|

Think about the story of Thanksgiving you grew up with - Pilgrims in black clothes and funny hats and white aprons and shoes with big buckles sitting down to a Thanksgiving dinner with "the Indians," celebrating peace and harmony and the harvest. Maybe you made a construction paper turkey by tracing your hand. Maybe your teacher made Pilgrim hats and bonnets and "Indian headdresses." The focus was on the food and American exceptionalism. The real story is much, much different. "The First Thanksgiving," in 1621 was preceded and followed by violence. Indigenous voices and the role of the Wampanoag people in literally saving the lives of the English separatists (they didn't call themselves "Pilgrims") have been purposefully erased. The legacy of Indigenous foods - cultivated and created by Indigenous people - has also been largely erased from our cultural lexicon. So what can we do about it? This year, you can decolonize your Thanksgiving by learning the real history behind it and familiarizing yourself with the various Indigenous nations in your own backyard and who played an important role in American history. Today's blog post is essentially going to be a giant collection of articles to read and films to watch. I hope you take the time this weekend to read or watch a few with your family or friends and discuss (especially with your kids) the real story behind the myth. Mythbusting the First Thanksgiving What Really Happened at the 1st Thanksgiving from Voice of America What you learned about the ‘first Thanksgiving’ isn’t true. Here’s the real story - from USA Today via the Cape Cod Times The Real History Of The First Thanksgiving That You Didn’t Learn In School from All That Interesting Everything You Learned About Thanksgiving Is Wrong from the New York Times The Real History Of Thanksgiving Isn't The One You Learned In School—Here's How To Celebrate Smarter from Delish The Myths of the Thanksgiving Story and the Lasting Damage They Imbue from Smithsonian Magazine The true story behind Thanksgiving is a bloody one, and some people say it's time to cancel the holiday from Insider The Thanksgiving Myth Gets a Deeper Look This Year from the New York Times Meet the WampanoagMashpee Wampanoag Tribe The Mashpee Wampanoag Tribe, also known as the People of the First Light, has inhabited present day Massachusetts and Eastern Rhode Island for more than 12,000 years. After an arduous process lasting more than three decades, the Mashpee Wampanoag were re-acknowledged as a federally recognized tribe in 2007. In 2015, the federal government declared 150 acres of land in Mashpee and 170 acres of land in Taunton as the Tribe’s initial reservation, on which the Tribe can exercise its full tribal sovereignty rights. The Mashpee tribe currently has approximately 2,600 enrolled citizens. Learn more >>> Wampanoag History from the Wampanoag Nation 400 Years After the ‘First Thanksgiving,’ the Tribe That Fed the Pilgrims Continues to Fight for Its Land Amid Another Epidemic from Time Magazine In 1621, the Wampanoag Tribe Had Its Own Agenda from The Atlantic “OUR” STORY: 400 Years of Wampanoag History an online exhibit with short documentary films from Plymouth 400. U.S. Appeals Ruling In Mashpee Wampanoag Land Case from WBUR and the Cape Cod Times. Although the Mashpee Wampanoag won their case against the Department of the Interior, which had revoked their federal recognition, the US government is currently appealing that ruling. Hopefully that appeal process will cease in 2021. National Day of MourningThe National Day of Mourning was organized in 1970 in response to a specific event of the suppression of history. This is the 50th anniversary of that event. Here's some background on what led to the creation of the National Day of Mourning from the United American Indians of New England: "In 1970, United American Indians of New England declared US Thanksgiving Day a National Day of Mourning. This came about as a result of the suppression of the truth. Wamsutta, an Aquinnah Wampanoag man, had been asked to speak at a fancy Commonwealth of Massachusetts banquet celebrating the 350th anniversary of the landing of the Pilgrims. He agreed. The organizers of the dinner, using as a pretext the need to prepare a press release, asked for a copy of the speech he planned to deliver. He agreed. Within days Wamsutta was told by a representative of the Department of Commerce and Development that he would not be allowed to give the speech. The reason given was due to the fact that, "...the theme of the anniversary celebration is brotherhood and anything inflammatory would have been out of place." What they were really saying was that in this society, the truth is out of place. "What was it about the speech that got those officials so upset? Wamsutta used as a basis for his remarks one of their own history books - a Pilgrim's account of their first year on Indian land. The book tells of the opening of my ancestor's graves, taking our wheat and bean supplies, and of the selling of my ancestors as slaves for 220 shillings each. Wamsutta was going to tell the truth, but the truth was out of place. "Here is the truth: "The reason they talk about the pilgrims and not an earlier English-speaking colony, Jamestown, is that in Jamestown the circumstances were way too ugly to hold up as an effective national myth. For example, the white settlers in Jamestown turned to cannibalism to survive. Not a very nice story to tell the kids in school. The pilgrims did not find an empty land any more than Columbus "discovered" anything. Every inch of this land is Indian land. The pilgrims (who did not even call themselves pilgrims) did not come here seeking religious freedom; they already had that in Holland. They came here as part of a commercial venture. They introduced sexism, racism, anti-lesbian and gay bigotry, jails, and the class system to these shores. One of the very first things they did when they arrived on Cape Cod -- before they even made it to Plymouth -- was to rob Wampanoag graves at Corn Hill and steal as much of the Indians' winter provisions as they were able to carry. They were no better than any other group of Europeans when it came to their treatment of the Indigenous peoples here. And no, they did not even land at that sacred shrine down the hill called Plymouth Rock, a monument to racism and oppression which we are proud to say we buried in 1995. "The first official "Day of Thanksgiving" was proclaimed in 1637 by Governor Winthrop. He did so to celebrate the safe return of men from Massachusetts who had gone to Mystic, Connecticut to participate in the massacre of over 700 Pequot women, children, and men. "About the only true thing in the whole mythology is that these pitiful European strangers would not have survived their first several years in "New England" were it not for the aid of Wampanoag people. What Native people got in return for this help was genocide, theft of our lands, and never-ending repression. "But back in 1970, the organizers of the fancy state dinner told Wamsutta he could not speak that truth. They would let him speak only if he agreed to deliver a speech that they would provide. Wamsutta refused to have words put into his mouth. Instead of speaking at the dinner, he and many hundreds of other Native people and our supporters from throughout the Americas gathered in Plymouth and observed the first National Day of Mourning. United American Indians of New England have returned to Plymouth every year since to demonstrate against the Pilgrim mythology. "On that first Day of Mourning back in 1970, Plymouth Rock was buried not once, but twice. The Mayflower was boarded and the Union Jack was torn from the mast and replaced with the flag that had flown over liberated Alcatraz Island. The roots of National Day of Mourning have always been firmly embedded in the soil of militant protest." You can learn more about the United American Indians of New England and their mission and watch a livestream of their National Day of Mourning program live from Plymouth here: http://www.uaine.org/ Not all Native Americans celebrate Thanksgiving. Find out why. from the Cape Cod Times. For Native Peoples, Thanksgiving Isn't A Celebration. It's A National Day Of Mourning from WBUR 400 Years After First Thanksgiving, Native Americans Honor 'Day of Mourning' Instead from Newsweek Indigenous Foods & Thanksgiving DinnerYou may recall my catalog of Indigenous foods a few weeks ago. The global impact of Indigenous agriculturalists is a staggering and often overlooked or ignored part of our history. Here are some books, films, and articles you can read to learn more about the impact of Indigenous food on our diet and the struggles of Indigenous chefs and historians to reclaim their food sovereignty. Indigenous Chefs On Traditional Cooking And Their Complicated Relationship With Thanksgiving from Delish Native Americans want to decolonize Thanksgiving with native foods and a proper history lesson KIRO radio Sean Sherman, The Sioux Chef: ‘This Is The Year To Rethink Thanksgiving’ from the Huffington Post This Thanksgiving, Make These Native Recipes From Indigenous Chefs from the Huffington Post 3 Indigenous Chefs Talk About What Thanksgiving Means to Them from Bon Appetit This Thanksgiving, try these recipes for local Native American foods from Kansas City Magazine How to Decolonize Your Thanksgiving Dinner by Vice “We are still alive”: How Native communities grapple with Thanksgiving’s colonial legacy from The Counter Films to Watch this ThanksgivingI cannot recommend the film Gather enough. You can rent it on Vimeo, Amazon Prime, or check their website for free screenings. It's stunningly filmed, it portrays a huge variety of Indigenous voices and stories, and it tells an amazing story of the effort of Indigenous people to reclaim their food sovereignty. Sean Sherman, also known as the Sioux Chef, has done a lot to bring national attention to Indigenous foodways. He's written a book and you can learn more about him on his website. Andi Murphy is the host of the Toasted Sister Podcast: Radio about Native American Food. Well folks if I want to get this done before midnight on Thanksgiving I have to stop, but stay tuned for another post on Indigenous Food Historians You Should Know, which I hope to get up soon. Featuring all kinds of amazing people, stories, books, and even more documentary films. I hope this collection of resources has helped you re-learn your American history and decolonize your Thanksgiving this and every year. As always, The Food Historian blog is supported by patrons on Patreon! Join us for awesome members-only content like free digitized cookbooks from my personal collection, e-newsletter, and even snail mail from time to time!

1 Comment

Thanks to everyone who joined us for Episode 23 of the Food History Happy Hour! In this episode, we discussed all things Thanksgiving, including the history of the First Thanksgiving, what foods likely were and were not present at that event, the importance of Indigenous foods in the development of the United States, how to honor Indigenous contributions at Thanksgiving and support Indigenous producers, how Thanksgiving came to be a national holiday, and the origins of many of Thanksgiving's most popular side dishes and desserts.

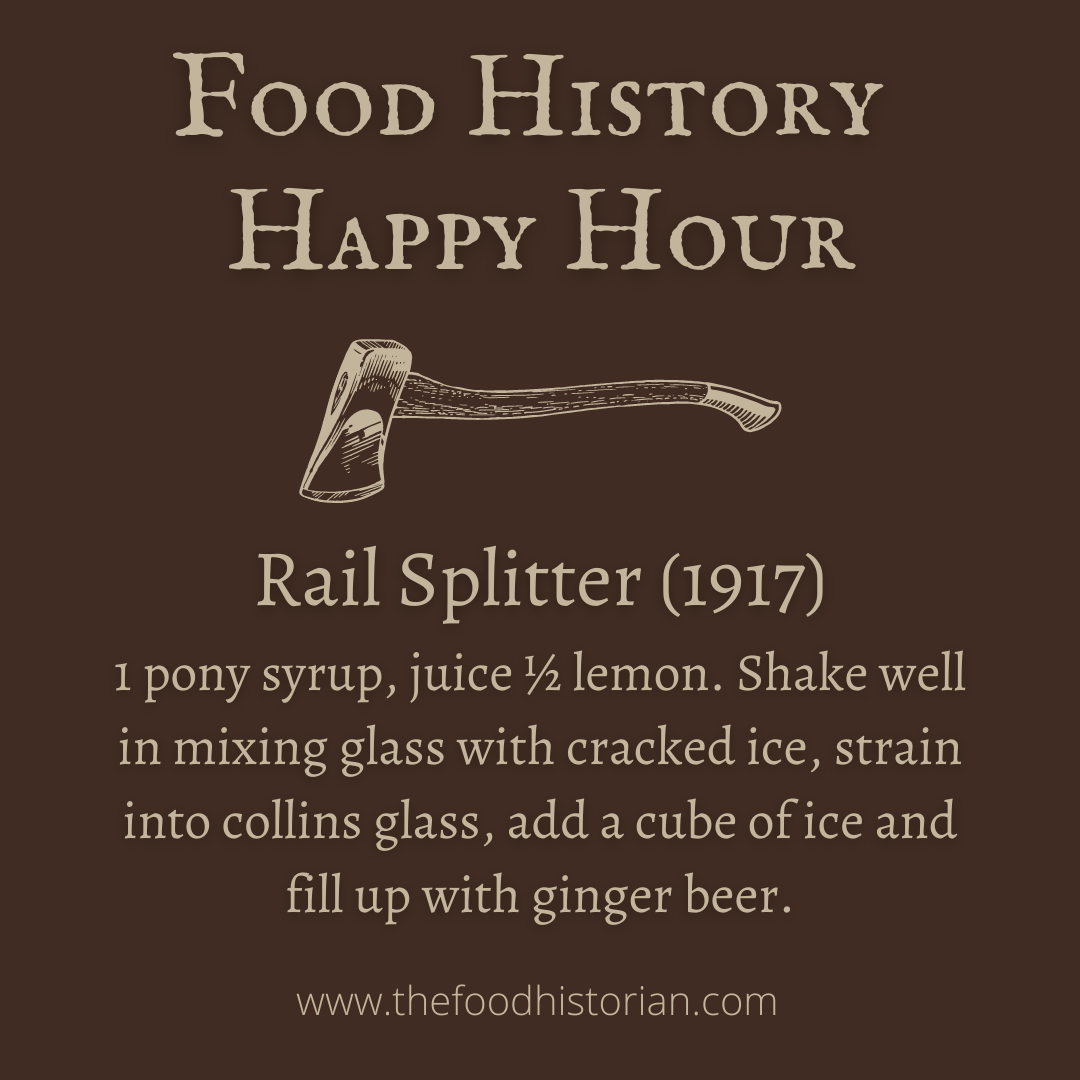

Rail Splitter (1917)

This recipe comes from the 1917 Recipes for Mixed Drinks by Hugo R. Ensslin. The original reads:

1 pony syrup, juice ½ lemon. Shake well in mixing glass with cracked ice, strain into collins glass, add a cube of ice and fill up with ginger beer. I substituted maple syrup for the simple syrup, but boy was that way too much syrup to use with modern ginger ale (I couldn't find ginger beer)! Ginger beer is likely stronger in flavor and less sweet, so go whole hog if you use that, but if you're not a fan of sweet drinks, go easy on the syrup. Episode Links

There are a ton of really great resources out there about Thanksgiving history and Indigenous foodways, but here are a few to whet your appetite:

Decolonizing Thanksgiving

In the episode we talked a little bit about the myths behind Thanksgiving and what it means to modern Indigenous people, but there's a lot more to be done. Here are some ways you can decolonize your own Thanksgiving, regardless of your cultural background.

Food History Happy Hour is supported by patrons on Patreon! Join us for awesome members-only content like free digitized cookbooks from my personal collection, e-newsletter, and even snail mail from time to time!

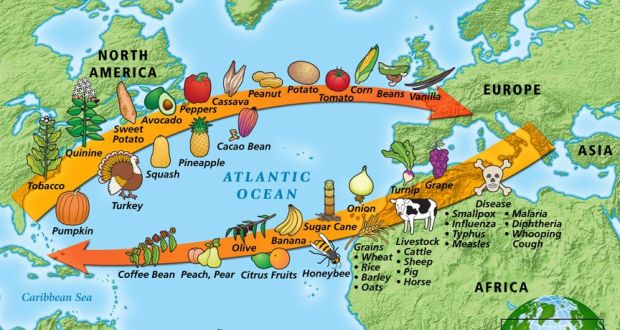

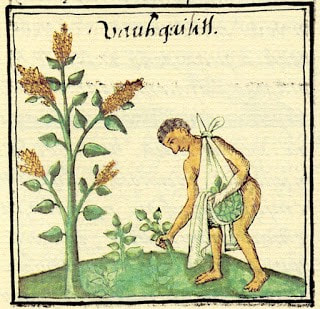

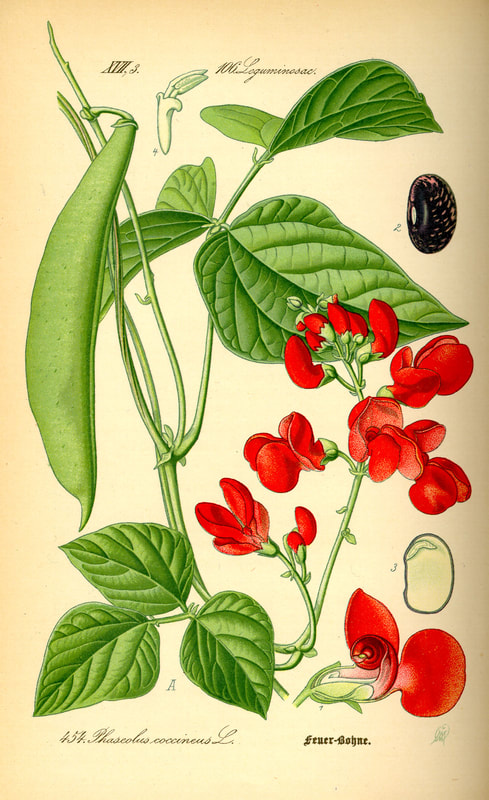

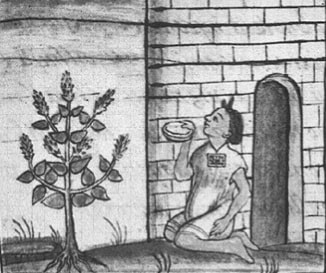

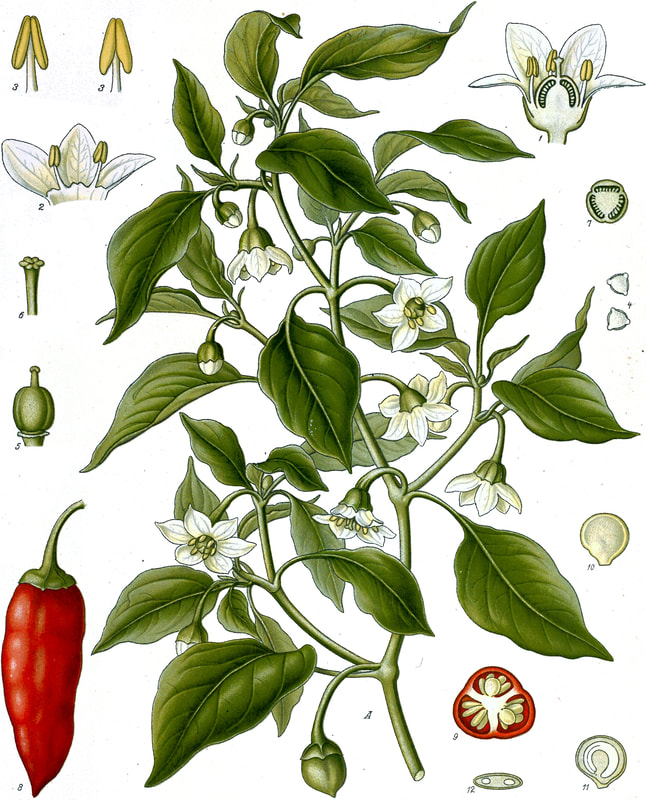

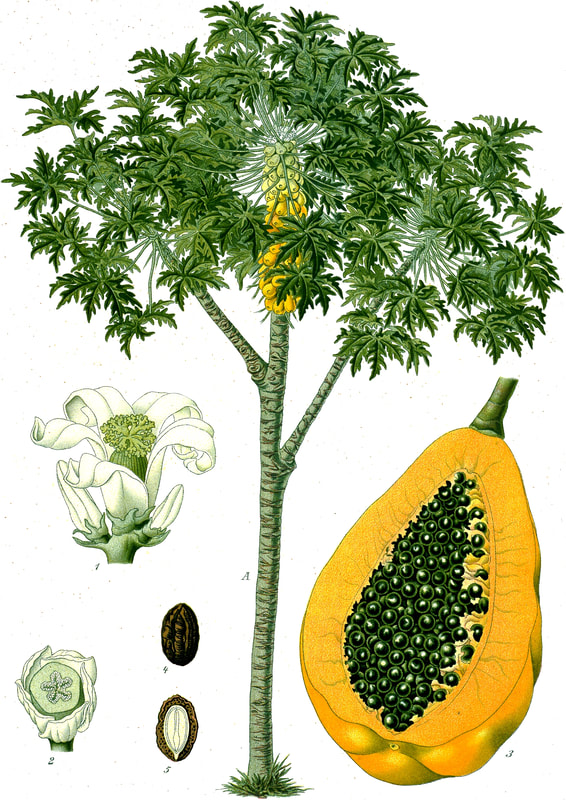

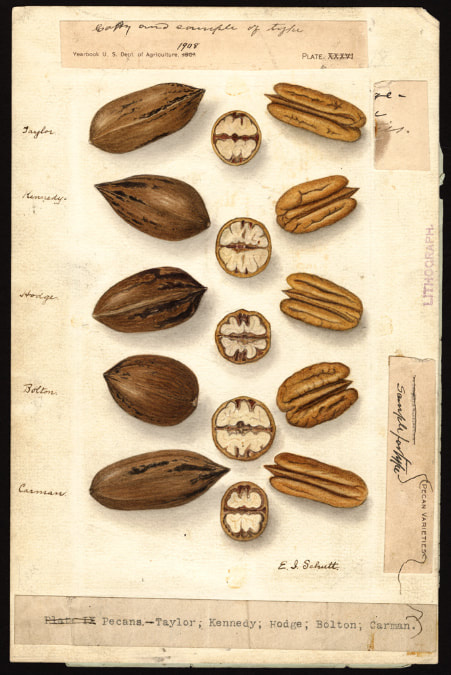

Today is Indigenous Peoples' Day. What, you thought it was Columbus Day? Well, for some people who don't know any better it still is, but Columbus was a pretty terrible person, driven by greed, and he didn't "discover" anything. Instead, he did things like sell 9 year old Taino girls into sex slavery, cut off children's hands if they didn't meet gold quotas, and generally committed genocide and slavery against every non-white person he met. He almost completely wiped out the Arawak-speaking peoples of the Caribbean, including the Lucayan people of the Bahamas and especially the Taino people of Hispaniola (present day Haiti and Dominican Republic). But as with most genocides, they're never 100% successful, and people throughout the Caribbean are descended from Taino people. One thing Columbus did lend his name to is a term called "The Columbian Exchange." The term was coined in the 1970s by historian Alfred W. Crosby, who studied the impacts of geography and biology on history, specifically the relationship between Europe and the rest of the world. Because Columbus was the first European to bring back many of the plants now used across the world, the exchange is named after him. Essentially, Irish potatoes, Italian tomato sauce, Swiss chocolate, Thai chilis, and a whole host of other important international foods are not actually from any of those places. They are ALL indigenous to North and South America and did not exist outside those continents prior to 1492. I'm going to catalog Indigenous American foodways in a minute, but first I want to emphasize how important it is to recognize that all of these foods are a result of Indigenous agricultural innovation. There is a tendency among many White folks to assume that these foods were just growing "wild" - and while that may be the case with some fruits, the vast majority were cultivated by Indigenous people, often in brilliant and surprising ways. And if you'd like to skip the list and go straight to figuring out where you can buy Indigenous foods and support Indigenous growers, harvesters, and producers, a good starting place is the list created by the Toasted Sister podcast. It's not comprehensive, but it's a great start. You can also check out this directory of certified American Indian Foods producers by the Intertribal Agricultural Council. You can even search by state! A small disclaimer - this is obviously not a complete list of Indigenous foods - I thought I would list the most influential foods globally and in the modern American diet. But I encourage you to use the magic of the internet to see what other foods you can find Indigenous to the area you live. And one final note - while it is important to preserve Indigenous foods and seeds, it's equally important to support the Indigenous people working to preserver them, like the Indigenous Seed Keepers Network. So while groups like Seed Savers Exchange are great, I encourage everyone to seek out Indigenous-owned and Indigenous-led companies and groups when choosing who to support. AmaranthWhere I grew up on the Northern Plains, in Lakota territory, one species amaranth is often known as "pigweed," and is considered a noxious weed by farmers. But Indigenous people know it as an important grain crop. Developed by the Aztec, amaranth was banned by the Spanish. The leaves of amaranth are also edible and some varieties are known as "callaloo," an important green vegetable for enslaved African peoples throughout the Caribbean and southern United States. If you're a gardener, "love-lies-bleeding" is a decorative variety of amaranth. There are dozens of varieties, but amaranth grains are often available for purchase from specialty stores and online. AvocadoAvocadoes, modern purview of hipsters, are actually an ancient fruit developed near Puebla, Mexico nearly 10,000 years ago (seriously, the world owes so much to Mexico in terms of agricultural innovation). The Indigenous residents of Puebla began cultivating the tree as much as 5,000 years ago. Modern-day avocadoes come in a whole host of varieties, but residents of the U.S. are most familiar with the Hass variety. Introduced to the American Southwest in the 1830s, avocado consumption in the United States didn't really take off nationally until the 1930s, influenced by California cuisine and used primarily in salads. Look in old cookbooks for references to "alligator pears," so named because of their bumpy green skin and pear shape. BeansBeans, especially climbing pole beans like the scarlet runner bean, are an important component of the Three Sisters style of agriculture, in which pumpkins or squash, corn, and beans are grown in concert with each other. The corn provides the stalk for beans to climb, the beans fix nitrogen in the soil for the corn and squash, and the broad leaves of the squash shade the ground, helping to prevent competing plants from growing and keeping the soil moist. Although some varieties of legumes did exist in Europe prior to the Columbian Exchange, notably chickpeas, peas, lentils, and broad beans, the introduction of the wide variety of cultivated Indigenous beans to Europe, especially kidney beans, including what would become the famous Italian cannelini. Black beans, pinto beans, and pink beans are other Indigenous varieties. Blueberries Image of the Weymouth variety of blueberries (scientific name: Vaccinium corymbosum), with this specimen originating in New Jersey, United States. Source: U.S. Department of Agriculture Pomological Watercolor Collection. Rare and Special Collections, National Agricultural Library, Beltsville, MD 20705, 1940. Lowbush blueberries (often marketed in grocery stores as "wild" blueberries) are native to North America, as other other blueberry-like fruits including huckleberries and juneberries (also known as serviceberries). Although these plants grew wild, blueberry barrens and other stands were often maintained by Indigenous peoples. Dried blueberry and cracked corn mush may have been served at the First Thanksgiving. Early European observers misnamed them "bilberries," after a relative native to Britain. In the early 20th century, highbush blueberries were cultivated from Indigenous blueberries in New Jersey. Highbush blueberries are bigger and therefore easier to harvest and ship than lowbush blueberries and are most often what you'll find in grocery stores today. CashewMost people probably associate cashews with Southeast Asia and Indian cuisines. But cashews are actually native to Brazil. The word "cashew" is a corruption of the word "acaju," which is Tupi for "nut." The Tupi people (of which there are dozens of sub-tribes) were who the Portuguese encountered when they first arrived there in the early 1500s. It was the Portuguese who brought the cashew to Goa, India in the late 1500s, where it thrived. Today, most commercially produced cashews are grown in India. ChiaMaybe you've noticed the trend for chia puddings these days. Or perhaps you're old enough to remember the Chia Pet craze of the 1980s. But the origins of chia are much older than you might suppose. Native to Central America, chia is thought to have been cultivated by the Aztecs as much as 3,500 years ago. An important staple crop throughout Mesoamerica, it was likely also used for religious purposes and may have been banned by Spanish colonizers for that reason. Thankfully, it survived. Chilis & PeppersChili peppers - from which all modern capsicums are derived, including bell peppers - were cultivated in Mexico as early as 6,000 years ago. Self-pollinating, chilis quickly spread throughout Mexico and Central and South America. Known in many countries by their cultivar name - capsicum - in the United States we call them "peppers" because Columbus and other Europeans associated them with the heat they had previously only known from black pepper. Like cashews, chili peppers were brought to Southeast Asia by Portuguese traders, where they quickly took hold as an essential part of many Asian cuisines. In the United States, New Mexico is best known for its production of chili peppers and its chili-eating heritage. Chilis are an essential ingredient in salsa, and Indigenous Mexican peoples use all different varieties (not just jalapenos and habaneros) for different levels of heat and flavor. ChocolateToday, chocolate is most often associated with Switzerland, Germany, and France. But its origins are ancient and date to Mesoamerica. The oldest references are for the Olmec peoples of central Mexico, who used it in religious ceremonies. But it was also used by the Maya and Aztec peoples, who both used cocoa beans as currency and used chocolate beverages in daily life and religious ceremonies. Although the origin of cacao plants is contested, they appear to have been common in Central America and actively cultivated as early as 5,300 years ago. Chocolate's chemical signature is often tracked as part of archaeological digs, and recent finds have suggested that its use and cultivation are earlier and more widespread than previously known. When it was introduced to Europe, Europeans treated it much like they did another dark, bitter beverage - coffee - by adding cream and sugar to it and drinking it for breakfast. By the 18th century, mechanization and slavery had made chocolate affordable to the middle classes. But it wasn't until the 19th century that chocolate bars, mixed with vanilla, sugar, dairy solids, and cocoa butter, came into widespread use. Corn (Maize)For most Americans, corn is hybridized sweet corn, popcorn, and maybe yellow or white cornmeal (or grits). But corn comes in thousands of different varieties and can be processed in hundreds of different ways. Did you know, for instance, that different varieties of corn - popcorn, dent, flint, flour, etc. - were cultivated for different uses? And that most corn can be eaten at all stages of development? And that "sweet" corn was originally just eating immature "green" corn before the sugars had turned to starch? Indigenous cooks also developed nixtamalization - a process whereby corn is soaked in wood ashes and water (i.e. lye) to de-hull and soften the corn. Nixtamalization also has the important additional benefit of releasing the niacin (Vitamin B3) from the corn so that it can be processed by the body. Niacin deficiency, also known as pellagra, plagued 19th and early 20th century White Americans, who did not know how to process the corn properly. Corn was developed from a grass native to south central Mexico called teosinte - which is still used today in Mexico as a fodder for livestock. As cultivated varieties spread throughout North America, they took on different characteristics as they cross-pollinated with other varieties and native species of teosinte. Corn is wind pollinated, meaning that it cross-breeds easily. Today, corn's global dominance is almost entirely related to its role as livestock feed, especially with beef. Sadly, beef cattle are not well suited to being raised on corn, and "corn fed beef," which is designed to put on a lot of fat for your "well-marbled" steak, is actually extremely destructive to bovine digestive systems. Not to mention unhealthy for humans, too. American agricultural subsidies for corn, which allow food processors to purchase it for less than it costs farmers to produce, have also allowed the proliferation of its use as an industrial food, notably corn syrup, but corn is now in almost everything we eat. And not in a good way. If you want to help Indigenous producers, buy Indigenous-grown Indigenous corn products. Here in New York, you can buy Iroquois White Corn. Don't feel like eating corn but want to help? Support Indigenous seedkeeper groups. Can't find one in your area? Donate to the Indigenous Seedkeeper's Network. CranberriesToday, cranberries are most often associated with Thanksgiving and New England, but cranberries are native to the northeast of North America and were used often by Indigenous peoples in those areas. Although a variety of cranberry is native to the bogs of Britain, and the Scandinavian lingonberries are a relative, the vast majority of modern cranberry consumption is based on species native to the U.S. and Canada. Maple Syrup & SugarMaple Syrup is one of the few sweeteners native to North America (honeybees, sugar cane, sorghum, and sugar beets are all imported). First used by Indigenous peoples in the Northeast, it is unclear which tribes first started use of maple sap as a sweetener. One Haudenosaunee/Iroquois legend indicates that the people first observed red squirrels cutting into the bark of maple trees and returning to drink the sap that flowed out. This has since been confirmed by scientific observation of squirrel behavior. Maple syrup and sugar was made either by freezing the water out of the sap, or by boiling with heated rocks. European colonists were quick to adopt maple sugaring as an important source of late winter calories and shelf-stable year-round sweetener. Although for some reason in the United States maple products are associated with fall, maple sugaring time is usually in March, when daytime temperatures rise above freezing, and fall below freezing at night - perfect conditions for optimum sap production. PapayaThe native range of the papaya is from southern Mexico to northern South America, although it has been naturalized throughout the Caribbean and the Gulf of Mexico. With a quick maturity - some papaya can produce fruit after just one year - Europeans spread the plant to other tropical regions around the world where it is widely used in many different stages of ripeness, both cooked and raw. PeanutsThe archaeological record of peanut cultivation is not clear, but it is clear that it was present in Brazil and Central America in the 16th century when European explorers arrived in South America. The peanut is not actually a nut - it is a legume and more closely related to beans than, say, pecans. But its culinary importance grew once it was imported by Europeans to Africa and Asia. The peanut actually came to North America by way of enslaved Africans, who carried it with them as they were stolen from their homelands. The peanut was largely regarded as animal fodder by Europeans, and used in subsistence farming by enslaved Africans and African-Americans in the U.S. In the late 19th century, a number of people, including John Harvey Kellogg and Heinz, were filing patents for peanut-butter-like substances. Ironically, George Washington Carver, African-American plant scientist and the man most associated with peanut butter, didn't actually invent it. Today, about the only people who don't enjoy peanuts much are Europeans, which is ironic given their role in spreading them globally. PecanNative to North America, the pecan is one of my favorite nuts. Its native range ran from New England to Mexico and was widely used by Indigenous peoples. The word "pecan" likely comes from a 16th century European corruption of the Algonquian word "pacane," describing nuts that required stones to crack. Hickory nuts (also known as butternuts) and black walnuts are in the same family as pecans. PineappleAlthough most Americans associate pineapples with Hawaii, they are actually native to the Paraguay River basin, which stretches between modern-day Brazil, Bolivia, Paraguay, and Argentina. Pineapples were cultivated by the Maya and Aztecs and Europeans first encountered them in the 15th century. Named the "pine apple" because of its resemblance to a pine cone and its status as a fruit, Europeans were able to grow some pineapples in greenhouses. In the 18th century, the pineapple was a symbol of hospitality and wealth and were much smaller than modern-day cultivars. Pineapple plantations were first installed by White Americans in Hawaii in the 1880s. James Dole made his fortune with pineapple plantations, processing, and canning innovations, which introduced the pineapple to ordinary Americans across the country. PotatoesWhat would Europe be without the potato? And yet, this starchy tuber, which spread throughout the Andes mountains prior to European contact, is originally from the border of modern-day Peru and Bolivia and dates back as far as 8,000 years ago. Cultivated from the wild tuber by Indigenous agriculturalists, over 5,000 varieties now exist. Potatoes were the staple crop of the Inca, who built their empire on it. Andean Indigenous peoples used it in all the usual ways, but also pioneered a special preservation technique called chuño, whereby the potatoes were frozen and dried in a way that made them very light and allowed them to keep for years. Chuño was usually prepared as part of a stew and was an important cash crop for Indigenous farmers. Prior to its introduction to Europe, most of the poorer classes relied on turnips and rutabaga for starchy bulk calories. But the potato was not only more palatable, it was more prolific, easier to grow, and it kept longer in storage. The shift to potatoes throughout Northern Europe in particular meant that the advent of potato blight in the mid-19th century, particularly in subjugated Ireland, started a mass migration of Europe's poor to the nations which had fed them so well for so long. QuinoaAlso native to the Andes and Peru, quinoa (pronounced "keen-wah"), is a member of the amaranth family. Used as a cereal crop by the Inca and other Indigenous peoples in the Andes mountains, quinoa has been in cultivation for as many as 5,000 years. When the Spanish arrived, determined to stamp out Incan culture, quinoa almost disappeared, but it persisted. Its "discovery" by White Americans interested in "superfoods," the price of this essential Indigenous grain actually skyrocketed. Whether or not this is good for Indigenous farmers is a matter of some debate, but when in doubt, be sure to buy from Indigenous producers. Squash & PumpkinAlong with corn and beans, squash make up the famous "Three Sisters" of Indigenous foodways. One of the oldest cultivated crops of the Americas, dating back as many as 10,000 years ago (before maize and beans), squashes are native to the Andes and Mesoamerica and wild varieties actually predate human inhabitation on the continents. Their cultivation was widespread throughout North and South America prior to European contact. All global varieties of squash, including pumpkins, zucchini, and decorative gourds, originated in the Americas. The word "squash" is an English corruption of the Narragansett word "askutasquash" meaning "a green thing eaten raw." Today, pumpkins (a word for a particular kind of large, round, orange squash that doesn't actually have an official classification) are mostly associated with Thanksgiving and New England foodways, although in the 19th century they were also stereotypically associated with slavery. They were one of the Indigenous foods featured in the first "American" cookbook, published by Amelia Simmons in 1796. SunflowerSunflowers are also native to North America, thought to have been cultivated near present-day Arizona and New Mexico around 3000 BC. Cultivated for their oily seeds and tuberous roots (also known as sunchokes or "Jerusalem artichokes"), sunflowers were also sometimes used as dyes. Although they were an important crop for Indigenous peoples, they were not in widespread use by European-Americans until their popularization in 19th century Russia, where they had been imported. Today, North and South Dakota are the biggest producers of sunflowers in the US and sunflower seeds, "sunbutter" and sunflower oil are popular modern uses. Not so much with the "sunchoke," although the tubers are regaining some popularity. Sweet PotatoSweet potatoes are native to Central America. Although called "potatoes" and sometimes "yams," they are not related to either plant. Sweet potatoes are more closely related to morning glory and bindweed. Sweet potatoes were spread across the Pacific nearly 400 years before Columbus by Polynesians, who brought the vine back with them. It was the Spanish and the Portuguese, however, who spread the sweet potato to the Philippines and Japan, respectively. The Spanish also brought the sweet potato to West Africa, where it was adopted, but not without some derision as its taste. The yam is native to Africa, which is likely why so many Americans, especially African-Americans, call sweet potatoes "yams." TomatoWhich is more authentic? Italian tomato sauce, or Mexican salsa? Hate to break it to you, but the Mexicans have the ayes on this one. Wild tomatoes are native to Western Mexico and were originally tiny, sour, and hard. Careful cultivation by Indigenous people led to thousands of more edible varieties, including husk tomatoes ranging from tomatillos to ground cherries. In Nahuatl (the Aztec language), "tomatl" was used to reference green tomatoes like tomatillos, and "xitomatl" was used for red varieties. The Spanish translated it as "tomate" and hence the term "tomato." When brought back to Europe, the bright red fruits were originally identified as a type of eggplant (both are members of the nightshade family), it garnered the nickname "love apple," and was originally considered poisonous. Although it was cultivated as a decorative plant, it was not in widespread use in Europe until the mid-18th century. It's widespread adoption in Italy was likely connected to nationalist sentiments in the 19th century and its association with the color red in the flag of Italian unification. In the United States, Thomas Jefferson may have helped popularize the tomato outside of the American southwest. And his relative by marriage, Mary Randolph, featured tomatoes in her Virginia Housewife cookbook, published in 1824. By the end of the 19th century, tomatoes became a popular American preserve, providing color, acidity, and sweetness to the typical American table. TurkeyIndigenous to North America, turkeys have been consumed by Indigenous peoples for centuries. Turkeys were domesticated in Mesoamerica as early as 800 BC. The Spanish brought back domesticated Aztec turkeys to Europe, where they quickly joined the European game bird lexicon. Associated with Christmas in Britain as early as the 17th century, the British Christmas goose persisted until the 20th century. In the United States, turkey is most commonly associated with Thanksgiving, although it is also often consumed at Christmas. Turkeys are one of the only indigenous American meat animals widely adopted in Europe and elsewhere. The name "Turkey" is likely associated with how Europeans were first introduced to turkeys - either through trade with the Middle East, or in association with guinea fowl as a game bird, introduced via Turkey. Domesticated turkeys are thought to have been descendants of Aztec domesticated birds reintroduced to North America via Europe. The turkeys purportedly eaten at the First Thanksgiving would have almost certainly been wild varieties, however. A shift to large scale commercial poultry production in the early 20th century has helped introduce turkey into the American diet through things like sliced deli turkey. The virtual disappearance of wild turkeys from New England due to deforestation meant that they had to be reintroduced to New England, an effort that began in the 1960s. VanillaVanilla is an orchid native to the Caribbean and south Central America. Cultivated by pre-Columbian Maya people, it was widely adopted by subsequent Indigenous peoples, including the Aztecs, who added it as a flavoring agent to their chocolate beverages. Attempts to cultivate vanilla in Europe were unsuccessful, largely because vanilla is naturally pollinated only by a native species of bee. An boy named Edmond Albius, enslaved on the Island of Reunion, pioneered a hand pollination technique that allowed vanilla to spread across the globe, including to the islands of Tahiti and Madagascar. Wild RiceWild rice, known in Anishinaabe/Ojibwe as "manoomin," is, indeed, a wild rice. Growing in marshy lakes, truely wild rice is harvested by hand from the wild. Wild rice is central to Anishinaabe culture, and one legend indicates that Ojibwe people emigrated from the Atlantic coast to the "place where food grows on the water." Although Northern wild rice is the most common, other two other varieties are native to North America - one in Florida and one in Texas. Suggestions to grow wild rice commercially were suggested as early as the mid-19th century, but it was not attempted on any scale until the 1950s. Commercially cultivated "wild" rice is now a great source of controversy, as is the genetic modification of wild rice. Opponents argue that commercial wild rice conflicts with Indigenous food sovereignty and treaty rights. True wild rice can also be endangered by relaxed water pollution standards, oil pipelines, and more. Indigenous people were rarely if ever involved in the research and are not beneficiaries of commercial varieties. For reasons of taste and to support Indigenous tribes and businesses, I strongly recommend that you source your wild rice from Indigenous producers. ConclusionPhew! That is a LOT of influential foods developed by Indigenous Americans. I hope you learned something with this catalog - I know I did. And I hope you'll support Indigenous food producers by purchasing direct whenever you can. Thanks to the magic of the internet, that's now possible more than ever. And for those of you interested, I'm planning a couple more posts (and a few talks) about the influence of pumpkins, corn, wild rice, and more. So stay tuned! What's your favorite Indigenous American food? The Food Historian blog is supported by patrons on Patreon! If you found this article interesting, useful, and/or thought-provoking, join us for awesome members-only content like free digitized cookbooks from my personal collection, e-newsletter, and even snail mail from time to time!

Thanks to everyone who joined us for Episode 21 of the Food History Happy Hour! We discussed pumpkins and their indigenous origins, as well as the history of pumpkin pie spice, including a discussion of the European spice trade, where various spices come from, and how they went from the purview of the fabulously wealthy to hopelessly old-fashioned, to ragingly popular again. Plus we talk about how pumpkin spice got its name and what's REALLY in those cans of pumpkin puree.

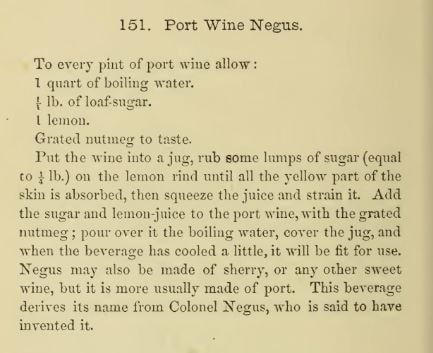

Port Wine Negus (1862)

This particular recipe comes from the famous Jerry Thomas, in his 1862 book, The Bar-Tender's Guide but the drink is actually much older, dating back to the 18th century, and features in the novels of Jane Austen and Charles Dickens. By the Victorian period, it was commonly used for children's parties (shocking I know), and it seems that Jerry Thomas may have lifted his recipe directly from Isabella Beeton.

I followed this recipe pretty closely, and it makes a LOT - I filled my teapot full - so be aware that either you need to save any leftovers for a soda negus (also in Jerry Thomas), share with friends, or cut the recipe down. Here's the original: 151. Port Wine Negus

Here's the version I made:

4 cups water, brought to a boil 2 cups Ruby port 1/2 cup sugar 4 tablespoons bottled lemon juice 4 cloves about 1/4 teaspoon fresh grated nutmeg This makes one and a half quarts of hot Negus, which is delicious but was too sweet for my taste. I'm guessing the original recipe called for Tawny port, which is not as sweet as Ruby port. I also cheated and used bottled lemon juice instead and added cloves because another recipe for soda negus I saw called for them. It really is imperative to use fresh nutmeg for this recipe, as the ground kind doesn't hold a candle in flavor. One or two nutmegs will last you a long time, so you don't have to buy a ton. It is fairly addictive, so just be forewarned. I may or may not have had four cups in the course of Food History Happy Hour and writing this blog... Episode Links:

I had fun researching this topic and even learned a few things! One of my primary sources for the European spice trade as the book Nathaniel's Nutmeg, by Giles Milton. It's a highly engaging read and designed for a more popular audience, so if anyone wants to read about bloodthirsty Europeans obsessed with spice and their various maritime misfortunes, check it out.

other fun links include:

The next Food History Happy Hour won't be until Friday, October 30, 2020, but we'll be discussing Halloween! And making the Stone Fence cocktail. I hope you'll join us then. AND! I have a special treat for Patreon members old and new - join or renew at the $5 level and above, and you'll get a special Halloween packet mailed to you! Chock full of all kinds of fun history, images, party ideas, recipes, and more.

If you enjoyed this episode of Food History Happy Hour and would like to support more livestreams, please consider joining us on Patreon. Patrons get special perks like access to members-only content.

Thanks to everyone who participated in this week's Food History Happy Hour! In this episode we made the Flash of Lightning from the Recipes of American and Other Iced Drinks, London (1902).

For this episode we discussed the recent controversy from Goya CEO and the context and history behind Spanish culture and colonialism in South and Central America, the history of root beer and other early sodas, including ginger ale, birch beer, and sarsaparilla, the origin of root beer floats and ice cream sodas. Flash of Lightning Cocktail (1902)

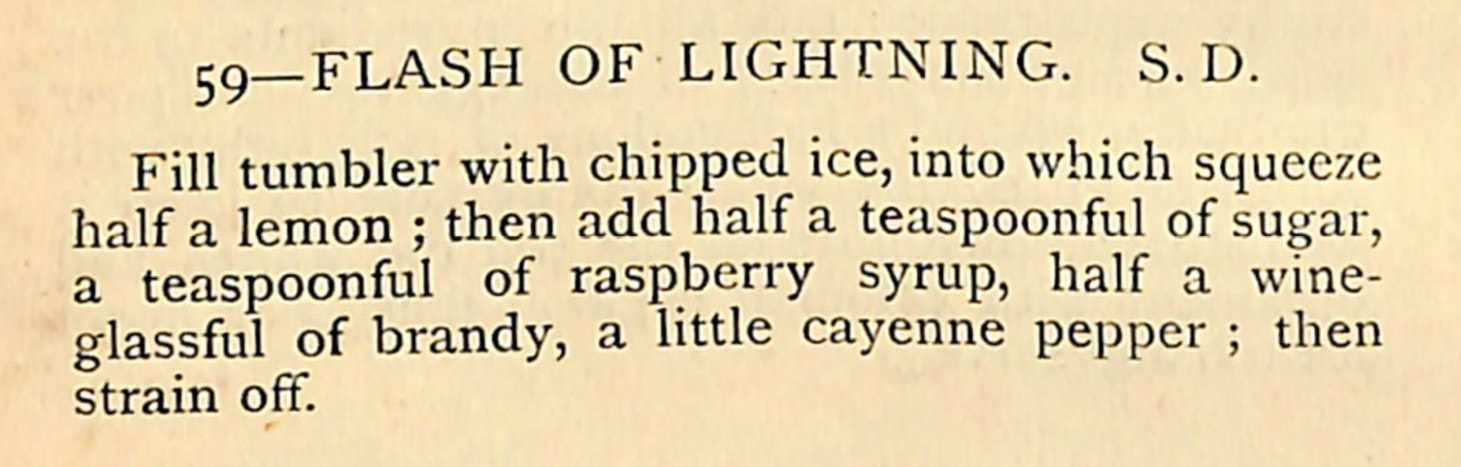

Here's the original recipe, from Recipes for American and Other Iced Drinks by Charlie Paul (1902):

Fill tumbler with chipped ice, into which squeeze half a lemon; then add half a teaspoonful of sugar, a teaspoonful of raspberry syrup, half a wine-glassful of brandy, a little cayenne pepper; then strain off. And here's my version: In a cocktail shaker over ice, add: Juice of half a lemon 1/2 teaspoon granulated sugar 1 teaspoon (or thereabouts) raspberry syrup 2 ounces cherry bounce one or two taps of ground cayenne pepper Shake then strain into wineglass. This recipe is definitely a quite sweet (thanks in part to the cherry bounce), so if you want something not so sweet, leave off the sugar. As the drink warms and sits the heat of the cayenne will intensify, so you might want to use a light hand to begin with. Episode Links

If you liked this post and would like to support more Food History Happy Hour livestreams, please consider joining us on Patreon. Patrons get special perks like access to members-only content.

|

AuthorSarah Wassberg Johnson has an MA in Public History from the University at Albany and studies early 20th century food history. Archives

July 2024

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed