|

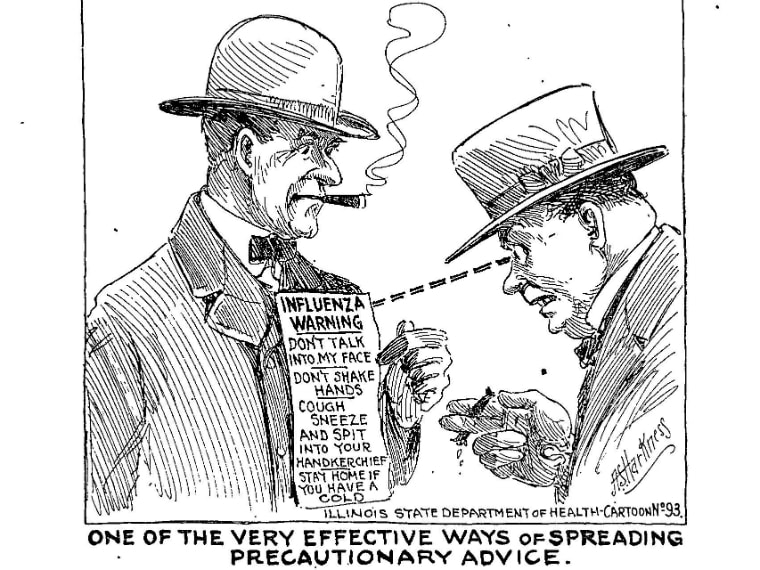

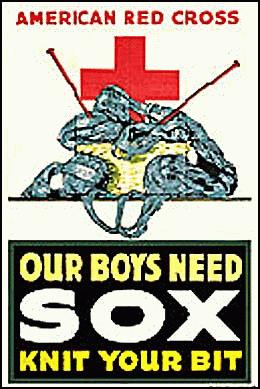

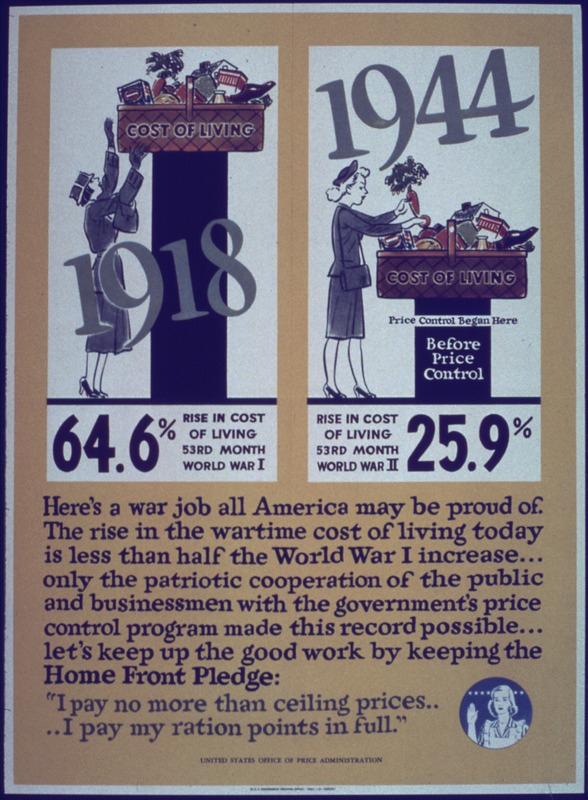

Y'know that old saw, "Those who ignore history are doomed to repeat it?" Well, like a lot of old adages, this one has a big grain of truth in it. Historians often can see parallels to the modern world as they study history. Indeed, my area of specialty - the Progressive Era and World War I home front - has led to LOTS of comparisons to modern life. But with the addition of the coronavirus lockdown, the comparisons grew more numerous. To that end, I thought I would catalog some of the striking similarities. Failure of Bureaucracy: Military SupplyOne thing that has becomes especially striking at this time is the failure of the federal government to manage national supplies during an emergency. In this instance, it's the management of medical supplies for COVID-19, particularly personal protective equipment (a.k.a. PPE). States are competing on an open market and with each other, driving up prices and leading to shortages. To make up the shortfall, ordinary citizens are creating homemade versions of masks, face shields, and other equipment. During the first months of the U.S. entrance into World War I, the exact same thing was happening. Historian Robert Ziegler in his book America's Great War: World War I and the American Experience, outlines the deplorable state of military supply following the Spanish American War. Individual battalions were competing with each other on the open market to purchase supplies, thus driving prices up. In addition, the United States had never fielded such an enormous army and the production of other military supplies, such as uniforms and rifles had yet to keep up with the demand of a suddenly-enormous army. According to historian David M. Kennedy, in his book Over Here: The First World War and American Society, soldiers were sent to Europe with hardly any training. Men and boys who had been recruited in July, 1918 were on the front lines by September. Some men arrived never having used a rifle, and had to take an intensive 10 day course before being sent into battle. The logistics of shipping war materiel, both within the borders of the United States and overseas was also a mess, causing railroad and port backups. Some credit the poor supply of soldiers in training camps (inadequate clothing, bedding, housing) with exacerbating the effects of the Spanish Flu pandemic. Combined with this was the efforts of the American Red Cross. Famed for providing bandages and nursing aid during the American Civil War, thousands of chapters sprang up across the nation and throughout 1917, women were encouraged to "knit their bit" by knitting sweaters, socks, wristers, and watch caps for "our boys" being sent overseas. Why? Likely because military supply chains were, as stated, in shambles and because it was easier (and cheaper) to task the nation's women with keeping soldiers warm than to mobilize factories. Wool socks in particular were in high demand because of the poor conditions in the trenches. But by 1918, according to historian Christopher Cappazola in his book, Uncle Sam Wants You: World War I and the Making of the Modern American Citizen, the federal government was frantically telling women to STOP knitting, likely because military supply was completely reorganized. Although there are plenty of resources about knitting in WWI and the American Red Cross (including this lovely one), few people seem to have made the connection between "knitting your bit" and the failure of military supply. It was only part-way through American participation in the war that the federal government reorganized military supply under a centralized Quartermaster General. It wasn't until the Korean War that the United States passed the Defense Production Act (1950), which empowered the federal government to compel private business to prioritize the production of war materiel and prevent hoarding and price gouging. If the United States were to learn the lesson of WWI supply today - the federal government would coordinate with individual states to purchase - and allocate - medical supplies where most needed, instead of bidding against states on the open market. Xenophobia, Immigration, RaceIn the years leading up to the First World War, the United States was inundated with immigrants from all over the world, but particularly Eastern and Southern Europe. The United States was also recovering from the abandonment of Reconstruction and Black Americans were becoming more and more prosperous, with a growing middle class. Combined with a brain and labor drain on rural areas, this led to people like President Theodore Roosevelt warning of "race suicide" for White Anglo Americans unable to keep pace with the more fertile immigrants. Roosevelt also worried about rural life and started the Country Life Commission to study and combat the drain of population from rural America to urban areas. Tempted by "cosmopolitan" life, reformers worried, young people would be corrupted and the bedrock foundation of democracy - the landowning yeoman farmer - would diminish. Unfortunately for reformers, the majority of people in rural areas lived difficult lives and particularly in the South, most did not own the land they farmed. But the idea that rural America, and farmers in particular, are the "salt of the earth" is an idea that has persisted even today. With "flyover country" being courted by politicians, especially conservative ones, with every election. Immigration and race remain hallmark dogwhistles in modern politics. The Trump campaign used the slogan "America First" on the campaign trail - echoing the campaign slogan of Woodrow Wilson leading up to his first term as a neutral isolationist. It was a policy he would abandon in his second term, as the U.S. entered World War I in the spring of 1917. Americans were notoriously isolationist in the early 20th century (except for their colonialist ambitions in Central America, Hawaii, and the Phillipines) and America's first propaganda machine had to be created to convince them that joining the war was a good idea. To convince them, Woodrow Wilson invented the idea of defending and spreading democracy (and American exceptionalism) abroad - a policy that has continued to be used in every American war since then. Attempts to Americanize immigrants remained in effect throughout the war. Progressive reformers from settlement houses and canning kitchens on up to proponents for the war which thought a draft would help Americanize immigrants tried to force people into the mold of White Anglo American (usually Northeastern) culture. Black Americans faced similar pressures, and segregated versions of just about every middle-class voluntary organization - including the Red Cross - was implemented during the war. Following the war, newly economically mobile Black Americans, buoyed by industrial jobs for war production, faced even more hostility than before. Resentment by racists clashed with confident (and armed) veterans returning from war. The Tulsa Race Massacre of 1921 is just one example of Black WWI veterans attempting to defend themselves and their communities. Race riots, lynchings, and a dramatic expansion of the Ku Klux Klan were the hallmarks of 1919, 1920, and beyond. Today, Black American communities still deal with over-policing, incarceration, and violence. Latinx-Americans have dealt with a dramatic ramp-up of incarceration, family separation, and deportation (even of children), as well as more casual racism. And Asian-Americans in particular have borne the brunt of some horrific incidents of racism directly related to the coronavirus - as the ignorant believe that they (regardless of whether or not they had been to China recently, or were even of Chinese descent) were "carriers" of the disease - another old saw of racism most famously used by Nazis against the Jews (among others). The High Cost of LivingIn the two decades leading up to WWI, the United States underwent a series of depressions and recessions. Starting with the Depression of 1893 (which the US did not recover from until 1897-98), and with smaller recessions in 1907 and 1913-14, the "high cost of living" (commonly abbreviated as "HCL" or "H.C.L.") saw a dramatic rise in cost of living, including food and housing, while wages stagnated. Called "stagflation" by economists, this situation led to labor unrest, and strikes, food boycotts, and food riots were all common during this time period. Socialists were also in political ascendancy due to income and labor inequalities. Labor strikes were often broken by deadly force. Food boycotts and riots remained the purview of the desperate - often women with starving children which tugged at the heartstrings of wealthy and middle-class White Progressives, even as some were organized by socialist activists (read about the 1917 food riots in New York City). Many of the strikes and riots of the 1900s and 1910s led to serious labor reform, including the ending of child labor, worker safety reforms, reduced hours, and more. New York City during WWI tried to pass a minimum wage law, but it was vetoed by the Mayor. Today's parallels include a different sort of high cost of living - most "luxury" items are cheaper than they've ever been, but housing, education, healthcare, and food costs have risen by as much as 200% in the last 20 years. In addition, democratic socialists and real, "bread and roses" socialists have seen their numbers spike in the last few years. Activists are fighting for a minimum wage increase, universal healthcare, and other reforms, although union membership has taken a steep dive in the last few decades. Coronavirus has only highlighted the "essential" role many low-wage workers play in American life, and some retail workers, cleaners/janitors, and restaurant workers are now being hailed as heroes alongside medical professionals and scientists. War Gardens & RationingOne particularly fascinating trend that appears to be occurring right now is the skyrocketing sale of vegetable seeds and plants. Tied in part to the fact that so many Americans are sheltering in place and have time to garden, the resurgent interest in "Victory Gardens" is also a reaction to temporary shortages in grocery stores (due to logistics, rather than supply) and fears that the food supply might be endangered by coronavirus. The First World War was also one of the first times in American history that a concerted effort to get ordinary people to plant kitchen gardens. Of course, part of that was because of the changing demographics of population. People in rural areas had almost always had kitchen gardens. But as more and more people moved into urban and suburban environments, and fresh food supplies became easier and cheaper to acquire, kitchen gardens became less necessary, and most people who could afford to focused on flower gardens instead. But the U.S. entrance into the war, with its commitment to feeding the Allies, came with very real fears that food would be in short supply. This was reinforced by rhetoric from Wilson and Herbert Hoover, the new U.S. Food Administrator, who knew that in the spring of 1917, existing crops would be inadequate to feed both Americans, their growing army, and the Allies without serious changes. Enter war gardens and voluntary rationing. Hoover was the brains behind the idea of voluntary rationing - he wanted Americans to show the world their personal fortitude and strength through voluntary efforts, including rationing. He also believed that the bureaucracy necessary to enforce mandatory rationing would not only be hugely expensive, it would also be ineffective. To lead by example, Hoover and the entire Food Administration were all volunteers. Rationing included refraining from eating wheat, meat, butter, and sugar whenever possible, and by the fall of 1917, "wheatless, meatless, and sweetless" days were implemented. Grain and flour substitutions, sugar substitutions, and vegetarian meals became more normalized during the war. The National War Garden Commission was also a voluntary organization, albeit a private, not public, one. Started by forestry magnate Charles Lathrop Pack, it encouraged Americans, especially school children, to plant "war gardens" (later renamed "victory gardens," a name that would resurface during WWII) which would provide fresh vegetables for ordinary people. Not only would this free up conventional food supplies, the production of local food would also free up transportation resources, which by the end of 1917 were becoming so congested that the United States temporarily nationalized its railroads. Spanish Influenza "One of the very effective ways of spreading precautionary advice." The man in the illustration wears a sign on his chest reading, "Influenza Warning: Don't talk into my face; don't shake hands; cough, sneeze, and spit into your handkerchief; stay home if you have a cold." Illustration from the Illinois Health News, 1918. "One of the very effective ways of spreading precautionary advice." The man in the illustration wears a sign on his chest reading, "Influenza Warning: Don't talk into my face; don't shake hands; cough, sneeze, and spit into your handkerchief; stay home if you have a cold." Illustration from the Illinois Health News, 1918. And, of course, the obvious one. I've already written a bit about the Spanish Flu, but it bears noting that during the course of the 1918 pandemic, the government was reluctant to report real numbers or spread information about the severity of the pandemic because they were worried that it would endanger the war effort or reduce morale. Some cities, like Philadelphia, held enormous and patriotic Liberty Loan parades, allowing the virus to spread like wildfire. In fact, despite evidence that the influenza strain likely started in the United States, it wasn't until neutral Spain was infected, and its newspapers reported the real death toll, that the general public learned of the pandemic. Hence the name, "Spanish Influenza." Similar things are happening now, with the Trump Administration's initial reluctance to admit coronavirus was a serious problem because they feared the effect on the economy. Conflicting information in the media (and from the President) about the severity of the virus and the need for social distancing and stay at home orders have exacerbated the problem here in the U.S. More recently, a dearth of testing has led to some experts to conclude that the death toll is severely underreported. We are now also learning that China has likely suppressed or underreported the true infection rate and death toll from coronavirus. Thankfully, unlike 1918, when newspapers largely cooperated with government propaganda efforts (under threat of having their licenses revoked, effectively putting them out of business), modern information is more accessible and immediate than ever through the internet. Although sifting fact from fiction is a bit more difficult these days. ConclusionThere are a number of other Progressive Era similarities to modern life - women's rights, environmental conservation, voting rights, and income inequality, to name a few - that I chose not to include in this list largely because they were less immediately relevant to the coronavirus pandemic. To learn more about food in World War I, check out my Bibliography page, which was links to lots of great books. I hope you enjoyed this read. It certainly helped me organize my thoughts around these similarities and I hope that we can learn from the successes and failures of the past. That's all any historian can hope. Thanks for reading. Stay safe, stay home. If you liked this post, please consider becoming a member or joining us on Patreon. Members and patrons get special perks like access to members-only content.

2 Comments

Janet Curley

4/8/2020 03:37:55 pm

Great job drawing parallels between eras.

Reply

4/8/2020 05:32:02 pm

Thank you, Janet! It's funny, sometimes I agonize over blog posts. This was not one of those times. With the exception of finding the citations for the military supply section, this post just spilled right out. I think it took me less than an hour to actually write the text. Glad you liked it.

Reply

Your comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

AuthorSarah Wassberg Johnson has an MA in Public History from the University at Albany and studies early 20th century food history. Archives

July 2024

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed