|

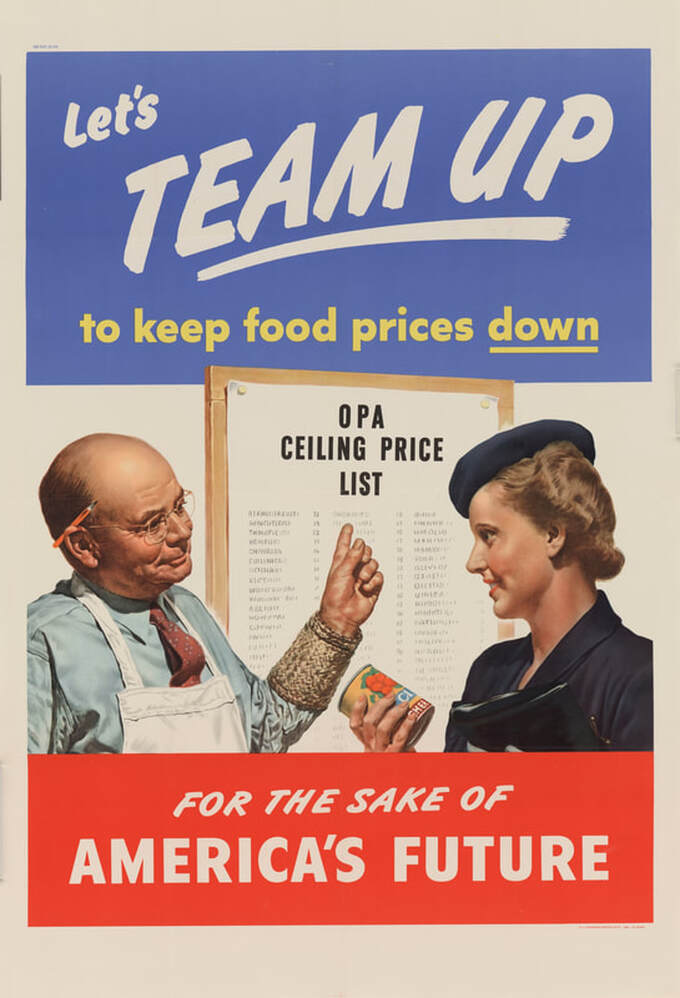

With all the talk of price increases and inflation these days, it's interesting to look to how these things were handled in the past. On a previous World War Wednesday, I talked about the differences between World War I and II and the "high cost of living," as it was called at the time. A big part of keeping prices affordable during the Second World War was not only mandatory rationing (it was voluntary in WWI), but also the Office of Price Administration (OPA) was able to freeze or set prices nationally for all consumer goods. Agricultural commodities were exempted from OPA control. Although the OPA was founded in 1941, it wasn't until 1943 that it settled on direct price control as the most effective means of regulation of consumer prices (The Oregon State Archives has a great overview of the OPA and price controls as part of an online exhibit on WWII). Although direct price control - "ceiling prices" they were called at the time - were extremely popular with the general public, retailers and especially manufacturers were constantly looking for ways around the regulations or to weaken them. The OPA used peer pressure and enlisted an army of housewives to report on those not adhering to regulations. This propaganda poster, one of many produced by the OPA, features a well-coiffed housewife holding a can of what appear to be tomatoes (or maybe cherries) smiling at a balding grocer, who in turn points rather wryly to a posted placard reading "OPA Price Ceiling List." The text of the poster read "Let's TEAM UP to keep food prices down for the sake of America's Future." Ceiling prices were published by the OPA and required to be posted in retail spaces, especially food, which was among the most price-controlled area of American life. Although small businesses could charge slightly higher prices than regional chains, the prices often differed by only a few cents, and were designed to help out the small businesses by giving them slightly higher profit margins. Much of the propaganda around price control and rationing both calls for cooperation between retailers and consumers, and this poster is no exception. Retailers were expected to follow regulations and consumers were expected to only patronize retailers who were following the rules. That didn't stop a huge black market from developing, especially around meat. Despite massive quantities of meat being used to feed the armed forces and sent overseas to support the Allies, ranchers and meatpackers were unhappy with price controls and in the aftermath of the war some actively withheld meat from the market in an effort to create false scarcity and anger voters, who would oppose the price controls. By the fall of 1946, meat production had fallen by 80%. Angry voters blamed the party in power - the Democrats - rather than the ranchers and packers who were colluding to manipulate the market, and delivered a Republican win in the election of 1946 - the first since 1930. The tension between food producers and food consumers has a long history. In the "free" market, farmers and ranchers are rewarded for low yields and production because prices go up. Getting producers to produce enough to feed people affordably while still ensuring they make a fair profit is a dilemma that plagued the early 20th century. Finally, during FDR's New Deal, government funds were used to subsidize farmers through low-interest farm loans and also direct payments to steady the supply on the market and protect farmland from the Dust Bowl. These were revoked in the 1970s under Nixon's Secretary of Agriculture Earl Butz of "get big or get out" fame. Instead, the government maintained an agricultural price floor - if the market price fell below the floor, the government would make up the difference to the farmer. So what happened? Of course prices instantly fell below the floor - because they could. Food manufacturers benefitted from purchasing commodity crops for less than they cost to produce, our modern processed food production flourished (to the detriment of our health), and taxpayers footed the bill. In the modern era, many economists (including at NPR) have used the jump in post-war inflation as the OPA was dissolved wholesale (instead of gradually increasing prices as economists of the period recommended) as proof that the OPA was always a bad idea, doomed to failure. But the people who hated the OPA the most seemed to be the people who stood to profit the most from inflation - the manufacturers, packers, and retailers who could pad their bottom lines with price increases in the name of "scarcity." Sound familiar? It seems to me as though the OPA, behemoth bureaucracy though it was, was more the victim of those determined to see if fail, at all costs, than a violation of the "natural order." Because although economists like to talk about scarcity driving up prices, they have very little to say about price increases that are not caused by scarcity, and even less to say about price increases on goods that people cannot afford to do without - like food and housing and healthcare. The tension between pro-business forces who oppose regulation and pro-consumer forces who support regulation date back to the 19th century in the United States. The conflict was present in the fallout from the Panic (and subsequent 7 year Depression) of 1893, in the industrial recessions of the early 20th century, and especially in the handling of the Crash of 1929 and subsequent Great Depression. FDR's New Deal and a dramatic increase in government regulation of business and the economy helped pull us out of the Depression (wartime defense spending didn't hurt either). But the OPA caused a strong negative reaction among the pro-business, anti-regulation groups that shifted politics back toward the myth of the "free" market. But while inflation did increase by as much as 20% after the OPA was dissolved, strong postwar wages helped mitigate the effects. Whereas wages in the modern era have largely stagnated for over a decade, especially for workers on the lower end of the economic spectrum. A few economists have discussed the morality of price gouging, but should we rely on the morals of businesses in a capitalist society? The tensions between pro- and anti-regulation forces are still at play in modern politics. After decades of deregulation, the Biden Administration has begun re-regulating or executing new orders on the environment, consumer protections, and immigration, but has yet to address the modern "high cost of living," although it is trying to reduce meat monopolies. But corporate consolidation has continued unchecked for decades, belying the "free market" and hurting consumers. It's a problem that won't be solved overnight. As prices for housing, food, healthcare, and other essential goods continue to rise, will we return to the lessons of the Office of Price Administration? That remains to be seen. I, for one, wouldn't mind a return to the "fair price" lists published in WWI. If politicians can't stomach a return to government regulations, maybe we can at least shame food corporations into sacrificing some of their record profits to ensure Americans have enough to eat. What do you think? The Food Historian blog is supported by patrons on Patreon! Patrons help keep blog posts like this one free and available to the public. Join us for awesome members-only content like free digitized cookbooks from my personal collection, e-newsletter, and even snail mail from time to time! Don't like Patreon? Leave a tip!

0 Comments

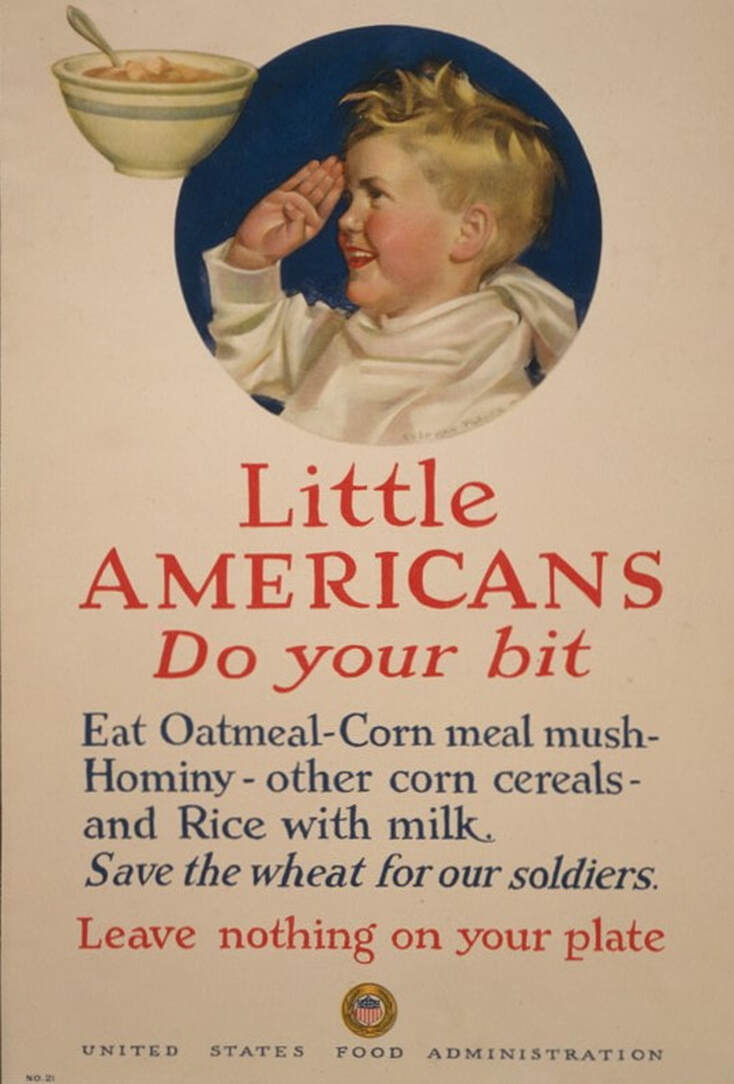

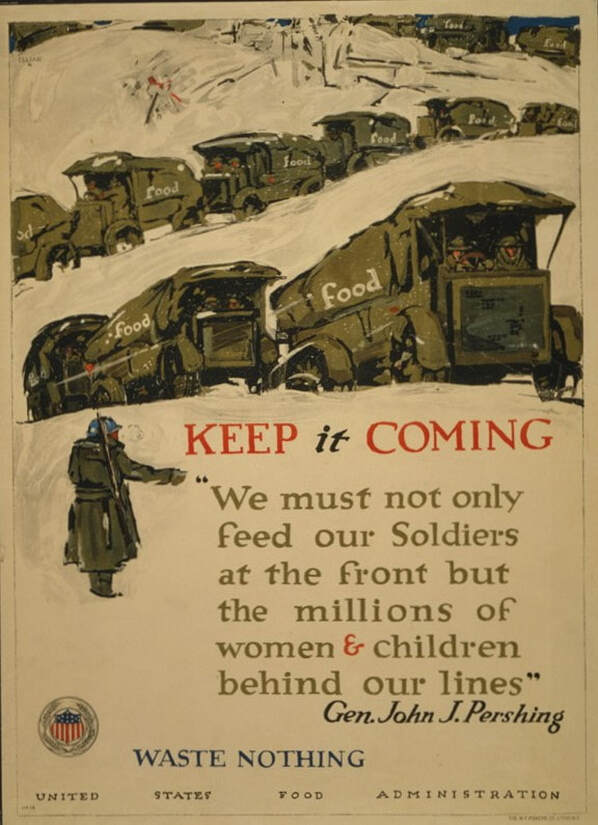

I was interviewed recently about breakfast cereals, especially corn flakes and the Kellogg brothers, so I thought for this week's World War Wednesday we'd take a look at this sweet propaganda poster from the First World War. "Little Americans - Do Your Bit! Eat Oatmeal - Corn meal mush - Hominy - other corn cereals - and Rice with milk. Save the wheat for our soldiers. Leave nothing on your plate" was designed by commercial artist Cushman Parker, who also designed covers featuring cherubic children for the Saturday Evening Post. This poster is interesting because the message is targeted specifically at children. Aside from the school garden movement, there weren't many food-related wartime posters directed to kids - this is one of the only ones. In this poster, a rosy-cheeked blond young man - who looks to be about five or six years old, salutes a floating bowl of hot cereal, a large white napkin tied around his neck as a bib. Although cold breakfast cereals were around at the time of the First World War, they were still considered less nourishing than hot cereals, especially for children. Oatmeal, Cream of Wheat (a.k.a. farina or semolina), and cornmeal or hominy mush were still popular at the breakfast table. Wheat was in short supply during the First World War, so ordinary Americans were encouraged to voluntarily restrict use to free up supplies for American soldiers and the Allies. That meant no more farina! As was true of much of the wartime propaganda, this poster calls for Americans to support the soldiers, doing without so "the boys over there" could have enough. Although Americans only entered the war in the spring of 1917, and it was over by the fall of 1918, wheat supplies continued to tighten throughout the war. By shifting eating habits to focus on other hot cereals, especially oatmeal and corn products like grits, Americans could help "do their bit" for the war effort. Rationing was voluntary for Americans, but Meatless Mondays and Wheatless Wednesdays still came to dominate American daily life. And children were no exception! Although advertising usually targeted the person who did the food shopping (usually the mother), this poster stands out as one targeting children directly, likely to help educate them about the needs of American troops and cut down on potential complaining, which might encourage parents to give into whining and purchase wheat products. The return of wheat, sugar, meat, and fats like butter and lard were a welcome herald to the end of the war. In this 1919 magazine advertisement, Rastus, the racist depiction of an African American cook used by Cream of Wheat packaging and advertisements for over 100 years before finally being removed in the fall of 2020, welcomes home American troops with an enormous bowl of Cream of Wheat - a sign of the end of rationing and likely an attempt to return Cream of Wheat to the tables of Americans who might have gotten used to eating other alternatives. The Food Historian blog is supported by patrons on Patreon! Patrons help keep blog posts like this one free and available to the public. Join us for awesome members-only content like free digitized cookbooks from my personal collection, e-newsletter, and even snail mail from time to time! Don't like Patreon? Leave a tip! This poster features a long string of Army green military trucks labeled "Food" snaking through snow-covered hills, directed by a soldier. It reads "Keep it Coming" and features a quote by Gen. John J. Pershing - "We must not only feed our Soldiers at the front but the millions of women & children behind our lines." Underneath reads, "WASTE NOTHING" with the seal and title of the United States Food Administration. Almost certainly printed in the winter of 1917-18, the poster was designed by artist George Illian. "Keep it Coming" was apparently Illian's first poster for the war effort. He went on to design several others for the United States Food Administration, but none as striking as this one. Sadly, I was unable to dig up any information on Illian other than he was a member of the Society of Illustrators and that he did some commercial art after the war. He died in 1932, but I have not been able to find an obituary. The imagery from the poster would not have been unfamiliar to ordinary Americans who had been following the news. By the fall of 1917, American soldiers were in the fields of Europe, led by General John Joseph "Black Jack" Pershing. After three years of brutal war, France and Britain welcomed the Americans, led by Pershing with open arms in June of 1917, but it was not until October of that year that the main bulk of the American Expeditionary Forces would arrive in France. Although the United States had officially entered the war in April of 1917, military personnel numbered under 200,000, and military supply and tactics were largely stuck in the 19th century. It took months of stop-and-start mobilization to train American troops (sometimes with wooden rifles) and get them overseas (on borrowed ships). The winter of 1917-18 was one of the worst in recent memory during the First World War. On December 29, 1917, the New York Times reported "Cold Snap Over Entire East," reporting temperatures in upstate New York as low as 20 degrees below zero. New York Harbor froze, railroads were backed up across the Eastern seaboard, and Europe was engulfed in snow and freezing rain. The weather conditions meant that nearly all of the supplies for Europe and for major Eastern cities were completely backed up. On December 30th, the New York Times reported coal shortages in New England and New York, blaming railroad backups and the requisitioning of civilian ships and tugs for the war effort. The railroad backups resulted in the nationalizing of the railroad system under William McAdoo. Illian's poster reflects the winter conditions on the front lines, too. Although the true horrors of trench warefare were often glossed over by the press, by 1917 many Americans were hearing from their "boys" overseas first hand. Marching in the abnormally frigid cold and torrential rains of the winter of 1917-18 in Europe was familiar to most of the soldiers. While the Eastern U.S. was brought nearly to a standstill by railroad blockages, coal shortages, and frozen ports, Britain, France, and Spain also experienced unusually cold temperatures, high snowfalls, and blocked railroads in December, 1917 and January, 1918. Like many of the propaganda posters of the First World War, "Keep it Coming" exhorts ordinary Americans not only to conserve food for American soldiers overseas, but also to help feed women and children in Allied nations. "Waste Nothing" was part of a campaign to reduce food waste and free up additional supplies to send overseas. American supplies of wheat in particular were low in 1917, and only by reducing consumption could food stocks be freed up for shipment overseas until farmers could increase production. The idea of personal self-sacrifice was part of a larger movement during the war to fund the war effort (through the sale of liberty bonds) and to "do your bit" to help the war effort. By using the wintry backdrop, Illian brought home the message that while Americans might be suffering from cold at home, things were worse in Europe, and American soldiers were doing all they could to help end the war and alleviate hunger and hardship among people who had already suffered four long years of war. 1917-18 would be the only winter warfare most Americans would see in Europe - the war officially ended in November of 1918 - but while millions of soldiers were sent home after Armistice, many Americans would remain in Europe until the summer of 1919, part of the demobilization efforts and cleanup (including burial duty) after the war. The Food Historian blog is supported by patrons on Patreon! Patrons help keep blog posts like this one free and available to the public. Join us for awesome members-only content like free digitized cookbooks from my personal collection, e-newsletter, and even snail mail from time to time! Don't like Patreon? Join with an annual membership below, or just leave a tip! Tip Jar

$1.00 - $20.00

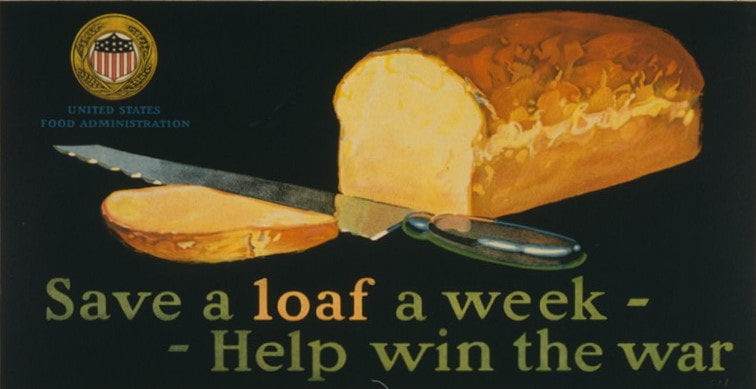

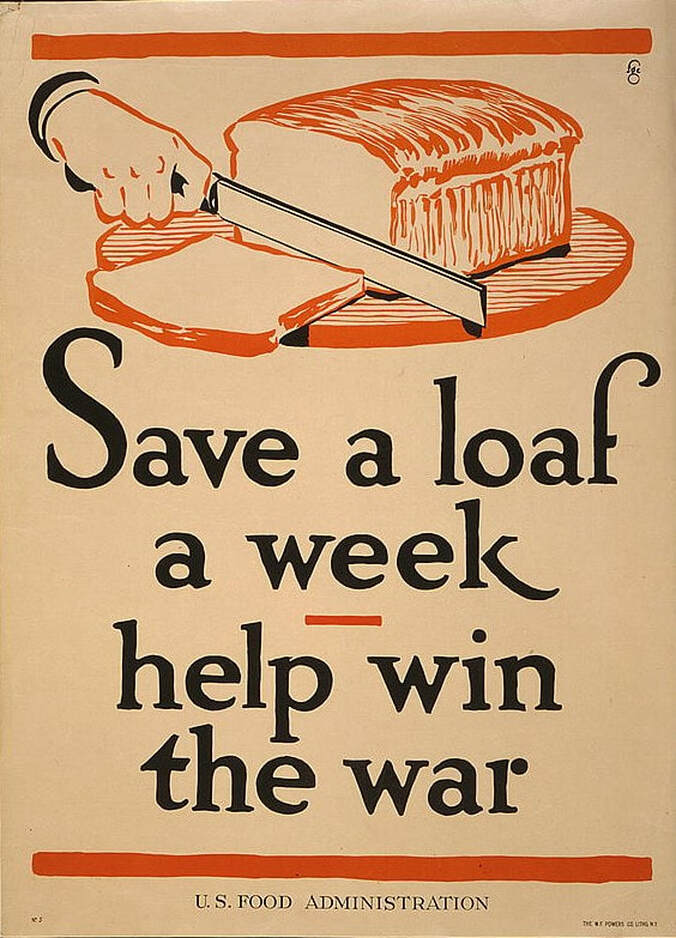

Like what you read, watch, or hear? Wanna help support The Food Historian, but don't want to commit to a monthly thing, or sign up for Patreon? Then you're in luck! You can leave a tip! This one-time (non-tax-deductible) donation helps keep The Food Historian going and pays for things like webhosting, Zoom, additions to the cookbook library, and helps compensate Sarah for her time and energy in helping everyone learn more about the history of food, agriculture, cooking, and more. Thank you! It's finally cold enough to bake in my neck of the woods. I made New York Gingerbread for a Halloween party this past weekend and it was delicious. You may be thinking of finally tackling the yeast bread you never made during the COVID shutdown. But like the early days of the pandemic when the shelves were empty of flour, during the First World War, wheat was in short supply. Poor wheat harvests in the fall of 1915 and 1916 meant that when the United States joined the war in April of 1917, there was not enough wheat to feed both the citizens of the United States and the military and their Allies. So the United States Food Administration embarked on a campaign to get Americans to voluntarily give up some of their favorite foods - including white bread made from wheat flour. By the 1910s white bread was ingrained (no pun intended) in the American diet and culture. It held onto its associations with wealth and refinement long after white flour became affordable and abundant. In addition, the conventional wisdom of nutrition science at the time elevated carbohydrates as a valuable source of energy. Which meant that both white bread and refined white sugar were considered healthful and important sources of the newly-discovered calories. Getting people to give up their favorite breakfast, side dish, and anytime (including midnight) snack was not going to be easy. This pair of propaganda posters produced by the USFA illustrate the same primary point - that if everyone gave up a little, the compound effect would be enormous. You'll note they don't focus on getting Americans to stop eating white bread - just to consume less. The implication of both posters is that be reducing consumption by as little as one slice a day would really add up. Other campaigns, including Wheatless Wednesday (partner to Meatless Monday), told Americans to replace the slice of bread customary with each meal with a baked potato, especially after the potato surplus in 1918. Alternative grains, especially corn, were also touted as substitutes for white bread. Restaurants were banned from bringing rolls or bread to the table before customers ordered their meal (sugar bowls were out, too). By 1918, one way the Food Administration tried to control the consumption of white bread without instituting mandatory rationing was to require Americans to purchase two pounds of alternative grains or flour for every one pound of wheat flour. However, although other campaigns emphasized corn as a valuable substitute, there's evidence that people may have just discarded the additional flours they were forced to purchase. Despite these challenges, the fact that the United States was able to feed their military, and the Allies, on the same 1916 wheat harvest suggests that Americans did reduce their wheat consumption in 1917. Today we know that refined white flour is a little too efficient a carbohydrate, and that the vitamins and minerals in whole grain flour, and the added fiber, are generally much better for human health. For wheatless recipes from the First World War, check out this article from North Carolina State University Libraries. The Food Historian blog is supported by patrons on Patreon! Patrons help keep blog posts like this one free and available to the public. Join us for awesome members-only content like free digitized cookbooks from my personal collection, e-newsletter, and even snail mail from time to time! Don't like Patreon? Join with an annual membership below, or just leave a tip!

Note: This article includes descriptions of wartime violence, genocide, and violence against women. Sensitive readers be warned.

Earlier this year, on Armenian Remembrance Day, President Biden officially declared the actions of Ottoman Turkey against Armenians during the First World War to be genocide. While some people might be aware of the Armenian genocide, I think fewer Americans are aware that it was part of the First World War.

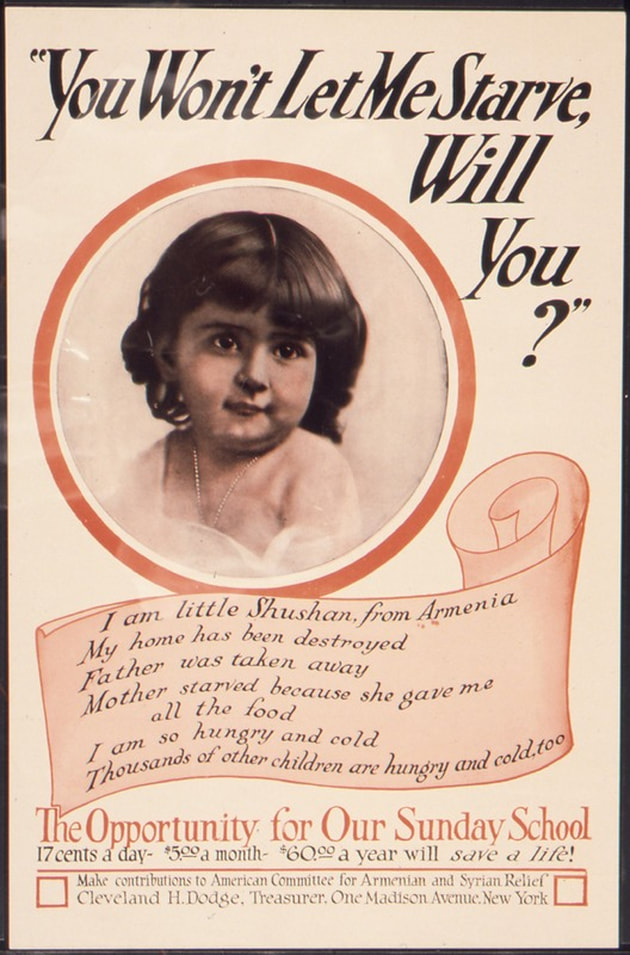

In the above poster, "You Won't Let Me Starve, Will You?" "Little Shushan" says, "My home has been destroyed. Father was taken away. Mother starved because she gave me all the food. I am so hungry and cold. Thousands of other children are hungry and cold, too." Directed specifically at Sunday Schools and children to raise funds for the American Committee for Armenian and Syrian relief, this poster is just one of the appeals made to Americans for charitable support for war-torn regions of Europe and the Middle East. Americans in 1915 were intensely aware of the actions of the Ottoman Empire as it was widely covered by newspapers. Like many campaigns that used starving children in Belgium to raise relief funds or exhort Americans to change their eating habits, Near East Relief and Armenian and Syrian Relief efforts were undertaken as charitable endeavors. The United States never declared war on the Ottoman Empire, perhaps at the behest of relief organizers. But without military intervention, the genocide continued as late as the 1920s. Armenians were Orthodox Christian in a predominantly Muslim Turkish empire. Russia, Turkey's enemy, was also predominantly Orthodox Christian at the time, meaning Armenians were largely branded a "fifth column" of seditious enemy spies living within the borders of the empire. This attitude was exacerbated by the Battle of Sarikamish, in which the Ottoman forces attempted to invade Russia between December, 1914 and January, 1915. Unprepared for the winter weather, the Ottoman military lost more than 60,000 men in a resounding military defeat. In retreat, the Ottomans indiscriminately burned, looted, and massacred Armenian villages near the border. The Ottoman military commander blamed the Armenians for the defeat, saying they had sided with the Russians. This set off a whole host of anti-Armenian violence, despite the fact that many Armenian men had enlisted in the Ottoman military. By the spring of 1915, the Ottoman Empire had launched a campaign of extermination against the Armenians. The lucky ones were able to escape. The not so lucky ones were systematically massacred or sent on forced death marches. The few Turkish politicians who protested were threatened with assassination. Any Muslim caught harboring an Armenian was threatened with execution. Many Armenian men who were massacred were rounded up and taken away from their villages to be killed. So many bodies were dumped in the Tigris and Euphrates Rivers that the corpses clogged the waterways and had to be disposed of with explosives. The pollution caused disease for communities living downstream, even after the war was over.

Although charitable organizations worked in the "Near East" throughout the war, and Americans did donate thousands of dollars toward food and relief work, the brutality continued. Coinciding with the massacres of men, Armenian women, children, and the elderly were sent on forced marches into the Syrian desert, punctuated by violence. Those few who survived to arrive at camps after marching without food or water, saw their children sold to childless Muslim families, and the women systematically raped. Those who survived to 1916 and 1917 were ultimately also massacred, so the Empire could avoid freeing them after the war. In all, more than 90% of the Armenian population in the Ottoman Empire was killed or deported, a number scholars estimate at between 1.5 and 2 million people.

The "Lest They Perish" poster above illustrates an Armenian (or possibly Syrian) woman with a child on her back standing in the midst of a bombed-out village. Despite the best efforts of the charitable organizations trying to help Armenians, most of them did, indeed, perish.

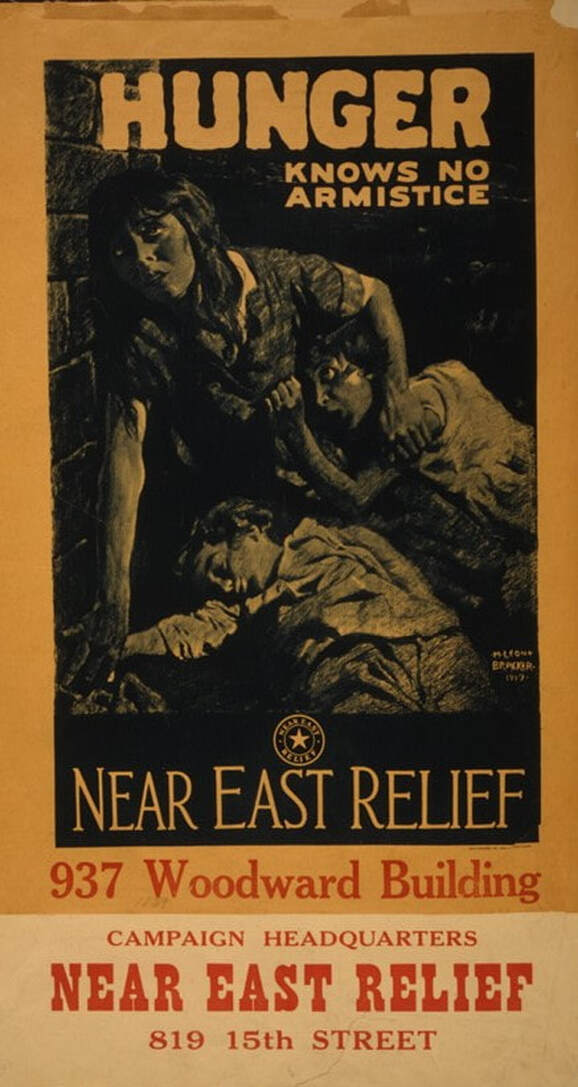

The use of hollow-cheeked women and children in war-torn regions was designed to pull on the heartstrings (and pockets) of Americans of all ages and backgrounds. Propaganda posters by charities like Near East Relief began in 1915 and continued until after the war, along with the genocide. Government-sponsored killings largely ended by 1917, but massacres continued on and off and widespread starvation threatened those who had managed to survive. This poster, "Hunger Knows No Armistice," succinctly points out that starvation was the post-war threat.

Near East Relief was founded in 1915 in Syracuse, NY as the American Committee on Armenian Atrocities, in reaction to reports from Henry Morgenthau, Sr., who was serving as American ambassador to the Ottoman Empire. Morgenthau was a German-born Jew appointed by Wilson to serve as ambassador in 1913 - a position he initially refused because of Wilson's idea that Jews were well-suited to serve as a bridge between Christians and Muslims. He ultimately accepted the position, and although his work at first consisted mostly of protecting Jewish residents and Christian missionaries, he was soon absorbed by the plight of Armenians in the Empire. Despite his frequent reports of genocide and violence against civilians, the United States remained officially neutral. Frustrated by the Turkish government's refusal to stop the killings, and by the American policy of non-interference, Morgenthau resigned in 1916. In 1918 he published Ambassador Morgenthau's Story, an accounting of his conversations with Ottoman officials about the genocide. However, during his tenure as Ambassador, he was the primary contact for the organization that would become Near East Relief, and was in charge of disbursing charitable donations in Turkey. After his 1916 resignation, it is not clear who disbursed funds, but fundraising continued. In 1919 the committee became only the second charitable organization in American history to receive a Congressional charter. The American Red Cross had been the first. And although charitable efforts continued, they could not stem the tide of genocide. The following video from Facing History & Ourselves, outlines the work of Morgenthau, the Committee on Near East Relief, and the American response (or lack thereof) to the Armenian genocide.

Near East Relief continued their work, focused largely on rescuing Armenian orphans and housing and educating them in a complex system of orphanages inside and outside of Turkey. In 1922, with the burning of Smyrna, Near East Relief evacuated 22,000 children into neighboring states. Evidence suggests that Greek and Armenian neighborhoods in Smyrna may have been purposely set alight by Turkish soldiers. The Muslim and Jewish quarters remained undamaged by the fire. Greek and Armenian residents of Smyrna were subjected to additional massacres, rape, and deportation, both before and after the fire.

In 1930, Near East Relief pivoted to become the Near East Foundation, working on education and economic development efforts in the Middle East and Africa. It still exists as a charitable organization today and the Near East Foundation has created a museum and archive about its organizational history and origins in the Armenian genocide. The U.S. Government never declared war on the Ottoman Empire. There was no military intervention. After the defeat of the Ottoman Empire, the Treaty of Sevres, and subsequent overthrow of Sultanate with the Turkish Revolution, there was an opportunity to create an Armenian state, which Woodrow Wilson had apparently been in favor of. However, his dreams of reorganizing the Middle East were dashed. The new Turkish government and Bolshevik Russia simultaneously invaded and partitioned the old Armenian Republic before Wilson's plan could be implemented. This led to the creation of both the Armenian Soviet Socialist Republic and the absorption by Turkey of portions of the former Armenian Republic, confirmed by the 1922 Treaty of Moscow between Soviet Russia and the new Turkish state. Despite ample first-person evidence of the horrific, systematic, and state-sponsored massacres, and the promise by the Allied Nations in 1915 that the Ottoman Empire would be held responsible for crimes against humanity, no one was ever prosecuted. In fact, the lack of consequences for the genocide may have inspired Adolf Hitler's death camps. He wrote, "I have issued the command -- and I'll have anybody who utters but one word of criticism executed by a firing squad -- that our war aim does not consist in reaching certain lines, but in the physical destruction of the enemy. Accordingly, I have placed my death-head formations in readiness -- for the present only in the East -- with orders to them to send to death mercilessly and without compassion, men, women, and children of Polish derivation and language. Only thus shall we gain the living space (Lebensraum) which we need. Who, after all, speaks today of the annihilation of the Armenians?" The rapid fall of the Ottoman Empire following the war likely played a major role in the lack of prosecution, as politicians were killed or dispersed and official evidence destroyed. In addition, it took until the Second World War to establish the United Nations and the criminal court at the Hague. Even so, international recognition of the genocide did not formally begin until the United Nations War Crimes Commission published a report in 1948 establishing what constituted war crimes. The Armenian genocide was cited as prime historical example of war crime and crimes against humanity. But it was not until 1985 that the term "genocide" was officially given to the massacres. Most nations did not officially recognize the Armenian genocide until the very late 20th or early 21st centuries. In fact, the United States, which had put so much effort into charitable work and so little effort into military intervention, only just recognized the genocide this year (2021). The Turkish government still refuses to admit to that the actions against the Armenian people during the First World War amounted to genocide. What is left of the Republic of Armenia became an independent state in 1991 with the fall of the Soviet Union. Today aligned politically and culturally with Europe, Armenians have transitioned fully to a capitalist economy. But their politics, like those of many nations, remain fraught in the modern era. In 2018 anti-government protests, named the 2018 Armenian Revolution, helped usher in political reforms. But other, older conflicts remain, including the Nagorno-Karabakh conflict between Armenia and Azerbaijan, which recently re-erupted in violence in the fall of 2020. A ceasefire was negotiated, and Armenians evacuated, but lasting peace remains elusive. To learn more about the Armenian genocide, visit the Armenian Genocide Museum of America.

The Food Historian blog is supported by patrons on Patreon! Patrons help keep blog posts like this one free and available to the public. Join us for awesome members-only content like free digitized cookbooks from my personal collection, e-newsletter, and even snail mail from time to time! Don't like Patreon? Join with an annual membership below, or just leave a tip!

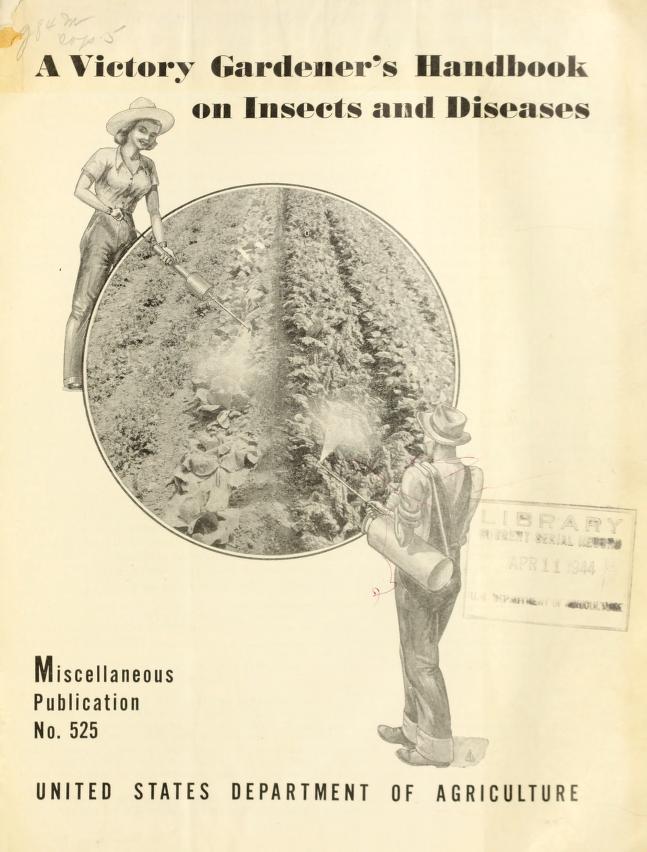

When it comes to modern ideas about Victory Gardens, there's a lot of romanticism and rose-colored glasses. Hearkening back to a kinder, gentler time when everyone pulled together toward a common goal and had delicious, organic vegetables in their backyards while they did it. But the reality was often much different from our modern perceptions. This propaganda poster is a good example of that. "Shoot to kill!" it says - "Protect Your Victory Garden!" In it, a woman wearing blue coveralls and a wide-brimmed hat, a trowel in her back pocket, sprays pesticide on a large, green insect (a grasshopper?) taking a bite out of an enormous and perfectly red tomato. She is protecting her victory garden from the "fifth column" of insect predation. "The Fifth Column" was a term used in the United States to describe sabotage and rumor-mongering by foreign spies. In this instance, insects become the "fifth column" because the act of eating crops threatens wartime food supplies, and is therefore sabotage by a foreign enemy. The food supply had to be protected and maximized at all costs. Anxieties around food supplies, especially in the winter when commercially produced foods might be scarce, meant that victory gardens took on special urgency. For the first time in at least a generation, Americans were having to put up their own food to help them get through the winter. And making every quart count was only possible if the garden did well. Lots of militarized language was used in propaganda concerning food, but none as war-like as the battle against pests in the victory garden. The idea that gardening before the 1950s was all organic is a common misconception. Even prior to the First World War, farmers and even some gardeners were dusting their crops with Paris Green and London Purple. Paris Green was a bright green toxic crystalline salt made of copper and arsenic. London Purple was calcium arsenate - normally white, but also a byproduct of the aniline dye industry, and was therefore sometimes tinged purple. Along with arsenate of lead, another salt, these three were termed arsenical pesticides and were used often in agriculture. The arsenic in rice scare from a few years ago was likely due to elevated levels of arsenical pesticide residue in the soil. Especially since rice from California, which first began to be commercial produced in 1912, but was not widely available across the country until the 1960s. That late adoption of rice agriculture meant that production was not as exposed to arsenical pesticides as elsewhere in the U.S. In 1944, the USDA published "A Victory Gardener's Handbook of Insects and Diseases" that identified common pests and suggested remedies. Calcium arsenate and Paris green were recommended (albeit with warnings about arsenic residue), along with:

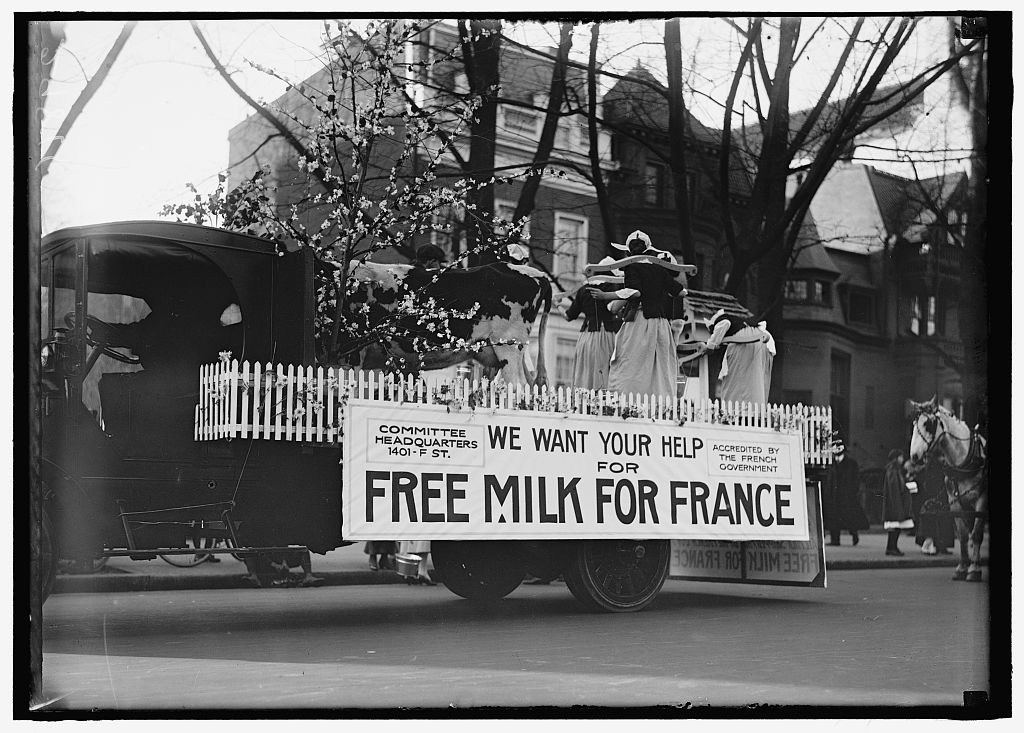

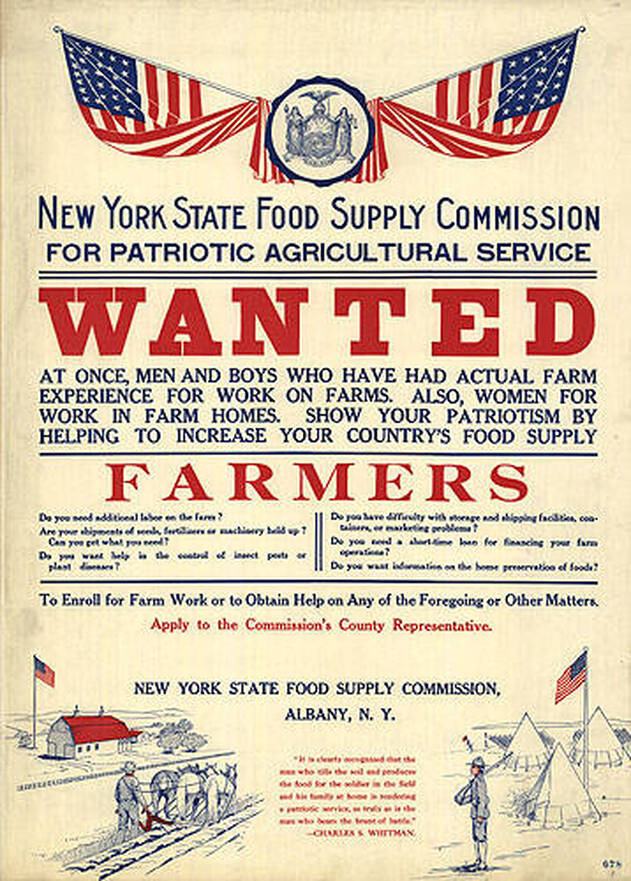

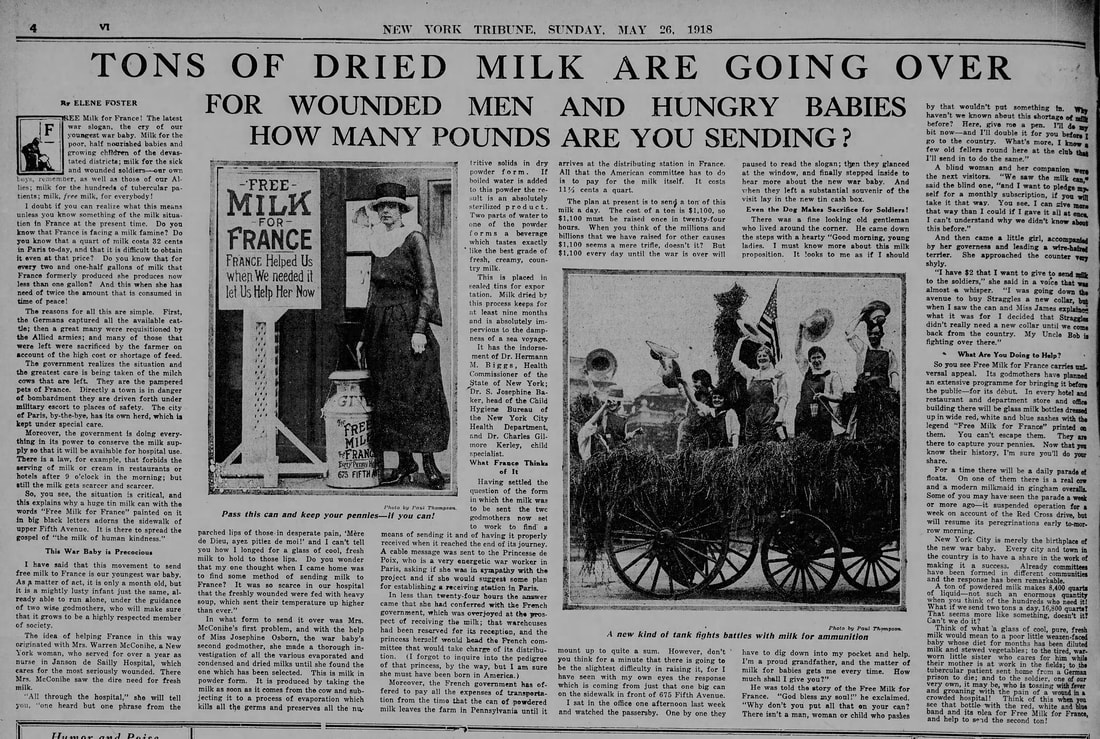

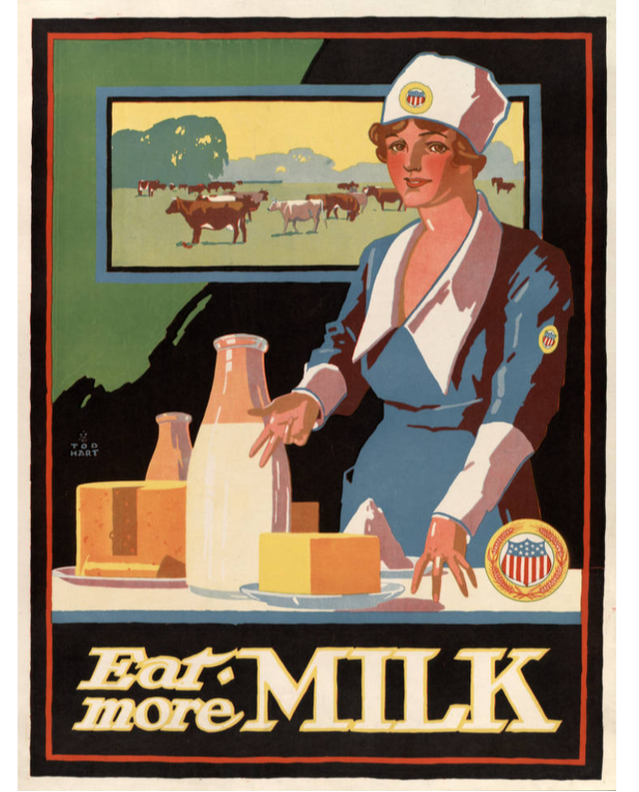

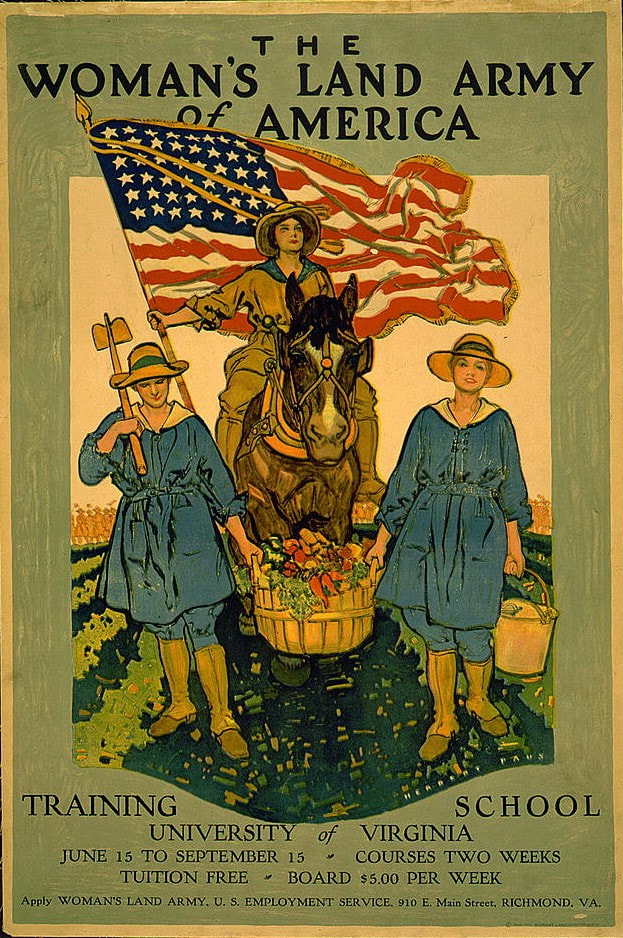

Although some people may have chosen not to purchase pesticides, likely due to expense more than concerns about poisoning, the emphasis on the danger pests posed to the general food supply continued. Hand atomizers, which is what the hand sprayer in the propaganda poster is called, were frequently depicted in print and even on film. Despite USDA warnings about application safety, no one is ever seen applying the highly toxic, aerosolized liquid pesticides with protective equipment. However, the science of the effects of exposure to toxic chemicals was not yet well-studied. DDT, invented in 1939, was deemed a miracle chemical and helped dramatically reduce diseases like malaria and water-borne bacteria that in previous wars had sometimes killed more soldiers than the conflict itself. Because soldiers faced no immediate effects, the chemical was deemed safe, and used everywhere from farms to a treatment for lice in children. But like the arsenical pesticides, the effect was cumulative, and it wasn't until Rachel Carson's 1962 Silent Spring that Americans began to wake up to the dangers of pesticides. The Food Historian blog is supported by patrons on Patreon! Patrons help keep blog posts like this one free and available to the public. Join us for awesome members-only content like free digitized cookbooks from my personal collection, e-newsletter, and even snail mail from time to time! Don't like Patreon? Join with an annual membership below, or just leave a tip! Join on Patreon or with an annual membership by June 30, 2020 and get a picnic history packet mailed to your door! Last week we learned about the big Dairy Exposition during WWI - this week we're examining the Free Milk for France movement, which coalesced about the same time. This propaganda poster by F. Louis Mora from 1918 is one of the more famous of the food-themed propaganda posters of the First World War. In it, a soldier ladles milk out of a large milk can into the bowl of a French child, one of several, accompanied by a wounded French soldier with a tin cup and crutch. Judging by how bundled up everyone is, it's probably winter. Ironically, the Free Milk for France campaign actually focused on provided dried milk. On May 13, 1918, the Committee to Obtain Free Milk for France launched a fundraising parade. "The parade, consisting of two floats and an escort of soldiers and sailors, including a navy band, started from the First Field Hospital Armory at Sixty-sixth Street and Broadway and canvassed the city as far down as the Wall Street District," reported the New York Times the following day. "The money will be used to purchase powdered milk to be sent to France for the use of wounded soldiers, babies, and tubercular patients." In the above photo, a woman dressed in overalls and a straw hat drives a team of horses pulling a large hay wagon. Another woman riding on the wagon is dressed in a military-style outfit holding a small bucket and a wooden shoe - likely soliciting donations. An American flag attached to a sheaf of hay is behind them. The first parade made over $1,000. The group launched another parade a few days later, on May 17th, parading "down Fifth Avenue from Fifty-ninth Street to Twenty-second Street yesterday afternoon." Featuring seven floats, including young society girls "dressed as milkmaids."  Free Milk for France parade, motor truck with a float of milkmaids with a live cow and flowering tree, surrounded by a white picket fence. A large sign reads, "We want your help for Free Milk for France," with smaller notes - "Committee Headquarters 1401-F St." and "Accredited by the French government." Harris & Ewing photographers, May, 1918. Library of Congress. In the above black and white photo, a flat bed truck features a large float carrying a flowering tree, a live dairy cow, and at least five young women dressed as Brittany milkmaids. The edges of the float are surrounded by a white picket fence. On May 19, 1918, the New York Times published "America Sending Milk to France." The article is transcribed below: One of the greatest sources of suffering in France has been lack of milk. The causes for this lack are manifold. In many instances the Germans slaughtered cows for beef whose greater value lay in their milk; in other instances the Government of France requisitioned the animals for army use, and in still others the farmers found themselves forced to kill their cattle on account of the shortage of pasture and fodder. All in all there have been lose to the people of France about 2,000,000 cows, and the main source of maintenance of infants and children, of the crippled and the wounded, the sick and tubercular, lies in milk. At present the death rate of children in France is from 58 to 98 per cent. The number of wounded and crippled needs no repetition here. The increase in the ranks of the tubercular is appalling. Outside Belgium, perhaps, there is no other country which has so greatly succumbed to this disease. The supply of milk in France has been depleted at least 16 per cent. Under present conditions infants must take vegetable stews as a food substitute. What this means to their health and their growth the mortality figures show. Wounded soldiers get heavy soups, which are well-nigh fatal in their effects. The tubercular of France have almost been forgotten. Milk has become a luxury far beyond the reach of the majority of them. In order to do something to meet this situation and to conserve the milk they have, the French Government is taking vigorous measures. Great care is devoted to the protection of milch cows. From bombarded towns, under military escort, two or three at a time are led back to places of safety. Farmers are urged to make all sacrifices possible to provide proper feed for them. Within Paris a herd of cows is kept under civic care. Government restriction now forbids the serving of milk or cream for any purpose in restaurants, hotels, or public eating places after 9 o'clock in the morning. In private homes, rich or poor, milk is only given to young children and the sick. Milk in Paris costs 32 cents a quart, when it can be bought. It was in a desire to do something to change these conditions that Mrs. Warren McConihe and Miss Josephine Osborne organized the Free Milk for France Fund. Mrs. McConihe had seen the soldiers suffering greatly for want of milk, she had seen them grow feverish under the influence of heavier foods. She had seen the Belgian and French refugees almost starved for lack of milk. Upon her return to this country she found that America had enough milk to send some across. Because it requires less shipping space, she chose powdered milk. It is scientifically prepared by subjecting fresh, pure, full-creamed milk to a rapid evaporating process, which preserves the nutritive solids and keeps without ice for months. The milk when prepared costs about 13 cents a quart. There is no other cost. The Government of France has taken over the details of transportation. It is the aim of the organization to send one ton of milk a day. All that is necessary is to mix with hot water. The milk in this form has been recommended even for home use by Dr. Hermann M. Biggs, State Health Commissioner; Dr. S. Josephine Baker of the Child Hygiene Bureau, and Dr. Charles G. Kerley, a child specialist. At a cost of $1,100 a ton of dried milk is sent across, enough to feed 8,400 babies or wounded soldiers or tubercular patients. $52 will send 100 pounds of dry milk or 40 quarts of liquid; $5.20 will sent ten pounds, or forty quarts, and 13 cents will send one quart. The aim of the Free Milk for France organization is to have the nation as a whole respond to its work. Branches are being organized all over the country. The headquarters of the fund is at 675 Fifth Avenue. These two parades, held during the National Milk and Dairy Farm Exposition, were just the first of a campaign that would last into 1919 and spread across the country. By the end of 1919, there were campaigns in thirty-six states, and the distribution in France was being organized by Madame Foch - wife of French General Ferdinand Foch. The rhetoric around milk and its importance in the diet, especially for children and the sick, would be replicated in the Second World War. The Food Historian blog is supported by patrons on Patreon! Patrons help keep blog posts like this one free and available to the public. Join us for awesome members-only content like free digitized cookbooks from my personal collection, e-newsletter, and even snail mail from time to time! Don't like Patreon? Join with an annual membership below, or just leave a tip! Join on Patreon or with an annual membership by June 30, 2020 and get a picnic history packet mailed to your door! This beautiful propaganda poster from the First World War is the result of a controversy. The fresh-faced young white woman in her United States Food Administration-approved food conservation uniform and cap, gestures to a table with an enormous glass bottle of milk, a huge block of butter, a wheel of cheese, and what is either a mound of cottage cheese or some sort of milk pudding. A framed view of dairy cows in a green field floats behind her. It exhorts the reader to "Eat more MILK." But why? Throughout World War I in the United States, dairy farmers struggled. Feed prices went up, and retail prices of milk went up, but the wholesale prices that farmers got from milk dealers and dairies remained static. Despite dozens of local and state and federal inquiries, no single culprit for high milk prices was ever discovered. The result of high prices combined with government advocating for increased production and Progressive Era ideas about the importance of cow's milk in the diet, particularly for children, meant that by the spring of 1918 there was a serious milk surplus. For several years, the butter, cheese, and condensed milk industries had absorbed the milk surplus, but by the spring of 1918 they were also over capacity. The United States Food Administration, in conjunction with state governments, embarked on a campaign to try to get Americans to consume more milk, with limited success. In May of 1918, New York City hosted the National Milk and Dairy Farm Exposition at the Grand Central Palace. New York State Governor Charles Whitman opened the exposition, and United States Food Administrator Herbert Hoover also attended. Home economists praised milk-based dishes such as puddings, custards, and the use of cottage cheese and brick cheeses - hence the phrase "Eat more milk," rather than "drink," as drinking cows milk was not common among adults. Cottage cheese and brick cheese were touted as affordable meat alternatives. Despite the classic Progressive Era boosterism, including the attendance of "famous" cows at the exposition, retail milk prices remained relatively high, with seasonal dips in the spring and early summer. Federally fixed milk prices helped solve the problem short-term, but even after the war, dairy farmers were subject to a Congressional investigation to determine whether they price gouged consumers (they didn't), and the right of farmers to form co-ops was in danger of becoming illegal under anti-trust laws. Ultimately, it was falling grain prices and rising postwar demand that evened out prices, although to this day the dairy industry still struggles. Even after the war, Progressive Era ideas about the importance of cow's milk in the diet persisted, and were recycled during the Second World War. The Food Historian blog is supported by patrons on Patreon! Patrons help keep blog posts like this one free and available to the public. Join us for awesome members-only content like free digitized cookbooks from my personal collection, e-newsletter, and even snail mail from time to time! Join by June 30, 2020 and get a picnic history packet mailed to your door! This post contains affiliate links. If you purchase something from a link, you'll be supporting The Food Historian! The Woman's Land Army of America came out of the women's suffrage movement as a way for young, largely college-educated women to prove their worth during wartime by providing agricultural labor to make up labor shortages thanks to the draft, better wages in industrial work, and the need to increase agricultural production. The movement started in New York State, and has been ably chronicled by Elaine Weiss' book The Fruits of Victory. This beautiful propaganda poster from the University of Virginia Training School for the Woman's Land Army of America is just delightful. The imagery is evocative. A young woman holding an American flag, which billows out behind her, is dressed in a khaki uniform and riding a plow horse through a green agricultural field, simultaneously calling to mind a mounted standard bearer, Teddy Roosevelt's Rough Riders, and Army cavalry. In the foreground, two young women in matching blue uniforms share the load of a bushel basket laden with vegetables. The woman at left has a hoe over her shoulder, reminiscent of how a soldier might carry a rifle. The woman at right carries what appears to be a milk pail. Far in the background, what appears at first glance to be a field of ripe wheat is in fact a golden line of uniformed women with agricultural implements on their shoulders, marching behind the leading three. The costumes were among the official Woman's Land Army costume - in khaki and blue chambray. A loose tunic with full sleeves (rolled up) and a cinched waist falls to the knee, covering military-style jodhpurs and puttees over sensible shoes. A broad-brimmed hat and a kerchief around the neck complete the sensible outfit, which somehow still scandalized some members of the public at a time when women's skirts rarely rose above the ankle. The poster is advertising the Woman's Land Army's Training School at the University of Virginia. Designed to give young women basic agricultural skills, and sometimes specialized skills like the use of tractors, the schools were generally free, but required payment for room and board, as this one does at $5.00 per week for a two week course. Sometimes called "farmerettes," likely a combination of the terms "farmer" and "suffragette," and one which not every member of the Woman's Land Army enjoyed. But then, not every farmerette was a member of the Woman's Land Army, and the term actually predated the U.S. entrance into the war. The women saw some success in the adoption of their labor in agriculture, but it created no sea change of labor distribution post-war. Most farmers outside orchards and truck farmers mechanized in the face of labor shortages, rather than using farmerettes or farm cadets (teenaged boys released from school to work on farms). And increasing specialization of crops and livestock meant that mechanization was easier and more profitable than hiring young women at good wages for just 8 hour days (pre-war farm laborers had no such protections). The Land Army would be revived during World War II, this time divorced from its suffragist origins and encouraging young people of both sexes to assist with farm labor. But that's a post for another day. Woman's Land Army Books Fruits of Victory: The Woman's Land Army of America in the Great War by Elaine F. Weiss Weiss tracks the evolution of the Woman's Land Army in America, focused primarily on New York State, which was where the WLA officially began in the U.S. In intimate detail, she introduces us to a whole host of historic characters, including leading lights of the women's suffrage movement, and how they tried to prove women's agricultural labor was the future.  Cultivating Victory: The Women's Land Army and the Victory Garden Movement by Cecilia Gowdy-Wygant Cultivating Victory examines the interrelationships between the British and American Woman's Land Armies, as well as their connections to the war garden and victory garden movements. Covering both the First and Second World Wars, Gowdy-Wygant compares and contrasts the efforts in both nations and the differences and similarities between both wars. The Food Historian blog is supported by patrons on Patreon! Patrons help keep blog posts like this one free and available to the public. Join us for awesome members-only content like free digitized cookbooks from my personal collection, e-newsletter, and even snail mail from time to time! Join by June 30, 2020 and get a picnic history packet mailed to your door!  "New York State Food Supply Commission for Patriotic Agricultural Service. Wanted at once, men and boys who have had actual farm experience for work on farms. Also, women for work in farm homes. Show your patriotism by helping increase your country's food supply. Farmers - Do you need additional labor on the farm? Are your shipments of seeds, fertilizers or machinery held up? Can you get what you need? Do you want help in the control of insect pests or plant diseases? Do you have difficulty with storage and shipping facilities, containers, or marketing problems? Do you need a short-term loan for financing your farm operations? Do you want information on the home preservation of foods? To Enroll for Farm Work or to Obtain Help on Any of the Foregoing or Other Matters. Apply to the Commission's County Representative. New York State Food Supply Commission, Albany, N.Y." 1917, Temple University. The United States entered the First World War on April 6, 1917. On April 13, New York State Governor Charles S. Whitman appointed a Patriotic Agricultural Service Committee. On April 17, an Act of the New York State legislature created the New York State Food Supply Commission. This propaganda poster is likely from the spring of 1917 for several reasons. First, by the fall of 1917, the commission had changed its name to the New York State Food Commission, Second, the emphasis on laborers with farming experience, rather than the inexperienced, was a hallmark of early efforts to increase agricultural production. The poster reads: "New York State Food Supply Commission for Patriotic Agricultural Service. Wanted at once, men and boys who have had actual farm experience for work on farms. Also, women for work in farm homes. Show your patriotism by helping increase your country's food supply. Farmers - Do you need additional labor on the farm? Are your shipments of seeds, fertilizers or machinery held up? Can you get what you need? Do you want help in the control of insect pests or plant diseases? Do you have difficulty with storage and shipping facilities, containers, or marketing problems? Do you need a short-term loan for financing your farm operations? Do you want information on the home preservation of foods? To Enroll for Farm Work or to Obtain Help on Any of the Foregoing or Other Matters. Apply to the Commission's County Representative. New York State Food Supply Commission, Albany, N.Y." Interestingly, this poster not only focuses on farm labor, seed acquisition, farm loans, etc., but also on securing women's labor "for work in farm homes." The general idea was that women could help relieve some of the household burden on farm wives, and assist with food preservation, so that farm wives, who were often more experienced in farm management than most farm laborers, could assist their husbands. Neither plan really worked out well. The few women who were interested in farm labor wanted to do the agricultural work - not housework. And while experienced farm hands were in high demand, that drove wages up considerably - not every farmer was able to afford them. The Food Supply Commission coped by helping some farms modernize. They purchased a series of tractors - then still a rarity in the Northeast - and helped farmers acquire seed potatoes, beans, and more. But it took until the end of 1917 for the Commission to find its footing. By then, it became a partner of the United States Food Administration, working hand-in-hand with Hoover. You can read more about the New York State Food Supply Commission and its early work in its annual report for 1917, published in 1918. The Food Historian blog is supported by patrons on Patreon! Patrons help keep blog posts like this one free and available to the public. Join us for awesome members-only content like free digitized cookbooks from my personal collection, e-newsletter, and even snail mail from time to time! |

AuthorSarah Wassberg Johnson has an MA in Public History from the University at Albany and studies early 20th century food history. Archives

July 2024

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed