|

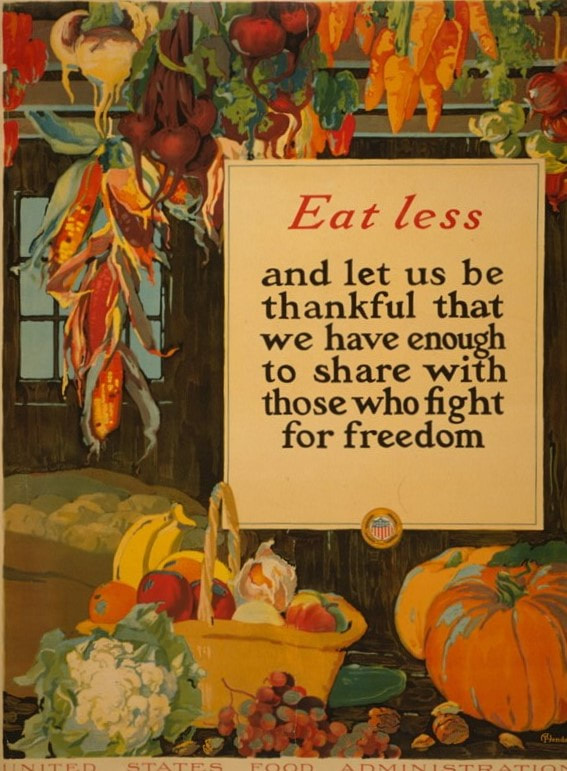

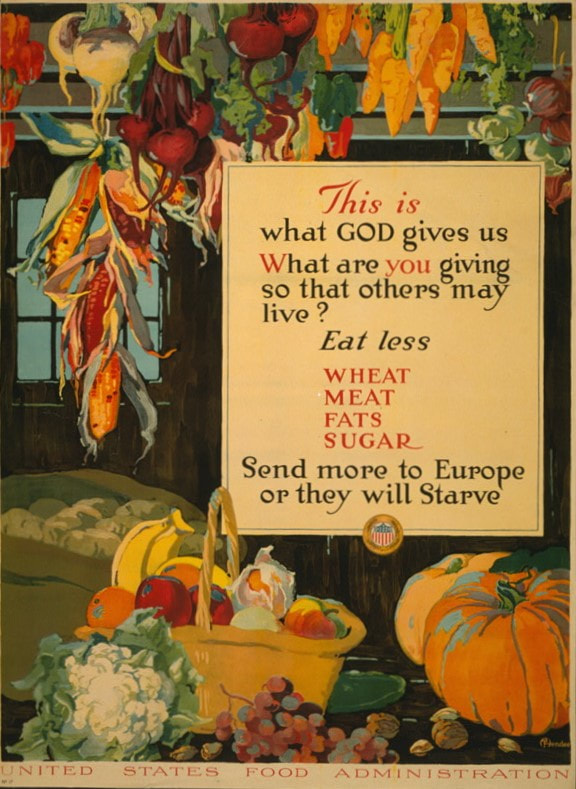

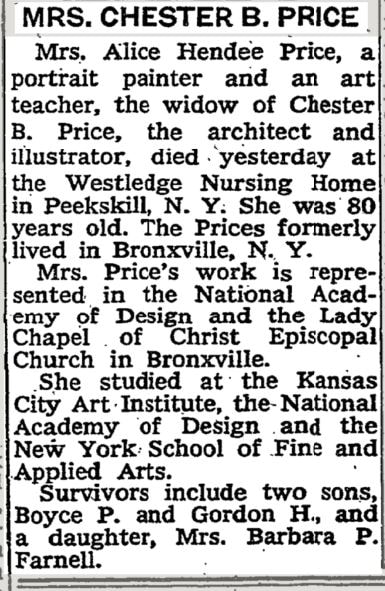

Tomorrow is Thanksgiving in the United States, so I thought it would be apt to visit the matching pair of posters. It's not clear if they were meant to be displayed together or not, but the artist, A. Hendee, clearly recycled one beautiful image for another version. In both images, produce is stored in an attic. Red peppers, turnips, corn, beets, carrots, and what looks like red onions hang from the rafters. A sack of potatoes, a basket of fruit (including bananas!), cauliflower, grapes, a lone cucumber, a few nuts, and two fat pumpkins sit on the wooden floor. In the first image, a white placard with the United States Food Administration seal on the bottom admonishes "Eat less, and let us be thankful that we have enough to share with those who fight for freedom." Much of the propaganda around food and the First World War admonished self-restraint when it came to food. Although the phrase "eat less" has had some controversy in the modern era, in the 1910s it was far less about ideal bodyweight (although that played a role) and far more about reducing waste. As the poor wheat harvests in 1916 and 1917 did not allow for normal consumption levels AND exporting to the Allies, most of the rhetoric in 1917 and 1918 was focused on reducing waste, refocusing American eating habits on other types of food, and reducing consumption in general. For instance, while messages of "eat less" were common, so was the Gospel of the Clean Plate, which exhorted Americans not to waste food. In the second poster, the message reads, "This is what God gives us - what are you giving so that others may live? Eat less wheat, meat, fats, sugar - send more to Europe or they will starve." The Library of Congress tentatively dates this poster as 1917, but that could be simply because it is WWI-related. However, this message is far more explicit than the first, so it may very well have been the first printed. We have specific foods to avoid, and the spectre of starvation in Europe is raised. But we also have a more explicit reference to the image itself, "This is what God gives us" is referencing the abundant produce. Which, you'll notice, does not include hams or bushels of wheat or other foods you might find in a 19th century attic. The focus is entirely on produce, which is on purpose, as eating more fruits and vegetables instead of more calorie-dense and shelf stable foods like wheat, meat, fats, and sugar. Potatoes in particular were touted as an alternative to bread. Although the Library of Congress has no other posters attributed to "A. Hendee," I've managed to track her - yes her! - down, thanks to a clue post from a UK museum that found her full maiden name. Alice Julia Hendee, later Alice Hendee Price, was born in 1889, possibly in Kansas as she attended the Kansas City Art Institute before moving to New York to attend the National Academy of Design and the New York School of Fine and Applied Arts. In 1917 she was listed in a city directory as living on the Upper West Side, and in 1923 she moved to Bronxville, NY in Westchester County. At some point she married architect and illustrator Chester A. Price. Alice made the local news quite frequently for her art, and by 1950 was teaching classes to area women. She died in Westchester county in 1969 and outlived her husband, but in typical mid-century fashion, not his name. Like many of the illustrators and artists who created iconic propaganda posters for the First World War, Alice Hendee Price's recorded history makes no mention of her wartime work. But the stunning images remain. And this Thanksgiving, although we no longer need to curtail our eating habits for wartime, the message of being thankful for what we have and sharing with others is a timeless one. Have a lovely Thanksgiving, everyone, whether you're celebrating with family or friends, and I hope you can enjoy all the bounty of the season. The Food Historian blog is supported by patrons on Patreon! Patrons help keep blog posts like this one free and available to the public. Join us for awesome members-only content like free digitized cookbooks from my personal collection, e-newsletter, and even snail mail from time to time! Don't like Patreon? Join with an annual membership below, or just leave a tip!

0 Comments

Your comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

AuthorSarah Wassberg Johnson has an MA in Public History from the University at Albany and studies early 20th century food history. Archives

July 2024

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed