|

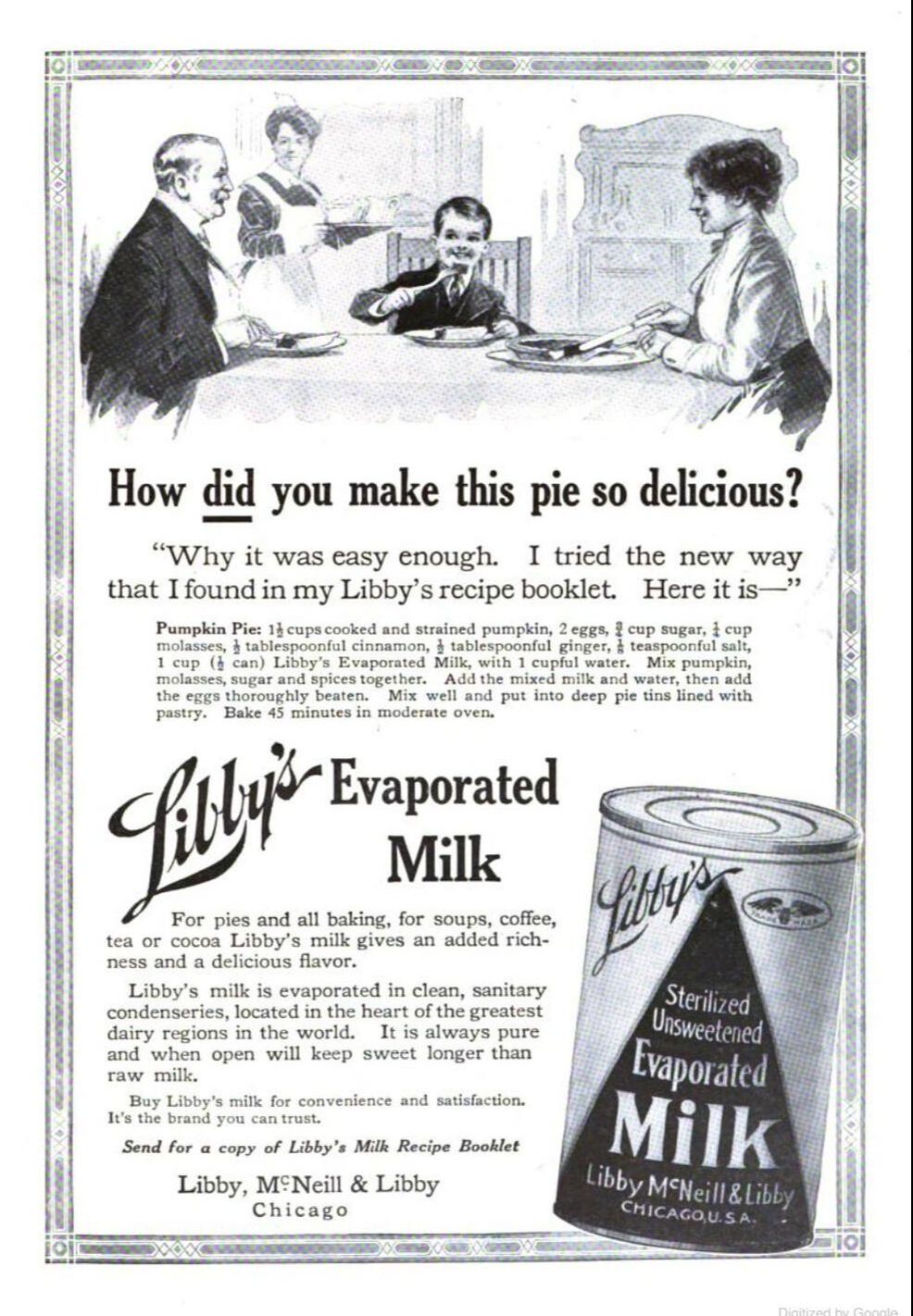

Libby's pumpkin pie is the iconic recipe that graces many American tables for Thanksgiving each year. Although pumpkin pie goes way back in American history (see my take on Lydia Maria Child's 1832 recipe), canned pumpkin does not. Libby's is perhaps most famous these days for their canned pumpkin, but they started out making canned corned beef in the 1870s (under the name Libby, McNeill, & Libby), using the spare cuts of Chicago's meatpacking district and a distinctive trapezoidal can. They quickly expanded into over a hundred different varieties of canned goods, including, in 1899, canned plum pudding. Although it's not clear exactly when they started canning pumpkin (a 1915 reference lists canned squash as part of their lineup), in 1929 they purchased the Dickinson family canning company, including their famous Dickinson squash, which Libby's still uses exclusively today. In the 1950s, Libby's started printing their famous pumpkin pie recipe on the label of their canned pumpkin. Although it is the recipe that Americans have come to know and love, it's not, in fact, the original recipe. Nor is a 1929 recipe the original. The original Libby's pumpkin pie recipe was much, much earlier. In fact, it may have even predated Libby's canned pumpkin. In 1912, in time for the holiday season, Libby's began publishing full-page ads using their pumpkin pie recipe in several national magazines, including Cosmopolitan, The Century Illustrated, and Sunset. But the key Libby's ingredient wasn't pumpkin at all - it was evaporated milk. Sweetened condensed milk had been invented in the 1850s by Gail Borden in Texas, but unsweetened evaporated milk was invented in the 1880s by John B. Meyenberg and Louis Latzer in Chicago, Illinois. Wartime had made both products incredibly popular - the Civil War popularized condensed milk, and the Spanish American War popularized evaporated milk. Libby's got into both the condensed and evaporated milk markets in 1906. Perhaps competition from other brands like Borden's Eagle, Nestle's Carnation, and PET made Libby's make the pitch for pumpkin pie. Libby's Original 1912 Pumpkin Pie Recipe:The ad features a smiling trio of White people, clearly upper-middle class, or even upper-class, seated around a table. An older gentleman and a smiling young boy dig into slices of pumpkin pie, cut at the table by a not-quite-matronly woman. A maid in uniform brings what appears to be tea service in the background. The advertisement reads: "How did you make this pie so delicious?" "Why it was easy enough. I tried the new way I found in my Libby's recipe booklet. Here it is - " "Pumpkin Pie: 1 ½ cups cooked and strained pumpkin, 2 eggs, ¾ cup sugar, ¼ cup molasses, ½ tablespoonful cinnamon, ½ tablespoonful ginger, 1/8 teaspoonful salt, 1 cup (1/2 can) Libby’s Evaporated Milk, with 1 cupful water. Mix pumpkin, molasses, sugar and spices together. Add the mixed milk and water, then add the eggs thoroughly beaten. Mix well and put into deep pie tins lined with pastry. Bake 45 minutes in a moderate oven. "Libby’s Evaporated Milk "For all pies and baking, for soups, coffee, tea or cocoa Libby’s milk gives an added richness and a delicious flavor. Libby’s milk is evaporate din clean, sanitary condenseries, located in the heart of the greatest dairy regions in the world. It is always pure and when open will keep sweet longer than raw milk. "Buy Libby’s milk for convenience and satisfaction. It’s the brand you can trust. "Send for a copy of Libby’s Milk Recipe Booklet. Libby, McNeill & Libby, Chicago." My research has not been exhaustive, but as far as I can tell, Libby's was the first to develop a recipe for pumpkin pie using evaporated milk. Sadly I have been unable to track down a copy of the 1912 edition of their Milk Recipes Booklet, but if anyone has one, please send a scan of the page featuring the pumpkin pie recipe! Curiously enough, the original 1912 recipe treats the evaporated milk like regular fluid milk, which was a common pumpkin pie ingredient at the time. Instead of just using the evaporated milk as-is, it calls for diluting it with water! The recipe also calls for molasses, and less cinnamon than the 1950s recipe, which also features cloves, which are missing from the 1912 version. Both versions, of course, call for using your own prepared pie crust. Nowadays Libby's recipe calls for using Nestle's Carnation brand evaporated milk - both companies are subsidiaries of ConAgra - and Libby's own canned pumpkin replaced the home-cooked pumpkin after it purchased the Dickinson canning company in 1929. Interestingly, this 1912 version (which presumably is also in Libby's milk recipe booklet) does not show up again in Libby's advertisements. Indeed, pumpkin pie is rarely mentioned at all again in Libby's ads until the 1930s - after it acquires Dickinson. And by the 1950s, the recipe wasn't even making the advertisements - Libby's wanted you to buy their canned pumpkin in order to access it - via the label. The 1950s recipe on the can persisted for decades. But in 2019, Libby's updated their pumpkin pie recipe again. This time, the evaporated milk and sugar have been switched out for sweetened condensed milk and less sugar. As many bakers know, the older recipe was very liquid, which made bringing it to the oven an exercise in balance and steady hands (although really the trick is to pull out the oven rack and then gently move the whole thing back into the oven). This newer recipe makes a thicker filling that is less prone to spillage. Still - many folks prefer the older recipe, especially at Thanksgiving, which is all about nostalgia for so many Americans. I'll admit the original Libby's is hard to beat if you're using canned pumpkin, but Lydia Maria Child's recipe also turned out lovely - just a little more labor intensive. I've even made pumpkin custard without a crust. Are you a fan of pumpkin pie? Do you have a favorite pumpkin pie recipe? Share in the comments, and Happy Thanksgiving! The Food Historian blog is supported by patrons on Patreon! Patrons help keep blog posts like this one free and available to the public. Join us for awesome members-only content like free digitized cookbooks from my personal collection, e-newsletter, and even snail mail from time to time! Don't like Patreon? Leave a tip!

0 Comments

It's that time of year when people all over the world are thinking about graduating, either from high school or college. The question in so many minds is, "What's next?" High school students are considering what they should major in, whether they should do a summer internship or get a job, what they want their adult lives to look like. College students are doing much the same - considering whether to attend graduate school, try for an internship, get an entry-level job. And many of them are considering food history as a career option. When you call yourself "THE" food historian, you get a lot of questions about how to break into the field. After answering lots of individual emails, I've decided to tackle the subject in this blog post. I'll be breaking down what it takes to be a food historian, but first I want to emphasize that making a career out of history can be difficult, and it is not particularly lucrative. Even those with PhDs in their fields have trouble finding jobs. I myself work in the history museum field (more job opportunities, but the salaries are usually low) and do the work of a food historian as a passion project that occasionally pays me. That being said, there are folks who are able to make a living through freelance writing, being history professors (food history and food studies programs are expanding in academia), working in museums, writing books, consulting on films, and even making YouTube videos and podcasts. It's not easy, and it's generally not lucrative, but if you have a passion for history and food, this may just be the route for you. A few other folks have written on this subject, notably Rachel Laudan. But while I think she has some great advice on the work of doing food history, that's not quite the same thing as being a food historian. The Inclusive Historian's Handbook, which is a resource for public historians, has also written about food history, albeit in a forum meant for public historians and museum professionals. So I thought I'd tackle my own definitions and advice. I should note that this guide is going to be necessarily focused on the field of food history in the United States, because that is my lived experience, but most of the basic advice is applicable beyond the U.S. What is food history?First, let's do a little defining. I use the term "food history" in the broadest sense. It encompasses:

Food is the one constant that connects all humans throughout human history. Which is part of why it is so appealing to so many people, including non-historians. The History of Food HistoryProfessor and food historian Dr. Steven Caplan of Cornell University has written on the history of the field, but here's my own summary. Although agricultural history has a long and storied past, until quite recently food history was considered an unserious topic of study in academia. Even after the social history revolution of the 1970s, which coincided with a groundswell of public interest in the past thanks to the American Bicentennial, food history was largely considered the purview of museum professionals, reenactors, and non-historians. Even trailblazing scholars like Dr. Jessica B. Harris approached food history from an oblique angle - she has a background as a journalist, her doctoral dissertation was on French language theatre in Senegal, and she was a professor in the English Department at Queens College in New York City for decades. And yet her groundbreaking books helped set the tone for subsequent historians. In fact, many of the food history books published in the last fifty years have been written by non-historians - largely journalists and food writers. And while many fine works have come out of that technique, as someone who has a background in both cooking and academic history, there are often missed opportunities in food history books written by both non-historians and non-cooking academics alike. So why has food history been deemed so unserious? A couple of reasons. One was that gatekeepers in the ivory tower didn't consider food an important topic. It was such a ubiquitous, everyday thing. It seemed to have little importance in the grand scheme of big personalities and big events. But I think its very ubiquity is part of the reason why food history is so compelling and important. Another reason was that the primary actors throughout food history were not generally wealthy White European men. They were (and often still are) primarily women and people of color - producing and growing food, preparing, cooking, preserving, and serving it. Racism and sexism influenced whose history got told, and whose didn't. You can still see some of this bias in modern food history, which often still focuses on rich White dudes with name recognition. Then, when people began studying social history in the 1960s and '70s, food history largely remained the work of museums, historical societies, and historical reconstructions like Old Sturbridge Village and Colonial Williamsburg. It was popular, and therefore not serious. Real food historians knew better. They persisted, but it was a long slog. Let's take a look at a brief (and very incomplete) timeline of food history in the United States since the Bicentennial: In 1973, British historian and novelist Reay Tannahill published Food in History, which was so popular it was reprinted multiple times over the following decades. In 1980, the Culinary Historians of Boston was founded. In 1985, the Culinary Historians of New York was founded. In 1989, museum professional Sandra (Sandy) Oliver began The Food History News, a print newsletter (a zine, if you will) dedicated to the study and recreation of historical foodways. Largely consumed by reenactors, museum professionals, and food history buffs, the publication of the newsletter sadly ceased in 2010. I am lucky enough to have been given a large portion of the print run by a friend, but Sandy's voice is missed in the food history publication sphere. In 1999, librarian Lynne Olver created the Food Timeline website, dedicated to busting myths and answering food history questions. Lynne sadly passed away in 2015, but in 2020 Virginia Tech adopted the Food Timeline and Lynne's enormous food history library. Lynne herself published some food history research recommendations as well. The Food Timeline is likely responsible for many a budding food historian, as it is incredibly fascinating to fall down the many rabbit holes contained therein. In 1994, Andrew F. Smith published The Tomato in American Early History, Culture, and Cookery. He joined the New School faculty in 1996, starting their Food Studies program. He has since gone on to publish dozens of food history books and is the managing editor of the Edible series, which began in 2008 under Reaktion Press, now published by the University of Chicago Press. In 1998, food and nutrition professor Amy Bentley published Eating for Victory - one of the first-ever history books to tackle food in the United States during World War II. In 2003, the University of California Press started its food history imprint with Harvey Levenstein's Revolution at the Table. Levenstein is an academically trained social historian and helped reinvent food history's brand as a serious topic for "real" historians to tackle. In the last 20 years, the study of food history has exploded. Dozens of books are published each year, and more and more people are choosing food as a lens to study all kinds of things, with history at the forefront. Food history has increasingly become a serious field of study, and more and more academically trained historians are bringing their skills to the field, helping shift the historiography. Even so, issues persist. Until very recently, the broad focus of American food history was still very White, and very middle- and upper-class, in large part because those were the folks who published the most cookbooks and magazine articles, who owned and patronized restaurants, who built food processing companies, etc. Low hanging fruit, and all that. The field is diversifying, but the assumption that American food is White Anglo-Saxon persists. Like bias in general, it takes constant work to overcome. Problems in Food HistoryBecause food history is so popular, and so many non-historians have contributed to the historiography, issues that plague all popular subjects persist. First, food history is FULL of apocryphal stories and legends. Many of these continue because non-historians take primary and secondary sources at face value without critical thinking. Many food history books published by non-historians and/or in the popular press do not contain citations. Sometimes this is a design choice by the publisher and not a reflection on the scholarship of the historian. But sometimes this is because the writer is simply regurgitating legends they found somewhere questionable. Food historians need to delve deeply, think critically, and amass corroborating evidence when at all possible. Mythbusting is an important part of the field. Second, non-historians tend to take foods out of context and make assumptions about the people in the past. In the United States, the general public simultaneously romanticizes our food past (yes, there were pesticides before World War II, no, not everyone knew how to cook well) and vilifies difference. I'm sure you've seen all of the memes and comments making fun of foods of the past (I've tackled a few of them here and here). The idea that tastes or priorities might change boggles the minds of folks who are stuck in the mindset of the present. But historical peoples were diverse, circumstances (like central heating and air conditioning) changed frequently, and both had a big impact on how and why people ate what they did. While we can't excuse moral issues like racism, sexism, and xenophobia, it's important to note that there were always people in the past fighting against those isms, too. Rejection of those mindsets is not a uniquely modern idea. The idea that modern humans are somehow morally better, smarter, more sensitive, etc. than historical peoples is not only wrong, it is dangerous, because it implies that we are somehow so advanced that we do not need to self-critique. Nothing could be further from the truth. Third, many of the research questions I and many food historians get from journalists and students tend to focus on origin stories of certain foods. Some are provable, most are not, and most confoundingly for the folks who want to know who did it FIRST, sometimes certain types of foods crop up simultaneously in unrelated places. The real issue with these questions is, who cares who made the first eclair? I mean, maybe you do, but what does finding out who made the first eclair tell us about food history? Perhaps you might argue that it was a turning point in the history of French baking, and went on to influence global fashion for decades to come. You might be right. But if your question is "who did it first?" instead of "what are the wider implications of this event?" or "what does this tell us about the time and place in which it was created?" or "how did this influence how we do things today?" you're asking the wrong questions. We ask "who cares?" a lot in the museum field. To be a good educator and communicator of history, you must make it not only understandable, but relevant to your audience. The origin of the tomato is largely unimportant except as an exercise in research unless you can connect it somehow to our modern society and make people care. On the flip side of things, and finally, there is a lot of gatekeeping in academia about food history. I've actually seen academics bemoan the idea of using food as a lens to study broader historical ideas, instead of focusing only on the food. Which is ridiculous. That's like saying the history of clothing has to focus only on the physical clothes themselves, and not the people who wore them, the society that created them, or the political, economic, and/or religious meaning behind them. Food history is meant to illuminate the hows and whys behind what is probably the biggest and most pervasive driving force behind most of human history - the acquisition and consumption of food. Focusing only on individual dishes doesn't improve food history - it dilutes it. Thankfully, many of these problems can be solved by following two simple truths. To be a food historian, you must first be a historian, and you must also know food. To be a food historian, you must first be a historianThis is a tough one for a lot of folks. The word "historian" conjures up old men with white beards and tweed jackets sitting in book-filled academic offices. But a historian is less a specific person and more a set of skills and experiences. And food history differs from food studies in that it has a primary focus on history. Food studies is an increasingly popular field, especially for colleges and universities that want to attract students with diverse interests. But in my personal opinion, a lot of the work coming out of food studies programs lacks the rigor of history training. I base this judgement on some of the work I've seen presented at conferences. Doesn't mean there aren't fine folks in food studies, and mediocre folks in food history, but the broadness of the food studies umbrella seems to allow for a looser interpretation of the subject than I'd prefer. History is evidence-based, and the best history not only requires corroborating evidence, but also an examination of what is not present in the historical record, and why. Historians also produce original research, which is the primary difference between a history buff and a historian. History buffs can be subject experts and have read all the secondary sources on a topic, and even primary sources. But you're not a historian until you're producing original research. The medium for that research can take many forms. The most common are articles, conference papers, and books. But original research can also be presented in documentary films, podcasts, museum exhibits, etc. Public historians are the same as academic historians with one distinct difference: audience. A public historian's audience is the general public, and they must adjust their communications accordingly. Public historians use less jargon and give more context because their audience tends to have less foreknowledge of the subject. Although many academic historians are starting to see the public history light, many still have other academics as their primary audience, which leads to dry, jargon-y work that that is often purposely difficult to read and comprehend, designed so that only a few of their colleagues can fully understand it. I mentioned earlier that a lot of food history books have been written by journalists and food writers. On the one hand, this is a great thing. The writing quality is better and more approachable, and journalists in particular can be dogged about tracking down primary sources and following leads. But there are issues with non-historians writing history. Mainly, they miss stuff. Many journalists write food histories as one-offs, moving onto the next, usually unrelated topic. And food writers tend to focus more on what they know - cooking and eating - rather than what's happening more broadly in the time period they're examining, and how their research fits into that. Because neither group tends to have a breadth of knowledge about the time period or culture they are examining, they often overlook connections, make assumptions that aren't necessarily supported by the evidence, and generally miss a lot of cues that historians trained in that time period would pick up on. That stuff is usually called context. Context is the background knowledge of what is influencing a moment in history. It's the foreknowledge of the history that leads up to a moment, the understanding of the culture in which the moment is taking place, grasping the relationships between the historical actors involved in the moment, etc. I'll give you an example. Promontory, Utah, 1869. If you know your history, you'll know that's the date and place where the two sections of the transcontinental railroad were joined. If you didn't know the context around that event, you might consider it a rather unimportant local celebration of the completion of a section of railroad track. But the context that surrounds it - the technology history of railroads, the political history of the United States emerging from the Civil War, the backdrop of the Indian Wars and the federal government's land grabs and attempted genocide, the economic history of railroad barons and pioneers - this context is all incredibly important to fully understanding the Promontory Summit event and its significance in American history. Journalists are great at the who, what, where, when, and even how. They're less great at the context. History is more than reciting facts. It is more than discovering new things and rebutting the arguments of historians who came before you. History, especially food history, is about the why. When I was in undergrad, it was the why that drove me. My first introduction was via agricultural history. I was interested in history, but also in the environment, and sustainable agriculture was my gateway into the world of agricultural history. I wanted to know not only how our modern food system came into being, but also why it was the way it was. I was also deeply interested in eating, and therefore in learning how to cook, although it would take until my senior year in college to actually do much of it. A burgeoning interest in collecting vintage cookbooks helped. From there I researched rural sociology and the Progressive Era in graduate school, and that sparked my Master's thesis on food in World War I, and the rest is history (pun intended). I'm now obsessed. Thankfully, being a historian is a lot less difficult than a lot of people assume. Like most skills, it just takes practice and time. If you like to read and write, you're curious, you are good at remembering and synthesizing information, and you're a good communicator, history might be your perfect field. It requires a lot of close reading, critical thinking, and the ability to organize information into coherent arguments and compelling stories. History is simultaneously wonderful and horrible because it is constantly expanding. Not only thanks to linear time, but also because new evidence is being discovered all the time and new research is being published daily. It's both an incredible opportunity and a daunting task. But with the right area of focus, it becomes not a boring task, but a lifelong passion. To be a food historian, you must also know foodThis is one some academics sometimes struggle with. Like journalists, they have can also have an incomplete understanding of their subject matter. I learned to cook not at my grandmother's knee, or even my mother's. I am self-taught, largely because I love to eat and eating mediocre food is a sad chore. But I did not start cooking for myself until late in college, and even then my first attempts were pretty disastrous. But while failure is a necessary component of learning any new skill, I dislike it enough to be highly motivated to avoid making the same mistake twice, and will take steps to avoid making subsequent mistakes. I'm pretty risk-averse. As an avid reader, I decided that books would be my salvation. I started collecting vintage cookbooks in high school thanks to a mother who passed on a love of both reading and thrifting. I read cookbooks like some people read novels - usually before bed. I got picky with my collecting. If a cookbook didn't have good headnotes, it was out. I wanted scratch cooking, but approachable, with modern measurements and equipment and not too many unfamiliar ingredients. Cookbooks published between 1920 and 1950 largely fit the bill, and I read lots of them. In grad school I expanded my cookbook reading, thanks in large part to Amazon's Kindle readers, which had hundreds of free public domain cookbooks, all published before the 1920s. Then I discovered the Internet Archive, and other historical cookbook repositories with digital collections. All the while I was learning to cook for myself, my roommates, and eventually my boyfriend (now husband). I worked in a French patisserie/coffee shop after college and honed my palate. I tried new recipes often and taught myself to be a good cook and a competent baker. I began to understand historical cooking through recipes. I mentally filed away hundreds of old-fashioned cooking tips. I thought about the best and most efficient ways to do things. I got confident enough to learn to adjust and alter recipes. I experimented. I made predictions and tested them. I learned from my failures and adjusted accordingly. In short - I learned to cook. But I still didn't consider myself a food historian. It seemed too big. I felt too inexperienced, despite all my research, both historical and culinary. Then, I had an epiphany. I attended a food history program with a friend. It had a lecture and a meal component. The lecture was good, but the speaker (who was not an academic historian) mocked a historical foodway I knew to be common in the time period. When I tried to call her on it after her talk, she brushed me off. Then, during the delicious meal, the organizer apologized that one of the dishes didn't turn out quite right, despite following the historical recipe exactly. I knew immediately the step they had missed, which probably was not in the recipe and which wasn't common knowledge except to someone who had studied historic cooking extensively. It was then I realized that there I was, a "mere" graduate student, and I had more depth and breadth of knowledge in food history than these two professional presenters. It was then I decided I could officially call myself a food historian. And that led me to write my Master's thesis on food history and launch this website. In the intervening years, I've often caught small (and occasionally not-so-small) food-related errors in academic history books. Assumptions, missed connections, misinterpretations of the primary sources, etc. It taught me that to be a food historian, you really have to know agriculture and food varieties, food preparation, how to read a recipe, and historical technologies to really understand the history you're studying. If that seems like a lot, it can be. But like learning to cook, doing the work of historical research is about building on the work that came before you. Both the work of other historians, and your own knowledge. We learn by doing, and through practice we improve. Understanding and starting food history research and writingSo now that we've got our terms straight, and we know we need to be well-versed in both history and food, what exactly do I mean by original research? Original research is based in primary sources and covers a topic or makes an argument that is not already present in the historiography (the published work of other historians). Some history topics are difficult to find original research to publish. The American Revolution and the American Civil War are two notable examples of this. There are few unexamined primary sources and the historiography is both wide and deep. Food history does not usually have this problem. In fact, several historians have recently focused on the food history of both the Revolutionary and Civil Wars. Because it has been so understudied, food is one of the few avenues left to explore in these otherwise crowded fields. World War I American home front history, however, is criminally under-studied, especially the field of food history (the Brits are better at it than us). Which is one of the reasons why I chose WWI as my area of focus. One major pitfall budding historians stumble into is the idea that you do research to prove a theory. Nope. Not with history. You should formulate a question you want to answer to help guide you and get you started. But cherry picking evidence to support your pet theory is not history. Real historians go where the research takes them. Sometimes your question doesn't have an answer because the evidence doesn't exist, or hasn't been discovered yet. Sometimes your pet theory is wrong. And that's okay! It's all part of the process. Even when you hit a dead end, you don't really fail, because you learned a lot along the way, including that your theory was not correct. And sometimes the research leads you to discover something you weren't even looking for, and that's often where the magic happens. Secondary Sources Food history research, like all history research, has a couple of levels. The first is secondary source material. This is your historiography - the works in and related to your area of study that other historians have already written and published. Books, journal articles, theses and dissertations are the best secondary sources because they generally use citations and can therefore be fact-checked. Secondary sources without footnotes should be taken with a large grain of salt. Any history that doesn't tell you where the evidence came from is suspect. I say this as someone who dislikes the work of footnoting intensely. But it's a necessary evil. But while secondary sources are usually written by experienced historians, they aren't always perfectly correct. Sometimes new research has been done since the book you're reading has been published, which is why it's important to read the recent research as well as the classics. Sometimes the historian writing the book makes a mistake (it happens). Sometimes the writer has biases they are blind to, which need to be taken into account when absorbing their research. Secondary sources can be both a blessing and a bane. A blessing, because you can build on their research instead of having to do everything from scratch. And a bane, because sometimes someone has already written on your beloved topic! Thankfully, there's almost always room for new interpretations. A good practice to truly understand a secondary source is to write an academic book review of it. Book reviews force you not only to closely analyze the text, but also to understand the author's primary arguments, evaluate their sources, and look at the book within the context of the wider historiography. Primary Sources The second level of research is primary sources. This is the historical evidence created in the period you're studying: letters, diaries, newspaper articles, magazines and periodicals, ephemera, photographs, paintings and sketches, laws and lawsuits, wills and inventories, account books and receipts, census records and government reports, etc. Primary sources also include objects, audio recordings (along with oral histories), historic film, etc. Primary sources generally live in collections held in trust and managed by public entities like museums, historical societies, archives, universities, and public libraries. Some folks like to insist that some primary sources are not primary sources at all, notably oral histories and sometimes even newspaper articles, because the author's memory or understanding of an event may not be accurate. But here's the deal, folks - pretty much no primary source is going to be a 100% accurate account of what is happening in history. The creators all have their biases, faulty memories, assumptions, etc. to contend with. Just because someone was present at a major event doesn't mean they're recording it correctly. It also doesn't mean they saw the whole thing, understood what they saw, or aren't completely lying about their presence there. Nobody has a time machine to go fact-check their accuracy, which is why corroborating evidence is important. ALL primary sources deserve some skepticism and an understanding of the culture that produced them. I should also note that primary sources only exist because someone saved them. And that "someone" historically was middle and upper-class White men. Which means a lot of historical documentation did NOT get saved. In particular, the work of women and especially people of color was not only not saved, sometimes it was actively destroyed. And even when those sources do exist, they can be hard to find, and are therefore often overlooked or ignored by the historians who have come before you. This is part of the skepticism of primary sources, too. Again, what is not present can be just as important as what is. Context And that's the third, often-overlooked level of research: context. We've defined it before. It can be a major stumbling block for non-historians. Context is when you take all the stuff you've learned from your secondary sources, and the cumulative knowledge of the primary sources you're studying, and put it into action. It's reading between the lines, understanding cultural cues, realizing what your primary sources aren't saying, who's absent, and what topics are being avoided. Context is understanding why historical figures do what they do, not just how. It can be easy to get wrapped up in the primary sources. I get it. They're fascinating! I've dived down many a primary source rabbit hole. But we have to think critically about them. Taking primary sources at face value has gotten a lot of historians into trouble, leading them to make assumptions about the past, to accept one perspective as gospel truth, and to overlook other avenues of research. No one source (or one person) ever has all the answers. Writing And finally, the last step of research: the writing. Some folks never make it to this point, just amassing research endlessly. And for history buffs, that's okay. But historians have to leave their mark on the historiography. There are a few important things I've learned in the course of writing my own book. First, get the words on the page. When it comes to writing history, get it on the page first, and then think about your argument, the organization of your article or chapter, the chronology, etc. You can't edit what isn't there, and editing is just as if not more important than writing. Everyone needs to be edited, and all works are strengthened by judicious paring and rewriting. You can always edit, cut, rearrange, rewrite, and/or add to anything you write. In fact, you probably should! I'll give an example. When I'm writing an academic book review, I'll usually write out my first reactions in a way-too-long Word document. Then, once I'm satisfied I've covered all the bases, I'll start a new Word doc and rewrite the whole thing, summarizing, examining my gut reactions, and modulating my tone for the audience I'm writing for. Second, practice makes perfect. The more you write (and read), the better you'll get at it. You'll get better at formulating arguments, explaining things, writing for a specific audience, and just better at communicating overall. So many writers feel shame about their early works. I get it! Sometimes I cringe when I see my early stuff. But sometimes I'm retroactively impressed, too. You've got to put out buds if you want to grow leaves and branches. So write the book reviews, write the blog posts, submit journal articles, etc. Everything you do gets you a step further down the historian road. Third, it's important to know when to stop researching. You need enough research to be well-versed enough to do the work. But perfection is the enemy of done. If you can afford to spend decades researching and refining a single book, by all means please do so. But if you want a career in food history, you're gonna have to be more efficient than that. Finally, and this is the hardest one. You have to learn to kill your darlings. I learned that phrase from a professional writer friend. Just because you're endlessly fascinated by the COOL THING! you found, doesn't mean it should go in your book. If it doesn't advance your argument or is otherwise superfluous information, cut it. I'm at that stage now with my own book, and while it's painful, killing your darlings doesn't meant deleting them! Save them for future projects, turn them into blog posts or podcasts or YouTube videos if you like. But getting rid of the extraneous stuff will make your work so much stronger. Still want to be a food historian?Whew! You made it this far! You may be feeling daunted by now. That isn't my intent. Like learning to cook, doing the work of history takes practice. Start with a topic or time period you're interested in. Look to see if anyone else has already published anything on that topic, and read it. Expand your reading beyond your immediate topic to related topics. For instance, if you want to study food in the Civil War, read not only about food, but about war, politics, gender, agriculture, race, economics, etc. in the Civil War, too. See if your local public or university library has remote access to places like JSTOR, Newspapers.com, ProQuest, Project Muse. See if your local library or historical society has any archival records related to your topic. Scour places like the Internet Archive, the Library of Congress, HathiTrust, and the Digital Public Library of America for other primary sources. Many have been digitized and more are being digitized daily. Start looking, start reading, and start synthesizing what you've learned into writing of your own. If you're thinking of pursuing food history on the graduate level, look for universities with professors whose work you admire and respect, for places with rich food history collections, and for programs that excite you. I worked my way through graduate school, working in museums while getting my master's part-time. I also took two years off between undergrad and graduate school, trying to gain experience in my field before tackling the commitment of grad school. I heartily recommend trying the work of food history before you dive into academia. Finally, food history can be FUN! If this all seems like a lot of work, then maybe food history isn't for you, or perhaps you'd like to remain a food history buff, instead of a food historian. But if the idea of delving into primary sources, devouring secondary source material, learning everything you can about a topic, and then writing it all down to share with others excites you, congratulations! You're already well on your way to becoming a food historian, whether you want to make it your full-time career, or just a fun hobby. Whatever you decide - good luck and good hunting! Your friend in food history, Sarah The Food Historian blog is supported by patrons on Patreon! Patrons help keep blog posts like this one free and available to the public. Join us for awesome members-only content like free digitized cookbooks from my personal collection, e-newsletter, and even snail mail from time to time! Don't like Patreon? Leave a tip! |

AuthorSarah Wassberg Johnson has an MA in Public History from the University at Albany and studies early 20th century food history. Archives

July 2024

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed