|

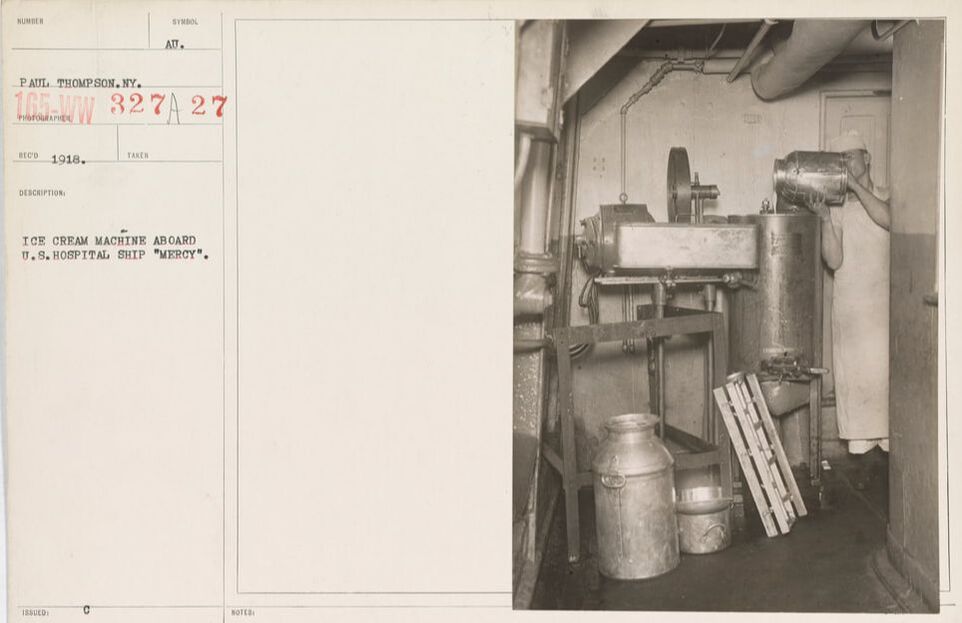

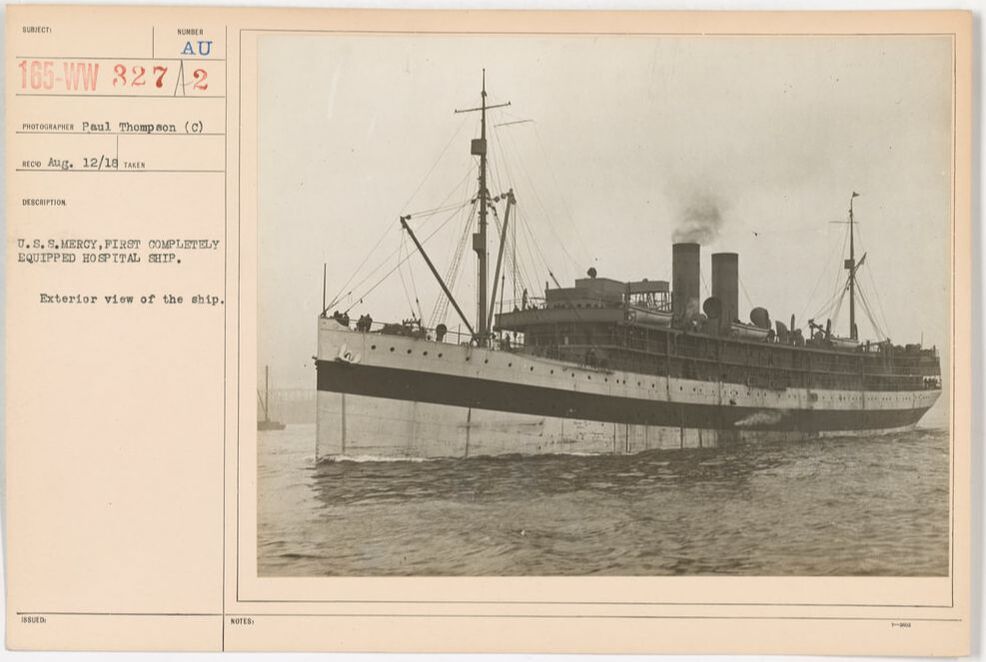

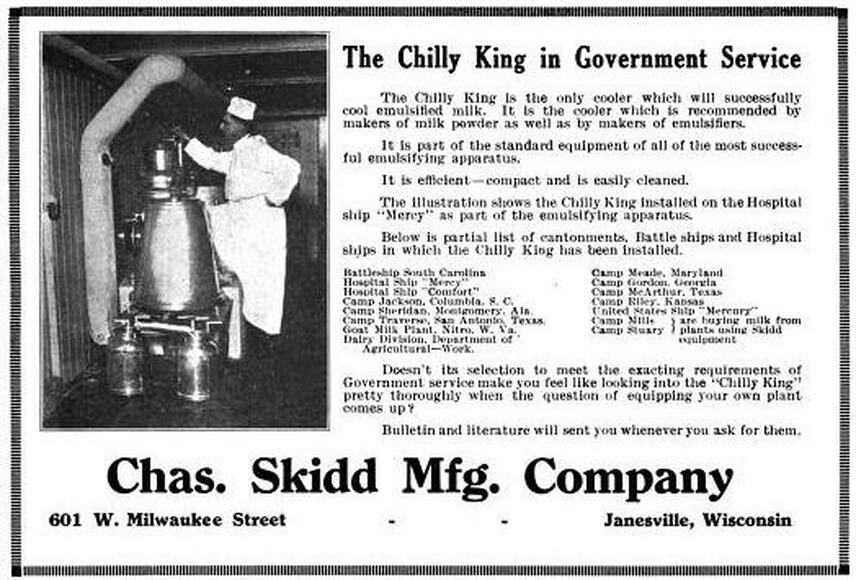

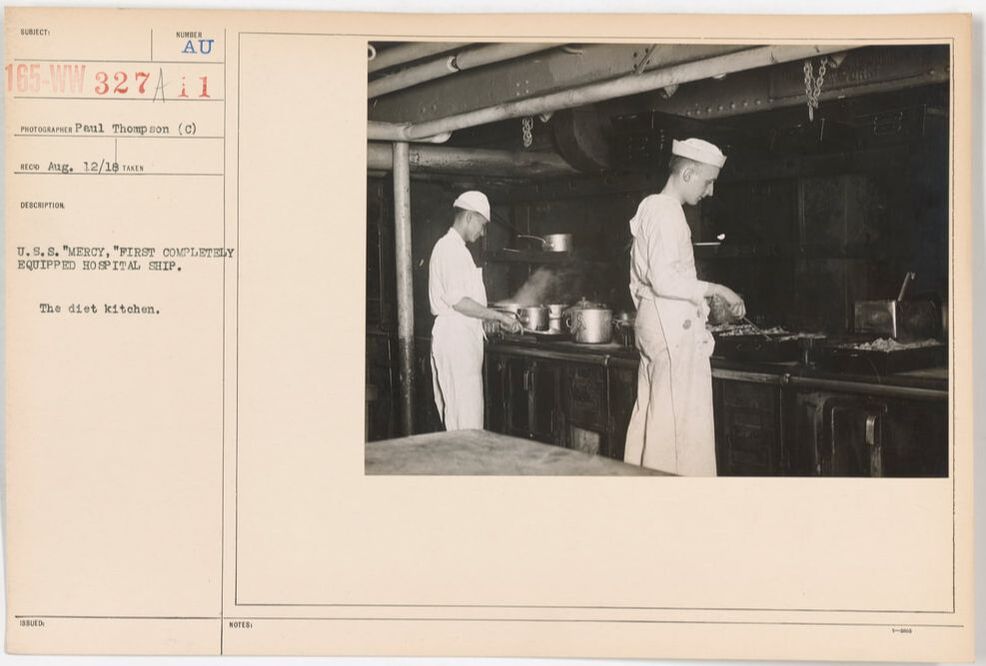

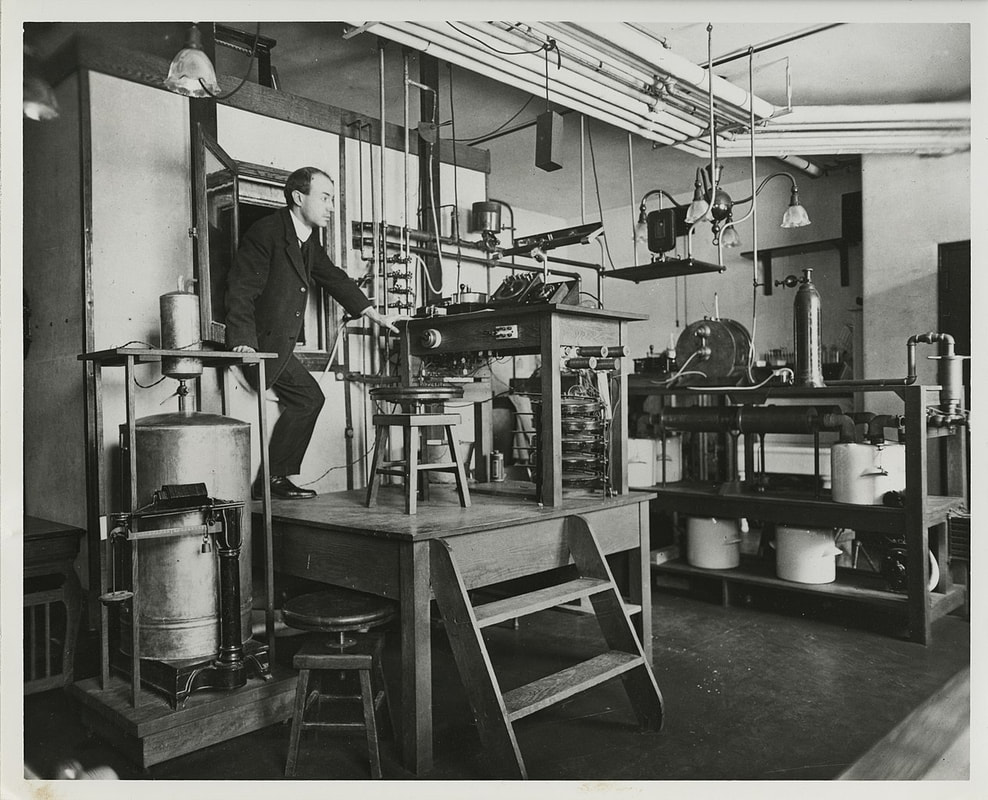

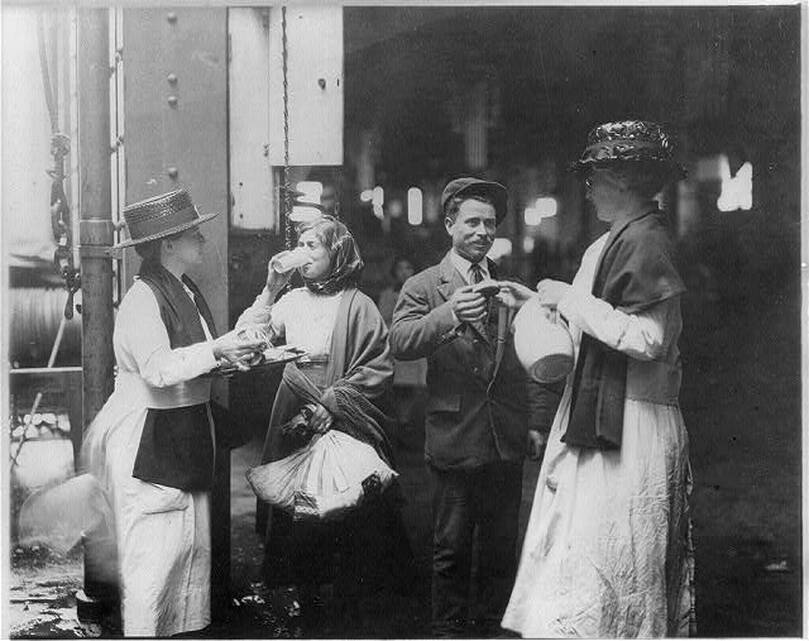

I've been getting a lot of calls for information about ice cream lately, and that has sent me down a rabbit hole. I did a whole talk on the history of ice cream last year (you can watch the filmed version here), but while I knew ice cream was a big tradition in naval history, I didn't know the connection to the First World War. I don't usually cover the history of military consumption of food during the World Wars, but this topic was just too much fun to resist. Ice cream wasn't always the Navy's treat of choice. For over a hundred years rum was the preferred ration by many sailors. But in the late 19th century the Temperance movement began to have increasing power over society. By 1919 we had a Constitutional Amendment (the 19th - often known just as "Prohibition"). But the armed forces went dry much earlier. In particular, on July 1, 1914, the U.S. Navy went alcohol-free. At the same time, naval vessels were being stocked with ice cream. In the May, 1913 issue of The Ice Cream Trade Journal, an article entitled "Sailors Like Ice Cream" explained that the Navy had recently ordered 350,000 pounds of evaporated milk - ostensibly for all sorts of cooking and baking, but ice cream was high on the list. You may wonder why hospital ships in the First World War were manufacturing ice cream on board? Well, it involves multiple factors. First is that ice cream was a product of milk; during the Progressive Era, milk was considered the "perfect food" as it contained fats, proteins, and carbohydrates all in one (supposedly) easily digestible package. Although many people are lactose intolerant, the White Anglo-Saxon dominance of American culture at the time prized milk. Ice cream rode into nutritional value on the coattails of milk. During this time period, dairy-based products like puddings, custards, milk and cream on cooked cereals or with toast, and ice cream were all considered nutritious foods for people who had been injured or ill. Along with foods like beef tea, eggs, and stewed fruits, these made up the bulk of recommended hospital foods from the late 19th century to World War I. Ice cream shows up quite frequently in early reports of the Surgeon General to the U.S. Navy. In his 1918 report to the Secretary of the Navy, ice cream appears to cause more problems than it solves. Notably, the use of ice cream produced commercially results in several instances of crew sickness, including simple illnesses like strep throat, alongside more serious ones like a diphtheria outbreak in Newport in 1917, which was traced to ice cream produced off-station. Fears of the spread of typhoid from places like restaurants, soda fountains, and ice cream shops led to "antityphoid inoculations" at naval shipyards. In Chicago, "All soft-drink and ice-cream stands have promised to give sailors individual service in the form of paper cups and dishes. To make this more effective, it is believed that an order should be issued prohibiting men from accepting any other kind of service." The Surgeon General also recommended inspection of offsite dairies and bottling works for milk, ice cream, and soft drinks to ensure proper sterilization of equipment and pasteurization of dairy products, as well as inoculation of employees against typhoid and smallpox. But ice cream was also noted as essential not only on the existing hospital ship USS Solace, but also on two new hospital ships fitted out since the declaration of war in 1917 - the USS Mercy and the USS Comfort. These ships included a cold storage plant and a refrigerating machine that could "produce, under favorable circumstances, a ton of ice or more a day." The ships also had distilling plants, able to convert seawater to fresh water, up to 20,000 gallons per day. In addition to describing the medical wards, crew facilities, laundry, and kitchen, the report noted: The most valuable adjunct in the treatment and feeding of the sick is the milk emulsifier, popularly known as the "mechanical cow." The milk produced from this machine is made from a combination of unsalted butter and skimmed milk powder and can be made with any proportion of butter fat and proteins desired. This machine will produce 15 gallons of cold, pasteurized milk in 45 minutes. The electric ice cream machine, controlled by one man, makes 10 gallons at a time and is supplemented by small freezers for preparing individual diets for the sick. According to the October, 1918 issue of The Milk Dealer, the "mechanical cow" had been displayed as part of the exhibits at the National Dairy Show in Columbus, Ohio in the fall of 1917. They noted: The "Mechanical Cow" Becoming Famous. Few people who saw the combination exhibit of Merrell-Soule Co. and the DeLaval Separator Co., last October, in Columbus, would have believed that within a year from that beginning the use of the Emulsor in combining Skimmed Milk Powder, unsalted butter and water would be taken up by Army, Navy, City Administrations, etc. throughout the United States. Such is the fact, however. The Mechanical Cow is now producing milk and cream on the U.S.S. Comfort and U.S.S. Mercy, the two splendid hospital ships of the Navy. An installation on board the U.S.S. South Carolina is kept working continuously to supply the demands of her crew. Mechanical Cows are filling the needs of milk at the base hospitals and several camps and one large machine is being operated by one of the city departments of New York. Health officers, physicians, milk experts and authorities on infant feeding all unanimously agree that milk and cream made by means of the "Mechanical Cow" is superior in every way to the average milk supply. This advertisement for "The Chilly King," a cooling machine that was part of the "Mechanical Cow" system on ships like the U.S.S. Mercy (a photograph of the machinery on board featured in the ad) also names a number of naval ships and military camps which use it, including:

By enabling ships and camps to use shelf-stable skimmed milk powder and unsalted butter, which keeps a very long time in cold storage, "mechanical cows" allowed for an ample supply of milk made in sanitary conditions. For naval ships, this was especially important when crews were away from shore for long periods of time. Ice cream also helped patients recover from illness (or so medical professionals at the time believed) but it also helped a great deal with morale. The professionalization of ship operations via the installation of state-of-the-art equipment was a hallmark of the First World War, but the U.S.'s late involvement in the war hamstrung most shipbuilding operations. Indeed, the construction of a new hospital ship in 1916 was actually shelved in favor of retrofitting existing ships like those that were transformed into the U.S.S. Comfort and U.S.S. Mercy, which had initially served as the sister passenger steamboats S.S. Havana and S.S. Saratoga, respectively. Part of the Ward Line, these very fast steamships ran the New York City to Havana, Cuba route but were requisitioned in 1917 first as troop transports, and later as hospital ships. The U.S.S. Mercy spent time as a home for the homeless during the Great Depression before she was scrapped in the 1930s, and the U.S.S. Comfort went back to civilian passenger transport for the Ward line under her old name, the S.S. Havana, before being pressed into service again in World War II, this time as a troop transport once again. The names USS Comfort and USS Mercy would be revived in World War II and a third pair of hospital ships bearing those names are still in operation today. Although ice cream is no longer considered central to the recuperation of the sick and wounded, it is still served on American naval vessels around the world. Ice cream would play an even more important role in the Navy during the Second World War. But that's a tale for another World War Wednesday! The Food Historian blog is supported by patrons on Patreon! Patrons help keep blog posts like this one free and available to the public. Join us for awesome members-only content like free digitized cookbooks from my personal collection, e-newsletter, and even snail mail from time to time! Don't like Patreon? Leave a tip!

0 Comments

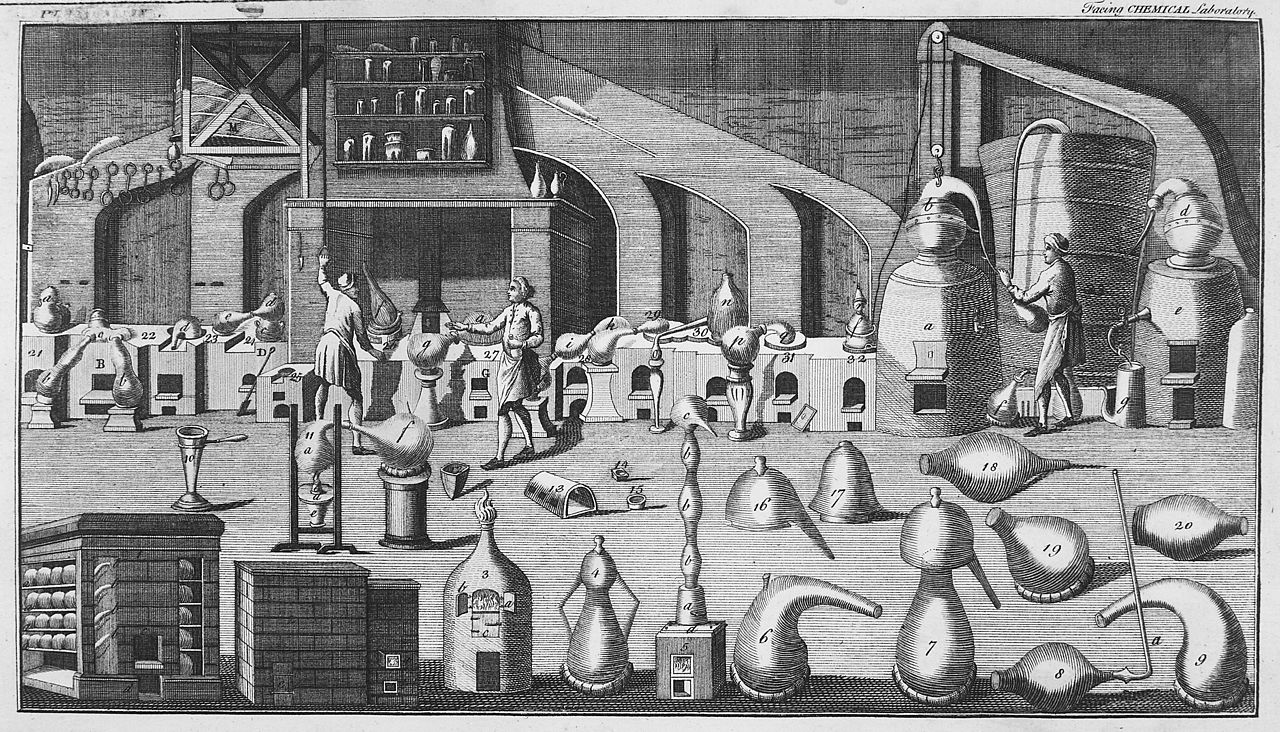

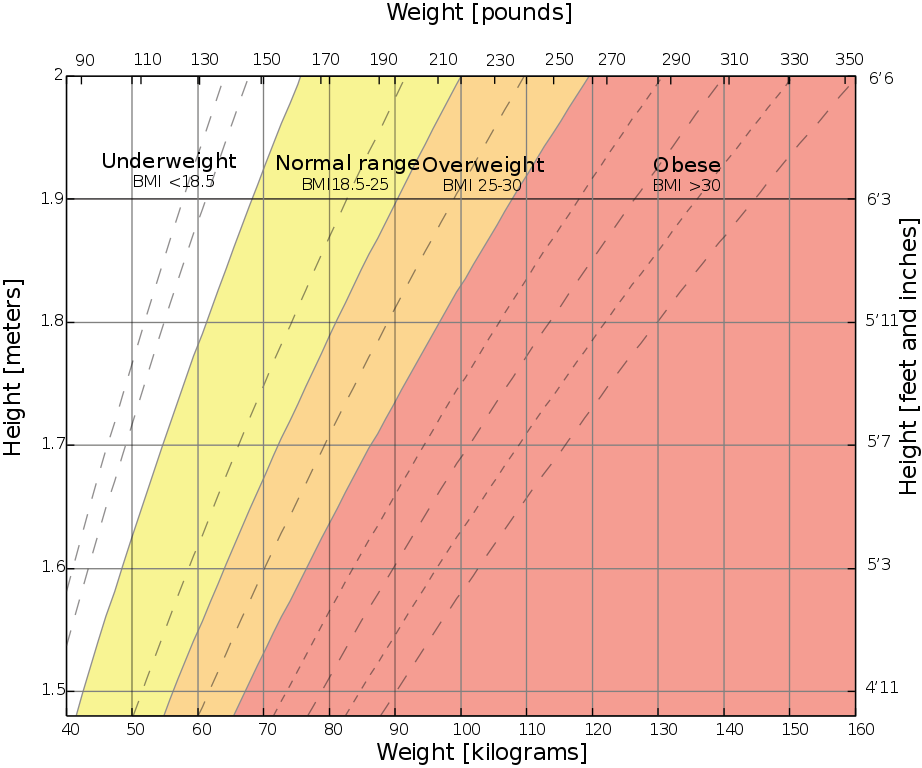

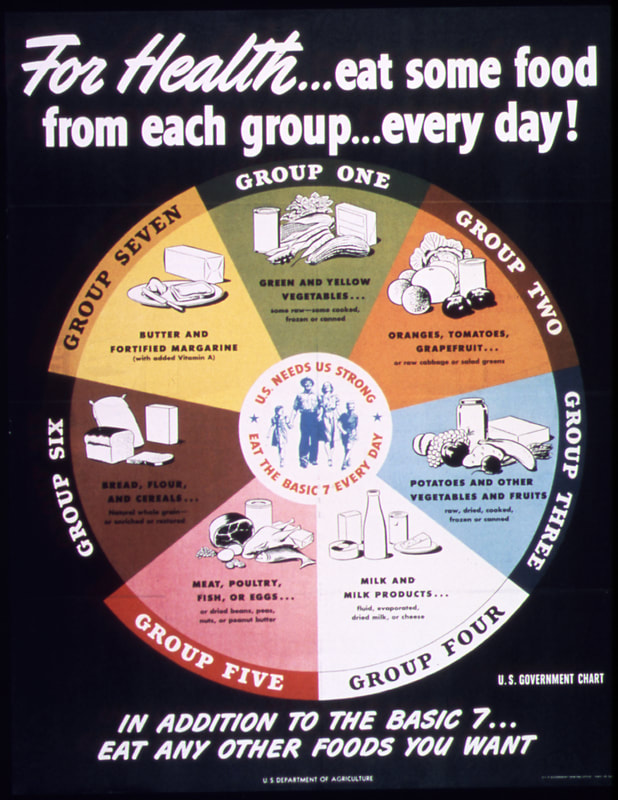

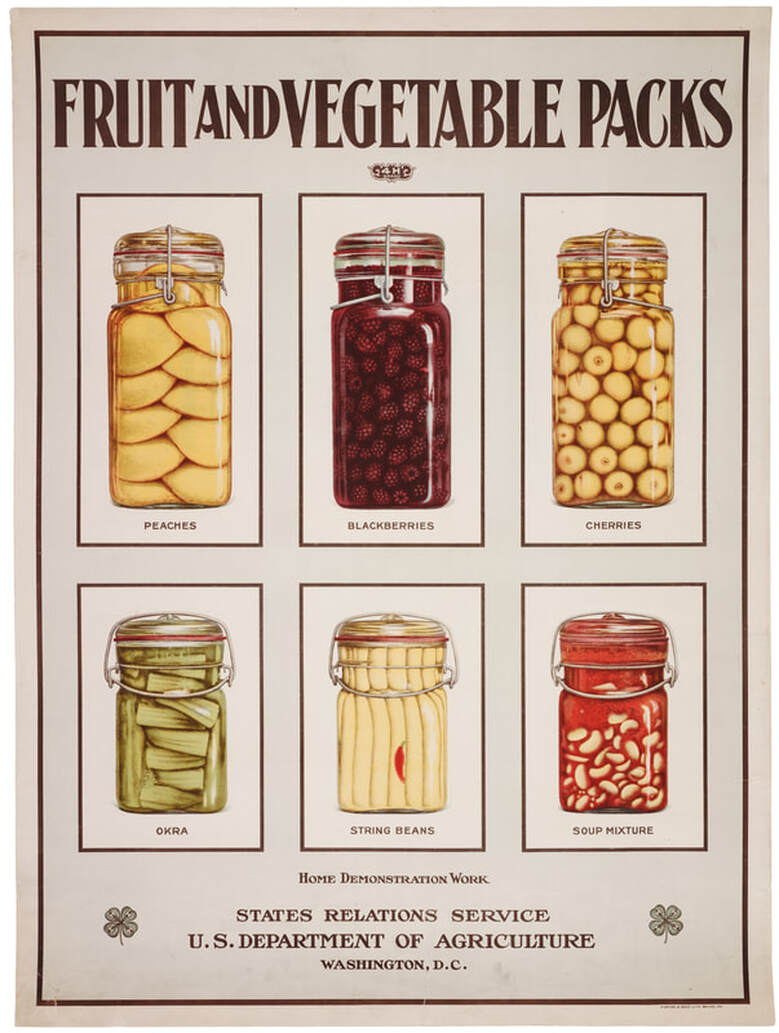

The short answer? At least in the United States? Yes. Let's look at the history and the reasons why. I post a lot of propaganda posters for World War Wednesday, and although it is implied, I don't point out often enough that they are just that - propaganda. They are designed to alter peoples' behavioral patterns using a combination of persuasion, authority, peer pressure, and unrealistic portrayals of culture and society. In the last several months of sharing propaganda posters on social media for World War Wednesday, I've gotten a couple of comments on how much they reflect an exclusively White perspective. Although White Anglo-Saxon Protestant culture was the dominant culture in the United States at the time, it was certainly not the only culture. And its dominance was the result of White supremacy and racism. This is reflected in the nutritional guidelines and nutrition science research of the time. The First World War takes place during the Progressive Era under a president who re-segregated federal workplaces that had been integrated since Reconstruction. It was also a time when eugenics was in full swing, and the burgeoning field of nutrition science was using racism as justifications for everything from encouraging assimilation among immigrant groups by decrying their foodways and promoting White Anglo-Saxon Protestant foodways like "traditional" New England and British foods to encouraging "better babies" to save the "White race" from destruction. Nutrition science research with human subjects used almost exclusively adult White men of middle- and upper-middle class backgrounds - usually in college. Certain foods, like cow's milk, were promoted heavily as health food. Notions of purity and cleanliness also influenced negative attitudes about immigrants, African Americans, and rural Americans. During World War II, Progressive-Era-trained nutritionists and nutrition scientists helped usher in a stereotypically New England idea of what "American" food looked like, helping "kill" already declining regional foodways. Nutrition research, bolstered by War Department funds, helped discover and isolate multiple vitamins during this time period. It's also when the first government nutrition guidelines came out - the Basic 7. Throughout both wars, the propaganda was focused almost exclusively on White, middle- and upper-middle-class Americans. Immigrants and African Americans were the target of some campaigns for changing household habits, usually under the guise of assimilation. African Americans were also the target of agricultural propaganda during WWII. Although there was plenty of overt racism during this time period, including lynching, race massacres, segregation, Jim Crow laws, and more, most of the racism in nutrition, nutrition science, and home economics came in two distinct types - White supremacy (that is, the belief that White Anglo-Saxon Protestant values were superior to every other ethnicity, race, and culture) and unconscious bias. So let's look at some of the foundations of modern nutrition science through these lenses. Early Nutrition ScienceNutrition Science as a field is quite young, especially when compared to other sciences. The first nutrients to be isolated were fats, carbohydrates, and proteins. Fats were the easiest to determine, since fat is visible in animal products and separates easily in liquids like dairy products and plant extracts. The term "protein" was coined in the 1830s. Carbohydrates began to be individually named in the early 19th century, although that term was not coined until the 1860s. Almost immediately, as part of nearly any early nutrition research, was the question of what foods could be substituted "economically" for other foods to feed the poor. This period of nutrition science research coordinated with the Enlightenment and other pushes to discover, through experimentation, the mechanics of the universe. As such, it was largely limited to highly educated, White European men (although even Wikipedia notes criticism of such a Euro-centric approach). As American colleges and universities, especially those driven by the Hatch Act of 1877, expanded into more practical subjects like agriculture, food and nutrition research improved. American scientists were concerned more with practical applications, rather than searching for knowledge for knowledge's sake. They wanted to study plant and animal genetics and nutrition to apply that information on farms. And the study of human nutrition was not only to understand how humans metabolized foods, but also to apply those findings to human health and the economy. But their research was influenced by their own personal biases, conscious and unconscious. The History of Body Mass Index (BMI)Body Mass Index, or BMI, is a result of that same early 19th century time period. It was invented by Belgian mathematician Lambert Adolphe Jacques Quetelet in the 1830s and '40s specifically as a "hack" for determining obesity levels across wide swaths of population, not for individuals. Quetelet was a trained astronomist - the one field where statistical analysis was prevalent. Quetelet used statistics as a research tool, publishing in 1835 a book called Sur l'homme et le développement de ses facultés, ou Essai de physique sociale, the English translation of which is usually called A Treatise on Man and the Development of His Faculties. In it, he discusses the use of statistics to determine averages for humanity (mainly, White European men). BMI became part of that statistical analysis. Quetelet named the index after himself - it wasn't until 1972 that researcher Ancel Keys coined the term "Body Mass Index," and as he did so he complained that it was no better or worse than any other relative weight index. Quetelet's work went on to influence several famous people, including Francis Galton, a proponent of social Darwinism and scientific racism who coined the term "eugenics," and Florence Nightingale, who met him in person. As a tool for measuring populations, BMI isn't bad. It can look at statistical height and weight data and give a general idea of the overall health of population. But when it is used as a tool to measure the health of individuals, it becomes extremely flawed and even dangerous. Quetelet had to fudge the math to make the index work, even with broad populations. And his work was based on White European males who he considered "average" and "ideal." Quetelet was not a nutrition scientist or a doctor - this "ideal" was purely subjective, not scientific. Despite numerous calls to abandon its use, the medical community continues to use BMI as a measure of individual health. Because it is a statistical tool not based on actual measures of health, BMI places people with different body types in overweight and obese categories, even if they have relatively low body fat. It can also tell thin people they are healthy, even when other measurements (activity level, nutrition, eating disorders, etc.) are signaling an unhealthy lifestyle. In addition, fatphobia in the medical community (which is also based on outdated ideas, which we'll get to) has vilified subcutaneous fat, which has less impact on overall health and can even improve lifespans. Visceral fat, or the abdominal fat that surrounds your organs, can be more damaging in excess, which is why some scientists and physicians advocate for switching to waist ratio measurements. So how is this racist? Because it was based on White European male averages, it often punishes women and people of color whose genetics do not conform to Quetelet's ideal. For instance, people with higher muscle mass can often be placed in the "overweight" or even "obese" category, simply because BMI uses an overall weight measure and assumes a percentage of it is fat. Tall people and people with broader than "ideal" builds are also not accurately measured. The History of the CalorieAlthough more and more people are moving away from measuring calories as a health indicator, for over 100 years they have reigned as the primary measure of food intake efficiency by nutritionists, doctors, and dieters alike. The calorie is a unit of heat measurement that was originally used to describe the efficiency of steam engines. When Wilbur Olin Atwater began his research into how the human body metabolizes food and produces energy, he used the calorie to measure his findings. His research subjects were the White male students at Wesleyan University, where he was professor. Atwater's research helped popularize the idea of the calorie in broader society, and it became essential learning for nutrition scientists and home economists in the burgeoning field - one of the few scientific avenues of study open to women. Atwater's research helped spur more human trials, usually "Diet Squads" of young middle- and upper-middle-class White men. At the time, many papers and even cookbooks were written about how the working poor could maximize their food budgets for effective nutrition. Socialists and working class unionists alike feared that by calculating the exact number of calories a working man needed to survive, home economists were helping keep working class wages down, by showing that people could live on little or inexpensive food. Calculating the calories of mixed-food dishes like casseroles, stews, pilafs, etc. was deemed too difficult, so "meat and three" meals were emphasized by home economists. Making "American" FoodEfforts to Americanize and assimilate immigrants went into full swing in the late 19th and early 20th centuries as increasing numbers of "undesirable" immigrants from Ireland, southern Italy, Greece, the Middle East, China, Eastern Europe (especially Jews), Russia, etc. poured into American cities. Settlement workers and home economists alike tried to Americanize with varying degrees of sensitivity. Some were outright racist, adopting a eugenics mindset, believing and perpetuating racist ideas about criminology, intelligence, sanitation, and health. Others took a more tempered approach, trying to convince immigrants to give up the few things that reminded them of home - especially food. These often engaged in the not-so-subtle art of substitution. For instance, suggesting that because Italian olive oil and butter were expensive, they should be substituted with margarine. Pasta was also expensive and considered to be of dubious nutritional value - oatmeal and bread were "better." A select few realized that immigrant foodways were often nutritionally equivalent or even superior to the typical American diet. But even they often engaged in the types of advice that suggested substituting familiar ingredients with unfamiliar ones. Old ideas about digestion also influenced food advice. Pickled vegetables, spicy foods, and garlic were all incredibly suspect and scorned - all hallmarks of immigrant foodways and pushcart operators in major American cities. The "American" diet advocated by home economists was highly influenced by Anglo-Saxon and New England ideals - beef, butter, white bread, potatoes, whole cow's milk, and refined white sugar were the nutritional superstars of this cuisine. Cooking foods separately with few sauces (except white sauce) was also a hallmark - the "meat and three" that came to dominate most of the 20th century's food advice. Rooted in English foodways, it was easy for other Northern European immigrants to adopt. Although French haute cuisine was increasingly fashionable from the Gilded Age on, it was considered far out of reach of most Americans. French-style sauces used by middle- and lower-class cooks were often deemed suspect - supposedly disguising spoiled meat. Post-Civil War, Yankee New England foodways were promoted as "American" in an attempt to both define American foodways (which reflected the incredibly diverse ecosystems of the United States and its diverse populations) and to unite the country after the Civil War. Sarah Josepha Hale's promotion of Thanksgiving into a national holiday was a big part of the push to define "American" as White and Anglo-Saxon. This push to "Americanize" foodways also neatly ignores or vilifies Indigenous, Asian-American, and African American foodways. "Soul food," "Chinese," and "Mexican" are derided as unhealthy junk food. In fact, both were built on foundations of fresh, seasonal fruits, vegetables, and whole grains. But as people were removed from land and access to land, the they adapted foodways to reflect what was available and what White society valued - meat, dairy, refined flour, etc. Asian food in particular was adapted to suit White palates. We won't even get into the term "ethnic food" and how it implies that anything branded as such isn't "American" (e.g. White). Divorcing foodways from their originators is also hugely problematic. American food has a big cultural appropriation problem, especially when it comes to "Mexican" and "Asian" foods. As late as the mid-2000s, the USDA website had a recipe for "Oriental salad," although it has since disappeared. Instead, we get "Asian Mango Chicken Wraps," and the ingredients of mango, Napa cabbage, and peanut butter are apparently what make this dish "Asian," rather than any reflection of actual foodways from countries in Asia. Milk - The Perfect FoodCombining both nutrition research of the 19th century and also ideas about purity and sanitation, whole cow's milk was deemed by nutrition scientists and home economists to be "the perfect food" - as it contained proteins, fats, and carbohydrates, all in one package. Despite issues with sanitation throughout the 19th century (milk wasn't regularly pasteurized until the 1920s), milk became a hallmark of nutrition advice throughout the Progressive Era - advice which continues to this day. Throughout the history of nutritional guidelines in the U.S., milk and dairy products have remained a mainstay. But the preponderance of advice about dairy completely ignores that wide swaths of the population are lactose intolerant, and/or did not historically consume dairy the way Europeans did. Indigenous Americans, and many people of African and Asian descent historically did not consume cow's milk and their bodies often do not process it well. This fact has been capitalized upon by both historic and modern racists, as milk as become a symbol of the alt-right. Even today, the USDA nutrition guidelines continue to recommend at least three servings of dairy per day, an amount that can cause long term health problems in communities that do not historically consume large amounts of dairy. Nutrition Guidelines HistoryBecause Anglo-centric foodways were considered uniquely "American" and also the most wholesome, this style of food persisted in government nutritional guidelines. Government-issued food recommendations and recipes began to be released during the First World War and continued during the Great Depression and World War II. These guidelines and advice generally reinforced the dominant White culture as the most desirable. Vitamins were first discovered as part of research into the causes of what would come to be understood as vitamin deficiencies. Scurvy (Vitamin C deficiency), rickets (Vitamin D deficiency), beriberi (Vitamin B1 or thiamine deficiency), and pellagra (Vitamin B2 or niacin deficiency) plagued people around the world in the 19th and early 20th centuries. Vitamin C was the first to be isolated in 1914. The rest followed in the 1930s and '40s. Vitamin fortification took off during World War II. The Basic 7 guidelines were first released during the war and were based on the recent vitamin research. But they also, consciously or not, reinforced white supremacy through food. Confident that they had solved the mystery of the invisible nutrients necessary for human health, American nutrition scientists turned toward reconfiguring them every which way possible. This is the history that gives us Wonder Bread and fortified breakfast cereals and milk. By divorcing vitamins from the foods in which they naturally occur (foods that were often expensive or scarce), nutrition scientists thought they could use equivalents to maintain a healthy diet. As long as people had access to vitamins, carbohydrates, proteins, and fats, it didn't matter how they were delivered. Or so they thought. This policy of reducing foods to their nutrients and divorcing food from tradition, culture, and emotion dates back to the Progressive Era and continues to today, sometimes with disastrous consequences. Commodities & NutritionDivorcing food from culture is one government policy Indigenous people understand well. U.S. treaty violations and land grabs led to the reservation system, which forcibly removed Native people from their traditional homelands, divorcing them from their traditional foodways as well. Post-WWII, the government helped stabilize crop prices by purchasing commodity foods for use in a variety of programs operated by the United States Department of Agriculture (USDA), including the National School Lunch Program, Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children (WIC), and the Food Distribution Program on Indian Reservations (FDPIR) program. For most of these programs, the government purchases surplus agricultural commodities to help stabilize the market and keep prices from falling. It then distributes the foods to low-income groups as a form of food assistance. Commodity foods distributed through the FDPIR program were generally canned and highly processed - high in fat, salt, and sugar and low in nutrients. This forced reliance on commodity foods combined with generational trauma and poverty led to widespread health disparities among Indigenous groups, including diabetes and obesity. Which is why I was appalled to find this cookbook the other day. Commodity Cooking for Good Health, published by the USDA in 1995 (1995!) is a joke, but it illustrates how pervasive and long-lasting the false equivalency of vitamins and calories can be. The cookbook starts with an outline of the 1992 Food Pyramid, whose base rests on bread, pasta, cereal, and rice. It then goes to outline how many servings of each group Indigenous people should be eating, listing 2-3 servings a day for the dairy category, but then listing only nonfat dry milk, evaporated milk, and processed cheese as the dairy options. In the fruit group, it lists five different fruit juices as servings of fruit. It has a whole chapter on diabetes and weight loss as well as encouraging people to count calories. With the exception of a recipe for fry bread, one for chili, and one for Tohono O'odham corn bread, the remainder of the recipes are extremely European. Even the "Mesa Grande Baked Potatoes" are not, as one would assume from the title, a fun take on baked whole potatoes, but rather a mixture of dehydrated mashed potato flakes, dried onion soup mix, evaporated milk, and cheese. You can read the whole cookbook for yourself, but the fact of the matter is that the USDA is largely responsible for poor health on reservations, not only because it provides the unhealthy commodity foods, but also because it was founded in 1862, the height of the Indian Wars, during attempts by the federal government at genocide and successful land grabs. Although the Bureau of Indian Affairs (BIA) under the Department of the Interior was largely responsible for the reservation system, the land grant agricultural college system started by the Hatch Act was literally built on the sale of stolen land. In addition, the USDA has a long history of dispossessing Black farmers, an issue that continues to this day through the denial of farm loans. Thanks to redlining, people of color, especially Black people, often live in segregated school districts whose property taxes are inadequate to cover expenses. Many children who attend these schools are low-income, and rely on free or reduced lunch delivered through the National School Lunch Program, which has been used for decades to prop up commodity agriculture. Although school lunch nutrition efforts have improved in recent years, many hot lunches still rely on surplus commodities and provide inadequate nutrition. Issues That PersistEven today, the federal nutrition guidelines, administered by the USDA, emphasize "meat and three" style meals accompanied by dairy. And while the recipe section is diversifying, it is still all-too-often full of Americanized versions of "ethnic" dishes. Many of the dishes are still very meat- and dairy-centric, and short on fresh fruits and vegetables. Some recipes, like this one, seem straight out of 1956. The idea that traditional ingredients should be replaced with "healthy" variations, for instance always replacing white rice with brown rice or, more recently cauliflower rice, continues. Many nutritionists also push the Mediterranean Diet as the healthiest in the world, when in fact it is very similar to other traditional diets around the world where people have access to plenty of unsaturated fats, fruits and vegetables, whole grains, lean meats, etc. Even the name - the "Mediterranean Diet," implies the diets of everyone living along the Mediterranean. So why does "Mediterranean" always mean Italian and Greek food, and never Persian, Egyptian, or Tunisian food? (Hint: the answer is racism). Old ideas about nutrition, including emphasis on low-fat foods, "meat and three" style recipes, replacement ingredients (usually poor cauliflower), and artificial sweeteners for diabetics, seem hard to shake for many people. Doctors receive very little training in nutrition and hospital food is horrific, as I saw when my father-in-law was hospitalized for several weeks in 2019. As a diabetic with problems swallowing, pancakes with sugar-free syrup, sugar-free gelatin and pudding, and not much else were their solution to his needs. The modern field of nutritionists is also overwhelmingly White, and racism persists, even towards trained nutritionists of color, much less communities of color struggling with health issues caused by generational trauma, food deserts, poverty, and overwork. Our modern food system has huge structural issues that continue to today. Why is the USDA, which is in charge of promoting agriculture at home and abroad, in charge of federal nutrition programs? Commodity food programs turn vulnerable people into handy props for industrial agriculture and the economy, rather than actually helping vulnerable people. Federal crop subsidies, insurance, and rules assigns way more value to commodity crops than fruits and vegetables. This government support also makes it easy and cheap for food processors to create ultra-processed, shelf-stable, calorie-dense foods for very little money - often for less than the crops cost to produce. This makes it far cheaper for people to eat ultra-processed foods than fresh fruits and vegetables. The federal government also gives money to agriculture promotion organizations that use federal funds to influence American consumers through advertising (remember the "Got Milk?" or "The Incredible, Edible Egg" marketing? That was your taxpayer dollars at work), regardless of whether or not the foods are actually good for Americans. Nutrition science as a field has a serious study replication problem, and an even more serious communications problem. Although scientists themselves usually do not make outrageous claims about their findings, the fact that food is such an essential part of everyday life, and the fact that so many Americans are unsure of what is "healthy" and what isn't, means that the media often capitalizes on new studies to make over-simplified announcements to drive viewership. Key TakeawaysNutrition science IS a science, and new discoveries are being made everyday. But the field as a whole needs to recognize and address the flawed scientific studies and methods of the past, including their racism - conscious or unconscious. Nutrition scientists are expanding their research into the many variables that challenge the research of the Progressive Era, including gut health, environmental factors, and even genetics. But human research is expensive, and test subjects rarely diverse. Nutrition science has a particularly bad study replication problem. If the government wants to get serious about nutrition, it needs to invest in new research with diverse subjects beyond the flawed one-size-fits-all rhetoric. The field of nutrition - including scientists, medical professionals, public health officials, and dieticians - need to get serious about addressing racism in the field. Both their own personal biases, as well as broader institutional and cultural ones. Anyone who is promoting "healthy" foods needs to think long and hard about who their audience is, how they're communicating, and what foods they're branding as "unhealthy" and why. We also need to address the systemic issues in our food system, including agriculture, food processing, subsidies, and more. In particular, the government agencies in charge of nutrition advice and food assistance need to think long and hard about the role of the federal government in promoting human health and what the priorities REALLY are - human health? or the economy? There is no "one size fits all" recommendation for human health. Ever. Especially not when it comes to food. Because nutrition guidelines have problems not just with racism, but also with ableism and economics. Not everyone can digest "healthy" foods, either due to medical issues or medication. Not everyone can get adequate exercise, due to physical, mental, or even economic issues. And I would argue that most Americans are not able to afford the quality and quantity of food they need to be "healthy" by government standards. And that's wrong. Like with human health, there are no easy solutions to these problems. But recognizing that there is a problem is the first step on the path to fixing them. Further ReadingMany of these were cited in the text of the article above, but they are organized here for clarity. I have organized them based on the topics listed above. (note: any books listed below are linked as part of the Amazon Affiliate program - any purchases made from those links will help support The Food Historian's free public articles like this one). EARLY NUTRITION SCIENCE

A HISTORY OF BODY MASS INDEX (BMI)

THE HISTORY OF THE CALORIE

MAKING "AMERICAN" FOOD

MILK - THE PERFECT FOOD

NUTRITION GUIDELINES HISTORY

COMMODITIES AND NUTRITION

ISSUES THAT PERSIST

The Food Historian blog is supported by patrons on Patreon! Patrons help keep blog posts like this one free and available to the public. Join us for awesome members-only content like free digitized cookbooks from my personal collection, e-newsletter, and even snail mail from time to time! Don't like Patreon? Leave a tip!

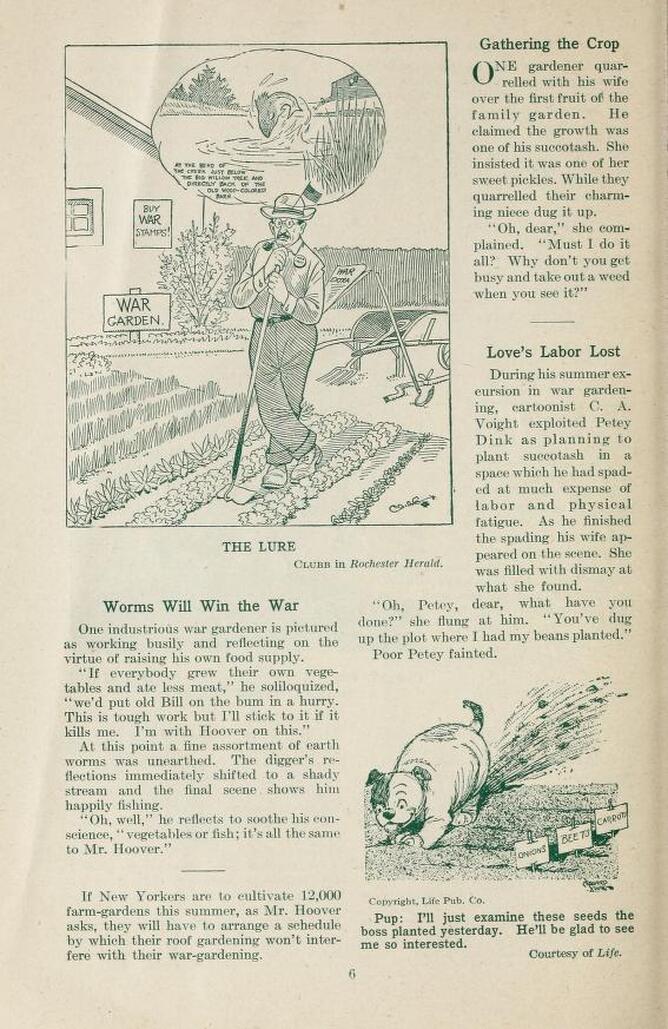

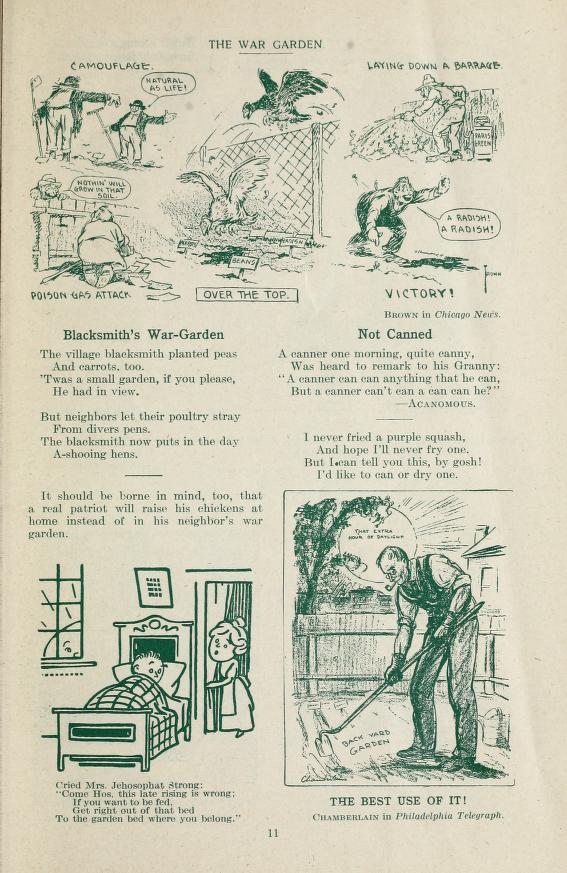

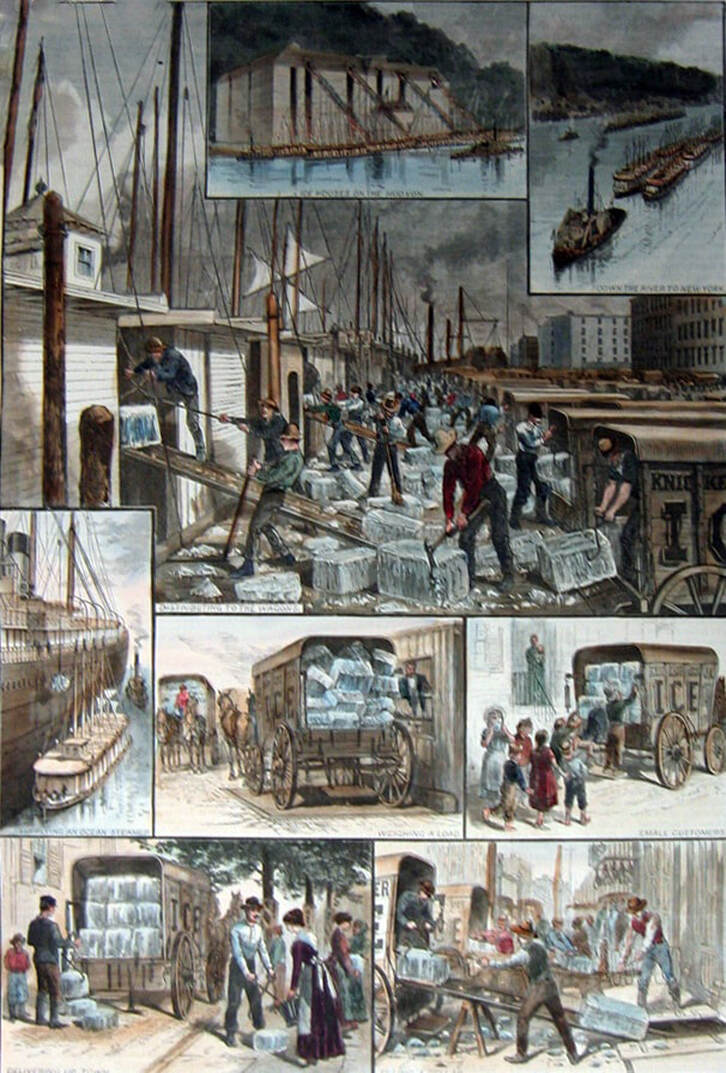

Although literal tons of snow have fallen across the United States in the past week or so, it's still beginning to feel like spring, which for many of us means our thoughts turn to gardening. If you know anything about World War II, you've probably heard of Victory Gardens. But did you know they got their start in the First World War? And the popularity of "war gardens" as they were initially called, is largely thanks to a man named Charles Lathrop Pack. Pack was the heir to a forestry and lumber fortune, and pumped lots of his own money into creating the National War Garden Commission, which promoted war gardening across the country, along with food preservation. They published a number of propaganda posters and instructional pamphlets. Today's World War Wednesday feature is another pamphlet, but its primary audience was not the general public, but rather newspaper and magazine publishers! Full of snippets of poetry, jokes, cartoons, and articles published by newspapers and magazines around the country, even the title was a bit of a joke. "The War Garden Guyed" is a play on the words "guide" and the verb "guy" which means to make fun of, or ridicule. So "The War Garden Guyed" is both a manual to war gardens and also a way to make fun of them. In the introduction, the National War Garden Commission (likely Charles Lathrop Pack himself), writes: "This publication treats of the lighter side of the war garden movement and the canning and drying campaign. Fortunately a national sense of humor makes it possible for the cartoonist and the humorist to weave their gentle laughter into the fabric of food emergency. That they have winged their shafts at the war gardener and the home canner serves only to emphasize the vital value of these activities." Each page of the "guyed" has at least one image and a few bits of either prose or poetry. The below page is one of my favorites. In the upper cartoon, an older man leans on his hoe in a very orderly war garden. His house in the background features a large "War Garden" sign and a poster saying "Buy War Stamps!" In his pocket is a folded newspaper with the headline "War Extra." But he is dreaming of a lake with jumping fish and the caption - indicating the location of the best fishing spot. The cartoon is called "The Lure" and demonstrates how people ordinarily would have been spending their summers. In the lower right hand corner, a roly poly little dog digs frantically in fresh soil. Little signs read "Onions, Beets, Carrots." The caption says "Pup: I'll just examine these seeds the boss planted yesterday. He'll be glad to see me so interested." Another article on the page is titled "Love's Labor Lost." It reads: "During his summer excursion in war gardening, cartoonist C. A. Voight exploited Petey Dink as planning to plant succotash in a space which had had spaded at much expense of labor and physical fatigue. As he finished the spading his wife appeared on the scene. She was filled with dismay at what she found. 'Oh Petey, dear, what have you done?' she flung at him. 'You've dug up the plot where I had my beans planted.' Poor Petey fainted." Many of the bits of doggerel and cartoons poked fun at inexperienced gardeners like Petey Dink. Pests, animals, digging up backyards and hauling water, the difficulty in telling weeds from seedlings, and finally the joy at the first crop. This page has a comic at the top that illustrates these trials and tribulations perfectly, through the lens of war. In the upper left hand corner, a sketch entitled "Camouflage" depicts a man who has just finished putting up a scarecrow who crows, "Natural as life!" as he poses exactly the same as his creation. Below, another called "Poison Gas Attack" depicts a neighbor leaning over the fence to comment "Nothin will grow in that soil" at a man kneeling in the dirt, a bowl of seed packets and a hoe on either side of him. The title implies that the neighbor is full of hot air and poison. The center scene, titled "Over the Top," shows a pair of chickens gleefully flying over a fence to attack a plot marked "Carrots," "Beans," and "Radishes." In the top right-hand corner, in a sketch titled "Laying Down a Barrage," a man with a pump cannister labeled "Paris Green" is spraying his plants. Paris Green was an arsenical pesticide. And finally, in one labeled "Victory!" a man gleefully points to a small seedling in an otherwise empty row and cries, "A radish! A radish!" In a bit of verse called "Not Canned" reads: A canner one morning, quite canny, Was heard to remark to his Granny: "A canner can can anything that he can, But a canner can't can a can can he?" And finally, apt for this past weekend's Daylight Savings Time "spring forward" is an evocative sketch depicts a man hoeing up his back yard garden while a large sun shines brightly and reads "That extra hour of daylight." The sketch is captioned, "The best use of it!" "The War Garden Guyed" has 32 pages of verse, doggerel, short articles, and cartoons. Charles Lathrop Pack was correct when he said the newspapers evoked "gentle laughter" as none of the satirical sheets actually discourage gardening. Indeed, most of the text is directly in line with the propaganda of the day promoting the development of household war gardens and the movement to "put up" produce through home canning and drying. Many of the cartoons directly connect to the war itself, comparing fighting pests to fighting Huns, pesticides to ammunition and "trench gas," and equating canning and food preservation efforts with vanquishing generals. What the booklet does do is poke fun at all of the hardships and difficulties first-time or inexperience gardeners would face. Stray chickens, cabbage worms and potato beetles, dogs and children, competing spouses, naysaying neighbors, post-vacation forests of weeds, and trying desperately to impress coworkers and neighbors with first efforts. War gardens were no easy task, and there were plenty of people who felt that they were a waste of good seed. But Pack and the National War Garden Commission persisted. They believed that inspiring ordinary people to participate in gardening would not only increase the food supply, but also free up railroads for transporting war materiel instead of extra food, get white collar workers some exercise and sunshine, and provide fresh foods in a time of war emergency. How successful the gardens of first-year gardeners were is certainly debatable. But in many ways, war gardens were more about participating than food. After the war, Pack rebranded his "war gardens" as "victory gardens," asking people to continue planting them even in 1919. The idea struck such a chord that when the Second World War rolled around two decades after the first had ended, "victory gardens" and home canning again became a clarion call for ordinary people to participate in the war on the home front. The full "War Garden Guyed" has been digitized and is available online at archive.org. The Food Historian blog is supported by patrons on Patreon! Patrons help keep blog posts like this one free and available to the public. Join us for awesome members-only content like free digitized cookbooks from my personal collection, e-newsletter, and even snail mail from time to time! Don't like Patreon? Leave a tip! Last week we talked about the ice harvest during WWI, so I thought this week we would visit this amazing photo you've perhaps seen making the rounds of the internet. Housed at the National Archives, the title reads, "Girls deliver ice. Heavy work that formerly belonged to men only is being done by girls. The ice girls are delivering ice on a route and their work requires brawn as well as the patriotic ambition to help." Two fresh-faced White girls wearing generous overalls and shirts with the sleeves rolled up, their hair tucked under newsboy caps, strain with ice tongs to lift an enormous block of what appears to be natural ice. As the ice appears to be resting on the ground, it's unclear if this photo was posed or not. Large, irregular chunks of ice dot the road beside them, and the open back of an ice wagon is in the background. This photo is a perfect illustration of two major needs of the First World War colliding. One was the huge shift in labor that occurred during the war. With so many men conscripted to the fields of France, it fell to women to enter the workforce, including in fields that typically required "brawn" as well as "patriotic ambition." But while working in fields and factories is understandable to our modern concepts of labor, the idea of ice delivery is maybe not quite so easy to understand. Prior to the 1940s, the majority of Americans refrigerated their foods with ice. If you've ever heard your grandma call the refrigerator an "ice box," she's likely either experienced one, or the term has stayed in usage in her family enough for her to adopt it. An ice box is literally a box in which an enormous block of ice is placed at the top. The cold air and meltwater fall around the container below, in which perishable foods and beverages were placed to keep cool. Although not as cold as modern refrigerators (which hover at around 39-40 degrees F), ice boxes were considerably cooler than cellars and helped prevent meat and dairy products from spoiling, kept vegetables fresh, and even allowed for iced drinks. But, as you can see in the photo, the ice tended to melt fairly quickly. So new ice had to be delivered at least once a week. This colorized illustration from Harper's Weekly shows how the ice was delivered in New York City. It would be taken from enormous ice houses on the Hudson River, storing ice harvested in winter, loaded onto barges, which were towed by steamboats down the Hudson River to New York City, then unloaded from the barges onto shore (or onto transatlantic steamboats) and from shore onto innumerable ice wagons, which would then deliver for commercial or household use. The constant flow of deliveries - sometimes multiple times a day and by competing delivery companies - made for a very inefficient system, especially when it came to labor. Ice was not the only industry using inefficient deliveries - greengrocers, butchers, dry goods salesmen, and milk deliveries also competed with ice for road space and orders. The First World War's impact on labor and the Progressive Era's obsession with efficiency helped to reduce the number of delivery wagons (later trucks) and also the frequency of deliveries, especially to individual households. Nevertheless, efficiency could only go so far. People were still needed to do the labor, and these girls fit the bill. Ice delivery was not a nice trade - it was cold, wet, and often dirty. The work involved endless heavy lifting. Most ice men delivered ice by using the tongs to clamp down on the block (usually a sight smaller than the one they're handling in the photo), and then sling it over his shoulder, resting on a leather pad to protect his shoulder from frostbite. The frequent deliveries to women alone at home inspired jokes (and even songs) similar to the milkman jokes of the 1950s. Perhaps that was why these young women went into the ice trade in 1918? Regardless, the photo was taken in September, 1918, just a few months before Armistice. It is doubtful these young ladies continued in the trade as many women, especially those working in difficult or lucrative jobs, were almost immediately displaced by returning soldiers. I don't know how this photo was used in the period, but perhaps it was used much in the same way we react to it today - applauding the strength and grit of the women who proved they could do the same work as a man.

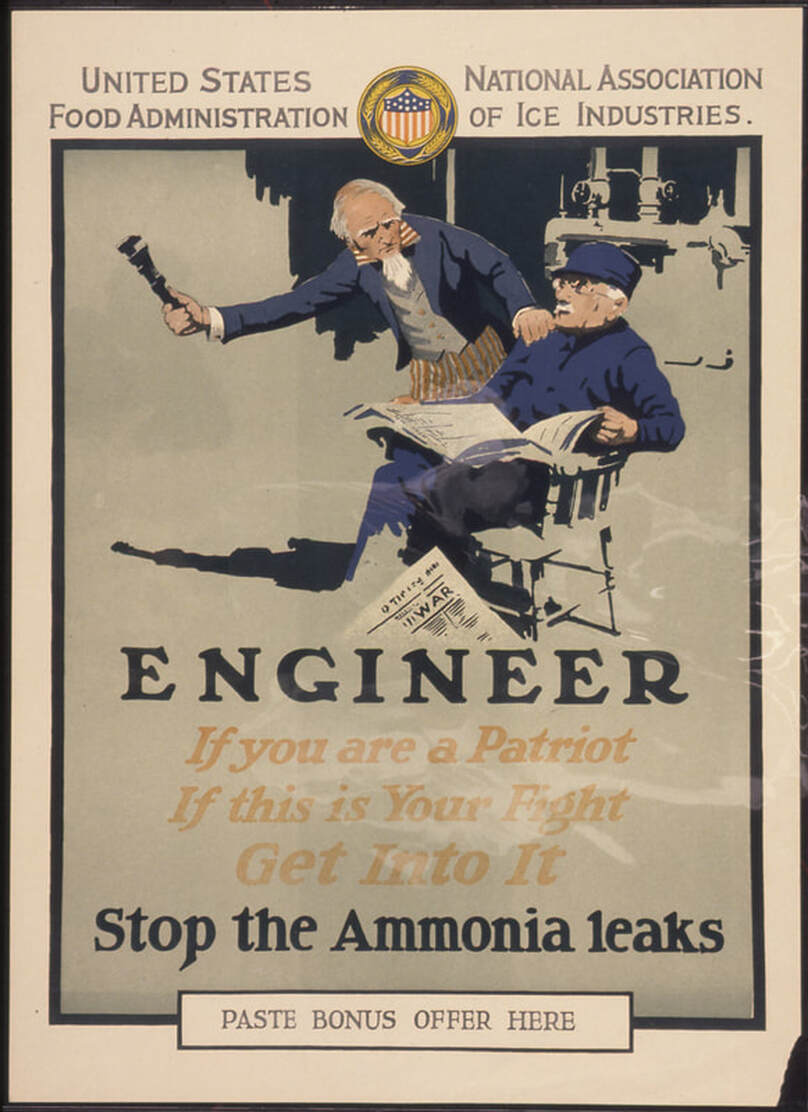

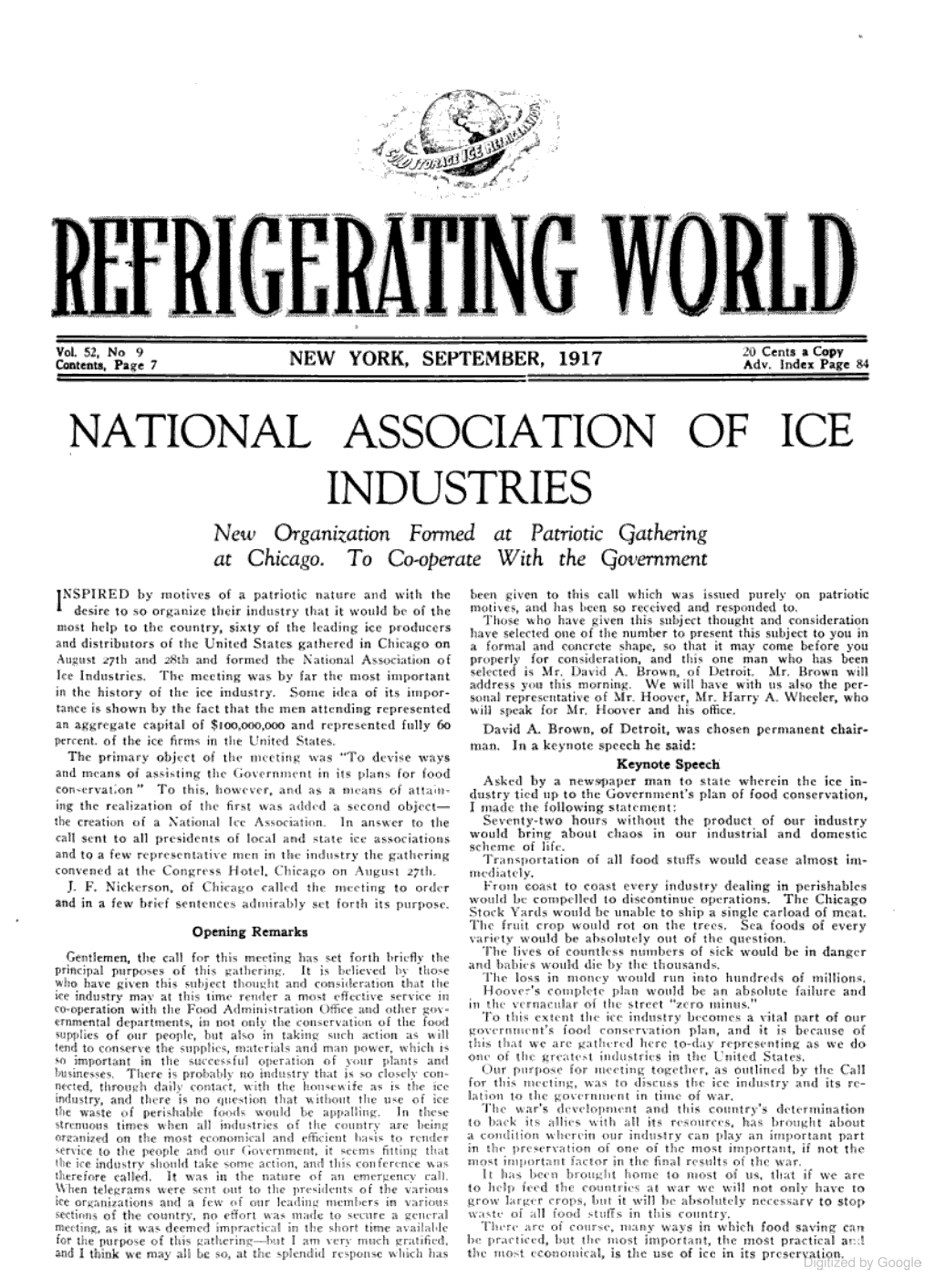

You may be wondering, what on earth do ammonia and engineers have to do with food history? Well, ammonia was one of the primary ingredients in creating artificial ice in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. The poster above shows Uncle Sam brandishing a wrench, hand on the shoulder of an older engineer, who reclines in a chair reading the newspaper. One sheet of the newspaper has fallen to the floor, and we can make out "War" in the headline. In the background we can see the outlines of pipes and valves. The poster reads "ENGINEER - If you are a patriot, If this is your fight, Get Into It - Stop the Ammonia Leaks." The top of the poster indicates it was sponsored by both the United States Food Administration and the National Association of Ice Industries. Refrigeration was changing rapidly in the 1900s. Most of the country still refrigerated with "natural ice," or ice harvested in winter from freshwater sources like lakes and rivers. But "artificial ice," that is water frozen mechanically, was gaining ground. Artificial ice making factories had been around since the 1870s, but they were costly and inefficient, used primarily in warmer climes where shipping natural ice was too inefficient. The primary refrigerant in these factories was ammonia, which has explosive properties. In fact, ammonia is a primary component in making gunpowder and explosives, and obviously demand for its use went up exponentially when the U.S. joined the First World War in April of 1917. Ammonia cools through compression. Jonathan Reese in Before the Refrigerator: How We Used to Get Ice (Amazon affiliate link) explains the process: The compression refrigeration cycle depends on the compressor forcing a refrigerant around a system of coils. A refrigerant is any substance that can be used to draw heat away from an adjoining space, but some refrigerants worked much better than others. During the late nineteenth century, most American refrigerating machines used ammonia as their refrigerant. The main advantage of ammonia was that it was very efficient. In other words, it has a very low vaporizing temperature (or boiling point) at which it will turn from a liquid into a gas. This means that it required less energy to propel it through the cycle and remove heat from whatever space or substance that the operator needed to become cold. If ammonia leaked through the pipes of these early machines (which it was prone to do), under certain circumstances it could even explode, as the New York packing house example described above illustrates.¹⁰ Most American refrigerating equipment manufacturers didn’t realize that until ammonia compression refrigeration systems had become extremely popular.¹¹ Cold storage also increased in use during the First World War, and refrigerated railroad cars, which helped drive agricultural specialization in fruits and vegetables around the country (Georgia peaches, Florida oranges, Michigan cherries, New York apples, and California's salad bowl), depended on ice for refrigeration and cooling. Ice was the invisible ingredient in the nation's food system. The National Association of Ice Industries was founded in August, 1917 in Chicago, IL as ice harvesters, producers, and distributors gathered at a conference. Realizing the importance of the ice trade in food preservation and conservation, the association vowed to cooperate with the government as part of the war effort. The conference proceedings were reported in Refrigerating World, the industry's trade journal, in the September, 1917 issue. In addition to forming the National Association of Ice Industries on the second day of the conference, the attendees also discussed convincing farmers of the benefits of cold storage and encouraging them to construct ice houses on their farms, of convincing the public that using ice and refrigeration would reduce food waste and save money, and finally of reducing inefficiencies in delivery, including advocating for one delivery service making one delivery per day to prevent competing delivery companies from wasting manpower, horsepower, and ice. Wartime not only necessitated the conservation of ammonia, but also gave the natural ice industry a boost. Already in decline due to concerns about polluted waterways, the natural ice industry was encouraged to revive as another way to conserve ammonia and the fuel that powered the steam engines and electric motors that powered the refrigerating process. The revival would ultimately be short-lived. The end of the First World War all but ended the natural ice industry. As refrigerants became abundant again and energy prices came back down, the demand for artificial ice went up. The advent of electric home refrigerators in the 1920s ultimately signaled the end of the household ice box, and the deliveries that went with it. Read More: The Amazon affiliate links below help support The Food Historian