|

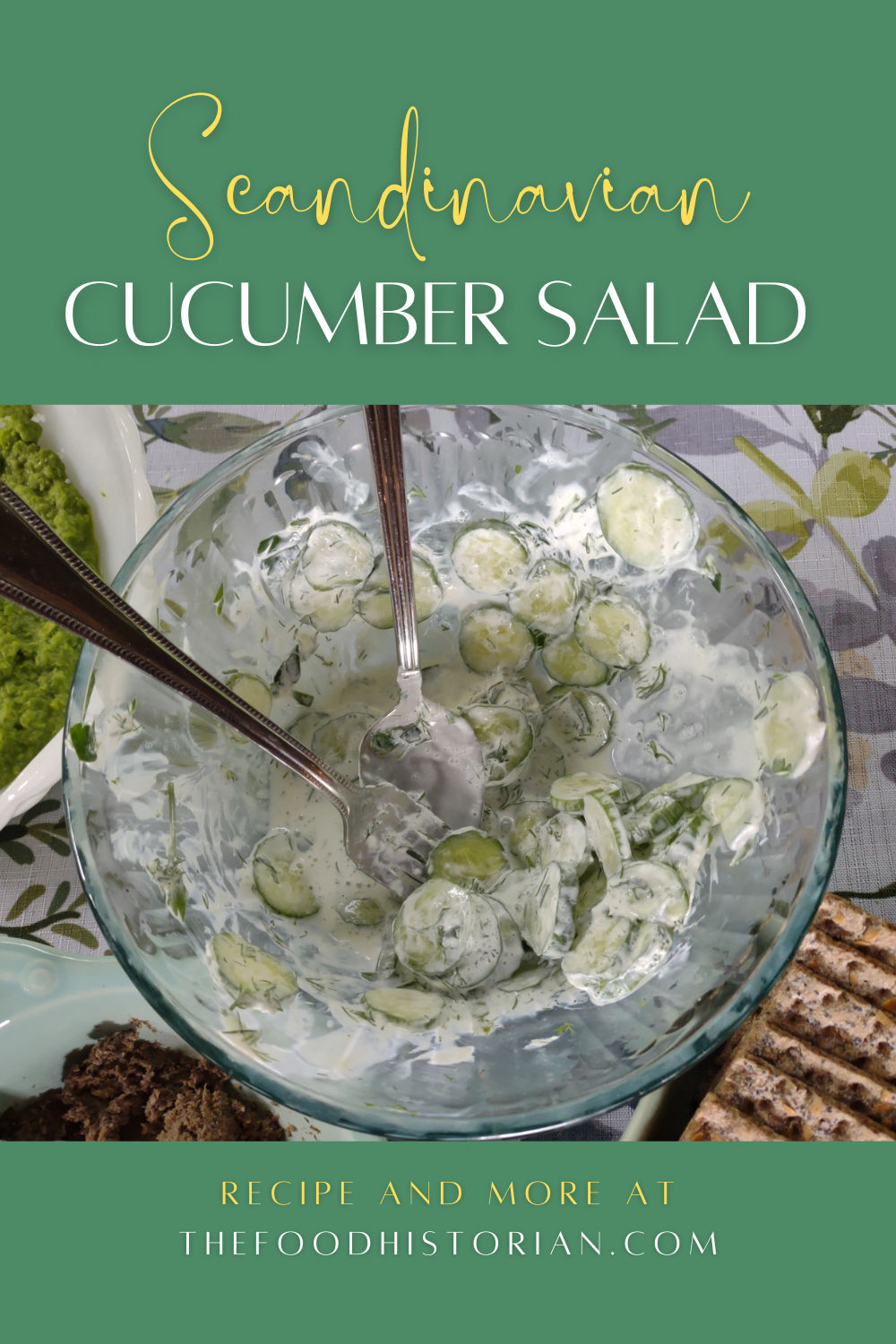

Cucumber salad with dill and sour cream just screams summer and Scandinavia. So when I planned my Scandinavian Midsummer Porch Party, I knew it had to be included. Agurksalat is the Norwegian name of cucumber salad, but funnily enough, most cucumber "salads" in Scandinavia are more like quick cucumber pickles - thinly sliced cucumbers are covered with a brine of vinegar, salt, and sugar, with fresh dill. This salad is often used to accompany fish, or as a topping for rye bread and liver pate. But where I was growing up in the Red River Valley of North Dakota, cucumber salad was made with sour cream. I wonder if these salads weren't invented to use up the bumper crops of cucumbers that often result. Certainly in Scandinavia they were historically celebrated as a herald of spring, and were eaten only for the short months they were available in outdoor gardens, mostly June and July. In the US, especially the Upper Midwest, the cucumbers are often peeled, but I'm a big fan of English/burpless/seedless/Persian cucumbers, which are thinner skinned, less bitter, and more crisp than their larger counterparts. These cucumbers are perfect for salads as they're crisp enough to hold up under dressings but tender enough to taste more like garden-grown. I am not particularly a fan of the sweet-sour brine (which seems to also be used to pickle herring!), and dislike bread and butter pickles for this reason, so my cucumber salad recipe doesn't include any sugar. This last-minute addition ended up being one of the surprise smash hits of the afternoon, and I sent the little bit that was left home with a friend and her kids, who kept going back for seconds. Scandinavian Cucumber SaladIf you want a more traditional salad, google "agurksalat," but if you want something traditionally Midwestern Scandinavian-American, and surprisingly refreshing on a hot day, stay with me. 6 mini Persian cucumbers, or 1 large English cucumber 1 teaspoon salt 2 scallions white wine vinegar full fat sour cream Wash and thinly slice the cucumber - not paper-thin, but thinner than a quarter inch. Add salt to the bowl and toss the cucumber slices to coat. Let rest for 15 minutes, then drain off the juice. If you're avoiding salt, feel free to give them a little rinse and drain again. Slice the scallions paper-thin, and add to the cucumbers with a splash of vinegar and a dollop of sour cream. Toss everything together until the cucumbers are coated with the vinegar-sour cream mixture. Serve cold or cool. The cucumbers will be salty and crisp and the creamy-sour dressing will be very addictive. Great as an accompaniment to sandwiches, grilled fish or meats, or as one of a variety of cold salads served for a light supper. The Food Historian blog is supported by patrons on Patreon! Patrons help keep blog posts like this one free and available to the public. Join us for awesome members-only content like free digitized cookbooks from my personal collection, e-newsletter, and even snail mail from time to time! Don't like Patreon? Leave a tip!

0 Comments

Nothing says summer like potato salad, but while many people have strong opinions about what constitutes potato salad and what doesn't, in my opinion, if it contains cold (or even warm!) potatoes and some kind of dressing, it's potato salad. Scandinavians have embraced the potato since it was introduced in the mid-1700s, and it now plays a foundational role in some of their most famous foods, including lefse, Jansson's temptation, and the beloved boiled red potatoes that accompany nearly every celebratory meal, including Midsummer. For my Scandinavian Midsummer Porch Party, I thought I'd riff off of a recipe my mother-in-law introduced to me, and make it slightly more Scandinavian. Hers calls for boiled potatoes, sweet onion, white vinegar, and mayo with dried dill. I made mine with boiled red potatoes (also a North Dakota favorite) and fresh dill. Native to the Mediterranean and Eurasia, dill is probably the most important culinary herb in Scandinavia. Only caraway gives it a run for its money. Although most Americans are probably only familiar with it thanks to dill pickles, it is one of my favorite herbs - fresh and green tasting, but not as one-dimensional as parsley or overpowering as fennel or rosemary. It is the perfect complement to fish, cucumbers (as you'll see in the next post), and yes, potatoes. Scandinavians also use it to flavor lamb stew, instead of the more Western mint. Fresh dill can be a bit of a pain to keep fresh, but trim the stems when you get home and place them in a wide-mouth pint mason jar with an inch or so of cold water. It will keep fresh at room temp for a day or so (change the water daily), but put it in the fridge with a plastic bag tent if you want it to keep for longer. The key to this tangy salad is the vinegar, and tossing the onions and potatoes while the potatoes are still hot. Creamy Dilled Potato SaladIf you don't have fresh dill, you can certainly use 2 tablespoons dried dill, but the flavor, while good, won't be quite the same. 2-3 lbs red potatoes 1 sweet onion, like Vidalia or Walla-Walla 2+ tablespoons white or white wine vinegar 1+ cup mayonnaise 1/4 cup chopped fresh dill Wash the potatoes and slice them about a quarter inch thick (I cut my very large potatoes in quarters first). Place in a large pot and add cold water to cover generously. Bring to a rolling boil, reduce the heat slightly (so they don't boil over), and cook until fork-tender, but not quite falling apart. Meanwhile, cut the root end off the onion, then cut in half lengthwise, peel, and cut in quarters or sixths. Slice crosswise paper thin. Add to a large serving bowl or casserole and toss the onions with the vinegar. When the potatoes are done, drain and let them steam for a second, then add while hot to the onions and vinegar. Toss well to combine. Then add mayonnaise to coat and the fresh dill. Taste and add more vinegar as necessary. The vinegar flavor will tame down a bit as the potatoes absorb it, so if making ahead taste the next day and add more vinegar as necessary. You can also add some sour cream if you want this potato salad to be even creamier. Serve as a side dish to grilled meats, sandwiches, or your favorite bean salad. The Food Historian blog is supported by patrons on Patreon! Patrons help keep blog posts like this one free and available to the public. Join us for awesome members-only content like free digitized cookbooks from my personal collection, e-newsletter, and even snail mail from time to time! Don't like Patreon? Leave a tip!

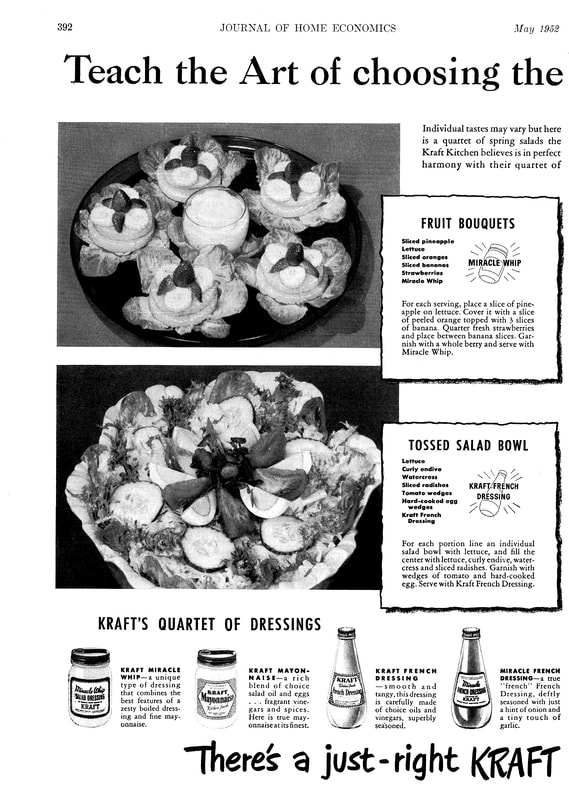

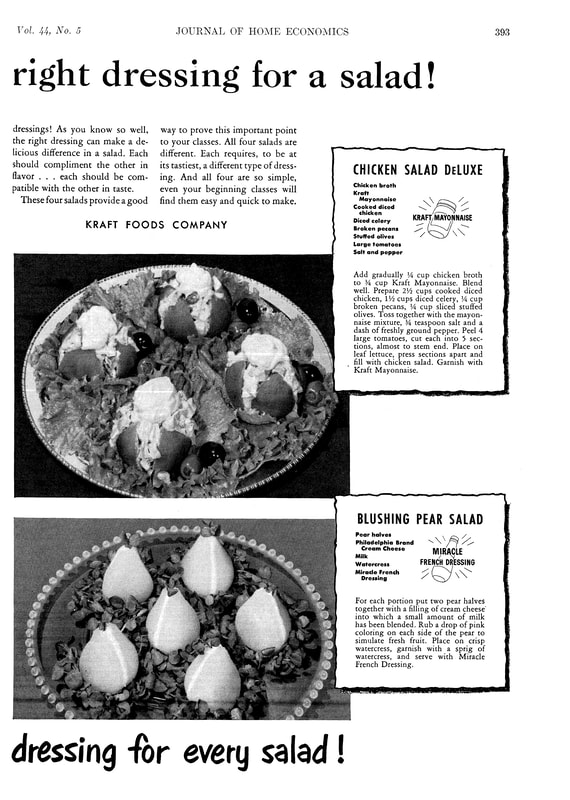

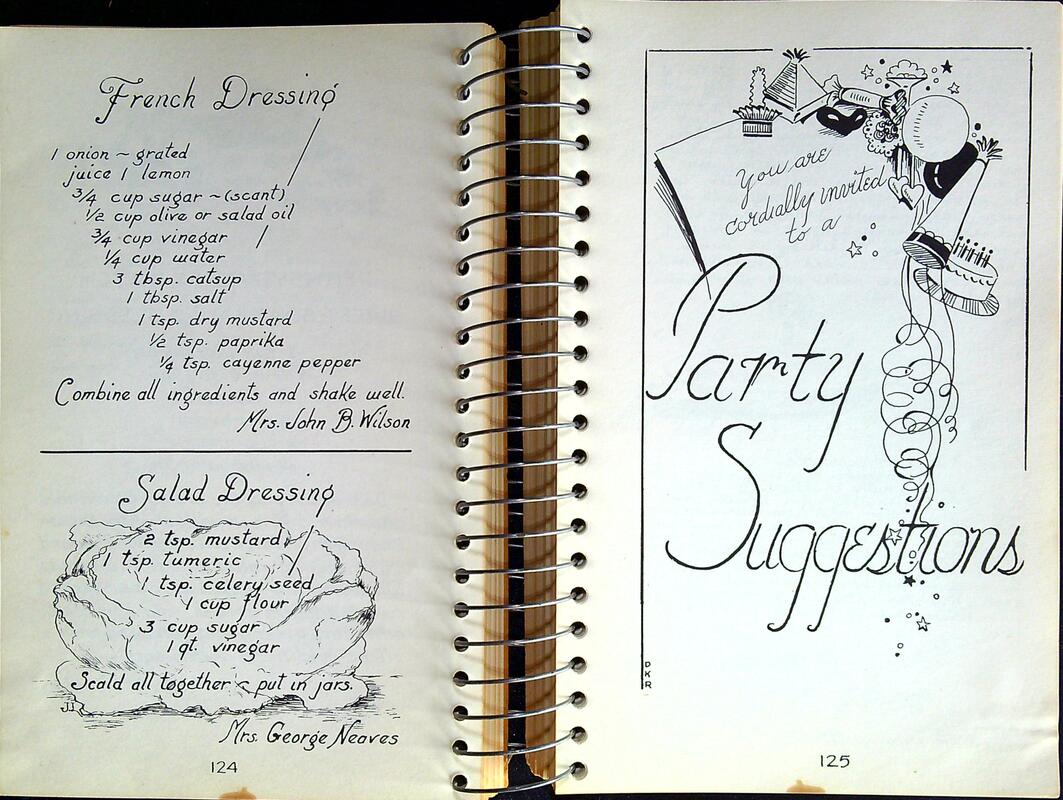

The Food and Drug Administration recently announced that it would be de-regulating French Dressing. And while people have certainly questioned why we A) regulated French Dressing in the first place and B) are bothering to de-regulate it now, much of the real story behind this de-regulation is being lost, and it's intimately tied to the history of French Dressing.

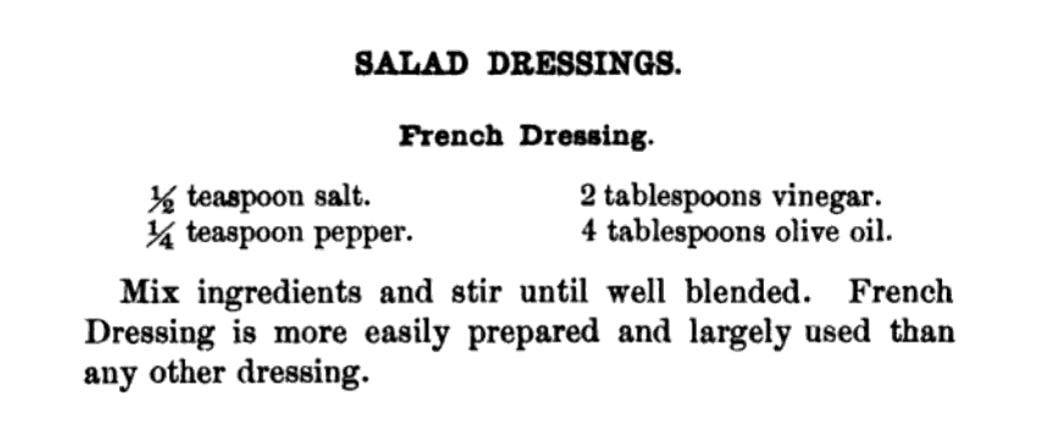

A lot of people like to claim that French Dressing is not actually French. And if you're defining French Dressing as the tangy, gloppy, red stuff pretty much no one makes from scratch anymore, you'd be right. But the devil is in the details, and even the New York Times has missed this little bit of nuance. This Times article, published before the final de-regulation went into place, notes, "The lengthy and legalistic regulations for French dressing require that it contain vegetable oil and an acid, like vinegar or lemon or lime juice. It also lists other ingredients that are acceptable but not required, such as salt, spices and tomato paste." (emphasis mine) What's that? The original definition of French Dressing, according to the FDA, was essentially a vinaigrette? What could be more French than that? In fact, that is, indeed, how "French dressing" was defined for decades. Look at any cookbook published before 1960 and nearly every reference to "French dressing" will mean vinaigrette. Many a vintage food enthusiast has been tripped up by this confusion, but it's our use of the term that has changed, not the dressing. Take, for instance, our old friend Fannie Farmer. In her 1896 Boston Cooking School Cookbook (the first and original Fannie Farmer Cookbook), the section on Salad Dressings begins with French Dressing, which calls for simply oil, vinegar, salt, and pepper.

She's not the only one. I've found references in hundreds of cookbooks up until the 1950s and '60s and even a few in the 1970s where "French dressing" continued to mean vinaigrette. You can usually tell by the recipe - composed salads of vegetables are the most common. If a recipe for "French dressing" is not included, and no brand name is mentioned, it's almost certainly a vinaigrette. So what happened?

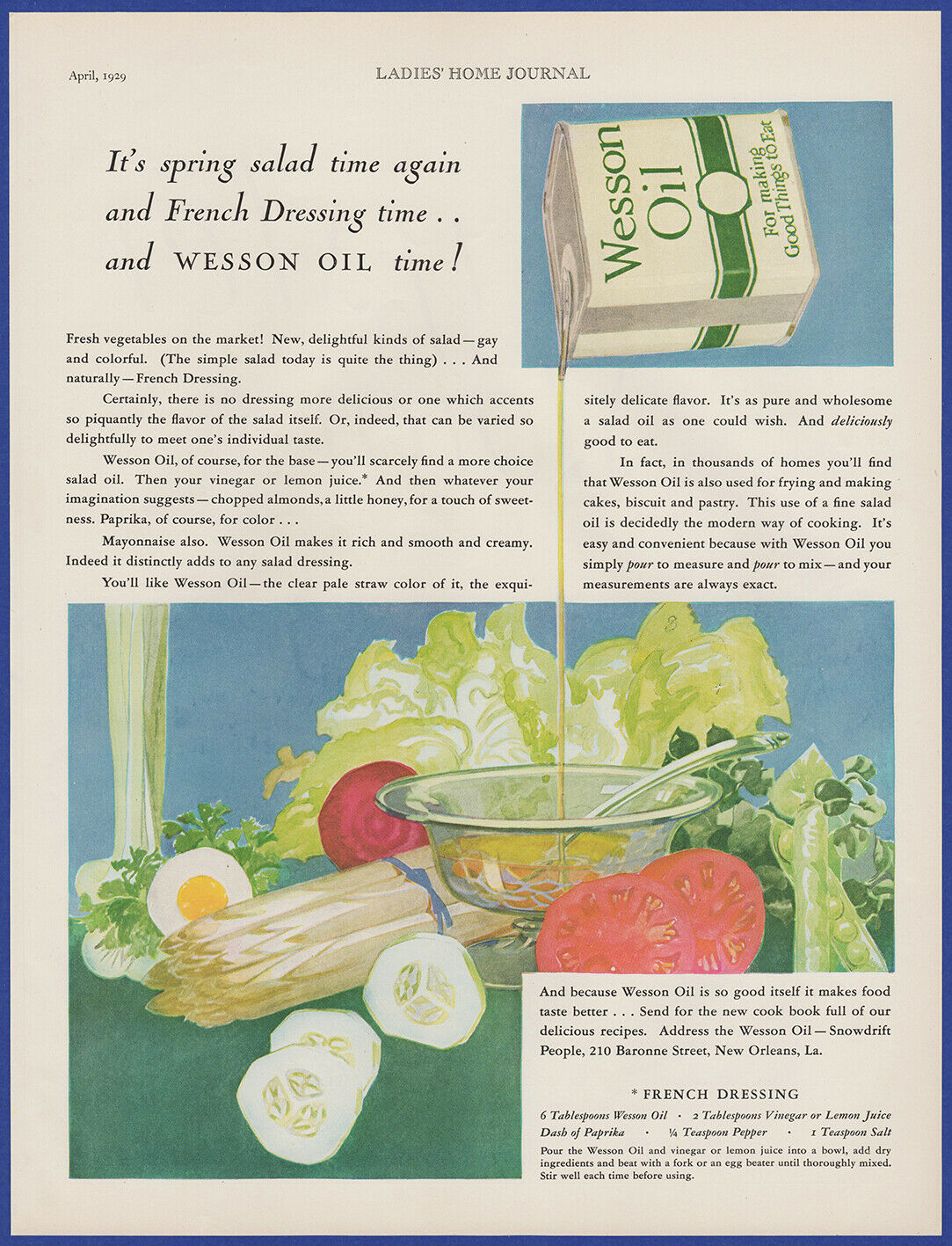

I've managed to track down the original 1950 FDA Standard of Identity for mayonnaise, French dressing, and salad dressing. In it, the three condiments are considered together and are the only dressings identified, likely because few if any other dressings were being commercially produced. Although the term "salad dressing" has been extremely confusing to many modern journalists, it is clearly noted in the 1950 standard of identity of being a semi-solid dressing with a cooked component - in short, boiled dressing. The closest most Americans get today is "Miracle Whip," which is, in fact, a combination of mayonnaise and boiled dressing. Generic brands are often called just "salad dressing" because it was often used to bind together salads like chicken, egg, crab, and ham salad, and also often used with coleslaw. So it makes perfect sense that "French dressing" would be the designated term for poured dressings designed to be eaten with cold lettuce and vegetables - i.e. what we consider salad today. People have wondered why we needed to regulate salad dressings, but there is one very important distinction in the 1950 rule - it prohibits the use of mineral oil in all three. Mineral oil, which is a non-digestible petroleum product (i.e. it has a laxative effect), and which is colorless and odorless, was a popular substitute for vegetable oil during World War II by dieters in the mid-20th century. I collect vintage diet cookbooks and it shows up frequently in early 20th century ones, especially as a substitute for salad dressings. Mineral oil is also extremely cheap when compared with vegetable oils, and it would be easy for unscrupulous food manufacturers to use it to replace the edible stuff, so the FDA was right to ensure that it did not end up in peoples' food. Mineral oil is sometimes still used today as an over-the-counter laxative, but can have serious health complications if aspirated. There were several subsequent addenda to the standard of identity, but most were about the inclusion of artificial ingredients or thickeners, with no mention of any ingredients that might change the flavor or context of what was essentially a regulation for vinaigrette until 1974, when the discussion centered around the use of artificial colors instead of paprika to change the color of the dressing. The FDA ruled that "French dressing may contain any safe and suitable color additives that will impart the color traditionally expected." So here we see that by the 1970s, the standard of identity hadn't actually changed much, but the terminology had. "French dressing" went from the name of any vinaigrette, to a specific style of salad dressing containing paprika (and/or tomato). When people started adding paprika is unclear, but it was probably sometime around the turn of the 20th century, when home economists began to put more and more emphasis on presentation and color. A lively reddish orange dressing was probably preferable to a nearly-clear one. In 2000, the LA Times made an admirable effort to track the early 20th century chronology of the orange recipes. By the 1920s, leafy and fruit salads began to overtake the heavier mayonnaise and boiled dressing combinations of meat and nuts. As the willowy figure of the Gibson Girl gave way to the boyish silhouette of the flapper, women were increasingly concerned about their weight, and salads were seen as an elegant solution.

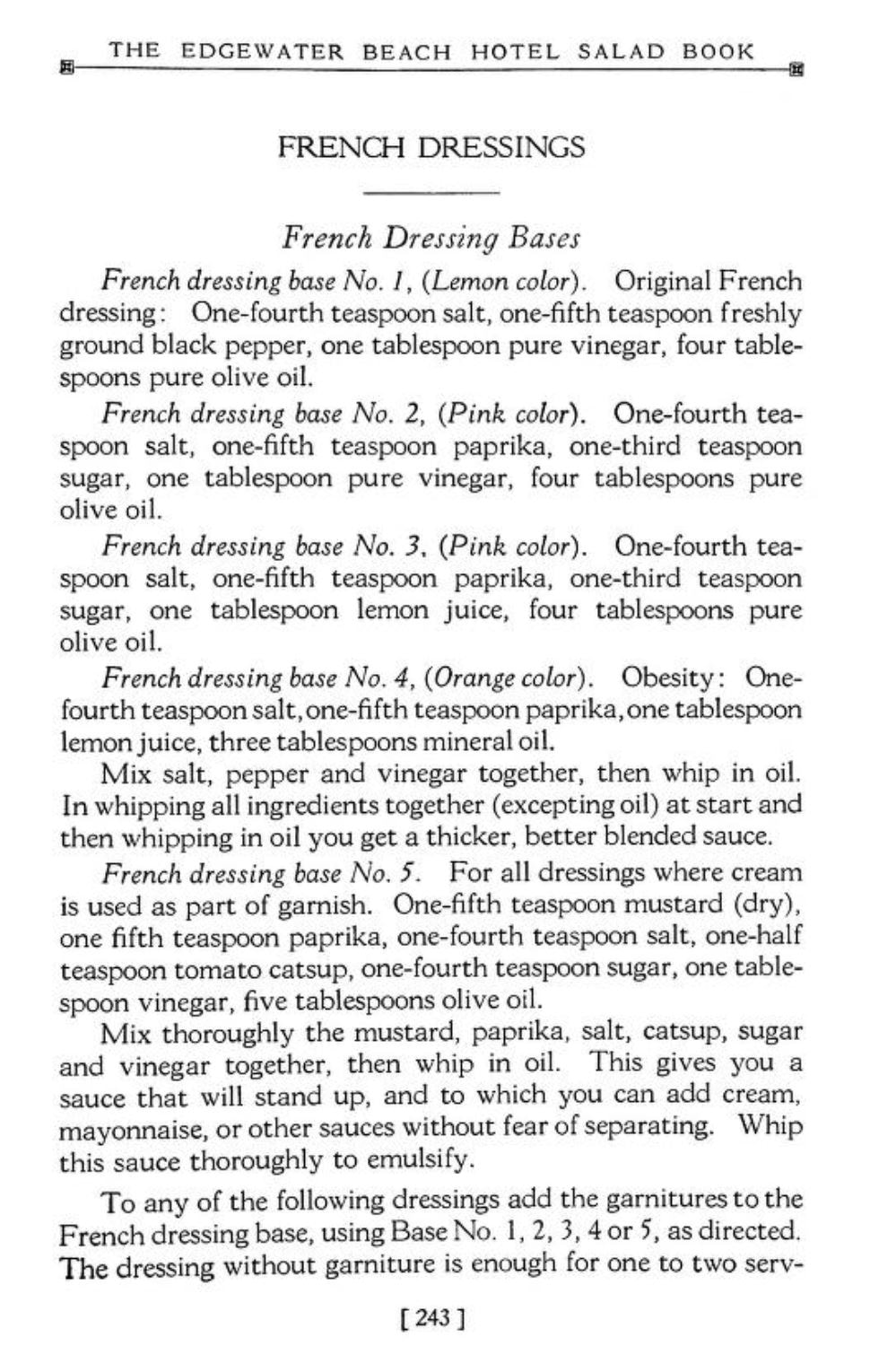

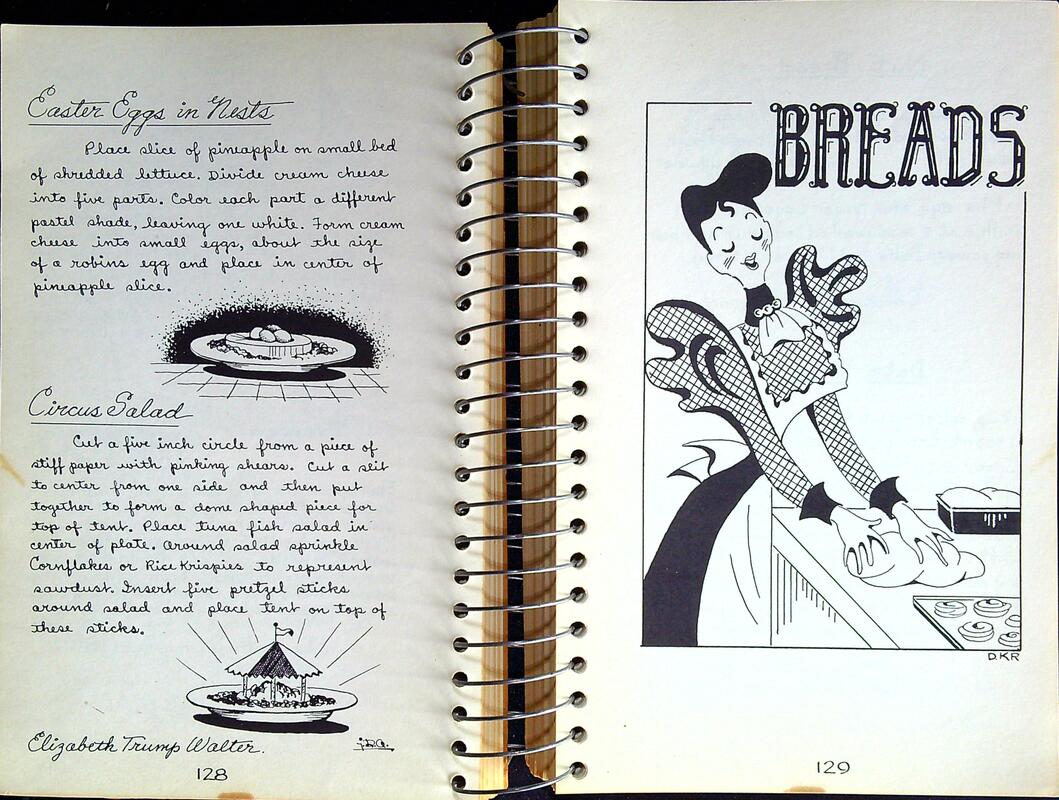

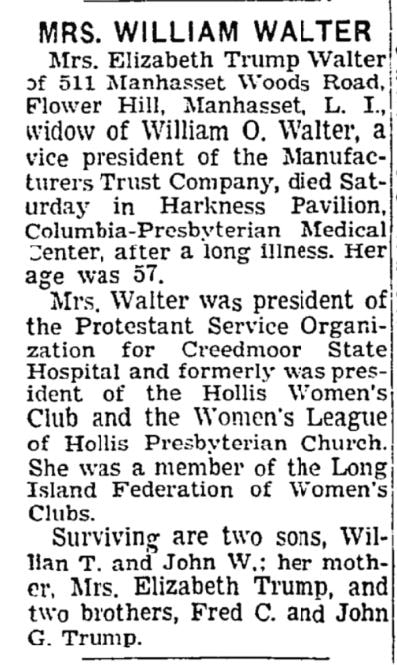

The recipes pictured above are from The Edgewater Beach Hotel Salad Book, published in 1928 (Patreon patrons already got a preview of this cookbook earlier in the week!). The Edgewater Beach Hotel was a fashionable resort on the Chicago waterfront which became known for its catering and restaurant, and in particular its elegant salads. You'll note that several French Dressing recipes are outlined (they are also introduced first in the book), and are organized by color. "No. 4 (Orange Color)" has the note "obesity" not because it would make you fat - quite the opposite - its use of mineral oil was designed for people on diets. Although the fifth recipe does not note a color, it does contain both paprika and tomato "catsup," and all but the original and "obesity" recipes contain sugar. An increase in the consumption of sweets in the early 20th century is often attributed to the Temperance movement and later Prohibition.

By the 1950s, recipes for "French Dressing" that doctored up the original vinaigrette with paprika, chili sauce, tomato ketchup, and even tomato soup abounded. My 1956 edition of The Joy Of Cooking has over three pages of variations on French Dressing. Hilariously, it also includes a "Vinaigrette Dressing or Sauce," which is essentially the oil and vinegar mixture, but with additions of finely chopped pimento, cucumber pickle, green pepper, parsley, and chives or onion, to be served either cold or hot. All the other vinaigrettes have the moniker "French dressing." A Google Books search reveals an undated but aptly titled "Random Recipes," which seems to date from approximately mid-century, and which includes a recipe for Tomato French Dressing calling for the use of Campbell's tomato soup, and "Florida 'French Dressing'," containing minute amounts of paprika, but generous citrus juices and a hint of sugar. So maybe people were making their own sweetly orange French dressing at home after all?

There is some debate as to who actually "invented" the orange stuff, but while Teresa Marzetti may have helped popularize it, the general consensus is the Milani brand, which started selling its orange take in 1938 (or the 1920s, depending who you ask - I haven't found a definitive answer one way or the other), was the first to commercially produce it. Confusingly, the official Milani name for their dressing is "1890 French Dressing." The internet has revealed no clues as to whether or not the recipe actually dates back that far, but a 1947 New York Times article claims "On the shelves at Gimbels you'll find 1890 French dressing, manufactured by Louis Milani Foods. It is made, the company says, according to a recipe that originated in Paris at that time and was brought to this country after the fall of France. This slightly sweet preparation, which contains a generous amount of tomatoes, costs 29 cents for eight ounces." This seems like a marketing ploy rather than the truth, but who knows for sure?

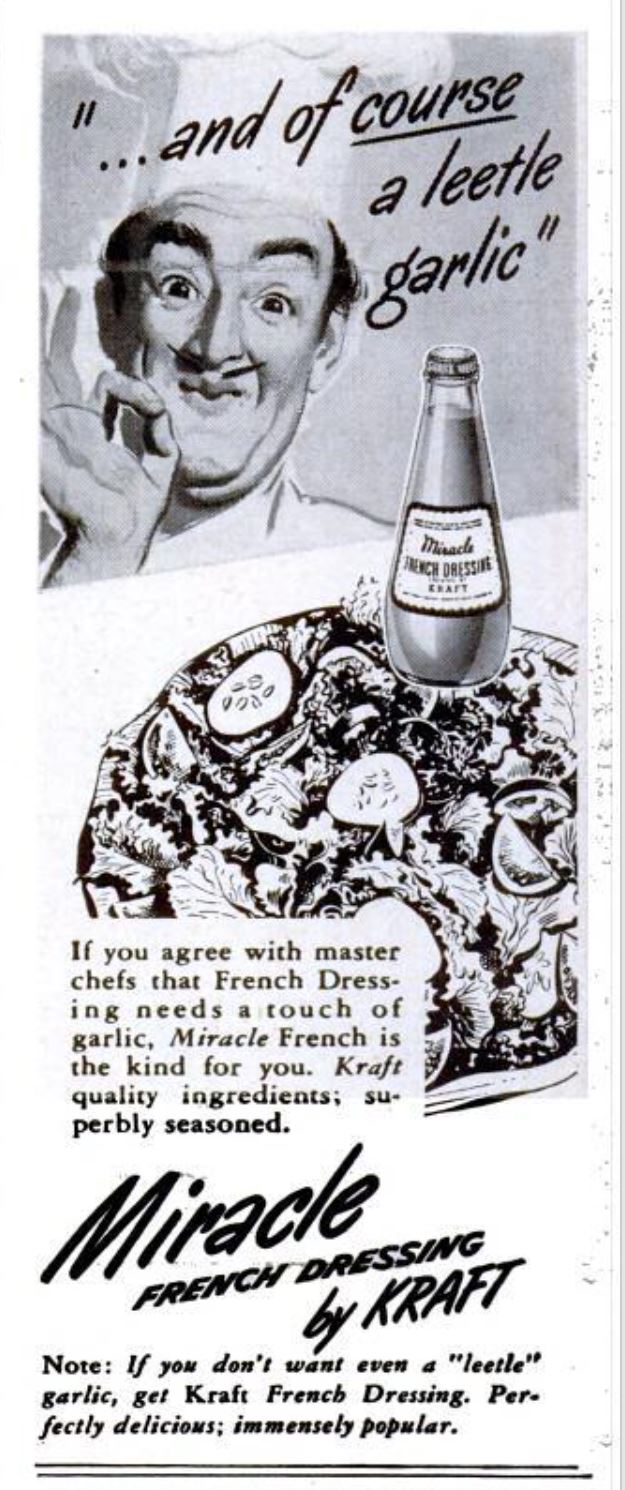

In 1925, the Kraft Cheese Company did sign a contract with the Milani Company to become their exclusive distributor. At least, that's what a snippet view of 1928 New York Stock Exchange listing statements tells me. As early as 1931 Kraft was manufacturing French Dressing under their name, and by the 1940s it had also used the Miracle Whip brand name to create Miracle French Dressing - which had just a "leetle" hint of garlic.

One snippet reference in the 1934 edition of "The Glass Packer" notes, "Differing from Kraft French Dressing, Miracle French is a thin dressing in which the oil and vinegar separate in the bottle, and which must be shaken immediately before using." Miracle French was contrasted often in advertising with classic Kraft French as being zestier, which may have led to the development in the 1960s of Kraft's Catalina dressing, a thinner, spicier, orange-er French dressing.

In fact, as featured in this undated magazine advertisement, Kraft at one point had several varieties of French Dressing including actual vinaigrettes like "Oil & Vinegar," and "Kraft Italian" alongside Catalina, Miracle French, Casino, Creamy Kraft French, and Low Calorie dressing, which also looks like French dressing. What you may notice is that the "Creamy Kraft French" looks suspiciously like most of the gloppy orange stuff you see on shelves today, and which generally doesn't resemble a thin, runny, paprika/tomato-red dressing that dominates the rest of this lineup.

"Spicy" Catalina dressing was likely introduced sometime around 1960 (although the name wasn't trademarked until 1962). Kraft Casino dressing (even more garlicky) was trademarked for both cheese and French dressing in 1951, but by the 1970s appears to have left the lineup. Here are a few fun advertisements that compare some of the Kraft French dressings:

Of course by the 1950s other dressing manufacturers besides Kraft were getting in on the salad dressing game, including modern holdouts like:

Although many people in the United States grew up eating the creamy orange version of French Dressing, it's mostly vilified today (aside from a few enthusiasts). Which is too bad. As a dyed-in-the-wool ranch lover (hello, Midwestern upbringing - have you tried ranch on pizza?), I try not to judge peoples' food preferences. And I have to admit that while I've come to enjoy homemade Thousand Island dressing, I can't say that I've ever actually had the orange French! Of any stripe, creamy, spicy, or otherwise. I'm much more likely to use homemade vinaigrette from everything from lentil, bean, and potato salads to leafy greens. So to that end, let's close with a little poll. Now that you know the history of French Dressing, do you have a favorite? Tell us why in the comments!

The Food Historian blog is supported by patrons on Patreon! Patrons help keep blog posts like this one free and available to the public. Join us for awesome members-only content like free digitized cookbooks from my personal collection, e-newsletter, and even snail mail from time to time! Don't like Patreon? Join with an annual membership below, or just leave a tip!

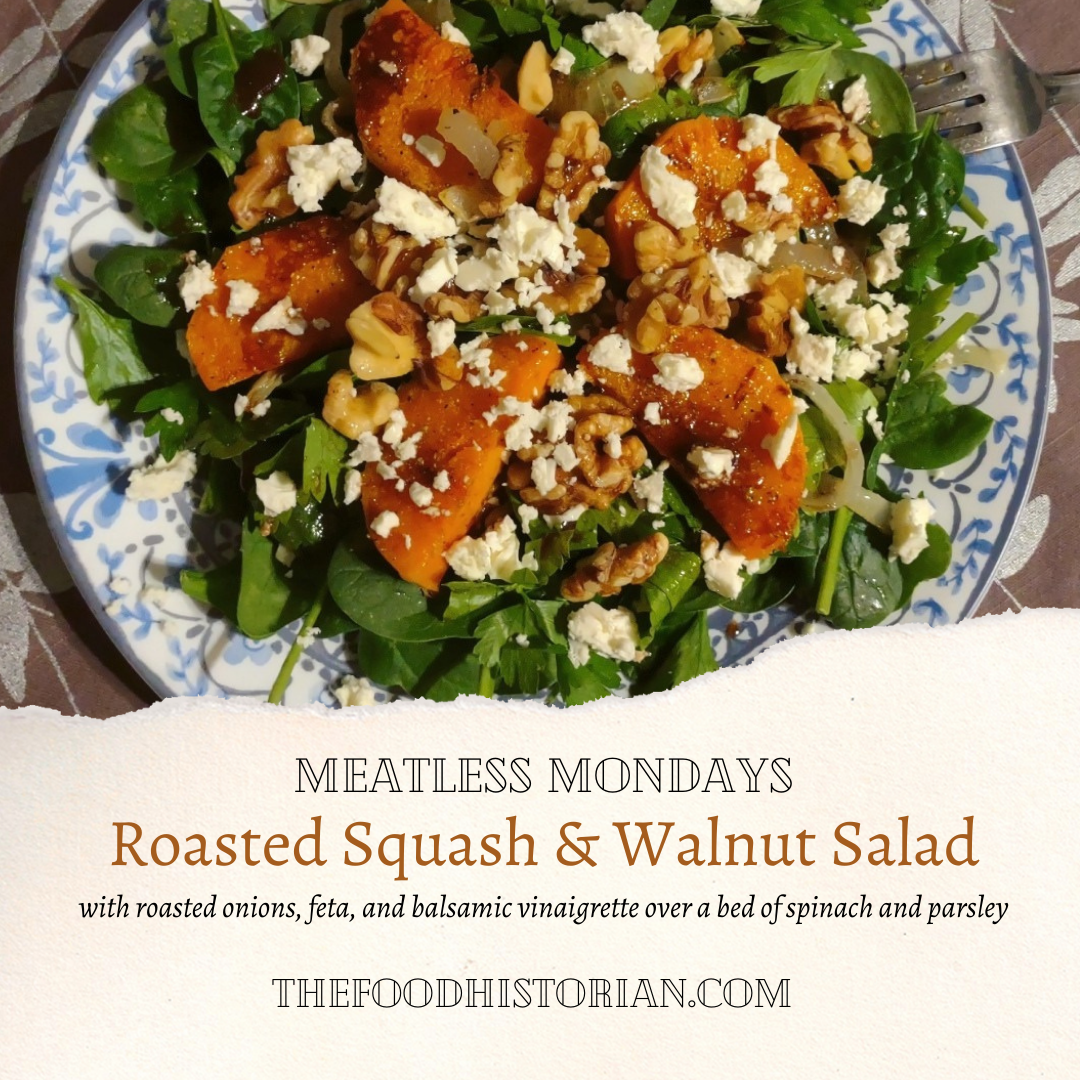

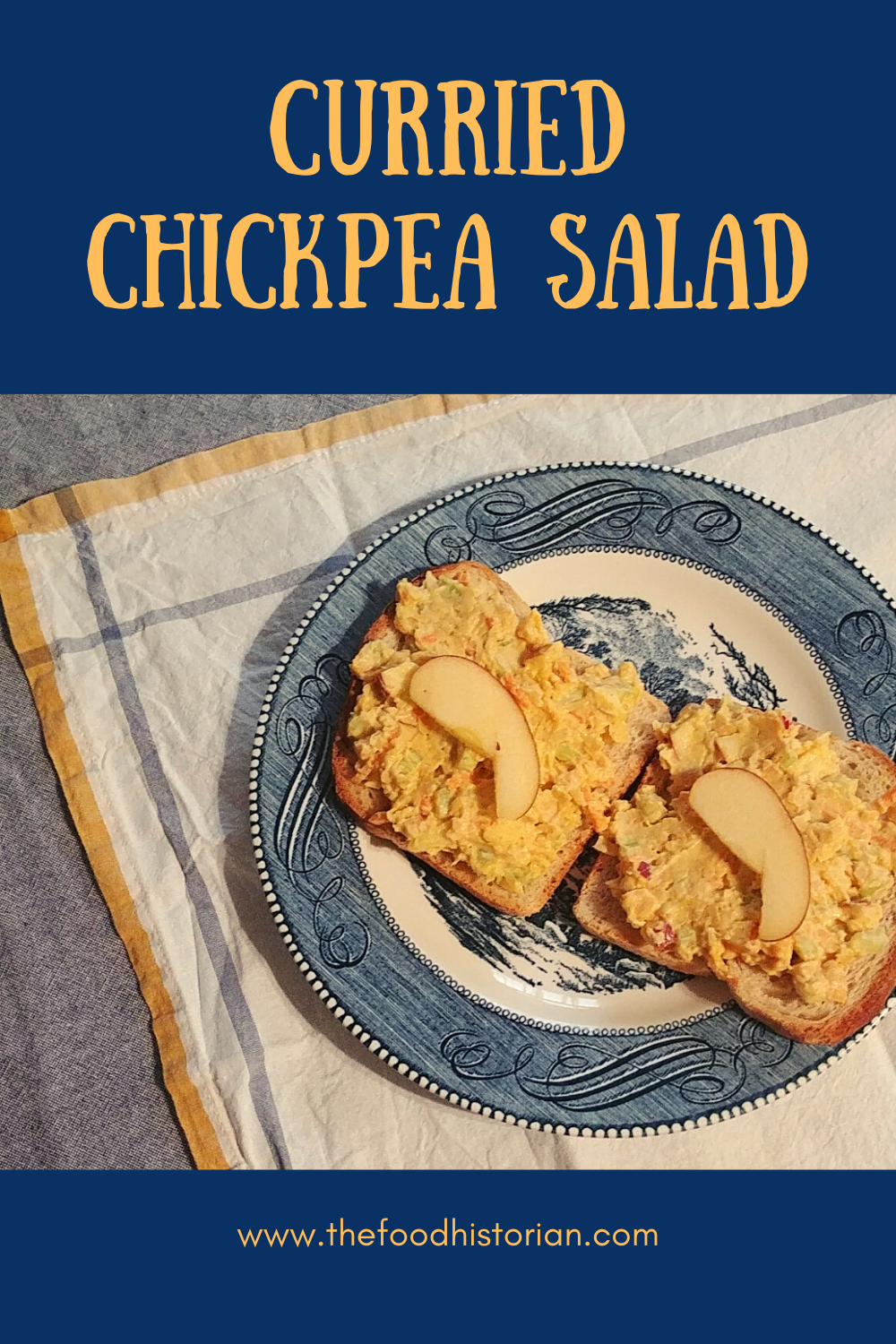

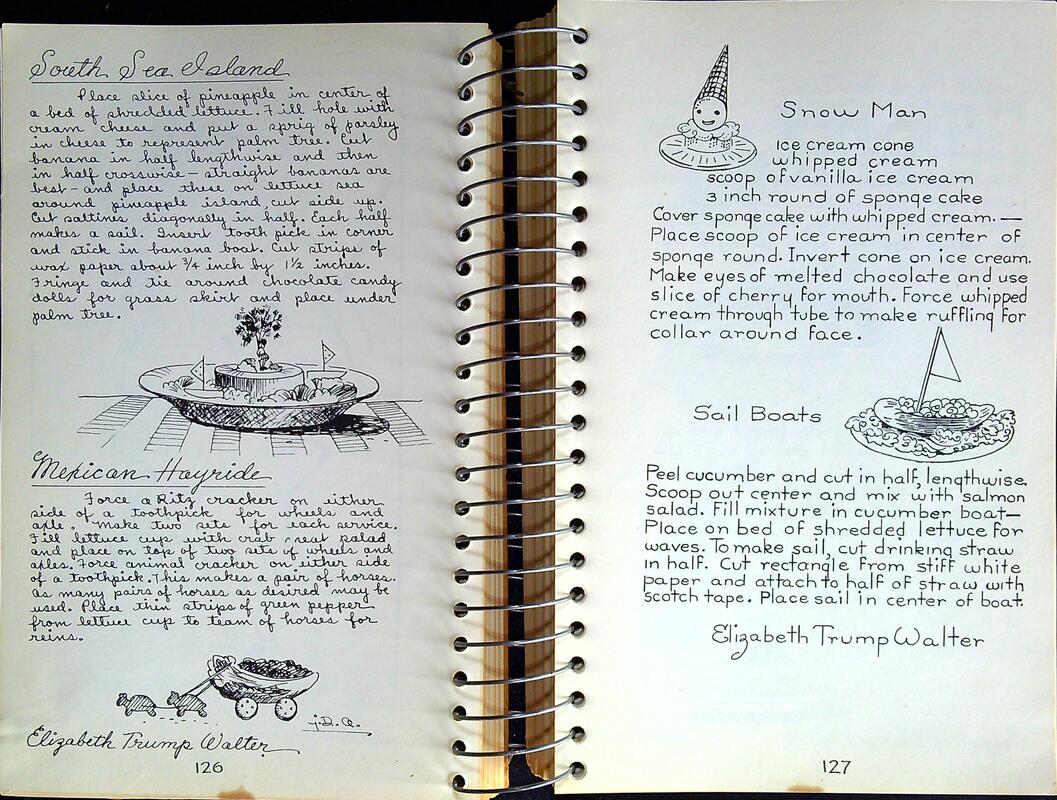

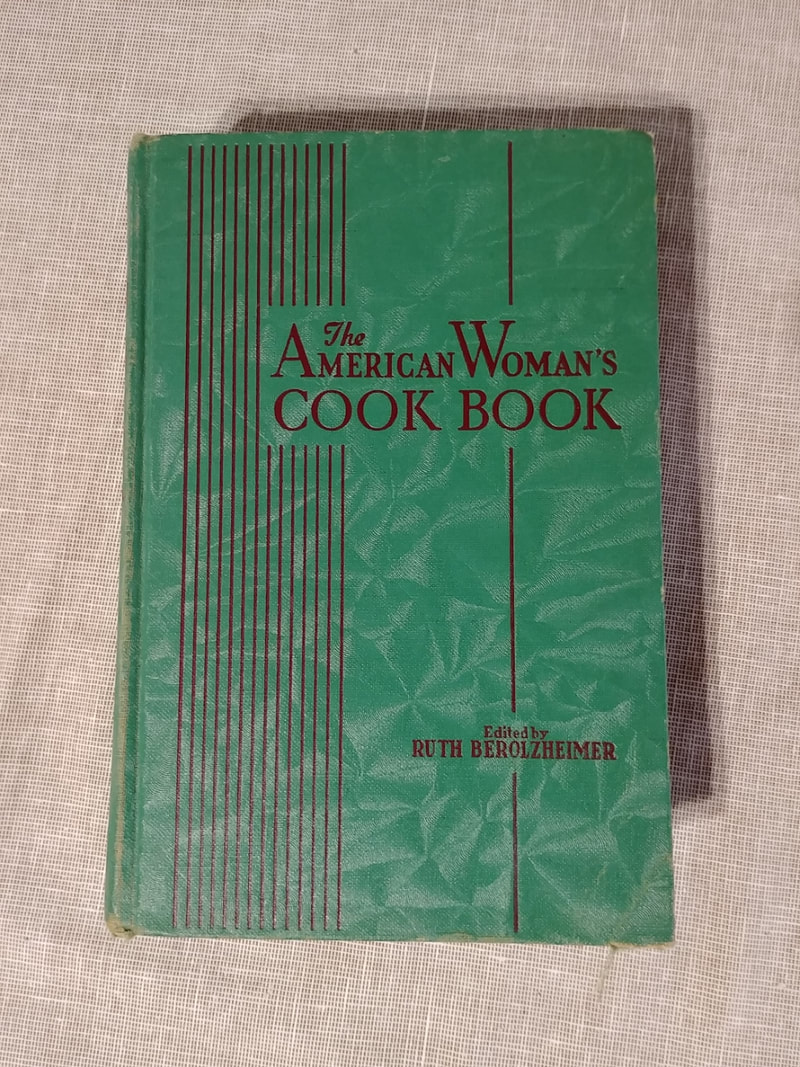

It's the depths of January. And after months of holiday eating, life can feel depressingly uninspiring when it comes to food. But while the imported tropical fruits beckon, it is possible to make a perfectly delightful dinner out of foods that are (mostly) in season here in the northeast. Enter the butternut squash. I'm typically not a huge fan. Butternut squash soup is usually much too sweet. Mashed squash is insipid and mealy. But when a Patreon patron posted about making Emily Nunn's delicata squash salad with parsley and walnut vinaigrette and raved about it, I was intrigued. I didn't have delicata squash, just one lonely little butternut left over from my impulse buy Thanksgiving CSA haul. I did have a big bunch of parsley, but I think it got a little frosty in the frigid temperatures we've been having lately, so bits were crispy and wilted. It would take some sorting. I also had a bottle of walnut oil I'd bought last year, and mostly hadn't used, which was set to expire in February. In the fridge, half a block of the most deliciously creamy, salty, made-in-New-York cow's milk feta (the sheep's kind and I don't get along) was languishing. Inspiration was striking. I'm an inveterate tinkerer when it comes to cooking. Even the respected science of baking usually has me asking, can I put fruit in this? Can I substitute some whole grain flour? Do I really have to beat the eggs for three whole minutes? Even as I don't mess with the ratios otherwise. So it's no surprise that I would be clinically unable to replicate Emily's recipe as she wrote it. The bones were good, though, so I stuck to those. Here's what I came up with: Roasted Squash & Walnut SaladThis recipe seems complicated, but once the vegetables are cut and in the oven, it's a fair amount of waiting. You can do a pan of dishes or start a load of laundry or watch most of an episode of your favorite television show while you wait. 1 smallish butternut squash 2 smallish yellow storage onions walnut oil pink salt garlic powder black pepper dried sage walnuts feta (the good-quality, locally made wet kind) fresh flat leaf parsley fresh baby spinach balsamic vinegar Dijon mustard maple syrup Preheat the oven to 400 F. Generously coat a half sheet pan with walnut oil (you can use olive or canola, if you prefer). Wash butternut squash and cut neck into one inch rounds. Cut in half and with a sharp knife remove the peel. I left the bulb end, cut it in half, scooped out the seeds, and roasted the halves whole with the rounds. Flip the half moons of squash in the oil so they're well-coated. Peel and halve the onions, cut into rounds, and add to the oiled pan. Combine about 2 tablespoons of pink salt, at least a teaspoon of black pepper, a few shakes of garlic powder and dried sage, and sprinkle the mixture all over the squash and onions. Roast for 30 minutes, flip, season again if you like, and roast for another 10 minutes or so, until the squash is crispy on one side and very tender, and the onions are tender. Scatter a generous handful of walnuts across the pan and roast another 3-5 minutes, until the walnuts are fragrant. Meanwhile, assemble your plate with the baby spinach topped with just the whole leaves of washed and dried parsley. Make a vinaigrette of about 3 tablespoons walnut oil, 2-3 tablespoons balsamic vinegar, and 1 tablespoon each Dijon mustard and maple syrup (add more syrup or a tablespoon of water if it seems too sharp). Top the greens with slices of squash, onions, and walnuts, drizzle over the vinaigrette, crumble feta on top, and serve while the vegetables are still warm. This salad is divine. The butternut squash came out silky and rich, the onions soft and not-too-sweet, the walnuts pleasantly crunchy, the parsley added some fresh, grassy tones to the milder spinach, and the sweet-sharp balsamic vinaigrette tied everything together. There was one slice of butternut squash left on the pan, so I tried it with some of the leftover onions and walnuts (which I stuffed in the cavities of the squash halves with the rest of the vinaigrette, for lunch tomorrow). To be honest, the squash was so good I could have eaten it just like that. But it really added so much satisfying heft to the salad. I don't think I'll ever make butternut squash any other way again. It was too delicious this way, and I could see it being the star of any number of other salads as well. It's hard to find satisfying, fresh recipes for winter eating that don't involve ingredients flown in from thousands of miles away. And while I love the wintertime treat of beautiful citrus, it's nice to be able to make something so delicious out of locally grown storage foods, too. I hope you enjoy this recipe as much as I did! The Food Historian blog is supported by patrons on Patreon! Patrons help keep blog posts like this one free and available to the public. Join us for awesome members-only content like free digitized cookbooks from my personal collection, e-newsletter, and even snail mail from time to time! Don't like Patreon? Leave a tip! I made curried chickpea salad last week, and it was so delicious, I thought I would share it for Meatless Monday. Although it is not a historic recipe, clearly it's a riff on curried chicken salad, which had its heyday in the mid-20th century, although you still see it on restaurant menus, especially tea rooms and bakeries and small cafes. It's not super clear when precisely curried chicken salad was invented, but there are lots of references throughout 19th century American cookbooks to all sorts of curried dishes - eggs, oysters, veal, cucumbers, shrimp, okra, and yes, chicken, although not in a salad until the 20th century. Country Captain is one of the first curry dishes in the United States, and may have inspired curried chicken salad in the 20th century. Made with browned chicken, onions, curry powder, tomatoes or tomato sauce, and golden raisins or currants, it was meant to be served over rice and likely originated in the Carolinas, where rice cultivation (fueled by slave labor) was common. It is called "country captain" because it was apocryphally introduced via a sea captain returning from India and/or involved in the spice trade. This savory, sweet, and mildly spicy flavor combination has been deemed by some historians to be the first fusion food in U.S. history. But it is unclear where curried chicken salad as made in the United States draws its roots. It may very well be from the flavor profile of Country Captain, and mayonnaise-based salads were exceedingly common by the turn of the 20th century. Some enterprising soul may have come up with the idea independently. However, in 1935, King George V of Britain celebrated his silver jubilee, and although I cannot find an original menu from the event, everyone swears a cold chicken dish with curried mayonnaise was part of the dinner (which some people thought was an unnecessary extravagance during the Great Depression). The dish was recycled (perhaps inadvertently) for Queen Elizabeth's coronation in 1953, this time with some fancier additions of tomato, pureed apricot, red wine, and whipping cream (try the original recipe). Jubilee chicken and coronation chicken, as the recipes have come to be known, are still quite popular in Britain, although they rarely show up on American shores under that name. At the same time, prior to Queen Elizabeth's coronation, we do have recipes in the United States calling simply for cooked diced chicken, mayonnaise, curry powder, and diced celery (like this one). Basically, plain jane chicken salad with some curry powder thrown in for flavor. This 1930 cookbook has a recipe for chicken salad with grapes or raisins, and a recipe for curry salad dressing (curry powder, vinegar, and mayonnaise), but the two aren't put together. So again, the official origins are unclear. But suffice to say, a curried chicken salad with celery and some variation of either golden raisins, currants, diced apple, and/or grapes has become an alternative to the more traditional (and boring) basic chicken salad. I chose to replace the chicken with canned chickpeas in part because poaching chicken is a drag and I hate the canned stuff. But also because not only are canned chickpeas easier and more accessible than poached chicken, they're a little healthier for the gut, too. Vegetarians and vegans often use chickpeas as a substitute for chicken or tuna. It turned out even better than I remembered from the last time I made it, and it seems appropriately vintage, even if it isn't actually historic. Curried Chickpea SaladA quick weeknight supper perfect for when it's too hot to cook, but equally at home at a tea party. To make this vegan, substitute all vegan mayonnaise for the yogurt and mayo. 2 cans (16 oz.) chickpeas, or 3 cups cooked from dried 3 ribs celery, minced 1/2 cup shredded carrots (I use the bagged kind) 1 small, sweet, crisp apple, minced 1/2 cup Greek yogurt 1/2 to 1 cup mayonnaise 1/2 to 1 tablespoon high quality curry powder salt & pepper to taste Drain and rinse the chickpeas, then mash roughly with a fork. I don't like any whole chickpeas in mine, but neither do I want a puree. Add the celery, carrots, and apple and mix well with a fork to combine. Add the yogurt and curry powder and mix, then add the 1/2 cup of mayo and mix. If too dry, add more mayo. Taste and add more curry powder, salt, and pepper if necessary. The warm spices of the curry powder set off the creaminess of the mayo and yogurt and the sweetness of the apple nicely, and the celery and carrots add crunch and texture. I like mine served open-faced on whole grain toast. The hubby prefers his sandwich closed on untoasted bread. You can also eat it with crackers, in a wrap, or frankly, with a spoon. If you want to try something more country captain style, add golden raisins and a little tomato paste. For something more coronation-style, try diced dried apricots or a few tablespoons of mango chutney. Add lemon or lime juice for tang, or leave it out. But whatever you do, don't use that little jar of curry powder that's been in the back of your spice cabinet for years. Get yourself a new jar or better yet, go to a store with a bulk spices section and get some fresh stuff that way. Have you ever had curried chicken salad? Or chickpea salad? Tell us your favorite quick weeknight dishes in the comments! The Food Historian blog is supported by patrons on Patreon! Patrons help keep blog posts like this one free and available to the public. Join us for awesome members-only content like free digitized cookbooks from my personal collection, e-newsletter, and even snail mail from time to time! Join by June 30, 2020 and get a picnic history packet mailed to your door! In 1946 the Women's League of the Hollis Presbyterian Church in Hollis, NY published this community cookbook, Hollis Pantry Secrets. Hollis is a neighborhood in Queens County, NY and in the 1940s was a relatively new development of single-family homes that had only been part of New York City since 1898, when it was developed from rural farmland. I was in the process of digitizing the cookbook when I ran across a somewhat familiar name. "Elizabeth Trump Walter." Could it be? Was she related to President Donald Trump? I started digging, but sadly, there wasn't much to find. Elizabeth was born in 1904 to Elizabeth Christ and Frederick Trump (Sr.), German emigrants to the United States. Frederick (sometimes spelled Friedrich) had made his fortune during the Gold Rush with a hotel specializing in alcohol and suites for prostitutes. He returned to Germany in sometime before 1902, only to run into trouble with the authorities, who deemed his emigration illegal because he had not completed his military service. He met and married Elizabeth Christ in 1902 and they moved to New York City. In 1904, homesick Elizabeth convinced him to return to Germany, but due to Frederick's trouble with the authorities over his lack of military service, they could not stay, and returned to New York City in 1905. It is unclear if Elizabeth the younger was born in Germany or not. Her younger brother Frederick Jr. was born in 1905 and John in 1907. Frederick Trump Sr. died of Spanish Influenza in 1918, and the family was soon in trouble financially. Elizabeth Christ Trump decided to continue her husband's work in real estate development, and that her children would be her primary employees. Elizabeth the younger was also the eldest child - she left high school to attend secretarial school so that she could be the accountant for the newly formed E. Trump and Son company. Her youngest brother John was to be the company architect. Fred Jr. the builder. John left the company early on and Fred Jr., with his mother, built E. Trump and Son into a real estate empire. Derailed by the stock market crash of 1929, when E. Trump and Son officially went out of business, by 1934 Fred Jr. managed to finagle his way into a mortgage-servicing contract, and the Trumps were back in the real estate business. The rest is fairly well-known history, including Trump's housing discrimination. But what about Elizabeth? Her history is almost non-existent. She has no Wikipedia page. She isn't even mentioned on her mother's Wikipedia page, despite the fact that Fred Jr. is noted as the "second child" and John the "third." She is mentioned on the Trump family page. We know she married William Walter, who was training to work in a bank, in June of 1929. According to William's 1959 obituary, he was a veteran of World War I who had worked in banks starting as a page boy in 1910. The year he and Elizabeth were married, he was made assistant secretary of the newly formed Manufacturer's Trust. Elizabeth apparently continued in her accounting role after marrying William, but it is unclear whether she left in late 1929 when E. Trump and Son went under, and whether she continued to work under Fred Jr. Elizabeth and William Walter had two children - William Trump Walter, born in 1931, and John Whitney Walter, born in 1934. Both Elizabeth and William Sr. were highly involved in the Hollis Presbyterian Church. He was an elder, she, a member of the Women's League. So it makes sense that Elizabeth would submit recipes for the 1946 cookbook. Here are her recipes: The "Party Suggestions" that start on page 125 is a small section that only contains recipes from Elizabeth Trump Walter! All variations on starter salads (with one exception), probably for ladies' luncheons, but possibly also for themed dinner parties, or even children's parties. South Sea Island Place slice of pineapple in center of a bed of shredded lettuce. Fill hole with cream cheese and put a spring of parsley in cheese to represent palm tree. Cut banana in half lengthwise and then in half crosswise – straight bananas are best – and place these on lettuce sea around pineapple island, cut side up. Cut saltines diagonally in half. Each half makes a sail. Insert tooth pick in corner and stick in banan boat. Cut strips of wax paper about ¾ inch by 1 ½ inches. Fringe and tie around chocolate candy dolls for grass skirt and place under palm tree. Mexican Hayride Force a Ritz cracker on either side of a toothpick for wheels and axle. Make two sets for each service. Fill lettuce cups with crab meat salad and place on top of two sets of wheels and axles. Force animal crackers on either side of a toothpick. This kames a pair of horses. As many pairs of horses as desired may be used. Place thin strips of green pepper from lettuce cups to team of horses for reins. Snow Man Ice cream cone Whipped cream Scoop of vanilla ice cream 3 inch round of sponge cake Cover sponge cake with whipped cream. – Place scoop of ice cream in center of sponge round. Invert cone on ice cream. Make eyes of melted chocolate and use slice of cherry for mouth. Force whipping cream through tube to make ruffling for collar around face. Sail Boats Peel cucumber and cut in half, lengthwise. Scoop out center and mix with salmon salad. Fill mixture in cucumber boat – Place on bed of shredded lettuce for waves. To make sail, cut drinking straw in half. Cut rectangle from stiff white paper and attach to half of straw with scotch tape. Place sail in center of boat. Easter Eggs in Nests Place slice of pineapple on small bed of shredded lettuce. Divide cream cheese into five parts. Color each part a different pastel shade, leaving one white. Form cream cheese into small eggs, the size of a robins egg and place in center of pineapple slice. Circus Salad Cut a five inch circle from a piece of stiff paper with pinking shears. Cut a slit to center from one side and then put together to form a dome shaped piece for top of tent. Place tuna fish salad in center of plate. Around salad sprinkle Cornflakes or Rice Krispies to represent sawdust. Insert five pretzel sticks around salad and place tent on top of these sticks. Her six party suggestions make up the entire "Party Suggestions" chapter. I, personally, would have a hard time cutting saltines in half or forcing toothpicks into crackers, so clearly this sort of thing took a great deal of finesse. Elizabeth Trump Walter died on December 4, 1961, at the age of 57, "after a long illness," just two years after her husband William. Her obituary is on page 37 of that day's New York Times, towards the bottom. She pre-deceased her mother Elizabeth Christ Trump by five years. Ironically, Elizabeth Christ Trump does not have an obituary in the New York Times, she is only listed among the deaths recorded on June 9, 1966 - her notice submitted by the Federation of Jewish Philanthropics. According to Elizabeth's son John Walter's 2018 obituary, the Walters moved to Manhasset, NY toward the end of their lives. They lived in a retirement home built by the Walters and likely Fred Trump, Jr., but died just a few years later. John begun attending the Congregational Church of Manhasset at his mother's behest. Elizabeth Trump Walter was memorialized with a restored organ at the Congregational Church of Manhassett, NY sometime in recent years. Elizabeth Trump Walter rarely shows up in Trump family histories, probably because of her early death compared with the Trump family fortunes. But it was a fascinating project to track down what I could about her. The Hollis Pantry Cook Book has more secrets and famous recipe authors to share, so stay tuned for future blog posts. Have you ever found a famous person's name in a community cookbook? Tell us in the comments! The Food Historian blog is supported by patrons on Patreon! Join us for awesome members-only content like free digitized cookbooks from my personal collection, e-newsletter, and even snail mail from time to time! For those of you who have been following along, this is part of my "Dinner and a Movie: White Christmas" series! I chose this salad as a menu starter for a variety of reasons. One, because I enjoy grapefruit and wanted something relatively simple and refreshing to counter the heaviness of some of the other items on the menu. But also because grapefruit was a very typical appetizer and salad ingredient from the 1930s through the 1960s. Pink grapefruit was first commercialized in the late 1920s and by then grapefruit in general had become a popular breakfast food. In the 1930s, with the rise of Hollywood and the ubiquitousness of citrus fruits in both California and the newly popular Florida as a vacation spot, grapefruit took on other guises. Broiled grapefruit became a popular appetizer and it was increasingly used in salads. Commercially canned grapefruit became available in the mid-1920s, which added to its popularity. So, in a movie that doesn't QUITE make Hollywood and California the star, but which definitely "visits" the tropics through the tropical nightclub in Florida, grapefruit seemed like a natural addition to the menu. This particular one is quite a simple recipe, from my 1942 edition of the American Woman's Cook Book by Ruth Berolzheimer, an extremely popular cookbook that was in print from 1938 through the 1960s. Grapefruit Salad (1942)The original recipe is quite simple. It reads: "Peel grapefruit and free the sections from all membrane and seeds. Cut sections in half, crosswise; lay on a bed of lettuce leaves and serve with French dressing. Sprinkle with tarragon leaves or with mint if desired." Supreming citrus (which is the official term for peeling and freeing citrus from the membrane) is extremely time-consuming work and doesn't always turn out how you'd like. Which is why if you'd rather use modern canned grapefruit, please feel free. The French dressing referred to in this recipe is NOT the modern, gloppy red stuff. It is, in fact, code for vinaigrette. I made my own, in my adaptation of the recipe, below. There's even a little maple syrup, to New England things up a bit. 1 large pink grapefruit for every two people 2 tablespoons olive oil 1 tablespoon maple syrup (optional) 1 tablespoon Dijon mustard thinly sliced red leaf lettuce Peel the grapefruit with a sharp knife over a small bowl to catch the juice. Using the knife, carefully cut each section away from the membrane on either side and cautiously remove, trying to keep the section intact. When done, squeeze the remaining pulp for juice into the bowl. Arrange the lettuce on each plate, then add the sections (you can cut them in half, or not). If you get 8 intact sections, you're doing better than I did. With a fork, mash up any remaining pulp into the juice (fish out any seeds), then add the olive oil, maple syrup, and Dijon mustard and whisk with the fork to combine. Pour the dressing over the sections and lettuce and serve. And that's it! Simple, if not easy (supreming is hard work!), and very tasty. The maple and the grapefruit flavors go very well together, although the dressing is a bit sweet. Do you think it goes with White Christmas (1954)? Let me know in the comments! And be sure to follow the White Christmas tag or visit the original menu post for the rest of the White Christmas Dinner and a Movie menu. Want to see more Dinner and a Movie posts? Make a request or drop your suggestions in the comments! The Food Historian blog is supported by patrons on Patreon! Join us for awesome members-only content like free digitized cookbooks from my personal collection, e-newsletter, and even snail mail from time to time!

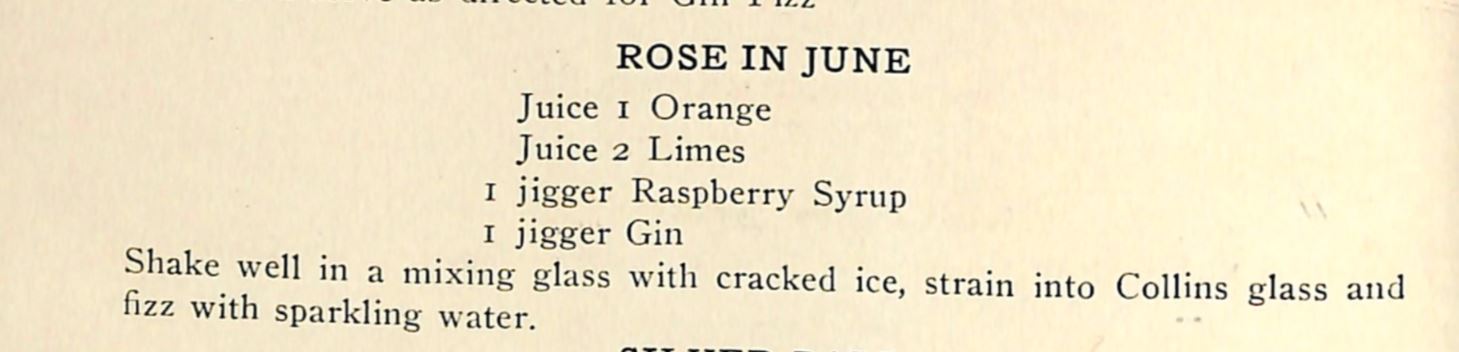

It's Juneteenth! Thanks to everyone who joined us for Food History Happy Hour. This week we make the Rose in June cocktail from the 1917 "Recipes for Mixed Drinks." We discussed Juneteenth, red velvet cake, victory gardens including propaganda and the exclusion of Black farmers and imprisoned Japanese Americans, the role of visuals in influencing taste, Black Food Historians You Should Know, disparities in book contracts, hot weather foods, salads, summer kitchens, how historical peoples coped without air conditioning, how historical peoples kept foods cold before refrigeration, ice and ice cream in the ancient world, rural electrification and electric refrigerators, the Frigidaire Cookbook, icebox pie, racial stereotypes in food advertising, including the history of the "Aunt" and "Uncle" terms, including Uncle Ben and Aunt Jemima, the history of the mammy trope, the tragedy of child caring roles, What Mrs. Fisher Knows About Old Southern Cooking, Black children in advertising, Franchise: the Golden Arches in Black America, the forthcoming book scanner I ordered, monuments and statues, and we ended with a signal boost for the James Hemings Society.

Rose in June Fizz (1917)

The "Rose in June" cocktail comes from the "Fizz" section of Recipes for Mixed Drinks by Hugo Ensslin (1917).

The original recipe calls for: Juice of 1 orange Juice of 2 limes 1 jigger raspberry syrup 1 jigger gin Shake well in a mixing glass (or cocktail shaker) with cracked ice, strain into Collins glass and fizz with sparkling water OR - if you don't have fresh citrus fruits OR raspberry syrup - you can substitute 1/3 cup orange juice, 1/4 cup lime juice, a heaping tablespoon of raspberry (or in my case, strawberry) jam, and the gin. Very nice, very refreshing, but sadly NOT pink.

Here's a roundup of links related to everything we talked about (in addition to all the links above!):

If you liked this post and would like to support more Food History Happy Hour livestreams, please consider becoming a member or joining us on Patreon. Members and patrons get special perks like access to members-only content.

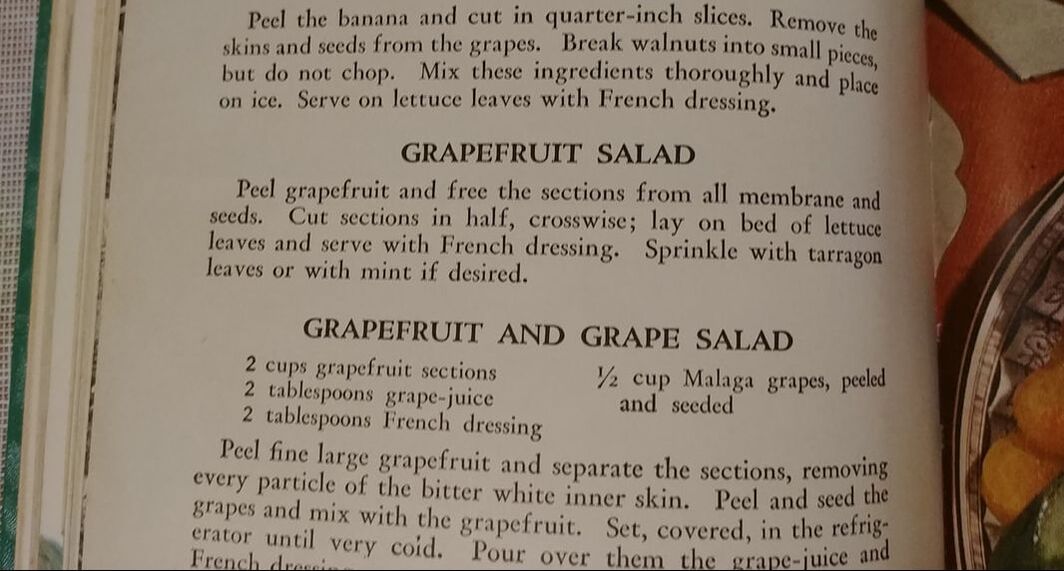

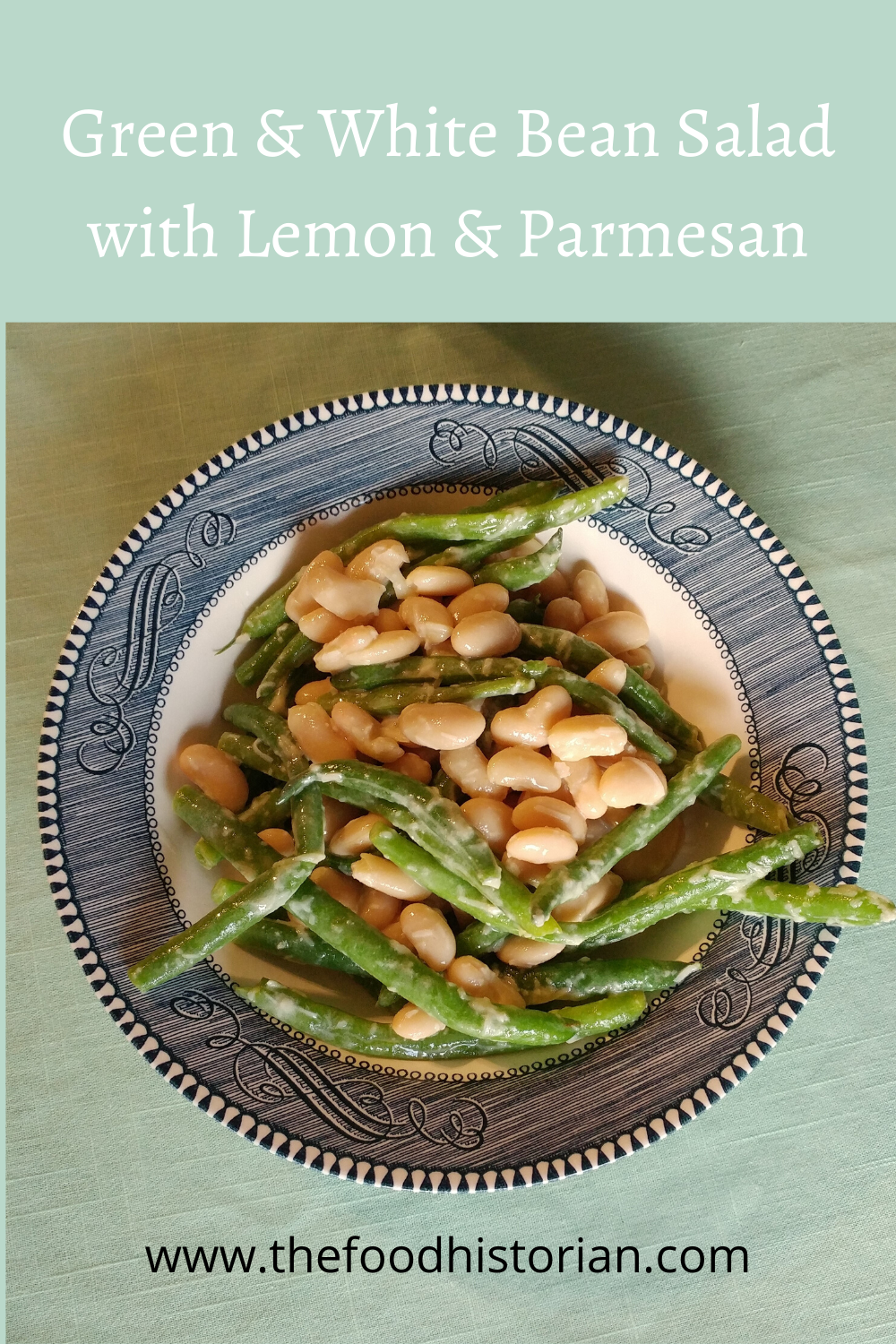

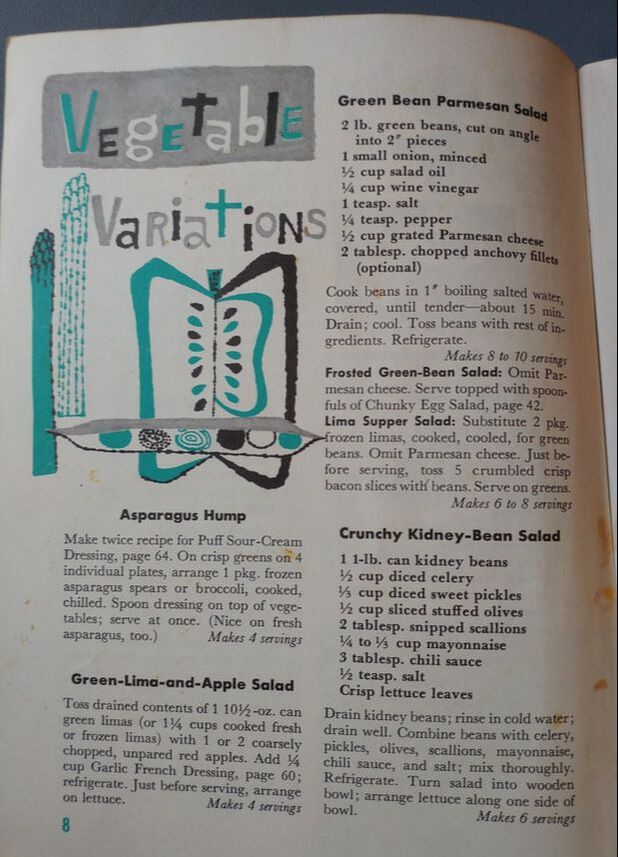

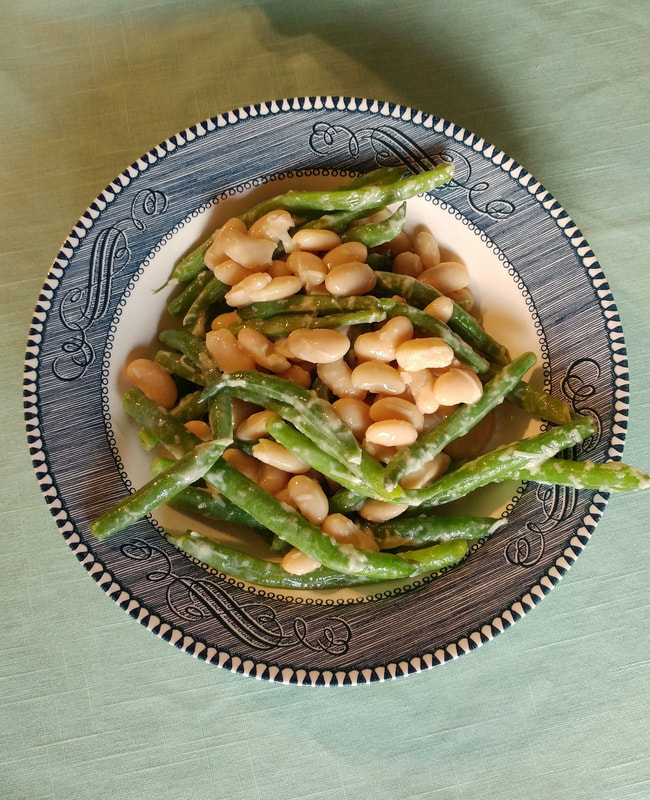

Many of my fans and patrons have been interested in and asking for more of what I call "sturdy salads" - lovely things made of vegetables and legumes and occasionally meats that can be stowed away in the fridge and eaten warm or cold or room temperature. One of our favorites is the Herbed Red Bean Salad I've made many times before. But it was very hot the other day, I was feeling green bean-ish, and was inspired by this little cookbooklet: Good Housekeeping's Book of Salads to heighten appetites and brighten meals (1958). When I made this salad I couldn't find the recipe that I KNEW had inspired it, but I finally tracked it down in this lovely little cookbooklet. Now, there are definitely a million recipes in here for gelatin-and-whipped-cream-based "salads," but there are a surprising number of sturdy vegetable salads - just the kind I like. Green Bean Parmesan Salad (1958)Here's the original recipe, in case the print is too small to read! 2 lb. green beans, cut on angle into 2" pieces 1 small onion, minced 1/2 cup salad oil 1/4 cup wine vinegar 1 teasp. salt 1/4 teasp. pepper 1/2 cup grated Parmesan cheese 2 tablesp. chopped anchovy fillets (optional) Cook beans in 1" boiling salted water, covered, until tender - about 15 min. Drain; cool. Toss beans with rest of ingredients. Refrigerate. Green & White Bean Salad with Lemon & ParmesanMy recipe was a riff on that original. I wanted something a little more substantial for a supper dish, and I thought lemon would be a nice addition to the vinaigrette with the Parmesan. I will say, if I were to make it again, I would actually remember this time to include either minced white onion soaked in lemon juice, or thinly sliced scallions (which I had! But forgot to put in). Diced celery would also not be remiss in this salad - it needs a little extra crunch. 2 cans white cannelini beans, drained and rinsed 1 pound green beans 3 tablespoons olive oil 3 tablespoons lemon juice 2 tablespoons cream (optional) 1 tablespoon dijon mustard 1/4 to 1/2 cup finely shredded Parmesan Bring a few inches of water to boil in a large stock pot. Snap the stem ends and any bad ends off the green beans. Add to the boiling water and cook, covered, for 3-5 minutes (15 is too long!) until bright green and tender. Meanwhile, mix the olive oil, lemon juice, cream, and mustard in a serving bowl and fold in the white beans. Add the hot green beans and mix thoroughly to coat with the dressing. Add the Parmesan and toss to mix well. Serve room temperature with toast. I will say - this would probably be better if you mixed the dressing and the white beans the day before to let the beans fully marinate before adding the green beans. Don't have cannellini beans? Substitute boiled cubed potatoes, steamed cauliflower florets, small white navy beans, or even pasta. Don't have green beans? Substitute asparagus, snow peas, frozen garden peas, or even broccoli. And if you're trying to stay away from carbs altogether, try a combination of just the green vegetables in the sauce. If you liked this recipe, please consider becoming a member or joining us on Patreon. Members and patrons get special perks like access to members-only content, and discounts on programs and classes.

|

AuthorSarah Wassberg Johnson has an MA in Public History from the University at Albany and studies early 20th century food history. Archives

July 2024

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed