beat all together without boiling." At first, I read this to mean uncooked, but instead it must mean heated but not boiled - essentially a rich, lemon-flavored custard. The Methodist Cook Book, published in 1899, contains a recipe for "Lafayette Pie," which calls for being baked in a "Deep pie plate," and then cut in half lengthwise (confusingly, it says to "cut out the center to make room for the filling") and filled with a cornstarch-egg custard. Just like Martha's. Boston Cream Pie History As far as I can tell, Lafayette Pie and Martha Washington Pie/Cake are essentially the same: a simple layer cake baked in pie tins and filled with cooked custard. Sound familiar? Recipes called "Boston Cream Pie" were for decades exactly the same - a thin plain layer cake filled with a cooked custard. Contrary to what Gastro Obscura claims, when Americans made Boston Cream Pie at home in the 19th century, it was WITHOUT a chocolate topping. None of the 19th century recipes I could find titled "Boston Cream Pie" (and there were many) contain chocolate at all - only one Maria Parloa recipe calls for chocolate, and that is named "Chocolate Cream Pie." Chocolate-free Boston Cream Pie recipes continue to be published into the 1940s. As far as cookbooks go, Boston Cream Pie doesn't morph into the chocolate-topped version until the 20th century. The Home Dissertations cookbook, published in 1886, includes a recipe for "Boston Cream Pie" among its pastry recipes, even though it is clearly a cake. It calls for the cake to be baked in "round tins so that the cake will be one inch and a half thick" and filled with a cooked custard made with eggs and cornstarch, flavored with vanilla or lemon. No chocolate in sight. How or why all of these "pies" which are really cakes got their names remains lost to history. Likely, the cake was baked in honor of Washington's birthday, or other patriotic occasions. Washington's Birthday became a federal holiday in 1879, which may explain the popularity of the cake at the end of the 19th century. Lafayette and Martha likely followed as other patriotic homages. Other political figures also got their due, like this "Mrs. Madison's Cake" from 1855, which lists just above a white fruitcake-style "Washington's Cake," "Madison Cake" from 1856, and "Mrs. Madison's Whim," a similar-style cake "good for three months" stays in print as late as 1860. Even Jefferson got his own cake, although only in one 1865 edition of Godey's Magazine, and it reads more like a sweet biscuit than a true cake. Political cakes may have been a thing in the 19th century, because the 1874 The Home Cook Book of Chicago has an Adams Cake, a Clay Cake, two Harrison Cakes, and a Lincoln Cake, and the Adams and Clay cakes (named for President John Adams and Senator Henry Clay, one presumes) read very much like Washington Pie. There are also TWO recipes for "Washington Pie," one of which has a filling that includes apples. I could only find one other "Lincoln Cake" in the 19th century, published in 1863. And Boston? It could be that the patriotic cakes were simply popular in Beantown, which leant its name as the "pies" spread elsewhere (a la Boston Brown Bread, Boston Baked Beans, etc.). Certainly the Parker House Hotel in Boston claims to have invented Boston Cream Pie, although I've yet to see any hard evidence (like a recipe or period description) that indicates it had a chocolate topping in the 1860s. Victoria Sponge Cake HistoryWashington Pie really is quite similar to Victoria Sponge, which if you're a fan of the Great British Bakeoff, you know is one of Britain's (and Queen Victoria's) favorite desserts. And, ironically, not actually a sponge cake, as it calls for butter (true sponge cakes have no fat). Likely developed in the late 1840s, coinciding with the development of baking powder in 1843, and adopted by the Queen in mourning in the 1860s. Like Washington Cake, some of the first references to "Victoria Cake" are much closer to a white fruitcake or pound cake than a sponge, like this recipe from 1842, or this recipe from 1846 by Francatelli. The first recipe to a sponge-style Victoria Cake comes in 1838, the year after she became queen (recipe pictured above) from The Magazine of Domestic Economy. Although it does not call for filling of either jam nor whipped cream. The oft-cited recipe published in The Practical Cook (1845), is identical to the 1838 recipe, down to the letter. Of course, Mrs. Bliss' "Victoria's Cake," published in 1850, while not identical to the letter, is certainly just a slightly re-worded copy. Despite the popularity of the sponge, "Victoria's Cake" continues to be the yeasted fruitcake that Francatelli and later Soyer keep pushing well into the 1860s. "Victoria Sandwiches" come into play in the 1850s, whereby pieces of sponge cake are sandwiched with jam and topped with pink icing, a la The Practical Housewife, published in 1855 by Robert Kemp Philp. Ridiculously, Francatelli's version of "Victoria Sandwiches" are a literal sandwich, made with hard boiled egg and anchovies. Not quite as flattering to the queen. Mrs. Beeton wisely hops on the sponge cake "Victoria Sandwiches" bandwagon in the 1860s. Although curiously none of these early recipes call for whipped cream to accompany the jam. Perhaps because Mrs. Beeton's recipe for Victoria Sandwiches is immediately followed by one for Whipped Cream, maybe someone put two and two together. Which cake was inspired by whose we'll perhaps never know. Unless some manuscript cookbook has in it somewhere "Washington Pie, from Victoria's Cake" or "Victoria Sandwiches, in the style of Washington Pie." Regardless, it was the exact right kind of cake to associate with heads of state, apparently, once everyone got over heavy white fruit cakes laden with lemon and currants and alcohol. In making a birthday brunch for a friend, I wanted to focus on vintage recipes and had Washington Pie already in mind. But unwilling to use the internet (cheating!), I instead consulted my historic cookbooks. I had been on the lookout for another recipe, when I found a recipe for "Washington Cake" in one of my North Dakota community cookbooks, this one dating to the 1940s: The North Dakota Baptist Women's Cook Book. The cookbook does not have a publication date, but there is a reference to 1947 in the frontspiece, and from that and judging by the style of font and print, we can safely date it to the late 1940s, possibly 1950, but not much later. Interestingly, the recipe for Washington Cake was in a section in the back called "1905 Recipes" and dedicated to the women of the First Baptist Church of Fargo, ND, which was built in 1905. The recipes that follow were all written by women of the church for that first construction - likely from an older cookbook. The dedication reads, "In loving memory of those who have made a very definite contribution to the Christian cause through their labors in the First Baptist Church of Fargo, N. D., and who have left behind them fruits that are being utilized in this book, this page is gratefully dedicated." It then lists two biblical references to death and a list of women's names. The recipes read as much older than 1905, with emphasis on things like brown bread, suet pudding, doughnuts, gingerbread, and mincemeat. Likely they were submitted as "colonial" or similar "old-fashioned" recipes that were part of the popular colonial revival that began at the turn of the 20th century. The recipe for "Washington Cake" was contributed by Mrs. V. R. Lovell of Fargo, ND. It reads: 1/2 c butter 1 c sugar 4 eggs 1 c flour 1 t baking powder Bake in layers. Filling 1 c sugar juice and rind of 1 lemon 1 large apple, grated 1 egg Beat and cook, stirring all the time. Cool before using. Not exactly the most descriptive recipe I've ever read, but better than many! I decided not to use the interesting-sounding filling, although I may revisit it at a future date. Instead, I wanted to go the jam-and-cream route. 1905 Washington Cake (or Pie), AdaptedUnlike a traditional sponge cake, which can be quite finicky with separating egg whites, I found this recipe to be just as delicious, but much simpler. As an added bonus, you don't have to split a taller cake evenly lengthwise - the layers are already thin enough to stack as-is. You can use any kind of jam, but I chose my favorite brand of strawberry. 1/2 cup butter 1 cup sugar 4 eggs 1 cup flour 1 teaspoon baking powder 1 teaspoon vanilla (or lemon or extract) Strawberry jam Whipped cream Preheat the oven to 350 F. Butter well two round cake pans. Cream but the butter and sugar together, then add the eggs one at a time, beating after each addition. Add the vanilla (or lemon), then the flour and baking powder, then mix well until everything is well combined. Pour equal amounts into the two cake pans, then bake on the center rack for approximately 30 minutes (check after 20 - when the cake is golden at the edges and the center springs back to the touch, it is done). Tip the cakes out of their pans onto a cooling rack and let cool completely. Then spread strawberry jam on one layer, and top with whipped cream (I stabilized mine with cornstarch - which you could taste, so I would not recommend doing that again), then add the second layer, more strawberry jam, and more whipped cream. If you want this cake to keep better, I would recommend going the traditional Washington Pie route and just filling thickly with strawberry jam, and serving it with whipped cream on top to taste. This cake is very easy, bakes relatively quickly, and tasted delicious. It was VERY sweet, so I might cut back on the sugar slightly if I make it again. But while I'm sure Great British Bakeoff experts would criticize the fact that I didn't weigh my ingredients or make sure my eggs were room temperature, I thought the cake turned out very lovely indeed. And the combination of cake, whipped cream, and sweetened fruit can never be wrong. As for all the other political cakes? I may have to do some more investigative baking for Presidents' Day 2023. The Food Historian blog is supported by patrons on Patreon! Patrons help keep blog posts like this one free and available to the public. Join us for awesome members-only content like free digitized cookbooks from my personal collection, e-newsletter, and even snail mail from time to time! Don't like Patreon? You can leave a tip! I first ran across bacon fat gingersnaps in the Christmas cookie collection the New York Times posted for December, 2021. Although I'm not a NYT Cooking subscriber, I did a google and found an article about the original recipe, which indicated the recipe was likely historic. Even though I'd just finished my Christmas cookies research, the bug bit again and the hunt was on. I found several historic recipes for bacon fat cookies, some of them gingery, some of them not (scroll to the bottom for the gallery of recipes), but because I am a World War I historian, I decided that the recipe I was most interested in at the moment was the "Soft Molasses Cookies" listed as a "Conservation Recipe" in the February, 1918 issue of American Cookery, formerly the Boston Cooking School Magazine. And it seemed appropriate to be baking them in February, 2022! The recipe is not written in a way we're used to today, but is fairly straightforward. It reads: Put in a measuring cup four teaspoons clarified bacon fat (not browned in the least); add three teapsoonfuls boiling water, then fill the cup with N.O. [New Orleans] molasses. Add half a teaspoonful salt, half a teaspoonful ginger or spices to taste and one teaspoonful [baking] soda sifted with one cup of flour; mix and add enough more flour to make a soft dough. Roll rather thick. Cut in rounds. Bake in a moderate oven. This recipe is sugarless, eggless, and butter-less, and it uses fats that might otherwise go to waste, making it the perfect conservation recipe during a time when Americans were asked to save wheat, sugar, meat, and fats for the war effort. The use of New Orleans molasses was specifically to save space on cargo ships and support American sugar production (molasses is a byproduct of sugar cane processing). By using bacon fat, normally a waste fat, Americans could save on lard and butter. Bacon Fat Soft Molasses Cookies (1918)I will admit that I started this recipe before I realized I was virtually out of all-purpose flour. And since I had a good deal of whole rye flour to use up, and I thought it in keeping with the spirit of the recipe to make this wheatless as well, I used all rye (although in the period rye was not considered an official substitute for wheat, largely because it was in fairly short supply). It did make a rather heartier cookie than I think was intended, but it worked just fine. Here's my translation of the original: 2+ cups flour (I used whole rye) 1 teaspoon baking soda 1/2 teaspoon salt 1/2 teaspoon ground ginger 4 teaspoons bacon fat 3 teaspoons boiling water a little less than 1 cup molasses Preheat the oven to 350 F. In a large mixing bowl, whisk together 1 cup flour, the baking soda, salt, and ground ginger. In a heat-proof measuring cup, place the bacon fat and add the boiling water. Then add molasses enough to make 1 cup. Pour into the flour mixture and beat well. Add more flour (about another cup) until a soft dough forms. You may need more flour as the dough will be very sticky. Knead in a little more flour as needed to make a dough that can be rolled without excessive stickiness. Flour your rolling surface well, and roll out the dough about a half inch thick, or a little thicker. Cut into rounds and bake on a parchment-lined baking sheet (to prevent sticking and save on grease!) at 350 F for 10-12 minutes. My batch rolled relatively thin made just short of 2 dozen largish cookies. Next time I would probably let them be a little thicker and I'd probably end up with a dozen and a half. Although these aren't crisp or particularly sweet, they do taste astonishingly close to the Archway brand of molasses cookies you can find very inexpensively in just about every grocery store. Soft, and a little cakey, with strong molasses flavor and just a hint of gingery spice. I couldn't really taste the bacon fat while they were still warm (though my husband claims he could), but the flavor will likely improve the next day. I did frost a few to dessert-them up a little. Just a few teaspoons of heavy cream mixed with some powdered/icing sugar. Shhh! Don't tell Herbert Hoover! Although these are quite soft right out of the oven, they will harden up as they cool, so be sure to store them in an air-tight container to help retain moisture. All things considered, I think this recipe turned out rather well for one that was supposed to be a bit of a privation during the war. Although I don't think it was UN-common to use bacon fat or drippings or any other animal fats as shortening in baking in the 19th century (indeed in the 1800s "shortening" just meant any kind of solid fat - remember we don't get vegetable shortening until the 1870s), we don't really see bacon fat specifically called out in cookbooks until the 1910s. One reason is likely that bacon was an increasingly popular breakfast food. Oscar Mayer, in particular, started selling pre-packaged sliced bacon in 1924. Breakfast was rebranded in the 1920s away from stodgy porridges and even health-food cold cereals and toward bacon, eggs, and tableside electric appliances that made things like waffles, fresh-squeezed orange juice, coffee, and toast. All that bacon frying meant that cooks had a surfeit of grease, and frugal cooks would hate to waste it. And while bacon fat is perfect for frying potatoes into hash, there's only so many things you can fry in bacon fat. Hence, the baking recipes. As you can see from the collection below, they're all for 1915 and later, with most in the 1920s. Bacon fat was saved in WWII as well, but housewives were just as likely to save the fat for munitions than bake with it. Once animal fats were connected to heart disease in the 1950s, bacon took a back seat in the United States until its revival in the 2000s (largely coinciding with the popularity of the Atkins Diet). We don't make bacon all that often. Usually it's with a big breakfast or brunch I make on the weekends. But I've made a point lately to save the fat. If you bake your bacon in the oven like I do (450 F for 10-15 mins), you can just pour the fat off of the baking sheet and into a glass jar. Keep the jar in the fridge and you'll have a smoky, salty fat for flavoring beans, potatoes, eggs, and yes, even molasses cookies. Which bacon fat recipe do you think I should try next? I'm leaning towards the sugar cookies... The Food Historian blog is supported by patrons on Patreon! Patrons help keep blog posts like this one free and available to the public. Join us for awesome members-only content like free digitized cookbooks from my personal collection, e-newsletter, and even snail mail from time to time! Don't like Patreon? Just leave a tip

Happy Valentine's Day, Food Historian friends!

If you spend way too much time on social media (like me), you've probably seen this meme crop up in the weeks before Valentine's Day. I think I started seeing it in January! But it piqued my interest, so here we are. What is it about Sweethearts (a.k.a. Conversation Hearts) that inspires to much hatred? As far as I can tell, the meme was created by Molly Hodgdon in 2019, and while it got some attention on Twitter, it wasn't until someone screenshotted it (without attributing Molly, sadly - cite your sources, people!) that it started to go viral on social media.

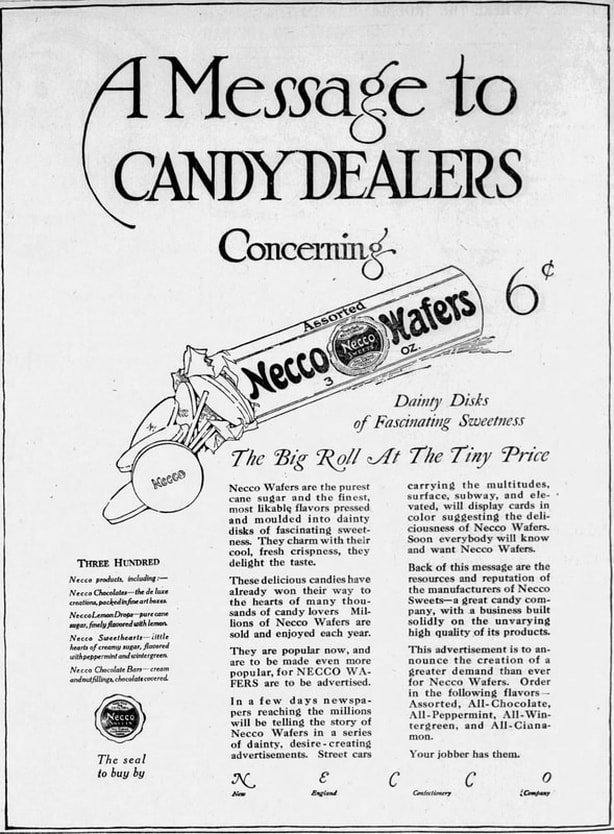

NECCO, which makes the very similar Necco wafers, is the acronym of the New England Confectionary Company. NECCO was formed in 1901 as a conglomeration of multiple regional confectionary/candy companies, the oldest of which was Chase and Company, founded in 1847 by British pharmacist Oliver R. Chase and his brother Silas Edwin, both based in Boston, Massachusetts. That year, Oliver apparently patented a machine designed to cut out candy lozenges (although no one can seem to find the original patent), and the pair went into business producing sugar-and-gum lozenges in a circular shape.

Although several sources claim the Union Army supplied soldiers with "hub wafers" during the American Civil War, I can find no primary source references, and neither could Heather Cox Richardson, so take that claim with a very large grain of salt. It is possible Union soldiers consumed the candy wafers, but unlikely they were issued by military supply, which was pretty decentralized at that point anyway. "Hub" was a nickname for Boston, and the phrase "hub wafers" shows up mostly in newspapers in the 1910s, right when NECCO was heavily advertising. "Hub wafers" were the phrase used to get around the use of the brand-name Necco.

Boston was a major candy-making center for one primary reason - ready access to sugar. Since its founding, Boston had been a major port for the Triangle Trade - enslaved Africans in the Caribbean labored on sugar cane plantations - the sugar and molasses were shipped to Boston, where the sugar was further refined and the molasses made into rum - and then the rum was used as a bargaining chip or payment taken on Boston sailing ships to the coast of West Africa, where people were captured and enslaved, and delivered to the Caribbean, hungry for slave labor as the brutal conditions dramatically shortened the lifespans of the enslaved. The ships picked up sugar and molasses and headed north again.

Even after the abolition of slavery, Boston remained a primary shipping hub for sugar, and therefore candy. Second NECCO company Ball & Forbes was founded in Boston in 1848, and Bird, Wright, and Company in 1856. The three companies consolidated in 1901 into NECCO. At any rate, the wafers (not to be confused with wax wafers used to seal envelopes for sending through the mail), got an upgrade in 1866, when another Chase brother - Daniel Chase - created "conversation candies" - which may or may not have been heart shaped, but had sayings printed on the candies (I think - sources conflict). I've been hard-pressed to determine what exactly these looked like, but "conversation hearts" in reference to candies show up as early as 1859 in newspapers. The original candies were larger than today's, and not all were in the shape of hearts - some were shaped like horseshoes, pocket watches, postcards, and seashells, among others.

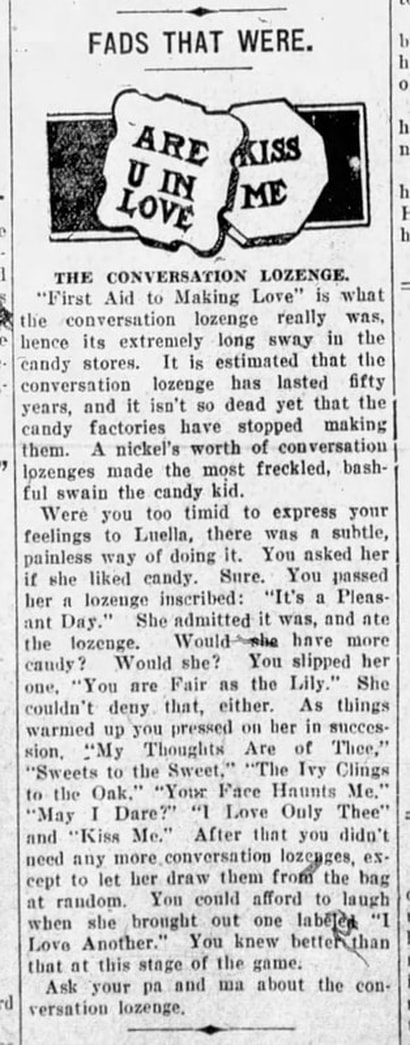

Even by 1907 the "conversation lozenge" was considered old-fashioned. In an article entitled "Fads that Were: The Conversation Lozenge," The Brooklyn Citizen writes:

"First Aid to Making Love" is what the conversation lozenge really was, hence its extremely long sway in candy stores. It is estimated that the conversation lozenge has lasted fifty years, and it isn't so dead yet that the candy factories have stopped making them. A nickel's worth of conversation lozenges made the most freckled, bashful swain the candy kid. Were you too timid to express your feelings to Luella, there was a subtle, painless way of doing it. You asked her if she liked candy. Sure. You passed her a lozenge inscribed: "It's a Pleasant Day." She admitted it was, and ate the lozenge. Would she have more candy? Would she? You slipped her one, "You are Fair as the Lily." She couldn't deny that, either. As thins warmed up you pressed on her in succession, "My Thoughts Are of Thee," "Sweets to the Sweet," "The Ivy Clings to the Oak," "Your Face Haunts Me," "May I Dare?" "I Love Only Thee" and "Kiss Me." After that you didn't need any more conversation lozenges, except to let her draw them from the bag at random. You could afford to laugh when she brought out one labeled "I Love Another." You knew better than that at this stage of the game. Ask your pa and ma about the conversation lozenge. To see examples of what the original conversation lozenges looked like, check out this collection from the Genesee Country Village & Museum in Mumford, NY.

Most of us today probably also consider conversation hearts old-fashioned, but more likely because we encountered them in grade school rather than associating them with the 19th century! Those self-contained, inexpensive, non-melting boxes of candy were too easy for parents to purchase for the days when you had to get a Valentine for everyone in the class. But the texture and flavor is definitely a hallmark of centuries past.

And, of course, that's what the meme at the start of this article is referencing, isn't it? "Wild clayberry" aside, the original flavors of Necco Sweethearts were quite 19th century indeed - peppermint and wintergreen only.

At some point the flavors and colors were expanded. It's not clear what flavors were instituted when. Some sources indicate the original flavors included banana, cherry, and wintergreen. Another source lists wintergreen, orange, lemon, banana, grape, cherry, and blue raspberry, but clearly that last one doesn't date to the early 20th century. These flavors read as more modern, as opposed to Necco Wafers, whose original flavor lineup was wintergreen, lime, clove, orange, chocolate, lemon, cinnamon (the white ones, curiously, and wintergreen was pink), and licorice. Talk about 19th century flavors. Necco did also make all-chocolate, all-peppermint, and all-cinnamon rolls of wafers early on.

In the 1960s, Brach's Candy Company got in on the conversation hearts game - their recipe is a bit softer but the flavors are nearly identical to Necco Sweethearts - lemon, banana, cherry, grape, orange, and yes, wintergreen. Gotta keep the minty roots intact. It's not clear when precisely Sweethearts became so sharply aligned with Valentine's Day, but given the candy's long romantic history, it's not surprising. Necco continued to consolidate throughout the 20th century - buying up candy companies right and left. But eventually the size became untenable and Necco went bankrupt in 2019, and production of Sweethearts and Necco wafers, among other candies, briefly ceased. The company was acquired by Spangler Candy Company in 2020 and they managed to crank out an uneven production, despite the pandemic and manufacturing woes. Spangler also saved Mary Jane candies from extinction. Today, Sweethearts are back in business. The meme begs a larger question than I think most people would consider: What role does nostalgia play in our food consumption choices? Do people buy and eat (or not eat) Sweethearts and other nostalgic candy simply because they really love the taste/texture? Or do they simply evoke pleasant memories of childhood? Or perhaps they represent a childhood or some validation never fully acquired? I would argue it's probably some combination of all of the above. Like smell, taste can be a powerful trigger for memories - happy or otherwise. So if you grew up associating Sweethearts with Valentine's Day, you might want to continue that association, or pass on the tradition to a new generation. But as we've discussed before (here and here), I'm a firm believer that on person's "gross" can be another person's "delicious." For me, while Sweethearts aren't my favorite, they're not awful either. But if I'm going to consume chalky historic candies, I'm going to sit and eat a whole can of creamy butter mints (which we called dinner mints, and which were a feature of nearly every wedding reception I attended as a child), rather than a box of Sweethearts. Although my mom's homemade cream cheese mints (also a feature of weddings, molded into pink roses and white bells and the peppermint flavored ones were green leaves) would be even better. But then they're not chalky and storebought, and wedding/dinner mints are a tale for another blog post. What do you think? Are Sweethearts delicious? Nostalgic? Disgusting? Weigh in in the comments, and Happy Valentine's Day to everyone, regardless of your relationship status.

The Food Historian blog is supported by patrons on Patreon! Patrons help keep blog posts like this one free and available to the public. Join us for awesome members-only content like free digitized cookbooks from my personal collection, e-newsletter, and even snail mail from time to time! Don't like Patreon? Just leave a tip!

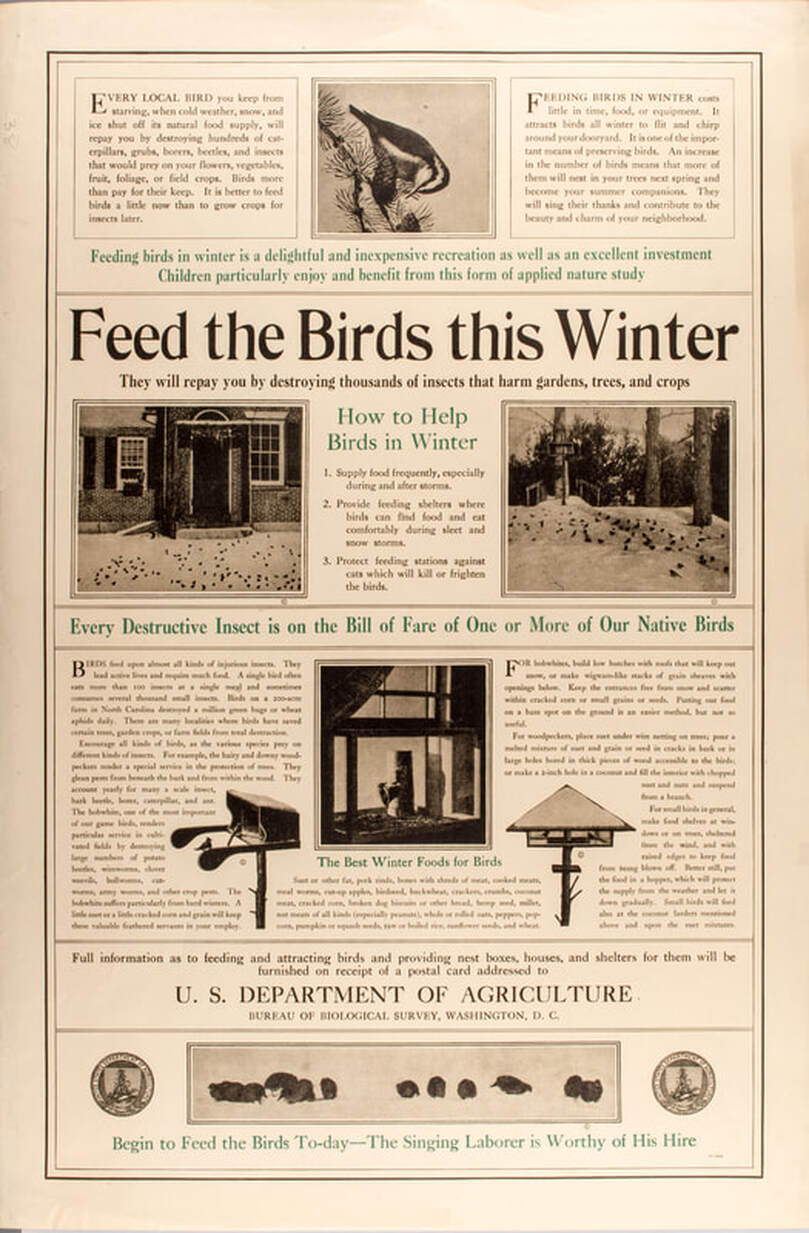

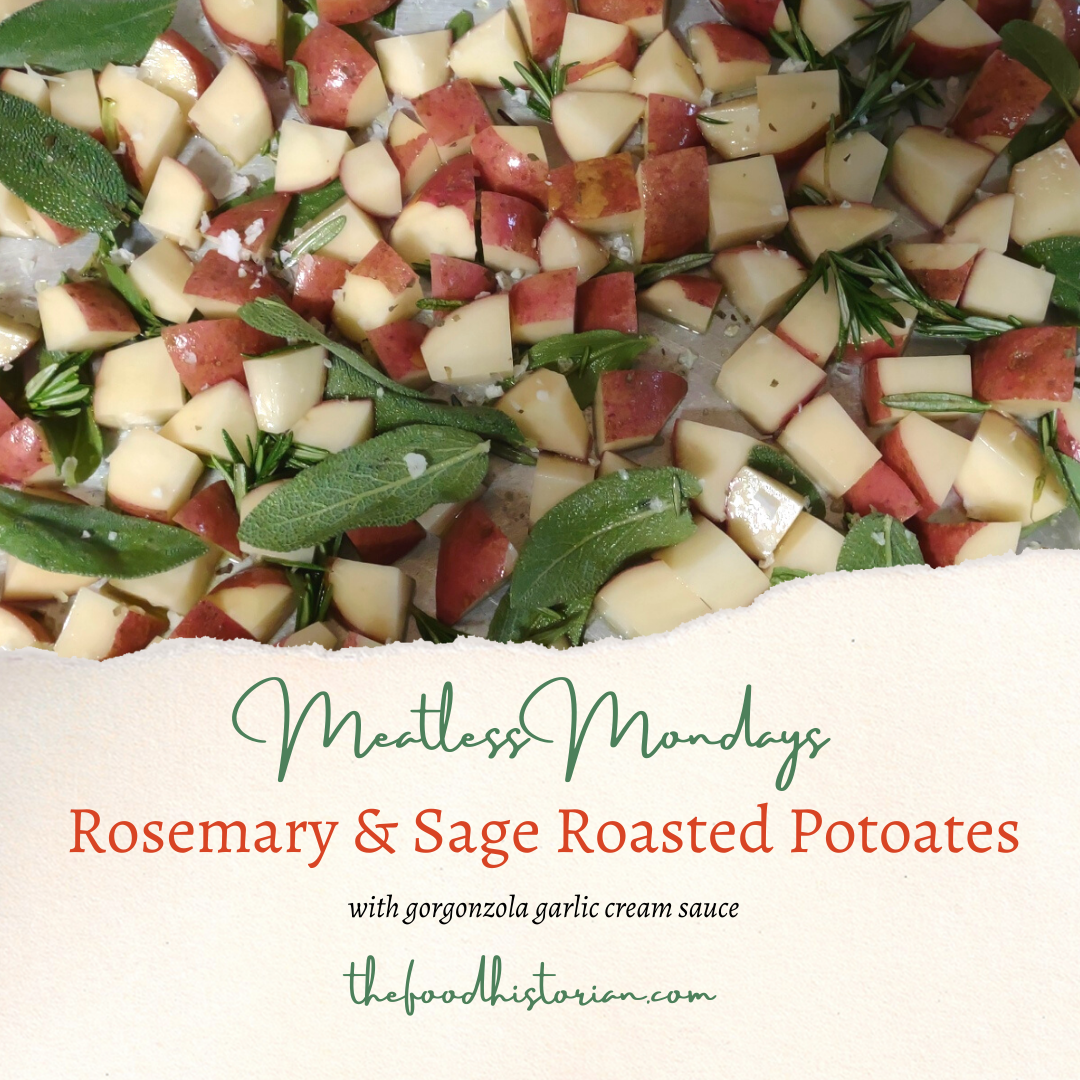

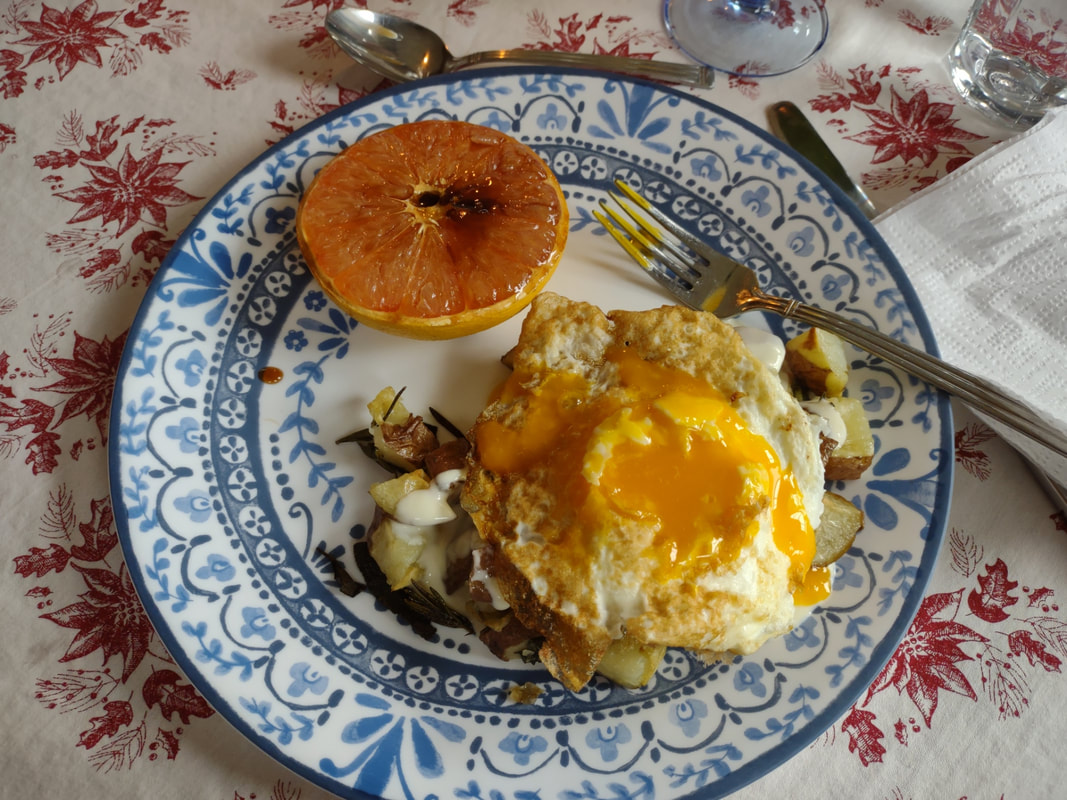

We're getting into some of the more obscure WWI posters now! This poster is from the United States Department of Agriculture, specifically the Bureau of Biological Survey. "Feed the Birds This Winter: They will repay you by destroying thousands of insects that harm gardens, trees, and crops" is the main message of this poster. Suggesting that ordinary Americans feed birds "especially during and after storms," provide shelter, and protect feeding areas from bird predators, the poster connects "our native birds" to their insect-eating abilities. This is a very text-heavy poster, so I've transcribed it all so you can know what it says! "EVERY LOCAL BIRD you keep from starving, when cold weather, snow, and ice shut off its natural food supply, will repay you by destroying hundreds of caterpillars, grubs, borers, beetles, and insects that would prey on your flowers, vegetables, fruit, foliage, or field crops. Birds more than pay for their keep. It is better to feed birds a little now than to grow crops for insects later. "FEEDING BIRDS IN WINTER costs little in time, food, or equipment. It attracts birds all winter to flit and chirp around your dooryard. It is one of the most important means of preserving birds. An increase in the number of birds means that more of them will nest in your trees next spring and become your summer companions. They will sing their thanks and contribute to the beauty and charm of your neighborhood. "Feeding birds in winter is a delightful and inexpensive recreation as well as an excellent investment. Children particularly enjoy and benefit from this form of applied nature study." "Feed the Birds this Winter. They will repay you by destroying thousands of insects that harm gardens, trees, and crops. "How to Help Birds in Winter "1. Supply food frequently, especially during and after storms. "2. Provide feeding shelters where birds can find food and eat comfortably during sleet and storms "3. Protect feeding stations against cats which will kill or frighten the birds. "Every Destructive Insect is on the Bill of Fare of One or More of Our Native Birds. "BIRDS feed upon almost all kinds of injurious insects. They lead active lives and require much food. A single bird often eats more than 100 insects at a single meal and sometimes consumes several thousands small insects. Birds on a 200-acre farm in North Carolina destroyed a million green bugs or wheat aphids daily. There are many localities where birds have saved certain trees, garden crops, or farm fields from total destruction. "Encourage all kinds of birds, as the various species prey on different kinds of insects. For example, the hair and downy woodpeckers render a special service in the protection of trees. They glean pests from beneath the bark and from within the wood. They account early for many a scale insect, bark beetle, borer, caterpillar, and ant. The bobwhite, one of the most important of our game birds, renders particular service in cultivated fields by destroying large numbers of potato beetles, wireworms, clover weevils, bollworms, cut-worms, army worms, and other crop pests. The bobwhite suffers particularly from hard winters. A little suet or a little cracked corn and grain will keep these valuable feathered servants in your employ. "FOR bobwhites, build low hutches with roofs that will keep out snow, or make wigwam-like stacks of grain sheaves with openings below. Keep the entrances free from snow and scatter within cracked forn or small grains or seeds. Putting out food on a bare spot on the ground is an easier method, but not so useful. "For woodpeckers, place suet under wire netting on trees; pour a melted mixture of suet and grain or seed in cracks in bark or in large holes bored in thick pieces of wood accessible to the birds; or make a 2-inch hole in a coconut and fill the interior with chopped suet and nuts and suspend from a a branch. "For small birds in general, make food shelves at windows or on trees, sheltered from the wind, and with raised edges to keep food from being blown off. Better still, put the food in a hopper, which will protect the supply from the weather and let it down gradually. Small birds will feed also at the coconut larders mentioned above and upon the suet mixtures. "The Best Winter Food For Birds "Suet or other fat, pork rinds, bones with shreds of meat, cooked meats, meal worms, cut-up apples, birdseed, buckwheat, crackers, crumbs, coconut meat, cracked corn, broken dog biscuits or other bread, hemp seed, millet, nut meats of all kinds (especially peanuts), whole or rolled oats, peppers, popcorn, pumpkin or squash seeds, raw or boiled rice, sunflower seeds, and wheat. "Full information as to feeding and attracting birds and providing nest boxes, houses, and shelters for them will be furnished on receipt of a postal card addressed to U.S. DEPARTMENT OF AGRICULTURE, Bureau of Biological Survey, Washington, D.C. "Begin to Feed the Birds To-Day - The Singing Laborer is Worthy of His Hire." Much of this advice is still sound today! At the time, of course, it was marrying not only nature study for children (a VERY popular topic during the Progressive Era) but also advocating for more natural forms of pest control in a time when pesticides existed, but had limited applications, and the availability of which was likely curtailed by more important wartime manufacturing. Birds do require an incredible number of insects to survive (bats, too), and even seed and fruit-eating songbirds feed their nestlings insects to give them the protein and fat they need to grow. Today, more and more farmers are returning to birds - from raptors to songbirds - to address pest issues, from pest birds (like starlings and seagulls) and rodents to insects. In some instances, the birds outperform pesticides. And contrary to what most people put in their bird feeders, birds eat a LOT of insects. Which is why I was surprised and happy to see mealworms on the list of recommended foods for birds, alongside suet and nuts. I've been feeding the birds in winter and early spring (we take the feeders down in the summer) to support the population, but also to let up a little on the insect population. Unlike 100 years ago, we're currently facing an insect apocalypse, which could have huge repercussions across the planet, including, but not limited to, agriculture, as many of our favorite crops rely heavily on pollination from wild insects. Which is why, even though I'm not a farmer and we're not at war, I still feed the birds in the winter. You can see my setup in the photo above - I have several squirrel-proof feeders (determined squirrels can get by even the baffles, but they provide shelter for the birds during the rain) with different mixes. One is a fruit, nut, and shelled sunflower seed mix with mealworms. Two more are just straight black oil sunflower seed. One has suet, and another feeder, which we're trying new this year, is just straight mealworms and beetles. Sadly, that one has been less popular. Maybe those insects don't have enough fat in them. Our half-dead holly tree provides enough spreading branches for the feeders but also cover from predators like hawks. Birds like to have cover they can escape to when predators come calling. And yes, that includes cats! Outdoor and feral cats are the number one predator of songbirds in suburban and urban areas. So keep your kitties inside or build them a catio. If they knew it in WWI, we should know it now. It is most important to support native birds, and not pest birds like starlings (who, while fascinating, are native to Europe and can out-compete native birds), so keep your food focused on native seeds, fruits, and nuts whenever possible. Just watch out for inexpensive fillers that aren't eaten by most songbirds. Sunflower seeds, peanuts, pecans, walnuts, raisins, blueberries, and cracked corn are all great. Suet (raw or rendered beef fat) is also good, as is natural peanut butter (avoid the hydrogenated kind, the kind with palm oil, and sugar), for providing the fat needed to keep birds warm and well-fed during the coldest winter months. I have set up our bird feeders right outside the kitchen window, and like Progressive Era nature study enthusiasts knew, they do provide a great deal of joy. I love coming to the kitchen every morning and checking to see what birds are at the feeders, and which ones need refilling. Since it has been incredibly cold and icy here in the Hudson Valley of New York this winter, our feeders have been almost as busy as Grand Central! We've seen cardinals, blue jays, tufted titmice (my favorites!), nuthatches, chickadees, sparrows, purple house finches, gold finches (they're mostly brown in the winter), downy woodpeckers, red breasted woodpeckers (whose breasts are actually just pink - it's the heads that are red!), dark-eyed juncos, mourning doves, and yes, even the occasional starling. More rarely we've seen cedar waxwings, rose-breasted grosbeaks (another favorite!), phoebes, and even the rare overwintering bluebird (though not actually on the feeders). Another way to support native birds (and insects!) is to plant native plants, especially fruit-producing shrubs for birds. For insects, native trees, especially oaks, can host up to 400 species of insects, including moths and butterflies. Okay, I'll get off my soapbox now! But always nice to see good sense from a century ago still holding true today. Do you feed the birds? Have a favorite winter visitor? Tell us in the comments! The Food Historian blog is supported by patrons on Patreon! Patrons help keep blog posts like this one free and available to the public. Join us for awesome members-only content like free digitized cookbooks from my personal collection, e-newsletter, and even snail mail from time to time! Don't like Patreon? Just leave a tip! Meatless Monday: Brunch with Rosemary & Sage Roasted Potatoes and Gorgonzola Garlic Cream Sauce2/7/2022 It's been so bitterly cold lately, I thought I would finally share this stunner of a vegetarian brunch with everyone. A few weeks ago we had a friend over for brunch. It had been a long couple of post-holiday weeks, and everyone was playing catchup at work. So I thought having something delicious and comforting for brunch would help take the edge off. A favorite local Italian restaurant of ours has an appetizer I adore - waffle fries fried with sage and rosemary with a side of gorgonzola cream sauce for dipping. It's divine. I wanted to replicate something similar at home, but brunchified, and with a little lighter hand. So I decided to roast some red potatoes with sage and rosemary and olive oil. I had intended to pick out the herbs as I'm generally not a fan of whole rosemary leaves, but everything fried up in the olive oil so beautifully that we devoured the herbs alongside the potatoes. I topped the potatoes with a fried egg, to make things feel more breakfast-y, with a side of broiled grapefruit for a vintage feel and to cut the fat a little. Sadly I used brown sugar, so instead of caramelizing it just melted everywhere. Still tasted yummy though. We had faux mimosas (the friend doesn't drink alcohol) which were also delicious. The star of the show, though, was the potatoes and cream sauce. Divine. Rosemary & Sage Roasted PotatoesI used a fancy flake salt flavored with wild garlic, so if you're using regular sea salt, maybe add just a dash of garlic powder or some minced garlic. 6-8 medium red potatoes 1 container/bunch fresh sage 1 container/bunch fresh rosemary olive oil coarse sea salt Preheat oven to 450 F. Scrub the potatoes, cut off any eyes or bad parts, and cut into similarly-sized cubes. Wash the herbs and strip the leaves off of the rosemary stems. Pop the sage leaves off of their longer stems. On a large half sheet pan, spread the potatoes, and drizzle with olive oil. Add the herbs and using your hands, gently toss everything to combine (you can do this in a bowl if it's easier) and spread out in one layer, making sure the potatoes all have a cut end facing down. Sprinkle with salt and put in the oven. Roast for 20-30 minutes, or until potatoes are perfectly tender, with crisp brown bottoms. When ready to serve, use a very flat spatula to scrape up the crispy bits and put the whole shebang, potatoes, herbs, and all, into a serving dish. Garlicky Gorgonzola Cream SauceOne of the miracles of heavy cream is that if you reduce it, it turns into this silky sauce with no need for a roux in sight. 1 pint heavy cream (use more if you like!) 2 cloves garlic 1+ cup crumbled gorgonzola salt & pepper to taste With the flat side of a knife slightly crush your peeled garlic cloves, and add them to the heavy cream in a heavy-bottomed saucepan and cook over medium heat. Let the cream simmer, but do not boil, until reduced slightly (it should coat a spoon) and fragrant with garlic. Fish out the garlic cloves and discard. Add the gorgonzola and stir to melt. Give it a taste and add salt and pepper as needed. Keep hot until ready to use. To make brunch, pile some potatoes on a plate, add a ladle of gorgonzola sauce, and top with a fried egg. If you're like me (over medium, please!), you like to break the runny yolk. Virgin MimosasIf you're entertaining folks for brunch who don't want or can't have alcohol, virgin mimosas are delightful. We had sparkling cider from New Year's Eve that had gone un-opened, but you could just as easily use ginger ale or 7-up instead. 1 part sparkling cider 1 part high-quality orange juice champagne flutes Are they really mimosas without the champagne flutes? Pour half and half into each flute, and don't worry about drinking too many. Broiled GrapefruitDo as I say, not as I did. Brown sugar does not work. Lesson learned! 1/2 fresh grapefruit per person 1 tablespoon granulated white sugar per half grapefruit Set the broiler to high. Cut grapefruit in half and place on a metal sheet pan or other broiler-safe dish (do not use glass baking dishes under the broiler!). Gently smooth the tablespoon of sugar over the top. Place under the broiler and cook 1-2 minutes (watch them!) until the sugar is caramelized. Serve with grapefruit spoons, if you have them. Otherwise a dessert spoon or butter knife works, too. In the bleak midwinter, a sunny brunch can really lift the spirits. But don't skimp on the trappings. Light some taper candles. Pull out the champagne flutes and an ice bucket. Dig out the grapefruit spoons (I don't have any yet!). It can really make the difference. Don't have any of that? Make a list and keep your eyes peeled once you feel it's safe to go antiquing again. Fancy glassware can usually be had for a song at thrift shops, and since glass is inert, a quick wash in hot soapy water and it will be fit for use, no matter what shape it was in when you got it (so long as it's not broken or cracked!). Have you been doing anything special lately to make winter seem less dreary? The Food Historian blog is supported by patrons on Patreon! Patrons help keep blog posts like this one free and available to the public. Join us for awesome members-only content like free digitized cookbooks from my personal collection, e-newsletter, and even snail mail from time to time! Don't like Patreon? Just leave a tip! |

AuthorSarah Wassberg Johnson has an MA in Public History from the University at Albany and studies early 20th century food history. Archives

July 2024

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed