|

Yesterday I went to visit the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York City. I had not been in many years, and I've never seen the whole thing. It was enormous and full of priceless artifacts. But.

Most of those artifacts were displayed apart from their historical and cultural context. The labels were sparse. The introductions often non-existent. Some of the exhibit cases resembled a robber baron's garage sale, with objects arranged and labeled with little or no relation to each other. Undefined terminology and jargon strange even to a veteran historian with a Master's degree popped up often. To be honest, much of the museum smacked of gatekeeping. There's a lot of gatekeeping in academia. Some folks are so insecure in their abilities that excluding others makes them feel important. Others are so wrapped up in the minutiae of their studies they forget that the outside world does not share their frames of reference. Still others were raised to think of themselves as more talented, more intelligent, more deserving than others, and these folks seem to think that a gate protects them. Having been raised in a more egalitarian, middle-class, Scandinavian-American household, I dislike gatekeeping. And jargon. And, frankly, anything or any action that seeks to exclude others and hide knowledge for a select few. To quote the great Steve Rogers, "I don't like bullies. I don't care where they're from." I realized today that I had been partially participating in that gatekeeping, albeit unwittingly. As with many online content creators, I was told that monetization was the way to go. And for folks who make their livings full-time at this sort of thing, that makes sense. But that won't be me until I retire, and I'm in a much better place financially now than I was ten years ago when I started this website. As of today, I will no longer charge a membership fee to access any part of my website, nor will I provide members-only content, nor will I ask for memberships at the bottom of every post. Existing Patreon patrons will have the option to continue their memberships to help pay for the upkeep of this website and my email service. Substack has always been free and I've been clear from the get-go that folks who become paid members won't be getting anything special in return. And folks can always leave a tip, if they're so inclined. But while my time is now much more limited than it was when I started this website nearly 10 years ago, my coffers are far less bare. So I've decided it's time to throw open the gates and share the metaphorical wealth. Thanks to some help from volunteer Elissia, you can now access dozens (hundreds?) of free public domain cookbooks, organized into a vintage cookbook bibliography. It's a work-in-progress, but there's quite a lot there to explore. You can also now read my thesis free of charge, along with other publications, and download printable themed newsletters previously only available to members. They're all listed under the "resource" tab on my website. Eventually, I'll update the bibliography with more recent publications. I'll also be recycling some previously members-only blog posts on the public blog in the coming weeks, months, and years. I have a dozen or more brand new blog posts waiting in the wings, so I hope to be able to carve out more time to finish them sometime soon. I've also made some progress on the book, and I hope to be able to spend more time on it in the coming months. If I have time, I'll send periodic updates on that as well. When I started this website in 2015, I had just finished my Master's thesis and had realized the depths of my interest in food history more generally. This website has become a place for me to share primary sources, consolidate ideas, and even engage in the occasional rant from time to time. I've been inspired by reader and listener questions, internet memes, and my own exciting discoveries. The blog and this website aren't going anywhere anytime soon. I'm proud of how often thefoodhistorian.com shows up in search results - my tiny contribution to internet mythbusting in a sea of misinformation and badly researched history. So whether you've had a paid membership via Substack or Patreon, you've attended one of my talks or read an article, or whether you subscribed to this website on a curious whim, thank you for your support. It's time to return the favor. Go forth and enjoy, dear readers, the gates are open. Happy food historying!

0 Comments

During the Second World War, food preservation became a national mandate. I've featured canning-related propaganda posters before, but I thought now would be a good time to feature a few of the lesser-known posters. The above poster is from fairly late in the war. It reads "Grow More, Can More... In '44 - Get your canning supplies now! Jars, Caps and Rings." A special seal featuring a hand (presumably Uncle Sam's) holds a basket containing the words, "Food Fights for Freedom" with "Produce and Conserve" and "Share and Play Square" above. It features a rosy-cheeked young woman in an overtly feminized take on the Women's Land Army overalls, a straw hat tilted fashionably far back on her head, and wearing spotless white work gloves. With a hoe tucked in one elbow and a thumb in her overall strap, she gestures with her free hand at an enormous set of glossy clear glass canning jars, expertly filled with whole tomatoes, halved peaches, green beans, sliced red beets, and what might be whole apricots, yellow plums, or yellow cherries, it's tough to tell. The jars feature a variety of lids, including the new aluminum screw-tops, a glass-topped wire bail with a rubber seal, and a zinc screw top with a rubber seal, illustrating the range of canning technologies still in use. The poster is photorealistic and is probably a literal cut-and-paste of actual photographs - a new technique in an era still dominated by illustrations. It's not clear exactly when this poster was released, but it's likely it was early in the season. The poster exhorts the reader to "grow more" in addition to canning more in 1944, which seems to indicate a spring release, despite the prominence of the large glass canning jars. In addition, the poster warns to stock up on canning supplies now, instead of later in the season. When aluminum was short and factories that made glass were used to produce war materiel, it was easier to make smaller quantities over a longer period of time. By planning ahead, home gardeners and canners could also make sure they had enough supplies on hand to handle an increase in garden produce. Things were getting a bit desperate in 1944 - the war was not going well and the prospect of another long year of war was troubling to ordinary Americans. Rationing had ramped up fully in 1943, and as the war dragged on home canned foods took on more importance in everyday nutrition. For many, especially children, the war must have seemed unending. Little did they know that on June 6, 1944, the United States would launch Operation Overlord - also known as the invasion of Normandy - which would become known as D-Day. D-Day would turn the tide of the war in favor of the Allies, but it would still take another fifteen months for the war to end entirely. Until then, rationing continued and Americans were urged to grow and preserve as much food as they could to supplement their rations. The war finally ended in September of 1945, and by December, rationing of every food except sugar had ended. Foods canned in 1944 would have been important support for rations, but foods canned in 1945 would have been less crucial. One wonders how many home canned foods made it to the end of 1946? We may never know. The Food Historian blog is supported by patrons on Patreon! Patrons help keep blog posts like this one free and available to the public. Join us for awesome members-only content like free digitized cookbooks from my personal collection, e-newsletter, and even snail mail from time to time! Join now for as little as $1/month.

Don't like Patreon? Leave a tip! This post contains Amazon affiliate links. Happy Valentine's Day, dear readers! I'm not typically one for Valentine's Day (although I've written about it here and here), but this year we decided to celebrate a friend's birthday with a Valentine's Day-themed tea party! I will admit the idea started with cute pink tea cups, spoons, and tea bag rests I saw at Target, and it kind of snowballed from there. But if you've been a longtime reader you'll know how much I enjoy designing and putting on tea parties (see: here, here, and here). I have an addiction to vintage dishes and linens, so it only seems fair that I drag them out every now and again. This tea party does not have any particular historical recipes attached to it, although every time I throw one I feel I am following firmly in the footsteps of my home economics predecessors, many of whom enjoyed a themed party even more than I do. Designing Your Tea PartyHalf the fun of throwing parties is dreaming them up and bringing together all the various accoutrements that make it nice. I've mentioned the pink teacups and saucers, golden flower spoons, and heart-shaped tea bag rests already. Those were the catalyst. But I also pulled from my collection of vintage pretties, all of it thrifted: a cherry blossom tablecloth, my favorite lace-edged milk glass platter and coordinating dessert plates, a gold-edged glass platter and coordinating luncheon plates, gold-rimmed etched highball glasses, vintage martini glasses, a beautiful cut glass footed compote I picked up recently, and one of my many milk glass vases for two bunches of fresh tulips. I did splurge on a few more things - I got some cute Valentine's Day decorations; a garland of felt hearts for the living room and a table runner for the coffee table. A set of heart-shaped cookie cutters in a variety of very useful sizes. My favorite purchase was a set of beautiful pink glass nesting bowls rimmed in gold. We only used one bowl for the tea party, but I love them so much. And the one that got the most comments was this rose-shaped ice cube tray, which turned grapefruit juice into gorgeous icy roses. I probably could have used more, but much of my milk glass got put away last Christmas and is now up under the eaves. One of my spring cleaning projects is to organize all my totes of spare dishes and decorations and put them all in the more easily-accessible basement, clearly labeled, so I can find things and use them more often. If you are in search of your own tea party collection, my best advice is to buy what you love, and damn the naysayers. My second-best advice is to buy things that coordinate with a variety of themes. Which is why I love milk glass so much, because it knows no season, and white dishes can always be spruced up with special touches of color. What every tea party needs:

Of course the most important ingredient for a tea party is at least one guest! Tea parties are always better with conversation. Menu planning is also a great deal of fun for me, and I love the challenge of coming up with something new each time I throw a party, alongside tried-and-true recipes. For this party, the tried-and-true recipe was for my Russian-style pie crust, which was used for both the savory pie and the letter cookies. The new was the vegetarian "chorizo," which was a riff on my lentilwurst recipe, and which turned out VERY well! The vegetable flower pie I knew would work in theory, but the execution was more difficult than I expected. If I did it again, I would definitely want a Y-style vegetable peeler like this one for the sweet potatoes. Valentine's Day Tea Party MenuFIRST COURSE: Savory Vegetable Flower Pie Heart Shaped "Chorizo" Sandwiches Hot Pink Salad SECOND COURSE: Strawberry Rhubarb Pie a la Mode Love Letter Cookies Red Fruit Salad BEVERAGES: Ice water Grapefruit Mocktail Cherry Blossom or Valentine's Day Tea Sadly my time these days is far more limited than it used to be, so my dreams of an almond cake with rose petal jam filling, lavender shortbreads, rose meringues, and other tasty treats fell victim to my schedule. Still, although some of these were a struggle, I was delighted in how they turned out. Normally I would make these separate posts, but for you, I'll lump all the recipes into one. The only thing that was store bought was the pie, which was purchased from a local farm who makes the best pies. And since our birthday girl loves pie more than cake, that was her birthday treat, in addition to the homemade ones. Savory Vegetable Flower Pie RecipeThis flavor combination sounds unusual, but it's delicious. Crust: 1 stick butter 1/4 pound fresh ricotta or farmer cheese 1 cup flour Filling: 1 cup ricotta 1/2 cup feta garlic salt dried thyme Topping: sweet potato small shallots roasted red pepper Preheat oven to 350 F. Cream softened butter and ricotta, then stir in 1 cup flour. Knead well and let rest. Whirl the ricotta and feta to blend and then add seasonings. Peel the sweet potato and cut into paper-thin slices. Peel the shallots cut off the tops, and then cut through them lengthwise but not through the root end. Cut multiple times to make "petals." Then trim the root end without cutting all the way through. Roll the dough out thinly and drape in a pie plate. Fill with ricotta filling, then arrange sweet potato slices into roses, add the shallots and spread the "petals," and then fill any extra spaces with slices of roasted red pepper rolled into rosebuds. Trim pie crust and crimp. Use remaining crust to cut out "leaves" and bake separately. Bake pie 30-40 mins or until sweet potatoes and shallots are cooked through and crust is golden brown. Vegetarian Lentil "Chorizo" RecipeThis recipe is a riff off my lentilwurst revelation. It turned out splendidly. 1 cup red lentils 1 1/2 cups water 1/4 cup butter (or olive or coconut oil) 1 small onion 1 red bell pepper 2 teaspoons smoked paprika 1 teaspoon chili powder 1 teaspoon garlic powder 1/2-1 teaspoon garlic salt 1/2 teaspoon oregano 1/4 teaspoon cumin 1/4 teaspoon black pepper Combine the lentils and water in a small stockpot. Bring water to a boil, then reduce heat and simmer 20ish minutes, or until the water is absorbed and the lentils are very soft. Peel the onion and seed the pepper, then mince very finely or whirl in a food processor until finely cut. In a stock pot, melt the butter over medium heat and add the onion and pepper. Cook until the butter is mostly absorbed and the vegetables very tender. Add the spices and lentils and cook to combine. When fully blended, taste and add more salt if needed. To make sandwiches, thinly slice white bread and cut into heart shapes, then spread with the lentil filling. Pink Salad RecipeI like to have something a little lighter for tea parties, usually a salad. But of course for Valentine's Day I didn't want any-old green salad! Plus, one of the challenges I set for myself was to keep this at least partially seasonally-appropriate. So this was my answer. 1/4 head red cabbage 8 red radishes 1/4 cup pickled red onion salt olive oil lemon juice Finely shred the cabbage and slice the radishes paper-thin. Toss with salt and let rest, then add a little olive oil and lemon juice. You can make this in advance if you want it to be extra-pink and slightly less crunchy, but be forewarned that the purple juices will stain just about everything, so eat carefully! Love Letters Cookie RecipeI'll admit - I saw this on Pinterest and thought it was too cute. I used my fool-proof ricotta pie crust instead of traditional butter crust, and while delicious, the letters did puff up a bit in the oven. Plus those little hearts are a pain to cut out by hand! 1 stick (1/4 cup) butter 1/4 pound ricotta or farmer cheese 1 cup flour cherry jam (I like Bonne Maman) Cream butter and ricotta and stir in flour. Knead well until combined. Roll out very thin and cut into squares. Place a teaspoon of jam in the center, then fold up one side and the other two to make an envelope. Add a heart cut out of crust to keep the edges from popping up. Bake at 350 F on parchment paper for 15-18 minutes, or until golden brown. Grapefruit Mocktail RecipeThis is one of my favorite mocktail recipes and it is dead easy, you ready? 1 part grapefruit juice 1 part gingerale And that's it! I like to use Simply Grapefruit, as I think it has a nice balance of sweetness and bitterness, but you could use any kind. The combination tastes so much more sophisticated than it is - not too sweet, not too bitter, not too bubbly, and curiously addictive for the adult palate. For folks who don't drink alcohol, it's a great alternative to a mixed drink that isn't sugary-sweet. Selecting TeasTea parties traditionally feature just black tea, but as a non-traditional person and someone who doesn't enjoy a lot of caffeine, I don't usually drink black tea. However, since this was a special event, I decided to bring out some special teas just for Valentine's Day. Harney & Sons is a New York-based tea producer (and therefore local for me) who makes delicious blends. I did a big order last year around this time and got their "Valentine's Day" blend for free. I was skeptical at first, but it's a delicious blend of black tea, chocolate, rose, and other fruity flavors. Curiously addictive. The birthday girl is a big fan of green tea, so when I saw the Cherry Blossom variety, which is a mix of green tea with cherry and vanilla flavors, I decided to get that as well. Both were excellent and did not need any sweetener or milk to accompany the rest of the menu. All in all it was a delightful afternoon. The birthday girl was happy, the husband was happy, and I was happy! We went for a post-party walk in delightful weather and did a little shopping at a nearby town, got caught in a rainstorm, then headed for home. Later that night we ran some more errands and I treated myself to some adorable jigsaw puzzles, because they remind me of my mom and I need some non-screen time activities! They've been fun, but man my back is not up for too much hovering over a table searching for pieces!

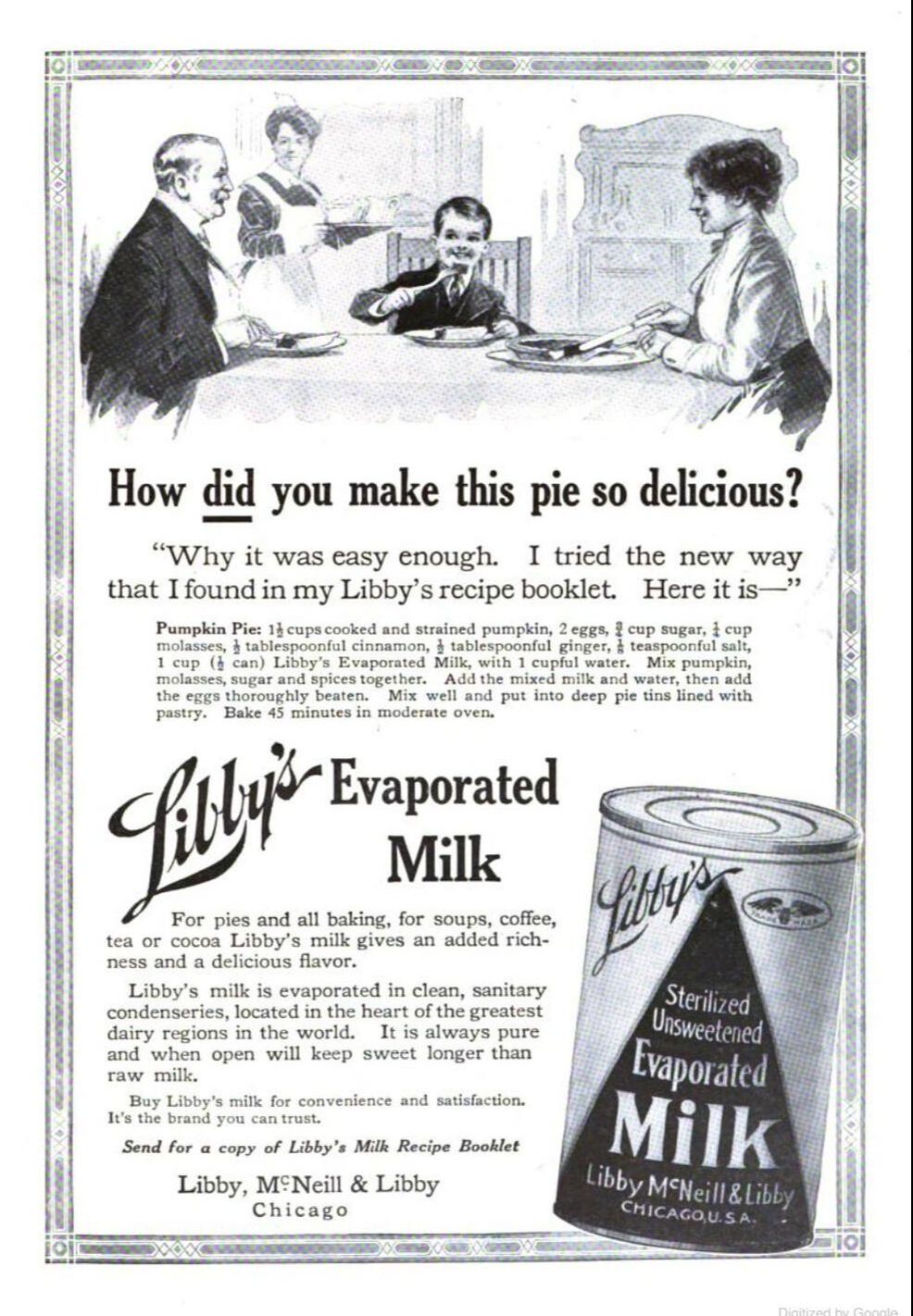

It always gives me joy to built a beautiful table for family and friends. My best Valentine's Day present to myself! How are you celebrating? Libby's pumpkin pie is the iconic recipe that graces many American tables for Thanksgiving each year. Although pumpkin pie goes way back in American history (see my take on Lydia Maria Child's 1832 recipe), canned pumpkin does not. Libby's is perhaps most famous these days for their canned pumpkin, but they started out making canned corned beef in the 1870s (under the name Libby, McNeill, & Libby), using the spare cuts of Chicago's meatpacking district and a distinctive trapezoidal can. They quickly expanded into over a hundred different varieties of canned goods, including, in 1899, canned plum pudding. Although it's not clear exactly when they started canning pumpkin (a 1915 reference lists canned squash as part of their lineup), in 1929 they purchased the Dickinson family canning company, including their famous Dickinson squash, which Libby's still uses exclusively today. In the 1950s, Libby's started printing their famous pumpkin pie recipe on the label of their canned pumpkin. Although it is the recipe that Americans have come to know and love, it's not, in fact, the original recipe. Nor is a 1929 recipe the original. The original Libby's pumpkin pie recipe was much, much earlier. In fact, it may have even predated Libby's canned pumpkin. In 1912, in time for the holiday season, Libby's began publishing full-page ads using their pumpkin pie recipe in several national magazines, including Cosmopolitan, The Century Illustrated, and Sunset. But the key Libby's ingredient wasn't pumpkin at all - it was evaporated milk. Sweetened condensed milk had been invented in the 1850s by Gail Borden in Texas, but unsweetened evaporated milk was invented in the 1880s by John B. Meyenberg and Louis Latzer in Chicago, Illinois. Wartime had made both products incredibly popular - the Civil War popularized condensed milk, and the Spanish American War popularized evaporated milk. Libby's got into both the condensed and evaporated milk markets in 1906. Perhaps competition from other brands like Borden's Eagle, Nestle's Carnation, and PET made Libby's make the pitch for pumpkin pie. Libby's Original 1912 Pumpkin Pie Recipe:The ad features a smiling trio of White people, clearly upper-middle class, or even upper-class, seated around a table. An older gentleman and a smiling young boy dig into slices of pumpkin pie, cut at the table by a not-quite-matronly woman. A maid in uniform brings what appears to be tea service in the background. The advertisement reads: "How did you make this pie so delicious?" "Why it was easy enough. I tried the new way I found in my Libby's recipe booklet. Here it is - " "Pumpkin Pie: 1 ½ cups cooked and strained pumpkin, 2 eggs, ¾ cup sugar, ¼ cup molasses, ½ tablespoonful cinnamon, ½ tablespoonful ginger, 1/8 teaspoonful salt, 1 cup (1/2 can) Libby’s Evaporated Milk, with 1 cupful water. Mix pumpkin, molasses, sugar and spices together. Add the mixed milk and water, then add the eggs thoroughly beaten. Mix well and put into deep pie tins lined with pastry. Bake 45 minutes in a moderate oven. "Libby’s Evaporated Milk "For all pies and baking, for soups, coffee, tea or cocoa Libby’s milk gives an added richness and a delicious flavor. Libby’s milk is evaporate din clean, sanitary condenseries, located in the heart of the greatest dairy regions in the world. It is always pure and when open will keep sweet longer than raw milk. "Buy Libby’s milk for convenience and satisfaction. It’s the brand you can trust. "Send for a copy of Libby’s Milk Recipe Booklet. Libby, McNeill & Libby, Chicago." My research has not been exhaustive, but as far as I can tell, Libby's was the first to develop a recipe for pumpkin pie using evaporated milk. Sadly I have been unable to track down a copy of the 1912 edition of their Milk Recipes Booklet, but if anyone has one, please send a scan of the page featuring the pumpkin pie recipe! Curiously enough, the original 1912 recipe treats the evaporated milk like regular fluid milk, which was a common pumpkin pie ingredient at the time. Instead of just using the evaporated milk as-is, it calls for diluting it with water! The recipe also calls for molasses, and less cinnamon than the 1950s recipe, which also features cloves, which are missing from the 1912 version. Both versions, of course, call for using your own prepared pie crust. Nowadays Libby's recipe calls for using Nestle's Carnation brand evaporated milk - both companies are subsidiaries of ConAgra - and Libby's own canned pumpkin replaced the home-cooked pumpkin after it purchased the Dickinson canning company in 1929. Interestingly, this 1912 version (which presumably is also in Libby's milk recipe booklet) does not show up again in Libby's advertisements. Indeed, pumpkin pie is rarely mentioned at all again in Libby's ads until the 1930s - after it acquires Dickinson. And by the 1950s, the recipe wasn't even making the advertisements - Libby's wanted you to buy their canned pumpkin in order to access it - via the label. The 1950s recipe on the can persisted for decades. But in 2019, Libby's updated their pumpkin pie recipe again. This time, the evaporated milk and sugar have been switched out for sweetened condensed milk and less sugar. As many bakers know, the older recipe was very liquid, which made bringing it to the oven an exercise in balance and steady hands (although really the trick is to pull out the oven rack and then gently move the whole thing back into the oven). This newer recipe makes a thicker filling that is less prone to spillage. Still - many folks prefer the older recipe, especially at Thanksgiving, which is all about nostalgia for so many Americans. I'll admit the original Libby's is hard to beat if you're using canned pumpkin, but Lydia Maria Child's recipe also turned out lovely - just a little more labor intensive. I've even made pumpkin custard without a crust. Are you a fan of pumpkin pie? Do you have a favorite pumpkin pie recipe? Share in the comments, and Happy Thanksgiving! The Food Historian blog is supported by patrons on Patreon! Patrons help keep blog posts like this one free and available to the public. Join us for awesome members-only content like free digitized cookbooks from my personal collection, e-newsletter, and even snail mail from time to time! Don't like Patreon? Leave a tip!

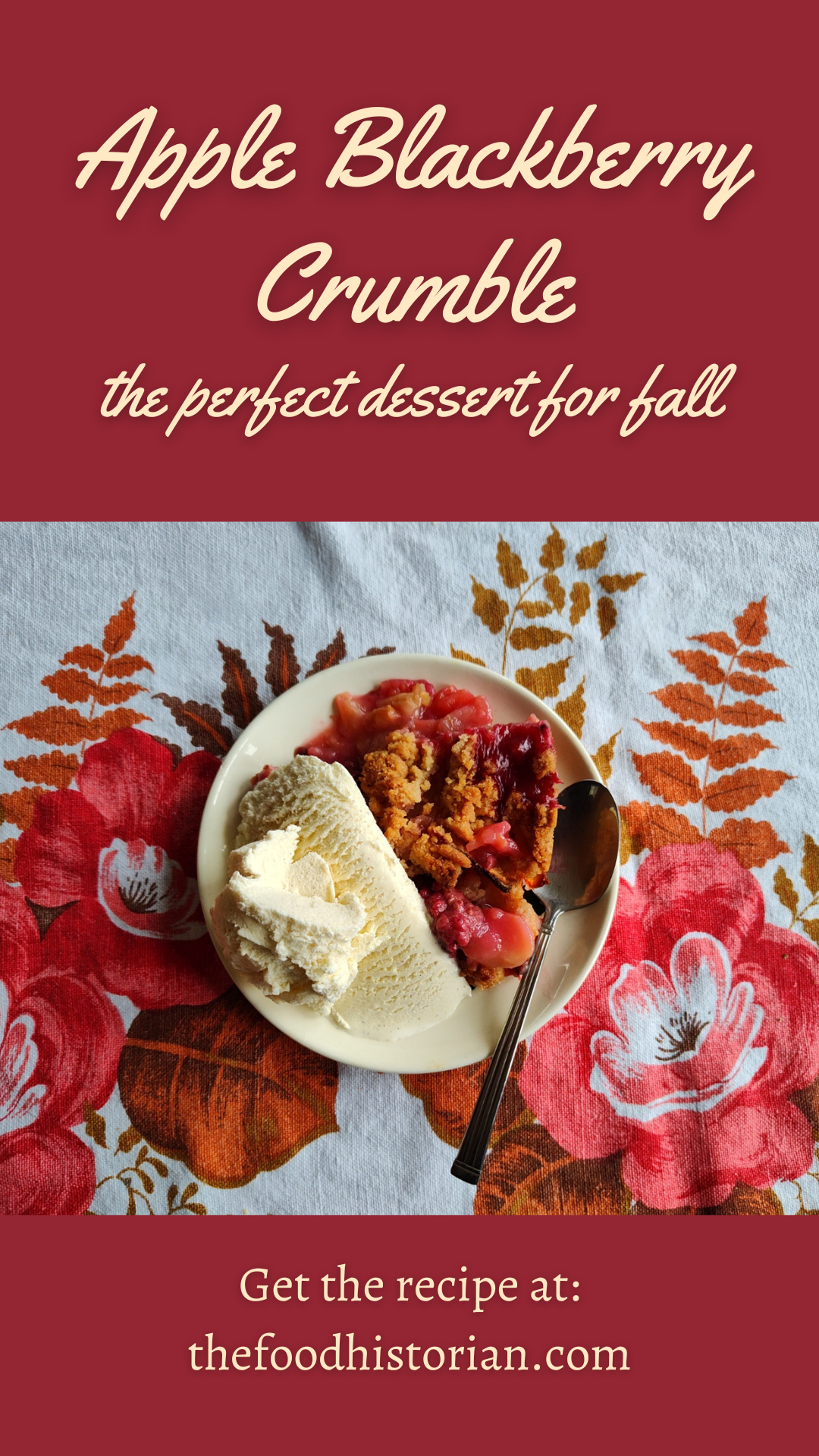

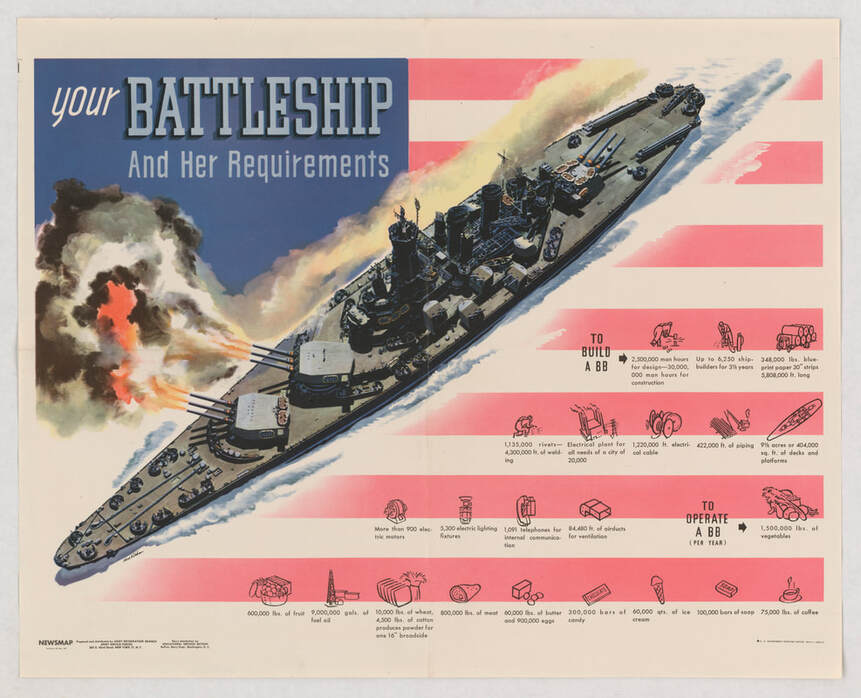

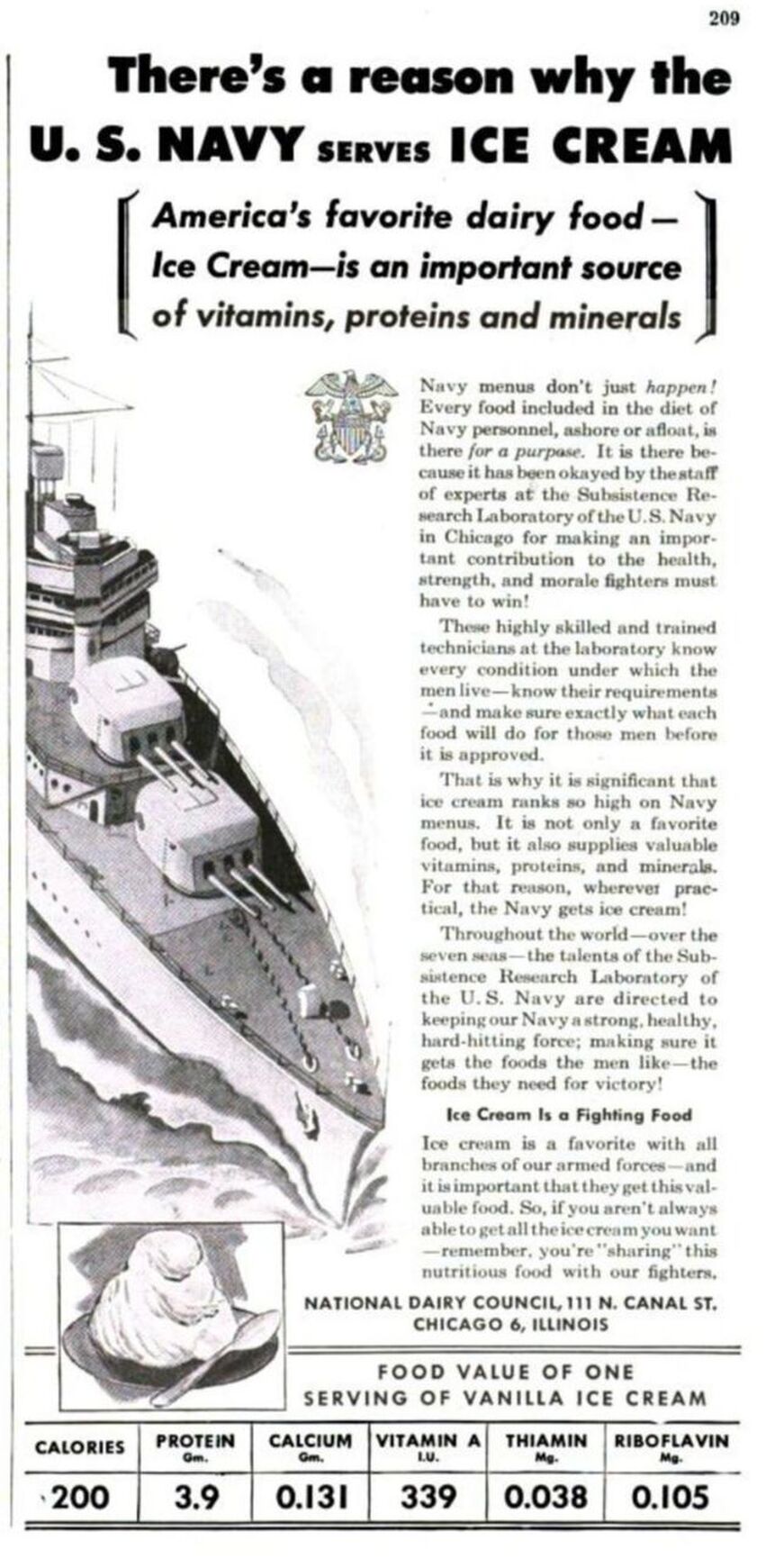

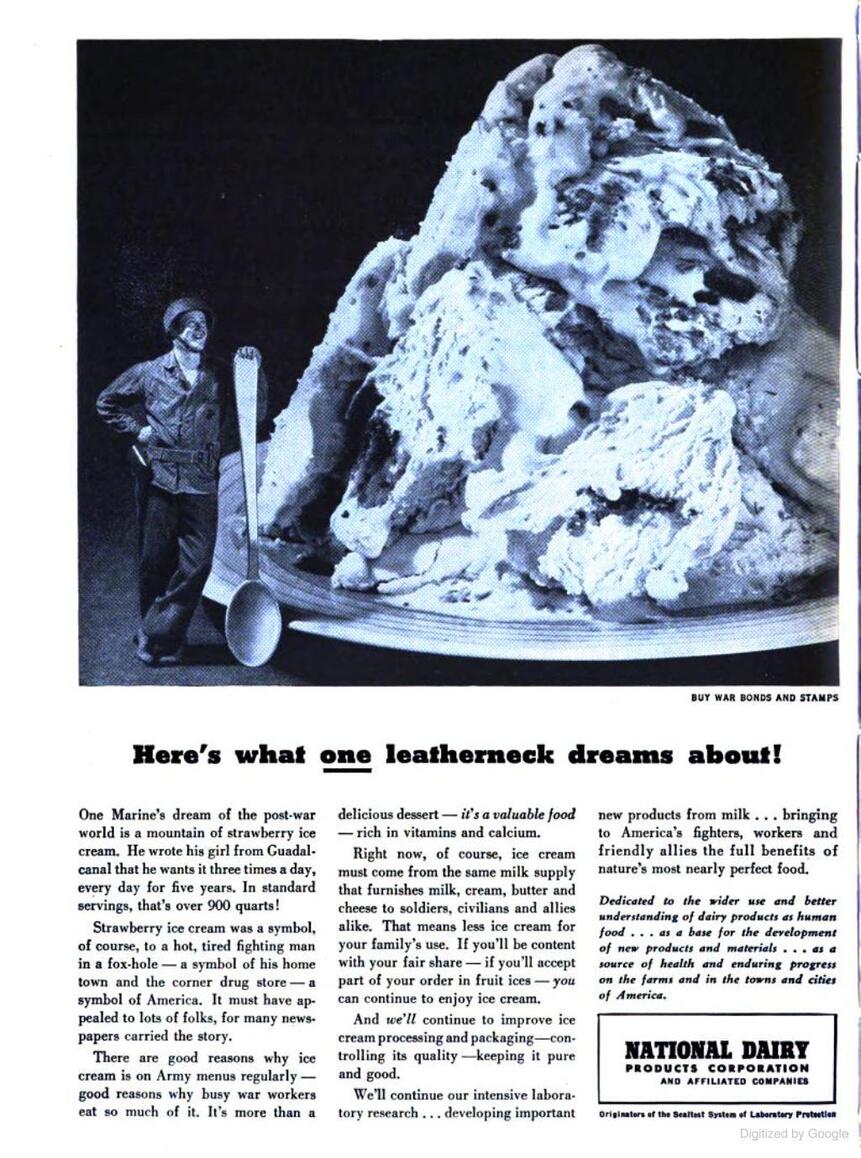

In throwing an Autumnal Tea Party (see yesterday's post!), I wanted a simple but impactful dessert. Apples are plentiful in New York in September, but plain apple crisp, while delicious, didn't feel quite special enough for a tea party. The British have a long tradition of gleaning from hedgerows in the fall. Hedgerows often have apple trees, sloes, blackcurrants, and blackberries in fall. Sloes and blackcurrants are hard to find here in the US, but blackberries seemed like the perfect accent to the American classic. This recipe is endlessly adaptable as the crumble topping is great with any kind of fruit. You do need quite a lot of fruit for a crumble, which makes it nice in that it feels a little lighter on the stomach than cake or pie. These sorts of desserts were common in areas where fruit was plentiful and sugar and butter weren't. Apple Blackberry Crumble RecipeI never sweeten the fruit for a crumble (similar to a crisp, but without rolled oats) unless it is a very sour fruit like rhubarb or fresh cranberries. This topping has quite a lot of sugar, which is what helps make it so crunchy and delicious, but you definitely do not need additional sugar in the fruit, especially when pairing with ice cream. You can substitute whole grain flour for part or all of this to good effect as well. If you prefer a crisp, use 1/2 cup of flour and 1 heaping cup of rolled oats. 8+ small apples (I used a mix of gingergold and gala) 1 pint (2 small packages) fresh blackberries 1 1/2 cups all-purpose flour (plus more for the fruit) 1 scant cup white sugar 1/2 cup coldish butter 1/2 teaspoon salt 1/2 teaspoon pumpkin spice Preheat the oven to 400 degrees F. Peel the apples, cut into quarters, cut out the core, and slice. Wash the blackberries and drain. Toss the apples and blackberries with flour to coat (this will thicken the juices). Add to the baking dish. Then make the crumble. Mix the flour, sugar, salt, and pumpkin spice. Then cut the butter into small cubes, toss in the flour mix, and using your hands squeeze and rub it into the flour mix until it holds together when squeezed. Crumble gently over the fruit in an even mix, then bake for 40-50 minutes, or until the fruit is bubbly and thick and the crumble is golden brown. Serve warm with vanilla ice cream. There's nothing like a warm crisp with cold vanilla ice cream, and I think this is my new favorite kind. Blackberries and apples seem like a match made in heaven. What's your favorite autumnal dessert? The Food Historian blog is supported by patrons on Patreon! Patrons help keep blog posts like this one free and available to the public. Join us for awesome members-only content like free digitized cookbooks from my personal collection, e-newsletter, and even snail mail from time to time! Don't like Patreon? Leave a tip! The weather has finally turned, dear readers, and so I felt it was time for another tea party! I've had a long couple of weeks, and I wasn't really looking forward to spending one of my days off cleaning the house and cooking, but it was very much worth the effort and I'm glad we did it. Tea parties can be incredibly complicated, or very simple. My process is to think about the theme, and the flavors, and then come up with way too many ideas and then pare it down to what's possible. I wanted to honor the flavors of early fall, with something pumpkin or squash, apples, blackberries, and a savory bread. My original list also had gingerbread and shortbread cookies with jam, and scotch eggs, but that was too much! I wanted to keep the menu fairly simple, because I was quite sleep deprived after a big event over the weekend at work. So I maximized flavor and minimized effort, to great acclaim! The party (just three of us) ended up delicious, with a chilly, drizzly day with beautiful overcast light on our front porch. Ironically, we ended up having mulled cider, instead of tea, but I'm enjoying a cup of tea as I write this a few hours later, so I suppose it still counts! Autumnal Tea Party DecorIt can be tempting to go out and buy a lot of supplies for parties. I'm definitely as susceptible to that impulse as the next person! But I find what makes parties special is not how much everything matches, but the quality of your decor. I decorated my mantel with some of my favorite fall decorations - a coppery leaf garland, my favorite vintage china pheasant, a pretty vase with some fake flowers, a little green ceramic pumpkin. But when it comes to decking the table, nothing is better than nice tablecloth and real dishes. I grew up shopping thrift stores and garage sales and flea markets with my mom, so I've amassed quite a collection of vintage dishes and tablecloths over the years. Because I actually use my collection, I don't spend a lot of money on it. It pains me enough when a vintage piece gets chipped or broken. My frugal soul would be even more deeply wounded if it was a piece I had spent a lot of money on. This ended up being a very grandmother-focused display. The Metlox California ivy plates and a single surviving teacup I inherited from my grandmother Eunice, along with the green glass bowl I used for butter and the green glass saucers. My grandma Ruby found me the beautiful etched water glasses. The glass teacups embossed with leaves I picked up at a garage sale for a dollar for the pair. The milk glass is from my thrifted collection, and the beautiful tablecloth is a vintage one I forget where I found but it's probably one of my absolute favorites. I did not intend for the food to match the tablecloth, but that's kind of how it happened! When it comes to collecting, it's important to buy things you love, instead of focusing on what things are worth. Who cares how expensive it was if you think it's ugly? It's also important to choose things that are relatively easy to care for. I do not recommend putting vintage dishes in the dishwasher, but a lot of vintage tablecloths are meant to be washed. I find vintage textiles with a stain or two are often much less expensive than the pristine stuff, and then if you get a stain on them you don't feel quite so bad! Autumnal Tea Party MenuButternut Squash Soup with buttered pecans Sage Cream Biscuit Sandwiches with pickled apple, pickled onions, and sharp cheddar Dilly Beans Mulled Cider Blackberry Raspberry Hibiscus Water Apple Blackberry Crumble with vanilla ice cream Although I love to cook from scratch, the butternut squash soup was store-bought from one of my favorite soup brands: Pacific Foods Butternut Squash Soup, and I got the low-sodium version (affiliate link). I don't usually like butternut squash soup, but I know lots of people love it, so I thought I would give it a go. This one was so delicious, I was surprised how much I enjoyed it. I felt it needed a little something extra, so I toasted some chopped pecans in a little butter and salt, and the butter got a little browned. It was the perfect garnish. The blackberry raspberry hibiscus water was also store-bought, a simple cold water infusion from Bigelow tea which I found at the store the other day (affiliate link). It turned out lovely - not as strong as tea, just a hint of flavor to cold water. Very refreshing. Sadly, the color, which was a beautiful purple as it steeped, got diluted to a kind of washed purple-gray, which was less beautiful. But still delicious! Sage Cream BiscuitsI had thought about making scones for this tea party, but I don't have a reliable savory scones recipe, and since I was doing sandwiches, I thought biscuits would be better. This is an adaptation of my tried-and-true Dorie Greenspan cream biscuit recipe. It's almost fool-proof. This one is doubled. 4 cups of all-purpose flour 2 tablespoons baking powder 2 teaspoon sugar 1 1/2 teaspoons salt 1 heaping teaspoon dried sage (not ground) 2 1/2 cups heavy cream Preheat the oven to 425 F. Whisk all the dry ingredients together, and then add the heavy cream, tossing with a fork until most of the flour is absorbed. Knead gently with your hands (don't overwork!), then pour out onto a clean, floured work surface and knead, folding often, until it comes together. Pat into a large rectangle and cut into squares. Place on a parchment-lined baking sheet and bake 15-20 minutes or until golden brown. Serve warm, and to make the sandwiches, split the biscuits, butter them, and add sliced sharp cheddar cheese, a slice of pickled apple, and a few strands of pickled red onion. Top with more cheddar and the other half of the biscuit and devour. Serve with butternut squash and a side of dilly beans and mulled cider. I'll be following up with the recipe the apple blackberry crumble tomorrow, and the recipes for refrigerator dilly beans, pickled apples, and pickled onions will be available to patrons on my Patreon tomorrow as well. Do you like to have tea parties? What's your favorite autumnal food? The Food Historian blog is supported by patrons on Patreon! Patrons help keep blog posts like this one free and available to the public. Join us for awesome members-only content like free digitized cookbooks from my personal collection, e-newsletter, and even snail mail from time to time! Don't like Patreon? Leave a tip! Last World War Wednesday, we looked at the use of ice cream in the U.S. Navy during the First World War, especially aboard hospital ships. Now it's time for a reprise! By the Second World War, ice cream was firmly entrenched aboard Naval vessels. So much so, that battleships and aircraft carriers were actually outfitted with ice cream machinery, and by the end of the war the Navy was training sailors in their uses through special classes. The above propaganda poster, courtesy the National Archives, outlines all of the requirements to build a battleship. "Your Battleship and Her Requirements" may have been targeted toward factory workers, but I think it is more likely this poster was designed to impress upon ordinary Americans the extraordinary amount of materials and supplies needed to keep a battleship in fighting trim. What I found particularly interesting, was that among the supplies listed, alongside fruits and vegetables and meat and even candy, was 60,000 quarts of ice cream! Smaller vessels, such as destroyer escorts and submarines, did not have the space for their own ice cream making machinery, although they did have freezers. In fact, it became common for destroyer escorts and PT boats to rescue downed pilots (the aircraft carries were too big for the job) and "ransom" them for ice cream. Last week a brand new food podcast debuted for American Public Television called "If This Food Could Talk," and I'm so pleased to say I was featured in the first episode, "Frozen in Time: Ice Cream and America's Past." I had a blast doing the research for that episode's interview, which has inspired these two recent World War Wednesday posts. Have a listen if you want to learn more about ice cream in American history, and especially the story of ice cream in the Navy. But while I was doing the research, I kept running across references to ice cream as a health food! The National Dairy Council really leaned into the notion of ice cream and the armed forces. This advertisement reads, "There's a reason why the U.S. Navy serves Ice Cream. America's favorite dairy food - Ice Cream - is an important source of vitamins, proteins and minerals." The ad goes on: "Navy menus don't just happen! Every food included in the diet of Navy personnel, ashore or afloat, is there for a purpose. It is there because it has been okayed by the staff of experts at the Subsistence Research Laboratory of the U.S. Navy in Chicago for making an important contribution to the health, strength, and morale fighters must have to win! "These highly skilled and trained technicians at the laboratory know every condition under which the men live - know their requirements - and make sure exactly what each food will do for those men before it is approved. "That is why it is significant that ice cream ranks so high on Navy menus. It is not only a favorite food, but it also supplies valuable vitamins, proteins, and minerals. For that reason, wherever practical, the Navy gets ice cream! "Throughout the world - over the seven seas - the talents of the Subsistence Research Laboratory of the U.S. Navy are directed to keeping our Navy a strong, healthy, hard-hitting force; making sure it gets the foods the men like - the foods they need for victory! "Ice Cream Is a Fighting Food "Ice cream is a favorite with all branches of our armed forces - and it is important that they get this valuable food. So fi you aren't always able to get all the ice cream you want - remember, you're 'sharing' this nutritious food with our fighters." The National Dairy Council might be just a SMIDGE biased in this regard, but certainly the federal government ranked milk, and by extension milk products, very highly in terms of nutrition during the Second World War, notably as part of the Basic 7 nutrition recommendations. This was almost certainly a holdover from the Progressive Era's take on milk as the "perfect food" - combining proteins, carbohydrates, and fats all in one. We see this in another advertisement, this time by the National Dairy Products Corporation. The National Dairy Council is an industry-funded research and marketing organization. But the National Dairy Products Corporation would later become Kraft Foods. "Here's what one leatherneck dreams about! "One Marine's dream of the post-war world is a mountain of strawberry ice cream. He wrote his girl from Guadalcanal that he wants it three times a day, every day for five years. In standard servings, that's over 900 quarts! "Strawberry ice cream was a symbol, of course, to a hot, tired fighting man in a fox-hole - a symbol of his home town and the corner drug store - a symbol of America. It must have appealed to lots of folks, for many newspapers carried the story. "There are good reasons why ice cream is on Army menus regularly - good reason why busy war workers eat so much of it. It is more than a delicious dessert - it's a valuable food - rich in vitamins and calcium. "Right now, of course, ice cream must come from the same milk supply that furnishes milk, cream, butter and cheese to soldiers, civilians and allies alike. That means less ice cream for your family's use. If you'll be content with your fair share - if you'll accept part of your order in fruit ices - you can continue to enjoy ice cream. "And we'll continue to improve ice cream processing and packaging - controlling its quality - keeping it pure and good. "We'll continue our intensive laboratory research... developing important new products from milk... bringing to America's fighters, workers and friendly allies the full benefits of nature's most nearly perfect food." Here you can see the "perfect food" rhetoric in action! And interestingly, this one touts the role of ice cream in the Army as well. In my opinion ice cream, for all the rhetoric about nutrition, had far more to do with morale than anything else. But there is some truth to the idea that as a dessert it was superior to cake or pie. For one thing, ice cream does have some protein, in addition to a decent amount of fat. Full fat dairy is generally proven to be more filling and satisfying and protein and fat slow down the absorption of sugar directly into the bloodstream, making the "energy-giving" properties of carbohydrates longer-lasting and less likely to make you crash (unlike cake and cookies). That being said, viewing ice cream as a health food is questionable today. But in the period, the discoveries of vitamins and minerals like calcium were cutting-edge, and any food containing those essential nutrients was considered good for you. Ice cream also fit neatly into ideas (unconscious or otherwise) of White supremacy and American (i.e. Anglo-Saxon) culture. As the National Dairy Products Corporation marketing team wrote, ice cream was "a symbol of America." When combined with soda fountains (the wholesome, if sugary, alternative to saloons and beer halls), ice cream seemed to represent the best of America - slim, good-looking, young, White America, that is. Today, ice cream's modern accessibility has given us ice cream alternatives aplenty, especially for folks who can't consume dairy. Ice cream's ubiquity has also meant some of its luster has faded. But at a time of extreme stress - the violence of the theater of war, the privations of home front rationing, the push to mobilize for total war, the fear of invasion - ice cream provided a moment of bliss in the midst of uncertainty. Ice cream is still an essential tradition aboard Naval vessels today. When you're miles from home for months at a time, anything that seems like a treat gives morale a boost. It's still a treasured treat in our household, whether homemade or store bought (if you find yourself in upstate New York - do yourself a favor and seek out Stewart's Shops. They have the best commercial ice cream around). What does ice cream mean to you? The Food Historian blog is supported by patrons on Patreon! Patrons help keep blog posts like this one free and available to the public. Join us for awesome members-only content like free digitized cookbooks from my personal collection, e-newsletter, and even snail mail from time to time! A special patrons-only post is coming tomorrow with more on ice cream in World War II - this time featuring Elsie the Cow! Join now for as little as $1/month.

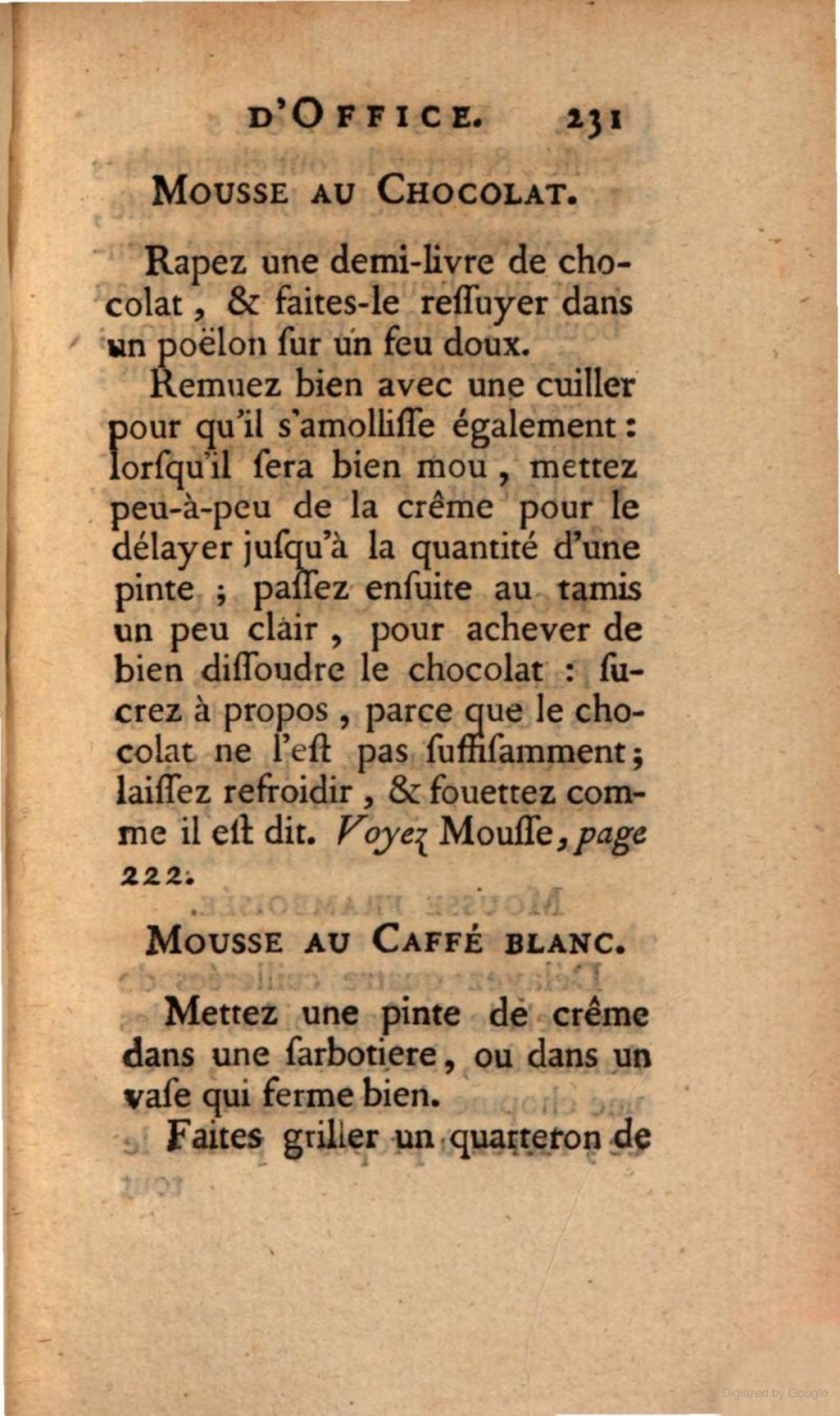

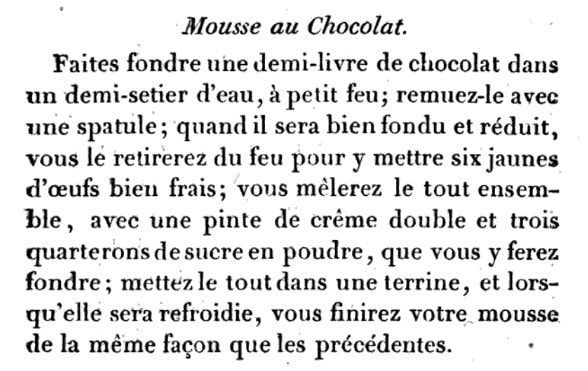

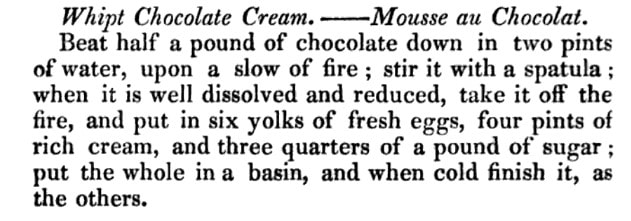

Don't like Patreon? Leave a tip! Dear Reader, I finally did it, and not in a good way. A few weeks ago I hosted a beautiful (albeit hot and humid) French Garden Party, a belated celebration of Bastille Day, for approximately 30 people. The decorations were gorgeous and the food was fabulous and I did not take a single. solitary. photograph. My consternation was extreme. My beautiful screen porch was set with tables dressed in blue and white striped linens. It was BYOB - bring your own baguette, and folks brought fancy cheeses to go with the goat cheese and paper-thin ham I provided. I made homemade mushroom walnut pate and TWO compound butters - fresh herb and garlic, and lemon caper. I made beautiful French salads: potato and green bean vinaigrette, lentils vinaigrette with shallot and parsley and a hint of fresh rosemary, cucumber with tarragon and sour cream, celery with black olives and anchovies, peach basil. We had honeydew melon and both sweet dark AND Queen Anne cherries. We had wine and spritzers a-plenty. A friend brought chocolate cream puffs. I made lemon pots de crème and earl grey madeleines. But the absolute star of the show was this chocolate mousse, which I flavored with rose water. And since I had one little glass pot left over from the party, I snapped a few photographs a few days later to give you the incredibly easy recipe so that you, too, may feature this glorious star, and have your guests talking about it for days afterwards (no really - they did). But course, I wouldn't be a food historian if I didn't give you a little context, and I was curious about the history of chocolate mousse, so here you go: A Brief History of Chocolate MousseGoodness there is a lot of nonsense out on the internet about chocolate mousse! Way, WAY, too many sources say it was invented by Toulouse Lautrec, and that it was called "mayonnaise de chocolat." People. Chocolate mousse dates back to at least the 18th century, if not earlier, so it was around long before Monsieur Lautrec. I did, to my surprise, find a couple of recipe references to "mayonnaise au chocolat." It sounds so ridiculous as to be fake, but this was apparently a real recipe, albeit a name I can only date to the 20th century. One recipe is from a 1909 French cookbook, which calls for melting chocolate with egg yolks and adding beaten egg whites, and offers a clue to the name: it says at the end to mix the egg whites and the chocolate mixture "like ordinary mayonnaise." A few references in the 1920s and '30s, and then where it was probably popularized in America - a reference from a 1940 issue of Gourmet magazine (not readable online, alas - if anyone tracks down a hard copy of the original, let me know!). Another recipe is from a 1951 French cookbook, with not very detailed directions. According to my translation, "mayonnaise au chocolat" mixes melted chocolate with egg yolks and a few tablespoons of cream which is then cooked and then mixed with egg whites (unclear whether or not they are beaten stiff or not, but likely yes) and chilled. Another is from the 1961 edition of Mastering the Art of French Cooking by Julia Child and Simone Beck, which has a recipe for "Moussline au Chocolat, Mayonnaise au Chocolat, Fondant au Chocolat" (yes, three names for the same recipe!) the subheading of which reads "Chocolate Mousse - a cold dessert." Mousseline is actually a sauce mixed with whipped cream (for instance, you can turn hollandaise sauce into a mousseline by adding whipped cream), whereas mousse is a thickened chilled dessert made with whipped cream. The Julia Child recipe conflates the two, and her recipe calls for an egg yolk cooked custard mixed with melted chocolate, with whipped egg whites folded in. It is then served with crème anglaise or whipped cream. So, none of these recipes are truly chocolate mousse, because the mixtures contain no whipped cream whatsoever. But Toulouse Lautrec and a crazy-to-Americans name like "chocolate mayonnaise" is so much more dramatic than doing actual historical research and looking at primary sources. SIGH. People. We can do better. The earliest references to "chocolate mousse" I could find date to 1687 and refer to the habit of Indigenous peoples in Central America of frothing their chocolate beverages with either a mollinio or by pouring them between cups. A habit which Europeans apparently adopted. A 1701 French dictionary continues the reference to frothy chocolate beverages in its definition of "mousser" or "to foam." The earliest reference I could find to the dessert mousse we know and love today comes from the 1768 French cookbook, "L'art de bien faire les glaces d'office ou les vrais principes pour congeier tous les rafraichissemens" or The Art of Making Ice Cream Well, or the True Principles for Freezing All Refreshments. And lest you think it is just about ice cream, the extremely long title adds, "Ave Un Traite Sur Les Mousses," or "With A Treatise On Mousses." Chocolate mousse (as pictured above) is simply one of dozens of mousse recipes listed, but the early versions are quite similar to the modern. Grate the chocolate and melt it in a saucepan over low heat, then add cream, little by little, to thin it down. Pass it through a sieve, sweeten it, and then let cool and whisk to a foam. By the 19th century, we're adding egg yolks to make a smoother, more custard-y base, as you can see from this pair of recipes by early French restauranteur Antoine Beauvilliers, who published his 1814 "The Art of Cooking" as a French cookbook that became foundational to generations of French chefs and home cooks. English cooks, however, had access before that, judging by this 1812 recipe, which also called for egg yolks. We're still adding large amounts of whipped cream, though, keeping in classic mousse style. It took a bit longer for Americans to adapt to chocolate mousse, although they were prodigious chocolate drinkers, and certainly by the mid-19th century were consuming chocolate custards and ice creams. It wasn't really until (as far as I and the Food Timeline can tell) celebrity cookbook author and cooking school teacher Maria Parloa intervened that it got popular. The Food Timeline cites a 1892 article with Miss Maria Parloa lecturing on chocolate mousse, among other things, but I found a reference dating back to 1885 where she's lecturing on chocolate mousse in Buffalo, NY. However, it doesn't seem to be QUITE the same as we consider chocolate mousse today. Her 1887 recipe for it calls for freezing it like ice cream, albeit without stirring. Regardless of whether the recipe calls for egg yolks or not, or whether it's frozen or not, chocolate mousse in the modern style is easier to make than you'd think. Chocolate Rose Mousse RecipeA French Garden Party called for something easy to prepare and delicious for dessert. Because it was a garden party, I decided on chocolate pots de crème or mousse flavored with rose fairly early on. I used to dislike floral flavors, but after making an Egyptian rosewater dessert last year, and trying Harney & Sons seriously divine Valentine's Day tea, which was chocolate black tea with rosebuds (affiliate link), I was smitten. After realizing how many eggs I'd go through making a triple batch of both lemon AND chocolate pots de crème, I decided to do just the lemon (15 pots) and do the rest as chocolate mousse (15 pots). I found these adorable little glass pots with covers on Amazon, should you care to purchase them yourself from this affiliate link. I adapted several recipes online, and since I didn't want to mess with steeping the cream with rosebuds or rose petals or any other options, I decided to go the less expensive and way easier rose water direction. Rose water is used frequently in Middle Eastern cooking, and is often less expensive in the "ethnic" section than in the spice aisle. In preparing for the party, in which I was attempting a brand new recipe, I didn't want to try to mess with egg yolks any more than I already had to with the lemon pots de crème (which turned out only okay). So the simple mixture of heavy cream, dark chocolate, and a little icing sugar seemed best. I then added rose water to taste, which turned out about perfect. Here's the reasonable-serving recipe, which I tripled to get 15 generous servings for the party. This makes more like 6 servings, 4 if you're being greedy. 1 1/2 cups heavy cream (I used a local dairy brand, which is richer than national brands) 1 cup high-quality dark chocolate chips (like Guittard) 1/4 cup powdered sugar 1 teaspoon rose water Heat a saucepan of water over medium heat, bringing it to a simmer. Place a heat-proof bowl (glass or metal) over the simmering water and add 3/4 cup heavy cream and the chocolate chips. Stir gently until the chocolate chips are completely melted. Remove from heat. In a large bowl, beat the remaining 3/4 cup heavy cream until you get soft peaks, then add the 1/4 cup powered sugar and beat until you get stiff peaks. Add the rose water and beat to combine. 1 teaspoon should be enough to stand up to the chocolate, but taste the whipped cream. The rose water should be present, but not overpowering. If faint, add another 1/2 teaspoon and beat again. Then, using a ladle, add approximately 1/3 cup of the cooled chocolate-cream mixture to your whipped cream, one ladle at a time, and gently fold to combine using a rubber spatula. To fold, use the spatula to cut down the center of the whipped cream mixture and scrape up from the bottom. Rotate the bowl slightly, and repeat the action, until the chocolate is incorporated. Add another ladle of chocolate and continue until you have folded in all of the chocolate without totally deflating the whipped cream. Spoon into small glass jars or custard cups and refrigerate until ready to serve. It was so gorgeous. Light but rich, with a subtle hint of rosewater, which added fascinating depths to the chocolate. Folks gobbled it all up, and it was by far the best dessert of the party. The one lonely little pot left allowed me to take the above photo the following day, so you're welcome! I didn't serve it with whipped cream during the party, and it's admittedly a little overkill, but it does look pretty. So now you have the recipe AND some history, plus some food history mythbusting! So do yourself a favor and go splurge on some high-quality ingredients and treat yourself and your loved ones to this easy and stunningly delicious dessert. To quote Julia, quoting the French, Bon Appetit! The Food Historian blog is supported by patrons on Patreon! Patrons help keep blog posts like this one free and available to the public. Join us for awesome members-only content like free digitized cookbooks from my personal collection, e-newsletter, and even snail mail from time to time! Don't like Patreon? Leave a tip!

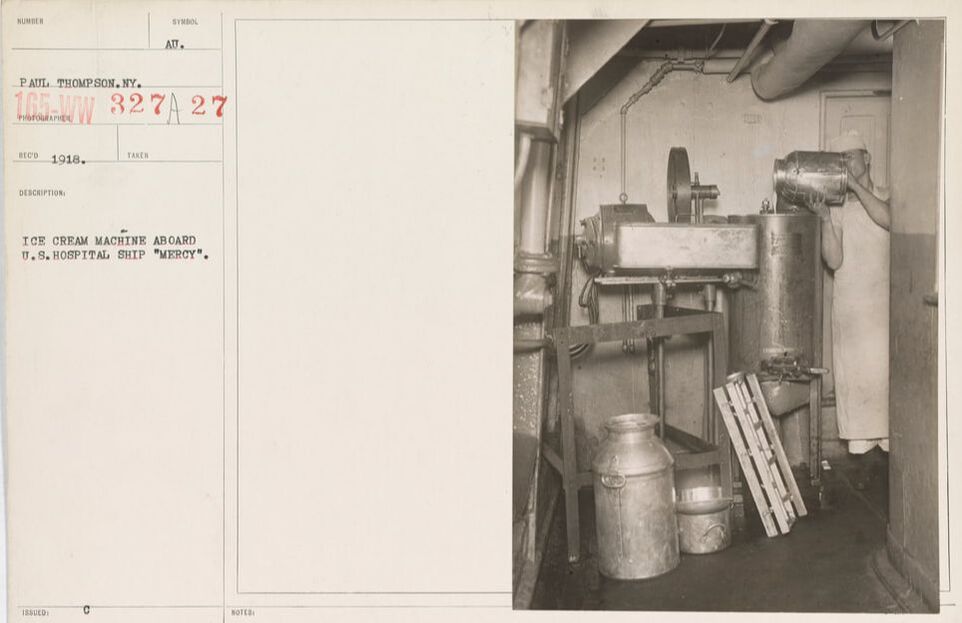

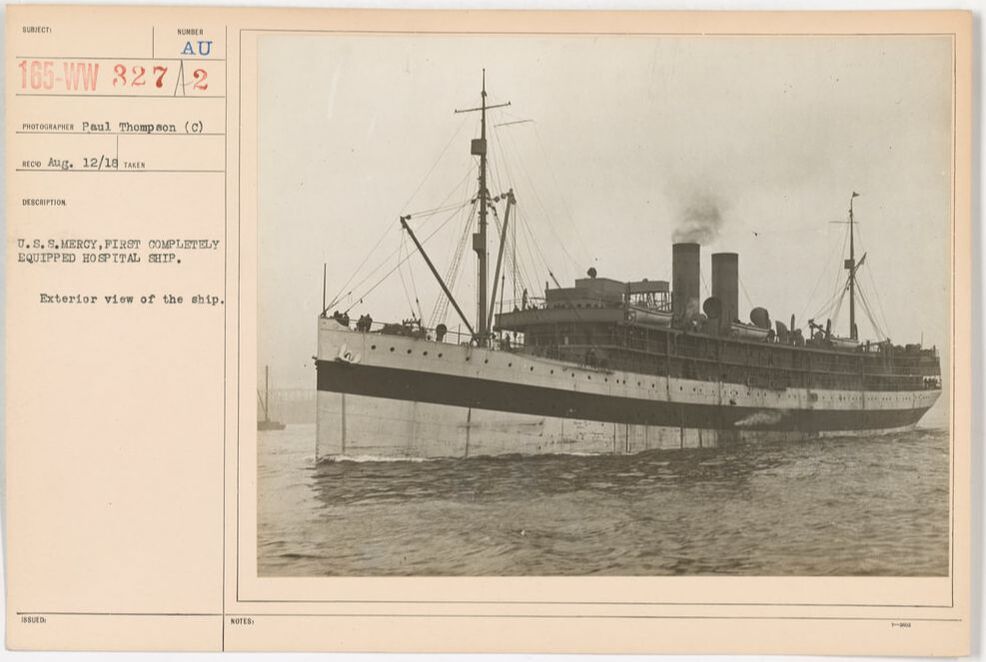

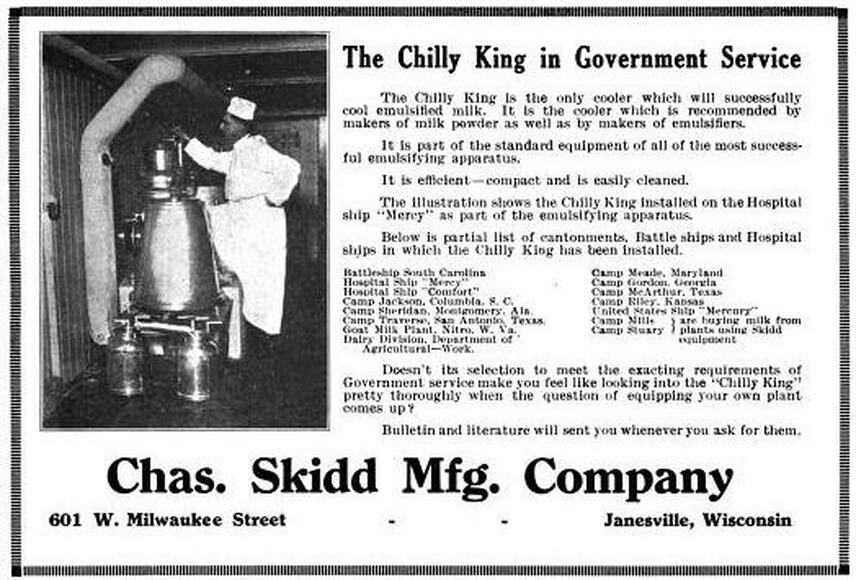

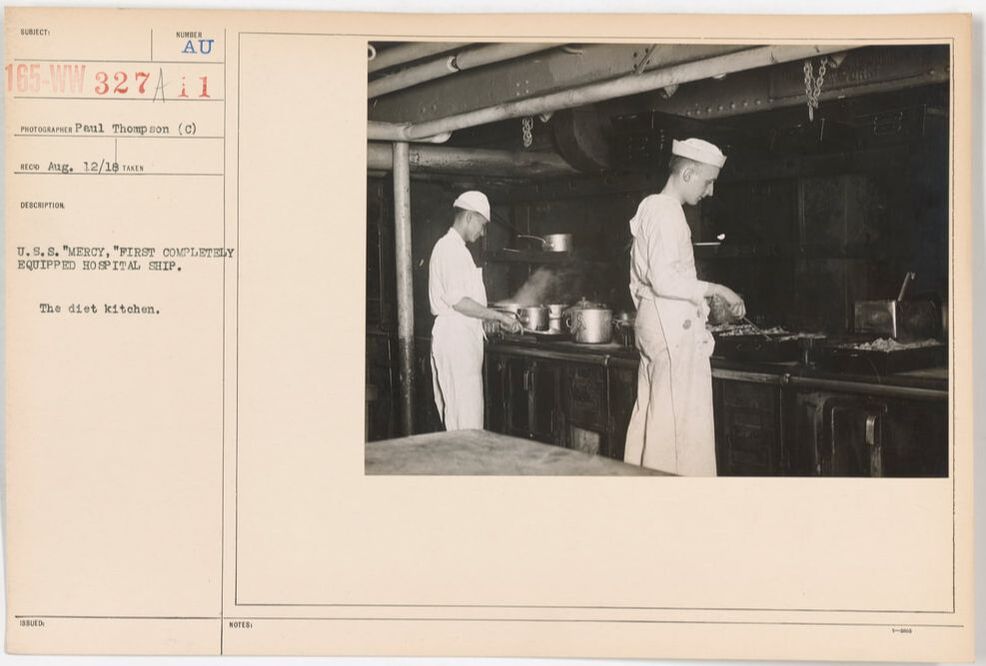

I've been getting a lot of calls for information about ice cream lately, and that has sent me down a rabbit hole. I did a whole talk on the history of ice cream last year (you can watch the filmed version here), but while I knew ice cream was a big tradition in naval history, I didn't know the connection to the First World War. I don't usually cover the history of military consumption of food during the World Wars, but this topic was just too much fun to resist. Ice cream wasn't always the Navy's treat of choice. For over a hundred years rum was the preferred ration by many sailors. But in the late 19th century the Temperance movement began to have increasing power over society. By 1919 we had a Constitutional Amendment (the 19th - often known just as "Prohibition"). But the armed forces went dry much earlier. In particular, on July 1, 1914, the U.S. Navy went alcohol-free. At the same time, naval vessels were being stocked with ice cream. In the May, 1913 issue of The Ice Cream Trade Journal, an article entitled "Sailors Like Ice Cream" explained that the Navy had recently ordered 350,000 pounds of evaporated milk - ostensibly for all sorts of cooking and baking, but ice cream was high on the list. You may wonder why hospital ships in the First World War were manufacturing ice cream on board? Well, it involves multiple factors. First is that ice cream was a product of milk; during the Progressive Era, milk was considered the "perfect food" as it contained fats, proteins, and carbohydrates all in one (supposedly) easily digestible package. Although many people are lactose intolerant, the White Anglo-Saxon dominance of American culture at the time prized milk. Ice cream rode into nutritional value on the coattails of milk. During this time period, dairy-based products like puddings, custards, milk and cream on cooked cereals or with toast, and ice cream were all considered nutritious foods for people who had been injured or ill. Along with foods like beef tea, eggs, and stewed fruits, these made up the bulk of recommended hospital foods from the late 19th century to World War I. Ice cream shows up quite frequently in early reports of the Surgeon General to the U.S. Navy. In his 1918 report to the Secretary of the Navy, ice cream appears to cause more problems than it solves. Notably, the use of ice cream produced commercially results in several instances of crew sickness, including simple illnesses like strep throat, alongside more serious ones like a diphtheria outbreak in Newport in 1917, which was traced to ice cream produced off-station. Fears of the spread of typhoid from places like restaurants, soda fountains, and ice cream shops led to "antityphoid inoculations" at naval shipyards. In Chicago, "All soft-drink and ice-cream stands have promised to give sailors individual service in the form of paper cups and dishes. To make this more effective, it is believed that an order should be issued prohibiting men from accepting any other kind of service." The Surgeon General also recommended inspection of offsite dairies and bottling works for milk, ice cream, and soft drinks to ensure proper sterilization of equipment and pasteurization of dairy products, as well as inoculation of employees against typhoid and smallpox. But ice cream was also noted as essential not only on the existing hospital ship USS Solace, but also on two new hospital ships fitted out since the declaration of war in 1917 - the USS Mercy and the USS Comfort. These ships included a cold storage plant and a refrigerating machine that could "produce, under favorable circumstances, a ton of ice or more a day." The ships also had distilling plants, able to convert seawater to fresh water, up to 20,000 gallons per day. In addition to describing the medical wards, crew facilities, laundry, and kitchen, the report noted: The most valuable adjunct in the treatment and feeding of the sick is the milk emulsifier, popularly known as the "mechanical cow." The milk produced from this machine is made from a combination of unsalted butter and skimmed milk powder and can be made with any proportion of butter fat and proteins desired. This machine will produce 15 gallons of cold, pasteurized milk in 45 minutes. The electric ice cream machine, controlled by one man, makes 10 gallons at a time and is supplemented by small freezers for preparing individual diets for the sick. According to the October, 1918 issue of The Milk Dealer, the "mechanical cow" had been displayed as part of the exhibits at the National Dairy Show in Columbus, Ohio in the fall of 1917. They noted: The "Mechanical Cow" Becoming Famous. Few people who saw the combination exhibit of Merrell-Soule Co. and the DeLaval Separator Co., last October, in Columbus, would have believed that within a year from that beginning the use of the Emulsor in combining Skimmed Milk Powder, unsalted butter and water would be taken up by Army, Navy, City Administrations, etc. throughout the United States. Such is the fact, however. The Mechanical Cow is now producing milk and cream on the U.S.S. Comfort and U.S.S. Mercy, the two splendid hospital ships of the Navy. An installation on board the U.S.S. South Carolina is kept working continuously to supply the demands of her crew. Mechanical Cows are filling the needs of milk at the base hospitals and several camps and one large machine is being operated by one of the city departments of New York. Health officers, physicians, milk experts and authorities on infant feeding all unanimously agree that milk and cream made by means of the "Mechanical Cow" is superior in every way to the average milk supply. This advertisement for "The Chilly King," a cooling machine that was part of the "Mechanical Cow" system on ships like the U.S.S. Mercy (a photograph of the machinery on board featured in the ad) also names a number of naval ships and military camps which use it, including:

By enabling ships and camps to use shelf-stable skimmed milk powder and unsalted butter, which keeps a very long time in cold storage, "mechanical cows" allowed for an ample supply of milk made in sanitary conditions. For naval ships, this was especially important when crews were away from shore for long periods of time. Ice cream also helped patients recover from illness (or so medical professionals at the time believed) but it also helped a great deal with morale. The professionalization of ship operations via the installation of state-of-the-art equipment was a hallmark of the First World War, but the U.S.'s late involvement in the war hamstrung most shipbuilding operations. Indeed, the construction of a new hospital ship in 1916 was actually shelved in favor of retrofitting existing ships like those that were transformed into the U.S.S. Comfort and U.S.S. Mercy, which had initially served as the sister passenger steamboats S.S. Havana and S.S. Saratoga, respectively. Part of the Ward Line, these very fast steamships ran the New York City to Havana, Cuba route but were requisitioned in 1917 first as troop transports, and later as hospital ships. The U.S.S. Mercy spent time as a home for the homeless during the Great Depression before she was scrapped in the 1930s, and the U.S.S. Comfort went back to civilian passenger transport for the Ward line under her old name, the S.S. Havana, before being pressed into service again in World War II, this time as a troop transport once again. The names USS Comfort and USS Mercy would be revived in World War II and a third pair of hospital ships bearing those names are still in operation today. Although ice cream is no longer considered central to the recuperation of the sick and wounded, it is still served on American naval vessels around the world. Ice cream would play an even more important role in the Navy during the Second World War. But that's a tale for another World War Wednesday! The Food Historian blog is supported by patrons on Patreon! Patrons help keep blog posts like this one free and available to the public. Join us for awesome members-only content like free digitized cookbooks from my personal collection, e-newsletter, and even snail mail from time to time! Don't like Patreon? Leave a tip!

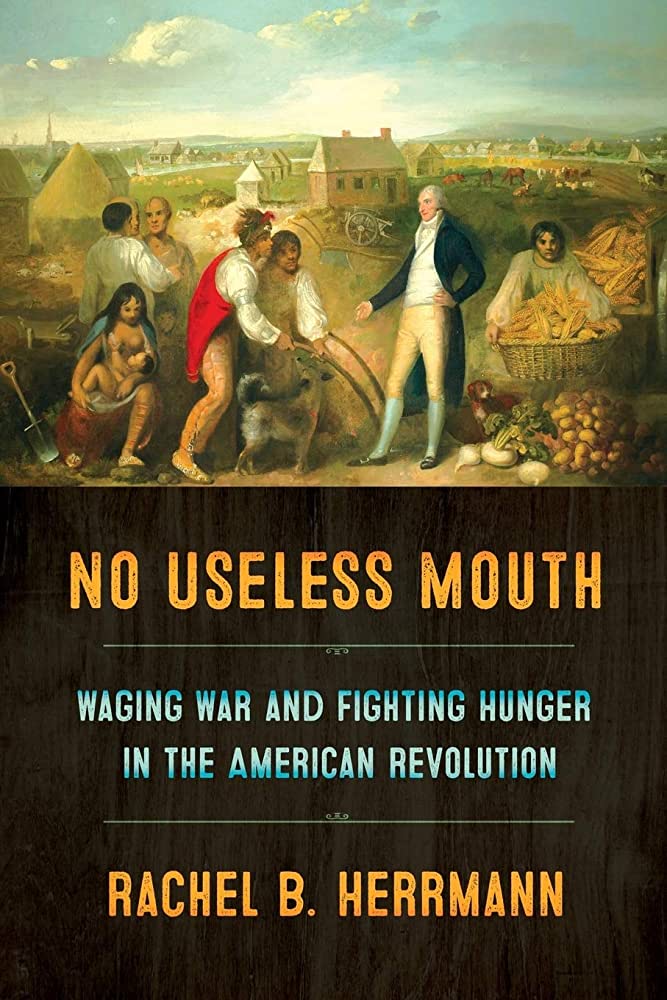

This article contains Amazon.com and Bookshop.org affiliate links. If you purchase anything from these links, The Food Historian will receive a small commission. No Useless Mouth: Waging War and Fighting Hunger in the American Revolution, Rachel B. Herrmann. Cornell University Press, 2019. 308 pp., $27.95, paperback, ISBN 978-1501716119. This may be the longest I have ever taken to write a book review. I first received this book and the invitation to review it for the Hudson Valley Review in the fall of 2021. As many of you know, 2022 was a rough year for me, for many reasons, but I finally turned in the review in February of 2023. A few days ago, I received my copy of the Review and now that my book review is in print, I feel I can share it here! This edition of the Review is great, with several excellent articles and other book reviews, so if you manage to find a copy, please check it out! Back issues are often posted digitally. Without further ado, the review: In the historiography of the American Revolution, one can be forgiven for thinking every possible topic has been covered. But Rachel B. Herrmann’s new book No Useless Mouth: Waging War and Fighting Hunger in the American Revolution brings new nuance to the period. In it, Herrmann argues that food played a decisive role in the shifting power dynamics between White Europeans, Indigenous Americans, and enslaved and free Africans and people of African descent. She looks at the American Revolution through an international lens, covering from 1775 in the various colonies through to the dawning of the 19th century in Sierra Leone. The book is divided into eight chapters and three parts. Part I, “Power Rising,” introduces us to the ideas of “food diplomacy,” “victual warfare,” and “victual imperialism” within the context of the American Revolution. Contrasting the roles of the Iroquois Confederacy in the north and the Creeks and Cherokees in the South, Herrmann brings additional support to the idea that U.S. treaties with Indigenous groups should join the pantheon of diplomacy history, while centering food and food diplomacy within the context of those treaties. She also addresses how Indian Affairs agents communicated with various Indigenous groups – with varying success. Part II, “Power in Flux,” addresses the roles of people of African descent in the American Revolution, focusing primarily on Black Loyalists as they gained freedom through Dunmore’s Proclamation and the Philipsburg Proclamation. Black Loyalists fought on behalf of the British as soldiers, spies, and foraging groups, and escaped post-war to Nova Scotia with White Loyalists. Part III, “Power Waning,” summarizes what happened to Indigenous and Black groups post-war, focusing on the nascent U.S. imperialism of Indian policy and assimilation and the role food and agriculture played in attempts to control Native populations. It also argues that Black Loyalists adopted the imperialism of their British compatriots in attempts to control food in Sierra Leone, ultimately losing their power to White colonists. Part III also includes Herrmann’s conclusion chapter. No Useless Mouth is most useful to scholars of the American Revolution, providing good references to food diplomacy while also highlighting under-studied groups like Native Americans and Black Loyalists. However, lay readers may find the text difficult to process. Herrmann often makes references to groups and events with little to no context, assuming her readers are as knowledgeable as she. In addition, the author appears to conflate Indigenous groups with one another, making generalizations about food consumption patterns and agricultural practices without the context of cultural differences. In focusing on the Iroquois Confederacy and the Creeks/Cherokee, Herrmann also ignores other Native groups, despite sometimes using evidence from other Indigenous nations to support her arguments. For instance, when discussing postwar assimilation practices with the Iroquois in the north and the Creeks and Cherokee in the south (often jumping from one to another in quick succession), she cites Hendrick Aupaumut’s advice to Europeans for dealing successfully with Indigenous groups. But she fails to note that Aupaumut was neither Iroquois, Creek, nor Cherokee, but was in fact Stockbridge Mohican. The Stockbridge Mohicans were a group from Stockbridge, Massachusetts that was already Christianized prior to the outbreak of the American Revolution. They fought on the Patriot side of the war, with disastrous consequences to the Stockbridge Munsee population, and ultimately lost their lands to the people they fought to defend. Without knowledge of this nuance, readers would accept the author’s evidence at face-value. Herrmann’s strongest chapters are on the Black Loyalists, and her research into the role of food control in both Nova Scotia and Sierra Leone is groundbreaking, but even those chapters have a few curious omissions. In discussing Lord Dunmore’s Proclamation, which was issued in 1775 in Virginia and targeted enslaved people held in bondage by rebels, freeing those who were willing to join the British Army. The chapter then focuses primarily on the roles of enslaved people from the American South. But Herrmann also mentions briefly the Philipsburg Proclamation, issued in 1779 in Westchester County, NY, which freed all people held in bondage by rebel enslavers who could make it to British lines. That proclamation arguably had a much larger impact on the Black Loyalist population, as it also included women, children, and those above military age, thousands of whom streamed into New York City, the primary point of evacuation to Nova Scotia. And yet, Herrmann does not mention at all enslaved people in New York and New Jersey, where slavery was still very active throughout the American Revolution and well into the 19th century. In the chapter on Nova Scotia, Herrmann also mentions that White Loyalists brought enslaved people with them, still held in bondage. Neither Dunmore’s nor the Philipsburg proclamations freed people held in bondage by Loyalists, and yet they get only a brief mention. Her chapters on Indigenous-European relations are extremely useful for other historians researching the period, but would have been improved with additional context on land use in relation to food. Herrmann often references famine, food diplomacy, and victual warfare in these chapters, without addressing the impact of land grabs and disease on the ability of Indigenous groups to feed themselves. She references, but does not fully address the need of European settlers to expand settlement into Indian Country as a motivating factor in war and postwar diplomacy. Finally, while the focus of the book is specifically on the roles of Indigenous and Black groups in the context of food and warfare, the omission of victual warfare by British and American troops and militias, especially in “foraging” and destroying foodstuffs of White civilian populations throughout the colonies seems like a missed opportunity to compare and contrast with policies and long-term impacts of victual warfare toward Indigenous groups. In all, this book is a worthy addition to the bookshelves of serious scholars of the American Revolution, especially those interested in Indigenous and Black history of this time period, but it also leaves room for future scholars to examine more closely the issues Herrmann raises. No Useless Mouth: Waging War and Fighting Hunger in the American Revolution, Rachel B. Herrmann. Cornell University Press, 2019. 308 pp., $27.95, paperback, ISBN 978-1501716119. The Food Historian blog is supported by patrons on Patreon! Patrons help keep blog posts like this one free and available to the public. Join us for awesome members-only content like free digitized cookbooks from my personal collection, e-newsletter, and even snail mail from time to time! Don't like Patreon? Leave a tip!

|

AuthorSarah Wassberg Johnson has an MA in Public History from the University at Albany and studies early 20th century food history. Archives

July 2024

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed