|

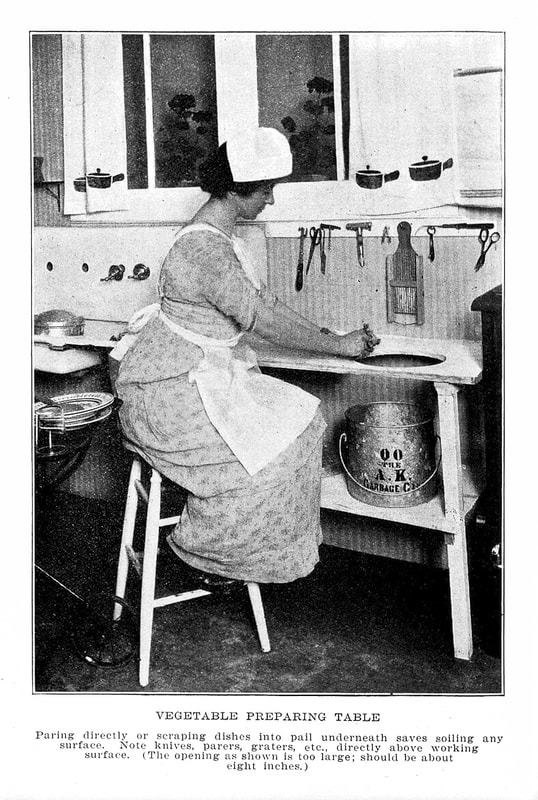

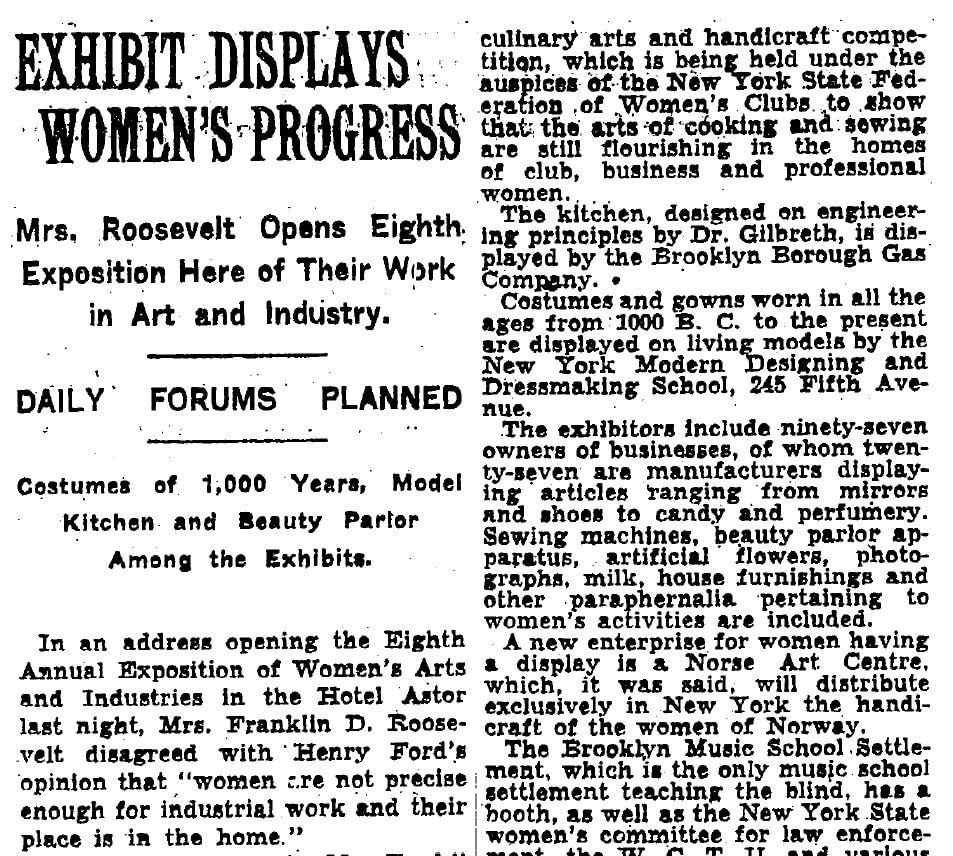

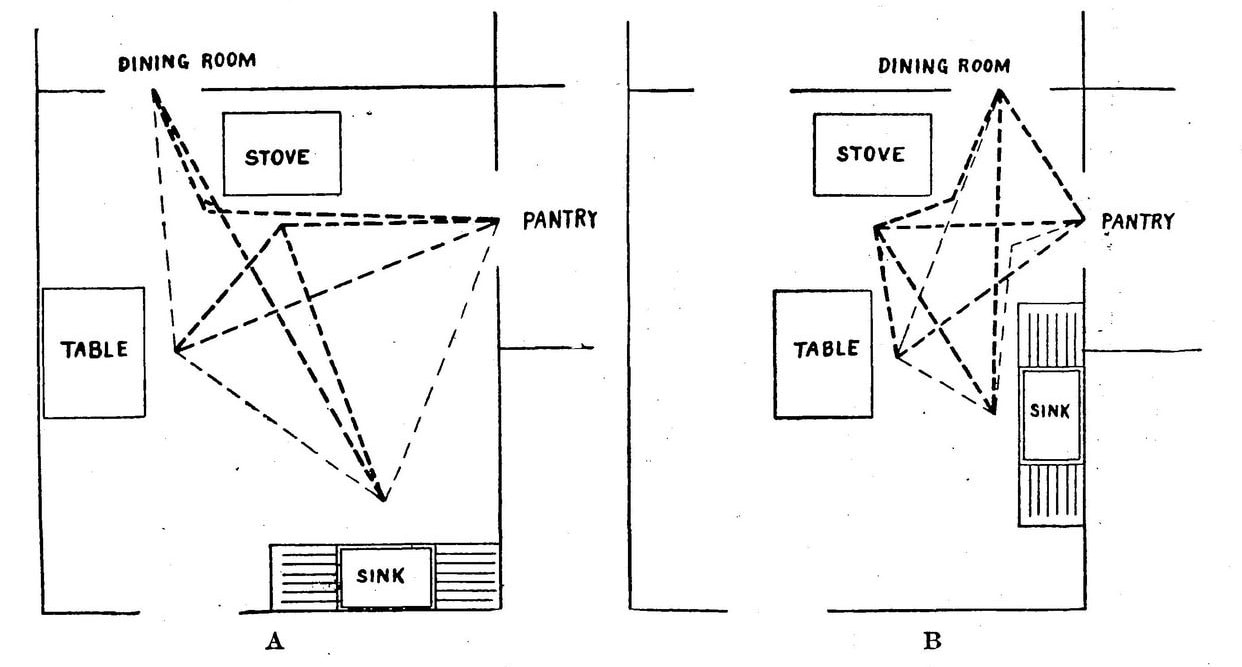

The other night I introduced a friend to one of my favorite YouTube videos ever. It’s a 1949 film put out by the United States Department of Agriculture’s Home Economics. You can watch the whole thing below: I love this film for a variety of reasons, but the primary one is how incredibly FUNCTIONAL this kitchen is. Not everything is perfect. The “messaging center” is too close to the stove for me – too able to collect splatters and grease from cooking. And the table, while nice, I think would have been better served by a more efficient built-in breakfast nook. But everything else? I LOVE IT. The storage is incredible. Everything is built with thought to use and efficiency. From the cooking and cleaning activities to the storage. And while the cabinets aren’t the prettiest, keep in mind that the design is meant to be built by farmers and handy homeowners – not professional contractors. Learn more about the film and the pamphlet for the Step-Saving Kitchen. This kitchen design is the culmination of several decades of work studies. During the Progressive Era, American interest in science began to increase, and scientific theories were applied to everything from factories to households. The Efficiency Movement was part of this application of scientific principles to everyday life. Led by mechanical engineer Frederick Winslow Taylor, the movement posited that everyday life, from industry to government to households, were plagued by inefficiencies, which wasted time, energy, and money. It also influenced the ecological conservation movement, a reaction to overuse of natural resources, and President Teddy Roosevelt was a known proponent. The movement, which became known as “Taylorism,” was hugely influential and spurred Progressive Era trust in experts and authorities that continued until the 1960s. Nowhere was Taylorism probably more influential than in the home economics movement, which advocated for efficiency in everything from nutrition to childrearing to household design. And that was thanks in part to the work of Christine Frederick, who in 1912 took Taylor’s principles and applied them to the household with a series of articles on “New Housekeeping” she wrote for the Ladies’ Home Journal. She started a Taylor-style efficiency laboratory in her own home kitchen and went on to publish several more books on the subject, including the 1919 Household Engineering: Scientific Management in the Home. Another influential advocate of household efficiency was psychologist Lillian Gilbreth. With her husband Frank Gilbreth, the two created a partnership to take Taylor’s ideas and apply them to industrial spaces, developing time-and-motion studies. Today, you might know them best as the parents who starred in the book (and subsequent films) Cheaper by the Dozen. After Frank’s untimely death in 1924, Lillian encountered discrimination in the engineering field, and began to turn her talents toward the domestic sphere. Partnering with Mary E. Dillon, president of the Brooklyn Borough Gas Company (and the first female utility president in America), Gilbreth and Dillon developed the kitchen work triangle, which advocated for a step-saving triangle between sink, stove, and refrigerator. Part of Gilbreth’s Practical Kitchen, the new design was revealed at the Eighth Annual Exposition of Women’s Arts and Industries on October 1, 1929. Eleanor Roosevelt was one of the speakers. Many of these principles were adopted by government organizations like the USDA. As early as the 1909, with the federal government’s Country Life studies, the plight of farm women and their poorly designed, technology-lacking kitchens came to light. The USDA’s Farmer’s Bulletin No. 607, “The Farm Kitchen as Workshop,” published in 1921 by Anna Barrows, outlined some of the concerns about kitchen efficiency and how to correct them. Page 10 of the bulletin illustrated the difference in closing the distances between workspaces – a star shape similar to the kitchen work triangle resulted. Several Congressional Acts brought federal funding to these studies. The Smith-Lever Act of 1914 mandated home economics instruction at land grant colleges. The Purnell Act of 1925 allocated federal funding into vitamin research and research of rural home management. These types of studies flourished under the federal funding and in my opinion placed overdue emphasis on the safety, sanitation, comfort, and efficiency of the home. All of these efficiency studies contributed to the result of the 1949 kitchen I love so much. But what happened? Why do modern kitchens seem to ignore the best research of the past? Today, there is far less government investment in domestic study – either from the USDA or public universities. The USDA’s Bureau of Home Economics was shuttered in 1962. Some of its personnel were shifted to the Nutrition and Consumer-Use Research department under the auspices of the USDA’s Agricultural Research Service. Some consumer-based research regarding food was absorbed by the FDA. But the kitchen research seems to have largely been abandoned. Some universities, like at Cornell, have continued to offer household design programs as subsets of architectural programs. But the federal funding is gone. Which is a shame, because our household lives seem to have suffered for it. One rule that has been adopted most widely is the kitchen work triangle. But not always. For instance, my kitchen doesn’t have one – the refrigerator, stove, and sink are all in a line. The only triangle is that my primary work surface is on the other side of my galley kitchen. And don’t even get me started on the ergonomics of storage. Those seem to have been discarded wholesale. One ray of light has been the resurgence of roll-out shelves. But even these are few and far between, likely because they are more expensive than traditional fixed shelving. And yes, dear reader, here, I think, is the rub – efficient kitchens must be custom designed. And in our cookie-cutter, prefab world, both design and customization are expensive. In addition, many of today’s kitchens are designed more for show, or occasional entertaining, rather than daily life. Which is an unfortunate reflection of how many Americans cook (or don’t). Case in point: the disappearance of the pantry – the one final thing that 1949 kitchen doesn’t have (it’s presumably in the cellar in the film) that I’d want. At any rate, if I ever win the lottery, you know what kind of kitchen I’ll be building. What aspects of the 1949 Step-Saving Kitchen did you like best? What would your dream kitchen look like? Sources & Further Reading

The Food Historian blog is supported by patrons on Patreon! Join us for awesome members-only content like free digitized cookbooks from my personal collection, e-newsletter, and even snail mail from time to time!

1 Comment

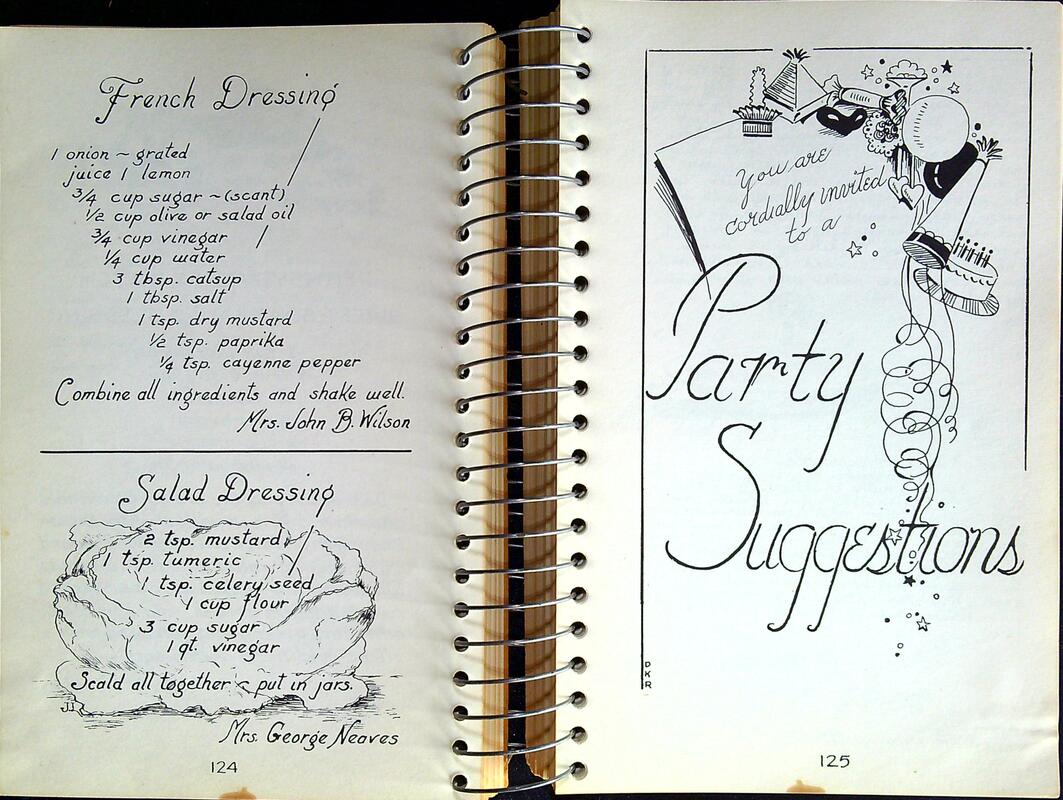

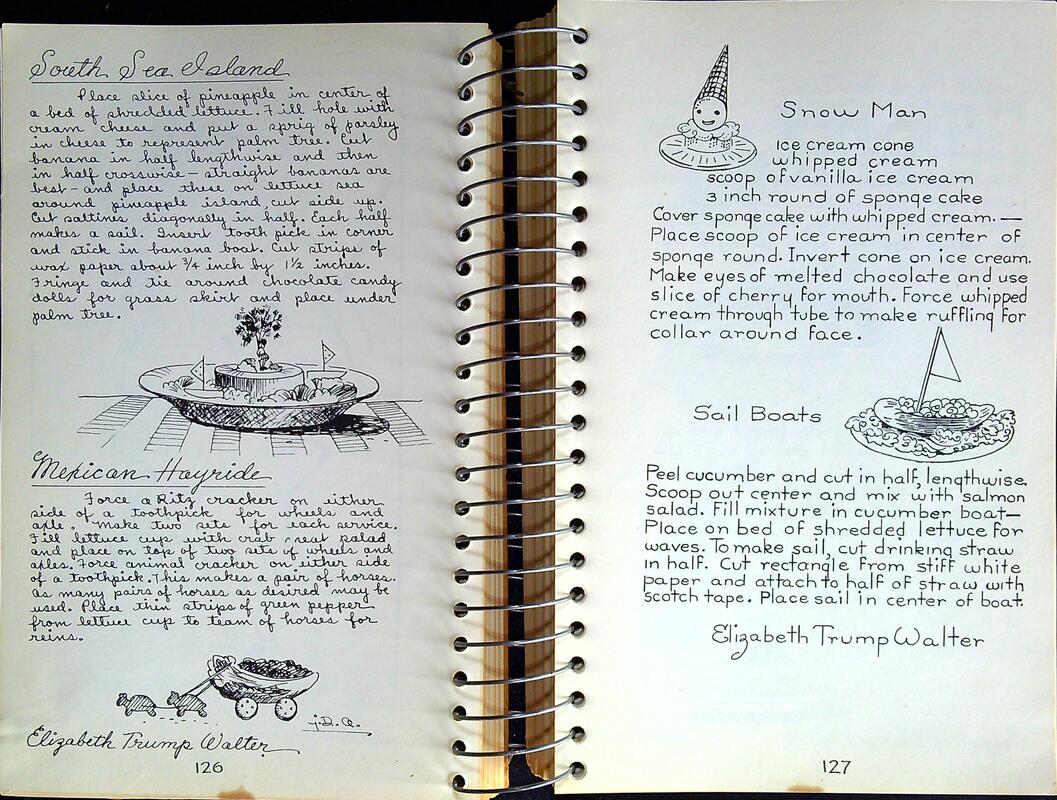

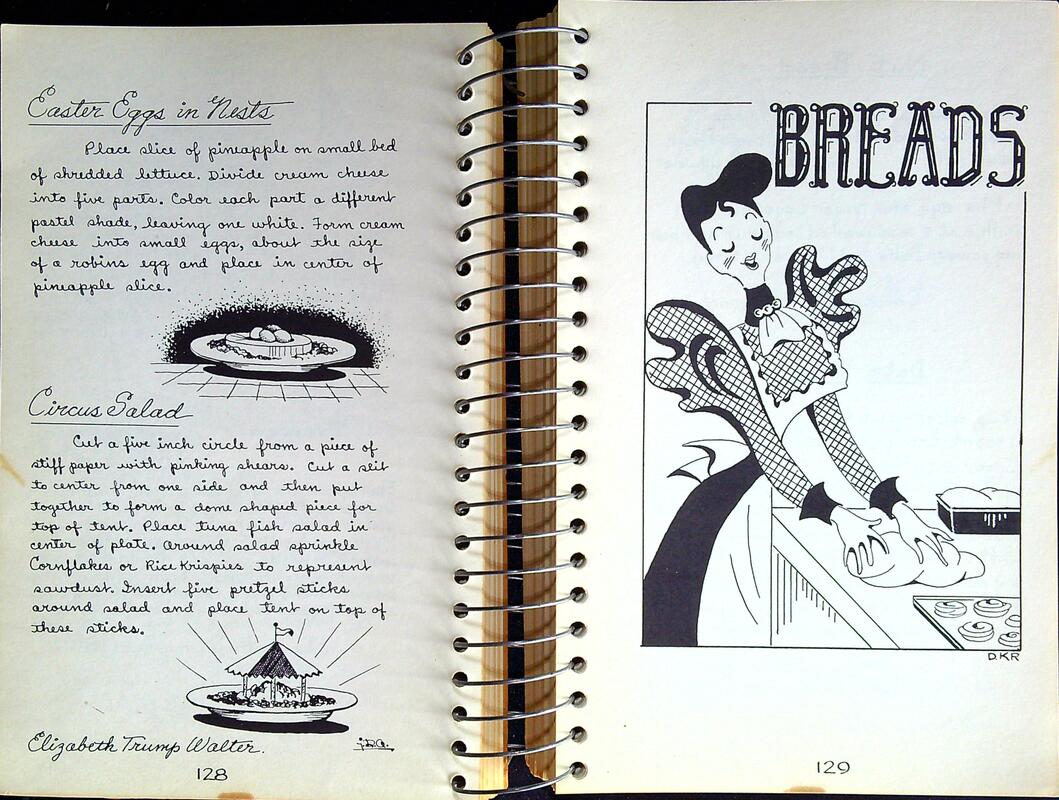

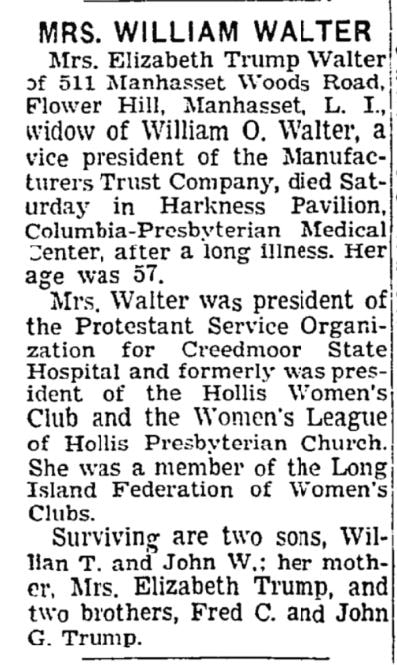

In 1946 the Women's League of the Hollis Presbyterian Church in Hollis, NY published this community cookbook, Hollis Pantry Secrets. Hollis is a neighborhood in Queens County, NY and in the 1940s was a relatively new development of single-family homes that had only been part of New York City since 1898, when it was developed from rural farmland. I was in the process of digitizing the cookbook when I ran across a somewhat familiar name. "Elizabeth Trump Walter." Could it be? Was she related to President Donald Trump? I started digging, but sadly, there wasn't much to find. Elizabeth was born in 1904 to Elizabeth Christ and Frederick Trump (Sr.), German emigrants to the United States. Frederick (sometimes spelled Friedrich) had made his fortune during the Gold Rush with a hotel specializing in alcohol and suites for prostitutes. He returned to Germany in sometime before 1902, only to run into trouble with the authorities, who deemed his emigration illegal because he had not completed his military service. He met and married Elizabeth Christ in 1902 and they moved to New York City. In 1904, homesick Elizabeth convinced him to return to Germany, but due to Frederick's trouble with the authorities over his lack of military service, they could not stay, and returned to New York City in 1905. It is unclear if Elizabeth the younger was born in Germany or not. Her younger brother Frederick Jr. was born in 1905 and John in 1907. Frederick Trump Sr. died of Spanish Influenza in 1918, and the family was soon in trouble financially. Elizabeth Christ Trump decided to continue her husband's work in real estate development, and that her children would be her primary employees. Elizabeth the younger was also the eldest child - she left high school to attend secretarial school so that she could be the accountant for the newly formed E. Trump and Son company. Her youngest brother John was to be the company architect. Fred Jr. the builder. John left the company early on and Fred Jr., with his mother, built E. Trump and Son into a real estate empire. Derailed by the stock market crash of 1929, when E. Trump and Son officially went out of business, by 1934 Fred Jr. managed to finagle his way into a mortgage-servicing contract, and the Trumps were back in the real estate business. The rest is fairly well-known history, including Trump's housing discrimination. But what about Elizabeth? Her history is almost non-existent. She has no Wikipedia page. She isn't even mentioned on her mother's Wikipedia page, despite the fact that Fred Jr. is noted as the "second child" and John the "third." She is mentioned on the Trump family page. We know she married William Walter, who was training to work in a bank, in June of 1929. According to William's 1959 obituary, he was a veteran of World War I who had worked in banks starting as a page boy in 1910. The year he and Elizabeth were married, he was made assistant secretary of the newly formed Manufacturer's Trust. Elizabeth apparently continued in her accounting role after marrying William, but it is unclear whether she left in late 1929 when E. Trump and Son went under, and whether she continued to work under Fred Jr. Elizabeth and William Walter had two children - William Trump Walter, born in 1931, and John Whitney Walter, born in 1934. Both Elizabeth and William Sr. were highly involved in the Hollis Presbyterian Church. He was an elder, she, a member of the Women's League. So it makes sense that Elizabeth would submit recipes for the 1946 cookbook. Here are her recipes: The "Party Suggestions" that start on page 125 is a small section that only contains recipes from Elizabeth Trump Walter! All variations on starter salads (with one exception), probably for ladies' luncheons, but possibly also for themed dinner parties, or even children's parties. South Sea Island Place slice of pineapple in center of a bed of shredded lettuce. Fill hole with cream cheese and put a spring of parsley in cheese to represent palm tree. Cut banana in half lengthwise and then in half crosswise – straight bananas are best – and place these on lettuce sea around pineapple island, cut side up. Cut saltines diagonally in half. Each half makes a sail. Insert tooth pick in corner and stick in banan boat. Cut strips of wax paper about ¾ inch by 1 ½ inches. Fringe and tie around chocolate candy dolls for grass skirt and place under palm tree. Mexican Hayride Force a Ritz cracker on either side of a toothpick for wheels and axle. Make two sets for each service. Fill lettuce cups with crab meat salad and place on top of two sets of wheels and axles. Force animal crackers on either side of a toothpick. This kames a pair of horses. As many pairs of horses as desired may be used. Place thin strips of green pepper from lettuce cups to team of horses for reins. Snow Man Ice cream cone Whipped cream Scoop of vanilla ice cream 3 inch round of sponge cake Cover sponge cake with whipped cream. – Place scoop of ice cream in center of sponge round. Invert cone on ice cream. Make eyes of melted chocolate and use slice of cherry for mouth. Force whipping cream through tube to make ruffling for collar around face. Sail Boats Peel cucumber and cut in half, lengthwise. Scoop out center and mix with salmon salad. Fill mixture in cucumber boat – Place on bed of shredded lettuce for waves. To make sail, cut drinking straw in half. Cut rectangle from stiff white paper and attach to half of straw with scotch tape. Place sail in center of boat. Easter Eggs in Nests Place slice of pineapple on small bed of shredded lettuce. Divide cream cheese into five parts. Color each part a different pastel shade, leaving one white. Form cream cheese into small eggs, the size of a robins egg and place in center of pineapple slice. Circus Salad Cut a five inch circle from a piece of stiff paper with pinking shears. Cut a slit to center from one side and then put together to form a dome shaped piece for top of tent. Place tuna fish salad in center of plate. Around salad sprinkle Cornflakes or Rice Krispies to represent sawdust. Insert five pretzel sticks around salad and place tent on top of these sticks. Her six party suggestions make up the entire "Party Suggestions" chapter. I, personally, would have a hard time cutting saltines in half or forcing toothpicks into crackers, so clearly this sort of thing took a great deal of finesse. Elizabeth Trump Walter died on December 4, 1961, at the age of 57, "after a long illness," just two years after her husband William. Her obituary is on page 37 of that day's New York Times, towards the bottom. She pre-deceased her mother Elizabeth Christ Trump by five years. Ironically, Elizabeth Christ Trump does not have an obituary in the New York Times, she is only listed among the deaths recorded on June 9, 1966 - her notice submitted by the Federation of Jewish Philanthropics. According to Elizabeth's son John Walter's 2018 obituary, the Walters moved to Manhasset, NY toward the end of their lives. They lived in a retirement home built by the Walters and likely Fred Trump, Jr., but died just a few years later. John begun attending the Congregational Church of Manhasset at his mother's behest. Elizabeth Trump Walter was memorialized with a restored organ at the Congregational Church of Manhassett, NY sometime in recent years. Elizabeth Trump Walter rarely shows up in Trump family histories, probably because of her early death compared with the Trump family fortunes. But it was a fascinating project to track down what I could about her. The Hollis Pantry Cook Book has more secrets and famous recipe authors to share, so stay tuned for future blog posts. Have you ever found a famous person's name in a community cookbook? Tell us in the comments! The Food Historian blog is supported by patrons on Patreon! Join us for awesome members-only content like free digitized cookbooks from my personal collection, e-newsletter, and even snail mail from time to time!

Thanks to everyone who joined us live for Food History Happy Hour! We made the 1917 Belmont Cocktail and chatted about January holidays, including the Russian/Soviet Novy God, Twelfth Night, the Swedish Tjuegondag Knut, Robbie Burn's Day, random National Food Holidays, including National Fig Newton Day (today!), National Peanut Butter Brittle Day (my birthday!), and how on earth all those National whatever days got to be decided. Plus, since my birthday is coming up, we discussed birthday history and birthday cake history, as well as some general cake history.

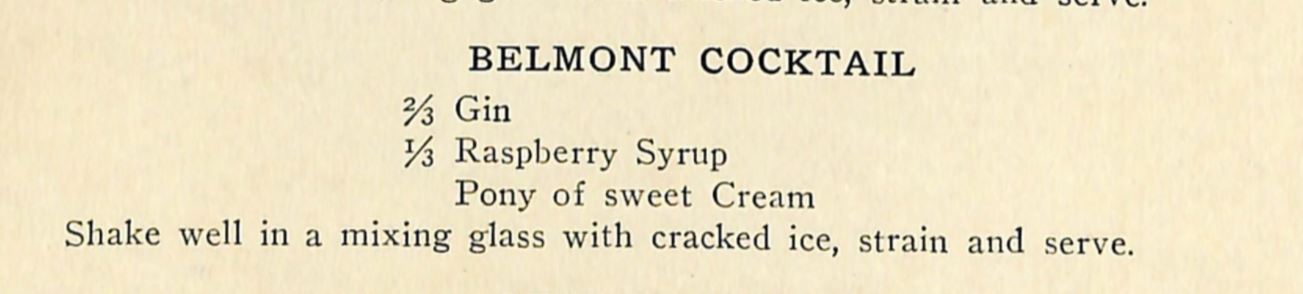

Belmont Cocktail (1917)

As those of you who have been following Food History Happy Hour for some time know, I often end up making pink drinks accidentally. But this time, in honor of the new year, and my upcoming birthday, I went looking for something that would be specifically pink! And the Belmont Cocktail came to mind. It's featured in Recipes for Mixed Drinks by Hugo R. Ensslin, published in 1917 and one of my favorite cocktail recipe books.

The directions aren't super clear. For instance, 2/3 of WHAT of gin? But I've decided that this is likely a ratio - 2 parts gin to 1 part raspberry syrup, and given that the sweet cream measurement is a pony (1 ounce, usually the other side of a jigger, which is 1.5 ounces), here's what I decided to use. 2 ounces gin 1 ounce raspberry syrup 1 ounce cream Shake with ice, strain, and serve in a pretty cocktail glass. Garnish with a fresh or frozen raspberry if you are so inclined. Sadly, this drink was NOT very good. I've since looked up other recipes, which say to use 2/3 of a GLASS of gin and 1/3 of a GLASS of raspberry syrup, which sounds like way too much. I found that while gin and raspberry probably would have been nice together, and raspberry and cream are definitely delicious, the gin was just too overpowering in this cocktail. It would have been much better as a gin fizz with cream. The addition of club soda or seltzer would have smoothed out the flavors. I think this was probably my least drinkable cocktail ever for Food History Happy Hour! I was so sad, especially since I had such high hopes. SIGH. Must have been my ratios were off, but even other published recipes, it seems like way too much gin and syrup. Oh well. I'll have to track down something more palatable for February! Episode Links

The Food Historian blog is supported by patrons on Patreon! Join us for awesome members-only content like free digitized cookbooks from my personal collection, e-newsletter, and even snail mail from time to time!

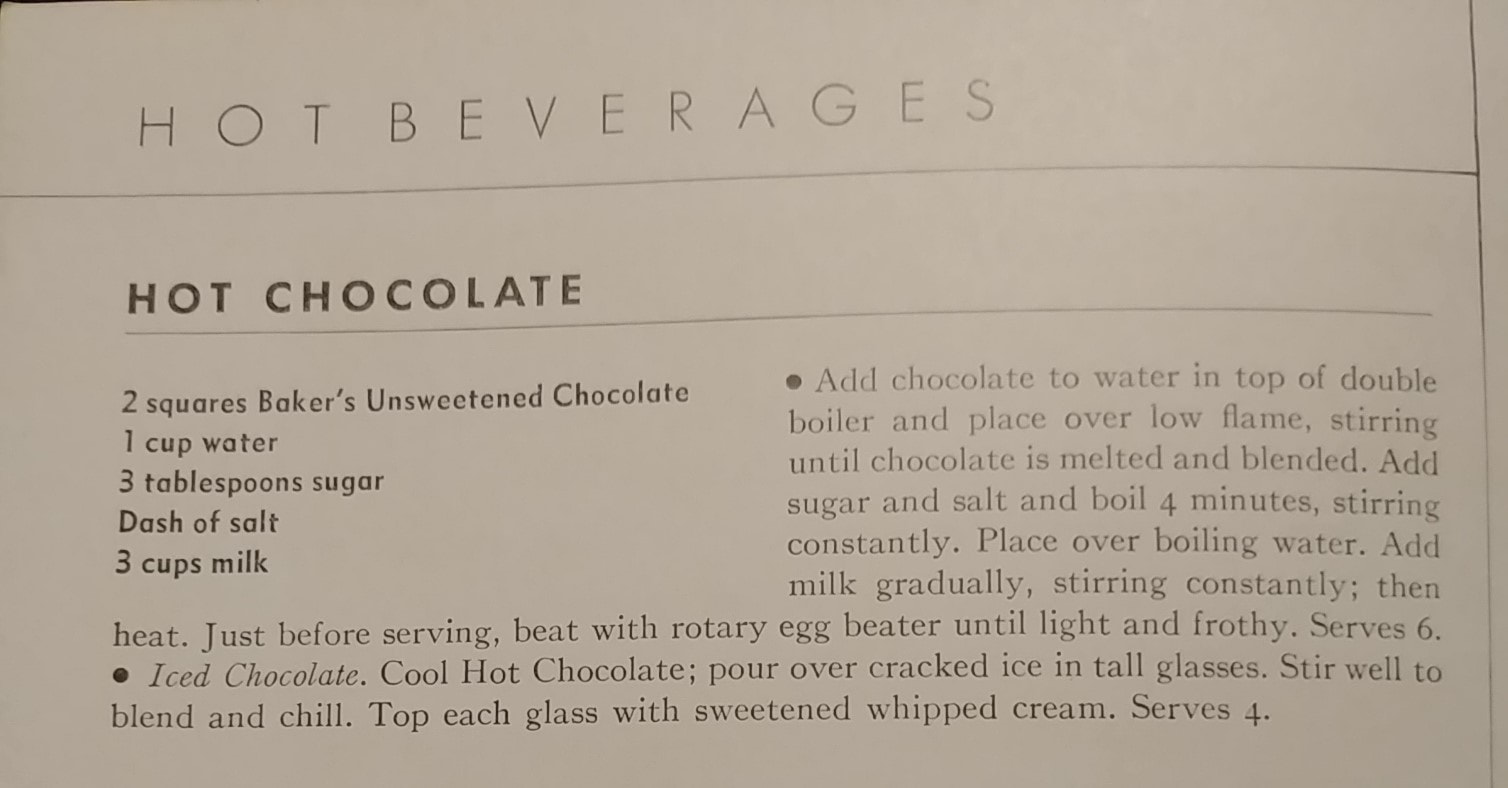

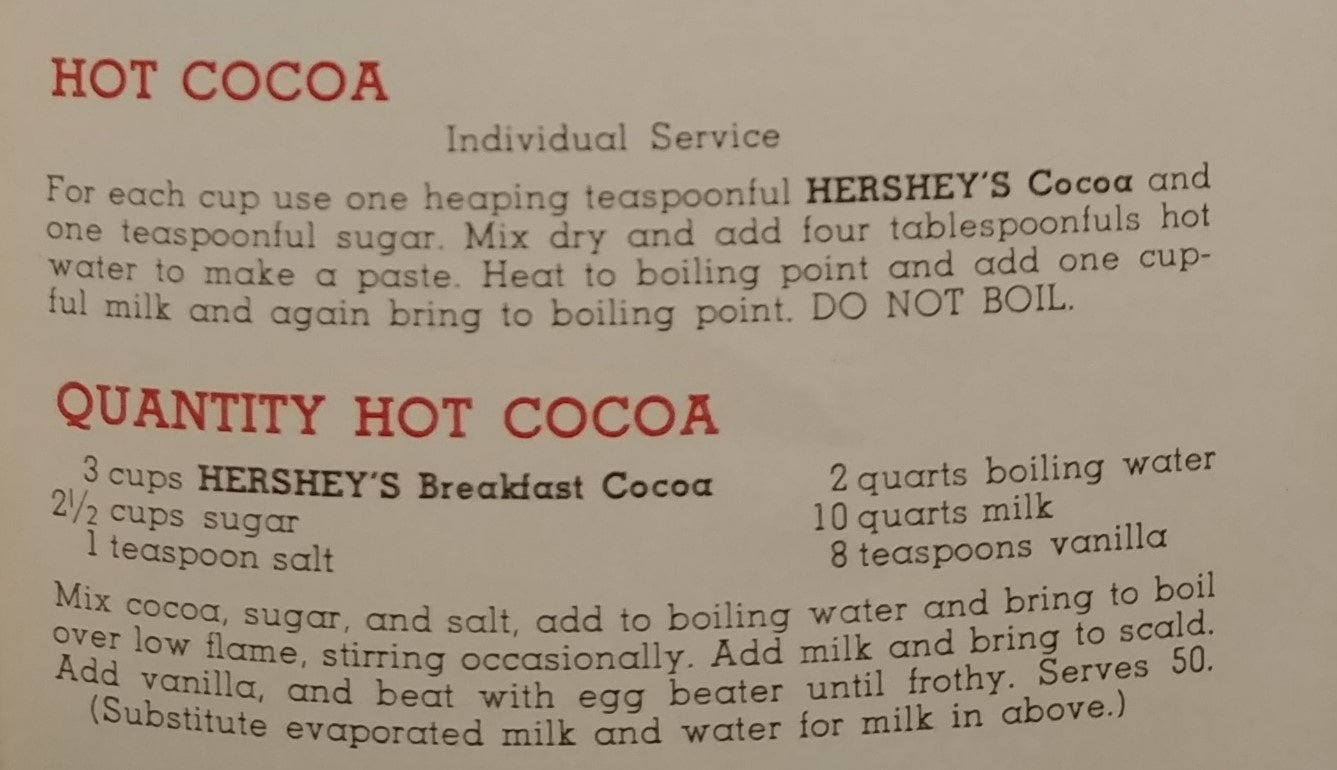

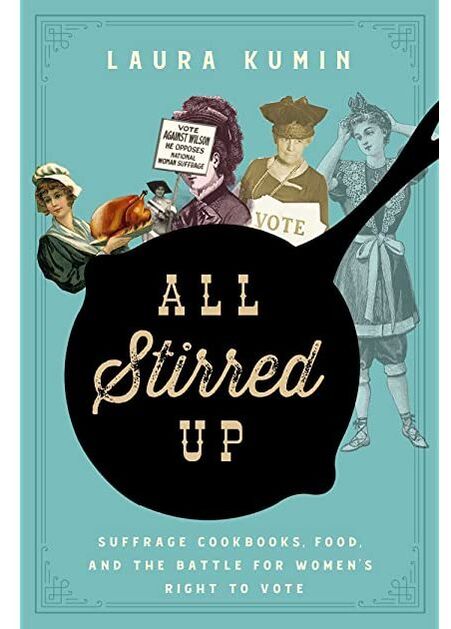

In the United States, the terms "hot chocolate" and "hot cocoa" are used pretty interchangeably, but they aren't quite the same thing! Hot ChocolateHot chocolate is a truly ancient drink, dating back as many as 3000 years. Developed by ancient Indigenous people in Mesoamerica, the cacao bean was used by the Olmecs and drinking chocolate perfected by the Maya and Aztecs. A mixture of ground roasted cacao beans, spices, including chili peppers and vanilla, sometimes sweetened with honey, and often containing other ingredients, including ground maize and cochineal to color it red, early drinking chocolate was frothed into a foam and consumed as part of religious ceremonies. In the late 16th century, Spanish invaders had brought cocoa beans - and drinking chocolate - back to Spain, where it quickly spread throughout aristocratic Europe. It came to colonial America via Europe in the late 17th century, where cocoa processors started importing direct from Central America and the Caribbean. Hot chocolate became a fashionable breakfast beverage. But how was it made? Processed cocoa beans were fermented in the pulp, then dried, then roasted. Chopped into nibs, they were then stone ground to create a chocolate paste. Mixed with sugar, hot water, and spices, the bitter drink was served with cream and sugar, much like coffee or tea. By the 18th century, cakes of processed chocolate were being produced for transformation into drinking chocolate. In the mid-19th century, cocoa butter and sugar were added to the cacao and through conching and tempering, eating chocolate developed. By the Victorian period, hot chocolate had transformed from a popular adult beverage on par with coffee and tea, to the purview of children. Hot CocoaPart of the shift from breakfast beverage of aristocrats to children's treat had to do with the fact that both cacao and sugar were increasing in production and therefore dropping in price throughout the 19th century. Cocoa production expanded to other equatorial areas besides Mesoamerica and sugar, fueled by slavery and technological advances, also increased in production. The development of cocoa powder in the 1820s helped expand access to chocolate. Cocoa powder is created by melting or pressing the cocoa butter out of the nibs, then drying and grinding the defatted cocoa beans. Lighter weight, more shelf stable, and easier to blend into beverages than drinking chocolate, cocoa powder became the main ingredient in hot cocoa recipes. Most cocoa powder was natural process, like Hershey's, meaning that it was dried and ground after the Broma process of defatting. But some cocoa powders (like Fry's) were Dutched, or created using the Dutch process, which meant that the defatted cocoa nibs were immersed in an alkaline solution to help neutralize some of their natural acidity before being dried and ground. Natural cocoa is reddish brown in color - Dutch process color is a dark grayish brown. So there you have it! The difference between hot chocolate and hot cocoa is that one is made from melted cocoa, usually 100% cacao unsweetened chocolate, and hot cocoa is made from a mixture of cocoa powder and sugar, often cooked into a syrup. But how do you know which one you prefer? Hot chocolate or hot cocoa? Try these historic recipes and find out! Baker's Hot Chocolate Recipe (1936)I made this recipe as part of a talk on hot chocolate history, and while not very sweet, it is very rich and chocolatey. If you are a chocoholic, this is the recipe for you. Please note that you'll need Baker's Unsweetened 100% Cacao Chocolate, and that these days 2 squares is really 2 ounces, or 8 quarter ounce rectangles. 2 squares Baker's Unsweetened Chocolate 1 cup water 3 tablespoons sugar dash of salt 3 cups milk Add chocolate to water in top of double boiler and place over low flame, stirring until chocolate is melted and blended. Add sugar and salt and boil [over direct heat] 4 minutes, stirring constantly [this will boil off most of the water and make a thick syrupy chocolate]. Place over boiling water, add milk gradually, stirring constantly; then heat. Just before serving, beat with rotary egg beater until light and frothy. Serves 6. Hershey's Single Serve Hot Cocoa Recipe (1937)For each cup, use one heaping teaspoonful HERSHEY'S COCOA and one teaspoonful sugar [I used a heaping spoonful, which it needed]. Mix dry and add four tablespoons hot water to make a paste. Heat to boiling point and add one cupful milk and again bring to boiling point. DO NOT BOIL. You can use either natural process or Dutch process cocoa for this one. It is not as thick and rich as the Baker's hot chocolate, but it does have that familiar cocoa taste from childhood and is still quite good. You can always change these recipes to suit your tastes with more sugar or with half and half or part cream, instead of all milk. Top with whipped cream, marshmallows, or try your hand at Indigenous-inspired spices like chili powder, cinnamon, vanilla, etc. You can also substitute almond milk (the most historical substitution, since almond milk was known in 16th century Europe), or any other non-dairy milk. Which do you prefer, hot chocolate or hot cocoa? And how do you like yours prepared? I like mine extra-creamy with whipped cream. Maybe a little peppermint or salted caramel syrup if I'm feeling extra-indulgent. Share your perfect cup in the comments! These recipes are part of a talk with cooking demonstration on the history of hot chocolate I do for public events. For upcoming programs, visit my Event page. The Food Historian blog is supported by patrons on Patreon! Join us for awesome members-only content like free digitized cookbooks from my personal collection, e-newsletter, and even snail mail from time to time! This article contains Amazon.com and Bookshop.org affiliate links. If you purchase anything from these links, The Food Historian will receive a small commission. All Stirred Up: Suffrage Cookbooks, Food, and the Battle for Women’s Right to Vote, Laura Kumin. New York: Pegasus Books, 2020. 357 pp., $28.95, hardcover, ISBN 978-1-64313-452-9. ,I first learned about cookbooks associated with women’s suffrage thanks to this Atlas Obscura article and I was instantly fascinated. Feminism in the 20th century was often more interested in throwing off the chains of household drudgery than with enticing converts through snacks. But that is precisely the premise of All Stirred Up: Suffrage Cookbooks, Food, and the Battle for Women's Right to Vote, which is why I was so excited that I put it on my Christmas wish list. I was expecting a thorough examination of the suffrage cookbooks, the women who created them, and their place in the movement. Sadly, as a book, All Stirred Up is like an underdone cake – it looks perfect on the outside, but the inside is doughy and disappointing and could have used another 30 minutes in the oven. Laura Kumin is a former lawyer turned cooking educator and food writer. She does not have a historical background, and, as is the case with many non-historians who write food history, it shows. All Stirred Up begins, even before the introduction, with a lengthy timeline. While I find timelines to be incredibly useful, especially when dealing with complex chronology, starting the book with one was not a choice I would have made. It is confusing to the reader, who is presented lengthy and disparate facts without context or introduction. A lack of context is a theme for the book. Kumin’s introduction is part explanation of her interest in suffrage cookbooks and part layout of her main argument. She makes a compelling case that modern takes on suffrage history have largely ignored the role of cookbooks in converting skeptics to the cause. Unfortunately, this argument is not often revisited in the subsequent chapters. Most of the chapters are quite brief, some as few as eight pages, and while historical overviews abound, actual analysis is lacking. Taking up the most space are the recipe sections that follow each chapter, organized by type. Although these recipes are directly taken from the suffrage cookbooks, with modern adaptations designed by Kumin, there is no context for any of the recipes and no dates listed. Most recipe sections draw from multiple suffrage cookbooks without differentiating between them, beyond noting where the originals came from. We do not know why Kumin chose these particular recipes, how they reflected the cookbooks and times from whence they came, or even what, if any, relevance they had to the suffrage movement. For many chapters, the number of pages devoted to recipes outweigh the pages devoted to history. As for the history itself, most of it is shallow summaries meant to orient the reader to the basics of suffrage history, home economics and food science, and basic culture of the period. While this context is useful for non-historians, it seems to come at the expense of historical analysis. In addition, the chronology of the book is all over the place. The book begins in 1848, with an exercise in “time travel” in which Kumin writes in the present tense. Then zooms ahead to the Progressive Era and back again several times. At the end of Chapter 3, we’re already at the 19th Amendment in 1920, an achievement which is not really revisited for the rest of the book. Throughout the book, the suffrage movement in one decade is conflated with the same movement decades later. Little attention is paid to the context of national culture on the way in which the women's suffrage movement was operated, despite the fact that it was under operation, in one way or another, for over 70 years. Missed opportunities to make connections to other major movements, including abolitionism, Temperance (which is dismissed as detrimental to the cause, p. 78-79), Progressive reform, government regulation, etc., abound. Chapters 3, 4, and 6 are the strongest, content- and argument-wise. In Chapter 3, “From Seneca Falls to the Ballot Box,” Kumin examines the suffragists themselves and the post-Civil War resurgence of the movement. To her credit, she makes a point of mentioning African American suffragists and their shameful treatment by mainstream white suffragists, as well as male allies and the “antis” – anti-suffragists. However, points that needed more analysis were often presented as literal sidebars in the text. For instance, noted suffrage ally Frederick Douglass, instead of being included in the main text, receives a short summary in a gray box. The Beecher family get similar treatment in a sidebar about how the movement split families. Catharine Beecher, a fervent anti-suffragist, was a cookbook author and young women’s educator of some renown and who, despite conflicting ideas about suffrage, nonetheless co-wrote The American Woman’s Home with her suffragist sister. Cookbook author, fervent abolitionist, and Native American rights activist Lydia Maria Child is mentioned in a quotation, but otherwise ignored. These are just a few of many missed opportunities to engage with the subject matter more deeply – discussing how both suffragists and “antis” used women’s work and the home in their arguments for and against suffrage. Chapter 4, “We Can Peel Potatoes and Fight for the Vote, Too! Suffrage Strategies and Battle Tactics” is the strongest chapter in the book, and one of the few that cites primary sources in the endnotes. Discussing the divergent tactics between “mainstream” and “militant” suffragists, Kumin compares the mainstream work of the cookbooks, cafeterias, the “doughnut campaign,” a “Pure Food” storefront, and cooperating with agricultural extension, to the militant tactics of parades, protests, arrests, and hunger strikes. Unfortunately, she does not define who exactly is “mainstream” and who is “militant,” except to note differing tactics. Kumin argues that the more mainstream feminists were more successful in changing hearts and minds, but presents little evidence to back up this claim. In addition, despite covering the bulk of the Progressive Era, the chapter mentions, but gives little context to agricultural extension, the Temperance movement, home economics, World War I, and women’s clubs. An overview of home economics and food science comes in the following chapter, “Revolution in the Kitchen.” Chapter 6 finally addresses the cookbooks themselves, with an overview of how they were financed, celebrity contributors, and how the recipes included were reflective of the periods in which they were published. The cookbooks are still dealt with in generalizations, however, and their individuality is lost in the mix. The section on celebrities, although interesting contains another missed opportunity, as Kumin mentions one recipe contribution from noted feminist Charlotte Perkins Gilman, but not her dislike of cooking. In the section on funding, Kumin clearly notes that the cookbooks were usually designed as fundraisers for the organizations, a fact that belies her argument that cookbooks were meant to convert, though she does note they were sometimes also used as enticing premiums for subscriptions. Chapter 7 is a brief discussion of how suffragists used dinners and entertaining to support the cause. All Stirred Up ends without a clear conclusion, instead relying on Chapter 8, “What Suffrage Means for Us,” an eight-page summary of women in American politics since 1920. This final chapter makes no clear reference to the influence of the cookbooks that purportedly drove the suffrage movement and does not sum up the arguments outlined in the introduction. It is followed by 28 pages of dessert recipes. There is no explanatory postscript, only Kumin’s acknowledgements. In all, All Stirred Up does make a good point about the role of suffrage cookbooks in the movement, but it fails to back up its few arguments convincingly, particularly in light of the use of community cookbooks as fundraising tools, rather than modes of conversion to the cause. Instead of concentrating the bulk of her argument into Chapter 4, Kumin would have had a much more compelling book had she spread that argument throughout all the chapters, addressing the role of domesticity from the perspectives of both the suffragists and the antis. More primary source analysis would have enriched the narrative. Looking at the writing of major suffrage leaders to determine their personal opinions on cooking and domesticity would have added depth to her arguments. Examining the cookbooks themselves, their recipes, and the organizations and women that produced them as a chronological accounting of the movement, would have added greatly to the coherence and context of the book. Had the recipe sections been introduced by era, with headnotes and historical context for each recipe, their inclusion would have made the book both stronger and appealing to the general public. Ultimately, the book feels as though it was rushed to print, possibly to coincide with the centennial anniversary of the 19th Amendment in 2020. If you are unfamiliar with basic suffrage and food history, this may provide some good historical summaries and Kumin’s research on the 1909 Washington Women’s Cook Book is particularly strong. But, if you were hoping for a well-written, well-organized examination of the role of food in the suffrage movement and the influence of suffrage cookbooks, as I was, you’ll be sorely disappointed. I can only hope that future historians can expand on Kumin’s work. If you'd like more food history book reviews, check out the Book Review category of this blog. The Food Historian blog is supported by patrons on Patreon! Join us for awesome members-only content like free digitized cookbooks from my personal collection, e-newsletter, and even snail mail from time to time!

On New Year's Eve with broke with tradition a little and did a surprise THURSDAY Food History Happy Hour at 11 PM. Because it was spur of the moment, we didn't really have a specific topic, but we did talk about comparisons between 1920 and 2020, an update about my office/cookbook library, my family New Year's Eve traditions old and new, some of the "lucky" foods of NYE, the Swedish celebrations I grew up with, including Tjuegondag Knut and Sankta Luciasdag, 19th century New Year's menus, what I missed most in 2020, and hopes for 2021.

Vanilla Fig Bourbon Recipe

No historic recipe this time, but the fig bourbon turned out quite nicely! If you want to make your own, here's a nice recipe:

2 cups dried mission figs 1 vanilla bean bourbon to fill a quart jar Put the figs in a quart mason jar. Cut the vanilla bean in half and add to the jar. Fill with enough bourbon to cover the fruit. Let age 3-12 months before consuming. I had some on the rocks with ginger ale. And some of the figs may make their way into a boozy fruitcake at some point. Episode Links

Not too many this time around, but here are a few to whet your whistle:

The next Food History Happy Hour will be on Friday, January 15, 2021 at 8:00 PM EST. We're gonna discuss more in-depth January holidays, including revisiting New Year's, Twelfth Night, Tjuegondag Knut, and my birthday, with a discussion of birthday cake history! See you next time.

The Food Historian blog is supported by patrons on Patreon! Join us for awesome members-only content like free digitized cookbooks from my personal collection, e-newsletter, and even snail mail from time to time!

|

AuthorSarah Wassberg Johnson has an MA in Public History from the University at Albany and studies early 20th century food history. Archives

July 2024

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed