|

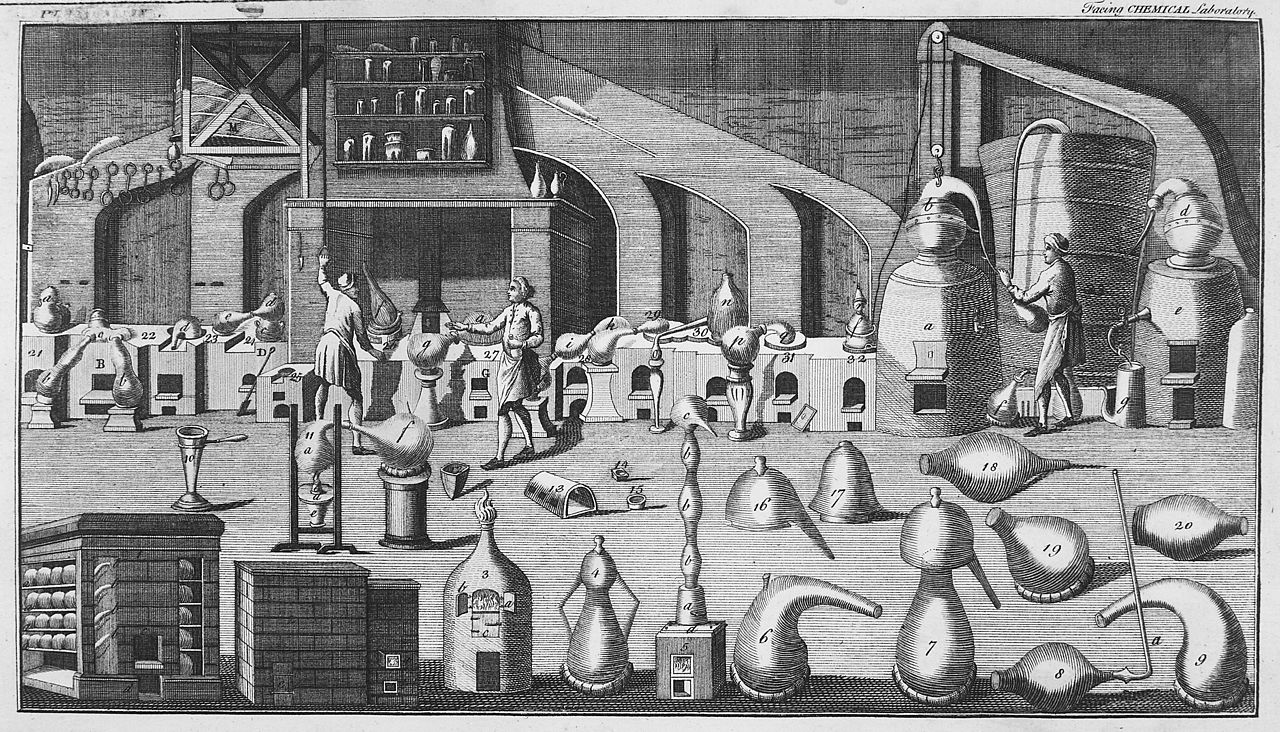

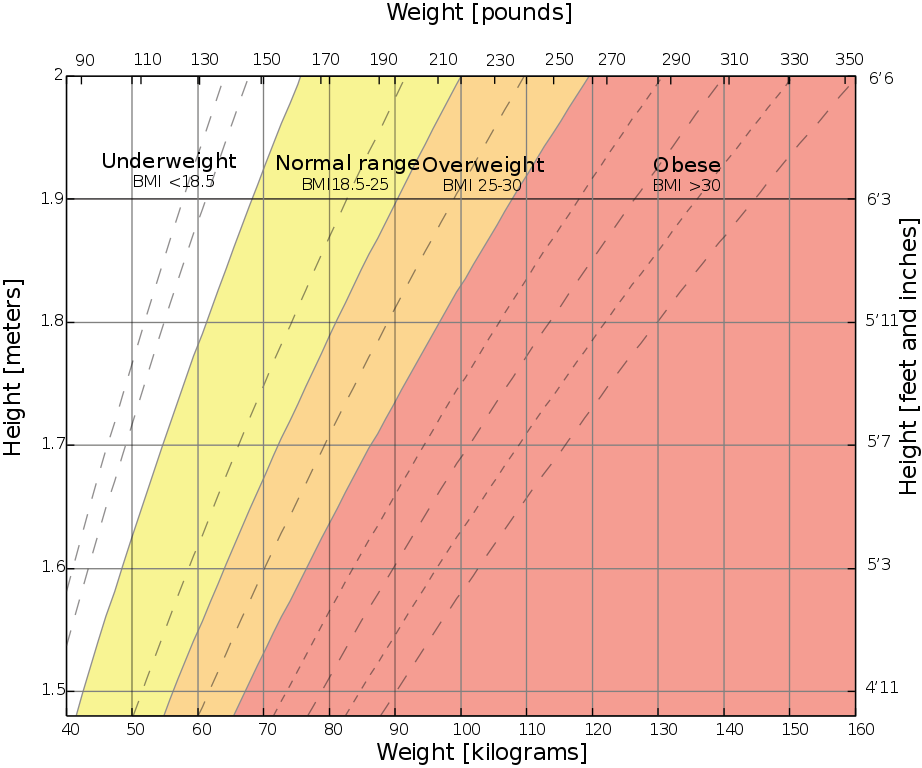

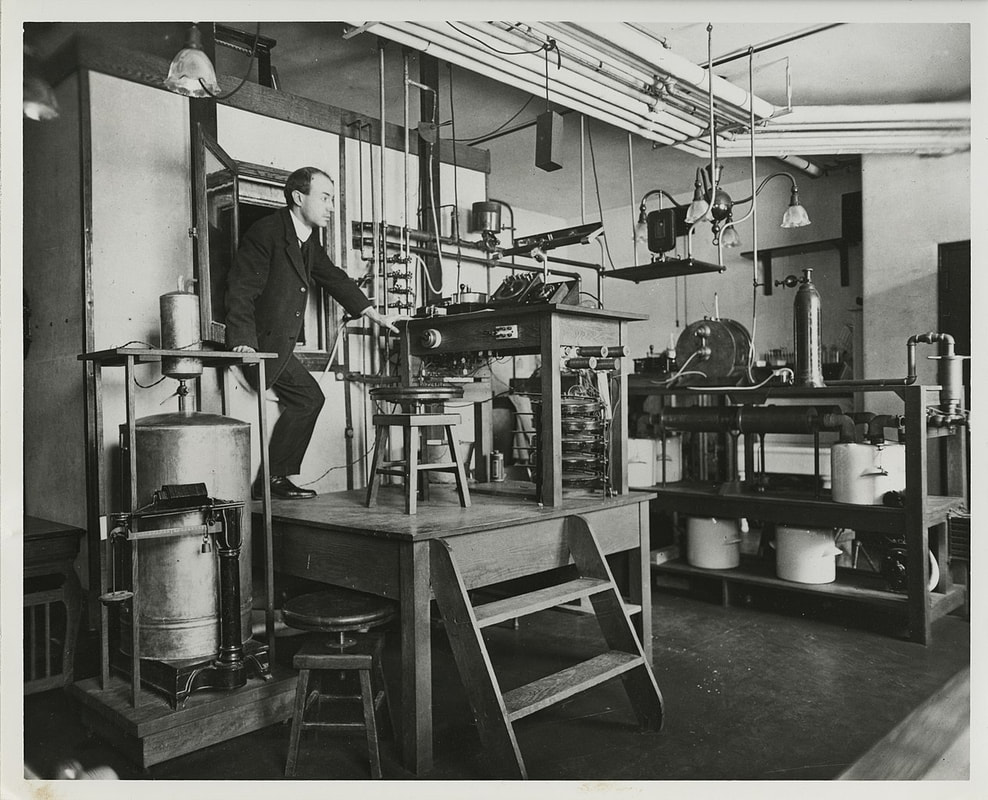

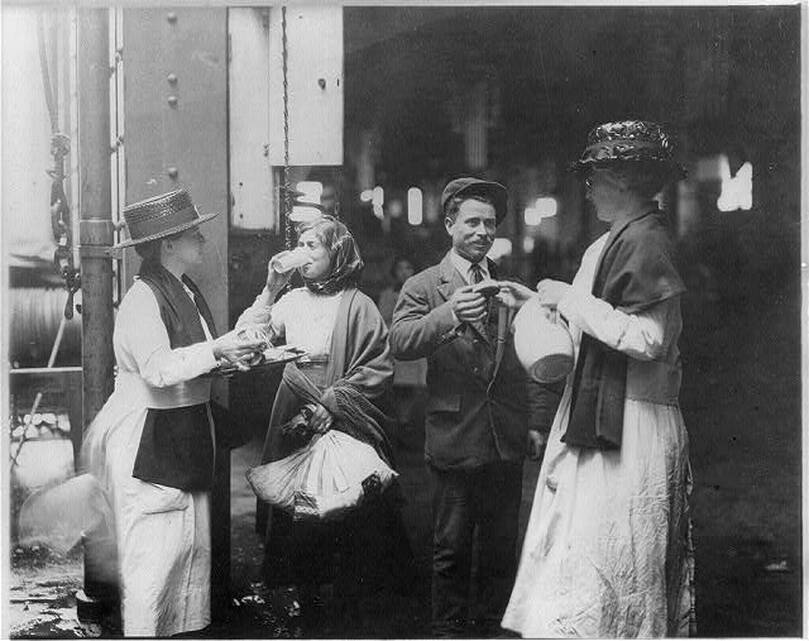

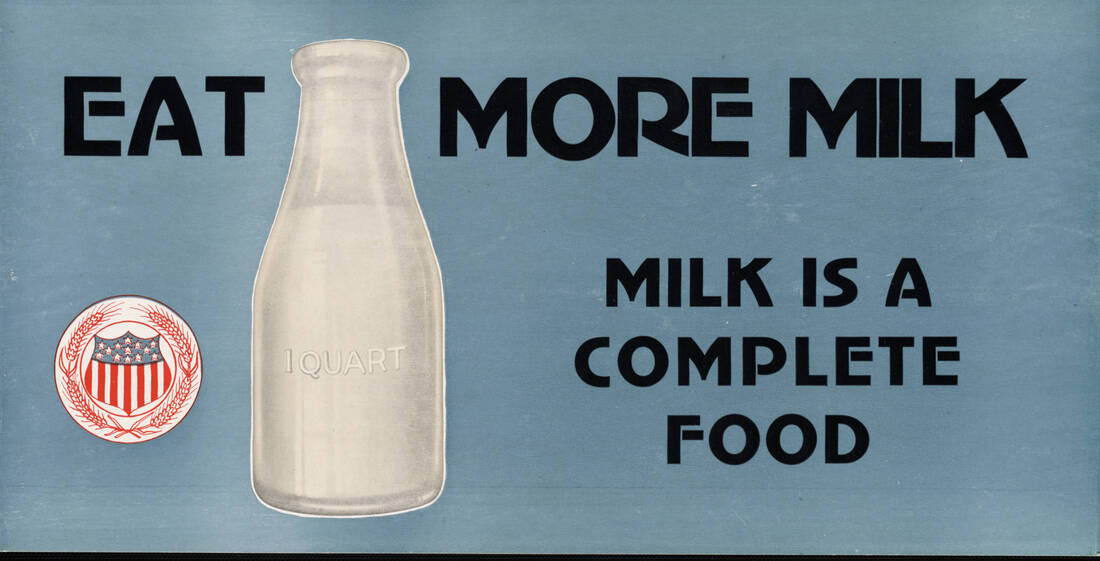

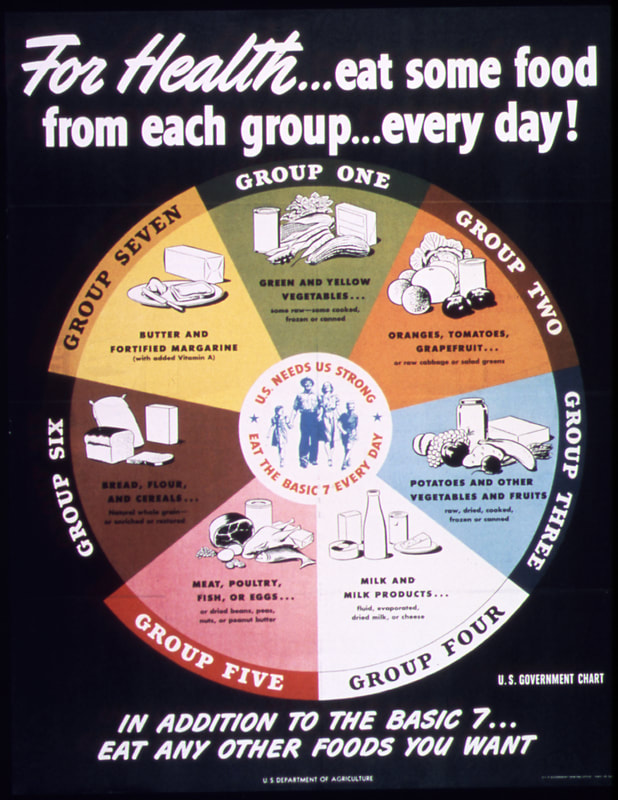

The short answer? At least in the United States? Yes. Let's look at the history and the reasons why. I post a lot of propaganda posters for World War Wednesday, and although it is implied, I don't point out often enough that they are just that - propaganda. They are designed to alter peoples' behavioral patterns using a combination of persuasion, authority, peer pressure, and unrealistic portrayals of culture and society. In the last several months of sharing propaganda posters on social media for World War Wednesday, I've gotten a couple of comments on how much they reflect an exclusively White perspective. Although White Anglo-Saxon Protestant culture was the dominant culture in the United States at the time, it was certainly not the only culture. And its dominance was the result of White supremacy and racism. This is reflected in the nutritional guidelines and nutrition science research of the time. The First World War takes place during the Progressive Era under a president who re-segregated federal workplaces that had been integrated since Reconstruction. It was also a time when eugenics was in full swing, and the burgeoning field of nutrition science was using racism as justifications for everything from encouraging assimilation among immigrant groups by decrying their foodways and promoting White Anglo-Saxon Protestant foodways like "traditional" New England and British foods to encouraging "better babies" to save the "White race" from destruction. Nutrition science research with human subjects used almost exclusively adult White men of middle- and upper-middle class backgrounds - usually in college. Certain foods, like cow's milk, were promoted heavily as health food. Notions of purity and cleanliness also influenced negative attitudes about immigrants, African Americans, and rural Americans. During World War II, Progressive-Era-trained nutritionists and nutrition scientists helped usher in a stereotypically New England idea of what "American" food looked like, helping "kill" already declining regional foodways. Nutrition research, bolstered by War Department funds, helped discover and isolate multiple vitamins during this time period. It's also when the first government nutrition guidelines came out - the Basic 7. Throughout both wars, the propaganda was focused almost exclusively on White, middle- and upper-middle-class Americans. Immigrants and African Americans were the target of some campaigns for changing household habits, usually under the guise of assimilation. African Americans were also the target of agricultural propaganda during WWII. Although there was plenty of overt racism during this time period, including lynching, race massacres, segregation, Jim Crow laws, and more, most of the racism in nutrition, nutrition science, and home economics came in two distinct types - White supremacy (that is, the belief that White Anglo-Saxon Protestant values were superior to every other ethnicity, race, and culture) and unconscious bias. So let's look at some of the foundations of modern nutrition science through these lenses. Early Nutrition ScienceNutrition Science as a field is quite young, especially when compared to other sciences. The first nutrients to be isolated were fats, carbohydrates, and proteins. Fats were the easiest to determine, since fat is visible in animal products and separates easily in liquids like dairy products and plant extracts. The term "protein" was coined in the 1830s. Carbohydrates began to be individually named in the early 19th century, although that term was not coined until the 1860s. Almost immediately, as part of nearly any early nutrition research, was the question of what foods could be substituted "economically" for other foods to feed the poor. This period of nutrition science research coordinated with the Enlightenment and other pushes to discover, through experimentation, the mechanics of the universe. As such, it was largely limited to highly educated, White European men (although even Wikipedia notes criticism of such a Euro-centric approach). As American colleges and universities, especially those driven by the Hatch Act of 1877, expanded into more practical subjects like agriculture, food and nutrition research improved. American scientists were concerned more with practical applications, rather than searching for knowledge for knowledge's sake. They wanted to study plant and animal genetics and nutrition to apply that information on farms. And the study of human nutrition was not only to understand how humans metabolized foods, but also to apply those findings to human health and the economy. But their research was influenced by their own personal biases, conscious and unconscious. The History of Body Mass Index (BMI)Body Mass Index, or BMI, is a result of that same early 19th century time period. It was invented by Belgian mathematician Lambert Adolphe Jacques Quetelet in the 1830s and '40s specifically as a "hack" for determining obesity levels across wide swaths of population, not for individuals. Quetelet was a trained astronomist - the one field where statistical analysis was prevalent. Quetelet used statistics as a research tool, publishing in 1835 a book called Sur l'homme et le développement de ses facultés, ou Essai de physique sociale, the English translation of which is usually called A Treatise on Man and the Development of His Faculties. In it, he discusses the use of statistics to determine averages for humanity (mainly, White European men). BMI became part of that statistical analysis. Quetelet named the index after himself - it wasn't until 1972 that researcher Ancel Keys coined the term "Body Mass Index," and as he did so he complained that it was no better or worse than any other relative weight index. Quetelet's work went on to influence several famous people, including Francis Galton, a proponent of social Darwinism and scientific racism who coined the term "eugenics," and Florence Nightingale, who met him in person. As a tool for measuring populations, BMI isn't bad. It can look at statistical height and weight data and give a general idea of the overall health of population. But when it is used as a tool to measure the health of individuals, it becomes extremely flawed and even dangerous. Quetelet had to fudge the math to make the index work, even with broad populations. And his work was based on White European males who he considered "average" and "ideal." Quetelet was not a nutrition scientist or a doctor - this "ideal" was purely subjective, not scientific. Despite numerous calls to abandon its use, the medical community continues to use BMI as a measure of individual health. Because it is a statistical tool not based on actual measures of health, BMI places people with different body types in overweight and obese categories, even if they have relatively low body fat. It can also tell thin people they are healthy, even when other measurements (activity level, nutrition, eating disorders, etc.) are signaling an unhealthy lifestyle. In addition, fatphobia in the medical community (which is also based on outdated ideas, which we'll get to) has vilified subcutaneous fat, which has less impact on overall health and can even improve lifespans. Visceral fat, or the abdominal fat that surrounds your organs, can be more damaging in excess, which is why some scientists and physicians advocate for switching to waist ratio measurements. So how is this racist? Because it was based on White European male averages, it often punishes women and people of color whose genetics do not conform to Quetelet's ideal. For instance, people with higher muscle mass can often be placed in the "overweight" or even "obese" category, simply because BMI uses an overall weight measure and assumes a percentage of it is fat. Tall people and people with broader than "ideal" builds are also not accurately measured. The History of the CalorieAlthough more and more people are moving away from measuring calories as a health indicator, for over 100 years they have reigned as the primary measure of food intake efficiency by nutritionists, doctors, and dieters alike. The calorie is a unit of heat measurement that was originally used to describe the efficiency of steam engines. When Wilbur Olin Atwater began his research into how the human body metabolizes food and produces energy, he used the calorie to measure his findings. His research subjects were the White male students at Wesleyan University, where he was professor. Atwater's research helped popularize the idea of the calorie in broader society, and it became essential learning for nutrition scientists and home economists in the burgeoning field - one of the few scientific avenues of study open to women. Atwater's research helped spur more human trials, usually "Diet Squads" of young middle- and upper-middle-class White men. At the time, many papers and even cookbooks were written about how the working poor could maximize their food budgets for effective nutrition. Socialists and working class unionists alike feared that by calculating the exact number of calories a working man needed to survive, home economists were helping keep working class wages down, by showing that people could live on little or inexpensive food. Calculating the calories of mixed-food dishes like casseroles, stews, pilafs, etc. was deemed too difficult, so "meat and three" meals were emphasized by home economists. Making "American" FoodEfforts to Americanize and assimilate immigrants went into full swing in the late 19th and early 20th centuries as increasing numbers of "undesirable" immigrants from Ireland, southern Italy, Greece, the Middle East, China, Eastern Europe (especially Jews), Russia, etc. poured into American cities. Settlement workers and home economists alike tried to Americanize with varying degrees of sensitivity. Some were outright racist, adopting a eugenics mindset, believing and perpetuating racist ideas about criminology, intelligence, sanitation, and health. Others took a more tempered approach, trying to convince immigrants to give up the few things that reminded them of home - especially food. These often engaged in the not-so-subtle art of substitution. For instance, suggesting that because Italian olive oil and butter were expensive, they should be substituted with margarine. Pasta was also expensive and considered to be of dubious nutritional value - oatmeal and bread were "better." A select few realized that immigrant foodways were often nutritionally equivalent or even superior to the typical American diet. But even they often engaged in the types of advice that suggested substituting familiar ingredients with unfamiliar ones. Old ideas about digestion also influenced food advice. Pickled vegetables, spicy foods, and garlic were all incredibly suspect and scorned - all hallmarks of immigrant foodways and pushcart operators in major American cities. The "American" diet advocated by home economists was highly influenced by Anglo-Saxon and New England ideals - beef, butter, white bread, potatoes, whole cow's milk, and refined white sugar were the nutritional superstars of this cuisine. Cooking foods separately with few sauces (except white sauce) was also a hallmark - the "meat and three" that came to dominate most of the 20th century's food advice. Rooted in English foodways, it was easy for other Northern European immigrants to adopt. Although French haute cuisine was increasingly fashionable from the Gilded Age on, it was considered far out of reach of most Americans. French-style sauces used by middle- and lower-class cooks were often deemed suspect - supposedly disguising spoiled meat. Post-Civil War, Yankee New England foodways were promoted as "American" in an attempt to both define American foodways (which reflected the incredibly diverse ecosystems of the United States and its diverse populations) and to unite the country after the Civil War. Sarah Josepha Hale's promotion of Thanksgiving into a national holiday was a big part of the push to define "American" as White and Anglo-Saxon. This push to "Americanize" foodways also neatly ignores or vilifies Indigenous, Asian-American, and African American foodways. "Soul food," "Chinese," and "Mexican" are derided as unhealthy junk food. In fact, both were built on foundations of fresh, seasonal fruits, vegetables, and whole grains. But as people were removed from land and access to land, the they adapted foodways to reflect what was available and what White society valued - meat, dairy, refined flour, etc. Asian food in particular was adapted to suit White palates. We won't even get into the term "ethnic food" and how it implies that anything branded as such isn't "American" (e.g. White). Divorcing foodways from their originators is also hugely problematic. American food has a big cultural appropriation problem, especially when it comes to "Mexican" and "Asian" foods. As late as the mid-2000s, the USDA website had a recipe for "Oriental salad," although it has since disappeared. Instead, we get "Asian Mango Chicken Wraps," and the ingredients of mango, Napa cabbage, and peanut butter are apparently what make this dish "Asian," rather than any reflection of actual foodways from countries in Asia. Milk - The Perfect FoodCombining both nutrition research of the 19th century and also ideas about purity and sanitation, whole cow's milk was deemed by nutrition scientists and home economists to be "the perfect food" - as it contained proteins, fats, and carbohydrates, all in one package. Despite issues with sanitation throughout the 19th century (milk wasn't regularly pasteurized until the 1920s), milk became a hallmark of nutrition advice throughout the Progressive Era - advice which continues to this day. Throughout the history of nutritional guidelines in the U.S., milk and dairy products have remained a mainstay. But the preponderance of advice about dairy completely ignores that wide swaths of the population are lactose intolerant, and/or did not historically consume dairy the way Europeans did. Indigenous Americans, and many people of African and Asian descent historically did not consume cow's milk and their bodies often do not process it well. This fact has been capitalized upon by both historic and modern racists, as milk as become a symbol of the alt-right. Even today, the USDA nutrition guidelines continue to recommend at least three servings of dairy per day, an amount that can cause long term health problems in communities that do not historically consume large amounts of dairy. Nutrition Guidelines HistoryBecause Anglo-centric foodways were considered uniquely "American" and also the most wholesome, this style of food persisted in government nutritional guidelines. Government-issued food recommendations and recipes began to be released during the First World War and continued during the Great Depression and World War II. These guidelines and advice generally reinforced the dominant White culture as the most desirable. Vitamins were first discovered as part of research into the causes of what would come to be understood as vitamin deficiencies. Scurvy (Vitamin C deficiency), rickets (Vitamin D deficiency), beriberi (Vitamin B1 or thiamine deficiency), and pellagra (Vitamin B2 or niacin deficiency) plagued people around the world in the 19th and early 20th centuries. Vitamin C was the first to be isolated in 1914. The rest followed in the 1930s and '40s. Vitamin fortification took off during World War II. The Basic 7 guidelines were first released during the war and were based on the recent vitamin research. But they also, consciously or not, reinforced white supremacy through food. Confident that they had solved the mystery of the invisible nutrients necessary for human health, American nutrition scientists turned toward reconfiguring them every which way possible. This is the history that gives us Wonder Bread and fortified breakfast cereals and milk. By divorcing vitamins from the foods in which they naturally occur (foods that were often expensive or scarce), nutrition scientists thought they could use equivalents to maintain a healthy diet. As long as people had access to vitamins, carbohydrates, proteins, and fats, it didn't matter how they were delivered. Or so they thought. This policy of reducing foods to their nutrients and divorcing food from tradition, culture, and emotion dates back to the Progressive Era and continues to today, sometimes with disastrous consequences. Commodities & NutritionDivorcing food from culture is one government policy Indigenous people understand well. U.S. treaty violations and land grabs led to the reservation system, which forcibly removed Native people from their traditional homelands, divorcing them from their traditional foodways as well. Post-WWII, the government helped stabilize crop prices by purchasing commodity foods for use in a variety of programs operated by the United States Department of Agriculture (USDA), including the National School Lunch Program, Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children (WIC), and the Food Distribution Program on Indian Reservations (FDPIR) program. For most of these programs, the government purchases surplus agricultural commodities to help stabilize the market and keep prices from falling. It then distributes the foods to low-income groups as a form of food assistance. Commodity foods distributed through the FDPIR program were generally canned and highly processed - high in fat, salt, and sugar and low in nutrients. This forced reliance on commodity foods combined with generational trauma and poverty led to widespread health disparities among Indigenous groups, including diabetes and obesity. Which is why I was appalled to find this cookbook the other day. Commodity Cooking for Good Health, published by the USDA in 1995 (1995!) is a joke, but it illustrates how pervasive and long-lasting the false equivalency of vitamins and calories can be. The cookbook starts with an outline of the 1992 Food Pyramid, whose base rests on bread, pasta, cereal, and rice. It then goes to outline how many servings of each group Indigenous people should be eating, listing 2-3 servings a day for the dairy category, but then listing only nonfat dry milk, evaporated milk, and processed cheese as the dairy options. In the fruit group, it lists five different fruit juices as servings of fruit. It has a whole chapter on diabetes and weight loss as well as encouraging people to count calories. With the exception of a recipe for fry bread, one for chili, and one for Tohono O'odham corn bread, the remainder of the recipes are extremely European. Even the "Mesa Grande Baked Potatoes" are not, as one would assume from the title, a fun take on baked whole potatoes, but rather a mixture of dehydrated mashed potato flakes, dried onion soup mix, evaporated milk, and cheese. You can read the whole cookbook for yourself, but the fact of the matter is that the USDA is largely responsible for poor health on reservations, not only because it provides the unhealthy commodity foods, but also because it was founded in 1862, the height of the Indian Wars, during attempts by the federal government at genocide and successful land grabs. Although the Bureau of Indian Affairs (BIA) under the Department of the Interior was largely responsible for the reservation system, the land grant agricultural college system started by the Hatch Act was literally built on the sale of stolen land. In addition, the USDA has a long history of dispossessing Black farmers, an issue that continues to this day through the denial of farm loans. Thanks to redlining, people of color, especially Black people, often live in segregated school districts whose property taxes are inadequate to cover expenses. Many children who attend these schools are low-income, and rely on free or reduced lunch delivered through the National School Lunch Program, which has been used for decades to prop up commodity agriculture. Although school lunch nutrition efforts have improved in recent years, many hot lunches still rely on surplus commodities and provide inadequate nutrition. Issues That PersistEven today, the federal nutrition guidelines, administered by the USDA, emphasize "meat and three" style meals accompanied by dairy. And while the recipe section is diversifying, it is still all-too-often full of Americanized versions of "ethnic" dishes. Many of the dishes are still very meat- and dairy-centric, and short on fresh fruits and vegetables. Some recipes, like this one, seem straight out of 1956. The idea that traditional ingredients should be replaced with "healthy" variations, for instance always replacing white rice with brown rice or, more recently cauliflower rice, continues. Many nutritionists also push the Mediterranean Diet as the healthiest in the world, when in fact it is very similar to other traditional diets around the world where people have access to plenty of unsaturated fats, fruits and vegetables, whole grains, lean meats, etc. Even the name - the "Mediterranean Diet," implies the diets of everyone living along the Mediterranean. So why does "Mediterranean" always mean Italian and Greek food, and never Persian, Egyptian, or Tunisian food? (Hint: the answer is racism). Old ideas about nutrition, including emphasis on low-fat foods, "meat and three" style recipes, replacement ingredients (usually poor cauliflower), and artificial sweeteners for diabetics, seem hard to shake for many people. Doctors receive very little training in nutrition and hospital food is horrific, as I saw when my father-in-law was hospitalized for several weeks in 2019. As a diabetic with problems swallowing, pancakes with sugar-free syrup, sugar-free gelatin and pudding, and not much else were their solution to his needs. The modern field of nutritionists is also overwhelmingly White, and racism persists, even towards trained nutritionists of color, much less communities of color struggling with health issues caused by generational trauma, food deserts, poverty, and overwork. Our modern food system has huge structural issues that continue to today. Why is the USDA, which is in charge of promoting agriculture at home and abroad, in charge of federal nutrition programs? Commodity food programs turn vulnerable people into handy props for industrial agriculture and the economy, rather than actually helping vulnerable people. Federal crop subsidies, insurance, and rules assigns way more value to commodity crops than fruits and vegetables. This government support also makes it easy and cheap for food processors to create ultra-processed, shelf-stable, calorie-dense foods for very little money - often for less than the crops cost to produce. This makes it far cheaper for people to eat ultra-processed foods than fresh fruits and vegetables. The federal government also gives money to agriculture promotion organizations that use federal funds to influence American consumers through advertising (remember the "Got Milk?" or "The Incredible, Edible Egg" marketing? That was your taxpayer dollars at work), regardless of whether or not the foods are actually good for Americans. Nutrition science as a field has a serious study replication problem, and an even more serious communications problem. Although scientists themselves usually do not make outrageous claims about their findings, the fact that food is such an essential part of everyday life, and the fact that so many Americans are unsure of what is "healthy" and what isn't, means that the media often capitalizes on new studies to make over-simplified announcements to drive viewership. Key TakeawaysNutrition science IS a science, and new discoveries are being made everyday. But the field as a whole needs to recognize and address the flawed scientific studies and methods of the past, including their racism - conscious or unconscious. Nutrition scientists are expanding their research into the many variables that challenge the research of the Progressive Era, including gut health, environmental factors, and even genetics. But human research is expensive, and test subjects rarely diverse. Nutrition science has a particularly bad study replication problem. If the government wants to get serious about nutrition, it needs to invest in new research with diverse subjects beyond the flawed one-size-fits-all rhetoric. The field of nutrition - including scientists, medical professionals, public health officials, and dieticians - need to get serious about addressing racism in the field. Both their own personal biases, as well as broader institutional and cultural ones. Anyone who is promoting "healthy" foods needs to think long and hard about who their audience is, how they're communicating, and what foods they're branding as "unhealthy" and why. We also need to address the systemic issues in our food system, including agriculture, food processing, subsidies, and more. In particular, the government agencies in charge of nutrition advice and food assistance need to think long and hard about the role of the federal government in promoting human health and what the priorities REALLY are - human health? or the economy? There is no "one size fits all" recommendation for human health. Ever. Especially not when it comes to food. Because nutrition guidelines have problems not just with racism, but also with ableism and economics. Not everyone can digest "healthy" foods, either due to medical issues or medication. Not everyone can get adequate exercise, due to physical, mental, or even economic issues. And I would argue that most Americans are not able to afford the quality and quantity of food they need to be "healthy" by government standards. And that's wrong. Like with human health, there are no easy solutions to these problems. But recognizing that there is a problem is the first step on the path to fixing them. Further ReadingMany of these were cited in the text of the article above, but they are organized here for clarity. I have organized them based on the topics listed above. (note: any books listed below are linked as part of the Amazon Affiliate program - any purchases made from those links will help support The Food Historian's free public articles like this one). EARLY NUTRITION SCIENCE

A HISTORY OF BODY MASS INDEX (BMI)

THE HISTORY OF THE CALORIE

MAKING "AMERICAN" FOOD

MILK - THE PERFECT FOOD

NUTRITION GUIDELINES HISTORY

COMMODITIES AND NUTRITION

ISSUES THAT PERSIST

The Food Historian blog is supported by patrons on Patreon! Patrons help keep blog posts like this one free and available to the public. Join us for awesome members-only content like free digitized cookbooks from my personal collection, e-newsletter, and even snail mail from time to time! Don't like Patreon? Leave a tip!

1 Comment

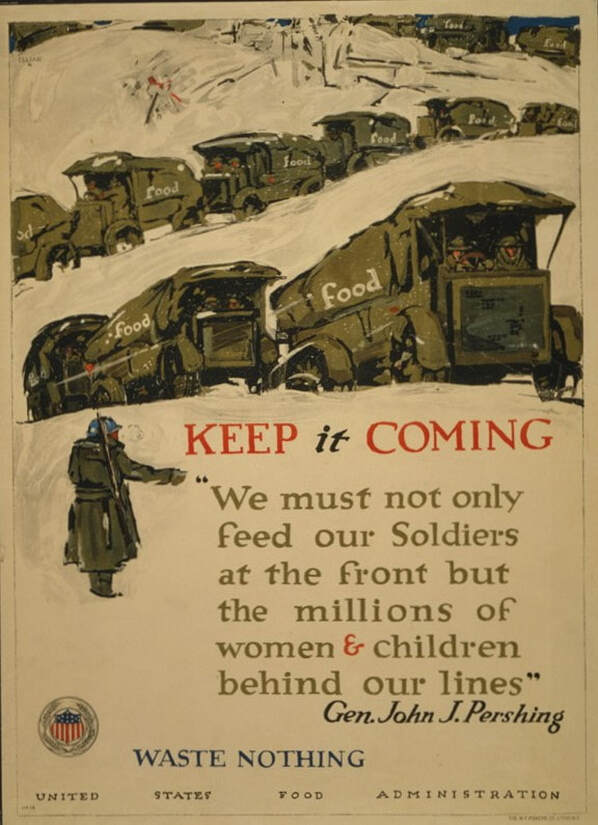

This poster features a long string of Army green military trucks labeled "Food" snaking through snow-covered hills, directed by a soldier. It reads "Keep it Coming" and features a quote by Gen. John J. Pershing - "We must not only feed our Soldiers at the front but the millions of women & children behind our lines." Underneath reads, "WASTE NOTHING" with the seal and title of the United States Food Administration. Almost certainly printed in the winter of 1917-18, the poster was designed by artist George Illian. "Keep it Coming" was apparently Illian's first poster for the war effort. He went on to design several others for the United States Food Administration, but none as striking as this one. Sadly, I was unable to dig up any information on Illian other than he was a member of the Society of Illustrators and that he did some commercial art after the war. He died in 1932, but I have not been able to find an obituary. The imagery from the poster would not have been unfamiliar to ordinary Americans who had been following the news. By the fall of 1917, American soldiers were in the fields of Europe, led by General John Joseph "Black Jack" Pershing. After three years of brutal war, France and Britain welcomed the Americans, led by Pershing with open arms in June of 1917, but it was not until October of that year that the main bulk of the American Expeditionary Forces would arrive in France. Although the United States had officially entered the war in April of 1917, military personnel numbered under 200,000, and military supply and tactics were largely stuck in the 19th century. It took months of stop-and-start mobilization to train American troops (sometimes with wooden rifles) and get them overseas (on borrowed ships). The winter of 1917-18 was one of the worst in recent memory during the First World War. On December 29, 1917, the New York Times reported "Cold Snap Over Entire East," reporting temperatures in upstate New York as low as 20 degrees below zero. New York Harbor froze, railroads were backed up across the Eastern seaboard, and Europe was engulfed in snow and freezing rain. The weather conditions meant that nearly all of the supplies for Europe and for major Eastern cities were completely backed up. On December 30th, the New York Times reported coal shortages in New England and New York, blaming railroad backups and the requisitioning of civilian ships and tugs for the war effort. The railroad backups resulted in the nationalizing of the railroad system under William McAdoo. Illian's poster reflects the winter conditions on the front lines, too. Although the true horrors of trench warefare were often glossed over by the press, by 1917 many Americans were hearing from their "boys" overseas first hand. Marching in the abnormally frigid cold and torrential rains of the winter of 1917-18 in Europe was familiar to most of the soldiers. While the Eastern U.S. was brought nearly to a standstill by railroad blockages, coal shortages, and frozen ports, Britain, France, and Spain also experienced unusually cold temperatures, high snowfalls, and blocked railroads in December, 1917 and January, 1918. Like many of the propaganda posters of the First World War, "Keep it Coming" exhorts ordinary Americans not only to conserve food for American soldiers overseas, but also to help feed women and children in Allied nations. "Waste Nothing" was part of a campaign to reduce food waste and free up additional supplies to send overseas. American supplies of wheat in particular were low in 1917, and only by reducing consumption could food stocks be freed up for shipment overseas until farmers could increase production. The idea of personal self-sacrifice was part of a larger movement during the war to fund the war effort (through the sale of liberty bonds) and to "do your bit" to help the war effort. By using the wintry backdrop, Illian brought home the message that while Americans might be suffering from cold at home, things were worse in Europe, and American soldiers were doing all they could to help end the war and alleviate hunger and hardship among people who had already suffered four long years of war. 1917-18 would be the only winter warfare most Americans would see in Europe - the war officially ended in November of 1918 - but while millions of soldiers were sent home after Armistice, many Americans would remain in Europe until the summer of 1919, part of the demobilization efforts and cleanup (including burial duty) after the war. The Food Historian blog is supported by patrons on Patreon! Patrons help keep blog posts like this one free and available to the public. Join us for awesome members-only content like free digitized cookbooks from my personal collection, e-newsletter, and even snail mail from time to time! Don't like Patreon? Join with an annual membership below, or just leave a tip! Tip Jar

$1.00 - $20.00

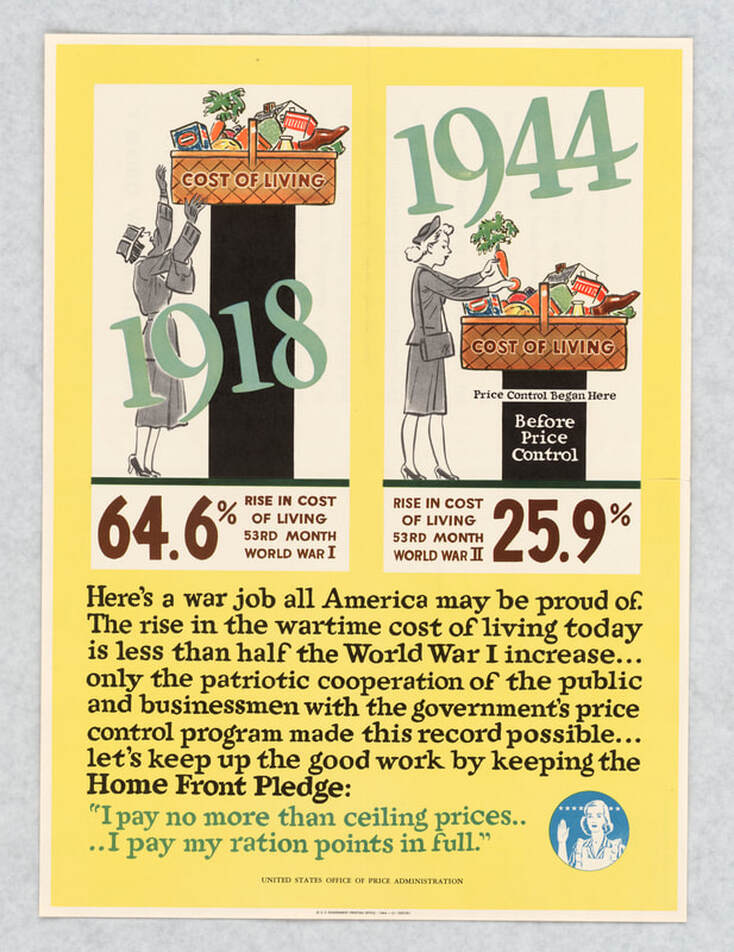

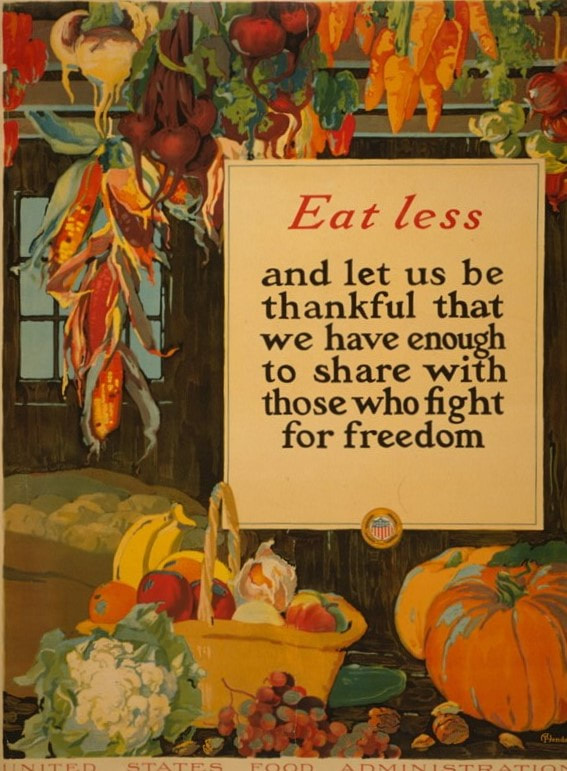

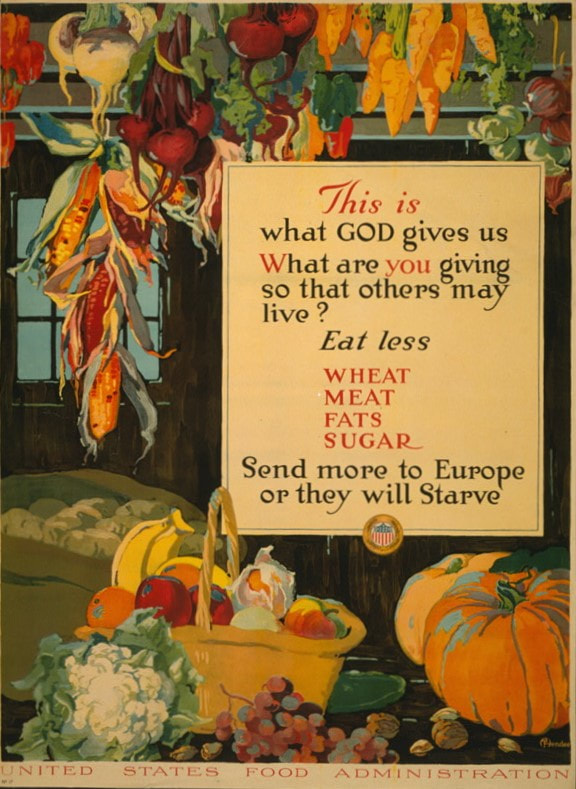

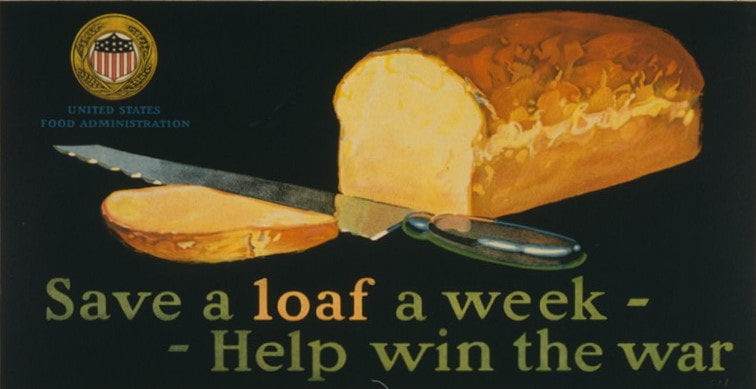

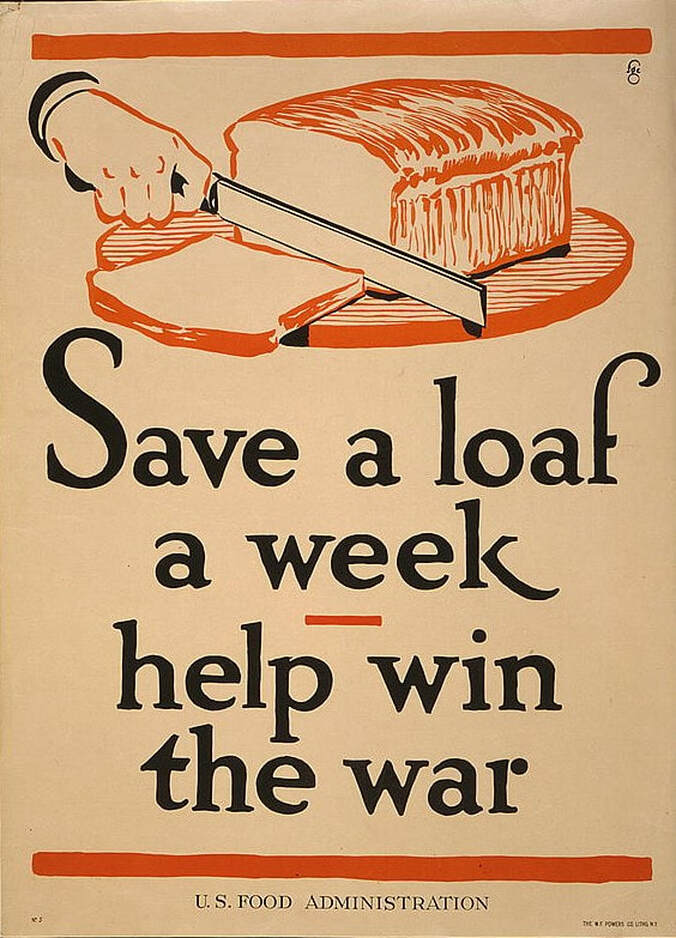

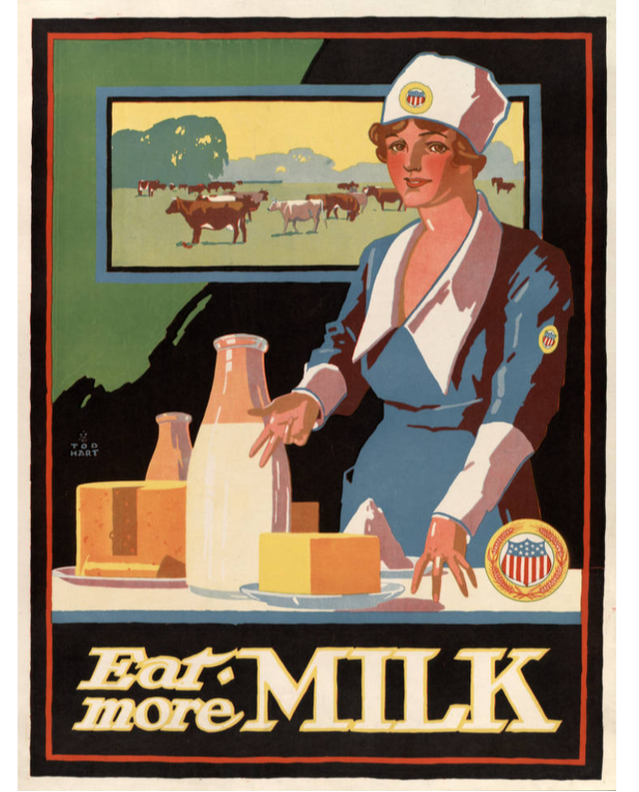

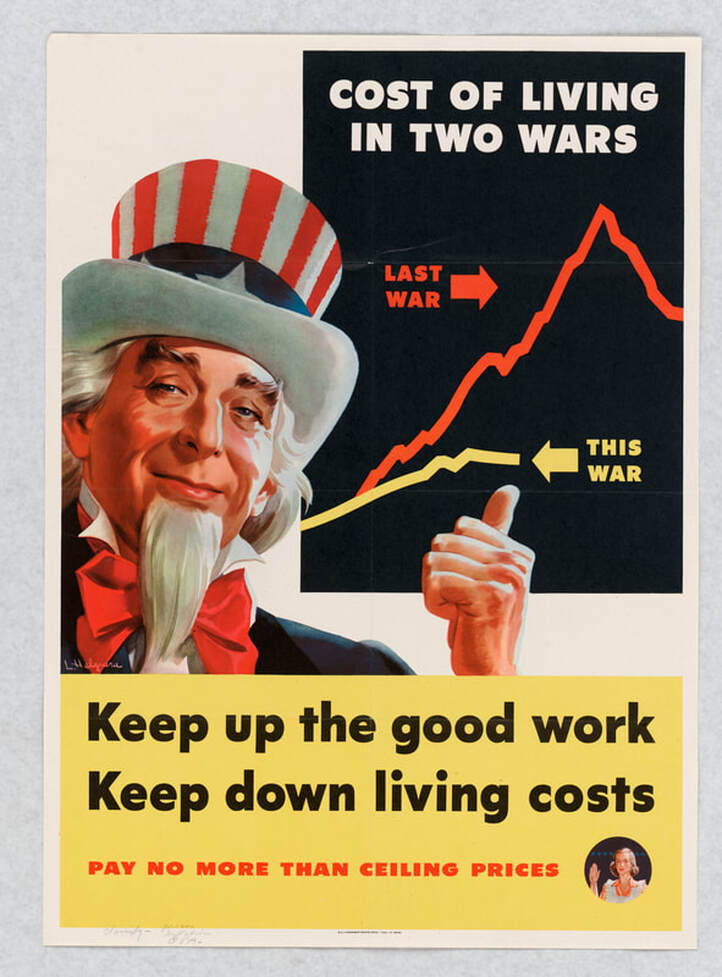

Like what you read, watch, or hear? Wanna help support The Food Historian, but don't want to commit to a monthly thing, or sign up for Patreon? Then you're in luck! You can leave a tip! This one-time (non-tax-deductible) donation helps keep The Food Historian going and pays for things like webhosting, Zoom, additions to the cookbook library, and helps compensate Sarah for her time and energy in helping everyone learn more about the history of food, agriculture, cooking, and more. Thank you! Tomorrow is Thanksgiving in the United States, so I thought it would be apt to visit the matching pair of posters. It's not clear if they were meant to be displayed together or not, but the artist, A. Hendee, clearly recycled one beautiful image for another version. In both images, produce is stored in an attic. Red peppers, turnips, corn, beets, carrots, and what looks like red onions hang from the rafters. A sack of potatoes, a basket of fruit (including bananas!), cauliflower, grapes, a lone cucumber, a few nuts, and two fat pumpkins sit on the wooden floor. In the first image, a white placard with the United States Food Administration seal on the bottom admonishes "Eat less, and let us be thankful that we have enough to share with those who fight for freedom." Much of the propaganda around food and the First World War admonished self-restraint when it came to food. Although the phrase "eat less" has had some controversy in the modern era, in the 1910s it was far less about ideal bodyweight (although that played a role) and far more about reducing waste. As the poor wheat harvests in 1916 and 1917 did not allow for normal consumption levels AND exporting to the Allies, most of the rhetoric in 1917 and 1918 was focused on reducing waste, refocusing American eating habits on other types of food, and reducing consumption in general. For instance, while messages of "eat less" were common, so was the Gospel of the Clean Plate, which exhorted Americans not to waste food. In the second poster, the message reads, "This is what God gives us - what are you giving so that others may live? Eat less wheat, meat, fats, sugar - send more to Europe or they will starve." The Library of Congress tentatively dates this poster as 1917, but that could be simply because it is WWI-related. However, this message is far more explicit than the first, so it may very well have been the first printed. We have specific foods to avoid, and the spectre of starvation in Europe is raised. But we also have a more explicit reference to the image itself, "This is what God gives us" is referencing the abundant produce. Which, you'll notice, does not include hams or bushels of wheat or other foods you might find in a 19th century attic. The focus is entirely on produce, which is on purpose, as eating more fruits and vegetables instead of more calorie-dense and shelf stable foods like wheat, meat, fats, and sugar. Potatoes in particular were touted as an alternative to bread. Although the Library of Congress has no other posters attributed to "A. Hendee," I've managed to track her - yes her! - down, thanks to a clue post from a UK museum that found her full maiden name. Alice Julia Hendee, later Alice Hendee Price, was born in 1889, possibly in Kansas as she attended the Kansas City Art Institute before moving to New York to attend the National Academy of Design and the New York School of Fine and Applied Arts. In 1917 she was listed in a city directory as living on the Upper West Side, and in 1923 she moved to Bronxville, NY in Westchester County. At some point she married architect and illustrator Chester A. Price. Alice made the local news quite frequently for her art, and by 1950 was teaching classes to area women. She died in Westchester county in 1969 and outlived her husband, but in typical mid-century fashion, not his name. Like many of the illustrators and artists who created iconic propaganda posters for the First World War, Alice Hendee Price's recorded history makes no mention of her wartime work. But the stunning images remain. And this Thanksgiving, although we no longer need to curtail our eating habits for wartime, the message of being thankful for what we have and sharing with others is a timeless one. Have a lovely Thanksgiving, everyone, whether you're celebrating with family or friends, and I hope you can enjoy all the bounty of the season. The Food Historian blog is supported by patrons on Patreon! Patrons help keep blog posts like this one free and available to the public. Join us for awesome members-only content like free digitized cookbooks from my personal collection, e-newsletter, and even snail mail from time to time! Don't like Patreon? Join with an annual membership below, or just leave a tip! It's finally cold enough to bake in my neck of the woods. I made New York Gingerbread for a Halloween party this past weekend and it was delicious. You may be thinking of finally tackling the yeast bread you never made during the COVID shutdown. But like the early days of the pandemic when the shelves were empty of flour, during the First World War, wheat was in short supply. Poor wheat harvests in the fall of 1915 and 1916 meant that when the United States joined the war in April of 1917, there was not enough wheat to feed both the citizens of the United States and the military and their Allies. So the United States Food Administration embarked on a campaign to get Americans to voluntarily give up some of their favorite foods - including white bread made from wheat flour. By the 1910s white bread was ingrained (no pun intended) in the American diet and culture. It held onto its associations with wealth and refinement long after white flour became affordable and abundant. In addition, the conventional wisdom of nutrition science at the time elevated carbohydrates as a valuable source of energy. Which meant that both white bread and refined white sugar were considered healthful and important sources of the newly-discovered calories. Getting people to give up their favorite breakfast, side dish, and anytime (including midnight) snack was not going to be easy. This pair of propaganda posters produced by the USFA illustrate the same primary point - that if everyone gave up a little, the compound effect would be enormous. You'll note they don't focus on getting Americans to stop eating white bread - just to consume less. The implication of both posters is that be reducing consumption by as little as one slice a day would really add up. Other campaigns, including Wheatless Wednesday (partner to Meatless Monday), told Americans to replace the slice of bread customary with each meal with a baked potato, especially after the potato surplus in 1918. Alternative grains, especially corn, were also touted as substitutes for white bread. Restaurants were banned from bringing rolls or bread to the table before customers ordered their meal (sugar bowls were out, too). By 1918, one way the Food Administration tried to control the consumption of white bread without instituting mandatory rationing was to require Americans to purchase two pounds of alternative grains or flour for every one pound of wheat flour. However, although other campaigns emphasized corn as a valuable substitute, there's evidence that people may have just discarded the additional flours they were forced to purchase. Despite these challenges, the fact that the United States was able to feed their military, and the Allies, on the same 1916 wheat harvest suggests that Americans did reduce their wheat consumption in 1917. Today we know that refined white flour is a little too efficient a carbohydrate, and that the vitamins and minerals in whole grain flour, and the added fiber, are generally much better for human health. For wheatless recipes from the First World War, check out this article from North Carolina State University Libraries. The Food Historian blog is supported by patrons on Patreon! Patrons help keep blog posts like this one free and available to the public. Join us for awesome members-only content like free digitized cookbooks from my personal collection, e-newsletter, and even snail mail from time to time! Don't like Patreon? Join with an annual membership below, or just leave a tip! This beautiful propaganda poster from the First World War is the result of a controversy. The fresh-faced young white woman in her United States Food Administration-approved food conservation uniform and cap, gestures to a table with an enormous glass bottle of milk, a huge block of butter, a wheel of cheese, and what is either a mound of cottage cheese or some sort of milk pudding. A framed view of dairy cows in a green field floats behind her. It exhorts the reader to "Eat more MILK." But why? Throughout World War I in the United States, dairy farmers struggled. Feed prices went up, and retail prices of milk went up, but the wholesale prices that farmers got from milk dealers and dairies remained static. Despite dozens of local and state and federal inquiries, no single culprit for high milk prices was ever discovered. The result of high prices combined with government advocating for increased production and Progressive Era ideas about the importance of cow's milk in the diet, particularly for children, meant that by the spring of 1918 there was a serious milk surplus. For several years, the butter, cheese, and condensed milk industries had absorbed the milk surplus, but by the spring of 1918 they were also over capacity. The United States Food Administration, in conjunction with state governments, embarked on a campaign to try to get Americans to consume more milk, with limited success. In May of 1918, New York City hosted the National Milk and Dairy Farm Exposition at the Grand Central Palace. New York State Governor Charles Whitman opened the exposition, and United States Food Administrator Herbert Hoover also attended. Home economists praised milk-based dishes such as puddings, custards, and the use of cottage cheese and brick cheeses - hence the phrase "Eat more milk," rather than "drink," as drinking cows milk was not common among adults. Cottage cheese and brick cheese were touted as affordable meat alternatives. Despite the classic Progressive Era boosterism, including the attendance of "famous" cows at the exposition, retail milk prices remained relatively high, with seasonal dips in the spring and early summer. Federally fixed milk prices helped solve the problem short-term, but even after the war, dairy farmers were subject to a Congressional investigation to determine whether they price gouged consumers (they didn't), and the right of farmers to form co-ops was in danger of becoming illegal under anti-trust laws. Ultimately, it was falling grain prices and rising postwar demand that evened out prices, although to this day the dairy industry still struggles. Even after the war, Progressive Era ideas about the importance of cow's milk in the diet persisted, and were recycled during the Second World War. The Food Historian blog is supported by patrons on Patreon! Patrons help keep blog posts like this one free and available to the public. Join us for awesome members-only content like free digitized cookbooks from my personal collection, e-newsletter, and even snail mail from time to time! Join by June 30, 2020 and get a picnic history packet mailed to your door! Last week we talked about the High Cost of Living in the First World War. Those memories were close at hand during the Second World War. During World War I, the federal government did little to control prices at the consumer level, and rationing was voluntary. The U.S. Food Administration did control whether or not retail establishments and manufacturers complied with rationing and other rules through a complicated system of licensing and oversight, but individual consumers were technically allowed to make their own food choices. During World War II, things were different. Rationing was mandatory, even if the stamps were often confusing, and black markets definitely existed. But the creation of the Office of Price Administration froze the official prices of a whole host of goods, including food, to try to offset wartime inflation. Once again retailers were being regulated by the government, but this time the OPA relied on consumers to help report violators. By enlisting housewives to help enforce "ceiling prices" by refusing to purchase goods at that exceeded the published price lists, the OPA got a free labor source, and the housewives ensured that their retailers were not cheating them. Black women, in particular, benefitted from this practice, as discrimination meant they were subject to being cheated.  "Here's a war job all America may be proud of. The rise in wartime cost of living today is less than half the World War I increase... only the patriotic cooperation of the public and businessmen with the government's price control program made this record possible... let's keep up the good work by keeping the Home Front Pledge: "I pay no more than ceiling prices... I pay my ration points in full."" Office of Price Administration, National Archives. This pair of posters, comparing the inflation of food from WWI to WWII, was designed to prove the effectiveness of the Office of Price Administration and its price control efforts. In the first one, Uncle Sam points to a chart that compares the rise of inflation over the course of both World Wars. In the second, two bar charts on inflation are compared. In the first, labeled 1918, a (suspiciously-1930s-attired) housewife tries and fails to reach a basket of food labeled "Cost of Living" as it rises on a bar chart of 64.6% inflation. Whereas the 1944 housewife can easily reach her basket at 25.9% inflation. Interestingly, her bar chart has a white line 3/4 of the way up which reads "Price control began here." The black bar below reads "Before Price Control," implying that inflation could have been much worse without the intervention of the OPA. Both statistics are attributed to the 53rd month of the war, which seems to indicate that the inflation statistics for World War I start in 1914, not 1917, when the U.S. officially joined the war, which tracks with the cost of living increases that began long before April 7, 1917. These two posters indicate just one of the ways in which the lessons of the First World War were applied to the Second. Some lessons, however, remained hard to swallow. During WWI, the United States Food Administration, although formed by executive order in May of 1917, received no funding from Congress until August, 1917, because a number of congressmen objected to the sweeping powers and controls it gave the executive branch. In an effort to avoid a bloated post-war bureaucracy, it was quickly dismantled in early 1919, despite the fact that the cost of living rose precipitously after the war. Similar sentiments about the power of the Office of Price Administration were debated during WWII, and numerous attempts by organized retail and manufacturing organizations to weaken it started as early as 1944. The OPA was allowed to temporarily expire in 1945, and prices jumped almost instantly. It was hastily reinstated, but in a weaker form, and was fully abolished in 1947. Some price control functions for sugar, rice, and a few other products were shifted to other agencies. In her article, "'How About Some Meat?': The Office of Price Administration, Consumption Politics, and State Building from the Bottom Up, 1941-1946," historian Meg Jacobs talks about how the Office of Price Administration helped Americans determine that high standards and low cost of living was their reward, nay birthright, for surviving two World Wars and a Great Depression. Caught between empowered consumers and producers and retailers anxious to throw off the yoke of government regulation, the OPA was at the center of post-war discussions about the future of the American economy. Given today's cost of living problems, I find it fascinating to study the economics of the first half of the 20th century, and how societal reactions and government policies continue to shape today's discussions about the future of our economy - whether people realize it or not. Today, economists are studying the impact of the Great Recession and COVID-19 on our economic future, just like historians and economists in the 1920s and 1940s did when they were looking back at the two World Wars. Further Reading

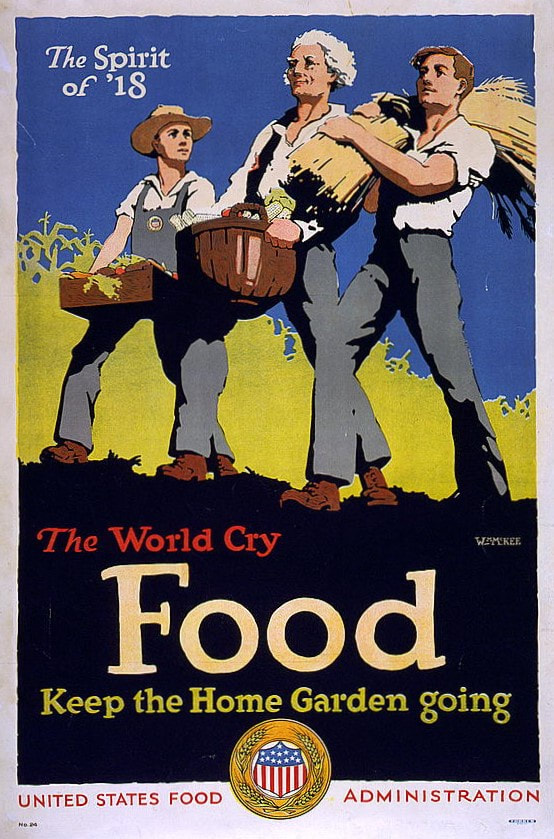

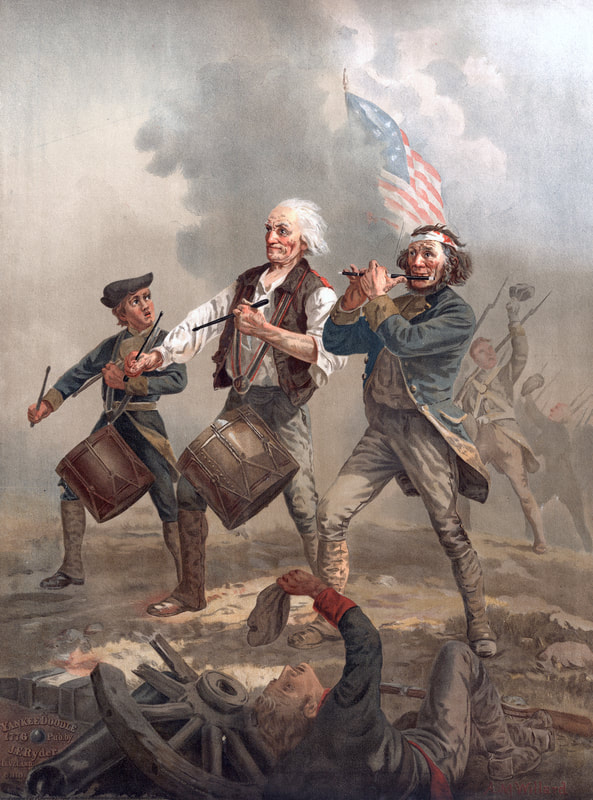

If you enjoyed this blog post, consider supporting The Food Historian on Patreon! Patrons get special perks, including members-only content, access to digitized cookbooks, and occasional snail mail. Patrons also help keep this blog free for everyone. Join today! Last week we featured a propaganda poster from World War II that hearkened back to Valley Forge. This week we're featuring a propaganda poster from World War I that also hearkened back to the American Revolution - "The Spirit of '18." During the First World War, the United States Food Administration, along with private organizations like the National War Garden Commission, encouraged ordinary Americans to plant war gardens (later termed "victory gardens," a name that stuck when revived in the Second World War). War gardens were needed to free up commercial agricultural products to send overseas to American Allies, many of whom were suffering after three years of privations, and to feed American troops abroad. In particular, the 1915 and 1916 wheat harvests had been poor, leaving little to export. In order to free up domestic supplies for shipment overseas, the government encouraged Americans to grow and preserve more of their own food, alleviating the domestic strain on food supplies and freeing up commercial foods for government use. This was a tactic which was revisited during World War II. In this poster, a young boy wearing overalls bearing the US Food Administration seal, carries a wooden crate of vegetables. He looks on at the older man in the center, whose haircut brings to mind George Washington, and who carries a larger basket of produce. At the far right, a young man carries a sheaf of wheat on his shoulder. All are marching in step, a stylized cornfield and a brilliant blue sky behind them. "Spirit of '18," the poster reads at the top. Below, it says, "The World Cry Food - Keep the Home Garden Going," with the United States Food Administration title and seal at the bottom. Although it doesn't seem like it on the surface, this poster references the American Revolution. It is based on a very famous image which would have been familiar to Americans at the time. Painted by Archibald MacNeil Willard in 1875 for the 1876 Centennial Exposition in Philadelphia, the painting which became known as "Spirit of '76" was revealed to little critical acclaim, but great popularity among ordinary people. Willard reproduced it several times. The original was enormous - eight feet by ten feet. The above image of "Spirit of '76" is a chromolithograph produced by J. E. Ryder for the Centennial Exposition and sold to tourists as a souvenir (see the original here). This helped its popularity greatly, as it was widely panned by critics as too dark. The painting illustrates two drummers - one elderly and one a young boy, accompanied by a wounded man playing fife - behind them flies the American flag (or perhaps the Cowpens battle flag) and more troops waving their tricorn hats - evoking perhaps that the resolute fife and drum corps are leading a column of relief troops, bringing victory to the battle that wounded the artilleryman in the foreground with his cannon on the ground, its carriage broken. You can see how closely William McKee mirrored the work of Archibald Willard - the three figures in both images are nearly identical - a young boy, an elderly man, and a young man, although in the World War I poster the young man is considerably younger and more Adonis-looking than Willard's figure. The figures represent the three generations - youth, adulthood, and old age, as well as the breadth of men participating in the American Revolution and World War I. During the Revolutionary War, musicians were usually boys too young and men too old to enlist as regular soldiers. Old men and young boys were also "drafted" during the First World War for home front duties, including gardening and farm labor. In both images, the figures are marching forward, bringing victory behind them. Archibald Willard died on October 11, 1918, exactly one month short of the end of World War I. So it is possible he saw his work replicated in this poster. "Spirit of '76" was his most popular and enduring work, but it did not bring fame or fortune. For other Americans who saw the "Spirit of '18" poster, it surely would have instantly brought to mind the "Spirit of '76," and the sacrifices and courage of the American Revolution, inspiring similar levels of patriotism and sacrifice by Progressive Era Americans during the First World War to "do their bit" and contribute to the war effort through war gardens. The Food Historian blog is supported by patrons on Patreon! Patrons help keep blog posts like this one free and available to the public. Join us for awesome members-only content like free digitized cookbooks from my personal collection, e-newsletter, and even snail mail from time to time! |

AuthorSarah Wassberg Johnson has an MA in Public History from the University at Albany and studies early 20th century food history. Archives

July 2024

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed