|

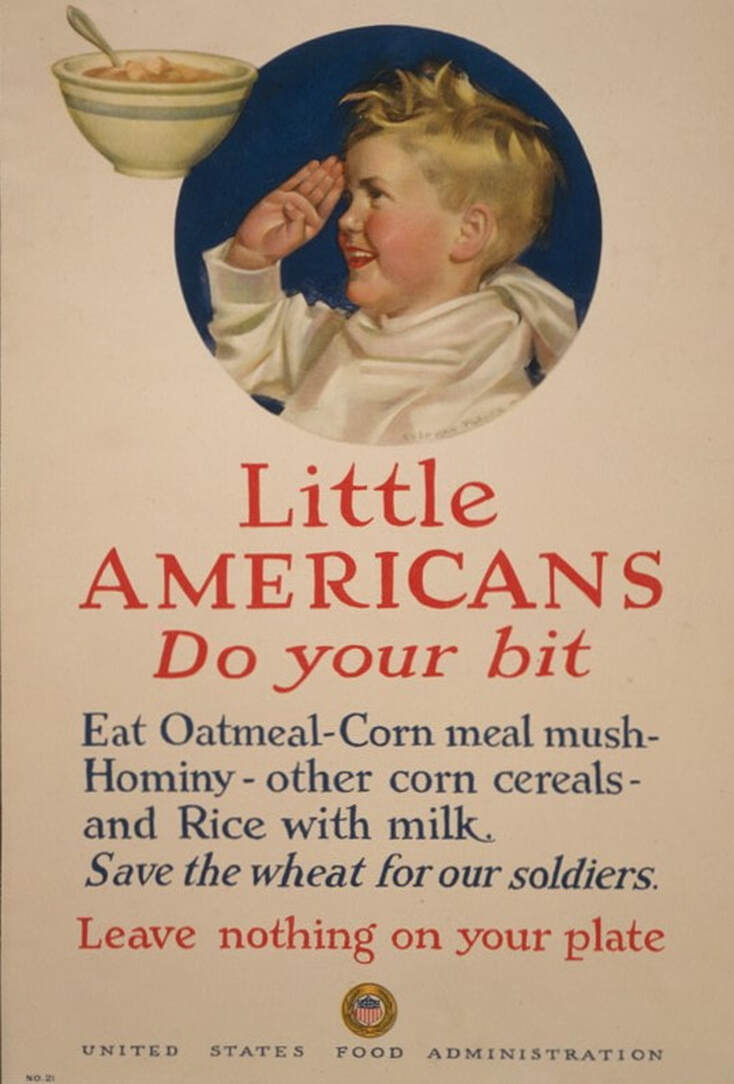

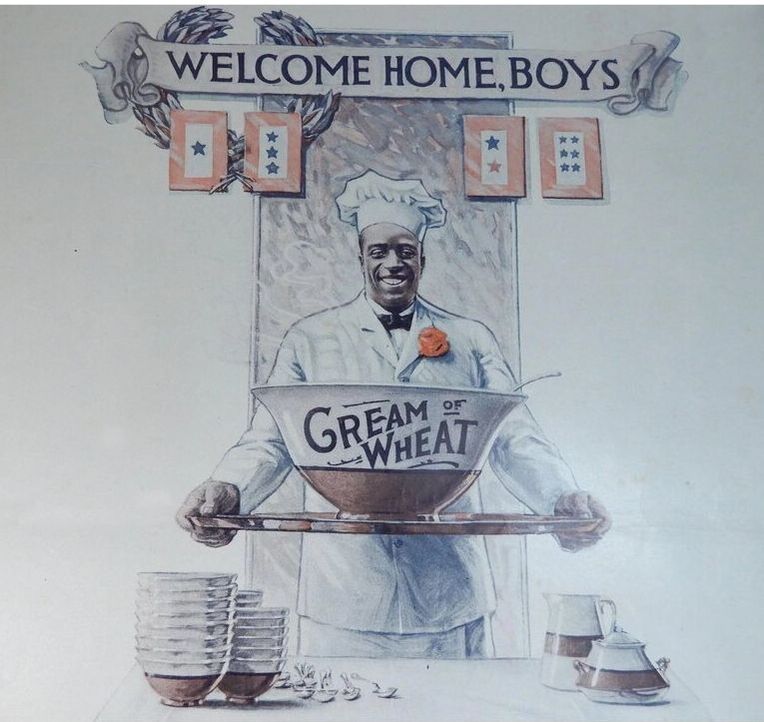

I was interviewed recently about breakfast cereals, especially corn flakes and the Kellogg brothers, so I thought for this week's World War Wednesday we'd take a look at this sweet propaganda poster from the First World War. "Little Americans - Do Your Bit! Eat Oatmeal - Corn meal mush - Hominy - other corn cereals - and Rice with milk. Save the wheat for our soldiers. Leave nothing on your plate" was designed by commercial artist Cushman Parker, who also designed covers featuring cherubic children for the Saturday Evening Post. This poster is interesting because the message is targeted specifically at children. Aside from the school garden movement, there weren't many food-related wartime posters directed to kids - this is one of the only ones. In this poster, a rosy-cheeked blond young man - who looks to be about five or six years old, salutes a floating bowl of hot cereal, a large white napkin tied around his neck as a bib. Although cold breakfast cereals were around at the time of the First World War, they were still considered less nourishing than hot cereals, especially for children. Oatmeal, Cream of Wheat (a.k.a. farina or semolina), and cornmeal or hominy mush were still popular at the breakfast table. Wheat was in short supply during the First World War, so ordinary Americans were encouraged to voluntarily restrict use to free up supplies for American soldiers and the Allies. That meant no more farina! As was true of much of the wartime propaganda, this poster calls for Americans to support the soldiers, doing without so "the boys over there" could have enough. Although Americans only entered the war in the spring of 1917, and it was over by the fall of 1918, wheat supplies continued to tighten throughout the war. By shifting eating habits to focus on other hot cereals, especially oatmeal and corn products like grits, Americans could help "do their bit" for the war effort. Rationing was voluntary for Americans, but Meatless Mondays and Wheatless Wednesdays still came to dominate American daily life. And children were no exception! Although advertising usually targeted the person who did the food shopping (usually the mother), this poster stands out as one targeting children directly, likely to help educate them about the needs of American troops and cut down on potential complaining, which might encourage parents to give into whining and purchase wheat products. The return of wheat, sugar, meat, and fats like butter and lard were a welcome herald to the end of the war. In this 1919 magazine advertisement, Rastus, the racist depiction of an African American cook used by Cream of Wheat packaging and advertisements for over 100 years before finally being removed in the fall of 2020, welcomes home American troops with an enormous bowl of Cream of Wheat - a sign of the end of rationing and likely an attempt to return Cream of Wheat to the tables of Americans who might have gotten used to eating other alternatives. The Food Historian blog is supported by patrons on Patreon! Patrons help keep blog posts like this one free and available to the public. Join us for awesome members-only content like free digitized cookbooks from my personal collection, e-newsletter, and even snail mail from time to time! Don't like Patreon? Leave a tip!

2 Comments

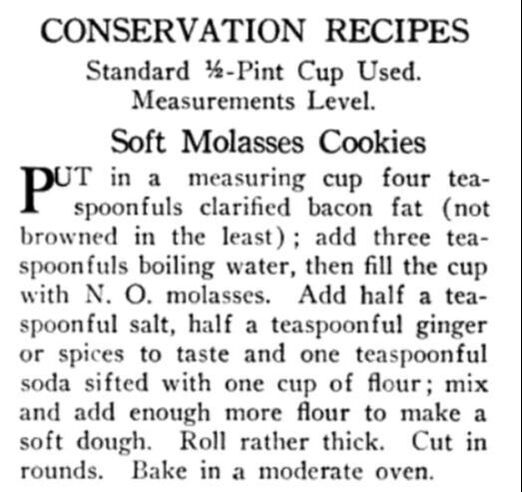

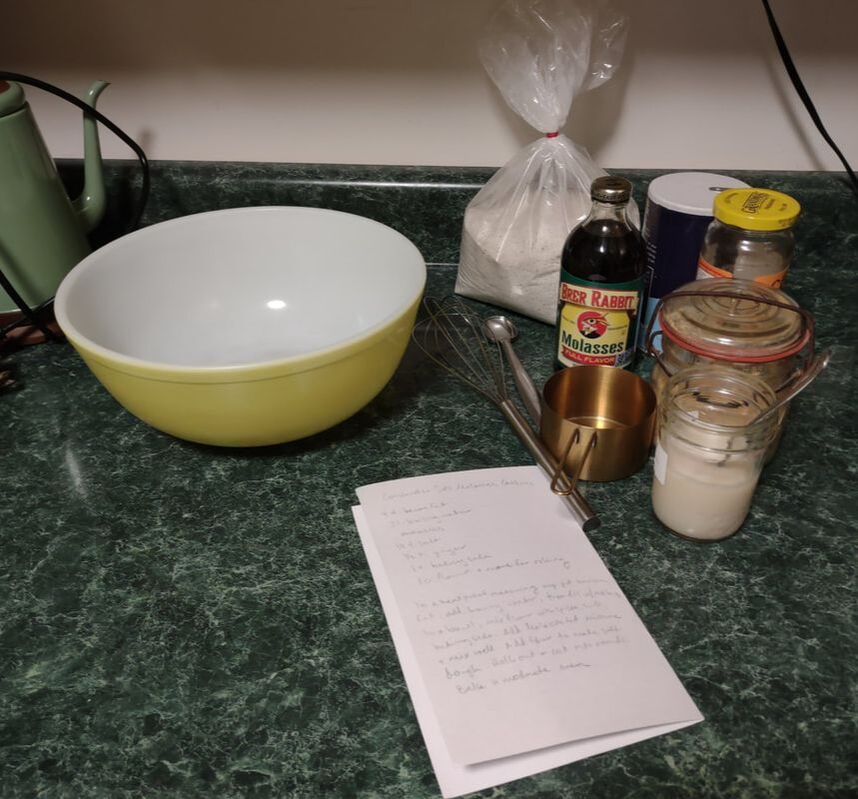

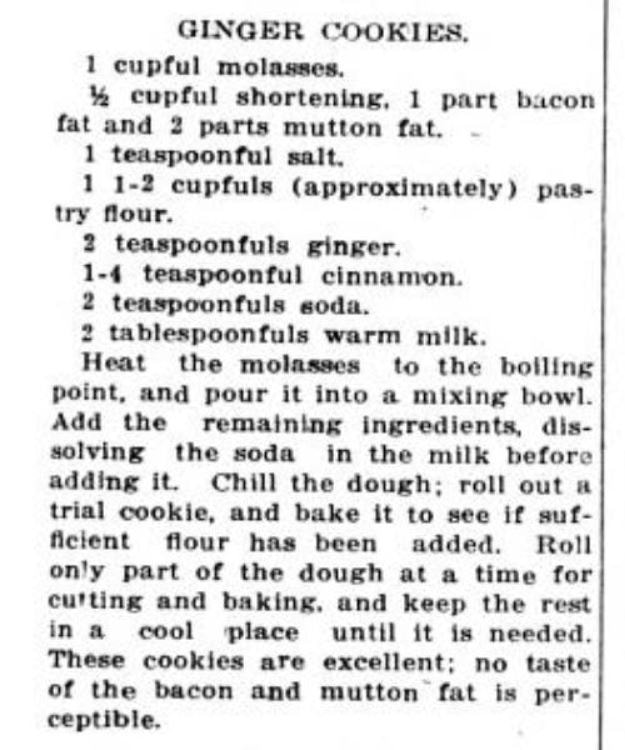

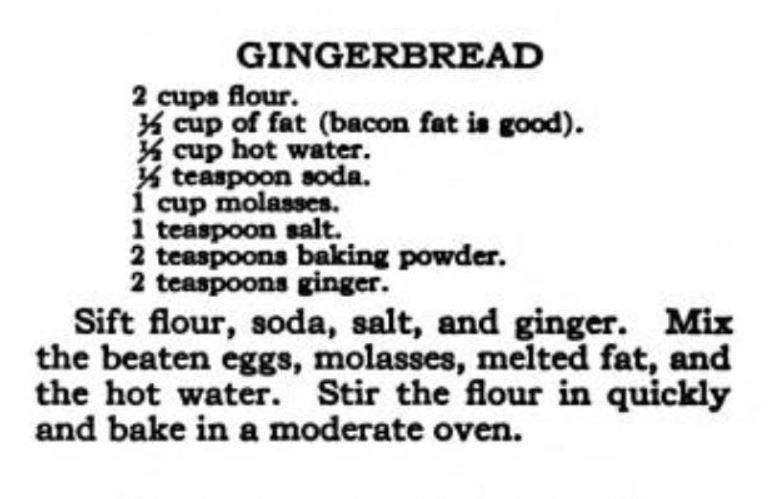

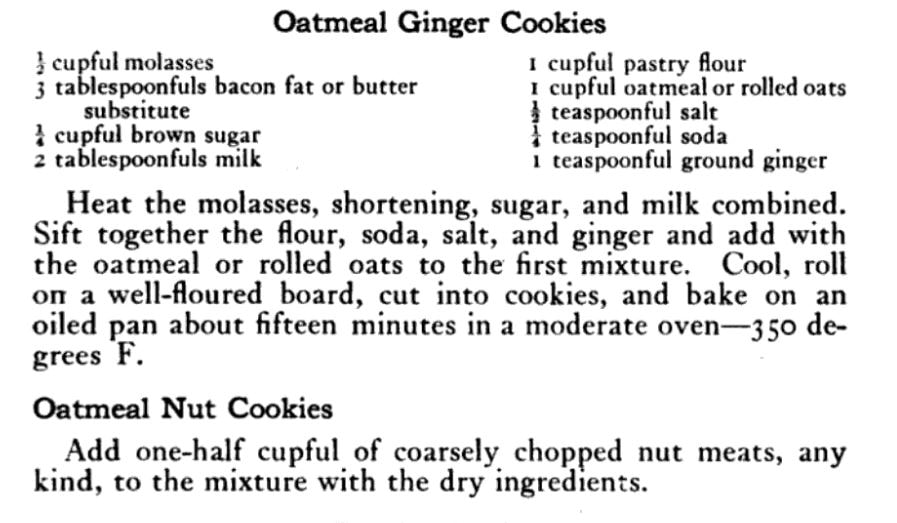

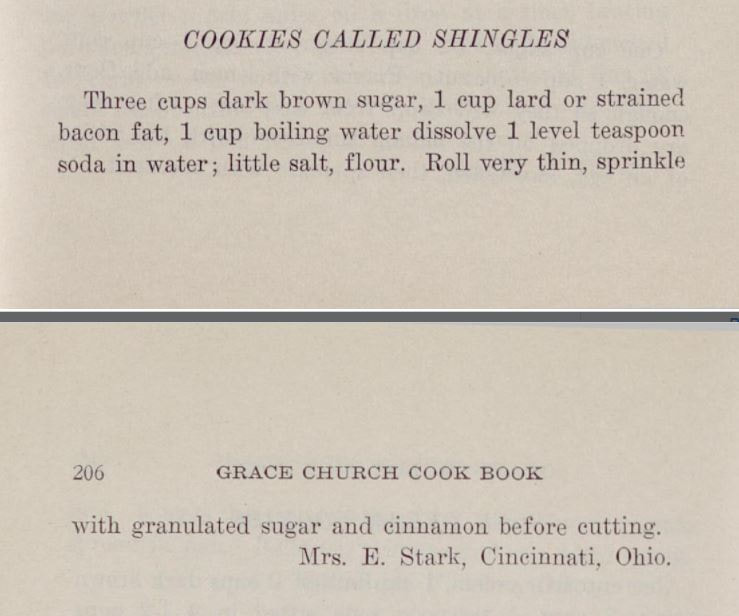

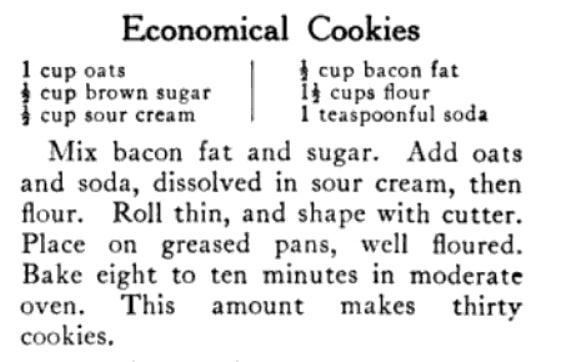

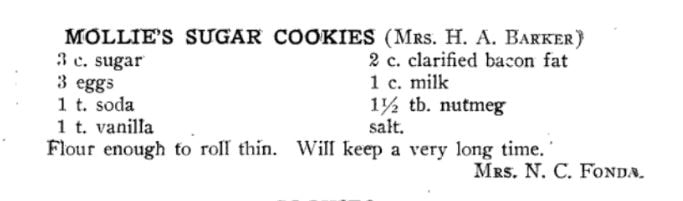

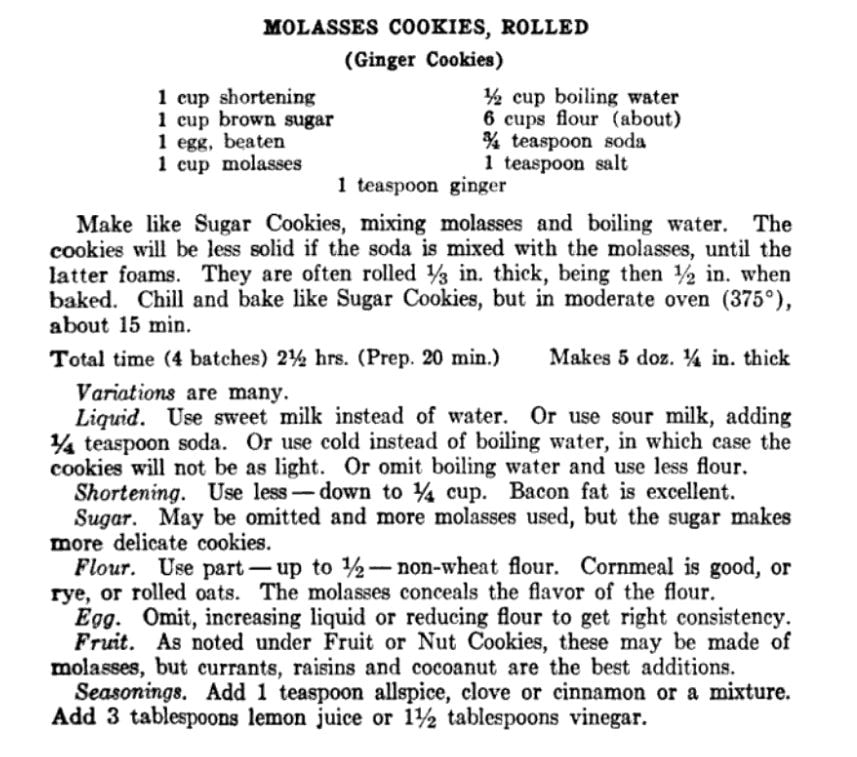

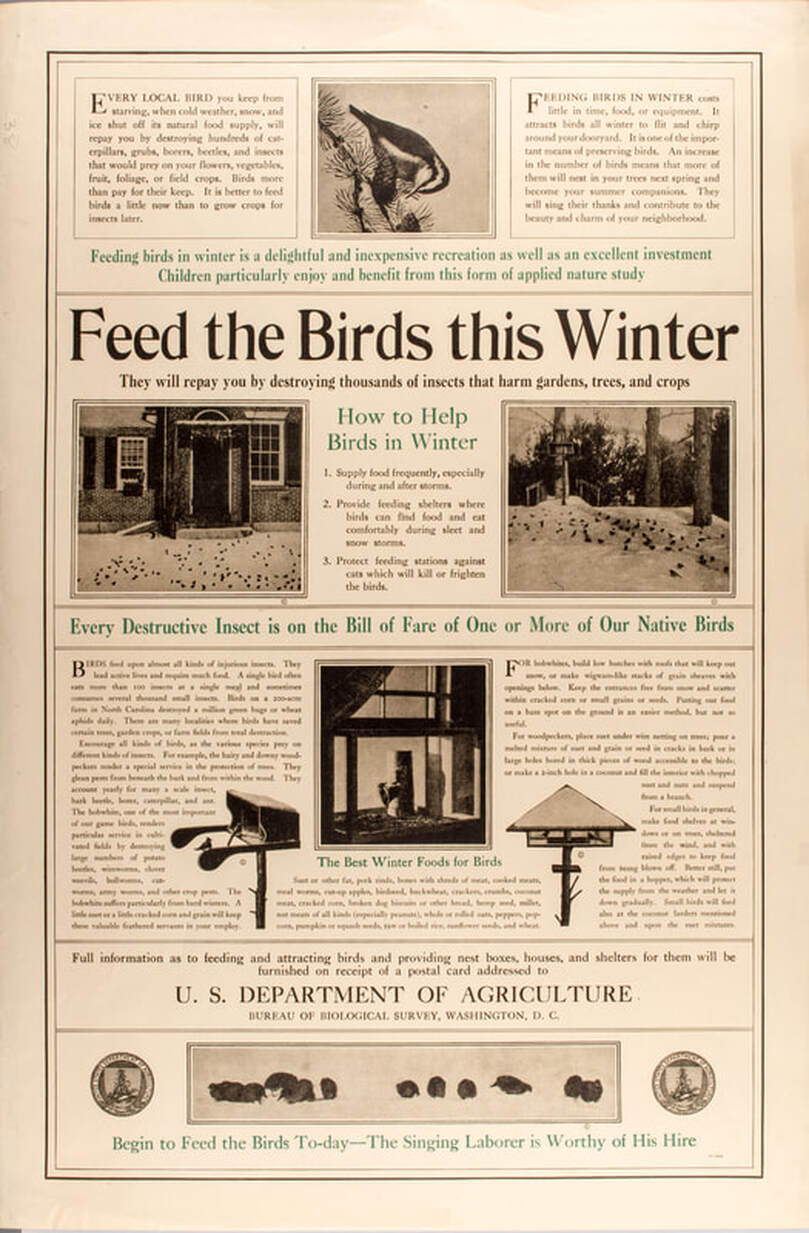

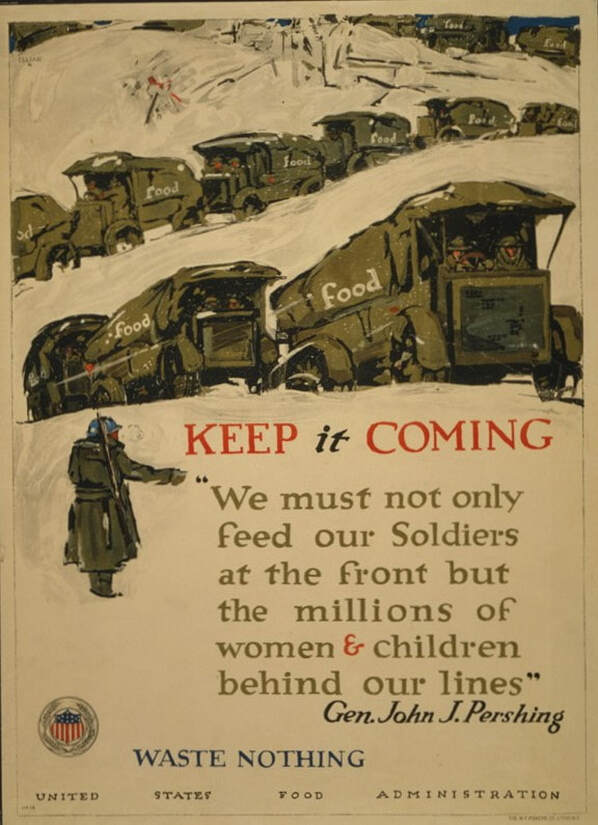

I first ran across bacon fat gingersnaps in the Christmas cookie collection the New York Times posted for December, 2021. Although I'm not a NYT Cooking subscriber, I did a google and found an article about the original recipe, which indicated the recipe was likely historic. Even though I'd just finished my Christmas cookies research, the bug bit again and the hunt was on. I found several historic recipes for bacon fat cookies, some of them gingery, some of them not (scroll to the bottom for the gallery of recipes), but because I am a World War I historian, I decided that the recipe I was most interested in at the moment was the "Soft Molasses Cookies" listed as a "Conservation Recipe" in the February, 1918 issue of American Cookery, formerly the Boston Cooking School Magazine. And it seemed appropriate to be baking them in February, 2022! The recipe is not written in a way we're used to today, but is fairly straightforward. It reads: Put in a measuring cup four teaspoons clarified bacon fat (not browned in the least); add three teapsoonfuls boiling water, then fill the cup with N.O. [New Orleans] molasses. Add half a teaspoonful salt, half a teaspoonful ginger or spices to taste and one teaspoonful [baking] soda sifted with one cup of flour; mix and add enough more flour to make a soft dough. Roll rather thick. Cut in rounds. Bake in a moderate oven. This recipe is sugarless, eggless, and butter-less, and it uses fats that might otherwise go to waste, making it the perfect conservation recipe during a time when Americans were asked to save wheat, sugar, meat, and fats for the war effort. The use of New Orleans molasses was specifically to save space on cargo ships and support American sugar production (molasses is a byproduct of sugar cane processing). By using bacon fat, normally a waste fat, Americans could save on lard and butter. Bacon Fat Soft Molasses Cookies (1918)I will admit that I started this recipe before I realized I was virtually out of all-purpose flour. And since I had a good deal of whole rye flour to use up, and I thought it in keeping with the spirit of the recipe to make this wheatless as well, I used all rye (although in the period rye was not considered an official substitute for wheat, largely because it was in fairly short supply). It did make a rather heartier cookie than I think was intended, but it worked just fine. Here's my translation of the original: 2+ cups flour (I used whole rye) 1 teaspoon baking soda 1/2 teaspoon salt 1/2 teaspoon ground ginger 4 teaspoons bacon fat 3 teaspoons boiling water a little less than 1 cup molasses Preheat the oven to 350 F. In a large mixing bowl, whisk together 1 cup flour, the baking soda, salt, and ground ginger. In a heat-proof measuring cup, place the bacon fat and add the boiling water. Then add molasses enough to make 1 cup. Pour into the flour mixture and beat well. Add more flour (about another cup) until a soft dough forms. You may need more flour as the dough will be very sticky. Knead in a little more flour as needed to make a dough that can be rolled without excessive stickiness. Flour your rolling surface well, and roll out the dough about a half inch thick, or a little thicker. Cut into rounds and bake on a parchment-lined baking sheet (to prevent sticking and save on grease!) at 350 F for 10-12 minutes. My batch rolled relatively thin made just short of 2 dozen largish cookies. Next time I would probably let them be a little thicker and I'd probably end up with a dozen and a half. Although these aren't crisp or particularly sweet, they do taste astonishingly close to the Archway brand of molasses cookies you can find very inexpensively in just about every grocery store. Soft, and a little cakey, with strong molasses flavor and just a hint of gingery spice. I couldn't really taste the bacon fat while they were still warm (though my husband claims he could), but the flavor will likely improve the next day. I did frost a few to dessert-them up a little. Just a few teaspoons of heavy cream mixed with some powdered/icing sugar. Shhh! Don't tell Herbert Hoover! Although these are quite soft right out of the oven, they will harden up as they cool, so be sure to store them in an air-tight container to help retain moisture. All things considered, I think this recipe turned out rather well for one that was supposed to be a bit of a privation during the war. Although I don't think it was UN-common to use bacon fat or drippings or any other animal fats as shortening in baking in the 19th century (indeed in the 1800s "shortening" just meant any kind of solid fat - remember we don't get vegetable shortening until the 1870s), we don't really see bacon fat specifically called out in cookbooks until the 1910s. One reason is likely that bacon was an increasingly popular breakfast food. Oscar Mayer, in particular, started selling pre-packaged sliced bacon in 1924. Breakfast was rebranded in the 1920s away from stodgy porridges and even health-food cold cereals and toward bacon, eggs, and tableside electric appliances that made things like waffles, fresh-squeezed orange juice, coffee, and toast. All that bacon frying meant that cooks had a surfeit of grease, and frugal cooks would hate to waste it. And while bacon fat is perfect for frying potatoes into hash, there's only so many things you can fry in bacon fat. Hence, the baking recipes. As you can see from the collection below, they're all for 1915 and later, with most in the 1920s. Bacon fat was saved in WWII as well, but housewives were just as likely to save the fat for munitions than bake with it. Once animal fats were connected to heart disease in the 1950s, bacon took a back seat in the United States until its revival in the 2000s (largely coinciding with the popularity of the Atkins Diet). We don't make bacon all that often. Usually it's with a big breakfast or brunch I make on the weekends. But I've made a point lately to save the fat. If you bake your bacon in the oven like I do (450 F for 10-15 mins), you can just pour the fat off of the baking sheet and into a glass jar. Keep the jar in the fridge and you'll have a smoky, salty fat for flavoring beans, potatoes, eggs, and yes, even molasses cookies. Which bacon fat recipe do you think I should try next? I'm leaning towards the sugar cookies... The Food Historian blog is supported by patrons on Patreon! Patrons help keep blog posts like this one free and available to the public. Join us for awesome members-only content like free digitized cookbooks from my personal collection, e-newsletter, and even snail mail from time to time! Don't like Patreon? Just leave a tip We're getting into some of the more obscure WWI posters now! This poster is from the United States Department of Agriculture, specifically the Bureau of Biological Survey. "Feed the Birds This Winter: They will repay you by destroying thousands of insects that harm gardens, trees, and crops" is the main message of this poster. Suggesting that ordinary Americans feed birds "especially during and after storms," provide shelter, and protect feeding areas from bird predators, the poster connects "our native birds" to their insect-eating abilities. This is a very text-heavy poster, so I've transcribed it all so you can know what it says! "EVERY LOCAL BIRD you keep from starving, when cold weather, snow, and ice shut off its natural food supply, will repay you by destroying hundreds of caterpillars, grubs, borers, beetles, and insects that would prey on your flowers, vegetables, fruit, foliage, or field crops. Birds more than pay for their keep. It is better to feed birds a little now than to grow crops for insects later. "FEEDING BIRDS IN WINTER costs little in time, food, or equipment. It attracts birds all winter to flit and chirp around your dooryard. It is one of the most important means of preserving birds. An increase in the number of birds means that more of them will nest in your trees next spring and become your summer companions. They will sing their thanks and contribute to the beauty and charm of your neighborhood. "Feeding birds in winter is a delightful and inexpensive recreation as well as an excellent investment. Children particularly enjoy and benefit from this form of applied nature study." "Feed the Birds this Winter. They will repay you by destroying thousands of insects that harm gardens, trees, and crops. "How to Help Birds in Winter "1. Supply food frequently, especially during and after storms. "2. Provide feeding shelters where birds can find food and eat comfortably during sleet and storms "3. Protect feeding stations against cats which will kill or frighten the birds. "Every Destructive Insect is on the Bill of Fare of One or More of Our Native Birds. "BIRDS feed upon almost all kinds of injurious insects. They lead active lives and require much food. A single bird often eats more than 100 insects at a single meal and sometimes consumes several thousands small insects. Birds on a 200-acre farm in North Carolina destroyed a million green bugs or wheat aphids daily. There are many localities where birds have saved certain trees, garden crops, or farm fields from total destruction. "Encourage all kinds of birds, as the various species prey on different kinds of insects. For example, the hair and downy woodpeckers render a special service in the protection of trees. They glean pests from beneath the bark and from within the wood. They account early for many a scale insect, bark beetle, borer, caterpillar, and ant. The bobwhite, one of the most important of our game birds, renders particular service in cultivated fields by destroying large numbers of potato beetles, wireworms, clover weevils, bollworms, cut-worms, army worms, and other crop pests. The bobwhite suffers particularly from hard winters. A little suet or a little cracked corn and grain will keep these valuable feathered servants in your employ. "FOR bobwhites, build low hutches with roofs that will keep out snow, or make wigwam-like stacks of grain sheaves with openings below. Keep the entrances free from snow and scatter within cracked forn or small grains or seeds. Putting out food on a bare spot on the ground is an easier method, but not so useful. "For woodpeckers, place suet under wire netting on trees; pour a melted mixture of suet and grain or seed in cracks in bark or in large holes bored in thick pieces of wood accessible to the birds; or make a 2-inch hole in a coconut and fill the interior with chopped suet and nuts and suspend from a a branch. "For small birds in general, make food shelves at windows or on trees, sheltered from the wind, and with raised edges to keep food from being blown off. Better still, put the food in a hopper, which will protect the supply from the weather and let it down gradually. Small birds will feed also at the coconut larders mentioned above and upon the suet mixtures. "The Best Winter Food For Birds "Suet or other fat, pork rinds, bones with shreds of meat, cooked meats, meal worms, cut-up apples, birdseed, buckwheat, crackers, crumbs, coconut meat, cracked corn, broken dog biscuits or other bread, hemp seed, millet, nut meats of all kinds (especially peanuts), whole or rolled oats, peppers, popcorn, pumpkin or squash seeds, raw or boiled rice, sunflower seeds, and wheat. "Full information as to feeding and attracting birds and providing nest boxes, houses, and shelters for them will be furnished on receipt of a postal card addressed to U.S. DEPARTMENT OF AGRICULTURE, Bureau of Biological Survey, Washington, D.C. "Begin to Feed the Birds To-Day - The Singing Laborer is Worthy of His Hire." Much of this advice is still sound today! At the time, of course, it was marrying not only nature study for children (a VERY popular topic during the Progressive Era) but also advocating for more natural forms of pest control in a time when pesticides existed, but had limited applications, and the availability of which was likely curtailed by more important wartime manufacturing. Birds do require an incredible number of insects to survive (bats, too), and even seed and fruit-eating songbirds feed their nestlings insects to give them the protein and fat they need to grow. Today, more and more farmers are returning to birds - from raptors to songbirds - to address pest issues, from pest birds (like starlings and seagulls) and rodents to insects. In some instances, the birds outperform pesticides. And contrary to what most people put in their bird feeders, birds eat a LOT of insects. Which is why I was surprised and happy to see mealworms on the list of recommended foods for birds, alongside suet and nuts. I've been feeding the birds in winter and early spring (we take the feeders down in the summer) to support the population, but also to let up a little on the insect population. Unlike 100 years ago, we're currently facing an insect apocalypse, which could have huge repercussions across the planet, including, but not limited to, agriculture, as many of our favorite crops rely heavily on pollination from wild insects. Which is why, even though I'm not a farmer and we're not at war, I still feed the birds in the winter. You can see my setup in the photo above - I have several squirrel-proof feeders (determined squirrels can get by even the baffles, but they provide shelter for the birds during the rain) with different mixes. One is a fruit, nut, and shelled sunflower seed mix with mealworms. Two more are just straight black oil sunflower seed. One has suet, and another feeder, which we're trying new this year, is just straight mealworms and beetles. Sadly, that one has been less popular. Maybe those insects don't have enough fat in them. Our half-dead holly tree provides enough spreading branches for the feeders but also cover from predators like hawks. Birds like to have cover they can escape to when predators come calling. And yes, that includes cats! Outdoor and feral cats are the number one predator of songbirds in suburban and urban areas. So keep your kitties inside or build them a catio. If they knew it in WWI, we should know it now. It is most important to support native birds, and not pest birds like starlings (who, while fascinating, are native to Europe and can out-compete native birds), so keep your food focused on native seeds, fruits, and nuts whenever possible. Just watch out for inexpensive fillers that aren't eaten by most songbirds. Sunflower seeds, peanuts, pecans, walnuts, raisins, blueberries, and cracked corn are all great. Suet (raw or rendered beef fat) is also good, as is natural peanut butter (avoid the hydrogenated kind, the kind with palm oil, and sugar), for providing the fat needed to keep birds warm and well-fed during the coldest winter months. I have set up our bird feeders right outside the kitchen window, and like Progressive Era nature study enthusiasts knew, they do provide a great deal of joy. I love coming to the kitchen every morning and checking to see what birds are at the feeders, and which ones need refilling. Since it has been incredibly cold and icy here in the Hudson Valley of New York this winter, our feeders have been almost as busy as Grand Central! We've seen cardinals, blue jays, tufted titmice (my favorites!), nuthatches, chickadees, sparrows, purple house finches, gold finches (they're mostly brown in the winter), downy woodpeckers, red breasted woodpeckers (whose breasts are actually just pink - it's the heads that are red!), dark-eyed juncos, mourning doves, and yes, even the occasional starling. More rarely we've seen cedar waxwings, rose-breasted grosbeaks (another favorite!), phoebes, and even the rare overwintering bluebird (though not actually on the feeders). Another way to support native birds (and insects!) is to plant native plants, especially fruit-producing shrubs for birds. For insects, native trees, especially oaks, can host up to 400 species of insects, including moths and butterflies. Okay, I'll get off my soapbox now! But always nice to see good sense from a century ago still holding true today. Do you feed the birds? Have a favorite winter visitor? Tell us in the comments! The Food Historian blog is supported by patrons on Patreon! Patrons help keep blog posts like this one free and available to the public. Join us for awesome members-only content like free digitized cookbooks from my personal collection, e-newsletter, and even snail mail from time to time! Don't like Patreon? Just leave a tip! This poster features a long string of Army green military trucks labeled "Food" snaking through snow-covered hills, directed by a soldier. It reads "Keep it Coming" and features a quote by Gen. John J. Pershing - "We must not only feed our Soldiers at the front but the millions of women & children behind our lines." Underneath reads, "WASTE NOTHING" with the seal and title of the United States Food Administration. Almost certainly printed in the winter of 1917-18, the poster was designed by artist George Illian. "Keep it Coming" was apparently Illian's first poster for the war effort. He went on to design several others for the United States Food Administration, but none as striking as this one. Sadly, I was unable to dig up any information on Illian other than he was a member of the Society of Illustrators and that he did some commercial art after the war. He died in 1932, but I have not been able to find an obituary. The imagery from the poster would not have been unfamiliar to ordinary Americans who had been following the news. By the fall of 1917, American soldiers were in the fields of Europe, led by General John Joseph "Black Jack" Pershing. After three years of brutal war, France and Britain welcomed the Americans, led by Pershing with open arms in June of 1917, but it was not until October of that year that the main bulk of the American Expeditionary Forces would arrive in France. Although the United States had officially entered the war in April of 1917, military personnel numbered under 200,000, and military supply and tactics were largely stuck in the 19th century. It took months of stop-and-start mobilization to train American troops (sometimes with wooden rifles) and get them overseas (on borrowed ships). The winter of 1917-18 was one of the worst in recent memory during the First World War. On December 29, 1917, the New York Times reported "Cold Snap Over Entire East," reporting temperatures in upstate New York as low as 20 degrees below zero. New York Harbor froze, railroads were backed up across the Eastern seaboard, and Europe was engulfed in snow and freezing rain. The weather conditions meant that nearly all of the supplies for Europe and for major Eastern cities were completely backed up. On December 30th, the New York Times reported coal shortages in New England and New York, blaming railroad backups and the requisitioning of civilian ships and tugs for the war effort. The railroad backups resulted in the nationalizing of the railroad system under William McAdoo. Illian's poster reflects the winter conditions on the front lines, too. Although the true horrors of trench warefare were often glossed over by the press, by 1917 many Americans were hearing from their "boys" overseas first hand. Marching in the abnormally frigid cold and torrential rains of the winter of 1917-18 in Europe was familiar to most of the soldiers. While the Eastern U.S. was brought nearly to a standstill by railroad blockages, coal shortages, and frozen ports, Britain, France, and Spain also experienced unusually cold temperatures, high snowfalls, and blocked railroads in December, 1917 and January, 1918. Like many of the propaganda posters of the First World War, "Keep it Coming" exhorts ordinary Americans not only to conserve food for American soldiers overseas, but also to help feed women and children in Allied nations. "Waste Nothing" was part of a campaign to reduce food waste and free up additional supplies to send overseas. American supplies of wheat in particular were low in 1917, and only by reducing consumption could food stocks be freed up for shipment overseas until farmers could increase production. The idea of personal self-sacrifice was part of a larger movement during the war to fund the war effort (through the sale of liberty bonds) and to "do your bit" to help the war effort. By using the wintry backdrop, Illian brought home the message that while Americans might be suffering from cold at home, things were worse in Europe, and American soldiers were doing all they could to help end the war and alleviate hunger and hardship among people who had already suffered four long years of war. 1917-18 would be the only winter warfare most Americans would see in Europe - the war officially ended in November of 1918 - but while millions of soldiers were sent home after Armistice, many Americans would remain in Europe until the summer of 1919, part of the demobilization efforts and cleanup (including burial duty) after the war. The Food Historian blog is supported by patrons on Patreon! Patrons help keep blog posts like this one free and available to the public. Join us for awesome members-only content like free digitized cookbooks from my personal collection, e-newsletter, and even snail mail from time to time! Don't like Patreon? Join with an annual membership below, or just leave a tip! Tip Jar

$1.00 - $20.00

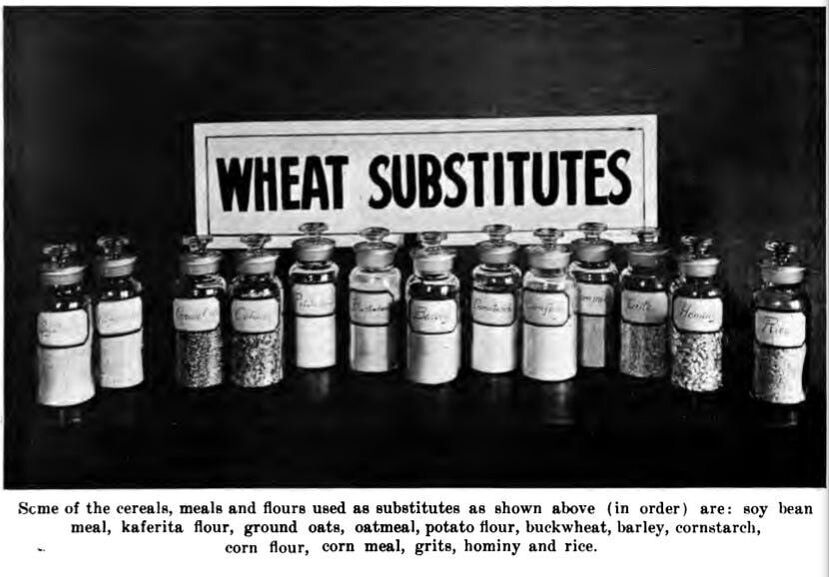

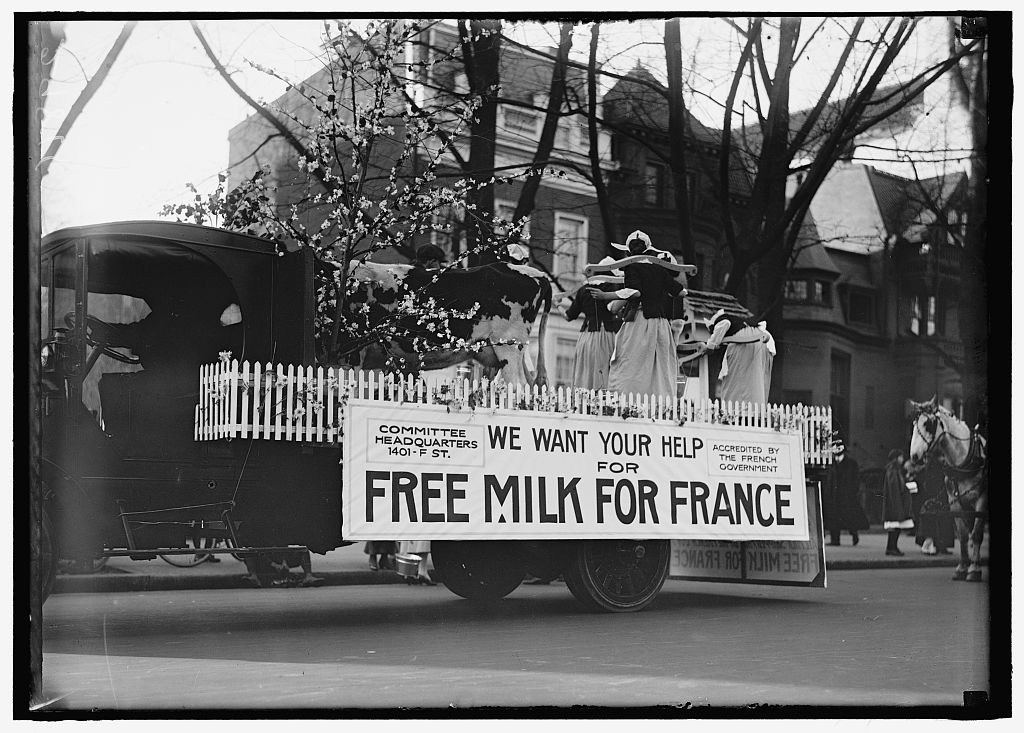

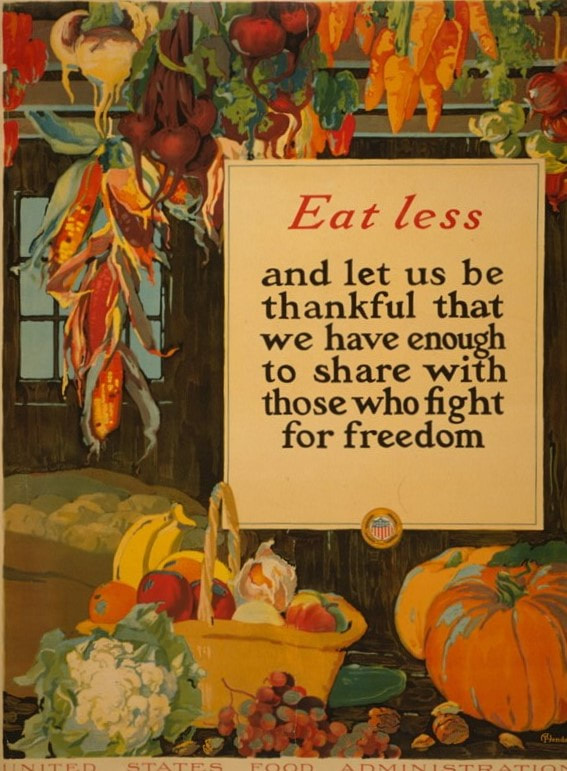

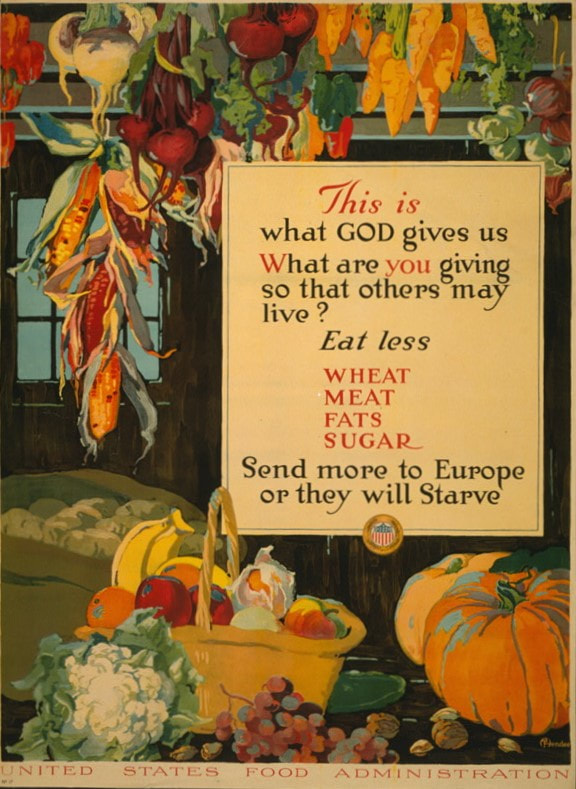

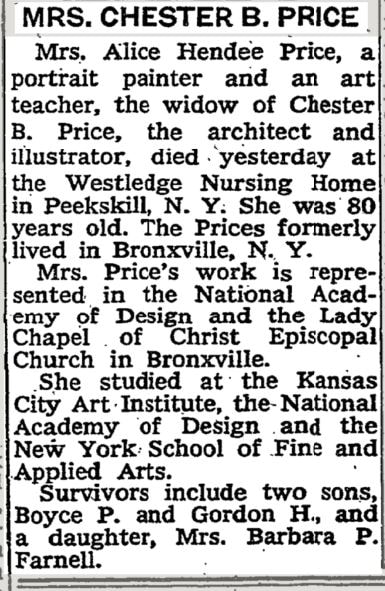

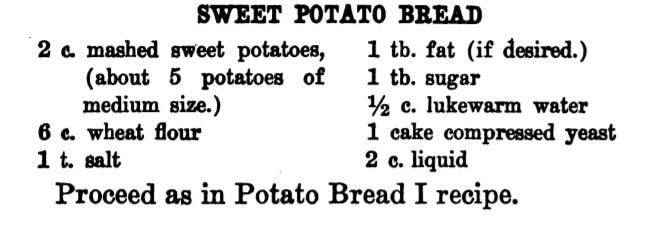

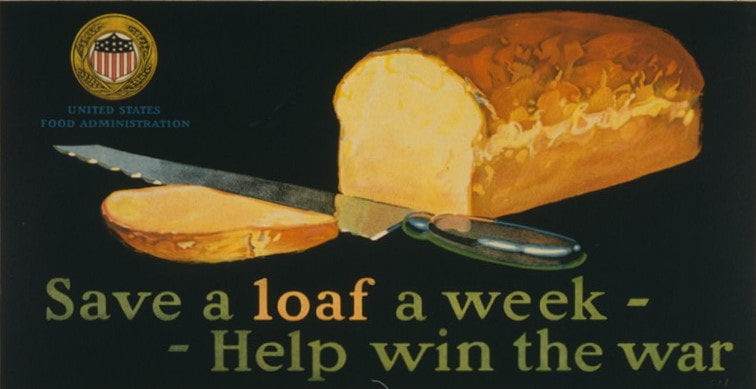

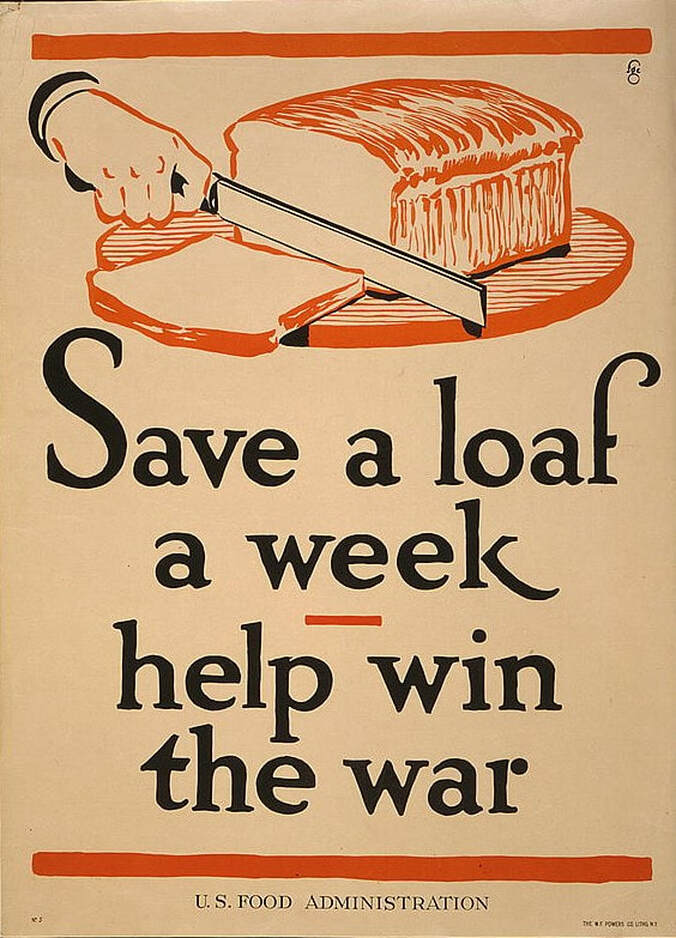

Like what you read, watch, or hear? Wanna help support The Food Historian, but don't want to commit to a monthly thing, or sign up for Patreon? Then you're in luck! You can leave a tip! This one-time (non-tax-deductible) donation helps keep The Food Historian going and pays for things like webhosting, Zoom, additions to the cookbook library, and helps compensate Sarah for her time and energy in helping everyone learn more about the history of food, agriculture, cooking, and more. Thank you! Tomorrow is Thanksgiving in the United States, so I thought it would be apt to visit the matching pair of posters. It's not clear if they were meant to be displayed together or not, but the artist, A. Hendee, clearly recycled one beautiful image for another version. In both images, produce is stored in an attic. Red peppers, turnips, corn, beets, carrots, and what looks like red onions hang from the rafters. A sack of potatoes, a basket of fruit (including bananas!), cauliflower, grapes, a lone cucumber, a few nuts, and two fat pumpkins sit on the wooden floor. In the first image, a white placard with the United States Food Administration seal on the bottom admonishes "Eat less, and let us be thankful that we have enough to share with those who fight for freedom." Much of the propaganda around food and the First World War admonished self-restraint when it came to food. Although the phrase "eat less" has had some controversy in the modern era, in the 1910s it was far less about ideal bodyweight (although that played a role) and far more about reducing waste. As the poor wheat harvests in 1916 and 1917 did not allow for normal consumption levels AND exporting to the Allies, most of the rhetoric in 1917 and 1918 was focused on reducing waste, refocusing American eating habits on other types of food, and reducing consumption in general. For instance, while messages of "eat less" were common, so was the Gospel of the Clean Plate, which exhorted Americans not to waste food. In the second poster, the message reads, "This is what God gives us - what are you giving so that others may live? Eat less wheat, meat, fats, sugar - send more to Europe or they will starve." The Library of Congress tentatively dates this poster as 1917, but that could be simply because it is WWI-related. However, this message is far more explicit than the first, so it may very well have been the first printed. We have specific foods to avoid, and the spectre of starvation in Europe is raised. But we also have a more explicit reference to the image itself, "This is what God gives us" is referencing the abundant produce. Which, you'll notice, does not include hams or bushels of wheat or other foods you might find in a 19th century attic. The focus is entirely on produce, which is on purpose, as eating more fruits and vegetables instead of more calorie-dense and shelf stable foods like wheat, meat, fats, and sugar. Potatoes in particular were touted as an alternative to bread. Although the Library of Congress has no other posters attributed to "A. Hendee," I've managed to track her - yes her! - down, thanks to a clue post from a UK museum that found her full maiden name. Alice Julia Hendee, later Alice Hendee Price, was born in 1889, possibly in Kansas as she attended the Kansas City Art Institute before moving to New York to attend the National Academy of Design and the New York School of Fine and Applied Arts. In 1917 she was listed in a city directory as living on the Upper West Side, and in 1923 she moved to Bronxville, NY in Westchester County. At some point she married architect and illustrator Chester A. Price. Alice made the local news quite frequently for her art, and by 1950 was teaching classes to area women. She died in Westchester county in 1969 and outlived her husband, but in typical mid-century fashion, not his name. Like many of the illustrators and artists who created iconic propaganda posters for the First World War, Alice Hendee Price's recorded history makes no mention of her wartime work. But the stunning images remain. And this Thanksgiving, although we no longer need to curtail our eating habits for wartime, the message of being thankful for what we have and sharing with others is a timeless one. Have a lovely Thanksgiving, everyone, whether you're celebrating with family or friends, and I hope you can enjoy all the bounty of the season. The Food Historian blog is supported by patrons on Patreon! Patrons help keep blog posts like this one free and available to the public. Join us for awesome members-only content like free digitized cookbooks from my personal collection, e-newsletter, and even snail mail from time to time! Don't like Patreon? Join with an annual membership below, or just leave a tip!  "Wheat Substitutes" as illustrated in "Liberty Recipes" (1918). Caption: "Some of the cereals, meals and flours used as substitutes as shown above (in order) are: soy bean meal, kaferita flour, ground oats, oatmeal, potato flour, buckwheat, barley, cornstarch, corn flour, corn meal, grits, hominy, and rice." Last time for World War Wednesday, we discussed how important it was during the First World War to save wheat and reduce bread consumption. During the war a number of cookbooks were published to help Americans reduce their consumption of wheat, meat, butter, and sugar and how to go without or reduce the use of scarce or expensive ingredients like eggs. When it came to bread, there were very few recipes that used no wheat flour at all, but instead most recipes used alternative grains like barley, rye, corn, and oatmeal or other ingredients like mashed potatoes or cooked rice to reduce the overall ratio of wheat flour used. Liberty Recipes was written by Amelia Doddridge, who the title page lists as "Formerly, Instructor of Cooking, Manual Training High School, Indianapolis, Indiana; and Emergency City Home Demonstration Agent, Wilmington, Delaware. Now, Head of Home Economics Department, Wooster College, Wooster, Ohio." The book was published by Stewart & Kidd Company in Cincinnati, Ohio in 1918. I wasn't able to find much more on Amelia herself. I found a dissertation that notes that several classes in food and household management at Wooster College were taught by Amelia, who was then Acting Dean of Women. But those classes were apparently only offered temporarily during the war, "These particular classes were offered only between 1918-1919 during the "confused period of war, fuel shortages, S.A.T.C., Spanish flu, and demobilization." Which seems to indicate that Amelia herself may not have survived as an instructor after the war. A reference from 1922 places an Amelia Dodderidge in Montevallo, Alabama as head of the home economics department "at Montevallo," which possibly meant the college located there. I found a reference to an Amelia Doddridge teaching high school home economics in Ohio in 1924. And another to an Amelia Dodderidge working at a Farm Bureau in Pennsylvania and/or as a county home economics representative, and/or as the Home Economics Extension representative from the state college, all in Pennsylvania, all in 1926. In 1929 there's a Miss Amelia Dodderidge in Modesto, California, acting as an "assistant home department agent." By the 1950s she appears to be living, retired, in Franklin, Indiana and throughout the late 1950s and 1960s there are numerous articles in the Franklin Star authored by Amelia Dodderidge. A 1962 article indicates she was working for the Methodist Home (likely a home for the elderly) in Franklin, IN and, indeed, most of the articles she published in the Franklin Star were called "The Home Window," apparently reporting on the activities and events of the Methodist Home. The trail runs cold at the very end of 1963. The last reference to Amelia is published on December, 31. It's unclear whether the newspaper simply did not run her column again or if the newspaper itself ceased publication or if it simply wasn't digitized past 1963. Although it's tough to prover all these Amelia Dodderidges were the same person, it is very likely. Amelia apparently continued her home economics work throughout her life, even after "retirement." But back to Liberty Recipes. The cookbook is a fascinating one, and I particularly love some of the slogans listed in the frontspiece; my two favorites are "Place meat and buns behind the guns" and "Husband your stuff; don't stuff your husband." Also interesting are the references in the foreword to the cookbook itself being much more convenient for reference by housewives rather than taking "too much trouble to hunt in a pile of leaflets for the recipes she wishes at the particular time she needs it" - a reference to the numerous bulletins and cookbooklets being published by the USDA and other government agencies. In addition, the foreword claims that although the recipes listed are designed for the "present emergency," "they should be usable and still practical even after the war clouds pass and Freedom is ours." There are numerous bread recipes in the cookbook - both yeast and quick breads. In addition, the cookbook focuses on meatless and meat-saving recipes, a few salads, and numerous sugarless, low-sugar, and wheat- and fat-saving dessert recipes. This recipe for Sweet Potato Bread seemed quite modern, and a fun recipe to share in the lead-up to Thanksgiving. Although I have not had time in a while to bake yeast bread, I thought I would share it anyway. Maybe I can take a stab over the holiday. World War I Sweet Potato Bread (1918)The original recipe makes references to other recipes, so I've combined the instructions for your convenience. A cake of yeast is about the same as dried yeast packets that are sold today. Although you can try it with RediRise or similar fast-acting yeast, I recommend plain ol' active dry yeast. 2 cups mashed sweet potatoes (about 5 potatoes of medium size.) 6 cups wheat flour 1 teaspoon salt 1 tablespoon fat (if desired.) 1 tablespoon sugar 1/2 cup lukewarm water 1 cake compressed yeast (or 1 envelope active dry yeast) 2 cups liquid Use the potato water for the liquid. Pour it gradually over the hot mashed potatoes. When lukewarm add the softened yeast, salt, sugar, and fat. Stir in the rest of the flour gradually. When the dough becomes too stiff to stir, work in the remainder of the flour by kneading with the hands. It may take a little more flour or a little less depending upon the kind of flour used. The dough should be of such a consistency that it will not stick to the hands or to the bowl. Knead 10 or 15 minutes until the dough is smooth and elastic. Place in a bowl, cover, and keep it in q warm temperature (75 to 85 F). When risen twice its bulk, cut down and knead again. Then shape into loaves, place in greased pans, and set in a warm place. When light and doubled in bulk it is ready to bake. To prevent a crust from forming over the top of the loaf while rising, rub the surface with a little melted fat. Watch the rising and put into the oven at the proper time. If risen too long, it will make a loaf full of holes; if not risen enough, it will make a heavy bread. Bake 45 minutes to 1 hour in a moderately hot oven (375 to 400 F). If oven is too hot, the crust will brown before the heat has reached the center of the loaf and will prevent further rising. The loaf should raise well during the first 15 minutes of baking; then it should begin to brown, and continue browning for the next 15 or 20 minutes. The last 15 to 30 minutes, it should finish baking and the heat may be reduced. When done, the bread will not cling to the sides of the pan. If a tender crust is desired, brush the bread over with a little melted fat as soon as it is taken from the oven. If you end up making this recipe, let us know in the comments how it turned out! There are lots of other interesting recipes to be had in Liberty Recipes, including a potato biscuit pie crust recipe, buckwheat spice cake, and cornmeal gingerbread, to name a few! Are there any recipes in there that you want to try? The Food Historian blog is supported by patrons on Patreon! Patrons help keep blog posts like this one free and available to the public. Join us for awesome members-only content like free digitized cookbooks from my personal collection, e-newsletter, and even snail mail from time to time! Don't like Patreon? Join with an annual membership below, or just leave a tip! It's finally cold enough to bake in my neck of the woods. I made New York Gingerbread for a Halloween party this past weekend and it was delicious. You may be thinking of finally tackling the yeast bread you never made during the COVID shutdown. But like the early days of the pandemic when the shelves were empty of flour, during the First World War, wheat was in short supply. Poor wheat harvests in the fall of 1915 and 1916 meant that when the United States joined the war in April of 1917, there was not enough wheat to feed both the citizens of the United States and the military and their Allies. So the United States Food Administration embarked on a campaign to get Americans to voluntarily give up some of their favorite foods - including white bread made from wheat flour. By the 1910s white bread was ingrained (no pun intended) in the American diet and culture. It held onto its associations with wealth and refinement long after white flour became affordable and abundant. In addition, the conventional wisdom of nutrition science at the time elevated carbohydrates as a valuable source of energy. Which meant that both white bread and refined white sugar were considered healthful and important sources of the newly-discovered calories. Getting people to give up their favorite breakfast, side dish, and anytime (including midnight) snack was not going to be easy. This pair of propaganda posters produced by the USFA illustrate the same primary point - that if everyone gave up a little, the compound effect would be enormous. You'll note they don't focus on getting Americans to stop eating white bread - just to consume less. The implication of both posters is that be reducing consumption by as little as one slice a day would really add up. Other campaigns, including Wheatless Wednesday (partner to Meatless Monday), told Americans to replace the slice of bread customary with each meal with a baked potato, especially after the potato surplus in 1918. Alternative grains, especially corn, were also touted as substitutes for white bread. Restaurants were banned from bringing rolls or bread to the table before customers ordered their meal (sugar bowls were out, too). By 1918, one way the Food Administration tried to control the consumption of white bread without instituting mandatory rationing was to require Americans to purchase two pounds of alternative grains or flour for every one pound of wheat flour. However, although other campaigns emphasized corn as a valuable substitute, there's evidence that people may have just discarded the additional flours they were forced to purchase. Despite these challenges, the fact that the United States was able to feed their military, and the Allies, on the same 1916 wheat harvest suggests that Americans did reduce their wheat consumption in 1917. Today we know that refined white flour is a little too efficient a carbohydrate, and that the vitamins and minerals in whole grain flour, and the added fiber, are generally much better for human health. For wheatless recipes from the First World War, check out this article from North Carolina State University Libraries. The Food Historian blog is supported by patrons on Patreon! Patrons help keep blog posts like this one free and available to the public. Join us for awesome members-only content like free digitized cookbooks from my personal collection, e-newsletter, and even snail mail from time to time! Don't like Patreon? Join with an annual membership below, or just leave a tip!

Note: This article includes descriptions of wartime violence, genocide, and violence against women. Sensitive readers be warned.

Earlier this year, on Armenian Remembrance Day, President Biden officially declared the actions of Ottoman Turkey against Armenians during the First World War to be genocide. While some people might be aware of the Armenian genocide, I think fewer Americans are aware that it was part of the First World War.

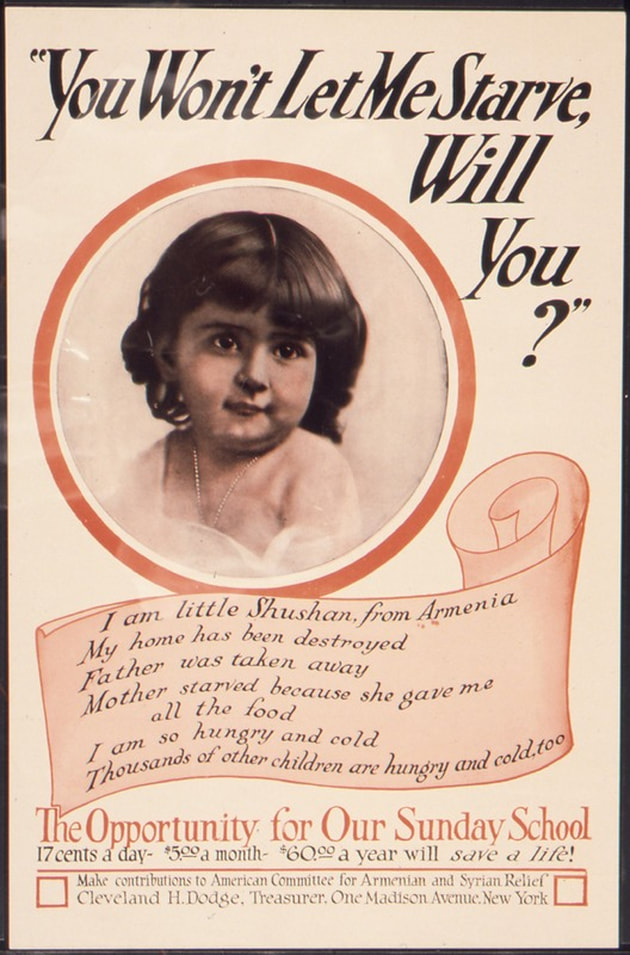

In the above poster, "You Won't Let Me Starve, Will You?" "Little Shushan" says, "My home has been destroyed. Father was taken away. Mother starved because she gave me all the food. I am so hungry and cold. Thousands of other children are hungry and cold, too." Directed specifically at Sunday Schools and children to raise funds for the American Committee for Armenian and Syrian relief, this poster is just one of the appeals made to Americans for charitable support for war-torn regions of Europe and the Middle East. Americans in 1915 were intensely aware of the actions of the Ottoman Empire as it was widely covered by newspapers. Like many campaigns that used starving children in Belgium to raise relief funds or exhort Americans to change their eating habits, Near East Relief and Armenian and Syrian Relief efforts were undertaken as charitable endeavors. The United States never declared war on the Ottoman Empire, perhaps at the behest of relief organizers. But without military intervention, the genocide continued as late as the 1920s. Armenians were Orthodox Christian in a predominantly Muslim Turkish empire. Russia, Turkey's enemy, was also predominantly Orthodox Christian at the time, meaning Armenians were largely branded a "fifth column" of seditious enemy spies living within the borders of the empire. This attitude was exacerbated by the Battle of Sarikamish, in which the Ottoman forces attempted to invade Russia between December, 1914 and January, 1915. Unprepared for the winter weather, the Ottoman military lost more than 60,000 men in a resounding military defeat. In retreat, the Ottomans indiscriminately burned, looted, and massacred Armenian villages near the border. The Ottoman military commander blamed the Armenians for the defeat, saying they had sided with the Russians. This set off a whole host of anti-Armenian violence, despite the fact that many Armenian men had enlisted in the Ottoman military. By the spring of 1915, the Ottoman Empire had launched a campaign of extermination against the Armenians. The lucky ones were able to escape. The not so lucky ones were systematically massacred or sent on forced death marches. The few Turkish politicians who protested were threatened with assassination. Any Muslim caught harboring an Armenian was threatened with execution. Many Armenian men who were massacred were rounded up and taken away from their villages to be killed. So many bodies were dumped in the Tigris and Euphrates Rivers that the corpses clogged the waterways and had to be disposed of with explosives. The pollution caused disease for communities living downstream, even after the war was over.

Although charitable organizations worked in the "Near East" throughout the war, and Americans did donate thousands of dollars toward food and relief work, the brutality continued. Coinciding with the massacres of men, Armenian women, children, and the elderly were sent on forced marches into the Syrian desert, punctuated by violence. Those few who survived to arrive at camps after marching without food or water, saw their children sold to childless Muslim families, and the women systematically raped. Those who survived to 1916 and 1917 were ultimately also massacred, so the Empire could avoid freeing them after the war. In all, more than 90% of the Armenian population in the Ottoman Empire was killed or deported, a number scholars estimate at between 1.5 and 2 million people.

The "Lest They Perish" poster above illustrates an Armenian (or possibly Syrian) woman with a child on her back standing in the midst of a bombed-out village. Despite the best efforts of the charitable organizations trying to help Armenians, most of them did, indeed, perish.

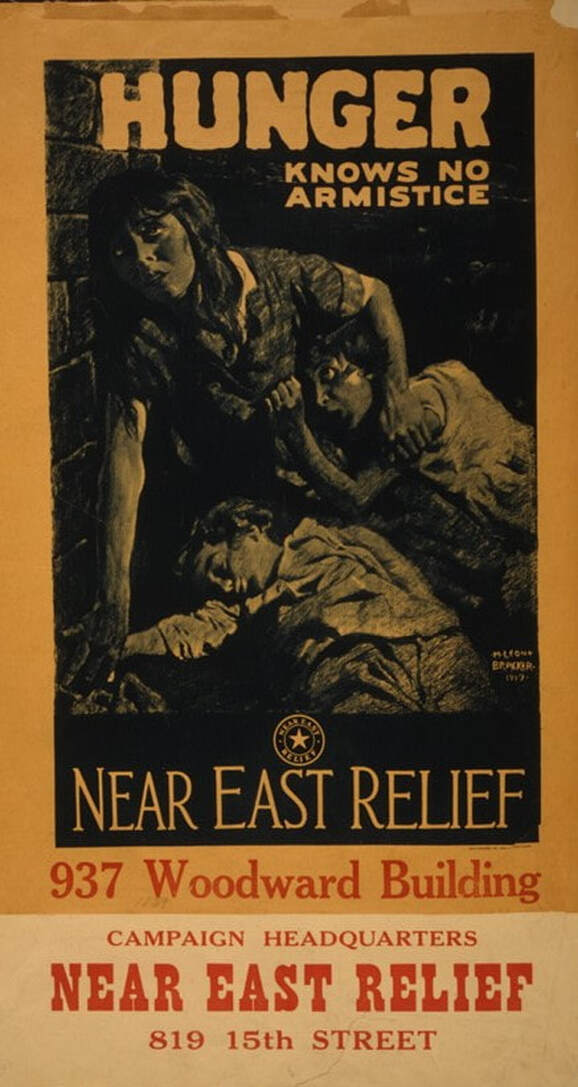

The use of hollow-cheeked women and children in war-torn regions was designed to pull on the heartstrings (and pockets) of Americans of all ages and backgrounds. Propaganda posters by charities like Near East Relief began in 1915 and continued until after the war, along with the genocide. Government-sponsored killings largely ended by 1917, but massacres continued on and off and widespread starvation threatened those who had managed to survive. This poster, "Hunger Knows No Armistice," succinctly points out that starvation was the post-war threat.

Near East Relief was founded in 1915 in Syracuse, NY as the American Committee on Armenian Atrocities, in reaction to reports from Henry Morgenthau, Sr., who was serving as American ambassador to the Ottoman Empire. Morgenthau was a German-born Jew appointed by Wilson to serve as ambassador in 1913 - a position he initially refused because of Wilson's idea that Jews were well-suited to serve as a bridge between Christians and Muslims. He ultimately accepted the position, and although his work at first consisted mostly of protecting Jewish residents and Christian missionaries, he was soon absorbed by the plight of Armenians in the Empire. Despite his frequent reports of genocide and violence against civilians, the United States remained officially neutral. Frustrated by the Turkish government's refusal to stop the killings, and by the American policy of non-interference, Morgenthau resigned in 1916. In 1918 he published Ambassador Morgenthau's Story, an accounting of his conversations with Ottoman officials about the genocide. However, during his tenure as Ambassador, he was the primary contact for the organization that would become Near East Relief, and was in charge of disbursing charitable donations in Turkey. After his 1916 resignation, it is not clear who disbursed funds, but fundraising continued. In 1919 the committee became only the second charitable organization in American history to receive a Congressional charter. The American Red Cross had been the first. And although charitable efforts continued, they could not stem the tide of genocide. The following video from Facing History & Ourselves, outlines the work of Morgenthau, the Committee on Near East Relief, and the American response (or lack thereof) to the Armenian genocide.

Near East Relief continued their work, focused largely on rescuing Armenian orphans and housing and educating them in a complex system of orphanages inside and outside of Turkey. In 1922, with the burning of Smyrna, Near East Relief evacuated 22,000 children into neighboring states. Evidence suggests that Greek and Armenian neighborhoods in Smyrna may have been purposely set alight by Turkish soldiers. The Muslim and Jewish quarters remained undamaged by the fire. Greek and Armenian residents of Smyrna were subjected to additional massacres, rape, and deportation, both before and after the fire.

In 1930, Near East Relief pivoted to become the Near East Foundation, working on education and economic development efforts in the Middle East and Africa. It still exists as a charitable organization today and the Near East Foundation has created a museum and archive about its organizational history and origins in the Armenian genocide. The U.S. Government never declared war on the Ottoman Empire. There was no military intervention. After the defeat of the Ottoman Empire, the Treaty of Sevres, and subsequent overthrow of Sultanate with the Turkish Revolution, there was an opportunity to create an Armenian state, which Woodrow Wilson had apparently been in favor of. However, his dreams of reorganizing the Middle East were dashed. The new Turkish government and Bolshevik Russia simultaneously invaded and partitioned the old Armenian Republic before Wilson's plan could be implemented. This led to the creation of both the Armenian Soviet Socialist Republic and the absorption by Turkey of portions of the former Armenian Republic, confirmed by the 1922 Treaty of Moscow between Soviet Russia and the new Turkish state. Despite ample first-person evidence of the horrific, systematic, and state-sponsored massacres, and the promise by the Allied Nations in 1915 that the Ottoman Empire would be held responsible for crimes against humanity, no one was ever prosecuted. In fact, the lack of consequences for the genocide may have inspired Adolf Hitler's death camps. He wrote, "I have issued the command -- and I'll have anybody who utters but one word of criticism executed by a firing squad -- that our war aim does not consist in reaching certain lines, but in the physical destruction of the enemy. Accordingly, I have placed my death-head formations in readiness -- for the present only in the East -- with orders to them to send to death mercilessly and without compassion, men, women, and children of Polish derivation and language. Only thus shall we gain the living space (Lebensraum) which we need. Who, after all, speaks today of the annihilation of the Armenians?" The rapid fall of the Ottoman Empire following the war likely played a major role in the lack of prosecution, as politicians were killed or dispersed and official evidence destroyed. In addition, it took until the Second World War to establish the United Nations and the criminal court at the Hague. Even so, international recognition of the genocide did not formally begin until the United Nations War Crimes Commission published a report in 1948 establishing what constituted war crimes. The Armenian genocide was cited as prime historical example of war crime and crimes against humanity. But it was not until 1985 that the term "genocide" was officially given to the massacres. Most nations did not officially recognize the Armenian genocide until the very late 20th or early 21st centuries. In fact, the United States, which had put so much effort into charitable work and so little effort into military intervention, only just recognized the genocide this year (2021). The Turkish government still refuses to admit to that the actions against the Armenian people during the First World War amounted to genocide. What is left of the Republic of Armenia became an independent state in 1991 with the fall of the Soviet Union. Today aligned politically and culturally with Europe, Armenians have transitioned fully to a capitalist economy. But their politics, like those of many nations, remain fraught in the modern era. In 2018 anti-government protests, named the 2018 Armenian Revolution, helped usher in political reforms. But other, older conflicts remain, including the Nagorno-Karabakh conflict between Armenia and Azerbaijan, which recently re-erupted in violence in the fall of 2020. A ceasefire was negotiated, and Armenians evacuated, but lasting peace remains elusive. To learn more about the Armenian genocide, visit the Armenian Genocide Museum of America.

The Food Historian blog is supported by patrons on Patreon! Patrons help keep blog posts like this one free and available to the public. Join us for awesome members-only content like free digitized cookbooks from my personal collection, e-newsletter, and even snail mail from time to time! Don't like Patreon? Join with an annual membership below, or just leave a tip!

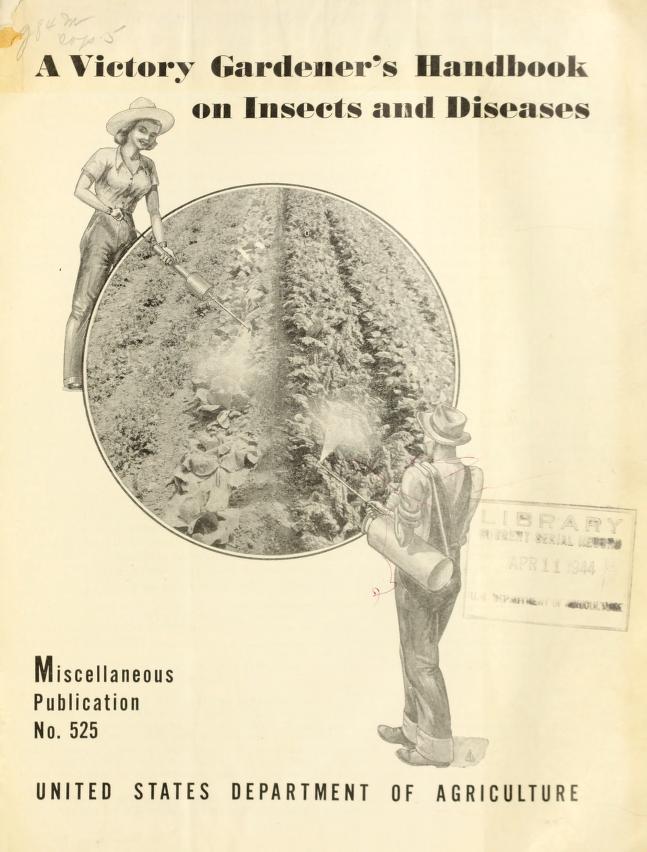

When it comes to modern ideas about Victory Gardens, there's a lot of romanticism and rose-colored glasses. Hearkening back to a kinder, gentler time when everyone pulled together toward a common goal and had delicious, organic vegetables in their backyards while they did it. But the reality was often much different from our modern perceptions. This propaganda poster is a good example of that. "Shoot to kill!" it says - "Protect Your Victory Garden!" In it, a woman wearing blue coveralls and a wide-brimmed hat, a trowel in her back pocket, sprays pesticide on a large, green insect (a grasshopper?) taking a bite out of an enormous and perfectly red tomato. She is protecting her victory garden from the "fifth column" of insect predation. "The Fifth Column" was a term used in the United States to describe sabotage and rumor-mongering by foreign spies. In this instance, insects become the "fifth column" because the act of eating crops threatens wartime food supplies, and is therefore sabotage by a foreign enemy. The food supply had to be protected and maximized at all costs. Anxieties around food supplies, especially in the winter when commercially produced foods might be scarce, meant that victory gardens took on special urgency. For the first time in at least a generation, Americans were having to put up their own food to help them get through the winter. And making every quart count was only possible if the garden did well. Lots of militarized language was used in propaganda concerning food, but none as war-like as the battle against pests in the victory garden. The idea that gardening before the 1950s was all organic is a common misconception. Even prior to the First World War, farmers and even some gardeners were dusting their crops with Paris Green and London Purple. Paris Green was a bright green toxic crystalline salt made of copper and arsenic. London Purple was calcium arsenate - normally white, but also a byproduct of the aniline dye industry, and was therefore sometimes tinged purple. Along with arsenate of lead, another salt, these three were termed arsenical pesticides and were used often in agriculture. The arsenic in rice scare from a few years ago was likely due to elevated levels of arsenical pesticide residue in the soil. Especially since rice from California, which first began to be commercial produced in 1912, but was not widely available across the country until the 1960s. That late adoption of rice agriculture meant that production was not as exposed to arsenical pesticides as elsewhere in the U.S. In 1944, the USDA published "A Victory Gardener's Handbook of Insects and Diseases" that identified common pests and suggested remedies. Calcium arsenate and Paris green were recommended (albeit with warnings about arsenic residue), along with:

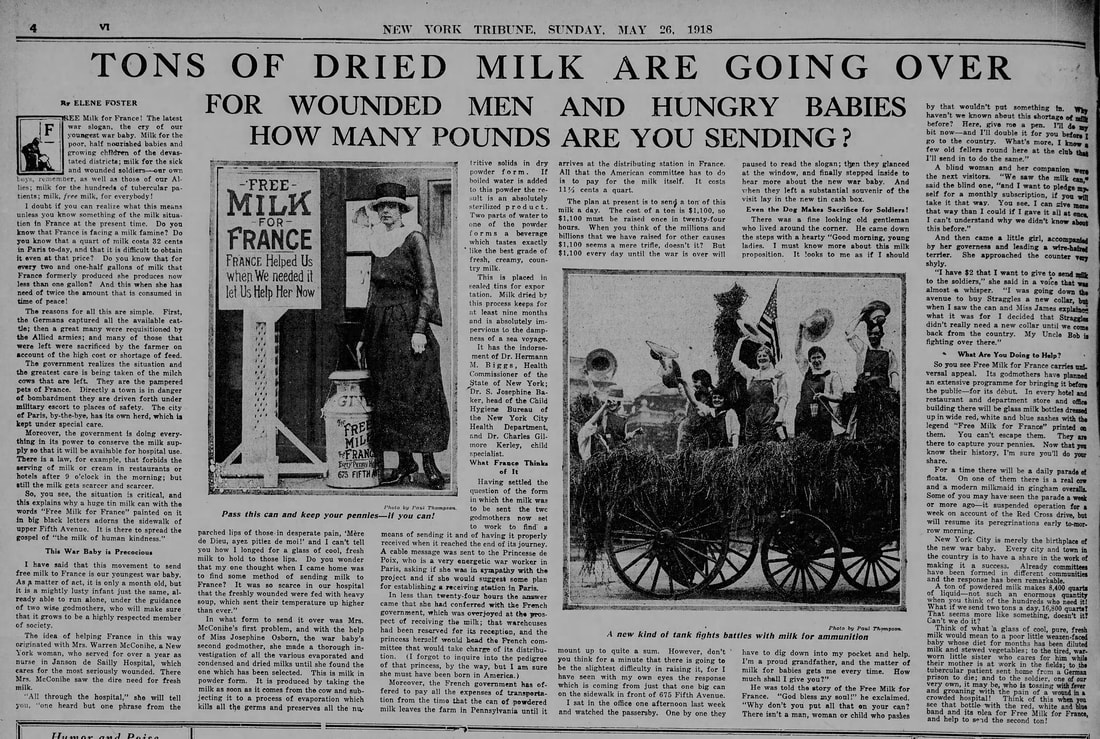

Although some people may have chosen not to purchase pesticides, likely due to expense more than concerns about poisoning, the emphasis on the danger pests posed to the general food supply continued. Hand atomizers, which is what the hand sprayer in the propaganda poster is called, were frequently depicted in print and even on film. Despite USDA warnings about application safety, no one is ever seen applying the highly toxic, aerosolized liquid pesticides with protective equipment. However, the science of the effects of exposure to toxic chemicals was not yet well-studied. DDT, invented in 1939, was deemed a miracle chemical and helped dramatically reduce diseases like malaria and water-borne bacteria that in previous wars had sometimes killed more soldiers than the conflict itself. Because soldiers faced no immediate effects, the chemical was deemed safe, and used everywhere from farms to a treatment for lice in children. But like the arsenical pesticides, the effect was cumulative, and it wasn't until Rachel Carson's 1962 Silent Spring that Americans began to wake up to the dangers of pesticides. The Food Historian blog is supported by patrons on Patreon! Patrons help keep blog posts like this one free and available to the public. Join us for awesome members-only content like free digitized cookbooks from my personal collection, e-newsletter, and even snail mail from time to time! Don't like Patreon? Join with an annual membership below, or just leave a tip! Join on Patreon or with an annual membership by June 30, 2020 and get a picnic history packet mailed to your door! Last week we learned about the big Dairy Exposition during WWI - this week we're examining the Free Milk for France movement, which coalesced about the same time. This propaganda poster by F. Louis Mora from 1918 is one of the more famous of the food-themed propaganda posters of the First World War. In it, a soldier ladles milk out of a large milk can into the bowl of a French child, one of several, accompanied by a wounded French soldier with a tin cup and crutch. Judging by how bundled up everyone is, it's probably winter. Ironically, the Free Milk for France campaign actually focused on provided dried milk. On May 13, 1918, the Committee to Obtain Free Milk for France launched a fundraising parade. "The parade, consisting of two floats and an escort of soldiers and sailors, including a navy band, started from the First Field Hospital Armory at Sixty-sixth Street and Broadway and canvassed the city as far down as the Wall Street District," reported the New York Times the following day. "The money will be used to purchase powdered milk to be sent to France for the use of wounded soldiers, babies, and tubercular patients." In the above photo, a woman dressed in overalls and a straw hat drives a team of horses pulling a large hay wagon. Another woman riding on the wagon is dressed in a military-style outfit holding a small bucket and a wooden shoe - likely soliciting donations. An American flag attached to a sheaf of hay is behind them. The first parade made over $1,000. The group launched another parade a few days later, on May 17th, parading "down Fifth Avenue from Fifty-ninth Street to Twenty-second Street yesterday afternoon." Featuring seven floats, including young society girls "dressed as milkmaids."  Free Milk for France parade, motor truck with a float of milkmaids with a live cow and flowering tree, surrounded by a white picket fence. A large sign reads, "We want your help for Free Milk for France," with smaller notes - "Committee Headquarters 1401-F St." and "Accredited by the French government." Harris & Ewing photographers, May, 1918. Library of Congress. In the above black and white photo, a flat bed truck features a large float carrying a flowering tree, a live dairy cow, and at least five young women dressed as Brittany milkmaids. The edges of the float are surrounded by a white picket fence. On May 19, 1918, the New York Times published "America Sending Milk to France." The article is transcribed below: One of the greatest sources of suffering in France has been lack of milk. The causes for this lack are manifold. In many instances the Germans slaughtered cows for beef whose greater value lay in their milk; in other instances the Government of France requisitioned the animals for army use, and in still others the farmers found themselves forced to kill their cattle on account of the shortage of pasture and fodder. All in all there have been lose to the people of France about 2,000,000 cows, and the main source of maintenance of infants and children, of the crippled and the wounded, the sick and tubercular, lies in milk. At present the death rate of children in France is from 58 to 98 per cent. The number of wounded and crippled needs no repetition here. The increase in the ranks of the tubercular is appalling. Outside Belgium, perhaps, there is no other country which has so greatly succumbed to this disease. The supply of milk in France has been depleted at least 16 per cent. Under present conditions infants must take vegetable stews as a food substitute. What this means to their health and their growth the mortality figures show. Wounded soldiers get heavy soups, which are well-nigh fatal in their effects. The tubercular of France have almost been forgotten. Milk has become a luxury far beyond the reach of the majority of them. In order to do something to meet this situation and to conserve the milk they have, the French Government is taking vigorous measures. Great care is devoted to the protection of milch cows. From bombarded towns, under military escort, two or three at a time are led back to places of safety. Farmers are urged to make all sacrifices possible to provide proper feed for them. Within Paris a herd of cows is kept under civic care. Government restriction now forbids the serving of milk or cream for any purpose in restaurants, hotels, or public eating places after 9 o'clock in the morning. In private homes, rich or poor, milk is only given to young children and the sick. Milk in Paris costs 32 cents a quart, when it can be bought. It was in a desire to do something to change these conditions that Mrs. Warren McConihe and Miss Josephine Osborne organized the Free Milk for France Fund. Mrs. McConihe had seen the soldiers suffering greatly for want of milk, she had seen them grow feverish under the influence of heavier foods. She had seen the Belgian and French refugees almost starved for lack of milk. Upon her return to this country she found that America had enough milk to send some across. Because it requires less shipping space, she chose powdered milk. It is scientifically prepared by subjecting fresh, pure, full-creamed milk to a rapid evaporating process, which preserves the nutritive solids and keeps without ice for months. The milk when prepared costs about 13 cents a quart. There is no other cost. The Government of France has taken over the details of transportation. It is the aim of the organization to send one ton of milk a day. All that is necessary is to mix with hot water. The milk in this form has been recommended even for home use by Dr. Hermann M. Biggs, State Health Commissioner; Dr. S. Josephine Baker of the Child Hygiene Bureau, and Dr. Charles G. Kerley, a child specialist. At a cost of $1,100 a ton of dried milk is sent across, enough to feed 8,400 babies or wounded soldiers or tubercular patients. $52 will send 100 pounds of dry milk or 40 quarts of liquid; $5.20 will sent ten pounds, or forty quarts, and 13 cents will send one quart. The aim of the Free Milk for France organization is to have the nation as a whole respond to its work. Branches are being organized all over the country. The headquarters of the fund is at 675 Fifth Avenue. These two parades, held during the National Milk and Dairy Farm Exposition, were just the first of a campaign that would last into 1919 and spread across the country. By the end of 1919, there were campaigns in thirty-six states, and the distribution in France was being organized by Madame Foch - wife of French General Ferdinand Foch. The rhetoric around milk and its importance in the diet, especially for children and the sick, would be replicated in the Second World War. The Food Historian blog is supported by patrons on Patreon! Patrons help keep blog posts like this one free and available to the public. Join us for awesome members-only content like free digitized cookbooks from my personal collection, e-newsletter, and even snail mail from time to time! Don't like Patreon? Join with an annual membership below, or just leave a tip! Join on Patreon or with an annual membership by June 30, 2020 and get a picnic history packet mailed to your door! |

AuthorSarah Wassberg Johnson has an MA in Public History from the University at Albany and studies early 20th century food history. Archives

September 2023

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed