|

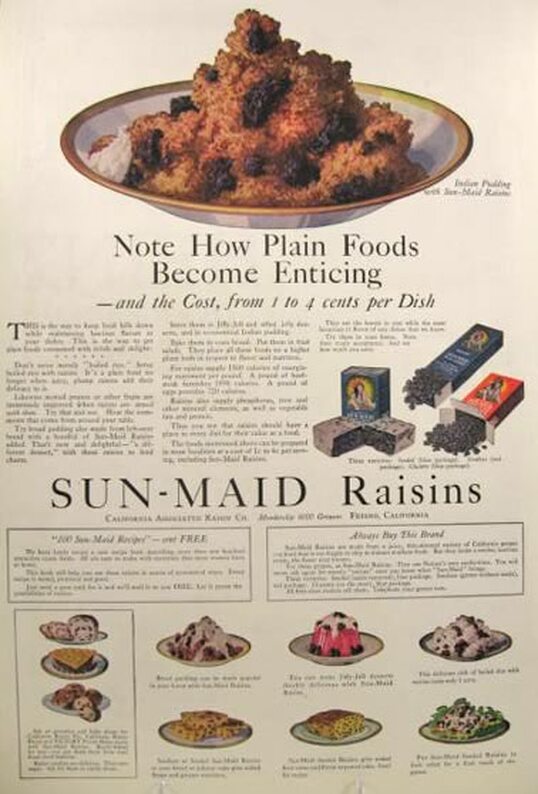

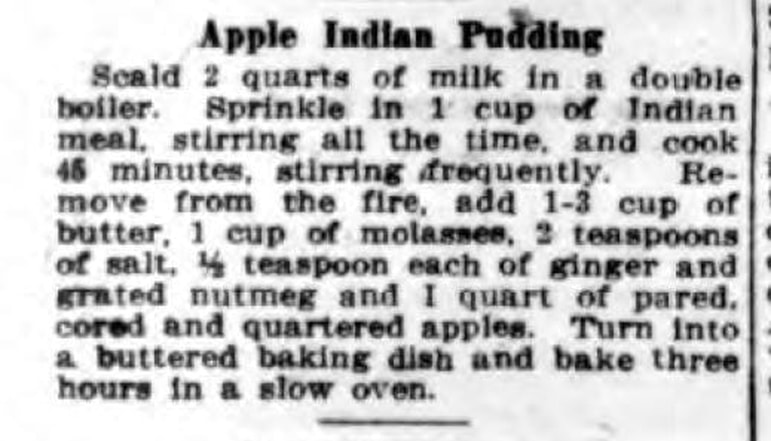

I don't remember when I first encountered "Indian pudding." Derived from the Colonial name for cornmeal - "Indian meal" - it's an iconic dish of New England, though it isn't often made anymore. Combining Indigenous foodways, European cooking techniques, and molasses, a ubiquitous sweetener made cheap by the brutal labor of enslaved Africans, Indian pudding reflected the kind of stick-to-your-ribs cooking common in the Colonial period when people ate less frequently and engaged in harder labor, and with less access to heating than they do today. The above advertisement by Sun-maid Raisins from 1918 is a good illustration of this. "Note How Plain Foods Become Enticing," the ad reads, showing how Indian Pudding could be spiced up with raisins, and then goes on to show just how inexpensive raisins were. Historically, raisins were rather expensive, and had to be stoned (remove the seeds) by hand, a labor-intensive step that continued until the early 20th century. By the time Sun-maid is advertising in 1918, you no longer had to stone raisins - they came seedless. Clearly Sun-maid was trying to convince people that raisins were a more economical purchase than previously believed. Also, the use of Indian Pudding to illustrate the "plain foods" shows how it was viewed by most Americans at that time - plain, cheap, and filling. Indian pudding also fit nicely into rationing suggestions to use less sugar, refined white flour, and fats. With its ingredients of cornmeal and molasses, Indian pudding fit the bill. I first ran across a recipe for Apple Indian Pudding when researching the history of the Farm Cadets in New York State. The article right next to it was about the establishment of the Farm Cadet Corps under the State Military Training commission. Published in the Buffalo Evening News on April 19, 1917, just two weeks after the United States entered the war, it was included as part of a column called "Lucy Lincoln's Talks" and was one of many recipes. Although the United States Food Administration was not yet formed and no rationing recommendations had been issued, President Wilson had been publicly discussing the role of food in the war effort. Throughout the First World War, the United States Food Administration and home economists hearkened back to the Colonial period for several reasons. First, it appealed to Americans' sense of patriotism. Following the American Civil War, Northern reformers made a concerted effort to re-unite the nation and define what it meant to be American. Thanks to the unconscious bias of white supremacy, that idea became closely connected to New England and the mythology around the Pilgrims and the founding of the nation (despite the fact that Spanish Florida, Virginia, parts of Canada, and even New York had been settled earlier). Second, hearkening back to the Colonial period allowed ration supporters to encourage the substitution of non-rationed food items like cornmeal and molasses which had deep Colonial roots, for rationed foods like refined white flour and refined white sugar, which were needed for the war effort. Third, these ingredients were often very inexpensive. By connecting them to the honored founders of the country, food reformers could convince middle and upper class people to eat what may have been previously only associated with the poor and working class, in the name of patriotism. Despite the lack of actual rationing recommendations at this point, the recipe for Apple Indian Pudding would have fit very nicely into the requirements. It used cornmeal, which saved wheat. It used molasses and apples for sweetener, which saved sugar. It used two quarts of milk, which would help use up the milk surplus and add protein. It was also extremely inexpensive and filling, which meant it had appeal for folks on a budget or with large families. The recipe does, however, call for 1/3 cup of butter, which would become one of the recommended ration items in just a few months. Apple Indian Pudding RecipeI have made Indian Pudding before for a talk, and it's lovelier than you'd think. Here's the original recipe: "Scald 2 quarts of milk in a double boiler. Sprinkle in 1 cup of Indian meal, stirring all the time, and cook 45 minutes, stirring frequently. Remove from the fire, add 1/3 cup of butter, 1 cup of molasses, 2 teaspoons of salt, 1/2 teaspoon each of ginger and grated nutmeg, and 1 quart of pared, cored, and quartered apples. Turn into a buttered baking dish and bake three hours in a slow oven." And here's a modern translation: 8 cups (or a half gallon) whole milk 1 cup cornmeal 1/3 cup butter 1 cup molasses 2 teaspoons salt 1/2 teaspoon ground ginger 1/2 teaspoon grated fresh nutmeg 3-4 apples Preheat the oven to 300 F. In a double boiler or heavy-bottomed pot, heat the milk, but do not boil. Once hot, slowly whisk in the cornmeal and cook, stirring frequently, for 30-45 mins or until the cornmeal is fully cooked and has absorbed the milk. Remove from heat and while hot, stir in the butter, molasses, salt, and spices. Peel, core, and slice the apples thickly. Stir the apple slices into the cornmeal mixture, and tip it all into a buttered glass or ceramic baking dish. Place in the oven and let bake for 3 hours, uncovered. Serve hot or warm plain (ration-friendly) or with vanilla ice cream or unsweetened liquid cream (not-so ration-friendly). Although the original recipe calls for quartered apples, most modern apples are very large, and a quarter might be too big, which is why I suggest slicing them instead. If you're in an area of the world that gets cold in the fall and winter, Apple Indian Pudding is the perfect, homey dessert to attempt on a day when you'll be puttering around the kitchen or the house all day. Pop some baked beans in with it if you really want a traditional New England supper (and a ration-friendly one!). It really does take three whole hours to bake (other versions included steaming like plum pudding), but the long, slow heat turns the normally crunchy cornmeal into melting softness. There's a reason why it's still so popular in New England. If you want to know more about the history of Indian Pudding, including how to make a historic recipe, check out my lecture below! The Food Historian blog is supported by patrons on Patreon! Patrons help keep blog posts like this one free and available to the public. Join us for awesome members-only content like free digitized cookbooks from my personal collection, e-newsletter, and even snail mail from time to time! Don't like Patreon? Leave a tip!

0 Comments

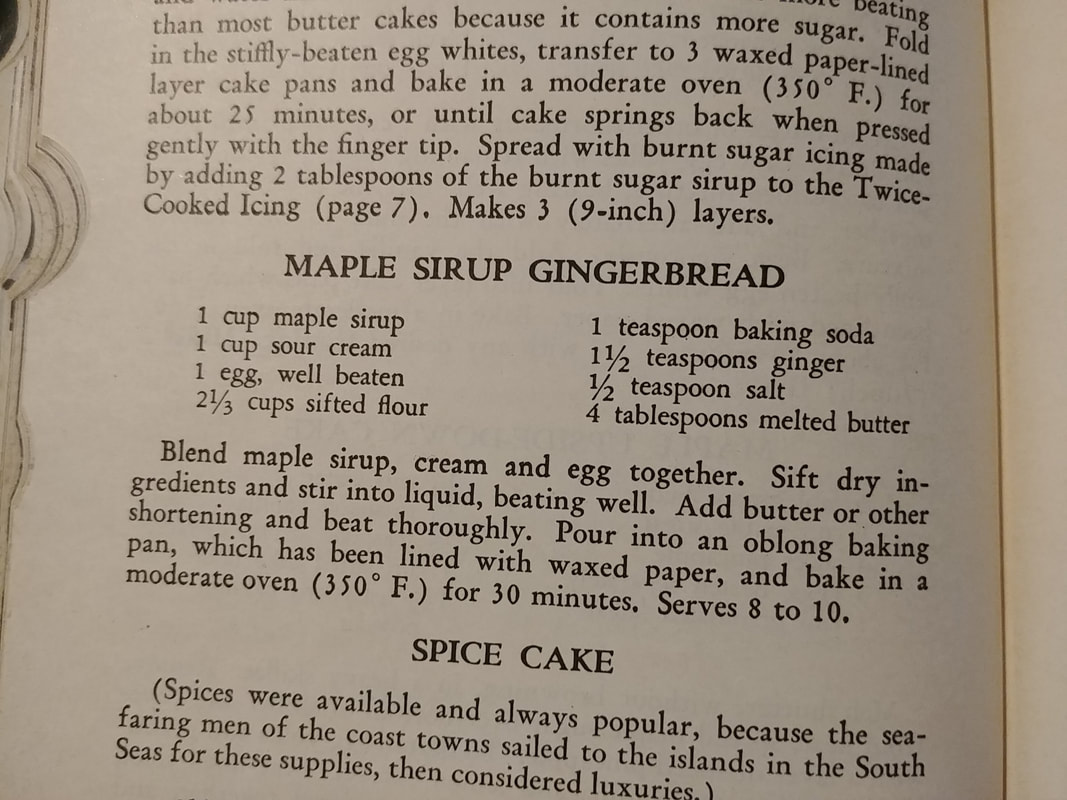

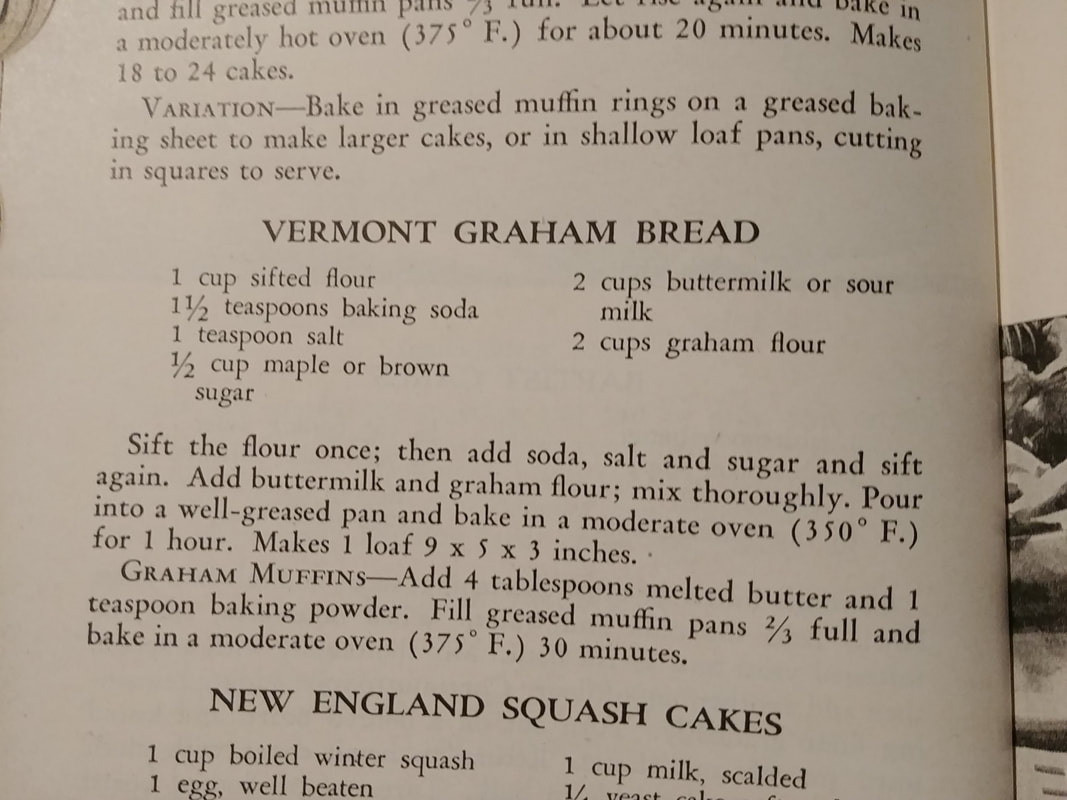

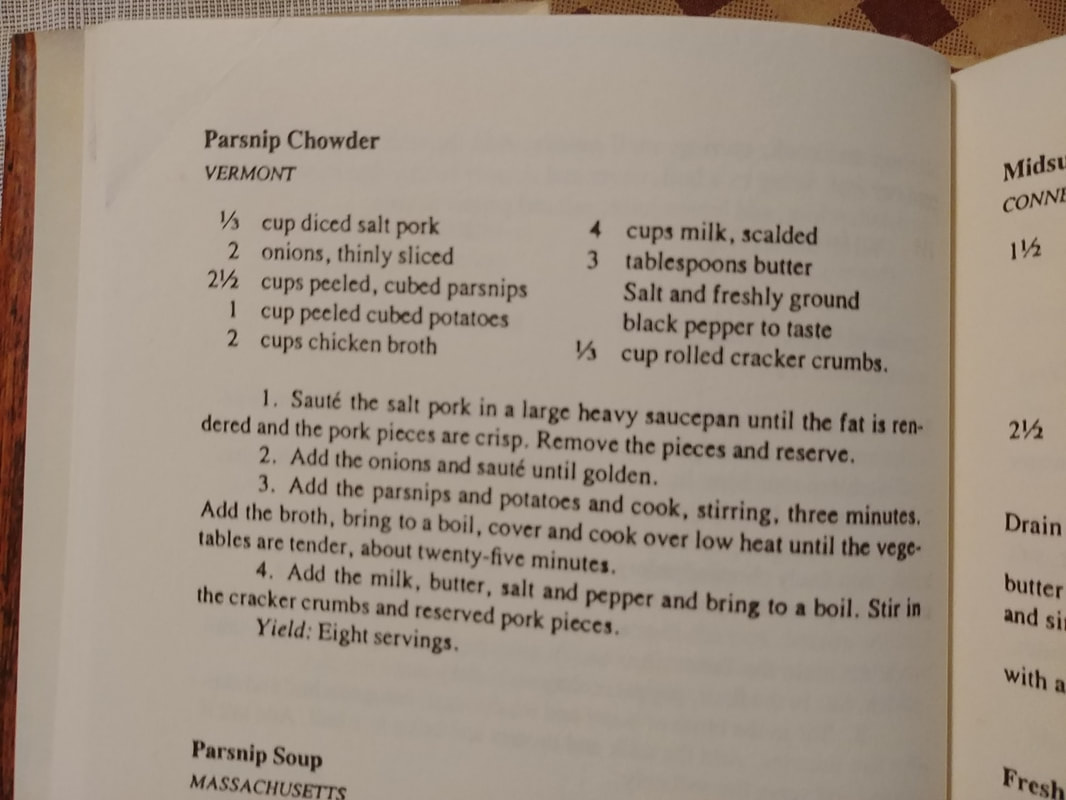

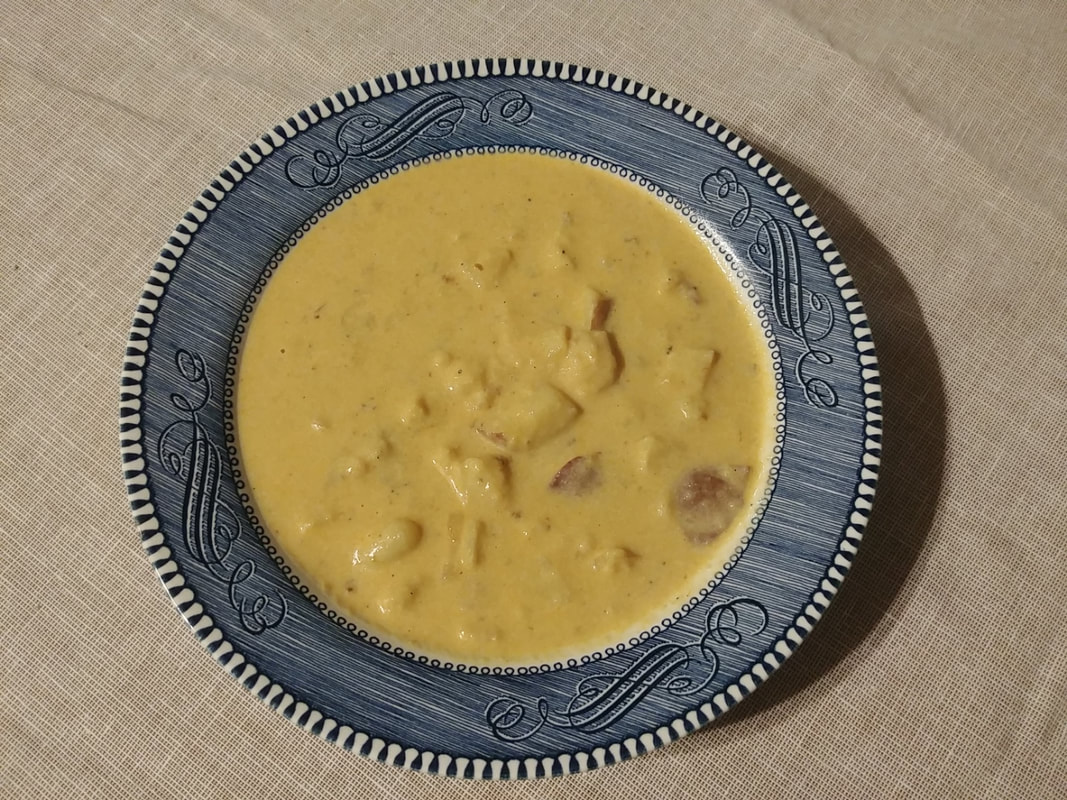

I really debated what dessert would go best with White Christmas. Aside from the malted milkshake, and the General's birthday cake, none are mentioned in the movie. I thought about going the fruitcake route, but I didn't exactly have time for it to soak. And then, when flipping through The United States Regional Cook Book (1947), I ran across a recipe I'd found and wanted to try earlier in the year - "Maple Sirup Gingerbread." Gingerbread is a traditional Christmas food dating back to the Medieval period, and the use of maple syrup (or, in 1940s spelling, "sirup") made the recipe appropriately Vermont-y. During World War II, maple syrup was touted as a sugar alternative and throughout history it has generally been less expensive than refined white sugar. Not so today, when a quart of maple syrup ranges in price from $15-$25, depending on where you are (which means a cup averages about $5). If you'd rather not "waste" a whole cup of maple syrup on a cake, feel free to use a different gingerbread recipe (may I recommend New York Gingerbread?). Maple Sirup Gingerbread (1947)It occurred to me after I started making this that the "sour cream" in the recipe was probably SOURED liquid cream, instead of the thick, dairy sour cream we're used to these days. But I went with it anyway. If you want to try something closer to the original, split the difference and use a half cup of heavy cream and a half cup of sour cream. Aside from that, I made no changes to this recipe, except to make an executive decision about "oblong baking pans" and just do a round one instead. I also don't recommend lining the pan with waxed paper, unless you want the wax to melt into your cake and onto your pans. Parchment is fine, but unnecessary. Just grease the pan well. 1 cup maple syrup 1 cup sour cream 1 egg, well beaten (you don't actually have to beat the egg in advance) 2 1/3 cups sifted flour (ditto sifting) 1 teaspoon baking soda 1 1/2 teaspoons ginger 1/2 teaspoon salt 4 tablespoons melted butter (1/2 a stick) Blend maple syrup, sour cream, and egg together until smooth. Add dry ingredients and whisk into the liquid ingredients, making sure to stir well. Add butter and beat thoroughly. Pour into greased ROUND cake pan and bake at 350 F for 30-40 minutes, or until the center of the cake springs back to the touch. Loosen the edges and tip out the pan to cool on a rack. Serve warm or cold with plenty of whipped cream. A word to the wise, you'll note that this recipe ONLY contains ginger, no other spices. But it contains quite a bit of ground ginger, which means the ginger flavor is very forward and in my opinion masks the flavor of the maple syrup, though my husband swore he could taste it. You might want to dial back the ginger a bit if you make it. Either way, it's very good - dense and moist with lots of good gingery flavor and feeling appropriately Christmassy. If you're trying to be healthier, I recommend subbing half of the all-purpose flour with a whole grain one. Spelt or rye would both be nice. So what do you think? Does Maple Sirup Gingerbread go with White Christmas (1954)? Let me know in the comments! And be sure to follow the White Christmas tag or visit the original menu post for the rest of the White Christmas Dinner and a Movie menu. Want to see more Dinner and a Movie posts? Make a request or drop your suggestions in the comments! The Food Historian blog is supported by patrons on Patreon! Join us for awesome members-only content like free digitized cookbooks from my personal collection, e-newsletter, and even snail mail from time to time! White Christmas has a famous scene about sandwiches. In it, Bing Crosby (playing Bob Wallace) waxes lyrical on the types of women he dreams about when he eats various sandwiches as a bedtime snack. Rosemary Clooney (playing Betty Haynes) teasingly asks him what he dreams about when he eats liverwurst. Bob shudders in response. I'll be honest - I've never had liverwurst. Some people love it, some people hate it. Maybe someday I'll try it, but my vegetarian friend saved the day. The phrase "lentilwurst" popped into my mind and I decided to run with it. This recipe is the only one that isn't based on a historical recipe (for obvious reasons), but lentils were around in the 1950s and were used as a vegetarian substitute for meat. This recipe also takes after slightly the infamous vegetarian bean loaves and nut loaves of the late 19th and early 20th century. In fact, one of the recipes I considered for the menu was "Boston Roast," which is a take on meat loaf, only made with beans (hence Boston) instead. I based my recipe loosely on this one, but with a few tweaks of my own. Here's my version, which you could easily make vegan by using olive oil or butter substitute, and vegan mayonnaise. Lentilwurst (a.k.a. Vegetarian Liverwurst)1 cup red lentils 1 1/2 cups water 1/4 cup butter (half a stick) 1 pint baby bella mushrooms 1 teaspoon dried sage (not ground - use 1/2 teaspoon if using ground) 1 teaspoon smoked paprika 1/2 teaspoon ground ginger 1/2 teaspoon ground mace (can use nutmeg instead) 1/2 teaspoon black pepper 1/2 teaspoon onion salt 2 heaping tablespoons mayonnaise Rye bread Dijon mustard In a 2 quart saucepan, bring lentils and water to a boil, then reduce heat and cook until lentils are very soft and have absorbed all water (watch out for boiling over and stir occasionally). Meanwhile, clean and finely mince mushrooms. When the lentils are done, remove to a glass dish to cool. Wash the same saucepan and add the butter and spices. When butter is melted, add mushrooms and cook over medium to medium-low heat until the juices and butter are largely reduced. Mix mushrooms, lentils, and mayonnaise until well combined. Chill in a glass container in the fridge. When ready to serve, slice or spread onto rye bread that has been thinly spread with mustard. Eat open faced or closed. The lentilwurst sandwiches were the surprise hit of the evening. Everything on the menu was good, but this was so good I was very sad I hadn't made a double batch, and have since gone out and bought more mushrooms precisely so I can make more. The mushrooms and lentils gave it a meaty texture, and the salty, spicy flavors of the seasonings went very well with the rye bread and mustard (traditional liverwurst sandwich ingredients). I did not add onions or pickled onions to the sandwiches as I had considered, but that would be another lovely addition. We gobbled this right up with no regrets. Do you think lentilwurst goes with White Christmas (1954)? Let me know in the comments! And be sure to follow the White Christmas tag or visit the original menu post for the rest of the White Christmas Dinner and a Movie menu. Want to see more Dinner and a Movie posts? Make a request or drop your suggestions in the comments! The Food Historian blog is supported by patrons on Patreon! Join us for awesome members-only content like free digitized cookbooks from my personal collection, e-newsletter, and even snail mail from time to time! For those of you who have been following along, this is part of my "Dinner and a Movie: White Christmas" series! I wanted something to go nicely with the Vermont Parsnip Chowder, so I thought Vermont Graham Muffins would do very well, indeed. Graham flour is entire wheat flour (not to be confused with regular whole wheat flour, which is usually just white flour with some of the wheat germ added back in). Named after 19th century health reformer Sylvester Graham, it was one of the only parts of his largely unpalatable health and religious reforms, many of which were later adopted by Seventh Day Adventist prophet Ellen G. White and even later by John Harvey Kellogg, that was widely accepted by the general public. Graham pudding, graham gems, graham bread, graham muffins and eventually, yes, graham crackers (which would have appalled Sylvester), were all prevalent in cookbooks throughout the 19th and into the 20th century. And Kellogg used graham flour in his "Granula" cereal. Graham flour came to be widely associated with New England in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. This particular recipe I found in the absolutely delightful The United States Regional Cook Book, edited by Ruth Berolzheimer. My edition was published in 1947. It has a whole section on New England foods (among others), and "Vermont Graham Bread" is included in the chapter, "Breads, Quick Breads, and Pancakes." Vermont Graham (or Rye) MuffinsThe original recipe is geared towards a loaf of bread, but who wants to wait a whole hour for bread when you can have muffins in half the time? I should also confess that after all the rhetoric about Graham flour, I could not find any in the store, and I thought I had regular whole wheat flour at home. Wrong. So I substituted rye flour (an equally New England ingredient) and it was delightful. So feel free to substitute whole wheat, rye, or even spelt flour, if you like. I also made my own "buttermilk" with a tablespoon of lemon juice per cup of whole milk, but this recipe would probably be a smidge more moist with real buttermilk. This is my take on the original recipe, with the listed additions for muffins. 1 cup all-purpose flour 1 1/2 teaspoons baking soda 1 teaspoon baking powder 1 teaspoon salt 1/2 cup packed brown sugar (feel free to use less) 2 cups buttermilk 2 cups graham flour (or rye) 4 tablespoons butter, melted (half a stick) Preheat the oven to 375 F. Grease a standard muffin tin. Whisk together the all-purpose flour, graham flour, baking soda and powder, salt, and brown sugar until well combined (try not to leave any brown sugar lumps, but don't worry if you do). Stir in the buttermilk and melted butter. Spoon into muffin tins (makes a dozen) and bake 30 minutes, or until muffins are golden brown and spring back to the touch. Remove from tins and cool on a wire rack. Serve warm with plenty of butter. These muffins taste slightly reminiscent of bran muffins, but are more like bread and less like the sugary sweet breakfast cakes most of us associate with the word "muffin." They are a bit sweet, so feel free to cut back on the brown sugar a bit if you're looking for something strictly more bread-like. They are best when served warm with butter, but are perfectly adequate cold as well. Do you think graham muffins go with White Christmas (1954)? Let me know in the comments! And be sure to follow the White Christmas tag or visit the original menu post for the rest of the White Christmas Dinner and a Movie menu. Want to see more Dinner and a Movie posts? Make a request or drop your suggestions in the comments! The Food Historian blog is supported by patrons on Patreon! Join us for awesome members-only content like free digitized cookbooks from my personal collection, e-newsletter, and even snail mail from time to time! For those of you who have been following along, this is part of my "Dinner and a Movie: White Christmas" series! I wanted to find a vegetarian main dish to go with the movie, and given that Christmastime is cold up here in New York, I thought soup would be something cozy and not too elaborate. In perusing some of my vintage cookbooks, I ran across this gem in the 1977 New York Times New England Heritage Cookbook by Jean Hewitt. Clam chowder is, of course, quintessentially New England, which seemed appropriate given that our Fabulous Quartet were headed to Vermont for the winter holiday. And clam chowder is one of my husband's favorites, but I'm allergic to shellfish. This recipe for Parsnip Chowder is attributed to Vermont, which makes sense given that that great state does not border the ocean. And since parsnips are a delightful, if underutilized, vegetable, I thought I would give this chowder a go. Because our friend is vegetarian, I did end up making a few changes. Vermont Parsnip Chowder (1977)Here's the original recipe (pictured above): 1/3 cup diced salt pork 2 onions, thinly sliced 2 1/2 cups peeled, cubed parsnips 1 cup peeled, cubed potatoes 2 cups chicken broth 4 cups milk, scalded 3 tablespoons butter salt and freshly ground black pepper to taste 1/3 cup rolled cracker crumbs 1. Sauté the salt pork in a large, heavy saucepan until the fat is rendered and the pork pieces are crisp. Remove the pieces and reserve. 2. Add the onions and sauté until golden. 3. Add the potatoes and parsnips and cook, stirring, three minutes. Add the broth, bring to a boil, cover, and cook over low heat until the vegetables are tender, about twenty-five minutes. 4. Add the milk, butter, and salt and pepper and bring to a boil. Stir in the cracker crumbs and reserved pork pieces. Yield: Eight servings. Okay, so, I did not make many changes, but I did make a few substantial ones, which I think turned out quite nicely. Here are my changes: 1/4 cup olive oil (or half a stick of butter) 1 tablespoon smoked paprika 2 onions, sliced 4 cups parsnips, peeled and cubed (about 3 large parsnips) 2 cups red potatoes, cubed (about 3 smallish ones, and I like the peel for texture) 3 cups water 1 cup heavy cream 3 cups whole milk garlic salt black pepper In a large pot over medium heat, bloom the paprika in the olive oil, then add the onions and sauté until tender. Add the parsnips and potatoes and stir to coat. Let cook until slightly browned in spots. Add the water and bring to a boil, then reduce heat and simmer, covered, until the vegetables are fork-tender. Add the heavy cream, milk, garlic salt, and pepper, and simmer, cover off, until the chowder thickens. Taste and add more salt if necessary. The parsnips and onions make it quite sweet. The chowder turned out beautifully - a thick, creamy texture with tender bits of parsnip and potatoes (the onions basically melted into the cream) and a lovely golden color. The cream really thickens the chowder up without the addition of crackers (although you could add saltines or oyster crackers if you want). We ate up the leftovers pretty quickly, and in some ways it was better the next day. What do you think? Is parsnip chowder something you would try? Do you think it goes with White Christmas (1954)? Let me know in the comments! And be sure to follow the White Christmas tag or visit the original menu post for the rest of the White Christmas Dinner and a Movie menu. Want to see more Dinner and a Movie posts? Make a request or drop your suggestions in the comments! The Food Historian blog is supported by patrons on Patreon! Join us for awesome members-only content like free digitized cookbooks from my personal collection, e-newsletter, and even snail mail from time to time! White Christmas (1954) is probably one of my favorite holiday films. I did not grow up watching it. In fact, my husband was the one who introduced me to it, but I fell in love. It's got everything - WWII, great relationships, music, dancing, everything wonderful and awful about putting on a show (former theater nerd, here), and of course, a heartwarming tale in a beautiful setting. Not to mention Bing Crosby's velvet voice. So when a friend, who had never seen White Christmas, suggested I make a dinner menu to go along with the film, I couldn't resist. She knew I'd done similar menus before (Star Wars and The Hobbit, respectively, both birthday parties I threw myself), but this one was fun because I could delve into all my vintage cookbooks for ideas. Now, there are a few foods mentioned or shown in the film. One of the first (and best) is the scene in the club car on the way to Vermont. Mentioned or shown foods include:

The other major scene is after hours, when sandwiches and buttermilk are the order of the day. Mentioned or pictured in this scene are:

Other foods shown include hotdogs by the fire and, of course, the General's enormous birthday cake. Clearly dinner is served in that scene, but it's difficult to see what. There was an added hiccup in all this menu planning - the friend in question is vegetarian. So guess what? A lot of that list is out the window! But I relish a good challenge, so I took to my cookbooks and got thinking. And here's what I came up with: I based my recipes largely on the foods of the late 1940s, focusing on New England recipes. Because although White Christmas was released in 1954, and clearly takes place in the 1950s, it was influenced by the earlier (and slightly more racist) Holiday Inn, which came out in 1942. In addition, the WWII connection between Bob and Phil (a.k.a. Wallace & Davis), made me think this menu needed a little bit of a 1940s flavor. Here's the menu:

No, those aren't typos - "lentilwurst" is what I call vegetarian liverwurst and while everything was good, that was the surprise hit of the night. I wish I had made a double batch because it was gone almost instantly. Maple Sirup (also not a typo - that's how they spelled it in the cookbook) Gingerbread was another delightful (if rather expensive) hit. Thankfully, we did not eat the whole cake in one sitting, although two days later we're down to the last piece. In an effort to spare you from the world's longest blog post, I'm going to be posting the recipes each day this week (probably more than one per day) as their own blog posts. Don't worry - I'll link them back here as they're posted so you can always find everything in one spot. You should get the whole menu before the weekend - just in time to plan a White Christmas Dinner and a Movie of your own! Happy eating! Want to see more Dinner and a Movie posts? Make a request or drop your suggestions in the comments! As always, The Food Historian blog is supported by patrons on Patreon! Join us for awesome members-only content like free digitized cookbooks from my personal collection, e-newsletter, and even snail mail from time to time! |

AuthorSarah Wassberg Johnson has an MA in Public History from the University at Albany and studies early 20th century food history. Archives

July 2024

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed