|

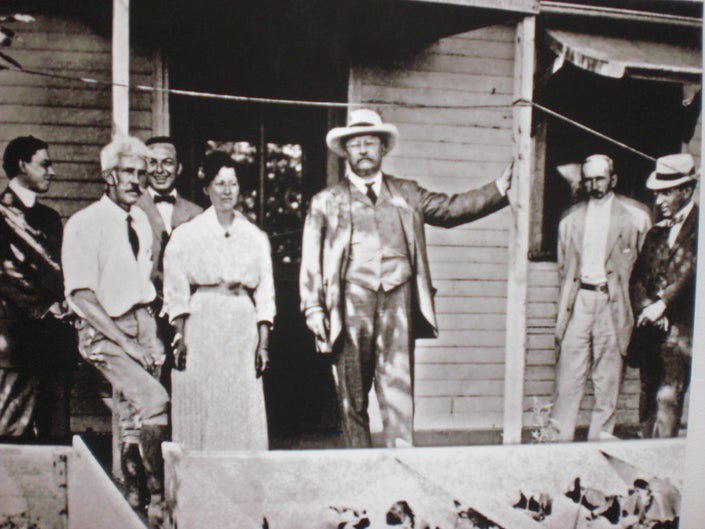

One of the things I do when collecting research for my book is to transcribe newspaper articles. They can be invaluable sources of important information, particularly when filling out a timeline or compiling information about historical people. But they can also be delightfully amusing reads, as this article I came across in New York City's The Sun newspaper, published on June 10, 1917. Farmerettes and women as agricultural labor was a new idea for most people in the First World War, but in New York the use of young, single, white women as paid agricultural laborers dates to 1911. In this article from 1917, the author, Jeanne Judson, visits Hal and Edith Fullerton's farm on Long Island. Hal Fullerton was the agricultural agent for the Long Island Railroad and an agriculture booster in the region. His wife Edith was an accomplished gardener who went on to author books on gardening and canning. This research is for a new chapter in my book on agricultural labor efforts in New York during the First World War. So I have to track down extra information on farmerettes who, believe it or not, lasted in New York State until the 1920s. "Doubting Thomas's Sister Looks Into Possibility of Farming For Women. She Visits a Long Island Farm Where Women Have Been Employed for Three Years and Comes Away Not Only Convinced but Envious." Original caption: "Women Workers Aid in War Time. Two women working plow on farm of New York State Agricultural School at Farmingdale, L. I. After completion of their courses the women will be capable of teaching others the art of farming. The class was established by the New York Women's Section of the Navy League." Underwood & Underwood photographers. April, 1917. National Archives. (Editor's note: This is a verbatim transcription of the article, "Doubting Thomas's Sister Looks Into Possibility of Farming For Women. She Visits a Long Island Farm Where Women Have Been Employed for Three Years and Comes Away Not Only Convinced but Envious," by Jeanne Hudson and published in The Sun on Sunday, June 10, 1917. The photos have been added by me and are not original to the article.) There are thousands of women in America who realize that they would not adorn the uniform of a Red Cross nurse, all masculine realists and sceptics to the contrary. There are even a few women who are in some doubt as to whether after all there may not be a lot of women who can roll better bandages than they can. And besides there are so many other things to do, and when the average woman analyzes the situation, so pitifully little equipment with which to do them. The lists of things to do for the country are so long - motor car drivers (most women don't know much about driving motor cars), wireless telegraphers (after all it does take time to learn that), camp cooks (doesn't sound very alluring and doubtless all the camps will have men cooks anyway); but farm work? When the call to the farms was issued we all - that is all the willing feminine patriots more distinguished for zeal than for training - sat up and took notice. There were training camps formed and the smartest possible khaki uniforms purchased, scarcely more expensive than a really smart bathing suit if one didn't count the boots. Even then there were some women who still sat at home wondering whether, after all, the women could really be of use on the farms. And the result of all this serious thought led one woman to investigate.  Hal and Edith Fullerton (left, in shirtsleeves) with Theodore Roosevelt, c. 1910. Suffolk County Historical Society. Hal Fullerton and Theodore Roosevelt were both members of the Long Island Food Reserve Battalion, which was active in food production and conservation during WWI. The battalion was founded by Long Island Railroad President Ralph Peters. Off for the Farm. There being no feminine form of the term Doubting Thomas, we will have to call her the timid farmerette. She was thoroughly convinced that she ought to be a farmer, but she didn't know how. So she sought the advice of the woman in New York State who probably knows more about farming than any other, Mrs. Fullerton, wife of H. B. Fullerton, who has charge of the demonstration farm of the Long Island Railroad. At 7 o'clock one fine May morning, about an hour after Mrs. Fullerton had breakfasted, the timid farmerette rose and ate a cold storage egg, preparatory to taking the 8:30 train from the Pennsylvania station that would lead her to a real farm and knowledge. Her trip led her through a lot of farms punctuated by small towns. She had seen farms that way before and thought them very pretty, so green in spring and so yellow in autumn. She didn't know why they were so yellow and green, but she had observed that much about them anyway and began to feel encouraged. To be sure she did not see any women working in the fields, with the exception of one old woman, who was hoeing, and that woman didn't have on khaki, just an old frock, not a bit artistic. The timid farmerette doubted if she had ever heard of agricultural volunteers. Even when the train passed Farmingdale there were no signs of feminine activity, but doubtless the school in which agriculture, first aid, diet and wireless telegraphy are taught was not yet open. She was nervous as to whether the train would actually stop at the farm and asked the conductor about it. "We've got to stop; Mr. Fullerton's on board," said the conductor. "You can see him through there in the smoker - the man in uniform." She looked through and saw him, and soldierly appearing man in a Boy Scout's uniform. His hair was gray and the gray mustache combined with the broad brimmed hat made her think of those Western films. So just before the train stopped she talked to him on the platform and introduced herself. "Just talk to Mrs. Fullerton for a few minutes; she'll set everything straight for you," he said in a husky voice. "You see I've been lecturing and I'm a bit hoarse," he explained. "They've created a new job for me. Grub Master of the Boy Scouts. You know what grub is?" "Oh yes, food," answered the timid farmerette. "Food's right; and the biggest thing in the world to-day," said Mr. Fullerton. Contrasts in Clothes. The next minute they were off the train and Mrs. Fullerton was condoling with Mr. Fullerton over his hoard voice and word tortured throat even while she greeted the timid farmerette. Behind her a Boy Scout stood in an attitude of soldierly attention, until his mother sent him off to get some medicine for father's throat. Then they all walked up the flower bordered path together, past the bird's bath and the guinea pigs' hutch and into the cool, wide open living room of the farmhouse. Here Mrs. Fullerton looked at the timid farmerette for the first time thoroughly. The timid farmerette was not clad, as was Mrs. Fullerton, in a short khaki skirt and a shirt waist above and leggings and stout boots below. By contrast the timid farmerette somehow reminded one of the cold storage egg she had eaten that morning at breakfast. There had been good material in her once. But if Mrs. Fullerton thought of this she concealed it. "Mr. Fullerton has just come back from a lecture trip in his capacity of grub master for the Boy Scouts and there are a number of telegrams and letters here that he must see. If you could amuse yourself for a few minutes looking over things, we'll be with you presently." "Certainly, by all means," murmured the timid farmerette and in another moment she was outside again and wondering what to do next. Near the farmhouse was a tall, round building with stairs winding up to the top. "It's got something to do with the water," thought the timid farmerette and she began climbing to get the view. It Looked Very Easy. On top there were seats and the timid farmerette rested there and looked out over things. It didn't look like such a very big farm. Afterward she learned that there were eighty acres in the farm and that there were eighty acres in the farm and that twenty-two acres were under cultivation, but no one would have dreamed that those small squares of green and brown really covered twenty-two acres. There was a building that she guessed to be the dairy and here in the field nearest the house was a man pushing some sort of small plough between rows of green things. Further off she was delighted at seeing a woman bending over other rows of green things. The woman had on a rather short dark skirt and a boy's cap pulled close down over her hair. The timid farmerette decided to go down and talk to the man. He was nearest. When she reached the field the man was at the other end. She looked closely at the rows of green things and decided that they must be clover. They looked just like clover, only she had a vague impression that clover wasn't planted in rows that way. She stood still while the man started up the next row and came slowly toward her. If that was all there was to farm work she could do it all right. As the man drew nearer she saw that he was smiling. He didn't seem to be a bit surprised at seeing an inquiring woman in high heeled slippers waiting for him. He had seen a lot of them in the last few weeks. They were always either dressed like the heroine of his favorite Western drama or else they had on those silly high heeled pumps with silk stockings, and both costumes seemed equally amusing. "I'm cultivating; this little plough is a cultivator," he explained affably before the question was out of her mouth. "Clover?" He smiled more broadly. "No, it's peas; they do look something like. Lots of people make that mistake," he assured the blushing farmerette. "Do you mind - would you be willing to let me try it for one row?" she asked eagerly. Something in the cheerful reluctance with which he assented made her think of a certain fence that Tom Sawyer was once set to whitewash, but she started bravely out, leaning heavily on the slip handles of the plough, while her high heels sank into the soft, black earth. "Take it easy," cautioned the farmer. "Here, let me show you. You go forward and then back a few inches to get a new start, and don't go too deep. Careful - keep in the center of the row, else you'll tear up the plants." An Expert's Opinion. So he walked along outside the field, giving instructions and smiling at some joke that was not to be put into words for the benefit of city folk. They wouldn't understand anyway. Whether the timid farmerette would have tried another row or not the farmer never knew, for before she had finished her row Mr. and Mrs. Fullerton had come out of the farmhouse and were waiting to talk to her. "Now what do you want to know?" asked Mrs. Fullerton. "First, is it really practical? Can women really be of use on American farms and are they really needed?" "They certainly can be of use and they are needed. We have used women on the farm here for the last three years. I'll introduce you to one later. It's her first year on this farm but it is her third summer at farm work." "How about the training camp at Farmingdale?" asked the timid farmerette. "That is useful only as an eliminator of undesirable workers. In the twenty days course any woman can at least discover whether she is fitted for work on a farm. They'll find out something of what farm work really means. It is never easy under even the most favorable conditions, such conditions as you find on a farm like this, and on the average farm it is something like drudgery to the woman who has been accustomed to every convenience and comfort. Here, for example, is where our two women workers live." She pointed to a small portable house. "Come in and I'll show you." Inside the small house was shown to contain four rooms, a living room, a kitchen and two bedrooms, as well as a very nice bath. "They don't eat here," Mrs. Fullerton explained. "All of our farm workers eat in the farmhouse, but you would have to search far on American farms to find farm laborers provided with a private bath, comfortable sleeping rooms, and a sitting room of their own." Manicurist and Farmer. "The two women who sleep here are Mrs. Thomas Newton, who is the dairy assistant, and Miss Scott, the girl of whom I spoke, who is spending her third summer at farm work. In the winter time Miss Scott is a manicurist and hairdresser. Last winter she worked at the Ritz-Carlton. Mrs. Newton's husband is the farmer who let you run his cultivator. He is our market gardener." "You must see the dairy," said Mr. Fullerton. "Mrs. Fullerton is the best butter maker in America, if you are to believe the medals, and if you don't we'll let you stay to lunch and taste the butter." Mrs. Fullerton has for two years won the highest award for her butter in both Chicago and New York shows. "How do you do it?" asked the timid farmerette. "It's really just a matter of cleanliness; everything about the dairy must be scrupulously clean. If you make sure of that the good butter follows as a matter of course." From the dairy they walked around to another field where Miss Scott was weeding something or other. The timid farmerette felt so crushed with ignorance by this time that she did not ask what, but she had a little prideful swelling of the heart as she clasped the dirt soiled hand of Miss Sadie Scott. One Woman's Experience. The young woman pushed her boy's cap back a bit from her eyes and talked in a modest way about her work. "No, it isn't just a patriotic thing with me," she said. "I've always liked farm work. This is my third season. I worked one year on a farm in Michigan. They took me because they wanted workers very badly and I had to work right along with the men. "It was too much for me; women can't really stand as much manual labor as men can, you know. Then last year I worked on an estate in Westchester." She laughed softly, "It's funny how I got on there. They only consented to give me the job because the women in the house thought it would be nice to have someone at hand who could wash their hair and manicure their nails. That's my work in the winter time, you know. "But this is my first chance at anything like scientific farming. If I had any money I would have gone to agricultural college. It's what I've always wanted. Here I am learning things." She pulled up a plant and showed the timid farmerette some funny little knots on the roots. "That's where the plant is storing up nitrogen," she explained. "The roots are left in the ground and the nitrogen fertilizes the soil for next season's crops." "We never buy any chemical fertilizers here," said Mrs. Fullerton. "We keep the soil in good condition by a proper rotation of crops." "Do you think that I could be of some use?" asked the timid farmerette as they walked back toward the farm house. "Every woman in America can be of use. First by economy in her own home. Second, if she has any land at all, even a kitchen garden, by raising the things that will last - potatoes, cabbages, turnips and such vegetables as can be stored for winter use. If every woman just raises enough for the needs of her own family she will be doing a great service, for then her family will not have to draw from the national food stores. "Above all I think that the woman who cans things for the soldiers to eat is rendering the greatest possible service to her country. One of the biggest needs of the soldiers in Europe has been fruit juice. The demand for jam has become a popular joke, but there is nothing funny about it. It is a real need and this year not one particle of fruit must be allowed to go to waste. That's the reason for the canning train that the Long Island Railroad is sending out over Long Island to teach women how to preserve food. "It isn't just fruit, either. Almost everything can be canned, spinach, asparagus, chicken, tomatoes, corn and even eggs. "We've been canning ourselves this week. Come in and I'll show you." She led the way to a small building. "It is really the children's schoolhouse but they are away at school now and have lent it to us for canning. These little cans are rhubarb and orange marmalade and these are spinach. Every woman in America can help in this work. "I don't imagine that there will actually be many women working on the farms this year. But they are at least learning something of farm work, and next season when the men are fighting they will be prepared to take their places. "The principal thing is to see that not one bit of the crop this year is wasted. Apples must not be allowed to lie on the ground and rot. Vegetables must not be thrown away. Even the woman who lives in the city and cannot raise anything herself can at least buy while vegetables are cheap and can them to use in her own home next winter." The Doubter Convinced. It was noon and the timid farmerette tried very hard to be reluctant about accepting the hospitable invitation to lunch, but somehow in that atmosphere of sincerity she couldn't do it and ended by admitting that she was hungry and that nothing she could imagine would be more welcome than sitting down at the long table in the farm dining room and having what Mr. Fullerton modestly admitted was a regular meal. "We have to eat in town sometimes," he explained, "and we always regret it. I don't see how city people live on the stuff they eat." Under ordinary circumstances the timid farmerette would have been a bit ashamed of the quantity of homemade bread and prize butter that she ate, but she was beyond shame now. She was wondering between mouthfuls just how she could arrange to pawn her typewriter or sell it outright - after all, she never wanted to see it again - and get a job on a farm. Mr. Fullerton was telling her about the Boy Scouts - how they mobilized almost five thousand of them in three days and how they were busy doing their bit for the Grub Master. Free Land for Women. Mrs. Fullerton told her how they had offered the uncultivated land of the farm free to any women's organization that wanted to take it over for cultivation. "No one has accepted the offer so far," she said. "They are all eager to do something, but I suppose there must have been some difficulty about getting funds to build the necessary barracks for the accommodation of the women. We offered them water and light and the land free of charge, but no one has taken it up. It is too bad that so much land should lie idle." The timid farmerette thought cynically of women's cavalry corps and like useless organizations parading on Fifth avenue, but she did not voice her sentiments. Somehow she couldn't when she found herself taking the train back to New York without having asked for a job on the farm. Habits are hard to break, and even while she thought of the demonstration farm her ears caught the roar of the approaching city and she sighed a bit and decided to wait for a while before she sold the typewriter. Wasn't that a delightful article? If you'd like to learn more about the Woman's Land Army of America, which was the main (but not only!) thrust of farmerette activity during the First World War, check out the excellent book The Fruits of Victory by Elaine Weiss. As for the rest of the farmerette story in New York? You'll have to wait for my book! Edith Loring FullertonSadly, the main holders of all things related to Hal and Edith Fullerton, the Suffolk County Historical Society, don't seem to have much about them online and as far as I can tell neither have a Wikipedia page. But all of Edith's books are in the public domain. So if you'd like to read them, just click on the links below!

Hal Fullerton, who was significantly older than Edith, was the agricultural agent for the Long Island Railroad, and when he retired the position went to Edith. When she died in the 1930s, the position at the Railroad was retired. If you enjoyed this transcribed article from 1917 and would like to support my book and writing work, please consider becoming a patron on Patreon! Patrons get special perks like members-only content, including access to draft chapters of my book.

0 Comments

Many thanks to the Southeastern New York Library Resources Council for hosting my talk and for recording it! Much (but certainly not all!) of the research I've done for my book is presented in condensed form here. I think it turned out very nicely indeed and I am now contemplating recording more of my talks for sharing online. What do you think? Should I?

Here is some further reading based on some of the topics I discussed in the talk:

Capozzola, Christopher. Uncle Sam Wants You: World War I and the Making of the Modern Eighmey, Rae Katherine. Food Will Win the War: Minnesota Crops, Cooks, and Conservation during World War I. St. Paul, MN: Minnesota Historical Society Press, 2010. Gowdy-Wygant, Cecilia. Cultivating Victory: The Women's Land Army and the Victory Garden Movement. Pittsburgh, PA: University of Pittsburgh Press, 2013. Hall, Tom G. “Wilson and the Food Crisis: Agricultural Price Control during World War I.” Agricultural History 47, no. 1 (1973): 25-46. Hayden-Smith, Rose. Sowing the Seeds of Victory: American Gardening Programs of World War I. Jefferson, NC: McFarlan and Company, Inc., 2014. Veit, Helen Zoe. Modern Food, Moral Food: Self-Control, Science, and the Rise of Modern American Eating in the Early Twentieth Century. Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina Press, 2013. Weiss, Elaine F. Fruits of Victory: The Woman’s Land Army of America in the Great War. Washington, D.C: Potomac Books, 2008.

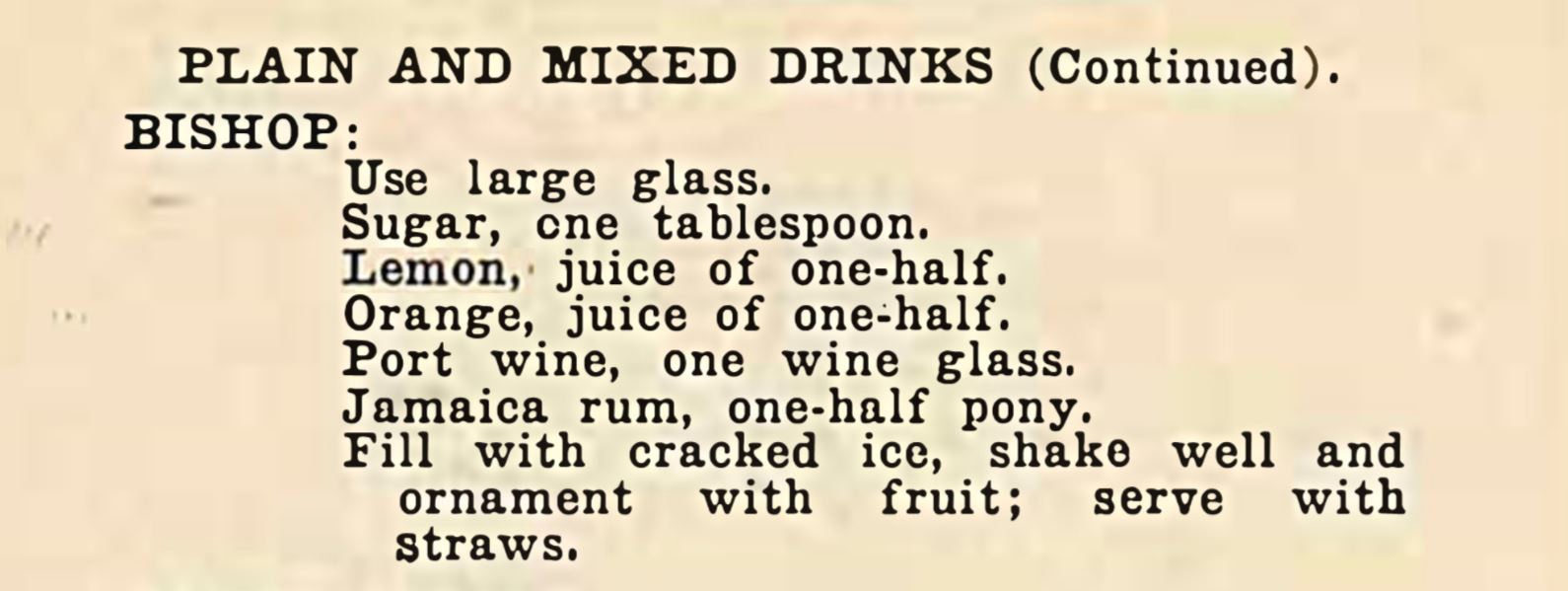

If you or your organization would like to host a talk - virtual or otherwise - please make a request!

This post was supported in part by Food Historian members and patrons! If you liked this post, please consider becoming a member or joining us on Patreon. Members and patrons get special perks like access to members-only content. Thanks to everyone who joined me on Friday for Food History Happy Hour live on Facebook. This week, in commemoration of Memorial Day, we talked about its Civil War origins, the history of grave decoration as Decoration Day, cemetery picnics (and picnics in general), history of refrigeration, how food was preserved before refrigeration, including canning, with mention of my book review of Canned, a discussion of fireless cookers/hay boxes, including Sabbath cooking, historical spring (spoiler alert: June used to be spring), book update, including WWI New York City soldiers' canteens, agricultural labor shortages, comparisons between WWI and the coronavirus pandemic, and what I've been reading recently. Bishop Cocktail (1906)I've been looking for a port wine cocktail for a while so that I could crack open my new bottle of Brotherhood Winery's Ruby Port, which is delightful. And, as Anna Katherine pointed out, Friday was Drink Local Wine Night! And Brotherhood Winery - the oldest winery in the country - is located just a few miles from my house. As I mentioned in the video, the Bishop cocktail (notice that the Black Stripe is the very next recipe!) ended up tasting very similar to sangria, which is not a bad thing. But I would definitely cut down on the sugar next time. And having looked it up since the show, Jamaican rum is a dark rum - not at all close to the white Puerto Rican rum I was using. But in a global pandemic, you use what you've got! This cocktail comes from the 1906 How to Mix Drinks: Compiled, Selected, and Concocted by George Spaulding. Here's the original version, with my notes: Use large glass. Sugar, one tablespoons [try one teaspoon instead] Lemon, juice of one-half [or 1 tablespoon bottled] Orange, juice of one-half [or 2 tablespoons bottled] Port wine, one wine glass [ooops! I did a half, you can too] Jamaica rum, one-half pony [1/2 oz.] Fill with cracked ice, shake well and ornament with fruit [I used blood orange]; serve with straws. If you liked this post and would like to support more Food History Happy Hour livestreams, please consider becoming a member or joining us on Patreon. Members and patrons get special perks like access to members-only content.

Thanks to everyone who joined me last night for Food History Happy Hour live on Facebook. I had a blast and everyone asked such great questions!

In this week's episode, we covered a LOT of ground and discussed how applejack is made, shrub, eugenics, Americanization of immigrants, comparisons between modern issues with dairy farming, dumping milk, and plowing under fields of vegetables and what happened during WWI and the Great Depression, types of dairy cows and how dairy farming works (including a discussion of veal), Victory gardens, agricultural policy history, historic baking, and flips (including Tom & Jerry). WHEW! The hour flew by and I had so much fun. You can watch the whole thing below.

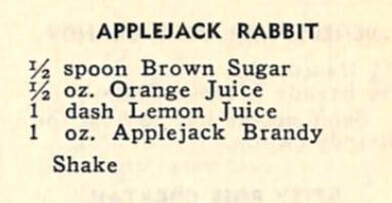

And of course, I made a vintage cocktail! This week's cocktail is the Applejack Rabbit and it comes from the 1946 cocktail book, The Roving Bartender by Bill Kelly.

We talked a little bit about cocktail glasses and serving sizes because of course this week I did NOT use a Collin's glass, but rather a small martini glass. In his introduction to The Rover Bartender, Kelly writes, "As the drinks are shorter now, the glasses for mixed drinks should be shorter and the drink recipes in this book are especially for cocktail glasses of not over 2 1/2 ozs. If a larger glass is used, the proportions will have to rise. You may serve a pony of cognac in a 20 oz. snifter glass, but if a cocktail glass is not near full it is unsatisfactory to the customer." I can certainly agree! But as someone who prefers a cocktail to be only a few ounces, I can't say I enjoy the generally much larger glasses of modern bars and restaurants. They may be easier to handle and clean, but they're too big! Applejack Rabbit Cocktail (1946)

The original recipe is as follows:

1/2 spoon brown sugar (I used about half a tablespoon) 1/2 oz. orange juice 1 dash lemon juice 1 oz. applejack brandy Pour over ice in a cocktail shaker and shake for longer than you think you should to make sure the brown sugar is dissolved. Strain into a small cocktail glass, such as martini glass or old-fashioned champagne glass. Sip cold. Virginia Apple Cake Recipe

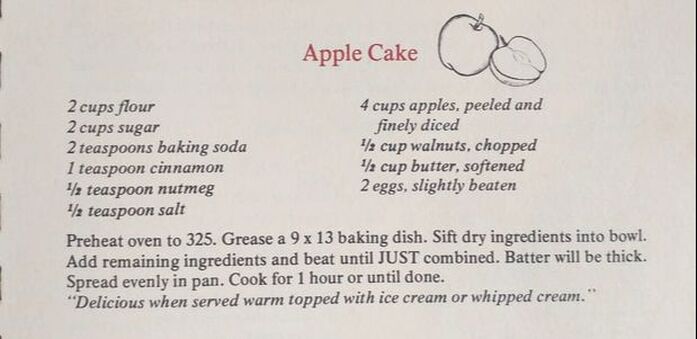

And, since we talked about historic baking, I thought I would share the recipe for apple cake I found recently in my copy of Virginia Hospitality (1976, my copy is the 1984 reprint). This particular Junior League cookbook is quite good with many of the recipes arranged by region and with decent head notes for many. Alas, this "Apple Cake" has neither headnotes nor region assigned. But it looked intriguingly easy and used up quite a bit of apples.

However, as I discussed in the episode, it really is a strange cake. As such, while I've included a photo of the original recipe, I've written my own version to help walk you through how the recipe should work.

2 cups flour

2 cups sugar 2 teaspoons baking soda 1 teaspoon cinnamon 1/2 teaspoon nutmeg 1/2 teaspoon salt (note - I would add 1 teaspoon next time, the cake tasted a bit "flat") 4 cups apples, peeled and finely diced (about 3 medium apples) 1/2 cup walnuts, chopped 1/2 cup (1 stick) butter, softened 2 eggs slightly beaten Preheat oven to 325 F. Grease a 9"x13" baking dish (I used metal). Whisk dry ingredients in a bowl, then add apples and walnuts and stir to coat. If butter is refrigerated, microwave in 10-15 second intervals until very soft but not totally melted. Add butter and eggs to the dry ingredients and mix/fold with a wooden spoon until no loose flour remains. It will seem like not enough moisture - just keep folding, it will come together. The batter will be very thick. Do not overbeat. Spread evenly in the pan. Bake for 1 hour or until done. (I baked mine for 1 hour and 5 minutes, as the middle still seemed a bit soft). In all, my husband LOVED this recipe, but it was not my favorite. Next time I would definitely add some extra salt as the cake tasted a bit "flat" without it. In retrospect, I also MIGHT have accidentally added 2 teaspoons of cinnamon instead of one? Oops. It was too much cinnamon for me, but as I said, my husband loved it as it reminded him of carrot cake. Baking it for an hour at 325 seemed like way too long, but it did result in nicely caramelized edges (all that sugar). However, all the apples melted into the cake! So next time I would probably cut them a bit bigger. I did almost mince them in some cases.

So what did you guys think of this week's episode? Are you going to join me next Friday on Facebook? I hope to see you there! Thanks again to everyone who watched live and remember, if you have any burning food history questions, you can send them to me in advance, message The Food Historian on Facebook, or ask live during the broadcast. See you soon!

If you liked this post and would like to support more Food History Happy Hour livestreams, please consider becoming a member or joining us on Patreon. Members and patrons get special perks like access to members-only content.

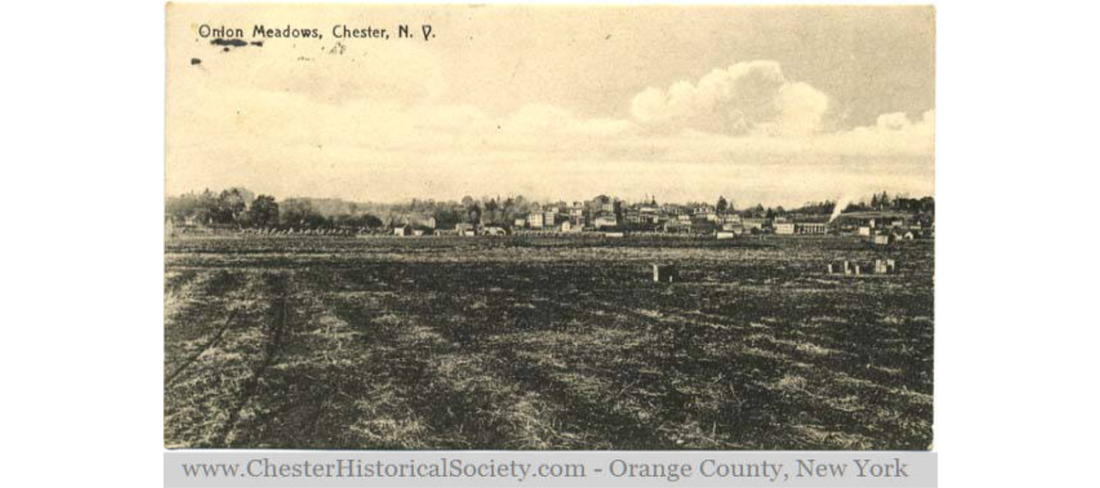

Okay folks. Here's where the history gets real. I've felt often in the last several years that the events of the 1910s were being mirrored in the events of the 2010s. Case(s) in point: rising income inequality, issues with immigration, the vilification of socialism, women's rights, Civil rights, voter suppression, marches for social justice - all these things happened in the 1910s and are happening again today. But one thing I did NOT expect to see, was this recent article from Civil Eats, outlining the struggle of onion farmers, particularly those practically in my own back yard in the black dirt region of Orange County, NY, as they deal with plummeting wholesale prices - so much so that a federal inquiry has been ordered. What. This is straight out of 1916 and my book research. Government inquiries and all. You see, in the winter of 1916/17, food prices had gone up exponentially and working class women in New York City, mostly Jewish women on the Lower East Side, staged food boycotts of a variety of produce, including onions, to protest prices that had doubled or tripled in a matter of weeks. Prices did lower eventually, but not before onions were virtually rotting in railroad yards and warehouses. Farmers in the black dirt region struggled to deal with the surplus and turned to other options as a means of potentially saving their quite perishable crop. Here are some excerpts from my book about the both sides of the situation: Pushcarts remained in service for the time being, however, and Jewish women in particular had had enough of rising prices. Mere months ago their husbands’ wages had bought plenty of vegetables with room for a shabbos chicken and other occasional luxuries. According to a New York Times investigation, February of 1917 left many families barely subsisting on coffee, tea, bread, and rice. Most could not afford potatoes, much less meat. Laborers who used to eat onion sandwiches every day for lunch could now not even afford onions. Wages had to be used for rent, wood or coal for heat, and clothing in addition to food. For many households, food was the one budget item with some wiggle room. But now their budgets were squeezed beyond bearing. Those making ten dollars or more per week were scraping by. Those making less were forced to rely on family members or charity to survive.[1] To working families, the fact that their circumstances had not changed but they suddenly could not afford even the cheapest of foods was not only a hardship, it was an affront to the promise of capitalism. Some families coped by taking on extra work; others coped by eating less or lower quality food. Some grew desperate as “investigators for the city’s charity department found people eating ‘decayed’ potatoes and onions,” although perhaps investigators’ definitions of “decayed” differed somewhat than those of the poor. For many, protest was the best coping mechanism. By February 20, 1916, the Jewish women of the Lower East Side, assisted to some extent by Socialist political groups, organized neighborhood boycotts to try to drive prices down. The violence with which these women enforced the boycotts—assaulting those who broke the boycott, destroying vegetable carts, and attacking storefronts—shocked Progressives and the general public alike.[2] By noon, the boycott had swelled its ranks with poor and working class women and their children who clamored at the gates of Mayor John Mitchel of New York City, holding up their babies and demanding bread. Mitchel refused to meet with them, suggesting that representatives meet with him the following day. The authorities, unable to solve the food price issue and at a loss when it came to dealing with violent and rioting women, did little except arrest and jail the rioters. Most of the women arrested in New York City were later broken out of jail by their free counterparts.[3] Perhaps inspired by the women of New York City, food boycotts and rioting quickly spread across the country. On February 21, riots broke out in Philadelphia; on February 22, in Boston. On February 23, newspapers reported that people in Alabama and Mississippi were near starvation as "for weeks only 6 per cent of the usual allotment of railroad cars” had been able to move food into the region. In New York City on February 22 and 23, there were poultry price demonstrations. In one week the price of poultry had risen from 20 or 22 cents per pound to as high as 32 cents per pound—a 45 percent increase. On February 25, 5,000 people “leaving a protest rally at Madison Square, marched upon the Waldorf-Astoria Hotel, demanding food.” Demonstrators also attacked wealthy motorists. One driver, “fearing injury at the hands of the mob, put in high speed and went pell mell through the crowded street,” injuring at least one hundred women and some children. In Philadelphia, food riots resulted in one man being shot by the police and an old woman being trampled by a mob, while furious mothers declared a school strike. In Cincinnati, community leaders called for a boycott of butcher shops. In Chicago, settlement workers reported acute suffering among the city’s poor. High food prices and fuel shortages gave rise to “[r]umors of foreign influence,” which prompted a Justice Department investigation. The investigation later found “no plot” in the food boycotts, only hungry people.[4] The rioting and protests in New York continued on March 1, which the socialist daily paper New York Call called the “worst rioting” yet. Nearly one hundred people were arrested as grocery stores across the Lower East Side were attacked. On March 3, butchers stabbed a baby and an old woman in two separate protest incidents. In an effort to quell the boycotts and alleviate hunger, authorities tried a variety of ways to bring food into the city. Some Progressives tried to shift the diets of poor and working-class Americans to nutritionally equivalent but cheaper and more readily available substitutes, but to the boycotting women this was offensive. “We don’t want their oleomargarine. I could buy butter once on my husband’s wages – I don’t see why I shouldn’t have the same to-day,” said Mrs. Ida Markowitz at a protest. Other women felt the same—“Even two months ago it wasn’t so hard as it is today.” Other Progressive reformers tried to get their wealthy friends to “subscribe” to their efforts to replace middlemen with themselves – to personally buy up produce and have it shipped into the city to sell at below market costs, with the assurance that subscribers would get their money back, of course.[5] The biggest blunder by wealthy Progressives was perhaps that of George Perkins, head of New York City’s Food Committee, who “sent 14,000 pounds of smelt into the city on motor trucks, [but] angry East Side shoppers ‘who suspected Wall Street and did not want smelts, anyhow, mauled the sellers and returned some of the fish to their native element through open manholes.’” Dr. Haven Emerson, head of the New York City Health Department, nearly provoked another riot on March 3 when he told 2,000 East Side residents “to use milk instead of eggs and rice rather than potatoes and not to intrude their European habits into the United States.” An editorial in the New York Call, pointed out that high use of cheaper substitutes was far more likely to simply drive up the prices of said substitutes as demand increased. Many suspected that suggested substitutes were not only a deflection of the larger high cost of living problem, but also covert (and not so covert) attempts by Yankee Progressives to Americanize and assimilate the food habits of immigrant communities.[6] In New York, the boycotts and riots eventually worked. Or so it seemed. In the weeks between February 20 and March 11, pushcarts disappeared from the streets, vendors “slashed prices to save their stocks from spoilage . . . Onion shipments accumulated unsold at wholesalers’ wharves.” By March 11, potato prices had fallen from eleven cents to six cents per pound. But by March 25, New York State Agriculture Commissioner Charles Wilson reported that meat, bread, and vegetables like potatoes were likely to remain scarce, owing to a poor potato and vegetable crop in 1916 and encroachment on cattle range lands in the west. Although prices were dropping from their mid-winter highs, the high cost of living and food price problems remained fundamentally unresolved. [7] [1] “Food Problem Real to East Side’s Poor,” New York Times, February 25, 1917. [2] Frieburger, “War Prosperity,” 226; Frank, “Housewives, Socialists,” 258-259. [3] Frank, “Housewives, Socialists,” 255-285. [4] Frieburger, “War Prosperity,” 223-229; Elaine F. Weiss, Fruits of Victory: The Woman’s Land Army of America in the Great War (Washington, D.C.: Potomac Books, 2008), 23; “No Plot in Food Riots,” New York Times, February 24, 1917. [5] Frieburger, “War Prosperity,” 228-238; As quoted in Frank, “Housewives, Socialists,” 262-263. [6] Frieburger, “War Prosperity,” 234-235. [7] Frank, “Housewives, Socialists,” 259; “Sees No Hope of Drop in Prices of Food,” New York Times, March 24, 1917. For the onion farmers, it was a different story. While their crops were rotting at warehouses, they were searching for alternatives to save the crop. From a different chapter in the book: One of the most popular topics of the OCFPB’s 1917 “Conservation Special” was the premise of grinding potato flour in the home and on the farm. Community dehydration plants and homemade kitchen driers were enthusiastically received, especially in the Pine Island, “black dirt” area where onion and potato farmers were hardest hit by boycotts and transportation issues.[1] Potato flour was being touted as a substitute for or additive to stretch wheat flour, which Herbert Hoover had asked housewives across the country to conserve through his “Wheatless Wednesdays” campaign. In her Erie Railroad Magazine article reporting on the “Conservation Special,” Gillian Bailey wrote, “That we brought encouragement and help to the large market growers is evident by the fact that we are expecting at least three commercial dryers to be run . . . and when these three huge machines are being run to their full capacity I shall feel that Orange county will be doing her bit.” [2] Indeed, there was a great deal of interest in installing community dehydrators all over Orange County. The mayor of Middletown, N.Y. was “so interested in the possibility of a local plant” that he coordinated with the Middletown Chamber of Commerce to discuss. Staff from a local farm belonging to the Department of Correction of New York City spoke with Mrs. Andrea about preserving produce like corn, beans, and tomatoes “until markets for them could be found.” Mrs. Andrea was the OCFPB’s at-large home economics expert who had published a book on food preservation through canning and later went on to publish another on dehydration and drying.[3] Individuals were also interested in dehydration. The OCFPB’s Mrs. M. C. Migel said that “a community dryer is to be installed on her estate at Monroe, N.Y., as an incentive to others. Mrs. H. D. Pulsifer, who owns the 700-acre Houghton farm, at Mountainville, N.Y., is another person who showed interest in the community dryer.” Port Jervis, too, showed a great deal of enthusiasm in the potential of a community dehydrating plant. In a letter to Mrs. Bailey about her impending magazine article, a representative from the Erie Railroad wrote congratulating her about the press coverage of the train, including this tidbit, “Port Jervis, you will note by reading the Union report, is deeply interested and its business men have taken up the question of a community dryer.”[4] Unfortunately for Gillian’s optimism, community dehydration plants did not take off in Orange County as planned. The Port Jervis Union recounted the decision, indicating that a large commercial dryer was too expensive. “After a long discussion, it was decided that Port Jervis and the adjacent farming territory was not large enough to support such a plant.” Indeed, although homemade dryers seemed popular and commercially made ones could be had for as “little” as five dollars, the big commercial dehydration plants proved out of reach for most communities. The narrow profits to be made on dehydrated vegetables just could not warrant the up-front expense. As the war wore on and agricultural production improved, the demand for dehydrated foodstuffs seemed to decline. Perhaps the length of time to dehydrate and the difficulty in reviving dehydrated vegetables, in particular, made the process less palatable to farm wives and individuals. Canning took less time, and the results were much easier to use – just heat and serve for most vegetables, and canned fruits could be eaten straight from the jar. The commercial market for dehydrated vegetables also did not seem particularly robust, and thus could not support the expense of large-scale dehydration.[5] [1] Bailey, “Waste Not, Want Not” Erie Railroad Magazine, 391; “Farmers Interested In Vegetable Drying,” Evening Telegram (New York), July 5, 1917, p. 4. The “black dirt” region of Orange County is a prehistoric peat bog where many a mastodon skeleton has been discovered. This land was sold to Bohemian and Polish immigrants by speculators in the 19th century who deemed it worthless, but the immigrants had experience with draining wetlands to make rich farmland. The topsoil in this region is still today up to 30 feet deep. Special horse shoes were developed to keep them from sinking as they plowed, and modern tractors must have dual tires and cannot be left in the fields overnight. [2] Gillian Webster Barr Bailey, “Waste Not, Want Not,” Erie Railroad Magazine 13, no. 7: 430. [3] “Preached Gospel of Dehydration to 7,000 Persons,” Herald (New York City), July 8, 1917. [4] Ibid.; Erie Railroad Company to Mrs. Bailey, July 9, 1917, Orange County Food Preservation Battalion Scrapbook 1917-1919, Archive, Museum Village, Monroe, NY. [5] “Chamber of Commerce Discussed Drying Plant – City and Community Not Large Enough To Support the Proposition,” Port Jervis Union, undated, Orange County Food Preservation Battalion Scrapbook 1917-1919, Archive, Museum Village, Monroe, NY. Of course, onion farming still happens in Pine Island and Chester and other black dirt towns, as mentioned in the Civil Eats piece. For more about the farming itself, check out this piece from the BBC. And, if you'd like to read the book chapters these excerpts are from, become a member of The Food Historian and you can read to your heart's content in the members-only section of the website. Join today or support us on Patreon. Okay folks, just 6 months after submitting and 9 months after receiving the invitation and book, my review of Capitalist Pigs is finally in print in the latest issue of Agricultural History - the journal of the Agricultural History Society. It's a pretty great issue, so I recommend you check out the few articles they have put up online. Alas, my review is not one of them, BUT! Being the rebel that I am, and seeing that I wrote this review for free (albeit in exchange for an advanced copy of the book, which was pretty cool), I'm going to do you a solid and post it here for you to read for yourself. For photographic proof, click through the images above! Capitalist Pigs: Pigs, Pork, and Power in America. By J.L. Anderson. Morgantown: West Virginia University Press, 2018. 300 pp., $34.99, paperback, ISBN 978-1-946684-73-8. “Capitalist pigs” is a term most frequently attributed to stereotypical Soviet protagonists describing Americans, or perhaps fat hogs in suits and top hats representing greedy businessmen in political cartoons. But in Capitalist Pigs: Pigs, Pork, and Power in America, J.L. Anderson puts a clever turn on the phrase as he explores the role of pigs and pork in America from the early Colonial period to the present. In Capitalist Pigs, Anderson argues that hogs have played a unique role in the development of the United States, and that the United States played a unique role in the development of the hog. “Americans maximized opportunities for the proliferation of the hog, even amid changing values and ideals about empire, agriculture, cities, and health.” (5). In particular, Anderson emphasizes that the story of the hog in America is one of excess, as farmers and marketers alike attempted to “transcend limits” on production. Capitalist Pigs covers the Colonial period to the present in the United States and is organized thematically rather than chronologically. Anderson covers such topics as free-range hogs and their influence on early settlements, pork consumption and its shifting role from frontier and working class food to re-branded “other white meat,” early industrialization of pork production and husbandry, including a discussion of hog cholera and enclosure, the role of the hog as garbage disposal, from our earliest urban areas to the industrialized present, and finally with a discussion of the modern industrialization of the hog, including changing its very physique to match modern consumer tastes and the controversial rise of confined animal feeding operations (CAFOs). Capitalist Pigs is well-researched and the broad chronology of the book provides a sweeping view of the influence of the hog on American culture and development throughout the centuries, giving needed context to historians of all stripes. Anderson is at his most compelling when he includes the voices of marginalized people and his sections on indigenous populations, enslaved people, and the Civil Rights movement are among his best. For urban and environmental historians, the discussion of the role of hogs in reshaping the landscape and the transition of urban spaces to exclude them, even as they continued to operate as waste disposal systems, will be of particular interest. Twentieth century historians, particularly agriculture historians, will be impressed by his discussion of the industrialization of hog production and marketing from the 1940s on. Anderson’s background as a public historian means his writing is clear, straightforward, and free of jargon and unnecessarily convoluted sentences. His writing style is engaging and would appeal to not only professional historians, but likely students and laypeople as well. Although Anderson’s writing style is clear, his main arguments are not. It seems as though Anderson could not quite decide whether to write Capitalist Pigs as a more technical agricultural history, or as a social history, and decided to split the difference. Anderson notes the influence of pigs in the institution of slavery, subsistence farms, and as a “mortgage lifter.” But the primary argument outlined in the introduction is focused instead on how Americans changed the pig. An interesting, if somewhat divergent take from the usual social history bent of most food histories, the argument is ultimately a weak one. Although Anderson discusses extensively in the latter half of the book how farmers industrialized and economized pork production and even changed the body shape of pigs to accommodate changing consumer tastes, he spends little time discussing the effects on the pigs themselves. Although breeding is mentioned frequently, the only mention of any particular breed in the entire book is about how heritage breeds have become more fashionable in modern nose-to-tail cuisine and sustainable agriculture (172-73), despite the fact that discussing the various breeds of pig throughout the book would have lent weight to later industrial changes and changing consumer tastes. He also skirts around the effects of industrialization on the hogs themselves - only in a photo caption does he mention accusations of cruelty in hog confinement operations (201). In addition, although the title and discussions in several chapters imply that hogs played a significant role in building America’s capitalist system, Anderson does not quite make those connections clear throughout the chapters, and discussion of meat-packing beyond the 1850s is conspicuously absent. Given the influential role of America’s meat-packers in the late nineteenth century in both industrial capitalism and union history, this is a curious oversight. Although Capitalist Pigs doesn’t quite live up to the premise of its fantastic title, it is a worthy combination of agriculture and food history - combining the history of industrial technology and consumer uses of hogs throughout the entirety of American history. Food and agriculture historians in particular will find much of use, but American social, environmental, rural, urban, and Civil War historians will also enjoy the read. If you enjoyed this book review, consider becoming a member of The Food Historian! You can join online here, or you can join us on Patreon. Members get access to members-only sections of this website, special updates, plus discounts on future events and classes. And you'll help support free content like this for everyone. Join today!

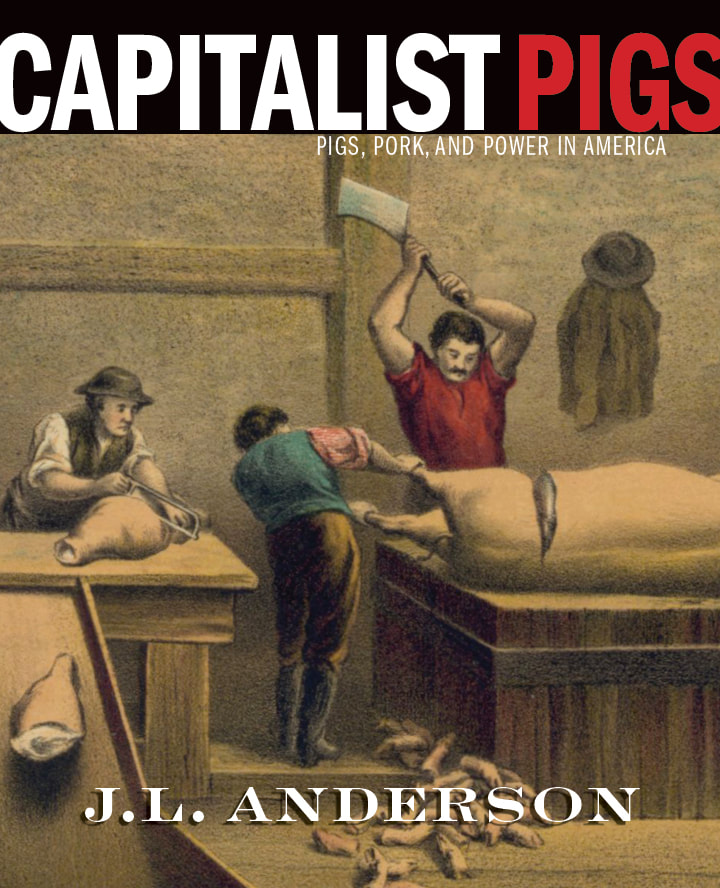

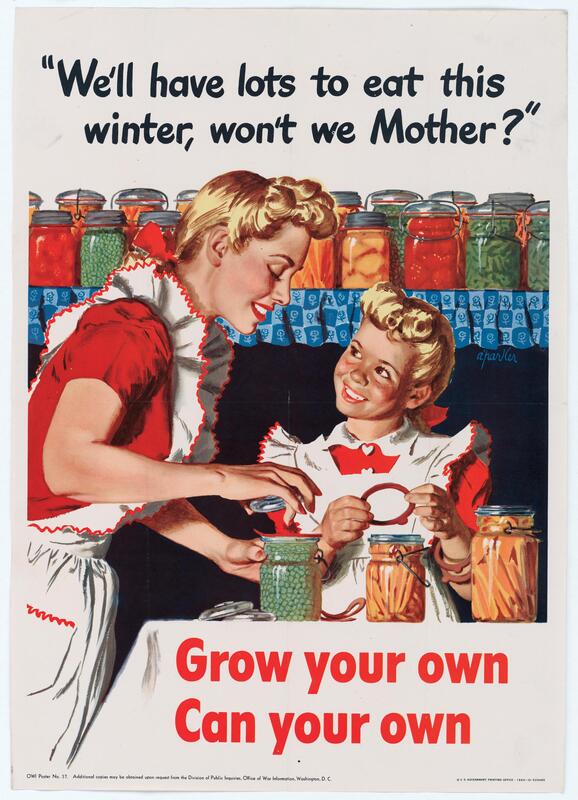

Remember last week's foray into home canning during the First World War? Victory garden and canning efforts returned for World War II. Unlike the First World War, rationing during the Second World War was mandatory and regulated by the Federal government. Because purchased foods were restricted, Americans were strongly encouraged to keep victory gardens. And because commercially canned goods were needed for shipment overseas, ordinary people were encouraged to preserve the fruits of their victory gardens at home. Propaganda posters like the one above made great efforts to frame the drudgery of home food preservation in wartime terms. Housewives were encouraged to "can all you can," while the poster cheerily chirped, "It's a real war job!" presumably to put the kibosh on all the naysayers who insisted otherwise. In addition to being a "real war job," canning efforts were framed in a number of ways. In the above poster, a proud housewife, with perfect victory curls, a ruffly floral apron, and an armful of jars (beets, green beans, and tomatoes from the looks of it, with more beets, raspberries, and corn below) indicates that not only is she preserving food for her own family, she's also "fighting famine." By "canning food at home," she's freeing up commercially canned goods to be sent overseas to help the civilians of war-torn countries stave off famine. In this final poster, a cherubic little girl, in a dress and frilly apron that matches her mother's outfit, helps place the rubber rings on wire bail jars of carrots and peas, preparing them for canning. Hopefully in a pressure canner, since low-acid vegetables like peas and carrots need to be canned at higher than 212 degrees Fahrenheit (boiling point) in order to be safe from botulism. The girl says, "We'll have lots to eat this winter, won't we Mother?" implying that a well-stocked home pantry like the one in the background provided security against future food shortages or tightened rations. Both the promotion of home canning and the implementation of wartime rationing reflected an agricultural system not designed to provide massive surpluses. Coming out of the Dust Bowl era of the Great Depression, agricultural practices in the United States had improved, but most of the food produced at home was still consumed at home. Cuts had to be made domestically in order to free up the food supply for shipment overseas. In the decades since the Second World War, American agriculture has been transformed, both by the leftovers of chemical warfare and explosives production (pesticides and chemical fertilizers come to mind) but also by the mindset that producing unlimited food brings global security. Improvements to global shipping have meant that it is now as easy (or easier, and certainly cheaper) to get garlic from China as it is from the farmer down the street. Or apples from New Zealand or Peru than from a local orchard. Home preservation and home kitchen gardens are certainly no longer necessary, given the world of food at our fingertips at both grocery stores and online. With home food preservation no longer necessary, canning and gardening have taken on a sheen of delight. For many people, it is preferable to can your own jam from berries you picked yourself, rather than buy from the store. But I think the romance that hangs around home food preservation today belies the struggles of the past - when poorly preserved foods or inadequate supplies meant illness and hunger. When a poor harvest didn't just mean higher prices at the grocery store, but threatened real starvation. it's important to remember that food preservation during World War II played an important role in both nutrition and improving the everyday diet of Americans. But it's also important to recognize the amount of labor spent on both victory gardens and home canning at a time when American labor was already stretched thin in the war effort as factories ramped up production and speed, women took on the work of fighting men, and everyone hustled to get things done with fewer people and fewer resources. The size of the United States meant that we never quite had the same threats of deprivation as the U.K., which is perhaps why they are so much better at telling their WWII home front stories than Americans are. The size and scope of our continent meant we could be self-sustaining and still provide food abroad, whereas the United Kingdom had to learn how to do without regular food shipments to its tiny island. So the next time you do some home canning, whether from necessity or for fun, I hope you remember the people of the past. If you enjoyed this installment of #WorldWarWednesdays, consider becoming a Food Historian patron on Patreon! Members get access to patrons-only content, to vote for new blog post and podcast topics, get access to my food library, research advice, and more!

"Henry Browne, Farmer" - film produced in 1942 by the United States Department of Agriculture, digitized by the Prelinger Archive of archive.org.

Nominated for an Academy Award for Best Documentary in 1943, "Henry Browne, Farmer" was a propaganda film produced by the United States Department of Agriculture in 1942. It is also one of the few major propaganda pieces (there were many thousand smaller efforts) directed specifically at African Americans.

In it are many hallmarks of post-Reconstruction life for African Americans in a white supremacist country. References to using only mules instead of a tractor. Eating cornbread and fatback last year, but having a cow and chickens, meaning milk and eggs for breakfast this year. Specific programs are not mentioned, but it is clear that by cooperating with the federal government to grow peanuts, that the Browne family is also participating in other endeavors, like raising chickens and keeping a victory garden. Children, in particular, were encouraged in rural areas to raise chickens (like "sister" in the film), dairy cows ("brother's job), and help with Victory gardening and around the farm. Similar programs around pig clubs and tomato canning clubs were in use during World War I as well. The film, which sadly does not record any of their voices (just the voiceover), ends with the family going to visit their oldest son, a member of the Tuskegee Airmen. This is both a call to service for all Americans and "proof" that the family is just as patriotic as any white American. This film was groundbreaking in that it put African American farmers on equal footing with other Americans joining the war effort. It emphasized Henry Browne's good agricultural techniques, like saving burlap bags instead of throwing them away, and greasing and covering farm equipment, which meant that it was likely to "last the duration" in a time when steel was in short supply and new farm equipment was likely to be expensive or impossible to get. It also did not have too many hallmarks of racism, which is surprising for the time. Unlike during the First World War, the United States propaganda machine during WWII was broadening the definition of who "counted" as an American, to give a little more credence to the idea that Americans were fighting to preserve democracy and freedom abroad. Unfortunately, the message was ultimately still hypocritical as many Black people in the south were being terrorized by Jim Crow laws, police, incarceration, and the Ku Klux Klan. However, a Civil Rights movement, which had been borne out of the returning Black soldiers of World War I and which broadened during World War II, was underway, as African Americans sought to free themselves from terror, discrimination, and disenfranchisement. World War II would mark the end of an era for many Black farmers in the rural south. Industrial work in northern and coastal cities, long a draw for those escaping sharecropping and other slave-like conditions in the South, became a bigger draw during the total war mobilization of the nation's industries. Thanks to protests from African American unions like the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters and the NAACP, Franklin D. Roosevelt was forced to create the Fair Employment Practices Committee in 1941, which banned discriminatory hiring in federal agencies and for companies employed in defense work, which for the first time allowed many African Americans to receive fair wages and work conditions for the first time. In addition to this draw off of the farms, there is evidence that the USDA engaged in discriminatory practices which helped drive African American farmers off of their land and caused nearly 90% of black farmers to lose their land in the years following World War II. Pete Daniel's book Dispossession: Discrimination against African American Farmers in the Age of Civil Rights explores this topic in more detail, and in fact, until very recently, the USDA continued their discriminatory practices. In all, "Henry Browne, Farmer" is one of the better propaganda films to come out of the Second World War. With quiet assurance and emphasis on the important work of ordinary Americans to do their part, it lacks the overly patronizing tone and bombast of other "documentaries" from the period. It's one of my favorites, and I hope you enjoy it as well. If you enjoyed this installment of #WorldWarWednesdays, consider becoming a Food Historian patron on Patreon! Members get to vote for new blog post and podcast topics, get access to my food library, research advice, and more! |

AuthorSarah Wassberg Johnson has an MA in Public History from the University at Albany and studies early 20th century food history. Archives

July 2024

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed