|

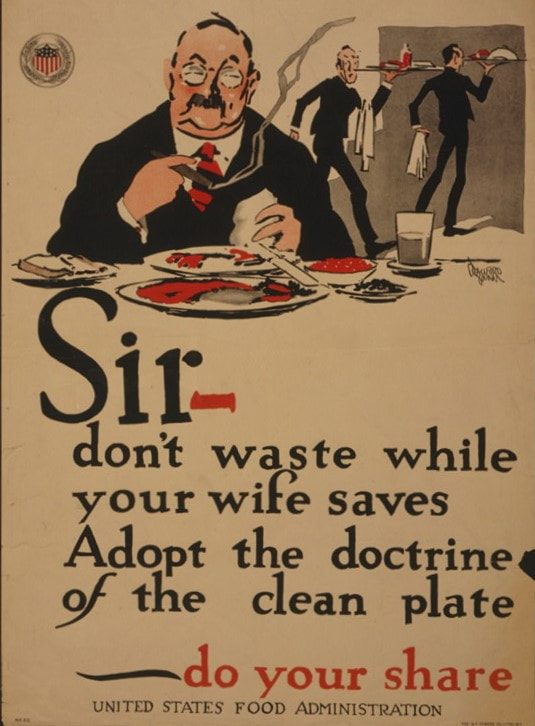

January is the time of year when many Americans, having made New Year's resolutions, try to eat healthier. But household food waste accounts for a good chunk of overall food waste, which besides being a big waste of water and energy, is also a contributor to the production of greenhouse gases. During both World Wars, food waste came up, but the First World War was a bit more significant. We were still coming off the effects of the Gilded Age, when wealthy Americans ate to excess, feasting on a great deal of meat, including some from rare or even endangered animals (for instance, terrapin, the diamondback turtle made so famous by soup, was hunted nearly to extinction and is still threatened to this day). Even as we underwent a series of depressions and industrial recessions between 1893 and 1914, the rise of restaurants and the proliferation of refrigerated railroad cars made more food accessible to more Americans than ever before. But WWI made global competition for resources more intense than ever. As the United States entered 1917 with only enough wheat to feed itself, and hog, beef, and dairy production designed largely for domestic consumption, Americans had to conserve in order to free up enough food to send overseas. The United States Food Administration's anti-waste campaign was part of that conservation plan. Progressives loved statistics, and used them to good measure. If each American saved just one slice of bread per meal, for instance, it would add up to hundreds of thousands of loaves, which would translate into plenty of wheat flour to be sent overseas. Combined with messages of thrift (curbing waste saves money) were subtle messages about weight and consumption that fit in nicely with the new Progressive values of self-control, an active lifestyle, and the willowy Gibson Girl physique. This propaganda poster is a good example of just that. A rather large man, reminiscent certainly of the rotund gentlemen commonly seen in Gilded Age paintings and photographs, sits alone at a table, smoking a cigar. Clearly he has finished eating, although there is still food on all of the numerous plates in front of him, and two waiters in the background bear away trays containing more half-eaten food. One of the slender waiters looks back incredulously at the diner. The text says, "Sir, don't waste while your wife saves. Adopt the doctrine of the clean plate - do your share." Restaurants in particular would come under the jurisdiction of the United States Food Administration, but while there were restrictions on bread service and sugar bowls and meat on the menu, the federal government could not stop people from ordering as much food as they could afford, whether they ate it or not. The reference to the wife was perhaps meant to shame men. Women were largely in control of the household meals, and many middle and upper-class women were taking to voluntary rationing with a vengeance. Perhaps wealthy men escaped to restaurants to eat as they pleased. The federal government was urging them not to undo the patriotic war work of their wives and to pull their own weight in the fight for food conservation. The first propaganda poster makes a slightly more subtle play, reading in part, "Leave a clean dinner plate. Take only such food as you will eat. Thousands are starving in Europe." Sound familiar? Perhaps your family used the (admittedly racist) "Children are starving in Africa," but the sentiment is the same. Photographs and images of children in Belgium and France were being used to good effect in the United States in an attempt to wake up isolationists to the terrors happening abroad. Both phrases use guilt and shame to get you to finish eating everything you took. Not exactly the most healthful advice, but at least during WWI they recommended you take only what you knew you could eat, instead of letting your eyes be bigger than your stomach. Although not as popular as calls to plant war gardens or can fruits and vegetables, the "gospel of the clean plate" nevertheless urged people to think more about food waste. Of course, as one woman complained in a letter to Herbert Hoover, the poor already saved food, planted gardens, ate less meat, and preserved what they could. Still it's advice that we would all do well to emulate today. We're pretty good at eating leftovers in my house, but sometimes we just can't finish them in time or (shocker, I know), dinner wasn't as good as you'd hoped, so eating the leftovers becomes a real chore. My leftovers usually make it to the compost pile, if not our stomachs. But other food waste reduction advice of the time included feeding But if you find yourself buying boxes or bags of leafy greens and salmon and fresh fruit in a fit of health this year, maybe hold off a bit, and eat down your cupboards instead. If you enjoyed this edition of World War Wednesday, consider becoming a member of The Food Historian! You can join online here, or you can join us on Patreon. Members get access to members-only sections of this website, special updates, plus discounts on future events and classes. And you'll help support free content like this for everyone. Join today!

0 Comments

Your comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

AuthorSarah Wassberg Johnson has an MA in Public History from the University at Albany and studies early 20th century food history. Archives

July 2024

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed