|

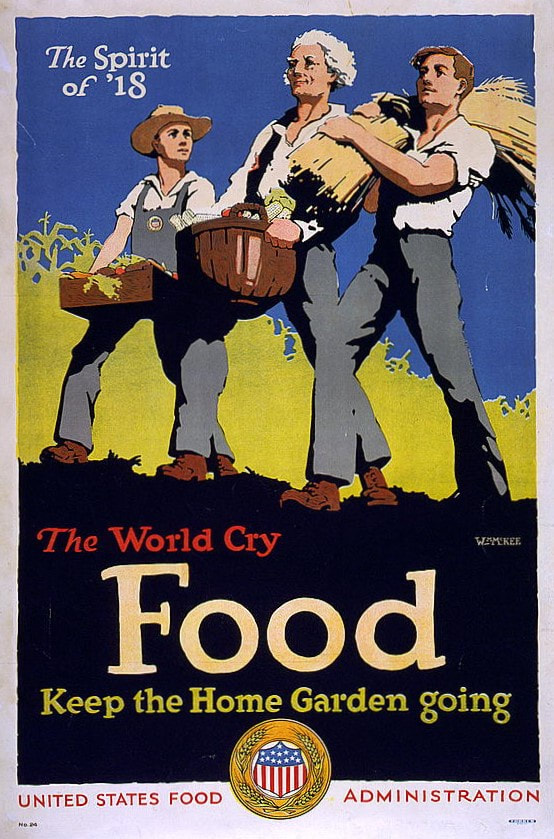

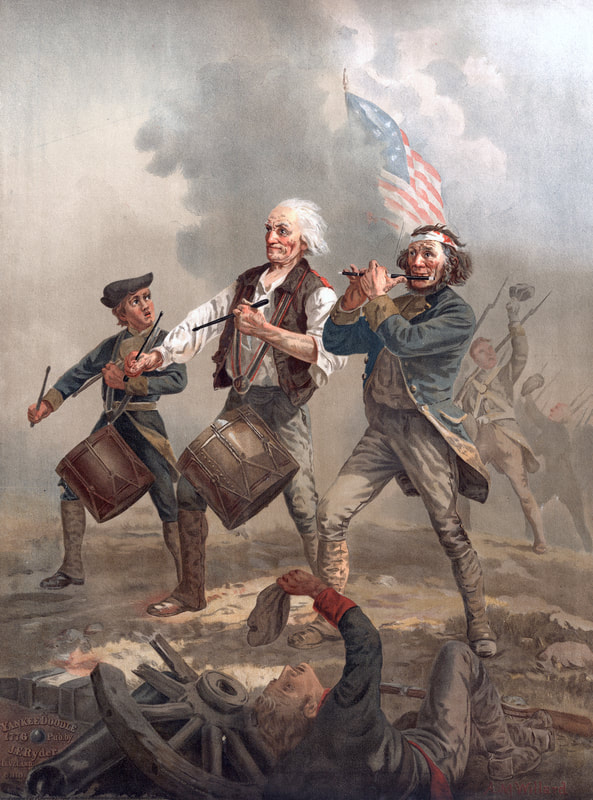

Last week we featured a propaganda poster from World War II that hearkened back to Valley Forge. This week we're featuring a propaganda poster from World War I that also hearkened back to the American Revolution - "The Spirit of '18." During the First World War, the United States Food Administration, along with private organizations like the National War Garden Commission, encouraged ordinary Americans to plant war gardens (later termed "victory gardens," a name that stuck when revived in the Second World War). War gardens were needed to free up commercial agricultural products to send overseas to American Allies, many of whom were suffering after three years of privations, and to feed American troops abroad. In particular, the 1915 and 1916 wheat harvests had been poor, leaving little to export. In order to free up domestic supplies for shipment overseas, the government encouraged Americans to grow and preserve more of their own food, alleviating the domestic strain on food supplies and freeing up commercial foods for government use. This was a tactic which was revisited during World War II. In this poster, a young boy wearing overalls bearing the US Food Administration seal, carries a wooden crate of vegetables. He looks on at the older man in the center, whose haircut brings to mind George Washington, and who carries a larger basket of produce. At the far right, a young man carries a sheaf of wheat on his shoulder. All are marching in step, a stylized cornfield and a brilliant blue sky behind them. "Spirit of '18," the poster reads at the top. Below, it says, "The World Cry Food - Keep the Home Garden Going," with the United States Food Administration title and seal at the bottom. Although it doesn't seem like it on the surface, this poster references the American Revolution. It is based on a very famous image which would have been familiar to Americans at the time. Painted by Archibald MacNeil Willard in 1875 for the 1876 Centennial Exposition in Philadelphia, the painting which became known as "Spirit of '76" was revealed to little critical acclaim, but great popularity among ordinary people. Willard reproduced it several times. The original was enormous - eight feet by ten feet. The above image of "Spirit of '76" is a chromolithograph produced by J. E. Ryder for the Centennial Exposition and sold to tourists as a souvenir (see the original here). This helped its popularity greatly, as it was widely panned by critics as too dark. The painting illustrates two drummers - one elderly and one a young boy, accompanied by a wounded man playing fife - behind them flies the American flag (or perhaps the Cowpens battle flag) and more troops waving their tricorn hats - evoking perhaps that the resolute fife and drum corps are leading a column of relief troops, bringing victory to the battle that wounded the artilleryman in the foreground with his cannon on the ground, its carriage broken. You can see how closely William McKee mirrored the work of Archibald Willard - the three figures in both images are nearly identical - a young boy, an elderly man, and a young man, although in the World War I poster the young man is considerably younger and more Adonis-looking than Willard's figure. The figures represent the three generations - youth, adulthood, and old age, as well as the breadth of men participating in the American Revolution and World War I. During the Revolutionary War, musicians were usually boys too young and men too old to enlist as regular soldiers. Old men and young boys were also "drafted" during the First World War for home front duties, including gardening and farm labor. In both images, the figures are marching forward, bringing victory behind them. Archibald Willard died on October 11, 1918, exactly one month short of the end of World War I. So it is possible he saw his work replicated in this poster. "Spirit of '76" was his most popular and enduring work, but it did not bring fame or fortune. For other Americans who saw the "Spirit of '18" poster, it surely would have instantly brought to mind the "Spirit of '76," and the sacrifices and courage of the American Revolution, inspiring similar levels of patriotism and sacrifice by Progressive Era Americans during the First World War to "do their bit" and contribute to the war effort through war gardens. The Food Historian blog is supported by patrons on Patreon! Patrons help keep blog posts like this one free and available to the public. Join us for awesome members-only content like free digitized cookbooks from my personal collection, e-newsletter, and even snail mail from time to time!

1 Comment

Anna Katharine Mansfield

3/4/2021 02:59:12 pm

I went down a rabbit hole looking up Ryder, and found that he was more famous as a photographer than a lithographer, and that he grew up near Ithaca, NY. Thanks for the post! https://vintagephotosjohnson.com/2011/11/23/james-fitzallen-ryder/

Reply

Your comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

AuthorSarah Wassberg Johnson has an MA in Public History from the University at Albany and studies early 20th century food history. Archives

July 2024

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed