|

This post contains Amazon affiliate links. Summer Kitchens Recipes and Reminiscences from Every Corner of Ukraine by Olia Hercules had been on my wish list for a while. Released in 2020, it seemed like just exactly the kind of cookbook I would like - interesting recipes linked with interesting stories. When Russia invaded Ukraine in late February, and Olia Hercules became a defacto spokesperson for Ukrainian foodways, I decided to finally purchase it. I'm quite picky about cookbooks, and it takes a lot to impress me. The recipes need to be familiar but surprising, introducing me to new techniques and especially flavor combinations. The headnotes have to be robust, the recipes not too finicky, and the storytelling excellent. Summer Kitchens manages to meet and exceed all of these requirements. It's really quite a stunning little book. Olia is just a year older than me, was born and spent most of her childhood in Ukraine. At age 12 her family moved to Cyprus for her asthma, and as a young adult she moved to London to study, where she lives today. She started her career in film, and it shows through her storytelling. She also worked as a professional chef, including for Ottolenghi's. Summer Kitchens is her third cookbooks. Her first, Mamushka: Recipes from Ukraine and Eastern Europe, was published in 2015, and her second, Kaukasis The Cookbook: The culinary journey through Georgia, Azerbaijan & beyond, was published in 2017. Her fourth cookbook, Home Food: Recipes to Comfort and Connect, is due to be released in December of this year. Although I haven't read her earlier cookbooks, I did have the opportunity to flip through Mamushka in a bookstore the other day, and I have to admit it wasn't as appealing as Summer Kitchens. I think that's in part because Summer Kitchens is all about that indefinable longing for a home you only knew for a little while. Like Olia, and many of the authors of letters she includes in the back of the book, I have memories of rural idylls as a child. Mine were of visiting my great-grandmothers in rural North Dakota in the summer. Of enormous gardens where I learned that peas actually aren't so bad if you eat them fresh and sweet right from the pod. Of old-fashioned flowers, and dirt cellars full of glass jars of preserved food. Of freshly-turned black dirt in the potato patch so soft it was perfect for bare feet to make impressions. Of homemade baked beans (my first ever taste) and fat, nutmeg-scented donuts and homemade pickles and sweet water buns with bright red chokecherry jelly. Of rhubarb custard cakes and the world's best North Dakota red mashed potatoes. Of playing beneath enormous cottonwood trees with their rustling leaves, and searching the quiet gravel roads for agates and quartz and petrified wood. Olia's reminiscences are a little different, but they still resonate. Sunny days in gardens, preserving food for winter, helping grandmas and moms clean fruit and chop vegetables. Memories of delicious homemade foods, special holidays, and especially the pich - the enormous brick and tile stoves that are common in many northeastern European countries, including my ancestral Scandinavia. The cookbook itself is divided seven chapters of recipes, preceded by essays on the summer kitchen and Ukraine's unique food regions. The chapters are:

Although the chapter on fermenting will likely make Americans flinch slightly (Summer Kitchens was published in the UK, which apparently does not have as stringent rules about food preservation advice as the U.S.), the recipes sound amazing, and several don't require preservation at all, including the intriguing-sounding smoked pears (and plums). I was interested to see that Hercules included watermelon molasses in the cookbook. Her headnotes indicate that she included it more for posterity than for anyone to use it, but sweet watermelon paste is still used in some areas of North Dakota, where Germans from Russia immigrants left Ukraine for the Northern Plains. Although it is definitely not a vegetarian cookbook, many of the recipes are vegetarian. This reflects in part the background of the people who developed this cuisine - meat was not always abundant, and vegetables often were. But also, as Hercules mentions, her husband is vegetarian, as are many of her friends, and so she cooks vegetarian often. This was incredibly refreshing for me to see. I am not vegetarian, but enjoy vegetarian food and am always looking for new recipes. Some, like cucumbers in sour cream are familiar. Others, like a tomato mulberry salad with red onion and purple basil are stunningly beautiful and sound delicious. Even the meat recipes, which I usually find boring in most cookbooks, are inviting, like the slow-roasted pork with sauerkraut and dried fruit. Fatty pork gets rubbed with spices and then cooked slowly in the oven with sliced onion, sauerkraut (homemade, of course), prunes, dried apricots, apples, and toasted caraway, coriander, and fennel seeds. Olia recommends fending off greedy guests to ensure enough leftovers to stuff into a sweet bun recipe also included in the cookbook. With the exception of pistachio napoleons and poppyseed babka, the dessert recipes are also unfussy and delicious-looking. A caramelized apple ricotta cake, classic potato-dough dumplings stuffed with halved plums and served with honey, steamed bilberry-stuffed donuts rolled in crushed walnuts and sugar. Summer Kitchens is not just about summer cooking. It is about how summer kitchens have been used throughout Ukraine historically, how they continue to be used, and what they represent. It's no accident that Hercules starts her book in September, with preserving season. Because the summer kitchen is also a reflection of the summer garden. Many recipes, especially in the first chapter, reflect an abundance of produce that most of us no longer have access to. Hercules even notes this change in her essays, noting in one how dismayed a young Ukrainian was to find her uncle had dropped a forty pound sack of cucumbers off on her front step. Instead of joy at the opportunity to turn free produce into pickles, the young woman saw only work and the guilt to do something with the cucumbers before they went bad. And therein lies the rub. While Hercules has managed to produce an amazingly atmospheric and even cozy cookbook full of recipes any home cook with a little ambition could produce, it is also a love letter to a way of life many would say is dying. Hercules herself admits that her beloved pich ovens are increasingly being torn out for more modern appliances, and summer kitchens are being converted or torn down. It's easy to romanticize the past, to the frustration of those trying to still live it. But in a day and age when whole generations dream of giving up the rat race and settling in a little rural cottage with a big garden, Olia Hercules' depictions of Ukraine can sound like paradise. And perhaps it is. But in a time when Ukraine is being torn apart by war (again) and threatened with hunger (again), Summer Kitchens reads more like a love letter to what every Ukrainian would love to have, but can never seem to grasp for long. Serfdom, World Wars, collectivism, famine, invasion, Sovietization - all these have threatened but never quite destroyed the Ukrainian garden of Eden. But like most old foodways, Ukrainian food is threatened by modernity. I'm hopeful that books like Summer Kitchens will help keep them alive. The Food Historian blog is supported by patrons on Patreon! Patrons help keep blog posts like this one free and available to the public. Join us for awesome members-only content like free digitized cookbooks from my personal collection, e-newsletter, and even snail mail from time to time! Don't like Patreon? Leave a tip! If you'd like to learn more about Ukraine, food history, and politics, check out my new Substack newsletter - Historical Supper Club.

0 Comments

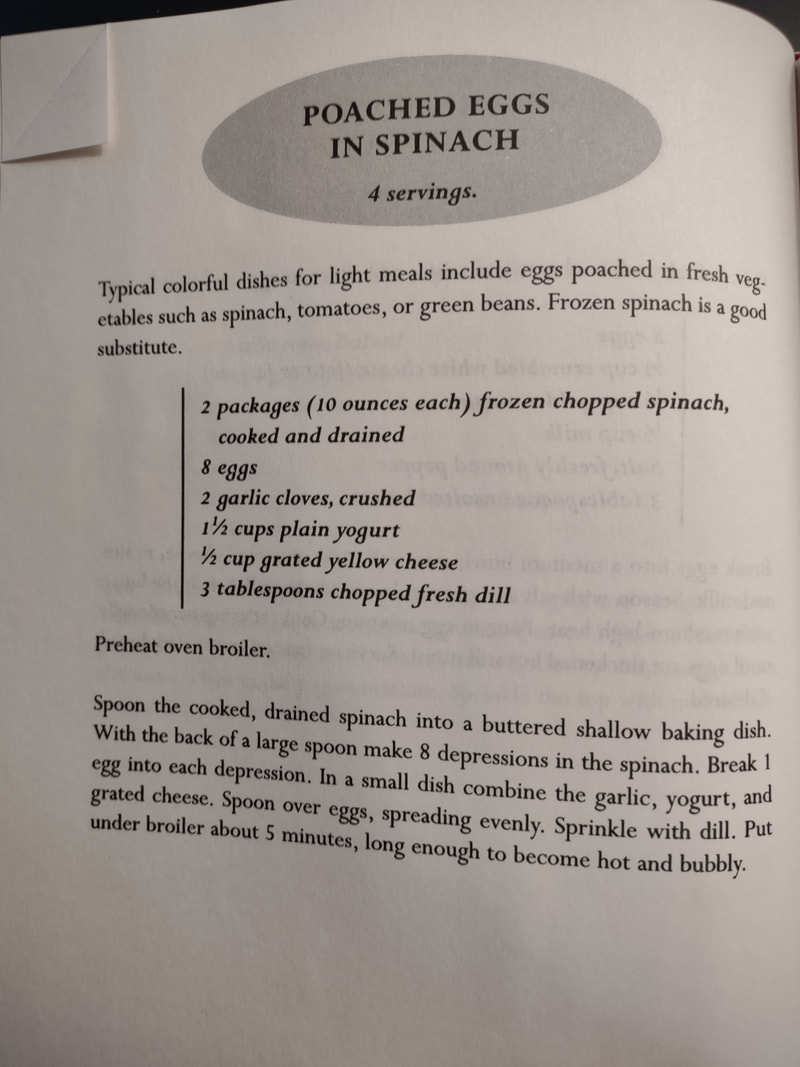

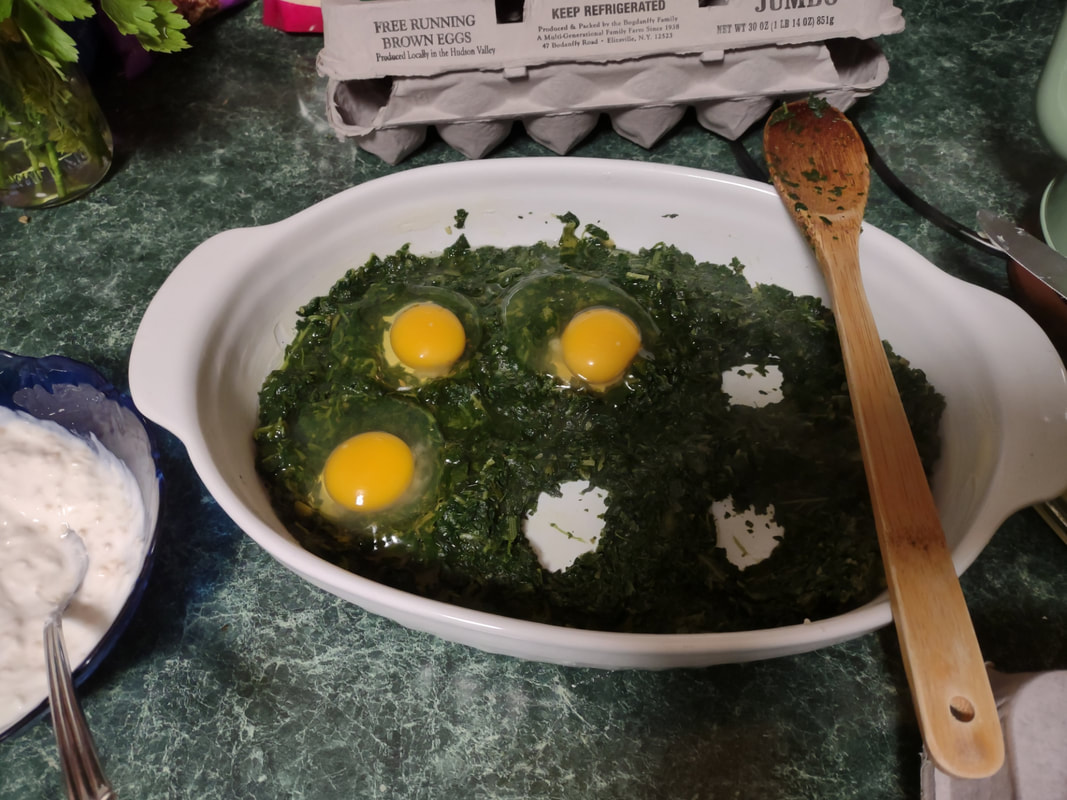

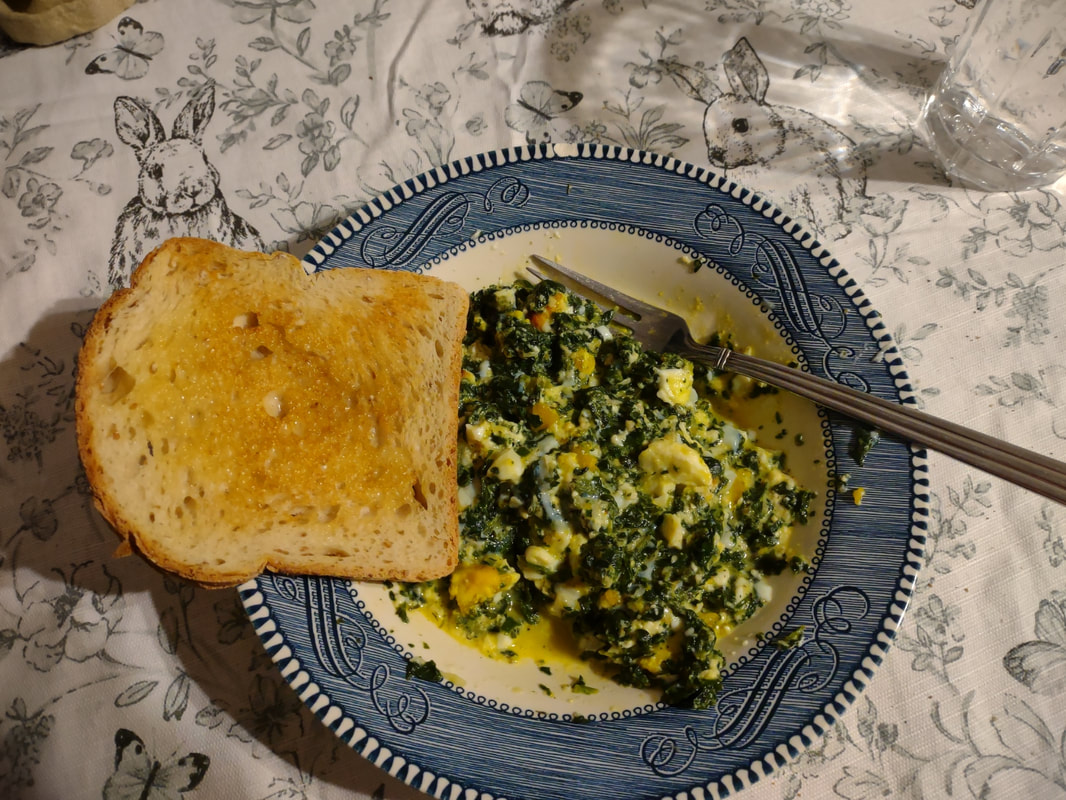

Note: This article contains Amazon Affiliate links. As I'm sure many of you have, I've been thinking a lot about Ukraine and Eastern Europe these days. Last week I launched a Substack specifically so I could give food history commentary on current events, and my first post was all about Ukraine. I've long had an interest in the cuisines of Eastern Europe and the states of the former Russian/Soviet empires. Their creative use of ordinary ingredients and emphasis on fresh fruits and vegetables is extremely appealing to a Midwesterner raised on meat and potatoes. The connection to the land, gardens, and older folks also reminds me a lot of visiting my great-grandmothers in rural North Dakota, who kept huge gardens, and dirt cellars full of preserved foods. I'm always on the lookout for new cookbooks in this vein, so when I saw the following, I snatched it up. The week before the Russian invasion of Ukraine - Cuisines of the Caucasus Mountains: Recipes, Drinks, and Lore from Armenia, Azerbaijan, Georgia, and Russia by Kay Shaw Nelson arrived at my door. First published in 2002, it's written by Nelson, an American who studied Russian language and literature and later became enamored of the food of Georgia (which I am also very interested in). She covers the whole of the Caucasus Mountains, and writes eloquently on each country and their regional differences in agriculture, wild foods, terrain, and foodways. I'm always interested in vegetarian dishes, and this cookbook has quite a few, in addition to some delicious-sounding meat dishes. The book is divided by a combination of meal and ingredient, including appetizers, soups, dairy dishes (where eggs are confusingly included), fish, meat/poultry/game, vegetables & salads, grains & legumes, breads/pastas/savory pastries, desserts & sweets, and beverages/drinks/wine. I have earmarked a number of dishes, including salads and egg-based dishes. After the success of Eggs en Cocotte last week, I thought we'd take a stab at another egg dish for a simple supper. Nelson doesn't assign this dish to a country or region, like she does the others, so I've ascribed it to the entire Caucasus Mountains region. Poached Eggs in Spinach with Garlic and YogurtNelson's original "Poached Eggs in Spinach" recipe is pretty straightforward, and as she remarks in the headnotes, tomatoes and green beans are an alternative vehicle for the poached eggs (similar to Middle Eastern shakshuka). However, her recipe leaves a bit to be desired. Because spinach is the main vehicle of this dish, if you don't season the cooked greens and the eggs well, it will be a flop. Here's my adaptation of her original recipe. 2 packages frozen spinach (10 ounces each), cooked and drained salt, pepper, and whatever other spices you like lemon juice 6 eggs 1 1/2 cups plain yogurt 2 garlic cloves, finely chopped 1/2 cup shredded mozzarella salt pepper dried dill butter for the baking dish Preheat your broiler. Season the spinach with salt, pepper, and lemon juice. Place in a well-buttered baking dish (not glass, which is not broiler safe) and make six indentations for the eggs. Mix the yogurt, garlic, and mozzarella. Crack the eggs into the indentations, then spread the yogurt evenly over the top (I skimped mine a little because I was using fewer eggs, and shouldn't have). Top the yogurt with more salt and pepper and dried dill. Broil for 10-15 minutes or until the yogurt is bubbly and browned and the egg whites are set. Two eggs per person was plenty, and the leftovers weren't bad, although the egg will obviously cook more once you reheat it. I ate mine all mixed up with some buttered cracked wheat toast (Heidelberg Bread Company in New York makes the BEST toast). This turned out pretty well, all things considered. Without the seasoning it would have been especially bland, so make sure you season your greens! A few things I would change - press more of the water out of the spinach and add more lemon juice, add chopped fresh dill and parsley to the spinach mix, or lemony fresh sorrel if I could find it. I think I would also add onion or more garlic to the spinach itself, instead of just the topping. I would also follow the instructions and use more yogurt for the topping - the places where the egg white wasn't covered it got a little tough in the oven. I think I would still stick with just six eggs, instead of eight, because it was a nice ratio of egg-to-spinach, so the spinach felt like a substantial part of the meal, instead of a garnish for the eggs. I might also try this again in a stovetop-safe vessel like a cast iron skillet, or pre-heat the spinach in the oven before adding the eggs. The bottoms of the eggs were still a little undercooked and the tops were a bit tough. That being said, this was a surprisingly satisfying dish, and anything that gets more dark leafy greens into the diet is always a good thing. I would definitely try this again, but with some changes to make it more flavorful. What do you think - would you try it? The Food Historian blog is supported by patrons on Patreon! Patrons help keep blog posts like this one free and available to the public. Join us for awesome members-only content like free digitized cookbooks from my personal collection, e-newsletter, and even snail mail from time to time! Don't like Patreon? Leave a tip! Tip Jar

$1.00 - $20.00

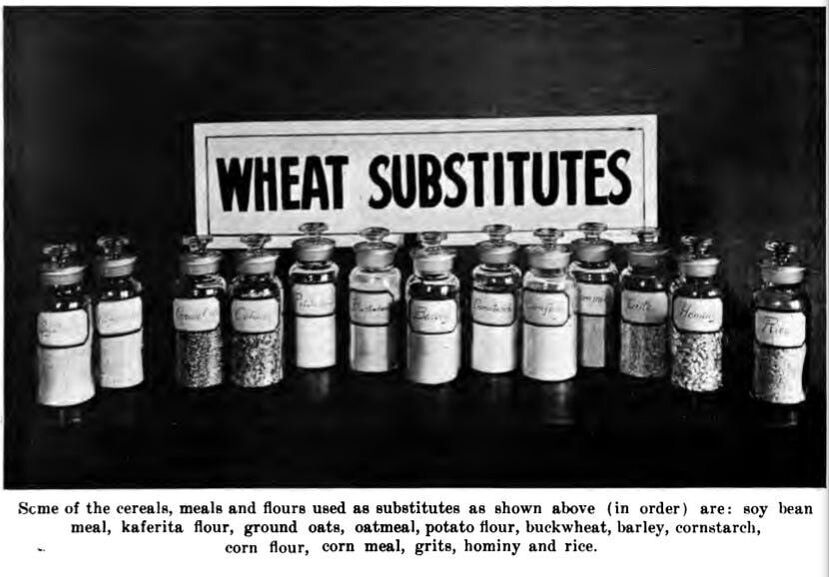

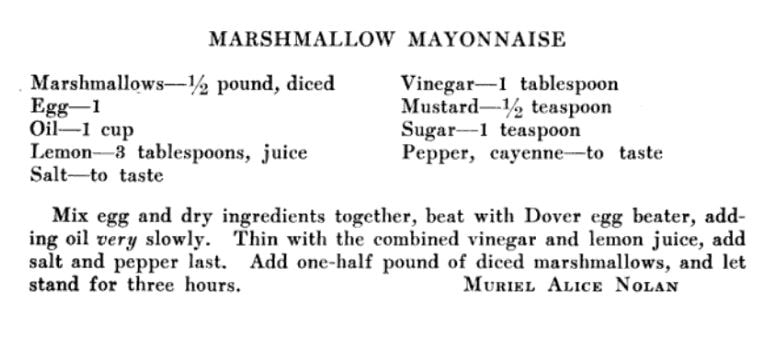

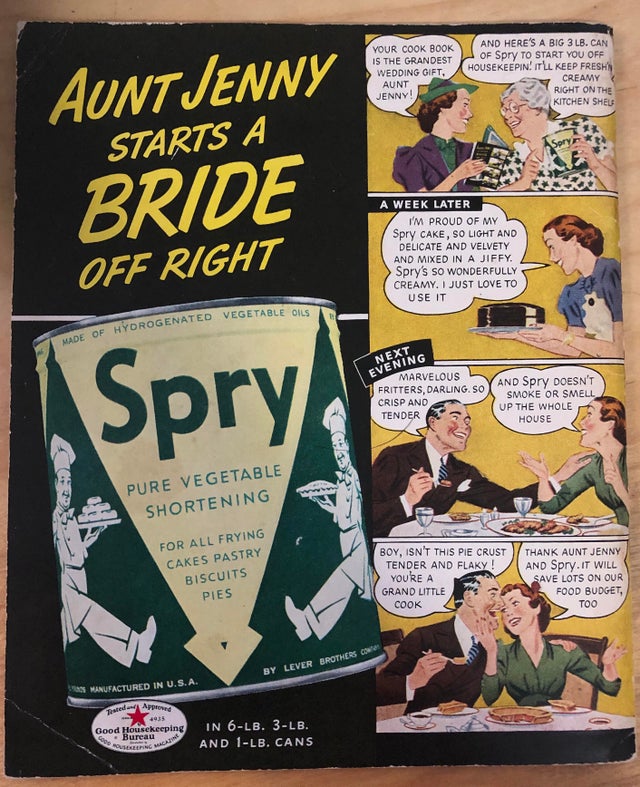

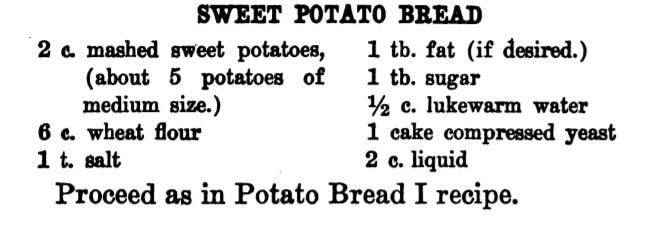

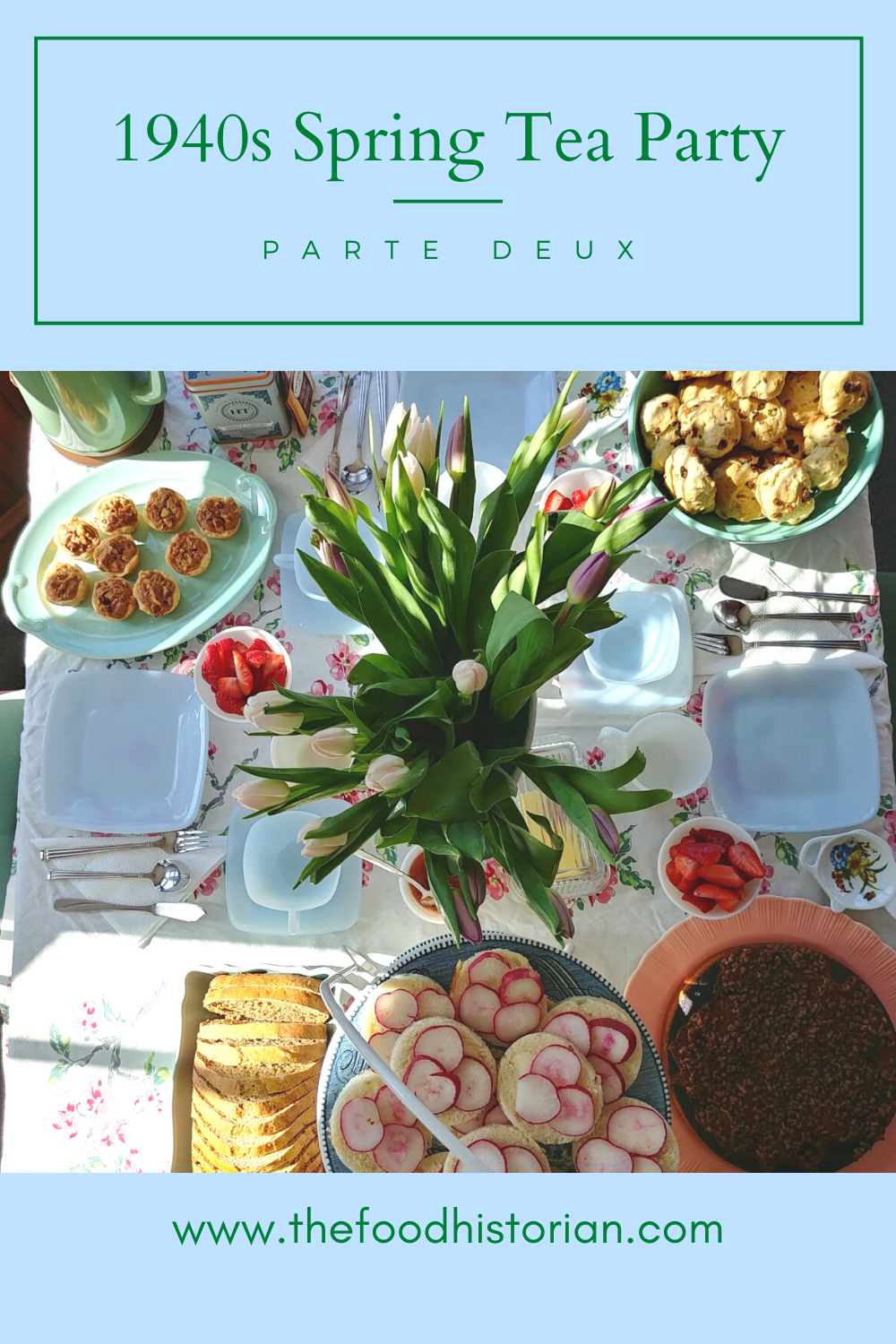

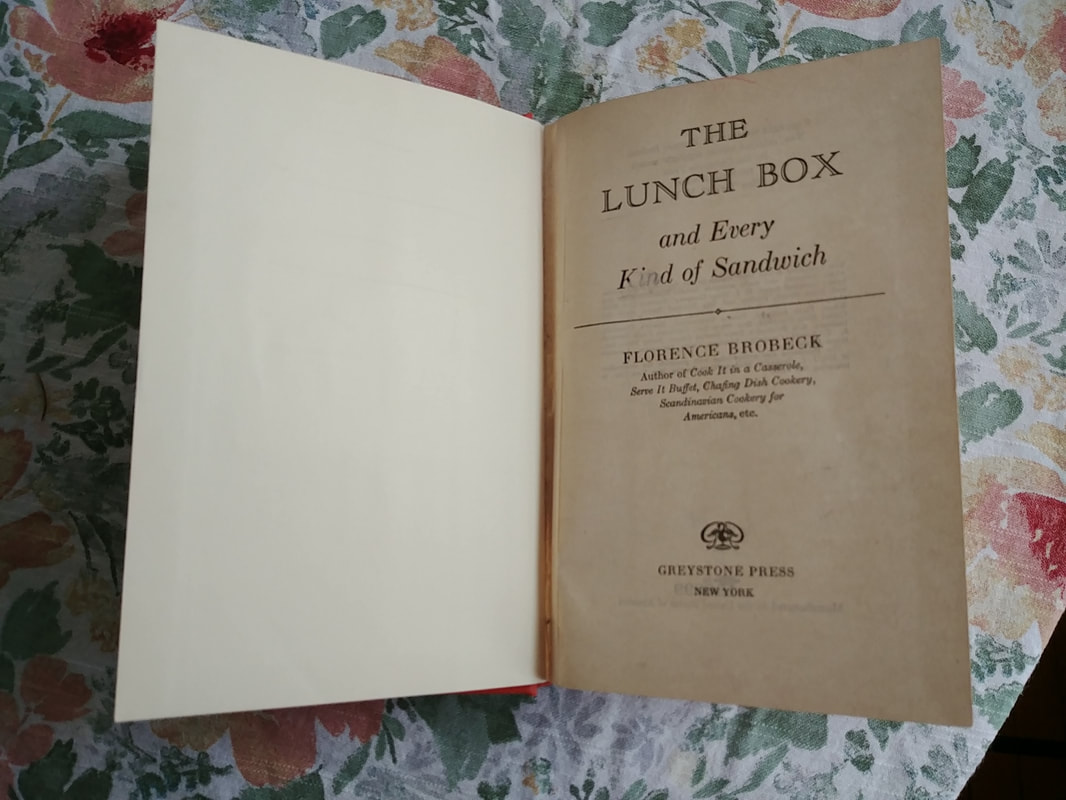

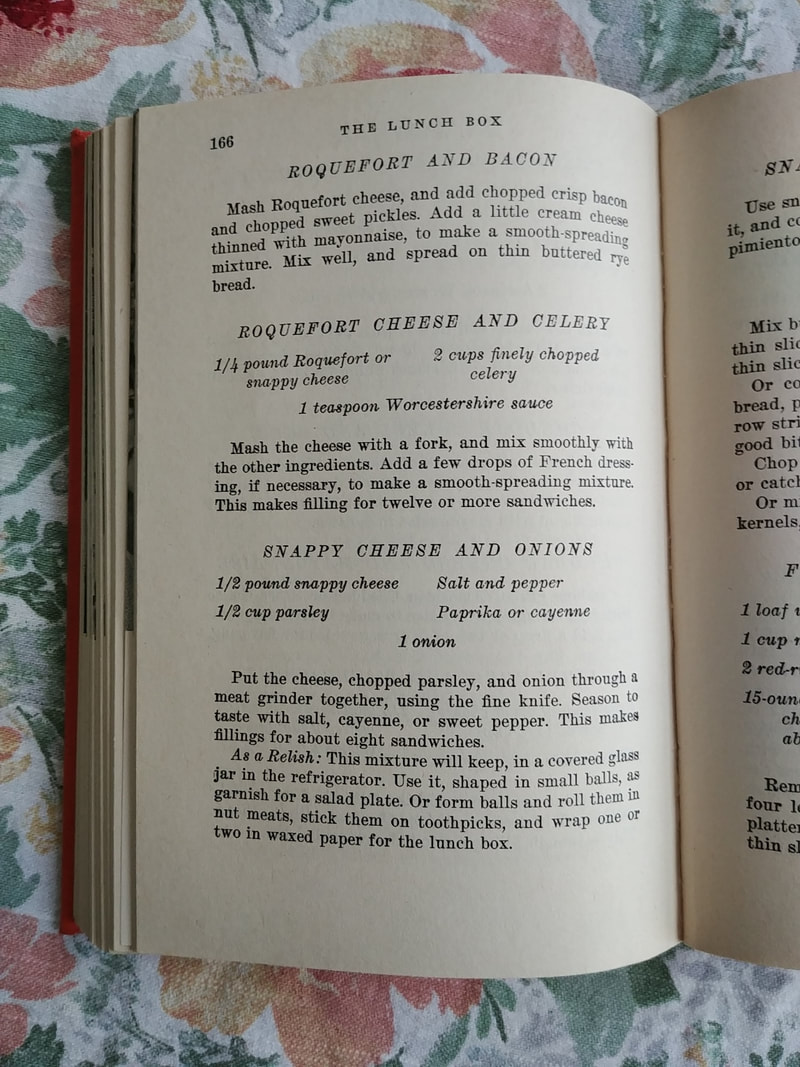

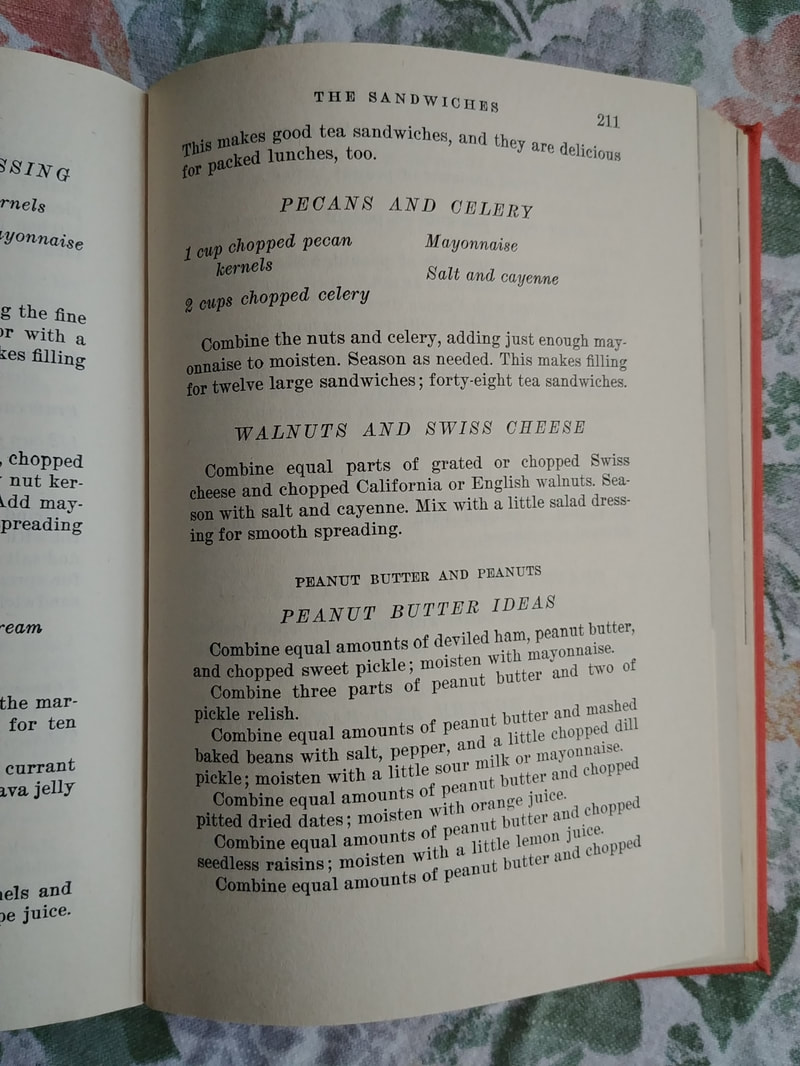

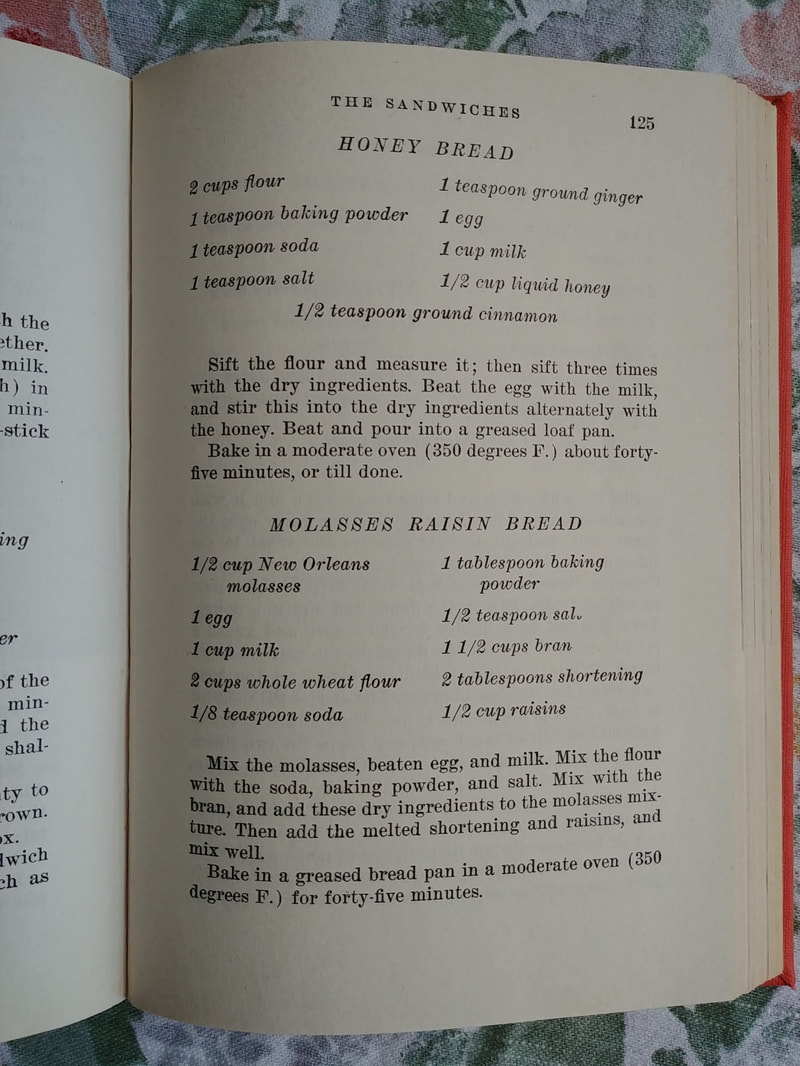

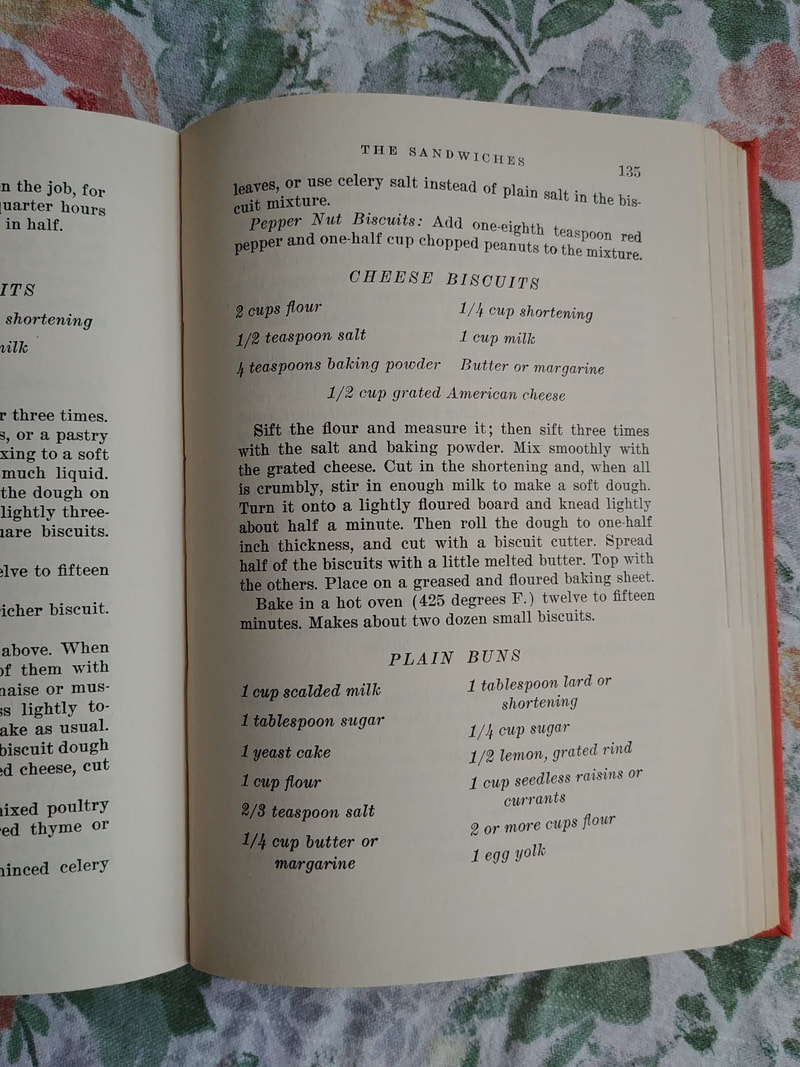

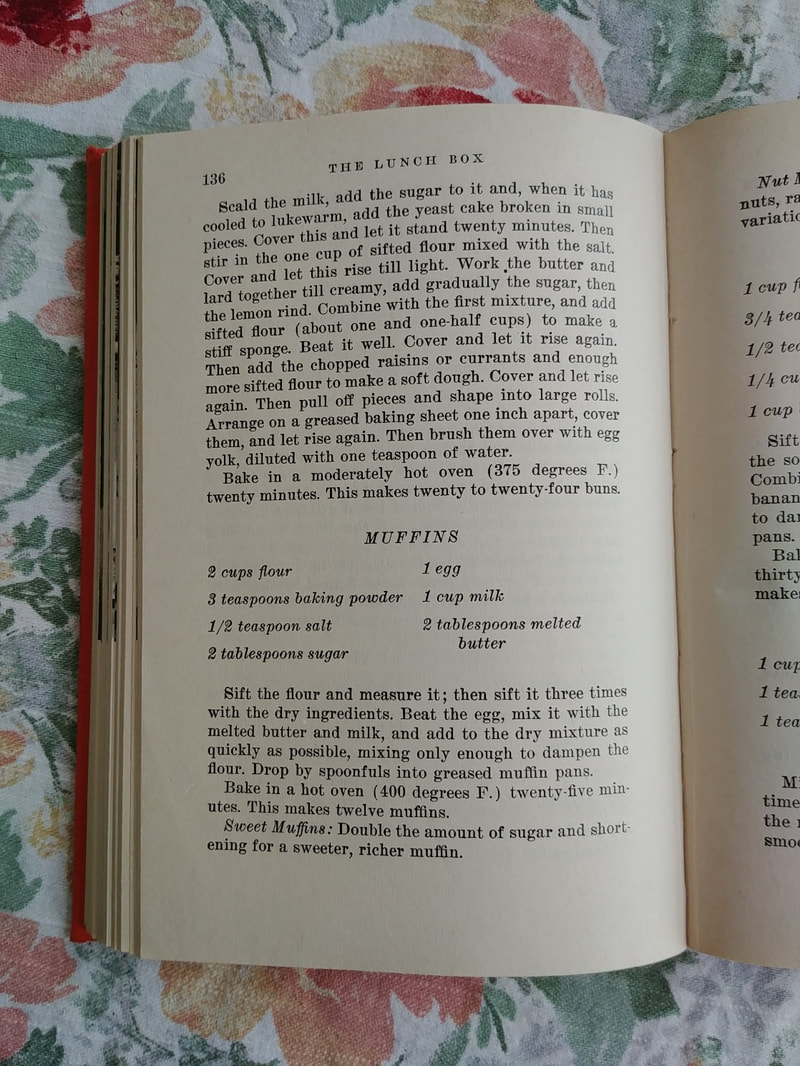

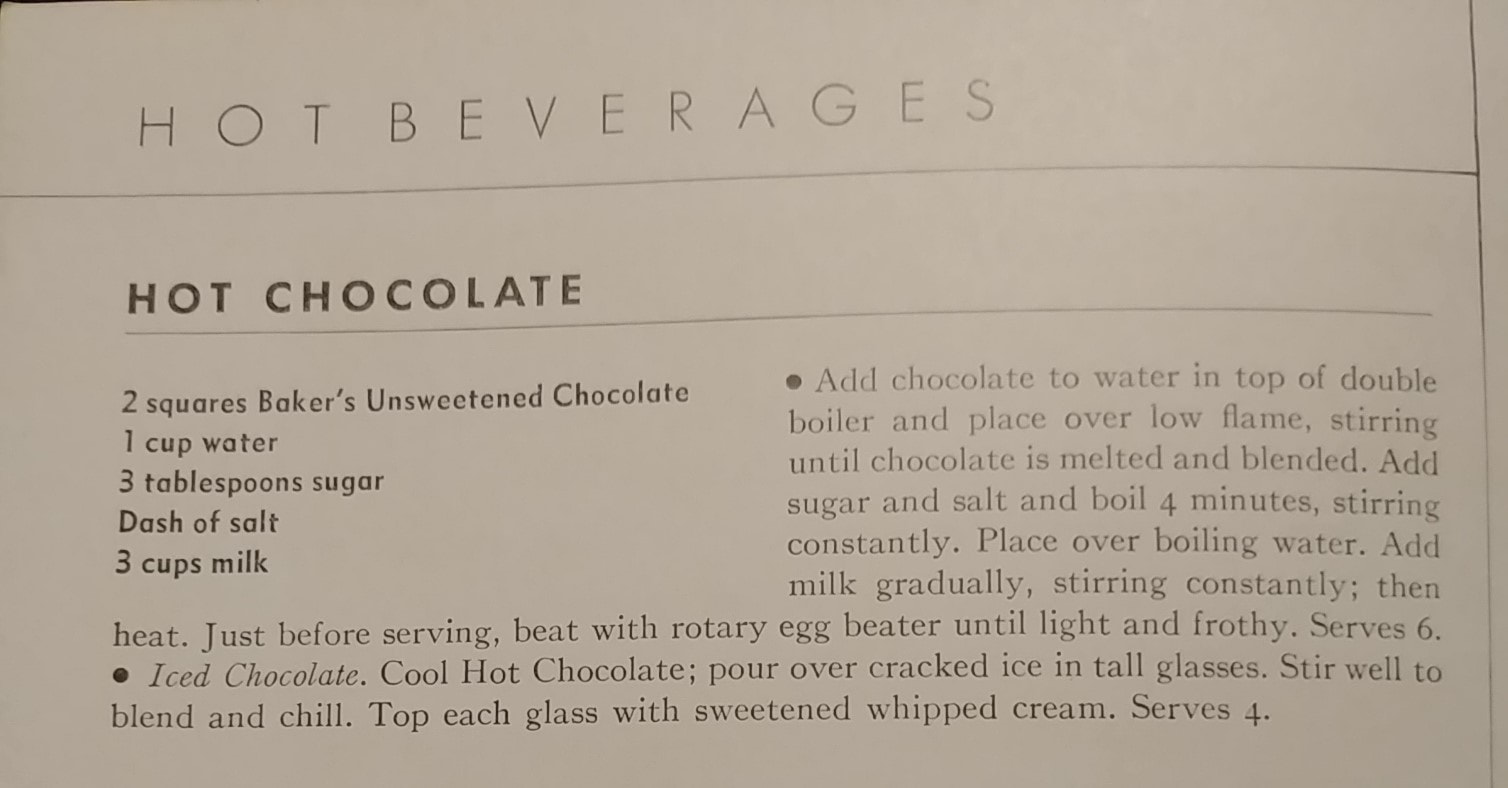

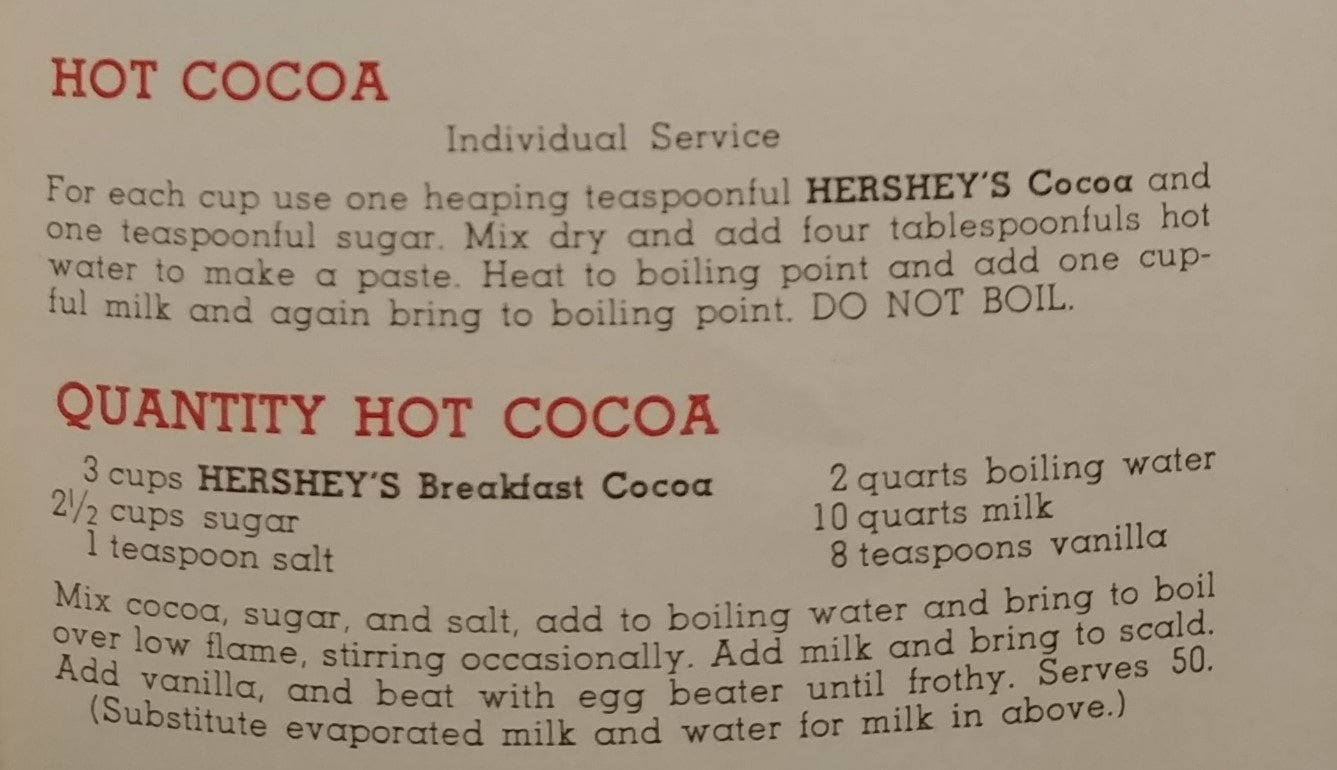

Like what you read, watch, or hear? Wanna help support The Food Historian, but don't want to commit to a monthly thing, or sign up for Patreon? Then you're in luck! You can leave a tip! This one-time (non-tax-deductible) donation helps keep The Food Historian going and pays for things like webhosting, Zoom, additions to the cookbook library, and helps compensate Sarah for her time and energy in helping everyone learn more about the history of food, agriculture, cooking, and more. Thank you! Well friends, I said I was contemplating a part two to last week's examination of 1950s food, and this meme kept popping up on my socials, so here we are again! This one isn't quite as inflammatory, and no fun illustration to catch your eye, but it makes a similar claim nonetheless. Here's the original text: The main thing I get from Dylan Hollis cooking old recipes is this: If you haven't seen any of Dylan Hollis' TikTok videos, I recommend them! He's hilarious. Not a food historian, but he cooks historic recipes and taste tests them. Some are horrific, but most are delicious - and while Dylan's reactions are 99% of the fun, his shock when things are actually tasty, while hilarious, does grate a little sometimes. Yes, people in the past really did know what they were doing! The meme claims that the food of the 1910s and the Great Depression were better than the 1950s, and were made with love, working with limited ingredients, whereas 1950s recipes were made to sell products during the McCarthy era. And while those ideas aren't necessarily wrong, they're definitely not the whole story. The time period of 1900 to 1950 is my favorite time period for cookbooks. They usually have decent instructions with things like measurements and oven temperatures, but are still from scratch. USUALLY being the key word there. Because starting in the 1870s, corporate food brands started publishing cookbooklets to sell their products. One of the earliest adopters of this sales tactic? Cottolene brand shortening. Not exactly lard, but pretty darn close! A lot of the corporate cookbooks and cookbooklets of the late 19th and early 20th century were primarily for ingredients. Different brands of flavorings and spices, baking powder, flour, shortening or lard, etc. were the main branded food products at the time. A lot of major food companies today started out as flour companies, including General Mills. So the cookbooks were largely normal scratch recipes that just recommended the cook or baker use the branded ingredients, but it was easy to substitute whatever you had on hand. And then, we started to get corporate food products like Campbell's canned soups, and Libby's canned corned beef, and powdered Knox gelatine and Jell-O, and other foods that were closer to finished foods already. You can only eat so much soup in a week. So how was Campbell's to get people to eat more of it? In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, we had more and more women graduating from food and nutrition schools and college programs. Domestic scientists and expert cooks and home economists happily filled the role of cookbook authors and test kitchen managers for food corporations. Which is how we got things like tomato soup spice cake (Dylan Hollis does a recipe from the 1950s, but it was actually invented in the 1920s!), cream of whatever soup casseroles, and marshmallow mayonnaise. While tomato soup spice cake is probably delicious (at least, Dylan Hollis thinks it is!), and cream of whatever soup is a lot easier than white sauce, I'm not sure about the marshmallow mayonnaise, but the cookbook says to serve it with fruit salad, so maybe it is? Who am I to judge? The point being, by the 1910s, there were plenty of marketing cookbooks and advertisements with recipes for processed foods for housewives to choose from. And while home economists were cranking out recipes that were sometimes smash hits and sometimes abject failures, there was a bit of a storm brewing in households around the country. Mainly, the "servant problem." For most of the 19th century, middle and upper-middle class families had at least one household servant (or enslaved person, prior to the Civil War) who did the bulk of the heaviest household labor. Middle class women and their daughters did household work too, but were generally spared things like scouring pots and scrubbing floors and hauling water and coal. But at the turn of the 20th century, we started to get pink collar jobs - being a shop girl or secretary or teacher or nurse was preferable for many women to the 24/6.5 schedules of being in service. Rural families usually had lots of children to help with agricultural labor, but in a family of 6 or 10, the older girls always helped care for the younger children and everyone did household chores. As families shrunk and household servants became harder to find and more expensive, more and more women had to do with less and less help at home. At the same time, education levels for women were rising. Girls stayed in school beyond the elementary level and attended high school and college in larger and larger numbers. Many parents also wanted better lives for their children than they had, and wanted to spare girls the drudgery of household labor. Upper and upper-middle class girls, in particular, had been raised in households with servants and mothers who spared them all but the basics of running a household. So when they married, all of a sudden girls with college educations had to figure out household budgets and weekly grocery shopping and cooking on their own, without many skills or resources to help them. Enter the ad man and the home economist. Swearing to save the clueless young bride from a lifetime of drudgery, while still pleasing her husband, all sorts of companies targeted young, inexperienced women just starting their households, but none perhaps as diligently as Spry, which manufactured first lard and later shortening (there's that lard reference again!). Aunt Jenny was the fictional grandmotherly character who knew just everything and would teach it all to her clueless niece. And of course, the secret was always a giant can of Spry. While Spry cookbooklets joined the legion of competitors, it was their cartoon-style print ads and extensive radio shows and advertisements that helped sway millions of American women to the Spry way of life. Is it any wonder that women who married in the 1930s and '40s raised children in the 1950s on corporate foods? Untrained, without the household help of their mothers and grandmothers, and with high expectations for home cleanliness and cooking three meals a day, 364 days a year would be enough to drive anyone into the arms of kindly home economists and fictional characters like Aunt Jenny, Mary Lee Taylor, Betty Crocker, and others. Recipes as advertisements for corporate foods did NOT start in the 1950s by any means. But the meme is somewhat correct in that scratch cooking was more prevalent in the Great Depression in particular, largely because at the time industrial foods were still more expensive than cooking from scratch, and because women who were adults in the 1930s were more likely to have been born into households that still taught them something about cooking and household management. And although the balance of population in the United States tipped from rural to urban in the 1920s, we still had a huge population of people primarily involved in agriculture, meaning families were larger (my mom's parents, born to farmers in the 1930s, came from families of 9 and 10 children, respectively), so women had more household help. Rural areas were also slower to adopt new fashions, including fashionable food, and often had less access to industrial goods of all sorts, including processed foods. Rural families were also much more likely to grow and preserve the bulk of their own food, well into the 1970s, than the rest of America. If you had land and free labor, it was certainly cheaper than buying commercially canned goods. If your grandmother grew up in a rural area during the Great Depression, like mine did, she probably learned how to cook from scratch. But by the 1950s, she was raising kids on her own, and maybe had a career of her own, or was supporting her husband's career, which meant less time to cook from scratch as she cared for her own children and a house with higher standards of cleanliness and fashion than her mother's with a lot less help. At the same time, in the 1950s, the general consensus was that industrial foods were the wave of the future - they were boons to help a busy housewife, not things to be scorned and rejected. And as incomes rose, it was much easier to purchase foods than doing your own home preserving. And while the Great Depression did result in a lot of creative cooks (banana bread, for instance), I find the mention in the original meme of Saltines ironic. Although Saltines and cracker companies like Ritz didn't invent cracker-based mock apple pie (that dates back to the 1850s, believe it or not), they sure hopped right on that bandwagon and used it as a selling point. Necessity is the mother of invention. But rising incomes are the mother of convenience. And while McCarthyism probably did prevent the spread of some delicious and interesting foodways through its xenophobia and rigid conformity, the road to corporate convenience foods was a long one. They didn't appear overnight once the calendar ticked over from 1949 to 1950. Indeed, scratch cooking and baking continued well into the 1950s, and many of the foods we associate with the 1950s (Cool Whip, anyone?) weren't actually invented until the 1960s. For instance, the Pillsbury Bake-Off baking contest didn't start until 1949, and while modern incarnations of the contest are usually dominated by mutated versions of whatever convenience food Pillsbury has cooked up (usually crescent rolls or cinnamon rolls or canned biscuits), the original contest was meant to promote Pillsbury flour, so the recipes are all from scratch. And looking at my food historian library shelves, the 1950s section has plenty of community cookbooks filled with can-of-this, box-of-that recipes, and advertising cookbooklets galore, but there are also cookbooks like The Magic in Herbs (first printed in 1941 but on its seventh printing by my 1950 copy) and The Peasant Cookbook (1955, and my copy was from the library of the Ladies' Home Journal!), and Whole Grain Cookery (1951) and those community cookbooks always had scratch recipes in them, too. And my 1930s section? I have more corporate cookbooklets from the 1930s than any other era! Like most of history, individual decades might be changed and marked by big events, but history is complicated. In the Progressive Era we had brutal strikes and food riots, but we also had Gibson Girls and Vanderbilts and Rockefellers. During the Great Depression we had the Dust Bowl and migrant workers, but we also had the glamour of Hollywood. And yes, in the 1950s we had McCarthyism (and sexism and racism) and processed food, but we also had folks like James Beard and Julia Child and plenty of scratch cooking. So let's stop stereotyping decades and accept them for what they are - complicated, messy, and fascinating time periods with both good food and bad. And the next time you see a corporate food cookbook from the 1950s - give it a gander. You might be surprised by what you find inside. There are good recipes in just about every cookbook, if you take the time to look. The Food Historian blog is supported by patrons on Patreon! Patrons help keep blog posts like this one free and available to the public. Join us for awesome members-only content like free digitized cookbooks from my personal collection, e-newsletter, and even snail mail from time to time! Don't like Patreon? Leave a tip!  "Wheat Substitutes" as illustrated in "Liberty Recipes" (1918). Caption: "Some of the cereals, meals and flours used as substitutes as shown above (in order) are: soy bean meal, kaferita flour, ground oats, oatmeal, potato flour, buckwheat, barley, cornstarch, corn flour, corn meal, grits, hominy, and rice." Last time for World War Wednesday, we discussed how important it was during the First World War to save wheat and reduce bread consumption. During the war a number of cookbooks were published to help Americans reduce their consumption of wheat, meat, butter, and sugar and how to go without or reduce the use of scarce or expensive ingredients like eggs. When it came to bread, there were very few recipes that used no wheat flour at all, but instead most recipes used alternative grains like barley, rye, corn, and oatmeal or other ingredients like mashed potatoes or cooked rice to reduce the overall ratio of wheat flour used. Liberty Recipes was written by Amelia Doddridge, who the title page lists as "Formerly, Instructor of Cooking, Manual Training High School, Indianapolis, Indiana; and Emergency City Home Demonstration Agent, Wilmington, Delaware. Now, Head of Home Economics Department, Wooster College, Wooster, Ohio." The book was published by Stewart & Kidd Company in Cincinnati, Ohio in 1918. I wasn't able to find much more on Amelia herself. I found a dissertation that notes that several classes in food and household management at Wooster College were taught by Amelia, who was then Acting Dean of Women. But those classes were apparently only offered temporarily during the war, "These particular classes were offered only between 1918-1919 during the "confused period of war, fuel shortages, S.A.T.C., Spanish flu, and demobilization." Which seems to indicate that Amelia herself may not have survived as an instructor after the war. A reference from 1922 places an Amelia Dodderidge in Montevallo, Alabama as head of the home economics department "at Montevallo," which possibly meant the college located there. I found a reference to an Amelia Doddridge teaching high school home economics in Ohio in 1924. And another to an Amelia Dodderidge working at a Farm Bureau in Pennsylvania and/or as a county home economics representative, and/or as the Home Economics Extension representative from the state college, all in Pennsylvania, all in 1926. In 1929 there's a Miss Amelia Dodderidge in Modesto, California, acting as an "assistant home department agent." By the 1950s she appears to be living, retired, in Franklin, Indiana and throughout the late 1950s and 1960s there are numerous articles in the Franklin Star authored by Amelia Dodderidge. A 1962 article indicates she was working for the Methodist Home (likely a home for the elderly) in Franklin, IN and, indeed, most of the articles she published in the Franklin Star were called "The Home Window," apparently reporting on the activities and events of the Methodist Home. The trail runs cold at the very end of 1963. The last reference to Amelia is published on December, 31. It's unclear whether the newspaper simply did not run her column again or if the newspaper itself ceased publication or if it simply wasn't digitized past 1963. Although it's tough to prover all these Amelia Dodderidges were the same person, it is very likely. Amelia apparently continued her home economics work throughout her life, even after "retirement." But back to Liberty Recipes. The cookbook is a fascinating one, and I particularly love some of the slogans listed in the frontspiece; my two favorites are "Place meat and buns behind the guns" and "Husband your stuff; don't stuff your husband." Also interesting are the references in the foreword to the cookbook itself being much more convenient for reference by housewives rather than taking "too much trouble to hunt in a pile of leaflets for the recipes she wishes at the particular time she needs it" - a reference to the numerous bulletins and cookbooklets being published by the USDA and other government agencies. In addition, the foreword claims that although the recipes listed are designed for the "present emergency," "they should be usable and still practical even after the war clouds pass and Freedom is ours." There are numerous bread recipes in the cookbook - both yeast and quick breads. In addition, the cookbook focuses on meatless and meat-saving recipes, a few salads, and numerous sugarless, low-sugar, and wheat- and fat-saving dessert recipes. This recipe for Sweet Potato Bread seemed quite modern, and a fun recipe to share in the lead-up to Thanksgiving. Although I have not had time in a while to bake yeast bread, I thought I would share it anyway. Maybe I can take a stab over the holiday. World War I Sweet Potato Bread (1918)The original recipe makes references to other recipes, so I've combined the instructions for your convenience. A cake of yeast is about the same as dried yeast packets that are sold today. Although you can try it with RediRise or similar fast-acting yeast, I recommend plain ol' active dry yeast. 2 cups mashed sweet potatoes (about 5 potatoes of medium size.) 6 cups wheat flour 1 teaspoon salt 1 tablespoon fat (if desired.) 1 tablespoon sugar 1/2 cup lukewarm water 1 cake compressed yeast (or 1 envelope active dry yeast) 2 cups liquid Use the potato water for the liquid. Pour it gradually over the hot mashed potatoes. When lukewarm add the softened yeast, salt, sugar, and fat. Stir in the rest of the flour gradually. When the dough becomes too stiff to stir, work in the remainder of the flour by kneading with the hands. It may take a little more flour or a little less depending upon the kind of flour used. The dough should be of such a consistency that it will not stick to the hands or to the bowl. Knead 10 or 15 minutes until the dough is smooth and elastic. Place in a bowl, cover, and keep it in q warm temperature (75 to 85 F). When risen twice its bulk, cut down and knead again. Then shape into loaves, place in greased pans, and set in a warm place. When light and doubled in bulk it is ready to bake. To prevent a crust from forming over the top of the loaf while rising, rub the surface with a little melted fat. Watch the rising and put into the oven at the proper time. If risen too long, it will make a loaf full of holes; if not risen enough, it will make a heavy bread. Bake 45 minutes to 1 hour in a moderately hot oven (375 to 400 F). If oven is too hot, the crust will brown before the heat has reached the center of the loaf and will prevent further rising. The loaf should raise well during the first 15 minutes of baking; then it should begin to brown, and continue browning for the next 15 or 20 minutes. The last 15 to 30 minutes, it should finish baking and the heat may be reduced. When done, the bread will not cling to the sides of the pan. If a tender crust is desired, brush the bread over with a little melted fat as soon as it is taken from the oven. If you end up making this recipe, let us know in the comments how it turned out! There are lots of other interesting recipes to be had in Liberty Recipes, including a potato biscuit pie crust recipe, buckwheat spice cake, and cornmeal gingerbread, to name a few! Are there any recipes in there that you want to try? The Food Historian blog is supported by patrons on Patreon! Patrons help keep blog posts like this one free and available to the public. Join us for awesome members-only content like free digitized cookbooks from my personal collection, e-newsletter, and even snail mail from time to time! Don't like Patreon? Join with an annual membership below, or just leave a tip! Spring has sprung, with daffodils nodding in the frosty air and trees starting to bud out. So it seemed apt to celebrate with another tea party! Once again, our tiny tea party with just one friend featured all-vegetarian recipes, since said friend is a vegetarian. And also because chicken salad, while delicious, seems lazy when you're looking for something new and interesting to try. This one featured recipes from a new cookbook acquisition, The Lunch Box and Every Kind of Sandwich by Florence Brobeck. My edition was published in 1949, although I believe the original was published sometime in the 1930s. It's also a bright orange library binding without the original dust jacket. So no pretty cover to show off this time! Unlike last time, my ambitious list didn't go QUITE as planned. Adapting historic recipes can be like that. 1940s Spring Tea Party MenuOpen-Faced Radish and Butter Sandwiches on White Open-Faced Cucumber and Cream Cheese Sandwiches on Rye Blue Cheese, Pecan, and Celery Sandwiches on Whole Grain 1940s Whole Wheat Honey Quick Loaf 1940s "Plain Buns" with Butter and Jam Fresh Sugared Strawberries Strawberry Lazy Daisy Cake Walnut Tassies Hot Cocoa Tea with Cream and Sugar The SandwichesRadish and butter sandwiches just scream spring to me, and they're very easy to put together. To make things extra fancy, cut sliced bakery bread (not the squishy kind from the bread aisle - hit the bakery and get peasant, sourdough, brioche, or in a pinch, French or Italian bread) with a cookie or biscuit cutter into rounds. Spread with soft butter, top with thinly sliced radishes, and a sprinkling of salt (I used pink Himalayan). The salt is what makes the radishes look wet, but adds a nice flavor. Open-faced cucumber sandwiches are equally easy. Make a cream cheese spread with softened cream cheese (15 seconds in the microwave does the trick), and thinly sliced scallions and dried dill. You can use jarred garlic or minced sweet onion instead of scallions. Spread it on any kind of rye bread. Top with English (a.k.a. seedless - even though they're not - or burpless) cucumbers. If you're hungry, top with another slice of bread spread with the cream cheese mixture, otherwise serve open-faced (which is prettier and more Scandinavian). If you're going really fancy, use fresh dill in the cream cheese and top each sandwich with a sprig of fresh dill. The little square sandwiches were a mashup of two recipes from the The Lunch Box - "Roquefort Cheese and Celery" and "Pecan and Celery" fillings. I decided to mash them up - literally - into one, slightly more interesting filling. I mixed a quarter pound of very soft blue cheese with about a cup each of diced pecans and finely minced celery, with a splash of Worcestershire sauce. It was a curious mixture. Next time I would probably add cream cheese to temper the blue cheese a little, and maybe add some scallions and/or smoked paprika. But otherwise it was quite nice on squares of thinly sliced whole grain bakery bread. Half the fun of tea sandwiches is the fun and dainty shapes you create. I always find it easier to slice the bread first, and then fill, but some people do it the other way around. Whole Wheat Honey Quick LoafWhen one encounters a recipe entitled "Honey Bread," one expects it to taste of, well, honey. Instead, the spicing of this little quick bread leaves the impression of gingerbread more than honey. Curiously, the recipe also contains no fat. I was skeptical, but aside from an accidental overbaking (which I think dried it out), it turned out fairly decently, if scarcely tasting of honey. I followed this recipe pretty much to the letter. It makes a tall loaf with a springy crumb - not at all the crumbly, moist, cake-like texture we come to associate with most quick breads today. Much more like true bread texture than cake. Here's the original recipe: 2 cups flour (I used white whole wheat) 1 teaspoon baking powder 1 teaspoon soda 1 teaspoon salt 1 teaspoon ground ginger 1/2 teaspoon ground cinnamon 1 egg 1 cup milk 1/2 cup liquid honey Sift the flour and measure it; then sift three times with the dry ingredients (or if you're lazy, just whisk everything together). Beat the egg with the milk, and stir this into the dry ingredients alternately with the honey. Beat and pour into a greased loaf pan. Bake in a moderate oven (350 degrees F.) about forty-five minutes or until done. Tip out of the pan and cool on a rack. Serve with salted butter, honey butter, and/or jam. 1940s "Plain Buns"This recipe is deceptive. The title, "Plain Buns" is not accurate - flavored with lemon zest and currants (I used golden raisins), the flavor was surprisingly strong and delicious. Designed to be used with cake yeast, all I had was rapid rise yeast, so I think they got a little overproofed. I'm going to try making them with active dry yeast again, so I won't comment too much on what I did, and just give you the original recipe: 1 cup scalded milk 1 tablespoon sugar 1 yeast cake 1 cup flour 2/3 teaspoon salt 1/4 cup butter or margarine 1 tablespoon lard or shortening 1/4 cup sugar 1/2 lemon, grated rind 1 cup seedless raisins or currants (I used golden raisins) 2 or more cups flour 1 egg yolk Scald the milk, add the sugar to it and, when it has cooled to lukewarm, add the yeast cake broken into small pieces. Cover this and let it stand twenty minutes. Then stir in one cup of sifted flour mixed with the salt. Cover and let this rise until light. Work the butter and lard together until creamy, add gradually the sugar, then the lemon rind. Combine with the first mixture, add the sifted flour (about one and one-half cups) to make a stiff sponge. Beat it well. Cover and let it rise again. Then add chopped raisins or currants and enough more sifted flour to make a soft dough. Cover and let rise again. Then pull off pieces and shape into large rolls. Arrange on a greased baking sheet one inch apart, cover them, and let rise again. Then brush them over with egg yolk, diluted with one teaspoon of water. Bake in a moderately hot oven (375 degrees F.) twenty minutes. This makes twenty to twenty-four buns. Obviously I didn't let rapid rise yeast go through fours separate rises! But I think it still overproofed a bit. I also forgot the egg wash! Which meant the buns looked a bit more like rocks. But they sure tasted good, and that's what mattered. If you enjoy the citrusy flavor of hot crossed buns, you'll love these. Strawberry Lazy Daisy Cake & Walnut TassiesI've made Strawberry Lazy Daisy Cake before, but this time I was somehow out of coconut, so I used chopped pecans for the topping as chopped nuts are the other traditional topping ingredient. Not QUITE as good as the coconut, but still yummy. Sadly for you, I did not make the walnut tassies (my friend did), and thus cannot share the recipe. However, she, like I did, had to make some substitutions! For Walnut Tassies are supposed to be Pecan Tassies, but my friend was out of pecans, so walnuts it was. The original recipe is supposed to be like tiny pecan pies, but tiny walnut pies were equally good. One of the primary joys of tea parties, of course, is in the dishes. I've got my vintage Fire King Azurite Charm teacups and saucers, with newly acquired luncheon plates, some milk glass compotes with sugared strawberries in them, milk glass D ring mugs for cocoa, and assortment of vintage servingware in springy shades, on a vintage floral tablecloth. With tulips in the middle, of course. If you missed the last spring tea party, you can check it out here, with a promise of more to come! Have you had a tea party recently? What favorite food did you feature? Tell us in the comments! The Food Historian blog is supported by patrons on Patreon! Patrons help keep blog posts like this one free and available to the public. Join us for awesome members-only content like free digitized cookbooks from my personal collection, e-newsletter, and even snail mail from time to time!

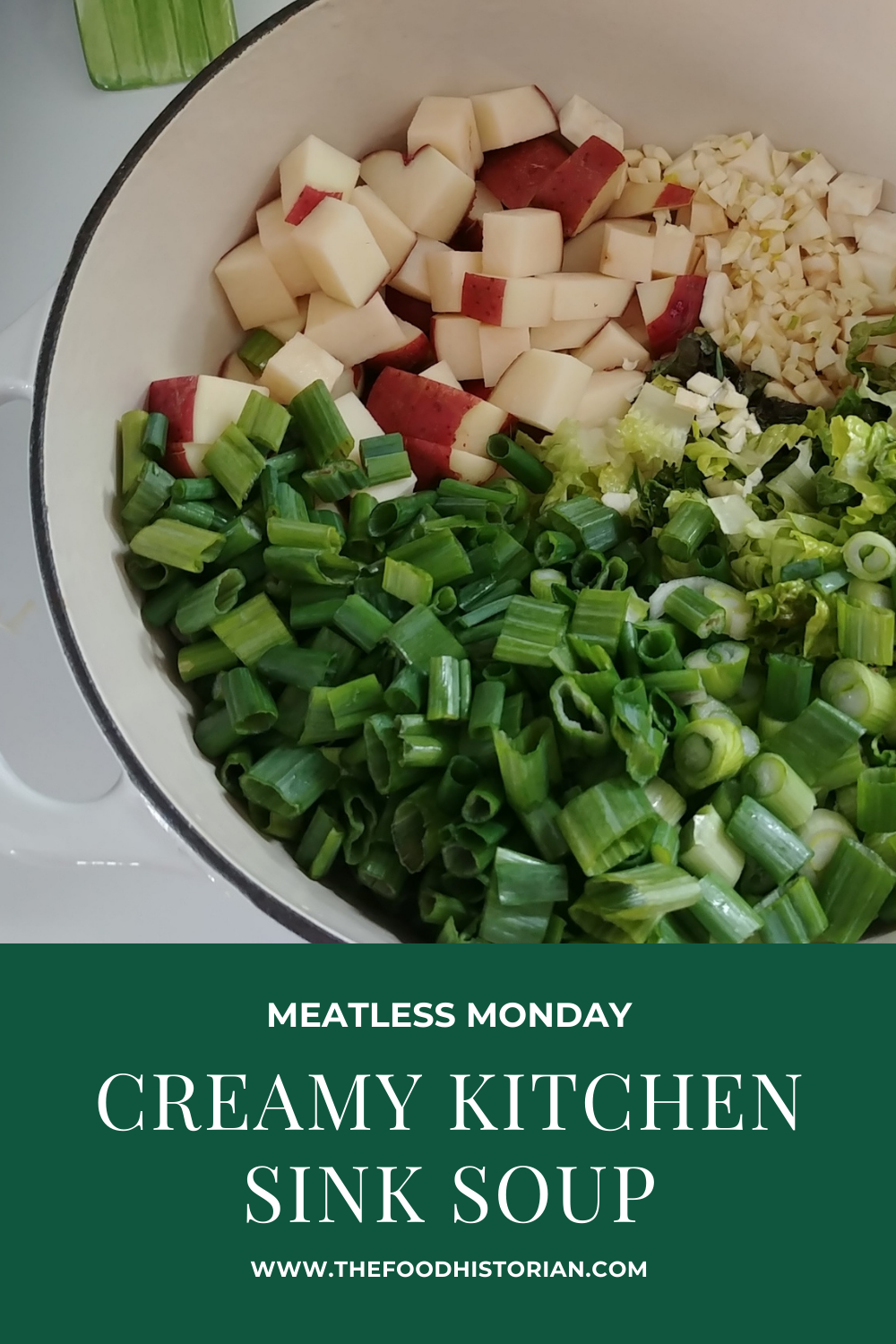

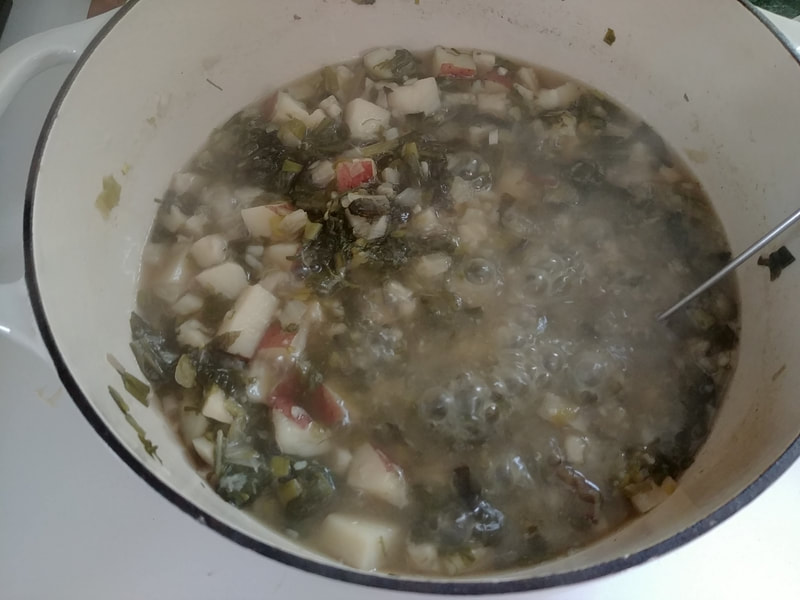

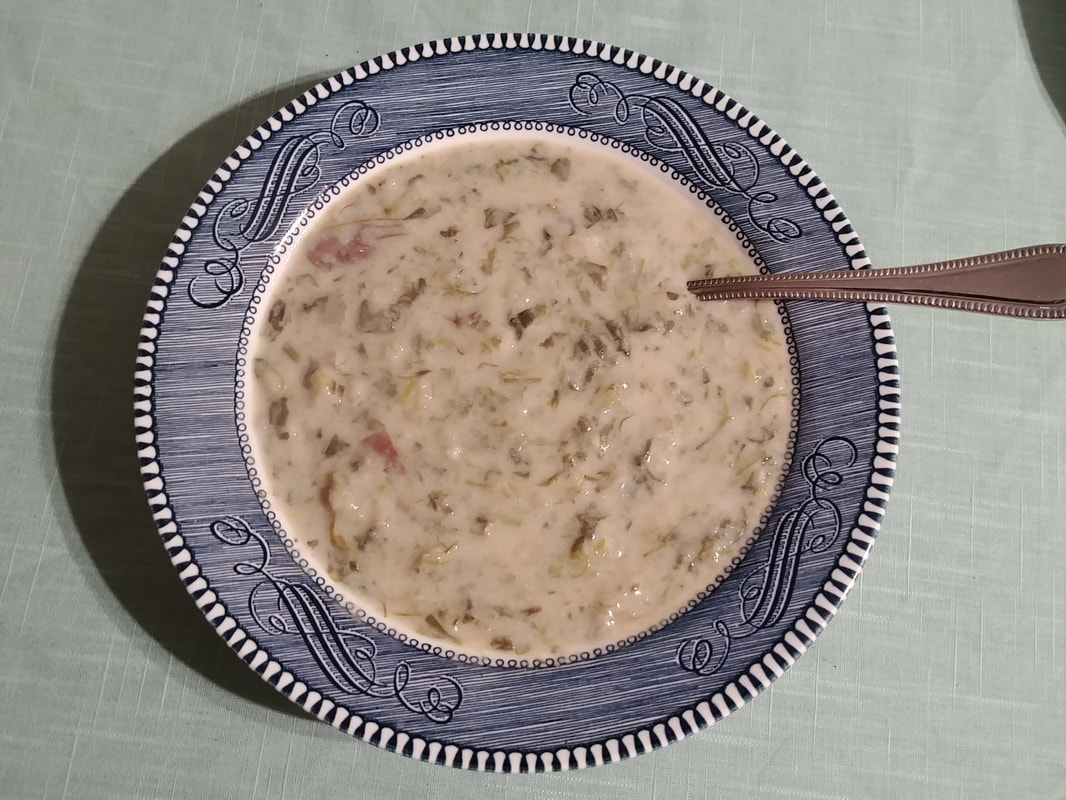

It's been cold and snowy lately here in the northeast, and sometimes you just have to have soup. But going to the grocery store in a snowstorm is ill-advised. This recipe lets you use up all kinds of bits and ends that might be languishing in your refrigerator.

This particular recipe is my own creation, based on what was in my kitchen, but is entirely inspired by history. Several parts of history, in fact. The first is reducing food waste. Historical peoples did not throw out potatoes just because they were starting to sprout, or lettuce because it was a bit wilted, and neither should you. Putting lettuce in soup is also extraordinarily historic, and a practice that should be revived. Another is that this recipe is based on one of my favorites, "Green Onion Soup," from Rae Katherine Eighmey's Hearts & Homes: How Creative Cooks Fed the Soul and Spirit of America's Heartland, 1895-1939 (2002). Eighmey read hundreds of agricultural magazines and gleaned recipes and wisdom from the farm home sections. Found in the December 26, 1924 issue of Wallace's Farmer, Green Onion Soup is a unique recipe. A combination of simply green onions and potatoes, the soup is cooked in a small amount of water, and then partially mashed right in the pot without draining. Cream and milk are added to thin the soup and add richness. The soup is comforting and nourishing and retains all of the vitamins and minerals that might otherwise be lost by draining away the cooking water. Which brings me to the final inspiration - vitamin retention in the style of recipes from World War II. By cooking the vegetables in the water that becomes the broth, you lose far fewer nutrients and flavor. Plus, other aspects of the soup are also quite appropriate to WWII - it's meatless, in line with rationing, and makes good use of milk, a favorite 1940s ingredient. Creamy Kitchen Sink Soup Recipe

I had a number of foods that needed using up that made their way into this soup: a few red potatoes, a head of wilted red lettuce, the fresh bits of baby spinach out of a box that was on the verge of getting slimy, a whole celery root starting to go a bit soft, some garlic starting to go green in the middle, and the tail end of a gallon of milk. The only fresh addition was two bunches of green onions. You could modify it pretty much however you want - any kind of greens, any kind of onion, any kind of root vegetable.

4 red potatoes 2 bunches green onions (scallions) 1 celery root 3 cloves garlic 1 head red lettuce 1-2 cups baby spinach water salt pepper 1/2 cup half and half 1 cup buttermilk whole milk Scrub and dice the potatoes, cutting away any eyes or bad parts, but leave the skin on. Slice the green onions, white and green parts. Cut away the knobbly skin from the celery root, then cut into small dice. Mince the garlic, wash and chop the whole head of lettuce. Add it all, with the spinach to a large stock pot and add water not quite to cover. Add at least 1 teaspoon salt (I used wild garlic flavored crystal salt languishing in a drawer) and bring to a boil. Reduce heat and simmer hard until all vegetables are very tender and potatoes fall apart when pierced with a fork. Do not drain. Using a potato masher or sauce whisk, mash vegetables in the pot until blended with the water, leaving some chunks. Add a the half and half and buttermilk (or you could use part heavy cream, or leave out the buttermilk, or just use milk) then add milk to thin out the soup and to taste. Taste for salt and add more if necessary, along with pepper and whatever other herbs and spices you like. Serve nice and hot with buttered bread or toast. The buttermilk does add a nice, distinctive tang. If you don't have any, add a dollop of sour cream, or some plain yogurt, or a splash of lemon juice. You could make this vegan with plant-based milk and butter. For a different flavor, add whatever fresh herbs you have lying around - dill, parsley, basil, and cilantro would all be good here. Add vegetable broth and some lemon juice instead of milk for a bright, brothy soup instead of something creamy. Use sweet potatoes or squash and tomato broth with the greens. The possibilities are really endless.

If you'd like more interesting recipes, you can purchase Eighmey's book from Bookshop or Amazon - either way, if you do, your purchase will support The Food Historian!

The Food Historian blog is supported by patrons on Patreon! Patrons help keep blog posts like this one free and available to the public. Join us for awesome members-only content like free digitized cookbooks from my personal collection, e-newsletter, and even snail mail from time to time!

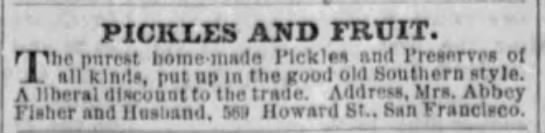

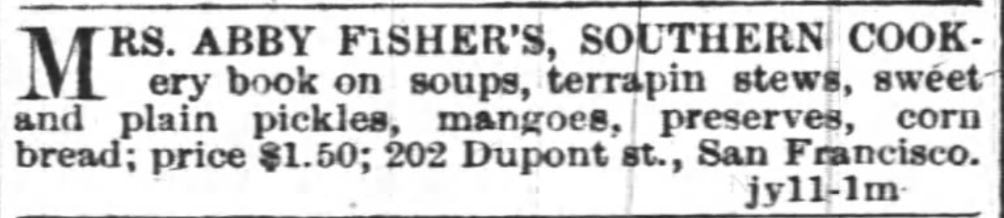

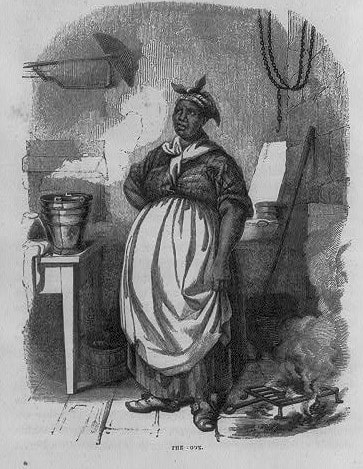

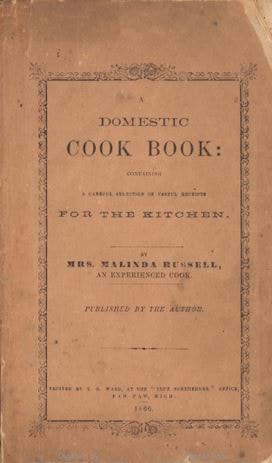

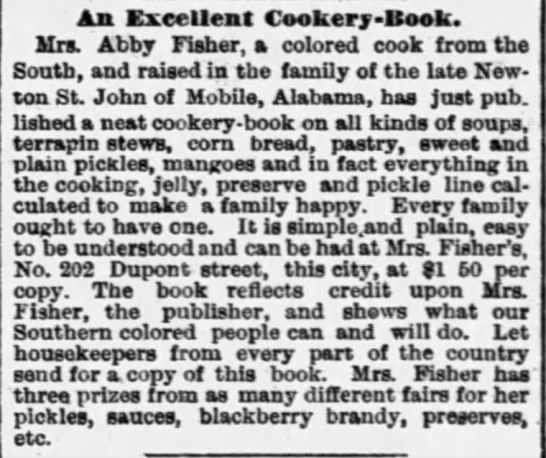

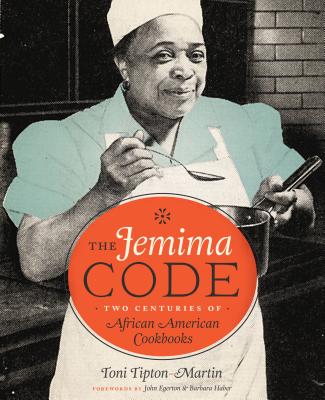

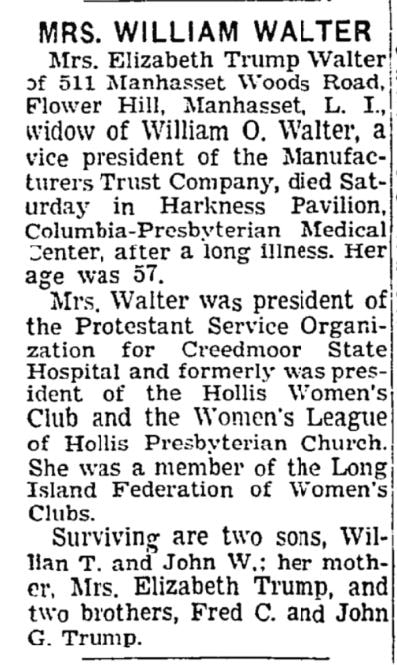

Throughout the 19th century, white women used their domestic assets to pick up the slack left by disabled or deceased husbands - homes became boarding houses and tea rooms and domestic skills were translated into magazine articles and cookbooks. But free Black women in the 19th century did not have as many assets. And even when they did, these assets were often taken from them, and a racist and sexist judicial system gave them little recourse to recover property. Enslaved women freed by the Emancipation Proclamation had their freedom, but little else. The promised 40 acres and a mule never materialized. Despite these often difficult starts, many free and formerly enslaved women of color used their wits and skills to make their own way in the world. Often relegated to service jobs in households, many women created their own small businesses to avoid working for wages - tea rooms, boarding houses, laundries, seamstress and millinery shops, catering, etc. Most of these jobs had low startup costs and could be done from home, allowing for the care of children and family members. Many women also worked as professional cooks for taverns and hotels, a job that held more promise of profit and respect than working in a private household. The vast majority of women working in these fields remain hidden from history - unnamed and un-written-about. But some women of color have managed to make their mark on food history. Here are a few of their stories. Anne Northup - Twelve Years AloneAnne Northup was my first real encounter with the stories of adversity and perseverance many Black women faced throughout the 19th century. I attended a special program at the Morris-Jumel Mansion in New York City with a historic dinner recreated by The Food Griot - Tonya Hopkins. Anne Hampton was born in 1808 in upstate New York. A free woman of color, she married Solomon Northup in the 1820s and in 1834 they sold their farm and moved to Saratoga. Solomon often worked as a fiddler and Anne worked as a cook and kitchen manager at hotels in the spa resort town. She was working at the Pavilion Hotel in Saratoga when she met wealthy white New Yorker Eliza Jumel in 1841. Divorcee/widow of Aaron Burr, Madame Jumel convinced Anne to come south and serve as a cook in her household. Anne sent her eldest daughter Elizabeth to Manhattan with Jumel, but waited until later in the year to come south herself, likely finishing out the busy tourist season. Earlier that summer of 1841, Anne's husband Solomon had answered an advertisement looking for musicians for a job in Virginia. An accomplished violinist, Solomon had answered the advertisement and traveled south. He was captured and sold into slavery, spending the next twelve years enduring brutal conditions on a Louisiana sugar plantation. Anne was left to fend on her own. After a year in Eliza Jumel's household, Anne and some (but not all) of her children returned to Saratoga, where they stayed until 1850, when they moved to Glens Falls and Anne continued her hotel work. They were not reunited with Solomon until 1853. He wrote a book about his experiences - Twelve Years a Slave. We lose track of Solomon Northup in the 1860s and his death date is unknown, although Anne and her children continue to live in New York. To learn more about the Northup family, read this excellent account by historian David Fiske. Anne Northup died on August 8, 1876 in Moreau, New York. Although she leaves behind no documentation of the food she cooked, given her positions in fashionable resort town hotels and wealthy households, she was likely very skilled in a variety of foodways. To me, she represents how many free women of color made their way in the world on the strength of their cooking skills, even in the face of extraordinary adversity. Malinda Russell & Her Union PrinciplesIn 2000, Jan Longone ran across a slim, crumbling cookbook wrapped in brown paper at the William L. Clements Library at the University of Michigan in Ann Arbor, where she is curator of American culinary history. That cookbook, A Domestic Cookbook, published in 1866 by a woman named Malinda Russell, turned out to be the earliest known cookbook published by an African American woman. The cookbook has since been digitized, and when I read it for the first time the other day, I was struck by the incredible hardship Russell had to overcome in her life. In the autobiographical account that explains why she wrote the cookbook, Russell recounted the many setbacks in her life. Born free in Tennessee, at age 19 she set out to emigrate to Liberia, a promise of life free from the racism and oppression that continued to plague free Black communities in the North. But along the way, she was robbed by someone from her party, and was forced to stay in Virginia, where she made a living as a cook and a nurse. There, she married Anderson Vaughn, and they had a son together, but Vaughn died just four years later, leaving Russell a widow with a handicapped son. She moved back to Tennessee and opened a boarding house in a town that featured springs as a tourist attraction. She later opened a pastry shop in that same down and had saved up a sum of money to support herself and her son. But in early 1864, she was attacked and robbed by a "guerrilla party," likely Confederate soldiers. She and her son fled Tennessee during the height of the Civil War. Although Tennessee was a Union state, its proximity to the border meant it was not safe for Russell. She made her way to Michigan, enduring several attacks along the way, and went on to start over, again, in a new state. In May, 1866, she published A Domestic Cookbook. She closed her introduction stating that she hoped the sale of the cookbook would help her raise funds to return to Tennessee and reclaim some of her lost property when peace was restored. We do not know if she ever made it home to Tennessee, or really much else about her at all, although Jan Longone has worked to find more about her. According to Russell herself, "I have learned my trade of Fanny Steward, a colored cook, of Virginia, and have since learned many new things in cooking." She also indicated her cookbook was organized along the lines of Mary Randolph's The Virginia Housewife (1824). Malinda Russell reset much of the conventional wisdom about Black cooking heritage at the time it was rediscovered. But her cookbook is not much different from any other cookbook of the period - reflecting her experience as a boarding house owner and cook, cooking for the public and likely for audiences diverse in race and socioeconomic status. It also knows its audience, consisting largely of dessert and preserves recipes. These were commonly featured in published cookbooks because they were more complex than the everyday cooking of meat and vegetables and less likely to be familiar to ordinary cooks. Her cookbook contains everything from the humble "Baked Indian Meal Pudding" and 'Sliced Sweet Potato Pie," to the exquisite "Floating Islands" and "Charlotte Russe." For me, the most striking thing about Russell is not the content of her cookbook, but rather the fact that it exists at all - a testament to her difficult life and the grit she used to persevere. What Abby Fisher Knew "Pickles and Fruit. The purest home-made Pickles and Preserves of all kinds, put up in the good old Southern style. A liberal discount to the trade. Address, Mrs. Abbey Fisher and Husband, 569 Howard St. San Francisco." Advertisement from the December 13, 1879 issue of "The Placer Herald," published in Rocklin, CA. Unlike Anne Northup and Malinda Russell, Abby Clifton was born into slavery in 1831 in South Carolina to a white father and an enslaved mother. It is unclear when gained her freedom, but by 1860 she had moved to Alabama and married Albert Fisher. In 1877, they emigrated to California and by 1880, Abby and Albert were in San Francisco, where the 1880 Census listed Abby as a "cook" and Albert as a pickle and preserve manufacturer. But this attribution was likely due to sexism common among census takers. In reality, it was Abby who was manufacturing pickles and preserves - as listed in an 1882 San Francisco directory. Albert was listed as a porter. Abby leveraged her expertise in pickles and preserves to reach the highest echelons of San Francisco society. She was awarded a diploma at 1879 Sacramento State Fair. At the 1880 San Francisco Mechanics Institute Fair, she won a bronze medal for her pickles and preserves. Although she and Albert could not read or write, in 1881 she published the cookbook, What Mrs. Fisher Knows About Old Southern Cooking, Soups, Pickles, Preserves, Etc. with assistance from white friends who helped her translate and transcribe her memorized recipes into cookbook format. The book does not contain just pickles and preserves, although they and her famous blackberry cordial certainly make a showing. The title inclusion of "Old Southern Cooking" is certainly apt, given recipes for "Maryland Beat Biscuit," "Plantation Corn Bread," "Ochra Gumbo," "Creole Chow Chow," "Sweet Potato Pie," and "Peach Cobbler." But it also includes typical British-American foods popular in the Northeast and throughout the United States, including "Sally Lund" bread, "Jumble" cookies, "Sauce for Suet Pudding," "Rhubarb Pie," (rhubarb grows poorly in the South, needing below freezing temperatures), three different kinds of "Sherbet," "Yorkshire Pudding," and "Terrapin Soup." In short, her cooking is more representative of broad American style cooking of the period, with some Southern flavor, rather than stereotypically "Southern" (i.e. Black) cooking. The interest in Southern cooking, as evidenced by the marketing of her book, was likely part of a reaction to the Civil War and Reconstruction. Historian Megan Elias has written about "Lost Cause cookbooks" in which white Americans romanticized the "good old days" of slavery and subservient Black folks with "magic" cooking skills. It is possible that Abby Fisher's cookbook was swept up in the wave of racist nostalgia. But it is also possible that Abby's cookbook was simply a reflection of the interest in California residents in the cuisines of many newly arrived emigrants of all cultures and backgrounds. This seems to be the case in one announcement, published in the San Francisco Examiner on July 11, 1881. It reads: "An Excellent Cookery-Book. "Mrs. Abby Fisher, a colored cook from the south, and raised in the family of the late Newton St. John of Mobile, Alabamaa, has just published a neat cookery-book on all kinds of soups, terrapin stews, corn bread, pastry, sweet and plain pickles, mangoes and in fact everything in the cooking, jelly, preserve and pickle line calculated to make a family happy. Every family ought to have one. It is simple and plain, easy to be understood and can be had at Mrs. Fisher's, No. 202 Dupont street, this city, at $1.50 per copy. The book reflects credit upon Mrs. Fisher, the publisher, and shows what our Southern colored people can and will do. Let housekeepers from every part of the country send for a copy of this book. Mrs. Fisher has three prizes from as many different fairs for her pickles, sauces, blackberry brandy, preserves, etc." Although we may never know how many copies Abby sold, the cookbook seemed to garner positive reviews. For several weeks in 1881, she (or the publisher) advertised it in the Oakland Tribune (see below).  "Mrs. Abby Fisher's, Southern Cookery book on soups, terrapin stews, sweet and plain pickles, mangoes, preserves, corn bread; price $1.50; 202 Dupont st., San Francisco. jy11-1m." Advertisement for Mrs. Fisher's cookbook in the "Oakland Tribune," published July 11, 1881, but running for several weeks prior and after. In the 1890 San Francisco directory, "Mrs. Abbie Fisher" was still listed as "mnfr. pickles and preserves," but it is unclear what happened after that. Her exact death date is also unknown. No known obituary was published. After the Great San Francisco Fire of 1907, reference to Abby and her cookbook all but disappeared until a copy surfaced in 1984 at a Sotheby's auction in New York City. The Schlesinger Library purchased it and at the time it was thought to be the first cookbook published in the United States by a Black woman, until Malinda Russell toppled Abby from her throne in 2000. Like Malinda and Anne, Abby used her cooking skills to make her own way in the world - supporting her family and showcasing her talents. Ghosts in the KitchenOf course, we know about these women because they left a written record. We know about Anne through her husband Solomon and his memoir, Twelve Years a Slave and the records of Eliza Jumel. We know about Malinda because of her cookbook and the autobiography she includes in it. And we know about Abby because of her cookbook and her existence in newspapers and city directories. But there were tens of thousands of women of color making their own way on the strength of their culinary skills, just like these women, throughout the 19th and 20th centuries. Ashbell McElveen called James Hemings the "ghost in America's kitchen," but he wasn't the only one. Enslaved women and men shaped American food profoundly. And women of color - enslaved, freed, and born free - left their mark as well. Because I know how history works, I am hopeful that more records and cookbooks of cooks of color - published or not - will continue to show up in the coming decades. And when they do, I know they'll help us better understand how our food got to be the way it is, and where it can go in the future. Further ReadingAnne Northup:

Malinda Russell:

Abby Fisher: