|

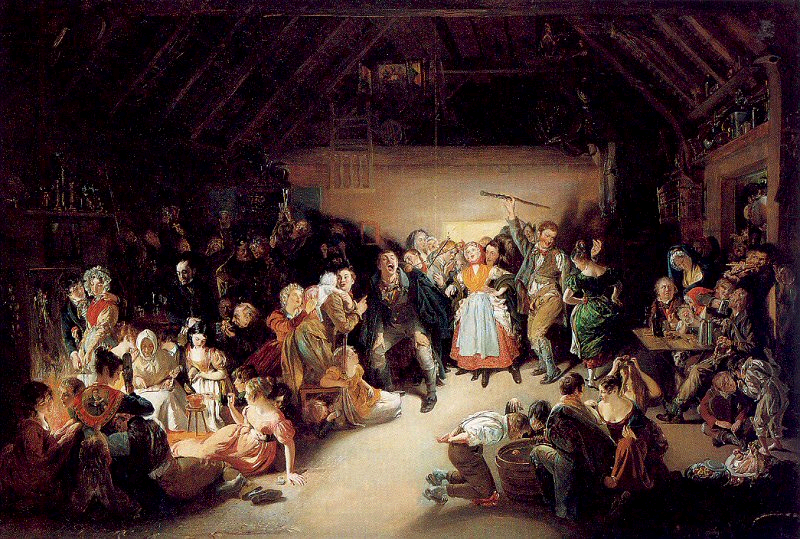

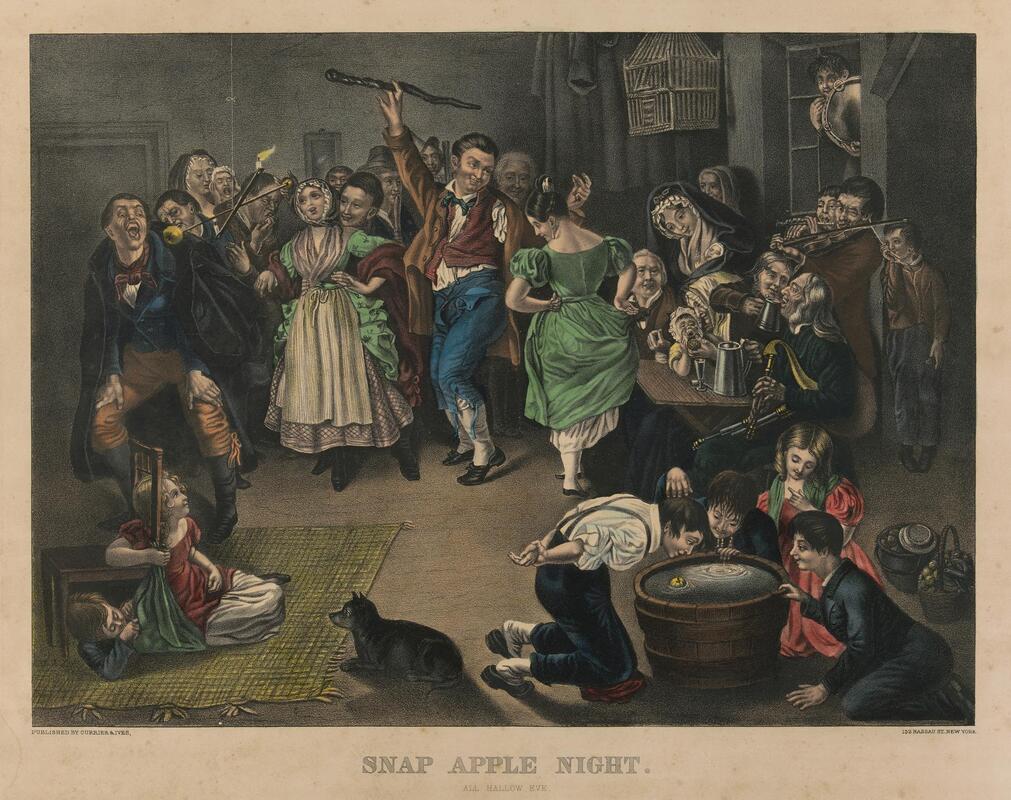

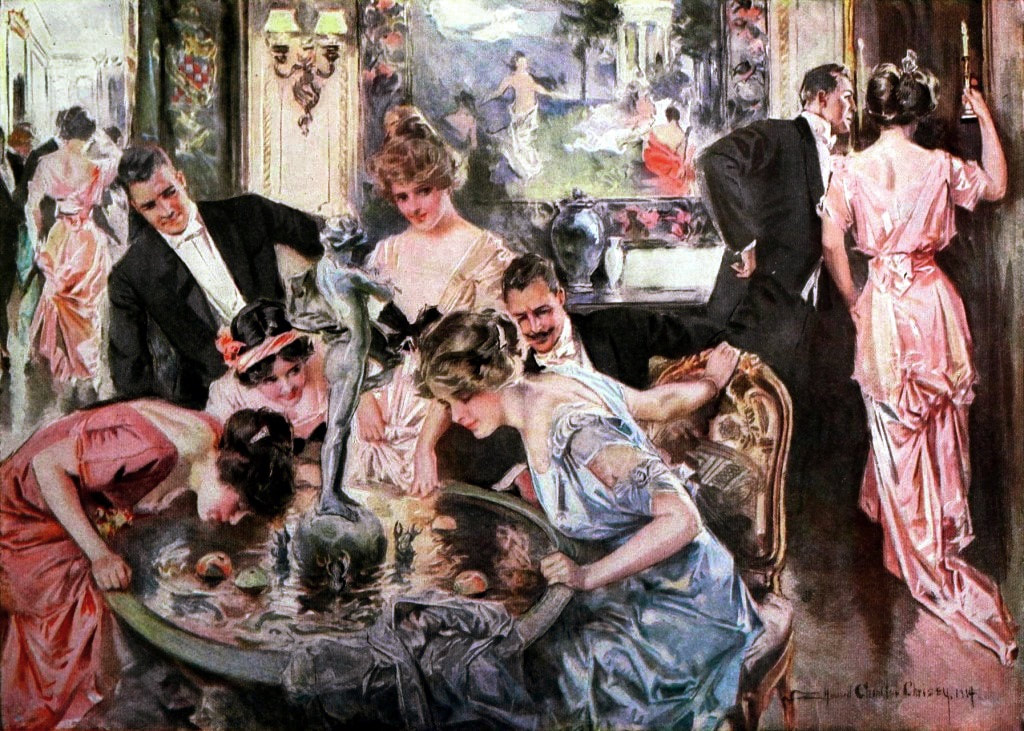

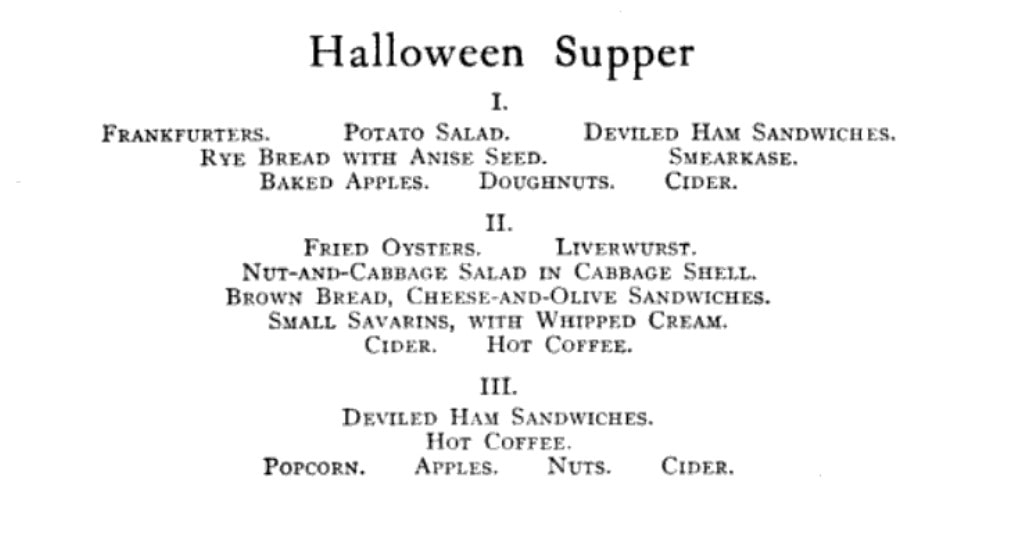

Welcome to The Food Historian's 31 Days of Halloween extravaganza. Between social media (Facebook, Instagram, Twitter) and this blog, I'll be sharing vintage Halloween content nearly every day this month! Happy Halloween, everyone! When it comes to Halloween, pumpkins get all the love. But Halloween's REAL favorite fruit is apples. Let me explain. The origins of Halloween date back to ancient Ireland and Scotland - a place where the now-ubiquitous pumpkin was not available until the 16th century at the earliest, and not really in practice until the 19th century. But apples? Apples were everywhere. They were the best fruit for storing over the long winters. Certain varieties kept better than others, but unlike soft berries or less sweet root vegetables, apples were a reliable source of sugar at a time when calories were all-important. 19th and early 20th century historians often attributed the apple celebrations of the British Isles to Pomona, the Roman goddess of fruit orchards, including apples, which in Romance languages share the Latin root word "pomum," meaning fruit. "Apple" was also originally meant to describe all kinds of fruits, not just the Malus domestica, much like "corn" historically referred to all types of grain (and which is why most of the rest of the world refers to it as "maize.") I'm skeptical of the direct connection to Pomona. More likely was simply the fact that apples were in season at this time of year. Apple harvest generally lasts from August through the end of October, depending on the breadth of your apple varieties. Apples were eaten fresh, put up as sauce or apple butter, dried, and processed into apple cider, hard cider, scrumpy, applejack, and apple cider vinegar. But for Halloween, fresh apples were still very common, and a LOT of Halloween traditions involve fresh apples. Snap Apple NightIn Ireland, Halloween was often referred to as "Snap Apple Night," as is illustrated by the classic painting above by Irish artist Daniel Maclise. Maclise based it on a real Halloween party he visited in Ireland in 1832. He illustrates many of the classic traditions. At left, a courting couple burns nuts on the hearth grate to see how their relationship will fare and girls drip molten lead into water to read their fates in the shapes. At right, boys bob for apples and others play pranks on the musicians. And the center, namesake of the painting, is snap apple - a rather precarious and hilarious game. A pair of wooden sticks are fastened together into a cross. On two opposing ends, the sticks were sharpened and apples stuck on. On the opposite ends, burning candles were affixed. The whole thing was hung from the ceiling on a string, and set spinning. The goal was to catch and remove the apple using only your mouth - no hands allowed - without getting hit in the face by a burning candle, or the hot wax. Upon exhibition, Maclise's painting was accompanied by the following poem: There Peggy was dancing with Dan While Maureen the lead was melting, To prove how their fortunes ran With the Cards could Nancy dealt in; There was Kate, and her sweet-heart Will, In nuts their true-love burning, And poor Norah, though smiling still She'd missed the snap-apple turning. As Irish immigrants came to the United States following the great potato famine of the 1840s, they brought their Halloween traditions with them. This rather poorly rendered lithograph by Currier & Ives is a copy of a copy of Daniel Maclise's original painting. Printed in 1853, it reflected the adoption of Halloween by Americans. Missing the divination happening hearthside, this lithograph focuses on the game of snap apple, the dancing and music, and in the foreground, bobbing for apples. This image from the frontispiece of The Book of Hallowe'en, published in 1919 by Ruth E. Kelley, shows the staying power of Maclise's painting, and the power of the mysterious history of Halloween. In this illustration, ("from an Old English print"), we have bobbing for apples and a well-lit game of snap apple. The clothing of the people in the illustration evokes somewhere between the turn of the 19th century and the 1840s - the fuzziness of the time period part of the mystique of the book, which purports to trace the history of Halloween and yes, does link it to the Roman festivals for Pomona. Kelley's book was part of a resurgence of interest in Halloween throughout the United states, and one of a number of books published on the subject, including more serious histories like hers, and more commercial publications like Dennison's Bogie Books. Snap apple remained a popular game, although later versions were slightly safer. As the century wore on and we turned to the 20th century, alternatives went from attaching the apples with strings, to replacing the candles with small sacks of flour (far less dangerous than flame and hot wax, but no less humiliating to get hit in the face with a puff of flour), and eventually simply hanging apples from a string. An even easier later variation even replaced the apples with donuts! As Halloween traditions shifted from at home parties to public events like costume parades and community trick or treating, snap apple faded into obscurity. History of Bobbing for ApplesThe above painting is one of my favorites from the time period. Howard Christy's "Halloween" depicts a very fancy Progressive Era Halloween party that still smacks of the Gilded Age. The decadent mansion, with enormous Classical paintings, gilded furniture, and elaborate gaslights is filled with men in tuxedoes and sleek haircuts and women in glistening silks and satins - nary a fancy dress costume in sight. In the foreground a fancy Classical style fountain has a few apples floating in it, and one young lady bends close - contemplating bobbing, perchance? - while others look on. In the background, a young woman and a man gaze into a mirror - the woman holds a lit taper candle, which evokes the Halloween divination tradition of gazing into a dark mirror by candlelight at midnight. Supposedly your future husband would appear. It's a slightly ridiculous take on the historically very messy and hilarious tradition of bobbing for apples. Like snap apple, bobbing for apples (sometimes known as dunking or ducking for apples), was a game of hilarity, skill, and danger. A large basin - often the wooden laundry basin - was filled with water and apples floated on top. The object of the game was to retrieve them with only your mouth - hands behind your back. There were a number of tricks to retrieve them. Some tried to grab the stem in their teeth. Others used their lips to suction the side of the apple. Still others shoved their entire heads under water, trying to trap the apple between their mouth and the bottom of the basin. Like with snap apple, courting couples could cooperate to sandwich an apple between them. And like snap apple, bobbing for apples drifted into obscurity as the 20th century wore on, although it remained more firmly in the American cultural consciousness than snap apple.  This undated postcard, likely from the turn of the 20th century, features two girls and a boy bobbing for apples. It's one of the few images of the period showing a girl actually doing the bobbing while the other two watch. A smoking jack o'lantern typical of the period sits in the foreground. Toronto Public Library collection. Apple Divination In this 1909 Halloween postcard by illustrator Bernhardt Wall, a young woman is tossing a long apple peel over her shoulder, believing that the peel will fall to the floor in the shape of a letter that will reveal the first letter of her future husband's name. Posted by collector Alan Mays to Flickr. Like May Day and Midsummer, Halloween was chock full of divination opportunities, and apples were at the center of several. The more famous is apple peel divination. A young girl would peel an apple in a long strand - sources vary over whether she had to do the whole apple in one unbroken peel - and toss the peel over her shoulder. Supposedly, the peel would land in the shape of the initial of the man she was to marry. In practice it seems like there would be a lot of S's, C's, L's, and O's, and not too many T's or H's. Another romantic divination game involved the apple seeds. Pressing fresh seeds to your forehead you would assign to each one a crush or romantic interest. The one that stayed on the longest was destined to be yours. Still other apple seed games involved squeezing them in your fingers. The direction they shot out of your fingers was where your true love would approach from. Candy and Caramel Apple HistoryAlthough apples were consumed regularly in the autumn months in northern climes all over the world, it wasn't until the late 19th century that the modern apple as we know it today developed. Starting post-Civil War, fruit orchardists like the Stark Brothers and agricultural college experimental stations began developing specific varieties of fruit, grafted for taste, disease resistance, ripening time, etc. With these scientific developments came the emergence of the modern dessert apple. Designed for eating, rather than for producing cider, these apples were sweeter than their predecessors. Apples, through improvements in orchard husbandry, were also getting larger, more standardized, and shipped better. People in cities were able to access fresh apples on an increasing basis. Which led to innovations in eating. Candying fruits in sugar or honey syrup is ancient. But the idea of dipping fresh apples in a candy coating was relatively new. Candy apples are coated in a shiny red candy glaze, whereas caramel apples are dipped in sticky brown caramel. Taffy apples are somewhere in between. Toffee apples, as they are called in England, are similar to both. Although candy apples are widely attributed to William Kolb of New Jersey in 1908, but toffee apples and caramel apples have newspaper references in England and France in the 1890s. Also in 1908, one newspaper article for "Caramel Apples" went viral - appearing in 62 newspapers across the country. It is not quite the same as the caramel apples we associate with today, which are more similar to British toffee apples of a sour apple dipped in soft caramel. These were more like a combination of the medieval candied apples and modern caramel apples, with nary a stick in sight. Here's the article in its entirety: CARAMEL APPLES ARE GOOD. As you can see from the recipe, these apples must have been incredibly sweet as they were both cooked in syrup and then also covered in caramel and more syrup and served with whipped cream. No wonder the sugar addicts of 1908 made this recipe go viral! Caramel and candy apple associations with Halloween come a bit later, coinciding with the apple harvest season. Most Americans connect them to county fairs and old-fashioned trick-or-treating, when people still made homemade treats to distribute before the candy scares of the 1970s. Today, they're found everywhere from pick-your-own apple orchards to places like Coldstone Creamery, although most are now dipped in chocolate, rather than caramel or candy, as getting a candied coating that is thick enough to stick and soft enough not to break your teeth is a bit of a lost art. Chocolate is far easier to handle. Apple Cider For Halloween MenusAlthough the Pumpkin Spice latte may have taken over fall in today's world, in my opinion apple cider is a much better companion. And historic cooks and party planners agreed. Apple cider was often featured in Halloween menus like the ones above from the late Victorian period on. This would have been sweet cider, of course, because even before Prohibition most home economists and domestic scientists were advocates of the Temperance movement. Whether served cold or spiced, cider was often associated with other more casual foods like doughnuts, popcorn, frankfurters (aka hotdogs), pickles, and nuts. Outdoor events like bonfires, hay rides, and outdoor parties along with public events where children or teenagers were present were also commonly associated with simpler foods like outlined in the menus above. The prevalence of cider reveals its more industrial origins. Apple orchards growing dessert apples were more prevalent, as older heirloom cider apples fell out of use. Commercial bottling in the mid-19th century allowed companies like Martinelli's to produce hard cider and sodas. The growing popularity of the Temperance movement shifted companies away from hard cider and toward unfermented sweet cider, which remains the focus of Martinelli's today. Companies like Mott's also started out making hard cider, and then shifted to sweet in the 20th century as bottling sanitation improved and the demand for non-alcoholic beverages increased. Today, most commercially-sold apple juice is filtered and pasteurized, making for a thinner-bodied, sweeter, and less acidic product. Apple cider is generally not filtered and is sometimes sold unpasteurized, as the acidity level gives it anti-microbial properties. This, along with the sugar content, is generally also what allows apple cider to ferment, rather than spoil. Today, most hard cider is inoculated with champagne yeast, but historically wild yeast would naturally gather in the sugary liquid. Sweet cider is available most places where apples are grown, and New York is the second-largest apple-producing state in the country, so I'm lucky to have ample access to it. I've even made my own with a historic cider press! (Just a small, household sized one, not one of the giant presses.) In all, apples take the cake (sometimes literally) in Halloween eats in large part because they were a readily available source of sugar a time when refined cane sugar was largely the purview of the wealthy. And besides which, although pumpkin pie was also associated with Halloween, there's only so much of it you can eat before you get sick of it. Apples - whether candied and carameled or turned into pie, salads, cakes, muffins, crisps, dumplings, sauce, butter, cider, or even candy - are tough to get sick of, especially after a long, hot summer. What do you thing - do apples beat out pumpkins for ideal Halloween eats? Or should we be celebrating other fruits altogether, like pears or blackberries? Edwardian HalloweenAs I was working on this post, I was watching BBC's Edwardian Farm (which is also available on Amazon Prime - using the link helps support The Food Historian). Episode 2 is great to watch in its entirety (lime burning, apple cider pressing, and egg preservation, oh my!), but I've started the YouTube video below at the beginning of the Halloween party, where you'll see a variation of snap apple, an apple divination game involving sticking apple seeds to your forehead, and of course, fermented apple cider. Enjoy, and have a happy, apple-ish Halloween! The Food Historian blog is supported by patrons on Patreon! Patrons help keep blog posts like this one free and available to the public. Join us for awesome members-only content like free digitized cookbooks from my personal collection, e-newsletter, and even snail mail from time to time! Don't like Patreon? Leave a tip!

0 Comments

Your comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

AuthorSarah Wassberg Johnson has an MA in Public History from the University at Albany and studies early 20th century food history. Archives

July 2024

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed