|

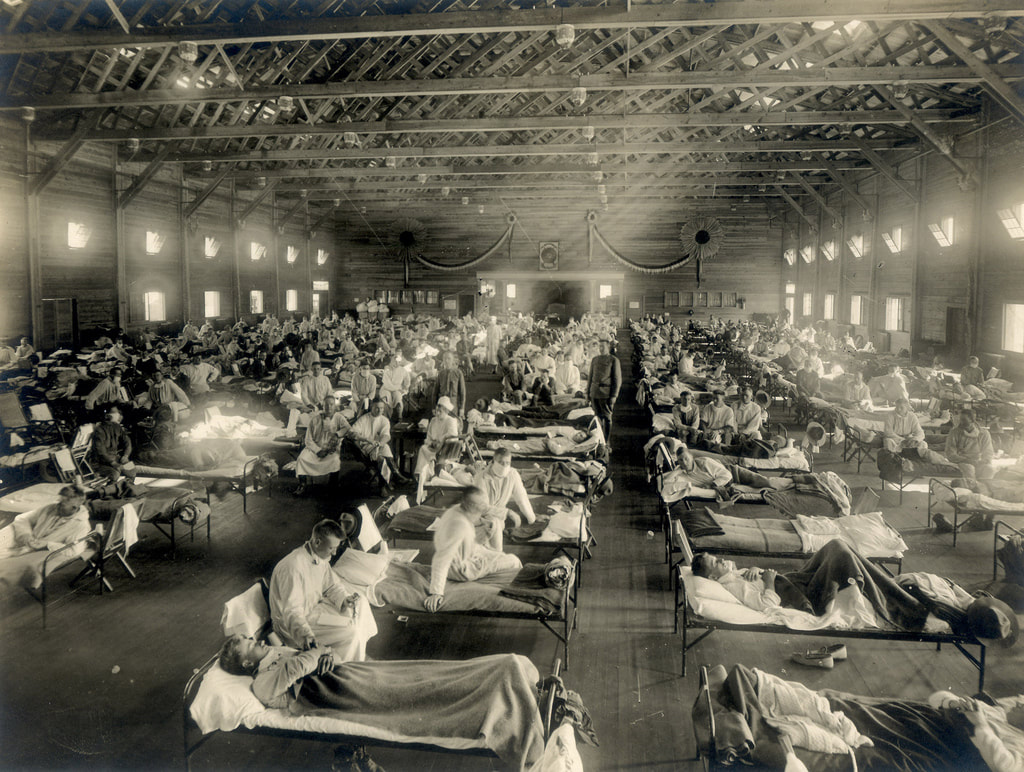

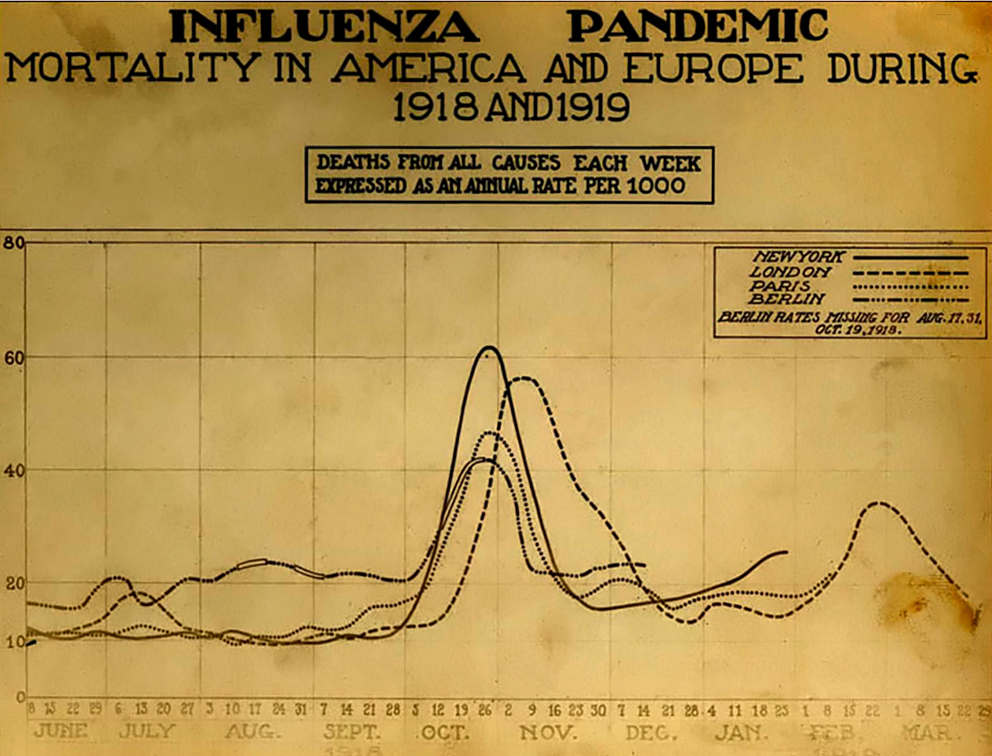

Given the prevalence of COVID-19 around the world, the comparisons to the influenza epidemic of 1918, and a reduction in my hours at work, I finally spent some time today familiarizing myself with the "flu." Folks, it wasn't pretty. The origins of what became known as Spanish Influenza is disputed, mostly because influenza mutates frequently, especially when humans are housed in close contact with animals. Some researchers claim British army camps in France, some claim Austria, some China, many as early as 1917. But one instance is believed to have occurred in Haskell County, Kansas, in January, 1918 (Barry, 110-112). It was a strange new version of the well-known influenza - violent coughing, nosebleeds, pneumonia, and in some cases, skin that turned so dark blue it was difficult to tell if a person was Black or White. And most concerning of all, the disease seemed to strike young, healthy people more than the typical infants or elderly. The influenza ran through crowded conditions during the very cold winter and spring in Army camps in Kansas, including Camp Funston, and then seemed to disappear. But it was spreading across the globe. In May, 1918, it reached Spain and sickened Alfonso XIII, the King of Spain. Unlike the United States and other European nations, Spain was politically neutral. And unlike its neighbors, who refused to reveal any sense of weakness that news of an epidemic might bring, Spain reported about this new strain of influenza in its newspapers. Hence the name, "Spanish flu." By August, 1918, a more virulent strain appeared in France, Sierra Leone, and Boston. By October the disease had become a global pandemic. The vast majority of those who died were under the age of 65. One theory as to why older people, who are typically first victims, would have been spared is that they may have developed immunity as young adults due to exposure to the "Russian flu," an influenza pandemic from 1889-1890. In addition, modern research has determined that the Spanish flu caused a violent immuno-response. The stronger the immune system, the more violent the response. Other factors in the high mortality rate may have included aspirin poisoning, as many of the worst death rates in the United States coincided with the US Surgeon General's recommendation that mega-doses of aspirin be used to treat the symptoms of influenza. Few public records of influenza remain, in large part because few were ever created. Like his counterparts in Europe, President Woodrow Wilson feared negative press and its impact on national morale. By the fall of 1918, he was determined to hammer home victory by sheer force. By that time, the American press, influenced by George Creel's Committee for Public Information and the threat of censorship law, published nothing Wilson wouldn't like. So few references to the influenza epidemic exist in newspaper references, it is almost as if it didn't happen. But happen it did. The public denial of a problem extended to government assistance as well. State and municipal governments were largely left to fend for themselves. The only real advice came from the Surgeon General: "Surgeon General’s Advice to Avoid Influenza

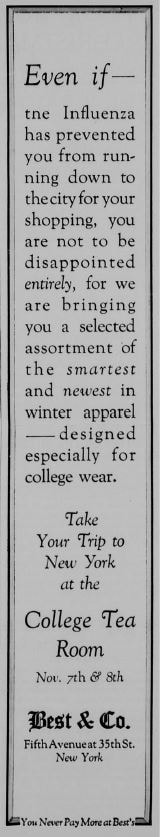

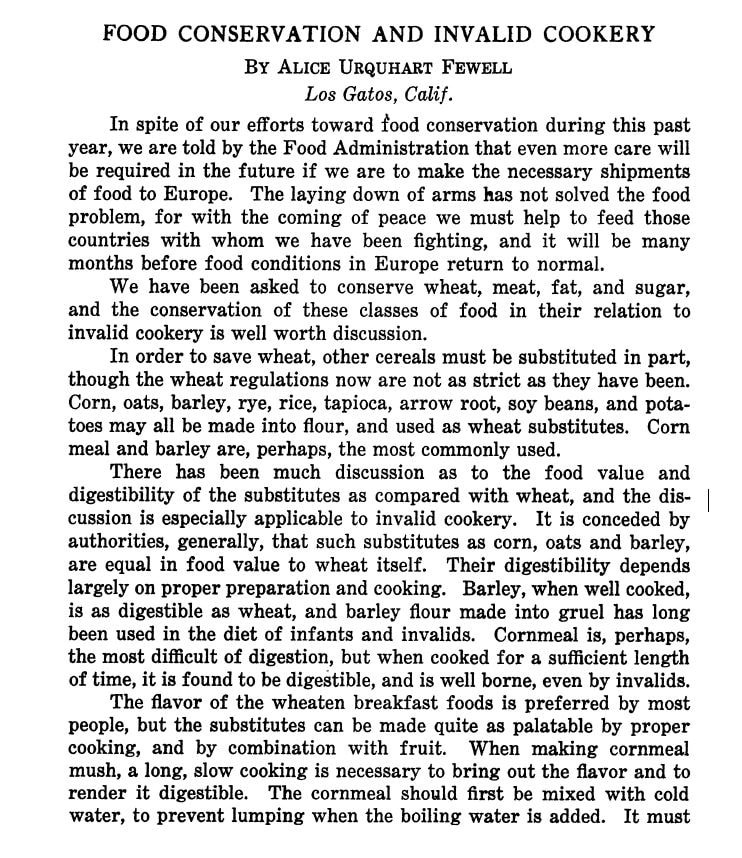

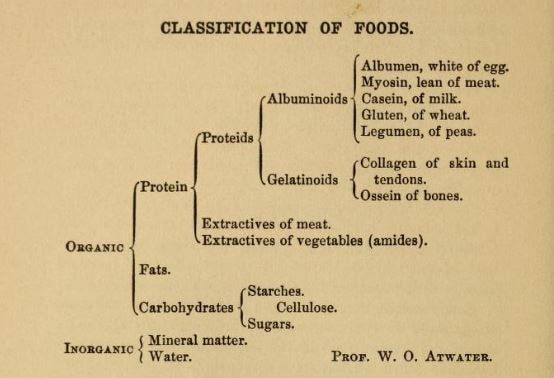

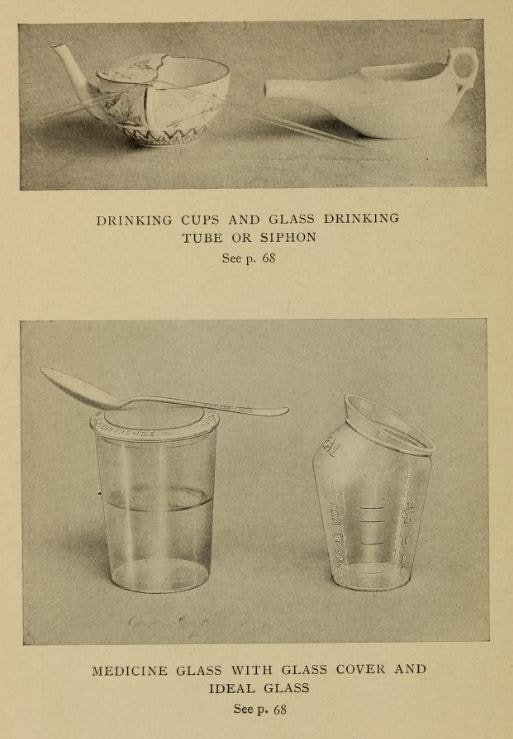

Many cities began to enforce the closure of public places. In recent news, the parable of Philadelphia and St. Louis have come up frequently. Philadelphia didn't shut down public spaces and in fact held an enormous parade, despite the risk. Within three days, people started dying. St. Louis, by contrast, took extraordinary measures to reduce crowds in public spaces, in the face of intense criticism, but had much lower infection and death rates. New York City, although the most populous city in the nation at the time, fared better than neighboring Philadelphia and Boston for two reasons. First, as the major maritime port for the whole Eastern seaboard, it started quarantining influenza cases as early as August, 1918. Second, the New York City Board of Health in early October recategorized influenza, allowing it to be reported as other infectious diseases. This allowed the city to monitor the situation and make decisions such as a staggered business schedule to reduce traffic on public transportation. On October 15, 1918, the New York Times published "Will District City in Influenza Fight," outlining how the city was to be divided up into districts for better organizing. That day, there was a meeting of the Emergency Advisory Committee, including Dr. Lee K. Frankel, who was at the meeting to represent social services organizations in the city. Of the plan to district, he said, "We shall try to find districts with a physical plant where cooking can be done, so as to supply families where there is illness, and the people are unable to care for themselves in connection with supplying food." This is one of the few indications of city-wide organization of cooked food for victims of influenza and its effects. But the pandemic did have a huge effect on the general population, not the least of which was orphaning children and leaving families without a breadwinner. From the 75th Annual Report of the New York Association for Improving the Condition of the Poor [what a name!]: “In handling the influenza epidemic, the report says, the association tackled one of the heaviest problems it has ever had to face in its seventy-five years. As an indication of the widespread effects of the disease the report points out that during the epidemic it cared for 355 families which had never before received aid from any relief organization. From Oct. 1 to March 1, the association took charge of 600 homes where influenza was prevalent. The work still continues. The association is spending $3,000 a month to care for families whose wage earners died during the epidemic. "In reviewing the year’s work, Bailey B. Burritt, the general director, in reference to the influenza epidemic said: “This has meant greatly increased drafts upon the energies of our nursing and visiting corps. It has meant many additional families which have had to be cared for, and some of these families will have to be cared for for many months because of the death of the breadwinner. It has meant the opening of an additional convalescent home for the after care of influenza cases. It has meant also greatly increased expenditures." At Vassar College, one of the Seven Sisters colleges where upper class white women attended, was also involved with pandemic relief efforts. In the November 27, 1918 issue of Vassar Miscellany News, the weekly(ish) Vassar campus newspaper, Helen Morton, Chairman of the General Service Committee of Christian Association, wrote an article entitled "The Epidemic That Was:" "Perhaps you remember? Yes, and the Poughkeepsie people probably do too! Poughkeepsie was well organized to meet the emergency and they were kind enough to let us help where we could. The College as a whole responded wonderfully. Old clothes fairly showered into the box in Main, mixed with toys for the orphans at Wheaton Park. Sheets monograms and all were sacrificed at a moment's notice. Hundreds of swabs and masks were made within half an hour; dozens of night gowns and a few layettes were made within a week. Six hundred odd dollars were collected in three days. One sick freshman even sent a generous contribution from the Infirmary for those who had influenza. With this money We were able to contribute to the support of the City Club "Kitchen." We were able to send food there every day: vegetables, cereals, orange juice, custards, etc.: we were able to help Miss Oxley with her splendid work in Arlington, to help the Associated Charities, and now we can start in on the reconstruction work with substantial support. The Associated Charities said—"It has given us the greatest pleasure to serve as stewards of the Vassar girls in the distribution of the comforts you gave us, and we are anxious to pass on to the owners the grateful thank- of the recipients." Members of the faculty helped us out in carrying things to and from town, and a few, willing martyrs, allowed their car- to be used for everything imaginable. In fact, everybody seemed willing to pitch in and work wherever they were given an opportunity. Was the college always so wonderful — or is the power to adapt ourselves to an emergency, which was so apparent during those trying weeks, one of the lessons of the Great War?" It's not clear why the article is written in the past-tense, as the pandemic continued for several months after November, but perhaps the worst was over in Poughkeepsie by that point. In the December, 1918 issue of Vassar Miscellany News, The Associated Charities of Poughkeepsie wrote a thank-you letter to "the young women of Vassar College," for their donation of $147.59, which was used to purchase food for needy families in the city for Thanksgiving dinner. Elsie Osborn Davis, General Secretary of the Associated Charities wrote, "Many of these families were either past sufferers or still convalescent from the influenza epidemic. *** In no instance where we gave was there an able-bodied man in the family. Households were either fatherless, or else the wage earner was hopelessly ill in hospital or sanitarium, or languishing in jail, or still convalescent from influenza." Although there is a fair amount of information about responses to the epidemic itself, and some references to the fact that food was needed or was delivered, very little is mentioned of what food was used for patients during this time. Cooking for patients at this time was generally called "invalid cookery" (invalids are sick people, rather than people who are not valid). Typical invalid cookery in the early 1900s was focused on soft, liquid, and/or easy-to-digest foods including beef tea and other meat broths, blanc mange and other milk-based puddings, eggs, and cooked cereals like farina (aka cream of wheat), oatmeal, and milk toast. In January, 1919, the American Journal of Nursing published an article titled, "Food Conservation and Invalid Cookery." Although the war officially ended in November, 1918, voluntary food conservation was urged well into 1919 to help feed the Allies - and defeated Germany - through the winter. Author Alice Urquhart Fewell, a home economist who specialized in invalid cookery, outlined how cooks may deal with rationing, including how to cook cornmeal instead of wheat cereals, to use chicken and eggs in place of beef and to avoid other protein substitutes as being too difficult to digest, and how to use sugar substitutes like honey, corn syrup, and maple sugar. In North Carolina, nurses and invalid cooks suggested that patients with fevers be fed an all-liquid diet, advice that was repeated elsewhere. In addition to beef or chicken broth, buttermilk, and malted milk, albumen water was also suggested. Albumen water is water mixed with raw egg white, and sometimes fruit juice, and served chilled. It was sometimes recommended as an alternative to milk for children. Gelatin was another popular suggestion for invalids as it was easy to swallow and gentle on the stomach. Perhaps the best-known resource available to women and nurses during the Spanish Flu epidemic was written by a very famous person indeed. In 1904, Fannie Merrit Farmer (yes, that Fannie Farmer) published "Food for the Sick and Convalescent." Farmer herself suffered a "paralytic stroke" as a teenager and was forced to drop out of school as she convalesced. She eventually relearned how to walk, though she walked with a limp for the rest of her life and used a wheelchair near the end of her life. Perhaps because of this, she became an expert in invalid cookery and was a frequent lecturer on the topic at the Harvard Medical School. Farmer's invalid cookery is very typical of the period, with its focus on broths and other fortified liquids, cooked grain dishes, eggs, custards, fruits and fruit juices, jellies (gelatin), and frozen desserts, with forays into meat, vegetables, and breads. What is unique about this cookbook is the amount of scientific material in it. Farmer's very first chapter starts in on the current, up-to-date nutrition science of the period, outlining information about essential minerals (we hadn't quite discovered vitamins yet) and listing a chart created by William O. Atwater, an influential nutrition science and the person who turned the calorie not only to use in nutrition science, but also into a household term. Today, we know that this chart isn't QUITE right, although it is on the right track. For instance, "albuminoids" is an old-fashioned term for what today are called "scleroproteins," such as collagen, elastin, and keratin - the insoluble structures of proteins. Farmer also discusses how the body absorbs and metabolizes proteins, fats, and carbohydrates. Her second chapter is all about calories, and even includes a math equation for how to determine the caloric values of any food. Her third chapter discusses digestion (a favorite topic of dyspeptic Victorians), and chapter four, which is quite short, puts forth the somewhat radical idea that eating wholesome food, well prepared, and plenty of rest, fresh air, and exercise were far more essential to good health - preventative medicine, if you will - than simply trying to correct existing diseases with drugs. This scientific approach is, of course, entirely on purpose. Not only was Farmer the kind of rigorous, exacting cook that gave us level measurements, she was also clearly extremely interested in nutrition science and wanted to share what she had learned with her thousands (if not millions) of readers. In part to convince them of her authority on the subject, but also I think to give women the tools they needed to care for their own families, or to pursue careers as nurses. Chapters five and six focus on the care and feeding of infants and children and it is not until chapter seven that we finally start to discuss the ideal diet for the ill, including pictures of some very interesting specialized dishware and glassware for feeding prone patients. Some of Farmer's recipes are not as typical as you might expect. For instance, in the chapter on milk (then considered a "perfect food" for its composition of proteins, carbohydrates, and fats), Farmer touts the benefits of koumiss, kefir, and matzoon - all fermented dairy beverages which Farmer claims are more digestible than straight milk. Which, to be fair, they probably were, not the least of which because the vast majority of milk available to Americans at this time was raw and unpasteurized. Even alcohol has a role to play in Farmer's cookery for the sick, and alcoholic beverages mixed with milk and/or eggs (milk punch, eggnog, hot cocoa with brandy are a few examples). Perhaps the most enduring advice from Farmer is that not only should food be digestible and healthy, it should also LOOK and TASTE good as well. A lesson that a lot of hospitals today could learn from. Fannie Merritt Farmer and other home economists and nutrition scientists were all part of the same movement that led American epidemiologists to try to innovate and find cures for pandemics like the Spanish Flu. The Progressive Era was a time when Americans were trying more than ever to understand the world around them and find ways to cure the physical and societal ills of a nation still dealing with the excesses of the Gilded Age. Although they met with varying success, and many of the upper middle-class white professionals leading the charge were far from perfect, they did make strides. The lessons of Spanish Flu were immediate. In New York City, on November 7, 1918, just days before Armistice, the New York Times published an article entitled "Epidemic Lessons Against Next Time." In it, New York City Health Commissioner Dr. Royal S. Copeland outlined the successes of the city's response, including the immediate quarantine of any cases arriving in the Port of New York by ship, which likely helped curb the introduction of influenza into the city. But most successful of all, perhaps, was the public-private partnership that resulted from the cooperation of private voluntary and relief organizations and city government. Including the mobilization of the Mayor's Committee of Women on National Defense, and its sub-committee on food, to organize food production and cooking for the designated district centers - often located in church basements or settlement houses - and the Automobile Committee, in which wealthy New York women used their automobiles to deliver the food to households in need. The Henry Street Settlement, founded and led by public health nurse Lilian Wald, was singled out in the article for special commendation. The Henry Street Settlement still exists today. The lessons of cooperation, faith in the scientific method, and reliance on experts are all important ones to remember today. As always, if you liked this post, consider becoming a member or joining us on Patreon. Members and patrons get special perks like access to members-only content.

7 Comments

Anna Katharine

4/2/2020 11:53:22 am

We think of early 20th-century invalid cooking as being completely outdated (we would never serve a sick person bread soaked in milk), but I think you can still see lingering traces. Jello is a prime example, as is chicken soup. It's fascinating to see what dishes hang on through the decades. :)

Reply

4/2/2020 09:26:10 pm

Isn't it funny? Makes you wonder why chicken soup and jello and oatmeal persist, but beef tea and blancmange haven't really, doesn't it?

Reply

Carla R Lesh

4/2/2020 02:43:34 pm

Wonderfully researched! Thank you for explaining a complicated topic so clearly.

Reply

4/2/2020 09:26:49 pm

Thank you so much, Carla! And what a delightful story about milk toast - thanks for sharing!

Reply

Carla R Lesh

4/2/2020 09:22:56 pm

I remember milk toast with cinnamon and sugar was something my great grandfather made for my grandmother and she made for me. My great grandmother was an early user of store bought bread. Horrified the neighbors, especially since she was a minister's wife.

Reply

Fran D

4/5/2020 09:55:01 pm

I was certainly fed lots of milk toast as a child. No cinnamon and sugar and no store bought bread. Salt and pepper and hopefully the milk was top milk (everybody knows what "top milk" is, of course).

Reply

4/5/2020 10:02:30 pm

Thanks for sharing, Fran! Did you enjoy it as a kid? Have you made it since?

Reply

Your comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

AuthorSarah Wassberg Johnson has an MA in Public History from the University at Albany and studies early 20th century food history. Archives

July 2024

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed