|

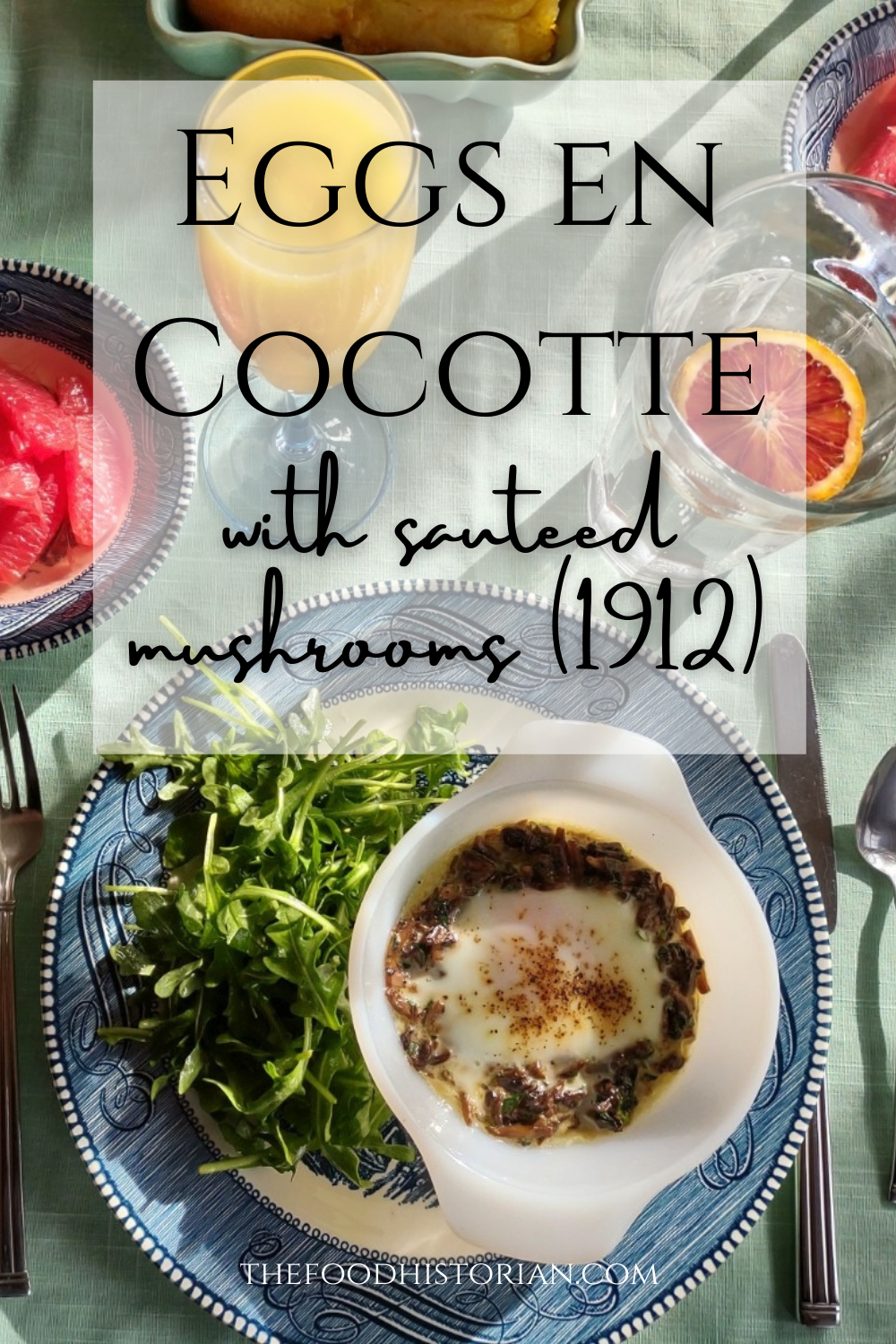

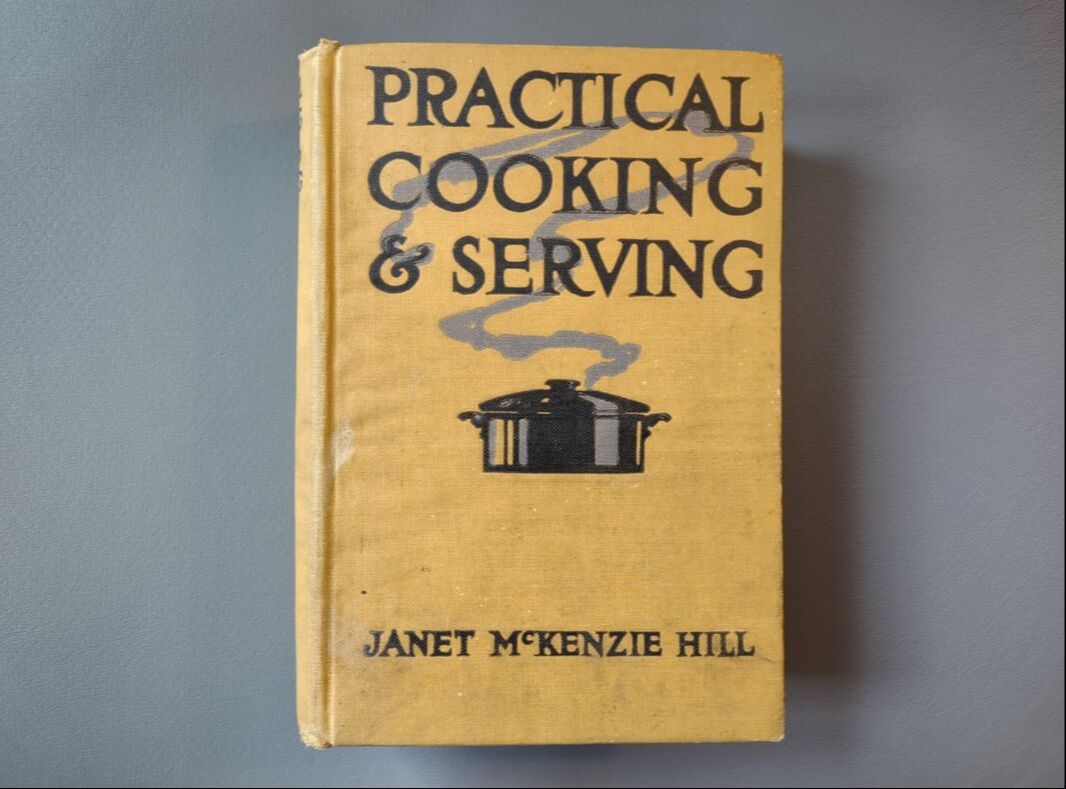

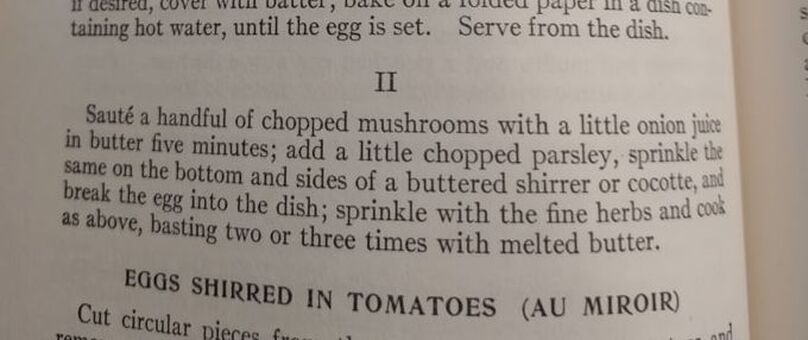

I love brunch. Not the kind you wait in line for, crowded and busy and loud. I love brunch made at home. It's as quiet or loud as you want it to be, the service is usually pretty good, and while there's the effort of making food, if you play your cards right, it's always hot when it gets to the table, and hopefully someone else will do the washing up. Eggs have long been a breakfast staple. If you've a hot skillet, they cook up in a flash. And if you keep chickens, you have a fresh supply every day, at least during the warmer months. But getting a bunch of eggs hot and cooked to order to the table can be a precarious thing when you're hosting. So I took to my historic cookbooks and found a viable solution - eggs en cocotte. Technically, it's oeufs en cocotte, which is French for eggs baked in a type of dish called a cocotte, which may or may not have been round, or with a round bottom and/or with legs. Sometimes also called shirred eggs, which are usually just baked with cream until just set, these days en cocotte generally means the dish spends some time in a bain marie - a water bath. The cookbook recipe I used was from Practical Cooking & Serving by prolific cookbook author Janet McKenzie Hill. Originally published in 1902, my edition is from 1912. You can find the 1919 edition online for free here. A weighty tome of a book, Practical Cooking and Serving is nothing if not practical, and McKenzie Hill is uncommonly good at explaining things. Her section on eggs explains: "Eggs poached in a dish are said to be shirred; when the eggs are basted with melted butter during the cooking, to give them a glossy, shiny appearance, the dish is called au mirroir. Often the eggs are served in the dish in which they are cooked; at other times, especially where several are cooked in the same dish, they are cut with a round paste-cutter and served on croutons, or on a garnish. Eggs are shirred in flat dishes, in cases of china, or paper, or in cocottes. A cocotte is a small earthen saucepan with a handle, standing on three feet." Since my baking dishes were neither the flat oval shirring dishes, nor the handled kind, I guess perhaps they are neither shirred nor en cocotte, according to Hill, but we can afford to be less picky about our dishware. Hill offered two recipes: one more classic version with breadcrumbs (optional addition of chopped chicken or ham) mixed with cream "to make a batter." The buttered cocotte was lined with the creamy breadcrumbs, the egg cracked on top, with the option to cover with more breadcrumb batter. The whole thing was then baked in a hot water bath "until the egg is set." My brunch guest adores mushrooms, and I wanted something a little fancier and more substantial, so I went with Hill's version No. II. Eggs en Cocotte with Sauteed Mushrooms (1912)Hill's original recipe reads: Sauté a handful of chopped mushrooms with a little onion juice in butter five minutes; add a little chopped parsley, sprinkle the same on the bottom and sides of a buttered shirrer or cocotte, and break the egg into the dish. Sprinkle with the fine herbs and cook as above, basting two or three times with melted butter. I will admit I didn't follow the directions as closely as I should have - I didn't use hot water in my bain marie (oops), and I didn't baste with butter. So the eggs were cooked a little more solid than I would have like, but still turned out deliciously. Here's my adapted recipe: 1 pint white button mushrooms, minced 2 tablespoons butter 1 clove minced garlic salt and pepper 2 tablespoons heavy cream 2 tablespoons fresh flat leaf parsley, chopped 4 eggs Preheat the oven to 350 F. Butter three or four small glass baking dishes. Sauté the mushrooms and garlic in butter, adding salt and pepper to taste. When most of the mushroom liquid has cooked off, add the heavy cream and parsley and stir well. Divide evenly among the baking dishes, make a little well, and then crack eggs into dishes. One or two per dish. Salt and pepper the egg, then place in a 9x13" baking pan with two inches of water (use hot or boiling water). Bake 5-10 minutes, or until the egg white is set and the yolk still runny. For firmer eggs, bake 10-15 mins. I did not use boiling water, so the whole thing took more like 20-30 mins for the water to heat up properly, and the yolks got firmer than I would have liked. Tasted delicious, though! This is a very rich dish, so best served with something green and piquant - I chose baby arugula with a sharp homemade vinaigrette (2 tablespoons olive oil, 2 tablespoons lemon juice, 1 tablespoon dijon mustard was enough for 3 or 4 servings of salad), which was just about perfect. You don't have to be a fan of mushrooms to like this dish - white button mushrooms aren't particularly strong-flavored - they just tasted rich and meaty. And despite the fact that eggs en cocotte look and taste incredibly fancy, they were very easy and relatively fast to make. If you were cooking brunch for a crowd, you could certainly prep the mushroom mixture in advance, have the bain marie water on the boil, and make the eggs your last task for a beautiful brunch. With the simple arugula vinaigrette on the side, something sweet and bready (that recipe is coming soon, too) and some fresh fruit and mimosas, you've got yourself a winner. Do you have a favorite egg recipe? The Food Historian blog is supported by patrons on Patreon! Patrons help keep blog posts like this one free and available to the public. Join us for awesome members-only content like free digitized cookbooks from my personal collection, e-newsletter, and even snail mail from time to time! Don't like Patreon? You can leave a tip!

0 Comments

It's no secret that my husband and I love pancakes. Like a lot. I've adapted a single recipe endlessly - apple cinnamon oatmeal pancakes, black forest pancakes, whole grain pancakes, pear ginger pancakes, gingerbread pancakes, almond pancakes, blueberry pancakes - you name it. But I think pumpkin pancakes are one of our very favorites. This is definitely a recipe for your days off, in large part because making pancakes is time consuming, but also because this is a huge recipe and makes approximately 30 pancakes. But Sarah! you might be thinking, how can two people eat 30 pancakes in one sitting? Well, dear reader, we can't. However, these pancakes are absolutely delicious as leftovers, staying tender even days later. You can pop them in the toaster for a reheated morning treat, or eat them cold as a snack. You can make them into a sandwich with butter and fig jam, or cover them in whipped cream (my husband's favorite). Pumpkin pancakes are one of those things you'll never regret having too many of. And if you've got a big family or are having a crowd for brunch? They're perfect. And don't worry, I've got tips for hot to keep the pancakes piping hot while you cook. Whole Can Pumpkin Pancakes RecipeThis recipe is about triple the original Joy of Cooking recipe I've adapted endlessly over the years. So feel free to cut it in half. But then it won't use a whole can of pumpkin. You can also cut back on the butter too, if you like, or substitute some vegetable oil. 4 1/12 cups flour (you can sub up to 2/3rds whole grain flour) 1/2 cup sugar 4 teaspoons baking powder 3 teaspoons salt 1-2 teaspoons pumpkin spice and/or cinnamon 3 eggs 1 stick (1/2 cup) melted butter 1 can (16 oz.) pureed pumpkin 3 1/2 - 4+ cups milk Preheat your griddle over medium heat. If using cast iron, grease it lightly. I prefer to use an electric griddle which can handle 5-6 pancakes at a time. I set the control to 350 F and let it preheat. Whisk the flour, sugar, baking powder, salt, and spices together until well blended in a VERY large bowl. In a separate bowl, whisk the pumpkin, eggs, and butter to combine, then add to the dry ingredients. Add 3 cups milk and whisk, incorporating the flour slowly, add more milk as necessary to make a smooth, lump-free batter. Using the measuring cup you used to add the milk, pour the batter in about 1/3 cup amounts onto the griddle. When bubbles form near the center of the pancake, flip and let brown on the other side. Now for the savvy tip taught to me by my mother. Use a dish towel to keep your pancakes hot! Using a flat-weave dish towel, place one end on the plate you're using to pile the pancakes, and leave the long tail to cover them. Add the pancakes in an overlapping circle and keep covered by the towel in between. The towel combined with the pile of the pancakes themselves will keep everything piping hot until it's ready to go to the table. Serve with butter, real maple syrup, and whipped cream for a decadent brunch. Let the leftovers cool to room temp and store in a closed container to keep them from drying out. They will keep at room temp for a few days, so if you don't plan to eat them right away, refrigerate or freeze for future use. A third cup of batter will make a pancake small enough to fit inside a conventional toaster, should you want to reheat them. I hope you enjoy these pancakes as much as we do. I'm off to eat one as a snack before heading out to do some grocery shopping. Happy eating! The Food Historian blog is supported by patrons on Patreon! Patrons help keep blog posts like this one free and available to the public. Join us for awesome members-only content like free digitized cookbooks from my personal collection, e-newsletter, and even snail mail from time to time! Don't like Patreon? Join with an annual membership below, or just leave a tip!

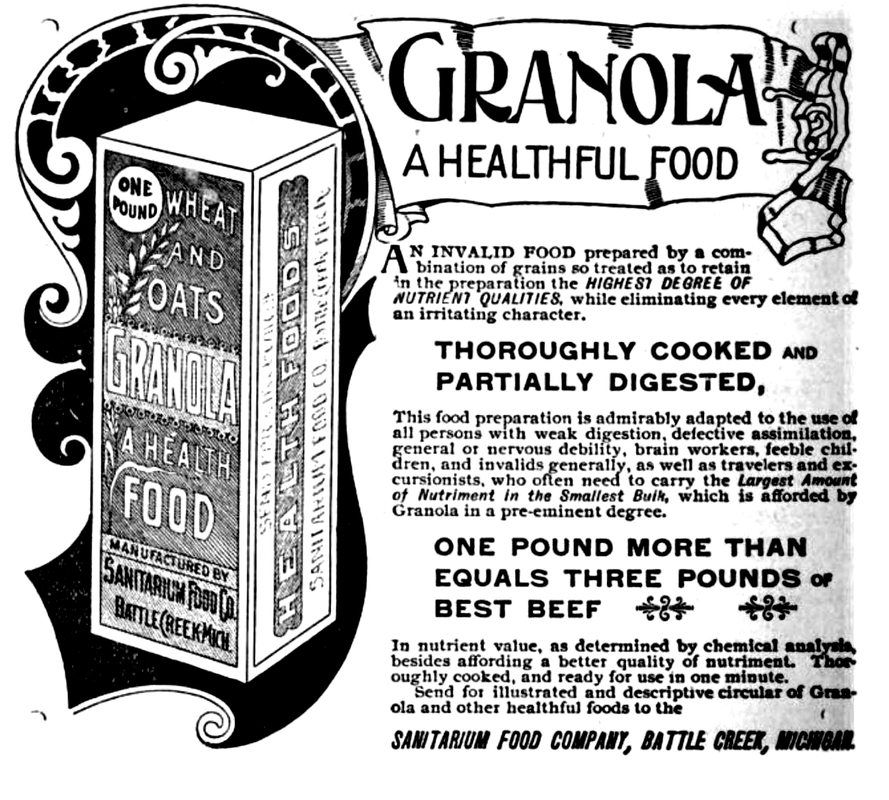

Thanks to everyone who joined in this weeks' Food History Happy Hour! In this episode we made the Guadalcanal Cocktail and discussed rhubarb, abolitionist boycott of sugar and the slave trade, rhubarb recipes and all the animals who are eating my rhubarb, breakfast cereals, in particular GrapeNuts and the real story GrapeNuts ice cream (and its predecessor GrapeNuts pudding), graham flour and graham pudding, Kellogg v. Post cereals (as seen on The Food That Built America), including the history of Granula, the accident of corn flakes, C.W. Post and the California Fig Nut Company, sugary breakfast cereals in the 1950s and on, shredded wheat, the Victorian interest in grain-based products with milk on top, Wheatina, frog eye salad, Cool Whip, rural v. urban breakfast trends, food deserts, housing policy and suburbs, TV and dinners, the addictiveness of sugar, the food pyramid, the history of lunch, including nuncheon, and the introduction of fellow food historian Niel De Marino, who specializes in 18th century foodways and runs The Georgian Kitchen, Russian/Georgian food and cookbooks, Black Panthers, and the reaction to the film "Birth of a Nation."

With a cameo by Sweetie Pie, of course! And I believe this was our longest and most lively Food History Happy Hour yet! Guadalcanal Cocktail

1 jigger bourbon (Old Crow is most accurate)

2-3 ice cubes unsweetened grapefruit juice In an old fashioned glass, pour jigger of bourbon over ice. Fill with grapefruit juice and stir. The REAL Story of Grape Nuts Ice Cream

Well as you may know I get a lot of media requests, so one on the origin of Grape Nuts ice cream was fun to research, even if the request was VERY last-minute. Sadly, my commentary on the history did not make the cut of the rather frivolous radio spot (annoying, considering how much work I put into it, all free of charge), but it DID result in some fun research on Grape Nuts ice cream, which was, sadly, NOT invented by Hannah Young in Wolfville, Nova Scotia in 1919, as many people, including her grandson Paul, have claimed. Or at least, Hannah may have come up with the combination independently (although I doubt that could ever be verified), and likely had a hand in popularizing it in Nova Scotia, but I've found references that predate Young by at least 10 years.

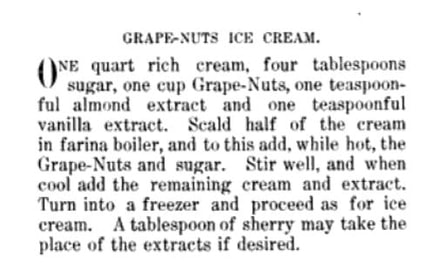

This reference, from the American Housekeeper Advertiser dates to 1909 and is the earliest published reference I could find.

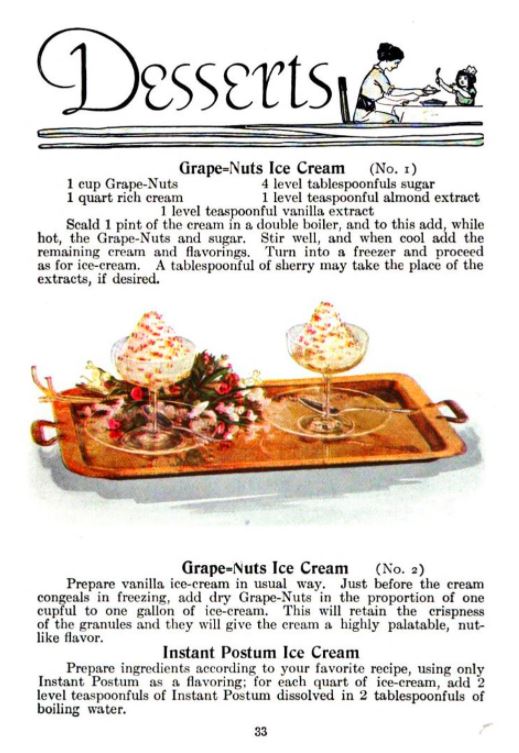

Of course, in 1916, the Post company published, "Good Things to Eat From Wellville."

The first recipe listed in "Good Things to Eat" is very similar to the one from the American Housekeeper Advertiser, but the second is simply vanilla ice cream with Grape Nuts folded in. Also notice with "coffee" flavored Postum ice cream! The cookbook also includes Post Toasties ice cream and several other confection recipes using the cereals. And of course, all these recipes predate the 1919 Hannah Young story.

At any rate - it was a fun research project and I'm glad I was able to add to the historiography of Grape Nuts Ice Cream.

Here's a flurry of other links related to tonight's talk!

If you liked this post and would like to support more Food History Happy Hour livestreams, please consider becoming a member or joining us on Patreon. Members and patrons get special perks like access to members-only content.

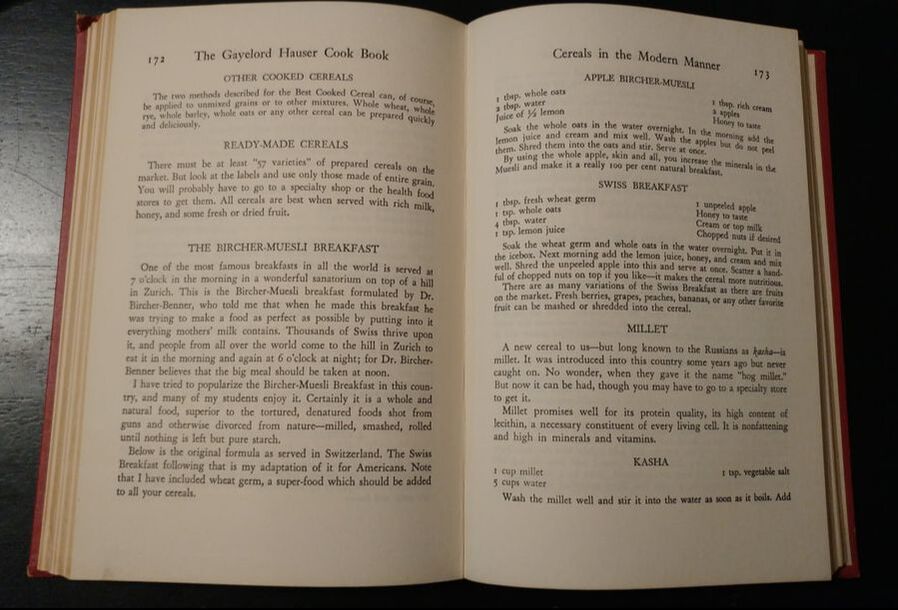

"The Food That Built America" just finished up last night, and I also reached over 200 likes on Facebook! So as a reward to my new friends and faithful followers, I thought I'd take a look at the Kellogg Brothers, who show up in all three episodes. Granola was the cereal that started it all. In the late 1870s, Dr. John Harvey Kellogg used it as part of his health regimen for his sanitarium patients. Based on a twice-baked unleavened bread made of wheat and oat flour, the cereal was then hammered into chunks and soaked in milk before serving. He initially called it "Granula." There was just one problem - there already was a "Granula." This was not covered in the History Channel series, but Kellogg was actually threatened with a lawsuit in 1881 by James Caleb Jackson, of upstate New York. Like Kellogg, Jackson was influenced by Seventh Day Adventist Ellen G. White, who advocated for vegetarianism and other health reforms. But at his hygenic water cure spa in upstate New York, Jackson developed "Granula," based on a twice-baked plain graham flour biscuit (graham flour is un-separated ground whole wheat). He rolled the flour-and-water mixture into sheets, which were baked, then broken into pieces and baked again, and then broken into smaller pieces, similar to the Grape-Nuts that C.W. Post would eventually develop. He invented "Granula" in 1863 - fifteen years before Kellogg. In response to the threat of lawsuit, Kellogg simply changed the name to "Granola." Both Jackson and Kellogg were likely inspired by simple rusks or zwieback or even hardtack. Dating back to ancient times, twice-baked breads were shelf-stable, durable, and long lasting. Hardtack (sometimes called a "cracker" or "ship's biscuit") was a common sight on merchant vessels and naval ships alike and was common soldier fare from the Revolutionary War to the Civil War. Made of just flour, water, and salt, hardtack was, well, hard. It was meant to be softened in coffee, stew, or water before it could be eaten. But its hardness made it the ideal, stable staple for long voyages without refrigeration. Rusks, on the other hand, were more likely to be made with sugar, butter, and eggs and were much closer to our most familiar modern incarnation - biscotti. Some rusks, like zwieback, were even yeast-leavened sweet breads that were twice baked. It stands to reason then, that Kellogg's original "Granola" was a mixture of whole grain wheat flour (graham) and oat flour, mixed with water (no salt or sugar), and twice-baked before crumbling into what would become "cereal." Having made hardtack myself, I can inform you that the trick is in the kneading - as you develop the gluten in the flour it smooths out and becomes easier to work and shape (and roll!). While no known recipe for Kellogg's original "Granola" exists, I did dig up a recipe for "Granula" from the 1906 Inglenook Cookbook, published by the Church of the Brethren, a non-demoninational Christian sect. Apparently hard-baked plain cereals continued their trend of association with religious organizations. You can find more about the Inglenook Cookbook in all its incarnations here. In true, early 20th century style (and like many community-based cookbooks from this time period), the instructions are written in paragraph form. Granula Get good graham flour, take pure spring or soft water, nothing else, and knead to a stiff dough. Roll and mould as for biscuit (not as thick). Bake thoroughly in a hot oven. When well done, or over done, remove and cool, then cut each piece in halves and put back in a warm baker and dry to a crisp, not brown or burnt. A yellow brown will not hurt. Now crush or break in small bits and grind them as you would coffee. You now have one of the best health foods known. It can be served in various ways. Soaked in good, rich milk is the best way to eat it. Some like to add a little sugar, some a little salt (but don't add salt when you bake it, it spoils the flavor). Some eat it with fruit. It makes a nice cold Sunday dish and is always ready. It can be used in puddings and mixed with bread for dressings. We have made and used this hygienic food for 23 years, and know its merits. The biscuits, or graham crackers, warm from the oven, well baked, with crispy crust, make a delightful bread. We have a small hand mill to grind them. If you cannot get good graham flour, if it is too rough with bran, add a little white flour, or sift the coarsest bran out. Graham made of white wheat is best. - Sister Amanda Witmore, McPherson, Kans. While granula and similar incarnations continued to be eaten into the twentieth century, what we know as Granola today is not really a direct descendant of Kellogg's granola (or Jackson's granula). In 1900 a Swiss physician named Dr. Maximillian Bircher-Benner developed another type of grain cereal called Bircher-muesli (later shortened to muesli). Adhering to Bircher-Benner's beliefs that raw foods were the most healthful, muesli primarily contains uncooked rolled oats, with nuts, seeds, and fruits added in. Served plain or with milk, it was originally intended as an accompaniment to meals or a light supper, not breakfast. In 1946, Hollywood health guru Gaylord Hauser published several recipes for "The Bircher-Muesli Breakfast" in his Gaylord Hauser Cookbook. Hauser had studied in Switzerland and was likely heavily influenced by Bircher-Brunner in his own health style, as he often emphasized fresh fruits and vegetables and even juicing. Muesli started to become known among health food enthusiasts after the Second World War, in part thanks to Hauser and others like him who visited Switzerland. Health guru Adelle Davis, however, is credited with introducing what we know today as "granola" to the masses in the 1960s. Although the Adelle Davis Foundation credits her 1947 book Let's Cook It Right with first mentioning granola, I can't find any reference in my copy. In fact, her short chapter on cereals makes no mention of cold, crunchy cereals like granola and contains just one recipe - for how to cook hot cereals (p. 427-439). Adelle is purported to have introduced granola as a snack, but her section on snacks in her introduction to Let's Cook It Right makes no mention of granola - instead suggesting fruit, milk, cheese and crackers, or nuts as good "midmeal" options (p. 17-22). Regardless of how she introduced it, Adelle is likely one of several people to discover that by combining rolled oats with nuts, dried fruit, oil and honey, you get a delicious crunchy baked snack. Her "grandaddy" recipe is below: Adelle Davis’ Grandaddy of Granolas 5 cups rolled oats 1 cup each of chopped almonds, sesame seeds, sunflower seeds, shredded coconut, soy flour, powdered milk (preferably non-instant), and wheat germ. 1 cup warmed honey 1 cup oil, any kind Preheat the oven to 300 degrees. Combine dry ingredients. Combine honey and oil and drizzle over the dry ingredients tossing and coating. Spread the mixture on 2 cookie sheets and bake for 30 to 45 minutes until golden. Makes up to 12 cups, depending what you add or leave out. Eventually, people stopped eating granola out of hand and started pouring milk on top and eating in the morning. Of course, these days, modern granola is far more like Adelle's than Kellogg's (or Jackson's) in that it is heavily sweetened and usually quite fattening. But because of its health guru and sanitarium past and its association with hiking and other outdoor pursuits in the 1960s and '70s, we tend to associate it with healthy food, even though it is anything but. If you'd like to learn more about Gaylord Hauser and Adelle Davis, take a listen to my podcast, History Bites: Full of Pep, the Controversial Quest for a Vitamin-Enriched America, Part 2. So that's the end of my reward post for making it to 200+ likes on Facebook. MaryAnn - are you satisfied? :) I hope you enjoyed this post. If you did, please consider becoming a patron on Patreon to support this and other food history blog posts, podcasts, videos, and more. |

AuthorSarah Wassberg Johnson has an MA in Public History from the University at Albany and studies early 20th century food history. Archives

July 2024

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed