|

This article contains Amazon.com and Bookshop.org affiliate links. If you purchase anything from these links, The Food Historian will receive a small commission. No Useless Mouth: Waging War and Fighting Hunger in the American Revolution, Rachel B. Herrmann. Cornell University Press, 2019. 308 pp., $27.95, paperback, ISBN 978-1501716119. This may be the longest I have ever taken to write a book review. I first received this book and the invitation to review it for the Hudson Valley Review in the fall of 2021. As many of you know, 2022 was a rough year for me, for many reasons, but I finally turned in the review in February of 2023. A few days ago, I received my copy of the Review and now that my book review is in print, I feel I can share it here! This edition of the Review is great, with several excellent articles and other book reviews, so if you manage to find a copy, please check it out! Back issues are often posted digitally. Without further ado, the review: In the historiography of the American Revolution, one can be forgiven for thinking every possible topic has been covered. But Rachel B. Herrmann’s new book No Useless Mouth: Waging War and Fighting Hunger in the American Revolution brings new nuance to the period. In it, Herrmann argues that food played a decisive role in the shifting power dynamics between White Europeans, Indigenous Americans, and enslaved and free Africans and people of African descent. She looks at the American Revolution through an international lens, covering from 1775 in the various colonies through to the dawning of the 19th century in Sierra Leone. The book is divided into eight chapters and three parts. Part I, “Power Rising,” introduces us to the ideas of “food diplomacy,” “victual warfare,” and “victual imperialism” within the context of the American Revolution. Contrasting the roles of the Iroquois Confederacy in the north and the Creeks and Cherokees in the South, Herrmann brings additional support to the idea that U.S. treaties with Indigenous groups should join the pantheon of diplomacy history, while centering food and food diplomacy within the context of those treaties. She also addresses how Indian Affairs agents communicated with various Indigenous groups – with varying success. Part II, “Power in Flux,” addresses the roles of people of African descent in the American Revolution, focusing primarily on Black Loyalists as they gained freedom through Dunmore’s Proclamation and the Philipsburg Proclamation. Black Loyalists fought on behalf of the British as soldiers, spies, and foraging groups, and escaped post-war to Nova Scotia with White Loyalists. Part III, “Power Waning,” summarizes what happened to Indigenous and Black groups post-war, focusing on the nascent U.S. imperialism of Indian policy and assimilation and the role food and agriculture played in attempts to control Native populations. It also argues that Black Loyalists adopted the imperialism of their British compatriots in attempts to control food in Sierra Leone, ultimately losing their power to White colonists. Part III also includes Herrmann’s conclusion chapter. No Useless Mouth is most useful to scholars of the American Revolution, providing good references to food diplomacy while also highlighting under-studied groups like Native Americans and Black Loyalists. However, lay readers may find the text difficult to process. Herrmann often makes references to groups and events with little to no context, assuming her readers are as knowledgeable as she. In addition, the author appears to conflate Indigenous groups with one another, making generalizations about food consumption patterns and agricultural practices without the context of cultural differences. In focusing on the Iroquois Confederacy and the Creeks/Cherokee, Herrmann also ignores other Native groups, despite sometimes using evidence from other Indigenous nations to support her arguments. For instance, when discussing postwar assimilation practices with the Iroquois in the north and the Creeks and Cherokee in the south (often jumping from one to another in quick succession), she cites Hendrick Aupaumut’s advice to Europeans for dealing successfully with Indigenous groups. But she fails to note that Aupaumut was neither Iroquois, Creek, nor Cherokee, but was in fact Stockbridge Mohican. The Stockbridge Mohicans were a group from Stockbridge, Massachusetts that was already Christianized prior to the outbreak of the American Revolution. They fought on the Patriot side of the war, with disastrous consequences to the Stockbridge Munsee population, and ultimately lost their lands to the people they fought to defend. Without knowledge of this nuance, readers would accept the author’s evidence at face-value. Herrmann’s strongest chapters are on the Black Loyalists, and her research into the role of food control in both Nova Scotia and Sierra Leone is groundbreaking, but even those chapters have a few curious omissions. In discussing Lord Dunmore’s Proclamation, which was issued in 1775 in Virginia and targeted enslaved people held in bondage by rebels, freeing those who were willing to join the British Army. The chapter then focuses primarily on the roles of enslaved people from the American South. But Herrmann also mentions briefly the Philipsburg Proclamation, issued in 1779 in Westchester County, NY, which freed all people held in bondage by rebel enslavers who could make it to British lines. That proclamation arguably had a much larger impact on the Black Loyalist population, as it also included women, children, and those above military age, thousands of whom streamed into New York City, the primary point of evacuation to Nova Scotia. And yet, Herrmann does not mention at all enslaved people in New York and New Jersey, where slavery was still very active throughout the American Revolution and well into the 19th century. In the chapter on Nova Scotia, Herrmann also mentions that White Loyalists brought enslaved people with them, still held in bondage. Neither Dunmore’s nor the Philipsburg proclamations freed people held in bondage by Loyalists, and yet they get only a brief mention. Her chapters on Indigenous-European relations are extremely useful for other historians researching the period, but would have been improved with additional context on land use in relation to food. Herrmann often references famine, food diplomacy, and victual warfare in these chapters, without addressing the impact of land grabs and disease on the ability of Indigenous groups to feed themselves. She references, but does not fully address the need of European settlers to expand settlement into Indian Country as a motivating factor in war and postwar diplomacy. Finally, while the focus of the book is specifically on the roles of Indigenous and Black groups in the context of food and warfare, the omission of victual warfare by British and American troops and militias, especially in “foraging” and destroying foodstuffs of White civilian populations throughout the colonies seems like a missed opportunity to compare and contrast with policies and long-term impacts of victual warfare toward Indigenous groups. In all, this book is a worthy addition to the bookshelves of serious scholars of the American Revolution, especially those interested in Indigenous and Black history of this time period, but it also leaves room for future scholars to examine more closely the issues Herrmann raises. No Useless Mouth: Waging War and Fighting Hunger in the American Revolution, Rachel B. Herrmann. Cornell University Press, 2019. 308 pp., $27.95, paperback, ISBN 978-1501716119. The Food Historian blog is supported by patrons on Patreon! Patrons help keep blog posts like this one free and available to the public. Join us for awesome members-only content like free digitized cookbooks from my personal collection, e-newsletter, and even snail mail from time to time! Don't like Patreon? Leave a tip!

0 Comments

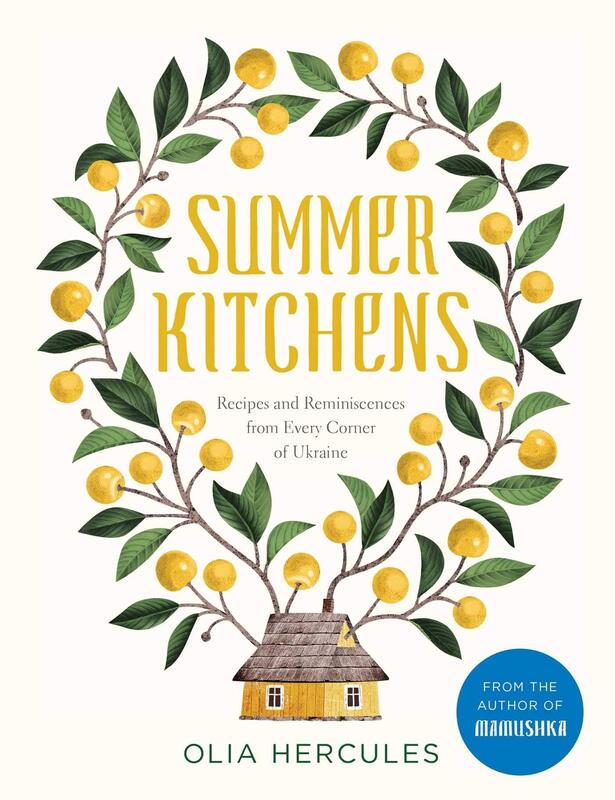

This post contains Amazon affiliate links. Summer Kitchens Recipes and Reminiscences from Every Corner of Ukraine by Olia Hercules had been on my wish list for a while. Released in 2020, it seemed like just exactly the kind of cookbook I would like - interesting recipes linked with interesting stories. When Russia invaded Ukraine in late February, and Olia Hercules became a defacto spokesperson for Ukrainian foodways, I decided to finally purchase it. I'm quite picky about cookbooks, and it takes a lot to impress me. The recipes need to be familiar but surprising, introducing me to new techniques and especially flavor combinations. The headnotes have to be robust, the recipes not too finicky, and the storytelling excellent. Summer Kitchens manages to meet and exceed all of these requirements. It's really quite a stunning little book. Olia is just a year older than me, was born and spent most of her childhood in Ukraine. At age 12 her family moved to Cyprus for her asthma, and as a young adult she moved to London to study, where she lives today. She started her career in film, and it shows through her storytelling. She also worked as a professional chef, including for Ottolenghi's. Summer Kitchens is her third cookbooks. Her first, Mamushka: Recipes from Ukraine and Eastern Europe, was published in 2015, and her second, Kaukasis The Cookbook: The culinary journey through Georgia, Azerbaijan & beyond, was published in 2017. Her fourth cookbook, Home Food: Recipes to Comfort and Connect, is due to be released in December of this year. Although I haven't read her earlier cookbooks, I did have the opportunity to flip through Mamushka in a bookstore the other day, and I have to admit it wasn't as appealing as Summer Kitchens. I think that's in part because Summer Kitchens is all about that indefinable longing for a home you only knew for a little while. Like Olia, and many of the authors of letters she includes in the back of the book, I have memories of rural idylls as a child. Mine were of visiting my great-grandmothers in rural North Dakota in the summer. Of enormous gardens where I learned that peas actually aren't so bad if you eat them fresh and sweet right from the pod. Of old-fashioned flowers, and dirt cellars full of glass jars of preserved food. Of freshly-turned black dirt in the potato patch so soft it was perfect for bare feet to make impressions. Of homemade baked beans (my first ever taste) and fat, nutmeg-scented donuts and homemade pickles and sweet water buns with bright red chokecherry jelly. Of rhubarb custard cakes and the world's best North Dakota red mashed potatoes. Of playing beneath enormous cottonwood trees with their rustling leaves, and searching the quiet gravel roads for agates and quartz and petrified wood. Olia's reminiscences are a little different, but they still resonate. Sunny days in gardens, preserving food for winter, helping grandmas and moms clean fruit and chop vegetables. Memories of delicious homemade foods, special holidays, and especially the pich - the enormous brick and tile stoves that are common in many northeastern European countries, including my ancestral Scandinavia. The cookbook itself is divided seven chapters of recipes, preceded by essays on the summer kitchen and Ukraine's unique food regions. The chapters are:

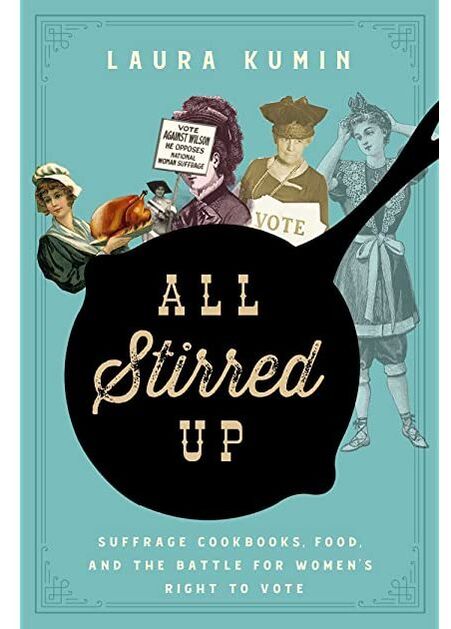

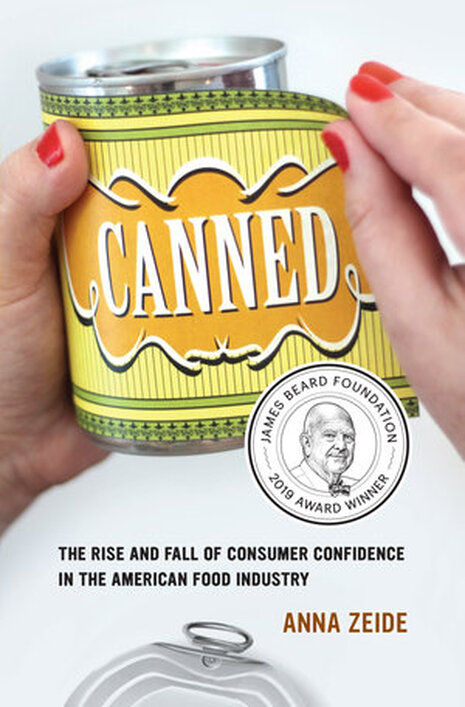

Although the chapter on fermenting will likely make Americans flinch slightly (Summer Kitchens was published in the UK, which apparently does not have as stringent rules about food preservation advice as the U.S.), the recipes sound amazing, and several don't require preservation at all, including the intriguing-sounding smoked pears (and plums). I was interested to see that Hercules included watermelon molasses in the cookbook. Her headnotes indicate that she included it more for posterity than for anyone to use it, but sweet watermelon paste is still used in some areas of North Dakota, where Germans from Russia immigrants left Ukraine for the Northern Plains. Although it is definitely not a vegetarian cookbook, many of the recipes are vegetarian. This reflects in part the background of the people who developed this cuisine - meat was not always abundant, and vegetables often were. But also, as Hercules mentions, her husband is vegetarian, as are many of her friends, and so she cooks vegetarian often. This was incredibly refreshing for me to see. I am not vegetarian, but enjoy vegetarian food and am always looking for new recipes. Some, like cucumbers in sour cream are familiar. Others, like a tomato mulberry salad with red onion and purple basil are stunningly beautiful and sound delicious. Even the meat recipes, which I usually find boring in most cookbooks, are inviting, like the slow-roasted pork with sauerkraut and dried fruit. Fatty pork gets rubbed with spices and then cooked slowly in the oven with sliced onion, sauerkraut (homemade, of course), prunes, dried apricots, apples, and toasted caraway, coriander, and fennel seeds. Olia recommends fending off greedy guests to ensure enough leftovers to stuff into a sweet bun recipe also included in the cookbook. With the exception of pistachio napoleons and poppyseed babka, the dessert recipes are also unfussy and delicious-looking. A caramelized apple ricotta cake, classic potato-dough dumplings stuffed with halved plums and served with honey, steamed bilberry-stuffed donuts rolled in crushed walnuts and sugar. Summer Kitchens is not just about summer cooking. It is about how summer kitchens have been used throughout Ukraine historically, how they continue to be used, and what they represent. It's no accident that Hercules starts her book in September, with preserving season. Because the summer kitchen is also a reflection of the summer garden. Many recipes, especially in the first chapter, reflect an abundance of produce that most of us no longer have access to. Hercules even notes this change in her essays, noting in one how dismayed a young Ukrainian was to find her uncle had dropped a forty pound sack of cucumbers off on her front step. Instead of joy at the opportunity to turn free produce into pickles, the young woman saw only work and the guilt to do something with the cucumbers before they went bad. And therein lies the rub. While Hercules has managed to produce an amazingly atmospheric and even cozy cookbook full of recipes any home cook with a little ambition could produce, it is also a love letter to a way of life many would say is dying. Hercules herself admits that her beloved pich ovens are increasingly being torn out for more modern appliances, and summer kitchens are being converted or torn down. It's easy to romanticize the past, to the frustration of those trying to still live it. But in a day and age when whole generations dream of giving up the rat race and settling in a little rural cottage with a big garden, Olia Hercules' depictions of Ukraine can sound like paradise. And perhaps it is. But in a time when Ukraine is being torn apart by war (again) and threatened with hunger (again), Summer Kitchens reads more like a love letter to what every Ukrainian would love to have, but can never seem to grasp for long. Serfdom, World Wars, collectivism, famine, invasion, Sovietization - all these have threatened but never quite destroyed the Ukrainian garden of Eden. But like most old foodways, Ukrainian food is threatened by modernity. I'm hopeful that books like Summer Kitchens will help keep them alive. The Food Historian blog is supported by patrons on Patreon! Patrons help keep blog posts like this one free and available to the public. Join us for awesome members-only content like free digitized cookbooks from my personal collection, e-newsletter, and even snail mail from time to time! Don't like Patreon? Leave a tip! If you'd like to learn more about Ukraine, food history, and politics, check out my new Substack newsletter - Historical Supper Club. This article contains Amazon.com and Bookshop.org affiliate links. If you purchase anything from these links, The Food Historian will receive a small commission. All Stirred Up: Suffrage Cookbooks, Food, and the Battle for Women’s Right to Vote, Laura Kumin. New York: Pegasus Books, 2020. 357 pp., $28.95, hardcover, ISBN 978-1-64313-452-9. ,I first learned about cookbooks associated with women’s suffrage thanks to this Atlas Obscura article and I was instantly fascinated. Feminism in the 20th century was often more interested in throwing off the chains of household drudgery than with enticing converts through snacks. But that is precisely the premise of All Stirred Up: Suffrage Cookbooks, Food, and the Battle for Women's Right to Vote, which is why I was so excited that I put it on my Christmas wish list. I was expecting a thorough examination of the suffrage cookbooks, the women who created them, and their place in the movement. Sadly, as a book, All Stirred Up is like an underdone cake – it looks perfect on the outside, but the inside is doughy and disappointing and could have used another 30 minutes in the oven. Laura Kumin is a former lawyer turned cooking educator and food writer. She does not have a historical background, and, as is the case with many non-historians who write food history, it shows. All Stirred Up begins, even before the introduction, with a lengthy timeline. While I find timelines to be incredibly useful, especially when dealing with complex chronology, starting the book with one was not a choice I would have made. It is confusing to the reader, who is presented lengthy and disparate facts without context or introduction. A lack of context is a theme for the book. Kumin’s introduction is part explanation of her interest in suffrage cookbooks and part layout of her main argument. She makes a compelling case that modern takes on suffrage history have largely ignored the role of cookbooks in converting skeptics to the cause. Unfortunately, this argument is not often revisited in the subsequent chapters. Most of the chapters are quite brief, some as few as eight pages, and while historical overviews abound, actual analysis is lacking. Taking up the most space are the recipe sections that follow each chapter, organized by type. Although these recipes are directly taken from the suffrage cookbooks, with modern adaptations designed by Kumin, there is no context for any of the recipes and no dates listed. Most recipe sections draw from multiple suffrage cookbooks without differentiating between them, beyond noting where the originals came from. We do not know why Kumin chose these particular recipes, how they reflected the cookbooks and times from whence they came, or even what, if any, relevance they had to the suffrage movement. For many chapters, the number of pages devoted to recipes outweigh the pages devoted to history. As for the history itself, most of it is shallow summaries meant to orient the reader to the basics of suffrage history, home economics and food science, and basic culture of the period. While this context is useful for non-historians, it seems to come at the expense of historical analysis. In addition, the chronology of the book is all over the place. The book begins in 1848, with an exercise in “time travel” in which Kumin writes in the present tense. Then zooms ahead to the Progressive Era and back again several times. At the end of Chapter 3, we’re already at the 19th Amendment in 1920, an achievement which is not really revisited for the rest of the book. Throughout the book, the suffrage movement in one decade is conflated with the same movement decades later. Little attention is paid to the context of national culture on the way in which the women's suffrage movement was operated, despite the fact that it was under operation, in one way or another, for over 70 years. Missed opportunities to make connections to other major movements, including abolitionism, Temperance (which is dismissed as detrimental to the cause, p. 78-79), Progressive reform, government regulation, etc., abound. Chapters 3, 4, and 6 are the strongest, content- and argument-wise. In Chapter 3, “From Seneca Falls to the Ballot Box,” Kumin examines the suffragists themselves and the post-Civil War resurgence of the movement. To her credit, she makes a point of mentioning African American suffragists and their shameful treatment by mainstream white suffragists, as well as male allies and the “antis” – anti-suffragists. However, points that needed more analysis were often presented as literal sidebars in the text. For instance, noted suffrage ally Frederick Douglass, instead of being included in the main text, receives a short summary in a gray box. The Beecher family get similar treatment in a sidebar about how the movement split families. Catharine Beecher, a fervent anti-suffragist, was a cookbook author and young women’s educator of some renown and who, despite conflicting ideas about suffrage, nonetheless co-wrote The American Woman’s Home with her suffragist sister. Cookbook author, fervent abolitionist, and Native American rights activist Lydia Maria Child is mentioned in a quotation, but otherwise ignored. These are just a few of many missed opportunities to engage with the subject matter more deeply – discussing how both suffragists and “antis” used women’s work and the home in their arguments for and against suffrage. Chapter 4, “We Can Peel Potatoes and Fight for the Vote, Too! Suffrage Strategies and Battle Tactics” is the strongest chapter in the book, and one of the few that cites primary sources in the endnotes. Discussing the divergent tactics between “mainstream” and “militant” suffragists, Kumin compares the mainstream work of the cookbooks, cafeterias, the “doughnut campaign,” a “Pure Food” storefront, and cooperating with agricultural extension, to the militant tactics of parades, protests, arrests, and hunger strikes. Unfortunately, she does not define who exactly is “mainstream” and who is “militant,” except to note differing tactics. Kumin argues that the more mainstream feminists were more successful in changing hearts and minds, but presents little evidence to back up this claim. In addition, despite covering the bulk of the Progressive Era, the chapter mentions, but gives little context to agricultural extension, the Temperance movement, home economics, World War I, and women’s clubs. An overview of home economics and food science comes in the following chapter, “Revolution in the Kitchen.” Chapter 6 finally addresses the cookbooks themselves, with an overview of how they were financed, celebrity contributors, and how the recipes included were reflective of the periods in which they were published. The cookbooks are still dealt with in generalizations, however, and their individuality is lost in the mix. The section on celebrities, although interesting contains another missed opportunity, as Kumin mentions one recipe contribution from noted feminist Charlotte Perkins Gilman, but not her dislike of cooking. In the section on funding, Kumin clearly notes that the cookbooks were usually designed as fundraisers for the organizations, a fact that belies her argument that cookbooks were meant to convert, though she does note they were sometimes also used as enticing premiums for subscriptions. Chapter 7 is a brief discussion of how suffragists used dinners and entertaining to support the cause. All Stirred Up ends without a clear conclusion, instead relying on Chapter 8, “What Suffrage Means for Us,” an eight-page summary of women in American politics since 1920. This final chapter makes no clear reference to the influence of the cookbooks that purportedly drove the suffrage movement and does not sum up the arguments outlined in the introduction. It is followed by 28 pages of dessert recipes. There is no explanatory postscript, only Kumin’s acknowledgements. In all, All Stirred Up does make a good point about the role of suffrage cookbooks in the movement, but it fails to back up its few arguments convincingly, particularly in light of the use of community cookbooks as fundraising tools, rather than modes of conversion to the cause. Instead of concentrating the bulk of her argument into Chapter 4, Kumin would have had a much more compelling book had she spread that argument throughout all the chapters, addressing the role of domesticity from the perspectives of both the suffragists and the antis. More primary source analysis would have enriched the narrative. Looking at the writing of major suffrage leaders to determine their personal opinions on cooking and domesticity would have added depth to her arguments. Examining the cookbooks themselves, their recipes, and the organizations and women that produced them as a chronological accounting of the movement, would have added greatly to the coherence and context of the book. Had the recipe sections been introduced by era, with headnotes and historical context for each recipe, their inclusion would have made the book both stronger and appealing to the general public. Ultimately, the book feels as though it was rushed to print, possibly to coincide with the centennial anniversary of the 19th Amendment in 2020. If you are unfamiliar with basic suffrage and food history, this may provide some good historical summaries and Kumin’s research on the 1909 Washington Women’s Cook Book is particularly strong. But, if you were hoping for a well-written, well-organized examination of the role of food in the suffrage movement and the influence of suffrage cookbooks, as I was, you’ll be sorely disappointed. I can only hope that future historians can expand on Kumin’s work. If you'd like more food history book reviews, check out the Book Review category of this blog. The Food Historian blog is supported by patrons on Patreon! Join us for awesome members-only content like free digitized cookbooks from my personal collection, e-newsletter, and even snail mail from time to time! Once again the wheels of publishing grind slowly, but I'm pleased as punch to see one of my book reviews in print again, this time in the Spring 2020 edition of the Agricultural History Journal. Canned: The Rise and Fall of Consumer Confidence in the American Food Industry. By Anna Zeide. Oakland: University of California Press, 2018. 269 pp., $34.95, hardcover, ISBN 9780520290686. Few people these days haven’t tasted canned food, but have you ever considered its origins? Tin cans versus glass jars? The science of safe canning? Anna Zeide did in her new book Canned: The Rise and Fall of Consumer Confidence in the American Food Industry. Tracking the rise of commercially canned foods in America from the condensed milk of the Civil War to modern concerns about bisphenol-A (BPA), Zeide puts canned goods firmly in historical context – connecting them to changes in technology, agricultural science, medicine, politics, and social changes. On the surface, the book is about the safety of canned goods; Zeide studies the roles of lead poisoning, spoilage, botulism, mercury in canned fish, and the 21st century issue of bisphenol-A (BPA) contamination in shaping consumer use of and confidence in canned goods. The chapters are arranged as case studies and are outlined in chronological order. The introduction outlines the history of canning technology (and safety) before moving on to condensed milk in the post-Civil War era and the rise of chemical additives and improvements in canning technology. The chapter on canned peas in the 1910s discusses the relationship between canners, agricultural research, and vertical integration of farming with vegetable varieties bred to be canned, embracing agricultural grading. The chapter on canned ripe olives addresses the threat of botulism in the 1920s, and how the canning industry resisted regulation and attempted to place the blame on careless home canners. The chapter on canned tomatoes in the 1930s outlines how canners resisted grading of canned goods, even as they embraced it for their own suppliers, and attempted to read the mind of “Mrs. Consumer,” now an economic force to be reckoned with. The chapter canned tuna and mercury contamination in the 1970s chronicles the rise of processed food more broadly, the expansion of canners beyond canned food, and the backlash against artificial ingredients, pesticides, and other contaminants in canned goods and industrial food. Finally, Zeide ends with a discussion of consumer fears about BPA in Campbell’s canned soups in the 2010s, and Campbell’s attempts to cover up health concerns even as it tried to appeal to a new, food-savvy generation of consumers. As you can probably tell, beneath the study of the relationship between consumers and food processors is the real meat of the book – on regulation of the industry. At first, early canners were happy to work with government regulators to prove themselves worthy in a crowded and competitive market. And access to agricultural colleges for crop research and federal food safety research were benefits they were only too happy to embrace. But as food processors consolidated and the 20th century wore on, canners became increasingly resistant to government regulation, oversight, and transparency. So much so that by the 2010s when Campbell’s Soup was confronted with consumer concerns about the endocrine disrupting BPA, they closed ranks and denied any safety concerns. But, despite promises to end the use of BPA in can liners and even as it hopped on other bandwagons such as the labeling of genetically modified foods, as of 2016 Campbell’s had yet to replace BPA in their cans. Zeide concludes the book by outlining why government regulation and collective action is more effective in maintaining food safety than the industry’s beloved individual action. Throughout the book, food processors claim that “Mrs. Consumer” can choose for herself which brands are the safest and highest quality, but that ignores circumstances beyond consumer control, such as the case study Zeide cites in which consumers fed on a diet devoid of canned goods and full of locally produced whole foods actually saw their BPA levels increase, likely due to the use of BPA in plastics used as part of the even minimal food processing, such as in the milking industry or in the production of spices in other countries (p. 183). Ultimately, Zeide tries to place canned goods briefly in context in the conclusion – that access to canned fruits and vegetables gave a whole subset of Americans access to nutrients they might not have had access to before, and that emotional responses to the foods of our childhoods will give canned goods longevity. Although at various places throughout the book Zeide makes mention of potential class issues surrounding canned goods, and the assumptions of canners that “Mrs. Consumer” was white and middle class, a more thorough examination of class and race in the context of canned goods would have made this book even stronger, especially considering the emphasis on consumer marketing. However, despite this omission, Canned is ultimately a strong addition to food historiography and I applaud Zeide for her detailed work and her ability to place events and people in context, drawing connections and conclusions that are well supported by her research. If you enjoyed this book review, please consider becoming a member or joining us on Patreon. Members and patrons get special perks like access to members-only content and discounts on programs and classes.

Okay folks, just 6 months after submitting and 9 months after receiving the invitation and book, my review of Capitalist Pigs is finally in print in the latest issue of Agricultural History - the journal of the Agricultural History Society. It's a pretty great issue, so I recommend you check out the few articles they have put up online. Alas, my review is not one of them, BUT! Being the rebel that I am, and seeing that I wrote this review for free (albeit in exchange for an advanced copy of the book, which was pretty cool), I'm going to do you a solid and post it here for you to read for yourself. For photographic proof, click through the images above! Capitalist Pigs: Pigs, Pork, and Power in America. By J.L. Anderson. Morgantown: West Virginia University Press, 2018. 300 pp., $34.99, paperback, ISBN 978-1-946684-73-8. “Capitalist pigs” is a term most frequently attributed to stereotypical Soviet protagonists describing Americans, or perhaps fat hogs in suits and top hats representing greedy businessmen in political cartoons. But in Capitalist Pigs: Pigs, Pork, and Power in America, J.L. Anderson puts a clever turn on the phrase as he explores the role of pigs and pork in America from the early Colonial period to the present. In Capitalist Pigs, Anderson argues that hogs have played a unique role in the development of the United States, and that the United States played a unique role in the development of the hog. “Americans maximized opportunities for the proliferation of the hog, even amid changing values and ideals about empire, agriculture, cities, and health.” (5). In particular, Anderson emphasizes that the story of the hog in America is one of excess, as farmers and marketers alike attempted to “transcend limits” on production. Capitalist Pigs covers the Colonial period to the present in the United States and is organized thematically rather than chronologically. Anderson covers such topics as free-range hogs and their influence on early settlements, pork consumption and its shifting role from frontier and working class food to re-branded “other white meat,” early industrialization of pork production and husbandry, including a discussion of hog cholera and enclosure, the role of the hog as garbage disposal, from our earliest urban areas to the industrialized present, and finally with a discussion of the modern industrialization of the hog, including changing its very physique to match modern consumer tastes and the controversial rise of confined animal feeding operations (CAFOs). Capitalist Pigs is well-researched and the broad chronology of the book provides a sweeping view of the influence of the hog on American culture and development throughout the centuries, giving needed context to historians of all stripes. Anderson is at his most compelling when he includes the voices of marginalized people and his sections on indigenous populations, enslaved people, and the Civil Rights movement are among his best. For urban and environmental historians, the discussion of the role of hogs in reshaping the landscape and the transition of urban spaces to exclude them, even as they continued to operate as waste disposal systems, will be of particular interest. Twentieth century historians, particularly agriculture historians, will be impressed by his discussion of the industrialization of hog production and marketing from the 1940s on. Anderson’s background as a public historian means his writing is clear, straightforward, and free of jargon and unnecessarily convoluted sentences. His writing style is engaging and would appeal to not only professional historians, but likely students and laypeople as well. Although Anderson’s writing style is clear, his main arguments are not. It seems as though Anderson could not quite decide whether to write Capitalist Pigs as a more technical agricultural history, or as a social history, and decided to split the difference. Anderson notes the influence of pigs in the institution of slavery, subsistence farms, and as a “mortgage lifter.” But the primary argument outlined in the introduction is focused instead on how Americans changed the pig. An interesting, if somewhat divergent take from the usual social history bent of most food histories, the argument is ultimately a weak one. Although Anderson discusses extensively in the latter half of the book how farmers industrialized and economized pork production and even changed the body shape of pigs to accommodate changing consumer tastes, he spends little time discussing the effects on the pigs themselves. Although breeding is mentioned frequently, the only mention of any particular breed in the entire book is about how heritage breeds have become more fashionable in modern nose-to-tail cuisine and sustainable agriculture (172-73), despite the fact that discussing the various breeds of pig throughout the book would have lent weight to later industrial changes and changing consumer tastes. He also skirts around the effects of industrialization on the hogs themselves - only in a photo caption does he mention accusations of cruelty in hog confinement operations (201). In addition, although the title and discussions in several chapters imply that hogs played a significant role in building America’s capitalist system, Anderson does not quite make those connections clear throughout the chapters, and discussion of meat-packing beyond the 1850s is conspicuously absent. Given the influential role of America’s meat-packers in the late nineteenth century in both industrial capitalism and union history, this is a curious oversight. Although Capitalist Pigs doesn’t quite live up to the premise of its fantastic title, it is a worthy combination of agriculture and food history - combining the history of industrial technology and consumer uses of hogs throughout the entirety of American history. Food and agriculture historians in particular will find much of use, but American social, environmental, rural, urban, and Civil War historians will also enjoy the read. If you enjoyed this book review, consider becoming a member of The Food Historian! You can join online here, or you can join us on Patreon. Members get access to members-only sections of this website, special updates, plus discounts on future events and classes. And you'll help support free content like this for everyone. Join today!

Sowing the Seeds of Victory: American Gardening Programs of World War I by Rose Hayden-Smith is one of the few books on the topic of wartime gardening that scarcely mentions World War Two. The focus on gardening and horticultural movements prior to and during the First World War is a welcome addition to the small but growing pantheon of food history books from that era. Hayden-Smith, although a historian, is also a sustainable gardening advocate and it shows in this book - a little too much for my taste. Hayden-Smith uses the history of World War I war gardens as justification and inspiration for modern gardening movements, using period primary source material as evidence. If you are new to the ideas surrounding the modern sustainable agriculture and community gardening movement, you might find this interesting, but as someone who has followed said movement since high school, I found the constant references and asides to the modern era annoying and unnecessary. I would have vastly preferred if Hayden-Smith had made her connections between past and present at the end of each chapter, rather than interrupting the flow of the historical with the modern. Modern gardening aside, Hayden-Smith covers the World War I gardening movement by taking in-depth looks at Charles Lathrop Pack and the National War Garden Commission, the United States School Garden Army, the Pennsylvania School of Horticulture for Women, and the Woman's Land Army of America. Although the Woman's Land Army of America has been admirably covered in-depth by Elaine Weiss's Fruits of Victory, the other three topics have been little-studied and Hayden-Smith has done an admirable job of digging through obscure archives and has brought to light new resources from California (where she lives). Another chapter outlines the propaganda work of the war garden and food conservation movements and a final chapter takes a quick look at gardening in the Interwar to Post-War years in the United States. The book concludes with a summation of the war garden movement throughout the decades following and a call to action and advocacy for modern community gardening efforts. The best chapter is on the Pennsylvania School of Horticulture for Women - it is well-researched, interesting, and provides new insights into the origins of both the Woman's Land Army of America and Cornell University's cooperative extension home economics program, headed by Martha Van Renssalaer - a graduate of the horticulture school. Although the information is fascinating in the other chapters, they are somewhat poorly organized. For instance, in the chapter on the National War Garden Commission, Hayden-Smith references Charles Lathrop Pack numerous times, but doesn't introduce his background or any biographical information until halfway through the chapter (the chapter begins on page 32; Pack is finally "introduced" on page 48). In addition, perhaps at the behest of the publisher, there are constant parenthetical asides that in other books would have been asterisked footnotes, or simply incorporated into the text. Parenthetical asides pointing out obvious connections between the source material and modern food and gardening movements were especially annoying. It was a frustrating read - I could see and feel the potential for a truly excellent book, but was stymied every time a statement was followed by another saying the exact same thing, information was unnecessarily put in a parenthetical aside, or information was written in an order that made little sense. Frankly, the book was in serious need of a good editor (not a copy editor, although I did also find a few typos) - someone to give advice on how to organize the arguments and the best order for the book. Because although each topic/chapter was interesting in and of itself, there was also little to tie all four topics to each other. I would be interested to know if the book had been peer-reviewed before publication. In all, I would recommend it to anyone interested in the food and/or gardening history of World War I, but don't expect an easy read. If you would like to purchase Sowing the Seeds of Victory through this link, I will receive a small commission.  As part of my new annual jolabokaflod, I ordered Mastering the Art of Soviet Cooking: A Memoir of Food & Longing by cookbook author and Soviet/Russian ex-pat Anya von Bremzen. Ever since I took a semester of Russian on a whim my senior year in college (which helped me properly pronounce the Russian words liberally sprinkled throughout the text), I've been intensely interested in Russian culture and especially food. This book is first and foremost a memoir, not a cookbook, despite the cookbooky title. Von Bremzen and her mother Larisa chronicle their love-hate relationship with the Soviet Union and ultimate escape when Anya was ten years old. Rich in real family histories, idiosyncrasies, and stories, Von Bremzen uses her sometimes fraught family life as a lens to examine the Soviet Union more closely than she had as a child. At its heart, this book is a paradoxical confession - while Anya and Larisa both hate the violence and conformity of the USSR (or CCCP, in Russian), they also long for the nostalgic tastes of their homeland, like black sourdough bread, Kazakh apples, crispy kotleta, highly processed kolbasa, and other difficult-to-procure tastes of Rodina ("Homeland" with a capital H). The book is organized by decade, beginning with the Russian Revolution in the 1910s and the memories of Anya's grandparents. Each chapter is liberally larded with much-needed historical context on the political and social movements and upheavals at the time, illustrated by the lives of von Bremzen's immediate family, relatives, and friends. With each decade, not only does von Bremzen give the social and historical background to the food discussed, she also chronicles the dinner parties she and her mother recreated for each decade, using historically accurate recipes. The last chapter ends in the twenty-first century with Putin's rise to power and the burgeoning obsession in petro-fueled Russia with all things expensive. The book itself ends with a single recipe illustrating each chapter. My Ex Libris edition also comes with a reader's guide featuring a zakushki party menu with recipes at the back. I found this book incredibly compelling, but here and there the historian in me missed some more in-depth narrative. For example, von Bremzen chronicles Stalin's food industry narkom ("people's commissar") Anastas Mikoyan as he journeys to the United States in 1936 at Stalin's behest to study the American food industry. Von Bremzen lists all of the revelations he found abroad, including his amazement at the American hamburger - a cheap and filling snack food - which von Bremzen was horrified to find out was the inspiration for the ubiquitous Soviet kotleta - a thin beef (or chicken or pork) patty with a crispy breading crust deep fried. But while she discusses the consumer end of things and the people who directed the food itself, she does not even mention the manufacturing process nor the workers who produced it. Von Bremzen does discuss briefly the plight of rural agricultural peasants throughout the decades, but her personal history as a city-bred Muscovite doesn't lend itself well to interpreting that agricultural history. Her tantalizing mentions of the Kazakh apple industry, Ukranian pork and wheat industry, and the rich culinary histories of Central Asian nations leave me wanting more information and context. Alas, there is only so much you can fit into a memoir before it comes a history book. This memoir was not only a fascinating read, I learned a lot about the fraught, deprived, and often violent history of the Soviet Union as well as more about the part-industrialized, part-homemade foods that former Soviets speak of with such fondness. I strongly recommend this book for anyone interested in Soviet history or Russian culture. If you'd like to purchase Mastering the Art of Soviet Cooking through this link, I will receive a small commission. |

AuthorSarah Wassberg Johnson has an MA in Public History from the University at Albany and studies early 20th century food history. Archives

July 2024

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed