|

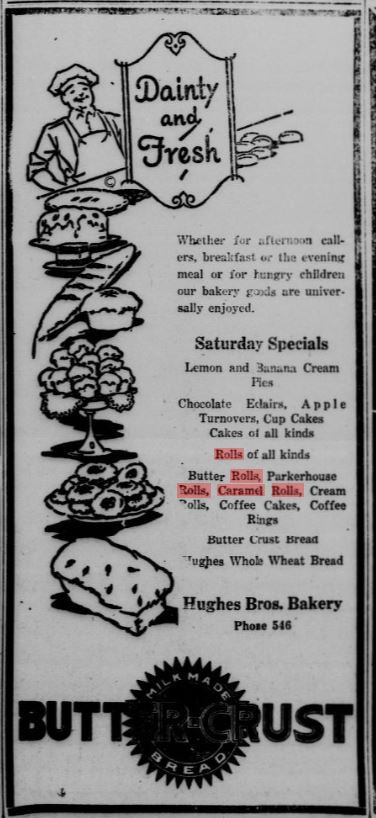

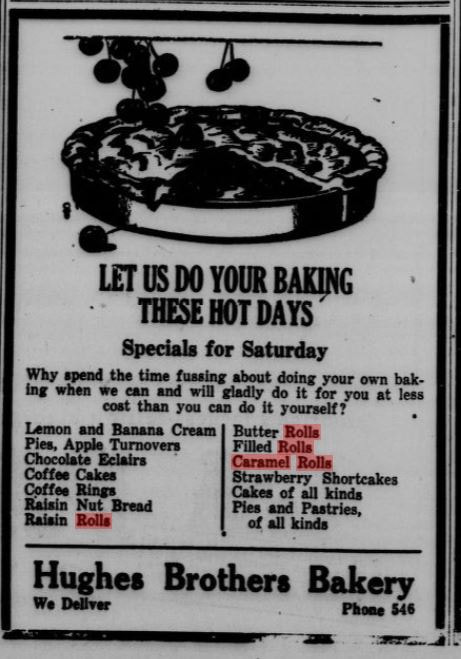

Last week I went home to Fargo, ND for my grandfather's funeral. He had passed away in June of this year, just a few weeks short of his 102nd birthday. Born in 1919, he lived to see a lot of change and ultimately, two global pandemics. It was the first time I had been home since 2019, when I returned for grandpa's 100th birthday and a cousin's wedding. Every time I go home to North Dakota, there's both joy and grief. Joy in seeing old friends and family, in visiting the old stomping grounds, in being able to see the whole sky without too many trees and mountains in the way, and being back in the land where Scandinavian culture still looms large (I went to the Sons of Norway, Kringen Lodge, four times in six days). But also grief, for what once was and will never be again. The common sort of grief when the stomping grounds change almost beyond recognition, but also another sort of grief, of cultural loss. When I was in high school, North Dakota had two Democratic Senators and a Democratic Representative and our biggest exports were wheat, sunflower seeds, honey, and sugar beets. Things have certainly changed since then. But some things haven't changed at all. Case in point: the North Dakota Caramel Roll (pronounced "car-mull," not "care-ah-mel"), formerly called "Dakota Rolls." Once the purview of rural cafes and church basements, the caramel roll is seeing something of a North Dakota renaissance. It's everywhere, and it's amazing. Not to be confused with cinnamon rolls or the sad, dried out, caramel roll cousin, the "sticky bun," caramel rolls are pillowy soft and drenched in smooth caramel. There's nothing worse than getting a caramel roll that's more roll than caramel. The Northeast can keep its dry and sticky buns with burnt pecans. I tried my best to track down the history of "Dakota rolls," but sadly no one else appears to have done the research yet, so this is my stab at it. I think perhaps their prominence in North Dakota has to do with the specific confluence of immigration that makes North Dakota - especially the Eastern half of the state - special when compared to others. Scandinavians, especially Norwegians, abound. Germans, too, but one particular group, Germans from Russia, have settled on the northern plains, including North Dakota, in higher concentrations than anywhere else in the world. The intersection of Scandinavian and German immigration has meant that North Dakota is home to some prodigious bakers. Cinnamon rolls are thought to have originated in Scandinavia, possibly Sweden. They were also historically popular in Germany, where the sticky bun or "schnecken" (snail) is from. Honey-sweetened buns date back to ancient Rome, but the idea to roll the dough flat, spread it with a filling, and roll it into a spiral before slicing was an inspiration whose inventor is lost to time. Caramel rolls specifically seem to date to the early 20th century in North Dakota. I did find a few 19th century references to "sticky buns," but no recipes. The search term "caramel roll" turns up almost exclusively candy advertisements and recipes until the 1920s. I did find one reference to caramel rolls from the Hughes Brothers Bakery in Bismarck, ND. Although the bakery itself predates 1911, they moved to a new location that year, and apparently began engaging in regular newspaper advertisements thereafter. I love the 1928 advertisement - "Let us do your baking these hot days," and published close to Memorial Day, no less! "Why spend time fussing about doing your own baking when we can and will gladly do it for you at less cost than you can do it yourself?" Why, indeed, Hughes Brothers. Why, indeed? Likely coinciding with the rise of diners, roadside cafes, and school cafeterias, the caramel roll expanded across North Dakota (and into some neighboring states, notably South Dakota) with a vengeance. Although there is little mention of them in North Dakota community cookbooks from the 1940s, by the 1970s they're in full evidence. The few recipes that I was able to find are remarkably similar, and all call for making the dough from scratch. But some modern bakers cheat and use frozen bread dough, notably Rhodes brand. My copy of the Westminster Presbyterian Church cookbook from Casselton, ND, undated but likely circa 1970s, judging by the handwriting, has a recipe for "Dakota Rolls" submitted by Mrs. William L. Guy. Mr. William L. Guy was governor of North Dakota from 1961-1973, and the Mrs. was Elizabeth "Jean" (Mason) Guy, who is credited with helping revive the Democratic Nonpartisan League in North Dakota (thanks for the research tip, Mom!). I've reproduced Jean's recipe in full below. Dakota Rolls Recipe1 c. scalded milk (do not boil) 2 T. butter 2 T. sugar 1 t. salt 1 cake compressed or 1 pkg. granulated yeast 1/4 c. lukewarm water 1 egg, well beaten 3 1/2 c. flour (about) Soften yeast in lukewarm water. Stir and let stand about 5 minutes. Combine milk, sugar, salt and shortening (i.e. the butter) and cool to lukewarm. Stir yeast and add to cooled milk. Beat egg, add to milk and yeast mixture. Gradually stir in the flour to form a soft dough (there should be about 1/2 cup flour left for kneading). Beat until smooth. Turn out on floured canvas or board. Cover with greased wax paper and a damp towel. Let rest for 10 minutes. Knead until smooth and satiny, adding flour as needed. This roll dough should not be too firm. Place dough in a warm greased bowl, turning until all of surface is lightly greased. Cover with greased wax paper and damp towel, and let rise in a warm place (85-90 F) about 1 hour and 45 minutes or until double in bulk. Punch down and let rise again until double in bulk. Turn out on flour dusted canvas or board and roll about 1/4" thick in oblong shape, 8" x 16". Brush with melted butter and sprinkle with 1/4 cup brown sugar. Roll as for cinnamon rolls. Cut in 1" slices. Combine 1 C. of brown sugar, 2 T. light corn syrup, and 1 T. butter. Heat slowly in a greased shallow pan or muffin tin. Set aside to cool. Place rolls, cut side down, over the mixture. Cover, let rise until double in bulk. Bake in 375 F oven for 25 minutes. Remove from pan. Cool, bottom side up. Makes 2 dozen rolls. It seems to me that this recipe, while very instructive in terms of the dough, has not nearly enough caramel to cover two dozen rolls. Modern cooks usually combine brown sugar and heavy cream, or some even swear that melted vanilla ice cream is the secret to good and ample caramel. However, the 1975 Fargo-Moorhead Centennial Cookbook also has a recipe for Dakota Rolls, submitted by Judy Adams, which appears to be lifted almost verbatim from the Casselton cookbook. Here's a more caramel-y modern recipe. Sadly, I haven't had time to test this recipe and it's been too hot to bake lately, but fall weather is coming! So maybe a weekend of yeast baking is in order soon. Perhaps I'll combine my caramel roll baking with orange rolls - another Midwestern specialty that seemed to be more prominent in the 1930s and '40s than their caramelly cousins. I'll leave you with one of the few photos I took at home - sunset on Tamarack Lake in Minnesota. And if you're ever in Fargo, try the rhubarb caramel rolls (yes! they put rhubarb in the bottom with the caramel! It's amazing!) at Kroll's Diner. They're divine. The Food Historian blog is supported by patrons on Patreon! Patrons help keep blog posts like this one free and available to the public. Join us for awesome members-only content like free digitized cookbooks from my personal collection, e-newsletter, and even snail mail from time to time! Don't like Patreon? Join with an annual membership below, or just leave a tip!

7 Comments

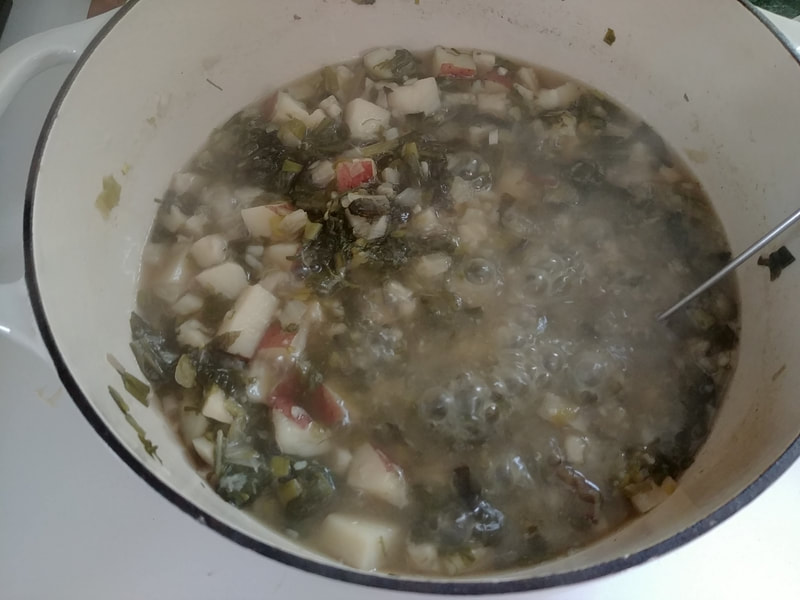

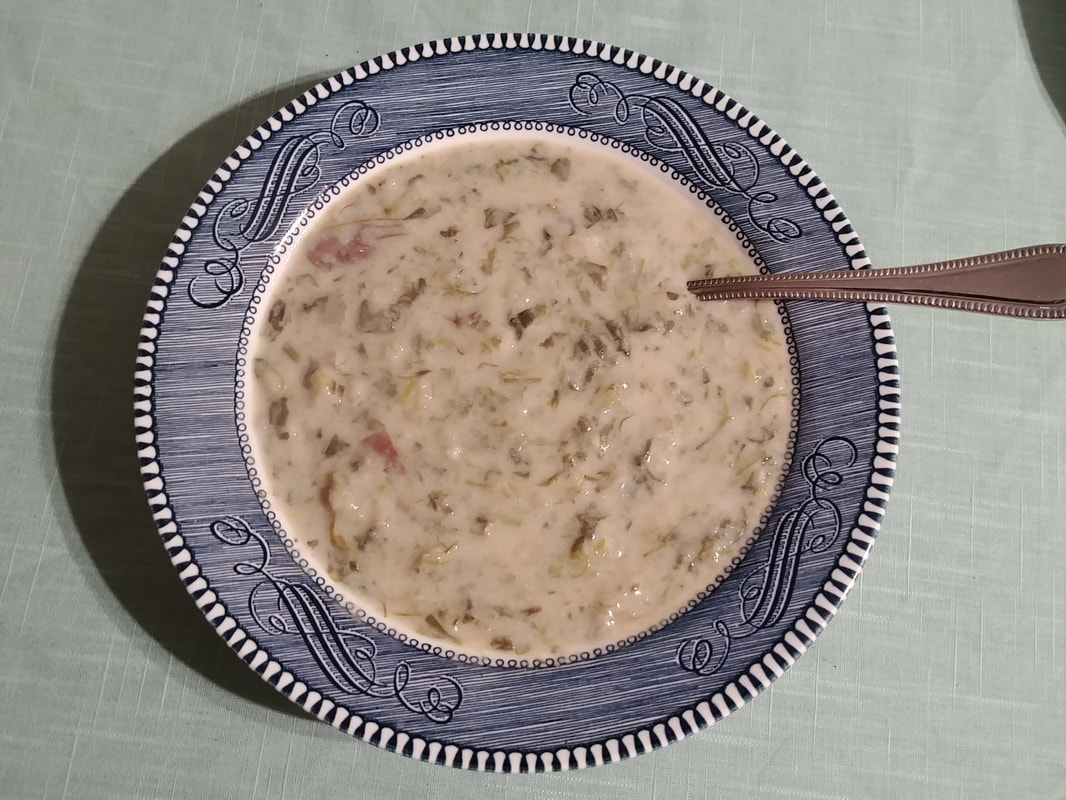

It's been cold and snowy lately here in the northeast, and sometimes you just have to have soup. But going to the grocery store in a snowstorm is ill-advised. This recipe lets you use up all kinds of bits and ends that might be languishing in your refrigerator.

This particular recipe is my own creation, based on what was in my kitchen, but is entirely inspired by history. Several parts of history, in fact. The first is reducing food waste. Historical peoples did not throw out potatoes just because they were starting to sprout, or lettuce because it was a bit wilted, and neither should you. Putting lettuce in soup is also extraordinarily historic, and a practice that should be revived. Another is that this recipe is based on one of my favorites, "Green Onion Soup," from Rae Katherine Eighmey's Hearts & Homes: How Creative Cooks Fed the Soul and Spirit of America's Heartland, 1895-1939 (2002). Eighmey read hundreds of agricultural magazines and gleaned recipes and wisdom from the farm home sections. Found in the December 26, 1924 issue of Wallace's Farmer, Green Onion Soup is a unique recipe. A combination of simply green onions and potatoes, the soup is cooked in a small amount of water, and then partially mashed right in the pot without draining. Cream and milk are added to thin the soup and add richness. The soup is comforting and nourishing and retains all of the vitamins and minerals that might otherwise be lost by draining away the cooking water. Which brings me to the final inspiration - vitamin retention in the style of recipes from World War II. By cooking the vegetables in the water that becomes the broth, you lose far fewer nutrients and flavor. Plus, other aspects of the soup are also quite appropriate to WWII - it's meatless, in line with rationing, and makes good use of milk, a favorite 1940s ingredient. Creamy Kitchen Sink Soup Recipe

I had a number of foods that needed using up that made their way into this soup: a few red potatoes, a head of wilted red lettuce, the fresh bits of baby spinach out of a box that was on the verge of getting slimy, a whole celery root starting to go a bit soft, some garlic starting to go green in the middle, and the tail end of a gallon of milk. The only fresh addition was two bunches of green onions. You could modify it pretty much however you want - any kind of greens, any kind of onion, any kind of root vegetable.

4 red potatoes 2 bunches green onions (scallions) 1 celery root 3 cloves garlic 1 head red lettuce 1-2 cups baby spinach water salt pepper 1/2 cup half and half 1 cup buttermilk whole milk Scrub and dice the potatoes, cutting away any eyes or bad parts, but leave the skin on. Slice the green onions, white and green parts. Cut away the knobbly skin from the celery root, then cut into small dice. Mince the garlic, wash and chop the whole head of lettuce. Add it all, with the spinach to a large stock pot and add water not quite to cover. Add at least 1 teaspoon salt (I used wild garlic flavored crystal salt languishing in a drawer) and bring to a boil. Reduce heat and simmer hard until all vegetables are very tender and potatoes fall apart when pierced with a fork. Do not drain. Using a potato masher or sauce whisk, mash vegetables in the pot until blended with the water, leaving some chunks. Add a the half and half and buttermilk (or you could use part heavy cream, or leave out the buttermilk, or just use milk) then add milk to thin out the soup and to taste. Taste for salt and add more if necessary, along with pepper and whatever other herbs and spices you like. Serve nice and hot with buttered bread or toast. The buttermilk does add a nice, distinctive tang. If you don't have any, add a dollop of sour cream, or some plain yogurt, or a splash of lemon juice. You could make this vegan with plant-based milk and butter. For a different flavor, add whatever fresh herbs you have lying around - dill, parsley, basil, and cilantro would all be good here. Add vegetable broth and some lemon juice instead of milk for a bright, brothy soup instead of something creamy. Use sweet potatoes or squash and tomato broth with the greens. The possibilities are really endless.

If you'd like more interesting recipes, you can purchase Eighmey's book from Bookshop or Amazon - either way, if you do, your purchase will support The Food Historian!

The Food Historian blog is supported by patrons on Patreon! Patrons help keep blog posts like this one free and available to the public. Join us for awesome members-only content like free digitized cookbooks from my personal collection, e-newsletter, and even snail mail from time to time!

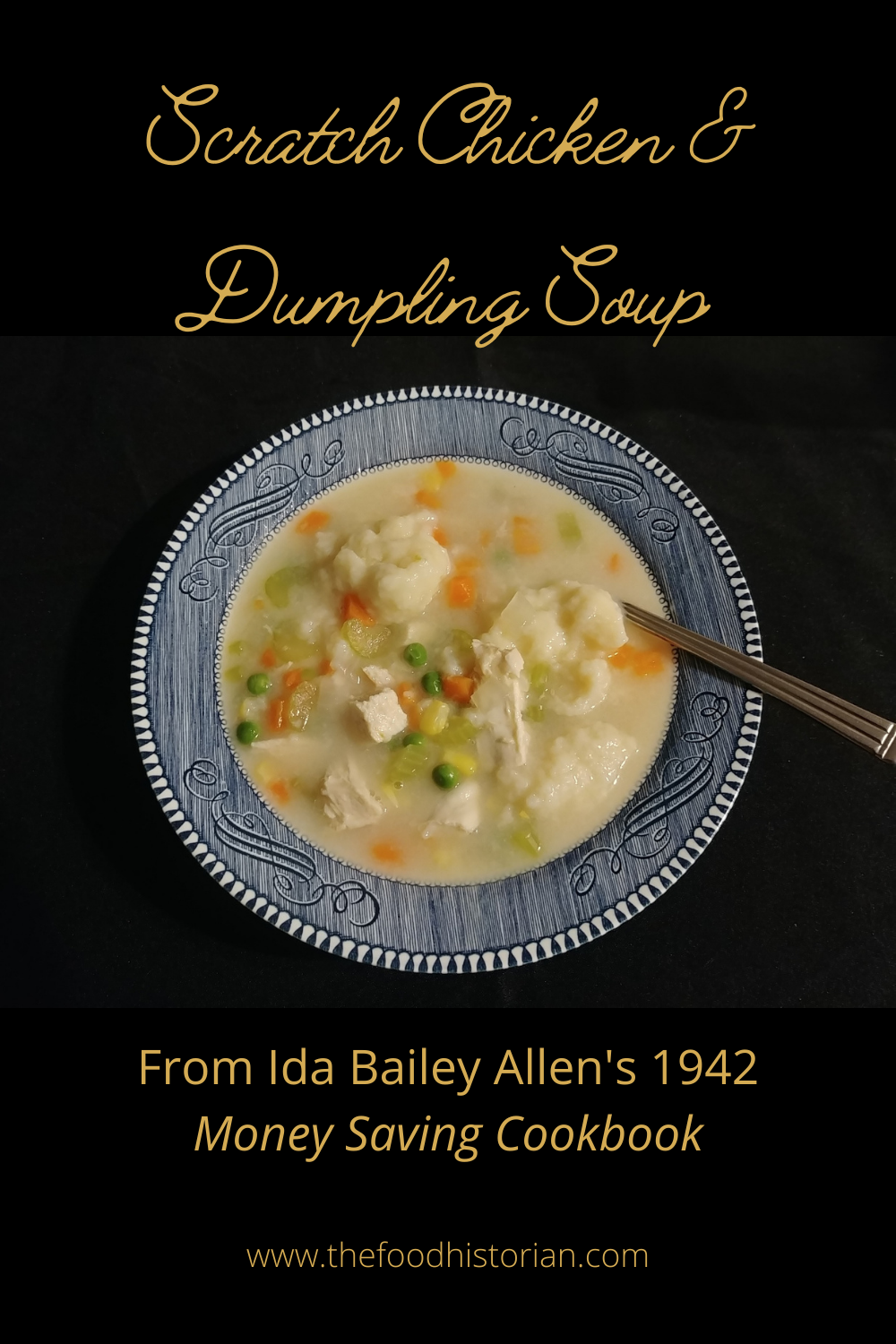

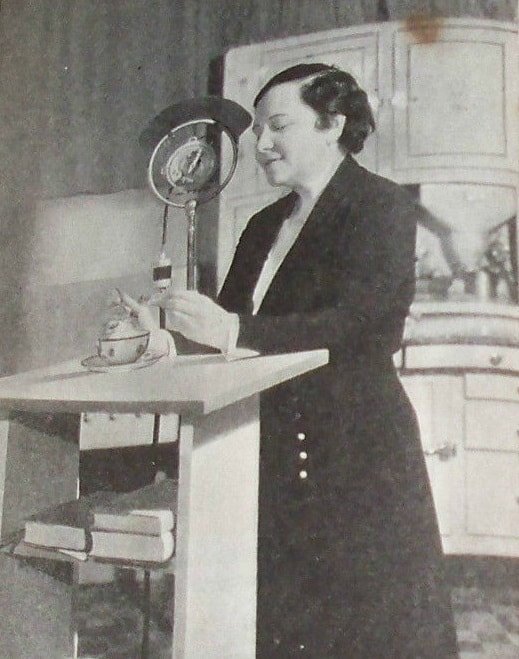

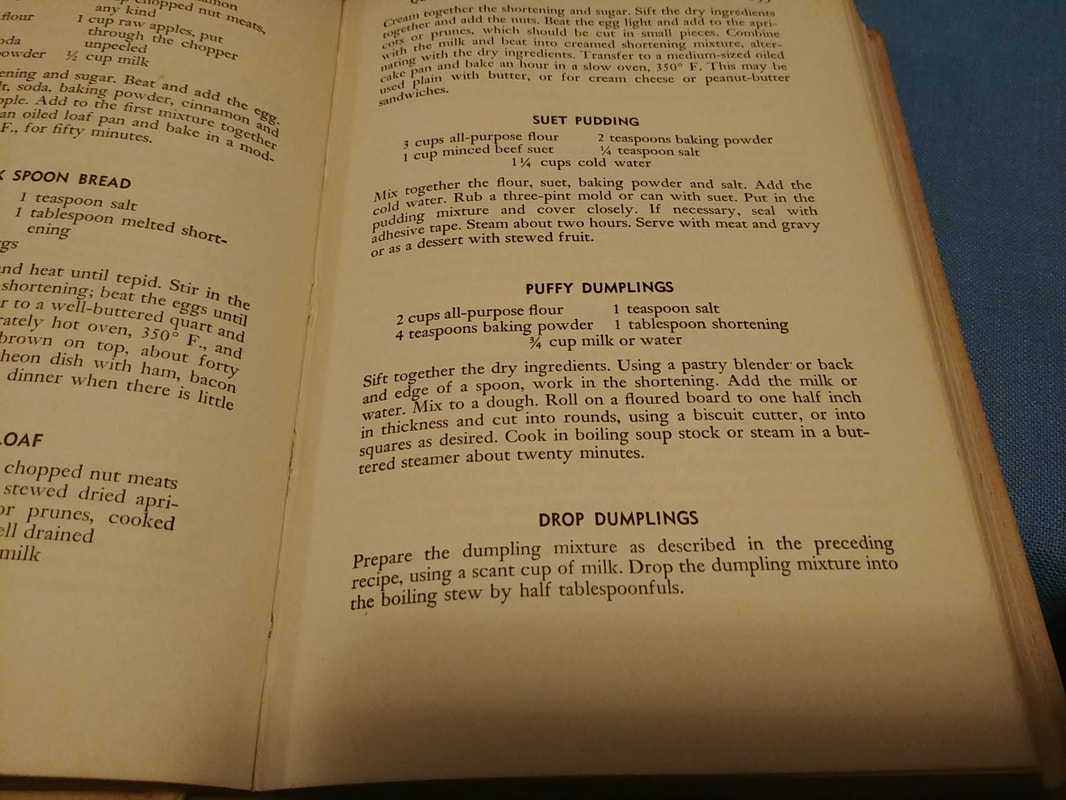

Today was a chilly VERY blustery day - my styrofoam Halloween headstone actually blew away this morning! Luckily it only blew into the side yard and wasn't too damaged. Long story short, it seemed like the perfect weather for chicken and dumpling soup. Only problem? I'd yet to find a good dumpling recipe. Until I consulted the glorious Ida Bailey Allen and her 1942 Money-Saving Cook Book. Ida Bailey Allen is one of my favorite relatively unknown celebrity cookbook authors. She was PROLIFIC and published over 50 cookbooks in her lifetime, from 1917 to the 1973 Best Loved Recipes of the American People, published the same year she died. A food writer, magazine editor, and essentially the founder of homemaker radio (she was the president of the Radio Homemakers Association), she was also the first female food TV host with her show "Mrs. Allen and the Chef" (you can listen to clip here!). One of the only moving images of Mrs. Allen that seems to survive on the internet is this little clip from the 1940s - a retrospective of the 1920s. Candy in tea! Who knew? Her Money-Saving Cook Book, first published in 1940 was republished in 1942 as a Victory edition, which is the version I have. It's just a delightful cookbook - chock full of basic, easy, and inexpensive recipes, as well as a bunch of 1940s-style vegetable recipes that I can't wait to try out. So when I was on the hunt for a dumpling recipe to go with my chicken soup, this one of the first cookbooks I consulted, and it did not disappoint. First, let's start with the chicken soup. Scratch Chicken Soup1 pound chicken 5 quarts water (or 4 quarts water and 1 quart chicken stock) 1 onion 2-3 ribs celery 1 cup diced carrots 1 cup frozen peas 1 cup frozen corn (or 1 bag mixed frozen corn, peas, and carrots) salt & pepper to taste Soup is always way easier than people think. It's just a matter of adding ingredients at the right time depending on how long they have to cook. Start with the chicken. You can use boneless or bone-in, skin-on. If using boneless, substitute 1 quart of water with chicken stock for extra flavor. In a large stock pot (I used my favorite cast iron dutch oven), add the chicken, water (and/or stock), onion, celery, and carrots (if using fresh). If not using chicken broth (which is salted), add a teaspoon of salt. Bring to a boil and reduce heat to a simmer, cooking until the chicken is cooked-through and the carrots are tender. About 20 minutes. Remove the chicken from the broth, dice, and return to the pot. Add the frozen vegetables and return to a simmer. Once the vegetables are tender, voila - chicken soup. You can now proceed to the dumpling recipe. Ida Bailey Allen's Puffy Drop DumplingsI didn't want to roll out the dumplings, so I used the Drop Dumpling version of the recipe. Here's the original, which turned out pretty well! I did substitute butter for the shortening. If you use salted butter, reduce the salt in the recipe to 1/2 or 3/4 teaspoon. 2 cups all-purpose flour 1 teaspoon salt 1 teaspoons baking powder 1 tablespoon unsalted butter 1 cup whole milk Use a balloon whisk to blend the flour, salt, and baking powder together. Cut the butter into small pieces and squish in the flour with your fingers (or cut in with a pastry blender) - there should be small chunks or streaks of butter left in the floury mixture. Then add 1 cup milk. Mrs. Allen called for a scant cup, but that wasn't quite enough - my mix was dry instead of being soft. Using a regular table or soup spoon, drop bits of dough about the size of a walnut (or a little larger) into the simmering soup. There will be a lot - submerge any exposed parts under the broth to make sure they steam properly. They'll start puffing up/breaking up almost immediately. Cover the pot and simmer for about 5 minutes. The flour from the dumplings will thicken the broth nicely. The dumplings exceeded my expectations - being a cross between that doughy chew you expect from a nice soup dumpling and light and spongy on the inside of the larger ones. All in all - a perfect one pot supper on a blustery, chilly day. The Food Historian blog is supported by patrons on Patreon! Join us for awesome members-only content like free digitized cookbooks from my personal collection, e-newsletter, and even snail mail from time to time!

|

AuthorSarah Wassberg Johnson has an MA in Public History from the University at Albany and studies early 20th century food history. Archives

July 2024

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed