|

The Food and Drug Administration recently announced that it would be de-regulating French Dressing. And while people have certainly questioned why we A) regulated French Dressing in the first place and B) are bothering to de-regulate it now, much of the real story behind this de-regulation is being lost, and it's intimately tied to the history of French Dressing.

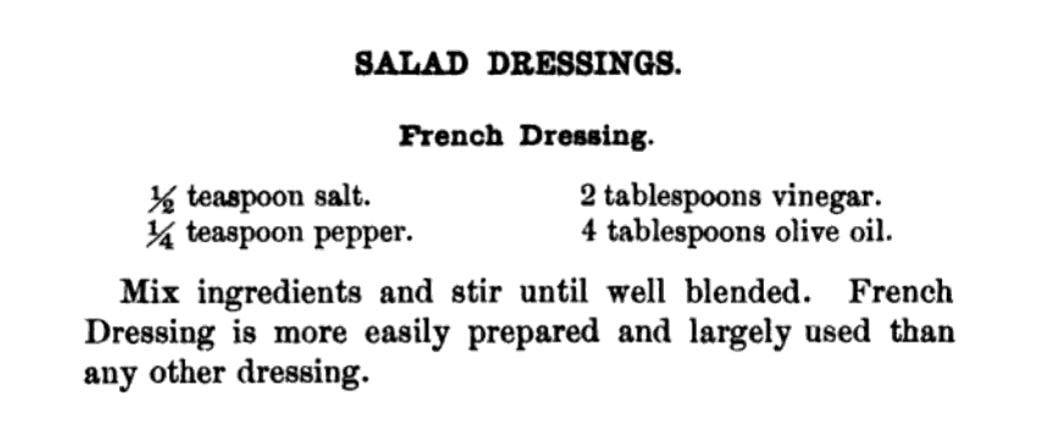

A lot of people like to claim that French Dressing is not actually French. And if you're defining French Dressing as the tangy, gloppy, red stuff pretty much no one makes from scratch anymore, you'd be right. But the devil is in the details, and even the New York Times has missed this little bit of nuance. This Times article, published before the final de-regulation went into place, notes, "The lengthy and legalistic regulations for French dressing require that it contain vegetable oil and an acid, like vinegar or lemon or lime juice. It also lists other ingredients that are acceptable but not required, such as salt, spices and tomato paste." (emphasis mine) What's that? The original definition of French Dressing, according to the FDA, was essentially a vinaigrette? What could be more French than that? In fact, that is, indeed, how "French dressing" was defined for decades. Look at any cookbook published before 1960 and nearly every reference to "French dressing" will mean vinaigrette. Many a vintage food enthusiast has been tripped up by this confusion, but it's our use of the term that has changed, not the dressing. Take, for instance, our old friend Fannie Farmer. In her 1896 Boston Cooking School Cookbook (the first and original Fannie Farmer Cookbook), the section on Salad Dressings begins with French Dressing, which calls for simply oil, vinegar, salt, and pepper.

She's not the only one. I've found references in hundreds of cookbooks up until the 1950s and '60s and even a few in the 1970s where "French dressing" continued to mean vinaigrette. You can usually tell by the recipe - composed salads of vegetables are the most common. If a recipe for "French dressing" is not included, and no brand name is mentioned, it's almost certainly a vinaigrette. So what happened?

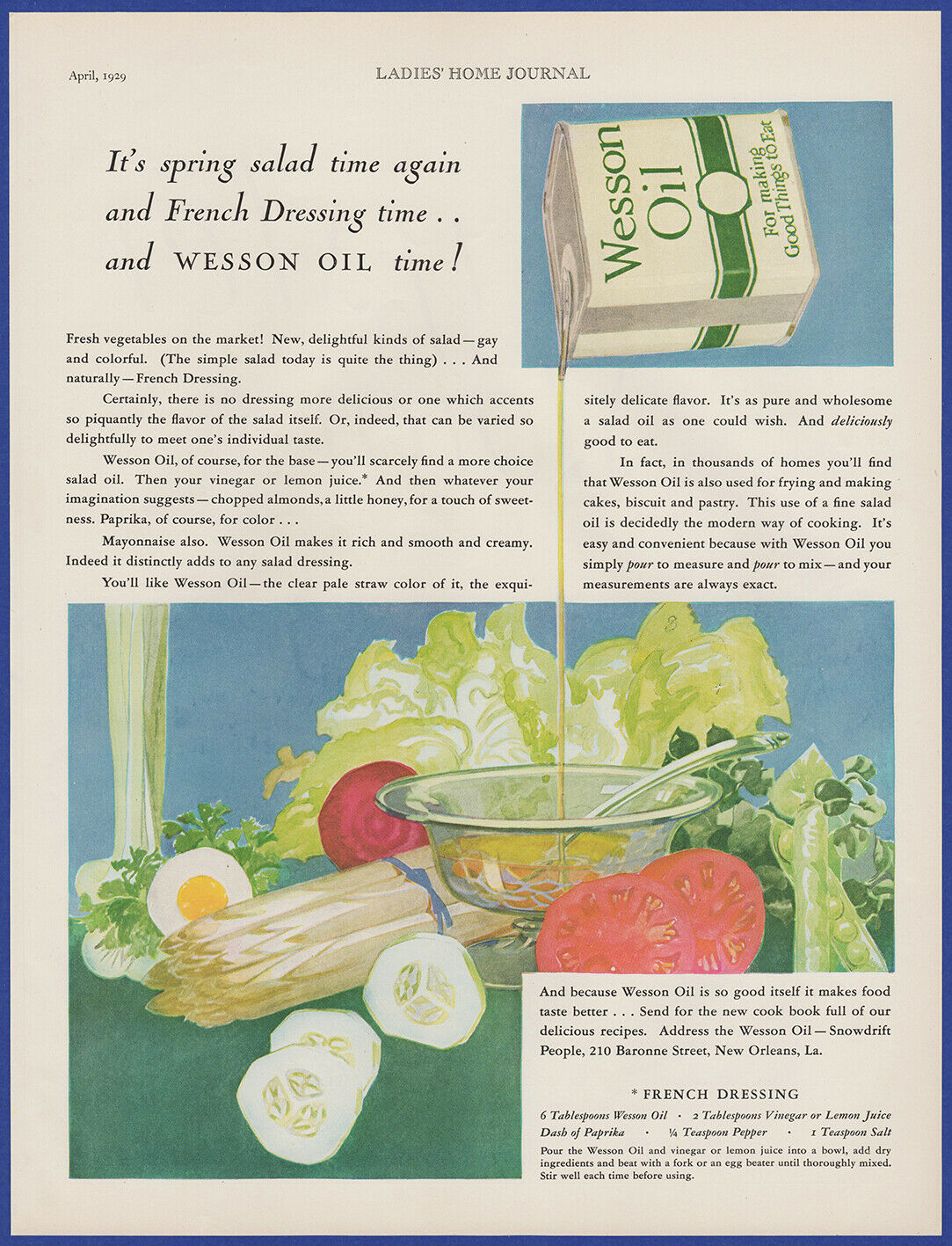

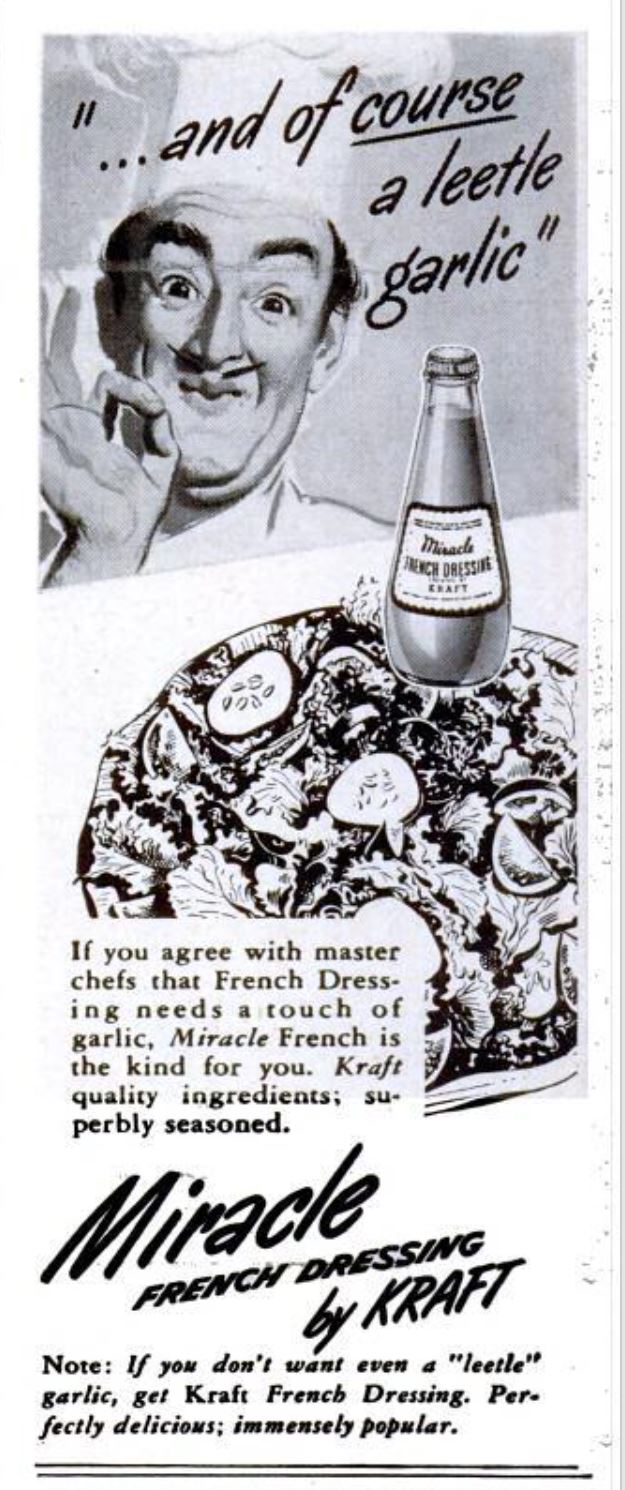

I've managed to track down the original 1950 FDA Standard of Identity for mayonnaise, French dressing, and salad dressing. In it, the three condiments are considered together and are the only dressings identified, likely because few if any other dressings were being commercially produced. Although the term "salad dressing" has been extremely confusing to many modern journalists, it is clearly noted in the 1950 standard of identity of being a semi-solid dressing with a cooked component - in short, boiled dressing. The closest most Americans get today is "Miracle Whip," which is, in fact, a combination of mayonnaise and boiled dressing. Generic brands are often called just "salad dressing" because it was often used to bind together salads like chicken, egg, crab, and ham salad, and also often used with coleslaw. So it makes perfect sense that "French dressing" would be the designated term for poured dressings designed to be eaten with cold lettuce and vegetables - i.e. what we consider salad today. People have wondered why we needed to regulate salad dressings, but there is one very important distinction in the 1950 rule - it prohibits the use of mineral oil in all three. Mineral oil, which is a non-digestible petroleum product (i.e. it has a laxative effect), and which is colorless and odorless, was a popular substitute for vegetable oil during World War II by dieters in the mid-20th century. I collect vintage diet cookbooks and it shows up frequently in early 20th century ones, especially as a substitute for salad dressings. Mineral oil is also extremely cheap when compared with vegetable oils, and it would be easy for unscrupulous food manufacturers to use it to replace the edible stuff, so the FDA was right to ensure that it did not end up in peoples' food. Mineral oil is sometimes still used today as an over-the-counter laxative, but can have serious health complications if aspirated. There were several subsequent addenda to the standard of identity, but most were about the inclusion of artificial ingredients or thickeners, with no mention of any ingredients that might change the flavor or context of what was essentially a regulation for vinaigrette until 1974, when the discussion centered around the use of artificial colors instead of paprika to change the color of the dressing. The FDA ruled that "French dressing may contain any safe and suitable color additives that will impart the color traditionally expected." So here we see that by the 1970s, the standard of identity hadn't actually changed much, but the terminology had. "French dressing" went from the name of any vinaigrette, to a specific style of salad dressing containing paprika (and/or tomato). When people started adding paprika is unclear, but it was probably sometime around the turn of the 20th century, when home economists began to put more and more emphasis on presentation and color. A lively reddish orange dressing was probably preferable to a nearly-clear one. In 2000, the LA Times made an admirable effort to track the early 20th century chronology of the orange recipes. By the 1920s, leafy and fruit salads began to overtake the heavier mayonnaise and boiled dressing combinations of meat and nuts. As the willowy figure of the Gibson Girl gave way to the boyish silhouette of the flapper, women were increasingly concerned about their weight, and salads were seen as an elegant solution.

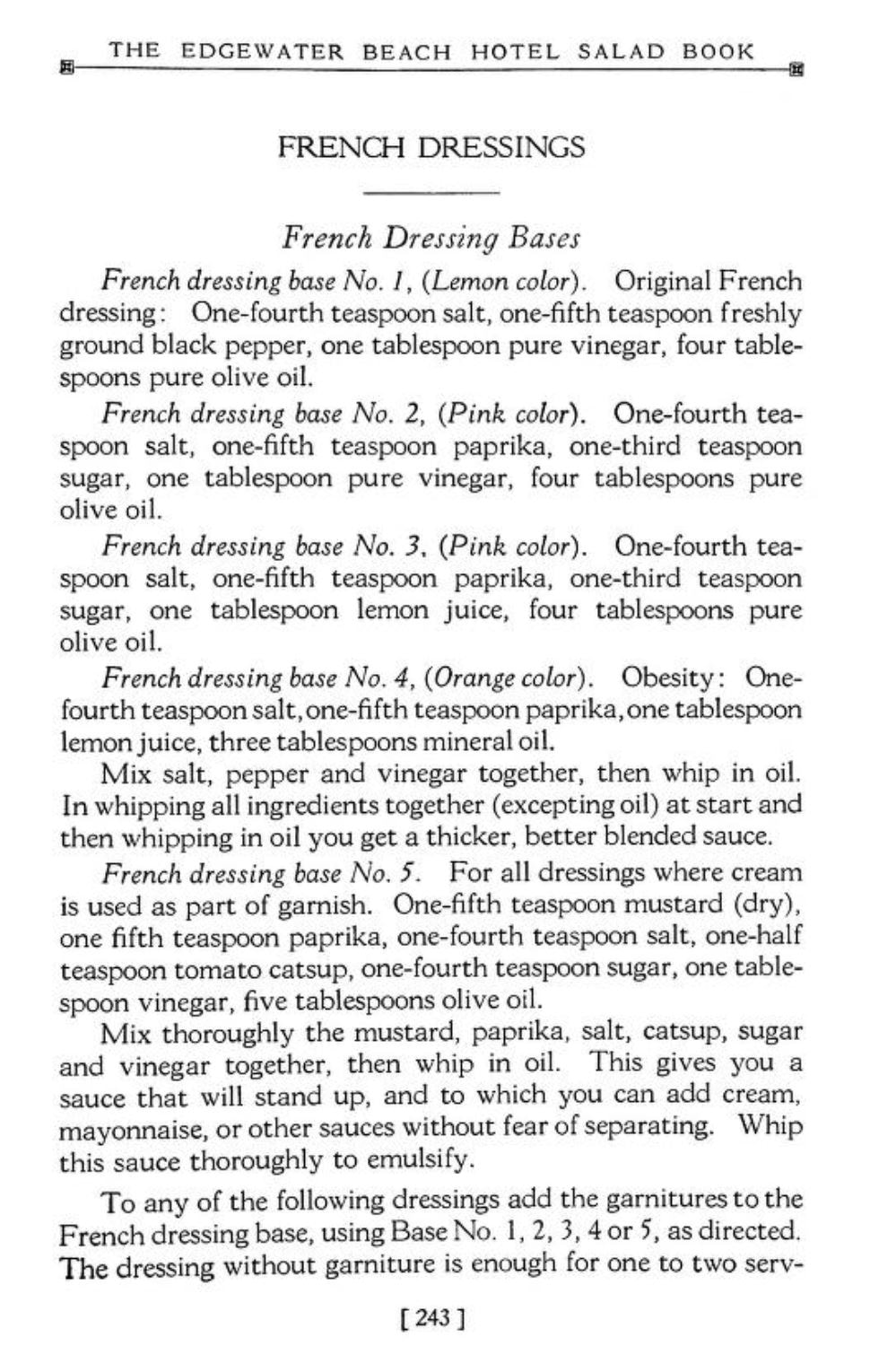

The recipes pictured above are from The Edgewater Beach Hotel Salad Book, published in 1928 (Patreon patrons already got a preview of this cookbook earlier in the week!). The Edgewater Beach Hotel was a fashionable resort on the Chicago waterfront which became known for its catering and restaurant, and in particular its elegant salads. You'll note that several French Dressing recipes are outlined (they are also introduced first in the book), and are organized by color. "No. 4 (Orange Color)" has the note "obesity" not because it would make you fat - quite the opposite - its use of mineral oil was designed for people on diets. Although the fifth recipe does not note a color, it does contain both paprika and tomato "catsup," and all but the original and "obesity" recipes contain sugar. An increase in the consumption of sweets in the early 20th century is often attributed to the Temperance movement and later Prohibition.

By the 1950s, recipes for "French Dressing" that doctored up the original vinaigrette with paprika, chili sauce, tomato ketchup, and even tomato soup abounded. My 1956 edition of The Joy Of Cooking has over three pages of variations on French Dressing. Hilariously, it also includes a "Vinaigrette Dressing or Sauce," which is essentially the oil and vinegar mixture, but with additions of finely chopped pimento, cucumber pickle, green pepper, parsley, and chives or onion, to be served either cold or hot. All the other vinaigrettes have the moniker "French dressing." A Google Books search reveals an undated but aptly titled "Random Recipes," which seems to date from approximately mid-century, and which includes a recipe for Tomato French Dressing calling for the use of Campbell's tomato soup, and "Florida 'French Dressing'," containing minute amounts of paprika, but generous citrus juices and a hint of sugar. So maybe people were making their own sweetly orange French dressing at home after all?

There is some debate as to who actually "invented" the orange stuff, but while Teresa Marzetti may have helped popularize it, the general consensus is the Milani brand, which started selling its orange take in 1938 (or the 1920s, depending who you ask - I haven't found a definitive answer one way or the other), was the first to commercially produce it. Confusingly, the official Milani name for their dressing is "1890 French Dressing." The internet has revealed no clues as to whether or not the recipe actually dates back that far, but a 1947 New York Times article claims "On the shelves at Gimbels you'll find 1890 French dressing, manufactured by Louis Milani Foods. It is made, the company says, according to a recipe that originated in Paris at that time and was brought to this country after the fall of France. This slightly sweet preparation, which contains a generous amount of tomatoes, costs 29 cents for eight ounces." This seems like a marketing ploy rather than the truth, but who knows for sure?

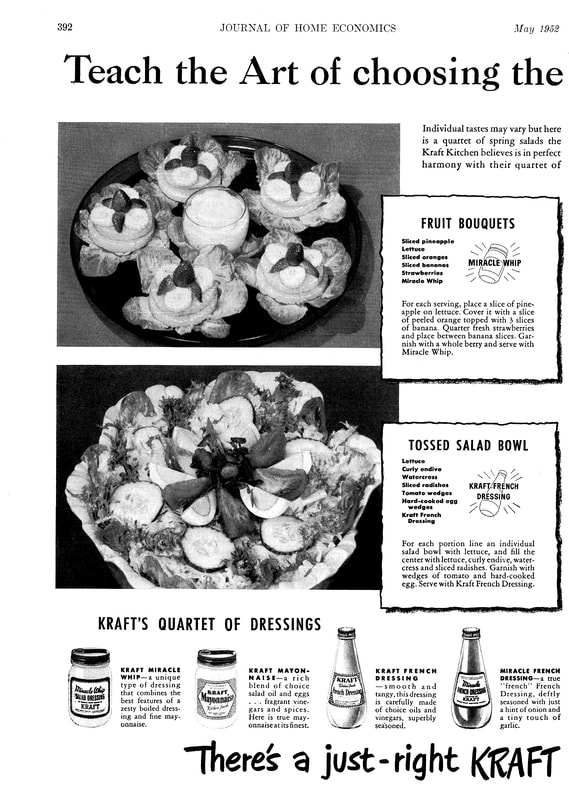

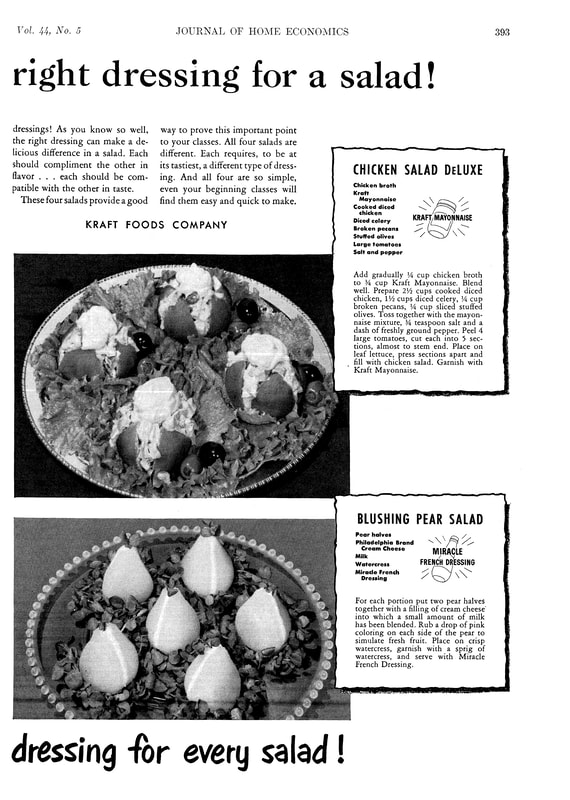

In 1925, the Kraft Cheese Company did sign a contract with the Milani Company to become their exclusive distributor. At least, that's what a snippet view of 1928 New York Stock Exchange listing statements tells me. As early as 1931 Kraft was manufacturing French Dressing under their name, and by the 1940s it had also used the Miracle Whip brand name to create Miracle French Dressing - which had just a "leetle" hint of garlic.

One snippet reference in the 1934 edition of "The Glass Packer" notes, "Differing from Kraft French Dressing, Miracle French is a thin dressing in which the oil and vinegar separate in the bottle, and which must be shaken immediately before using." Miracle French was contrasted often in advertising with classic Kraft French as being zestier, which may have led to the development in the 1960s of Kraft's Catalina dressing, a thinner, spicier, orange-er French dressing.

In fact, as featured in this undated magazine advertisement, Kraft at one point had several varieties of French Dressing including actual vinaigrettes like "Oil & Vinegar," and "Kraft Italian" alongside Catalina, Miracle French, Casino, Creamy Kraft French, and Low Calorie dressing, which also looks like French dressing. What you may notice is that the "Creamy Kraft French" looks suspiciously like most of the gloppy orange stuff you see on shelves today, and which generally doesn't resemble a thin, runny, paprika/tomato-red dressing that dominates the rest of this lineup.

"Spicy" Catalina dressing was likely introduced sometime around 1960 (although the name wasn't trademarked until 1962). Kraft Casino dressing (even more garlicky) was trademarked for both cheese and French dressing in 1951, but by the 1970s appears to have left the lineup. Here are a few fun advertisements that compare some of the Kraft French dressings:

Of course by the 1950s other dressing manufacturers besides Kraft were getting in on the salad dressing game, including modern holdouts like:

Although many people in the United States grew up eating the creamy orange version of French Dressing, it's mostly vilified today (aside from a few enthusiasts). Which is too bad. As a dyed-in-the-wool ranch lover (hello, Midwestern upbringing - have you tried ranch on pizza?), I try not to judge peoples' food preferences. And I have to admit that while I've come to enjoy homemade Thousand Island dressing, I can't say that I've ever actually had the orange French! Of any stripe, creamy, spicy, or otherwise. I'm much more likely to use homemade vinaigrette from everything from lentil, bean, and potato salads to leafy greens. So to that end, let's close with a little poll. Now that you know the history of French Dressing, do you have a favorite? Tell us why in the comments!

The Food Historian blog is supported by patrons on Patreon! Patrons help keep blog posts like this one free and available to the public. Join us for awesome members-only content like free digitized cookbooks from my personal collection, e-newsletter, and even snail mail from time to time! Don't like Patreon? Join with an annual membership below, or just leave a tip!

1 Comment

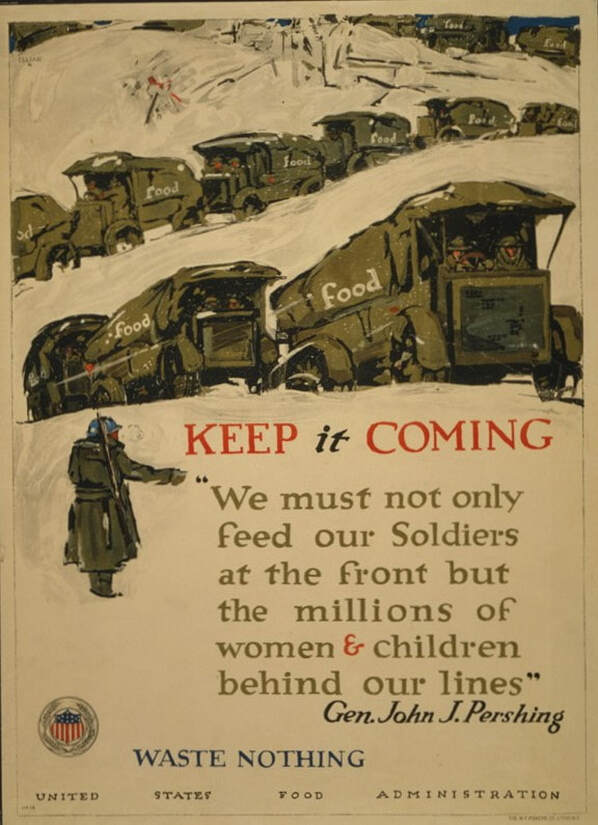

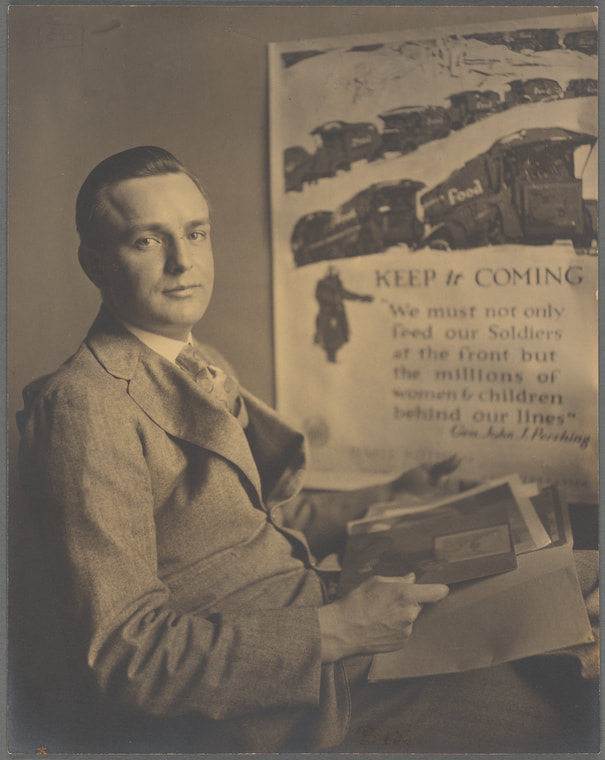

This poster features a long string of Army green military trucks labeled "Food" snaking through snow-covered hills, directed by a soldier. It reads "Keep it Coming" and features a quote by Gen. John J. Pershing - "We must not only feed our Soldiers at the front but the millions of women & children behind our lines." Underneath reads, "WASTE NOTHING" with the seal and title of the United States Food Administration. Almost certainly printed in the winter of 1917-18, the poster was designed by artist George Illian. "Keep it Coming" was apparently Illian's first poster for the war effort. He went on to design several others for the United States Food Administration, but none as striking as this one. Sadly, I was unable to dig up any information on Illian other than he was a member of the Society of Illustrators and that he did some commercial art after the war. He died in 1932, but I have not been able to find an obituary. The imagery from the poster would not have been unfamiliar to ordinary Americans who had been following the news. By the fall of 1917, American soldiers were in the fields of Europe, led by General John Joseph "Black Jack" Pershing. After three years of brutal war, France and Britain welcomed the Americans, led by Pershing with open arms in June of 1917, but it was not until October of that year that the main bulk of the American Expeditionary Forces would arrive in France. Although the United States had officially entered the war in April of 1917, military personnel numbered under 200,000, and military supply and tactics were largely stuck in the 19th century. It took months of stop-and-start mobilization to train American troops (sometimes with wooden rifles) and get them overseas (on borrowed ships). The winter of 1917-18 was one of the worst in recent memory during the First World War. On December 29, 1917, the New York Times reported "Cold Snap Over Entire East," reporting temperatures in upstate New York as low as 20 degrees below zero. New York Harbor froze, railroads were backed up across the Eastern seaboard, and Europe was engulfed in snow and freezing rain. The weather conditions meant that nearly all of the supplies for Europe and for major Eastern cities were completely backed up. On December 30th, the New York Times reported coal shortages in New England and New York, blaming railroad backups and the requisitioning of civilian ships and tugs for the war effort. The railroad backups resulted in the nationalizing of the railroad system under William McAdoo. Illian's poster reflects the winter conditions on the front lines, too. Although the true horrors of trench warefare were often glossed over by the press, by 1917 many Americans were hearing from their "boys" overseas first hand. Marching in the abnormally frigid cold and torrential rains of the winter of 1917-18 in Europe was familiar to most of the soldiers. While the Eastern U.S. was brought nearly to a standstill by railroad blockages, coal shortages, and frozen ports, Britain, France, and Spain also experienced unusually cold temperatures, high snowfalls, and blocked railroads in December, 1917 and January, 1918. Like many of the propaganda posters of the First World War, "Keep it Coming" exhorts ordinary Americans not only to conserve food for American soldiers overseas, but also to help feed women and children in Allied nations. "Waste Nothing" was part of a campaign to reduce food waste and free up additional supplies to send overseas. American supplies of wheat in particular were low in 1917, and only by reducing consumption could food stocks be freed up for shipment overseas until farmers could increase production. The idea of personal self-sacrifice was part of a larger movement during the war to fund the war effort (through the sale of liberty bonds) and to "do your bit" to help the war effort. By using the wintry backdrop, Illian brought home the message that while Americans might be suffering from cold at home, things were worse in Europe, and American soldiers were doing all they could to help end the war and alleviate hunger and hardship among people who had already suffered four long years of war. 1917-18 would be the only winter warfare most Americans would see in Europe - the war officially ended in November of 1918 - but while millions of soldiers were sent home after Armistice, many Americans would remain in Europe until the summer of 1919, part of the demobilization efforts and cleanup (including burial duty) after the war. The Food Historian blog is supported by patrons on Patreon! Patrons help keep blog posts like this one free and available to the public. Join us for awesome members-only content like free digitized cookbooks from my personal collection, e-newsletter, and even snail mail from time to time! Don't like Patreon? Join with an annual membership below, or just leave a tip! Tip Jar

$1.00 - $20.00

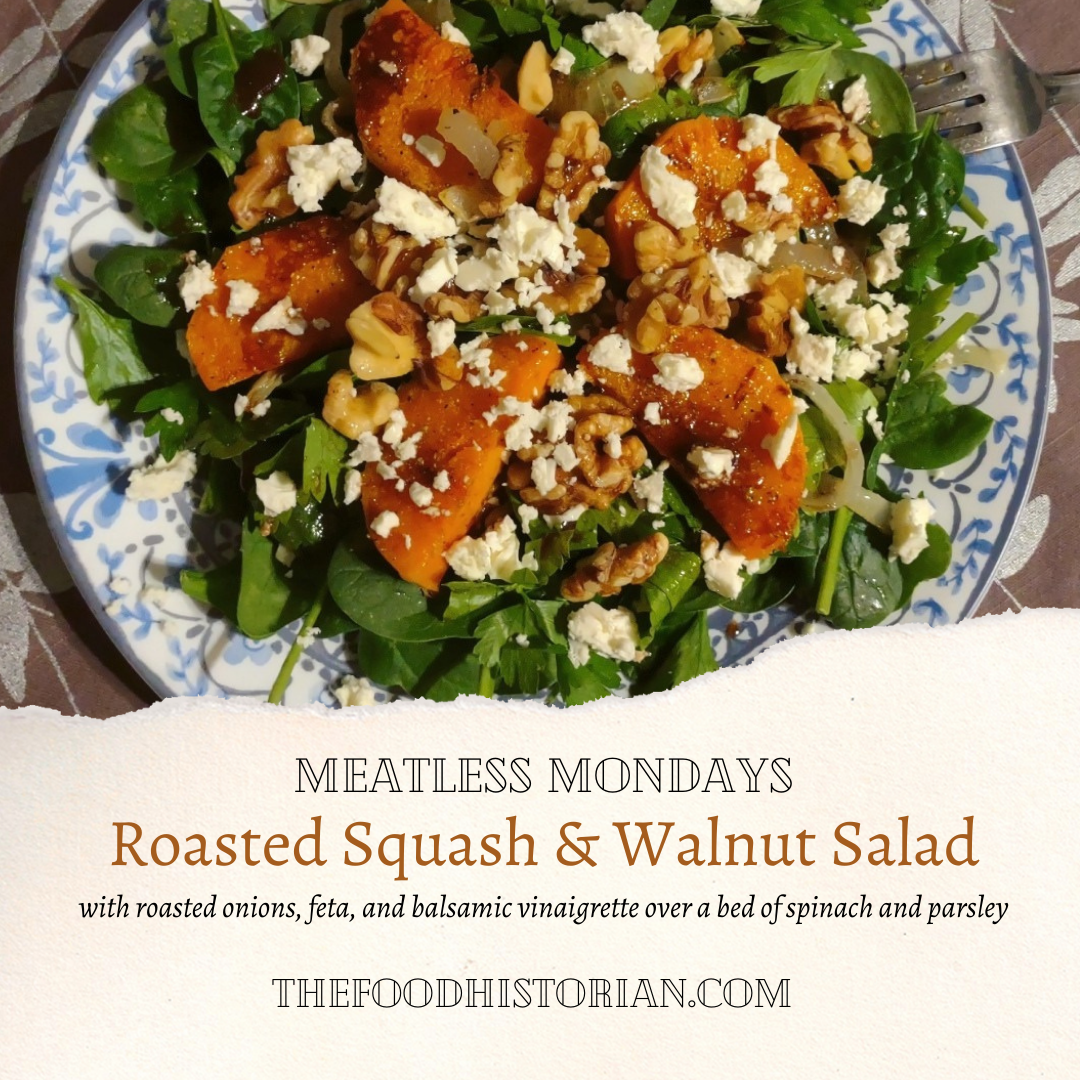

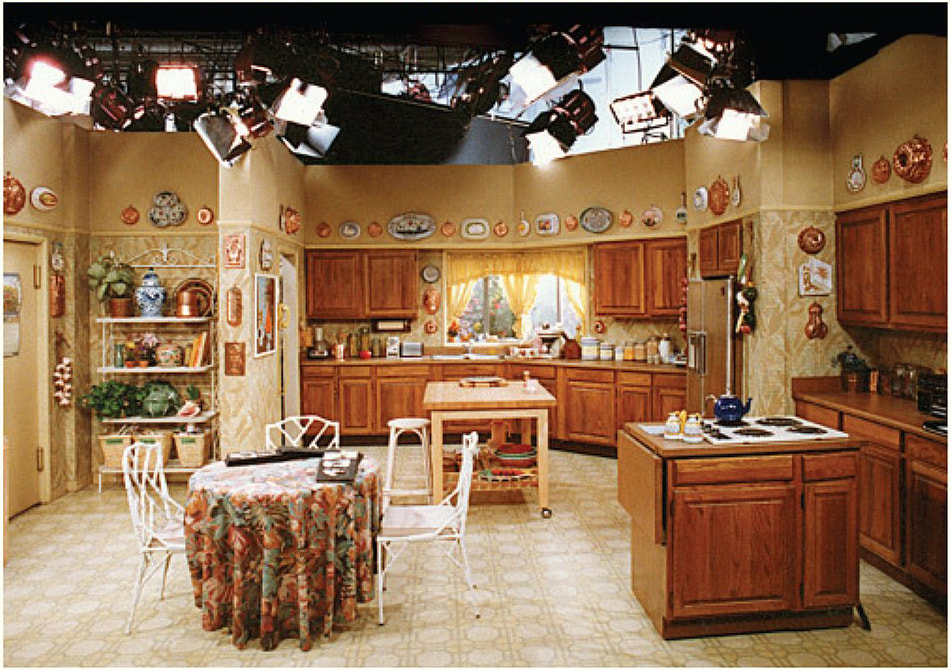

Like what you read, watch, or hear? Wanna help support The Food Historian, but don't want to commit to a monthly thing, or sign up for Patreon? Then you're in luck! You can leave a tip! This one-time (non-tax-deductible) donation helps keep The Food Historian going and pays for things like webhosting, Zoom, additions to the cookbook library, and helps compensate Sarah for her time and energy in helping everyone learn more about the history of food, agriculture, cooking, and more. Thank you! It's the depths of January. And after months of holiday eating, life can feel depressingly uninspiring when it comes to food. But while the imported tropical fruits beckon, it is possible to make a perfectly delightful dinner out of foods that are (mostly) in season here in the northeast. Enter the butternut squash. I'm typically not a huge fan. Butternut squash soup is usually much too sweet. Mashed squash is insipid and mealy. But when a Patreon patron posted about making Emily Nunn's delicata squash salad with parsley and walnut vinaigrette and raved about it, I was intrigued. I didn't have delicata squash, just one lonely little butternut left over from my impulse buy Thanksgiving CSA haul. I did have a big bunch of parsley, but I think it got a little frosty in the frigid temperatures we've been having lately, so bits were crispy and wilted. It would take some sorting. I also had a bottle of walnut oil I'd bought last year, and mostly hadn't used, which was set to expire in February. In the fridge, half a block of the most deliciously creamy, salty, made-in-New-York cow's milk feta (the sheep's kind and I don't get along) was languishing. Inspiration was striking. I'm an inveterate tinkerer when it comes to cooking. Even the respected science of baking usually has me asking, can I put fruit in this? Can I substitute some whole grain flour? Do I really have to beat the eggs for three whole minutes? Even as I don't mess with the ratios otherwise. So it's no surprise that I would be clinically unable to replicate Emily's recipe as she wrote it. The bones were good, though, so I stuck to those. Here's what I came up with: Roasted Squash & Walnut SaladThis recipe seems complicated, but once the vegetables are cut and in the oven, it's a fair amount of waiting. You can do a pan of dishes or start a load of laundry or watch most of an episode of your favorite television show while you wait. 1 smallish butternut squash 2 smallish yellow storage onions walnut oil pink salt garlic powder black pepper dried sage walnuts feta (the good-quality, locally made wet kind) fresh flat leaf parsley fresh baby spinach balsamic vinegar Dijon mustard maple syrup Preheat the oven to 400 F. Generously coat a half sheet pan with walnut oil (you can use olive or canola, if you prefer). Wash butternut squash and cut neck into one inch rounds. Cut in half and with a sharp knife remove the peel. I left the bulb end, cut it in half, scooped out the seeds, and roasted the halves whole with the rounds. Flip the half moons of squash in the oil so they're well-coated. Peel and halve the onions, cut into rounds, and add to the oiled pan. Combine about 2 tablespoons of pink salt, at least a teaspoon of black pepper, a few shakes of garlic powder and dried sage, and sprinkle the mixture all over the squash and onions. Roast for 30 minutes, flip, season again if you like, and roast for another 10 minutes or so, until the squash is crispy on one side and very tender, and the onions are tender. Scatter a generous handful of walnuts across the pan and roast another 3-5 minutes, until the walnuts are fragrant. Meanwhile, assemble your plate with the baby spinach topped with just the whole leaves of washed and dried parsley. Make a vinaigrette of about 3 tablespoons walnut oil, 2-3 tablespoons balsamic vinegar, and 1 tablespoon each Dijon mustard and maple syrup (add more syrup or a tablespoon of water if it seems too sharp). Top the greens with slices of squash, onions, and walnuts, drizzle over the vinaigrette, crumble feta on top, and serve while the vegetables are still warm. This salad is divine. The butternut squash came out silky and rich, the onions soft and not-too-sweet, the walnuts pleasantly crunchy, the parsley added some fresh, grassy tones to the milder spinach, and the sweet-sharp balsamic vinaigrette tied everything together. There was one slice of butternut squash left on the pan, so I tried it with some of the leftover onions and walnuts (which I stuffed in the cavities of the squash halves with the rest of the vinaigrette, for lunch tomorrow). To be honest, the squash was so good I could have eaten it just like that. But it really added so much satisfying heft to the salad. I don't think I'll ever make butternut squash any other way again. It was too delicious this way, and I could see it being the star of any number of other salads as well. It's hard to find satisfying, fresh recipes for winter eating that don't involve ingredients flown in from thousands of miles away. And while I love the wintertime treat of beautiful citrus, it's nice to be able to make something so delicious out of locally grown storage foods, too. I hope you enjoy this recipe as much as I did! The Food Historian blog is supported by patrons on Patreon! Patrons help keep blog posts like this one free and available to the public. Join us for awesome members-only content like free digitized cookbooks from my personal collection, e-newsletter, and even snail mail from time to time! Don't like Patreon? Leave a tip! Somehow, I missed the Golden Girls growing up. The show first aired in 1985, the year I was born, and went off the air in 1992, when I was seven. But despite the fact that it was apparently syndicated on broadcast television all through my elementary and high school years, I missed it. I did not watch a single episode. Oh, I knew that it existed, and by college, thanks to the virality of the internet, I got the references. I watched Betty White on Hot in Cleveland and watched with glee as she roasted William Shatner and essentially became a saint of the internet age. Thanks to the internet, I knew that Bea Arthur was a patron saint of LGBTQ+ youth, too. But I never saw the show, even when I finally did get access to cable. When Betty White passed away on December 31, 2021, just a little over two weeks shy of her 100th birthday (coming up on January 17th), I decided to see what all the fuss was about. Just one episode in, I was totally hooked. Rose reminds me of Minnesota (I almost went to St. Olaf!), I love Blanche's Southern charm and unapologetic sexuality, and while I'm not a huge fan of how often the show made fun of Bea Arthur's appearance, I appreciate Dorothy's whip smarts and New Yorker bluntness and sarcasm. And who could say no to firecracker Sophia? I've been binging episodes ever since. Thank goodness there are so many of them. But one thing that really struck me was the division of household labor, which features fairly prominently in the first few episodes, as well as subsequent flashbacks (once the gay male cook in the pilot episode disappears, that is). The ladies grocery shop together, and argue over what to buy. There's discussion of household budgets. When people come to visit, the ladies help each other clean. And someone or another is always in the kitchen washing dishes, cooking, or having a late-night snack. And although Sophia, with her small-village-in-Sicily background is queen of the Sunday gravy, other characters cook, too. The four ladies on the show are mature adults - they've all run their own households, raised children, managed husbands, etc. It can't have been easy for them to come to an agreement on how to run the house, but they did. And it reminded me very strongly of a passage I read in a book I now can't remember and can't find (the perils of a historian's mind. If anyone knows this reference, please let me know!) - it described a home economics college program where in their senior year, the girls lived together in a house and put into practice all the skills they had learned in class. But, as the author pointed out, the girls shared the workload together, which may have given them unrealistic ideas about the labor of managing their own households. In our last evaluation of memes, we talked about how convenience foods in the 1950s and '60s were in part adopted quickly in reaction to a reduction in available household labor. With no servants/hired help and fewer children, alongside changing expectations of childhood, more and more women were shouldering the burden of household labor alone. Which is why Golden Girls is so refreshing: four adults pulling together relatively equally to maintain a household and keep everyone fed. There are occasional hints at people's economic statuses. For one, if any of them were independently wealthy, I doubt they'd need roommates. But while Blanche having a nanny for her children becomes a plot point, as does Rose keeping a secret that her husband was terrible with money, Dorothy and Sophia seem chronically on a budget, unable to afford some of the things the others can. Although that may just reflect Sophia's addiction to the races. But still, everyone is able to afford a rather shocking amount of eveningwear and certainly there's always enough money to keep the fridge stocked with cheesecake. The women are all in their 50s and 60s in the show (Sophia purportedly in her 80s, although Estelle Getty was a year younger than Bea Arthur), which means that they were in high school in the 1940s or earlier. In particular, Rose mentions her dismay at being rejected for joining the WACs during WWII. That means they all likely had at least some home economics training in school. And while the show is quintessentially '80s, there are hints of the 1940s and '50s everywhere, from the décor to the clothing (especially the robes). That home economics training likely served them in good stead when living with other women. They probably all had similar experiences, maybe learned how to wash dishes or make beds or do laundry a certain way. Because despite the fact that the characters come from very different backgrounds, they celebrate their differences, instead of letting them divide them (for the most, part, anyway). Today, more and more Millennials, cash-strapped by an economy that underpays them and bogged down with student loan debt they were promised would get them good jobs, are joining forces to purchase or rent homes with fellow adults they aren't married to. And as my generation contemplates retirement, many of us have thought about purchasing homes or property in concert with friends (Boomers and Gen-Xers are, too). The family/friend "compound" is becoming more and more of a thing. Communal living certainly has a lot of historical precedence. The nuclear family is a lot newer (and less effective) than most "traditional family values" folks like to admit. Which features prominently in several Golden Girls plots as the ladies struggle with deadbeat exes, estranged children and siblings, and the sting of sexism and ageism. And while home ownership is still the American Dream for many people, it makes a lot of economic sense to share household resources and labor. In this housing market? Sometimes it's the only way people can afford a place of their own. Even in the 1980s, Miami was expensive, so roommates made as much sense then as it does in most cities now. But what makes the Golden Girls TV show work is the relationships the ladies build with each other, how they support each other, and how they work together. In our modern era, it's a lot harder to find community than it once was. So if you want something similar in your life or your future, tell any naysayers, "Hey! It worked for the Golden Girls!" Just don't forget to hash out your differences with honesty and lots of late-night snacks. The Food Historian blog is supported by patrons on Patreon! Patrons help keep blog posts like this one free and available to the public. Join us for awesome members-only content like free digitized cookbooks from my personal collection, e-newsletter, and even snail mail from time to time! Don't like Patreon? Leave a tip!

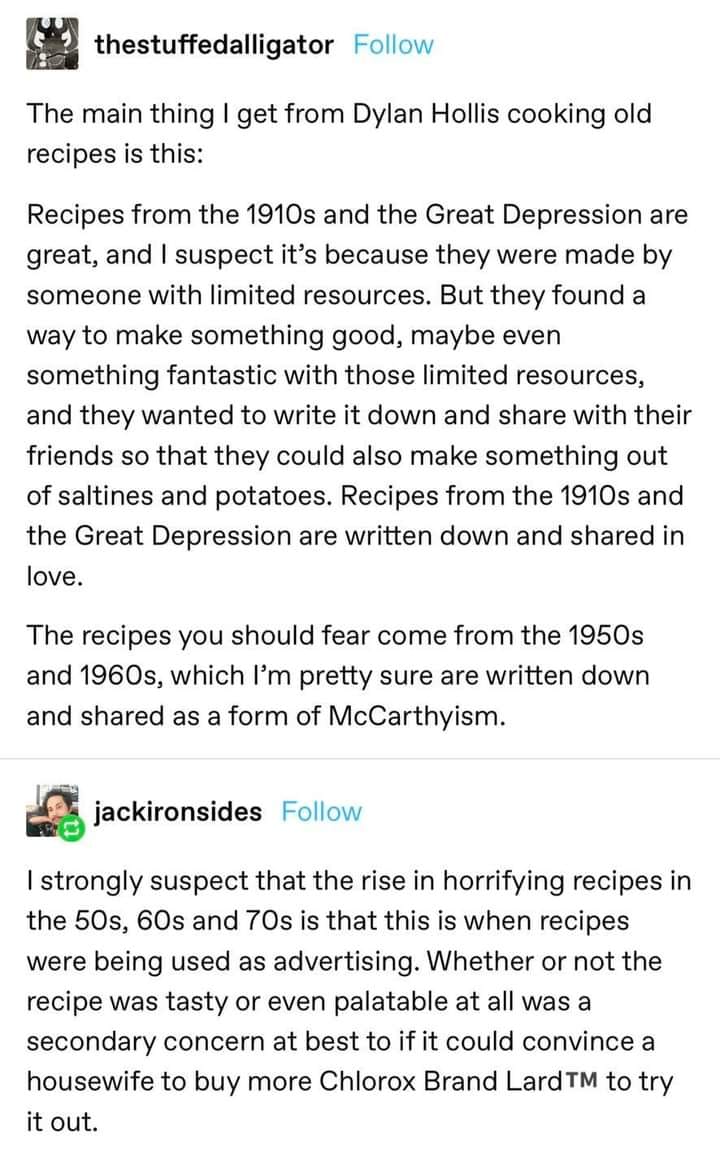

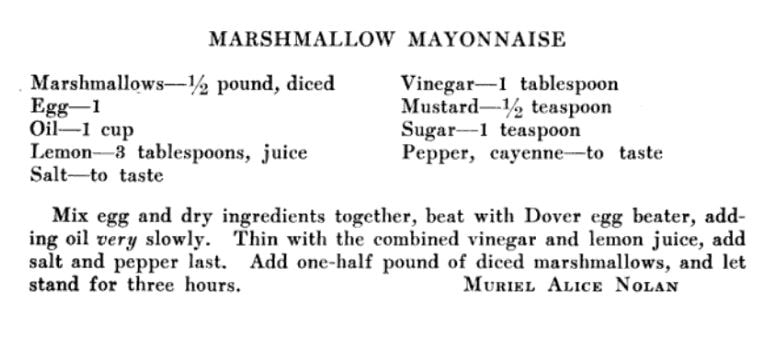

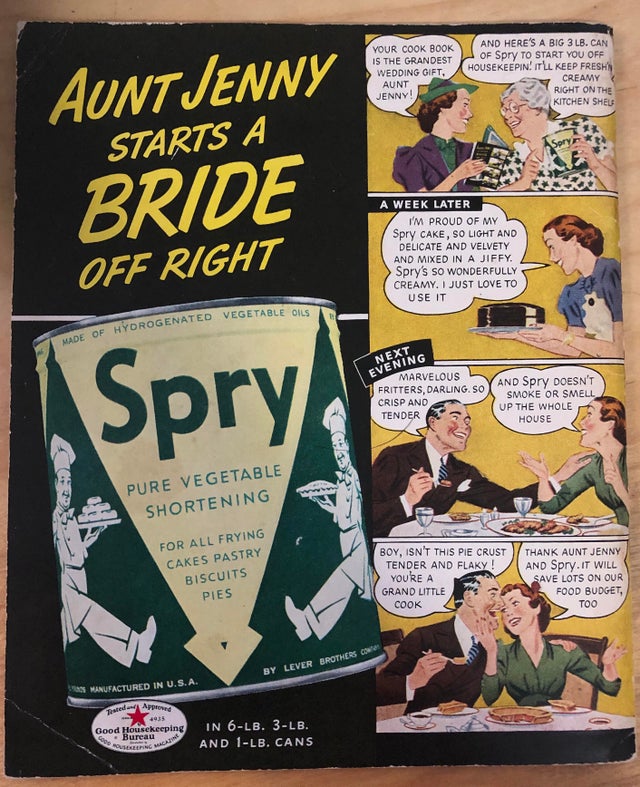

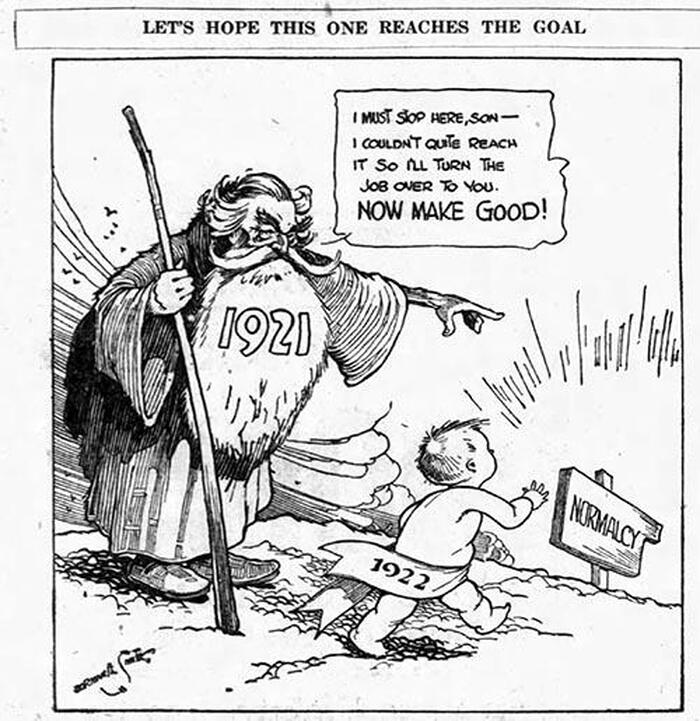

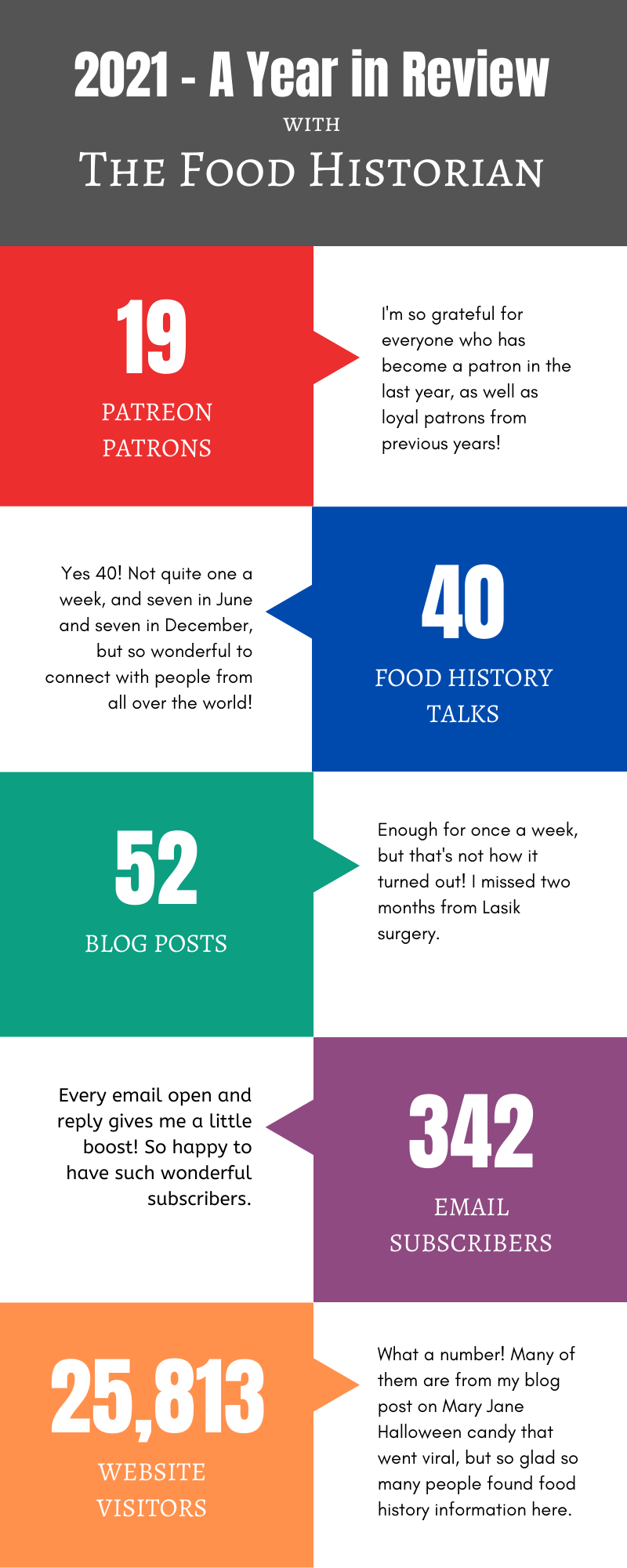

Well friends, I said I was contemplating a part two to last week's examination of 1950s food, and this meme kept popping up on my socials, so here we are again! This one isn't quite as inflammatory, and no fun illustration to catch your eye, but it makes a similar claim nonetheless. Here's the original text: The main thing I get from Dylan Hollis cooking old recipes is this: If you haven't seen any of Dylan Hollis' TikTok videos, I recommend them! He's hilarious. Not a food historian, but he cooks historic recipes and taste tests them. Some are horrific, but most are delicious - and while Dylan's reactions are 99% of the fun, his shock when things are actually tasty, while hilarious, does grate a little sometimes. Yes, people in the past really did know what they were doing! The meme claims that the food of the 1910s and the Great Depression were better than the 1950s, and were made with love, working with limited ingredients, whereas 1950s recipes were made to sell products during the McCarthy era. And while those ideas aren't necessarily wrong, they're definitely not the whole story. The time period of 1900 to 1950 is my favorite time period for cookbooks. They usually have decent instructions with things like measurements and oven temperatures, but are still from scratch. USUALLY being the key word there. Because starting in the 1870s, corporate food brands started publishing cookbooklets to sell their products. One of the earliest adopters of this sales tactic? Cottolene brand shortening. Not exactly lard, but pretty darn close! A lot of the corporate cookbooks and cookbooklets of the late 19th and early 20th century were primarily for ingredients. Different brands of flavorings and spices, baking powder, flour, shortening or lard, etc. were the main branded food products at the time. A lot of major food companies today started out as flour companies, including General Mills. So the cookbooks were largely normal scratch recipes that just recommended the cook or baker use the branded ingredients, but it was easy to substitute whatever you had on hand. And then, we started to get corporate food products like Campbell's canned soups, and Libby's canned corned beef, and powdered Knox gelatine and Jell-O, and other foods that were closer to finished foods already. You can only eat so much soup in a week. So how was Campbell's to get people to eat more of it? In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, we had more and more women graduating from food and nutrition schools and college programs. Domestic scientists and expert cooks and home economists happily filled the role of cookbook authors and test kitchen managers for food corporations. Which is how we got things like tomato soup spice cake (Dylan Hollis does a recipe from the 1950s, but it was actually invented in the 1920s!), cream of whatever soup casseroles, and marshmallow mayonnaise. While tomato soup spice cake is probably delicious (at least, Dylan Hollis thinks it is!), and cream of whatever soup is a lot easier than white sauce, I'm not sure about the marshmallow mayonnaise, but the cookbook says to serve it with fruit salad, so maybe it is? Who am I to judge? The point being, by the 1910s, there were plenty of marketing cookbooks and advertisements with recipes for processed foods for housewives to choose from. And while home economists were cranking out recipes that were sometimes smash hits and sometimes abject failures, there was a bit of a storm brewing in households around the country. Mainly, the "servant problem." For most of the 19th century, middle and upper-middle class families had at least one household servant (or enslaved person, prior to the Civil War) who did the bulk of the heaviest household labor. Middle class women and their daughters did household work too, but were generally spared things like scouring pots and scrubbing floors and hauling water and coal. But at the turn of the 20th century, we started to get pink collar jobs - being a shop girl or secretary or teacher or nurse was preferable for many women to the 24/6.5 schedules of being in service. Rural families usually had lots of children to help with agricultural labor, but in a family of 6 or 10, the older girls always helped care for the younger children and everyone did household chores. As families shrunk and household servants became harder to find and more expensive, more and more women had to do with less and less help at home. At the same time, education levels for women were rising. Girls stayed in school beyond the elementary level and attended high school and college in larger and larger numbers. Many parents also wanted better lives for their children than they had, and wanted to spare girls the drudgery of household labor. Upper and upper-middle class girls, in particular, had been raised in households with servants and mothers who spared them all but the basics of running a household. So when they married, all of a sudden girls with college educations had to figure out household budgets and weekly grocery shopping and cooking on their own, without many skills or resources to help them. Enter the ad man and the home economist. Swearing to save the clueless young bride from a lifetime of drudgery, while still pleasing her husband, all sorts of companies targeted young, inexperienced women just starting their households, but none perhaps as diligently as Spry, which manufactured first lard and later shortening (there's that lard reference again!). Aunt Jenny was the fictional grandmotherly character who knew just everything and would teach it all to her clueless niece. And of course, the secret was always a giant can of Spry. While Spry cookbooklets joined the legion of competitors, it was their cartoon-style print ads and extensive radio shows and advertisements that helped sway millions of American women to the Spry way of life. Is it any wonder that women who married in the 1930s and '40s raised children in the 1950s on corporate foods? Untrained, without the household help of their mothers and grandmothers, and with high expectations for home cleanliness and cooking three meals a day, 364 days a year would be enough to drive anyone into the arms of kindly home economists and fictional characters like Aunt Jenny, Mary Lee Taylor, Betty Crocker, and others. Recipes as advertisements for corporate foods did NOT start in the 1950s by any means. But the meme is somewhat correct in that scratch cooking was more prevalent in the Great Depression in particular, largely because at the time industrial foods were still more expensive than cooking from scratch, and because women who were adults in the 1930s were more likely to have been born into households that still taught them something about cooking and household management. And although the balance of population in the United States tipped from rural to urban in the 1920s, we still had a huge population of people primarily involved in agriculture, meaning families were larger (my mom's parents, born to farmers in the 1930s, came from families of 9 and 10 children, respectively), so women had more household help. Rural areas were also slower to adopt new fashions, including fashionable food, and often had less access to industrial goods of all sorts, including processed foods. Rural families were also much more likely to grow and preserve the bulk of their own food, well into the 1970s, than the rest of America. If you had land and free labor, it was certainly cheaper than buying commercially canned goods. If your grandmother grew up in a rural area during the Great Depression, like mine did, she probably learned how to cook from scratch. But by the 1950s, she was raising kids on her own, and maybe had a career of her own, or was supporting her husband's career, which meant less time to cook from scratch as she cared for her own children and a house with higher standards of cleanliness and fashion than her mother's with a lot less help. At the same time, in the 1950s, the general consensus was that industrial foods were the wave of the future - they were boons to help a busy housewife, not things to be scorned and rejected. And as incomes rose, it was much easier to purchase foods than doing your own home preserving. And while the Great Depression did result in a lot of creative cooks (banana bread, for instance), I find the mention in the original meme of Saltines ironic. Although Saltines and cracker companies like Ritz didn't invent cracker-based mock apple pie (that dates back to the 1850s, believe it or not), they sure hopped right on that bandwagon and used it as a selling point. Necessity is the mother of invention. But rising incomes are the mother of convenience. And while McCarthyism probably did prevent the spread of some delicious and interesting foodways through its xenophobia and rigid conformity, the road to corporate convenience foods was a long one. They didn't appear overnight once the calendar ticked over from 1949 to 1950. Indeed, scratch cooking and baking continued well into the 1950s, and many of the foods we associate with the 1950s (Cool Whip, anyone?) weren't actually invented until the 1960s. For instance, the Pillsbury Bake-Off baking contest didn't start until 1949, and while modern incarnations of the contest are usually dominated by mutated versions of whatever convenience food Pillsbury has cooked up (usually crescent rolls or cinnamon rolls or canned biscuits), the original contest was meant to promote Pillsbury flour, so the recipes are all from scratch. And looking at my food historian library shelves, the 1950s section has plenty of community cookbooks filled with can-of-this, box-of-that recipes, and advertising cookbooklets galore, but there are also cookbooks like The Magic in Herbs (first printed in 1941 but on its seventh printing by my 1950 copy) and The Peasant Cookbook (1955, and my copy was from the library of the Ladies' Home Journal!), and Whole Grain Cookery (1951) and those community cookbooks always had scratch recipes in them, too. And my 1930s section? I have more corporate cookbooklets from the 1930s than any other era! Like most of history, individual decades might be changed and marked by big events, but history is complicated. In the Progressive Era we had brutal strikes and food riots, but we also had Gibson Girls and Vanderbilts and Rockefellers. During the Great Depression we had the Dust Bowl and migrant workers, but we also had the glamour of Hollywood. And yes, in the 1950s we had McCarthyism (and sexism and racism) and processed food, but we also had folks like James Beard and Julia Child and plenty of scratch cooking. So let's stop stereotyping decades and accept them for what they are - complicated, messy, and fascinating time periods with both good food and bad. And the next time you see a corporate food cookbook from the 1950s - give it a gander. You might be surprised by what you find inside. There are good recipes in just about every cookbook, if you take the time to look. The Food Historian blog is supported by patrons on Patreon! Patrons help keep blog posts like this one free and available to the public. Join us for awesome members-only content like free digitized cookbooks from my personal collection, e-newsletter, and even snail mail from time to time! Don't like Patreon? Leave a tip! It's hard to believe it's already 2022. Another year has come and gone, and we're still in a global pandemic. A few days ago this political cartoon from 1921 was posted on Reddit and a whole host of other social media pages. It ended up in my newsfeed and seemed particularly apt. I've written before on the comparisons between a century ago and today (here and here), but the longer the pandemic drags on, the more the comparisons seem spot on. "A return to normalcy" was the slogan of Warren G. Harding's 1920 political campaign. It promised that Americans could ignore all of the scary things that had happened since 1917, when the U.S. entered the First World War. Although his rhetoric about a return to the mythic, bucolic past (sound familiar?) he won the election by a landslide. Unfortunately for Americans, his strategy of conservative (in the original definition) rhetoric and laissez-faire deregulation after the federal control of World War I ultimately failed. The United States didn't return to pre-WWI normalcy, and while the deregulated economic boom lifted some boats very high, it left other Americans in the lurch and completely on their own. Harding's successors largely followed his economic plans, including World War I Food Administrator Herbert Hoover, who ended up overseeing the crash of 1929 and the onset of the Great Depression. While I don't think we're headed for another Great Depression (for one, our social safety net is far better than the non-existent one of the 1920s), there has been a strong social reaction to the pandemic that is similar - a craving for a return to normalcy of our own, of wanting the pandemic to be over before it is, and of ignoring many of the traumas it has inflicted on us individually and collectively. I've felt that a lot this past year. After the frenetic pace of working on reduced hours through the 2020 lockdown, desperately trying to squeeze everything into fewer hours and pushing myself to be more and more efficient, 2021 has taught me the importance of rest. I'm not always very good at taking it, but these last few weeks I've tried my best to not feel guilty about sleeping in and doing nothing, even as I can't stop myself from commenting on food history memes! 2021 was less frenetic than 2020, but it was a lot. Here's the year by the numbers: Welcome to our new Patreon members, Susan, Elizabeth, Becky, Phyllis, Steve, and Deborah! It's been lovely having your support! I did FORTY separate food history talks in 2021. All but one was virtual, thank goodness, but it meant that being The Food Historian essentially amounted to a second job on top of my museum day job. And although they weren't quite once a week (there was a blank spot in July and August after I got Lasik surgery), I did actually post exactly 52 blog posts in 2021. Those of you on my email list have hopefully enjoyed regular blog posts in your inbox and look at those website visit numbers! A few things didn't make it to the end of 2021 - Food History Happy Hour had to be sacrificed to the lecture gods, sadly. We made it to June, but Lasik surgery derailed things. Although I'm very happy with my new eyes and giving up glasses after 25 years, recovery took longer than expected. Guess it was 2021 telling me to rest again. Despite the two month break, I'm very happy with how many posts I completed! Here's the top ten of the year. Top 10 Blog Posts of 20211. The Real Story Behind the "Gross" Black and Orange Halloween Taffy I posted this one in the fall of 2020 just before Halloween, but it was by far the most popular, racking up over 9,000 unique pageviews. A number of older blog posts were also popular, but this is a review of 2021, so I'm not including the others! 2. Before Nestle: A History of White Chocolate I posted this one on Valentine's Day. And while it was a bit of a slow burn, it was the most popular of my 2021 blog posts. Inspired by a comment about who "invented" white chocolate, it sent me down the research rabbit hole. 3. Visiting Home & a Brief History of North Dakota Caramel Rolls, a.k.a. Dakota Rolls This was my first blog post after Lasik surgery and after a trip home. I hadn't been home in several years, and seeing (and eating!) giant North Dakota-style caramel rolls made me wonder what the history was, but there wasn't much on the internet, so I wrote one! 4. What's the Difference Between Hot Chocolate and Hot Cocoa? With Recipes! One of the first posts of 2021! Posted in conjunction with a talk I do on hot chocolate, this was a fun one to put together, and answered a burning question! 5. When Kitchens Worked: The Rise and Fall of Functional Kitchens This post was inspired by a wonderful 1940s film on YouTube outlining the ideal kitchen layout. I fell in love, and clearly other folks did, too! 6. Meatless Monday: Easy Rice Pudding 2021 was a year for comfort foods, and this simple recipe was one of my favorites. Clearly it resonated with other people, too. 7. World War Wednesday: The Mystery of Carter Housh I originally wrote this post in 2020, but the mystery kept bugging me. In 2021, I decided to revisit Carter Housh's biography, tracking down little snippets and finding as much information as I could! It inspired me to do research on subsequent poster artists for WWI and WWII. 8. Food History, Slavery, and Juneteenth This one was a look into some of the quintessentially American foods created by enslaved people and made accessible by the global slave economy. 9. World War Wednesday: Eat More Milk It's always interesting to see which post make the list, and I think this one is in the top ten solely because of the stunning WWI poster. 10. Making Their Own Way: Black Women Cooks in the 19th Century This was one of my favorite posts of the year, and I'm so glad it made the top 10! It was inspired by the compelling story of the first known published Black woman cookbook author - Malinda Russell. I did also make some progress on last year's goals! Once again the uncertainty of the pandemic and the nation's attempted return to normalcy meant I didn't have a ton of mental space to work on the book, although I have gotten several tasks done and I'm getting ever closer to completion. I did, however, get my bookshelves up and my library organized!  My filled library bookshelves! My filled library bookshelves! Getting my library catalog updated is going to take a little longer (anyone want an internship? Lol.). But having spent the last year working from home two days a week my little garret office is as cozy as can be, with lovely lamps and my matching bookcases, and a little green velvet chair and footstool, and a vintage-looking bluetooth speaker for lovely music. And for Christmas I got an ergonomic cushion for my chair and my husband got me a very fancy second monitor, which will make transcribing newspaper articles and editing videos so much easier! And although getting published in the popular press was NOT one of my goals for 2021, it happened anyway! I was invited to select historic cookies and write about them for TheKitchn.com, and an editor friend asked me to write for a local arts weekly back home. The pieces were published in December and you can find them below:

My goals for 2022 are more modest. Make progress on the book (hopefully finally finish!), keep up the blog, and try to get some more work published. I've got lots of post-book plans, so go to hurry up and turn it in to the editor! A friend of mine chooses a word every year to aspire to. This year I decided to follow suit! My word of the year is "cultivate." Appropriate for a food historian and someone who is hoping to start a garden this spring. But it also represents the slow, steady pace of growing The Food Historian, planting seeds for the future, and, in terms of the book manuscript, weeding! If you pick a word of the year, tell me in the comments! 2021 wasn't a dumpster fire for me, but the last two years have been pretty destabilizing, globally. I hope you'll all be a little kinder to yourselves and the people around you. Try to get some more rest, sleep in, drink lots of water, get outside, stretch every now and again, and do the things you love. Here's to a year of finishing what we start, and making a new beginning, rather than trying to go backwards. Normalcy is overrated. The Food Historian blog is supported by patrons on Patreon! Patrons help keep blog posts like this one free and available to the public. Join us for awesome members-only content like free digitized cookbooks from my personal collection, e-newsletter, and even snail mail from time to time! Don't like Patreon? Leave a tip!

|

AuthorSarah Wassberg Johnson has an MA in Public History from the University at Albany and studies early 20th century food history. Archives

July 2024

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed