|

I used to hate gin and tonics. "Bitter, bitter pine trees" I called it (incidentally, somebody please make that their band name). But while plain dry gin and regular tonic are still not my thing, I've become a much bigger fan of gin than I originally thought. In particular, flavored gins, which are so easy to make at home! Rhubarb is a favorite in Northern Europe and Scandinavia is no exception. But ultimately rhubarb reminds me of growing up in North Dakota! Also known as "pie plant," the only safe part of the rhubarb plant for humans to eat is the stalk. It gets its sourness from oxalic acid, which is concentrated in the leaves, making them inedible and toxic. But its tartness is part of its charm, as rhubarb is often one of the earliest "fruits" available after winter. Although rhubarb is done for the season in much of the United States by July, I was able to rescue some stalks from my mother-in-law's house before they got too dry. June was a busy month for me, so I didn't have much time to turn them into desserts. Gin it was! Rhubarb Gin & TonicThis recipe is pretty straightforward, and makes the most delicious, rhubarb-y gin! 10-16 rhubarb stalks sugar to coat dry gin tonic water Cut the rhubarb lengthwise into long strips, then cut crosswise into small pieces. Essentially, you want it minced. Add it to a quart jar (about 3 cups) and add sugar to coat, a 1/4 to a half cup. Seal and shake vigorously and let rest at room temperature, shaking occasionally, until the rhubarb gives up its juice. After 12-24 hours, cover with dry gin (I used the tail end of a bottle of Beefeater). Shake well and let rest at room temperature, shaking occasionally, for a day or two before using. The pinker your rhubarb, the pinker the gin. Eventually, the minced rhubarb will lose its color, but it will still taste delicious. To make the beautiful pink gin into a tonic, pour a finger or two over ice, fill with tonic water, and stir to chill and combine. You don't have to use particularly high-quality gin - the sugar smooths out a lot of the alcoholic burn. But try to use a higher quality tonic than the garden variety. I like Fever Tree. Use the plain tonic for full rhubarb flavor. But if you're feeling extra fancy and adventurous, try it with their Elderflower tonic! The flavor of the rhubarb and the elderflower merge to give almost a grapefruit-y taste. I like both ways! Purchases from affiliate links will give The Food Historian a small commission. Infusing alcohol is one of my favorite ways to "preserve" fruit, and gin is one of the most forgiving. You can make blackberry gin, raspberry gin, and even celery gin! Just add fruit, a little sugar if you want, and let it rest until the gin takes on the color and flavor of whatever you're putting in it. This is the last post in my Scandinavian Midsummer Porch Party series. I hope you enjoyed it! Follow the link to see the whole menu. The Food Historian blog is supported by patrons on Patreon! Patrons help keep blog posts like this one free and available to the public. Join us for awesome members-only content like free digitized cookbooks from my personal collection, e-newsletter, and even snail mail from time to time! Don't like Patreon? Leave a tip!

0 Comments

Halloween is tomorrow and that quintessentially American holiday is feeling a little less festive this year. Although I did have a very small party last weekend, and I certainly decked the halls with lights, decorations, and lovely Halloweenish dishware like tiny ceramic cauldron bowls, a big ceramic cauldron for punch, and a big white pumpkin soup tureen for sweet potato-tomato soup, the gloss of my favorite holiday had worn a little thin. A year and a half of pandemic without much of a break will do that to a girl! That being said, nothing makes you feel better than a perfect recipe, and this is one of the more perfect ones I've invented. Inspired by a cocktail I made for my wedding (the "Fallen Apple"), this sweet little cocktail is easy to keep as a mocktail, or for grownups to spike. Perfect Halloween CocktailThis recipe can be made individually or as a punch. For the party I made a big cauldron of punch and let people spike as they wanted (or not). It feels VERY vintage and turns a lovely reddish shade thanks to the cranberry juice. A nice accompaniment to the casual Halloween party menu I put together (see below). 1 part sweet apple cider 1 part cranberry juice cocktail 1 part ginger ale 1/4 part alcohol (I like Winter Jack best, but other party-goers used apple pie spiced moonshine, spiced rum, bourbon, and applejack) This basic recipe can be used to make punch (use a quart each of the non-alcoholic stuff and add 1 cup alcohol). If you're doing individual servings, it's about a third of a cup of each of the juices and ginger ale with 1 ounce of alcohol. The drink is very sweet, so if you want to tone down the sugar, try substituting hard apple cider for the sweet cider, unsweetened cranberry juice for the cocktail, and/or a punchier ginger beer for the ginger ale. Casual Halloween Party MenuSadly I did not get any photos of the food from last week's Halloween party! But I thought I would share the menu with you. I've found one of the nicest ways to have a Halloween party that doesn't break the bank or mean hours of work is to select your treats by color instead of fussy things that look like decapitated body parts or ghosties and ghoulies. This is a hallmark of early 20th century parties, too. White, orange, and dark purple/black are usually lovely classic colors. A little green isn't remiss, either. Here's my simple menu from last week's party: Veggies & dip orange peppers, baby carrots, kohlrabi, cucumber, broccoli with ranch dip Fresh fruit red and yellow pears, russet apples, fresh figs, black grapes Cheese & meat tray with crackers sharp white cheddar, blue & cream cheese spread, pimento cheese, smoked mozzarella, BLACK specialty cheese flavored with lemon, sliced pepperoni and salami, Wasa rye crackers, long multigrain crackers, Raincoast raisin and rosemary crisps Mixed nuts in the shell with nutcracker Dark Autumn Salad dark red leaf lettuce, dried cranberries, butter-toasted pecans, homemade balsamic vinaigrette, crumbled feta Cocktail sausages in barbecue sauce Vegan Smoky Sweet Potato Tomato Soup onion, sweet potatoes, tomato paste, tomatoes, smoked paprika, pureed New York Gingerbread with blackberry maple jam and whipped cream The other surprise hits of the evening were the salad (I heated frozen pecans in a little butter in a saucepan - so good!), the cocktail, and my friend Jess' amazing homemade blackberry maple jam with the gingerbread. Sadly we ate almost the whole jar, but I've got six other flavors from her to savor. The seven people who attended had a great time grazing all the yummy things for the SEVEN HOURS we hung out. Lol. Party started at 4 pm and the last guests left at 11 pm. It was nice having a smaller party because I made less food, we were actually able to use real dishes, and we had some great conversations. If you're more ambitious than I was this season, you can always check out my 2019 vintage party, or download last year's Halloween History Packet. 2020 Halloween History Packet

$5.00

This full-color, 16 page PDF packet discusses all things food history and Halloween, including a basic overview of Halloween history, how Halloween has been celebrated in the United States over the decades, vintage and modern recipes, party suggestions, and a bibliography with links to historic digitized Halloween content. Included inside:

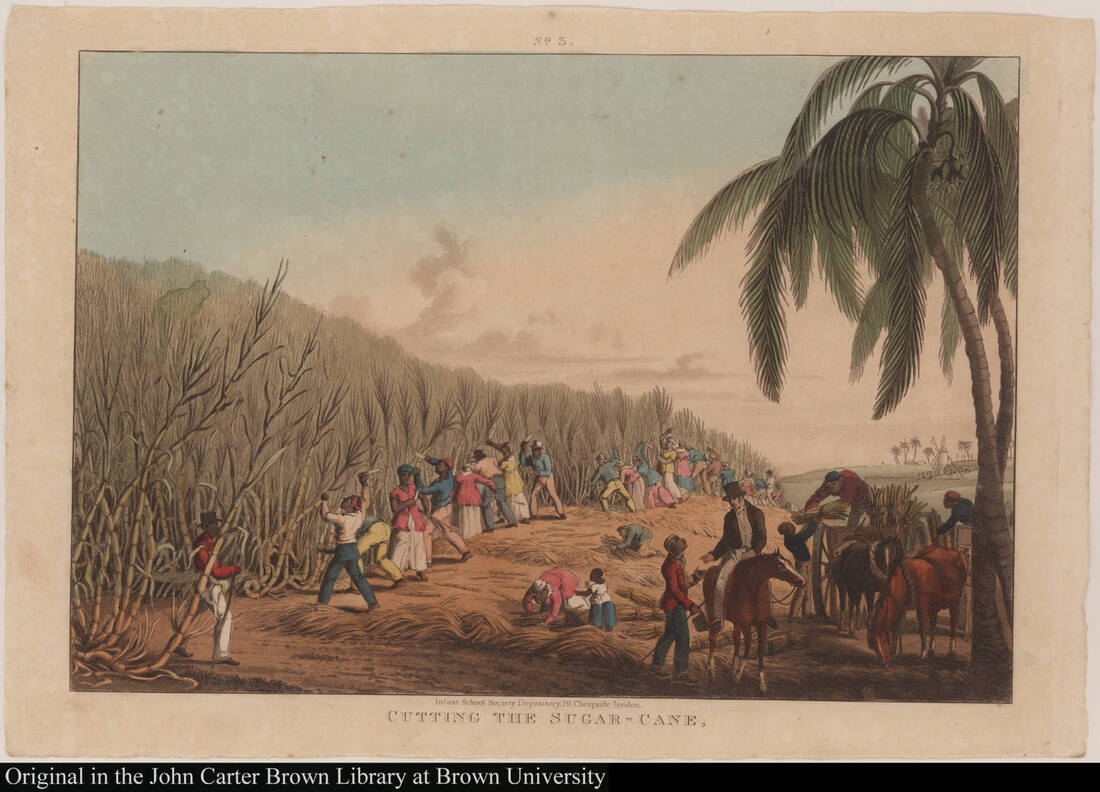

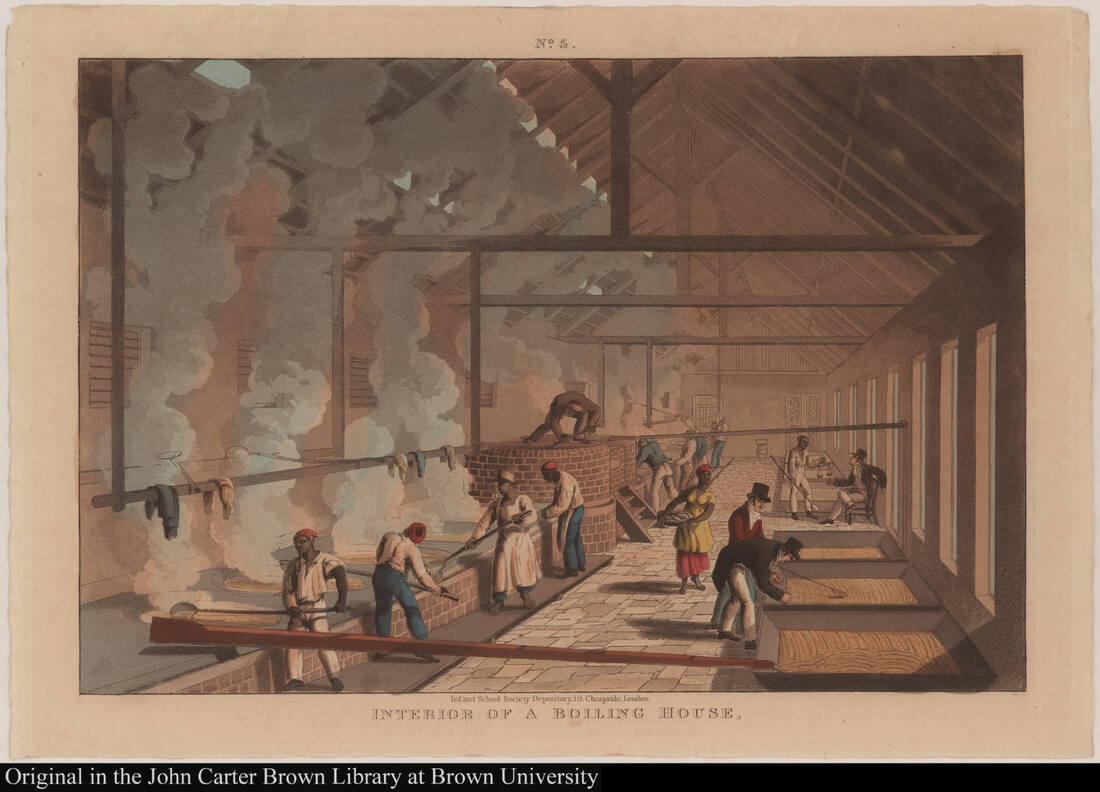

This is a digital download. Once you purchase this item, you will receive an email with the digital file. We are getting a little festive on Sunday night, going "trick or treating" in costume to a friend's very well-decorated house. What are your Halloween plans? Whether you're celebrating solo or with family or friends, I hope you have a lovely Halloween! The Food Historian blog is supported by patrons on Patreon! Patrons help keep blog posts like this one free and available to the public. Join us for awesome members-only content like free digitized cookbooks from my personal collection, e-newsletter, and even snail mail from time to time. Don't like Patreon? Join with an annual membership below, or just leave a tip! The United States owes enslaved people and their descendants a lot. White Americans don't like to admit that often, but we really do. And to me, nowhere is that more evident than in our modern food system. Today is Juneteenth - a celebration of the end of slavery in the United States. Not on the anniversary of the Emancipation Proclamation, which was issued on January 1, 1863 and which LEGALLY freed all enslaved people in the country. No, it took until June 19, 1865 - fully two and a half years later, for the message (and the enforcement) to finally arrive in Texas with a group of Union soldiers. For although all enslaved people in the United States were deemed free in 1863, the Confederacy did not recognize that authority, and continued to enslave and exploit Black people until forced to do otherwise by armed Federal troops. So to celebrate Juneteenth, you can certainly look up recipes and plan a party. But I think it's equally important to recognize incredible contributions enslaved people made to our food system, and for Americans of all backgrounds to reckon with the truth that much of our modern foods are the direct result of violence and exploitation. At last night's Food History Happy Hour, viewer Cathy brought up that we learn a lot in school about the contributions of White immigrants, but not so much about the contributions of enslaved people. And that struck me as both very true and very sad. Because so much of what is considered American food is intimately connected to both West Africa and the enslaved people brought here against their wills. People who experienced incredible hardship still had the perseverance and fortitude not only to hold on to their foodways on the horrific voyage across the Atlantic, but to persist in keeping those foodways in the United States. Not all of the foods listed below came from West Africa, but all are a direct result of the enslavement of West Africans. Editor's note: The Food Historian is an Amazon affiliate. Any purchases you make through the book links below will help support blog posts like this! SugarWe can start with the biggest one. Before the enslavement of Africans in the Caribbean and American South, sugar was produced in India at great expense. By kidnapping people and forcing them into bondage, enormous sugar plantations were established by Europeans throughout the Caribbean, and later in American states like Louisiana. Sugar plantations were some of the most brutal of the plantation economy. The life expectancy of an enslaved person was very low, and some islands imported double or triple their populations per year in slaves, as many died faster than they could be replaced. Today, sugar is almost completely mechanized, but most of our modern foodways - sugary desserts in particular - are possible only through the massive effort to enslave millions of people for profit. Throughout the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, sugar became increasingly affordable, as sugar production mechanized. The cultivation of sugarcane remained incredibly labor-intensive. Sugarcane harvesting, for example, was not really mechanized in the American South until World War II. As an aside, I recently learned that the United States was active in the slave trade for decades after it was made illegal, and that the primary point of destination for American slave traders after kidnapping mostly children from West Africa was the sugar plantations of Cuba. This illegal trade continued until the 1860s. Further Reading:

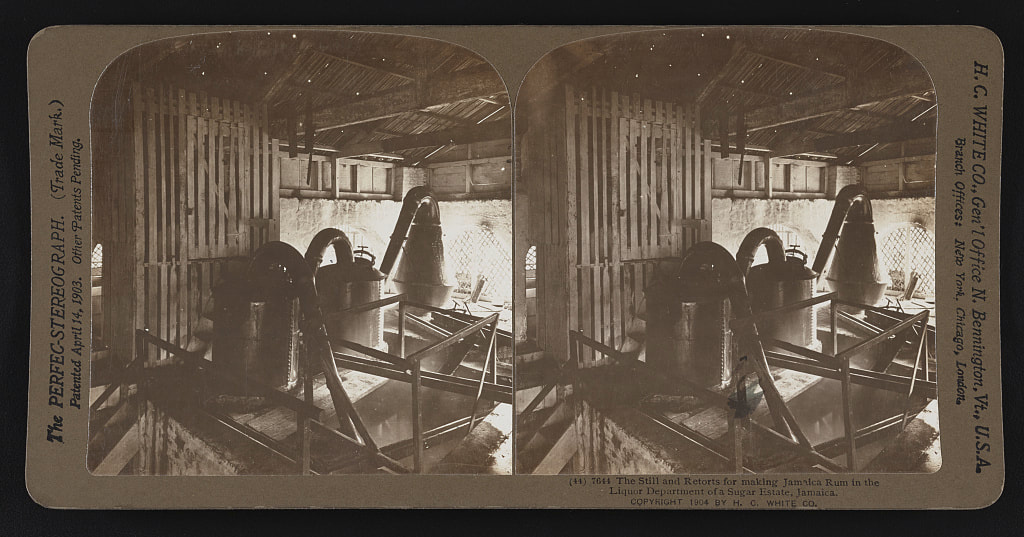

MolassesMolasses may make you think of baked beans, or gingerbread, or soft molasses cookies. But molasses is a byproduct of the sugar industry, and therefore slavery. Molasses, the cheapest sweetener, also was used in slave rations and was a major foodstuff among poor Whites throughout the United States until the mid-20th century. But although Molasses becomes intimately connected with New England and pioneer foodways, it has another important use... RumRum may make you think of pirates, but it was actually developed as a way to transform relatively worthless molasses into a high-value commodity. And while vicious pirates guzzled it by the gallon, it was also a huge economic engine not only in the Caribbean, but also in New England, where it was produced and used to purchase people and goods in West Africa as part of the slave trade. The irony being that a product largely produced by slaves (first in producing the molasses, and then often again in producing rum) was being used to purchase more slaves should not be lost on anyone. Further Reading:

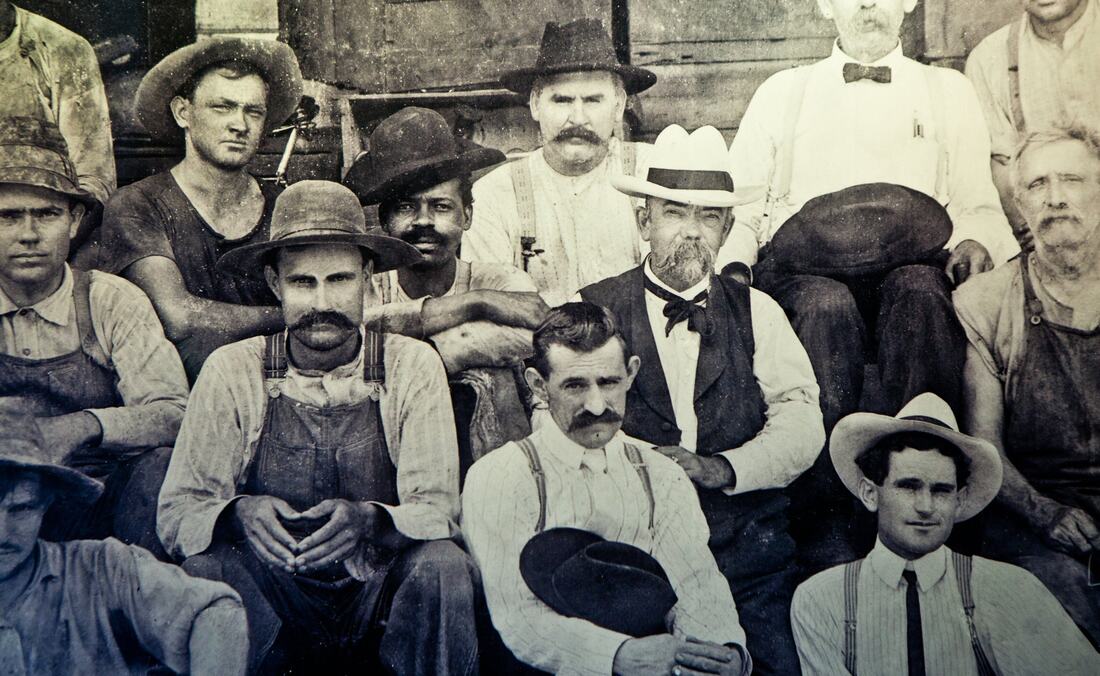

Jack Daniels WhiskyWhile we're on the topic of alcohol and slavery, let's just take a moment to recognize that Jack Daniels was taught how to make whisky by Nathan "Nearest" Green, an enslaved man who used a charcoal filtering technique he learned to clean water in West Africa to filter the distilled alcohol. He was Jack Daniel's first master distiller, but only got credit more recently. Read the full story. RiceI know what you're thinking - Sarah, how are you going to relate RICE to slavery? Well, although today we consume a lot of rice developed in India and Japan, throughout the 19th century, Carolina Gold rice was king. Rice production in South Carolina dates back to the 18th century and plantation owners specifically sought out and captured West Africans skilled in rice agriculture and enslaved them to operate their rice plantations. The White plantation owners got obscenely rich on this scheme. Although Carolina Gold rice is no longer as prevalent in American food culture, it still made a huge impact on the economy of the South. Further Reading:

OkraNative to Ethiopia and cultivated in Africa as early as 12,000 years ago, okra was brought to North America by enslaved West Africans, the seeds braided in their hair. It went on to spread throughout the American South, influencing such dishes as regional varieties of gumbo and often served stewed with tomatoes or breaded and fried. Although not as widespread as some of the other foods on this list, okra still maintains a huge impact on American foodways. Further Reading:

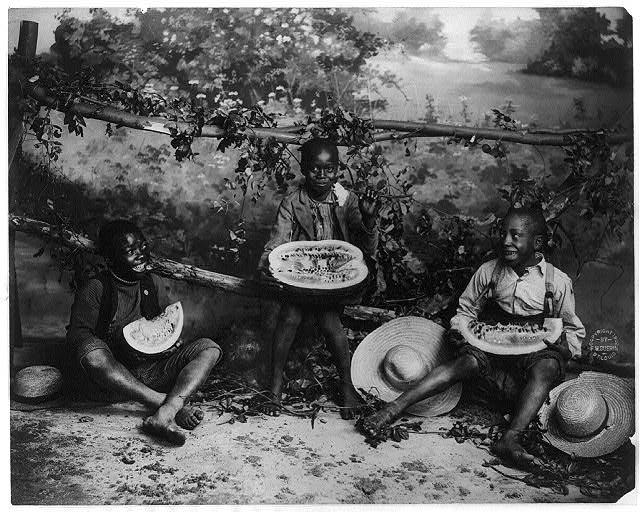

WatermelonDeveloped in the Kalahari desert of Africa, the watermelon was carefully bred by Indigenous Africans to go from a thick-rinded, rather tasteless melon to the sweet, juicy treat we know today. Although it did spread to Egypt and the Middle East, it was likely introduced to North America via the slave trade - either purchased by slave traders and kidnappers, or brought over by enslaved people themselves. The American stereotype of associating Black folks with watermelon as an insult is still around today. Further Reading:

Black Eyed PeasNative to West Africa, black eyed peas, sometimes called cowpeas, were brought to the Americas by enslaved Africans. In the U.S. they are most commonly known as the main ingredient in "Hoppin' John," a popular dish consumed on New Year's Day for good luck. Two stories about black eyed peas and luck have emerged over the years. The first is that when General Sherman made his way through Georgia, one of the only foods the Union Army did not take was black eyed peas, as they were considered cattle fodder in the North. The Confederate Army subsisted on this "slave food," an irony they clearly did not understand. The other story, and one I think far more likely, is that black eyed peas were one of the celebratory dishes consumed on January 1, 1863 - the day the Emancipation Proclamation became law. Further Reading:

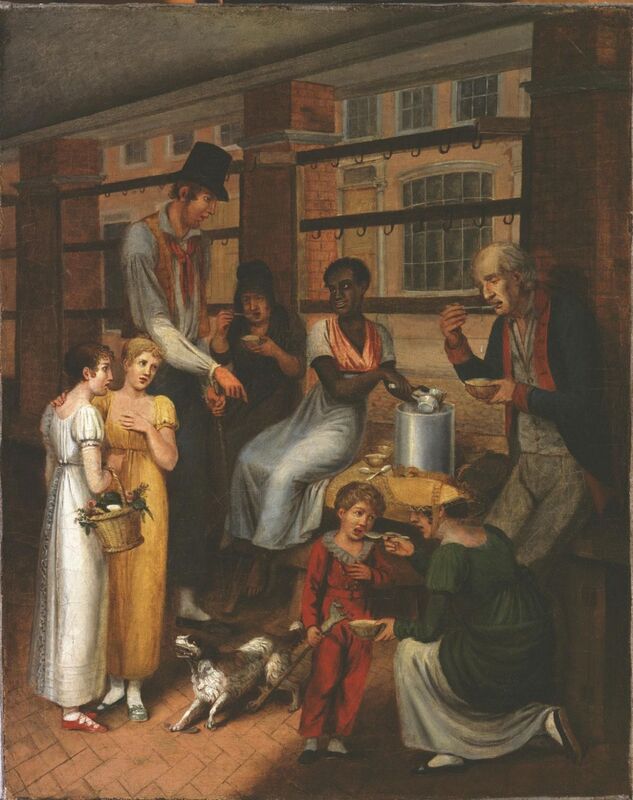

Philadelphia Pepper Pot SoupAccording to Tonya Hopkins, The Food Griot, Philadelphia Pepper Pot Soup, a favorite dish of George Washington, is quintessentially West African in style, including the addition of a whole hot pepper to flavor the soup. It was popularized as a street food in Philadelphia by Black women like the one pictured here. In the 20th century it was commercialized for a brief time by Campbell's, but its popularity waned by the late 20th century. Today, some chefs are reviving the food tradition. Further Listening:

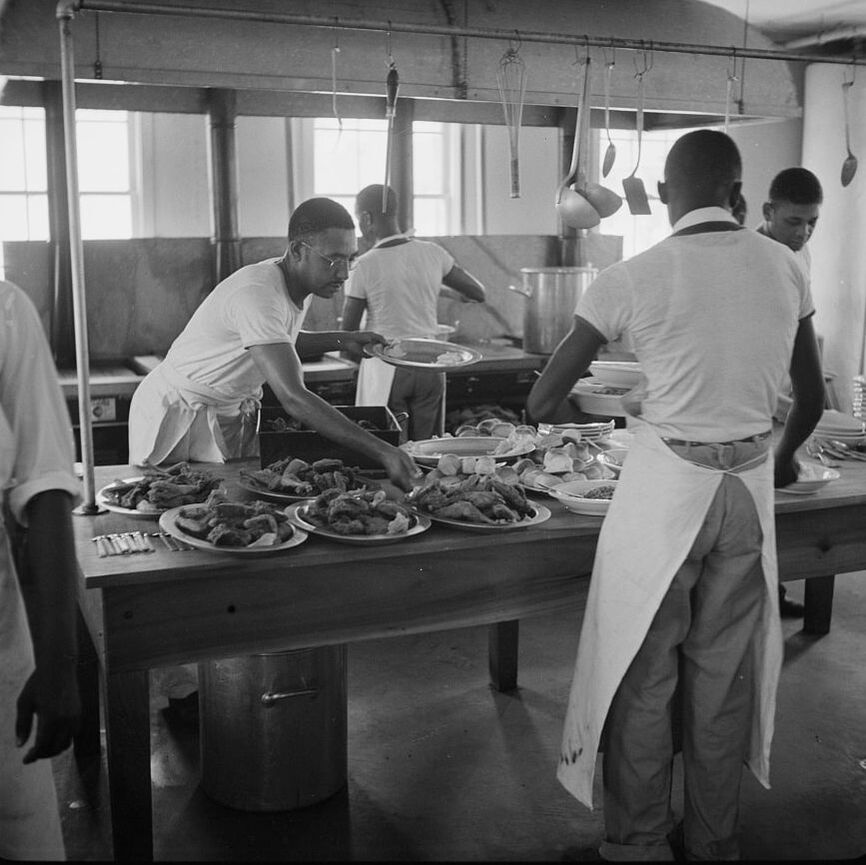

Fried ChickenAlthough who really brought fried chicken to the Americas is disputed (did it come from Africa, Scotland, or some confluence of the two?), by the late 18th century fried chicken is indisputably tied to the South and enslaved cooks. A special-occasion dish that, following the American Civil War, became a real source of income for freed people and their descendants, fried chicken became emblematic of soul food in the 20th century. Further Reading:

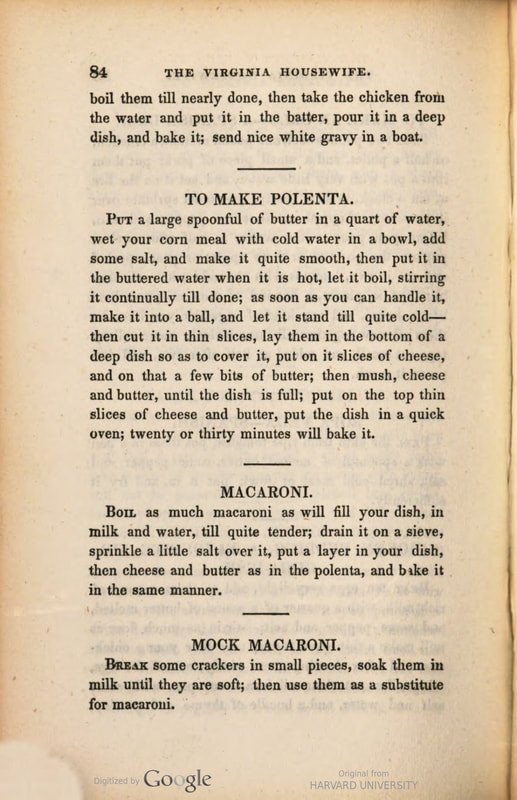

Macaroni and CheeseIs there a more quintessentially American food than macaroni and cheese? It has surprising origins, but was popularized early in American history thanks largely to an enslaved man - James Hemings, Thomas Jefferson's enslaved chef de cuisine. Its popularity among Black Americans is almost certainly due to the long history of macaroni and cheese in Southern (and mostly black-staffed) kitchens. Its use in railroad dining cars staffed by Black cooks also helps popularize it with Americans of all backgrounds. Further Reading:

Obviously, this is not a complete list, but I hope you learned a little something new with this post. As we all celebrate Juneteenth, let's not forget to keep recognizing the contributions of enslaved people and their descendants in contributing significantly to American food and culture throughout our nation's history. Want to learn more? Check out last year's "Black Food Historians You Should Know" for even more further reading. The Food Historian blog is supported by patrons on Patreon! Patrons help keep blog posts like this one free and available to the public. Join us for awesome members-only content like free digitized cookbooks from my personal collection, e-newsletter, and even snail mail from time to time! Don't like Patreon? Join with an annual membership below, or just leave a tip! Join on Patreon or with an annual membership by June 30, 2020 and get a picnic history packet mailed to your door!

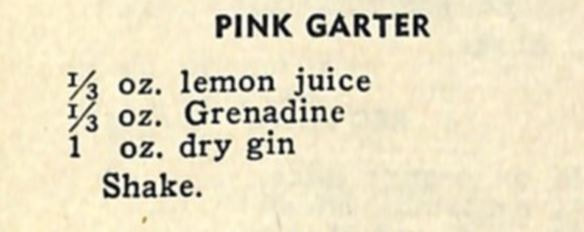

Our 30th episode! Hard to believe we started in March, 2019 at episode 1! In this episode of Food History Happy Hour, we made the Pink Garter cocktail from 1946 and discussed all things wedding food! We started off with WWII rationing and wedding cakes, moved into 19th century wedding breakfasts, why they were called "breakfasts," and the types of food served, including the Medieval origins of wedding cakes, which were originally (and sometimes still are) fruitcake! Then we moved onto trends in cake design, the influence of Queen Victoria on fashionable weddings, and launched into a discussion of famous literary weddings (including Laura Ingalls Wilder and Meg March from Little Women) which then devolved into an (attempted) discussion of what was served at Miss Havisham's wedding breakfast.

In earnest pursuit of Anna Katherine's request to know what was at Miss Havisham's wedding breakfast, I could find no official reference. The original text only refers to the bride's cake and an epergne filled with something cobwebby and rotting. Almost certainly fruit if, like Elizabeth theorized, Miss Havisham's wedding had taken place in the 1810s.

I did, however, find an etiquette book from 1834 that had this to say about weddings: "The breakfast should be supplied by a first rate confectioner and the table should be as beautiful as flowers plate glass and china can make it. The ordinary menu of a wedding breakfast is as follows. Tea, coffee, wines, cold game and poultry, lobster salads, chicken and fish à la Mayonnaise, hams, tongues, potted meats, game pies, savory jellies, Italian creams, ices, and cold sweets of every description." So lots of meat, seafood, and sweets, all served cold. I can only imagine what rotting lobster or fish smelled like in Miss Havisham's house. Yuck. And while I wasn't able to find an actual menu from Queen Victoria and Prince Albert's wedding, I did find a clip from the show Anna Katherine was referring to! The Pink Garter (1946)

Tonight's cocktail came from perennial favorite The Roving Bartender by Bill Kelly, published in 1946. This was a very straightforward, very delicious drink. Super simple, but surprisingly complex-tasting. If you like raspberry lemonade, this drink will be right up your alley. If sweet drinks are not your thing, cut down on the grenadine, or up the gin ratio. It calls for:

1/3 ounce lemon juice 1/3 ounce grenadine 1 ounce dry gin Shake with ice and strain into a martini glass. I garnished mine with a maraschino cherry for extra pizazz. Still looking for more wedding food history? You can watch my illustrated talk as recorded recently for a library lecture!

That's all for this month's Food History Happy Hour! I've got a TON of talks coming up in June, so be sure to check out the events calendar, and we'll see you at the next Food History Happy Hour on June 18th!

The Food Historian blog is supported by patrons on Patreon! Patrons help keep blog posts like this one free and available to the public. Join us for awesome members-only content like free digitized cookbooks from my personal collection, e-newsletter, and even snail mail from time to time! Join by June 30, 2020 and get a picnic history packet mailed to your door!

Don't want to join Patreon? Use our new Tip Jar instead! You can make a one-time donation any time, not strings attached.

Thanks to everyone who joined me for Food History Happy Hour tonight! We talked about the history of diets, dieting, and diet culture, with forays into 19th century religious diets (including Sylvester Graham, Ellen H. White, and John Harvey Kellogg), raw food diets, veganism, changes in fashion influencing ideas about body types, the role of the Gilded Age and Progressive Era and WWI in informing modern ideas about dieting, willpower, and health, the invention of the calorie, the development of dieting and diet fads in the 1930s and '40s, including juicing and the Hollywood diet, we talked about Dr. Norman W. Walker, Gaylord Hauser, Dr. Weston Price, Adele Davis, the role of animal fats in heart disease research, the history of artificial sweeteners, environmental factors in fatness and obesity, and that diet culture is super toxic! I probably could have talked for another hour on this subject, so we can revisit it, if you want to! Let me know in the comments.

We also made a (red) wine spritzer (I thought it was a bottle of white wine, it wasn't) and the history of wine spritzers. Wine Spritzer (19th century)

White wine spritzers are the classically low-calorie bar favorite in the late 20th century United States, but they date back to the early 19th century and are likely associated with the health and spa culture surrounding sparkling mineral waters, but may have also been simply an attempt to make an artificially sparkling wine!

Take your favorite wine - red or white - chilled, and cold club soda or seltzer or sparkling mineral water, also chilled. You can combine them in any ratio, but I think half and half is probably best. Further Reading:

Obviously, I had a blast doing this episode and I think I need to now do some biography blog posts about fad diets and nutritionism and their proponents. Did you know Gaylord Hauser had a TV show? You can alsowatch an interview with Adelle Davis!

The Food Historian blog is supported by patrons on Patreon! Patrons help keep blog posts like this one free and available to the public. Join us for awesome members-only content like free digitized cookbooks from my personal collection, e-newsletter, and even snail mail from time to time!

Some of you may have looked askance at the last episode of Food History Happy Hour where I made (or rather, botched) the 1902 Irish Cocktail. In my defense, it has been a long and rather sleep-deprived spring, and so I let my determination to do the cocktail outweigh my lack of alcohol knowledge, to rather disastrous results. The lesson? You can probably substitute one ingredient in a cocktail, but two or three is a bridge too far. However, Food Historian friend (and Patreon patron!) Anna Katherine is actually an oenologist (that is, a wine scientist) and knows a great deal more about alcohol than I do. She clearly also has a much better stocked liquor cabinet. So she revisited the original recipe much more faithfully, and found the results much better. Here's what she has to say: [A]s a general rule I don't criticize another scholar's work, but after that...er... creation you produced Friday I had Questions. (And a healthy dose of Professional Curiosity.) So- substituting only Pernod for Absinthe, I made the Irish Cocktail. I agree with your estimation of 2oz for a small wine glass, and a dash is a scant 1/4th tsp. I also shook instead of pouring over shaved ice, because I didn't have any- but I compensated by shaking a bit longer than usual to get some melt into the drink, as would happen as you sipped something over shaved ice. The result was perfectly pleasant- a bit boozy, yes, but the dashes of Pernod, curaçao and maraschino added a touch of sweetness that brought out the vanilla notes in the curacao and whiskey, and added some subtle, complex spice around the edges of an otherwise straightforward drink. The lemon peel brought pulled the balance back in so it was focused instead of fat and sweet. Whiskey (made from malt and aged in old barrels) is more subtle and less oaky than bourbon (made from corn and aged in new barrels), so I suspect I had a softer, more integrated, and more balanced tipple than your alcoholic anise Shirley Temple. (I forgot the olive. Dammit.) I never shirk from constructive criticism! Although it must be noted that Anna Katherine did technically substitute Cointreau for curaçao, even though some argue that Cointreau is just a version of curaçao, it is not generally labeled as such in liquor stores, so poor novices like me can't be blamed for buying the blue stuff, okay? ;) Thankfully, we both agreed that the addition of an olive (the original recipe does not indicate ripe, Spanish, or pimento-stuffed) was a strange addition, anyway. You can check the original post for the historic recipe, but Anna Katherine followed it pretty faithfully, except for the substitution of Pernod for the absinthe, which is much-maligned in history, as this excellent article outlines, but which is now "legal" again in the United States, although difficult to find on liquor store shelves. Absinthe, of course, is chartreuse in color, but the recipe contains so little of it one wonders if it would have affected the color of the cocktail at all. Certainly the curaçao would not have been blue at that time, as the best guesses are it was tinted blue starting in the 1920s. Many thanks again to Anna Katherine for taking on the task of trying a more accurate version of the recipe and reporting back the results! Is your liquor cabinet well-stocked enough to try the Irish Cocktail? Do you think the olive would add anything? Let us know in the comments! The Food Historian blog is supported by patrons on Patreon! Patrons help keep blog posts like this one free and available to the public. Join us for awesome members-only content like free digitized cookbooks from my personal collection, e-newsletter, and even snail mail from time to time!

Thanks to everyone who joined me for Food History Happy Hour this month. We talked about all things Irish and food, including the origins of corned beef, Irish soda bread, the Irish Potato Famine, Irish slavery and prejudice, cabbage, brussels sprouts, and the role of brassicas in European and Asian cuisine, and we touched on carageenan or Irish moss pudding, scones and bannocks, Irish coffee, and Irish desserts.

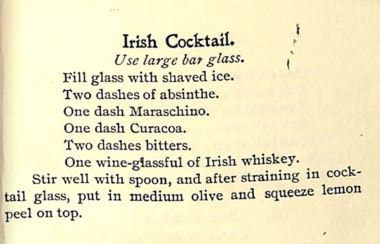

Irish Cocktail (1902)

Tonight's cocktail came from Fox's Bartender's Guide by Richard K. Fox (1902). The 1902 edition was preceded by The Police Gazette Bartender's Guide, first published in 1888, and with a much more interesting cover. Richard K. Fox was the Irish immigrant publisher of The Police Gazette, widely considered the one of the first men's magazines, and which covered tabloid-style sensationalist news, manly (and illegal) sports such as boxing and cockfighting, coverage of vaudeville shows, and "girlie" images of burlesque dancers and other ladies of ill repute.

The cocktail itself is called "Irish" because of the use of Irish whiskey, which also features in several other cocktail recipes. Fox (or whomever was authoring the recipes) seemed rather fond of both absinthe and especially curacao, which feature prominently in most of the cocktail recipes. I won't replicate my version of this recipe as I made a number of substitutes (some knowingly, some out of ignorance) and the end result was not to my taste. Perhaps your version will be better!

Irish Cocktail.

Use large bar glass. Fill glass with shaved ice. Two dashes of absinthe. (or anisette) One dash Maraschino. (the liqueur, not the cherries) One dash Curacoa. (he means Curacao) Two dashes bitters. One wine-glassful of Irish whiskey. (probably 2 ounces) Stir well with spoon, and after straining in cocktail glass, put in medium olive and squeeze lemon peel on top. (a.k.a. a twist of lemon) This cocktail took on a rather unappealing hue, in large part because modern Curacao, an orange-flavored liqueur, is colored bright blue (something that apparently dates to the 1920s). But even historically absinthe was green. Thankfully, Maraschino liqueur is clear. But blue, green, and brown (the whiskey) a muddy-looking cocktail make, so keep that in mind. Episode Sources & Further Reading

The Food Historian blog is supported by patrons on Patreon! Patrons help keep blog posts like this one free and available to the public. Join us for awesome members-only content like free digitized cookbooks from my personal collection, e-newsletter, and even snail mail from time to time!

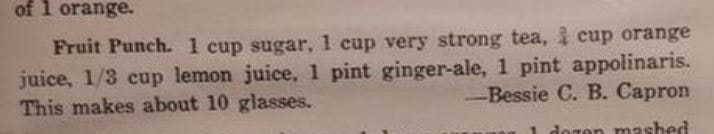

Thanks to everyone who joined us for Food History Happy Hour tonight! We made a version of "Fruit Punch" from 1924, doctored with some spiced rum. We also discussed the history of tea, coffee, and hot chocolate, the use of tea in 18th century punch recipes and in the Temperance movement, the influence of coffee houses on politics and science, the gendering of these drinks, and the difference between high tea, low tea, and afternoon tea.

Old Fashioned Fruit Punch (1924)

We often think of fruit punch today as the bright red sugary concoction of questionable flavor profile. Historically, fruit punches were non-alcoholic alternatives to highly alcoholic party punches popular in the 18th century. This version was probably inspired by Philadelphia Fish House Punch, a heady mix of citrus fruit, rum, brandy, cognac, and black tea. Here's the original recipe:

1 cup sugar 1 cup very strong tea 3/4 cup orange juice 1/3 cup lemon juice 1 pint ginger-ale 1 pint apollinaris (seltzer/club soda) This makes about 10 glasses. Here's the lovely alternative I made 1/2 cup sugar (this was VERY sweet, feel free to cut it to 1/4 cup) 1 cup very strong tea juice of 2 oranges juice of 1 lemon 1 cup ginger ale 1 cup seltzer 1/2 cup spiced rum Stir tea and sugar together over ice, then and the other ingredients and stir to combine. Serve cold in small cups. This is very good and very smooth. You could easily leave out the rum for a more Temperance-friendly non-alcoholic punch, or you can see other alternative punches, along with a history of Temperance, here. Next weekend I'm going to have another tea party, but in the meantime you can review the one from last weekend! So fun.

The Food Historian blog is supported by patrons on Patreon! Patrons help keep blog posts like this one free and available to the public. Join us for awesome members-only content like free digitized cookbooks from my personal collection, e-newsletter, and even snail mail from time to time!

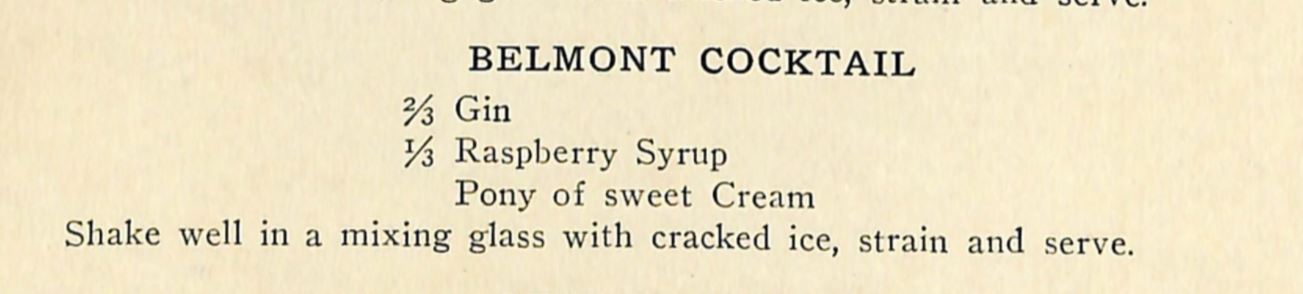

Thanks to everyone who joined us live for Food History Happy Hour! We made the 1917 Belmont Cocktail and chatted about January holidays, including the Russian/Soviet Novy God, Twelfth Night, the Swedish Tjuegondag Knut, Robbie Burn's Day, random National Food Holidays, including National Fig Newton Day (today!), National Peanut Butter Brittle Day (my birthday!), and how on earth all those National whatever days got to be decided. Plus, since my birthday is coming up, we discussed birthday history and birthday cake history, as well as some general cake history.

Belmont Cocktail (1917)

As those of you who have been following Food History Happy Hour for some time know, I often end up making pink drinks accidentally. But this time, in honor of the new year, and my upcoming birthday, I went looking for something that would be specifically pink! And the Belmont Cocktail came to mind. It's featured in Recipes for Mixed Drinks by Hugo R. Ensslin, published in 1917 and one of my favorite cocktail recipe books.

The directions aren't super clear. For instance, 2/3 of WHAT of gin? But I've decided that this is likely a ratio - 2 parts gin to 1 part raspberry syrup, and given that the sweet cream measurement is a pony (1 ounce, usually the other side of a jigger, which is 1.5 ounces), here's what I decided to use. 2 ounces gin 1 ounce raspberry syrup 1 ounce cream Shake with ice, strain, and serve in a pretty cocktail glass. Garnish with a fresh or frozen raspberry if you are so inclined. Sadly, this drink was NOT very good. I've since looked up other recipes, which say to use 2/3 of a GLASS of gin and 1/3 of a GLASS of raspberry syrup, which sounds like way too much. I found that while gin and raspberry probably would have been nice together, and raspberry and cream are definitely delicious, the gin was just too overpowering in this cocktail. It would have been much better as a gin fizz with cream. The addition of club soda or seltzer would have smoothed out the flavors. I think this was probably my least drinkable cocktail ever for Food History Happy Hour! I was so sad, especially since I had such high hopes. SIGH. Must have been my ratios were off, but even other published recipes, it seems like way too much gin and syrup. Oh well. I'll have to track down something more palatable for February! Episode Links

The Food Historian blog is supported by patrons on Patreon! Join us for awesome members-only content like free digitized cookbooks from my personal collection, e-newsletter, and even snail mail from time to time!

On New Year's Eve with broke with tradition a little and did a surprise THURSDAY Food History Happy Hour at 11 PM. Because it was spur of the moment, we didn't really have a specific topic, but we did talk about comparisons between 1920 and 2020, an update about my office/cookbook library, my family New Year's Eve traditions old and new, some of the "lucky" foods of NYE, the Swedish celebrations I grew up with, including Tjuegondag Knut and Sankta Luciasdag, 19th century New Year's menus, what I missed most in 2020, and hopes for 2021.

Vanilla Fig Bourbon Recipe

No historic recipe this time, but the fig bourbon turned out quite nicely! If you want to make your own, here's a nice recipe:

2 cups dried mission figs 1 vanilla bean bourbon to fill a quart jar Put the figs in a quart mason jar. Cut the vanilla bean in half and add to the jar. Fill with enough bourbon to cover the fruit. Let age 3-12 months before consuming. I had some on the rocks with ginger ale. And some of the figs may make their way into a boozy fruitcake at some point. Episode Links

Not too many this time around, but here are a few to whet your whistle:

The next Food History Happy Hour will be on Friday, January 15, 2021 at 8:00 PM EST. We're gonna discuss more in-depth January holidays, including revisiting New Year's, Twelfth Night, Tjuegondag Knut, and my birthday, with a discussion of birthday cake history! See you next time.

The Food Historian blog is supported by patrons on Patreon! Join us for awesome members-only content like free digitized cookbooks from my personal collection, e-newsletter, and even snail mail from time to time!

|

AuthorSarah Wassberg Johnson has an MA in Public History from the University at Albany and studies early 20th century food history. Archives

July 2024

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed