|

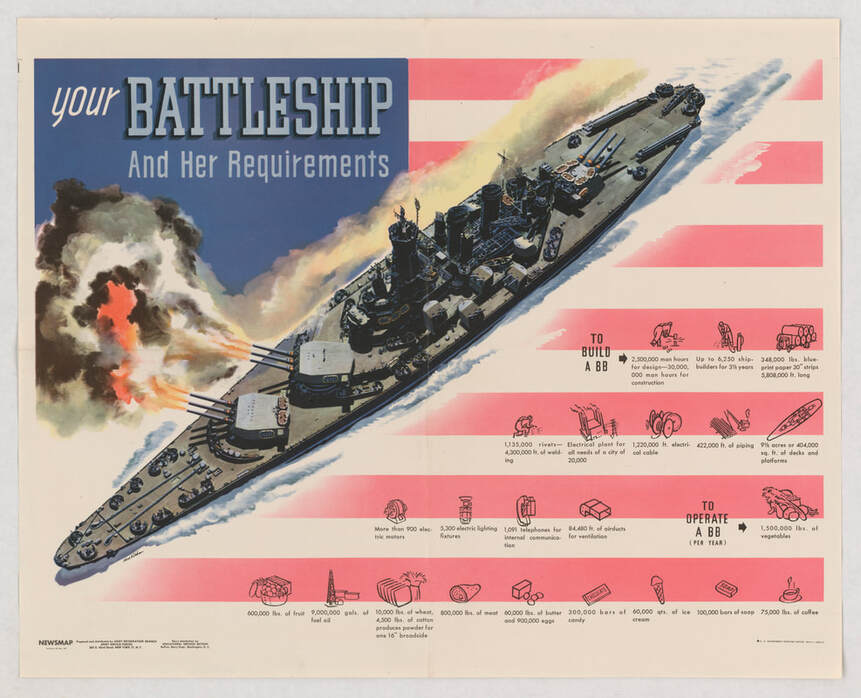

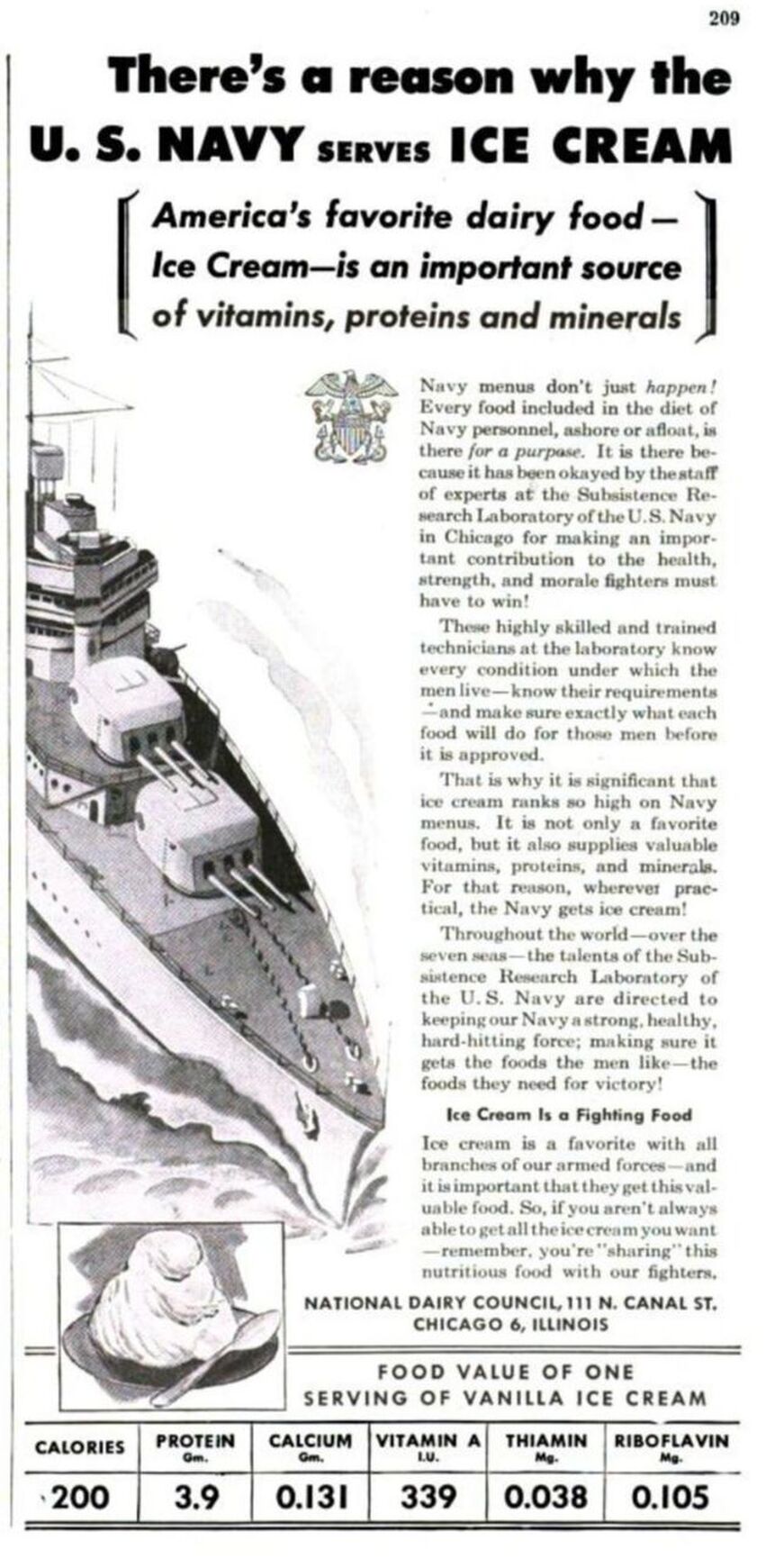

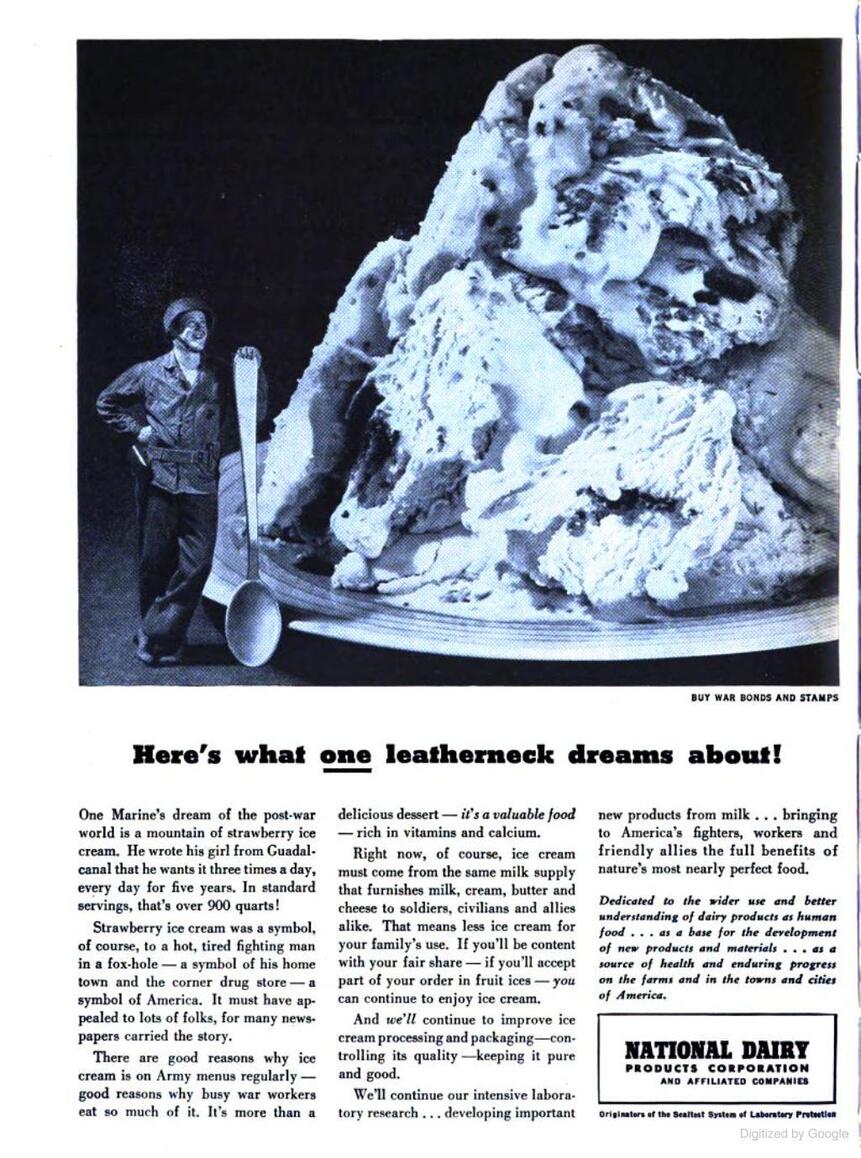

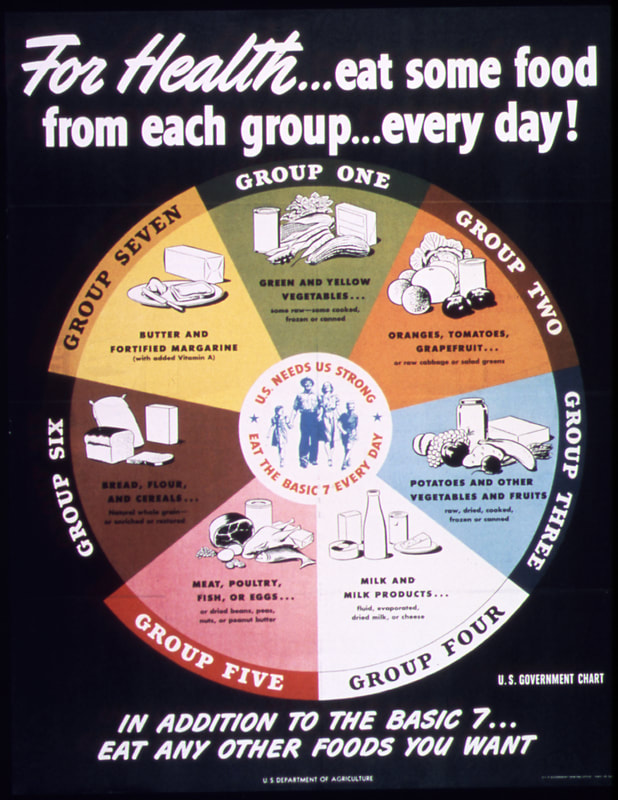

Last World War Wednesday, we looked at the use of ice cream in the U.S. Navy during the First World War, especially aboard hospital ships. Now it's time for a reprise! By the Second World War, ice cream was firmly entrenched aboard Naval vessels. So much so, that battleships and aircraft carriers were actually outfitted with ice cream machinery, and by the end of the war the Navy was training sailors in their uses through special classes. The above propaganda poster, courtesy the National Archives, outlines all of the requirements to build a battleship. "Your Battleship and Her Requirements" may have been targeted toward factory workers, but I think it is more likely this poster was designed to impress upon ordinary Americans the extraordinary amount of materials and supplies needed to keep a battleship in fighting trim. What I found particularly interesting, was that among the supplies listed, alongside fruits and vegetables and meat and even candy, was 60,000 quarts of ice cream! Smaller vessels, such as destroyer escorts and submarines, did not have the space for their own ice cream making machinery, although they did have freezers. In fact, it became common for destroyer escorts and PT boats to rescue downed pilots (the aircraft carries were too big for the job) and "ransom" them for ice cream. Last week a brand new food podcast debuted for American Public Television called "If This Food Could Talk," and I'm so pleased to say I was featured in the first episode, "Frozen in Time: Ice Cream and America's Past." I had a blast doing the research for that episode's interview, which has inspired these two recent World War Wednesday posts. Have a listen if you want to learn more about ice cream in American history, and especially the story of ice cream in the Navy. But while I was doing the research, I kept running across references to ice cream as a health food! The National Dairy Council really leaned into the notion of ice cream and the armed forces. This advertisement reads, "There's a reason why the U.S. Navy serves Ice Cream. America's favorite dairy food - Ice Cream - is an important source of vitamins, proteins and minerals." The ad goes on: "Navy menus don't just happen! Every food included in the diet of Navy personnel, ashore or afloat, is there for a purpose. It is there because it has been okayed by the staff of experts at the Subsistence Research Laboratory of the U.S. Navy in Chicago for making an important contribution to the health, strength, and morale fighters must have to win! "These highly skilled and trained technicians at the laboratory know every condition under which the men live - know their requirements - and make sure exactly what each food will do for those men before it is approved. "That is why it is significant that ice cream ranks so high on Navy menus. It is not only a favorite food, but it also supplies valuable vitamins, proteins, and minerals. For that reason, wherever practical, the Navy gets ice cream! "Throughout the world - over the seven seas - the talents of the Subsistence Research Laboratory of the U.S. Navy are directed to keeping our Navy a strong, healthy, hard-hitting force; making sure it gets the foods the men like - the foods they need for victory! "Ice Cream Is a Fighting Food "Ice cream is a favorite with all branches of our armed forces - and it is important that they get this valuable food. So fi you aren't always able to get all the ice cream you want - remember, you're 'sharing' this nutritious food with our fighters." The National Dairy Council might be just a SMIDGE biased in this regard, but certainly the federal government ranked milk, and by extension milk products, very highly in terms of nutrition during the Second World War, notably as part of the Basic 7 nutrition recommendations. This was almost certainly a holdover from the Progressive Era's take on milk as the "perfect food" - combining proteins, carbohydrates, and fats all in one. We see this in another advertisement, this time by the National Dairy Products Corporation. The National Dairy Council is an industry-funded research and marketing organization. But the National Dairy Products Corporation would later become Kraft Foods. "Here's what one leatherneck dreams about! "One Marine's dream of the post-war world is a mountain of strawberry ice cream. He wrote his girl from Guadalcanal that he wants it three times a day, every day for five years. In standard servings, that's over 900 quarts! "Strawberry ice cream was a symbol, of course, to a hot, tired fighting man in a fox-hole - a symbol of his home town and the corner drug store - a symbol of America. It must have appealed to lots of folks, for many newspapers carried the story. "There are good reasons why ice cream is on Army menus regularly - good reason why busy war workers eat so much of it. It is more than a delicious dessert - it's a valuable food - rich in vitamins and calcium. "Right now, of course, ice cream must come from the same milk supply that furnishes milk, cream, butter and cheese to soldiers, civilians and allies alike. That means less ice cream for your family's use. If you'll be content with your fair share - if you'll accept part of your order in fruit ices - you can continue to enjoy ice cream. "And we'll continue to improve ice cream processing and packaging - controlling its quality - keeping it pure and good. "We'll continue our intensive laboratory research... developing important new products from milk... bringing to America's fighters, workers and friendly allies the full benefits of nature's most nearly perfect food." Here you can see the "perfect food" rhetoric in action! And interestingly, this one touts the role of ice cream in the Army as well. In my opinion ice cream, for all the rhetoric about nutrition, had far more to do with morale than anything else. But there is some truth to the idea that as a dessert it was superior to cake or pie. For one thing, ice cream does have some protein, in addition to a decent amount of fat. Full fat dairy is generally proven to be more filling and satisfying and protein and fat slow down the absorption of sugar directly into the bloodstream, making the "energy-giving" properties of carbohydrates longer-lasting and less likely to make you crash (unlike cake and cookies). That being said, viewing ice cream as a health food is questionable today. But in the period, the discoveries of vitamins and minerals like calcium were cutting-edge, and any food containing those essential nutrients was considered good for you. Ice cream also fit neatly into ideas (unconscious or otherwise) of White supremacy and American (i.e. Anglo-Saxon) culture. As the National Dairy Products Corporation marketing team wrote, ice cream was "a symbol of America." When combined with soda fountains (the wholesome, if sugary, alternative to saloons and beer halls), ice cream seemed to represent the best of America - slim, good-looking, young, White America, that is. Today, ice cream's modern accessibility has given us ice cream alternatives aplenty, especially for folks who can't consume dairy. Ice cream's ubiquity has also meant some of its luster has faded. But at a time of extreme stress - the violence of the theater of war, the privations of home front rationing, the push to mobilize for total war, the fear of invasion - ice cream provided a moment of bliss in the midst of uncertainty. Ice cream is still an essential tradition aboard Naval vessels today. When you're miles from home for months at a time, anything that seems like a treat gives morale a boost. It's still a treasured treat in our household, whether homemade or store bought (if you find yourself in upstate New York - do yourself a favor and seek out Stewart's Shops. They have the best commercial ice cream around). What does ice cream mean to you? The Food Historian blog is supported by patrons on Patreon! Patrons help keep blog posts like this one free and available to the public. Join us for awesome members-only content like free digitized cookbooks from my personal collection, e-newsletter, and even snail mail from time to time! A special patrons-only post is coming tomorrow with more on ice cream in World War II - this time featuring Elsie the Cow! Join now for as little as $1/month.

Don't like Patreon? Leave a tip!

1 Comment

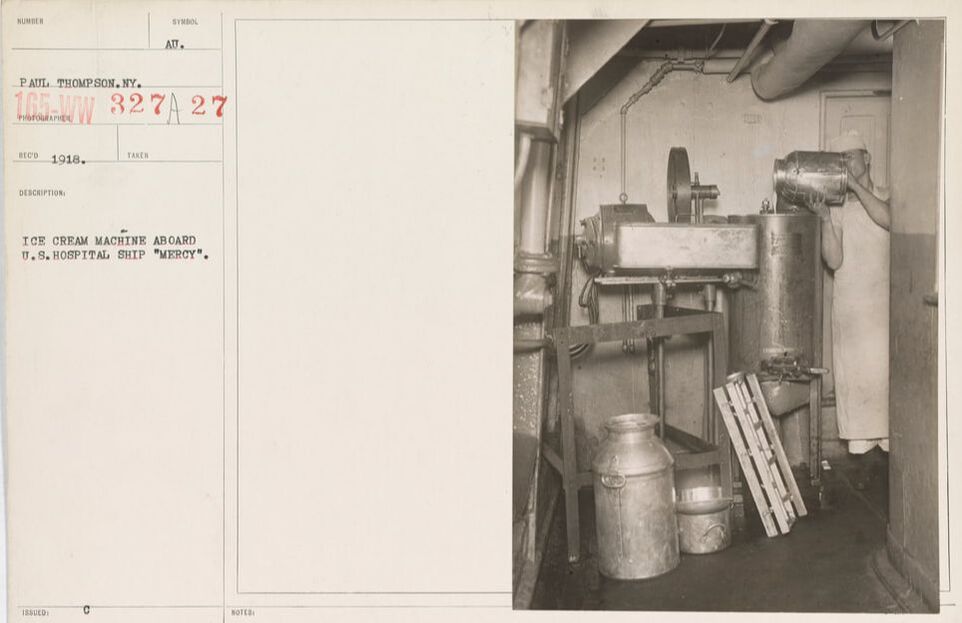

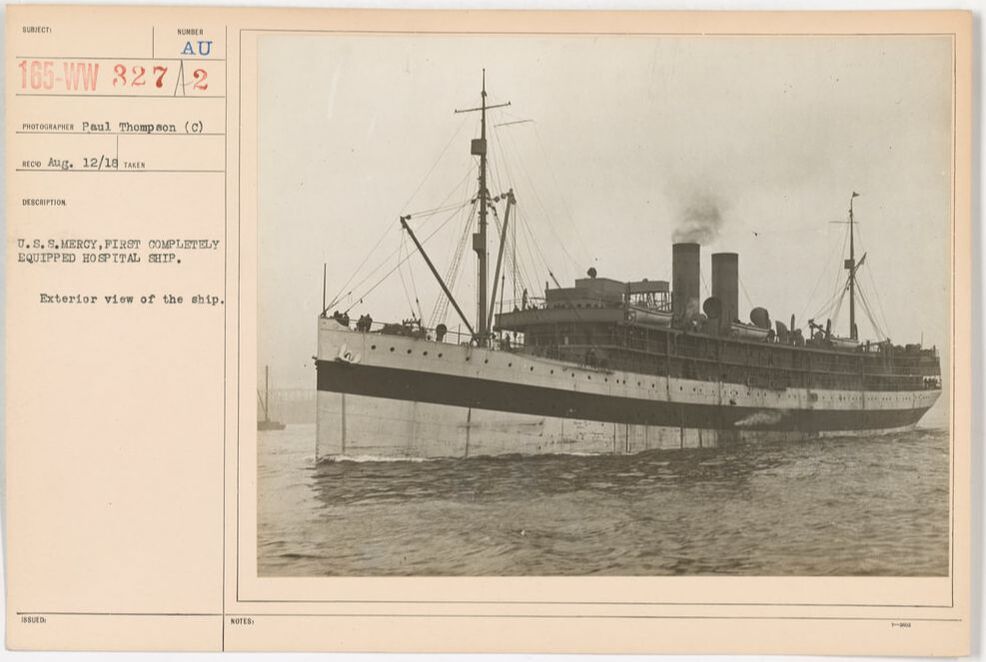

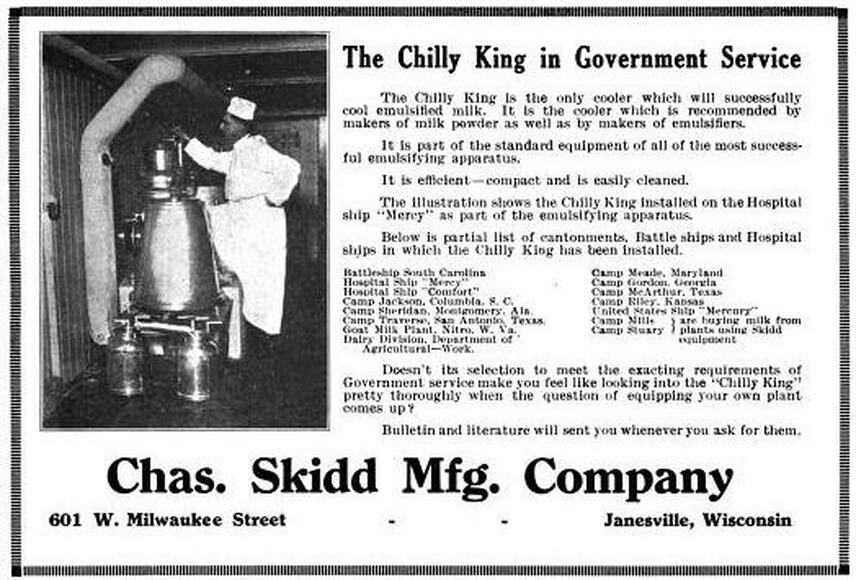

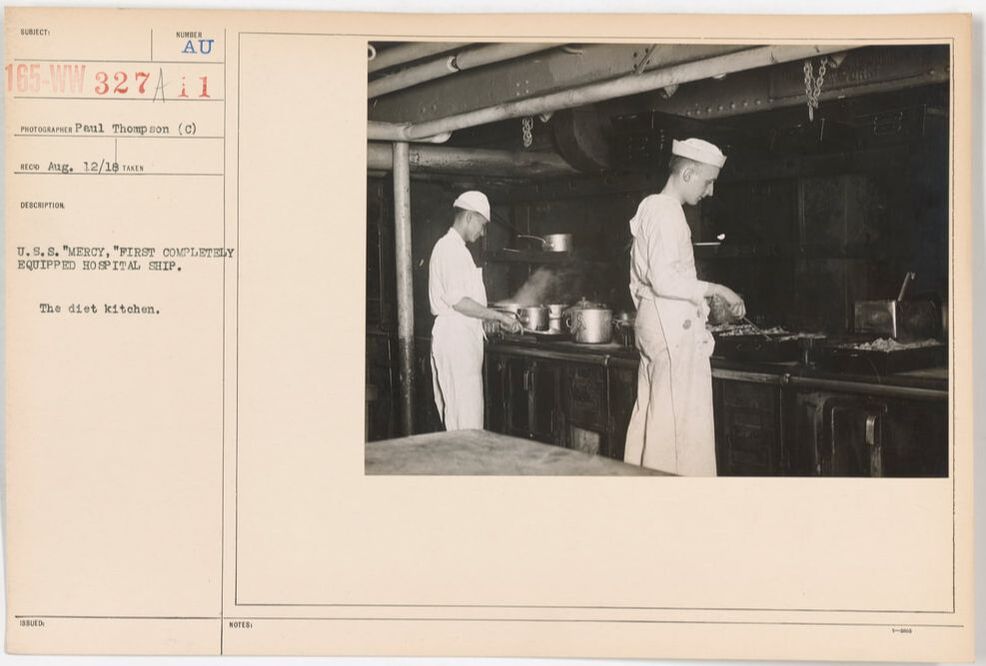

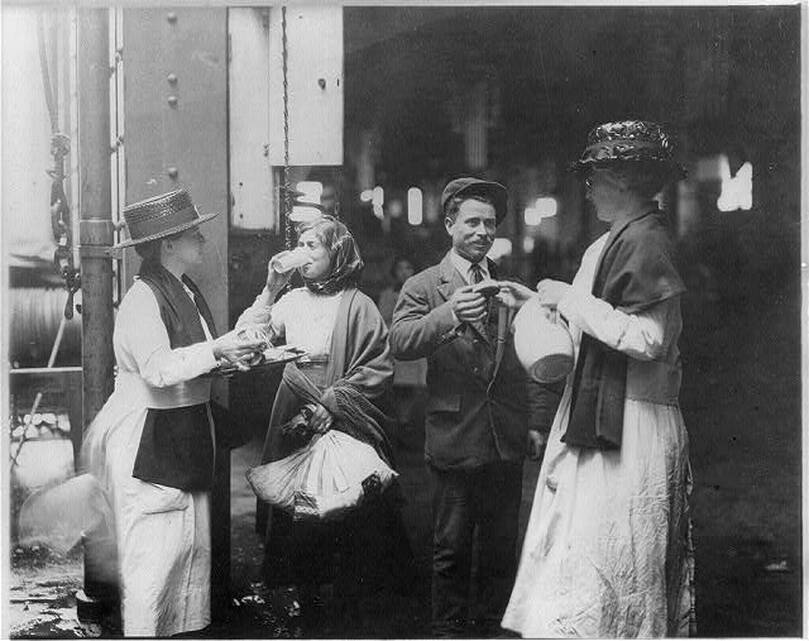

I've been getting a lot of calls for information about ice cream lately, and that has sent me down a rabbit hole. I did a whole talk on the history of ice cream last year (you can watch the filmed version here), but while I knew ice cream was a big tradition in naval history, I didn't know the connection to the First World War. I don't usually cover the history of military consumption of food during the World Wars, but this topic was just too much fun to resist. Ice cream wasn't always the Navy's treat of choice. For over a hundred years rum was the preferred ration by many sailors. But in the late 19th century the Temperance movement began to have increasing power over society. By 1919 we had a Constitutional Amendment (the 19th - often known just as "Prohibition"). But the armed forces went dry much earlier. In particular, on July 1, 1914, the U.S. Navy went alcohol-free. At the same time, naval vessels were being stocked with ice cream. In the May, 1913 issue of The Ice Cream Trade Journal, an article entitled "Sailors Like Ice Cream" explained that the Navy had recently ordered 350,000 pounds of evaporated milk - ostensibly for all sorts of cooking and baking, but ice cream was high on the list. You may wonder why hospital ships in the First World War were manufacturing ice cream on board? Well, it involves multiple factors. First is that ice cream was a product of milk; during the Progressive Era, milk was considered the "perfect food" as it contained fats, proteins, and carbohydrates all in one (supposedly) easily digestible package. Although many people are lactose intolerant, the White Anglo-Saxon dominance of American culture at the time prized milk. Ice cream rode into nutritional value on the coattails of milk. During this time period, dairy-based products like puddings, custards, milk and cream on cooked cereals or with toast, and ice cream were all considered nutritious foods for people who had been injured or ill. Along with foods like beef tea, eggs, and stewed fruits, these made up the bulk of recommended hospital foods from the late 19th century to World War I. Ice cream shows up quite frequently in early reports of the Surgeon General to the U.S. Navy. In his 1918 report to the Secretary of the Navy, ice cream appears to cause more problems than it solves. Notably, the use of ice cream produced commercially results in several instances of crew sickness, including simple illnesses like strep throat, alongside more serious ones like a diphtheria outbreak in Newport in 1917, which was traced to ice cream produced off-station. Fears of the spread of typhoid from places like restaurants, soda fountains, and ice cream shops led to "antityphoid inoculations" at naval shipyards. In Chicago, "All soft-drink and ice-cream stands have promised to give sailors individual service in the form of paper cups and dishes. To make this more effective, it is believed that an order should be issued prohibiting men from accepting any other kind of service." The Surgeon General also recommended inspection of offsite dairies and bottling works for milk, ice cream, and soft drinks to ensure proper sterilization of equipment and pasteurization of dairy products, as well as inoculation of employees against typhoid and smallpox. But ice cream was also noted as essential not only on the existing hospital ship USS Solace, but also on two new hospital ships fitted out since the declaration of war in 1917 - the USS Mercy and the USS Comfort. These ships included a cold storage plant and a refrigerating machine that could "produce, under favorable circumstances, a ton of ice or more a day." The ships also had distilling plants, able to convert seawater to fresh water, up to 20,000 gallons per day. In addition to describing the medical wards, crew facilities, laundry, and kitchen, the report noted: The most valuable adjunct in the treatment and feeding of the sick is the milk emulsifier, popularly known as the "mechanical cow." The milk produced from this machine is made from a combination of unsalted butter and skimmed milk powder and can be made with any proportion of butter fat and proteins desired. This machine will produce 15 gallons of cold, pasteurized milk in 45 minutes. The electric ice cream machine, controlled by one man, makes 10 gallons at a time and is supplemented by small freezers for preparing individual diets for the sick. According to the October, 1918 issue of The Milk Dealer, the "mechanical cow" had been displayed as part of the exhibits at the National Dairy Show in Columbus, Ohio in the fall of 1917. They noted: The "Mechanical Cow" Becoming Famous. Few people who saw the combination exhibit of Merrell-Soule Co. and the DeLaval Separator Co., last October, in Columbus, would have believed that within a year from that beginning the use of the Emulsor in combining Skimmed Milk Powder, unsalted butter and water would be taken up by Army, Navy, City Administrations, etc. throughout the United States. Such is the fact, however. The Mechanical Cow is now producing milk and cream on the U.S.S. Comfort and U.S.S. Mercy, the two splendid hospital ships of the Navy. An installation on board the U.S.S. South Carolina is kept working continuously to supply the demands of her crew. Mechanical Cows are filling the needs of milk at the base hospitals and several camps and one large machine is being operated by one of the city departments of New York. Health officers, physicians, milk experts and authorities on infant feeding all unanimously agree that milk and cream made by means of the "Mechanical Cow" is superior in every way to the average milk supply. This advertisement for "The Chilly King," a cooling machine that was part of the "Mechanical Cow" system on ships like the U.S.S. Mercy (a photograph of the machinery on board featured in the ad) also names a number of naval ships and military camps which use it, including:

By enabling ships and camps to use shelf-stable skimmed milk powder and unsalted butter, which keeps a very long time in cold storage, "mechanical cows" allowed for an ample supply of milk made in sanitary conditions. For naval ships, this was especially important when crews were away from shore for long periods of time. Ice cream also helped patients recover from illness (or so medical professionals at the time believed) but it also helped a great deal with morale. The professionalization of ship operations via the installation of state-of-the-art equipment was a hallmark of the First World War, but the U.S.'s late involvement in the war hamstrung most shipbuilding operations. Indeed, the construction of a new hospital ship in 1916 was actually shelved in favor of retrofitting existing ships like those that were transformed into the U.S.S. Comfort and U.S.S. Mercy, which had initially served as the sister passenger steamboats S.S. Havana and S.S. Saratoga, respectively. Part of the Ward Line, these very fast steamships ran the New York City to Havana, Cuba route but were requisitioned in 1917 first as troop transports, and later as hospital ships. The U.S.S. Mercy spent time as a home for the homeless during the Great Depression before she was scrapped in the 1930s, and the U.S.S. Comfort went back to civilian passenger transport for the Ward line under her old name, the S.S. Havana, before being pressed into service again in World War II, this time as a troop transport once again. The names USS Comfort and USS Mercy would be revived in World War II and a third pair of hospital ships bearing those names are still in operation today. Although ice cream is no longer considered central to the recuperation of the sick and wounded, it is still served on American naval vessels around the world. Ice cream would play an even more important role in the Navy during the Second World War. But that's a tale for another World War Wednesday! The Food Historian blog is supported by patrons on Patreon! Patrons help keep blog posts like this one free and available to the public. Join us for awesome members-only content like free digitized cookbooks from my personal collection, e-newsletter, and even snail mail from time to time! Don't like Patreon? Leave a tip!

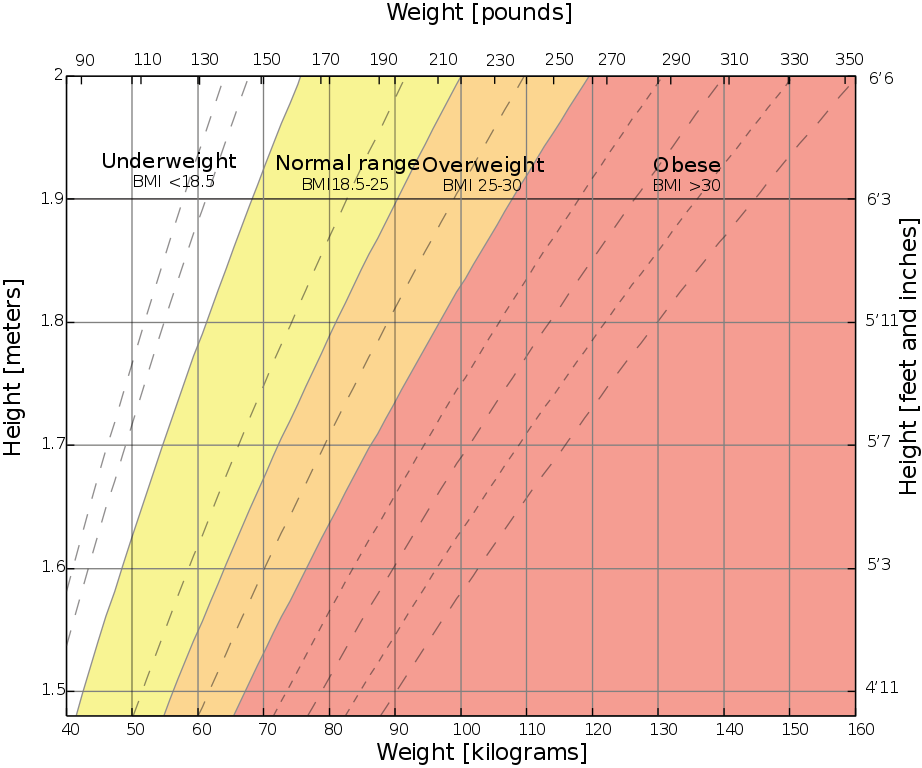

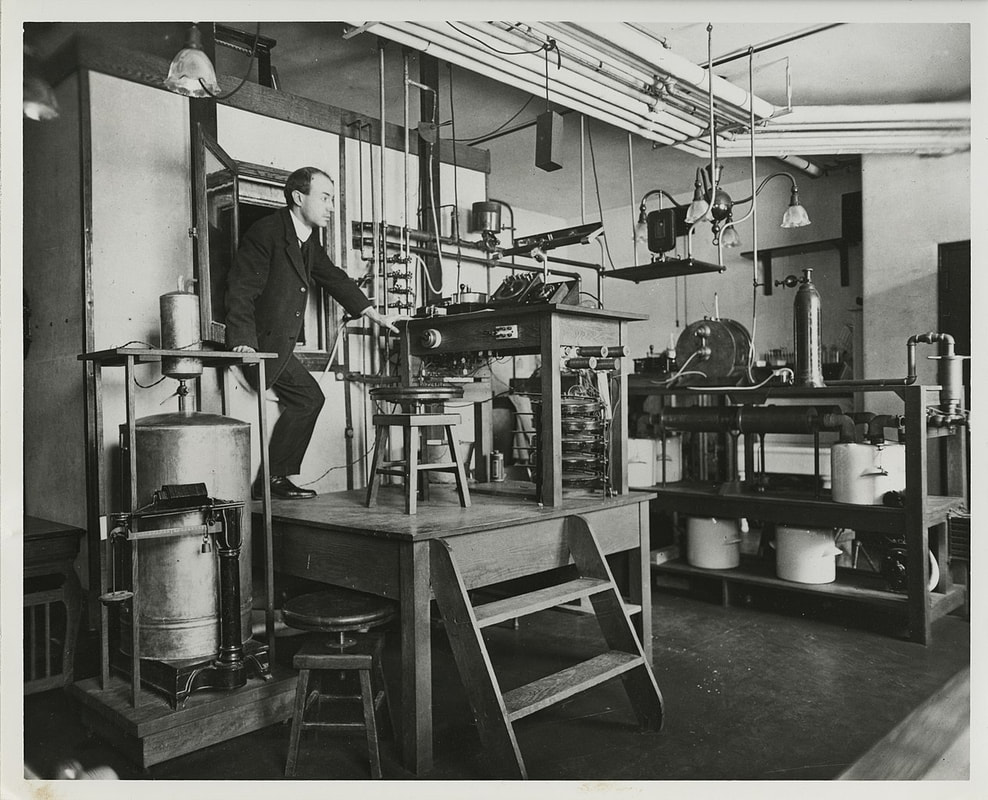

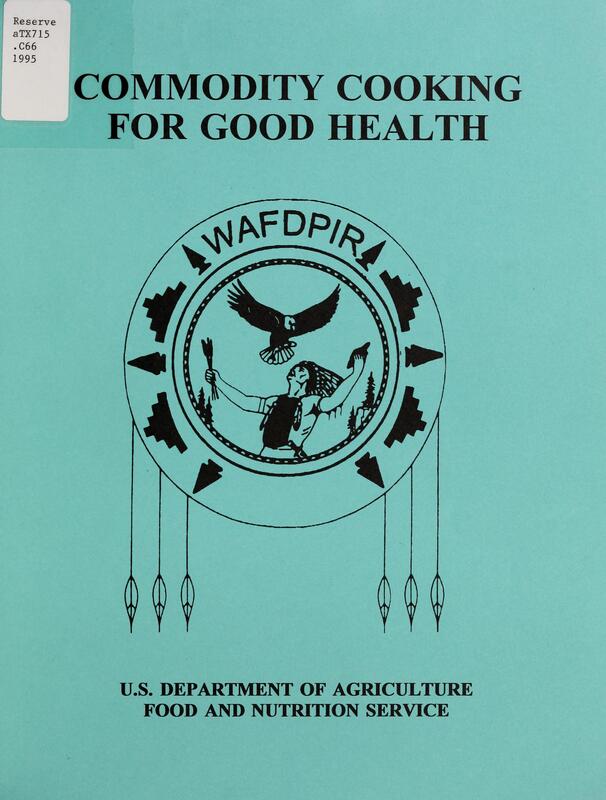

The short answer? At least in the United States? Yes. Let's look at the history and the reasons why. I post a lot of propaganda posters for World War Wednesday, and although it is implied, I don't point out often enough that they are just that - propaganda. They are designed to alter peoples' behavioral patterns using a combination of persuasion, authority, peer pressure, and unrealistic portrayals of culture and society. In the last several months of sharing propaganda posters on social media for World War Wednesday, I've gotten a couple of comments on how much they reflect an exclusively White perspective. Although White Anglo-Saxon Protestant culture was the dominant culture in the United States at the time, it was certainly not the only culture. And its dominance was the result of White supremacy and racism. This is reflected in the nutritional guidelines and nutrition science research of the time. The First World War takes place during the Progressive Era under a president who re-segregated federal workplaces that had been integrated since Reconstruction. It was also a time when eugenics was in full swing, and the burgeoning field of nutrition science was using racism as justifications for everything from encouraging assimilation among immigrant groups by decrying their foodways and promoting White Anglo-Saxon Protestant foodways like "traditional" New England and British foods to encouraging "better babies" to save the "White race" from destruction. Nutrition science research with human subjects used almost exclusively adult White men of middle- and upper-middle class backgrounds - usually in college. Certain foods, like cow's milk, were promoted heavily as health food. Notions of purity and cleanliness also influenced negative attitudes about immigrants, African Americans, and rural Americans. During World War II, Progressive-Era-trained nutritionists and nutrition scientists helped usher in a stereotypically New England idea of what "American" food looked like, helping "kill" already declining regional foodways. Nutrition research, bolstered by War Department funds, helped discover and isolate multiple vitamins during this time period. It's also when the first government nutrition guidelines came out - the Basic 7. Throughout both wars, the propaganda was focused almost exclusively on White, middle- and upper-middle-class Americans. Immigrants and African Americans were the target of some campaigns for changing household habits, usually under the guise of assimilation. African Americans were also the target of agricultural propaganda during WWII. Although there was plenty of overt racism during this time period, including lynching, race massacres, segregation, Jim Crow laws, and more, most of the racism in nutrition, nutrition science, and home economics came in two distinct types - White supremacy (that is, the belief that White Anglo-Saxon Protestant values were superior to every other ethnicity, race, and culture) and unconscious bias. So let's look at some of the foundations of modern nutrition science through these lenses. Early Nutrition ScienceNutrition Science as a field is quite young, especially when compared to other sciences. The first nutrients to be isolated were fats, carbohydrates, and proteins. Fats were the easiest to determine, since fat is visible in animal products and separates easily in liquids like dairy products and plant extracts. The term "protein" was coined in the 1830s. Carbohydrates began to be individually named in the early 19th century, although that term was not coined until the 1860s. Almost immediately, as part of nearly any early nutrition research, was the question of what foods could be substituted "economically" for other foods to feed the poor. This period of nutrition science research coordinated with the Enlightenment and other pushes to discover, through experimentation, the mechanics of the universe. As such, it was largely limited to highly educated, White European men (although even Wikipedia notes criticism of such a Euro-centric approach). As American colleges and universities, especially those driven by the Hatch Act of 1877, expanded into more practical subjects like agriculture, food and nutrition research improved. American scientists were concerned more with practical applications, rather than searching for knowledge for knowledge's sake. They wanted to study plant and animal genetics and nutrition to apply that information on farms. And the study of human nutrition was not only to understand how humans metabolized foods, but also to apply those findings to human health and the economy. But their research was influenced by their own personal biases, conscious and unconscious. The History of Body Mass Index (BMI)Body Mass Index, or BMI, is a result of that same early 19th century time period. It was invented by Belgian mathematician Lambert Adolphe Jacques Quetelet in the 1830s and '40s specifically as a "hack" for determining obesity levels across wide swaths of population, not for individuals. Quetelet was a trained astronomist - the one field where statistical analysis was prevalent. Quetelet used statistics as a research tool, publishing in 1835 a book called Sur l'homme et le développement de ses facultés, ou Essai de physique sociale, the English translation of which is usually called A Treatise on Man and the Development of His Faculties. In it, he discusses the use of statistics to determine averages for humanity (mainly, White European men). BMI became part of that statistical analysis. Quetelet named the index after himself - it wasn't until 1972 that researcher Ancel Keys coined the term "Body Mass Index," and as he did so he complained that it was no better or worse than any other relative weight index. Quetelet's work went on to influence several famous people, including Francis Galton, a proponent of social Darwinism and scientific racism who coined the term "eugenics," and Florence Nightingale, who met him in person. As a tool for measuring populations, BMI isn't bad. It can look at statistical height and weight data and give a general idea of the overall health of population. But when it is used as a tool to measure the health of individuals, it becomes extremely flawed and even dangerous. Quetelet had to fudge the math to make the index work, even with broad populations. And his work was based on White European males who he considered "average" and "ideal." Quetelet was not a nutrition scientist or a doctor - this "ideal" was purely subjective, not scientific. Despite numerous calls to abandon its use, the medical community continues to use BMI as a measure of individual health. Because it is a statistical tool not based on actual measures of health, BMI places people with different body types in overweight and obese categories, even if they have relatively low body fat. It can also tell thin people they are healthy, even when other measurements (activity level, nutrition, eating disorders, etc.) are signaling an unhealthy lifestyle. In addition, fatphobia in the medical community (which is also based on outdated ideas, which we'll get to) has vilified subcutaneous fat, which has less impact on overall health and can even improve lifespans. Visceral fat, or the abdominal fat that surrounds your organs, can be more damaging in excess, which is why some scientists and physicians advocate for switching to waist ratio measurements. So how is this racist? Because it was based on White European male averages, it often punishes women and people of color whose genetics do not conform to Quetelet's ideal. For instance, people with higher muscle mass can often be placed in the "overweight" or even "obese" category, simply because BMI uses an overall weight measure and assumes a percentage of it is fat. Tall people and people with broader than "ideal" builds are also not accurately measured. The History of the CalorieAlthough more and more people are moving away from measuring calories as a health indicator, for over 100 years they have reigned as the primary measure of food intake efficiency by nutritionists, doctors, and dieters alike. The calorie is a unit of heat measurement that was originally used to describe the efficiency of steam engines. When Wilbur Olin Atwater began his research into how the human body metabolizes food and produces energy, he used the calorie to measure his findings. His research subjects were the White male students at Wesleyan University, where he was professor. Atwater's research helped popularize the idea of the calorie in broader society, and it became essential learning for nutrition scientists and home economists in the burgeoning field - one of the few scientific avenues of study open to women. Atwater's research helped spur more human trials, usually "Diet Squads" of young middle- and upper-middle-class White men. At the time, many papers and even cookbooks were written about how the working poor could maximize their food budgets for effective nutrition. Socialists and working class unionists alike feared that by calculating the exact number of calories a working man needed to survive, home economists were helping keep working class wages down, by showing that people could live on little or inexpensive food. Calculating the calories of mixed-food dishes like casseroles, stews, pilafs, etc. was deemed too difficult, so "meat and three" meals were emphasized by home economists. Making "American" FoodEfforts to Americanize and assimilate immigrants went into full swing in the late 19th and early 20th centuries as increasing numbers of "undesirable" immigrants from Ireland, southern Italy, Greece, the Middle East, China, Eastern Europe (especially Jews), Russia, etc. poured into American cities. Settlement workers and home economists alike tried to Americanize with varying degrees of sensitivity. Some were outright racist, adopting a eugenics mindset, believing and perpetuating racist ideas about criminology, intelligence, sanitation, and health. Others took a more tempered approach, trying to convince immigrants to give up the few things that reminded them of home - especially food. These often engaged in the not-so-subtle art of substitution. For instance, suggesting that because Italian olive oil and butter were expensive, they should be substituted with margarine. Pasta was also expensive and considered to be of dubious nutritional value - oatmeal and bread were "better." A select few realized that immigrant foodways were often nutritionally equivalent or even superior to the typical American diet. But even they often engaged in the types of advice that suggested substituting familiar ingredients with unfamiliar ones. Old ideas about digestion also influenced food advice. Pickled vegetables, spicy foods, and garlic were all incredibly suspect and scorned - all hallmarks of immigrant foodways and pushcart operators in major American cities. The "American" diet advocated by home economists was highly influenced by Anglo-Saxon and New England ideals - beef, butter, white bread, potatoes, whole cow's milk, and refined white sugar were the nutritional superstars of this cuisine. Cooking foods separately with few sauces (except white sauce) was also a hallmark - the "meat and three" that came to dominate most of the 20th century's food advice. Rooted in English foodways, it was easy for other Northern European immigrants to adopt. Although French haute cuisine was increasingly fashionable from the Gilded Age on, it was considered far out of reach of most Americans. French-style sauces used by middle- and lower-class cooks were often deemed suspect - supposedly disguising spoiled meat. Post-Civil War, Yankee New England foodways were promoted as "American" in an attempt to both define American foodways (which reflected the incredibly diverse ecosystems of the United States and its diverse populations) and to unite the country after the Civil War. Sarah Josepha Hale's promotion of Thanksgiving into a national holiday was a big part of the push to define "American" as White and Anglo-Saxon. This push to "Americanize" foodways also neatly ignores or vilifies Indigenous, Asian-American, and African American foodways. "Soul food," "Chinese," and "Mexican" are derided as unhealthy junk food. In fact, both were built on foundations of fresh, seasonal fruits, vegetables, and whole grains. But as people were removed from land and access to land, the they adapted foodways to reflect what was available and what White society valued - meat, dairy, refined flour, etc. Asian food in particular was adapted to suit White palates. We won't even get into the term "ethnic food" and how it implies that anything branded as such isn't "American" (e.g. White). Divorcing foodways from their originators is also hugely problematic. American food has a big cultural appropriation problem, especially when it comes to "Mexican" and "Asian" foods. As late as the mid-2000s, the USDA website had a recipe for "Oriental salad," although it has since disappeared. Instead, we get "Asian Mango Chicken Wraps," and the ingredients of mango, Napa cabbage, and peanut butter are apparently what make this dish "Asian," rather than any reflection of actual foodways from countries in Asia. Milk - The Perfect FoodCombining both nutrition research of the 19th century and also ideas about purity and sanitation, whole cow's milk was deemed by nutrition scientists and home economists to be "the perfect food" - as it contained proteins, fats, and carbohydrates, all in one package. Despite issues with sanitation throughout the 19th century (milk wasn't regularly pasteurized until the 1920s), milk became a hallmark of nutrition advice throughout the Progressive Era - advice which continues to this day. Throughout the history of nutritional guidelines in the U.S., milk and dairy products have remained a mainstay. But the preponderance of advice about dairy completely ignores that wide swaths of the population are lactose intolerant, and/or did not historically consume dairy the way Europeans did. Indigenous Americans, and many people of African and Asian descent historically did not consume cow's milk and their bodies often do not process it well. This fact has been capitalized upon by both historic and modern racists, as milk as become a symbol of the alt-right. Even today, the USDA nutrition guidelines continue to recommend at least three servings of dairy per day, an amount that can cause long term health problems in communities that do not historically consume large amounts of dairy. Nutrition Guidelines HistoryBecause Anglo-centric foodways were considered uniquely "American" and also the most wholesome, this style of food persisted in government nutritional guidelines. Government-issued food recommendations and recipes began to be released during the First World War and continued during the Great Depression and World War II. These guidelines and advice generally reinforced the dominant White culture as the most desirable. Vitamins were first discovered as part of research into the causes of what would come to be understood as vitamin deficiencies. Scurvy (Vitamin C deficiency), rickets (Vitamin D deficiency), beriberi (Vitamin B1 or thiamine deficiency), and pellagra (Vitamin B2 or niacin deficiency) plagued people around the world in the 19th and early 20th centuries. Vitamin C was the first to be isolated in 1914. The rest followed in the 1930s and '40s. Vitamin fortification took off during World War II. The Basic 7 guidelines were first released during the war and were based on the recent vitamin research. But they also, consciously or not, reinforced white supremacy through food. Confident that they had solved the mystery of the invisible nutrients necessary for human health, American nutrition scientists turned toward reconfiguring them every which way possible. This is the history that gives us Wonder Bread and fortified breakfast cereals and milk. By divorcing vitamins from the foods in which they naturally occur (foods that were often expensive or scarce), nutrition scientists thought they could use equivalents to maintain a healthy diet. As long as people had access to vitamins, carbohydrates, proteins, and fats, it didn't matter how they were delivered. Or so they thought. This policy of reducing foods to their nutrients and divorcing food from tradition, culture, and emotion dates back to the Progressive Era and continues to today, sometimes with disastrous consequences. Commodities & NutritionDivorcing food from culture is one government policy Indigenous people understand well. U.S. treaty violations and land grabs led to the reservation system, which forcibly removed Native people from their traditional homelands, divorcing them from their traditional foodways as well. Post-WWII, the government helped stabilize crop prices by purchasing commodity foods for use in a variety of programs operated by the United States Department of Agriculture (USDA), including the National School Lunch Program, Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children (WIC), and the Food Distribution Program on Indian Reservations (FDPIR) program. For most of these programs, the government purchases surplus agricultural commodities to help stabilize the market and keep prices from falling. It then distributes the foods to low-income groups as a form of food assistance. Commodity foods distributed through the FDPIR program were generally canned and highly processed - high in fat, salt, and sugar and low in nutrients. This forced reliance on commodity foods combined with generational trauma and poverty led to widespread health disparities among Indigenous groups, including diabetes and obesity. Which is why I was appalled to find this cookbook the other day. Commodity Cooking for Good Health, published by the USDA in 1995 (1995!) is a joke, but it illustrates how pervasive and long-lasting the false equivalency of vitamins and calories can be. The cookbook starts with an outline of the 1992 Food Pyramid, whose base rests on bread, pasta, cereal, and rice. It then goes to outline how many servings of each group Indigenous people should be eating, listing 2-3 servings a day for the dairy category, but then listing only nonfat dry milk, evaporated milk, and processed cheese as the dairy options. In the fruit group, it lists five different fruit juices as servings of fruit. It has a whole chapter on diabetes and weight loss as well as encouraging people to count calories. With the exception of a recipe for fry bread, one for chili, and one for Tohono O'odham corn bread, the remainder of the recipes are extremely European. Even the "Mesa Grande Baked Potatoes" are not, as one would assume from the title, a fun take on baked whole potatoes, but rather a mixture of dehydrated mashed potato flakes, dried onion soup mix, evaporated milk, and cheese. You can read the whole cookbook for yourself, but the fact of the matter is that the USDA is largely responsible for poor health on reservations, not only because it provides the unhealthy commodity foods, but also because it was founded in 1862, the height of the Indian Wars, during attempts by the federal government at genocide and successful land grabs. Although the Bureau of Indian Affairs (BIA) under the Department of the Interior was largely responsible for the reservation system, the land grant agricultural college system started by the Hatch Act was literally built on the sale of stolen land. In addition, the USDA has a long history of dispossessing Black farmers, an issue that continues to this day through the denial of farm loans. Thanks to redlining, people of color, especially Black people, often live in segregated school districts whose property taxes are inadequate to cover expenses. Many children who attend these schools are low-income, and rely on free or reduced lunch delivered through the National School Lunch Program, which has been used for decades to prop up commodity agriculture. Although school lunch nutrition efforts have improved in recent years, many hot lunches still rely on surplus commodities and provide inadequate nutrition. Issues That PersistEven today, the federal nutrition guidelines, administered by the USDA, emphasize "meat and three" style meals accompanied by dairy. And while the recipe section is diversifying, it is still all-too-often full of Americanized versions of "ethnic" dishes. Many of the dishes are still very meat- and dairy-centric, and short on fresh fruits and vegetables. Some recipes, like this one, seem straight out of 1956. The idea that traditional ingredients should be replaced with "healthy" variations, for instance always replacing white rice with brown rice or, more recently cauliflower rice, continues. Many nutritionists also push the Mediterranean Diet as the healthiest in the world, when in fact it is very similar to other traditional diets around the world where people have access to plenty of unsaturated fats, fruits and vegetables, whole grains, lean meats, etc. Even the name - the "Mediterranean Diet," implies the diets of everyone living along the Mediterranean. So why does "Mediterranean" always mean Italian and Greek food, and never Persian, Egyptian, or Tunisian food? (Hint: the answer is racism). Old ideas about nutrition, including emphasis on low-fat foods, "meat and three" style recipes, replacement ingredients (usually poor cauliflower), and artificial sweeteners for diabetics, seem hard to shake for many people. Doctors receive very little training in nutrition and hospital food is horrific, as I saw when my father-in-law was hospitalized for several weeks in 2019. As a diabetic with problems swallowing, pancakes with sugar-free syrup, sugar-free gelatin and pudding, and not much else were their solution to his needs. The modern field of nutritionists is also overwhelmingly White, and racism persists, even towards trained nutritionists of color, much less communities of color struggling with health issues caused by generational trauma, food deserts, poverty, and overwork. Our modern food system has huge structural issues that continue to today. Why is the USDA, which is in charge of promoting agriculture at home and abroad, in charge of federal nutrition programs? Commodity food programs turn vulnerable people into handy props for industrial agriculture and the economy, rather than actually helping vulnerable people. Federal crop subsidies, insurance, and rules assigns way more value to commodity crops than fruits and vegetables. This government support also makes it easy and cheap for food processors to create ultra-processed, shelf-stable, calorie-dense foods for very little money - often for less than the crops cost to produce. This makes it far cheaper for people to eat ultra-processed foods than fresh fruits and vegetables. The federal government also gives money to agriculture promotion organizations that use federal funds to influence American consumers through advertising (remember the "Got Milk?" or "The Incredible, Edible Egg" marketing? That was your taxpayer dollars at work), regardless of whether or not the foods are actually good for Americans. Nutrition science as a field has a serious study replication problem, and an even more serious communications problem. Although scientists themselves usually do not make outrageous claims about their findings, the fact that food is such an essential part of everyday life, and the fact that so many Americans are unsure of what is "healthy" and what isn't, means that the media often capitalizes on new studies to make over-simplified announcements to drive viewership. Key TakeawaysNutrition science IS a science, and new discoveries are being made everyday. But the field as a whole needs to recognize and address the flawed scientific studies and methods of the past, including their racism - conscious or unconscious. Nutrition scientists are expanding their research into the many variables that challenge the research of the Progressive Era, including gut health, environmental factors, and even genetics. But human research is expensive, and test subjects rarely diverse. Nutrition science has a particularly bad study replication problem. If the government wants to get serious about nutrition, it needs to invest in new research with diverse subjects beyond the flawed one-size-fits-all rhetoric. The field of nutrition - including scientists, medical professionals, public health officials, and dieticians - need to get serious about addressing racism in the field. Both their own personal biases, as well as broader institutional and cultural ones. Anyone who is promoting "healthy" foods needs to think long and hard about who their audience is, how they're communicating, and what foods they're branding as "unhealthy" and why. We also need to address the systemic issues in our food system, including agriculture, food processing, subsidies, and more. In particular, the government agencies in charge of nutrition advice and food assistance need to think long and hard about the role of the federal government in promoting human health and what the priorities REALLY are - human health? or the economy? There is no "one size fits all" recommendation for human health. Ever. Especially not when it comes to food. Because nutrition guidelines have problems not just with racism, but also with ableism and economics. Not everyone can digest "healthy" foods, either due to medical issues or medication. Not everyone can get adequate exercise, due to physical, mental, or even economic issues. And I would argue that most Americans are not able to afford the quality and quantity of food they need to be "healthy" by government standards. And that's wrong. Like with human health, there are no easy solutions to these problems. But recognizing that there is a problem is the first step on the path to fixing them. Further ReadingMany of these were cited in the text of the article above, but they are organized here for clarity. I have organized them based on the topics listed above. (note: any books listed below are linked as part of the Amazon Affiliate program - any purchases made from those links will help support The Food Historian's free public articles like this one). EARLY NUTRITION SCIENCE

A HISTORY OF BODY MASS INDEX (BMI)

THE HISTORY OF THE CALORIE

MAKING "AMERICAN" FOOD

MILK - THE PERFECT FOOD

NUTRITION GUIDELINES HISTORY

COMMODITIES AND NUTRITION

ISSUES THAT PERSIST

The Food Historian blog is supported by patrons on Patreon! Patrons help keep blog posts like this one free and available to the public. Join us for awesome members-only content like free digitized cookbooks from my personal collection, e-newsletter, and even snail mail from time to time! Don't like Patreon? Leave a tip!

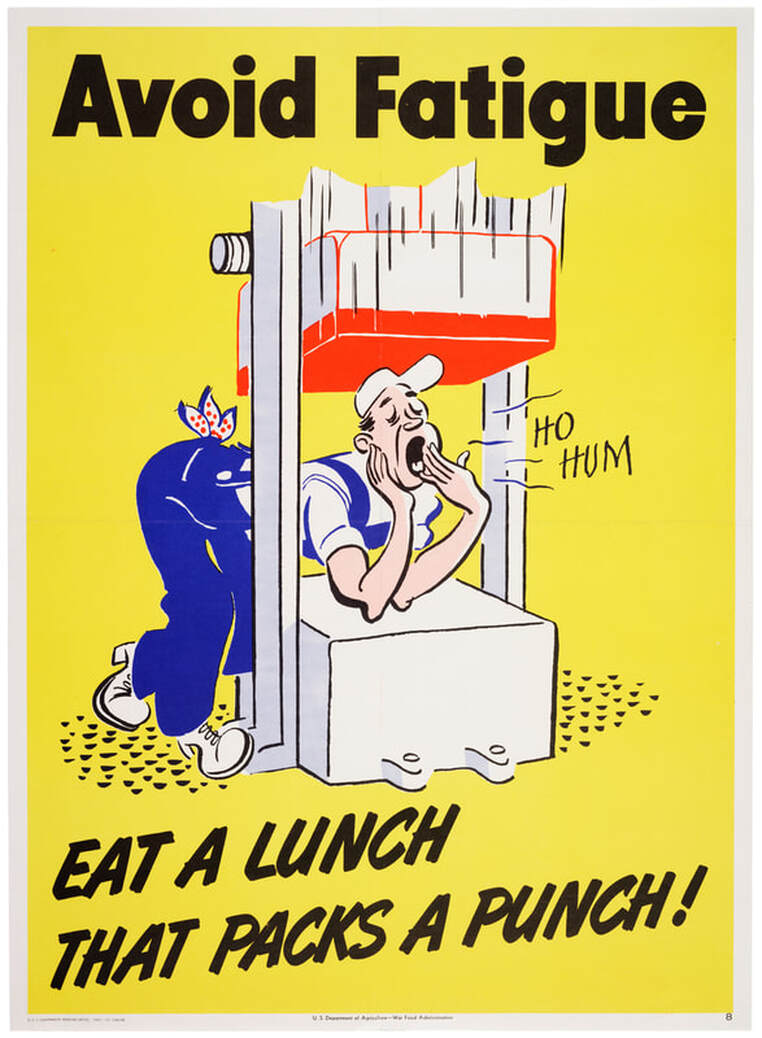

We've all had those days. Days where we forgot to bring lunch to work and can't get away to buy it, or when we bring a sad, cobbled-together lunch, or when we pick up fast food or something with empty calories. For many of us, a slow-moving afternoon or the distraction of a rumbling stomach isn't the end of the world. But during the Second World War, people didn't have the luxury of distraction of fatigue. This bold propaganda poster from c. 1943 features a yawning male worker leaning on the surface of what appears to be a stamping or hammering machine. He says, "Ho hum," feet crossed, leaning on his elbows, as a heavy block of metal descends toward his head. The poster reads, "Avoid fatigue! Eat a lunch that packs a punch!" During WWII, the United States engaged in total war. That meant that nearly every aspect of American society shifted toward the war effort. Nowhere was this more clear than in the everyday work of people in manufacturing. Men who weren't drafted for the war or working on farms often worked in factory settings. Factories that previously made machinery for consumer use - automobiles, refrigerators, washing machines, etc. - now found themselves manufacturing warplanes and Army jeeps and munitions. Factories worked on round-the-clock schedules, with three shifts a day. Some people worked much longer than 8 hours at a time. Although great strides had been made in ergonomics in factory work during the 1940s, the pressure of keeping up with military contracts and quotas was great. People often got too little sleep, and rationing made food supplies tight. During the war the U.S. federal government issued the Basic 7 - the first national nutrition guidelines ever issued. Based around the idea of balancing vitamin intake with protein, carbohydrates, and fats, the Basic 7 helped ordinary Americans better understand nutrition. Which is exactly what this poster is alluding to. "Eat a lunch that packs a punch" was a slogan also showed up in other posters, and alluded to calcium to keep bones strong, protein to build muscles, and Vitamin A to improve eyesight, among others. But this poster focuses on fatigue, which was a very real threat to the war machine. Tired workers made mistakes, hurt themselves, and could hurt or kill others. Operating flat out didn't leave room for mistakes, and a labor shortage thanks to the draft made skilled workers difficult to replace. Unbalanced meals, or not enough to eat, did not give war workers the energy they needed to perform at the highest levels at all times. The pressure of wartime work must have seemed unbearable at times. And with women increasingly joining the workforce and/or managing victory gardens and food preservation at home, not to mention coping with rationing, the idea of packing a large and nutritionally balanced lunch must have seemed like a lot of extra work for people. But while cafeterias were sometimes available, most people in factory work still packed their lunches. And while working at high speeds with dangerous equipment, it was worth it to make sure you weren't going to be too tired to do your job. There was no room for slacking off at work during the war, and getting proper nutrition to keep in peak physical health was so important the federal government spent a great deal of money advertising basic nutrition concepts (along with lots of posters about workplace safety) to ordinary Americans. Total war meant total commitment, total effort, and total focus. Staying healthy and well-fed was all part of total war. The Food Historian blog is supported by patrons on Patreon! Patrons help keep blog posts like this one free and available to the public. Join us for awesome members-only content like free digitized cookbooks from my personal collection, e-newsletter, and even snail mail from time to time! Don't like Patreon? Leave a tip!

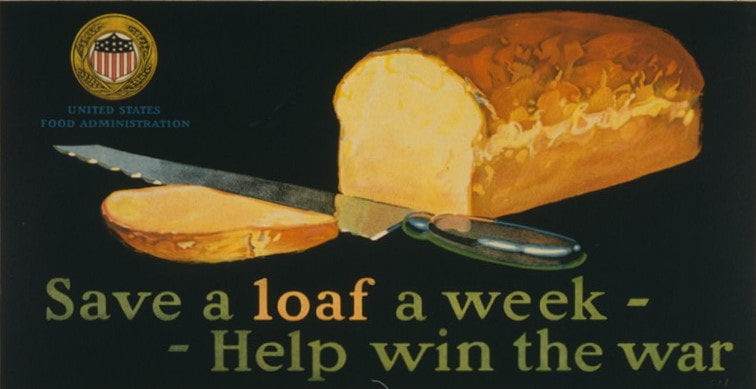

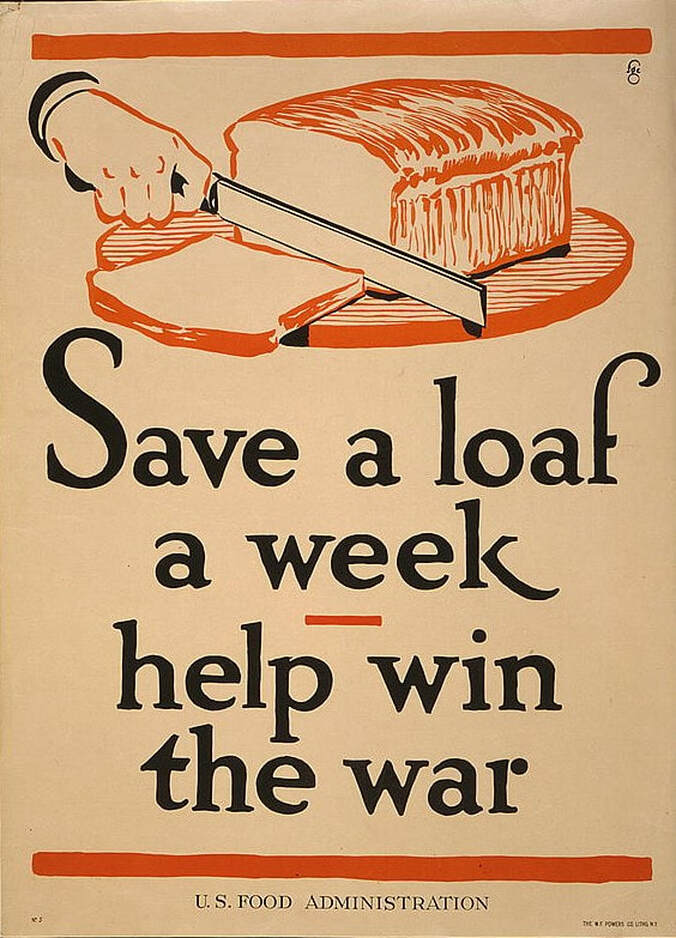

It's finally cold enough to bake in my neck of the woods. I made New York Gingerbread for a Halloween party this past weekend and it was delicious. You may be thinking of finally tackling the yeast bread you never made during the COVID shutdown. But like the early days of the pandemic when the shelves were empty of flour, during the First World War, wheat was in short supply. Poor wheat harvests in the fall of 1915 and 1916 meant that when the United States joined the war in April of 1917, there was not enough wheat to feed both the citizens of the United States and the military and their Allies. So the United States Food Administration embarked on a campaign to get Americans to voluntarily give up some of their favorite foods - including white bread made from wheat flour. By the 1910s white bread was ingrained (no pun intended) in the American diet and culture. It held onto its associations with wealth and refinement long after white flour became affordable and abundant. In addition, the conventional wisdom of nutrition science at the time elevated carbohydrates as a valuable source of energy. Which meant that both white bread and refined white sugar were considered healthful and important sources of the newly-discovered calories. Getting people to give up their favorite breakfast, side dish, and anytime (including midnight) snack was not going to be easy. This pair of propaganda posters produced by the USFA illustrate the same primary point - that if everyone gave up a little, the compound effect would be enormous. You'll note they don't focus on getting Americans to stop eating white bread - just to consume less. The implication of both posters is that be reducing consumption by as little as one slice a day would really add up. Other campaigns, including Wheatless Wednesday (partner to Meatless Monday), told Americans to replace the slice of bread customary with each meal with a baked potato, especially after the potato surplus in 1918. Alternative grains, especially corn, were also touted as substitutes for white bread. Restaurants were banned from bringing rolls or bread to the table before customers ordered their meal (sugar bowls were out, too). By 1918, one way the Food Administration tried to control the consumption of white bread without instituting mandatory rationing was to require Americans to purchase two pounds of alternative grains or flour for every one pound of wheat flour. However, although other campaigns emphasized corn as a valuable substitute, there's evidence that people may have just discarded the additional flours they were forced to purchase. Despite these challenges, the fact that the United States was able to feed their military, and the Allies, on the same 1916 wheat harvest suggests that Americans did reduce their wheat consumption in 1917. Today we know that refined white flour is a little too efficient a carbohydrate, and that the vitamins and minerals in whole grain flour, and the added fiber, are generally much better for human health. For wheatless recipes from the First World War, check out this article from North Carolina State University Libraries. The Food Historian blog is supported by patrons on Patreon! Patrons help keep blog posts like this one free and available to the public. Join us for awesome members-only content like free digitized cookbooks from my personal collection, e-newsletter, and even snail mail from time to time! Don't like Patreon? Join with an annual membership below, or just leave a tip! |

AuthorSarah Wassberg Johnson has an MA in Public History from the University at Albany and studies early 20th century food history. Archives

July 2024

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed