|

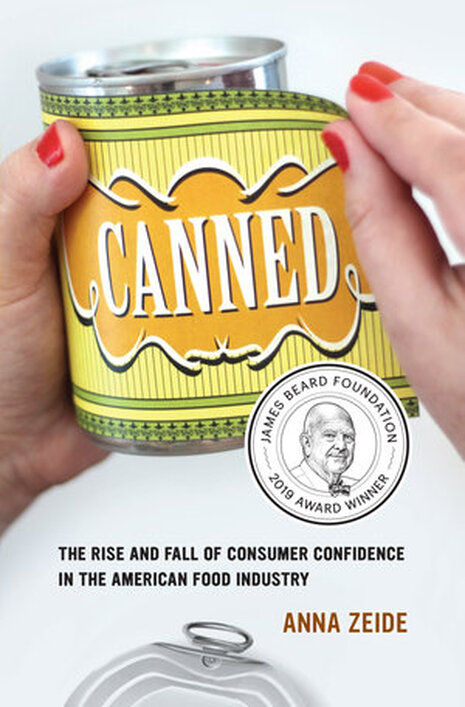

Once again the wheels of publishing grind slowly, but I'm pleased as punch to see one of my book reviews in print again, this time in the Spring 2020 edition of the Agricultural History Journal. Canned: The Rise and Fall of Consumer Confidence in the American Food Industry. By Anna Zeide. Oakland: University of California Press, 2018. 269 pp., $34.95, hardcover, ISBN 9780520290686. Few people these days haven’t tasted canned food, but have you ever considered its origins? Tin cans versus glass jars? The science of safe canning? Anna Zeide did in her new book Canned: The Rise and Fall of Consumer Confidence in the American Food Industry. Tracking the rise of commercially canned foods in America from the condensed milk of the Civil War to modern concerns about bisphenol-A (BPA), Zeide puts canned goods firmly in historical context – connecting them to changes in technology, agricultural science, medicine, politics, and social changes. On the surface, the book is about the safety of canned goods; Zeide studies the roles of lead poisoning, spoilage, botulism, mercury in canned fish, and the 21st century issue of bisphenol-A (BPA) contamination in shaping consumer use of and confidence in canned goods. The chapters are arranged as case studies and are outlined in chronological order. The introduction outlines the history of canning technology (and safety) before moving on to condensed milk in the post-Civil War era and the rise of chemical additives and improvements in canning technology. The chapter on canned peas in the 1910s discusses the relationship between canners, agricultural research, and vertical integration of farming with vegetable varieties bred to be canned, embracing agricultural grading. The chapter on canned ripe olives addresses the threat of botulism in the 1920s, and how the canning industry resisted regulation and attempted to place the blame on careless home canners. The chapter on canned tomatoes in the 1930s outlines how canners resisted grading of canned goods, even as they embraced it for their own suppliers, and attempted to read the mind of “Mrs. Consumer,” now an economic force to be reckoned with. The chapter canned tuna and mercury contamination in the 1970s chronicles the rise of processed food more broadly, the expansion of canners beyond canned food, and the backlash against artificial ingredients, pesticides, and other contaminants in canned goods and industrial food. Finally, Zeide ends with a discussion of consumer fears about BPA in Campbell’s canned soups in the 2010s, and Campbell’s attempts to cover up health concerns even as it tried to appeal to a new, food-savvy generation of consumers. As you can probably tell, beneath the study of the relationship between consumers and food processors is the real meat of the book – on regulation of the industry. At first, early canners were happy to work with government regulators to prove themselves worthy in a crowded and competitive market. And access to agricultural colleges for crop research and federal food safety research were benefits they were only too happy to embrace. But as food processors consolidated and the 20th century wore on, canners became increasingly resistant to government regulation, oversight, and transparency. So much so that by the 2010s when Campbell’s Soup was confronted with consumer concerns about the endocrine disrupting BPA, they closed ranks and denied any safety concerns. But, despite promises to end the use of BPA in can liners and even as it hopped on other bandwagons such as the labeling of genetically modified foods, as of 2016 Campbell’s had yet to replace BPA in their cans. Zeide concludes the book by outlining why government regulation and collective action is more effective in maintaining food safety than the industry’s beloved individual action. Throughout the book, food processors claim that “Mrs. Consumer” can choose for herself which brands are the safest and highest quality, but that ignores circumstances beyond consumer control, such as the case study Zeide cites in which consumers fed on a diet devoid of canned goods and full of locally produced whole foods actually saw their BPA levels increase, likely due to the use of BPA in plastics used as part of the even minimal food processing, such as in the milking industry or in the production of spices in other countries (p. 183). Ultimately, Zeide tries to place canned goods briefly in context in the conclusion – that access to canned fruits and vegetables gave a whole subset of Americans access to nutrients they might not have had access to before, and that emotional responses to the foods of our childhoods will give canned goods longevity. Although at various places throughout the book Zeide makes mention of potential class issues surrounding canned goods, and the assumptions of canners that “Mrs. Consumer” was white and middle class, a more thorough examination of class and race in the context of canned goods would have made this book even stronger, especially considering the emphasis on consumer marketing. However, despite this omission, Canned is ultimately a strong addition to food historiography and I applaud Zeide for her detailed work and her ability to place events and people in context, drawing connections and conclusions that are well supported by her research. If you enjoyed this book review, please consider becoming a member or joining us on Patreon. Members and patrons get special perks like access to members-only content and discounts on programs and classes.

2 Comments

Carla R Lesh

5/21/2020 12:50:41 pm

Family stories tell of ancestors who developed a canning company in Northwest Arkansas in the 1880s. They took stock shares when they sold to Continental Can. A sound financial move.

Reply

5/22/2020 05:41:57 pm

That's so fascinating, Carla! Yes I think the most interesting thing I learned from this book was just how many small regional canneries existed in the 19th century before they began consolidating.

Reply

Your comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

AuthorSarah Wassberg Johnson has an MA in Public History from the University at Albany and studies early 20th century food history. Archives

July 2024

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed