|

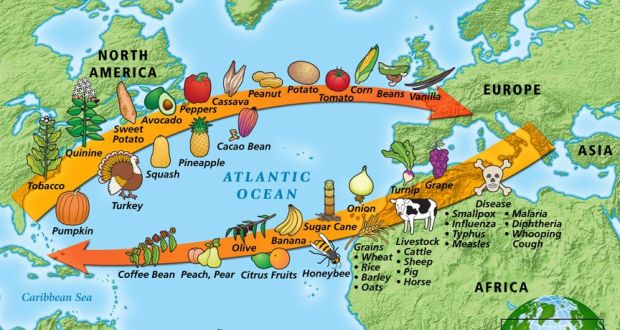

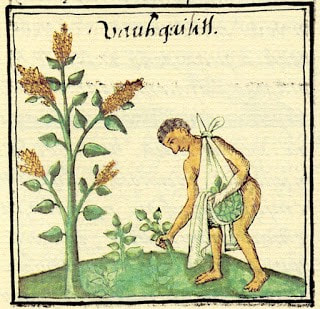

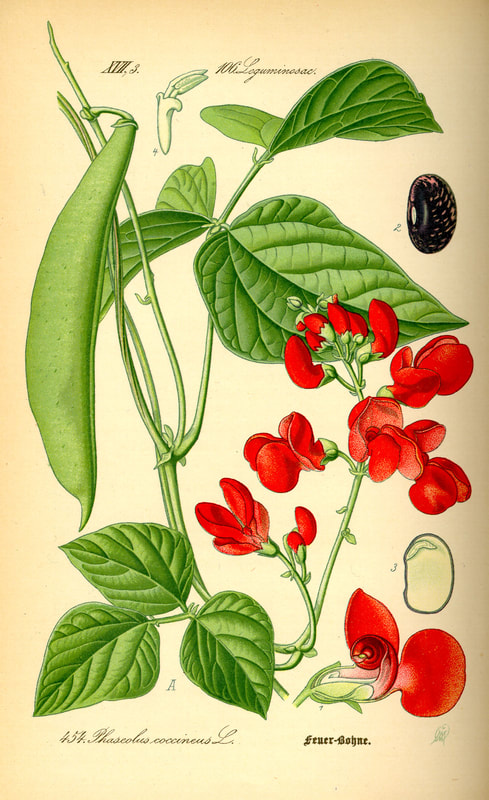

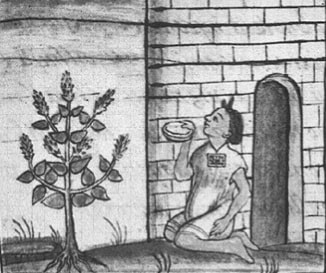

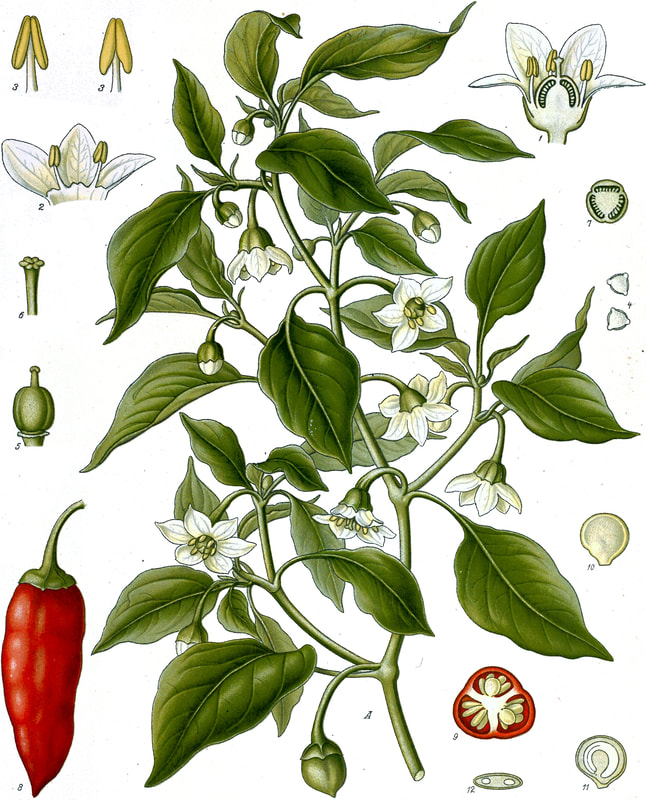

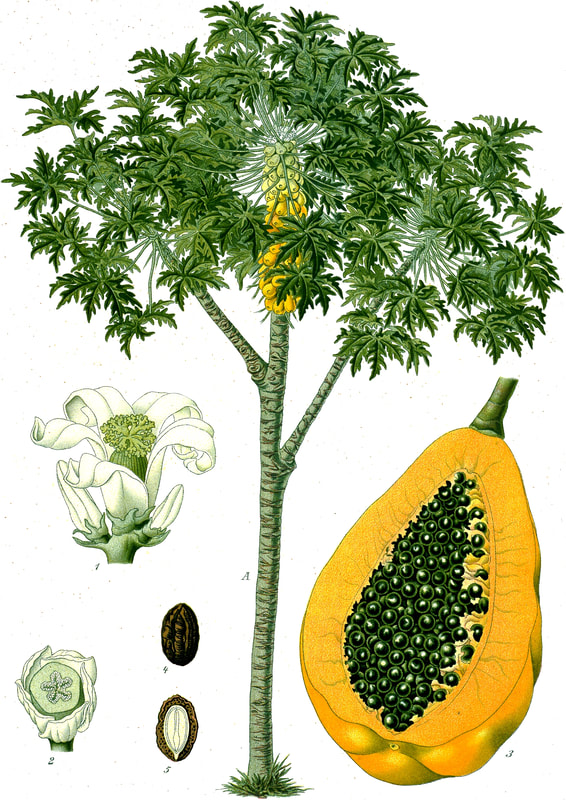

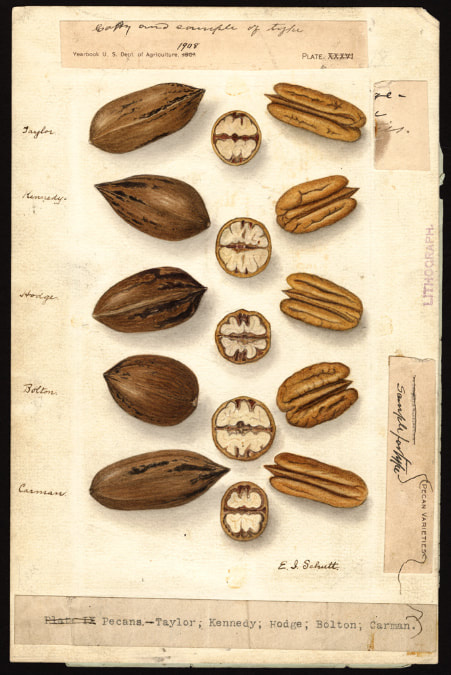

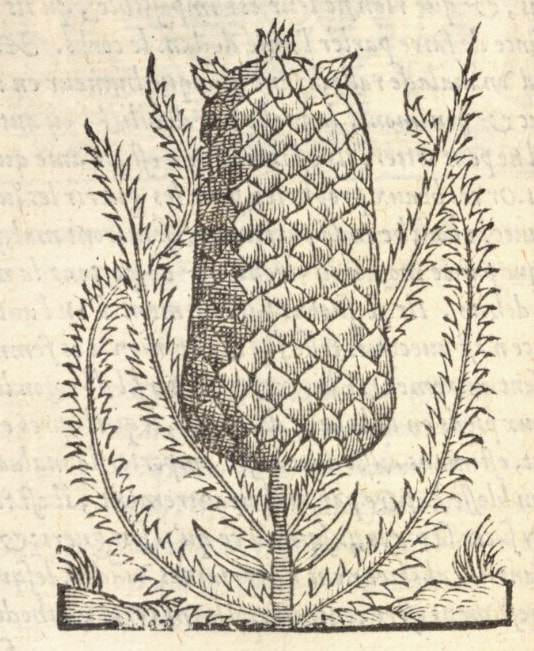

Today is Indigenous Peoples' Day. What, you thought it was Columbus Day? Well, for some people who don't know any better it still is, but Columbus was a pretty terrible person, driven by greed, and he didn't "discover" anything. Instead, he did things like sell 9 year old Taino girls into sex slavery, cut off children's hands if they didn't meet gold quotas, and generally committed genocide and slavery against every non-white person he met. He almost completely wiped out the Arawak-speaking peoples of the Caribbean, including the Lucayan people of the Bahamas and especially the Taino people of Hispaniola (present day Haiti and Dominican Republic). But as with most genocides, they're never 100% successful, and people throughout the Caribbean are descended from Taino people. One thing Columbus did lend his name to is a term called "The Columbian Exchange." The term was coined in the 1970s by historian Alfred W. Crosby, who studied the impacts of geography and biology on history, specifically the relationship between Europe and the rest of the world. Because Columbus was the first European to bring back many of the plants now used across the world, the exchange is named after him. Essentially, Irish potatoes, Italian tomato sauce, Swiss chocolate, Thai chilis, and a whole host of other important international foods are not actually from any of those places. They are ALL indigenous to North and South America and did not exist outside those continents prior to 1492. I'm going to catalog Indigenous American foodways in a minute, but first I want to emphasize how important it is to recognize that all of these foods are a result of Indigenous agricultural innovation. There is a tendency among many White folks to assume that these foods were just growing "wild" - and while that may be the case with some fruits, the vast majority were cultivated by Indigenous people, often in brilliant and surprising ways. And if you'd like to skip the list and go straight to figuring out where you can buy Indigenous foods and support Indigenous growers, harvesters, and producers, a good starting place is the list created by the Toasted Sister podcast. It's not comprehensive, but it's a great start. You can also check out this directory of certified American Indian Foods producers by the Intertribal Agricultural Council. You can even search by state! A small disclaimer - this is obviously not a complete list of Indigenous foods - I thought I would list the most influential foods globally and in the modern American diet. But I encourage you to use the magic of the internet to see what other foods you can find Indigenous to the area you live. And one final note - while it is important to preserve Indigenous foods and seeds, it's equally important to support the Indigenous people working to preserver them, like the Indigenous Seed Keepers Network. So while groups like Seed Savers Exchange are great, I encourage everyone to seek out Indigenous-owned and Indigenous-led companies and groups when choosing who to support. AmaranthWhere I grew up on the Northern Plains, in Lakota territory, one species amaranth is often known as "pigweed," and is considered a noxious weed by farmers. But Indigenous people know it as an important grain crop. Developed by the Aztec, amaranth was banned by the Spanish. The leaves of amaranth are also edible and some varieties are known as "callaloo," an important green vegetable for enslaved African peoples throughout the Caribbean and southern United States. If you're a gardener, "love-lies-bleeding" is a decorative variety of amaranth. There are dozens of varieties, but amaranth grains are often available for purchase from specialty stores and online. AvocadoAvocadoes, modern purview of hipsters, are actually an ancient fruit developed near Puebla, Mexico nearly 10,000 years ago (seriously, the world owes so much to Mexico in terms of agricultural innovation). The Indigenous residents of Puebla began cultivating the tree as much as 5,000 years ago. Modern-day avocadoes come in a whole host of varieties, but residents of the U.S. are most familiar with the Hass variety. Introduced to the American Southwest in the 1830s, avocado consumption in the United States didn't really take off nationally until the 1930s, influenced by California cuisine and used primarily in salads. Look in old cookbooks for references to "alligator pears," so named because of their bumpy green skin and pear shape. BeansBeans, especially climbing pole beans like the scarlet runner bean, are an important component of the Three Sisters style of agriculture, in which pumpkins or squash, corn, and beans are grown in concert with each other. The corn provides the stalk for beans to climb, the beans fix nitrogen in the soil for the corn and squash, and the broad leaves of the squash shade the ground, helping to prevent competing plants from growing and keeping the soil moist. Although some varieties of legumes did exist in Europe prior to the Columbian Exchange, notably chickpeas, peas, lentils, and broad beans, the introduction of the wide variety of cultivated Indigenous beans to Europe, especially kidney beans, including what would become the famous Italian cannelini. Black beans, pinto beans, and pink beans are other Indigenous varieties. Blueberries Image of the Weymouth variety of blueberries (scientific name: Vaccinium corymbosum), with this specimen originating in New Jersey, United States. Source: U.S. Department of Agriculture Pomological Watercolor Collection. Rare and Special Collections, National Agricultural Library, Beltsville, MD 20705, 1940. Lowbush blueberries (often marketed in grocery stores as "wild" blueberries) are native to North America, as other other blueberry-like fruits including huckleberries and juneberries (also known as serviceberries). Although these plants grew wild, blueberry barrens and other stands were often maintained by Indigenous peoples. Dried blueberry and cracked corn mush may have been served at the First Thanksgiving. Early European observers misnamed them "bilberries," after a relative native to Britain. In the early 20th century, highbush blueberries were cultivated from Indigenous blueberries in New Jersey. Highbush blueberries are bigger and therefore easier to harvest and ship than lowbush blueberries and are most often what you'll find in grocery stores today. CashewMost people probably associate cashews with Southeast Asia and Indian cuisines. But cashews are actually native to Brazil. The word "cashew" is a corruption of the word "acaju," which is Tupi for "nut." The Tupi people (of which there are dozens of sub-tribes) were who the Portuguese encountered when they first arrived there in the early 1500s. It was the Portuguese who brought the cashew to Goa, India in the late 1500s, where it thrived. Today, most commercially produced cashews are grown in India. ChiaMaybe you've noticed the trend for chia puddings these days. Or perhaps you're old enough to remember the Chia Pet craze of the 1980s. But the origins of chia are much older than you might suppose. Native to Central America, chia is thought to have been cultivated by the Aztecs as much as 3,500 years ago. An important staple crop throughout Mesoamerica, it was likely also used for religious purposes and may have been banned by Spanish colonizers for that reason. Thankfully, it survived. Chilis & PeppersChili peppers - from which all modern capsicums are derived, including bell peppers - were cultivated in Mexico as early as 6,000 years ago. Self-pollinating, chilis quickly spread throughout Mexico and Central and South America. Known in many countries by their cultivar name - capsicum - in the United States we call them "peppers" because Columbus and other Europeans associated them with the heat they had previously only known from black pepper. Like cashews, chili peppers were brought to Southeast Asia by Portuguese traders, where they quickly took hold as an essential part of many Asian cuisines. In the United States, New Mexico is best known for its production of chili peppers and its chili-eating heritage. Chilis are an essential ingredient in salsa, and Indigenous Mexican peoples use all different varieties (not just jalapenos and habaneros) for different levels of heat and flavor. ChocolateToday, chocolate is most often associated with Switzerland, Germany, and France. But its origins are ancient and date to Mesoamerica. The oldest references are for the Olmec peoples of central Mexico, who used it in religious ceremonies. But it was also used by the Maya and Aztec peoples, who both used cocoa beans as currency and used chocolate beverages in daily life and religious ceremonies. Although the origin of cacao plants is contested, they appear to have been common in Central America and actively cultivated as early as 5,300 years ago. Chocolate's chemical signature is often tracked as part of archaeological digs, and recent finds have suggested that its use and cultivation are earlier and more widespread than previously known. When it was introduced to Europe, Europeans treated it much like they did another dark, bitter beverage - coffee - by adding cream and sugar to it and drinking it for breakfast. By the 18th century, mechanization and slavery had made chocolate affordable to the middle classes. But it wasn't until the 19th century that chocolate bars, mixed with vanilla, sugar, dairy solids, and cocoa butter, came into widespread use. Corn (Maize)For most Americans, corn is hybridized sweet corn, popcorn, and maybe yellow or white cornmeal (or grits). But corn comes in thousands of different varieties and can be processed in hundreds of different ways. Did you know, for instance, that different varieties of corn - popcorn, dent, flint, flour, etc. - were cultivated for different uses? And that most corn can be eaten at all stages of development? And that "sweet" corn was originally just eating immature "green" corn before the sugars had turned to starch? Indigenous cooks also developed nixtamalization - a process whereby corn is soaked in wood ashes and water (i.e. lye) to de-hull and soften the corn. Nixtamalization also has the important additional benefit of releasing the niacin (Vitamin B3) from the corn so that it can be processed by the body. Niacin deficiency, also known as pellagra, plagued 19th and early 20th century White Americans, who did not know how to process the corn properly. Corn was developed from a grass native to south central Mexico called teosinte - which is still used today in Mexico as a fodder for livestock. As cultivated varieties spread throughout North America, they took on different characteristics as they cross-pollinated with other varieties and native species of teosinte. Corn is wind pollinated, meaning that it cross-breeds easily. Today, corn's global dominance is almost entirely related to its role as livestock feed, especially with beef. Sadly, beef cattle are not well suited to being raised on corn, and "corn fed beef," which is designed to put on a lot of fat for your "well-marbled" steak, is actually extremely destructive to bovine digestive systems. Not to mention unhealthy for humans, too. American agricultural subsidies for corn, which allow food processors to purchase it for less than it costs farmers to produce, have also allowed the proliferation of its use as an industrial food, notably corn syrup, but corn is now in almost everything we eat. And not in a good way. If you want to help Indigenous producers, buy Indigenous-grown Indigenous corn products. Here in New York, you can buy Iroquois White Corn. Don't feel like eating corn but want to help? Support Indigenous seedkeeper groups. Can't find one in your area? Donate to the Indigenous Seedkeeper's Network. CranberriesToday, cranberries are most often associated with Thanksgiving and New England, but cranberries are native to the northeast of North America and were used often by Indigenous peoples in those areas. Although a variety of cranberry is native to the bogs of Britain, and the Scandinavian lingonberries are a relative, the vast majority of modern cranberry consumption is based on species native to the U.S. and Canada. Maple Syrup & SugarMaple Syrup is one of the few sweeteners native to North America (honeybees, sugar cane, sorghum, and sugar beets are all imported). First used by Indigenous peoples in the Northeast, it is unclear which tribes first started use of maple sap as a sweetener. One Haudenosaunee/Iroquois legend indicates that the people first observed red squirrels cutting into the bark of maple trees and returning to drink the sap that flowed out. This has since been confirmed by scientific observation of squirrel behavior. Maple syrup and sugar was made either by freezing the water out of the sap, or by boiling with heated rocks. European colonists were quick to adopt maple sugaring as an important source of late winter calories and shelf-stable year-round sweetener. Although for some reason in the United States maple products are associated with fall, maple sugaring time is usually in March, when daytime temperatures rise above freezing, and fall below freezing at night - perfect conditions for optimum sap production. PapayaThe native range of the papaya is from southern Mexico to northern South America, although it has been naturalized throughout the Caribbean and the Gulf of Mexico. With a quick maturity - some papaya can produce fruit after just one year - Europeans spread the plant to other tropical regions around the world where it is widely used in many different stages of ripeness, both cooked and raw. PeanutsThe archaeological record of peanut cultivation is not clear, but it is clear that it was present in Brazil and Central America in the 16th century when European explorers arrived in South America. The peanut is not actually a nut - it is a legume and more closely related to beans than, say, pecans. But its culinary importance grew once it was imported by Europeans to Africa and Asia. The peanut actually came to North America by way of enslaved Africans, who carried it with them as they were stolen from their homelands. The peanut was largely regarded as animal fodder by Europeans, and used in subsistence farming by enslaved Africans and African-Americans in the U.S. In the late 19th century, a number of people, including John Harvey Kellogg and Heinz, were filing patents for peanut-butter-like substances. Ironically, George Washington Carver, African-American plant scientist and the man most associated with peanut butter, didn't actually invent it. Today, about the only people who don't enjoy peanuts much are Europeans, which is ironic given their role in spreading them globally. PecanNative to North America, the pecan is one of my favorite nuts. Its native range ran from New England to Mexico and was widely used by Indigenous peoples. The word "pecan" likely comes from a 16th century European corruption of the Algonquian word "pacane," describing nuts that required stones to crack. Hickory nuts (also known as butternuts) and black walnuts are in the same family as pecans. PineappleAlthough most Americans associate pineapples with Hawaii, they are actually native to the Paraguay River basin, which stretches between modern-day Brazil, Bolivia, Paraguay, and Argentina. Pineapples were cultivated by the Maya and Aztecs and Europeans first encountered them in the 15th century. Named the "pine apple" because of its resemblance to a pine cone and its status as a fruit, Europeans were able to grow some pineapples in greenhouses. In the 18th century, the pineapple was a symbol of hospitality and wealth and were much smaller than modern-day cultivars. Pineapple plantations were first installed by White Americans in Hawaii in the 1880s. James Dole made his fortune with pineapple plantations, processing, and canning innovations, which introduced the pineapple to ordinary Americans across the country. PotatoesWhat would Europe be without the potato? And yet, this starchy tuber, which spread throughout the Andes mountains prior to European contact, is originally from the border of modern-day Peru and Bolivia and dates back as far as 8,000 years ago. Cultivated from the wild tuber by Indigenous agriculturalists, over 5,000 varieties now exist. Potatoes were the staple crop of the Inca, who built their empire on it. Andean Indigenous peoples used it in all the usual ways, but also pioneered a special preservation technique called chuño, whereby the potatoes were frozen and dried in a way that made them very light and allowed them to keep for years. Chuño was usually prepared as part of a stew and was an important cash crop for Indigenous farmers. Prior to its introduction to Europe, most of the poorer classes relied on turnips and rutabaga for starchy bulk calories. But the potato was not only more palatable, it was more prolific, easier to grow, and it kept longer in storage. The shift to potatoes throughout Northern Europe in particular meant that the advent of potato blight in the mid-19th century, particularly in subjugated Ireland, started a mass migration of Europe's poor to the nations which had fed them so well for so long. QuinoaAlso native to the Andes and Peru, quinoa (pronounced "keen-wah"), is a member of the amaranth family. Used as a cereal crop by the Inca and other Indigenous peoples in the Andes mountains, quinoa has been in cultivation for as many as 5,000 years. When the Spanish arrived, determined to stamp out Incan culture, quinoa almost disappeared, but it persisted. Its "discovery" by White Americans interested in "superfoods," the price of this essential Indigenous grain actually skyrocketed. Whether or not this is good for Indigenous farmers is a matter of some debate, but when in doubt, be sure to buy from Indigenous producers. Squash & PumpkinAlong with corn and beans, squash make up the famous "Three Sisters" of Indigenous foodways. One of the oldest cultivated crops of the Americas, dating back as many as 10,000 years ago (before maize and beans), squashes are native to the Andes and Mesoamerica and wild varieties actually predate human inhabitation on the continents. Their cultivation was widespread throughout North and South America prior to European contact. All global varieties of squash, including pumpkins, zucchini, and decorative gourds, originated in the Americas. The word "squash" is an English corruption of the Narragansett word "askutasquash" meaning "a green thing eaten raw." Today, pumpkins (a word for a particular kind of large, round, orange squash that doesn't actually have an official classification) are mostly associated with Thanksgiving and New England foodways, although in the 19th century they were also stereotypically associated with slavery. They were one of the Indigenous foods featured in the first "American" cookbook, published by Amelia Simmons in 1796. SunflowerSunflowers are also native to North America, thought to have been cultivated near present-day Arizona and New Mexico around 3000 BC. Cultivated for their oily seeds and tuberous roots (also known as sunchokes or "Jerusalem artichokes"), sunflowers were also sometimes used as dyes. Although they were an important crop for Indigenous peoples, they were not in widespread use by European-Americans until their popularization in 19th century Russia, where they had been imported. Today, North and South Dakota are the biggest producers of sunflowers in the US and sunflower seeds, "sunbutter" and sunflower oil are popular modern uses. Not so much with the "sunchoke," although the tubers are regaining some popularity. Sweet PotatoSweet potatoes are native to Central America. Although called "potatoes" and sometimes "yams," they are not related to either plant. Sweet potatoes are more closely related to morning glory and bindweed. Sweet potatoes were spread across the Pacific nearly 400 years before Columbus by Polynesians, who brought the vine back with them. It was the Spanish and the Portuguese, however, who spread the sweet potato to the Philippines and Japan, respectively. The Spanish also brought the sweet potato to West Africa, where it was adopted, but not without some derision as its taste. The yam is native to Africa, which is likely why so many Americans, especially African-Americans, call sweet potatoes "yams." TomatoWhich is more authentic? Italian tomato sauce, or Mexican salsa? Hate to break it to you, but the Mexicans have the ayes on this one. Wild tomatoes are native to Western Mexico and were originally tiny, sour, and hard. Careful cultivation by Indigenous people led to thousands of more edible varieties, including husk tomatoes ranging from tomatillos to ground cherries. In Nahuatl (the Aztec language), "tomatl" was used to reference green tomatoes like tomatillos, and "xitomatl" was used for red varieties. The Spanish translated it as "tomate" and hence the term "tomato." When brought back to Europe, the bright red fruits were originally identified as a type of eggplant (both are members of the nightshade family), it garnered the nickname "love apple," and was originally considered poisonous. Although it was cultivated as a decorative plant, it was not in widespread use in Europe until the mid-18th century. It's widespread adoption in Italy was likely connected to nationalist sentiments in the 19th century and its association with the color red in the flag of Italian unification. In the United States, Thomas Jefferson may have helped popularize the tomato outside of the American southwest. And his relative by marriage, Mary Randolph, featured tomatoes in her Virginia Housewife cookbook, published in 1824. By the end of the 19th century, tomatoes became a popular American preserve, providing color, acidity, and sweetness to the typical American table. TurkeyIndigenous to North America, turkeys have been consumed by Indigenous peoples for centuries. Turkeys were domesticated in Mesoamerica as early as 800 BC. The Spanish brought back domesticated Aztec turkeys to Europe, where they quickly joined the European game bird lexicon. Associated with Christmas in Britain as early as the 17th century, the British Christmas goose persisted until the 20th century. In the United States, turkey is most commonly associated with Thanksgiving, although it is also often consumed at Christmas. Turkeys are one of the only indigenous American meat animals widely adopted in Europe and elsewhere. The name "Turkey" is likely associated with how Europeans were first introduced to turkeys - either through trade with the Middle East, or in association with guinea fowl as a game bird, introduced via Turkey. Domesticated turkeys are thought to have been descendants of Aztec domesticated birds reintroduced to North America via Europe. The turkeys purportedly eaten at the First Thanksgiving would have almost certainly been wild varieties, however. A shift to large scale commercial poultry production in the early 20th century has helped introduce turkey into the American diet through things like sliced deli turkey. The virtual disappearance of wild turkeys from New England due to deforestation meant that they had to be reintroduced to New England, an effort that began in the 1960s. VanillaVanilla is an orchid native to the Caribbean and south Central America. Cultivated by pre-Columbian Maya people, it was widely adopted by subsequent Indigenous peoples, including the Aztecs, who added it as a flavoring agent to their chocolate beverages. Attempts to cultivate vanilla in Europe were unsuccessful, largely because vanilla is naturally pollinated only by a native species of bee. An boy named Edmond Albius, enslaved on the Island of Reunion, pioneered a hand pollination technique that allowed vanilla to spread across the globe, including to the islands of Tahiti and Madagascar. Wild RiceWild rice, known in Anishinaabe/Ojibwe as "manoomin," is, indeed, a wild rice. Growing in marshy lakes, truely wild rice is harvested by hand from the wild. Wild rice is central to Anishinaabe culture, and one legend indicates that Ojibwe people emigrated from the Atlantic coast to the "place where food grows on the water." Although Northern wild rice is the most common, other two other varieties are native to North America - one in Florida and one in Texas. Suggestions to grow wild rice commercially were suggested as early as the mid-19th century, but it was not attempted on any scale until the 1950s. Commercially cultivated "wild" rice is now a great source of controversy, as is the genetic modification of wild rice. Opponents argue that commercial wild rice conflicts with Indigenous food sovereignty and treaty rights. True wild rice can also be endangered by relaxed water pollution standards, oil pipelines, and more. Indigenous people were rarely if ever involved in the research and are not beneficiaries of commercial varieties. For reasons of taste and to support Indigenous tribes and businesses, I strongly recommend that you source your wild rice from Indigenous producers. ConclusionPhew! That is a LOT of influential foods developed by Indigenous Americans. I hope you learned something with this catalog - I know I did. And I hope you'll support Indigenous food producers by purchasing direct whenever you can. Thanks to the magic of the internet, that's now possible more than ever. And for those of you interested, I'm planning a couple more posts (and a few talks) about the influence of pumpkins, corn, wild rice, and more. So stay tuned! What's your favorite Indigenous American food? The Food Historian blog is supported by patrons on Patreon! If you found this article interesting, useful, and/or thought-provoking, join us for awesome members-only content like free digitized cookbooks from my personal collection, e-newsletter, and even snail mail from time to time!

1 Comment

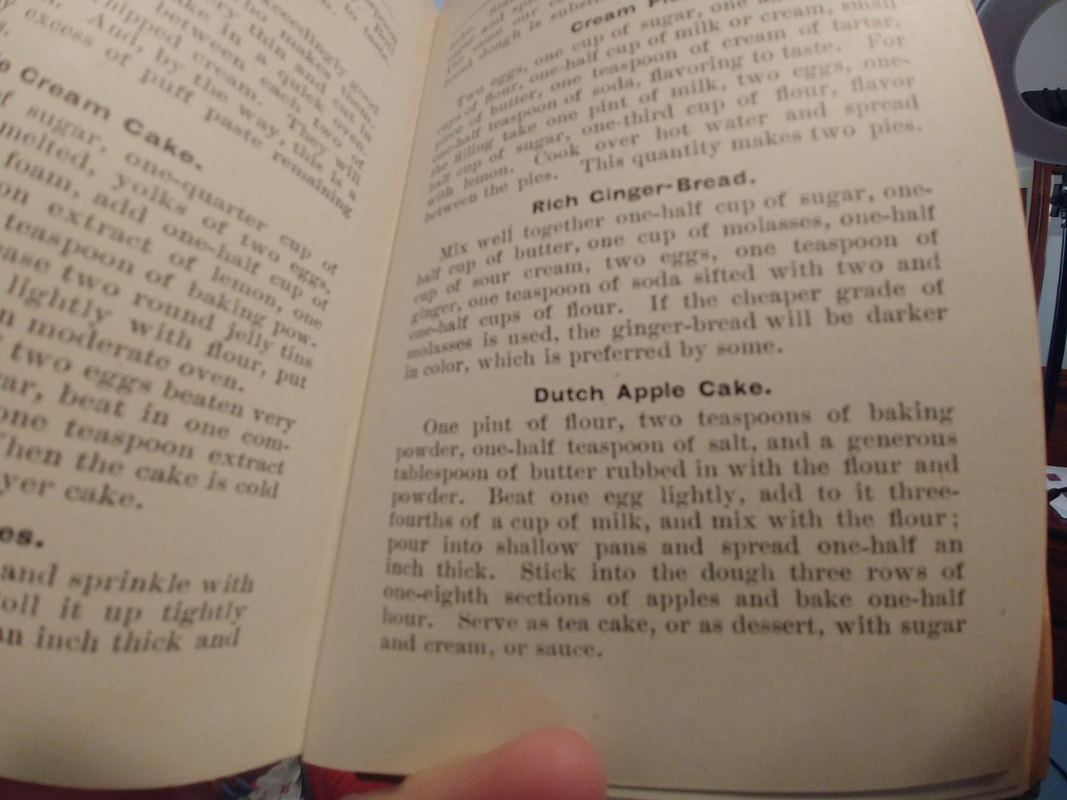

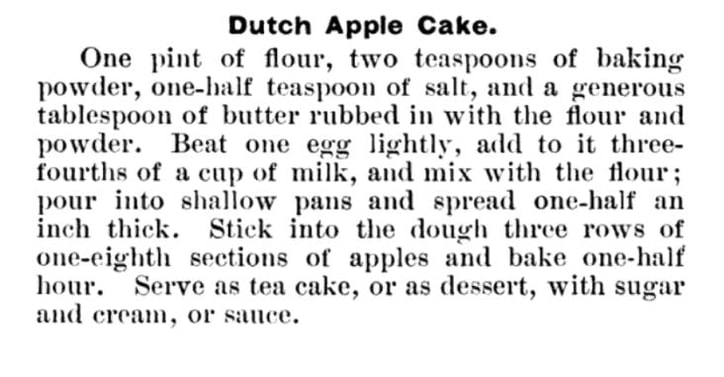

Hood's Practical Cook's Book from 1897 is one of my favorite 19th century cookbooks in my collection. It's really quite small and could easily fit in an apron pocket. My copy has the original dust jacket, which is nice. Published by C.I. Hood & Co., a Victorian patent medicine company, the cookbook is interspersed with advertisements for Hood's products, especially their famous sarsaparilla extract. I made the very successful Buttermilk Cake from this cookbook previously, and I'd been wanting to make Dutch Apple Cake for a while. Touted as a "tea cake," it was essentially a biscuit with sliced apples stuck in the dough. We've been trying to cut back on sweets, and this recipe has absolutely no sugar in it - neither for the biscuit nor on the apples, so it seemed like a perfect dessert. I also made it for our 3 year wedding anniversary. Normally we go away someplace fun, but obviously not this year, so I made my favorite roasted vegetable French lentil bowls and we had this for dessert. Dutch Apple Cake Recipe (1897)The original recipe reads: "One pint of flour, two teaspoons of baking powder, one-half teaspoon of salt, and a generous tablespoon of butter rubbed in with the flour and powder. Beat one egg lightly, add it to three-fourths of a cup of milk, and mix with the flour; pour into shallow pans and spread one-half an inch thick. Stick into the touch three rows of one-eighth sections of apples and bake one-half hour. Serve as a tea cake, or as dessert, with sugar and cream, or sauce." Here's how I translated the recipe: 2 cups flour 2 teaspoons baking powder 1/2 teaspoon salt 1 1/2 tablespoons butter 1 large egg 3/4 cup whole milk 3 smallish apples (I used Gingergold - a sweet, slightly mealy, early apple) Combine flour, baking powder, and salt and whisk to combine. Cut butter into small cubes and smush with fingers, mixing into the flour, but leaving largely intact. Whisk the egg into the milk, and pour into the flour mixture. Toss with a fork until a dough forms, kneading/folding lightly to get the rest of the flour and spread the butter, then pat into a greased quarter sheet pan. Quarter apples, core, and cut each quarter in half (to make the eighth!). I did not peel mine, and pressed into the dough as best I could on their sides. I had a few slices left over. Bake at 350 F for about 30-40 minutes until the biscuit is lightly browned and the apples are tender. Serve with sweetened whipped cream (and liquid cream, and maybe some maple syrup). If you read the recipe, it seems pretty straightforwardly biscuit-y. But when you get to the middle, it says, "pour into shallow pans and spread one-half an inch thick." Sadly, my dough did NOT pour, and in fact, I had to knead it a bit to get the flour mixed in. If I had been paying closer attention, I would have added a little more milk, but I didn't! So I followed the recipe exactly. The biscuits were also a BIT flat tasting and dry - I would add a teaspoon or so of sugar and more milk (at least a cup), which I think would make something a little more batter-ish, which would presumably rise around the apples a little more. I would also space the apples closer together as they provide the only sweetness. In summation, certainly not a terrible recipe, but not great either. Basically a plain biscuit with baked apples on top. Sadly, this one gets labeled a fail! But I am going to try it again - I might also add some sweet spices like cinnamon or cloves to the biscuit dough and see if that makes a difference. And maybe chop the apples into smaller chunks - not as pretty, but easier to eat. Have you ever tried a recipe and had it fail in some way? Share your trials and tribulations in the comments! The Food Historian blog is supported by patrons on Patreon! Join us for awesome members-only content like free digitized cookbooks from my personal collection, e-newsletter, and even snail mail from time to time!

Thanks to everyone who joined us for Episode 21 of the Food History Happy Hour! We discussed pumpkins and their indigenous origins, as well as the history of pumpkin pie spice, including a discussion of the European spice trade, where various spices come from, and how they went from the purview of the fabulously wealthy to hopelessly old-fashioned, to ragingly popular again. Plus we talk about how pumpkin spice got its name and what's REALLY in those cans of pumpkin puree.

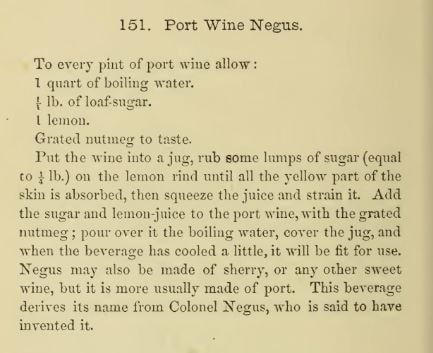

Port Wine Negus (1862)

This particular recipe comes from the famous Jerry Thomas, in his 1862 book, The Bar-Tender's Guide but the drink is actually much older, dating back to the 18th century, and features in the novels of Jane Austen and Charles Dickens. By the Victorian period, it was commonly used for children's parties (shocking I know), and it seems that Jerry Thomas may have lifted his recipe directly from Isabella Beeton.

I followed this recipe pretty closely, and it makes a LOT - I filled my teapot full - so be aware that either you need to save any leftovers for a soda negus (also in Jerry Thomas), share with friends, or cut the recipe down. Here's the original: 151. Port Wine Negus

Here's the version I made:

4 cups water, brought to a boil 2 cups Ruby port 1/2 cup sugar 4 tablespoons bottled lemon juice 4 cloves about 1/4 teaspoon fresh grated nutmeg This makes one and a half quarts of hot Negus, which is delicious but was too sweet for my taste. I'm guessing the original recipe called for Tawny port, which is not as sweet as Ruby port. I also cheated and used bottled lemon juice instead and added cloves because another recipe for soda negus I saw called for them. It really is imperative to use fresh nutmeg for this recipe, as the ground kind doesn't hold a candle in flavor. One or two nutmegs will last you a long time, so you don't have to buy a ton. It is fairly addictive, so just be forewarned. I may or may not have had four cups in the course of Food History Happy Hour and writing this blog... Episode Links:

I had fun researching this topic and even learned a few things! One of my primary sources for the European spice trade as the book Nathaniel's Nutmeg, by Giles Milton. It's a highly engaging read and designed for a more popular audience, so if anyone wants to read about bloodthirsty Europeans obsessed with spice and their various maritime misfortunes, check it out.

other fun links include:

The next Food History Happy Hour won't be until Friday, October 30, 2020, but we'll be discussing Halloween! And making the Stone Fence cocktail. I hope you'll join us then. AND! I have a special treat for Patreon members old and new - join or renew at the $5 level and above, and you'll get a special Halloween packet mailed to you! Chock full of all kinds of fun history, images, party ideas, recipes, and more.

If you enjoyed this episode of Food History Happy Hour and would like to support more livestreams, please consider joining us on Patreon. Patrons get special perks like access to members-only content.

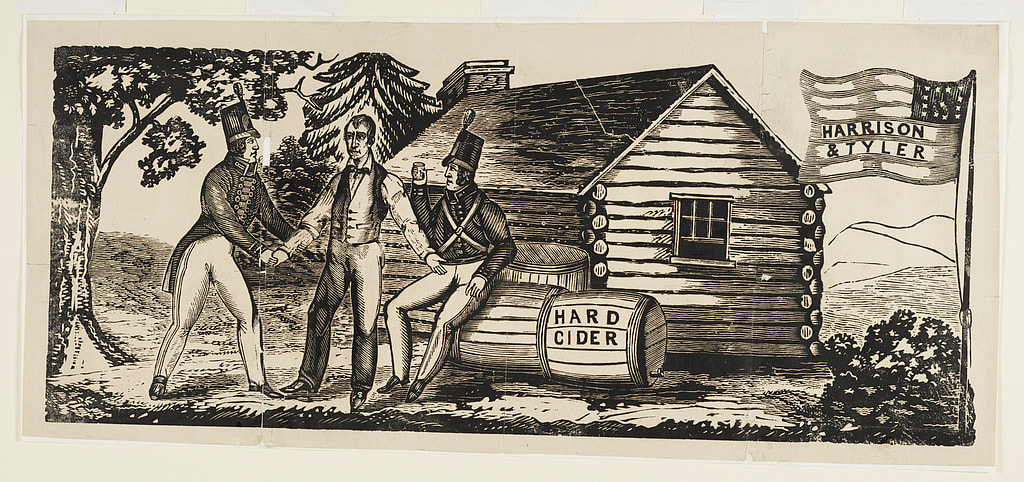

An untitled woodcut, bold in design, apparently created for use on broadsides or banners during the Whigs' "log cabin" campaign of 1840. In front of a log cabin, a shirtsleeved William Henry Harrison welcomes a soldier, inviting him to rest and partake of a barrel of "Hard Cider." Nearby another soldier, already seated, drinks a glass of cider. On a staff at right is an American flag emblazoned with "Harrison & Tyler." Library of Congress.

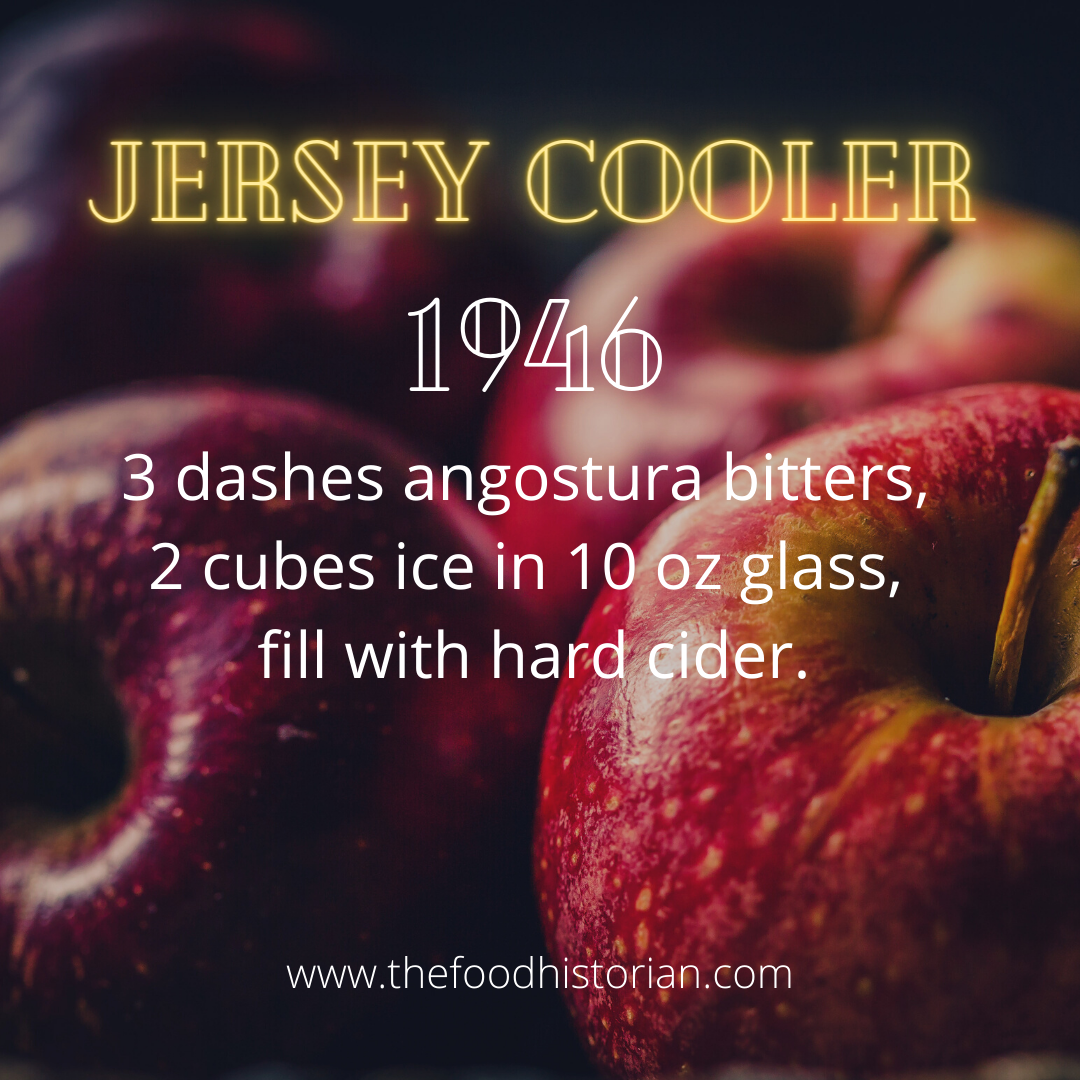

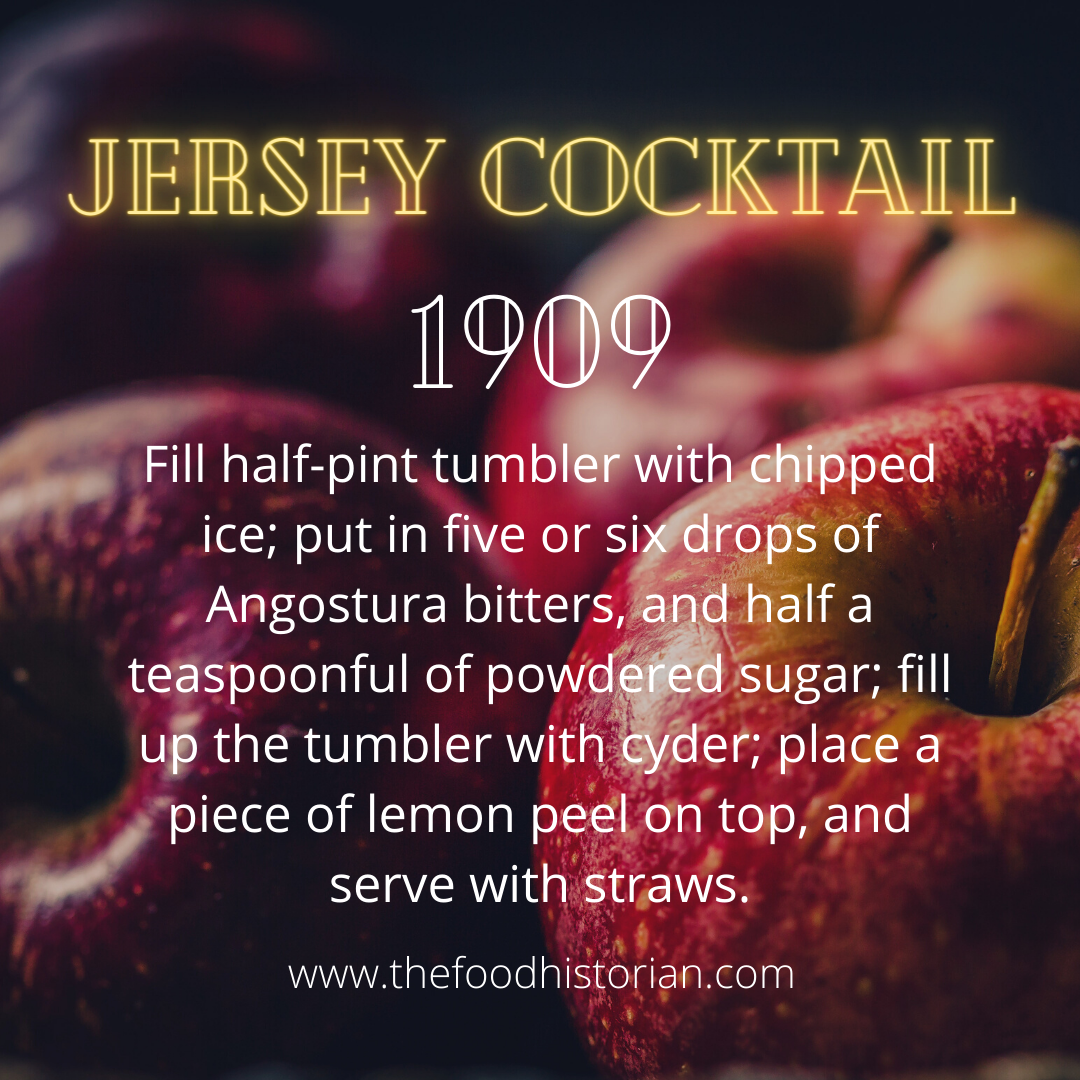

Thanks to everyone who participated in this week's Food History Happy Hour! In this episode we made the Jersey Cooler from the Roving Bartenter (1946), but the cocktail itself appears to have been invented by the famous Jerry Thomas as it appears in his 1862 How to Mix Drinks.

With the primary ingredient hard cider, I thought it a particularly apt cocktail for our discussion of apples in America! I chose apples as the topic for tonight's Food History Happy Hour because mid-September is when apple harvest in the Northeast usually really starts to get underway. Coincidentally (on my part, anyway), tonight is also the start Rosh Hashanah, or the Jewish New Year, which runs until Sunday. One of the components of Rosh Hashanah is the use of apples and honey, particularly in Ashkenazi Jewish households, who originate in Eastern Europe. Apples and honey are eaten to symbolize sweetness and prosperity for the coming year. On a more somber note, I learned that Supreme Court Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg passed away just minutes before the start of the show. In fact, I almost didn't do tonight's episode because I was so upset. But I figured that the notorious RBG would power through if it was her, and it was fitting to be talking about apples and hoping for peace and prosperity in the coming New Year. So we poured one out for Ruth and gave her a toast. We talked about the origins of hard cider, with an aside about the 1840 presidential campaign of William Henry Harrison, why hard cider fell out of favor, the origins of apples in the mountains of Kazakhstan, Johnny Appleseed, the story of Red Delicious, heirloom apple varieties, and the not-so-American origins of apple pie. Jersey Cooler (1946)

From the 1946 Roving Bartender by Bill Kelly:

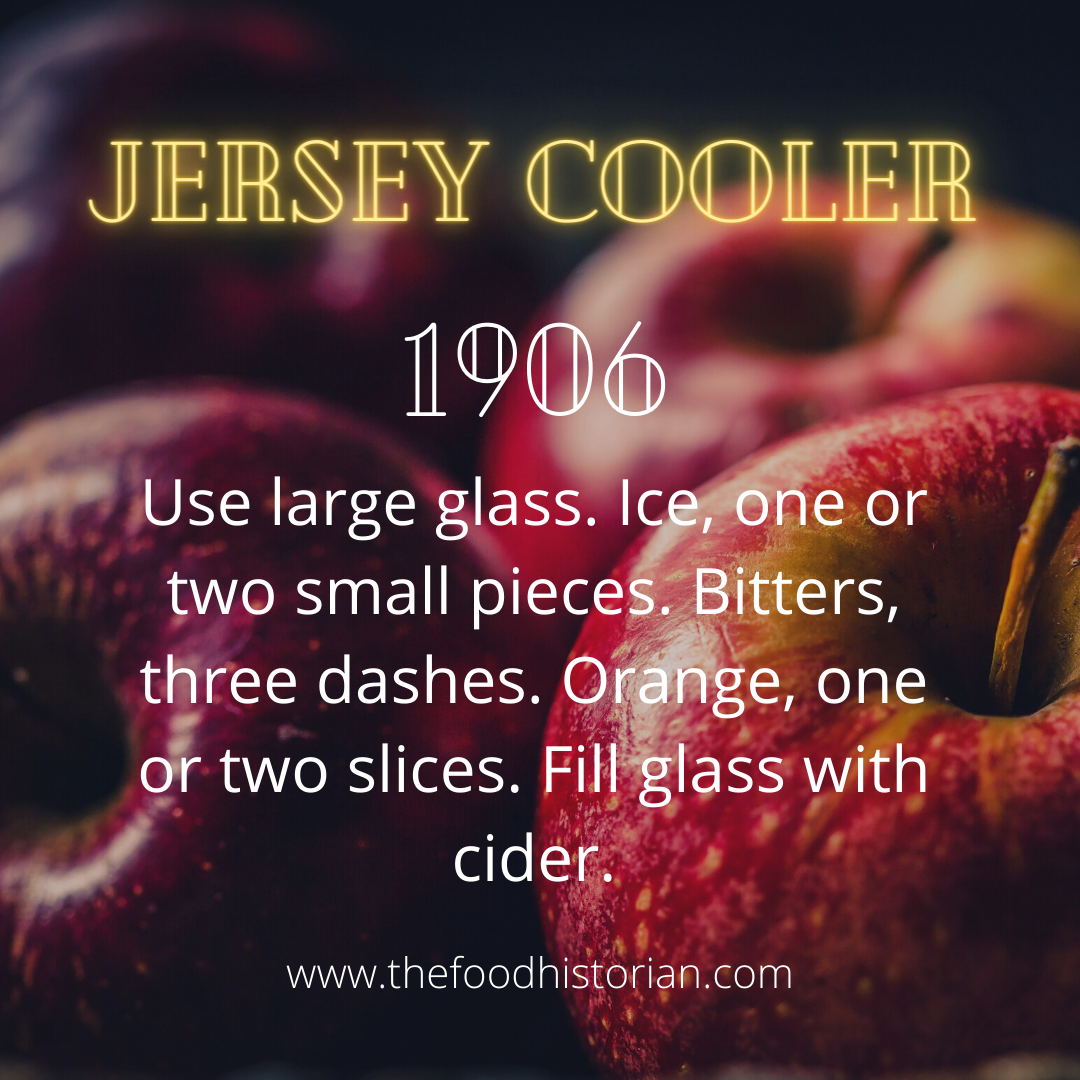

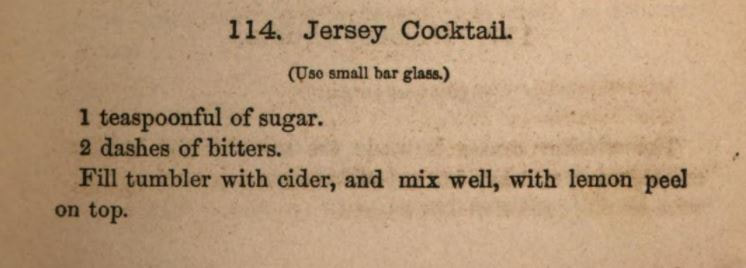

You can see other, slightly more complicated versions below: Jersey Cocktail (1862)

As far as I can tell, this is the oldest version of the Jersey Cooler (called cocktail here), invented by the famous Jerry Thomas from his How to Mix Drinks from 1862. Because the earliest reference is from Mr. Thomas, who was a born and raised New Yorker, I think that the "Jersey" in this instance refers to New Jersey, not Jersey, England.

Here's his recipe: (Use small bar glass.) 1 teaspoonful of sugar. 2 dashes of bitters. Fill tumbler with cider, and mix well, with lemon peel on top. Episode Links

Our next episode will be on Friday, October 2, 2020 and since it will officially be October, we'll be talking about pumpkins and the origins of the much-maligned pumpkin spice!

If you enjoyed this episode of Food History Happy Hour and would like to support more livestreams, please consider joining us on Patreon. Patrons get special perks like access to members-only content.

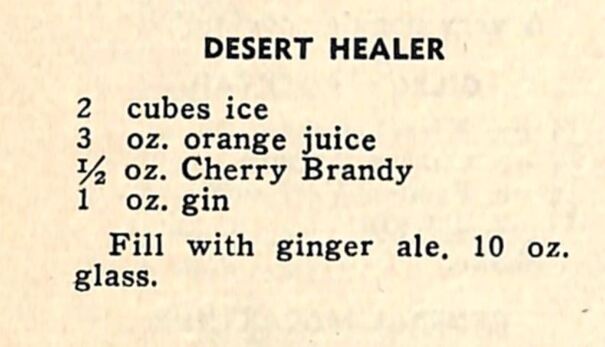

Thanks to everyone who joined me last night for Food History Happy Hour live on Facebook. This week, inspired by the cold, rainy weather we've been having lately, we "visited" the American Southwest with help from the Desert Healer cocktail from the 1946 Roving Bartender. We discussed Mexican food in America, including the cookbook California Mexican-Spanish Cook Book, published in 1914 by home economist Bertha Haffner-Ginger. We also talked about burritos, corn and nixtamalization (including hominy and tortillas), savory fruit salads, sauces, including celery sauce, macaroni and cheese, 19th century pickles, jicama, pickled herring, lutefisk and cod (small correction, mahi-mahi is dolphinfish, not tilapia), and we decided that next week's topics will be 19th century sauces and pickles!

Although cocktails called "Desert Healer" are all over the internet, I couldn't find any history behind either the name or the cocktail. I'm guessing it's just one of those cocktails that someone made up and it took off. If you like your cocktails on the sweeter side, but still with some complexity of flavor, you will probably love this one.

I found this recipe in the Roving Bartender (1946). I did get the recipe slightly wrong and only did a third of an ounce of cherry brandy, but more cherry brandy would have been even better! Desert Healer Cocktail (1946)

2 cubes ice

3 oz. orange juice 1/2 oz. cherry brandy 1 oz. gin (I used American gin, but any is fine) Place ingredients in a 10 oz. glass in order, then fill with ginger ale. Drink with a straw. I found this to be quite delightful and would definitely make it again, especially since it's such a nice way to use up the cherry bounce I made.

And, of course, given all of our discussion of celery and someone's idea that I make a cocktail with celery sauce (yuck), I thought that infusing gin with celery was a delightful idea, and it just so happened that I had cut up the remains of a head of celery for crudite to go with supper. So I had lots of delightfully fresh leaves and a few stalks leftover. Into a half pint jar they went with some gin poured over top and we'll let it steep until next week, when I'll have to decide what kind of gin cocktail I want to make with it.

As mentioned last week, the bar cabinet tour is still on the list, but I might do a recorded tour instead of a live one as I think it will be easier to manage. So stay tuned, and hope to see you all next week!

If you liked this post and would like to support more Food History Happy Hour livestreams, please consider becoming a member or joining us on Patreon. Members and patrons get special perks like access to members-only content.

Thanks to everyone who joined me last night for Food History Happy Hour live on Facebook. This week, with some trepidation, I entered into the territory of raw egg and alcohol with the Cherry Brandy Flip - made with some of my homemade cherry bounce!

Plus, we talked about bananas and banana bread, tonic water, Midwestern food, beer, and more! Special discussion of candle salad. Proceed at your own risk.

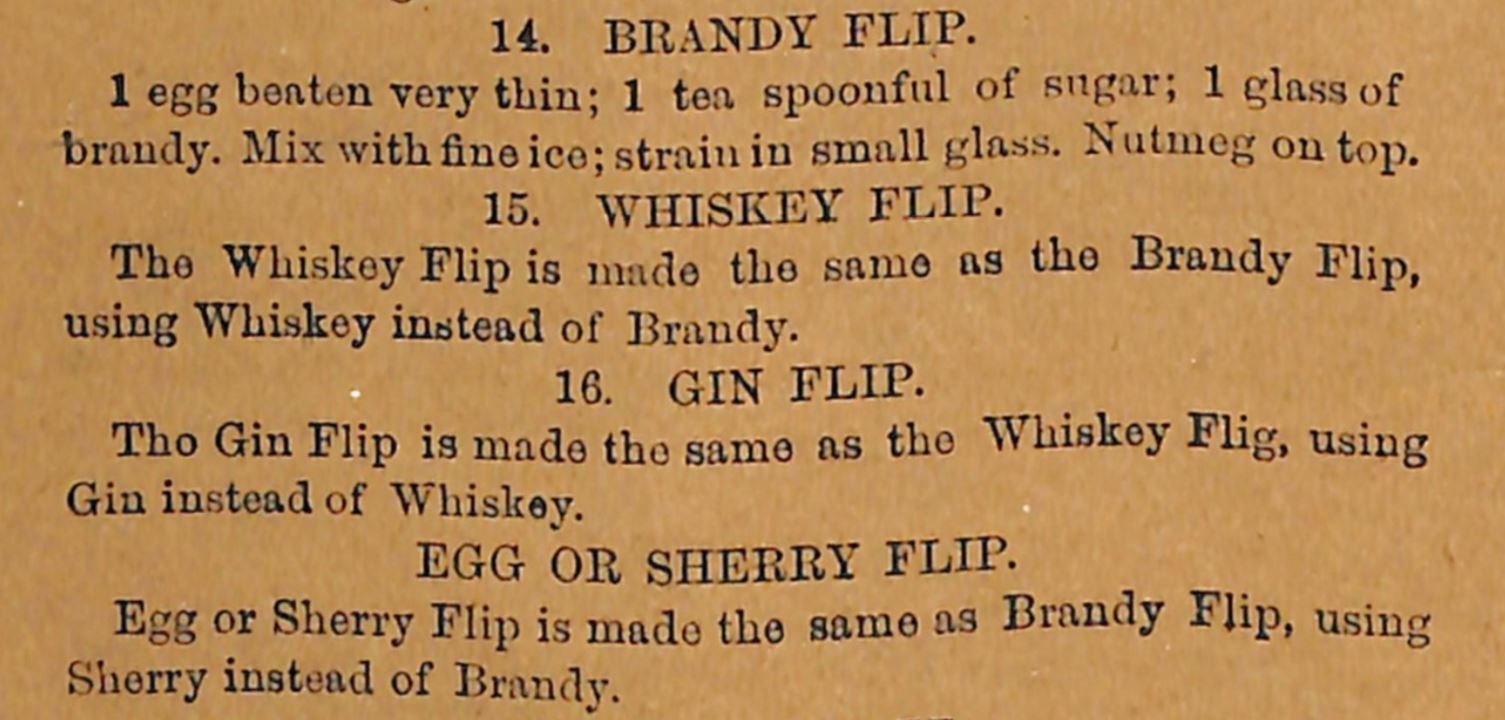

Brandy flips are quite old, and I found a reference to them in The American Bartender, or, the Art and Mystery of Mixing Drinks (1874). There are several flip recipes in there, actually. But I went with the brandy one because I wanted to use up some of my cherry bounce (which is really a cherry brandy), and also because it was requested by Food Historian fans.

The term "flip" is quite an old one, and originally referred to a mixture of ale, sugar, and spices heated with a hot iron poker, which cause the drink to froth or "flip." Later, eggs were added, and eventually, the cocktail shaker was exchanged for the hot poker. The first printed recipe was published in Jerry Thomas's 1862 Bar-Tender's Guide. Known as the father of American mixology, Thomas listed a number of variations on the flip, including the "Cold Brandy Flip." Flips are similar to eggnog, but not quite the same as they do not contain cream, as eggnog does. But the flavor profile is similar. Flips have fallen out of fashion in most bars, in large part because they require the use of a raw egg. Historically, eggs were not washed before being sold, and the protective coating on the shell protected them from contamination, including salmonella. Today, eggs are washed before being sold, removing the protective coating, and opening them up to the possibility of salmonella contamination. Some people claim that the alcohol "cooks" the egg, and hot water (or hot poker) in the hot flips certainly does. But please keep in mind that you proceed at your own risk if you choose to replicate this cocktail. I thoroughly washed my egg again, just to be sure, and used a pastured, free-range, local egg. But you never know. Cherry Brandy Flip

1 whole egg

1 jigger (1 1/2 oz.) cherry brandy 1 oz. simple syrup cracked ice freshly grated nutmeg Place the egg, brandy, and simple syrup in a cocktail shaker WITHOUT ice (this is called a dry shake). Make sure to seal the shaker well. Shake thoroughly until your arms are tired. This emulsifies the egg. Add cracked ice, and shake again, until your arms are tired. Strain into a small wine glass or generous cocktail glass, and grate fresh nutmeg on top. This was better than I expected, although it does taste a bit "eggy" - probably those lovely free range eggs I used. If I made it again, I would add the nutmeg before shaking, or stirring it in. The egg not only emulsifies into something fairly creamy, it makes a frothy head as well. As for the Food Historian Happy Hour Livestream, we MIGHT be doing a tour of my vintage bar/liquor cabinet next week AND, I got a new, higher quality camera for livestreaming. So you can look forward to way less pixelation. Hope to see you next week!

If you liked this post and would like to support more Food History Happy Hour livestreams, please consider becoming a member or joining us on Patreon. Members and patrons get special perks like access to members-only content.

Thanks to everyone who joined me last night for Food History Happy Hour live on Facebook. I had a blast and everyone asked such great questions!

In this week's episode, we covered a LOT of ground and discussed how applejack is made, shrub, eugenics, Americanization of immigrants, comparisons between modern issues with dairy farming, dumping milk, and plowing under fields of vegetables and what happened during WWI and the Great Depression, types of dairy cows and how dairy farming works (including a discussion of veal), Victory gardens, agricultural policy history, historic baking, and flips (including Tom & Jerry). WHEW! The hour flew by and I had so much fun. You can watch the whole thing below.

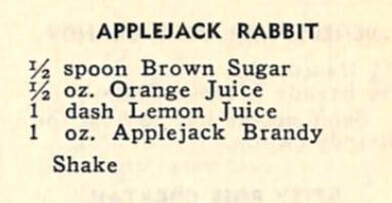

And of course, I made a vintage cocktail! This week's cocktail is the Applejack Rabbit and it comes from the 1946 cocktail book, The Roving Bartender by Bill Kelly.

We talked a little bit about cocktail glasses and serving sizes because of course this week I did NOT use a Collin's glass, but rather a small martini glass. In his introduction to The Rover Bartender, Kelly writes, "As the drinks are shorter now, the glasses for mixed drinks should be shorter and the drink recipes in this book are especially for cocktail glasses of not over 2 1/2 ozs. If a larger glass is used, the proportions will have to rise. You may serve a pony of cognac in a 20 oz. snifter glass, but if a cocktail glass is not near full it is unsatisfactory to the customer." I can certainly agree! But as someone who prefers a cocktail to be only a few ounces, I can't say I enjoy the generally much larger glasses of modern bars and restaurants. They may be easier to handle and clean, but they're too big! Applejack Rabbit Cocktail (1946)

The original recipe is as follows:

1/2 spoon brown sugar (I used about half a tablespoon) 1/2 oz. orange juice 1 dash lemon juice 1 oz. applejack brandy Pour over ice in a cocktail shaker and shake for longer than you think you should to make sure the brown sugar is dissolved. Strain into a small cocktail glass, such as martini glass or old-fashioned champagne glass. Sip cold. Virginia Apple Cake Recipe

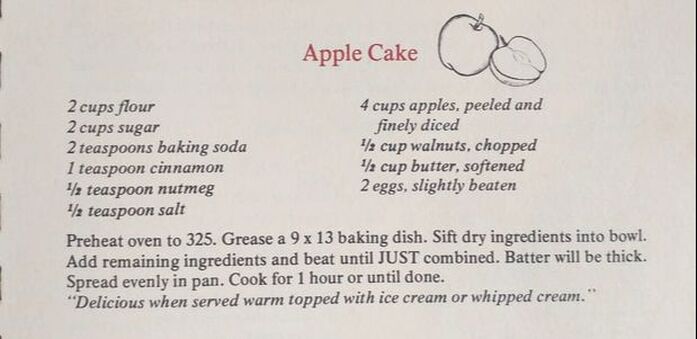

And, since we talked about historic baking, I thought I would share the recipe for apple cake I found recently in my copy of Virginia Hospitality (1976, my copy is the 1984 reprint). This particular Junior League cookbook is quite good with many of the recipes arranged by region and with decent head notes for many. Alas, this "Apple Cake" has neither headnotes nor region assigned. But it looked intriguingly easy and used up quite a bit of apples.

However, as I discussed in the episode, it really is a strange cake. As such, while I've included a photo of the original recipe, I've written my own version to help walk you through how the recipe should work.

2 cups flour

2 cups sugar 2 teaspoons baking soda 1 teaspoon cinnamon 1/2 teaspoon nutmeg 1/2 teaspoon salt (note - I would add 1 teaspoon next time, the cake tasted a bit "flat") 4 cups apples, peeled and finely diced (about 3 medium apples) 1/2 cup walnuts, chopped 1/2 cup (1 stick) butter, softened 2 eggs slightly beaten Preheat oven to 325 F. Grease a 9"x13" baking dish (I used metal). Whisk dry ingredients in a bowl, then add apples and walnuts and stir to coat. If butter is refrigerated, microwave in 10-15 second intervals until very soft but not totally melted. Add butter and eggs to the dry ingredients and mix/fold with a wooden spoon until no loose flour remains. It will seem like not enough moisture - just keep folding, it will come together. The batter will be very thick. Do not overbeat. Spread evenly in the pan. Bake for 1 hour or until done. (I baked mine for 1 hour and 5 minutes, as the middle still seemed a bit soft). In all, my husband LOVED this recipe, but it was not my favorite. Next time I would definitely add some extra salt as the cake tasted a bit "flat" without it. In retrospect, I also MIGHT have accidentally added 2 teaspoons of cinnamon instead of one? Oops. It was too much cinnamon for me, but as I said, my husband loved it as it reminded him of carrot cake. Baking it for an hour at 325 seemed like way too long, but it did result in nicely caramelized edges (all that sugar). However, all the apples melted into the cake! So next time I would probably cut them a bit bigger. I did almost mince them in some cases.

So what did you guys think of this week's episode? Are you going to join me next Friday on Facebook? I hope to see you there! Thanks again to everyone who watched live and remember, if you have any burning food history questions, you can send them to me in advance, message The Food Historian on Facebook, or ask live during the broadcast. See you soon!

If you liked this post and would like to support more Food History Happy Hour livestreams, please consider becoming a member or joining us on Patreon. Members and patrons get special perks like access to members-only content.

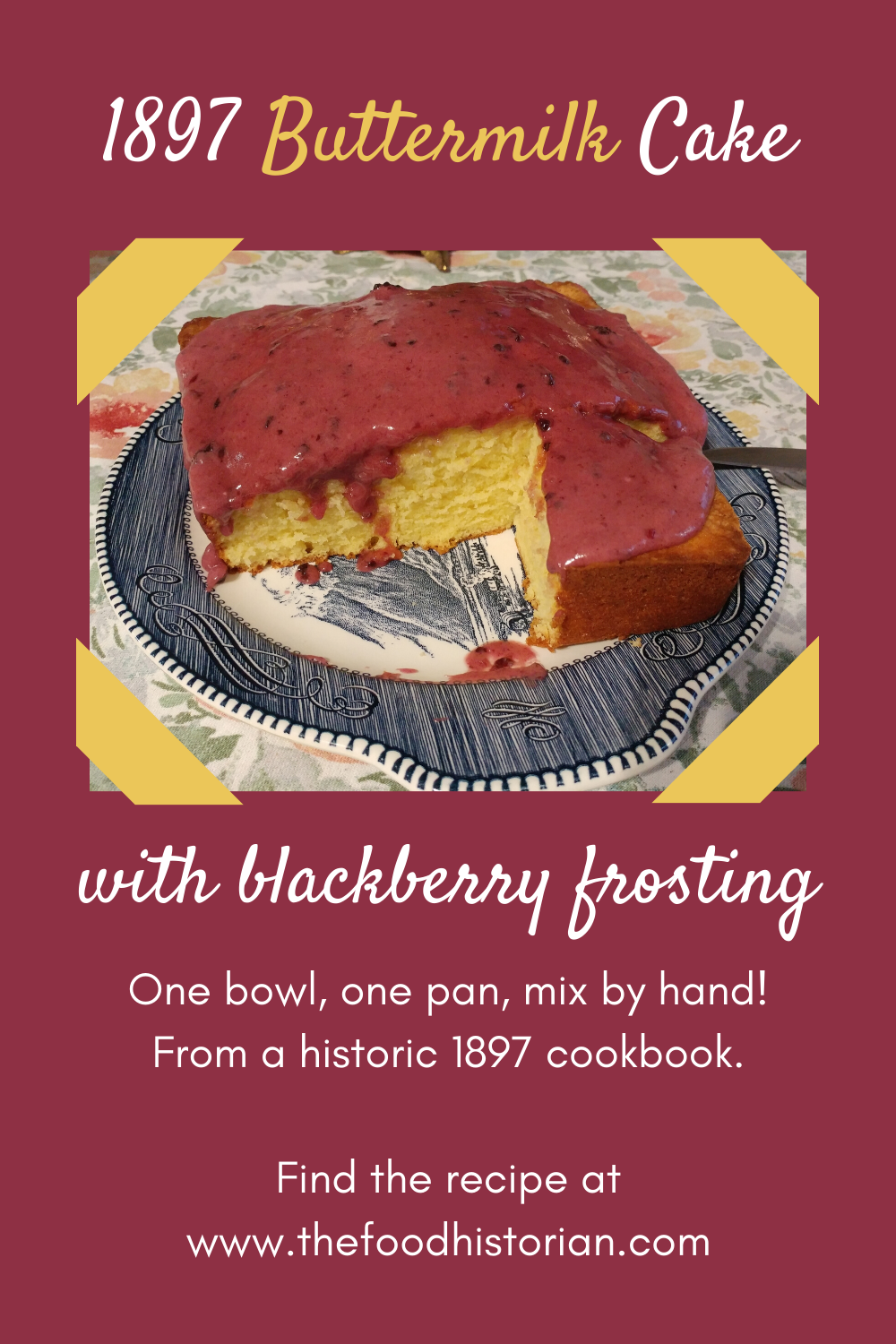

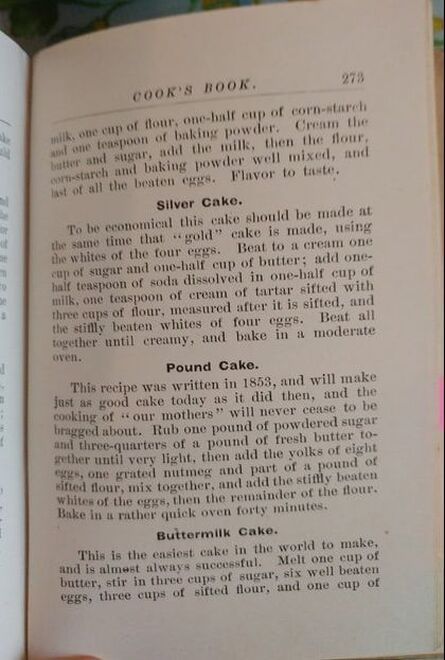

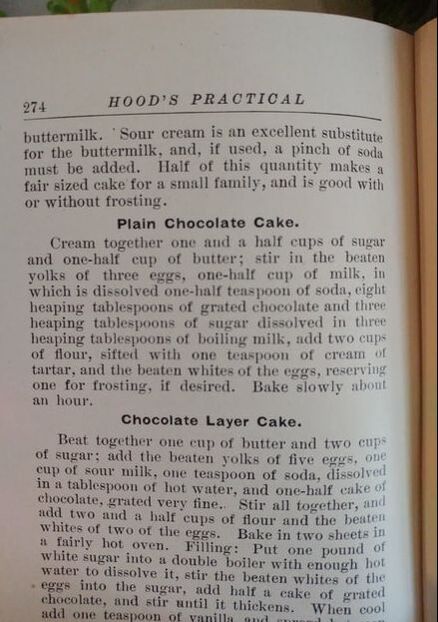

I haven't felt like cooking or baking much lately, except, of course, until I do. I wanted to bake an easy from-scratch cake and thought I would peruse my vast cookbook collection to see what I could find. Published in 1897 in Lowell, Massachusetts, Hood's Practical Cook's Book: For the Average Household, is delightful. My particular copy is in near-mint condition in part because it was printed on high quality paper. It's also quite small, almost pocket-sized. Buttermilk Cake This is the easiest cake in the world to make and is almost always successful. Melt one cup of butter, stir in three cups of sugar, six well beaten eggs, three cups of sifted flour, and one cup of buttermilk. Sour cream is an excellent substitute for the buttermilk, and, if used, a pinch of soda must be added. Half of this quantity makes a fair sized cake for a small family, and is good with or without frosting. What a delightful little description! And indeed, it IS the "easiest cake in the world to make," in part because it uses melted butter. In modern kitchens, where butter is almost always kept in the fridge, softening it for a typical cake recipe takes forever. BUT - I did make a few teensy tweaks, and of course the original recipe as written doesn't include any instructions for the oven temp, baking time, or type of cake pan to use. So, I figured I'd give my own version, especially since, in a household of two adults, I think we qualify as a "small family," so I cut the recipe in half, as suggested. I also added a "pinch" of soda as I wasn't sure the eggs alone were enough to leaven the cake. And despite the fact that it probably would be great without frosting, I felt like frosting, and blackberry jam seemed like the perfect fit for a simple buttermilk cake. 1897 Buttermilk Cake with Blackberry ButtercreamFor the cake: 1/2 cup butter (1 stick), melted 1 1/2 cups granulated sugar 3 eggs 1 1/2 cups all-purpose flour pinch of salt 1/4 teaspoon baking soda 1/2 cup buttermilk For the frosting: 3 tablespoons butter, softened 1/4 cup blackberry jam powdered sugar Preheat the oven to 350 F. Grease an 8"x8" metal baking pan. Stir sugar into melted butter and add beaten eggs, flour, salt, baking soda, and buttermilk. The batter will be quite thick. Pour into baking pan and level with a spoon or spatula. Bake for approximately 45 minutes (check after 30), or until the cake center is firm and springs back when gently depressed. While the cake is baking, make the frosting. Beat the jam and butter together, then add powdered sugar, 1/4 cup at a time, until the frosting thickens. When the cake is done, remove from pan and cool on a baking rack. Once cool, frost the top. This is a rustic-looking cake and mine got quite a dome, but if you CAN slice it in half, feel free to do so and fill with frosting (double the recipe).  I couldn't wait for my cake to cool completely before frosting, so the frosting got a bit melty, but it was still delicious! The cake wasn't too sweet, despite all the sugar in it, and closely resembled the taste and texture of Lazy Daisy/Hot Milk Cake, but somehow even lazier? Delightful. I will definitely be making this again, but I might experiment with one fewer egg (or two extra large eggs), as the cake did taste a bit eggy and obviously rose quite high. I'm guessing it's because eggs in the late 19th century weren't quite as large as today's standard large eggs. So what is everyone else baking during home confinement? Anything interesting? Share in the comments! As always, if you liked this post, consider becoming a member or joining us on Patreon. Members and patrons get special perks like access to members-only content.

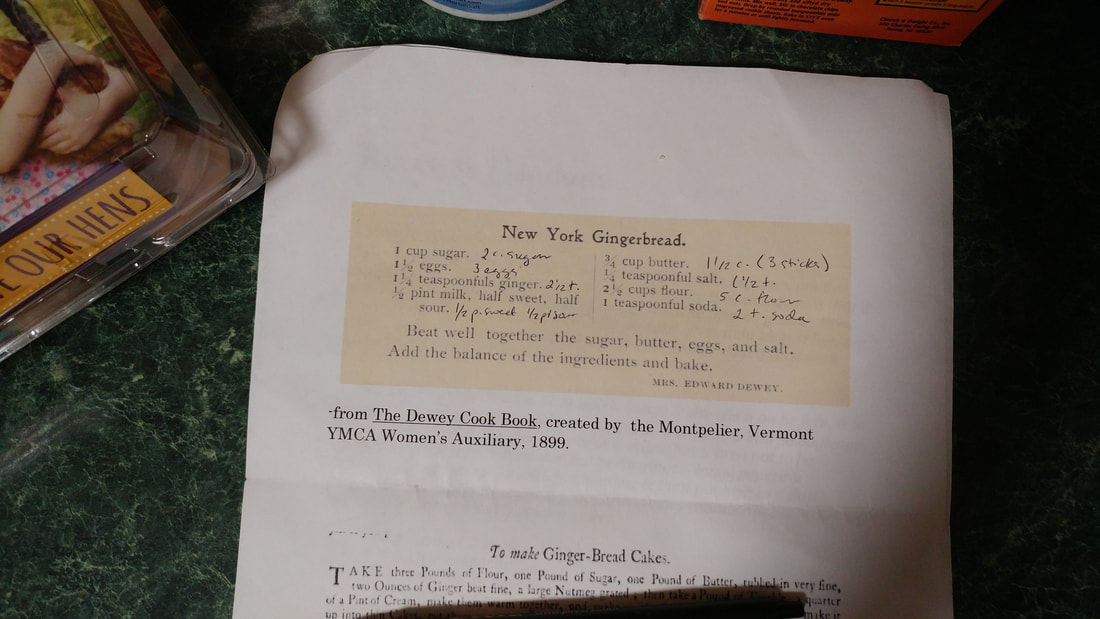

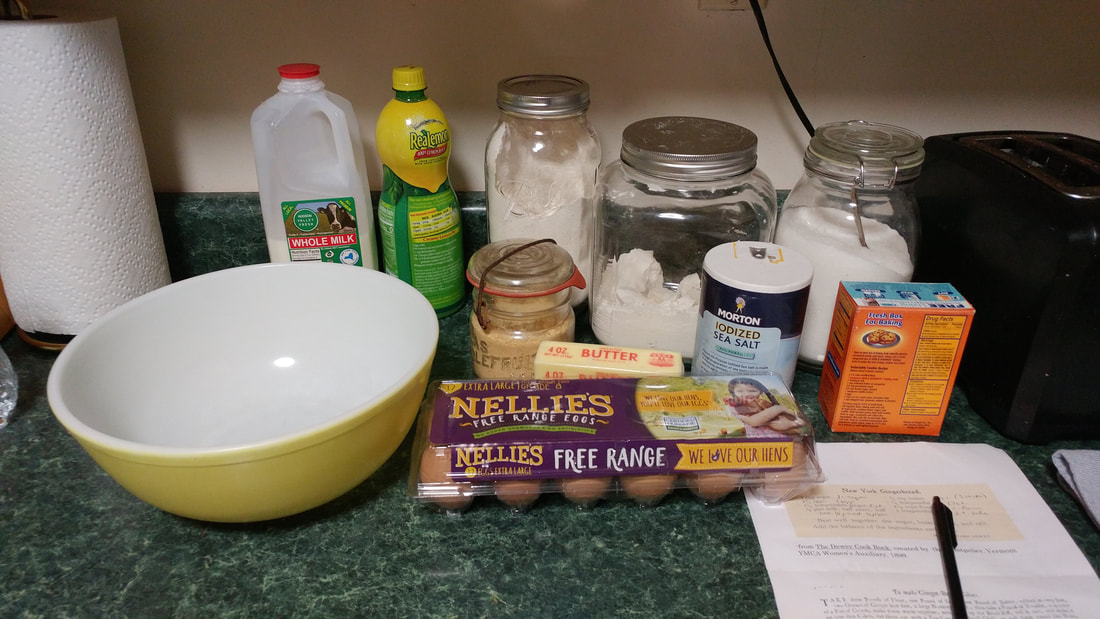

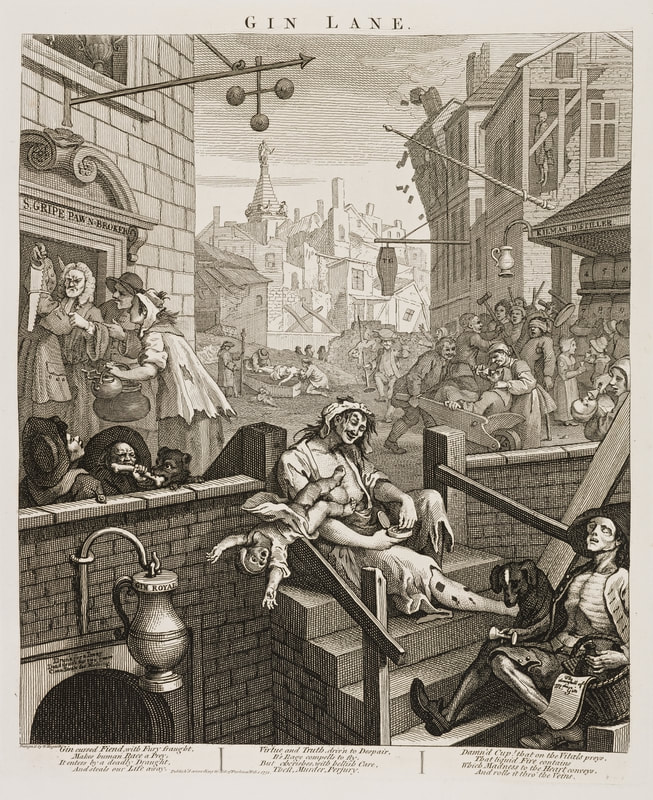

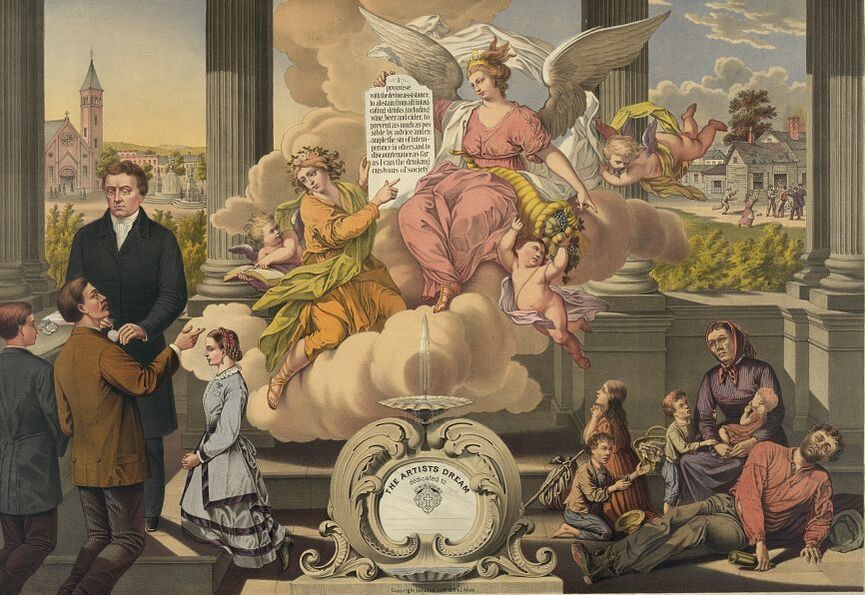

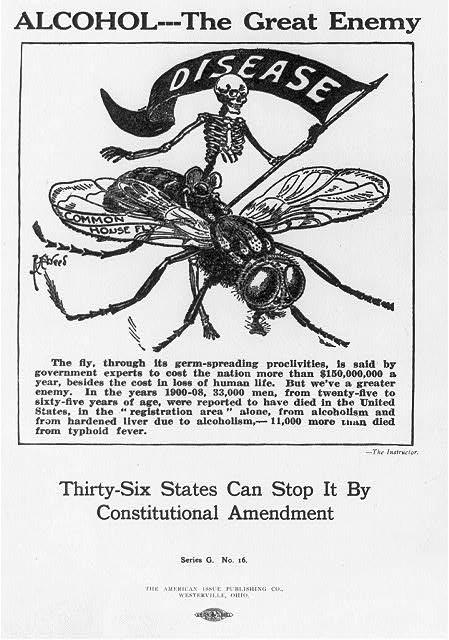

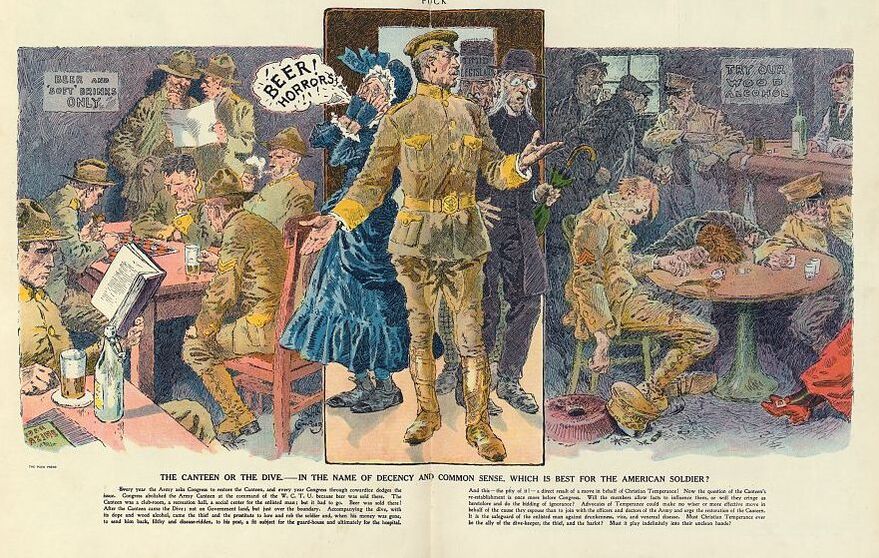

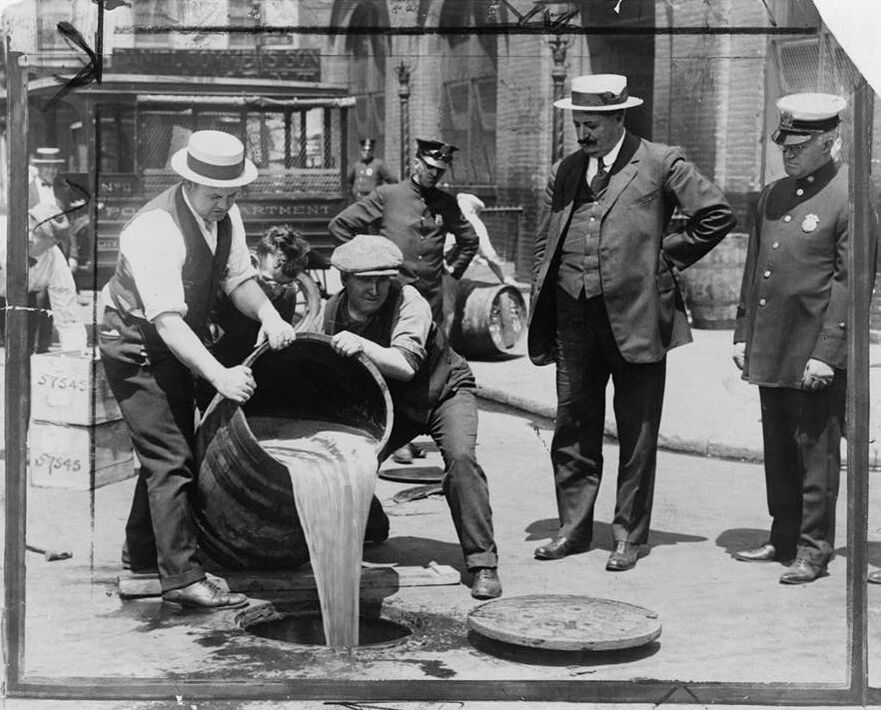

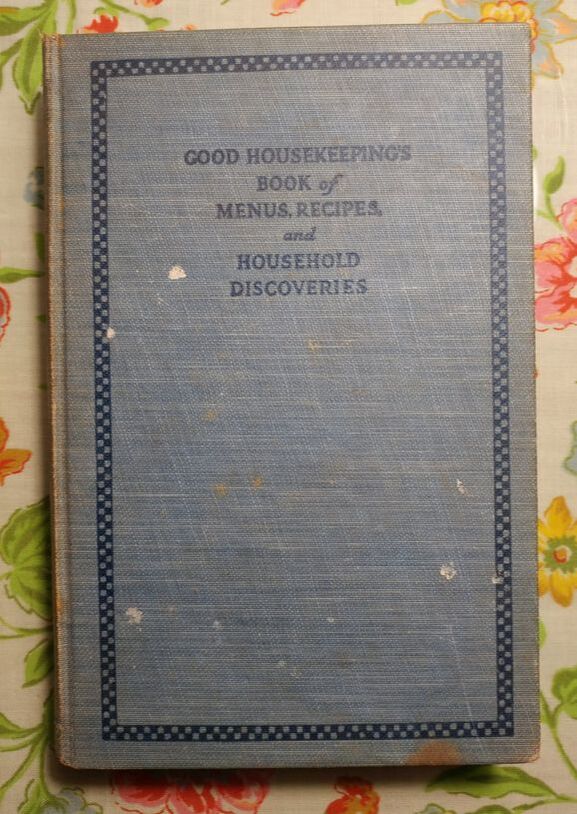

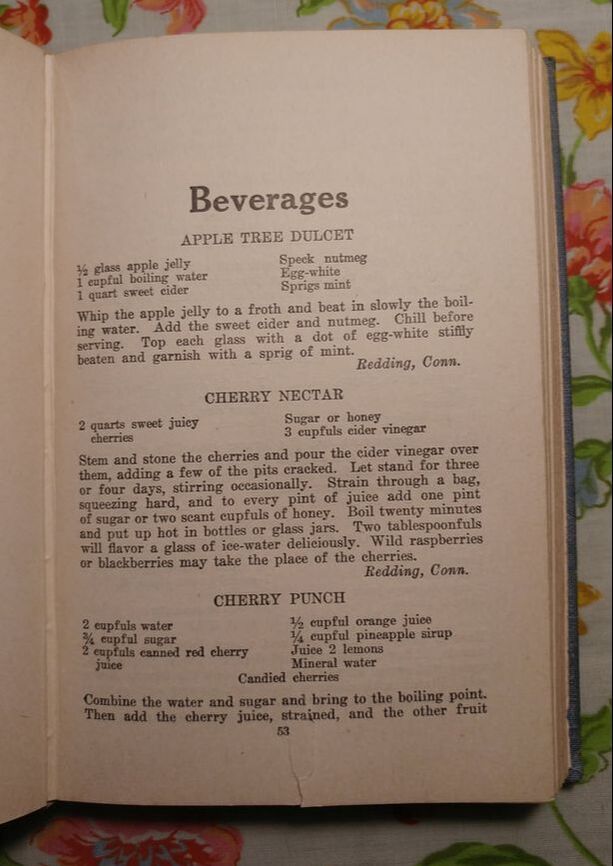

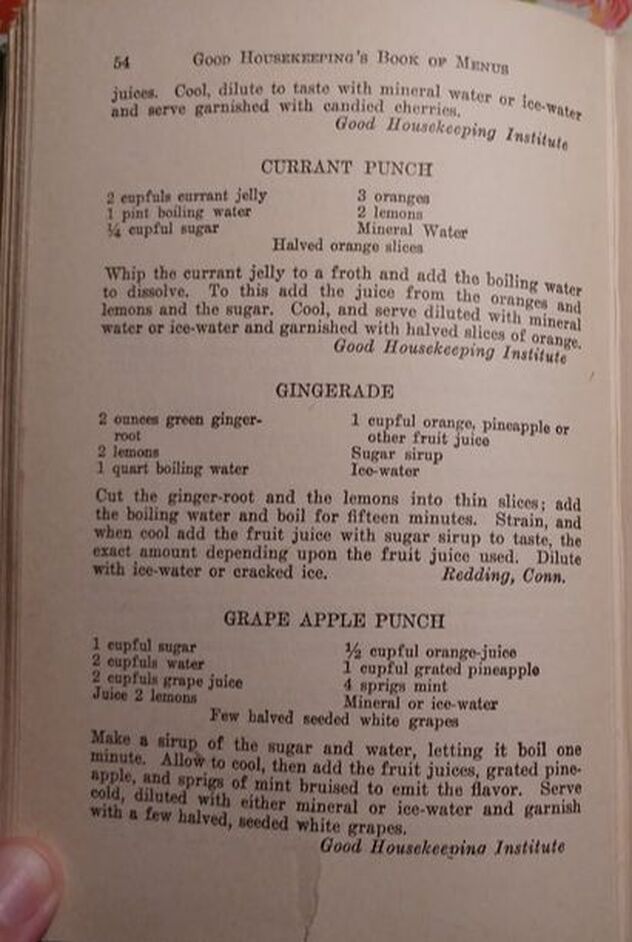

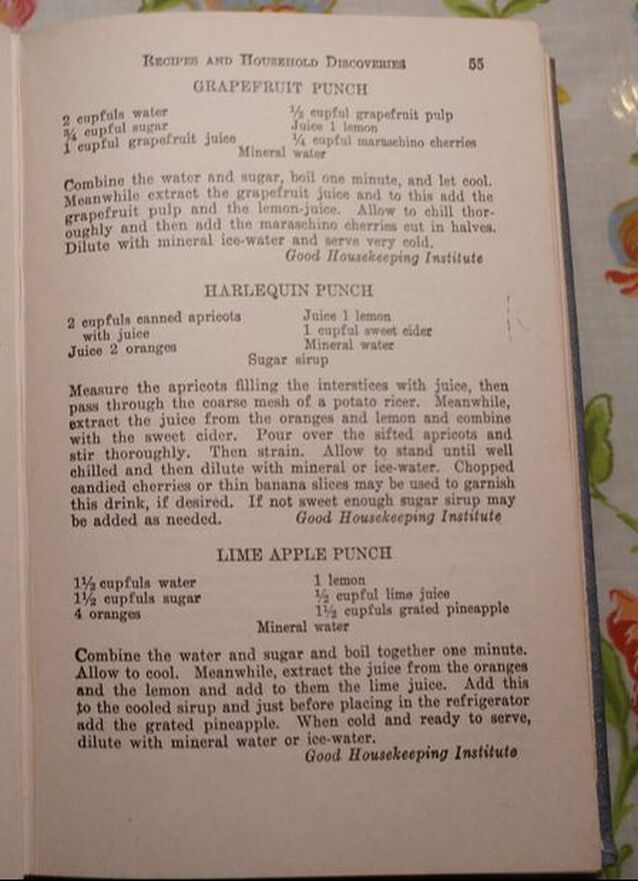

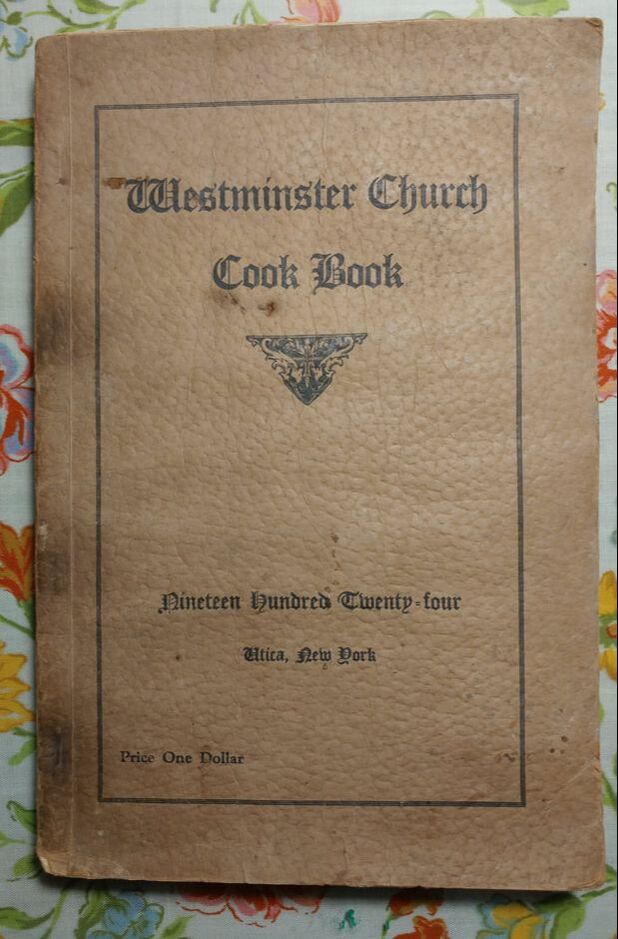

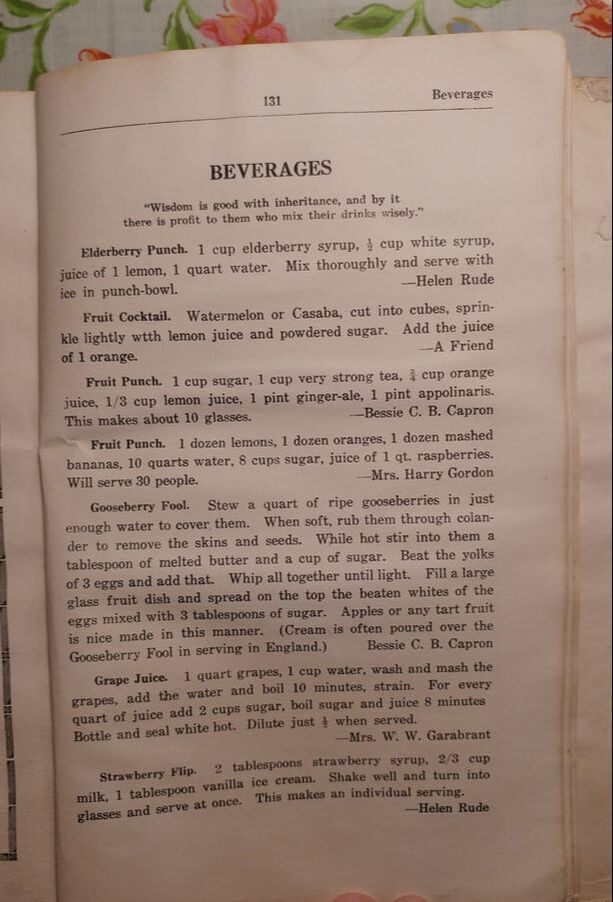

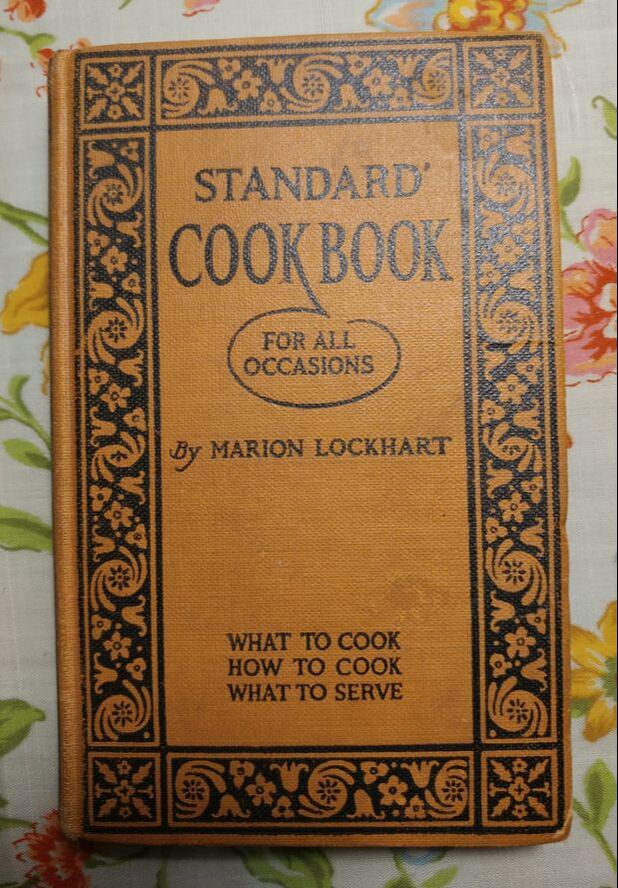

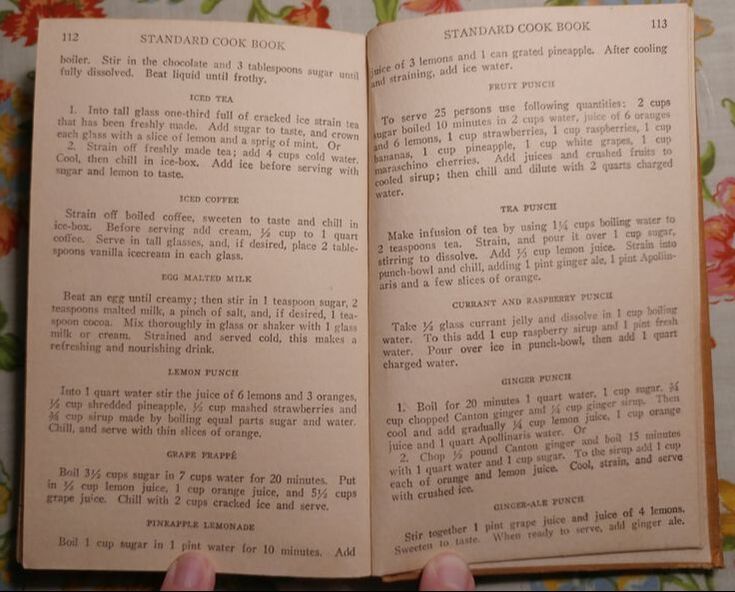

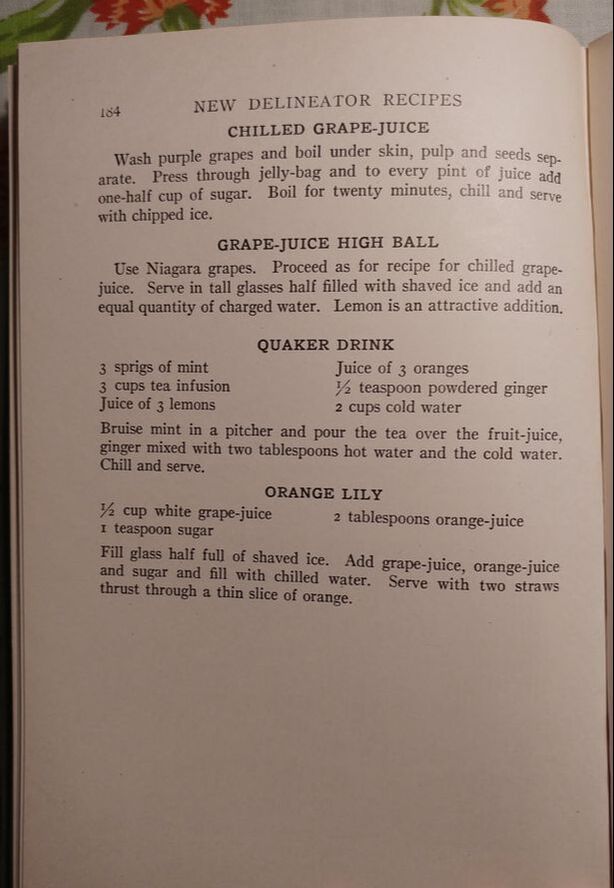

A few weeks ago my fellow food historian Niel De Marino gave a wonderful talk on Christopher Ludwick, an 18th century German immigrant to Philadelphia who ended up not only extremely successful, but also the baker general for the entire Continental Army. Niel also operates The Georgian Kitchen and is well-known for his impeccable attention to detail when he recreates historical recipes. Niel also teaches 18th century cooking at Historic Eastfield. For this talk, he baked not only give different gingerbreads, dating from the 1400s to the very late 19th century, he also baked stunning examples of molded gingerbreads. Although they were all delicious, my favorite was New York Gingerbread, and Niel was kind enough to share the recipes with everyone. So, when it came time to bake for a friend's housewarming gift (a very charming idea my husband came up with - salt, a broom, and bread), I immediately wanted to try my hand at the New York Gingerbread. Of course, I've recently been watching quite a bit of the Great British Baking Show, and this recipe felt a bit like one of their technical challenges - a classic, but with VERY sparse ingredients. The original recipe, which was published in the Dewey Cookbook in 1899, reads: 1 cup sugar 1 1/2 eggs 1 1/4 teaspoonfuls ginger 1/2 pint milk, half sweet, half sour 3/4 cup butter 1/4 teaspoonful salt 2 1/2 cups flour 1 teaspoonful soda Beat well together the sugar, butter, eggs, and salt. Add the balance of the ingredients and bake. New York Gingerbread (1899)I assembled my ingredients, but because who on earth knows how to add a half an egg, I doubled the recipe thusly AND added instructions, just for you lay-bakers. You'll also notice, that unlike typical gingerbread recipes, this one contains neither molasses nor spices other than ginger. It gives it a gentle heat and a nice purity of flavor. And despite 2 cups of sugar, it's not overly sweet. 2 cups sugar 1 1/2 cups butter (three sticks) 3 eggs 5 cups flour 1/2 teaspoon salt 2 1/2 teaspoons ground ginger 1 teaspoon baking soda 1 cup milk 1 cup buttermilk OR 1 tablespoon lemon juice topped off by milk to make 1 cup sour milk Preheat your oven to 350 F and lightly grease two standard loaf pans. Cream butter and sugar together until smooth, then beat in eggs. Add flour, salt, ginger, and baking soda and start to stir into the butter mixture. Then add the sweet milk and stir a little more, then the sour milk or buttermilk. Work quickly to stir everything together - the batter will be quite thick. Spoon into each loaf pan until the batter looks equal, then place in the hot oven and bake approximately 65 minutes or until the loaves are cooked through. Let cool in the pans for a few minutes, then tip out onto a cooling rack to finish cooling. Serve warm or room temperature plain or with with whipped cream. For a great deal of guesstimating, I think this turned out quite well! A couple of notes: one is that I didn't have enough white all-purpose flour to do the double bake, so I used about half spelt flour. Which likely accounts for the darker color than Niel's. In addition, my baking soda was over a year past its expiration date. Between the heavier flour and the slightly flat soda, I think that accounts for the denser texture than Niel's, which were quite fluffy, but still chewy. That being said, the flavor was almost identical, although you can taste the spelt flour a bit in mine. Final verdict? I would totally make this again. It's addictively subtle - just spicy and sweet enough that you want to keep eating it. The crust is a bit crunchy right now, which I like, but as it sits (I'm storing it in a gallon ziplock bag), the crust will get tender and a bit sticky. Much like banana bread, which this strongly resembles. Niel says he bakes this in loaf pans (like I did) and does two things: either he double bakes it to make rusks, or he makes a trifle with custard and (get this) LEMON CURD. He's such a genius, and I'm so grateful he shared this recipe! Also grateful I was able to make a pretty good version of my own. And, as always, if you liked this post, consider becoming a member or joining us on Patreon. Members and patrons get special perks like access to members-only content. Well, dear readers, it seems as though we are in the '20s again, and since "Dry January" seems to be a growing trend, I thought I would look at some historic alternatives to alcohol for those who don't imbibe or those who are taking a break. Prohibition, the 18th Amendment to the Constitution banning importation, production, sale, and consumption of alcohol in the United States, officially took effect across the country in January, 1920. It was a long, long road to the Constitutional amendment. Begun in the late 18th century, the Temperance movement was a response to the increasing consumption of distilled liquor by the general populace. Rum, distilled by slaves from molasses produced by brutal Caribbean sugar plantations, was flooding the market at the end of the 18th century. Cider, ale, and small beer were common daily beverages. John Adams was known to enjoy hard cider with breakfast. George Washington adored Maderia. All the founding fathers drank at levels that seem excessive by today's standards. And the Whisky Rebellion was just the beginning of American distilling. Alcohol was a way to preserve and consume calories (whether from apples or grain) and was known to be safer for drinking than most water. But it had unsavory unintended consequences. For Temperance advocates, alcohol enhanced all of humanity's sins: drunkenness begat violence, both domestic and public, and wasted hard-earned wages while children starved. In February, 1751, the famed British satirical artist William Hogarth published a pair of etchings in reaction to the Gin Craze. They were meant to be viewed side-by-side, with "Beer Street" at the left and "Gin Lane" at the right. The etchings were accompanied by the following poem: Gin, cursed Fiend, with Fury fraught, Makes human Race a Prey. It enters by a deadly Draught And steals our Life away. Virtue and Truth, driv'n to Despair Its Rage compells to fly, But cherishes with hellish Care Theft, Murder, Perjury. Damned Cup! that on the Vitals preys That liquid Fire contains, Which Madness to the heart conveys, And rolls it thro' the Veins. The pair of images was meant to illustrate the evils of gin consumption in London. In the above image, emaciated drunks line the streets. A drunken woman lets her baby fall to its death. A person has hung themselves in a dilapidated building and other dwellings are falling down. The distillery, pawn shop, and coffin maker are all doing very well and EVERYONE is drinking gin. Meanwhile, on Beer Street, healthily rotund, industrious people are resting from their day's work to have a beer. The pawn broker's building is a dilapidated ruin, the dwellings in good shape as construction begins on another, and everyone is well-dressed and otherwise in good spirits. This images was accompanied by the following poem: Beer, happy Produce of our Isle Can sinewy Strength impart, And wearied with Fatigue and Toil Can cheer each manly Heart. Labour and Art upheld by Thee Successfully advance, We quaff Thy balmy Juice with Glee And Water leave to France. Genius of Health, thy grateful Taste Rivals the Cup of Jove, And warms each English generous Breast With Liberty and Love! If we were to compare 18th century Britain to America, we might replace gin with rum (with its problematic connections to slavery), and beer with hard cider, the drink of choice for thousands of colonists and later American citizens. William Henry Harrison won the 1840 presidential election by running as the "log cabin and cider" candidate - meaning a Western pioneer, the better to appeal to rural voters against the much-maligned Martin Van Buren, of upstate New York, who lost his reelection campaign. But while whiskey, rum, and "fortified" wines like Madeira and port remained popular beverages throughout the 18th and 19th century, alcohol consumption remained as a problem for women and children. Although many Temperance advocates initially just targeted distilled spirits, soon beer and wine and indeed, any alcohol at all, was decried as the root of many evils. Many abolitionists were also Temperance advocates. Lyman Beecher, father to cookbook author Catherine Beecher and her more famous author sister, Harriet Beecher Stowe, was an early Temperance advocate. Connected to a religious revival in America as part of the Second Great Awakening, Temperance gained traction in communities throughout the United States. The above image is a 19th century analog to the Hogarth images. At left, a healthy-looking family kneels before a man who is perhaps a minister. The angel of Temperance with her anti-alcohol pledge floats down on a cloud, with cupids and a cornucopia of prosperity. In the background, a new and prosperous looking church At the right, a drunkard, bottle in hand, sprawls on the floor. His overworked wife and starving children huddle in the background, with the little girl praying to the glorious angel. Sad looking shacks appear behind them, with a mob of people in the street. After the Civil War, the fight for Temperance continued. Throughout the 19th century, towns, counties, and even states held referendums on whether or not to go "dry." Some advocates installed drinking fountains in public squares in cities around the country. The Women's Christian Temperance Union, one of the strongest proponents of Temperance, formed in 1874. In 1900, Carrie Nation took to violence, chopping up saloons with a hatchet, to try to suppress alcoholism. In 1913, the federal income tax was instated. For the first time, the federal government had a form of tax income that did NOT come directly from the sale of alcohol, which had previously been the main source of tax income. During WWI, the Temperance movement and the Prohibitionists used the threat of wartime and even the need to conserve grain as a reason to instate Prohibition. Here, the threat of alcoholism and "hardened liver" is compared to the deaths caused by the common house fly. At the bottom, the flyer calls for a Constitutional Amendment. Published in 1917, this flyer was created at the outbreak of World War I. Although the United States was not at war when the above image was published in Puck, it nevertheless made a case to reinstate the Army canteen, where beer and soft drinks were sold. Congress had apparently disbanded them by grace of the Women's Christian Temperance Movement - illustrated here by a hysterical older woman in blue and accompanied by an elderly minister and, in the rear, a "timid legislator." The comparison is made between an Army-sponsored canteen and a public "dive," where soldiers drink to wrack and ruin and can consort with the prostitute implied by her red dress and shoes in the lower right hand corner. This illustrates that some people still fought to keep beer and hard cider as a part of daily life, even as public opinion against distilled spirits waxed to a frenzy. Thirty-six states did, indeed, ratify the 18th Amendment on January 16, 1919. It read, "After one year from the ratification of this article the manufacture, sale, or transportation of intoxicating liquors within, the importation thereof into, or the exportation thereof from the United States and all territory subject to the jurisdiction thereof for beverage purposes is hereby prohibited." Prohibition, as it came to be known, went into effect on January 16, 1920. Prohibition came to represent government overreach into peoples' daily lives and the criminalization of alcohol allowed organized crime to flourish in the 1920s, despite the best efforts of police. Gangsters like the infamous Al Capone, wielding machine guns they learned to use in the First World War, made fortunes off of illegal distilleries, speakeasies, and other criminal enterprises, all while dodging federal taxes. Well, at least until the Feds catch up with you, right Al? The wealthy could afford to keep consuming booze (often from the wine cellars amassed on their private estates) as police and prosecutors largely looked the other way. The poor and middle class risked their lives on bathtub gin, wood alcohol, and methylated spirits (also known as denatured alcohol) which caused blindness or even death. The illegality meant that alcohol production was unregulated and therefore dangerous to human health. Prohibition was ultimately a failure. The stock market crash of 1929 and subsequent Great Depression left many people in severe economic (and mental) distress. It was repealed on December 5, 1933, with the ratification of the 21st Amendment, which specifically repealed the 18th. For many, the return of the ability to self-medicate with alcohol helped temper the despair of the Depression, although it likely ruined as many lives as it helped. But while romanticized notions of the "Roaring Twenties" continue today, we can learn from the problems that Temperance sought to solve. Absenteeism and incarceration both declined during Prohibition. Alcohol consumption overall did decline in the 20th century, thanks in large part to the Temperance movement. Today, more and more people are reassessing their relationship with alcohol. In 2006, food writer John Ore coined the term "Drynuary" to describe what he and his wife considered to be a post-holiday alcohol detox. "Drynuary" or "Dry January" has been embraced by an increasing number of people and while the peer pressure to consume alcohol in social settings still exists, it is becoming more acceptable to abstain in public. Are we on the brink of a new Temperance movement? Probably not, but interesting to see the historical parallels. As we are in full swing of "Dry January," and as more people are embracing temperance, we can look to the past for interesting non-alcoholic beverages to tempt our palates. The nice thing about having an extensive library is that it is easy to do research when I want to - I just head upstairs to my little office and library, tucked up under the eaves of our little house. I pulled a couple of 1920s cookbooks that revealed some fascinating recipes. Coffee and tea were the most common alcohol replacers in polite society, but a number of fruit-based beverages and punches were also popular. Of course, most of them are very heavy on the sugar. The rise of soda fountains in the 1900s was in part a direct response to Temperance - it was a wholesome place for young people, women, and families to meet and socialize. It also meant that many Americans were replacing the vice of alcohol with what we know today to be the vice of sugar. Good Housekeeping Book of Menus, Recipes, and Household Discoveries (1922)The first book I perused was not this one, but I thought I would start here because it is the oldest of the 1920s cookbooks I looked at and its recipes were among the most interesting. Good Housekeeping's Book of Menus, Recipes, and Household Discoveries was published in 1922. Don't these sound delightful? "Apple Tree Dulcet" in particular is a brilliant name, although it's much more of a dessert than a beverage. "Gingerade," made with fresh or "green" ginger root also sounds delightful, if spicy. Grapefruit PunchOf these I think the Grapefruit Punch sounded the most delicious. I love both grapefruit and maraschino cherries, but have never had them together. I often drink half grapefruit juice, half ginger ale as a bitter-sweet winter tonic. 2 cupfuls water 3/4 cupful sugar 1 cupful grapefruit juice 1/2 cupful grapefruit pulp juice of 1 lemon 1/4 cupful maraschino cherries mineral water Combine the water and sugar, boil one minute, and let cool. Meanwhile, extract the grapefruit juice and to this add the grapefruit pulp and the lemon-juice. Allow to chill thoroughly and then add the maraschino cherries cut in halves. Dilute with mineral ice-water and serve very cold. Westminster Church (Utica, NY) Cook Book (1924)I love collecting community cookbooks - the earlier the better. This particularly nice one from Utica, NY (which is also where I found it), has just one page of beverages. Published in 1924, it includes a homemade version of what was likely a soda fountain drink: Strawberry Flip. Note that it calls for only one TABLESPOON of vanilla ice cream. Per serving, of course. The one that seems the most interesting to me is the first Fruit Punch, by Bessie C.B. Capron. Fruit Punch1 cup sugar 1 cup very strong tea (black) 2/3 cup orange juice 1/3 cup lemon juice 1 pint ginger ale 1 pint appolinaris This makes enough for 10 glasses. Okay, this probably needs a little translation for most people. To make the tea very strong, steep 2-3 bags in one cup of boiling water. The orange and lemon juice should be fresh-squeezed. And the ginger ale is probably better if you can find something a little stronger than your garden variety - a craft ginger ale would do nicely. And appolinaris? That's a German type of sparkling mineral water. Known as the "Queen of Table Waters," Appolinaris was a brand name mineral water discovered in the 1850s that is still around today. Although these days it's owned by Coca-Cola. This recipe is actually somewhat similar to 18th century punches that called for sugar, citrus juices, black tea, and sparkling water, albeit with the addition of strong spirits like rum and brandy (see: Fish House Punch). Standard Cookbook - For All Occasions (1925)Marion Lockhart's Standard Cookbook is a teensy tiny little hard cover (hence the fingers to hold it open). Published in 1925, it has a wide variety of punches, which is lovely. I do love malted milk, but I'm wary of raw eggs, so the "Egg Malted Milk" is not one I would probably attempt. However, the "Currant and Raspberry Punch" sounds divine. Currant and Raspberry PunchTake 1/2 glass (about 3-4 ounces) currant jelly and dissolve in 1 cup boiling water. To this add 1 cup raspberry sirup and 1 pint fresh water. Pour over ice in punch-bowl, then add 1 quart charged (sparkling) water. This makes about 2 quarts and seems like the perfect pink party punch to serve for Valentine's Day or a girly party. Despite the syrup and jelly, it also probably isn't too sweet, as you're cutting about 1 pint of sweet stuff with 1 pint of water and a quart of sparkling water. New Delineator Recipes (1929)And last but not least! The New Delineator Recipes. Published in 1929, this one comes with a few quite lovely photos. "Reception Chocolate" looks delicious and would be perfect for a winter hygge party. "Veranda Punch" listed here is very similar to the "Fruit Punch" listed above. Of all of these recipes, "Grape High Ball" sounds the most interesting, in part because it uses Niagara grapes. If you live in the Northeast, you can still find both Concord and Niagara grapes at some U-Pick orchards. If you've never had Niagara grapes, I recommend trying them if you see them. A dusky golden color, neither they nor the classic deep purple Concords are much like today's table grapes. Niagara grapes are very soft, with slippery-sweet insides and seeds. But they have a lovely flavor - almost perfumed, and would make a sophisticated beverage. Niagara Grape High BallFor sake of ease, I am combining the two recipe instructions. Wash grapes and boil [until] skin, pulp, and seeds separate. Press through a jelly bag and to every pint of juice add one-half cup of sugar. Boil for twenty minutes and chill. In glasses half-filled with shaved ice, add equal parts syrup and charged (sparkling) water. Lemon is an attractive addition. Well, that's all for now folks. Are any of you attempting a Dry January? If so, what do you normally drink for festive occasions? Share in the comments!

And, as always, if you enjoyed this (long!) post, please consider becoming a member of The Food Historian! You can join online here, or you can join us on Patreon. Members get access to members-only sections of this website, special updates, plus discounts on future events and classes. And you'll help support free content like this for everyone. Join today! |

AuthorSarah Wassberg Johnson has an MA in Public History from the University at Albany and studies early 20th century food history. Archives

July 2024

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed