|

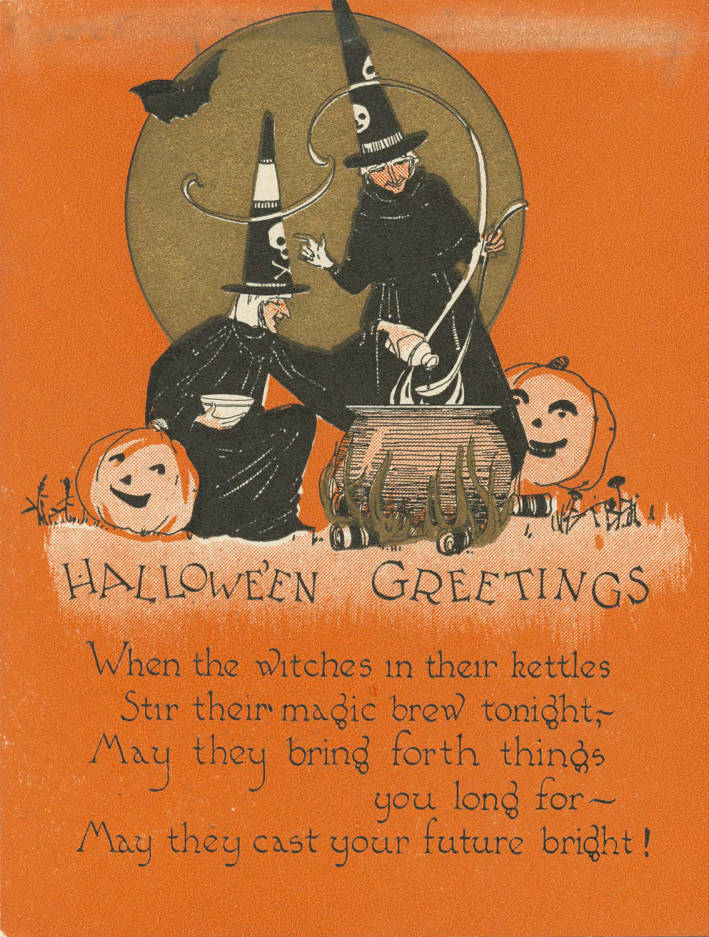

Welcome to The Food Historian's 31 Days of Halloween extravaganza. Between social media (Facebook, Instagram, Twitter) and this blog, I'll be sharing vintage Halloween content nearly every day this month! Home Halloween parties were extremely popular during the first decades of the 20th century, and although the First World War did slow some of the celebrations, it didn't entirely stop them. On October 28, 1917, the Poughkeepsie Eagle published a full-page spread celebrating Halloween. In it, "Hints for the Hallowe'en Lunch" outlined just how locals could celebrate even with voluntary restrictions on meat, butter, white flour, and sugar. The "Jack-o'-Lantern Salad" features inexpensive salt herring and potatoes, the loaf cake features just one cup of wheat flour with brown sugar and raisins for sweetener, and the "Priscilla Pop Corn" sounds very much like caramel corn! This lunch was likely intended for adult women rather than children, though young women may also have been the intended audience. A composed vegetable salad with sandwiches was typical fare for club women and other ladies who lunched. I've transcribed the whole article below for your reading pleasure. Hints for the Hallowe'en Lunch"Table decorations for a Jack'o'Lantern Jubilee must necessarily include pumpkins big and pumpkins little. Both kinds are introduced into the attractive witches cauldron of the illustration. Its value is increased when an assortment of prophecies is put into the kettle to be distributed to the guests when the strong black coffee is served. "Hallowe'en menus usually include the homely cider and doughnuts, chestnuts and apples which belong to other harvest home celebrations. "The following menu is plain and substantial and just a little different. "Jack-o'-Lantern Menu Jack-o'-Lantern Salad Brown Bread Sandwiches Fruit Loaf Cake Priscilla Pop Corn Cider or Coffee "Jack-o'-Lantern Salad "Soak salt herring in lukewarm water and drain. Cook in boiling water for fifteen minutes. When cool, separate into flakes and add an equal quantity of cold boiled potato, and one-fourth quantity of chopped, hard-boiled eggs. Mix with French dressing [ed. note: vinaigrette] and chill in refrigerator until serving time. Beat one-fourth cupful of cream until stiff and mix with it two tablespoons chopped pimentos. Mix with equal portion of mayonnaise dressing and combine with the salad. Serve on lettuce leaves, slightly flattening the heap on top to receive the "Jack-o'-Lantern," which is a small full moon face cut from a very thin slice of American cheese, the eyes marked with bits of clove, and the nose and mouth by thing strips of pimento. Brown bread sandwiches, with a filling of chopped peanuts is served with this salad. "Raised Fruit Loaf. "One cupful of butter, two cupsful brown sugar, two eggs, two cupsful of bread sponge, two teaspoonsful cinnamon, one teaspoonful clove, two teaspoonsful soda, one teasponful salt, two cupsful raisins, one cupful flour. "Cream butter and add slowly, while beating constantly sugar, then add well-beaten eggs, bread sponge, spice, soda and salt, and flour mixed and sifted, and raisins, cut in half and dredged with flour. Turn into buttered and floured oblong pans and let rise two and one-half hours and then bake for an hour. "Priscilla Popped Corn. "Two quarts of popped corn, two tablespoonsful butter, two cupsful browned sugar, one-half cupful water, one-half teaspoonful salt. Put butter in saucepan, and when melted add sugar, salt and water. Boil sixteen minutes and pour over popped corn, coating each grain thoroughly." What do you think? Would you like to attend such a lunch? I know I would! Even the herring potato salad sounds good and distinctly Scandinavian, although not particularly Halloween-ish. Priscilla popcorn, however, is definitely going on the to-make list! The Food Historian blog is supported by patrons on Patreon! Patrons help keep blog posts like this one free and available to the public. Join us for awesome members-only content like free digitized cookbooks from my personal collection, e-newsletter, and even snail mail from time to time! Don't like Patreon? Leave a tip!

0 Comments

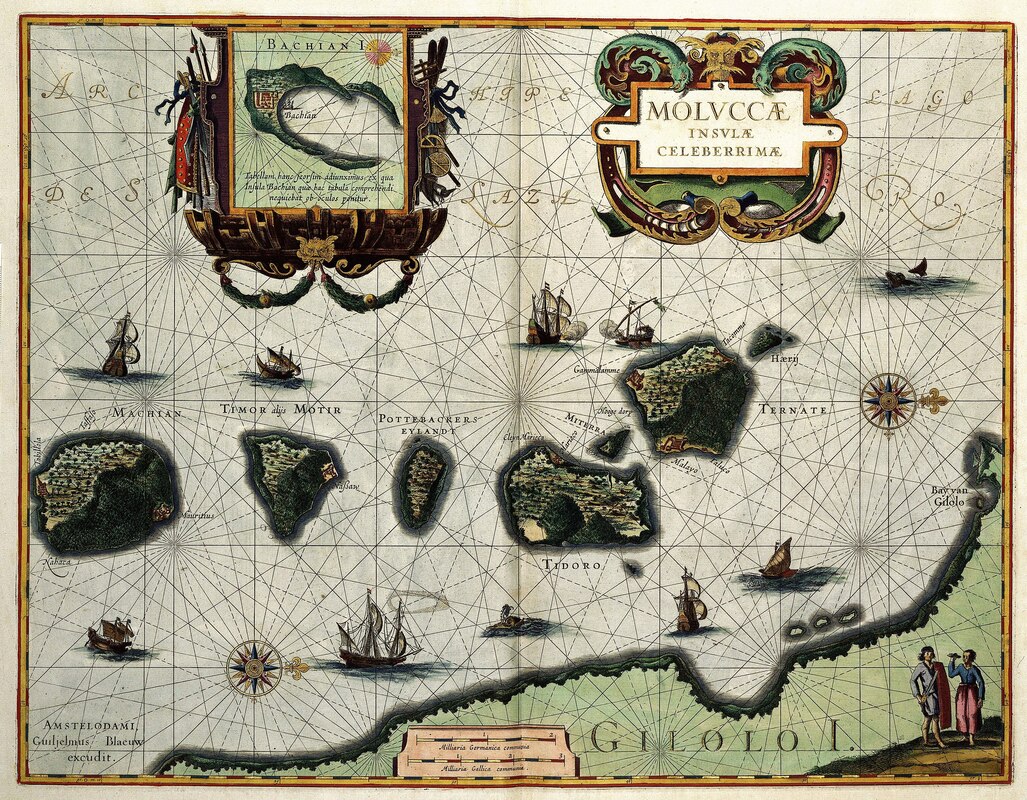

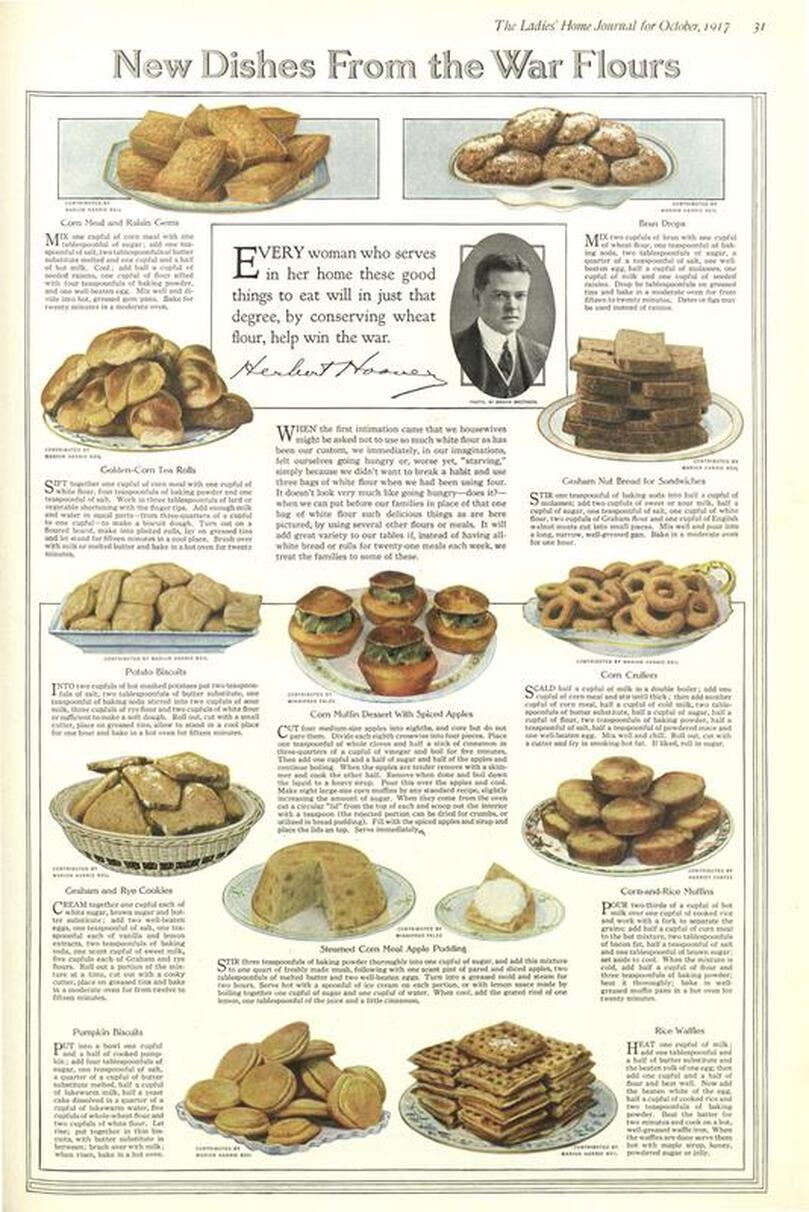

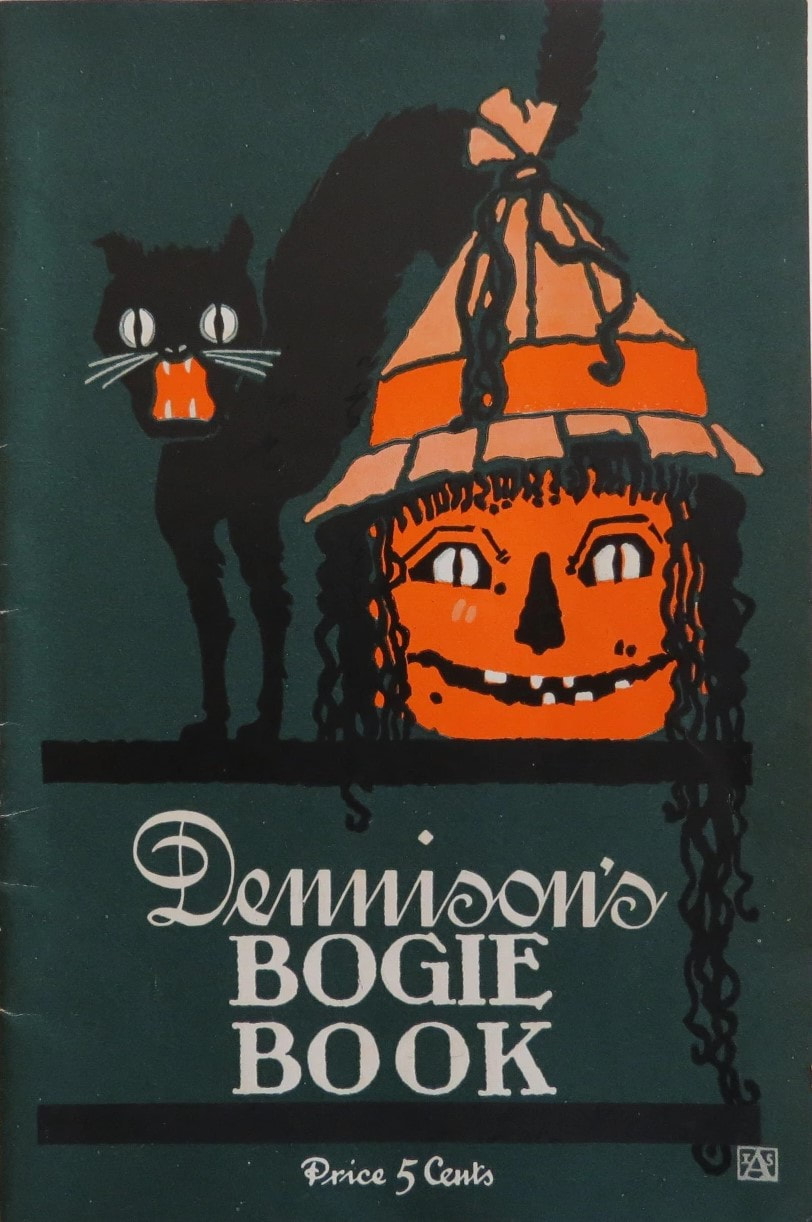

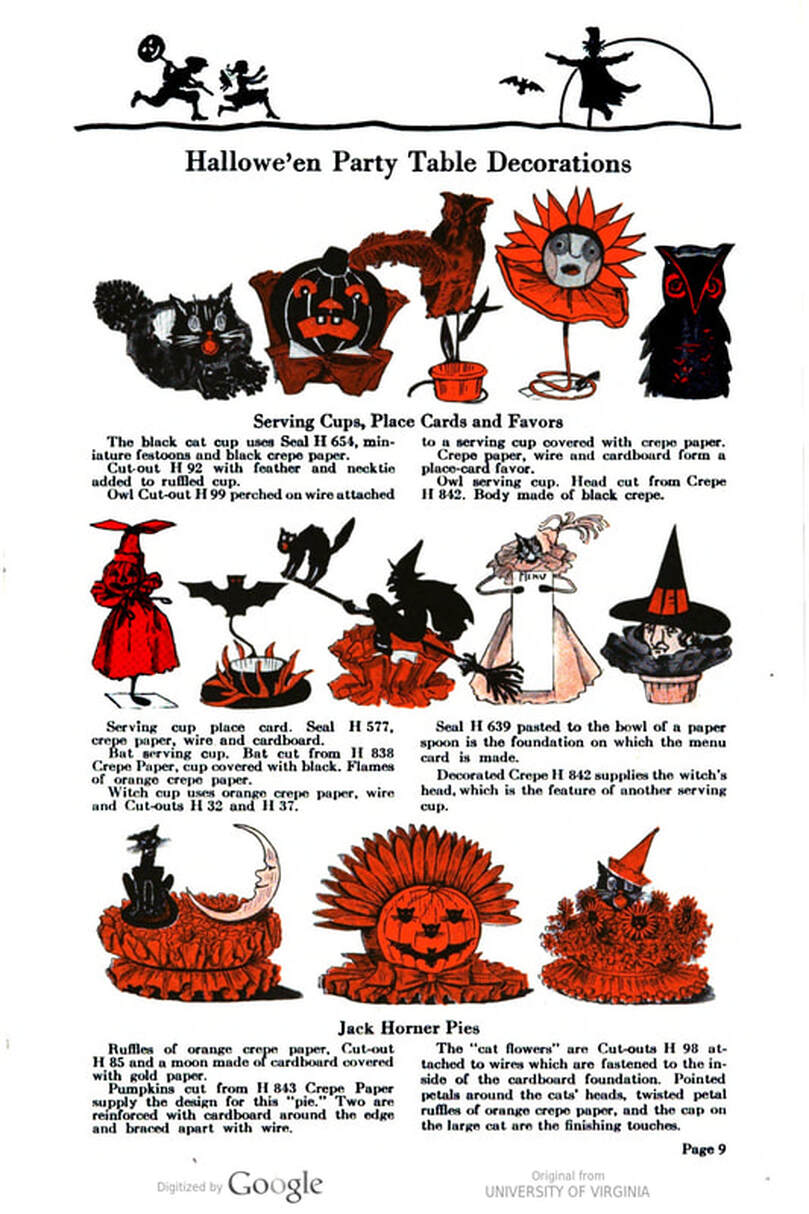

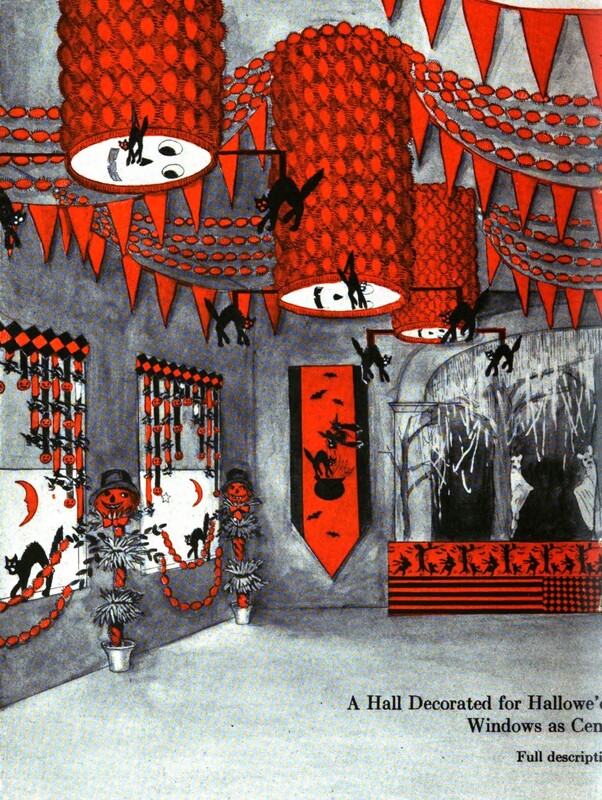

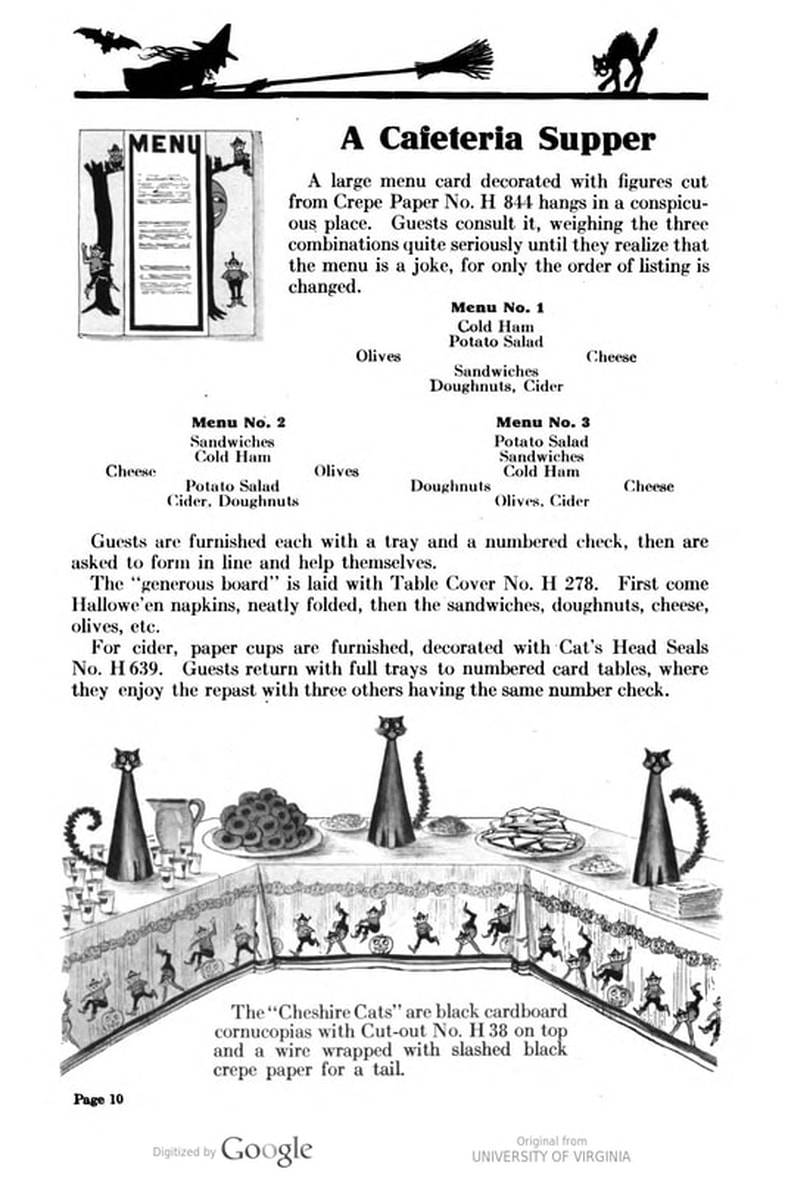

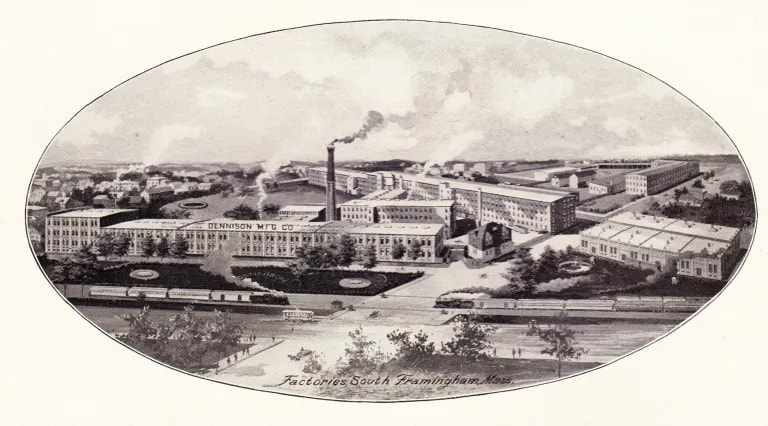

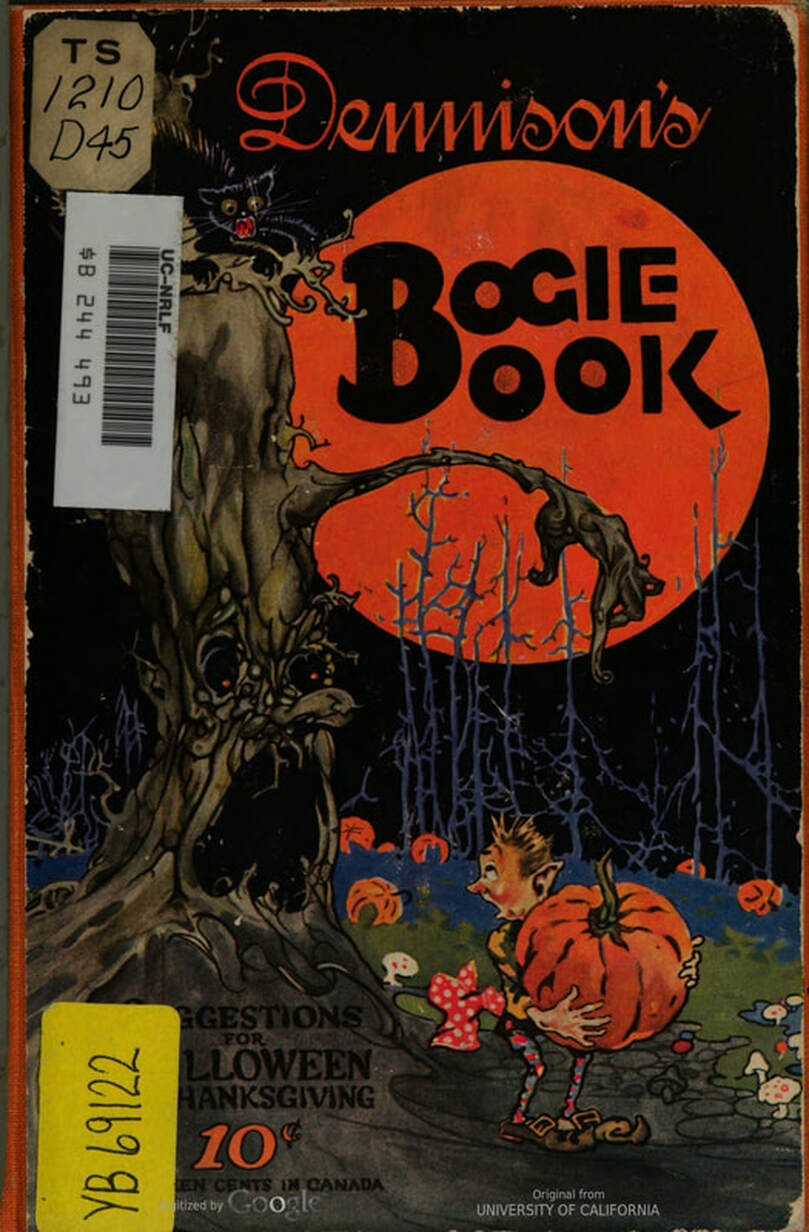

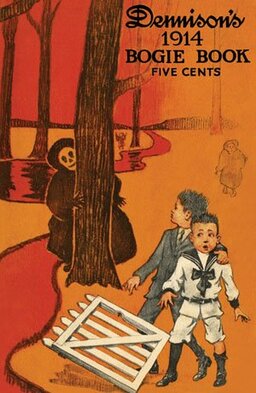

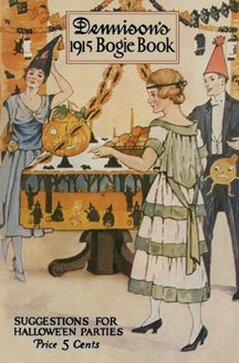

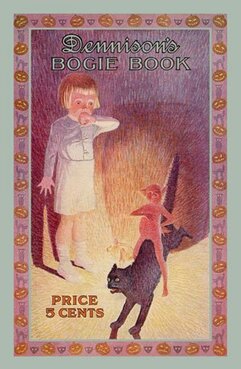

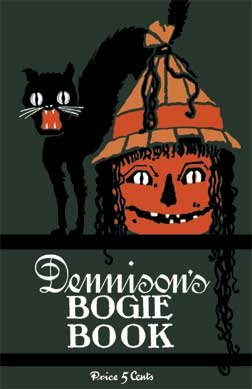

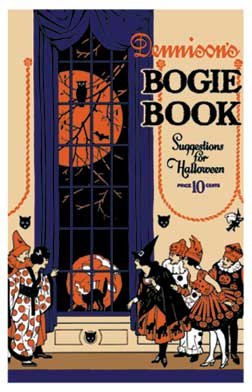

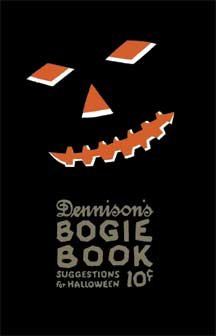

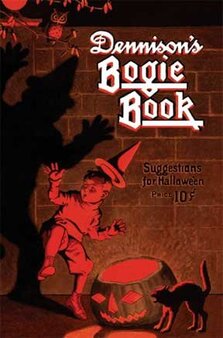

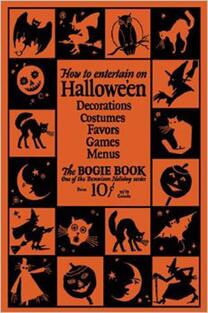

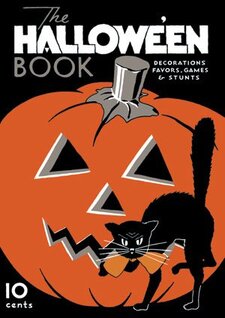

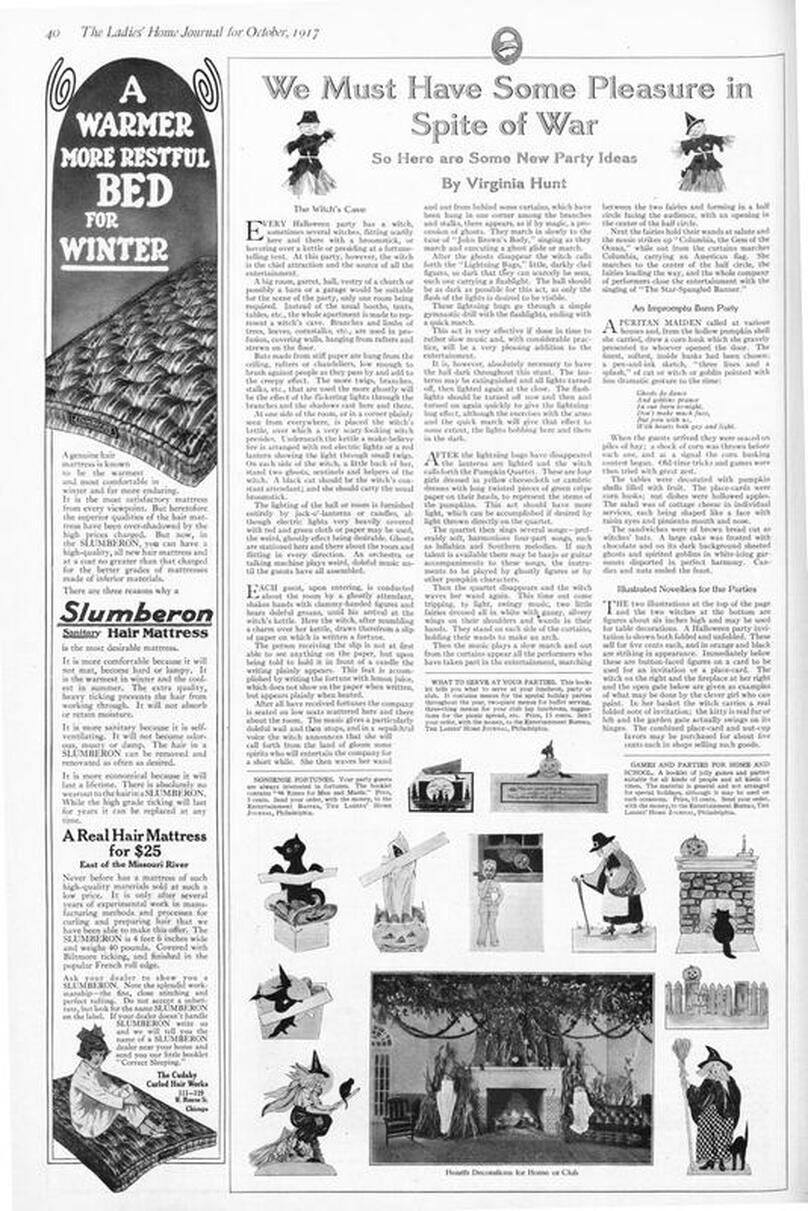

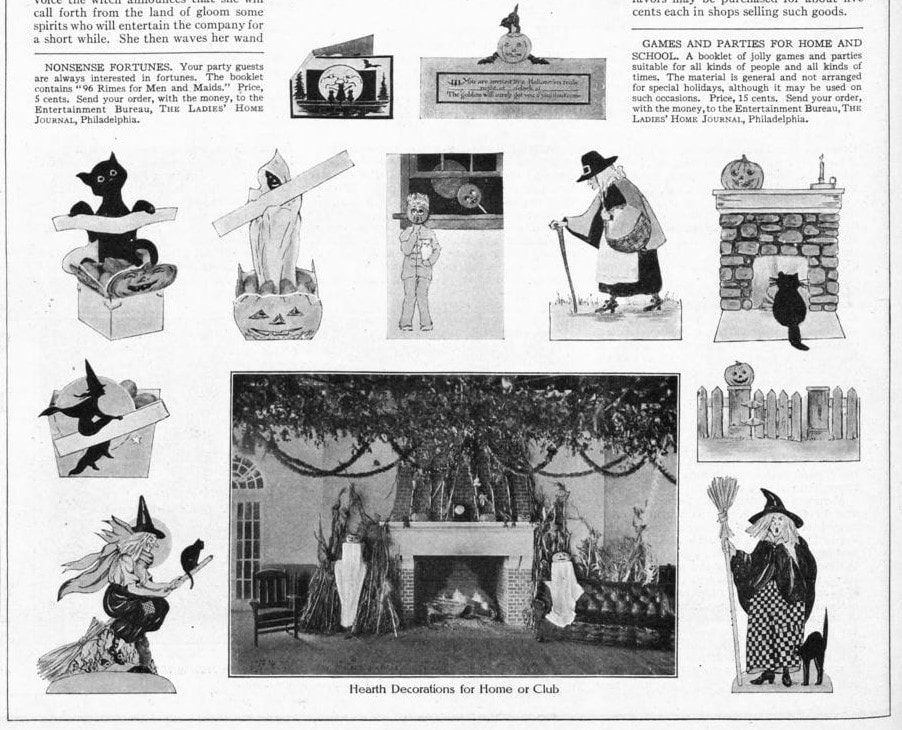

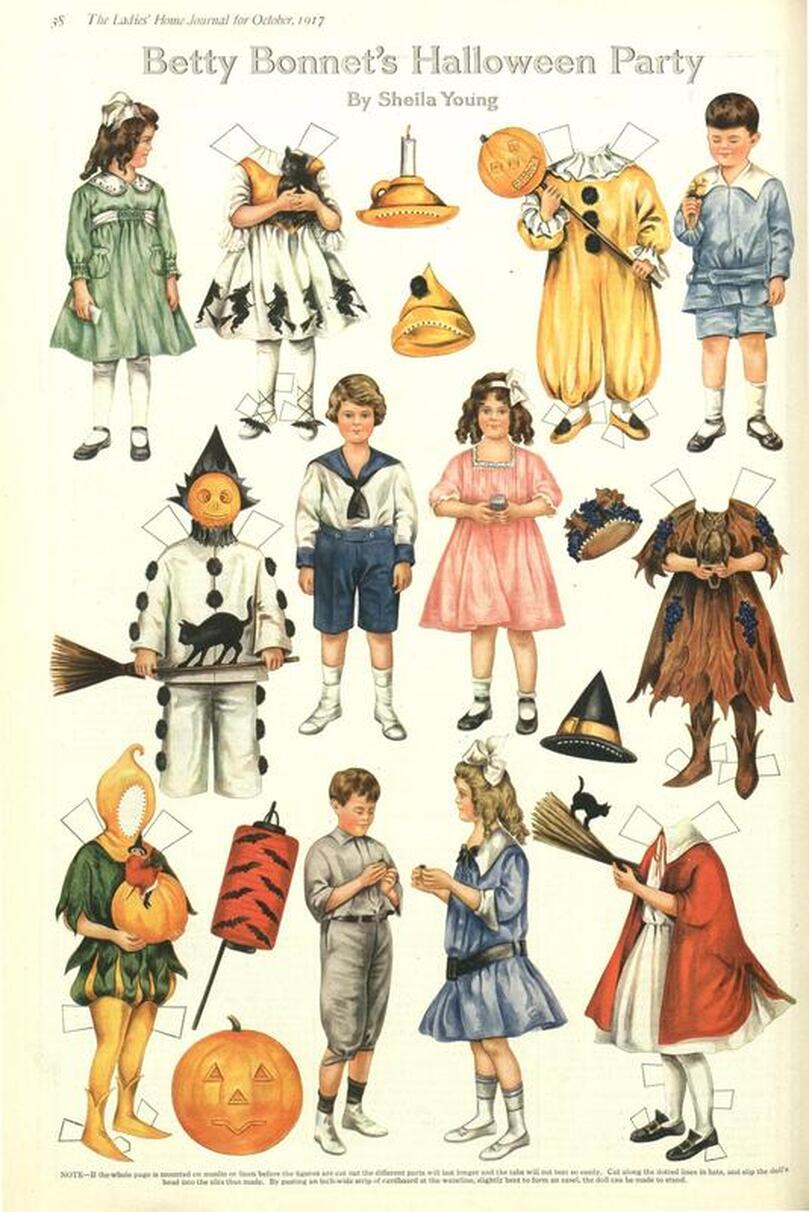

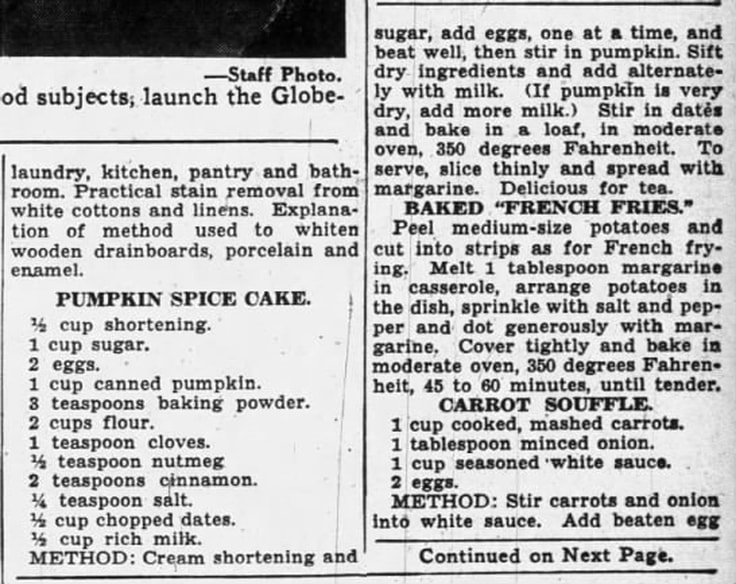

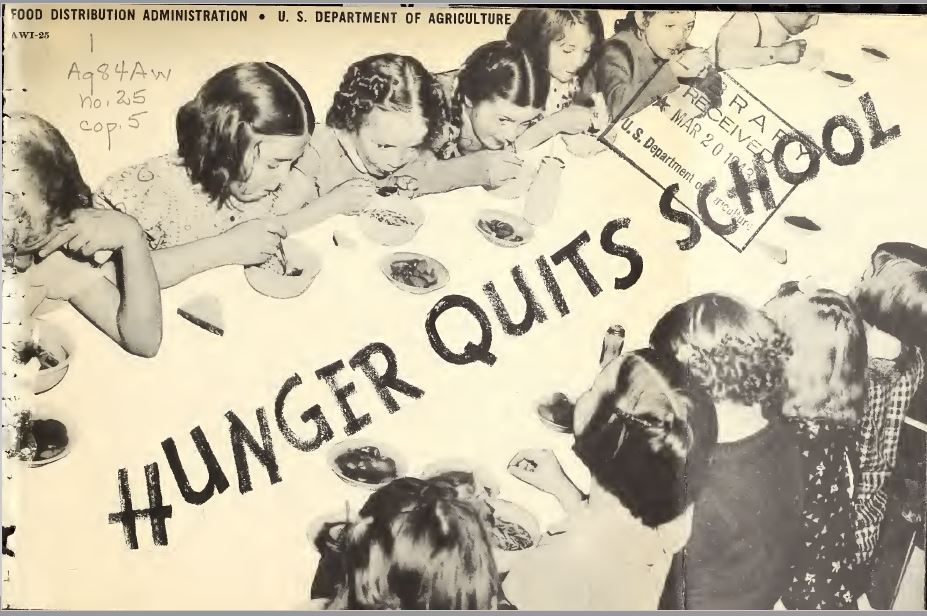

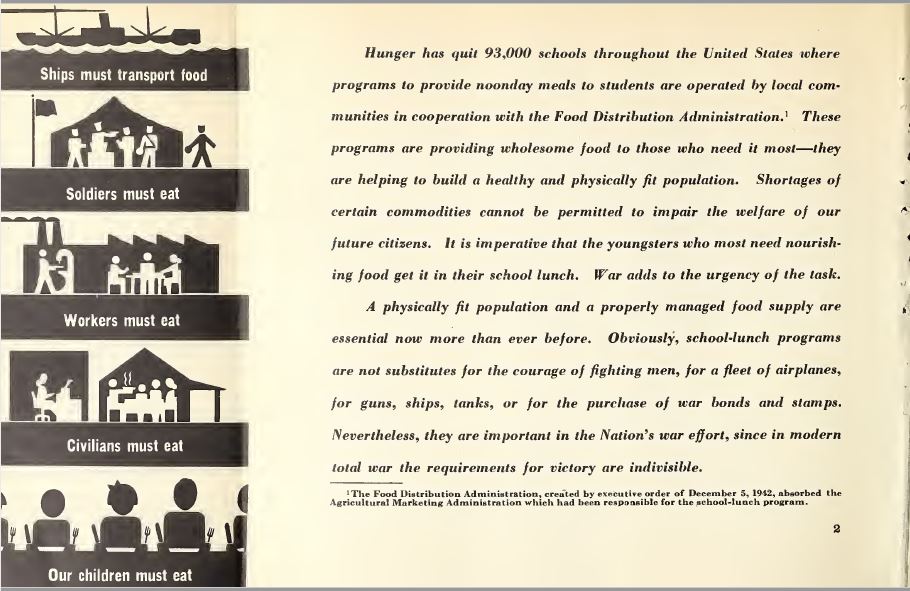

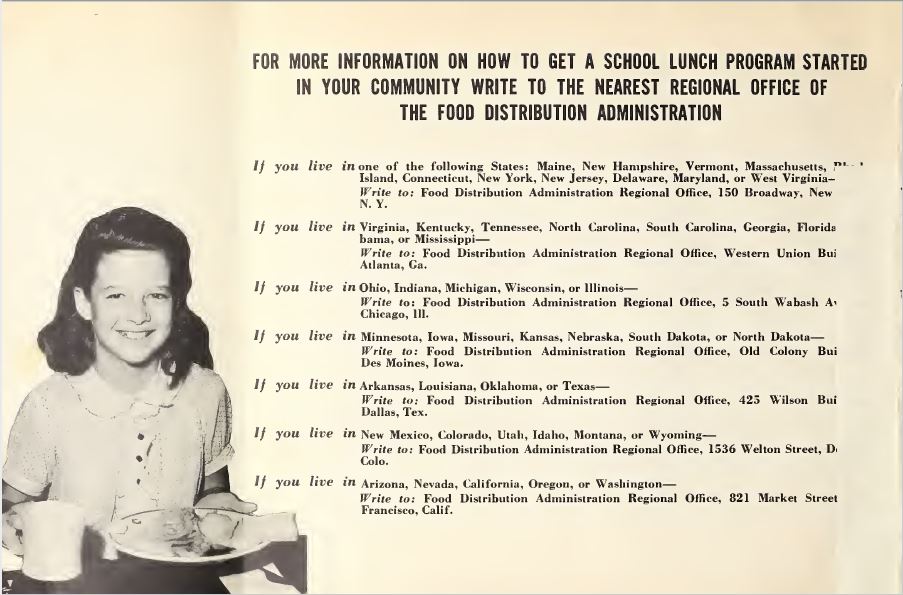

Welcome to The Food Historian's 31 Days of Halloween extravaganza. Between social media (Facebook, Instagram, Twitter) and this blog, I'll be sharing vintage Halloween content nearly every day this month! We're revisiting the October, 1917 issue of the Ladies' Home Journal this week with some very fall-ish recipes. The beautiful color plate featured in the magazine contains a number of recipes for baked goods using wheat substitute flours. Refined white flour was a shelf stable product necessary for the war effort to feed both American troops and our French, British, and Belgian allies. But the 1916 wheat harvest was poor throughout the Americas, and the United States joined the war in April, 1917 - too late to increase wheat crops for the year. Herbert Hoover, United States Food Administrator, asked Americans to voluntarily reduce their consumption of wheat (along with meat, fats, and sugar). This page of helpful recipes bears Hoover's portrait and purportedly a quote from him as well, reading "Every woman who serves in her home these good things to eat will, in just that degree, by conserving wheat flour, help win the war." Not the snappiest quote from Hoover, but the emphasis on using wheat substitutes, especially corn, were popular at the time. Although rationing was voluntary, not mandatory, many Americans tried to make their baking more patriotic and reduce their reliance on refined white flour. Because this is from 1917, we don't have mandatory sugar rationing, as we see by the fall of 1918. But cornmeal, rice, rye flour, graham flour (today sometimes called entire wheat flour - made from whole wheat berries and different from modern whole wheat flour, which is white flour with some wheat germ added back in), oatmeal and oat flour, and barley flour were all used to help reduce the reliance on white flour. Of them all, cornmeal and rice were the most plentiful. In the Halloween spirit, I've transcribed two of the most festive recipes on the list - the unimaginatively named "Corn Muffin Dessert with Spiced Apples" and "Pumpkin Biscuits." Enjoy these seasonal treats! Corn Muffin Dessert with Spiced ApplesCut four medium-size apples into eighths, and core but do not pare them. Divide each eighth crosswise into four pieces. Place one teaspoonful of whole cloves and half a stick of cinnamon in three-quarters of a cupful of vinegar and boil for five minutes. Then add one cupful and a half of sugar and half of the apples and continue boiling. When the apples are tender remove with a skimmer and cook the other half. Remove when done and boil down the liquid into a heavy sirup. Pour this over the apples and cool. Make eight large-size corn muffins by any standard recipe, slightly increasing the amount of sugar. When they come from the oven, cut a circular "lid" from the top of each and scoop out the interior with a teaspoon (the rejected portion can be dried for crumbs, or utilized in bread pudding). Fill with the spiced apples and sirup and place the lids on top. Serve immediately. My translation of the recipe: 4 apples 3/4 cup cider vinegar 1 teaspoon whole cloves half stick cinnamon 1 1/2 cup sugar 8 corn muffins (homemade or store bought) Cut the apples into quarters and then again in half to form eighths. Core, but leave skin on. Cut crosswise into thick slices. Bring the vinegar and spices to a boil and let boil for five minutes. Then add sugar, stirring well to dissolve. Add half the apples and cook until apples are tender (can be easily pierced with a fork or sharp knife). Remove to a dish with a slotted spoon, then add the remaining apples and cook until tender. Remove to dish and continue cooking spiced vinegar syrup until it is thick. Pour over apples and let cool. Cut tops from muffins and use spoon to carefully hollow out, leaving at least an inch of muffin on all sides. When apples are cool, spoon into muffin cases. Serve cold for dessert. Pumpkin BiscuitsPut into a bowl one cupful and a half of cooked pumpkin; add four tablespoons of sugar, one teaspoonful of salt, a quart of a cupful of butter substitute melted, half a cupful of lukewarm milk, half a yeast cake dissolved in a quarter of a cupful of lukewarm water, five cupfuls of whole-wheat flour and two cupfuls of white flour. Let rise; put together in thin biscuits, with butter substitute in between; brush over with milk; when risen, bake in hot oven. An here's my modern translation: 1 1/2 cups pureed pumpkin (or 1 can) 4 tablespoons sugar 1 teaspoon salt 1/4 cup (half a stick) butter or margarine, melted 1/2 cup milk, warmed 1/2 teaspoon active dry yeast 1/4 cup lukewarm water 5 cups whole wheat flour 2 cups white flour. Mix pumpkin, sugar, salt, melted butter, and milk. In a separate bowl bloom yeast in warm water - if it foams it is ready to use. Add to pumpkin mix, then add flour gradually (start with white flour). Knead well. Cover and let rise in a warm place. When doubled in bulk, punch down and roll out thin. Cut into rounds with biscuit cutter. Spread one round with softened butter or margarine, then stick another round on top. Brush top round with milk. Preheat oven to 425 F. Let rise again, then bake in hot oven, 12-15 minutes or until golden brown. What do you think? Would you try either of these recipes? The Food Historian blog is supported by patrons on Patreon! Patrons help keep blog posts like this one free and available to the public. Join us for awesome members-only content like free digitized cookbooks from my personal collection, e-newsletter, and even snail mail from time to time! Don't like Patreon? Leave a tip! Welcome to The Food Historian's 31 Days of Halloween extravaganza. Between social media (Facebook, Instagram, Twitter) and this blog, I'll be sharing vintage Halloween content nearly every day this month! If you're a fan of Halloween and all things vintage, you've probably heard of Dennison's Bogie Books. Launched in 1909 by the Dennison paper products company, which specialized in crepe paper, the Bogie Books became hugely popular for their ideas for parties, costumes, and yes, menus. The idea of direct-to-consumer advertising was starting to take off in the 1900s, and certainly food companies were capitalizing on corporate cookbooklets at this time. But Dennison's was one of the first companies to issue what they called "instruction books," but which were more like idea books. Chock full of ideas for table crafts, games, costumes, decorating, party organizing, and menus, they were a one-stop shop for all things Halloween. Nearly all the ideas incorporated Dennison's products, which branched out from just black and orange crepe paper to more elaborate decorations, like printed paper tablecloths and napkins, paper plates, printed crepe paper "borders," die cut figures, and more. The popularity of Halloween parties exploded in the 1920s. Long popular among young adults looking for romance, postwar they shifted to include children and adults, too. Dennison's had been printing Art and Decoration in Crepe and Tissue Paper since 1894 (here's the 1917 edition, complete with colorful samples of crepe and tissue paper). But the 1909 Bogie Book was one of its first forays into a single holiday booklet, although others for Christmas, galas, and other holidays would follow in the 1920s. The Bogie Book, however, was the only one to be printed annually, and illustrates just how popular Halloween had become in the United States. Halloween DecorationsDennison's bread and butter was paper decorations and colored crepe paper. More than any other holiday except perhaps Christmas, decorations were an integral part of Halloween celebrations. Popularized in the late Victorian era, home Halloween parties were increasingly common in the 1910s and 1920s. Dressing up your living room (like below) and other more mundane parts of the house was crucial, and Dennison's promised loads of ideas for themes and instructions for making your own decorations, in addition to purchasing their ready-made stock. Halloween PartiesIn addition to parties at home, increasingly people were throwing more public parties. Halloween was traditionally a time for young love, and it was the perfect opportunity to get young people together. Public parties could be held in church basements, public halls, fraternal organizations, and schools. Bogie Books included hints not only in decorating these larger spaces, but also advice for spooky entrances, harmless tricks, and group games. Halloween CostumesOf course, what was a party without a costume? But Halloween costumes in the 1910s and 1920s were not much like today's. Although classic Halloween archetypes like witches, bats, pirates, pierrot and harlequin figures, and fortune tellers were popular for more obvious costumes, simply dressing in black and orange with spooky figures or motifs was enough for most people. The silhouettes of the day were largely maintained. Sometimes more abstract themes, like "Night" or "The Moon" or "A Star" might allow the fashionable young lady to put in a little more effort while still feeling pretty. In the above image, three young women feature variations on the same 1920s party dress silhouette - one is festooned with orange stripes and ribbons of crepe paper hang from her waist and festoon a hat, with jack-o'-lantern images bobbing at the ends of the streamers. Another is dressed as "The Moon" - with a large silver crescent moon on her head and a black dress and gray cape spangled with more crescent moons and stars - orange streamers hang from her waist. Another goes with a pumpkin theme - wearing an orange bodice with a dagged peplum, a black dress featuring orange jack-o'-lanterns, and long black sleeves with dagged cuffs and black ribbed cape with capelet and a huge stiff collar. Her ensemble is topped with a black cap featuring a festoon of orange leaves. A little girl is also pictured, wearing a black and orange dress featuring a black cat's face on the bodice and a black and orange cap with long ears or leaves protruding from the top. Alas, the men's costumes are less flattering - large, formless tunics and hats worn over their regular button-up shirts and ties. One is dressed as the moon - with the tunic featuring an enigmatic-looking full man-in-the-moon and a tall cone of a cap with another moon and stars. The other is dressed in a black-trimmed orange tunic featuring a large fringed black-and-orange collar and a smiling jack-o'-lantern as a pocket. He wears a witch's hat covered in small jack-'o-lanterns. Each Dennison's Bogie Book included instructions for making each of the pictured costumes from Dennison's crepe paper, printed paper figures, and more. Halloween MenusOf course, The Food Historian is going to be interested in the menus! Along with all their other suggestions, some issues of Dennison's included sample menus. Although not every Bogie Book contains menus, many do reference food and refreshments. Generally, the suggestions are simple and standard party fare - sandwiches, potato chips, potato salad, simple cakes, donuts, fruit, olives, cheese, nuts, etc. - and rarely are recipes included. The emphasis of the books is on decorating the food, tableware, and tables than the food itself. It took a while for the books to gain traction, and the 1909 one didn't get a sequel until 1912. But by then home parties for Halloween were becoming increasingly popular. And Dennison published Bogie Books annually from 1912-1935. Only war (1918) and the Great Depression (1932) stopped their publication. History of the Dennison Manufacturing CompanyThe Dennison Manufacturing Company has a long and interesting history, as it was largely controlled by one family for nearly 100 years. The Dennison company is still around today as Avery-Dennison. From the Hollis Archives, Harvard University, which holds the Dennison corporate collection: "The Dennison Manufacturing Company was a manufacturer of consumer paper products such as tags, labels, wrapping paper, crepe paper and greeting cards. The company was founded by Aaron L. Dennison and his father Andrew Dennison in Brunswick, Maine in 1844. Aaron Dennison, who was working in the Boston in the jewelry business, believed he could produce a better paper box than the imported boxes then on the market. The Dennison's first produced boxes made to house jewelry and watches. Aaron Dennison sold the boxes at his store in Boston, beginning in 1850 and in New York starting in 1854. After early business success, Aaron Dennison retired and yielded control of the company to his brother E.W. Dennison. "The mid to late 19th century saw numerous products introduced by E. W. Dennison, who improved the product so that it became the best and most sought after on the market and under the Dennison name. In order to grow the business, Dennison needed to mechanize the box making process. Dennison introduced the box machine to meet the growing demand of jewelers and watch makers, who began ordering large numbers of boxes. Until the introduction of the box machine, the boxes were still being made one at a time, by hand. The machine mechanized and sped up the box-making process. The company continued to expand, and a larger, centrally located factory was needed. Dennison chose Boston, Mass., as the site of the new factory in order to be close to the city's retail store. "In 1854, Dennison introduced card stock to hold jewelry and jewelry tags. Dennison's tags became wildly popular and the business began to expand rapidly, from the jewelry industry to textile manufacturers and retail merchants. E.W. Dennison noticed a deficiency in the quality of shipping tags and patented a paper washer that reinforced the hole in the tag. Sales of tags hit ten million in the first year. Stationery gummed labels were introduced just after the end of the Civil War. These labels had an adhesive on the back side and were manufactured to stick on boxes, crates or bags. The tag business alone required E.W. Dennison to move his factory in order to fulfill demand. The boxes, shipping tags, merchandise tags, labels and jeweler's cards were moved to the new factory in Roxbury in 1878. That same year the company was officially incorporated as the Dennison Manufacturing Company. "In just over thirty years, the company grew from a small jewelry box maker to a large manufacturer of paper products under the direction of E.W. Dennison and his partner and treasurer Albert Metcalf. Dennison died in 1886 and his son, Henry B. Dennison succeeded him as president of the company. Henry B. Dennison had worked for the company for many years, having opened the Chicago store in 1868 and served as superintendent of the factories since 1869. Henry B. Dennison served as president of the company for only six years and resigned due to poor health in 1892. Henry K. Dyer was then elected president, and under his direction the company consolidated its many factories and operations. In 1897, the Dennison Manufacturing Company purchased the Para Rubber Company plant located on the railroad line in Framingham, Mass. The box division was transferred from Brunswick, Maine; the wax and crepe paper operations from the Brooklyn, NY factory; and the labels and tags from the Roxbury plant. The move was complete in 1898 and the factory was up and running. The factory was divided into five manufacturing divisions: first, the jewelry line, which included boxes, cases, display trays; second, the consumers' line of shipping tags, gummed labels, baggage check and specialty paper items; third, the dealers' line which included all stock products sold to dealers and some consumers; fourth, the crepe paper line; and fifth, the holiday line. Also located at the Framingham plant were financial offices, advertising and marketing departments, sales division and director's offices. Although the company was divided into divisions, all aspects of the company worked together in unison to plan and execute the production, marketing, and sale of a product. The Dennison Mfg. Co. planned well in advance of any sale by conducting market research, reviewing past statistics and gauging future interest in products. "Henry Sturgis Dennison, grandson of the founder, began working for the family business after graduating from Harvard in 1899. He held various jobs at the company including foreman of the wax department and in the factory office. He was promoted to works-manager in 1906, director in 1909 and treasurer in 1912. In 1917, H.S. Dennison was elected president of the company. While serving as president of the company, H.S. Dennison oversaw the international expansion of the firm, consolidation and streamlining of certain processes and procedures, reduction in working hours, implementation of employee profit sharing plans, an unemployment fund and the creation of company wellness facilities. H.S. Dennison was heavily focused on getting the highest quality work out of each of his employees and eagerly sought their advice and suggestions for improving working conditions and manufacturing processes. He employed market analysis and research when venturing into a new sales territory or rolling out a new product. His focus on industrial management led him to be a prolific writer, speaker, and expert advisor on the topic. Outside of his management of the company, he served as an advisor to the administrations of Woodrow Wilson and Franklin Roosevelt and lectured at Harvard Business School. Henry Sturgis Dennison served as president of the Dennison Manufacturing Company until his death in 1952. "Dennison's long time director of research and vice president, John S. Keir, was elected to succeed him in 1952. Keir only served for a short time, and continued running the company the way Dennison would have. After World War II, an emphasis was placed on manufacturing products that appealed to women, especially housewives. New products included photo corners, picture hangers, stationery, scotch tape, diaper liners and school supply materials for children. During the 1960s and 1970s, the Dennison Manufacturing Company began actively researching new products and proposed acquiring small, competing office product companies with new technologies. This effort was undertaken by president Nelson S. Gifford in order to diversify Dennison's product line, maximize profits for shareholders, and keep the company fresh. In 1975, Dennison acquired the Carter's Ink Company, a Boston, Mass. based manufacturer of ink and writing utensils. This acquisition and others broadened Dennison's product line as the company moved away from paper manufacture to a manufacturer of all office products. "Dennison Manufacturing Company merged with Avery Products in 1990 to become, Avery-Dennison, a global manufacturer of pressure sensitive adhesive labels and packaging materials solutions." If you'd like to learn more about Dennison, check out the Harvard collection. For more about the history of the family and its products, check out this historical overview from the Framingham, Massachusetts History Center, which holds the Dennison family papers and other collections related to the company. Finding Dennison's Bogie BooksThe Bogie Books can be hard to find these days. They are collector's items and sadly often disappear from library and archival collections. However, several issues from the 1920s have been digitized and are available for free on disparate locations around the internet. I've collected them here for your viewing and reading pleasure. If you'd like to see the covers for 1912-1925, check out the list at Vintage Halloween Collector. Dennison's Bogie Book - 1919 edition Dennison's Bogie Book - 1920 edition Dennison's Bogie Book - 1922 edition Dennison's Bogie Book - 1923 edition Dennison's Bogie Book - 1924 edition Dennison's Bogie Book - 1925 edition Dennison's Bogie Book - 1926 edition Dennison's has also reproduced many of its historic Bogie Books and they are available for sale as print copies. You can find them on Amazon by clicking the links below. If you purchase anything from the links, you'll help support The Food Historian! What do you think? Are you inspired to try some vintage decorations for your Halloween party this year? In 2019 I threw my own version of A Very Vintage Halloween party - check it out! The Food Historian blog is supported by patrons on Patreon! Patrons help keep blog posts like this one free and available to the public. Join us for awesome members-only content like free digitized cookbooks from my personal collection, e-newsletter, and even snail mail from time to time! Don't like Patreon? Leave a tip! Welcome to The Food Historian's 31 Days of Halloween extravaganza. Between social media (Facebook, Instagram, Twitter) and this blog, I'll be sharing vintage Halloween content nearly every day this month! References to Halloween during the First World War were few and far between but this little article caught my eye. Featured in the October, 1917 edition of the Ladies Home Journal, "We Must Have Some Pleasure in Spite of the War" by Virginia Hunt doesn't have much in the way of menu suggestions and recipes, but it does illustrate the typical ideas around Halloween parties at the time. A mixture of an excuse for teenaged romance, a little spookiness, and of course, the home economist's dream of a color-coordinated, crafty, event, sometimes with coordinated gymnastics. For fun, I've transcribed the original article verbatim below. Would you host a Halloween party with any of this advice?  Orange postcard featuring two witches adding ingredients to a cauldron - two smiling jack-o'-lanterns look on. Below reads, "Halloween Greetings - When the witches in their kettles Stir their magic brew tonight,-- May they bring forth things you long for -- May they cast your future bright!" Postcard c. 1920, Enoch Pratt Collection, Maryland Digital Collections. The Witch's Cave Every Halloween party has a witch, sometimes several witches, flitting scarily here and there with abroomstick, or hovering over a kettle or presiding at a fortune-telling tent. At this part, however, the witch is the chief attraction and the source of all the entertainment. A big room, garret, hall, vestry of a church or possibly a barn or a garage would be suitable for the scene of the party, only one room being required. Instead of the usual booths, tents, tables, etc., the whole apartment is made to represent a witch's cave. Branches and limbs of trees, leaves, cornstalks, etc., are used in profusion, covering walls, hanging from rafters and strewn on the floor. Bats made from stiff paper are hung from the ceiling, rafters or chandeliers, low enough to brush against people as they pass by and add to the creepy effect. The more twigs, branches, stalks, etc., that are used the more ghostly will be the effect of the flickering lights through the branches and the shadows cast here and there. At one side of the room, or in a corner plainly seen from everywhere, is placed the witch's kettle, over which a very scary-looking witch presides. Underneath the kettle a make-believe fire is arranged with red electric lights or a red lantern showing the light through small twigs. On each side of the witch, a little back of her, stand two ghosts, sentinels and helpers of the witch. A black cat should be the witch's constant attendant; and she should carry the usual broomstick. The lighting of the hall or room is furnished entirely by jack-o'-lanterns or candles, although electric lights very heavily covered with red and green cloth or paper may be used, the weird ghostly effect being desirable. Ghosts are stationed here and there about the room and flitting in every direction. An orchestra or talking machine plays weird, doleful music until the guests have all assembled. Each guest, upon entering, is conducted about the room by a ghostly attendant, shakes hands with clammy-handed figures and hears doleful groans, until his arrival at the witch's kettle. Here the witch, after mumbling a charm over her kettle, draws therefrom a slip of paper on which is written a fortune. The person receiving the slip is not at first able to see anything on the paper, but upon being told to hold it in front of a candle the writing plainly appears. This feat is accomplished by writing the fortune with lemon juice, which does not show on the paper when written, but appears plainly when heated. After all have received fortunes the company is seated on low seats scattered here and there about the room. The music gives a particularly doleful wail and then stops, and in a sepulchral voice the witch announces that she will call forth from the land of gloom some spirits who will entertain the company for a short while. She then waves her wand and out from behind some curtains, which have been hung in one corner among the branches and stalks, there appears, as ifby magic, a procession of ghosts. They march in slowly to the tune of "John Brown's Body," singing as they march and executing a ghost slide or march. After the ghosts disappear the witch calls forth the "Lightning Bugs," little, darkly clad figures, so dark that they can scarcely be seen, each one carrying a flashlight. The hall should be as dark as possible for this act, as only the flash of the lights is desired to be visible. These lightning bugs go through a simple gymnastic drill with the flashlights, ending with a quick march. This act is very effective if done in time to rather slow music and, with considerable practice, will be a very pleasing addition to the entertainment. It is, however, absolutely necessary to have the hall dark throughout this stunt. The lanterns may be extinguished and all lights turned off, then lighted again at the close. The flashlights should be turned off now and then and turned on again quickly to give the lightning-but effect, although the exercises with the arms and the quick march will give that effect to some extent, the lights bobbing here and there in the dark. After the lightning buts have disappeared the lanterns are lighted and the witch calls forth the Pumpkin Quartet. These are four girls dressed in yellow cheesecloth or cambric dresses with long twisted pieces of green crepe paper on their heads, to represent the stems of the pumpkins. This act should have more light, which can be accomplished if desired by light thrown directly on the quartet. The quartet then sings several songs - preferably soft, harmonious four-part songs, such as lullabies and Southern melodies. If such talent is available there may be banjo or guitar accompaniments to these songs, the instruments to be played by ghostly figures or by other pumpkin characters. Then the quartet disappears and the witch waves her wand again. This time out come tripping, to light, swingy music, two little fairies dressed all in white with gauzy, silvery wings on their shoulders and wands in their hands. They stand on each side of the curtains, holding their wands to make an arch. Then the music plays a slow march and out from the curtains appear all the performers who have taken part in the entertainment, marching between the two fairies and forming in a half circle facing the audience, with an opening in the center of the half circle. Next the fairies hold their wands at salute and the music strikes up "Columbia, the Gem of the Ocean," while out from the curtains marches Columbia, carrying an American flag. She marches to the center of the half circle, the fairies leading the way, and the whole company of performers close the entertainment with the singing of "The Star-Spangled Banner." An Impromptu Barn Party A Puritan maiden called at various houses and, from a hollow pumpkin shell she carried, drew a corn husk which she gravely presented to whoever opened the door. The finest, softest, inside husks had been chosen; a pen-and-ink sketch, "three lines and a splash," of cat or witch or goblin pointed with fine dramatic gesture to the rime: Ghosts do dance And goblins prance In our barn to-night. Don't make much fuss, But join with us, With hearts both gay and light. When the guests arrived they were seated on piles of hay; a shock of corn was thrown before each one, and at a signal the corn husking contest began. Old-time tricks and games were then tried with great zest. The tables were decorated with pumpkin shells filled with fruit. The place-cards were corn husks; nut dishes were hollowed apples. The salad was of cottage cheese in individual services, each being shaped like a face with raisin eyes and pimiento mouth and nose. The sandwiches were of brown bread cut as witches' hats. A large cake was frosted with chocolate and on its dark background sheeted ghosts and spirited goblins in white-icing garments disported in perfect harmony. Candies and nuts ended the feast. Illustrated Novelties for the Parties The two illustrations at the top of the page and the two witches at the bottom are figures about six inches high and may be used for table decorations. A Halloween part invitation is shown both folded and unfolded. These sell for five cents each, and in orange and black are striking in appearance. Immediately below these are button-faced figures on a card to be used for an invitation or a place-card. The witch on the right and the fireplace at her right and the open gate below are given as examples of what may be done by the clever girl who can paint. In her basket the witch carries a real folded note of invitation; the kitty is real fur or felt and the garden gate actually swings on its hinges. The combined place-card and nut-cup favors may be purchased for about five cents each in shops selling such goods. Well! The Witch's Party certainly seems like it would be a LOT of work to organize and put on, requiring quite a few actors. The patriotic ending featuring Columbia, while seemingly out of place among a Halloween production, was typical of the period and boosterism for the war effort. That being said, the adorable barn party seems much more doable, provided one can find corn for husking! What do you think? Would you add any of these ideas to YOUR Halloween party? And here's a little bonus - a fun page of paper dolls from that same issue of the Ladies' Home Journal! Which costume would you wear? The Food Historian blog is supported by patrons on Patreon! Patrons help keep blog posts like this one free and available to the public. Join us for awesome members-only content like free digitized cookbooks from my personal collection, e-newsletter, and even snail mail from time to time! Don't like Patreon? Leave a tip! Welcome to The Food Historian's 31 Days of Halloween extravaganza. Between social media (Facebook, Instagram, Twitter) and this blog, I'll be sharing vintage Halloween content nearly every day this month! Pop culture these days seems dominated by arguments over whether or not the pumpkin spice latte (or PSL) is "basic" or not, whether or not enjoying pumpkin spice flavored things can only happen during the few short months of autumn, and whether "fall creep" plays a role in "ruining" some people's summers. But have you ever wondered WHY we eat pumpkin pie spice - and other sweet spices - mostly in the fall? Pumpkin pie spice is a mixture of sweet spices - cinnamon, nutmeg, ginger, and either cloves and/or allspice. With the exception of allspice, all of these spices are native to Southeast Asia, especially the so-called "Spice Islands," more commonly known as the Maluku Islands (or Molucca Islands) near Indonesia, where nutmeg trees (which also provide mace) and clove trees originated. Cinnamon is native to Sri Lanka, and ginger is native to Maritime Southeast Asia. Allspice is also a plant of the tropics, native to the Caribbean and Central Mexico. So why do we so strongly associate these flavors with cold fall and winter months in the Northern hemisphere? A Brief History of the Spice Trade This map of the Moluccas Islands was published in 1630 by Willem Jansz. Blaeu (1571-1638). This map clearly shows that very little was known at the time about the Indonesian Archipel. The map shows the islands close together though in reality they are often thousands of miles apart. From the collections of the Koninklijke Bibliotheek. As with many things, it all has to do with money. Prior to the 16th century, all of these spices were available in Europe traveling via trade routes across Asia. Chinese and Arab traders traveled overland via the Silk Road or on ships from the Red Sea across the Indian Ocean. Cinnamon, ginger, and black pepper (native to the Malabar coast of India) were all known in Europe as far back as Ancient Rome. For centuries, Venice controlled much of the flow of spices into Europe, and the wealth gained by the spice trade may have helped spark the Renaissance. But when the Ottoman Empire wrested control of the spice trade from Europeans in 1453, things changed. European nations, spurred by improvements in naval technology, started to search for their own routes to control the lucrative spice trade. Indeed, most of the European "explorers" who ended up in the Americas were searching for a shortcut to Asia and a way to bypass the control of the Muslim Ottoman Empire and cut out the middleman altogether, ensuring massive profits. Instead of dealing with existing trade relationships, as Asian and Arab traders had for centuries, Europeans simply took what they wanted by force. The Dutch were particularly violent as they tried to take control of the Spice Islands through genocide and enslavement. Even after the plants that produced these valuable spices were successfully propagated outside their native habitats, the plantations which grew them commercially were often owned by foreign Europeans and also used enslaved labor to produce the spices more cheaply than ever. Like sugar and chocolate, the plantation economy allowed spices to be produced in massive quantities quite cheaply. The flavors that were once the purview only of wealth European aristocrats were, by the end of the 18th century, much more widely affordable by ordinary people. By the middle of the 19th century, ginger, cinnamon, nutmeg, mace, and cloves (along with sugar and cocoa) were positively common. Which is why foods like gingerbread cake, spice cake, and spiced pumpkin and apple pies became such indelible parts of American food history. But why the association with fall? In European cuisine, the most expensive foods were served around special feast days, like Christmas and Twelfth Night. Fruit cakes were rich in spices, spices flavored custards and puddings, and cookies flavored with ginger, cinnamon, mace, nutmeg, and cloves were all staples of the winter holidays. As spices became less expensive over time, they were used in other applications, but their association with the holidays - and cold weather - continued. In the United States, Americans flavored the prolific native squash with the now-familiar mixture of spices in a smooth custard pie. Pumpkin pie was born. Creating "Pumpkin Pie Spice"The name "pumpkin pie spice" refers to the mix of spices used to flavor pumpkin pies - among other things. Sadly, the mix itself contains no actual pumpkin, which is quite confusing when it is used as a flavoring agent sans pumpkin. Developed to flavor the smooth squash custards in a flaky crust we've all come to associate with Thanksgiving, the mixture of sweet, exotic spices was extremely popular. But as the 19th century turned to the 20th, the idea of hand grinding whole spices in a mortar and pestle was not only time-consuming, it threatened the use of spices altogether. Spice and extract companies like McCormick had been around since the late 19th century, but the 20th century brought a whole host of other companies to the scene, especially post WWII. The spice mix itself was commercialized first during the early 20th century, as spice and flavorings companies brainstormed ways to make baking easier and more economical for customers. Thompson & Taylor spice company was the first to create "ready-mixed pumpkin pie spice." The above advertisement, first published in 1933, features a woman asking an older woman with glasses "Mother - Why is it your pumpkin pies are never failures?" The older woman, who is spooning something into a pie crust, answers, "T&T Pumpkin Pie Spice my dear, makes them perfect every time." The advertisement goes on to read, "Home-made pumpkin pie, perfect in flavor, color and aroma, demands the use of nine different spices. The spices must be exactly proportioned, perfectly blended, and, above all, absolutely fresh. For reasons of economy, most housewives are right in hesitating to buy nine spices just for pumpkin pie. But here is news! Now, for the fist time, you can get the necessary nine spices, ready-mixed for instant use, in one 10c package of T&T Pumpkin Pie Spice - enough for 12 pies." Of course, they don't want to tell you what those nine spices are! But likely it was a mixture of cinnamon, ginger, nutmeg, allspice, and cloves, and perhaps also mace, cardamom, star anise, and black pepper. Two years later, McCormick advertised their own "Pumpkin Pie & Ginger Bread Spice," a blend of "ginger, cinnamon, nutmeg, cloves and other spices." I love that it is advertised as good for both pumpkin pie and gingerbread. Although we often associate gingerbread with Christmas, it was also often served at Halloween and throughout the colder months. As canned pumpkin grew in popularity in the 20th century, other pumpkin desserts were also developed to use the same spice profile, including pumpkin spice cake. Here's the recipe as written in the St. Louis Dispatch. Feel free to substitute shortening (and the margarine!) for butter. Pumpkin Spice Cake 1/2 cup shortening 1 cup sugar 2 eggs 1 cup canned pumpkin 3 teaspoons baking powder 2 cups flour 1 teaspoon cloves 1/2 teaspoon nutmeg 2 teaspoons cinnamon 1/4 teaspoon salt 1/2 cup chopped dates 1/2 cup rich milk METHOD: Cream shortening and sugar, add eggs, one at a time, and beat well, then stir in pumpkin. Sift dry ingredients and add alternately with milk. (If pumpkin is very dry, add more milk.) Stir in dates and bake in a loaf, in a moderate oven, 350 degrees Fahrenheit. To serve, slice thinly and spread with margarine. Delicious for tea. Spiced pumpkin foods were largely relegated to desserts for most of the 20th century - pumpkin bars, cakes, muffins, and cookies were all popular, especially after the Second World War. But we weren't at peak pumpkin spice saturation just yet. Enter, the Pumpkin Spice Latte. The Pumpkin Spice Latte and BeyondFounded in 1971 near Pike Place Market in Seattle, Washington, Starbucks originally started as a whole bean coffee company. But the specialty coffee business caught on in the dot com boom of the 1990s and franchises spread all over the country. In the 1980s, Starbucks had developed the popular holiday eggnog latte. The addition of a peppermint mocha in the early 2000s piqued corporate interest in specialty holiday drinks available for a limited time. They trialed a variety of drinks with focus groups, and the pumpkin spice latte was the surprise favorite. Released in 2003, it became a national phenomenon that only grew with time. Starbucks was not the first to develop a pumpkin spice flavored latte, but they certainly popularized it. Nowadays September and October bring the onset of just about everything pumpkin spice flavored, regardless of the weather conditions where you live. And that's the weird thing about pumpkin spice - today it is totally divorced from its geography and history. Born in the tropics, the product of genocide, enslavement, and greed, and associated for centuries with wealth and holidays, today it represents shorthand for a near-fictional concept of autumn that most Americans don't experience. Even in stereotypical New England, where pumpkin pie spice was arguably born, climate change is making autumn shorter and warmer. I'm all for letting people love what they love, and PSL and pumpkin spice are no different. I love a good spiced pumpkin dessert, don't get me wrong. But for all the fuss about pumpkin spice, I'm an apple cider girl myself. Just don't tell Starbucks or the people who seem to think everything from breakfast cereals to hand soap should be flavored with pumpkin spice. What do you think? Are you a fan of pumpkin spice? Tell me how you really feel in the comments! And if you want to learn more about the history of pumpkin pie, check out my talk "As American As Pumpkin Pie: From Colonial New England to PSL" - available on YouTube. The Food Historian blog is supported by patrons on Patreon! Patrons help keep blog posts like this one free and available to the public. Join us for awesome members-only content like free digitized cookbooks from my personal collection, e-newsletter, and even snail mail from time to time! Don't like Patreon? Leave a tip! In 1943, the USDA published the informational booklet Hunger Quits School. On December 5, 1942, President Franklin Delano Roosevelt signed an executive order creating the Food Distribution Administration, which oversaw, among other things, the school-lunch program. School lunch was influenced in part by the military draft. As many as a quarter of recruits were rejected for military service due to malnutrition. The panic around military readiness lead to many advancements in nutrition science and education of ordinary Americans about nutrition, including the development of the Basic 7 nutrition recommendations and yes, even school lunch. I've transcribed and shown the booklet in its entirety for your reading pleasure and edification. As you read you'll see how clearly school lunch programs were tied to military readiness even in the period, as well as how their execution differed in various communities. If you'd like to learn more about the history of school lunch, scroll to the bottom for reading recommendations. "Hunger has quit 93,000 schools throughout the United States where programs to provide noonday meals to students are operated by local communities in cooperation with the Food Distribution Administration. These programs are providing wholesome food to those who need it most - they are helping to build a healthy and physically fit population. Shortages of certain commodities cannot be permitted to impair the welfare of our future citizens. It is imperative that the youngsters who most need nourishing food get it in their school lunch. War adds to the urgency of the task. "A physically fit population and properly managed food supply are essential now more than ever before. Obviously, school-lunch programs are not substitutes for the courage of fighting men, for a fleet of airplanes, for guns, ships, tanks, or for the purchase of war bonds and stamps. Nevertheless, they are important in the Nation's War effort, since in modern total war the requirements for victory are indivisible." Images to left of text: Stylized black and white warship "Ships must transport food," stylized soldiers in a mess tent "Soldiers must eat," stylized workers in a factory with lunch room "Workers must eat," stylized woman typing and separate building with family in kitchen "Civilians must eat," stylized children sitting at table with knives and forks "Our children must eat." "WHY COMMUNITY SCHOOL-LUNCH PROGRAMS? "From the standpoint of the local community the reasons for operating lunch programs in the schools are immediate and easy to understand. Mothers and fathers, teachers and school administrators, doctors and health officers, and others in the community know the importance of having children eat properly. Since most children are away at school during lunch time for most of the year, the school lunch is an important part of the total diet of the individual. "Because parents, teachers, and others know the importance of proper food, that doesn't necessarily mean that all school children get the right kind of lunch or any lunch at all for that matter. In many cases, parents don't have enough money to put the right kinds of food in their children's lunch pails. In some cases - and this is increasingly true as more women go into war work - parents just don't have the time to put up the right kind of lunch for their children. In other cases, parents aren't well enough informed about nutrition to prepare an adequate lunch for their children. "All these and other factors have prompted local people to establish school-lunch programs as community enterprises. Programs are currently in operation to provide noonday meals to children in schools in every State and the District of Columbia, Puerto Rico, and the Virgin Islands. Thousands of persons - parents, teachers, volunteer workers, and well as paid workers - are giving their time and effort to carry on these projects, and millions of children are benefiting. "Although the Food Distribution Administration of the United States Department of Agriculture cooperated in school lunch programs in 93,000 schools during the 1941-42 school year by furnishing various foods without charge, the major responsibility for initiation of each program and for its successful operation is a community responsibility." Images to the right of text: Above, photo of young white boy outside a school eating a sandwich "The Cold Sandwich is no substitute." Below, photo of white children eating soup at a long table, caption continues ". . . For a Well-Balanced Hot Lunch." "METHODS OF ORGANIZATION DIFFER Just as there are tremendous variations in the types of communities, so are there considerable differences in the types of school-lunch programs. The complex organization of city life may find a parallel in the organization of the school lunch program in a large metropolitan area. In one large city, food for the lunch program is prepared in a big central kitchen. Hundreds of workers are engaged in such jobs as meal planning, food preparation, and dishwashing. From this central kitchen the food is delivered in heat-retaining containers by truck to the individual schools, where it is served to the children in lunchrooms. The children who can afford to pay for their meals do so with coupons which they buy at the school; those who cannot afford to pay are given coupons without charge. "The less complex pattern of life in rural areas may likewise be reflected in the organization of the school-lunch program. In one rural one-room school - and there are many of them in the United States - the children of the school bring various foods, such as potatoes and other vegetables, and seasonings from home. The teacher, with the assistance of the older students, prepares a single hot dish, usually a soup, a stew, or a boiled dinner. This hot dish is supplemented with foods which lend balance to the meal and can be eaten without cooking, such as citrus fruits or apples. The children set the tables and wash the dishes when the meal is finished. "These are but two of the many ways in which school-lunch programs are carried on. In operation they look easy. The routine is like clockwork. Each participant knows his job and does it. But even the most simple school-lunch project requires careful planning and hard work. Its successful operation depends on the continuing active interest of the local community." Images to left of text: Top, black and white photo of white adult women helping white students at lunch table, "The teacher, with the assistance of volunteers in the community, prepares the lunch." Bottom, black and white photo of open kitchen with white women cafeteria workers and line of white children, "Full-time workers prepare the food in a central kitchen from which it is delivered to the individual schools." "HOW TO GET STARTED IN YOUR COMMUNITY "Suppose the school in your community does not have a lunch program and you would like to see one in operation. How do you go about getting it started? "The first thing to keep in mind is that this is a job for your local people - yourself and your neighbors. Various agencies of the Government may lend you technical assistance, but the primary responsibility is yours. "If you have the interest and the willingness and the perseverance to follow through on a community lunch program, the thing to do is to get together with your neighbors, the parents of other school children, and see how much interest you can arouse and how much support you can get for the proposal. You will need much support if your plan is to be a success. "What you do next depends on what kind of community you live in. The procedure in a city of 100,000 population is different from that in a rural area. The steps to take are different in a city of 20,000 from those in a village of 2,000. But the procedure that has been followed in these different types of communities will give you an idea of what lies ahead in your effort to get started. "In one city of more than 100,000 population a group of mothers presented their proposal for a school-lunch program to the teachers and the principal of their neighborhood school. They were given a sympathetic hearing and arrangements were made to present the plan to the city superintendent of schools and the board of education. The meetings resulted in a survey to ascertain what facilities were available in the various schools for the operation of a lunch program on a city-wide basis, what additional facilities would have to be provided, and what would be needed in the way of financing. "The survey completed, plans were laid to put the school-lunch program into operation. Some of the needed facilities were provided from public funds, and" [. . . continued on next page] Image to right of text: Black and white photo of seated white adults as at a public meeting, "This is a job for local people . . . yourself and your neighbors." [continued from previous page] "the remainder was purchased by a number of civic and fraternal organizations which took an interest in the project. A permanent staff of paid workers was hired, and their work was supplemented by the work of volunteers. Much of the food was purchased locally, but some was provided without cost by the Food Distribution Administration. Those children who could pay a nominal sum for their lunch did so, and those who could not afford to pay were fed without charge. "Teachers took the initiative in serving lunches at school in one village of 2,000. They had seen some children sitting out in the cold eating sandwiches and others having nothing at all to eat. Investigating the possibilities of doing something about it, they learned that a school-lunch project was in operation in a nearby community. At the next meeting of the parent-teacher association they brought up the idea of a school-lunch program. The result was the appointment of a committee to visit the neighboring village and see how the program operated there. The committee made an enthusiastic report at the next meeting, and it was decided to present the whole matter to the local school board. "After a number of conferences with representatives of the State welfare department, the FDA, and other interested groups, the school board agreed to formally sponsor the lunch program. A lunchroom was set up in part of the school basement which was not in use. The county home demonstration agent provided technical assistance in meal planning. Two full-time paid workers were hired, and the rest of the labor forced was made up of volunteers. "The entire community, in one rural area, pooled its efforts to get a lunch program going in its one-room school. It was a real job, as the school lacked" [. . . continued on next page]. Images to left of text: Top photo, white adults gather around a table looking at papers "Parents and school authorities discuss a proposed school-lunch program." Bottom photo, white adults sit in auditorium, "Civic and fraternal organizations play an important part in the success of many school-lunch programs." [continued from previous page] "everything in the way of facilities and had no available space for cooking or serving. The men of the community solved the problem by getting together enough salvaged lumber and building a lean-to addition to the school, also tables and benches. The women of the community meanwhile organized a shower to collect the necessary pots, pans, and other cooking utensils. A merchant in the nearby town donated a second-hand stove. Each child brought his dishes and "silver" from home. Each family provided foods, and the mothers took turns going to the school to do the cooking. The school board, of course, approved the undertaking and formally sponsored the program to make it eligible for FDA assistance. "Should you contact anyone else for help in getting a school-lunch program going in your community? There is no one answer. In many counties there are home-demonstration agents, home-economics teachers, and home supervisors of the Farm Security Administration who can supply technical advice and assistance. Parent-teacher organizations, civic organizations, chambers of commerce, veterans' organizations and auxiliaries, State and local education departments, State and local health organizations, State and local welfare agencies, and the WPA are among the groups which have helped in other communities. In many cities there are representatives of the Food Distribution Administration who can supply information and advice regarding procedure for obtaining reimbursement from the FDA for the purchase of specified foods. "Your first objective in getting a school lunch program started is, of course, better meals for the children in school. This, too, was the main objective in the thousands of communities which are now operating the programs. These communities have found that many benefits to the children in school have stemmed from better nutrition." Images to right of text: top photo, white women stand next to table of plates of food, actively plating, "Teachers took the initiative in serving school lunches in a small community. Bottom photo, two white women stand in kitchen cooking, "Lunches like this mean more adequate diets for millions of children every day." "BETTER NUTRITION NOT THE ONLY BENEFIT "Records kept in many schools show that attendance is better after a school-lunch program is put in operation than it was before. One school reports 11 percent fewer absent than before the lunch program was started, another 8 percent; and still another 15 percent. Investigation shows that in many cases the better attendance is the result of less illness. Proper food does much to prevent illness, especially in growing children. "Thousands of doctors and dentists have gone into the armed forces. War needs have taxed our health facilities all along the line. It is more important than ever that as much illness as possible be prevented. To the extent that school lunches keep children healthy they are making a direct contribution to the welfare of the Nation at war. "There are many striking reports of children who have been built up physically as a result of eating school lunches. In one midwestern community an undernourished boy gained 25 pounds during a single school year. Many examples like this could be cited. Not only such run-down children, but in many cases the entire class of a school reports better physical fitness as a result of school lunches. "Many prominent health authorities have pointed out that it is a waste of the taxpayers' money to try properly to educate children who are malnourished. They simply cannot do good work when they are hungry. Such records as have been kept show that in almost every school where adequate lunches are provided the students are making better progress in their studies than formerly. "Teachers report that students are better behaved when they are properly nourished. Eating together in groups improves the table manners and the per-" [. . . continued on next page] Images to left of text: Top photo of white men administering vaccinations to other white men, "Thousands of doctors and dentists have gone into the armed forces." Bottom, young white children play on equipment outside, "Keeping children healthy is a direct contribution to the welfare of the Nation at war." [continued from previous page] "[per]sonal habits of many youngsters. Through the example of watching their schoolmates eat certain foods, children come to like foods previously unfamiliar. They eat what is put on the table. "In many communities the benefits of the lunch program are carried into the home. Children have reported back to their mothers the things that they learn about diet and better nutrition, with the result that the meals of whole families frequently have improved. "It is apparent that these benefits to children are all good reasons for parents, teachers, and local communities to be interested in school-lunch programs. How about the Federal Government and the Food Distribution Administration? "FDA'S PART IN SCHOOL-LUNCH PROGRAMS "One of the important jobs of the FDA is to assist in the management of the Nation's wartime food supply through the stimulation of increased production, the maintenance of machinery for orderly marketing, and the prevention of waste. School lunches, in addition to feeding those who most need proper nourishment, are one of the devices used in helping to do these jobs. "In recent months the war effort has made it necessary not only to maintain existing levels of food production but to increase these levels greatly. Although there has been a tremendous expansion in food production during the past year, some production goals have been revised upward. Under these conditions, when concerted efforts are being made to increase food production, it is important that farmers be able to market all they grow. Market stability is thus an important factor in stimulating increased production. "Not only is market stability important as an incentive to ever increasing output, but it is important in guarding against waste of food already produced." Images to right of text: top, a white farmer stands in the furrows of a field with sacks of potatoes, "It is important that good use be made of all that farmers produce." Bottom, two white men shake hands outdoors, "Sponsors buy from local producers and are reimbursed by the Food Distribution Administration." "In the past unstable markets sometimes made it impossible for farmers to harvest their entire crop and sell it at a price that would cover their costs. The result, when such conditions prevailed, was that part of the crop was not harvested but was left in the fields or in the orchards to rot. Such conditions might arise again for some commodities, even though supplies of certain other foods may be short, and if they do the school-lunch programs are a mechanism to prevent possible waste. "Sometimes food purchased originally for shipment abroad under the lend-lease program could not be used for this purpose because of changed requirements of our allies, lack of shipping space, or other uncontrollable factors. In such cases the school-lunch program provided a desirable outlet for the commodities. "In the past, the FDA's job in connection with school-lunch programs was to buy up foods and to channel them to schools for use by the youngsters who needed them most. Purchases were sent in carlots to the welfare departments of the various States. The State welfare department distributed foods to county warehouses which in turn distributed part of the supply for use in lunch programs in eligible schools. "Shortages born of the war - transportation, equipment, manpower - necessitated a revision of this distribution plan. In some large communities, commodities are still distributed to schools from warehouses operated by State welfare departments, but in most communities the program is now carried on under a local purchase plan. "Under this new local purchase plan, the FDA reimburses the sponsors for the purchase price of specified commodities for the lunches. The commodities eligible for purchase under the plan are given in a School Lunch Foods List which is issued from time to time. Products in regional abundance and those high in nutritional value have first consideration in compiling the lists. Sponsors buy from producers or associations of producers, or from wholesalers or retailers. They are reimbursed for the cost of the commodities up to a specified amount" [. . . continued on next page]. Images to left of text: top, two men load stack barrels, "A few foods are still available from the FDA for delivery to schools in some areas." Bottom, box trucks lined up outside a building as a man loads a box, "Sponsors arrange for the delivery of foods to the schools where they are used." [continued from previous page . . .] "which is based on the number of children participating, the type of lunch served, the financial resources of the sponsor, and the cost of food in the locality. "In addition to those foods for which the FDA provides reimbursement of the purchase price, local sponsors buy with their own funds such additional commodities as are needed to round out the meals. What better use can be made of some of our food supplies than to make them available to growing children who otherwise may not get enough to eat? "WHAT SCHOOLS ARE ELIGIBLE? "Schools eligible to participate in the program must be of a nonprofit-making character and must serve lunches to children who need them. Schools receiving FDA assistance must permit no discrimination between children who pay for their lunches and those unable to pay. A formal sponsor, representing the school, must enter into an agreement with the FDA that the conditions governing the program will be complied with. Nonprofit-making nursery schools and child-care centers are eligible for participation in the program. "From the standpoint of our national welfare it is important that all school children be properly nourished, and that all food produced be properly utilized. This explains the interest of the Federal Government in the community school-lunch program, since the Government represents all the people acting in concert. "Although the school-lunch programs alone have not succeeded in reaching all children who need more adequate nourishment, they have been instrumental in bringing food to a substantial number of them. During the peak month of March 1942 the lunch programs in which the FDA was cooperating fed 6,000,000 children. Nor have the lunch programs alone succeeded in making possible the most effective utilization of all foods produced. But they have been one means of working toward these two objectives. "The lunch programs have been a means of forcing hunger out of a great many schools in the United States." Images to right of text: Top: young white girls at play on a see-saw. Middle: a school building. Bottom: a white nun gives a sandwich and bottle of milk to a young white boy. "FOR MORE INFORMATION ON HOW TO GET A SCHOOL LUNCH PROGRAM STARTED IN YOUR COMMUNITY WRITE TO THE NEAREST REGIONAL OFFICE OF THE FOOD DISTRIBUTION ADMINISTRATION "If you live in one of the following States: Main, New Hampshire, Vermont, Massachusetts, Rhode Island, Connecticut, New York, New Jersey, Delaware, Maryland, or West Virginia - Write to: Food Distribution Administration Regional Office, 150 Broadway, New York, N.Y. "If you live in Virginia, Kentucky, Tennessee, North Carolina, South Carolina, Georgia, Florida, Alabama, or Mississippi - Write to: Food Distribution Administration Regional Office, Western Union Building, Atlanta, Ga. "If you live in Ohio, Indiana, Michigan, Wisconsin, or Illinois - Write to: Food Distribution Administration Regional Office, 5 South Wabash Ave., Chicago, Ill. "If you live in Minnesota, Iowa, Missouri, Kansas, Nebraska, South Dakota, or North Dakota - Write to: Food Distribution Administration Regional Office, Old Colony Building, Des Moines, Iowa. "If you live in Arkansas, Louisiana, Oklahoma, or Texas - Write to: Food Distribution Administration Regional Office, 425 Wilson Building, Dallas, Tex. "If you live in New Mexico, Colorado, Utah, Idaho, Montana, or Wyoming - Write to: Food Distribution Administration Regional Office, 1536 Welton Street, Denver, Colo. "If you live in Arizona, Nevada, California, Oregon, or Washington - Write to: Food Distribution Administration Regional Office, 821 Market Street, San Francisco, Calif." And that is the end of the transcription! What did you think? Were there any surprises in there for you? I had known for a long time that the school lunch program was a way to use up agricultural surpluses AFTER the war, but hadn't realized that using up wartime surpluses was a factor since the beginning. I also liked the emphasis on treating children who couldn't afford to pay no differently than those who could. FURTHER READING: If you'd like to learn more about the history of school lunch, check out these additional resources. (Purchases made from Amazon links help support The Food Historian):

Happy reading! The Food Historian blog is supported by patrons on Patreon! Patrons help keep blog posts like this one free and available to the public. Join us for awesome members-only content like free digitized cookbooks from my personal collection, e-newsletter, and even snail mail from time to time! Don't like Patreon? Leave a tip!

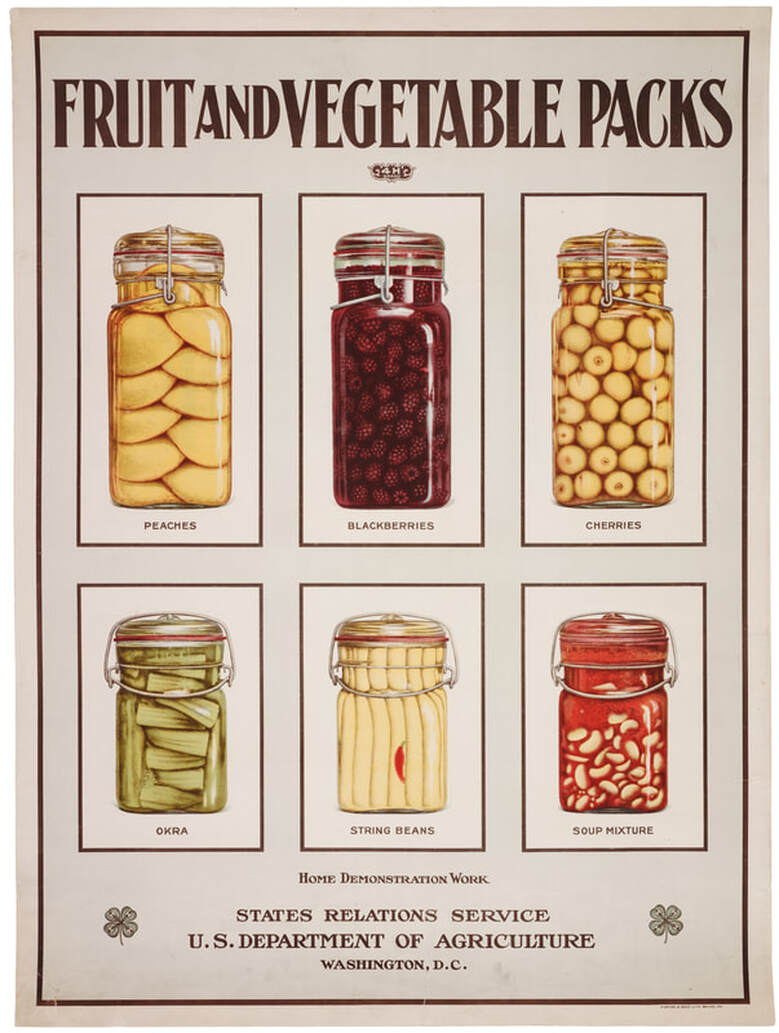

Home canning was promoted as essential to the war effort in both World Wars, but the First World War introduced ordinary Americans to a lot of research on the effectiveness and science of home canning. Although safe canning was still in its infancy (water bath canning low-acid vegetables was still sometimes recommended by home economists at this time, which we now know is not safe), approaching it with a scientific method was new to most Americans. This particular poster's purpose is unclear. Perhaps it was meant to demonstrate the best method of fitting fruits and vegetables into the jars. It is certainly beautiful. The unknown artist illustrated the clear glass wire bail quart and pint jars beautifully. Three quart jars are across the top containing perfectly layered halves of peaches, whole blackberries, and white Queen Anne cherries. Three pint jars across the bottom contain trimmed okra stacked vertically and horizontally, yellow wax beans (labeled "string beans"), which may have been pickled as a tiny red chile pepper can be seen near the bottom of the jar, and "soup mixture" containing white navy or cannellini beans and a red broth that likely contains tomatoes. Wire bail jars work by using rubber gaskets in between the glass jar and a glass lid to get the seal, held in place by tight wire clamps. Although beautiful, they are not recommended today for safe canning. They do, however, make effective and beautiful storage vessels for dry goods like flour, dried beans, spices, dried fruit, etc. (I recommend storing nuts in the freezer to prolong freshness.) Glass wire bail jars were common in the 1910s for home canning and became particularly important for the war effort as aluminum and tin became scarce due to their use in commercial canning and in wartime manufacturing. The poster interestingly includes vegetables in wire bail jars and even bean soup, which is not generally recommended to be canned with the water bath method. If the beans were pickled, they could be safely water-bath canned, but other low-acid vegetables like okra (unless also pickled) need to be pressure-canned to prevent the growth of botulism, a deadly toxin that can survive boiling temperatures. Although pressure canners existed during WWI, they were not in widespread use as they required the purchase of specialized equipment. Community canning kitchens were developed in large part to help housewives share the cost (and use) of more expensive equipment like pressure canners, steam canners, etc. This poster is from the United States Department of Agriculture (USDA) and is labeled "Home Demonstration Work," which indicates it may have been used by home demonstration agents, or trained home economists hired by the USDA, cooperative extension offices, or local Farm Bureaus to train housewives in best practices for home management, including food preparation and preservation. Home demonstration work was in its infancy during World War I, and expanded greatly after the war. What do you think the purpose of this poster is? Share in the comments! The Food Historian blog is supported by patrons on Patreon! Patrons help keep blog posts like this one free and available to the public. Join us for awesome members-only content like free digitized cookbooks from my personal collection, e-newsletter, and even snail mail from time to time! Don't like Patreon? Leave a tip!

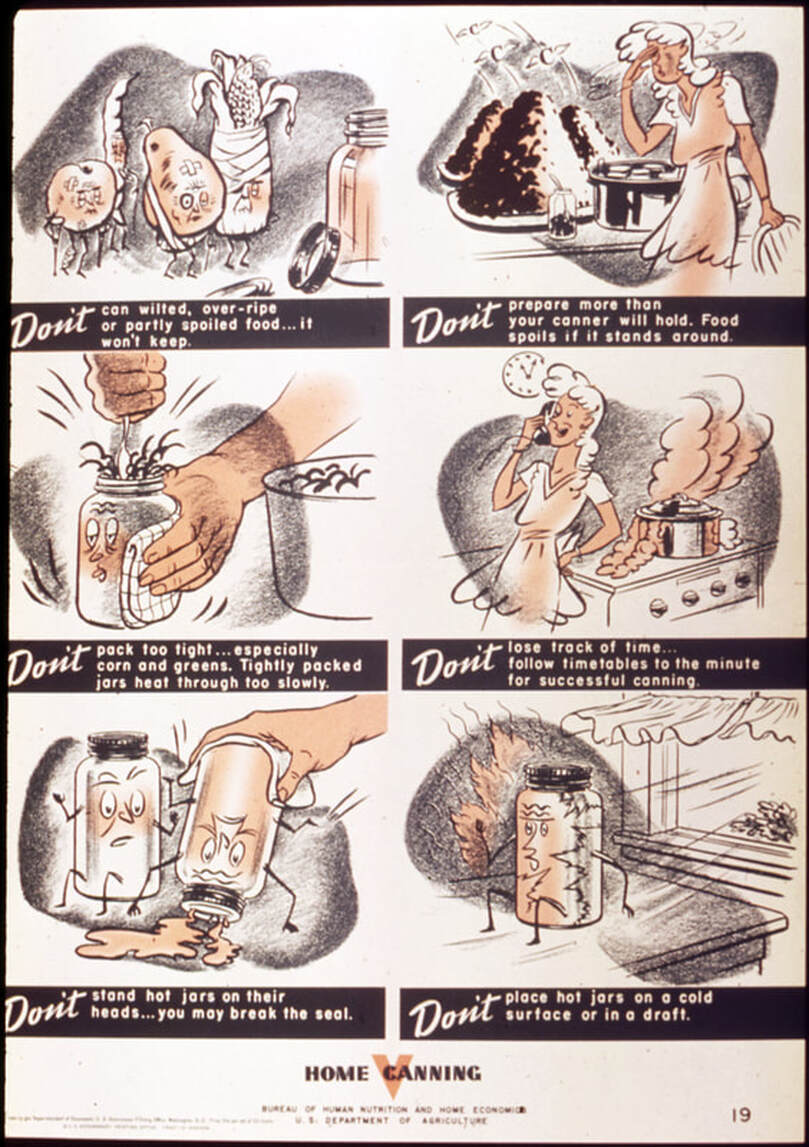

It's prime canning season! If you're facing a glut of tomatoes or more than ready for apple picking so you can make your own sauce, this post is for you. During both World Wars, home food preservation was vital to freeing up supplies of commercially canned goods for feeding soldiers and the Allies. But not everyone was used to canning at home, and even those who were experienced sometimes relied on unreliable or dangerous methods. For instance, my great-grandmother oven canned, which is no longer considered safe. And some folks still try to turn their jars upside down for a seal, which is not recommended. All canned foods work by creating a sterile vacuum seal. High-acid foods like fruit, tomatoes, and vinegar pickled foods can be canned in a water bath, where boiling water (212 F) kills bacteria and seals the jars. Low-acid foods like non-pickled vegetables and meats need to be pressure canned. The pressure canner increases the pressure inside the chamber, which allows water to boil at a much higher temperature. This kills all bacteria, including deadly botulism, and makes the low-acid foods safe to can. One of the ways home economists and the federal government tried to educate people about canning and food safety was through propaganda posters like this one. Here's the advice from the poster: "Don't can wilted, over-ripe or partly spoiled food... it won't keep." If you wouldn't eat it fresh, you shouldn't can it. Although lots of rhetoric during the war was about saving food and preventing waste, canning can only preserve, not restore the quality of food. Poor-quality ingredients makes for poor-quality canned goods, wasting time and effort. "Don't prepare more than your canner will hold. Food spoils if it stands around." Canning takes time, and leaving cut fruits or vegetables lying around waiting to be put into jars makes them more susceptible to collecting bacteria or spoiling. Canning depends on sterile jars and fresh ingredients. Although it can be tempting to work ahead, time your work carefully to avoid waiting. "Don't pack too tight... especially corn and greens. Tightly packed jars heat through too slowly." Canned goods need to be heated through entirely to create a proper vacuum seal and prevent the growth of bacteria. Especially for low-acid foods like corn and greens, proper heating is essential to successful canning. Tightly packed jars not only risked spoilage, they also wasted fuel as it would take them longer to heat through, if at all. "Don't lose track of time... follow timetables to the minute for successful canning." We've all been there. That's what kitchen timers are for. While over-cooking doesn't usually hurt, under-cooking can result in improper seals. Better to use the timer and be sure. Test kitchens and home economists and scientists developed the time tables to ensure a minimum amount of time in the boiling water bath or pressure cooker to ensure adequate seal and food safety. "Don't stand hot jars on their heads... you may break the seal." Although some people still do this to "ensure a good seal," a heat seal is not the same as a vacuum seal, and liquids touching the tops of the cans before they are fully cooled may break the seal and allow air and bacteria in, leading to spoilage. "Don't place hot jars on a cold surface or in a draft." They may break or explode. Seriously. This is also why canning jars need to be heated before filling - not only for sterilization, but also to prevent shock and cracks or breakage. Canning can be intimidating, and certainly time-consuming, but the push to get Americans to participate in home food preservation was a hard one. Although it can be difficult to balance the effort of canning with modern lives, the urgency of food preservation during World War II meant people carved out the time to make the effort. Do you can at home? I usually don't have the time, although nothing beats home canned applesauce (at least, my mom's style) and jam. A friend of mine keeps me supplied with amazing homemade jams. They're worth every penny. Especially since then I don't have to do the canning myself! Share your canning memories and stories (or horror stories) in the comments! The Food Historian blog is supported by patrons on Patreon! Patrons help keep blog posts like this one free and available to the public. Join us for awesome members-only content like free digitized cookbooks from my personal collection, e-newsletter, and even snail mail from time to time! Don't like Patreon? Leave a tip!