|

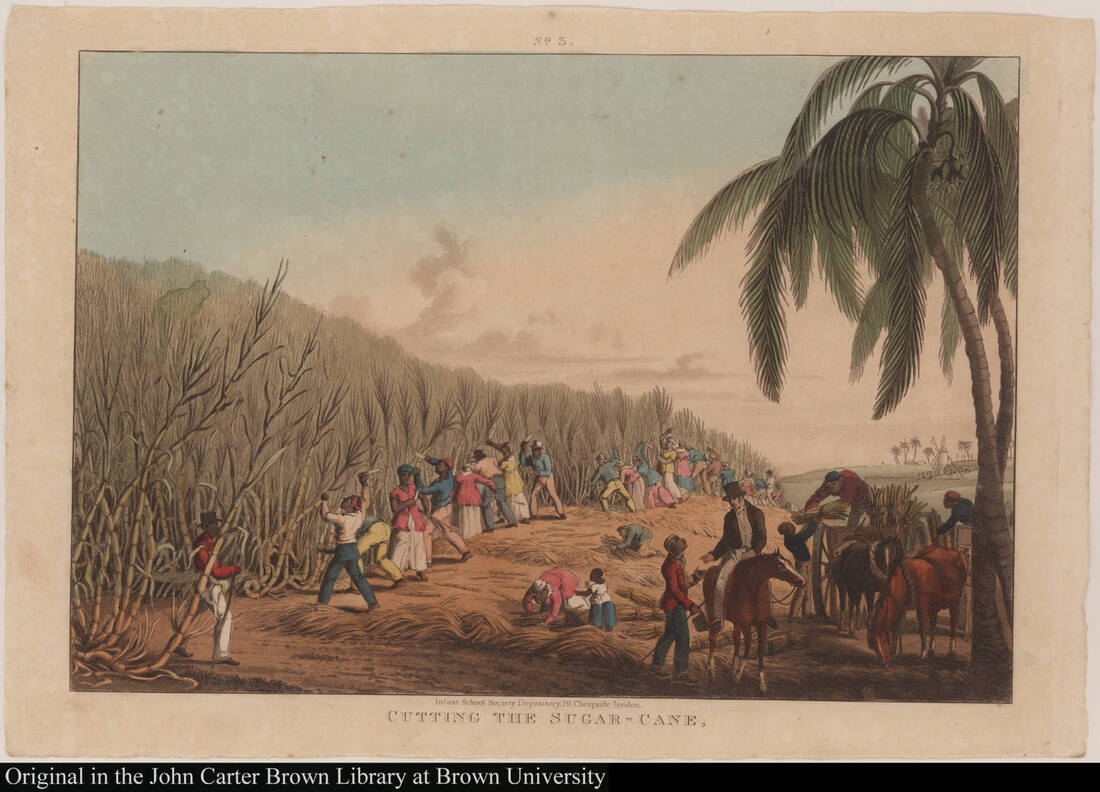

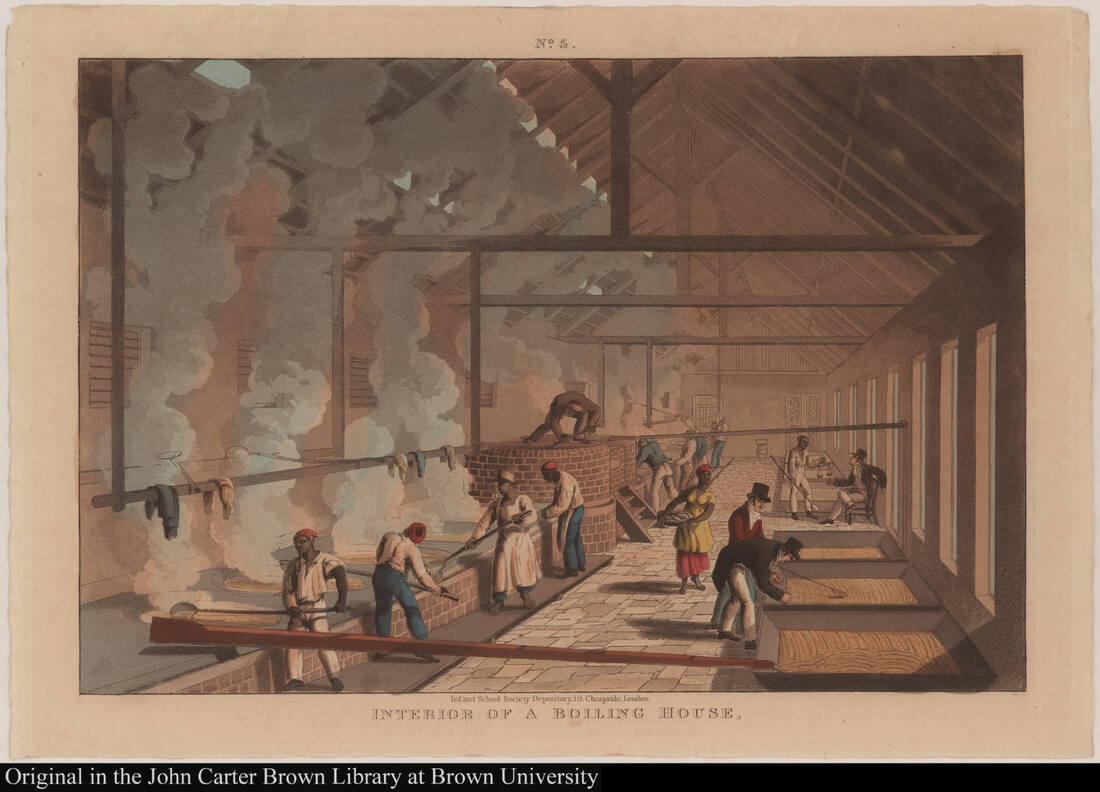

The United States owes enslaved people and their descendants a lot. White Americans don't like to admit that often, but we really do. And to me, nowhere is that more evident than in our modern food system. Today is Juneteenth - a celebration of the end of slavery in the United States. Not on the anniversary of the Emancipation Proclamation, which was issued on January 1, 1863 and which LEGALLY freed all enslaved people in the country. No, it took until June 19, 1865 - fully two and a half years later, for the message (and the enforcement) to finally arrive in Texas with a group of Union soldiers. For although all enslaved people in the United States were deemed free in 1863, the Confederacy did not recognize that authority, and continued to enslave and exploit Black people until forced to do otherwise by armed Federal troops. So to celebrate Juneteenth, you can certainly look up recipes and plan a party. But I think it's equally important to recognize incredible contributions enslaved people made to our food system, and for Americans of all backgrounds to reckon with the truth that much of our modern foods are the direct result of violence and exploitation. At last night's Food History Happy Hour, viewer Cathy brought up that we learn a lot in school about the contributions of White immigrants, but not so much about the contributions of enslaved people. And that struck me as both very true and very sad. Because so much of what is considered American food is intimately connected to both West Africa and the enslaved people brought here against their wills. People who experienced incredible hardship still had the perseverance and fortitude not only to hold on to their foodways on the horrific voyage across the Atlantic, but to persist in keeping those foodways in the United States. Not all of the foods listed below came from West Africa, but all are a direct result of the enslavement of West Africans. Editor's note: The Food Historian is an Amazon affiliate. Any purchases you make through the book links below will help support blog posts like this! SugarWe can start with the biggest one. Before the enslavement of Africans in the Caribbean and American South, sugar was produced in India at great expense. By kidnapping people and forcing them into bondage, enormous sugar plantations were established by Europeans throughout the Caribbean, and later in American states like Louisiana. Sugar plantations were some of the most brutal of the plantation economy. The life expectancy of an enslaved person was very low, and some islands imported double or triple their populations per year in slaves, as many died faster than they could be replaced. Today, sugar is almost completely mechanized, but most of our modern foodways - sugary desserts in particular - are possible only through the massive effort to enslave millions of people for profit. Throughout the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, sugar became increasingly affordable, as sugar production mechanized. The cultivation of sugarcane remained incredibly labor-intensive. Sugarcane harvesting, for example, was not really mechanized in the American South until World War II. As an aside, I recently learned that the United States was active in the slave trade for decades after it was made illegal, and that the primary point of destination for American slave traders after kidnapping mostly children from West Africa was the sugar plantations of Cuba. This illegal trade continued until the 1860s. Further Reading:

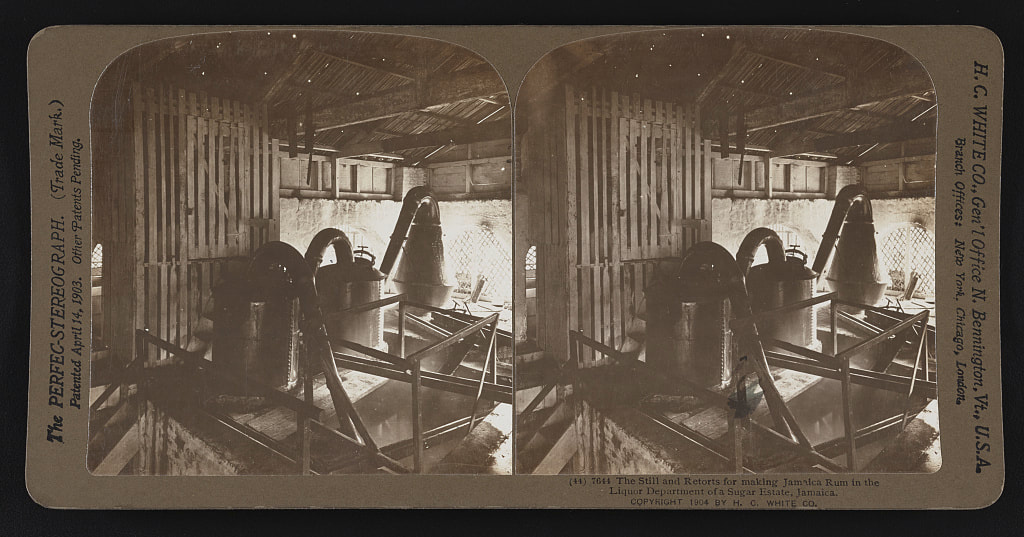

MolassesMolasses may make you think of baked beans, or gingerbread, or soft molasses cookies. But molasses is a byproduct of the sugar industry, and therefore slavery. Molasses, the cheapest sweetener, also was used in slave rations and was a major foodstuff among poor Whites throughout the United States until the mid-20th century. But although Molasses becomes intimately connected with New England and pioneer foodways, it has another important use... RumRum may make you think of pirates, but it was actually developed as a way to transform relatively worthless molasses into a high-value commodity. And while vicious pirates guzzled it by the gallon, it was also a huge economic engine not only in the Caribbean, but also in New England, where it was produced and used to purchase people and goods in West Africa as part of the slave trade. The irony being that a product largely produced by slaves (first in producing the molasses, and then often again in producing rum) was being used to purchase more slaves should not be lost on anyone. Further Reading:

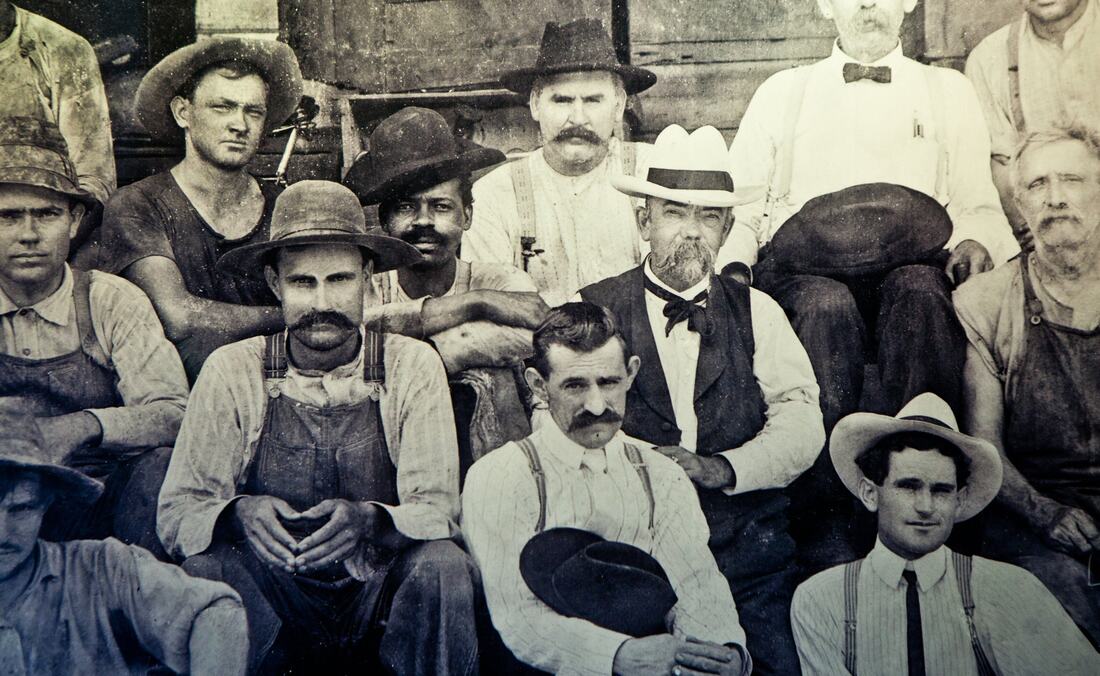

Jack Daniels WhiskyWhile we're on the topic of alcohol and slavery, let's just take a moment to recognize that Jack Daniels was taught how to make whisky by Nathan "Nearest" Green, an enslaved man who used a charcoal filtering technique he learned to clean water in West Africa to filter the distilled alcohol. He was Jack Daniel's first master distiller, but only got credit more recently. Read the full story. RiceI know what you're thinking - Sarah, how are you going to relate RICE to slavery? Well, although today we consume a lot of rice developed in India and Japan, throughout the 19th century, Carolina Gold rice was king. Rice production in South Carolina dates back to the 18th century and plantation owners specifically sought out and captured West Africans skilled in rice agriculture and enslaved them to operate their rice plantations. The White plantation owners got obscenely rich on this scheme. Although Carolina Gold rice is no longer as prevalent in American food culture, it still made a huge impact on the economy of the South. Further Reading:

OkraNative to Ethiopia and cultivated in Africa as early as 12,000 years ago, okra was brought to North America by enslaved West Africans, the seeds braided in their hair. It went on to spread throughout the American South, influencing such dishes as regional varieties of gumbo and often served stewed with tomatoes or breaded and fried. Although not as widespread as some of the other foods on this list, okra still maintains a huge impact on American foodways. Further Reading:

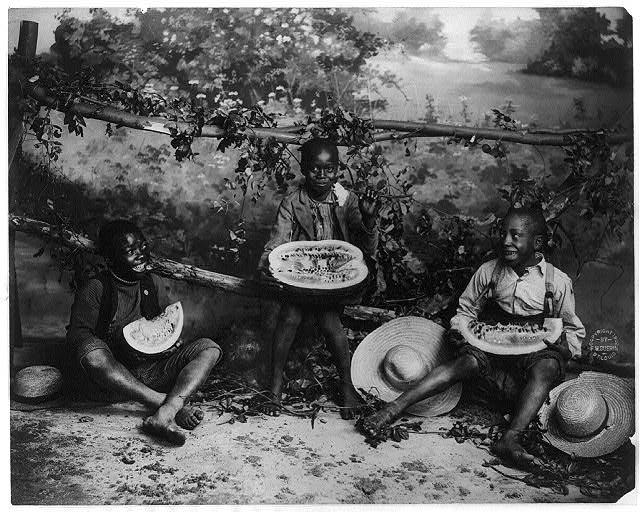

WatermelonDeveloped in the Kalahari desert of Africa, the watermelon was carefully bred by Indigenous Africans to go from a thick-rinded, rather tasteless melon to the sweet, juicy treat we know today. Although it did spread to Egypt and the Middle East, it was likely introduced to North America via the slave trade - either purchased by slave traders and kidnappers, or brought over by enslaved people themselves. The American stereotype of associating Black folks with watermelon as an insult is still around today. Further Reading:

Black Eyed PeasNative to West Africa, black eyed peas, sometimes called cowpeas, were brought to the Americas by enslaved Africans. In the U.S. they are most commonly known as the main ingredient in "Hoppin' John," a popular dish consumed on New Year's Day for good luck. Two stories about black eyed peas and luck have emerged over the years. The first is that when General Sherman made his way through Georgia, one of the only foods the Union Army did not take was black eyed peas, as they were considered cattle fodder in the North. The Confederate Army subsisted on this "slave food," an irony they clearly did not understand. The other story, and one I think far more likely, is that black eyed peas were one of the celebratory dishes consumed on January 1, 1863 - the day the Emancipation Proclamation became law. Further Reading:

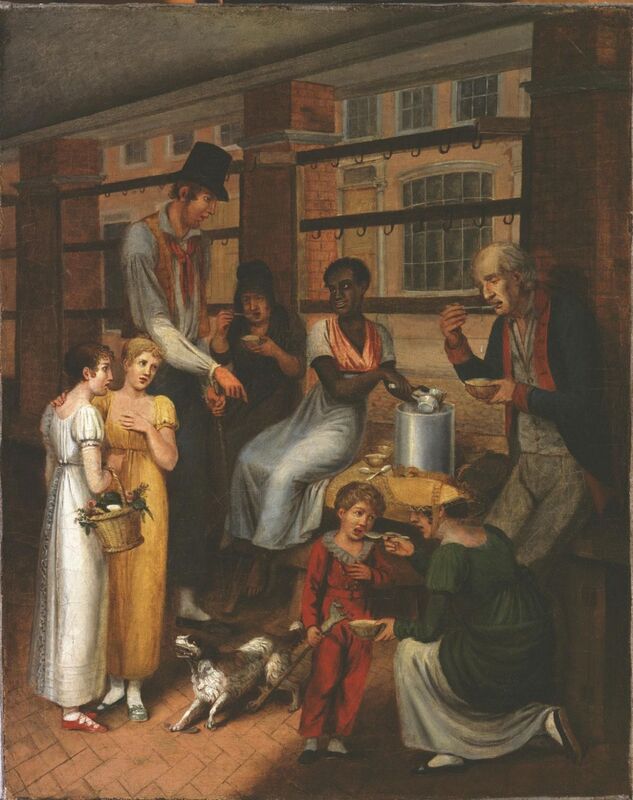

Philadelphia Pepper Pot SoupAccording to Tonya Hopkins, The Food Griot, Philadelphia Pepper Pot Soup, a favorite dish of George Washington, is quintessentially West African in style, including the addition of a whole hot pepper to flavor the soup. It was popularized as a street food in Philadelphia by Black women like the one pictured here. In the 20th century it was commercialized for a brief time by Campbell's, but its popularity waned by the late 20th century. Today, some chefs are reviving the food tradition. Further Listening:

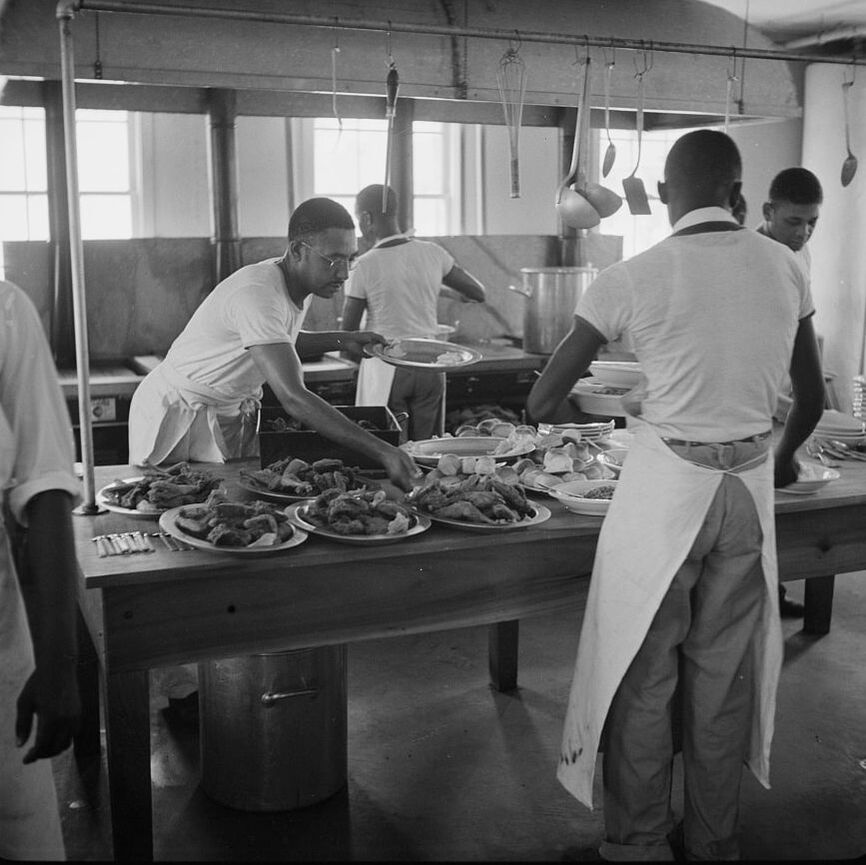

Fried ChickenAlthough who really brought fried chicken to the Americas is disputed (did it come from Africa, Scotland, or some confluence of the two?), by the late 18th century fried chicken is indisputably tied to the South and enslaved cooks. A special-occasion dish that, following the American Civil War, became a real source of income for freed people and their descendants, fried chicken became emblematic of soul food in the 20th century. Further Reading:

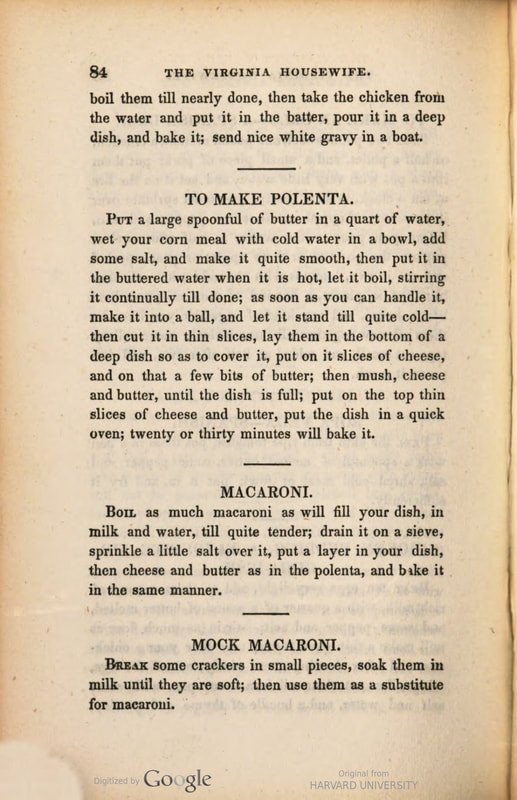

Macaroni and CheeseIs there a more quintessentially American food than macaroni and cheese? It has surprising origins, but was popularized early in American history thanks largely to an enslaved man - James Hemings, Thomas Jefferson's enslaved chef de cuisine. Its popularity among Black Americans is almost certainly due to the long history of macaroni and cheese in Southern (and mostly black-staffed) kitchens. Its use in railroad dining cars staffed by Black cooks also helps popularize it with Americans of all backgrounds. Further Reading:

Obviously, this is not a complete list, but I hope you learned a little something new with this post. As we all celebrate Juneteenth, let's not forget to keep recognizing the contributions of enslaved people and their descendants in contributing significantly to American food and culture throughout our nation's history. Want to learn more? Check out last year's "Black Food Historians You Should Know" for even more further reading. The Food Historian blog is supported by patrons on Patreon! Patrons help keep blog posts like this one free and available to the public. Join us for awesome members-only content like free digitized cookbooks from my personal collection, e-newsletter, and even snail mail from time to time! Don't like Patreon? Join with an annual membership below, or just leave a tip! Join on Patreon or with an annual membership by June 30, 2020 and get a picnic history packet mailed to your door!

1 Comment

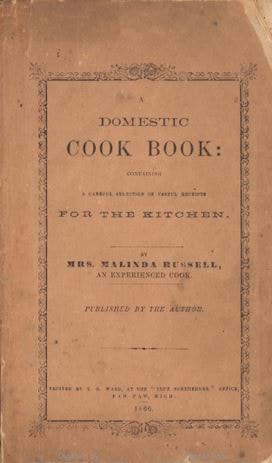

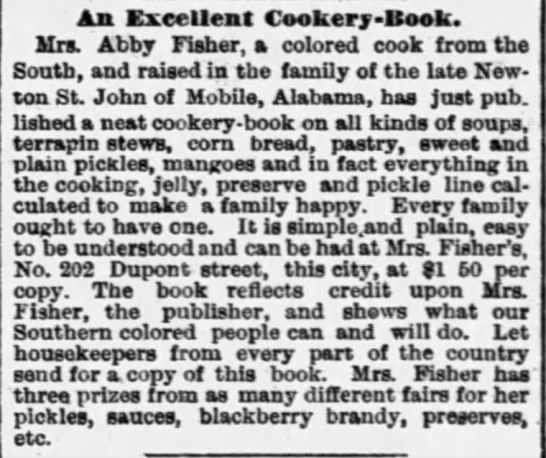

Throughout the 19th century, white women used their domestic assets to pick up the slack left by disabled or deceased husbands - homes became boarding houses and tea rooms and domestic skills were translated into magazine articles and cookbooks. But free Black women in the 19th century did not have as many assets. And even when they did, these assets were often taken from them, and a racist and sexist judicial system gave them little recourse to recover property. Enslaved women freed by the Emancipation Proclamation had their freedom, but little else. The promised 40 acres and a mule never materialized. Despite these often difficult starts, many free and formerly enslaved women of color used their wits and skills to make their own way in the world. Often relegated to service jobs in households, many women created their own small businesses to avoid working for wages - tea rooms, boarding houses, laundries, seamstress and millinery shops, catering, etc. Most of these jobs had low startup costs and could be done from home, allowing for the care of children and family members. Many women also worked as professional cooks for taverns and hotels, a job that held more promise of profit and respect than working in a private household. The vast majority of women working in these fields remain hidden from history - unnamed and un-written-about. But some women of color have managed to make their mark on food history. Here are a few of their stories. Anne Northup - Twelve Years AloneAnne Northup was my first real encounter with the stories of adversity and perseverance many Black women faced throughout the 19th century. I attended a special program at the Morris-Jumel Mansion in New York City with a historic dinner recreated by The Food Griot - Tonya Hopkins. Anne Hampton was born in 1808 in upstate New York. A free woman of color, she married Solomon Northup in the 1820s and in 1834 they sold their farm and moved to Saratoga. Solomon often worked as a fiddler and Anne worked as a cook and kitchen manager at hotels in the spa resort town. She was working at the Pavilion Hotel in Saratoga when she met wealthy white New Yorker Eliza Jumel in 1841. Divorcee/widow of Aaron Burr, Madame Jumel convinced Anne to come south and serve as a cook in her household. Anne sent her eldest daughter Elizabeth to Manhattan with Jumel, but waited until later in the year to come south herself, likely finishing out the busy tourist season. Earlier that summer of 1841, Anne's husband Solomon had answered an advertisement looking for musicians for a job in Virginia. An accomplished violinist, Solomon had answered the advertisement and traveled south. He was captured and sold into slavery, spending the next twelve years enduring brutal conditions on a Louisiana sugar plantation. Anne was left to fend on her own. After a year in Eliza Jumel's household, Anne and some (but not all) of her children returned to Saratoga, where they stayed until 1850, when they moved to Glens Falls and Anne continued her hotel work. They were not reunited with Solomon until 1853. He wrote a book about his experiences - Twelve Years a Slave. We lose track of Solomon Northup in the 1860s and his death date is unknown, although Anne and her children continue to live in New York. To learn more about the Northup family, read this excellent account by historian David Fiske. Anne Northup died on August 8, 1876 in Moreau, New York. Although she leaves behind no documentation of the food she cooked, given her positions in fashionable resort town hotels and wealthy households, she was likely very skilled in a variety of foodways. To me, she represents how many free women of color made their way in the world on the strength of their cooking skills, even in the face of extraordinary adversity. Malinda Russell & Her Union PrinciplesIn 2000, Jan Longone ran across a slim, crumbling cookbook wrapped in brown paper at the William L. Clements Library at the University of Michigan in Ann Arbor, where she is curator of American culinary history. That cookbook, A Domestic Cookbook, published in 1866 by a woman named Malinda Russell, turned out to be the earliest known cookbook published by an African American woman. The cookbook has since been digitized, and when I read it for the first time the other day, I was struck by the incredible hardship Russell had to overcome in her life. In the autobiographical account that explains why she wrote the cookbook, Russell recounted the many setbacks in her life. Born free in Tennessee, at age 19 she set out to emigrate to Liberia, a promise of life free from the racism and oppression that continued to plague free Black communities in the North. But along the way, she was robbed by someone from her party, and was forced to stay in Virginia, where she made a living as a cook and a nurse. There, she married Anderson Vaughn, and they had a son together, but Vaughn died just four years later, leaving Russell a widow with a handicapped son. She moved back to Tennessee and opened a boarding house in a town that featured springs as a tourist attraction. She later opened a pastry shop in that same down and had saved up a sum of money to support herself and her son. But in early 1864, she was attacked and robbed by a "guerrilla party," likely Confederate soldiers. She and her son fled Tennessee during the height of the Civil War. Although Tennessee was a Union state, its proximity to the border meant it was not safe for Russell. She made her way to Michigan, enduring several attacks along the way, and went on to start over, again, in a new state. In May, 1866, she published A Domestic Cookbook. She closed her introduction stating that she hoped the sale of the cookbook would help her raise funds to return to Tennessee and reclaim some of her lost property when peace was restored. We do not know if she ever made it home to Tennessee, or really much else about her at all, although Jan Longone has worked to find more about her. According to Russell herself, "I have learned my trade of Fanny Steward, a colored cook, of Virginia, and have since learned many new things in cooking." She also indicated her cookbook was organized along the lines of Mary Randolph's The Virginia Housewife (1824). Malinda Russell reset much of the conventional wisdom about Black cooking heritage at the time it was rediscovered. But her cookbook is not much different from any other cookbook of the period - reflecting her experience as a boarding house owner and cook, cooking for the public and likely for audiences diverse in race and socioeconomic status. It also knows its audience, consisting largely of dessert and preserves recipes. These were commonly featured in published cookbooks because they were more complex than the everyday cooking of meat and vegetables and less likely to be familiar to ordinary cooks. Her cookbook contains everything from the humble "Baked Indian Meal Pudding" and 'Sliced Sweet Potato Pie," to the exquisite "Floating Islands" and "Charlotte Russe." For me, the most striking thing about Russell is not the content of her cookbook, but rather the fact that it exists at all - a testament to her difficult life and the grit she used to persevere. What Abby Fisher Knew "Pickles and Fruit. The purest home-made Pickles and Preserves of all kinds, put up in the good old Southern style. A liberal discount to the trade. Address, Mrs. Abbey Fisher and Husband, 569 Howard St. San Francisco." Advertisement from the December 13, 1879 issue of "The Placer Herald," published in Rocklin, CA. Unlike Anne Northup and Malinda Russell, Abby Clifton was born into slavery in 1831 in South Carolina to a white father and an enslaved mother. It is unclear when gained her freedom, but by 1860 she had moved to Alabama and married Albert Fisher. In 1877, they emigrated to California and by 1880, Abby and Albert were in San Francisco, where the 1880 Census listed Abby as a "cook" and Albert as a pickle and preserve manufacturer. But this attribution was likely due to sexism common among census takers. In reality, it was Abby who was manufacturing pickles and preserves - as listed in an 1882 San Francisco directory. Albert was listed as a porter. Abby leveraged her expertise in pickles and preserves to reach the highest echelons of San Francisco society. She was awarded a diploma at 1879 Sacramento State Fair. At the 1880 San Francisco Mechanics Institute Fair, she won a bronze medal for her pickles and preserves. Although she and Albert could not read or write, in 1881 she published the cookbook, What Mrs. Fisher Knows About Old Southern Cooking, Soups, Pickles, Preserves, Etc. with assistance from white friends who helped her translate and transcribe her memorized recipes into cookbook format. The book does not contain just pickles and preserves, although they and her famous blackberry cordial certainly make a showing. The title inclusion of "Old Southern Cooking" is certainly apt, given recipes for "Maryland Beat Biscuit," "Plantation Corn Bread," "Ochra Gumbo," "Creole Chow Chow," "Sweet Potato Pie," and "Peach Cobbler." But it also includes typical British-American foods popular in the Northeast and throughout the United States, including "Sally Lund" bread, "Jumble" cookies, "Sauce for Suet Pudding," "Rhubarb Pie," (rhubarb grows poorly in the South, needing below freezing temperatures), three different kinds of "Sherbet," "Yorkshire Pudding," and "Terrapin Soup." In short, her cooking is more representative of broad American style cooking of the period, with some Southern flavor, rather than stereotypically "Southern" (i.e. Black) cooking. The interest in Southern cooking, as evidenced by the marketing of her book, was likely part of a reaction to the Civil War and Reconstruction. Historian Megan Elias has written about "Lost Cause cookbooks" in which white Americans romanticized the "good old days" of slavery and subservient Black folks with "magic" cooking skills. It is possible that Abby Fisher's cookbook was swept up in the wave of racist nostalgia. But it is also possible that Abby's cookbook was simply a reflection of the interest in California residents in the cuisines of many newly arrived emigrants of all cultures and backgrounds. This seems to be the case in one announcement, published in the San Francisco Examiner on July 11, 1881. It reads: "An Excellent Cookery-Book. "Mrs. Abby Fisher, a colored cook from the south, and raised in the family of the late Newton St. John of Mobile, Alabamaa, has just published a neat cookery-book on all kinds of soups, terrapin stews, corn bread, pastry, sweet and plain pickles, mangoes and in fact everything in the cooking, jelly, preserve and pickle line calculated to make a family happy. Every family ought to have one. It is simple and plain, easy to be understood and can be had at Mrs. Fisher's, No. 202 Dupont street, this city, at $1.50 per copy. The book reflects credit upon Mrs. Fisher, the publisher, and shows what our Southern colored people can and will do. Let housekeepers from every part of the country send for a copy of this book. Mrs. Fisher has three prizes from as many different fairs for her pickles, sauces, blackberry brandy, preserves, etc." Although we may never know how many copies Abby sold, the cookbook seemed to garner positive reviews. For several weeks in 1881, she (or the publisher) advertised it in the Oakland Tribune (see below).  "Mrs. Abby Fisher's, Southern Cookery book on soups, terrapin stews, sweet and plain pickles, mangoes, preserves, corn bread; price $1.50; 202 Dupont st., San Francisco. jy11-1m." Advertisement for Mrs. Fisher's cookbook in the "Oakland Tribune," published July 11, 1881, but running for several weeks prior and after. In the 1890 San Francisco directory, "Mrs. Abbie Fisher" was still listed as "mnfr. pickles and preserves," but it is unclear what happened after that. Her exact death date is also unknown. No known obituary was published. After the Great San Francisco Fire of 1907, reference to Abby and her cookbook all but disappeared until a copy surfaced in 1984 at a Sotheby's auction in New York City. The Schlesinger Library purchased it and at the time it was thought to be the first cookbook published in the United States by a Black woman, until Malinda Russell toppled Abby from her throne in 2000. Like Malinda and Anne, Abby used her cooking skills to make her own way in the world - supporting her family and showcasing her talents. Ghosts in the KitchenOf course, we know about these women because they left a written record. We know about Anne through her husband Solomon and his memoir, Twelve Years a Slave and the records of Eliza Jumel. We know about Malinda because of her cookbook and the autobiography she includes in it. And we know about Abby because of her cookbook and her existence in newspapers and city directories. But there were tens of thousands of women of color making their own way on the strength of their culinary skills, just like these women, throughout the 19th and 20th centuries. Ashbell McElveen called James Hemings the "ghost in America's kitchen," but he wasn't the only one. Enslaved women and men shaped American food profoundly. And women of color - enslaved, freed, and born free - left their mark as well. Because I know how history works, I am hopeful that more records and cookbooks of cooks of color - published or not - will continue to show up in the coming decades. And when they do, I know they'll help us better understand how our food got to be the way it is, and where it can go in the future. Further ReadingAnne Northup:

Malinda Russell:

Abby Fisher:

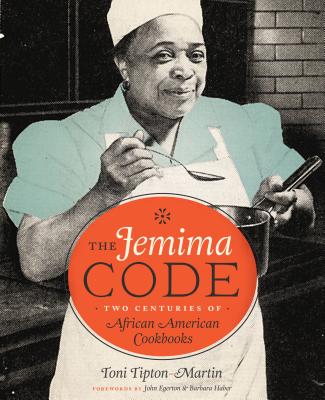

The Jemima CodeThe Jemima Code: Two Centuries of African American Cookbooks, Toni Tipton Martin. University of Texas Press, 2015. ISBN 0292745486. This article contains Amazon.com and Bookshop.org affiliate links. If you purchase anything from these links, The Food Historian will receive a small commission. If you want to know more about African American cookbooks, I recommend Toni Tipton Martin's The Jemima Code: Two Centuries of African American Cookbooks. Although the information for each entry is sadly quite brief, it is nonetheless an important, enlightening, and beautifully produced catalog of all the known cookbooks authored by African Americans (real and fictional) in the United States. The Food Historian blog is supported by patrons on Patreon! Join us for awesome members-only content like free digitized cookbooks from my personal collection, e-newsletter, and even snail mail from time to time! |

AuthorSarah Wassberg Johnson has an MA in Public History from the University at Albany and studies early 20th century food history. Archives

July 2024

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed